John Adair on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

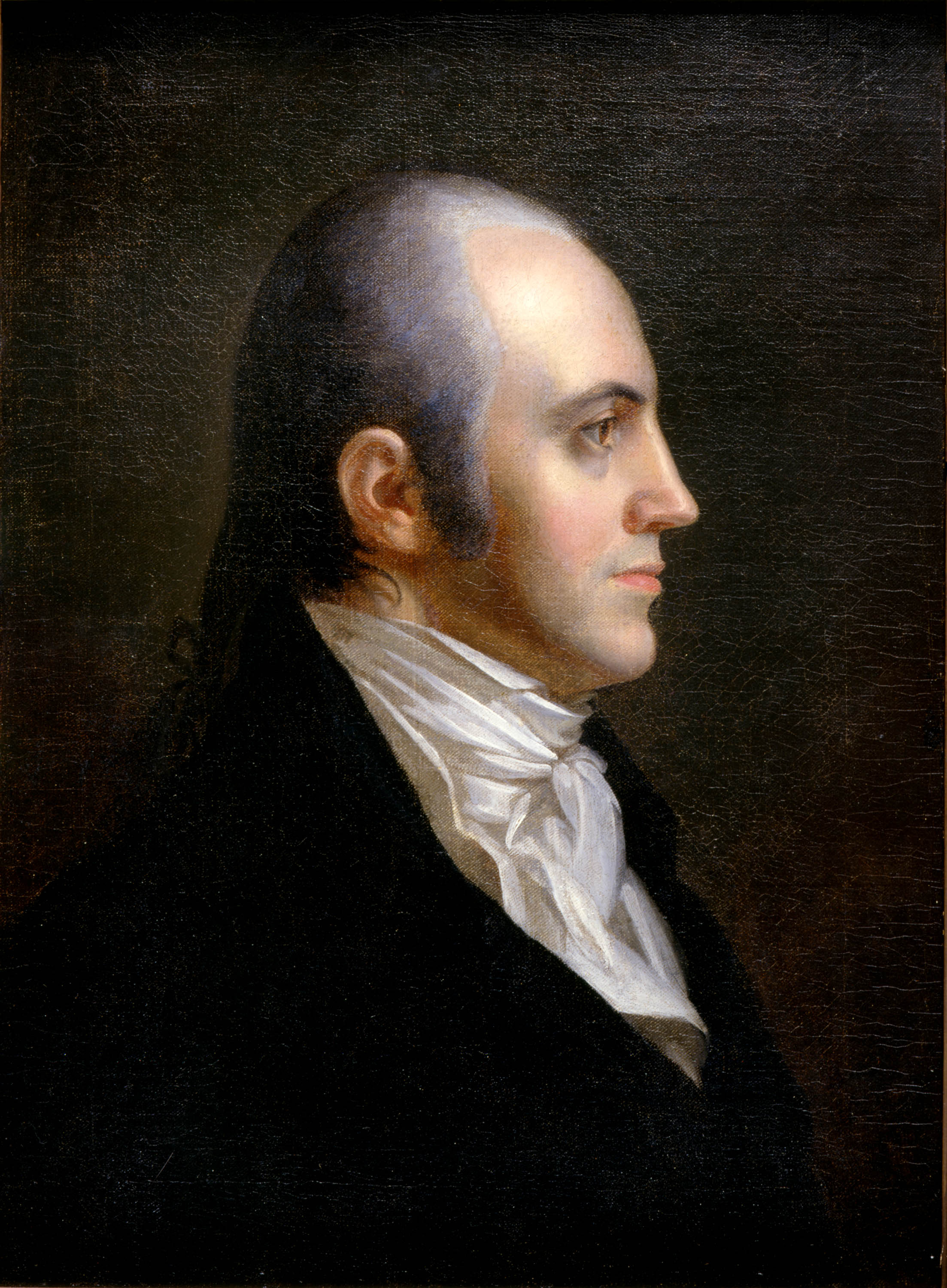

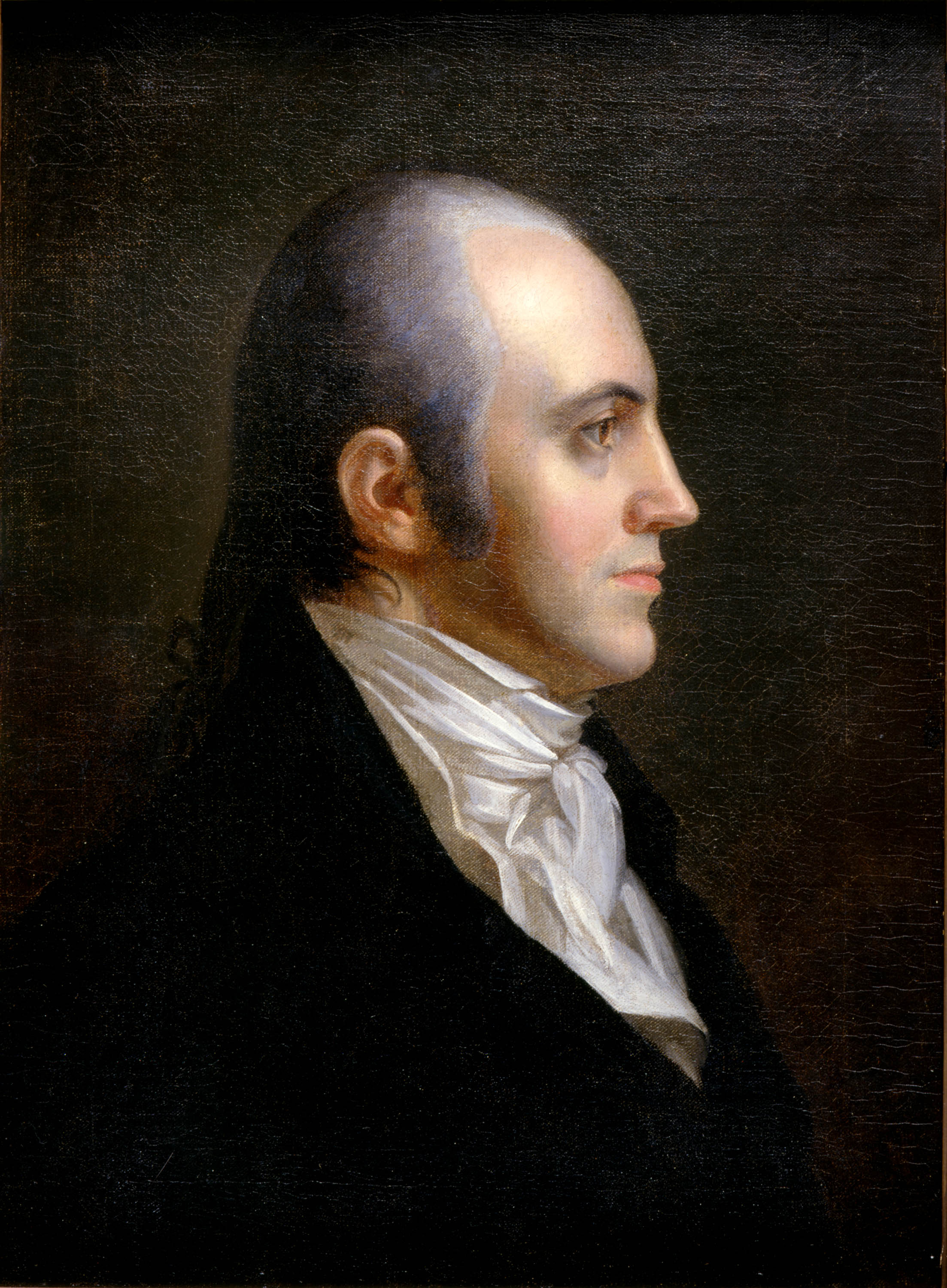

John Adair (January 9, 1757 – May 19, 1840) was an American pioneer, slave trader, soldier, and politician. He was the eighth

