John Buford on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

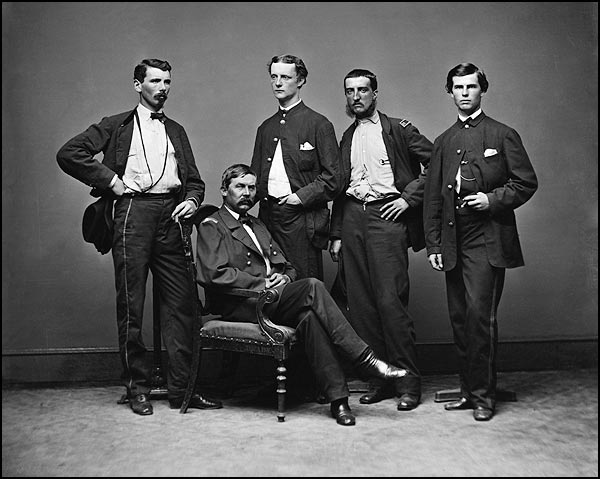

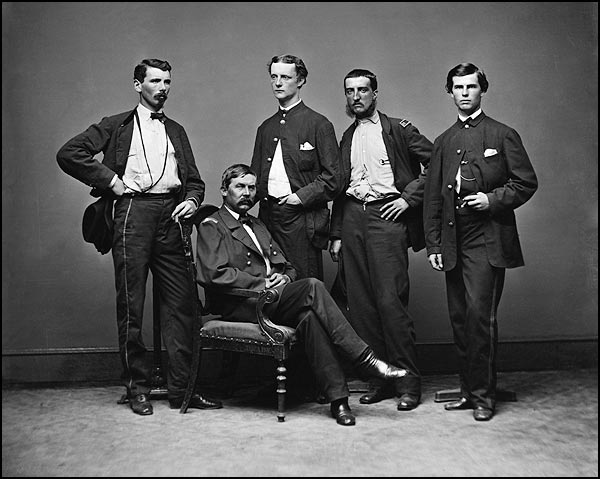

John Buford, Jr. (March 4, 1826 – December 16, 1863) was a

After the

After the

''Biographical Sketches of Distinguished Officers of the Army and Navy''

New York: L. R. Hamersly, 1905. . * Hard, Abner N. ''History of the Eighth Cavalry Regiment, Illinois Volunteers''. Dayton, OH: Press of Morningside Bookshop, 1984. . First published 1868 by author. * Langellier, John P., Kurt Hamilton Cox, and Brian C. Pohanka. ''Myles Keogh: The Life and Legend of an "Irish Dragoon" in the Seventh Cavalry''. El Segundo, CA: Upton and Sons, 1991. . * Longacre, Edward G. ''General John Buford: A Military Biography''. Conshohocken, PA: Combined Publishing, 1995. . * Moore, Frank

''The Civil War In Song and Story, 1860–1865''

P. F. Colliers, 1889. . * Petruzzi, J. David. "John Buford: By the Book." ''America's Civil War Magazine'', July 2005. * Petruzzi, J. David. "Opening the Ball at Gettysburg: The Shot That Rang for Fifty Years." ''America's Civil War Magazine'', July 2006. * Petruzzi, J. David. "The Fleeting Fame of Alfred Pleasonton." ''America's Civil War Magazine'', March 2005. * Phipps, Michael, and John S. Peterson. ''The Devil's to Pay''. Gettysburg, PA: Farnsworth Military Impressions, 1995. . * Rodenbough, Theophilus

''From Everglade to Cañon with the Second Dragoons: An Authentic Account of Service in Florida, Mexico, Virginia, and the Indian Country''

New York: D. Von Nostrand, 1875. . * Sanford, George B. ''Fighting Rebels and Redskins: Experiences in Army Life of Colonel George B. Sanford, 1861–1892''. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1969. . * ''Proceedings of the Buford Memorial Association'' (New York, 1895) * ''History of the Civil War in America'' (volume iii, p. 545) :

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry in ...

officer. He fought for the Union as a brigadier general during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. Buford is best known for having played a major role in the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the ...

on July 1, 1863, by identifying, taking, and holding the "high ground" while in command of a division.

Buford graduated from West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

in 1848. He remained loyal to the United States when the Civil War broke out, despite having been born in the divided border state of Kentucky. During the war he fought against the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most oft ...

as part of the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confede ...

. His first command was a cavalry brigade under Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

John Pope, and he distinguished himself at Second Bull Run in August 1862, where he was wounded, and also saw action at Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union G ...

in September and Stoneman's Raid in spring 1863.

