John Gibson Lockhart on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Gibson Lockhart (12 June 1794 – 25 November 1854) was a Scottish writer and editor. He is best known as the author of the seminal, and much-admired, seven-volume biography of his father-in-law

John Gibson Lockhart (12 June 1794 – 25 November 1854) was a Scottish writer and editor. He is best known as the author of the seminal, and much-admired, seven-volume biography of his father-in-law

In 1813, Lockhart took a first in classics then, for two years after leaving Oxford, lived in

In 1813, Lockhart took a first in classics then, for two years after leaving Oxford, lived in

At this time he was living at 25 Northumberland Street in Edinburgh's

At this time he was living at 25 Northumberland Street in Edinburgh's

In 1818, Lockhart met Sir Walter Scott, who introduced him to his family. Lockhart married Scott's eldest daughter Sophia in April 1820. It was a happy marriage, with winters spent in Edinburgh and summers at Chiefswood, a cottage on Scott's Abbotsford estate, where the Lockhart's first child John Hugh ‘Johnnie’ was born. John Hugh was born with

In 1818, Lockhart met Sir Walter Scott, who introduced him to his family. Lockhart married Scott's eldest daughter Sophia in April 1820. It was a happy marriage, with winters spent in Edinburgh and summers at Chiefswood, a cottage on Scott's Abbotsford estate, where the Lockhart's first child John Hugh ‘Johnnie’ was born. John Hugh was born with

History of the Lodge Canongate Kilwinning, No.2, compiled from the records 1677–1888

By Alan MacKenzie. 1888. p. 24.

Portrait, with wife

(daughter of

Photograph of John Gibson Lockhart at National Galleries of Scotland

Lodge Canongate Kilwinning, No. 2. (Edinburgh)

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Lockhart, John Gibson 1794 births 1854 deaths People from North Lanarkshire Members of the Faculty of Advocates Scottish editors Scottish Freemasons Scottish translators 19th-century Scottish novelists 19th-century Scottish writers Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Alumni of the University of Glasgow Alumni of Balliol College, Oxford Scottish biographers People educated at the High School of Glasgow 19th-century British translators Scott family of Abbotsford

John Gibson Lockhart (12 June 1794 – 25 November 1854) was a Scottish writer and editor. He is best known as the author of the seminal, and much-admired, seven-volume biography of his father-in-law

John Gibson Lockhart (12 June 1794 – 25 November 1854) was a Scottish writer and editor. He is best known as the author of the seminal, and much-admired, seven-volume biography of his father-in-law Sir Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels '' Ivanhoe'', '' Rob Roy ...

: ''Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, Bart''

Early years

Lockhart was born on 12 June 1794 in themanse

A manse () is a clergy house inhabited by, or formerly inhabited by, a minister, usually used in the context of Presbyterian, Methodist, Baptist and other Christian traditions.

Ultimately derived from the Latin ''mansus'', "dwelling", from ' ...

of Cambusnethan House in Lanarkshire

Lanarkshire, also called the County of Lanark ( gd, Siorrachd Lannraig; sco, Lanrikshire), is a historic county, lieutenancy area and registration county in the central Lowlands of Scotland.

Lanarkshire is the most populous county in Scotl ...

to Dr John Lockhart, who transferred in 1796 to Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popu ...

, and was appointed minister in the Presbyterian Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Reformation of 1560, when it split from the Catholic Church ...

, and his second wife Elizabeth Gibson (1767–1834), daughter of Margaret Mary Pringle and Reverend John Gibson, minister of St Cuthbert's, Edinburgh.

He was the younger paternal half-brother of the politician William Lockhart.

Lockhart attended Glasgow High School, where he showed himself clever rather than industrious. He fell into ill-health, and had to be removed from school before he was 12; but on his recovery he was sent at this early age to the University of Glasgow

, image = UofG Coat of Arms.png

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms

Flag

, latin_name = Universitas Glasguensis

, motto = la, Via, Veritas, Vita

, ...

, and displayed so much precocious learning, especially in Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, that he was offered a Snell exhibition at Oxford. He was not yet 14 when he entered Balliol College, Oxford

Balliol College () is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. One of Oxford's oldest colleges, it was founded around 1263 by John I de Balliol, a landowner from Barnard Castle in County Durham, who provided the ...

, where he acquired a great store of knowledge outside the regular curriculum. He read French, Italian, German and Spanish, was interested in antiquities

Antiquities are objects from antiquity, especially the civilizations of the Mediterranean: the Classical antiquity of Greece and Rome, Ancient Egypt and the other Ancient Near Eastern cultures. Artifacts from earlier periods such as the Meso ...