Popular for his military service, Adair was chosen as a delegate to the Kentucky constitutional convention in 1792.Harrison in ''The Kentucky Encyclopedia'', p. 2 Upon the state's admission to the Union, he was elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives, serving from 1793 to 1795. He remained active in the Kentucky militia, and on February 25, 1797, he was promoted to

Popular for his military service, Adair was chosen as a delegate to the Kentucky constitutional convention in 1792.Harrison in ''The Kentucky Encyclopedia'', p. 2 Upon the state's admission to the Union, he was elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives, serving from 1793 to 1795. He remained active in the Kentucky militia, and on February 25, 1797, he was promoted to

Convinced of his innocence, Henry Clay represented Burr, while

Convinced of his innocence, Henry Clay represented Burr, while

Adair rejoined the Kentucky militia at the outset of the

Adair rejoined the Kentucky militia at the outset of the

Jackson approved the court's findings, but they were not the full refutation of Jackson's report that many Kentuckians —including Adair —had wanted. In a letter that was quickly made public, Adair —formerly one of Jackson's close friends —insisted that Jackson withdraw or modify his official report, but Jackson refused. This ended the matter until June 1815 when H. P. Helm, secretary to John Thomas, forwarded to a Frankfort newspaper remarks from "the general" that had been annexed to the official report. "The remarks" stated that the general was now convinced that the initial reports of cowardice by Davis's men "had been misrepresented" and that their retreat had been "not only excusable, but absolutely justifiable." The remarks, popularly believed to be from Jackson in response to Adair's letter, were subsequently reprinted across Kentucky. The "general" referenced was in fact General John Thomas; Jackson had never seen them. Helm claimed he sent a subsequent correction to the newspaper that published the remarks, but it was never printed.

Jackson did not discover the remarks until they were published again in January 1817 in response to a Boston newspaper's criticism of Kentucky militiamen.Gillig, p. 186 He wrote to the ''Kentucky Reporter'' at that time, denouncing the remarks as a forgery. The ''Reporter'' investigated and published an explanation of how Thomas's remarks had been attributed to Jackson. They did not reprint Jackson's letter because they felt his claim that the remarks had been intentionally forged —a charge which was now found to be false —was too inflammatory. The editors promised that if their retraction did not satisfy Jackson, they would fully publish any of his additional remarks on the subject. In Jackson's April 1817 response, he implied that Adair had intentionally misrepresented the remarks, and reasserted that they had been forged, possibly by Adair himself. Adair believed Jackson's references to the remarks as a "forged dish, dressed in the true Spanish style" was a thinly veiled reference to Adair's alleged participation in the Burr conspiracy.Gillig, p. 191 As ostensible proof that he was not predisposed against Kentuckians, Jackson also implied that he had not reported additional dishonorable behavior by Kentucky militiamen during the battle.Gillig, p. 189 This letter thrust the dispute into the national spotlight and prompted Adair to resume correspondence with him both to defend Davis's men and refute Jackson's charges of conspiracy.Gillig, p. 190 In his May 1817 response, he reasserted his defense of the Kentucky militiamen at New Orleans and dismissed many of Jackson's allegations as unimportant and untrue. He flatly denied the existence of a conspiracy, and chastised Jackson for making charges without supporting evidence.Gillig, p. 192 Responding to Jackson's allusion to Spain, Adair recalled that Jackson had also been implicated with Burr.

Unable to provide tangible evidence of Adair's alleged misdeeds, Jackson provided indirect evidence that a conspiracy was possible. His response, delayed by his treaty negotiations with the

Jackson approved the court's findings, but they were not the full refutation of Jackson's report that many Kentuckians —including Adair —had wanted. In a letter that was quickly made public, Adair —formerly one of Jackson's close friends —insisted that Jackson withdraw or modify his official report, but Jackson refused. This ended the matter until June 1815 when H. P. Helm, secretary to John Thomas, forwarded to a Frankfort newspaper remarks from "the general" that had been annexed to the official report. "The remarks" stated that the general was now convinced that the initial reports of cowardice by Davis's men "had been misrepresented" and that their retreat had been "not only excusable, but absolutely justifiable." The remarks, popularly believed to be from Jackson in response to Adair's letter, were subsequently reprinted across Kentucky. The "general" referenced was in fact General John Thomas; Jackson had never seen them. Helm claimed he sent a subsequent correction to the newspaper that published the remarks, but it was never printed.

Jackson did not discover the remarks until they were published again in January 1817 in response to a Boston newspaper's criticism of Kentucky militiamen.Gillig, p. 186 He wrote to the ''Kentucky Reporter'' at that time, denouncing the remarks as a forgery. The ''Reporter'' investigated and published an explanation of how Thomas's remarks had been attributed to Jackson. They did not reprint Jackson's letter because they felt his claim that the remarks had been intentionally forged —a charge which was now found to be false —was too inflammatory. The editors promised that if their retraction did not satisfy Jackson, they would fully publish any of his additional remarks on the subject. In Jackson's April 1817 response, he implied that Adair had intentionally misrepresented the remarks, and reasserted that they had been forged, possibly by Adair himself. Adair believed Jackson's references to the remarks as a "forged dish, dressed in the true Spanish style" was a thinly veiled reference to Adair's alleged participation in the Burr conspiracy.Gillig, p. 191 As ostensible proof that he was not predisposed against Kentuckians, Jackson also implied that he had not reported additional dishonorable behavior by Kentucky militiamen during the battle.Gillig, p. 189 This letter thrust the dispute into the national spotlight and prompted Adair to resume correspondence with him both to defend Davis's men and refute Jackson's charges of conspiracy.Gillig, p. 190 In his May 1817 response, he reasserted his defense of the Kentucky militiamen at New Orleans and dismissed many of Jackson's allegations as unimportant and untrue. He flatly denied the existence of a conspiracy, and chastised Jackson for making charges without supporting evidence.Gillig, p. 192 Responding to Jackson's allusion to Spain, Adair recalled that Jackson had also been implicated with Burr.

Unable to provide tangible evidence of Adair's alleged misdeeds, Jackson provided indirect evidence that a conspiracy was possible. His response, delayed by his treaty negotiations with the

Adair's participation in the War of 1812 and subsequent correspondence with Jackson restored his reputation. He continued to serve as adjutant general until 1817, when the voters returned him to the state House of Representatives. He was nominated for Speaker of the House during that term, and, although he was not elected, he drew support from members of both parties, largely because of his correspondence with Jackson.Gillig, p. 180

In the aftermath of the

Adair's participation in the War of 1812 and subsequent correspondence with Jackson restored his reputation. He continued to serve as adjutant general until 1817, when the voters returned him to the state House of Representatives. He was nominated for Speaker of the House during that term, and, although he was not elected, he drew support from members of both parties, largely because of his correspondence with Jackson.Gillig, p. 180

In the aftermath of the

Adair's

Adair's

Governor of Kentucky

The governor of the Commonwealth of Kentucky is the head of government of Kentucky. Sixty-two men and one woman have served as governor of Kentucky. The governor's term is four years in length; since 1992, incumbents have been able to seek re-el ...

and represented the state in both the U.S. House

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

and Senate. A native of South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, Adair enlisted in the state militia and served in the Revolutionary War, during which he was twice captured and held as a prisoner of war by the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

. Following the War, he was elected as a delegate to South Carolina's convention to ratify the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven ar ...

.

After moving to Kentucky in 1786, Adair participated in the Northwest Indian War, including a skirmish with the Miami

Miami ( ), officially the City of Miami, known as "the 305", "The Magic City", and "Gateway to the Americas", is a East Coast of the United States, coastal metropolis and the County seat, county seat of Miami-Dade County, Florida, Miami-Dade C ...

Chief Little Turtle

Little Turtle ( mia, Mihšihkinaahkwa) (1747 July 14, 1812) was a Sagamore (chief) of the Miami people, who became one of the most famous Native American military leaders. Historian Wiley Sword calls him "perhaps the most capable Indian leader ...

near Fort St. Clair

Fort St. Clair was a fort built during the Northwest Indian War near the modern town of Eaton, Preble County, Ohio. The site of the fort was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1970.