Buford's cavalry division played a crucial role in the Gettysburg Campaign that summer. Arriving at the small town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

Gettysburg (; non-locally ) is a borough and the county seat of Adams County in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. The Battle of Gettysburg (1863) and President Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address are named for this town.

Gettysburg is home to ...

, on June 30, before the Confederate troops, Buford set up defensive positions. On the morning of July 1, Buford's division was attacked by a Confederate division under the command of Major General Henry Heth. His men held just long enough for Union reinforcements to arrive. After a massive three-day battle, the Union troops emerged victorious. Later, Buford rendered valuable service to the Army, both in the pursuit of Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of Nor ...

after the Battle of Gettysburg, and in the Bristoe Campaign that autumn, but his health started to fail, possibly from typhoid. Just before his death at age 37, he received a personal message from President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

, promoting him to major general of volunteers in recognition of his tactical skill and leadership displayed on the first day of Gettysburg.

Early years

Buford was born inWoodford County, Kentucky

Woodford County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of the 2020 census, the population was 26,871. Its county seat is Versailles. The area was home to Pisgah Academy. Woodford County is part of the Lexington-Fayette, KY Metro ...

, but was raised in Rock Island, Illinois

Rock Island is a city in and the county seat of Rock Island County, Illinois, United States. The original Rock Island, from which the city name is derived, is now called Arsenal Island. The population was 37,108 at the 2020 census. Located on t ...

, from the age of eight. John, his father, was a prominent Democratic politician in Illinois and a political opponent of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

. Buford was of English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

descent. His family had a long military tradition. John Jr.'s grandfather, Simeon Buford, served in the cavalry during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

under Henry "Lighthorse" Lee, the father of Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of Nor ...

. His great-uncle, Colonel Abraham Buford (of the Waxhaw Massacre

The Waxhaw massacre, (also known as the Waxhaws, Battle of Waxhaw, and Buford's massacre) took place during the American Revolutionary War on May 29, 1780, near Lancaster, South Carolina, between a Continental Army force led by Abraham Buford and ...

), also served in a Virginia regiment. His half-brother, Napoleon Bonaparte Buford, would become a major general in the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

, while his cousin, Abraham Buford, would become a cavalry brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

in the Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

.

After attending Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois

Galesburg is a city in Knox County, Illinois, United States. The city is northwest of Peoria. At the 2010 census, its population was 32,195. It is the county seat of Knox County and the principal city of the Galesburg Micropolitan Statistic ...

, for one year, Buford was accepted into the Class of 1848 at the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

(West Point). Upperclassmen during Buford's time at West Point included Fitz-John Porter

Fitz John Porter (August 31, 1822 – May 21, 1901) (sometimes written FitzJohn Porter or Fitz-John Porter) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general during the American Civil War. He is most known for his performance at the ...

(Class of 1845), George B. McClellan (1846), Thomas J. Jackson (1846), George Pickett (1846), and two future commanders and friends, George Stoneman (1846) and Ambrose Burnside

Ambrose Everett Burnside (May 23, 1824 – September 13, 1881) was an American army officer and politician who became a senior Union general in the Civil War and three times Governor of Rhode Island, as well as being a successful inventor ...

(1847). The Class of 1847 also included A.P. Hill and Henry Heth, two men Buford would face at Gettysburg on the morning of July 1, 1863.

Buford graduated 16th of 38 cadets and was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army unt ...

in the 1st U.S. Dragoons

The 1st Cavalry Regiment is a United States Army regiment that has its antecedents in the early 19th century in the formation of the United States Regiment of Dragoons. To this day, the unit's special designation is "First Regiment of Dragoon ...

, transferring the next year to the 2nd U.S. Dragoons.Eicher, ''Longest Night'', p. 153. He served in Texas and against the Sioux

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin (; Dakota: /otʃʰeːtʰi ʃakoːwĩ/) are groups of Native American tribes and First Nations peoples in North America. The modern Sioux consist of two major divisions based on language divisions: the Dakota and ...

, served on peacekeeping duty in Bleeding Kansas

Bleeding Kansas, Bloody Kansas, or the Border War was a series of violent civil confrontations in Kansas Territory, and to a lesser extent in western Missouri, between 1854 and 1859. It emerged from a political and ideological debate over the ...

, and in the Utah War

The Utah War (1857–1858), also known as the Utah Expedition, Utah Campaign, Buchanan's Blunder, the Mormon War, or the Mormon Rebellion was an armed confrontation between Mormon settlers in the Utah Territory and the armed forces of the US go ...

in 1858. He was stationed at Fort Crittenden, Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to its ...

