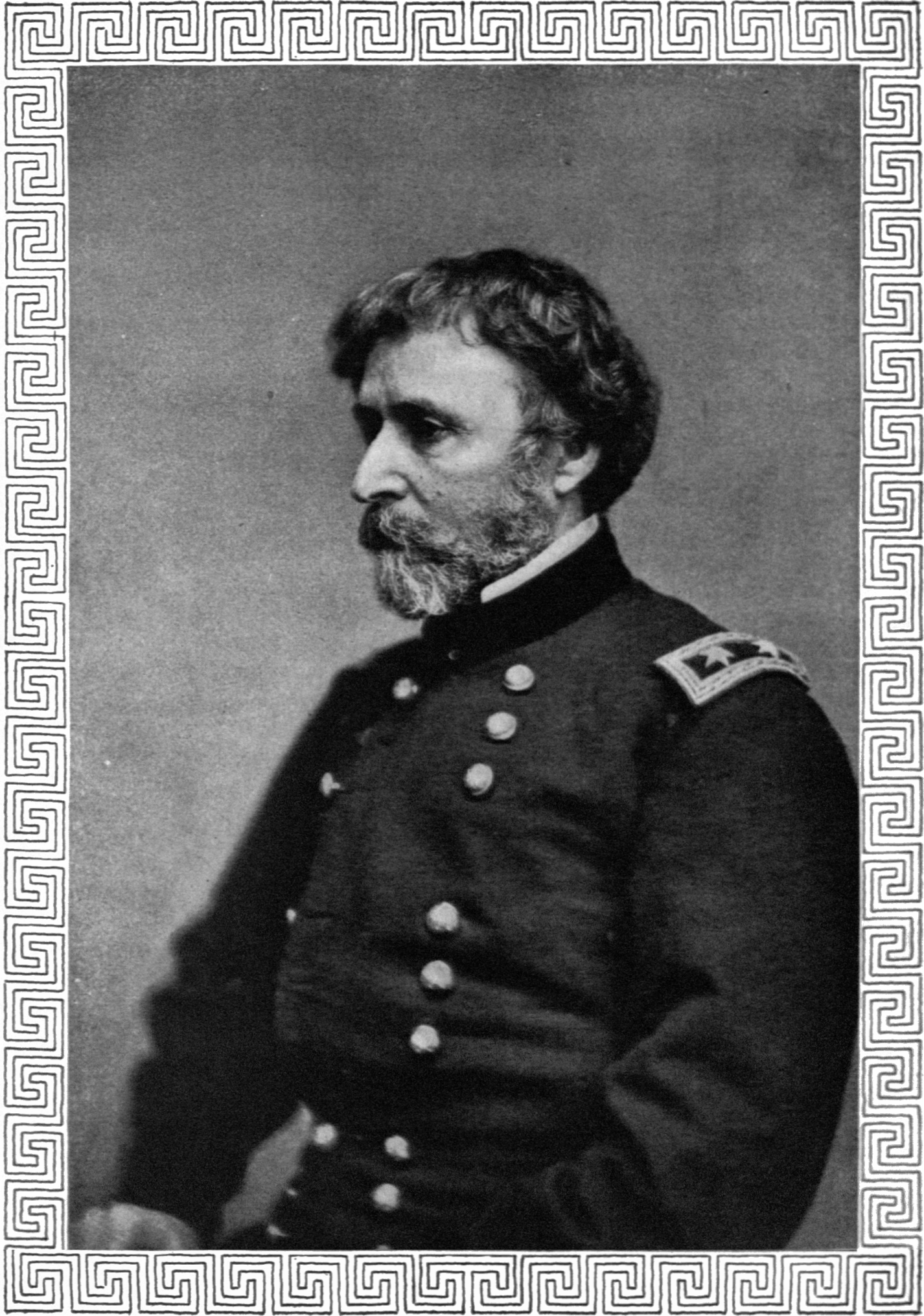

John Charles Frémont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first

Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

nominee for president of the United States in

1856 and founder of the

California Republican Party when he was nominated. He lost the election to Democrat

James Buchanan when

Know Nothings

split the vote.

He was a native of Georgia but an opponent of slavery. In the 1840s, Frémont led five expeditions into the Western United States, the third of which included large-scale killing of indigenous peoples. During the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

, he was a major in the U.S. Army and took control of California from the

California Republic in 1846. Frémont was court-martialed and convicted of mutiny and insubordination after a conflict over who was the rightful

military governor of California. His sentence was commuted and he was reinstated by President

Polk

Polk may refer to:

People

* James K. Polk, 11th president of the United States

* Polk (name), other people with the name

Places

* Polk (CTA), a train station in Chicago, Illinois

* Polk, Illinois, an unincorporated community

* Polk, Missou ...

, but Frémont resigned from the Army. Afterwards, he settled in California at

Monterey

Monterey (; es, Monterrey; Ohlone: ) is a city located in Monterey County on the southern edge of Monterey Bay on the U.S. state of California's Central Coast. Founded on June 3, 1770, it functioned as the capital of Alta California under bot ...

while buying cheap land in the Sierra foothills. Gold was found on his Mariposa ranch, and Frémont became a wealthy man during the

California Gold Rush. He became one of the first two U.S. senators elected from the new state of California in 1850.

At the beginning of the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

in 1861, he was given command of the

Department of the West by President

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

. Frémont had successes during his brief tenure there, though he ran his department autocratically and made hasty decisions without consulting President Lincoln or Army headquarters. He issued

an unauthorized emancipation edict and was relieved of his command for insubordination by Lincoln. After a brief service tenure in the Mountain Department in 1862, Frémont resided in New York, retiring from the army in 1864. He was nominated for president in 1864 by the

Radical Democracy Party, a breakaway faction of abolitionist Republicans, but he withdrew before the election. After the Civil War, he lost much of his wealth in the unsuccessful

Pacific Railroad

The Pacific Railroad (not to be confused with Union Pacific Railroad) was a railroad based in Missouri. It was a predecessor of both the Missouri Pacific Railroad and St. Louis-San Francisco Railway.

The Pacific was chartered by Missouri in 1849 ...

in 1866, and he lost more in the

Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

. Frémont served as

Governor of Arizona

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

from 1878 to 1881. After his resignation as governor, he retired from politics and died destitute in New York City in 1890.

Historians portray Frémont as controversial, impetuous, and contradictory. Some scholars regard him as a military hero of significant accomplishment, while others view him as a failure who repeatedly defeated his own best interests. The keys to Frémont's character and personality, several historians argue, lie in his having been born illegitimate and in his drive for success, need for self-justification, and passive–aggressive behavior. His biographer

Allan Nevins

Joseph Allan Nevins (May 20, 1890 – March 5, 1971) was an American historian and journalist, known for his extensive work on the history of the Civil War and his biographies of such figures as Grover Cleveland, Hamilton Fish, Henry Ford, and J ...

wrote that Frémont lived a dramatic life of remarkable successes and dismal failures.

Early life, education, and early career

John Charles Frémont was born on January 21, 1813, the son of Charles Frémon, a

French-Canadian immigrant school-teacher, and Anne Beverley Whiting, the youngest daughter of socially prominent Virginia planter Col. Thomas Whiting. At age 17, Anne married

Major John Pryor, a wealthy Richmond resident in his early 60s. In 1810, Pryor hired Frémon to tutor his young wife Anne. Pryor confronted Anne when he found out she was having an affair with Frémon. Anne and Frémon fled to Williamsburg on July 10, 1811, later settling in

Norfolk, Virginia, taking with them household slaves Anne had inherited.

[ The couple later settled in ]Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the British colonial capital of the Province of Georgia and later t ...