History

Northwest Territory Governor Ar ...

in 1792. Popular for his service in two wars, he entered politics in 1792 as a delegate to Kentucky's constitutional convention. Adair was elected to a total of eight terms in the state House of Representatives between 1793 and 1803. He served as Speaker of the Kentucky House in 1802 and 1803, and was a delegate to the state's Second Constitutional Convention in 1799. He ascended to the United States Senate to fill the seat vacated when John Breckinridge John Breckinridge or Breckenridge may refer to:

* John Breckinridge (U.S. Attorney General) (1760–1806), U.S. Senator and U.S. Attorney General

* John C. Breckinridge (1821–1875), U.S. Representative and Senator, 14th Vice President of the Unit ...

resigned to become Attorney General of the United States in the Cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

of Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

, but failed to win a full term in the subsequent election due to his implication in a treason conspiracy involving Vice President Aaron Burr. After a long legal battle, he was acquitted of any wrongdoing; and his accuser, General James Wilkinson, was ordered to issue an apology. The negative publicity kept him out of politics for more than a decade.

Adair's participation in the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

, and a subsequent protracted defense of Kentucky's soldiers against General Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

's charges that they showed cowardice at the Battle of New Orleans

The Battle of New Orleans was fought on January 8, 1815 between the British Army under Major General Sir Edward Pakenham and the United States Army under Brevet Major General Andrew Jackson, roughly 5 miles (8 km) southeast of the Frenc ...

, restored his reputation. He returned to the State House in 1817, and Isaac Shelby

Isaac Shelby (December 11, 1750 – July 18, 1826) was the first and fifth Governor of Kentucky and served in the state legislatures of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic an ...

, his commanding officer in the War who was serving a second term as governor, appointed him adjutant general

An adjutant general is a military chief administrative officer.

France

In Revolutionary France, the was a senior staff officer, effectively an assistant to a general officer. It was a special position for lieutenant-colonels and colonels in staf ...

of the state militia. In 1820, Adair was elected eighth governor on a platform of financial relief for Kentuckians hit hard by the Panic of 1819

The Panic of 1819 was the first widespread and durable financial crisis in the United States that slowed westward expansion in the Cotton Belt and was followed by a general collapse of the American economy that persisted through 1821. The Panic h ...

, and the ensuing economic recession. His primary effort toward this end was the creation of the Bank of the Commonwealth, but many of his other financial reforms were deemed unconstitutional by the Kentucky Court of Appeals

The Kentucky Court of Appeals is the lower of Kentucky's two appellate courts, under the Kentucky Supreme Court. Prior to a 1975 amendment to the Kentucky Constitution the Kentucky Court of Appeals was the only appellate court in Kentucky.

The ...

, touching off the Old Court–New Court controversy

Old or OLD may refer to:

Places

* Old, Baranya, Hungary

* Old, Northamptonshire, England

*Old Street station, a railway and tube station in London (station code OLD)

*OLD, IATA code for Old Town Municipal Airport and Seaplane Base, Old Town, ...

. Following his term as governor, Adair served one undistinguished term in the United States House of Representatives and did not run for re-election.

Early life

John Adair was born January 9, 1757, inChester County Chester County may refer to:

* Chester County, Pennsylvania, United States

* Chester County, South Carolina, United States

* Chester County, Tennessee, United States

* Cheshire or the County Palatine of Chester, a ceremonial county in the North Wes ...

in the Province of South Carolina

Province of South Carolina, originally known as Clarendon Province, was a province of Great Britain that existed in North America from 1712 to 1776. It was one of the five Southern colonies and one of the thirteen American colonies. The monar ...

, a son of Scottish immigrants Baron William and Mary oore

Oore is a village in Tori Parish, Pärnu County in southwestern Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Fin ...

Adair.Harrison in ''The Kentucky Encyclopedia'', p. 1Smith, p. 168 He was educated at schools in Charlotte, North Carolina

Charlotte ( ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of North Carolina. Located in the Piedmont region, it is the county seat of Mecklenburg County. The population was 874,579 at the 2020 census, making Charlotte the 16th-most populo ...

, and enlisted in the South Carolina colonial militia at the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

."Adair, John". ''Biographical Directory of the United States Congress'' He was assigned to the regiment of his friend, Edward Lacey, under the command of Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

Thomas Sumter

Thomas Sumter (August 14, 1734June 1, 1832) was a soldier in the Colony of Virginia militia; a brigadier general in the South Carolina militia during the American Revolution, a planter, and a politician. After the United States gained independen ...

and participated in the failed Colonial

Colonial or The Colonial may refer to:

* Colonial, of, relating to, or characteristic of a colony or colony (biology)

Architecture

* American colonial architecture

* French Colonial

* Spanish Colonial architecture

Automobiles

* Colonial (1920 au ...

assault on a Loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cro ...

outpost at the Battle of Rocky Mount and the subsequent Colonial victory at the Battle of Hanging Rock

The Battle of Hanging Rock (August 6, 1780) was a battle in the American Revolutionary War that occurred between the American Patriots and the British. It was part of a campaign by militia General Thomas Sumter to harass or destroy British outpos ...

.Fredricksen, p. 2Scoggins, p. 150 During the British victory over the Colonists at the August 16, 1780, Battle of Camden

The Battle of Camden (August 16, 1780), also known as the Battle of Camden Court House, was a major victory for the British in the Southern theater of the American Revolutionary War. On August 16, 1780, British forces under Lieutenant General ...

, Adair was taken as a prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of wa ...

.Hall, p. 1 He contracted smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

and was treated harshly by his captors during his months-long imprisonment. Although he escaped at one point, Adair was unable to reach safety because of difficulties related to his smallpox infection and was recaptured by British Colonel Banastre Tarleton

Sir Banastre Tarleton, 1st Baronet, GCB (21 August 175415 January 1833) was a British general and politician. He is best known as the lieutenant colonel leading the British Legion at the end of the American Revolution. He later served in Portug ...

after just three days. Subsequently, he was released via a prisoner exchange

A prisoner exchange or prisoner swap is a deal between opposing sides in a conflict to release prisoners: prisoners of war, spies, hostages, etc. Sometimes, dead bodies are involved in an exchange.

Geneva Conventions

Under the Geneva Convent ...

. In 1781, he was commissioned as a lieutenant in the South Carolina militia, and fought in the drawn Battle of Eutaw Springs

The Battle of Eutaw Springs was a battle of the American Revolutionary War, and was the last major engagement of the war in the Carolinas. Both sides claimed victory.

Background

In early 1781, Major General Nathanael Greene, commander of the ...

, the war's last major battle in the Carolinas. Edward Lacey was elected sheriff

A sheriff is a government official, with varying duties, existing in some countries with historical ties to England where the office originated. There is an analogous, although independently developed, office in Iceland that is commonly transla ...

of Chester County after the war, and Adair replaced him in his former capacity as the county's justice of the peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or ''puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission ( letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the sa ...

. He was chosen as a delegate to the South Carolina convention to ratify the U.S. Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the natio ...

.

In 1784, Adair married Katherine Palmer.Bussey, p. 26 They had twelve children, ten of them daughters. One married Thomas Bell Monroe

Thomas Bell Monroe (October 7, 1791 – December 24, 1865) was the 15th Secretary of State of Kentucky and a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the District of Kentucky.

Education and career

Born on October 7, ...

, who later served as Adair's Secretary of State and was appointed to a federal judgeship.Morton, p. 13 In 1786, the Adairs migrated westward to Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

, settling in Mercer County."John Adair". ''Dictionary of American Biography''

Adair was a slaveowner and slave trader.

Service in the Northwest Indian War

Enlisting for service as acaptain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

in the Northwest Indian War in 1791, Adair was soon promoted to major and assigned to the brigade of James Wilkinson. On November 6, 1792, a band of Miamis

The Miami ( Miami-Illinois: ''Myaamiaki'') are a Native American nation originally speaking one of the Algonquian languages. Among the peoples known as the Great Lakes tribes, they occupied territory that is now identified as North-central Indi ...

under the command of Little Turtle

Little Turtle ( mia, Mihšihkinaahkwa) (1747 July 14, 1812) was a Sagamore (chief) of the Miami people, who became one of the most famous Native American military leaders. Historian Wiley Sword calls him "perhaps the most capable Indian leader ...

encountered Adair and about 100 men serving under him on a scouting mission near Fort St. Clair

Fort St. Clair was a fort built during the Northwest Indian War near the modern town of Eaton, Preble County, Ohio. The site of the fort was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1970.

