John Crawfurd on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Crawfurd (13 August 1783 – 11 May 1868) was a Scottish physician, colonial administrator, diplomat, and author who served as the second and last Resident of Singapore.

As Resident, Crawfurd also pursued the study of the Javanese language, and cultivated personal relationships with Javanese aristocrats and literati. He was impressed by Javanese music.

As Resident, Crawfurd also pursued the study of the Javanese language, and cultivated personal relationships with Javanese aristocrats and literati. He was impressed by Javanese music.

Crawfurd was sent on diplomatic missions to Bali and the Celebes (now Sulawesi). His knowledge of the local culture supported Raffles's government in Java. Raffles, however, wanted to introduce land reform in the Cheribon residency. Crawfurd, with his experience of India and the ''

Crawfurd was sent on diplomatic missions to Bali and the Celebes (now Sulawesi). His knowledge of the local culture supported Raffles's government in Java. Raffles, however, wanted to introduce land reform in the Cheribon residency. Crawfurd, with his experience of India and the ''

In 1821, the then

In 1821, the then

Crawfurd was appointed British Resident of Singapore in March 1823. He was under orders to reduce the expenditure on the existing

Crawfurd was appointed British Resident of Singapore in March 1823. He was under orders to reduce the expenditure on the existing

Crawfurd was sent on another envoy mission to

Crawfurd was sent on another envoy mission to

A lifelong advocate of free trade policies, in ''A View of the Present State and Future Prospects of the Free Trade and Colonization of India'' (1829), Crawfurd made an extended case against the East India Company's approach, in particular in excluding British entrepreneurs, and in failing to develop Indian cotton. He had had experience in Java of the export possibilities for cotton textiles. He then gave evidence in March 1830 to a parliamentary committee, on the East India Company's monopoly of trade with China.

A lifelong advocate of free trade policies, in ''A View of the Present State and Future Prospects of the Free Trade and Colonization of India'' (1829), Crawfurd made an extended case against the East India Company's approach, in particular in excluding British entrepreneurs, and in failing to develop Indian cotton. He had had experience in Java of the export possibilities for cotton textiles. He then gave evidence in March 1830 to a parliamentary committee, on the East India Company's monopoly of trade with China.

*''Journal of an Embassy to the Court of Ava in 1827'' (1829)

*''Journal of an Embassy to the Courts of Siam and Cochin-China, exhibiting a view of the actual State of these Kingdoms'' (1830)

*''Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands and Adjacent Countries'' (1856)

*

*''Journal of an Embassy to the Court of Ava in 1827'' (1829)

*''Journal of an Embassy to the Courts of Siam and Cochin-China, exhibiting a view of the actual State of these Kingdoms'' (1830)

*''Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands and Adjacent Countries'' (1856)

*

According to Jane Rendall's concept of " Scottish orientalism", Crawfurd is a historian of the second generation. His ''History of the Indian Archipelago'' (1820), in three volumes, was his major work. Crawfurd was a critic of much of what the European nations had done in the area of Asia he covered.

''An Historical and Descriptive Account of China'' (1836) was a joint work in three volumes from the ''

According to Jane Rendall's concept of " Scottish orientalism", Crawfurd is a historian of the second generation. His ''History of the Indian Archipelago'' (1820), in three volumes, was his major work. Crawfurd was a critic of much of what the European nations had done in the area of Asia he covered.

''An Historical and Descriptive Account of China'' (1836) was a joint work in three volumes from the ''

Race and British Colonialism in South-East Asia: John Crawfurd and the politics of equality

Routledge.

Race and British Colonialism in South-East Asia: John Crawfurd and the politics of equality

Routledge.

Royal Geographical Society ObituaryObituary

from the '' Sydney Herald''

Infopedia page

;Attribution {{DEFAULTSORT:Crawfurd, John 1783 births 1868 deaths 19th-century Scottish medical doctors People from Islay Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Historians of India British East India Company civil servants Fellows of the Royal Society Fellows of the Ethnological Society of London Scottish politicians Scottish diplomats Scottish economics writers British ethnologists Scottish geographers 20th-century Scottish historians Scottish linguists Scottish orientalists Scottish colonial officials Scottish surgeons Scottish travel writers Fellows of the Linnean Society of London Fellows of the Royal Geographical Society Administrators in British Malaya Administrators in British Singapore Governors of the Straits Settlements

Early life

He was born on Islay, inArgyll

Argyll (; archaically Argyle, in modern Gaelic, ), sometimes called Argyllshire, is a historic county and registration county of western Scotland.

Argyll is of ancient origin, and corresponds to most of the part of the ancient kingdom of ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

, the son of Samuel Crawfurd, a physician, and Margaret Campbell; and was educated at the school in Bowmore

Bowmore ( gd, Bogh Mòr, 'Big Bend') is a small town on the Scottish island of Islay. It serves as administrative capital of the island, and gives its name to the noted Bowmore distillery producing Bowmore single malt scotch whisky.

History

...

. He followed his father's footsteps in the study of medicine and completed his medical course at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

in 1803, at the age of 20.

Crawfurd joined the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

, as a Company surgeon, and was posted to India's Northwestern Provinces (now Uttar Pradesh

Uttar Pradesh (; , 'Northern Province') is a state in northern India. With over 200 million inhabitants, it is the most populated state in India as well as the most populous country subdivision in the world. It was established in 1950 ...

), working in the area around Delhi

Delhi, officially the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi, is a city and a union territory of India containing New Delhi, the capital of India. Straddling the Yamuna river, primarily its western or right bank, Delhi shares borders ...

and Agra

Agra (, ) is a city on the banks of the Yamuna river in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, about south-east of the national capital New Delhi and 330 km west of the state capital Lucknow. With a population of roughly 1.6 million, Agra i ...

from 1803–1808. He saw service in the campaigns of Baron Lake.

In the East Indies

Crawfurd was sent in 1808 to Penang, where he applied himself to the study of theMalay language

Malay (; ms, Bahasa Melayu, links=no, Jawi alphabet, Jawi: , Rejang script, Rencong: ) is an Austronesian languages, Austronesian language that is an official language of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore, and that is also spo ...

and culture. In Penang, he met Stamford Raffles

Sir Thomas Stamford Bingley Raffles (5 July 1781 – 5 July 1826) was a British statesman who served as the Lieutenant-Governor of the Dutch East Indies between 1811 and 1816, and Lieutenant-Governor of Bencoolen between 1818 and 1824. He is ...

for the first time.

In 1811, Crawfurd accompanied Raffles on Lord Minto

Earl of Minto, in the County of Roxburgh, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1813 for Gilbert Elliot-Murray-Kynynmound, 1st Baron Minto. The current earl is Gilbert Timothy George Lariston Elliot-Murray-Kynynm ...

