John Fulton Reynolds on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

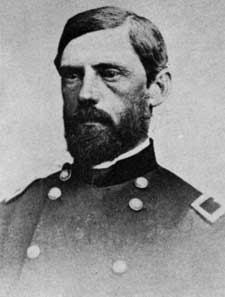

John Fulton Reynolds (September 21, 1820 – July 1, 1863)Eicher, pp. 450-51. was a career

Soon after the start of the Civil War, Reynolds was offered the position as aide-de-camp to Lt. Gen.

Soon after the start of the Civil War, Reynolds was offered the position as aide-de-camp to Lt. Gen.

Upon his return, Reynolds was given command of the Pennsylvania Reserves Division, whose commander, McCall, had been captured just two days after Reynolds. The V Corps joined the

Upon his return, Reynolds was given command of the Pennsylvania Reserves Division, whose commander, McCall, had been captured just two days after Reynolds. The V Corps joined the

On the morning of July 1, 1863, Reynolds was commanding the "left wing" of the Army of the Potomac, with operational control over the I, III, and XI Corps, and Brig. Gen.

On the morning of July 1, 1863, Reynolds was commanding the "left wing" of the Army of the Potomac, with operational control over the I, III, and XI Corps, and Brig. Gen.  Reynolds' body was immediately transported from Gettysburg to

Reynolds' body was immediately transported from Gettysburg to

''The Generals of Gettysburg''

Campbell, CA: Savas Publishing, 1998. . * Trudeau, Noah Andre. ''Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage''. New York: HarperCollins, 2002. . * Tucker, Glenn. ''High Tide at Gettysburg''. Dayton, OH: Morningside House, 1983. . First published 1958 by Bobbs-Merrill Co. * Warner, Ezra J. ''Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders''. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. . * Welcher, Frank J. ''The Union Army, 1861–1865 Organization and Operations''. Vol. 1, ''The Eastern Theater''. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989. .

Reynolds family genealogy

from the Cullum biographies

Grand Army of the Republic in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania

{{DEFAULTSORT:Reynolds, John F. 1820 births 1863 deaths People from Lancaster, Pennsylvania Union Army generals Union military personnel killed in the American Civil War People of Pennsylvania in the American Civil War American military personnel of the Mexican–American War American Civil War prisoners of war United States Military Academy alumni Commandants of the Corps of Cadets of the United States Military Academy Pennsylvania Reserves Deaths by firearm in Pennsylvania Rogue River Wars

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

officer and a general

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

. One of the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

's most respected senior commanders, he played a key role in committing the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confedera ...

to the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the Po ...

and was killed at the start of the battle.

Early life and career

Reynolds was born inLancaster, Pennsylvania

Lancaster, ( ; pdc, Lengeschder) is a city in and the county seat of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. It is one of the oldest inland cities in the United States. With a population at the 2020 census of 58,039, it ranks 11th in population amon ...

, one of nine surviving children of John Reynolds (1787–1853) and Lydia Moore Reynolds (1794–1843). Two of his brothers were James LeFevre Reynolds, Quartermaster General of Pennsylvania, and Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

Will Reynolds. Prior to his military training, Reynolds studied in nearby Lititz, about from his home in Lancaster. Next he attended a school in Long Green, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, and finally the Lancaster County Academy.

Reynolds was nominated to the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

in 1837 by Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

, a family friend, and graduated 26th of 50 cadets in the class of 1841. He was commissioned a brevet

Brevet may refer to:

Military

* Brevet (military), higher rank that rewards merit or gallantry, but without higher pay

* Brevet d'état-major, a military distinction in France and Belgium awarded to officers passing military staff college

* Aircre ...

second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

in the 3rd U.S. Artillery, assigned to Fort McHenry

Fort McHenry is a historical American coastal pentagonal bastion fort on Locust Point, now a neighborhood of Baltimore, Maryland. It is best known for its role in the War of 1812, when it successfully defended Baltimore Harbor from an attack b ...

. From 1842 to 1845 he was assigned to St. Augustine, Florida, and Fort Moultrie, South Carolina

Fort Moultrie is a series of fortifications on Sullivan's Island, South Carolina, built to protect the city of Charleston, South Carolina. The first fort, formerly named Fort Sullivan, built of palmetto logs, inspired the flag and n ...