History

Northwest Territory Governor Ar ...

in Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

. When the Miami attacked, Adair ordered Lieutenant (and later governor of Kentucky) George Madison

George Madison (June 1763 – October 14, 1816) was the sixth Governor of Kentucky. He was the first governor of Kentucky to die in office, serving only a few weeks in 1816. Little is known of Madison's early life. He was a member of the influ ...

to attack their right flank while Adair led 25 men to attack the left flank. (Adair had intended for a subordinate to lead the charge, but the officer was killed before Adair could give the order.) The maneuver forced the Miamis to fall back and allowed Adair's men to escape. They retreated to their camp and made a stand, forcing the Miamis to withdraw. Six of Adair's men were killed; another four were missing and five were wounded. Among the wounded were Madison and Richard Taylor, father of future U.S. President Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

.Collins, p. 165

Recognizing his bravery and fighting skill, Adair's superiors promoted him to lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

. He was assigned to the command of Charles Scott, who would eventually serve as Kentucky's fourth governor. He assisted in the construction of Fort Greeneville in 1794, forwarding supplies to Anthony Wayne

Anthony Wayne (January 1, 1745 – December 15, 1796) was an American soldier, officer, statesman, and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. He adopted a military career at the outset of the American Revolutionary War, where his mil ...

during his operations which ended in a decisive victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers

The Battle of Fallen Timbers (20 August 1794) was the final battle of the Northwest Indian War, a struggle between Native American tribes affiliated with the Northwestern Confederacy and their British allies, against the nascent United States ...

.

Early political career

Popular for his military service, Adair was chosen as a delegate to the Kentucky constitutional convention in 1792.Harrison in ''The Kentucky Encyclopedia'', p. 2 Upon the state's admission to the Union, he was elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives, serving from 1793 to 1795. He remained active in the Kentucky militia, and on February 25, 1797, he was promoted to

Popular for his military service, Adair was chosen as a delegate to the Kentucky constitutional convention in 1792.Harrison in ''The Kentucky Encyclopedia'', p. 2 Upon the state's admission to the Union, he was elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives, serving from 1793 to 1795. He remained active in the Kentucky militia, and on February 25, 1797, he was promoted to brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

and given command of the 2nd Brigade of the Kentucky Militia.Trowbridge, "Kentucky's Military Governors" He was promoted to major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

and given command of the 2nd Division of the Kentucky Militia on December 16, 1799.

Adair returned to the Kentucky House of Representatives in 1798. When Kentuckians voted to hold another constitutional convention in 1799 to correct weaknesses in their first constitution, Adair was chosen as a delegate. At the convention, he was the leader of a group of politically ambitious delegates who opposed most limits on the powers and terms of office of elected officials, particularly on legislators.Harrison and Klotter, p. 77 He was elected to the Kentucky House again from 1800 to 1803. A candidate for a seat in the U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

in 1800, he was defeated in an overwhelming 68–13 vote of the legislature by John Breckinridge John Breckinridge or Breckenridge may refer to:

* John Breckinridge (U.S. Attorney General) (1760–1806), U.S. Senator and U.S. Attorney General

* John C. Breckinridge (1821–1875), U.S. Representative and Senator, 14th Vice President of the Unit ...

, who had been the acknowledged leader of the just-concluded constitutional convention.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 110 In 1802, Adair succeeded Breckinridge as Speaker of the House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hungerf ...

by a vote of 30–14 over Elder David Purviance, the candidate preferred by Governor James Garrard

James Garrard (January 14, 1749 – January 19, 1822) was an American farmer, Baptist minister and politician who served as the second governor of Kentucky from 1796 to 1804. Because of term limits imposed by the state constitution adopted in ...

.Everman, p. 69 He continued to serve as Speaker for the duration of his tenure in the House. In 1802, the legislature formed Adair County, Kentucky

Adair County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. Its county seat is Columbia. The county was founded in 1801 and named for John Adair, then Speaker of the House in Kentucky and later Governor of Kentucky (1820 – 1824). Adair Co ...

, naming it after the popular Speaker.

In January 1804, Garrard nominated Adair to the position of registrar of the state land office.Everman, p. 78 Adair's was the seventh name submitted by Garrard to the state Senate for the position; his approval by the Senate marked the end of a two-month imbroglio between Garrard and the legislature over the appointment. Later that year, he was a candidate for the U.S. Senate seat then occupied by John Brown John Brown most often refers to:

*John Brown (abolitionist) (1800–1859), American who led an anti-slavery raid in Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859

John Brown or Johnny Brown may also refer to:

Academia

* John Brown (educator) (1763–1842), Ir ...

.Remini, p. 37 Although Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. He was the seventh House speaker as well as the ninth secretary of state, al ...

supported Brown's re-election, Adair had the support of Felix Grundy

Felix Grundy (September 11, 1777 – December 19, 1840) was an American politician who served as a congressman and senator from Tennessee as well as the 13th attorney General of the United States.

Biography

Early life

Born in Berkeley County ...

. Grundy accused Brown of involvement in a conspiracy to make Kentucky a province of the Spanish government, damaging his popularity. Adair won a plurality, but not a majority, of the votes cast in six consecutive ballots. Clay then threw his support to Buckner Thruston

Buckner Thruston (February 9, 1763 – August 30, 1845) was an American lawyer, slaveowner and politician who served as United States Senator from Kentucky as well as in the Virginia House of Delegates and became a United States circuit judge of ...

, a more palatable candidate who defeated Adair on the seventh ballot. Grundy's influence in the legislature continued to grow, and when John Breckinridge resigned to accept President Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

's appointment as U.S. Attorney General

The United States attorney general (AG) is the head of the United States Department of Justice, and is the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

in August 1805, the Senate chose Adair to fill the vacancy.

