Johannes Becher on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

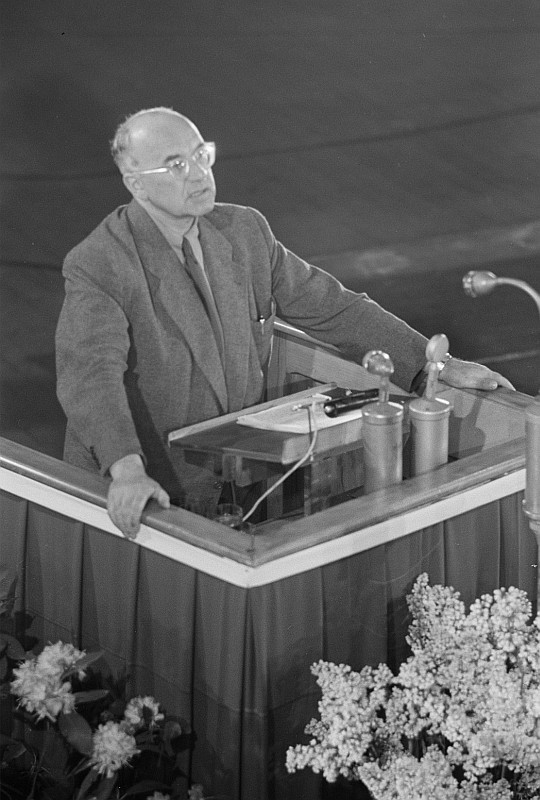

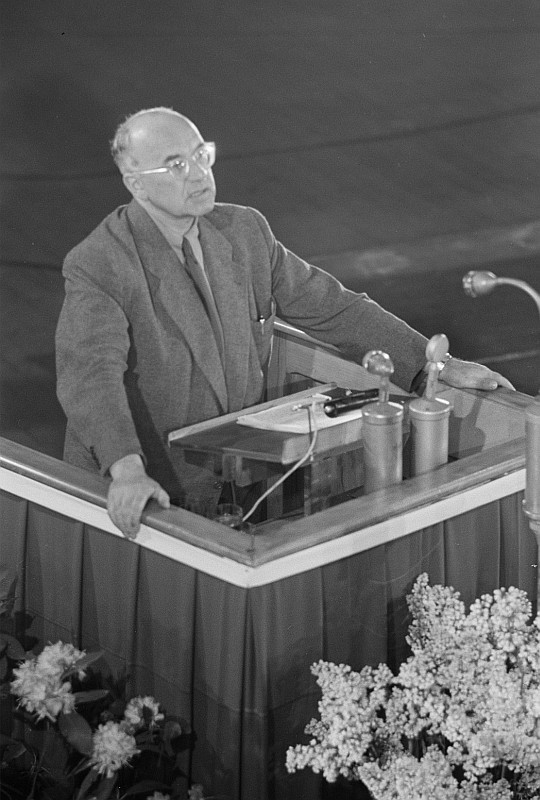

Johannes Robert Becher (, 22 May 1891 – 11 October 1958) was a German

Johannes Robert Becher (, 22 May 1891 – 11 October 1958) was a German

''Encyclopedia of German Literature,'' Chicago and London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 2000, by permission at Digital Commons, University of Nebraska, accessed 3 February 2013 His father succeeded in quashing the case of killing on demand. Becher was certified insane. His early poetry was filled with struggling to come to terms with this event. From 1911 he studied

''French Cultural Studies'', 2000, Vol. 11:387, Sage Publications, accessed 30 January 2013 Finally, in 1935 Becher emigrated to theGeorg Lukács, translated by Jeremy Gaines and Paul Keast, ''German Realists in the Nineteenth Century''

ed. Rodney Livingstone, MIT Press, 2000, p. xv They intensively studied 18th- and 19th-century literature together, after which Becher turned from modernism to

The following year, in declining health, Becher gave up all his offices and functions in September 1958. He died of

The following year, in declining health, Becher gave up all his offices and functions in September 1958. He died of

Robert K. Shirer, "Johannes R. Becher 1891–1958"