, where she gave birth to their son Frémont out of wedlock. Pryor published a divorce petition in the ''Virginia Patriot'', and charged that his wife had "for some time past indulged in criminal intercourse". When the Virginia House of Delegates refused Anne's divorce petition, it was impossible for the couple to marry. In Savannah, Anne took in boarders while Frémon taught French and dancing. Their domestic slave, Black Hannah, helped raise young John.[

On December 8, 1818, Frémont's father died in Norfolk, Virginia, leaving Anne a widow to take care of John and several young children alone on a limited inherited income. Anne and her family moved to Charleston, South Carolina. Frémont, knowing his origins and coming from relatively modest means, grew up a proud, reserved, restless loner who although self-disciplined, was ready to prove himself and unwilling to play by the rules. The young Frémont was considered to be "precious, handsome, and daring," having the ability of obtaining protectors. A lawyer, John W. Mitchell, provided for Frémont's early education whereupon Frémont in May 1829 entered Charleston College, teaching at intervals in the countryside, but was expelled for irregular attendance in 1831. Frémont, however, had been grounded in mathematics and natural sciences.

Frémont attracted the attention of eminent South Carolina politician Joel R. Poinsett, an ]Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

supporter, who secured Frémont an appointment as a teacher of mathematics aboard the sloop USS ''Natchez'', sailing the South American seas in 1833. Frémont resigned from the navy and was appointed second lieutenant in the United States Topographical Corps, surveying a route for the Charleston, Louisville, and Cincinnati railroad. Working in the Carolina mountains, Frémont desired to become an explorer. Between 1837 and 1838, Frémont's desire for exploration increased while in Georgia on reconnaissance to prepare for the removal of Cherokee Indians

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, th ...

. When Poinsett became Secretary of War, he arranged for Frémont to assist notable French explorer and scientist Joseph Nicollet

Joseph Nicolas Nicollet (July 24, 1786 – September 11, 1843), also known as Jean-Nicolas Nicollet, was a French geographer, astronomer, and mathematician known for mapping the Upper Mississippi River basin during the 1830s. Nicollet led three ...

in exploring the lands between the Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

and Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

rivers. Frémont became a first rate topographer, trained in astronomy, and geology, describing fauna, flora, soil, and water resources. Gaining valuable western frontier experience Frémont came in contact with notable men including Henry Sibley, Joseph Renville, J.B. Faribault, Étienne Provost, and the Sioux nation.

Marriage and senatorial patronage

Frémont's exploration work with Nicollet brought him in contact with Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri, powerful chairman of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs. Benton invited Frémont to his Washington home where he met Benton's 16-year-old daughter Jessie Benton. A romance blossomed between the two; however, Benton was initially against it because Frémont was not considered upper society. In 1841, Frémont (age 28) and Jessie eloped and were married by a Catholic priest.

Frémont's exploration work with Nicollet brought him in contact with Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri, powerful chairman of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs. Benton invited Frémont to his Washington home where he met Benton's 16-year-old daughter Jessie Benton. A romance blossomed between the two; however, Benton was initially against it because Frémont was not considered upper society. In 1841, Frémont (age 28) and Jessie eloped and were married by a Catholic priest.Oregon Trail

The Oregon Trail was a east–west, large-wheeled wagon route and emigrant trail in the United States that connected the Missouri River to valleys in Oregon. The eastern part of the Oregon Trail spanned part of what is now the state of Kans ...

, the Oregon Country, the Great Basin, and Sierra Nevada Mountains to California. Through his power and influence, Senator Benton obtained for Frémont the leadership, funding, and patronage of three expeditions.

Frémont's explorations

The opening of the American West began in 1804, when the

The opening of the American West began in 1804, when the Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery Expedition, was the United States expedition to cross the newly acquired western portion of the country after the Louisiana Purchase. The Corps of Discovery was a select gr ...

(led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark

William Clark (August 1, 1770 – September 1, 1838) was an American explorer, soldier, Indian agent, and territorial governor. A native of Virginia, he grew up in pre-statehood Kentucky before later settling in what became the state of Miss ...

) started exploration of the new Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

territory to find a northwest passage up the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contin ...

. President Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

had envisioned a Western empire, and also sent the Pike Expedition

The Pike Expedition (July 15, 1806 – July 1, 1807) was a military party sent out by President Thomas Jefferson and authorized by the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States ( ...

under Zebulon Pike

Zebulon Montgomery Pike (January 5, 1779 – April 27, 1813) was an American brigadier general and explorer for whom Pikes Peak in Colorado was named. As a U.S. Army officer he led two expeditions under authority of President Thomas Jefferson ...

to explore the southwest.[Rhonda (2012), p. 64] American and European fur trappers

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the most ...

, including Peter Skene Ogden and Jedediah Smith, explored much of the American West in the 1820s.[Beck (1989), pp. 27–28][Barbour (2012), p. 5][Morgan (1953), p. 7] Frémont, who would later be known as ''The Pathfinder'', carried on this tradition of Western overland exploration, building on and adding to the work of earlier pathfinders to expand knowledge of the American West. Frémont's talent lay in his scientific documentation, publications, and maps made based on his expeditions, making the American West accessible for many Americans. Beginning in 1842, Frémont led five western expeditions, however, between the third and fourth expeditions, Frémont's career took a fateful turn because of the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

. Frémont's initial explorations, his timely scientific reports, co-authored by his wife Jessie, and their romantic writing style, encouraged Americans to travel West. A series of seven maps produced from his findings, published by the Senate in 1846, served as a guide for thousands of American emigrants, depicting the entire length of the Oregon Trail

The Oregon Trail was a east–west, large-wheeled wagon route and emigrant trail in the United States that connected the Missouri River to valleys in Oregon. The eastern part of the Oregon Trail spanned part of what is now the state of Kans ...

.

First expedition (1842)

When Nicollet was too ill to continue any further explorations, Frémont was chosen to be his successor. His first important expedition was planned by Benton, Senator Lewis Linn

Lewis Fields Linn (November 5, 1796October 3, 1843) was a physician and politician who represented his home state of Missouri in the United States Senate from 1833 to his death.

Early life

Linn was born near Louisville, Kentucky on November 5, 17 ...

, and other Westerners interested in acquiring the Oregon Territory. The scientific expedition started in the summer of 1842 and was to explore the Wind River of the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico ...

, examine the Oregon Trail

The Oregon Trail was a east–west, large-wheeled wagon route and emigrant trail in the United States that connected the Missouri River to valleys in Oregon. The eastern part of the Oregon Trail spanned part of what is now the state of Kans ...

through the South Pass, and report on the rivers and the fertility of the lands, find optimal sites for forts, and describe the mountains beyond in Wyoming. By chance meeting, Frémont was able to gain the valuable assistance of mountain man and guide Kit Carson

Christopher Houston Carson (December 24, 1809 – May 23, 1868) was an American frontiersman. He was a fur trapper, wilderness guide, Indian agent, and U.S. Army officer. He became a frontier legend in his own lifetime by biographies and ...

. Frémont and his party of 25 men, including Carson, embarked from the Kansas River

The Kansas River, also known as the Kaw, is a river in northeastern Kansas in the United States. It is the southwesternmost part of the Missouri River drainage, which is in turn the northwesternmost portion of the extensive Mississippi River dr ...

on June 15, 1842, following the Platte River

The Platte River () is a major river in the State of Nebraska. It is about long; measured to its farthest source via its tributary, the North Platte River, it flows for over . The Platte River is a tributary of the Missouri River, which itsel ...

to the South Pass, and starting from Green River he explored the Wind River Range

The Wind River Range (or "Winds" for short) is a mountain range of the Rocky Mountains in western Wyoming in the United States. The range runs roughly NW–SE for approximately . The Continental Divide follows the crest of the range and incl ...