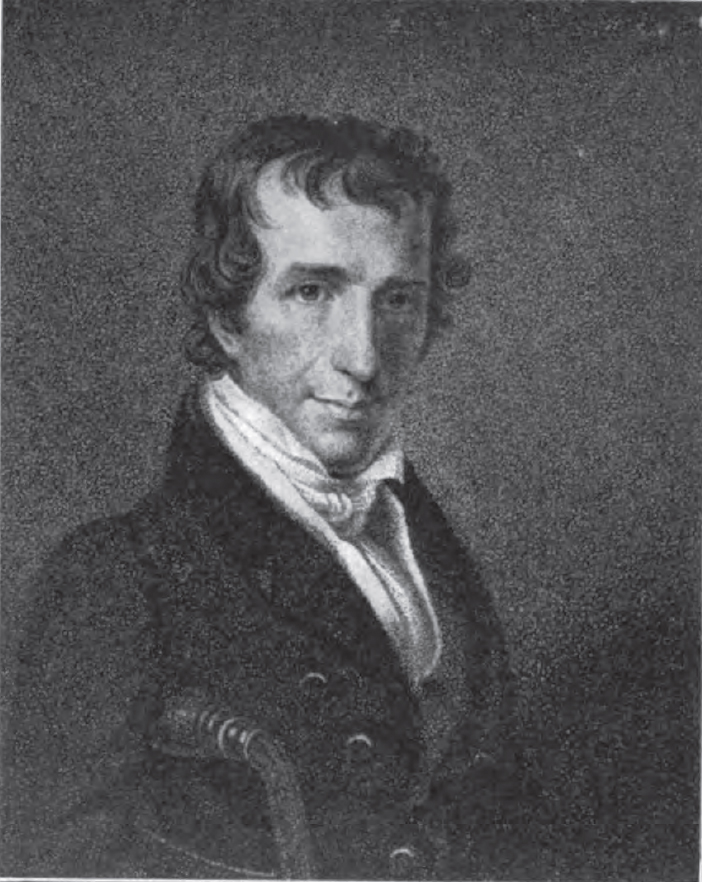

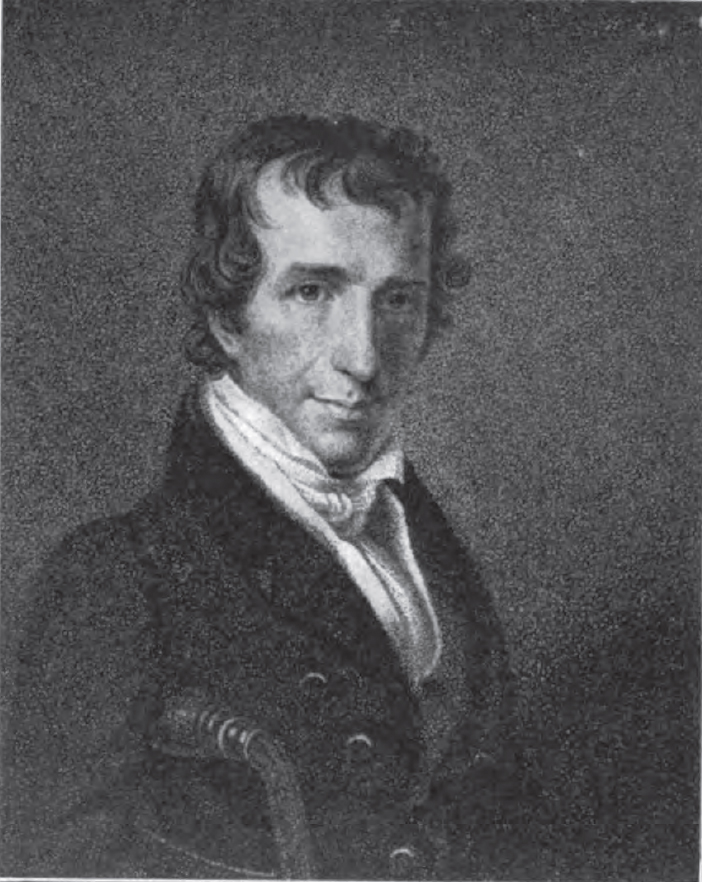

Charged with disloyalty

Former Vice-President Aaron Burr visited Kentucky in 1805, reachingFrankfort, Kentucky

Frankfort is the capital city of the Commonwealth of Kentucky, United States, and the seat of Franklin County. It is a home rule-class city; the population was 28,602 at the 2020 census. Located along the Kentucky River, Frankfort is the prin ...

, on May 25 and lodging with former Senator John Brown.Harrison and Klotter, p. 85 During the trip, he consulted with many prominent politicians, Adair among them, about the possibility of wresting Mexico from Spain. Most of those he spoke with believed he was acting on behalf of the federal government and intended to expand U.S. holdings in Mexico. Adair believed this too, having received letters from his former commander, James Wilkinson, which appeared to confirm it. In 1806, however, Burr was arrested in Frankfort on charges of treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

. Officials claimed he in fact intended to create a new, independent nation in Spanish lands.

Convinced of his innocence, Henry Clay represented Burr, while

Convinced of his innocence, Henry Clay represented Burr, while Joseph Hamilton Daveiss

Major Joseph Hamilton Daveiss (; March 4, 1774 – November 7, 1811), a Virginia-born lawyer, received a mortal wound while commanding the Dragoons of the Kentucky Militia at the Battle of Tippecanoe. Five years earlier, Daviess had tried to warn ...

acted as prosecutor.Harrison and Klotter, p. 8 Harry Innes

Harry Innes (January 4, 1752 – September 20, 1816) was a Virginia lawyer and patriot during the American Revolutionary War who became a local judge and prosecutor as well as helped establish the state of Kentucky, before he accepted appointment ...

presided over the trial, which commenced November 11. Daveiss had to ask for a postponement because Davis Floyd

Davis Floyd (1776 – December 13, 1834) was an Indiana Jeffersonian Republican politician who was convicted of aiding American Vice President Aaron Burr in the Burr conspiracy. Floyd was not convicted of treason however and returned to public li ...

, one of his key witnesses, was then serving in the Indiana General Assembly

The Indiana General Assembly is the state legislature, or legislative branch, of the state of Indiana. It is a bicameral legislature that consists of a lower house, the Indiana House of Representatives, and an upper house, the Indiana Senate. ...

and could not be present in court. The court next convened on December 2, and Daveiss again had to ask for a postponement, this time because Adair, another witness, was not present. Adair had traveled to Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

to inspect a tract of land he had recently purchased there. On his arrival in New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

, he was arrested on the order of his former commander, James Wilkinson, then serving as governor of the Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Louisiana Territory

The Territory of Louisiana or Louisiana Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1805, until June 4, 1812, when it was renamed the Missouri Territory. The territory was formed out of the ...

.

Clay had insisted that the trial proceed in Adair's absence, and, the next day, Daveiss presented indictments against Burr for treason and against Adair as a co-conspirator. After hearing testimony, the grand jury

A grand jury is a jury—a group of citizens—empowered by law to conduct legal proceedings, investigate potential criminal conduct, and determine whether criminal charges should be brought. A grand jury may subpoena physical evidence or a pe ...

rejected the indictment against Adair as "not a true bill" and similarly dismissed the charges against Burr two days later. After his vindication by the grand jury, Adair counter-sued Wilkinson in federal court.Bussey, p. 27 Although the legal battle between the two spanned several years, the court found that Wilkinson had no solid evidence against Adair and ordered Wilkinson to issue a public apology and pay Adair $2,500 in damages. Adair's acquittal and successful counter-suit came too late to prevent damage to his political career. Because of his association with Burr's scheme, he lost the election for a full term in the Senate in November 1806. Rather than wait for his partial term to expire, he resigned on November 18, 1806.

Service in the War of 1812

Adair rejoined the Kentucky militia at the outset of the

Adair rejoined the Kentucky militia at the outset of the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

. After Oliver Hazard Perry

Oliver Hazard Perry (August 23, 1785 – August 23, 1819) was an American naval commander, born in South Kingstown, Rhode Island. The best-known and most prominent member

of the Perry family naval dynasty, he was the son of Sarah Wallace A ...

's victory in the September 10, 1813, Battle of Lake Erie

The Battle of Lake Erie, sometimes called the Battle of Put-in-Bay, was fought on 10 September 1813, on Lake Erie off the shore of Ohio during the War of 1812. Nine vessels of the United States Navy defeated and captured six vessels of the Briti ...

, William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

called on Kentucky Governor Isaac Shelby

Isaac Shelby (December 11, 1750 – July 18, 1826) was the first and fifth Governor of Kentucky and served in the state legislatures of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic an ...

, a popular Revolutionary War hero, to recruit troops in Kentucky and join him in his invasion of Canada.Heidler and Heidler, p. 1 Shelby asked Adair to serve as his first aide-de-camp.Young, p. 42 Future Kentucky governor and U.S. Senator John J. Crittenden

John Jordan Crittenden (September 10, 1787 July 26, 1863) was an American statesman and politician from the U.S. state of Kentucky. He represented the state in the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate and twice served as Unite ...

was Shelby's second aide, and future U.S. Senator and Postmaster General

A Postmaster General, in Anglosphere countries, is the chief executive officer of the postal service of that country, a ministerial office responsible for overseeing all other postmasters. The practice of having a government official respons ...

William T. Barry

William Taylor Barry (February 5, 1784 – August 30, 1835) was an American slave owner, statesman and jurist. He served as Postmaster General for most of the administration of President Andrew Jackson and was the only Cabinet member not to resi ...

was his secretary. Adair rendered commendable service in the campaign, most notably at the American victory in the Battle of the Thames

The Battle of the Thames , also known as the Battle of Moraviantown, was an American victory in the War of 1812 against Tecumseh's Confederacy and their British allies. It took place on October 5, 1813, in Upper Canada, near Chatham. The British ...

on October 5, 1813.Powell, p. 26 Shelby praised Adair's service and in 1814, made him adjutant general

An adjutant general is a military chief administrative officer.