''Encyclopedia of German Literature,'' Chicago and London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 2000, by permission at Digital Commons, University of Nebraska {{DEFAULTSORT:Becher, Johannes R. 1891 births 1958 deaths Writers from Munich People from the Kingdom of Bavaria Independent Social Democratic Party politicians Communist Party of Germany politicians Members of the Central Committee of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany Government ministers of East Germany Members of the Provisional Volkskammer Members of the 1st Volkskammer Members of the 2nd Volkskammer Cultural Association of the GDR members National Committee for a Free Germany members 20th-century German novelists German Communist writers German Communist poets East German poets East German writers German Expressionist writers German male novelists German-language poets German poets National anthem writers Refugees from Nazi Germany in the Soviet Union Stalin Peace Prize recipients Recipients of the National Prize of East Germany Recipients of the Patriotic Order of Merit in silver German magazine founders

Johannes Robert Becher (, 22 May 1891 – 11 October 1958) was a German

Johannes Robert Becher (, 22 May 1891 – 11 October 1958) was a German politician

A politician is a person active in party politics, or a person holding or seeking an elected office in government. Politicians propose, support, reject and create laws that govern the land and by an extension of its people. Broadly speaking ...

, novelist

A novelist is an author or writer of novels, though often novelists also write in other genres of both fiction and non-fiction. Some novelists are professional novelists, thus make a living writing novels and other fiction, while others asp ...

, and poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator ( thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems ( oral or wri ...

. He was affiliated with the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) before World War II. At one time, he was part of the literary avant-garde, writing in an expressionist style.

With the rise of the Nazi Party in Germany, modernist artistic movements were suppressed. Becher escaped from a military raid in 1933 and settled in Paris for a couple of years. He migrated to the Soviet Union in 1935 with the central committee of the KPD. After the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, Becher and other German communists were evacuated to internal exile in Tashkent

Tashkent (, uz, Toshkent, Тошкент/, ) (from russian: Ташкент), or Toshkent (; ), also historically known as Chach is the capital and largest city of Uzbekistan. It is the most populous city in Central Asia, with a population of 2 ...

.

He returned to favor in 1942 and was recalled to Moscow. After the end of World War II, Becher left the Soviet Union and returned to Germany, settling in the Soviet-occupied zone that later became East Berlin. As a member of the KPD, he was appointed to various cultural and political positions and became part of the leadership of the Socialist Unity Party. In 1949, he helped found the DDR Academy of Arts, Berlin

The Academy of Arts (german: Akademie der Künste) is a state arts institution in Berlin, Germany. The task of the Academy is to promote art, as well as to advise and support the states of Germany.

The Academy's predecessor organization was fo ...

, and served as its president from 1953 to 1956. In 1953 he was awarded the Stalin Peace Prize (later the Lenin Peace Prize). He was the culture minister of the German Democratic Republic

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**G ...

(GDR) from 1954 to 1958.

Early life

Johannes R. Becher was born in Munich in 1891, the son of Judge Heinrich Becher and his wife Johanna, née Bürck. He attended local schools. In April 1910, Becher and Fanny Fuss, a young woman he had encountered in January of that year, planned a joint suicide; Becher shot them both, killing her and wounding himself severely.Robert K. Shirer, "Johannes R. Becher 1891–1958"''Encyclopedia of German Literature,'' Chicago and London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 2000, by permission at Digital Commons, University of Nebraska, accessed 3 February 2013 His father succeeded in quashing the case of killing on demand. Becher was certified insane. His early poetry was filled with struggling to come to terms with this event. From 1911 he studied

medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pr ...

and philosophy in college in Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and Ha ...

and Jena

Jena () is a German city and the second largest city in Thuringia. Together with the nearby cities of Erfurt and Weimar, it forms the central metropolitan area of Thuringia with approximately 500,000 inhabitants, while the city itself has a po ...

. He left his studies and became an expressionist writer, his first works appearing in 1913. An injury from his suicide attempt made him unfit for military service/ and he became addicted to morphine, which he struggled with for the rest of the decade.