. Frémont climbed a 13,745-foot mountain, '' Frémont's Peak'', planted an American flag, claiming the Rocky Mountains and the West for the United States. On Frémont's return trip he and his party carelessly rafted the swollen Platte River losing much of his equipment. His five-month exploration, however, was a success, returning to Washington in October. Frémont and his wife Jessie wrote a ''Report of the Exploring Expedition to the Rocky Mountains'' (1843), which was printed in newspapers across the country; the public embraced his vision of the west not as a place of danger but wide open and inviting lands to be settled.

Second expedition (1843–1844)

Frémont's successful first expedition led quickly to a second; it began in the summer of 1843. The more ambitious goal this time was to map and describe the second half of the Oregon Trail, find an alternate route to the South Pass, and push westward toward the Pacific Ocean on the Columbia River in Oregon Country. Frémont and his almost 40 well-equipped men left the Missouri River in May after he controversially obtained a 12-pound howitzer cannon in St. Louis. Frémont invited Carson on the second expedition, due to his proven skills, and he joined Frémont's party on the Arkansas River. Unable to find a new route through Colorado to the South Pass, Frémont took to the regular Oregon Trail, passing the main body of the great immigration of 1843. His party stopped to explore the northern part of the Great Salt Lake, then traveling by way Fort Hall and Fort Boise to Marcus Whitman

Marcus Whitman (September 4, 1802 – November 29, 1847) was an American physician and missionary.

In 1836, Marcus Whitman led an overland party by wagon to the West. He and his wife, Narcissa, along with Reverend Henry Spalding and his wife, E ...

's mission

Mission (from Latin ''missio'' "the act of sending out") may refer to:

Organised activities Religion

*Christian mission, an organized effort to spread Christianity

*Mission (LDS Church), an administrative area of The Church of Jesus Christ of ...

, along the Snake River to the Columbia River and in to Oregon. Frémont's endurance, energy, and resourcefulness over the long journey was remarkable. Traveling west along the Columbia, they came within sight of the Cascade Range peaks and mapped Mount St. Helens

Mount St. Helens (known as Lawetlat'la to the indigenous Cowlitz people, and Loowit or Louwala-Clough to the Klickitat) is an active stratovolcano located in Skamania County, Washington, in the Pacific Northwest region of the United St ...

and Mount Hood. Reaching the Dalles on November 5, Frémont left his party and traveled to the British-held Fort Vancouver

Fort Vancouver was a 19th century fur trading post that was the headquarters of the Hudson's Bay Company's Columbia Department, located in the Pacific Northwest. Named for Captain George Vancouver, the fort was located on the northern bank of th ...

for supplies.

Rather than turning around and heading back to St. Louis, Frémont resolved to explore the Great Basin between the Rockies and the Sierras and fulfill Benton's dream of acquiring the West for the United States. Frémont and his party turned south along the eastern flank of the Cascades through the Oregon territory to Pyramid Lake, which he named. Looping back to the east to stay on the eastern side of the Sierra Nevada mountain range, they turned south again as far as present-day Minden, Nevada, reaching the Carson River on January 18, 1844. From an area near what later became Virginia City, Frémont turned west into the cold and snowy Sierra Nevada, becoming one of the first Americans to see Lake Tahoe. Carson successfully led Frémont's party through a new pass over the high Sierras, which Frémont named Carson Pass

Carson Pass is a mountain pass on the crest of the central Sierra Nevada, in the Eldorado National Forest and Alpine County, eastern California.

The pass is traversed by California State Route 88. It lies on the Great Basin Divide, with the West ...

in his honor. Frémont and his party then descended the American River

, name_etymology =

, image = American River CA.jpg

, image_size = 300

, image_caption = The American River at Folsom

, map = Americanrivermap.png

, map_size = 300

, map_caption ...

valley to Sutter's Fort (Spanish: Nueva Helvetia) at present-day Sacramento, California

)

, image_map = Sacramento County California Incorporated and Unincorporated areas Sacramento Highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 250x200px

, map_caption = Location within Sacramento ...

, in early March. Captain John Sutter

John Augustus Sutter (February 23, 1803 – June 18, 1880), born Johann August Sutter and known in Spanish as Don Juan Sutter, was a Swiss immigrant of Mexican and American citizenship, known for establishing Sutter's Fort in the area th ...

, a German-Mexican (and later American by treaty

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal pe ...

) immigrant and founder of the fort, received Frémont gladly and refitted his expedition party. While at Sutter's Fort, Frémont talked to American settlers, who were growing numerous, and found that Mexican authority over California was very weak.

Leaving Sutter's Fort, Frémont and his men headed south following Smith's trail on the eastern edge of the San Joaquin Valley

The San Joaquin Valley ( ; es, Valle de San Joaquín) is the area of the Central Valley of the U.S. state of California that lies south of the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta and is drained by the San Joaquin River. It comprises seven ...

until he struck the " Spanish Trail" between Los Angeles and Santa Fe, and headed east through Tehachapi Pass and present-day Las Vegas

Las Vegas (; Spanish for "The Meadows"), often known simply as Vegas, is the 25th-most populous city in the United States, the most populous city in the state of Nevada, and the county seat of Clark County. The city anchors the Las Vegas ...

before regaining Smith's trail north through Utah and back to South Pass. Exploring the Great Basin, Frémont verified that all the land (centered on modern-day Nevada between Reno and Salt Lake City) was endorheic

An endorheic basin (; also spelled endoreic basin or endorreic basin) is a drainage basin that normally retains water and allows no outflow to other external bodies of water, such as rivers or oceans, but drainage converges instead into lakes ...

, without any outlet rivers flowing towards the sea. The finding contributed greatly to a better understanding of North American geography, and disproved a longstanding legend of a 'Buenaventura River The non-existent Buenaventura River, alternatively San Buenaventura River or Río Buenaventura, was once believed to run from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean through the Great Basin region of what is now the western United States. The river ...

' that flowed out the Great Basin across the Sierra Nevada. After exploring Utah Lake, Frémont traveled by way of the Pueblo until he reached Bent's Fort on the Arkansas River. In August 1844, Frémont and his party finally arrived back in St. Louis, enthusiastically received by the people, ending the journey that lasted over one year. His wife Jessie and Frémont returned to Washington, where the two wrote a second report, scientific in detail, showing the Oregon Trail was not difficult to travel and that the Northwest had fertile land. Senator Buchanan ordered the printing of 10,000 copies to be used by settlers and fervor the popular movement of national expansion.

Third expedition (1845)

With the backdrop of an impending war with Mexico, after James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. He previously was the 13th speaker of the House of Representatives (1835–1839) and ninth governor of Tennessee (183 ...

had been elected president, Benton quickly organized a third expedition for Frémont. The plan for Frémont under the War Department was to survey the central Rockies, the Great Salt Lake region, and part of the Sierra Nevada. Back in St. Louis, Frémont organized an armed surveying expedition of 60 men, with Carson as a guide, and two distinguished scouts, Joseph Walker and Alexis Godey. Working with Benton and Secretary of Navy George Bancroft

George Bancroft (October 3, 1800 – January 17, 1891) was an American historian, statesman and Democratic politician who was prominent in promoting secondary education both in his home state of Massachusetts and at the national and internati ...

, Frémont was secretly told that if war started with Mexico he was to turn his scientific expedition into a military force. President Polk, who had met with Frémont at a cabinet meeting, was set on taking California. Frémont desired to conquer California for its beauty and wealth, and would later explain his very controversial conduct there.