France

In Revolutionary France, the was a senior staff officer, effectively an assistant to a general officer. It was a special position for lieutenant-colonels and colonels in staf ...

of Kentucky and brevetted

In many of the world's military establishments, a brevet ( or ) was a warrant giving a commissioned officer a higher rank title as a reward for gallantry or meritorious conduct but may not confer the authority, precedence, or pay of real rank. ...

him to the rank of brigadier general.

In late 1814, Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

requested reinforcements from Kentucky for his defense of the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an oceanic basin, ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of ...

. Adair quickly raised three regiments, but the federal government provided them no weapons and no means of transportation.Harrison and Klotter, p. 93 James Taylor, Jr., then serving as quartermaster general of the state militia, took out a $6,000 mortgage on his personal land to purchase boats to transport Adair's men. The number of men with Adair was later disputed; sources variously give numbers between 700 and 1,500.Harrison and Klotter, p. 94 Many did not have weapons, and the ones who did were primarily armed with their own civilian rifles. John Thomas, to whom Adair was an adjunct, fell ill just before the battle commenced, leaving Adair responsible for all the Kentuckians present at the battle.Gillig, p. 185

On January 7, 1815, Adair traveled to New Orleans and requested that the city's leaders lend him several stands of arms from the city armory to arm his militiamen.Smith, p. 73 The officials agreed under the condition that the removal of the arms from the armory be kept secret from the citizenry. The weapons were placed in boxes and delivered to Adair's camp on the night of January 7.Smith, p. 74 At Adair's suggestion, his men were placed in reserve and located centrally behind the Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

militiamen under William Carroll. From there, they could quickly move to reinforce whichever portion of the American line received the heaviest attack from the British.

Apparently unaware of Adair's request, that evening, Jackson ordered 400 unarmed Kentucky militiamen under Colonel John Davis to march to New Orleans to obtain arms, then reinforce the 450 Louisiana militiamen under David B. Morgan on the west bank of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

.Gillig, p. 182 When they arrived in New Orleans, they were told that the city's arms had already been shipped to Adair.Smith, p. 98 The citizens collected what weapons they had —mostly old muskets in various states of disrepair —and gave them to Davis' men. About 200 men were thus armed and reported to Morgan as ordered, just hours before the start of the Battle of New Orleans

The Battle of New Orleans was fought on January 8, 1815 between the British Army under Major General Sir Edward Pakenham and the United States Army under Brevet Major General Andrew Jackson, roughly 5 miles (8 km) southeast of the Frenc ...

. The remainder of Davis's men returned to the main camp, still without weapons.

As the British approached on the morning of January 8, it became evident that they would try to break the American line through Carroll's Tennesseans, and Adair advanced his men to support them.Smith, p. 77 The main American line held and repulsed the British attack; in total, only six Americans were killed and seven wounded.Gillig, p. 178 Meanwhile, Davis' Kentuckians on the west bank had, upon their arrival in Morgan's camp, been sent to meet the advance of a secondary British force. Outnumbered, poorly armed, and without the benefit of breastworks or artillery support, they were quickly outflanked and forced to retreat. Seeing the retreat of the Kentuckians, Morgan's militiamen abandoned their breastworks; Adair would later claim they had never even fired a shot. The British quickly abandoned the position they had just captured, but Jackson resented the setback in an otherwise spectacular victory.

Controversy with Andrew Jackson

Jackson's official report blamed the Kentuckians' retreat for the collapse of the west bank defenses, and many Kentuckians felt it played down the importance of Adair's militiamen on the east bank in preserving the American line and securing the victory.Smith, p. 106Gillig, p. 179 Davis' men insisted the report was based on Jackson's misunderstanding of the facts and asked that Adair request a court of inquiry, which convened in February 1815 with Major General Carroll of Tennessee presiding.Smith, p. 109Gillig, p. 184 The court's report found that " e retreat of the Kentucky militia, which, considering their position, the deficiency of their arms, and other causes, may be excusable," and that the formation of the troops on the west bank was "exceptional", noting that 500 Louisiana troops supported by three artillery pieces and protected by a strong breastwork were charged with defending a line that stretched only while Davis's 170 Kentuckians, poorly armed and protected only by a small ditch, were expected to defend a line over long. On February 10, 1816, the Kentucky General Assembly passed a resolution thanking Adair for his service at the Battle of New Orleans and for his defense of the soldiers accused by Jackson.Young, p. 126 Jackson approved the court's findings, but they were not the full refutation of Jackson's report that many Kentuckians —including Adair —had wanted. In a letter that was quickly made public, Adair —formerly one of Jackson's close friends —insisted that Jackson withdraw or modify his official report, but Jackson refused. This ended the matter until June 1815 when H. P. Helm, secretary to John Thomas, forwarded to a Frankfort newspaper remarks from "the general" that had been annexed to the official report. "The remarks" stated that the general was now convinced that the initial reports of cowardice by Davis's men "had been misrepresented" and that their retreat had been "not only excusable, but absolutely justifiable." The remarks, popularly believed to be from Jackson in response to Adair's letter, were subsequently reprinted across Kentucky. The "general" referenced was in fact General John Thomas; Jackson had never seen them. Helm claimed he sent a subsequent correction to the newspaper that published the remarks, but it was never printed.

Jackson did not discover the remarks until they were published again in January 1817 in response to a Boston newspaper's criticism of Kentucky militiamen.Gillig, p. 186 He wrote to the ''Kentucky Reporter'' at that time, denouncing the remarks as a forgery. The ''Reporter'' investigated and published an explanation of how Thomas's remarks had been attributed to Jackson. They did not reprint Jackson's letter because they felt his claim that the remarks had been intentionally forged —a charge which was now found to be false —was too inflammatory. The editors promised that if their retraction did not satisfy Jackson, they would fully publish any of his additional remarks on the subject. In Jackson's April 1817 response, he implied that Adair had intentionally misrepresented the remarks, and reasserted that they had been forged, possibly by Adair himself. Adair believed Jackson's references to the remarks as a "forged dish, dressed in the true Spanish style" was a thinly veiled reference to Adair's alleged participation in the Burr conspiracy.Gillig, p. 191 As ostensible proof that he was not predisposed against Kentuckians, Jackson also implied that he had not reported additional dishonorable behavior by Kentucky militiamen during the battle.Gillig, p. 189 This letter thrust the dispute into the national spotlight and prompted Adair to resume correspondence with him both to defend Davis's men and refute Jackson's charges of conspiracy.Gillig, p. 190 In his May 1817 response, he reasserted his defense of the Kentucky militiamen at New Orleans and dismissed many of Jackson's allegations as unimportant and untrue. He flatly denied the existence of a conspiracy, and chastised Jackson for making charges without supporting evidence.Gillig, p. 192 Responding to Jackson's allusion to Spain, Adair recalled that Jackson had also been implicated with Burr.

Unable to provide tangible evidence of Adair's alleged misdeeds, Jackson provided indirect evidence that a conspiracy was possible. His response, delayed by his treaty negotiations with the

Jackson approved the court's findings, but they were not the full refutation of Jackson's report that many Kentuckians —including Adair —had wanted. In a letter that was quickly made public, Adair —formerly one of Jackson's close friends —insisted that Jackson withdraw or modify his official report, but Jackson refused. This ended the matter until June 1815 when H. P. Helm, secretary to John Thomas, forwarded to a Frankfort newspaper remarks from "the general" that had been annexed to the official report. "The remarks" stated that the general was now convinced that the initial reports of cowardice by Davis's men "had been misrepresented" and that their retreat had been "not only excusable, but absolutely justifiable." The remarks, popularly believed to be from Jackson in response to Adair's letter, were subsequently reprinted across Kentucky. The "general" referenced was in fact General John Thomas; Jackson had never seen them. Helm claimed he sent a subsequent correction to the newspaper that published the remarks, but it was never printed.

