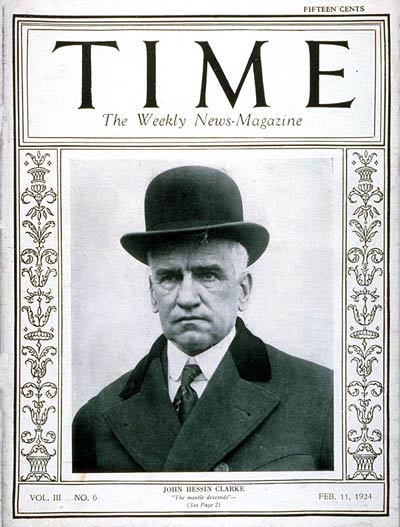

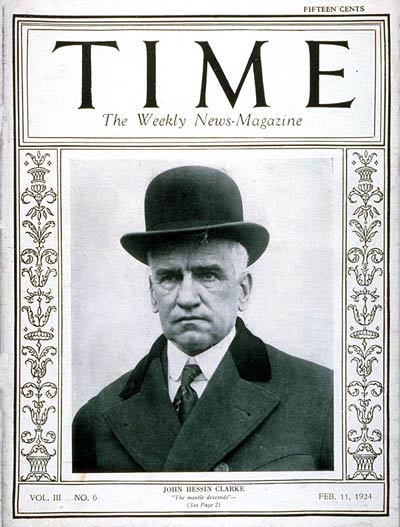

John Hessin Clarke on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Hessin Clarke (September 18, 1857 – March 22, 1945) was an

In June 1916, a vacancy arose on the Supreme Court when Associate Justice

In June 1916, a vacancy arose on the Supreme Court when Associate Justice

Entry for John Hessin Clarke

, Lisbon Cemetery. FindaGrave.com. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

lawyer and judge who served as an Associate Justice

Associate justice or associate judge (or simply associate) is a judicial panel member who is not the chief justice in some jurisdictions. The title "Associate Justice" is used for members of the Supreme Court of the United States and some sta ...

of the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

from 1916 to 1922.

Early life

Born in New Lisbon, Ohio, Clarke was the third and youngest child and only son of John Clarke (1814–1884), a Quaker immigrant fromCounty Antrim

County Antrim (named after the town of Antrim, ) is one of six counties of Northern Ireland and one of the thirty-two counties of Ireland. Adjoined to the north-east shore of Lough Neagh, the county covers an area of and has a population ...

, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

who became a lawyer and judge in the United States, and his wife Melissa Hessin. He attended New Lisbon High School

New Lisbon High School (or NLHS) is a high school in New Lisbon, Juneau County, Wisconsin, United States. It is part of the School District of New Lisbon. The district serves students residing in the City of New Lisbon, Village of Hustler, and ...

and Western Reserve College, where he became a member of Delta Kappa Epsilon

Delta Kappa Epsilon (), commonly known as ''DKE'' or ''Deke'', is one of the oldest fraternities in the United States, with fifty-six active chapters and five active colonies across North America. It was founded at Yale College in 1844 by fiftee ...

fraternity. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States, and the most prestigious, due in part to its long history and academic selectivity. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal ...

in 1877. Clarke did not attend law school but studied the law under his father's direction and passed the bar exam ''cum laude'' in 1878.

After practicing law in New Lisbon for two years, Clarke moved to Youngstown, where he purchased a half-share in the '' Youngstown Vindicator''. The ''Vindicator'' was a Democratic newspaper and Clarke, a reform-minded Bourbon Democrat

Bourbon Democrat was a term used in the United States in the later 19th century (1872–1904) to refer to members of the Democratic Party who were ideologically aligned with fiscal conservatism or classical liberalism, especially those who su ...

, wrote several articles opposing the growing power of corporate monopolies and promoting such causes as civil-service reform. He also became involved in local party politics and civic causes. His efforts to prevent Calvin S. Brice

Calvin Stewart Brice (September 17, 1845 – December 15, 1898) was an American businessman and Democratic politician from Ohio. He is best remembered for his single term in the United States Senate, his role as chairman of the Democratic Nati ...

's renomination as the party's candidate for the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

in 1894 ended in failure, but he worked successfully to oppose the election of a Republican candidate for mayor of Youngstown who was a member of the American Protective Association. A "gold bug

"Gold bug" (sometimes spelled "goldbug") is a term frequently employed in the financial sector and among economists in reference to persons who are extremely bullish on the commodity gold as an investment and or a standard for measuring wealth. D ...