On June 1, 1845, Frémont and his armed expedition party left St. Louis having the immediate goal to locate the source of the Arkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. It generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's source basin lies in the western United Stat ...

, on the east side of the Rocky Mountains. Frémont and his party struck west by way of Bent's Fort, The Great Salt Lake, and the "Hastings Cut-Off". When Frémont reached the Ogden River, which he renamed the Humboldt, he divided his party in two to double his geographic information. Upon reaching the Arkansas River, Frémont suddenly made a blazing trail through Nevada straight to California, having a rendezvous with his men from the split party at Walker Lake in west-central Nevada.

Attacks against Native Americans in California and Oregon Country (1845–1846)

Taking 16 men, Frémont split his party again, arriving at Sutter's Fort in the Sacramento Valley on December 9. Frémont promptly sought to stir up patriotic enthusiasm among the American settlers there. He promised that if war with Mexico started, his military force would protect the settlers. Frémont went to Monterey, California, to talk with the American consul, Thomas O. Larkin, and Mexican ''commandant'' Jose Castro, under the pretext of gaining fuller supplies. In February 1846, Frémont reunited with 45 men of his expedition party near Mission San José, giving the United States a formidable military army in California. Castro and Mexican officials were suspicious of Frémont and he was ordered to leave the country. Frémont and his men withdrew and camped near the summit of what is now named Fremont Peak Fremont Peak can refer to one of several peaks. In the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in Nor ...

. Headstrong and with much audacity, Frémont raised the United States Flag in defiance of Mexican authority.

Playing for time, after a four-day standoff and Castro having a superior number of Mexican troops, Frémont and his men went north to Oregon, executing the Sacramento River massacre

The Sacramento River massacre refers to the killing of many Wintu people on the banks of the Sacramento River on 5 April 1846 by an expedition band led by Captain John C. Frémont of Virginia. Estimates range from 125 to 900.

History Background

T ...

along the way. Estimates of the casualties vary. Expedition members Thomas E. Breckenridge and Thomas S. Martin claim the number of Native Americans killed as "120–150" and "over 175" respectively, but the eyewitness Tustin claimed that at least 600–700 Native Americans were killed on land, with another 200 or more dying in the water. There are no records of any expedition members being killed or even wounded in the massacre. Kit Carson

Christopher Houston Carson (December 24, 1809 – May 23, 1868) was an American frontiersman. He was a fur trapper, wilderness guide, Indian agent, and U.S. Army officer. He became a frontier legend in his own lifetime by biographies and ...

, one of the mounted attackers, later stated, "It was a perfect butchery."

Fremont and his men eventually made their way to camp at Klamath Lake

Upper Klamath Lake (sometimes called Klamath Lake) ( Klamath: ?ews, "lake" ) is a large, shallow freshwater lake east of the Cascade Range in south-central Oregon in the United States. The largest body of fresh water by surface area in Oregon, it ...

, killing Native Americans on sight as they went. On May 8, Frémont was overtaken by Lieutenant Archibald Gillespie from Washington, who gave him copies of dispatches he had previously given to Larkin. Gillespie told Frémont secret instructions from Benton and Buchanan justifying aggressive action and that a declaration of war with Mexico was imminent. On May 9, 1846, Native Americans ambushed his expedition party in retaliation for numerous killings of Native Americans that Frémont's men had engaged in along the trail, killing three members of Frémont's party in their sleep, including a Native American who was traveling with Frémont. Frémont retaliated by attacking a Klamath fishing village named ''Dokdokwas'' the following day in the Klamath Lake massacre The Klamath Lake massacre refers to the murder of at least fourteen Klamath people on the shores of Klamath Lake, now in Oregon in the United States, on 12 May 1846 by a band led by John C. Frémont and Kit Carson.

History Background

The expansioni ...

, although the people living there might not have been involved in the first action.[Sides, 2006, p. 154] The village was at the junction of the Williamson River and Klamath Lake. On May 12, 1846, the Frémont group completely destroyed it, killing at least fourteen people. Frémont believed that the British were responsible for arming and encouraging the Native Americans to attack his party. Afterward, Carson was nearly killed by a Klamath warrior. As Carson's gun misfired, the warrior drew to shoot a poison arrow; however, Frémont, seeing that Carson was in danger, trampled the warrior with his horse. Carson felt that he owed Frémont his life.

Mexican–American War (1846–1848)

Having reentered Mexican California headed south, Frémont and his army expedition stopped off at Peter Lassen

Peter Lassen (October 31, 1800 – April 26, 1859), later known in Spanish as Don Pedro Lassen, was a Danish-born Californian ranchero and gold prospector. Born in Denmark, Lassen immigrated at age 30 to Massachusetts, before eventually final ...

's Ranch on May 24, 1846. Frémont learned from Lassen that the USS ''Portsmouth'', commanded by John B. Montgomery, was anchored at Sausalito

Sausalito (Spanish for "small willow grove") is a city in Marin County, California, United States, located southeast of Marin City, south-southeast of San Rafael, and about north of San Francisco from the Golden Gate Bridge.

Sausalito's ...

. Frémont sent Lt. Gillespie to Montgomery and requested supplies including 8000 percussion caps, 300 pounds of rifle lead, one keg of powder, and food provisions, intending to head back to St. Louis. On May 31, Frémont made his camp on the Bear and Feather rivers 60 miles north of Sutter's Fort, where American immigrants ready for revolt against Mexican authority joined his party. From there he made another attack on local Native Americans in a rancheria (see Sutter Buttes massacre The Sutter Buttes massacre refers to the murder of a large group of Californian Indians on the Sacramento River near Sutter Buttes in June 1846 by a militarized expeditionary band led by Captain John C. Frémont of Virginia. Estimates of the numbe ...

). In early June, believing war with Mexico to be a virtual certainty, Frémont joined the Sacramento Valley insurgents in a "silent partnership", rather than head back to St. Louis, as originally planned. On June 10, instigated by Frémont, four men from Frémont's party and 10 rebel volunteers seized 170 horses intended for Castro's Army and returned them to Frémont's camp. According to historian H. H. Bancroft, Frémont incited the American settlers indirectly and "guardedly" to revolt. On June 14, 34 armed rebels independently captured Sonoma, the largest settlement in northern California, and forced the surrender of Colonel Mariano Vallejo

Don Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo (4 July 1807 – 18 January 1890) was a Californio general, statesman, and public figure. He was born a subject of Spain, performed his military duties as an officer of the Republic of Mexico, and shaped the trans ...

, taking him and three others prisoner. The following day, the rebelling Americans, who were called ''Osos'' (Spanish for "bears") by the residents of Sonoma, amidst a brandy-filled party, hoisted a roughly sewn flag and formed the Bear Flag Republic, electing William Ide as their leader. The four prisoners were then taken to Frémont's camp 80 miles away. On June 15, the prisoners and escorts arrived at Frémont's new camp on the American River, but Frémont publicly denied responsibility for the raid. The escorts then removed the prisoners south to Sutter's Fort, where they were imprisoned by Sutter under Frémont's orders. It was at this time Frémont began signing letters as "Military Commander of U.S. Forces in California".

On June 24, Frémont and his men, upon hearing that Californio (people of Spanish or Mexican descent) Juan N. Padilla had captured, tortured, killed, and mutilated the bodies of two Osos and held others prisoner, rode to Sonoma, arriving on June 25. On June 26, Frémont, his own men, Lieutenant Henry Ford and a detachment of Osos, totalling 125 men, rode south to San Rafael, searching for Captain Joaquin de la Torre and his lancers, rumored to have been ordered by Castro to attack Sonoma, but was unable to find them. On June 28, General Castro, on the other side of San Francisco Bay, sent a row boat across to Point San Pablo on the shores of San Rafael with a message for de la Torre. Kit Carson, Granville Swift and Sam Neal rode to the beach to intercept the three unarmed men who came ashore, including Don José Berreyesa and the 20-year-old Haro twin brothers Ramon and Francisco, sons of Don Francisco de Haro. The three were murdered in cold blood. Exactly who committed the murders is a point of controversy, but later accounts point to Carson acting at the behest, if not the order, of Frémont.