's Java Invasion, which overcame the Dutch. Raffles was appointed Lieutenant-Governor of Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's mos ...

by Minto during the 45-day operation, and Crawfurd was appointed the post of Resident Governor at the Court of Yogyakarta

Yogyakarta (; jv, ꦔꦪꦺꦴꦒꦾꦏꦂꦠ ; pey, Jogjakarta) is the capital city of Special Region of Yogyakarta in Indonesia, in the south-central part of the island of Java. As the only Indonesian royal city still ruled by a monarchy, ...

in November 1811. There he took a firm line against Sultan Hamengkubuwana II. The Sultan was encouraged by Pakubuwono IV

Pakubuwono IV (also transliterated Pakubuwana IV) (31 August 1768 – 1 October 1820) was the fourth Susuhunan (ruler of Surakarta

Surakarta ( jv, ꦯꦸꦫꦏꦂꦠ), known colloquially as Solo ( jv, ꦱꦭ; ), is a city in Central Java, ...

of Surakarta to assume he had support in resisting the British; who sided with his opponents: his son, the Crown Prince

A crown prince or hereditary prince is the heir apparent to the throne in a royal or imperial monarchy. The female form of the title is crown princess, which may refer either to an heiress apparent or, especially in earlier times, to the wi ...

, and Pangeran Natsukusuma. The Sultan's palace, the Kraton Ngayogyakarta Hadiningrat, was besieged and taken by British-led forces in June 1812.

As Resident, Crawfurd also pursued the study of the Javanese language, and cultivated personal relationships with Javanese aristocrats and literati. He was impressed by Javanese music.

As Resident, Crawfurd also pursued the study of the Javanese language, and cultivated personal relationships with Javanese aristocrats and literati. He was impressed by Javanese music.