" in 1896, Clarke's opposition to William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

's nomination as the Democratic Party's presidential candidate was so great that he bolted the party and participated in the subsequent "Gold Bug" convention in Indianapolis that nominated Senator John M. Palmer later that year.

Progressive politician

Soon after the 1896 presidential election, Clarke moved toCleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the United States, U.S. U.S. state, state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County, Ohio, Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along ...

, where he became a partner in the law firm of Williamson and Cushing. The firm represented corporate and railroad interests, and Clarke soon demonstrated his worth, replacing senior partner Samuel W. Williamson as the general counsel for the New York, Chicago and St. Louis Railroad. Yet Clarke continued his involvement in the Democratic Party. His politics evolved during this period, as Clarke abandoned many of the political views of his youth, including those involving states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the ...

, and embraced instead the program of the emerging progressive movement

Progressivism holds that it is possible to improve human societies through political action. As a political movement, progressivism seeks to advance the human condition through social reform based on purported advancements in science, techn ...

. Clarke's political evolution during this period was facilitated considerably by his friendship with Cleveland mayor Tom L. Johnson

Tom Loftin Johnson (July 18, 1854 – April 10, 1911) was an American industrialist, Georgist politician, and important figure of the Progressive Era and a pioneer in urban political and social reform. He was a U.S. Representative from 1891 to ...

, who helped restore Clarke's standing within the state party after Clarke's previous failure to support Bryan's presidential bid.

In 1903, Johnson succeeded in taking control of the state Democratic Party, an effort which Clarke supported. At the party's convention that August, Clarke was nominated as the Democratic candidate for the United States Senate. Though an accomplished orator, Clarke's work as a railroad attorney, his opposition to Bryan's presidential candidacy seven years before, and his own personal limitations all contributed to his failure to upset his Republican rival, Mark Hanna, who won the balloting in the Ohio General Assembly

The Ohio General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Ohio. It consists of the 99-member Ohio House of Representatives and the 33-member Ohio Senate. Both houses of the General Assembly meet at the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus ...

by 115 votes to 25 for Clarke.

In the aftermath of his defeat, Clarke reduced his participation in party politics, focusing instead on his legal work for a time. Yet Clarke was soon back in the political arena, withdrawing from the partnership with Williamson and Cushing in 1907. His relationship with Johnson suffered after Clarke supported the successful candidacy of conservative Democrat Judson Harmon

Judson Harmon (February 3, 1846February 22, 1927) was an American Democratic politician from Ohio. He served as United States Attorney General under President Grover Cleveland and later served as the 45th governor of Ohio.

Early life

Harmon ...

for governor in 1908; in response, when nominating a candidate for the United States Senate race in 1910 Johnson passed over Clarke in favor of Atlee Pomerene, the eventual winner. Clarke's support for the incorporation of progressive reforms into the Ohio Constitution

The Constitution of the State of Ohio is the basic governing document of the State of Ohio, which in 1803 became the 17th state to join the United States of America. Ohio has had three constitutions since statehood was granted.

Ohio was crea ...

in 1911, however, helped to restore his standing among Ohio progressives. Clarke attempted to parlay this into a second run for a United States Senate seat early in 1914, but he faced opposition in the primary from Ohio Attorney General Timothy S. Hogan and by the spring appeared to be in danger of losing the race.

Judicial career

Federal judge

Clarke was in the middle of his primary campaign when he was appointed byPresident

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

on July 15, 1914 to fill a vacancy on the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

created by the resignation of William Louis Day. Clarke was the choice of both Woodrow Wilson and Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

James Clark McReynolds

James Clark McReynolds (February 3, 1862 – August 24, 1946) was an American lawyer and judge from Tennessee who served as United States Attorney General under President Woodrow Wilson and as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the Unite ...

, who felt that the position required a "first rate appointment" to deal with the backlog in the court's docket, and that Clarke's high standing before the Ohio bar marked him out as a man of "decided ability". Wilson also wanted a candidate who could be groomed as a prospective Supreme Court nominee, given the relative dearth of Democratic prospects on the federal bench after sixteen years of Republican presidents. He was confirmed by the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

on July 21, 1914, and received commission the same day.

Clarke soon vindicated their hopes in him, establishing himself as an effective judge. Though considered too formal and aloof by the attorneys before him, he cleaned up the backlogged docket and won their respect for his ability. His work was of the highest quality, with only five of the 662 suits tried before him reversed, and none of these for errors in the admission of evidence. Clarke himself enjoyed his time at the district level, finding his duties not too onerous and the variety of cases before him stimulating.