, before joining Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

's army at Corpus Christi, Texas

Corpus Christi (; Ecclesiastical Latin: "'' Body of Christ"'') is a coastal city in the South Texas region of the U.S. state of Texas and the county seat and largest city of Nueces County, it also extends into Aransas, Kleberg, and San Patrici ...

, for the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

. He was awarded two brevet promotions in Mexico—to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

for gallantry at Monterrey

Monterrey ( , ) is the capital and largest city of the northeastern state of Nuevo León, Mexico, and the third largest city in Mexico behind Guadalajara and Mexico City. Located at the foothills of the Sierra Madre Oriental, the city is anchor ...

and to major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

for Buena Vista Buena Vista, meaning "good view" in Spanish, may refer to:

Places Canada

*Bonavista, Newfoundland and Labrador, with the name being originally derived from “Buena Vista”

*Buena Vista, Saskatchewan

*Buena Vista, Saskatoon, a neighborhood in ...

, where his section of guns prevented the Mexican cavalry from outflanking the American left. During the war, he became friends with fellow officers Winfield Scott Hancock

Winfield Scott Hancock (February 14, 1824 – February 9, 1886) was a United States Army officer and the Democratic nominee for President of the United States in 1880. He served with distinction in the Army for four decades, including service ...

and Lewis A. Armistead

Lewis Addison Armistead (February 18, 1817 – July 5, 1863) was a career United States Army officer who became a brigadier general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. On July 3, 1863, as part of Pickett's Charge during ...

.

On his return from Mexico, Reynolds was assigned to Fort Preble

Fort Preble was a military fort in South Portland, Maine, United States, built in 1808 and progressively added to through 1906. The fort was active during all major wars from the War of 1812 through World War II. The fort was deactivated in 1950 ...

, Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and north ...

; New Orleans, Louisiana

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

; and Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Fort Lafayette

Fort Lafayette was an island coastal fortification in the Narrows of New York Harbor, built offshore from Fort Hamilton at the southern tip of what is now Bay Ridge in the New York City borough of Brooklyn. The fort was built on a natural island ...

, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

. He was next sent west to Fort Orford, Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

, in 1855, and participated in the Rogue River Wars

The Rogue River Wars were an armed conflict in 1855–1856 between the U.S. Army, local militias and volunteers, and the Native American tribes commonly grouped under the designation of Rogue River Indians, in the Rogue River Valley area o ...

of 1856 and the Utah War

The Utah War (1857–1858), also known as the Utah Expedition, Utah Campaign, Buchanan's Blunder, the Mormon War, or the Mormon Rebellion was an armed confrontation between Mormon settlers in the Utah Territory and the armed forces of the US go ...

with the Mormon

Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the movement split into several ...

s in 1857–58. He was the Commandant of Cadets at West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

from September 1860 to June 1861, while also serving as an instructor of artillery, cavalry, and infantry tactics. During his return from the West, Reynolds became engaged to Katherine May Hewitt. Since they were from different religious denominations—Reynolds was a Protestant, Hewitt a Catholic—the engagement was kept a secret and Hewitt's parents did not learn about it until after Reynolds' death.

Civil War

Early assignments and the Seven Days

Soon after the start of the Civil War, Reynolds was offered the position as aide-de-camp to Lt. Gen.

Soon after the start of the Civil War, Reynolds was offered the position as aide-de-camp to Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

, but declined. He was appointed lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

of the 14th U.S. Infantry, but before he could engage with that unit, he was promoted to brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

on August 20, 1861, and ordered to report to Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

While in transit, his orders were changed to report to Cape Hatteras Inlet, North Carolina. Maj. Gen.

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

intervened with the Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

to get his orders changed once again, assigning him to the newly formed Army of the Potomac. His first assignment was with a board that examined the qualifications of volunteer officers, but he soon was given command of a brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute a division.

Br ...

of Pennsylvania Reserves

The Pennsylvania Reserves were an infantry division in the Union Army during the American Civil War. Noted for its famous commanders and high casualties, it served in the Eastern Theater, and fought in many important battles, including Antietam ...