, and became versed in heraldic

Heraldry is a discipline relating to the design, display and study of armorial bearings (known as armory), as well as related disciplines, such as vexillology, together with the study of ceremony, rank and pedigree. Armory, the best-known branc ...

and genealogical

Genealogy () is the study of families, family history, and the tracing of their lineages. Genealogists use oral interviews, historical records, genetic analysis, and other records to obtain information about a family and to demonstrate kin ...

lore.

''Blackwood's Magazine'' and a literary duel

In 1813, Lockhart took a first in classics then, for two years after leaving Oxford, lived in

In 1813, Lockhart took a first in classics then, for two years after leaving Oxford, lived in Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popu ...

before settling to the study of Scots law

Scots law () is the legal system of Scotland. It is a hybrid or mixed legal system containing civil law and common law elements, that traces its roots to a number of different historical sources. Together with English law and Northern Ireland ...

at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 1 ...

where, in 1816, he was elected to the Faculty of Advocates

The Faculty of Advocates is an independent body of lawyers who have been admitted to practise as advocates before the courts of Scotland, especially the Court of Session and the High Court of Justiciary. The Faculty of Advocates is a constit ...

. A tour on the continent

A continent is any of several large landmasses. Generally identified by convention rather than any strict criteria, up to seven geographical regions are commonly regarded as continents. Ordered from largest in area to smallest, these seven ...

in 1817, when he visited Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as tr ...

at Weimar

Weimar is a city in the state of Thuringia, Germany. It is located in Central Germany between Erfurt in the west and Jena in the east, approximately southwest of Leipzig, north of Nuremberg and west of Dresden. Together with the neighbouri ...

, was made possible when he was hired by the publisher William Blackwood

William Blackwood (20 November 177616 September 1834) was a Scottish publisher who founded the firm of William Blackwood and Sons.

Life

Blackwood was born in Edinburgh on 20 November 1776. At the age of 14 he was apprenticed to a firm of book ...

to translate Friedrich Schlegel's ''Lectures on the History of Literature''.

Edinburgh was then the stronghold of the Whig party, whose organ was the ''Edinburgh Review

The ''Edinburgh Review'' is the title of four distinct intellectual and cultural magazines. The best known, longest-lasting, and most influential of the four was the third, which was published regularly from 1802 to 1929.

''Edinburgh Review'' ...

''; and it was not till 1817 that the Scottish Tories

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

found a means of expression in ''Blackwood's Magazine

''Blackwood's Magazine'' was a British magazine and miscellany printed between 1817 and 1980. It was founded by the publisher William Blackwood and was originally called the ''Edinburgh Monthly Magazine''. The first number appeared in April 1817 ...

''. After changing its name following a hum-drum launch as the ''Edinburgh Monthly Magazine'', ''Blackwood's'' suddenly electrified Edinburgh with an outburst of brilliant criticism. Lockhart (along with John Wilson (Christopher North)), had joined its staff upon his return from Europe in 1817, and contributed to the caustic and aggressive articles that marked the early years of ''Blackwood's''. Lockhart wrote virulent articles on "The Cockney School of Poetry" of Leigh Hunt

James Henry Leigh Hunt (19 October 178428 August 1859), best known as Leigh Hunt, was an English critic, essayist and poet.

Hunt co-founded '' The Examiner'', a leading intellectual journal expounding radical principles. He was the centre ...

, Keats

John Keats (31 October 1795 – 23 February 1821) was an English poet of the second generation of Romantic poets, with Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley. His poems had been in publication for less than four years when he died of tuberculos ...

and their contemporaries, although he did show appreciation of Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake ...

and Wordsworth, and he praised Percy Bysshe Shelley

Percy Bysshe Shelley ( ; 4 August 17928 July 1822) was one of the major English Romantic poets. A radical in his poetry as well as in his political and social views, Shelley did not achieve fame during his lifetime, but recognition of his achi ...

, calling him "a man of genius".

One of the main literary organs of the Cockney School was ''The London Magazine''. Its editor, John Scott, felt that ''Blackwood’s'' hounding of Keats had contributed to his 1821 death, at age 26. Scott also felt it was his duty to defend his authors against Lockhart and ''Blackwood’s''. To that end, he published an attack of Lockhart and ''Blackwood’s''; Lockhart promptly asked a London friend, Jonathan Henry Christie, to visit Scott and demand an apology. Scott refused; a series of letters were exchanged and the argument evolved into Scott’s insistence that Lockhart admit that he (Lockhart) was, in fact, the anonymous editor of ''Blackwood’s'' (it was common practice at the time to act an editor, and/or as a writer, anonymously, or using a pseudonym). According to the papers of Scott’s friend Peter George Patmore

Peter George Patmore (baptized 1786; died 1855) was an English author.