Jackson did not discover the remarks until they were published again in January 1817 in response to a Boston newspaper's criticism of Kentucky militiamen.Gillig, p. 186 He wrote to the ''Kentucky Reporter'' at that time, denouncing the remarks as a forgery. The ''Reporter'' investigated and published an explanation of how Thomas's remarks had been attributed to Jackson. They did not reprint Jackson's letter because they felt his claim that the remarks had been intentionally forged —a charge which was now found to be false —was too inflammatory. The editors promised that if their retraction did not satisfy Jackson, they would fully publish any of his additional remarks on the subject. In Jackson's April 1817 response, he implied that Adair had intentionally misrepresented the remarks, and reasserted that they had been forged, possibly by Adair himself. Adair believed Jackson's references to the remarks as a "forged dish, dressed in the true Spanish style" was a thinly veiled reference to Adair's alleged participation in the Burr conspiracy.Gillig, p. 191 As ostensible proof that he was not predisposed against Kentuckians, Jackson also implied that he had not reported additional dishonorable behavior by Kentucky militiamen during the battle.Gillig, p. 189 This letter thrust the dispute into the national spotlight and prompted Adair to resume correspondence with him both to defend Davis's men and refute Jackson's charges of conspiracy.Gillig, p. 190 In his May 1817 response, he reasserted his defense of the Kentucky militiamen at New Orleans and dismissed many of Jackson's allegations as unimportant and untrue. He flatly denied the existence of a conspiracy, and chastised Jackson for making charges without supporting evidence.Gillig, p. 192 Responding to Jackson's allusion to Spain, Adair recalled that Jackson had also been implicated with Burr.

Unable to provide tangible evidence of Adair's alleged misdeeds, Jackson provided indirect evidence that a conspiracy was possible. His response, delayed by his treaty negotiations with the Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

, was printed September 3, 1817, and used complicated calculations based on spacing and distance, to argue that Adair had only half the number of men he claimed to have commanded at the Battle of New Orleans. Further, he claimed that Adair had ordered Davis to New Orleans to obtain weapons knowing that the arms had already been taken by other brigades under Adair's command.Gillig, p. 194 Either Adair had given a foolish order, or he did not have as many men in his main force as he claimed. He closed by promising that this would be his last statement on the matter.Gillig, p. 195 Adair's October 29, 1817, response was delayed, he said, because he was awaiting documents from New Orleans that never came. In it, he quoted from a letter to Jackson's aide-de-camp —cited by Jackson himself in previous correspondence —showing that Jackson had been made aware of both the existence and the authorship of Thomas's remarks in 1815 but declined the opportunity to refute them.Gillig, p. 196 He also defended his account of the number of troops under his command, which he had consistently reported as being near 1,000, and asked why Jackson had not challenged it until now. Finally, he claimed that not only did he retrieve the weapons from New Orleans under Jackson's orders, but he rode Jackson's horse to New Orleans to effect the transaction.Gillig, p. 197 Tradition holds that this letter prompted either Adair or Jackson to challenge the other to a duel

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two people, with matched weapons, in accordance with agreed-upon Code duello, rules.

During the 17th and 18th centuries (and earlier), duels were mostly single combats fought with swords (the r ...

, but friends of both men averted the conflict after assembling to watch; no written evidence of the event exists.Gillig, p. 199Historian Zachariah Frederick Smith gives a detailed account of this tradition that he claims was told to him by a descendant of Adair's cousin. See Smith, pp. 113–114 Tensions between the two eventually eased, and Adair came to comfort Jackson after his wife Rachel

Rachel () was a Biblical figure, the favorite of Jacob's two wives, and the mother of Joseph and Benjamin, two of the twelve progenitors of the tribes of Israel. Rachel's father was Laban. Her older sister was Leah, Jacob's first wife. Her aun ...

's death in 1828.Gillig, p. 201 Adair also campaigned for Jackson during his presidential campaigns in 1824, 1828, and 1832

Events

January–March

* January 6 – Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison founds the New-England Anti-Slavery Society.

* January 13 – The Christmas Rebellion of slaves is brought to an end in Jamaica, after the island's white plan ...

. Jackson's opponents compiled copies of his letters into campaign pamphlets to use against him in Kentucky during these elections.

Governor of Kentucky

Adair's participation in the War of 1812 and subsequent correspondence with Jackson restored his reputation. He continued to serve as adjutant general until 1817, when the voters returned him to the state House of Representatives. He was nominated for Speaker of the House during that term, and, although he was not elected, he drew support from members of both parties, largely because of his correspondence with Jackson.Gillig, p. 180

In the aftermath of the

Adair's participation in the War of 1812 and subsequent correspondence with Jackson restored his reputation. He continued to serve as adjutant general until 1817, when the voters returned him to the state House of Representatives. He was nominated for Speaker of the House during that term, and, although he was not elected, he drew support from members of both parties, largely because of his correspondence with Jackson.Gillig, p. 180

In the aftermath of the Panic of 1819

The Panic of 1819 was the first widespread and durable financial crisis in the United States that slowed westward expansion in the Cotton Belt and was followed by a general collapse of the American economy that persisted through 1821. The Panic h ...

—the first major financial crisis in United States history —the primary political issue of the day was debt relief.Doutrich, p. 15 The federal government had created the Second Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was the second federally authorized Hamiltonian national bank in the United States. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the bank was chartered from February 1816 to January 1836.. The Bank's formal name, ac ...

in 1817, and its strict credit policy hit Kentucky's large debtor class hard. Sitting governor Gabriel Slaughter

Gabriel Slaughter (December 12, 1767September 19, 1830) was the List of Governors of Kentucky, seventh Governor of Kentucky and was the first person to ascend to that office upon the death of the sitting governor. His family moved to Kentucky fr ...

had lobbied for some measures favored by the state's debtors, particularly punitive taxes against the branches of the Bank of the United States in Louisville

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border.

...

and Lexington.Doutrich, p. 14 The Second Party System

Historians and political scientists use Second Party System to periodize the political party system operating in the United States from about 1828 to 1852, after the First Party System ended. The system was characterized by rapidly rising levels ...

had not yet developed, but there were nonetheless two opposing factions that arose around the debt relief issue.Doutrich, p. 23 The first —primarily composed of land speculators

In finance, speculation is the purchase of an asset (a commodity, goods, or real estate) with the hope that it will become more valuable shortly. (It can also refer to short sales in which the speculator hopes for a decline in value.)

Many s ...

who had bought large land parcels on credit and were unable to repay their debts due to the financial crisis —was dubbed the Relief Party (or "faction") and favored more legislation favorable to debtors. Opposed to them was the Anti-Relief Party; it was composed primarily of the state's aristocracy, many of whom were creditors to the land speculators and demanded that their contracts be adhered to without interference from the government. They claimed that no government intervention could effectively aid the debtors and that attempts to do so would only prolong the economic depression.

Adair was the clear leader of the Relief faction, and his popularity had been enhanced thanks to his lengthy and public dispute with Jackson. In the 1820 gubernatorial election, he was elected as Kentucky's chief executive over three fellow Democratic-Republicans

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early ...

.Harrison and Klotter, p. 110 Adair garnered 20,493 votes; U.S. Senator William Logan finished second with 19,497, fellow veteran Joseph Desha

Joseph Desha (December 9, 1768 – October 11, 1842) was a U.S. Representative and the ninth governor of the U.S. state of Kentucky. After the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, Desha's Huguenot ancestors fled from France to Pennsylvania, wh ...

received 12,419, and Colonel Anthony Butler mustered only 9,567 votes.Young, p. 127 Proponents of debt relief measures also won majorities in both houses of the General Assembly.

Debt relief

Kentucky historianLowell H. Harrison

Dr. Lowell Hayes Harrison (October 23, 1922 – October 12, 2011) was an American historian specializing in the U.S. state of Kentucky.

Biography

Harrison graduated from College High (Bowling Green, Kentucky). He was a veteran of World Wa ...

opined that the most important measure implemented during Adair's administration was the creation of the Bank of the Commonwealth in 1820. The bank made generous loans and liberally issued paper money. Although bank notes issued by the Bank of the Commonwealth quickly fell well below par, creditors who refused to accept these devalued notes had to wait two years before seeking replevin

Replevin () or claim and delivery (sometimes called revendication) is a legal remedy, which enables a person to recover personal property taken wrongfully or unlawfully, and to obtain compensation for resulting losses.