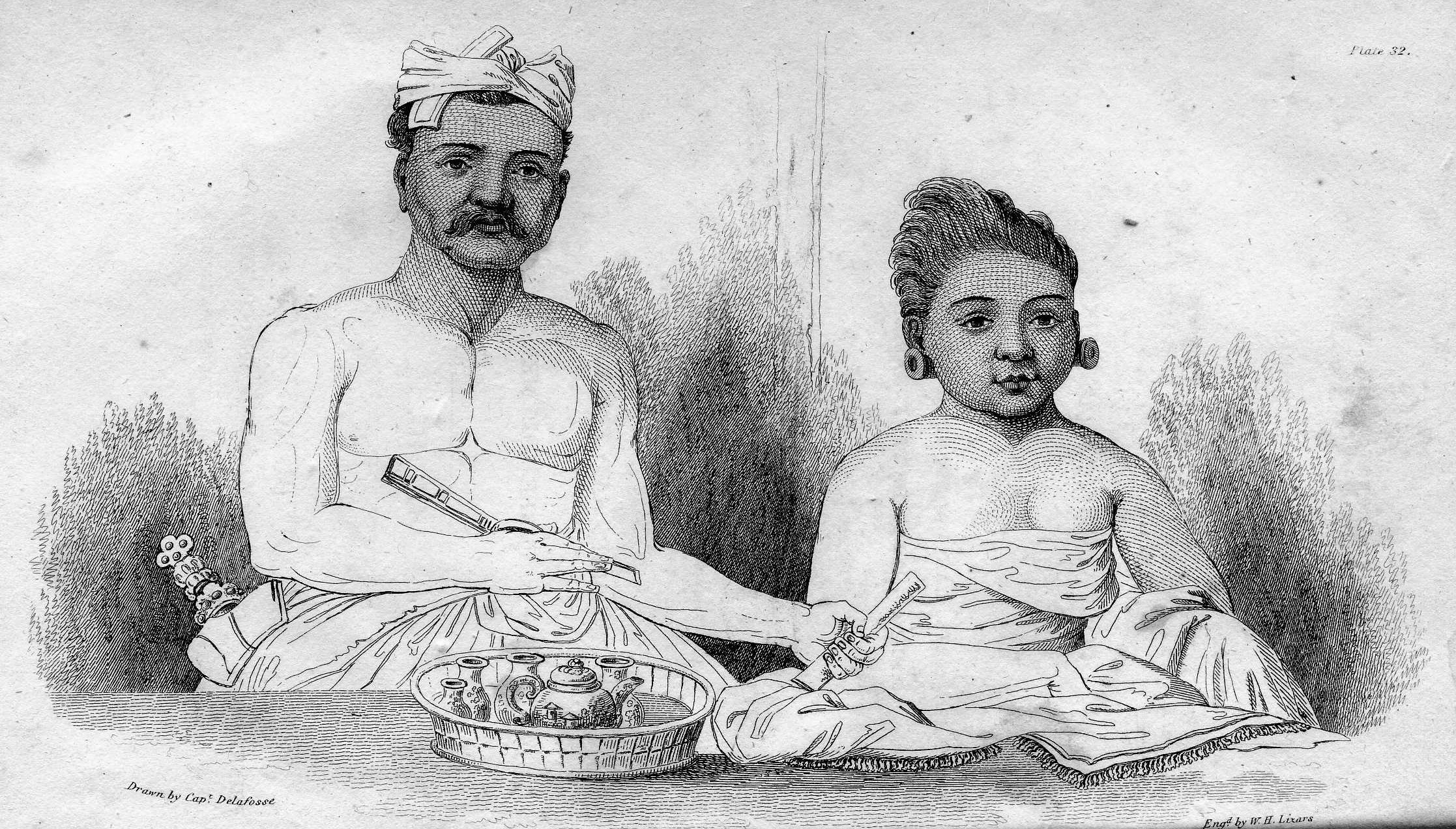

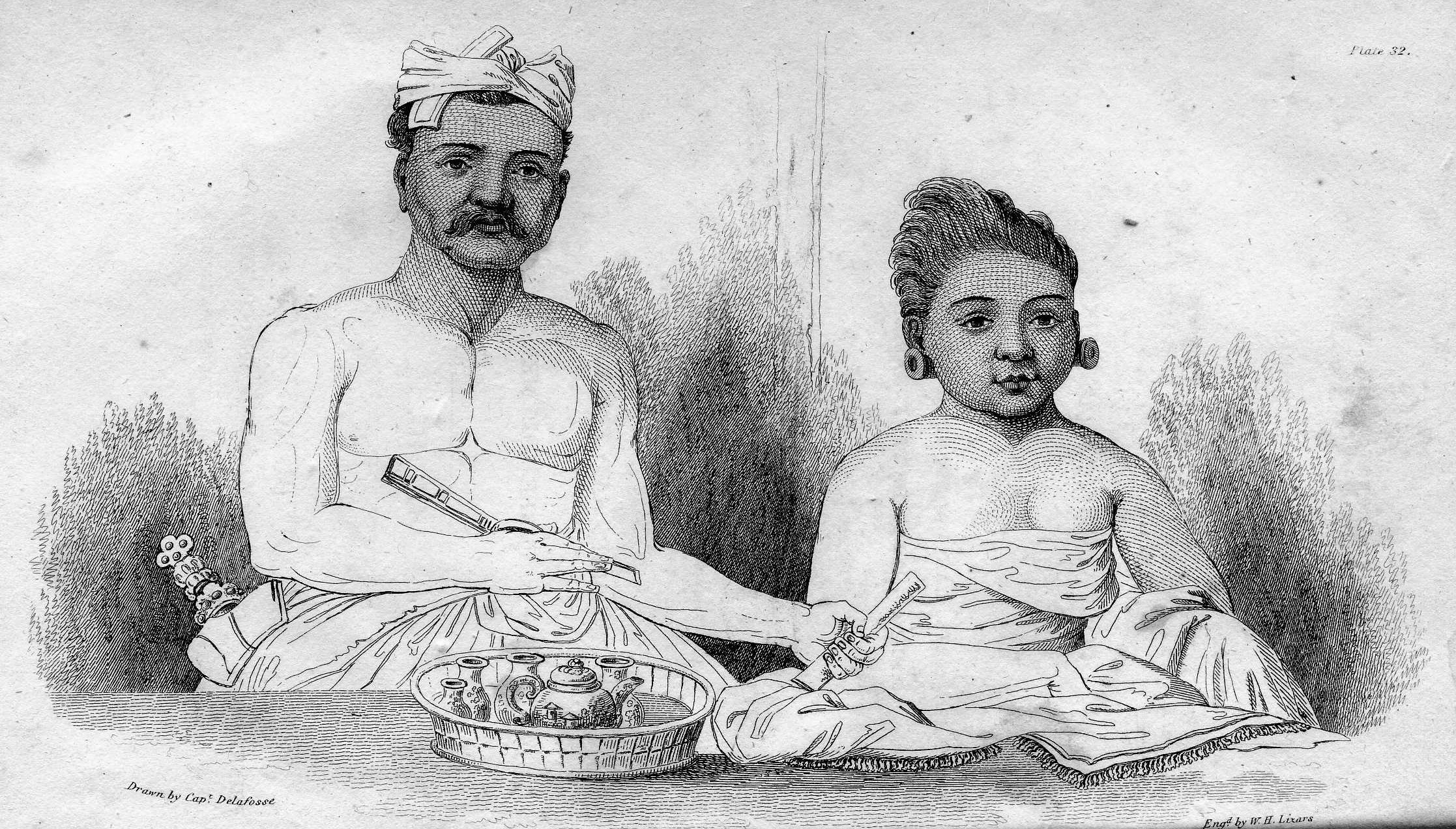

Crawfurd was sent on diplomatic missions to Bali and the Celebes (now Sulawesi). His knowledge of the local culture supported Raffles's government in Java. Raffles, however, wanted to introduce land reform in the Cheribon residency. Crawfurd, with his experience of India and the ''

Crawfurd was sent on diplomatic missions to Bali and the Celebes (now Sulawesi). His knowledge of the local culture supported Raffles's government in Java. Raffles, however, wanted to introduce land reform in the Cheribon residency. Crawfurd, with his experience of India and the ''zamindari

A zamindar ( Hindustani: Devanagari: , ; Persian: , ) in the Indian subcontinent was an autonomous or semiautonomous ruler of a province. The term itself came into use during the reign of Mughals and later the British had begun using it as ...

'', was a supporter of the "village system" of revenue collection. He opposed Raffles's attempts to introduce individual (''ryotwari

The ryotwari system was a land revenue system in British India introduced by Thomas Munro, which allowed the government to deal directly with the cultivator ('ryot') for revenue collection and gave the peasant freedom to cede or acquire new land ...

'') settlement into Java.

Diplomat

Java was returned to the Dutch in 1816, and Crawfurd went back to England that year, shortly becoming aFellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathemat ...

, and turning to writing. Within a few years he was recalled to South-East Asia, as a diplomat; his missions were of limited obvious success.

Mission to Siam, Cochin China

In 1821, the then

In 1821, the then Governor-General of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 1 ...

, Lord Hastings

Baron Hastings is a title that has been created three times. The first creation was in the Peerage of England in 1290, and is extant. The second creation was in the Peerage of England in 1299, and became extinct on the death of the first holder in ...

, sent Crawfurd to the courts of Siam

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

(now Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

) and Cochinchina

Cochinchina or Cochin-China (, ; vi, Đàng Trong (17th century - 18th century, Việt Nam (1802-1831), Đại Nam (1831-1862), Nam Kỳ (1862-1945); km, កូសាំងស៊ីន, Kosăngsin; french: Cochinchine; ) is a historical exony ...

(now Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

). Lord Hastings was especially interested in learning more about Siamese policy with regard to the northern Malay states

The monarchies of Malaysia refer to the constitutional monarchy system as practised in Malaysia. The political system of Malaysia is based on the Westminster parliamentary system in combination with features of a federation.

Nine of the state ...

, and Cochinchina's policy with regard to French efforts to establish a presence in Asia.

Crawfurd travelled with notes from Horace Hayman Wilson

Horace Hayman Wilson (26 September 1786 – 8 May 1860) was an English orientalist who was elected the first Boden Professor of Sanskrit at Oxford University.

Life

He studied medicine at St Thomas's Hospital, and went out to India in 1808 as a ...

on Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religions, Indian religion or Indian philosophy#Buddhist philosophy, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha. ...

, as it was understood at the time.

Captain Dangerfield of the Indian army

The Indian Army is the land-based branch and the largest component of the Indian Armed Forces. The President of India is the Supreme Commander of the Indian Army, and its professional head is the Chief of Army Staff (COAS), who is a four- ...

, a skilful astronomer, surveyor and geologist, served as assistant; Lieutenant Rutherford commanded thirty Sepoys; noted naturalist George Finlayson

George Finlayson (1790–1823) was a Scottish naturalist and traveller. He was called one of the best naturalists of his day, and he was noted for his pioneering studies of the plants, animals, and people of southern Thailand and the Malay penin ...

served as medical officer

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

. Mrs. Crawfurd accompanied the Mission.

21 November 1821, the mission embarked on the '' John Adam'' for the complicated and difficult navigation of the Hoogly river, taking seven days to sail the 140 miles (225 km.) from Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, the official name until 2001) is the Capital city, capital of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal, on the eastern ba ...

to open water. Crawfurd writes that, with the assistance of a steam-boat, ships might be towed down in two days without difficulty; then adds in a footnote: "The first steam-vessel used in India, was built about three years after this passage was written...."