.Carney, p. 1632.

As McClellan's army moved up the Virginia Peninsula

The Virginia Peninsula is a peninsula in southeast Virginia, USA, bounded by the York River, James River, Hampton Roads and Chesapeake Bay. It is sometimes known as the ''Lower Peninsula'' to distinguish it from two other peninsulas to the ...

in the 1862 Peninsula Campaign, Reynolds occupied and became military governor of Fredericksburg, Virginia

Fredericksburg is an independent city located in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 27,982. The Bureau of Economic Analysis of the United States Department of Commerce combines the city of Fredericksburg wi ...

. His brigade was then ordered to join the V Corps 5th Corps, Fifth Corps, or V Corps may refer to:

France

* 5th Army Corps (France)

* V Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* V Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Ar ...

at Mechanicsville, just before the start of the Seven Days Battles

The Seven Days Battles were a series of seven battles over seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army of the Potomac, command ...

. The brigade was hit hard by the Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

attack of June 26 at the Battle of Beaver Dam Creek, but their defensive line held and Reynolds later received a letter of commendation from his division commander, Brig. Gen.

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

George A. McCall.

The Confederate attack continued on June 27 and Reynolds, exhausted from the Battle of Gaines' Mill

The Battle of Gaines' Mill, sometimes known as the Battle of Chickahominy River, took place on June 27, 1862, in Hanover County, Virginia, as the third of the Seven Days Battles (Peninsula Campaign) of the American Civil War. Following the inconc ...

and two days without sleep, was captured in Boatswain's Swamp, Virginia. Thinking he was in a place of relative safety, he fell asleep and was not aware that his retreating troops left him behind. He was extremely embarrassed when brought before the Confederate general of the capturing troops; D.H. Hill was an Army friend and colleague from before the war. Hill allegedly told him, "Reynolds, do not feel so bad about your capture, it is the fate of wars." Reynolds was transported to Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

and held at Libby Prison

Libby Prison was a Confederate prison at Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. In 1862 it was designated to hold officer prisoners from the Union Army. It gained an infamous reputation for the overcrowded and harsh conditions. Prison ...

, but was quickly exchanged on August 15 (for Lloyd Tilghman

Lloyd Tilghman (January 26, 1816 – May 16, 1863) was a Confederate general in the American Civil War.

A railroad construction engineer by background, he was selected by the Confederate government to build two forts to defend the Tennessee ...

).

Second Bull Run, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville

Upon his return, Reynolds was given command of the Pennsylvania Reserves Division, whose commander, McCall, had been captured just two days after Reynolds. The V Corps joined the

Upon his return, Reynolds was given command of the Pennsylvania Reserves Division, whose commander, McCall, had been captured just two days after Reynolds. The V Corps joined the Army of Virginia

The Army of Virginia was organized as a major unit of the Union Army and operated briefly and unsuccessfully in 1862 in the American Civil War. It should not be confused with its principal opponent, the Confederate Army of ''Northern'' Virginia ...

, under Maj. Gen. John Pope, at Manassas. On the second day of the Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confederate ...

, while most of the Union Army was retreating, Reynolds led his men in a last-ditch stand on Henry House Hill, site of the great Union debacle at First Bull Run

The First Battle of Bull Run (the name used by Union forces), also known as the Battle of First Manassas

the previous year. Waving the flag of the 2nd Reserves regiment, he yelled, "Now boys, give them the steel, charge bayonets, double quick!" His counterattack halted the Confederate advance long enough to give the Union Army time to retreat in a more orderly fashion, arguably the most important factor in preventing its complete destruction.Tagg, p. 10.

At the request of Pennsylvania Governor

The governor of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is the head of state and head of government of the U.S. state, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, as well as commander-in-chief of the Commonwealth's military forces.

The governor has a duty to enforc ...

Andrew G. Curtin

Andrew Gregg Curtin (April 22, 1815/1817October 7, 1894) was a U.S. lawyer and politician. He served as the Governor of Pennsylvania during the Civil War, helped defend his state during the Gettysburg Campaign, and led organization of the cr ...