, from 1859 to 1861. He studied the works of General John Watts de Peyster

John Watts de Peyster, Sr. (March 9, 1821 – May 4, 1907) was an American author on the art of war, philanthropist, and the Adjutant General of New York.Allaben, p. 205 He served in the New York State Militia during the Mexican–American War an ...

, who urged that the skirmish line become the new line of battle.

Civil War

Throughout 1860, Buford and his fellow soldiers had lived with talk ofsecession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics l ...

and the possibility of civil war until the Pony Express

The Pony Express was an American express mail service that used relays of horse-mounted riders. It operated from April 3, 1860, to October 26, 1861, between Missouri and California. It was operated by the Central Overland California and Pike ...

brought word that Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a sea fort built on an artificial island protecting Charleston, South Carolina from naval invasion. Its origin dates to the War of 1812 when the British invaded Washington by sea. It was still incomplete in 1861 when the Battle ...

had been fired upon in April 1861, confirming secession as fact. As was the case with many West Pointers, Buford had to choose between North and South. Based on his background, Buford had ample reason to join the Confederacy. He was a native Kentuckian, the son of a slave-owning father, and the husband of a woman whose relatives would fight for the South, as would a number of his own. On the other hand, Buford had been educated in the North and come to maturity within the Army. His two most influential professional role models, Colonels William S. Harney and Philip St. George Cooke, were Southerners who elected to remain with the Union and the U.S. Army. He loved his profession and his time on the frontier had snapped the ties that drew other Southerners home.

John Gibbon

John Gibbon (April 20, 1827 – February 6, 1896) was a career United States Army officer who fought in the American Civil War and the Indian Wars.

Early life

Gibbon was born in the Holmesburg section of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the four ...

, a North Carolinian facing the same dilemma, recalled in a post-war memoir the evening that John Buford committed himself to the Union:

In November 1861, Buford was appointed Assistant Inspector General with the rank of major, and, in July 1862, after having served for several months in the defense of Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

, was raised to the rank of brigadier general of volunteers. In 1862, he was given his first position, under Major General John Pope, as commander of the II Corps 2nd Corps, Second Corps, or II Corps may refer to:

France

* 2nd Army Corps (France)

* II Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* II Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French ...

Cavalry Brigade of the Union Army of Virginia, which fought with distinction at the Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confedera ...

. Buford personally led a charge late in the battle, but was wounded in the knee by a spent bullet. The injury was painful, but not serious, although some Union newspapers reported that he had been killed.Bielakowski, p. 310. He returned to active service, and served as chief of cavalry to Major Generals George B. McClellan and Ambrose E. Burnside

Ambrose Everett Burnside (May 23, 1824 – September 13, 1881) was an American army officer and politician who became a senior Union general in the Civil War and three times Governor of Rhode Island, as well as being a successful inventor ...

in the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confede ...

. Unfortunately, this assignment was nothing more than a staff position, and he chafed for a field command. In McClellan's Maryland Campaign, Buford was in the battles of South Mountain South Mountain or South Mountains may refer to:

Canada

* South Mountain, a village in North Dundas, Ontario

* South Mountain (Nova Scotia), a mountain range

* South Mountain (band), a Canadian country music group

United States

Landforms

* Sout ...

and Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union G ...

, replacing Brigadier General George Stoneman on McClellan's staff. Under Major General Joseph Hooker in 1863, however, Buford was given the Reserve Brigade of regular cavalry in the 1st Division, Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac.

After the

After the Battle of Chancellorsville

The Battle of Chancellorsville, April 30 – May 6, 1863, was a major battle of the American Civil War (1861–1865), and the principal engagement of the Chancellorsville campaign.

Chancellorsville is known as Lee's "perfect battle" because h ...

, Major General Alfred Pleasonton was given command of the Cavalry Corps, although Hooker later agreed that Buford would have been the better choice. Buford first led his new division at the Battle of Brandy Station, which was virtually an all-cavalry engagement, and then again at the Battle of Upperville.

In the Gettysburg Campaign, Buford, who had been promoted to command of the 1st Division, is credited with selecting the field of battle at Gettysburg. On June 30, Buford's command rode into the small town of Gettysburg. Very soon, Buford realized that he was facing a superior force of rebels to his front and set about creating a defense against the Confederate advance. He was acutely aware of the tactical importance of holding the high ground south of Gettysburg, and so he did, beginning one of the most important battles in American military history. His skillful defensive troop dispositions, coupled with the bravery and tenacity of his dismounted men, allowed the I Corps I Corps, 1st Corps, or First Corps may refer to:

France

* 1st Army Corps (France)

* I Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* I Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Ar ...