The ''John Adam'' proceeded on what would be the first official visit to Siam since the resurgence of Siam following the 1767 Fall of Ayutthaya. Crawfurd soon found the court of King Rama II

Phra Phutthaloetla Naphalai ( th, พระพุทธเลิศหล้านภาลัย, 24 February 1767 – 21 July 1824), personal name Chim ( th, ฉิม), also styled as Rama II, was the second monarch of Siam under the Chakri ...

still embroiled in the aftermath of the Burmese–Siamese War of 1809–1812. On 8 December 1821, near Papra Strait (modern Pak Prah Strait north of Thalang District) Crawfurd finds fishermen "in a state of perpetual distrust and insecurity" due to territorial disputes between hostile Burmans and Siamese. 11 December, after entering the Straits of Malacca and arrival at Penang Island

Penang Island ( ms, Pulau Pinang; zh, 檳榔嶼; ta, பினாங்கு தீவு) is part of the state of Penang, on the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia. It was named Prince of Wales Island when it was occupied by the British Ea ...

, he finds the settlements of Penang and Queda (modern Kedah Sultanate, founded in 1136, but then a tributary state

A tributary state is a term for a pre-modern state in a particular type of subordinate relationship to a more powerful state which involved the sending of a regular token of submission, or tribute, to the superior power (the suzerain). This to ...

of Siam) in a state of alarm. Sultan Ahmad Tajuddin Halim Shah II

Paduka Sri Sultan Ahmad Tajuddin Halim Shah II ibni al-Marhum Sultan Abdullah Mukarram Shah (died 3 January 1845) was the 22nd Sultan of Kedah. His reign was from 1803 to 1821 and 1842 to 1845.

He was appointed as Heir Apparent (''Uparaja'') by t ...

, the Rajah

''Raja'' (; from , IAST ') is a royal title used for South Asian monarchs. The title is equivalent to king or princely ruler in South Asia and Southeast Asia.

The title has a long history in South Asia and Southeast Asia, being attested fr ...

of Quedah had fled the Rajah of Ligor (modern Nakhon Si Thammarat

Nakhon Si Thammarat Municipality ( th, เทศบาลนครนครศรีธรรมราช, ; from Pali ''Nagara Sri Dhammaraja'') is a municipality (''thesaban nakhon'') in Southern Thailand, capital of Nakhon Si Thammarat pro ...

) to claim right of asylum

The right of asylum (sometimes called right of political asylum; ) is an ancient juridical concept, under which people persecuted by their own rulers might be protected by another sovereign authority, like a second country or another ent ...

at Prince of Wales's Island (modern Penang.) British claim to the island was based upon payment of a quit-rent

Quit rent, quit-rent, or quitrent is a tax or land tax imposed on occupants of freehold or leased land in lieu of services to a higher landowning authority, usually a government or its assigns.

Under feudal law, the payment of quit rent (Latin ...

accordant with European feudal law, which Crawfurd feared the Siamese would challenge.

Crawfurd's journal entry for 1 April 1822, notes that the Siamese, for their part, were especially interested in the acquisition of arms. Pointedly questioned in this regard in an urgent private meeting with the Prah-klang ( Prayurawongse), the reply was, "that if the Siamese were at peace with the friends and neighbours of the British nation, they would certainly be permitted to purchase fire-arms and ammunition at our ports, but not otherwise." On 19 May, a Chief of Lao ( Chao Anu, a king in what is now Laos and soon-to-be rebel) met with Crawfurd, a first diplomatic contact for the UK. This visit was despite the isolation into which the mission had fallen. A Vietnamese embassy had arrived not long before, and tensions were high. Since Crawford's brief opposed the interests of court figures including the Raja of Ligor

Nakhon Si Thammarat Municipality ( th, เทศบาลนครนครศรีธรรมราช, ; from Pali ''Nagara Sri Dhammaraja'') is a municipality (''thesaban nakhon'') in Southern Thailand, capital of Nakhon Si Thammarat prov ...

and Nangklao, there was little prospect of success. By October relations were at a low ebb. Crawfurd moved on to Saigon, but Minh Mạng refused to see him.

Resident of Singapore

Crawfurd was appointed British Resident of Singapore in March 1823. He was under orders to reduce the expenditure on the existing

Crawfurd was appointed British Resident of Singapore in March 1823. He was under orders to reduce the expenditure on the existing factory

A factory, manufacturing plant or a production plant is an industrial facility, often a complex consisting of several buildings filled with machinery, where workers manufacture items or operate machines which process each item into another. ...

there, but instead responded to local commercial representations, and spent money on reclamation work on the river. He also concluded the final agreement between the East India Company, and Sultan Hussein Shah of Johor

Sultan Hussein Mua'zzam Shah ibni Mahmud Shah Alam (1776 – 5 September 1835) was the 18th ruler of Johor-Riau. He signed two treaties with Britain which culminated in the founding of modern Singapore; during which he was nominally given re ...

with the Temenggong

Temenggong or Tumenggung ( Jawi: تمڠݢوڠ; ''Temenggung'', Hanacaraka: ꦠꦸꦩꦼꦁꦒꦸꦁ; ''Tumenggung'') is an old Malay and Javanese title of nobility, usually given to the chief of public security.

Responsibilities

The Tem ...

, on the status of Singapore on 2 August 1824. It was the culmination of negotiations started by Raffles in 1819, and the agreement is now sometimes called the Crawfurd Treaty. He also had input into the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 dealing with spheres of influence in the East Indies.

Crawfurd was on familiar terms with Munshi Abdullah

Abdullah bin Abdul al Kadir (1796–1854) ( ar, عبد الله بن عبد القادر ') also known as Munshi Abdullah, was a Malayan writer of mixed ancestry. He was a famous Malacca-born munshi of Singapore and died in Jeddah, a part of t ...

. He edited and contributed to the '' Singapore Chronicle'' of Francis James Bernard, the first local newspaper that initially appeared dated 1 January 1824. Crawford Street and Crawford Bridge in Singapore are named after him.

Burma mission

Crawfurd was sent on another envoy mission to

Crawfurd was sent on another envoy mission to Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

in 1826, by Hastings's successor Lord Amherst, in the aftermath of the First Anglo-Burmese War

The First Anglo-Burmese War ( my, ပထမ အင်္ဂလိပ်-မြန်မာ စစ်; ; 5 March 1824 – 24 February 1826), also known as the First Burma War, was the first of three wars fought between the British and Burmes ...

. It was to be his last political service for the Company. The party included Adoniram Judson as interpreter and Nathaniel Wallich as botanist. Crawfurd's journey to Ava up the River Irrawaddy was by paddle steamer

A paddle steamer is a steamship or steamboat powered by a steam engine that drives paddle wheels to propel the craft through the water. In antiquity, paddle wheelers followed the development of poles, oars and sails, where the first uses we ...

, the ''Diana'': it had been hired by the East India Company for the war, where it had seen action and travelled 400 miles up the Irrawaddy. There were five local boats, and soldiers making up a party of over 50.