On July 1, Commodore John D. Sloat, commanding the U.S. Navy's Pacific Squadron, sailed into Monterey harbor with orders to seize San Francisco Bay and blockade the other California ports upon learning "without a doubt" that war had been declared. On July 5, Sloat received a message from Montgomery reporting the events in Sonoma and Frémont's involvement. Believing Frémont to be acting on orders from Washington, Sloat began to carry out his orders. Early on July 7, 225 sailors and marines on the United States Navy frigate USS ''Savannah'' and the two sloops

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular ...

, USS ''Cyane'' and USS ''Levant'' landed and captured Monterey

Monterey (; es, Monterrey; Ohlone: ) is a city located in Monterey County on the southern edge of Monterey Bay on the U.S. state of California's Central Coast. Founded on June 3, 1770, it functioned as the capital of Alta California under bot ...

with no shots being fired and raised the flag of the United States. Commodore Sloat had his proclamation read and posted in English and Spanish: "... henceforth California would be a portion of the United States." On July 10, Frémont received a message from Montgomery that the U.S. Navy had occupied Monterey and Yerba Buena. Two days later, Frémont received a letter from Sloat, describing the capture of Monterey and ordering Frémont to bring at least 100 armed men to Monterey. Frémont would bring 160 men. On July 15, Commodore Robert F. Stockton arrived in Monterey to replace the 65-year-old Sloat in command of the Pacific Squadron. Sloat named Stockton commander-in-chief of all land forces in California. On July 19, Frémont's party entered Monterey, where he met with Sloat on board the ''Savannah''. When Sloat learned that Frémont had acted on his own authority (thus raising doubt about a war declaration), he retired to his cabin. On July 23, Stockton mustered Frémont's party and the former Bear Flaggers into military service as the "Naval Battalion of Mounted Volunteer Riflemen" with Frémont appointed major in command of the California Battalion, which he had helped form with his survey crew and volunteers from the Bear Flag Republic, now totaling 428 men. Stockton incorporated the California Battalion into the U.S. military giving them soldiers pay. Frémont and about 160 of his troops went by ship to San Diego, and with Stockton's marines took Los Angeles on August 13. Frémont afterwards went north to recruit more Californians into his battalion. In late 1846, under orders from Stockton, Frémont led a military expedition of 300 men to capture Santa Barbara. In September, Mexican Californians unwilling to be ruled by the United States, under José María Flores, fought back and retook Los Angeles, driving out Americans.

In December 1846, U.S. Brigadier General Stephen W. Kearny arrived in California under "orders from President Polk

James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. He previously was the 13th speaker of the House of Representatives (1835–1839) and ninth governor of Tennessee (183 ...

" after taking New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ke ...

, then to march onto "California where, ''"Should you conquer and take possession of California, you will establish a civil government."'' Kearny, who had earlier trimmed his forces from 300 to 100 dragoons, based upon Kit Carson

Christopher Houston Carson (December 24, 1809 – May 23, 1868) was an American frontiersman. He was a fur trapper, wilderness guide, Indian agent, and U.S. Army officer. He became a frontier legend in his own lifetime by biographies and ...

's dispatches he was carrying to Washington, stating that Stockton and Fremont had successfully taken control of California. Unknown to Carson at this time, the Californians had revolted, which would lead Kearny to a disastrous attack on waiting Mexican lancers at the Battle of San Pasqual, losing 19 men killed and being himself seriously lanced. He was later reinforced when Stockton sent troops to drive off Pio Pico

Pio may refer to:

Places

* Pio Lake, Italy

* Pio Island, Solomon Islands

* Pio Point, Bird Island, south Atlantic Ocean

People

* Pio (given name)

* Pio (surname)

* Pio (footballer, born 1986), Brazilian footballer

* Pio (footballer, born 1 ...

and his forces. It was at this time a dispute began between Stockton and Kearny over who had control of the military, but the two managed to work together to stop the Los Angeles uprising. Frémont led his unit over the Santa Ynez Mountains

The Santa Ynez Mountains are a portion of the Transverse Ranges, part of the Pacific Coast Ranges of the west coast of North America. It is the westernmost range in the Transverse Ranges.

The range is a large fault block of Cenozoic age create ...

at San Marcos Pass in a rainstorm on the night of December 24, 1846. Despite losing many of his horses, mules and cannons, which slid down the muddy slopes during the rainy night, his men regrouped in the foothills (behind what is today Rancho Del Ciervo) the next morning, and captured the Presidio of Santa Barbara

A presidio ( en, jail, fortification) was a fortified base established by the Spanish Empire around between 16th and 18th centuries in areas in condition of their control or influence. The presidios of Spanish Philippines in particular, were cen ...

and the town without bloodshed. A few days later, Frémont led his men southeast towards Los Angeles. Fremont accepted Andres Pico's surrender upon signing the Treaty of Cahuenga on January 13, 1847, which terminated the war in upper California. It was at this time Kearny ordered Frémont to join his military dragoons, but Frémont refused, believing he was under authority of Stockton.

Court martial and resignation

On January 16, 1847, Commodore Stockton appointed Frémont military governor of California following the Treaty of Cahuenga, and then left Los Angeles. Frémont functioned for a few weeks without controversy, but he had little money to administer his duties as governor. Previously, unknown to Stockton and Frémont, the Navy Department had sent orders for Sloat and his successors to establish military rule over California. These orders, however, postdated Kearny's orders to establish military control over California. Kearny did not have the troop strength to enforce those orders, and was forced to rely on Stockton's Marines and Frémont's California Battalion until army reinforcements arrived. On February 13, specific orders were sent from Washington through Commanding General Winfield Scott giving Kearny the authority to be military governor of California. Kearny, however, did not directly inform Frémont of these orders from Scott. Kearny ordered that Frémont's California Battalion be enlisted into the U.S. Army and Frémont bring his battalion archives to Kearny's headquarters in Monterey.

Frémont delayed obeying these orders, hoping Washington would send instructions for Frémont to be military governor. Also, the California Battalion refused to join the U.S. Army. Frémont gave orders for the California Battalion not to surrender arms, rode to Monterey to talk to Kearny, and told Kearny he would obey orders. Kearny sent Col. Richard B. Mason, who was to succeed Kearny as military governor of California, to Los Angeles, both to inspect troops and to give Frémont further orders. Frémont and Mason, however, were at odds with each other and Frémont challenged Mason to a duel. After an arrangement to postpone the duel, Kearny rode to Los Angeles and refused Frémont's request to join troops in Mexico. Ordered to march with Kearny's army back east, Frémont was arrested on August 22, 1847, when they arrived at Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., and the oldest perma ...

. He was charged with mutiny, disobedience of orders, assumption of powers, and several other military offenses. Ordered by Kearny to report to the adjutant general

An adjutant general is a military chief administrative officer.

France

In Revolutionary France, the was a senior staff officer, effectively an assistant to a general officer. It was a special position for lieutenant-colonels and colonels in staf ...

in Washington to stand for court-martial, Frémont was found innocent of mutiny, but was convicted on January 31, 1848, of disobedience toward a superior officer and military misconduct.