Life

The son of Peter Patmore, a dealer in plate and jewellery, he was born in his father's house on Ludgate Hill, London. Patmore refused to go into his father's business, an ...

, who tried to negotiate a truce and kept a meticulous record of the matter, not only did Lockhart refuse to admit to his editorship, but he responded with "abusive epithets". With both men seeing their honour at stake, there was no going back and, on 16 February 1821, they proceeded with the duel. But Lockhart did not attend; Jonathan Christie stepped into his place with his friend, James Traill, as his second. John Scott was wounded and died ten days later. Christie and Traill were tried for murder. They were acquitted, but Christie’s life was ruined. Lockhart was not blamed.

Literary contributions

Between 1818 and 1825 Lockhart worked indefatigably. In 1819 ''Peter's Letters to his Kinsfolk'' appeared, and in 1822 he edited Peter Motteux's edition of ''Don Quixote

is a Spanish epic novel by Miguel de Cervantes. Originally published in two parts, in 1605 and 1615, its full title is ''The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha'' or, in Spanish, (changing in Part 2 to ). A founding work of West ...

'', to which he prefixed a life of author Miguel de Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (; 29 September 1547 (assumed) – 22 April 1616 NS) was an Early Modern Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-eminent novelists. He is best kno ...

. Four novels followed: ''Valerius'' in 1821, ''Some Passages in the Life of Mr. Adam Blair Minister of Gospel at Cross Meikle'' in 1822, ''Reginald Dalton'' in 1823 and ''Matthew Wald'' in 1824. However, his strength did not lie in novel writing. He also contributed to ''Blackwood'' translations of Spanish ballads, which in 1823 were published separately.

In 1825 Lockhart accepted the editorship of the '' Quarterly Review'', which had been in the hands of Sir John Taylor Coleridge since William Gifford's resignation in 1824.

At this time he was living at 25 Northumberland Street in Edinburgh's

At this time he was living at 25 Northumberland Street in Edinburgh's New Town

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator ...

. In 1825 he sold the house to Andrew

Andrew is the English form of a given name common in many countries. In the 1990s, it was among the top ten most popular names given to boys in English-speaking countries. "Andrew" is frequently shortened to "Andy" or "Drew". The word is derive ...

and George Combe.

As the next heir to the Scotland property belonging to his unmarried half-brother, Milton Lockhart, he was sufficiently independent. In London he had social success, and was recognised as an editor. He contributed largely to the ''Quarterly Review'' himself, particularly biographical articles. He showed the old, railing spirit in an article in the ''Quarterly'' against Tennyson

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson (6 August 1809 – 6 October 1892) was an English poet. He was the Poet Laureate during much of Queen Victoria's reign. In 1829, Tennyson was awarded the Chancellor's Gold Medal at Cambridge for one of his ...

's ''Poems'' of 1833. He continued to write for ''Blackwood's'', producing for ''Constable's Miscellany

''Constable's Miscellany'' was a part publishing serial established by Archibald Constable. Three numbers made up a volume; many of the works were divided into several volumes. The price of a number was one shilling. The full series title was ''C ...

'' Vol. XXIII in 1828 a controversial ''Life'' of Robert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 175921 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the best known of the poets who hav ...

. Snyder wrote of it, "The best that one can say of it today...is that it occasioned Carlyle's review. It is inexcusably inaccurate from beginning to end, at times demonstrably mendacious, and should never be trusted in any respect or detail."

Later works

Lockhart undertook the editorial supervision of ''Murray's Family Library

''Murray's Family Library'' was a series of non-fiction works published from 1829 to 1834, by John Murray, in 51 volumes. The series editor was John Gibson Lockhart, who also wrote the first book, a biography of Napoleon. The books were priced ...

'', which he opened in 1829 with a ''History of Napoleon''.

However, his major work, and the one for which he is known, is the ''Life of Sir Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels '' Ivanhoe'', '' Rob Roy ...

'' (7 vols, 1837–1838; 2nd ed., 10 vols., 1839). This biography included the publishing of a great number of Scott's letters. Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, ...

assessed it in a criticism contributed to the ''London and Westminster Review'' (1837). Lockhart's account of the business transactions between Scott and the Ballantynes and Constable caused an outcry; and in the discussion that followed he showed bitterness in his pamphlet ''The Ballantyne Humbug handled''. The ''Life of Scott'' has been called, after Boswell's '' Life of Samuel Johnson'', the most admirable biography in the English language. The proceeds, which were considerable, Lockhart resigned for the benefit of Scott's creditors.