Associate Justice

Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes Sr. (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American statesman, politician and jurist who served as the 11th Chief Justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party, he previously was the ...

resigned to accept the Republican nomination for President. Wilson wanted to fill the seat by appointing his Attorney General, Thomas W. Gregory, but Gregory demurred and suggested Clarke instead. After having Newton Baker

Newton Diehl Baker Jr. (December 3, 1871 – December 25, 1937) was an American lawyer, Georgist,Noble, Ransom E. "Henry George and the Progressive Movement." The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, vol. 8, no. 3, 1949, pp. 259–269. w ...

(Wilson's Secretary of War and a close friend of Clarke's) speak with Clarke to confirm his opposition to trusts, Wilson offered Clarke the nomination. Though Clarke was reluctant to abandon trial for appellate work, he felt he could not pass on such an honor and accepted. Wilson sent his name to the Senate on July 14, 1916, and Clarke was confirmed by the United States Senate unanimously ten days later. He was sworn into office on October 9, 1916.

Clarke's years on the court were unhappy ones. Having enjoyed the autonomy of a trial court judge, he chafed at the routine of the Supreme Court, hating the arguments, the extended conferences, and the need to accommodate other justices' views when writing opinions. The record of his opinions during his five years on the bench reflected this dissatisfaction. While he issued 129 majority opinions, he also dissented 57 times in his short term on the court. While he enjoyed good relations with the other justices (and developed close friendships with William R. Day

William Rufus Day (April 17, 1849 – July 9, 1923) was an American diplomat and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1903 to 1922. Prior to his service on the Supreme Court, Day served as Unit ...

and Willis Van Devanter

Willis Van Devanter (April 17, 1859 – February 8, 1941) was an American lawyer who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1911 to 1937. He was a staunch conservative and was regarded as a part of the Fo ...

), he had an unpleasant relationship with Justice James Clark McReynolds

James Clark McReynolds (February 3, 1862 – August 24, 1946) was an American lawyer and judge from Tennessee who served as United States Attorney General under President Woodrow Wilson and as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the Unite ...

, one that subsequently contributed to his decision to leave the Court. Such was McReynolds's animosity towards Clarke that, when Clarke resigned, McReynolds refused to sign the official letter of regret over his departure.

Philosophically, Clarke demonstrated an affinity for legal realism

Legal realism is a naturalistic approach to law. It is the view that jurisprudence should emulate the methods of natural science, i.e., rely on empirical evidence. Hypotheses must be tested against observations of the world.

Legal realists ...

in his opinions. He often voted with Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. and Louis Brandeis

Louis Dembitz Brandeis (; November 13, 1856 – October 5, 1941) was an American lawyer and associate justice on the Supreme Court of the United States from 1916 to 1939.

Starting in 1890, he helped develop the " right to privacy" concep ...

, usually in dissent from the conservative majority dominant on the Court at that time, though Holmes's famous dissent from the '' Abrams v. United States'' decision was in response to Clarke's majority opinion. As a Progressive, he supported the power of both national and state authorities to regulate the economy, particularly with regard to regulating child labor

Child labour refers to the exploitation of children through any form of work that deprives children of their childhood, interferes with their ability to attend regular school, and is mentally, physically, socially and morally harmful. Such e ...

. His dissents on two cases, ''Hammer v. Dagenhart

''Hammer v. Dagenhart'', 247 U.S. 251 (1918), was a United States Supreme Court decision in which the Court struck down a federal law regulating child labor. The decision was overruled by ''United States v. Darby Lumber Co.'' (1941).

During the ...

'' and '' Bailey v. Drexel Furniture Company'', supported Congress's authority under the Commerce Clause

The Commerce Clause describes an enumerated power listed in the United States Constitution ( Article I, Section 8, Clause 3). The clause states that the United States Congress shall have power "to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and amon ...

(in the ''Hammer'' case) and the Taxing and Spending Clause (in the ''Bailey'' case) to address what Progressives saw as a major social problem. He also demonstrated his opposition to monopoly in ''United States v. Reading Company

The Reading Company ( ) was a Philadelphia-headquartered railroad that provided passenger and commercial rail transport in eastern Pennsylvania and neighboring states that operated from 1924 until its 1976 acquisition by Conrail.

Commonly called ...

'', in a ruling that became a prominent part of anti-trust law.