Crawfurd at the court found Bagyidaw

Bagyidaw ( my, ဘကြီးတော်, ; also known as Sagaing Min, ; 23 July 1784 – 15 October 1846) was the seventh king of the Konbaung dynasty of Burma from 1819 until his abdication in 1837. Prince of Sagaing, as he was commonly know ...

temporising despite a weak position with the British forces in Arakan

Arakan ( or ) is a historic coastal region in Southeast Asia. Its borders faced the Bay of Bengal to its west, the Indian subcontinent to its north and Burma proper to its east. The Arakan Mountains isolated the region and made it accessi ...

and Tenasserim. The king conceded only a trade agreement, in return for a delay in indemnity payments; and sent his own mission to Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, the official name until 2001) is the Capital city, capital of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal, on the eastern ba ...

.

The expedition fortuitously was delayed on the return journey for repairs. Crawfurd collected significant fossils, north of Magwe on the left bank of the river, in seven chests. Back in London, William Clift

William Clift FRS (14 February 1775 – 20 June 1849) was a British illustrator and conservator.

Early life

Clift was born in Burcombe near Bodmin in Cornwall. He was the youngest of seven children and grew up in poverty following his fat ...

identified a new species of mastodon (more accurately Stegolophodon

''Stegolophodon'' is an extinct genus of stegodontid proboscideans, with two tusks and a trunk. It lived during the Miocene and Pliocene epochs, and may have evolved into ''Stegodon

''Stegodon'' ("roofed tooth" from the Ancient Greek words ...

) from them; Hugh Falconer

Hugh Falconer MD FRS (29 February 1808 – 31 January 1865) was a Scottish geologist, botanist, palaeontologist, and paleoanthropologist. He studied the flora, fauna, and geology of India, Assam,Burma,and most of the Mediterranean islands a ...

also worked on the collection. The finds, of fossil bones and wood, were discussed further in a paper by William Buckland

William Buckland DD, FRS (12 March 1784 – 14 August 1856) was an English theologian who became Dean of Westminster. He was also a geologist and palaeontologist.

Buckland wrote the first full account of a fossil dinosaur, which he named ' ...

, giving details; and they brought Crawfurd the friendship of Roderick Murchison, Foreign Secretary of the Geological Society. There were also collected 18,000 botanical specimens, many of which went to the Calcutta Botanic Garden

The Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose Indian Botanic Garden, previously known as Indian Botanic Garden and the Calcutta Botanic Garden, is situated in Shibpur, Howrah near Kolkata. They are commonly known as the Calcutta Botanical Garden and prev ...

.

Later life

In the United Kingdom, Crawfurd spent around 40 years in varied activities. He wrote as an orientalist, geographer and ethnologist. He tried parliamentary politics, without success; he agitated forfree trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

; and he was a publicist for and against colonisation schemes, in line with his views. He also represented the interests of British traders based in Singapore and Calcutta.

Radical parliamentary candidate

Crawfurd made several unsuccessful attempts to enter the British Parliament in the 1830s. His campaign literature featureduniversal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political stan ...

and the secret ballot, free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

and opposition to monopolies

A monopoly (from Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situation where a speci ...

, public education and reduction of military spending, and opposition to regressive taxation and the taxation of Dissenters

A dissenter (from the Latin ''dissentire'', "to disagree") is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc.

Usage in Christianity

Dissent from the Anglican church

In the social and religious history of England and Wales, an ...

for a state church, with nationalisation of Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

properties. He joined the Parliamentary Candidate Society, founded by Thomas Erskine Perry (his brother-in-law), to promote "fit and proper" Members of Parliament. He also joined the Radical Club, a breakaway from the National Political Union founded in 1833 by William Wallis.

Crawfurd unsuccessfully contested, as an advanced radical, Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

in 1832, Paisley in 1834, Stirling Burghs in 1835, and Preston in 1837.Douglas, Robert Kennaway (1888) "Crawfurd, John (1783–1868), orientalist" in '' Dictionary of National Biography''. At Glasgow he polled fourth (there were two MPs for the borough), with Sir Daniel Sandford third. In March 1834 it was Sandford who was elected at Paisley. ''Alexander's East India and Colonial Magazine'' struck a note of regret after his defeat at Stirling Burghs.

On 31 January 1834 Crawfurd supported Thomas Perronet Thompson

Thomas Perronet Thompson (1783–1869) was a British Parliamentarian, a governor of Sierra Leone and a radical reformer. He became prominent in 1830s and 1840s as a leading activist in the Anti-Corn Law League. He specialized in the grass-root ...

in a meeting agitating against the Corn Laws

The Corn Laws were tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and corn enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846. The word ''corn'' in British English denotes all cereal grains, including wheat, oats and barley. They wer ...

. Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, Dum ...

alluded, in notes on one of Jane Welsh Carlyle

Jane Baillie Carlyle ( Welsh; 14 July 1801 – 21 April 1866) was a Scottish writer and the wife of Thomas Carlyle.

She did not publish any work in her lifetime, but she was widely seen as an extraordinary letter writer. Virginia Woolf ca ...

's letters, to Crawfurd speaking at a radical meeting at the London Tavern

The City of London Tavern or London Tavern was a notable meeting place in London during the 18th and 19th centuries. A place of business where people gathered to drink alcoholic beverages and be served food, the tavern was situated in Bishopsgate ...

set up by Charles Buller

Charles Buller (6 August 1806 – 29 November 1848) was a British barrister, politician and reformer.

Background and education

Born in Calcutta, British India, Buller was the son of Charles Buller (1774–1848), a member of a well-known Cor ...

on 21 November 1834; in which he showed much more originality than John Arthur Roebuck

John Arthur Roebuck (28 December 1802 – 30 November 1879), British politician, was born at Madras, in India. He was raised in Canada, and moved to England in 1824, and became intimate with the leading radical and utilitarian reformers. He was ...

, but lost his thread.

In Preston in the 1837 general election Crawfurd had the Liberal nomination in a three-cornered fight for two seats, as Peter Hesketh-Fleetwood

Sir Peter Hesketh-Fleetwood, 1st Baronet, (9 May 1801 – 12 April 1866) was an English landowner, developer and Member of Parliament, who founded the town of Fleetwood, in Lancashire, England. Born Peter Hesketh, he changed his name by ...

was regarded as a waverer by the Conservatives who ran Robert Townley Parker against him; but he polled third. He also supported John Temple Leader's candidacy at Westminster against Sir Francis Burdett

Sir Francis Burdett, 5th Baronet (25 January 1770 – 23 January 1844) was a British politician and Member of Parliament who gained notoriety as a proponent (in advance of the Chartists) of universal male suffrage, equal electoral districts, vo ...

, being deputy chairman on his election committee (with Thomas Prout, chairman Sir Ronald Craufurd Ferguson). Crawfurd spoke with George Grote

George Grote (; 17 November 1794 – 18 June 1871) was an English political radical and classical historian. He is now best known for his major work, the voluminous ''History of Greece''.

Early life

George Grote was born at Clay Hill near B ...

at a meeting for Leader at the Belgrave Hotel.