, Reynolds was given command of the Pennsylvania Militia during General Robert E. Lee's invasion of Maryland. Generals McClellan and Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was an American Civil War general for the Union, chiefly remembered for his decisive defeat by Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863.

Hooker had serv ...

complained that "a scared governor ought not to be permitted to destroy the usefulness of an entire division," but the governor prevailed and Reynolds spent two weeks in Pennsylvania drilling old men and boys, missing the Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union G ...

. However, he returned to the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confedera ...

in late 1862 and assumed command of the I Corps I Corps, 1st Corps, or First Corps may refer to:

France

* 1st Army Corps (France)

* I Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* I Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French A ...

. One of his divisions, commanded by Maj. Gen. George G. Meade

George Gordon Meade (December 31, 1815 – November 6, 1872) was a United States Army officer and civil engineer best known for decisively defeating Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Gettysburg in the American Civil War. H ...

, made the only breakthrough at the Battle of Fredericksburg

The Battle of Fredericksburg was fought December 11–15, 1862, in and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. The combat, between the Union Army of the Potomac commanded by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnsi ...

, but Reynolds did not reinforce Meade with his other two divisions and the attack failed; Reynolds did not receive a clear understanding from Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin about his role in the attack. After the battle, Reynolds was promoted to major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

of volunteers, with a date of rank of November 29, 1862.

At the Battle of Chancellorsville

The Battle of Chancellorsville, April 30 – May 6, 1863, was a major battle of the American Civil War (1861–1865), and the principal engagement of the Chancellorsville campaign.

Chancellorsville is known as Lee's "perfect battle" because h ...

in May 1863, Reynolds clashed with Maj. Gen. Hooker, his predecessor at I Corps, but by this time the commander of the Army of the Potomac. Hooker originally placed the I Corps on the extreme left of the Union line, southeast of Fredericksburg, hoping to threaten and distract the Confederate right. On May 2, Hooker changed his mind and ordered the corps to conduct a daylight march nearly 20 miles to swing around and become the extreme right flank of the army, to the northwest of the XI Corps 11 Corps, 11th Corps, Eleventh Corps, or XI Corps may refer to:

* 11th Army Corps (France)

* XI Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* XI Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial German Army

* ...

. The march was delayed by faulty communications and by the need to move stealthily to avoid Confederate contact. Thus, the I Corps was not yet in position when the XI Corps was surprised and overrun by Lt. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's flank attack, a setback that destroyed Hooker's nerve for offensive action. Hooker called a council of war

A council of war is a term in military science that describes a meeting held to decide on a course of action, usually in the midst of a battle. Under normal circumstances, decisions are made by a commanding officer, optionally communicated ...

on May 4 in which Reynolds voted to proceed with the battle, but although the vote was three to two for offensive action, Hooker decided to retreat. Reynolds, who had gone to sleep after giving his proxy vote to Meade, woke up and muttered loud enough for Hooker to hear, "What was the use of calling us together at this time of night when he intended to retreat anyhow?" The 17,000-man I Corps was not engaged at Chancellorsville and suffered only 300 casualties during the entire campaign.

Reynolds joined several of his fellow officers in urging that Hooker be replaced, in the same way he had spoken out against Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside

Ambrose Everett Burnside (May 23, 1824 – September 13, 1881) was an American army officer and politician who became a senior Union general in the Civil War and three times Governor of Rhode Island, as well as being a successful inventor ...

after Fredericksburg. On the previous occasion, Reynolds wrote in a private letter, "If we do not get some one soon who can command an army without consulting ' Stanton and Halleck' at Washington, I do not know what will become of this Army." President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

met with Reynolds in a private interview on June 2 and is believed to have asked him whether he would consider being the next commander of the Army of the Potomac. Reynolds supposedly replied that he would be willing to accept only if he were given a free hand and could be isolated from the political influences that had affected the Army commanders throughout the war. Unable to comply with his demands, Lincoln promoted the more junior George G. Meade to replace Hooker on June 28.

Gettysburg

On the morning of July 1, 1863, Reynolds was commanding the "left wing" of the Army of the Potomac, with operational control over the I, III, and XI Corps, and Brig. Gen.