While approving the court's decision, President James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. He previously was the 13th speaker of the House of Representatives (1835–1839) and ninth governor of Tennessee (183 ...

quickly commuted Frémont's sentence of dishonorable discharge

A military discharge is given when a member of the armed forces is released from their obligation to serve. Each country's military has different types of discharge. They are generally based on whether the persons completed their training and the ...

and reinstated him into the Army, due to his war services. Polk felt that Frémont was guilty of disobeying orders and misconduct, but he did not believe Frémont was guilty of mutiny. Additionally, Polk wished to placate Thomas Hart Benton, a powerful senator and Frémont's father-in-law, who felt that Frémont was innocent. Frémont, only gaining a partial pardon from Polk, resigned his commission in protest and settled in California. Despite the court-martial, Frémont remained popular among the American public.

Historians are divided in their opinions on this period of Frémont's career. Mary Lee Spence and Donald Jackson, editors of a large collection of letters by Fremont and others dating from this period, concluded that "...in the California episode, Frémont was as often right as wrong. And even a cursory investigation of the court-martial record produces one undeniable conclusion: neither side in the controversy acquitted itself with distinction." Allan Nevins states that Kearny:

: was a stern-tempered soldier who made few friends and many enemies – who has been justly characterized by the most careful historian of the period, Justin H. Smith, as "grasping, jealous, domineering, and harsh." Possessing these traits, feeling his pride stung by his defeat at San Pasqual, and anxious to assert his authority, he was no sooner in Los Angeles than he quarreled bitterly with Stockton; and Frémont was not only at once involved in this quarrel, but inherited the whole burden of it as soon as Stockton left the country.

Theodore Grivas wrote that "It does not seem quite clear how Frémont, an army officer, could have imagined that a naval officer tocktoncould have protected him from a charge of insubordination toward his superior officer earny. Grivas goes on to say, however, that "This conflict between Kearny, Stockton, and Frémont perhaps could have been averted had methods of communication been what they are today."

Fourth expedition (1848–1849)

Intent on restoring his honor and explorer reputation after his court martial, in 1848, Frémont and his father-in-law Sen. Benton developed a plan to advance their vision of Manifest Destiny. With a keen interest in the potential of railroads, Sen. Benton had sought support from the Senate for a railroad connecting St. Louis to San Francisco along the 38th parallel, the latitude which both cities approximately share. After Benton failed to secure federal funding, Frémont secured private funding. In October 1848 he embarked with 35 men up the Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

, Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to th ...

and Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the O ...

rivers to explore the terrain. The artists and brothers Edward Kern and Richard Kern, and their brother Benjamin Kern, were part of the expedition, but Frémont was unable to obtain the valued service of Kit Carson as guide as in his previous expeditions.

On his party's reaching Bent's Fort

Bent's Old Fort is an 1833 fort located in Otero County in southeastern Colorado, United States. A company owned by Charles Bent and William Bent and Ceran St. Vrain built the fort to trade with Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho Plains Indians and ...

, he was strongly advised by most of the trappers against continuing the journey. Already a foot of snow was on the ground at Bent's Fort, and the winter in the mountains promised to be especially snowy. Part of Frémont's purpose was to demonstrate that a 38th parallel railroad would be practical year-round. At Bent's Fort, he engaged "Uncle Dick" Wootton as guide, and at what is now Pueblo, Colorado

Pueblo () is a home rule municipality that is the county seat and the most populous municipality of Pueblo County, Colorado, United States. The city population was 111,876 at the 2020 United States Census, making Pueblo the ninth most populo ...

, he hired the eccentric Old Bill Williams and moved on.

Had Frémont continued up the Arkansas, he might have succeeded. On November 25 at what is now Florence, Colorado

The City of Florence is a Statutory City located in Fremont County, Colorado, United States. The city population was 3,822 at the 2020 United States Census. Florence is a part of the Cañon City, CO Micropolitan Statistical Area and the Front ...

, he turned sharply south. By the time his party crossed the Sangre de Cristo Range

, country= United States

, subdivision1= Colorado

, subdivision2_type= Counties

, subdivision2=

, parent= Sangre de Cristo Mountains, Rocky Mountains

, borders_on=

, geology=

, age=

, orogeny= Fault-block mountains

, area_mi2= ...

via Mosca Pass, they had already experienced days of bitter cold, blinding snow and difficult travel. Some of the party, including the guide Wootton, had already turned back, concluding that further travel would be impossible. Benjamin Kern and "Old Bill" Williams were killed while retracing the expedition trail to look for gear and survivors.

Although the passes through the Sangre de Cristo had proven too steep for a railroad, Frémont pressed on. From this point the party might still have succeeded had they gone up the Rio Grande to its source, or gone by a more northerly route, but the route they took brought them to the very top of Mesa Mountain. By December 12, on Boot Mountain, it took ninety minutes to progress three hundred yards. Mules began dying and by December 20, only 59 animals remained alive.

It was not until December 22 that Frémont acknowledged that the party needed to regroup and be resupplied. They began to make their way to Taos in the New Mexico Territory. By the time the last surviving member of the expedition made it to Taos on February 12, 1849, 10 of the party had died. Except for the efforts of member Alexis Godey, another 15 would have been lost. After recuperating in Taos, Frémont and only a few of the men left for California via an established southern trade route.

Edward and Richard Kern joined J.H. Simpson's military reconnaissance expedition to the Navajos in 1849, and gave the American public some of its earliest authentic graphic images of the people and landscape of Arizona, New Mexico, and southern Colorado; with views of Canyon de Chelly

Canyon de Chelly National Monument ( ) was established on April 1, 1931, as a unit of the National Park Service. Located in northeastern Arizona, it is within the boundaries of the Navajo Nation and lies in the Four Corners region. Reflecting ...

, Chaco Canyon

Chaco Culture National Historical Park is a United States National Historical Park in the American Southwest hosting a concentration of pueblos. The park is located in northwestern New Mexico, between Albuquerque and Farmington, in a remote c ...

, and El Morro (Inscription Rock).

In 1850, Frémont was awarded the Patron's Medal

The Royal Geographical Society's Gold Medal consists of two separate awards: the Founder's Medal 1830 and the Patron's Medal 1838. Together they form the most prestigious of the society's awards. They are given for "the encouragement and promoti ...

by the Royal Geographical Society for his various exploratory efforts.

''Rancho Las Mariposas''

On February 10, 1847, Frémont purchased seventy square miles of land in the Sierra foothills, called ''Las Mariposas'', through land speculator Thomas Larkin, for $3,000. ''Las Mariposas'' had previously been owned by Juan Bautista Alvarado, former California governor, and his wife Martina Caston de Alvarado. Frémont had hoped ''Las Mariposas'' was near San Francisco or Monterey, but was disappointed when he found out it was farther inland by Yosemite, on the Miwok

The Miwok (also spelled Miwuk, Mi-Wuk, or Me-Wuk) are members of four linguistically related Native American groups indigenous to what is now Northern California, who traditionally spoke one of the Miwok languages in the Utian family. The word ...

Indian's hunting and gathering grounds. After his court martial in 1848, Frémont moved to ''Las Mariposas'' and became a rancher, borrowing money from his father-in-law Benton and Senator John Dix to construct a house, corral, and barn. Frémont ordered a sawmill and had it shipped by the Aspinwall steamer ''Fredonia'' to ''Las Mariposas''. Frémont was informed by Sonora Mexicans that gold had been discovered on his property.Dictionary of American Biography

The ''Dictionary of American Biography'' was published in New York City by Charles Scribner's Sons under the auspices of the American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS).

History

The dictionary was first proposed to the Council in 1920 by hi ...