, under Major General John F. Reynolds, time to come up in support and thus maintain a Union foothold in tactically important positions. Despite Lee's barrage attack of 140 cannons and a final infantry attack on the third day of the battle, the Union army won a strategic victory. The importance of Buford's leadership and tactical foresight on July 1 cannot be overstated in its contribution to this victory. Afterward, Buford's troopers were sent by Pleasonton to Emmitsburg, Maryland

Emmitsburg is a town in Frederick County, Maryland, United States, south of the Mason-Dixon line separating Maryland from Pennsylvania. Founded in 1785, Emmitsburg is the home of Mount St. Mary's University. The town has two Catholic pilgrim ...

, to resupply and refit, an ill-advised decision that uncovered the Union left flank.

In the Retreat from Gettysburg, Buford pursued the Confederates to Warrenton, Virginia

Warrenton is a town in Fauquier County, Virginia, of which it is the seat of government. The population was 9,611 at the 2010 census, up from 6,670 at the 2000 census. The estimated population in 2019 was 10,027. It is at the junction of U.S. R ...

, and was afterward engaged in many operations in central Virginia, rendering particularly valuable service in covering Major General George Meade

George Gordon Meade (December 31, 1815 – November 6, 1872) was a United States Army officer and civil engineer best known for decisively defeating Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Gettysburg in the American Civil War. H ...

's retrograde movement in the October 1863 Bristoe Campaign.

Death and legacy

By mid-December, it was obvious that Buford was sick, possibly from contractingtyphoid

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by ''Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several d ...

, and he took respite at the Washington home of his good friend, General George Stoneman. On December 16, Stoneman initiated the proposal that Buford be promoted to major general, and President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

assented, writing as follows: "I am informed that General Buford will not survive the day. It suggests itself to me that he will be made Major General for distinguished and meritorious service at the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the ...

." Informed of the promotion, Buford inquired doubtfully, "Does he mean it?" When assured the promotion was genuine, he replied simply, "It is too late, now I wish I could live."Sanford, np.

In the last hours, Buford was attended by his aide, Captain Myles Keogh, and by Edward, his black servant. Also present were Lieutenant Colonel A. J. Alexander and General Stoneman. His wife Pattie was traveling from Rock Island, Illinois, but would not arrive in time. Near the end, he became delirious and began admonishing Edward, but then, in a moment of clarity, called for the man and apologized: "Edward, I hear that I have been scolding you. I did not know what I was doing. You have been a faithful servant, Edward."

John Buford died at 2 p.m., December 16, 1863, while Myles Keogh held him in his arms. His final reported words were "Put guards on all the roads, and don't let the men run to the rear."Moore, np.

On December 20, memorial services were held at the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church, a church on the corner of H. Street and New York Avenue in Washington, D.C. President Lincoln was among the mourners. Buford's wife was unable to attend due to illness. The pallbearers included Generals Casey, Heintzelman, Sickles, Schofield, Hancock Hancock may refer to:

Places in the United States

* Hancock, Iowa

* Hancock, Maine

* Hancock, Maryland

* Hancock, Massachusetts

* Hancock, Michigan

* Hancock, Minnesota

* Hancock, Missouri

* Hancock, New Hampshire

** Hancock (CDP), New Hampshir ...

, Doubleday, and Warren. General Stoneman commanded the escort in a procession that included "Grey Eagle," Buford's old white horse that he rode at Gettysburg.

After the service, two of Buford's staff, Captains Keogh and Wadsworth, escorted his body to West Point, where it was buried alongside fellow Gettysburg hero Lieutenant Alonzo Cushing

Alonzo Hereford Cushing (January 19, 1841 – July 3, 1863) was an artillery officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He was killed in action during the Battle of Gettysburg while defending the Union position on Cemetery Ridge aga ...

, who had died defending the "high ground" (Cemetery Ridge

Cemetery Ridge is a geographic feature in Gettysburg National Military Park, south of the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, that figured prominently in the Battle of Gettysburg, July 1 to July 3, 1863. It formed a primary defensive position for the ...

) that Buford had chosen. In 1865, a 25-foot obelisk style monument was erected over his grave, financed by members of his old division. The officers of his staff published a resolution that set forth the esteem in which he was held by those in his command:

In 1866, a military fort established on the Missouri-Yellowstone confluence in what is now North Dakota

North Dakota () is a U.S. state in the Upper Midwest, named after the indigenous Dakota Sioux. North Dakota is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba to the north and by the U.S. states of Minnesota to the east, ...

, was named Fort Buford after the general. The community of Buford, Wyoming

Buford is an unincorporated ghost town in Albany County, Wyoming, United States. It is located between Laramie and Cheyenne on Interstate 80. Its last resident, who had been the lone resident for nearly two decades, left in 2012.