Family and final years

In 1818, Lockhart met Sir Walter Scott, who introduced him to his family. Lockhart married Scott's eldest daughter Sophia in April 1820. It was a happy marriage, with winters spent in Edinburgh and summers at Chiefswood, a cottage on Scott's Abbotsford estate, where the Lockhart's first child John Hugh ‘Johnnie’ was born. John Hugh was born with

In 1818, Lockhart met Sir Walter Scott, who introduced him to his family. Lockhart married Scott's eldest daughter Sophia in April 1820. It was a happy marriage, with winters spent in Edinburgh and summers at Chiefswood, a cottage on Scott's Abbotsford estate, where the Lockhart's first child John Hugh ‘Johnnie’ was born. John Hugh was born with spina bifida

Spina bifida (Latin for 'split spine'; SB) is a birth defect in which there is incomplete closing of the spine and the membranes around the spinal cord during early development in pregnancy. There are three main types: spina bifida occulta, men ...

and spent much of his time with his grandfather, listening to Scott’s stories about Scottish history, hence Scott’s book, ''Tales of a Grandfather

''Tales of a Grandfather'' is a series of books on the history of Scotland, written by Sir Walter Scott, who originally intended it for his grandson. The books were published between 1828 and 1830 by A & C Black. In the 19th century, the study ...

''. Johnnie died in 1831, at age eleven. A baby girl born to the Lockharts died soon after birth. Sir Walter died in 1832; Sophia died suddenly in 1837, at age 38. Lockhart struggled with the loss of his parents and sister. His third child was Walter Scott Lockhart, who became an army officer, but fell into a bad company, ruined his health, and died in his father’s arms in January 1853 at the age of 26. Lockhart became seriously depressed, almost starving himself to death. He resigned his editorship of the ''Quarterly Review'' and spent some time in Italy, but returned without recovering his health.

He moved back to Scotland to live with his only surviving child Charlotte, who was settled at Abbotsford with her husband James Hope-Scott. The two had converted to Catholicism, which made for an uncomfortable atmosphere in the home (Charlotte would die in childbirth in 1858, at age 30). Lockhart died a few weeks after his arrival at Abbotsford, on 25 November 1854. He was buried at Dryburgh Abbey

Dryburgh Abbey, near Dryburgh on the banks of the River Tweed in the Scottish Borders, was nominally founded on 10 November (Martinmas) 1150 in an agreement between Hugh de Morville, Constable of Scotland, and the Premonstratensian canons regu ...

, beside his son and father-in-law.