On the morning of July 1, 1863, Reynolds was commanding the "left wing" of the Army of the Potomac, with operational control over the I, III, and XI Corps, and Brig. Gen. John Buford

John Buford, Jr. (March 4, 1826 – December 16, 1863) was a United States Army cavalry officer. He fought for the Union as a brigadier general during the American Civil War. Buford is best known for having played a major role in the first day ...

's cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry ...

division. Buford occupied the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

Gettysburg (; non-locally ) is a borough and the county seat of Adams County in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. The Battle of Gettysburg (1863) and President Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address are named for this town.

Gettysburg is home to th ...

, and set up light defensive lines north and west of the town. He resisted the approach of two Confederate infantry brigades on the Chambersburg Pike until the nearest Union infantry, Reynolds' I Corps, began to arrive. Reynolds rode out ahead of the 1st Division, met with Buford, and then accompanied some of his soldiers, probably from Brig. Gen. Lysander Cutler

Lysander Cutler (February 16, 1807July 30, 1866) was an American businessman, educator, politician, and Union Army General during the American Civil War.

Early years

Cutler was born in Royalston, Massachusetts, the son of a farmer. Despite object ...

's brigade, into the fighting at Herbst's Woods. Troops began arriving from Brig. Gen. Solomon Meredith

Solomon Meredith (May 29, 1810 – October 2, 1875) was a prominent Indiana farmer, politician, and lawman who became a controversial Union Army general in the American Civil War. One of the commanders of the Iron Brigade of the Army of the ...

's Iron Brigade

The Iron Brigade, also known as The Black Hats, Black Hat Brigade, Iron Brigade of the West, and originally King's Wisconsin Brigade was an infantry brigade in the Union Army of the Potomac during the American Civil War. Although it fought enti ...

, and as Reynolds was supervising the placement of the 2nd Wisconsin, he yelled at them, "Forward men forward for God's sake and drive those fellows out of those woods." At that moment he fell from his horse with a wound in the back of the upper neck, or lower head, and died almost instantly. Command passed to his senior division commander, Maj. Gen. Abner Doubleday

Abner Doubleday (June 26, 1819 – January 26, 1893) was a career United States Army officer and Union major general in the American Civil War. He fired the first shot in defense of Fort Sumter, the opening battle of the war, and had a pi ...

.

The loss of General Reynolds was keenly felt by the army. He was loved by his men and respected by his peers. There are no recorded instances of negative comments made by his contemporaries. Historian Shelby Foote

Shelby Dade Foote Jr. (November 17, 1916 – June 27, 2005) was an American writer, historian and journalist. Although he primarily viewed himself as a novelist, he is now best known for his authorship of '' The Civil War: A Narrative'', a three ...

wrote that many considered him "not only the highest ranking but also the best general in the army." His death had a more immediate effect that day, however. By ratifying Buford's defensive plan and engaging his I Corps infantry, Reynolds essentially selected the location for the Battle of Gettysburg for Meade, turning a chance meeting engagement into a massive pitched battle, committing the Army of the Potomac to fight on that ground with forces that were initially numerically inferior to the Confederates that were concentrating there. In the command confusion that followed Reynolds' death, the two Union corps that reached the field were overwhelmed and forced to retreat through the streets of Gettysburg to the high ground south of town, where they were rallied by his old friend, Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock.

Reynolds' body was immediately transported from Gettysburg to

Reynolds' body was immediately transported from Gettysburg to Taneytown, Maryland

Taneytown ( , locally also ) is a city in Carroll County, Maryland, Carroll County, Maryland, United States. The population was 6,728 at the 2010 census. Taneytown was founded in 1754. Of the city, George Washington once wrote, "Tan-nee town is but ...

, and then to his birthplace, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where he was buried on July 4, 1863. Befitting his importance to the Union and his native state, he is memorialized by three statues in Gettysburg National Military Park

The Gettysburg National Military Park protects and interprets the landscape of the 1863 Battle of Gettysburg during the American Civil War. Located in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, the park is managed by the National Park Service. The GNMP propert ...