Free trader

A lifelong advocate of free trade policies, in ''A View of the Present State and Future Prospects of the Free Trade and Colonization of India'' (1829), Crawfurd made an extended case against the East India Company's approach, in particular in excluding British entrepreneurs, and in failing to develop Indian cotton. He had had experience in Java of the export possibilities for cotton textiles. He then gave evidence in March 1830 to a parliamentary committee, on the East India Company's monopoly of trade with China.

A lifelong advocate of free trade policies, in ''A View of the Present State and Future Prospects of the Free Trade and Colonization of India'' (1829), Crawfurd made an extended case against the East India Company's approach, in particular in excluding British entrepreneurs, and in failing to develop Indian cotton. He had had experience in Java of the export possibilities for cotton textiles. He then gave evidence in March 1830 to a parliamentary committee, on the East India Company's monopoly of trade with China. Robert Montgomery Martin

Robert Montgomery Martin (c. 1801 – 6 September 1868), commonly referred to as "Montgomery Martin", was an Anglo-Irish author and civil servant. He served as Colonial Treasurer of Hong Kong from 1844 to 1845. He was a founding member of the St ...

criticised Crawfurd, and the evidence of Robert Rickards, an ex-employee of the Company, for exaggerating the financial burden of the monopoly on tea. Crawfurd put out a pamphlet, ''Chinese Monopoly Examined''. Ross Donnelly Mangles defended the East India Company in 1830, in an answer addressed to Rickards and Crawfurd. When the Company's charter came up for renewal in 1833, the China trade monopoly was broken. Crawfurd's part as parliamentary agent for interests in Calcutta had been paid (at £1500 per year); his publicity work had included facts for an '' Edinburgh Review'' article written by another author.

Colonisation of Australia

In reviewingEdward Gibbon Wakefield

Edward Gibbon Wakefield (20 March 179616 May 1862) is considered a key figure in the establishment of the colonies of South Australia and New Zealand (where he later served as a member of parliament). He also had significant interests in Brit ...

's ''New British Province of South Australia'', and subsequent writing in the ''Westminster Review

The ''Westminster Review'' was a quarterly British publication. Established in 1823 as the official organ of the Philosophical Radicals, it was published from 1824 to 1914. James Mill was one of the driving forces behind the liberal journal unt ...

'', Crawfurd gave an opinion against systematic colonisation

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

. He considered that abundant land and individual enterprise were the necessary elements. Robert Torrens, who floated the South Australian Land Company, replied to the ''Westminster Review'' line in ''Colonization of South Australia'' (1835). Part I of the book is a ''Letter'' to Crawfurd.

In 1843 Crawfurd gave evidence to the Colonial Office

The Colonial Office was a government department of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, first created to deal with the colonial affairs of British North America but required also to oversee the increasing number of c ...

on Port Essington, on the north coast of Australia, to the effect that its climate made it unsuitable for settlement. He returned to the topic in a debate in 1858 on settlements on the Victoria River, as had been suggested by Sir George Everest

Colonel Sir George Everest CB FRS FRAS FRGS (; 4 July 1790 – 1 December 1866) was a British surveyor and geographer who served as Surveyor General of India from 1830 to 1843.

After receiving a military education in Marlow, Everest joined t ...

. He generally opposed Sir Roderick Murchison's promotion of European colonisation of Australia, as far as it applied to the north coast.

Lobbyist for South and South-East Asia

When the Stamp Act 1827 was passed, meaning that all public documents in India would have to pay a stamp tax (including newspapers as well as legal documents), Crawfurd was hired as London agent for a group of British merchants in Calcutta opposing the legislation. Crawfurd involvedJoseph Hume

Joseph Hume FRS (22 January 1777 – 20 February 1855) was a Scottish surgeon and Radical MP.Ronald K. Huch, Paul R. Ziegler 1985 Joseph Hume, the People's M.P.: DIANE Publishing.

Early life

He was born the son of a shipmaster James Hume ...

, and he obtained newspaper coverage for his cause, including in '' The Examiner'' where the precedents from America were cited. He also wrote pamphlets himself, in which he advocated an end to the East India Company monopoly, and European colonisation. These moves occurred in 1828–9; in 1830 Crawfurd approached William Huskisson

William Huskisson (11 March 177015 September 1830) was a British statesman, financier, and Member of Parliament for several constituencies, including Liverpool.

He is commonly known as the world's first widely reported railway passenger casu ...

directly. His lobbying continued with the free trade issues mentioned above. ''Inquiry into the System of Taxation in India, Letters on the Interior of India, an attack on the newspaper stamp-tax and the duty on paper entitled Taxes on Knowledge'' (1836) is a related work.

In 1855 Crawfurd went with a delegation to the Board of Control of the East India Company, with representations on behalf of the Straits dollar as an independent currency. Crawfurd lobbied in both Houses of Parliament, with George Keppel, 6th Earl of Albemarle

General George Thomas Keppel, 6th Earl of Albemarle, (13 June 179921 February 1891), styled The Honourable from birth until 1851, was a British soldier, Liberal politician and writer.

Background and education

Born in Marylebone, he was the thir ...

acting to bring a petition to the Lords, and William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

putting the case in the Commons. Among the arguments put was that the dollar was a decimal currency

Decimalisation or decimalization (see spelling differences) is the conversion of a system of currency or of weights and measures to units related by powers of 10.

Most countries have decimalised their currencies, converting them from non-decimal ...

, while the rupee used by traders, and legal tender

Legal tender is a form of money that courts of law are required to recognize as satisfactory payment for any monetary debt. Each jurisdiction determines what is legal tender, but essentially it is anything which when offered ("tendered") in ...

in East India Company territories since it was coined in 1835, was not. In 1856 a Bill to change the status quo on coins minted and issued from India was defeated.

In 1868 Crawfurd with James Guthrie and William Paterson formed the Straits Settlements Association, to protect the colony's interests. Crawfurd was its first President.

Last years

He was elected President of the Ethnological Society in 1861. He died at his home inElvaston Place

Elvaston Place is a street in South Kensington, London.

Elvaston Place runs west to east from Gloucester Road to Queen's Gate.

The Embassy of Gabon, London is at number 27. The High Commission of Mauritius, London is at number 32/33. The Embassy ...

, South Kensington

South Kensington, nicknamed Little Paris, is a district just west of Central London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Historically it settled on part of the scattered Middlesex village of Brompton. Its name was supplanted with ...

, London on 11 May 1868 at the age of 85.

Works

Crawfurd wrote prolifically. His views have been seen as inconsistent: a recent author wrote that " ..Crawfurd seemed to embody a complex mixture of elements of coexisting but ultimately contradictory value systems". Ellingson, p. 310. A comment about "hasty general opinions from a few instances", by George Bennett on the topic of Papuan people, has been taken to be aimed at Crawfurd. His 1822 work ''"Malay of Champa"'' contains a vocabulary of theCham language

Cham (Cham: ꨌꩌ) is a Malayo-Polynesian languages, Malayo-Polynesian language of the Austronesian languages, Austronesian family, spoken by the Cham people, Chams of Southeast Asia. It is spoken primarily in the territory of the former Kingdo ...