, p. 22Hiland Hall

Hiland Hall (July 20, 1795 – December 18, 1885) was an American lawyer and politician who served as 25th governor of Vermont and a United States representative.

Biography

Hall was born in Bennington, Vermont. He attended the common schools, s ...

, a former Governor of Vermont

The governor of Vermont is the head of government of Vermont. The officeholder is elected in even-numbered years by direct voting for a term of 2 years. Vermont and bordering New Hampshire are the only states to hold gubernatorial elections every ...

, was appointed chairman of the federal commission created to settle Mexican land titles in California; he traveled to San Francisco to begin his work, and his son-in-law Trenor W. Park traveled with him. Frémont hired Park as a managing partner to oversee the day-to-day activities of the estate, and Mexican laborers to wash out the gold on his property in exchange for a percentage of the profits.[ Frémont acquired large landholdings in San Francisco, and while developing his ''Las Mariposas'' gold ranch, he lived a wealthy lifestyle in Monterey.][

Legal issues, however, soon mounted over property and mineral rights. Disputes erupted as squatters moved on Frémont's ''Las Mariposas'' land mining for gold. There was question whether the three mining districts on the land were public domain, while the Merced Mining Company was actively mining on Frémont's property. Since Alvarado had purchased ''Las Mariposas'' on a "floating grant", the property borders were not precisely defined by the Mexican government. Alvarado's ownership of the land was legally contested since Alvarado never actually settled on the property as required by Mexican law. All of these matters lingered and were argued in court for many years until the Supreme Court finally ruled in Frémont's favor in 1856. Although Frémont's legal victory allowed him to keep his wealth, it created lingering animosity among his neighbors.

During the late 1850s, Frederick H. Billings, a partner in the Halleck, Peachy & Billings law firm that employed Park, partnered with Frémont in several successful business ventures.]American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, Billings acted as Frémont's agent when Frémont took the initiative to purchase arms in England for use by Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

troops.

U.S. Senator from California (1850–1851)

On November 13, 1849, General Bennet C. Riley, without Washington approval, called for a state election to ratify the new California State constitution. On December 20, the California legislature voted to seat two senators to represent the state in the Senate. The front-runner was Frémont, a Free Soil Democrat, known for being a western hero, and regarded by many as an innocent victim of an unjustified court-martial. The other candidates were T. Butler King, a Whig, and William Gwin, a Democrat. Frémont won the first Senate seat, easily having 29 out of 41 votes and Gwin, having Southern backing, was elected to the second Senate seat, having won 24 out of 41 votes. By random draw of straws, Gwin won the longer Senate term while Frémont won the shorter Senate term.

In Washington, Frémont, whose California ranch had been purchased from a Mexican land grantee, supported an unsuccessful law that would have rubber-stamped Mexican land grants, and another law that prevented foreign workers from owning gold claims (Fremont's ranch was in gold country), derisively called "Frémont's Gold Bill". Frémont voted against harsh penalties for those who assisted runaway slaves and he was in favor of abolishing the slave trade in the District of Columbia.

Democratic pro-slavery opponents of Frémont, called the Chivs, strongly opposed Frémont's re-election, and endorsed Solomon Heydenfeldt. Rushing back to California hoping to thwart the Chivs, Frémont started his own election newspaper, the ''San Jose Daily Argus'', however, to no avail, he was unable to get enough votes for re-election to the Senate. Neither Heydenfeldt, nor Frémont's other second-time competitor King, were able to obtain a majority of votes, allowing Gwin to be California's lone senator. Frémont's term lasted 175 days from September 10, 1850, to March 3, 1851, and he only served 21 working days in Washington in the Senate. Pro-slavery John B. Weller, supported by the Chivs, was elected one year later to the empty Senate seat previously held by Frémont.

Fifth expedition (1853–1854)

In the fall of 1853, Frémont embarked on another expedition to identify a viable route for a transcontinental railroad along the 38th parallel. The party journeyed between Missouri and San Francisco, California, over a combination of known trails and unexplored terrain. A primary objective was to pass through the Rocky Mountains and Sierra Nevada Mountains during winter to document the amount of snow and the feasibility of winter rail passage along the route. His photographer ( daguerreotypist) was Solomon Nunes Carvalho.

Frémont followed the Santa Fe Trail, passing Bent's Fort before heading west and entering the San Luis Valley of Colorado in December. The party then followed the North Branch of the Old Spanish Trail, crossing the Continental Divide at Cochetopa Pass and continuing west into central Utah. But following the trail was made difficult by snow cover. On occasion, they were able to detect evidence of Captain John Gunnison's expedition, which had followed the North Branch just months before.

Weeks of snow and bitter cold took its toll and slowed progress. Nonessential equipment was abandoned and one man died before the struggling party reached the Mormon settlement of Parowan in southwestern Utah on February 8, 1854. After spending two weeks in Parowan to regain strength, the party continued across the Great Basin and entered the Owens Valley

Owens Valley ( Numic: ''Payahǖǖnadǖ'', meaning "place of flowing water") is an arid valley of the Owens River in eastern California in the United States. It is located to the east of the Sierra Nevada, west of the White Mountains and Iny ...

near present-day Big Pine, California. Frémont then journeyed south and crossed the Sierra Nevada Mountains and entered the Kern River

The Kern River, previously Rio de San Felipe, later La Porciuncula, is an Endangered, Wild and Scenic river in the U.S. state of California, approximately long. It drains an area of the southern Sierra Nevada mountains northeast of Bakersfield ...

drainage, which was followed west to the San Joaquin Valley

The San Joaquin Valley ( ; es, Valle de San Joaquín) is the area of the Central Valley of the U.S. state of California that lies south of the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta and is drained by the San Joaquin River. It comprises seven ...

.

Frémont arrived in San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17th ...

on April 16, 1854. Having completed a winter passage across the mountainous west, Frémont was optimistic that a railroad along the 38th Parallel was viable and that winter travel along the line would be possible through the Rocky Mountains.

Republican Party presidential candidate (1856)

In 1856, Frémont (age 43) was the first presidential candidate of the new Republican Party. The Republicans, whose party had formed in 1854, were united in their opposition to the Pierce Administration and the spread of slavery into the West. Initially, Frémont was asked to be the Democratic candidate by former Virginia Governor John B. Floyd

John Buchanan Floyd (June 1, 1806 – August 26, 1863) was the 31st Governor of Virginia, U.S. Secretary of War, and the Confederate general in the American Civil War who lost the crucial Battle of Fort Donelson.

Early family life

John Buch ...

and the powerful Preston family.Fugitive Slave Law

The fugitive slave laws were laws passed by the United States Congress in 1793 and 1850 to provide for the return of enslaved people who escaped from one state into another state or territory. The idea of the fugitive slave law was derived from ...

.[ Republican leaders ]Nathaniel P. Banks

Nathaniel Prentice (or Prentiss) Banks (January 30, 1816 – September 1, 1894) was an American politician from Massachusetts and a Union general during the Civil War. A millworker by background, Banks was prominent in local debating societies, ...

, Henry Wilson, and John Bigelow were able to get Frémont to join their political party.[ Seeking a united front and a fresh face for the party, the Republicans nominated Frémont for president over other candidates, and conservative William L. Dayton of New Jersey, for vice president, at their June 1856 convention held in Philadelphia. The Republican campaign used the slogan "Free Soil, Free Men, and Frémont" to crusade for free farms (homesteads) and against the Slave Power. Frémont, popularly known as ''The Pathfinder'', however, had voter appeal and remained the symbol of the Republican Party. The Democratic Party nominated James Buchanan.