(an equestrian statue on McPherson Ridge, one by John Quincy Adams Ward

John Quincy Adams Ward (June 29, 1830 – May 1, 1910) was an American sculptor, whose most familiar work is his larger than life-size standing Statue of George Washington (Wall Street), statue of George Washington on the steps of Federal Hall, Fe ...

in the National Cemetery, and one on the Pennsylvania Memorial), as well as one in front of the Philadelphia City Hall

Philadelphia City Hall is the seat of the municipal government of the City of Philadelphia. Built in the ornate Second Empire style, City Hall houses the chambers of the Philadelphia City Council and the offices of the Mayor of Philadelphia. It ...

.

Katherine Hewitt had agreed with Reynolds that if he were killed in the war and they could not marry, she would join a convent

A convent is a community of monks, nuns, religious brothers or, sisters or priests. Alternatively, ''convent'' means the building used by the community. The word is particularly used in the Catholic Church, Lutheran churches, and the Anglican ...

. After he was buried, she traveled to Emmitsburg, Maryland

Emmitsburg is a town in Frederick County, Maryland, United States, south of the Mason-Dixon line separating Maryland from Pennsylvania. Founded in 1785, Emmitsburg is the home of Mount St. Mary's University. The town has two Catholic pilgrima ...

, and joined the St. Joseph Central House of the Order of the Daughters of Charity.

Death controversies

Historians disagree on the details of Reynolds' death, including the specific time (either 10:15 a.m. or 10:40–10:50 a.m.), the exact location (on East McPherson Ridge, near the 2nd Wisconsin Infantry, or West McPherson Ridge, near the 19th Indiana), and the source of the bullet (a Confederate infantryman, a Confederate sharpshooter, orfriendly fire

In military terminology, friendly fire or fratricide is an attack by belligerent or neutral forces on friendly troops while attempting to attack enemy/hostile targets. Examples include misidentifying the target as hostile, cross-fire while eng ...

). One primary source was Sergeant Charles Henry Veil, his orderly and unit Color Guard, who described the events in a letter in 1864 and then contradicted some of the details in another letter 45 years later. A letter from Reynolds' sister, Jennie, stated that the wound had a downward trajectory from the neck, implying that he was shot from above, presumably a sharpshooter in a tree or barn. Historians Bruce Catton

Charles Bruce Catton (October 9, 1899 – August 28, 1978) was an American historian and journalist, known best for his books concerning the American Civil War. Known as a narrative historian, Catton specialized in popular history, featuring int ...

and Glenn Tucker make firm assertions that a sharpshooter was responsible; Stephen Sears credits volley fire from the 7th Tennessee against the 2nd Wisconsin; Edwin Coddington cites the sister's letter and finds the sharpshooter theory to be partly credible, but leans towards Sears' conclusion; Harry W. Pfanz agrees that the location was behind the 2nd Wisconsin, but makes no judgment about the source of the fire. Steve Sanders, writing in ''Gettysburg'' magazine, suggested the possibility of friendly fire based on some accounts, and concludes that it is as equally likely as enemy fire.

Legacy

There is a John F. Reynolds Middle School in the School District of Lancaster (PA) named in his honor. Reynolds plays a role inMichael Shaara

Michael Shaara (June 23, 1928 – May 5, 1988) was an American author of science fiction, sports fiction, and historical fiction. He was born to an Italian immigrant father (the family name was originally spelled Sciarra, which in Italian is pron ...

's 1974 Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize () is an award for achievements in newspaper, magazine, online journalism, literature, and musical composition within the United States. It was established in 1917 by provisions in the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made h ...

winning novel ''The Killer Angels

''The Killer Angels'' is a 1974 historical novel by Michael Shaara that was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1975. The book depicts the three days of the Battle of Gettysburg during the American Civil War, and the days leading up to it ...

'', as well as the 1993 film based on that novel, '' Gettysburg'' (in which he was played by John Rothman

John Mahr Rothman (born June 3, 1949) is an American film, television, and stage actor.

Life and career

Rothman was born in Baltimore, Maryland, the son of Elizabeth D. (née Davidson) and Donald N. Rothman, a lawyer. He is the brother of film ...