Location

Bufor ...

, was renamed in the general's honor. It was sold at auction for $900,000 on April 5, 2012 to an unnamed Vietnamese by its owner, who had served in the U.S. military in 1968–1969.

In 1895, a bronze statue of Buford designed by artist James E. Kelly was dedicated on the Gettysburg Battlefield

The Gettysburg Battlefield is the area of the July 1–3, 1863, military engagements of the Battle of Gettysburg within and around the borough of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Locations of military engagements extend from the site of the first sho ...

.

The M8 Armored Gun System

The M8 Armored Gun System (AGS), sometimes known as the Buford, is an American light tank that was intended to replace the M551 Sheridan and TOW missile-armed Humvees in the 82nd Airborne Division and 2nd Armored Cavalry Regiment (2nd ACR) of ...

, an American light tank canceled in 1996, is sometimes referred to as the "Buford" in his honor.

In popular media

Buford was portrayed by Sam Elliott in the 1993 film '' Gettysburg'', based on Michael Shaara's novel ''The Killer Angels

''The Killer Angels'' is a 1974 historical novel by Michael Shaara that was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1975. The book depicts the three days of the Battle of Gettysburg during the American Civil War, and the days leading up to it ...

''.

Buford is a character in the alternate history

Alternate history (also alternative history, althist, AH) is a genre of speculative fiction of stories in which one or more historical events occur and are resolved differently than in real life. As conjecture based upon historical fact, alte ...

novel '' Gettysburg: A Novel of the Civil War'', written by Newt Gingrich

Newton Leroy Gingrich (; né McPherson; born June 17, 1943) is an American politician and author who served as the 50th speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1995 to 1999. A member of the Republican Party, he was the U. ...

and William Forstchen

William R. Forstchen (born October 11, 1950) is an American historian and author. A Professor of History and Faculty Fellow at Montreat College, in Montreat, North Carolina, he received his doctorate from Purdue University.

He has published num ...

.

See also

*List of American Civil War generals (Union)

Union generals

__NOTOC__

The following lists show the names, substantive ranks, and brevet ranks (if applicable) of all general officers who served in the United States Army during the Civil War, in addition to a small selection of lower-rank ...

Notes

References

* Bielakowski, Alexander M. "John Buford." In ''Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History'', edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. . * Eicher, David J. ''The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. . * Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. ''Civil War High Commands''. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. . * Hamersly, Lewis Randolph''Biographical Sketches of Distinguished Officers of the Army and Navy''

New York: L. R. Hamersly, 1905. . * Hard, Abner N. ''History of the Eighth Cavalry Regiment, Illinois Volunteers''. Dayton, OH: Press of Morningside Bookshop, 1984. . First published 1868 by author. * Langellier, John P., Kurt Hamilton Cox, and Brian C. Pohanka. ''Myles Keogh: The Life and Legend of an "Irish Dragoon" in the Seventh Cavalry''. El Segundo, CA: Upton and Sons, 1991. . * Longacre, Edward G. ''General John Buford: A Military Biography''. Conshohocken, PA: Combined Publishing, 1995. . * Moore, Frank

''The Civil War In Song and Story, 1860–1865''

P. F. Colliers, 1889. . * Petruzzi, J. David. "John Buford: By the Book." ''America's Civil War Magazine'', July 2005. * Petruzzi, J. David. "Opening the Ball at Gettysburg: The Shot That Rang for Fifty Years." ''America's Civil War Magazine'', July 2006. * Petruzzi, J. David. "The Fleeting Fame of Alfred Pleasonton." ''America's Civil War Magazine'', March 2005. * Phipps, Michael, and John S. Peterson. ''The Devil's to Pay''. Gettysburg, PA: Farnsworth Military Impressions, 1995. . * Rodenbough, Theophilus

''From Everglade to Cañon with the Second Dragoons: An Authentic Account of Service in Florida, Mexico, Virginia, and the Indian Country''

New York: D. Von Nostrand, 1875. . * Sanford, George B. ''Fighting Rebels and Redskins: Experiences in Army Life of Colonel George B. Sanford, 1861–1892''. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1969. . * ''Proceedings of the Buford Memorial Association'' (New York, 1895) * ''History of the Civil War in America'' (volume iii, p. 545) :

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Buford, John 1826 births 1863 deaths People from Woodford County, Kentucky American people of English descent Knox College (Illinois) alumni People of Illinois in the American Civil War People of Kentucky in the American Civil War People from Rock Island, Illinois Cavalry commanders Union Army generals United States Military Academy alumni Burials at West Point Cemetery Deaths from typhoid fever