] Frémont's wife Jessie, Bigelow, and Issac Sherman ran Frémont's campaign. As the daughter of a senator, Jessie had been raised in Washington, and she understood politics more than Frémont. Many treated Jessie as an equal political professional, while Frémont was treated as an amateur. She received popular attention much more than potential First Ladies, and Republicans celebrated her participation in the campaign calling her ''Our Jessie''. Jessie and the Republican propaganda machine ran a strong campaign, but she was unable to get her powerful father, Senator Benton, to support Frémont. While praising Frémont, Benton announced his support for Buchanan.

Frémont's wife Jessie, Bigelow, and Issac Sherman ran Frémont's campaign. As the daughter of a senator, Jessie had been raised in Washington, and she understood politics more than Frémont. Many treated Jessie as an equal political professional, while Frémont was treated as an amateur. She received popular attention much more than potential First Ladies, and Republicans celebrated her participation in the campaign calling her ''Our Jessie''. Jessie and the Republican propaganda machine ran a strong campaign, but she was unable to get her powerful father, Senator Benton, to support Frémont. While praising Frémont, Benton announced his support for Buchanan.[Allan Nevins, ''Ordeal of the Union: A House Dividing, 1852–1857'' (1947) pp. 496–502]

Frémont, along with the other presidential candidates, did not actively participate in the campaign, and he mostly stayed home at 56 West Street, in New York City. This practice was typical in presidential campaigns of the 19th century. To win the presidency, the Republicans concentrated on four swing states, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Indiana, and Illinois. Republican luminaries were sent out decrying the Democratic Party's attachment to slavery and its support of the repeal of the Missouri Compromise. The experienced Democrats, knowing the Republican strategy, also targeted these states, running a rough media campaign, while illegally naturalizing thousands of alien immigrants in Pennsylvania. The campaign was particularly abusive, as the Democrats attacked Frémont's illegitimate birth and alleged Frémont was Catholic.[ In a counter-crusade against the Republicans, the Democrats ridiculed Frémont's military record and warned that his victory would bring civil war. Much of the private rhetoric of the campaign focused on unfounded rumors regarding Frémont – talk of him as president taking charge of a large army that would support slave insurrections, the likelihood of widespread lynchings of slaves, and whispered hope among slaves for freedom and political equality.]Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853; he was the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. A former member of the U.S. House of Represen ...

ran as a third-party candidate representing the American (Know Nothing) Party. The popular vote went to Buchanan who received 1,836,072 votes to 1,342,345 votes received by Frémont on November 4, 1856.[ Fremont carried 11 states, and Buchanan carried 19. The Democrats were better organized while the Republicans had to operate on limited funding. After the campaign, Frémont returned to California and devoted himself to his mining business on the Mariposa gold estate, estimated by some to be valued at ten million dollars.][ Frémont's title to Mariposa land had been confirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1856.][

]

American Civil War

At the start of the

At the start of the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, Frémont was touring Europe in an attempt to find financial backers in his California ''Las Mariposas'' estate ranch. President Abraham Lincoln wanted to appoint Frémont as the American minister to France, thereby taking advantage of his French ancestry and the popularity in Europe of his anti-slavery positions. However Secretary of State William Henry Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senator. A determined oppon ...

objected to Frémont's radicalism, and the appointment was not made. Instead, Lincoln appointed Frémont Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union of the collective states. It proved essential to th ...

Major General on May 15, 1861. He arrived in Boston from England on June 27, 1861, and Lincoln promoted him commander of the Department of the West on July 1, 1861. The Western department included the area west of the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. They ...

to the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it fl ...

. After Frémont arrived in Washington, D.C., he conferred with Lincoln and Commanding General Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

, himself making a plan to clear all Confederates out of Missouri and to make a general campaign down the Mississippi and advance on Memphis. According to Frémont, Lincoln had given him ''carte blanche

A blank cheque in the literal sense is a cheque that has no monetary value written in, but is already signed. In the figurative sense, it is used to describe a situation in which an agreement has been made that is open-ended or vague, and therefo ...

'' authority on how to conduct his campaign and to use his own judgement, while talking on the steps of the White House portico. Frémont's main goal as commander of the Western Armies was to protect Cairo, Illinois, at all costs in order for the Union Army to move southward on the Mississippi River.[ Catton, p. 27.] Both Frémont and his subordinate, General John Pope, believed that Ulysses S. Grant was the fighting general needed to secure Missouri from the Confederates. Frémont had to contend with a hard-driving Union General Nathaniel Lyon

Nathaniel Lyon (July 14, 1818 – August 10, 1861) was the first Union general to be killed in the American Civil War. He is noted for his actions in Missouri in 1861, at the beginning of the conflict, to forestall secret secessionist plans of th ...

, whose irregular war policy disturbed the complex loyalties of Missouri.[ Catton, p. 11.]

Department of the West (1861)

Command and duties

On July 25, 1861, Frémont arrived in St. Louis and formally took command of a Department of the West that was in crisis.Smith

Smith may refer to:

People

* Metalsmith, or simply smith, a craftsman fashioning tools or works of art out of various metals

* Smith (given name)

* Smith (surname), a family name originating in England, Scotland and Ireland

** List of people wi ...

, Jean Edward Smith, ''Grant'' (2001) p. 115.[ Catton, p. 10.] Frémont had to organize an army in a slave state that was largely disloyal, having a limited number of Union soldiers, supplies, and arms. Guerilla warfare was breaking out and two Confederate armies were planning on capturing Springfield and invading Illinois to capture Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the Capital city, capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, List of ...

. Frémont's duties upon taking command of the Western Department were broad, his resources were limited, and the secession crisis in Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

appeared to be uncontrollable.[ Frémont was responsible for safeguarding Missouri and all of the Northwest.][ Catton, pp. 11–12.] Frémont's mission was to organize, equip, and lead the Union Army down the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it fl ...

, reopen commerce, and break off the Western part of the Confederacy.[ Catton, p. 12.] Frémont was given only 23,000 men, whose volunteer 3-month enlistments were about to expire.[ Western Governors sent more troops to Frémont, but he did not have any weapons with which to arm them. There were no uniforms or military equipment either, and the soldiers were subject to food rationing, poor transportation, and lack of pay.][ Fremont's intelligence was also faulty, leading him to believe the Missouri state militia and the Confederate forces were twice as numerous as they actually were.][

]

Blair feud and corruption charges

Frémont's arrival brought an aristocratic air that raised eyebrows and general disapproval among the people of St. Louis. Soon after he came into command, Frémont became involved in a political feud with Frank Blair, who was a member of the powerful Blair family and brother of Lincoln's cabinet member. To gain control of Missouri politics, Blair complained to Washington that Frémont was "extravagant" and that his command was brimming with a "horde of pirates", who were defrauding the army. This caused Lincoln to send Adjutant General

Frémont's arrival brought an aristocratic air that raised eyebrows and general disapproval among the people of St. Louis. Soon after he came into command, Frémont became involved in a political feud with Frank Blair, who was a member of the powerful Blair family and brother of Lincoln's cabinet member. To gain control of Missouri politics, Blair complained to Washington that Frémont was "extravagant" and that his command was brimming with a "horde of pirates", who were defrauding the army. This caused Lincoln to send Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas

Lorenzo Thomas (October 26, 1804 – March 2, 1875) was a career United States Army officer who was Adjutant General of the Army at the beginning of the American Civil War. After the war, he was appointed temporary Secretary of War by U.S. ...

to check in on Frémont, who reported that Frémont was incompetent and had made questionable army purchases.

The imbroglio became a national scandal, and Frémont was unable to keep a handle on supply affairs. A Congressional subcommittee investigation headed by Elihu B. Washburne and a later Commission on War Claims investigation into the entire Western Department confirmed that many of Blair's charges were true.[