.

Diplomat and traveller

In retirement after the Burmese mission, Crawfurd wrote books and papers on Eastern subjects. His envoy experiences from missions were written up in ''Journals'' in 1828 and 1829. This documentation was reprinted nearly 140 years later by Oxford University Press. *''Journal of an Embassy to the Court of Ava in 1827'' (1829)

*''Journal of an Embassy to the Courts of Siam and Cochin-China, exhibiting a view of the actual State of these Kingdoms'' (1830)

*''Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands and Adjacent Countries'' (1856)

*

*''Journal of an Embassy to the Court of Ava in 1827'' (1829)

*''Journal of an Embassy to the Courts of Siam and Cochin-China, exhibiting a view of the actual State of these Kingdoms'' (1830)

*''Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands and Adjacent Countries'' (1856)

*

Historian

According to Jane Rendall's concept of " Scottish orientalism", Crawfurd is a historian of the second generation. His ''History of the Indian Archipelago'' (1820), in three volumes, was his major work. Crawfurd was a critic of much of what the European nations had done in the area of Asia he covered.

''An Historical and Descriptive Account of China'' (1836) was a joint work in three volumes from the ''

According to Jane Rendall's concept of " Scottish orientalism", Crawfurd is a historian of the second generation. His ''History of the Indian Archipelago'' (1820), in three volumes, was his major work. Crawfurd was a critic of much of what the European nations had done in the area of Asia he covered.

''An Historical and Descriptive Account of China'' (1836) was a joint work in three volumes from the ''Edinburgh Cabinet Library

The ''Edinburgh Cabinet Library'' was a series of 38 books, mostly geographical, published from 1830 to 1844, and edited by Dionysius Lardner. The original price was 5 shillings for a volume; a later reissue of 30 of the volumes was at half that ...

'', with Hugh Murray, Peter Gordon, Thomas Lynn, William Wallace

Sir William Wallace ( gd, Uilleam Uallas, ; Norman French: ; 23 August 1305) was a Scottish knight who became one of the main leaders during the First War of Scottish Independence.

Along with Andrew Moray, Wallace defeated an English army ...

, and Gilbert Thomas Burnett.

Orientalist

*''Grammar and Dictionary of the Malay Language'' (1852) Crawfurd andColin Mackenzie

Colonel Colin Mackenzie CB (1754–8 May 1821) was Scottish army officer in the British East India Company who later became the first Surveyor General of India. He was a collector of antiquities and an orientalist. He surveyed southern India, ...

collected manuscripts from the capture of Yogyakarta, and some of these are now in the British Library

The British Library is the national library of the United Kingdom and is one of the largest libraries in the world. It is estimated to contain between 170 and 200 million items from many countries. As a legal deposit library, the British ...

.

Crawfurd claimed Cham

Cham or CHAM may refer to:

Ethnicities and languages

*Chams, people in Vietnam and Cambodia

**Cham language, the language of the Cham people

***Cham script

*** Cham (Unicode block), a block of Unicode characters of the Cham script

*Cham Albania ...

for the Austronesian languages. His suggestion met no favour at the time, but scholars from around 1950 onwards came to agree.

Economist

Crawfurd held strong views on what he saw as the backwardness of the economy of India of his time. He attributed it to the weakness of Indian financial institutions, compared to Europe. His opinions were in an anonymous pamphlet ''A Sketch of the Commercial Resources and Monetary and Mercantile System of British India'' (1837) now attributed to him. LikeRobert Montgomery Martin

Robert Montgomery Martin (c. 1801 – 6 September 1868), commonly referred to as "Montgomery Martin", was an Anglo-Irish author and civil servant. He served as Colonial Treasurer of Hong Kong from 1844 to 1845. He was a founding member of the St ...

, he saw India primarily as a source of raw materials, and advocated investment based on that direction. A harsh critic of the existing Calcutta agencies, he noted the absence of bill broking in India and suggested that an exchange bank should be set up.

His view that an economy dominated by agriculture was inevitably an absolute government Absolute may refer to:

Companies

* Absolute Entertainment, a video game publisher

* Absolute Radio, (formerly Virgin Radio), independent national radio station in the UK

* Absolute Software Corporation, specializes in security and data risk manage ...

was cited by Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake ...

, in his '' On the Constitution of the Church and State''.

Ethnologist

While Crawfurd produced work that was ethnological in nature over a period of half a century, the term "ethnology

Ethnology (from the grc-gre, ἔθνος, meaning 'nation') is an academic field that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural, social, or sociocultural anthropology). ...

" had not even been coined when he began to write. Attention has been drawn to his latest work, from the 1860s, which was copious, much criticised at the time, and which has also been scrutinised in the 21st century, as detailed below.

Polygenist

Crawfurd heldpolygenist

Polygenism is a theory of human origins which posits the view that the human races are of different origins (''polygenesis''). This view is opposite to the idea of monogenism, which posits a single origin of humanity. Modern scientific views no ...

views, based on multiple origins of human groups; and these earned him, according to Sir John Bowring, the nickname "the inventor of forty Adams". In ''The Descent of Man

''The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex'' is a book by English naturalist Charles Darwin, first published in 1871, which applies evolutionary theory to human evolution, and details his theory of sexual selection, a form of biol ...

'' by Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

, Crawfurd is cited as believing in 60 races. He expressed these views to the Ethnological Society of London (ESL), a traditional stronghold of monogenism

Monogenism or sometimes monogenesis is the theory of human origins which posits a common descent for all human races. The negation of monogenism is polygenism. This issue was hotly debated in the Western world in the nineteenth century, as the ...

(belief in a unified origin of humankind) where he had come in 1861 to hold office as President.

Crawfurd believed in different races as separate creations by God in specific regional zones, with separate origins for languages, and possibly as different species. With Robert Gordon Latham

Robert Gordon Latham FRS (24 March 1812 – 9 March 1888) was an English ethnologist and philologist.

Early life

The eldest son of Thomas Latham, vicar of Billingborough, Lincolnshire, he was born there on 24 March 1812. He entered Eton College ...

of the ESL, he also opposed strongly the ideas of Max Müller

Friedrich Max Müller (; 6 December 1823 – 28 October 1900) was a German-born philologist and Orientalist, who lived and studied in Britain for most of his life. He was one of the founders of the western academic disciplines of Indian ...

on an original Aryan race

The Aryan race is an obsolete historical race concept that emerged in the late-19th century to describe people of Proto-Indo-European heritage as a racial grouping. The terminology derives from the historical usage of Aryan, used by modern I ...

.