Resignation

Clarke's impact on the Court's jurisprudence was limited by his relatively brief service on it. On September 1, 1922, Clarke sent a letter to President Warren G. Harding announcing his intention to resign from the Court. His decision was motivated by a number of factors. Apart from his dissatisfaction with his work as a justice and his ongoing difficulties with McReynolds, Clarke had recently suffered the loss of his sisters Ida and Alice. Moreover, having witnessed the physical decline of Chief JusticeEdward Douglass White

Edward Douglass White Jr. (November 3, 1844 – May 19, 1921) was an American politician and jurist from Louisiana. White was a U.S. Supreme Court justice for 27 years, first as an associate justice from 1894 to 1910, then as the ninth chief ...

, he wished to avoid a similar deterioration while on the bench. Clarke would have few regrets about his decision, and informed his successor, George Sutherland, that the latter was embarking on "a dog's life."

Later years

Campaigning to join the League of Nations

In an interview three days after submitting his resignation, Clarke outlined a new cause he wanted to pursue – convincing Americans that the United States should join theLeague of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

. At the time, prospects for League entry were at a low ebb, its proponents having suffered the dual setback of the Senate's rejection of the Versailles Treaty and the election of the anti-League Republican Warren G. Harding as president in 1920. Clarke's public pronouncements gave their cause a new life, and in October 1922 he became the president of a new organization, the League of Nations Non-Partisan Association. Modeled after the British League of Nations Union, the Association's mission was to awaken the underlying support for joining the League that its founders believed existed within the United States and mobilize it to overcome the opposition to League participation. Through it, Clarke quickly emerged as Wilson's successor in the campaign for League membership.

Though Clarke committed himself to the cause with a series of speaking tours, he soon faced a number of challenges. Expenditures quickly outpaced the Association's funding, with limited resources squandered on building up an extensive organization. Though Clarke organized a restructuring in June 1923, a far greater problem lay in his underestimation of the task he faced. Contrary to Clarke's expectations, there was no latent undercurrent of support for joining the League, only skepticism and hostility to the idea. Addressing this required a far different level of commitment than Clarke expected to make, forcing him and the rest of the Association leadership to scale back on their goals. Focusing on the issue of entry into the World Court, Clarke continued to campaign for American involvement in international organizations and agreements for the remainder of the decade.

Retirement

By the end of 1927, Clarke's growingdeafness

Deafness has varying definitions in cultural and medical contexts. In medical contexts, the meaning of deafness is hearing loss that precludes a person from understanding spoken language, an audiological condition. In this context it is written ...

and frustration with the failures of the Association led him to resign from the Association's presidency. In retirement Clarke remained vigorous and active with a regimen of reading and travel. He also continued to participate in public service, becoming a trustee of Western Reserve University. In 1932, he backed a clandestine effort to nominate Newton Baker

Newton Diehl Baker Jr. (December 3, 1871 – December 25, 1937) was an American lawyer, Georgist,Noble, Ransom E. "Henry George and the Progressive Movement." The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, vol. 8, no. 3, 1949, pp. 259–269. w ...

as the Democratic presidential candidate, though after its failure Clarke became a supporter of the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Con ...

and President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Despite misgivings about the methods, he sympathized with the goals underlying the president's Supreme Court "packing" plan, and at Roosevelt's request Clarke made a radio broadcast in March 1937 in which he defended the constitutionality of the proposal.

In 1931 Clarke moved from Cleveland to San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United States ...

, where he lived in the El Cortez Apartment Hotel. It was there that he suffered a heart attack and died on March 22, 1945. He was later honored by his alma mater by having a residence hall, Clarke Tower, named after him on the Case Western Reserve campus. John Hessin Clarke was buried in the Lisbon Cemetery in Lisbon, Ohio., Lisbon Cemetery. FindaGrave.com. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

See also

*List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest-ranking judicial body in the United States. Its membership, as set by the Judiciary Act of 1869, consists of the chief justice of the United States and eight associate justices, any six of ...

References

Bibliography

* * *External links

* , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Clarke, John Hessin 1857 births 1945 deaths 20th-century American judges American people of Scotch-Irish descent Case Western Reserve University alumni Judges of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Ohio Ohio Democrats Ohio lawyers Lawyers from Cleveland People from Lisbon, Ohio People from San Diego Lawyers from Youngstown, Ohio United States district court judges appointed by Woodrow Wilson Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States United States federal judges admitted to the practice of law by reading law Western Reserve Academy alumni