). The film portrays Reynolds as being deliberately targeted by a Confederate sharpshooter, a scene based on the Don Troiani

Don Troiani (born 1949) is an American painter whose work focuses on his native country's military heritage, mostly from the American Revolution, War of 1812 and American Civil War. His highly realistic and historically accurate oil and watercolo ...

painting of the event. Reynolds is also significant in the prequel

A prequel is a literary, dramatic or cinematic work whose story precedes that of a previous work, by focusing on events that occur before the original narrative. A prequel is a work that forms part of a backstory to the preceding work.

The term " ...

to ''The Killer Angels'', Jeffrey Shaara's novel '' Gods and Generals'', although his role was deleted from the 2003 film based on the novel. Scholar Brian Reynolds Myers

Brian Reynolds Myers (born 1963), usually cited as B. R. Myers, is an American professor of international studies at Dongseo University in Busan, South Korea, best known for his writings on North Korean propaganda. He is a contributing editor ...

is a relative of Reynolds, his middle name a reference to him.

Monuments and memorials

See also

*List of American Civil War generals (Union)

Union generals

__NOTOC__

The following lists show the names, substantive ranks, and brevet ranks (if applicable) of all general officers who served in the United States Army during the Civil War, in addition to a small selection of lower-ranke ...

*Fort Reynolds (Colorado) Fort Reynolds was a United States Army post near Avondale, Colorado during the Indian Wars and the Civil War. The site is about east of Pueblo, Colorado.

Construction began in 1867 on the 23 square mile fort, which was named for John F. Reynolds ...

* Gen. John F. Reynolds School

Notes

References

* Bearss, Edwin C. ''Fields of Honor: Pivotal Battles of the Civil War''. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society, 2006. . * Carney, Stephen A. "John Fulton Reynolds." In ''Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History'', edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. . * Coddington, Edwin B. ''The Gettysburg Campaign; a study in command''. New York: Scribner's, 1968. . * Eicher, John H., andDavid J. Eicher

David John Eicher (born August 7, 1961) is an American editor, writer, and popularizer of astronomy and space. He has been editor-in-chief of ''Astronomy'' magazine since 2002. He is author, coauthor, or editor of 23 books on science and American ...

. ''Civil War High Commands''. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. .

* Foote, Shelby. '' The Civil War: A Narrative''. Vol. 2, ''Fredericksburg to Meridian''. New York: Random House, 1958. .

* Hawthorne, Frederick W. ''Gettysburg: Stories of Men and Monuments''. Gettysburg, PA: Association of Licensed Battlefield Guides, 1988. .

* Kantor, MacKinlay (1952), ''Gettysburg'', New York: Random House. Friendly fire" theory.

* Pfanz, Harry W. ''Gettysburg – The First Day''. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001. .

* Sander, Steve. "Enduring Tales of Gettysburg: The Death of Reynolds". ''The Gettysburg Magazine''. Issue 14, January 1996.

* Sears, Stephen W. ''Gettysburg''. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003. .

* Sears, Stephen W. ''To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign''. Ticknor and Fields, 1992. .

* Tagg, Larry''The Generals of Gettysburg''

Campbell, CA: Savas Publishing, 1998. . * Trudeau, Noah Andre. ''Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage''. New York: HarperCollins, 2002. . * Tucker, Glenn. ''High Tide at Gettysburg''. Dayton, OH: Morningside House, 1983. . First published 1958 by Bobbs-Merrill Co. * Warner, Ezra J. ''Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders''. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. . * Welcher, Frank J. ''The Union Army, 1861–1865 Organization and Operations''. Vol. 1, ''The Eastern Theater''. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989. .

Reynolds family genealogy

External links

* *from the Cullum biographies

Grand Army of the Republic in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania

{{DEFAULTSORT:Reynolds, John F. 1820 births 1863 deaths People from Lancaster, Pennsylvania Union Army generals Union military personnel killed in the American Civil War People of Pennsylvania in the American Civil War American military personnel of the Mexican–American War American Civil War prisoners of war United States Military Academy alumni Commandants of the Corps of Cadets of the United States Military Academy Pennsylvania Reserves Deaths by firearm in Pennsylvania Rogue River Wars