Papers of the 1860s

Crawfurd wrote in 1861 in the ''Transactions'' of the ESL a paper ''On the Conditions Which Favour, Retard, and Obstruct the Early Civilization of Man'', in which he argued for deficiencies in the science and technology of Asia. In ''On the Numerals as Evidence of the Progress of Civilization'' (1863) he argued that the social condition of a people correlates with the numeral words of their language. Crawfurd useddomestication

Domestication is a sustained multi-generational relationship in which humans assume a significant degree of control over the reproduction and care of another group of organisms to secure a more predictable supply of resources from that group. ...

frequently as a metaphor. His racist views on black people were laughed at, during the British Association

The British Science Association (BSA) is a charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BA). The current Chie ...

meeting at Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1. ...

in 1865.

A paper by Crawfurd, ''On the Physical and Mental Characteristics of European and Asian Races of Man'', given 13 February 1866, argued for the superiority of Europeans. It particularly laid emphasis on European military dominance as evidence. Its thesis was directly contradicted at a meeting of the Society some weeks later, by Dadabhai Naoroji.

Analyses of Crawfurd's Racial Views

Recent analyses have sought to clarify Crawfurd's agenda in his writings on race and, at this time, when he had become prominent in a young and still fluid field and discipline. Ellingson demonstrates Crawfurd's role in promoting the idea of the noble savage in service of racial ideology. Trosper has taken Ellingson's analysis a step further, attributing to Crawfurd a conscious "spin" put on the idea of primitive culture, a rhetorically sophisticated use of a "straw man

A straw man (sometimes written as strawman) is a form of argument and an informal fallacy of having the impression of refuting an argument, whereas the real subject of the argument was not addressed or refuted, but instead replaced with a false o ...

" fallacy, achieved by bringing in, irrelevantly but for the sake of incongruity, the figure of Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

.

Crawfurd dedicated considerable effort to a critique of Darwin's theories of human evolution

Human evolution is the evolutionary process within the history of primates that led to the emergence of '' Homo sapiens'' as a distinct species of the hominid family, which includes the great apes. This process involved the gradual development o ...

; as a proponent of polygenism

Polygenism is a theory of human origins which posits the view that the human races are of different origins (''polygenesis''). This view is opposite to the idea of monogenism, which posits a single origin of humanity. Modern scientific views no ...

, who believed that human races did not share common ancestors, Crawfurd was an early and prominent critic of Darwin's ideas. Ellingson, p. 318. Right at the end of his life, in 1868, Crawfurd was using a " missing link" argument against Sir John Lubbock, in what Ellingson describes as a misrepresentation of a Darwinist viewpoint based on the idea that a precursor of humans must still be extant.

Ellingson points to a 1781 work of William Falconer, ''On the Influence of Climate'', with an attack on Rousseau, as a possible source of Crawfurd's thinking; while also pointing out some differences. Ellingson also places Crawfurd in a British group among those of his period whose anthropological views not only turned on race

Race, RACE or "The Race" may refer to:

* Race (biology), an informal taxonomic classification within a species, generally within a sub-species

* Race (human categorization), classification of humans into groups based on physical traits, and/or s ...

, but who also drew conclusions of superiority from those views, others being Luke Burke, James Hunt

James Simon Wallis Hunt (29 August 1947 – 15 June 1993) ''Autocourse Grand Prix Archive'', 14 October 2007. Retrieved 4 November 2007. was a British racing driver who won the Formula One World Championship in . After retiring from racing in ...

, Robert Knox

Robert Knox (4 September 1791 – 20 December 1862) was a Scottish anatomist and ethnologist best known for his involvement in the Burke and Hare murders. Born in Edinburgh, Scotland, Knox eventually partnered with anatomist and former teach ...

, and Kenneth R. H. Mackenzie.

Crawfurd's attitudes were not, however, based on human skin colour

Human skin color ranges from the darkest brown to the lightest hues. Differences in skin color among individuals is caused by variation in pigmentation, which is the result of genetics (inherited from one's biological parents and or individ ...

; and he was an opponent of slavery, having written an article "Sugar without Slavery" with Thomas Perronet Thompson in 1833 in the ''Westminster Review''. In dismissing Crawfurd's notes and suggestions on his work as "quite unimportant", Charles Darwin identified Crawfurd's racial views as "Pallasian", i.e. the analogue for humankind of the theories of Peter Simon Pallas

Peter Simon Pallas FRS FRSE (22 September 1741 – 8 September 1811) was a Prussian zoologist and botanist who worked in Russia between 1767 and 1810.

Life and work

Peter Simon Pallas was born in Berlin, the son of Professor of Surgery ...

.

The predominant approach in the ESL went back to James Cowles Prichard

James Cowles Prichard, FRS (11 February 1786 – 23 December 1848) was a British physician and ethnologist with broad interests in physical anthropology and psychiatry. His influential ''Researches into the Physical History of Mankind'' touched ...

. In the view of Thomas Trautmann, in Crawfurd's attack on the Aryan theory there is a final rejection of the "languages and nations" approach, which was Prichard's, and a consequent freeing of (polygenist) racial theory.

Family

Crawfurd married Horatia Ann, daughter of James Perry. From 1821 to 1822, Mrs. Crawfurd had accompanied the Mission to Siam and Cochin China aboard the ''John Adam''. As the ship made way from Bangkok to Hué, Mrs. Crawfurd went ashore on an island in the Gulf of Siam, where she made a considerable impression upon the natives. The writer Oswald John Frederick Crawfurd, born in 1834, was their son. The couple knew John Sterling, and the Carlyles. Thomas Carlyle metHenry Crabb Robinson

Henry Crabb Robinson (13 May 1775 – 5 February 1867) was an English lawyer, remembered as a diarist. He took part in founding London University.

Life

Robinson was born in Bury St. Edmunds, Suffolk, third and youngest son of Henry Robinson ( ...

at dinner at the Crawfurds (25 November 1837, at 27 Wilton Crescent), making a poor impression. Note 14.

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * *Knapman, Gareth (2017)Race and British Colonialism in South-East Asia: John Crawfurd and the politics of equality

Routledge.

Further reading

*Ernest C. T. Chew (2002), "Dr John Crawfurd (1783–1868): The Scotsman Who Made Singapore British", ''Raffles Town Club'', vol. 8 (July–Sept). Singapore : Raffles Town Club. *Knapman, Gareth (2017)Race and British Colonialism in South-East Asia: John Crawfurd and the politics of equality

Routledge.

External links

* *Royal Geographical Society Obituary

from the '' Sydney Herald''

Infopedia page

;Attribution {{DEFAULTSORT:Crawfurd, John 1783 births 1868 deaths 19th-century Scottish medical doctors People from Islay Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Historians of India British East India Company civil servants Fellows of the Royal Society Fellows of the Ethnological Society of London Scottish politicians Scottish diplomats Scottish economics writers British ethnologists Scottish geographers 20th-century Scottish historians Scottish linguists Scottish orientalists Scottish colonial officials Scottish surgeons Scottish travel writers Fellows of the Linnean Society of London Fellows of the Royal Geographical Society Administrators in British Malaya Administrators in British Singapore Governors of the Straits Settlements