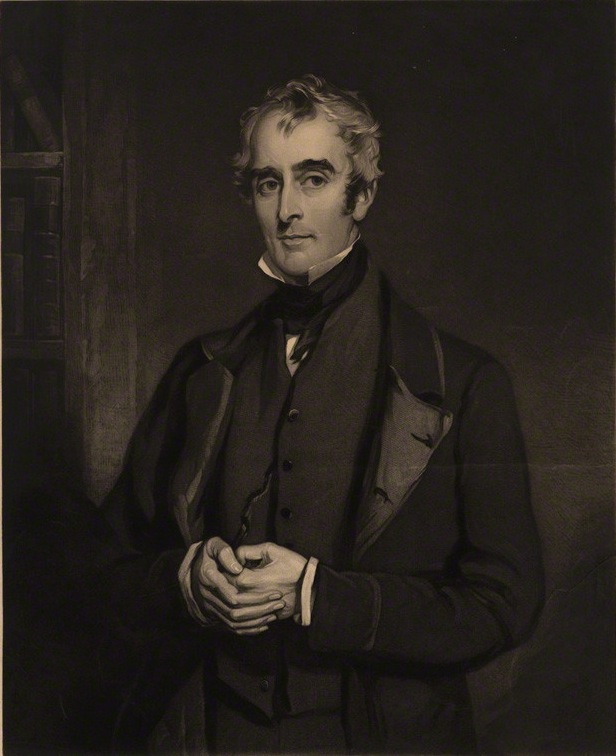

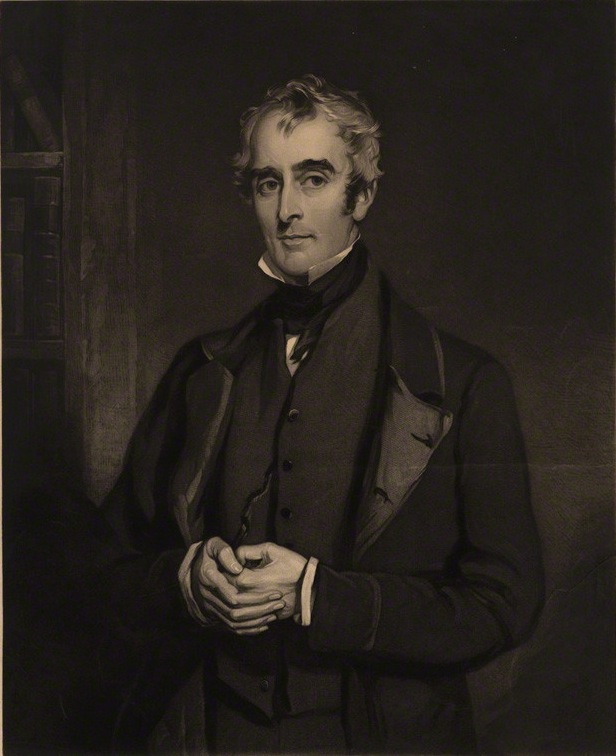

His obituary in ''The Times'', dated 9 December 1854, included the paragraph ''"Endowed with the very highest order of manly beauty, both of features and expression, he retained the brilliancy of youth and a stately strength of person comparatively unimpaired in ripened life; and then, though sorrow and sickness suddenly brought on a premature old age which none could witness unmoved, yet the beauty of the head and of the bearing so far gained in melancholy loftiness of expression what they lost in animation, that the last phase, whether to the eye of painter or of anxious friend, seemed always the finest."''

Freemasonry

Like his father-in-law he was a Freemason although he was initiated in a different Edinburgh Lodge – Lodge Canongate Kilwinning, No. 2, on 26 January 1826.By Alan MacKenzie. 1888. p. 24.

Legacy

Robert Scott Lauder

Robert Scott Lauder (25 June 1803 – 21 April 1869) was a Scottish artist who described himself as a "historical painter". He was one of the original members of the Royal Scottish Academy.

Life and work

Lauder was born at Silvermills, E ...

painted two portraits of Lockhart, one of him alone, and the other with Charlotte Scott.

The composer Hubert Parry

Sir Charles Hubert Hastings Parry, 1st Baronet (27 February 18487 October 1918) was an English composer, teacher and historian of music. Born in Richmond Hill in Bournemouth, Parry's first major works appeared in 1880. As a composer he is be ...

set one of Lockhart's poems to music, " There is an old belief", as part of his collection of six choral motet

In Western classical music, a motet is mainly a vocal musical composition, of highly diverse form and style, from high medieval music to the present. The motet was one of the pre-eminent polyphonic forms of Renaissance music. According to Ma ...

s, ''Songs of Farewell

''Songs of Farewell'' is a set of six choral motets by the British composer Hubert Parry. The pieces were composed between 1916 and 1918 and were among his last compositions before his death.

Background

The songs were written during the First W ...

''. The pieces were first performed at a concert at the Royal College of Music

The Royal College of Music is a conservatoire established by royal charter in 1882, located in South Kensington, London, UK. It offers training from the undergraduate to the doctoral level in all aspects of Western Music including perform ...

on 22 May 1916. The song/poem was later sung at the composer's funeral in St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglicanism, Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London ...

on 23 February 1919.

References

* Andrew Lang, ''The Life of J. G. Lockhart'', 2 vols., London and New York, 1897 * Alfred William Pollard, ''The Life of Scott'', 1900External links

* *Portrait, with wife

(daughter of

Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels '' Ivanhoe'', '' Rob Roy ...

), by Robert Scott Lauder

Robert Scott Lauder (25 June 1803 – 21 April 1869) was a Scottish artist who described himself as a "historical painter". He was one of the original members of the Royal Scottish Academy.

Life and work

Lauder was born at Silvermills, E ...

at the National Gallery of Scotland

The Scottish National Gallery (formerly the National Gallery of Scotland) is the national art gallery of Scotland. It is located on The Mound in central Edinburgh, close to Princes Street. The building was designed in a neoclassical style by W ...

Photograph of John Gibson Lockhart at National Galleries of Scotland

Lodge Canongate Kilwinning, No. 2. (Edinburgh)

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Lockhart, John Gibson 1794 births 1854 deaths People from North Lanarkshire Members of the Faculty of Advocates Scottish editors Scottish Freemasons Scottish translators 19th-century Scottish novelists 19th-century Scottish writers Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Alumni of the University of Glasgow Alumni of Balliol College, Oxford Scottish biographers People educated at the High School of Glasgow 19th-century British translators Scott family of Abbotsford