Etymology

The word "replevi ...

. To inspire confidence in the devalued notes, Adair mandated that all officers of the state receive their salaries in notes issued by the Bank of the Commonwealth.Stickles, p. 72

The state's other bank, the Bank of Kentucky, adhered to more conservative banking practices. While this held the value of its notes closer to par, it also rendered loans less available, which angered relief-minded legislators; consequently, they revoked the bank's charter in December 1822. Adair oversaw the abolition of the practice of incarceration for debt, and sanctioned rigorous anti-gambling legislation."Kentucky Governor John Adair". ''National Governors Association'' Legislators also exempted from forced sale the items then considered necessary for making a living —a horse, a plow, a hoe, and an ax.

The Kentucky Court of Appeals

The Kentucky Court of Appeals is the lower of Kentucky's two appellate courts, under the Kentucky Supreme Court. Prior to a 1975 amendment to the Kentucky Constitution the Kentucky Court of Appeals was the only appellate court in Kentucky.

The ...

, then the state's court of last resort

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

, struck down the law ordering a two-year stay of replevin because it impaired the obligation of contracts. At about the same time, the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

issued its decision in the case of ''Green v. Biddle

''Green v. Biddle'', 1 U.S. (8 Wheat.) 1 (1823), is a 6-to-1 ruling by the Supreme Court of the United States that held that the U.S. state, state of Virginia had properly entered into a compact with the United States federal government under Artic ...

'', holding that land claims granted by Virginia in the District of Kentucky before Kentucky became a separate state took precedence over those later granted by the state of Kentucky if the two were in conflict. Adair denounced this decision in an 1823 message to the legislature, warning against federal and judicial interference in the will of the people, expressed through the legislature.Stickles, p. 34 Emboldened by Adair's message, Relief partisans sought to remove the three justices of the state Court of Appeals, as well as James Clark, a lower court judge who had issued a similar ruling, from the bench. The judges were spared when their opponents failed to obtain the two-thirds majority 2/3 may refer to:

* A fraction with decimal value 0.6666...

* A way to write the expression "2 ÷ 3" ("two divided by three")

* 2nd Battalion, 3rd Marines of the United States Marine Corps

* February 3

* March 2

Events Pre-1600

* 537 – ...

required for removal.

Other matters of Adair's term

Adair urged legislators to create a public school system. In response, the General Assembly passed an act creating a state "Literary Fund" which received half of the clear profits accrued by the Bank of the Commonwealth.Harrison and Klotter, p. 149 The fund was to be available, proportionally, to each of the state's counties for the establishment of "a system of general education".Ellis, p. 16 In the tumultuous economic environment, however, legislators routinely voted to borrow from the Literary Fund to pay for other priorities, chiefly the construction ofinternal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, canal ...

.

Adair's

Adair's lieutenant governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

, William T. Barry, and John Pope, Secretary of State under Adair's predecessor, headed a six-man committee authorized by the act to study the creation of a system of common school A common school was a public school in the United States during the 19th century. Horace Mann (1796–1859) was a strong advocate for public education and the common school. In 1837, the state of Massachusetts appointed Mann as the first secretary o ...

s. The "Barry Report," delivered to the legislature in December 1822, was lauded by statesmen including John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

. Authored by committee member Amos Kendall

Amos Kendall (August 16, 1789 – November 12, 1869) was an American lawyer, journalist and politician. He rose to prominence as editor-in-chief of the '' Argus of Western America'', an influential newspaper in Frankfort, the capital of the U.S. ...

, it criticized the idea of land grant academies then prevalent in the state as unworkable outside affluent towns.Ellis, p. 17 It also concluded that the Literary Fund alone was insufficient for funding a system of common schools. The report recommended that funds only be made available to counties that imposed a county tax for the benefit of the public school system. Legislators largely ignored the report, a decision Kentucky historian Thomas D. Clark

Thomas Dionysius Clark (July 14, 1903 – June 28, 2005) was an American historian. Clark saved from destruction a large portion of Kentucky's printed history, which later became a core body of documents in the Kentucky Department for Libraries and ...

called "one of the most egregious blunders in American educational history".

Adair's endorsement of the Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a Slave states an ...

was instrumental in securing its passage by Kentucky legislators. He advocated prison reform and better treatment of the insane. He also oversaw the enactment of a plan for internal improvements, including improved navigation on the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

.

Later life

Barred from seeking immediate re-election by the state constitution, Adair retired to his farm in Mercer County at the expiration of his term as governor. Shortly after returning to private life, he began to complain about the low value of Bank of the Commonwealth notes —then worth about half par —and petitioned the legislature to remedy the situation. The complaint of a former Relief Party governor over the ill effects of pro-relief legislation prompted wry celebration among members of the Anti-Relief faction. Adair made one final contribution to the public when he was elected to theU.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

as a Jackson Democrat

Jacksonian democracy was a 19th-century political philosophy in the United States that expanded suffrage to most white men over the age of 21, and restructured a number of federal institutions. Originating with the seventh U.S. president, And ...

in 1831. During the 22nd Congress, he served on the Committee on Military Affairs.Smith, p. 170 During his term, he made only one speech, and it was so inaudible that no one knew what position he was advocating. The House reporter speculated that it concerned mounting Federal troops on horseback. He did not run for re-election in 1833, and left public life for good.

Death and legacy

He died at home inHarrodsburg

Harrodsburg is a home rule-class city in Mercer County, Kentucky, United States. It is the seat of its county. The population was 9,064 at the 2020 census.

Although Harrodsburg was formally established by the House of Burgesses after Boonesbo ...

on May 19, 1840, and was buried on the grounds of his estate, White Hall. In 1872, his remains were moved to the Frankfort Cemetery

The Frankfort Cemetery is a historic rural cemetery located on East Main Street in Frankfort, Kentucky. The cemetery is the burial site of Daniel Boone and contains the graves of other famous Americans including seventeen Kentucky governors and a ...

, by the state capitol

This is a list of state and territorial capitols in the United States, the building or complex of buildings from which the government of each U.S. state, the District of Columbia and the organized territories of the United States, exercise its ...

, and the Commonwealth erected a marker over his grave there.

In addition to Adair County in Kentucky, Adair County, Missouri

Adair County is a county located in the northeastern part of the U.S. state of Missouri. The population census for 2020 was 25,314. As of July 1, 2021, the U.S. Census Bureau's Population Estimates for the county is 25,185, a -0.5% change. Adai ...

, Adair County, Iowa

Adair County is a county in the U.S. state of Iowa. As of the 2020 census, the population was 7,496. Its county seat is Greenfield.

History

Adair County was formed in 1851 from sections of Pottawattamie County. It was named for John Adair, ...

, and the towns of Adairville, Kentucky

Adairville is a List of cities in Kentucky, home rule-class city in Logan County, Kentucky, Logan County, Kentucky, in the United States. Established on January 31, 1833, it was named for list of governors of Kentucky, Governor John Adair and incor ...

, and Adair, Iowa

Adair is a city in Adair and Guthrie counties of Iowa in the United States. The population was 791 at the 2020 census.

History

The Rock Island Railroad was built through the area in 1868, which led to the area being known as Summit Cut. This ...

, were named in his honor.Euntaek, "Jesse James"

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

*External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Adair, John 1757 births 1840 deaths People from Chester County, South Carolina American people of Scotch-Irish descent American Protestants Kentucky Democratic-Republicans Democratic-Republican Party United States senators from Kentucky Jacksonian members of the United States House of Representatives from Kentucky Governors of Kentucky Democratic-Republican Party state governors of the United States Speakers of the Kentucky House of Representatives Members of the Kentucky House of Representatives South Carolina militiamen in the American Revolution American Revolutionary War prisoners of war held by Great Britain American people of the Northwest Indian War People from Kentucky in the War of 1812 Burials at Frankfort Cemetery 19th-century American politicians