Political activity in Germany

He was also engaged in many communistorganisation

An organization or organisation (Commonwealth English; see spelling differences), is an entity—such as a company, an institution, or an association—comprising one or more people and having a particular purpose.

The word is derived from ...

s, joining the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (german: Unabhängige Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, USPD) was a short-lived political party in Germany during the German Empire and the Weimar Republic. The organization was establish ...

in 1917, then went over to the Spartacist League in 1918 from which emerged the Communist Party of Germany (KPD). In 1920 he left the KPD, disappointed with the failure of the German Revolution, and embraced religion. In 1923, he returned to the KPD and very actively worked within the party.

His art entered an expressionist period, from which he would later dissociate himself. He was part of '' die Kugel'', an artistic group based in Magdeburg. During this time, he published in the magazines ''Verfall und Triumph'', ''Die Aktion

''Die Aktion'' ("The Action") was a German literary and political magazine, edited by Franz Pfemfert and published between 1911 and 1932 in Berlin-Wilmersdorf; it promoted literary Expressionism and stood for left-wing politics. To begin with, '' ...

'' (The Action) and ''Die neue Kunst''.

In 1925 government reaction against his anti-war novel, ''(CHCI=CH)3As (Levisite) oder Der einzig gerechte Krieg,'' resulted in his being indicted for "''literarischer Hochverrat''" or "literary high treason". It was not until 1928 that this law was amended.

That year, Becher became a founding member of the KPD-aligned Association of Proletarian-Revolutionary Authors (Bund proletarisch-revolutionärer Schriftsteller), serving as its first chairman and co-editor of its magazine, ''Die Linkskurve''. From 1932 Becher became a publisher of the newspaper, ''Die Rote Fahne''. In the same year he was elected representing the KPD to the Reichstag.

Fleeing from Nazis

After the Reichstag fire, Becher was placed on the Naziblacklist

Blacklisting is the action of a group or authority compiling a blacklist (or black list) of people, countries or other entities to be avoided or distrusted as being deemed unacceptable to those making the list. If someone is on a blacklist, ...

, but he escaped from a large raid

Raid, RAID or Raids may refer to:

Attack

* Raid (military), a sudden attack behind the enemy's lines without the intention of holding ground

* Corporate raid, a type of hostile takeover in business

* Panty raid, a prankish raid by male college ...

in the Berlin artist colony near Breitenbachplatz in Wilmersdorf

Wilmersdorf (), an inner-city locality of Berlin, lies south-west of the central city. Formerly a borough by itself, Wilmersdorf became part of the new borough of Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf in Berlin's 2001 administrative reform.

History

The v ...

. By 15 March 1933, he, with the support of the secretary of the Association of Proletarian-Revolutionary Authors, traveled to the home of Willy Harzheim. After staying briefly in Brno, he moved to Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and List of cities in the Czech Republic, largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 milli ...

after some weeks.

He traveled on to Zurich and Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

, where he lived for a time as part of the large émigré community. There his portrait was done by the Hungarian artist, Lajos Tihanyi

Lajos Tihanyi (29 October 1885 – 11 June 1938) was a Hungarian painter and lithographer who achieved international renown working outside his country, primarily in Paris, France. After emigrating in 1919, he never returned to Hungary, even on a ...

, whom he befriended.Valerie Majoros, "Lajos Tihanyi and his friends in the Paris of the nineteen-thirties"''French Cultural Studies'', 2000, Vol. 11:387, Sage Publications, accessed 30 January 2013 Finally, in 1935 Becher emigrated to the

USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

as did other members of the central committee of the KPD. In Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

he became editor-in-chief of the German émigré magazine, ''Internationale Literatur-Deutsche Blätter.'' He was selected as a member of the Central Committee of the KPD. Soon Becher was caught up in the midst of the Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secret ...

. In 1935 he was accused of links with Leon Trotsky. Becher tried to save himself by “informing” on other writers' alleged political misdemeanors. From 1936, he was forbidden to leave the USSR. During this period, he struggled with depression and tried several times to commit suicide.

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of 1939 horrified German communists. Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, the government evacuated the German communists to internal exile. Becher was evacuated to Tashkent

Tashkent (, uz, Toshkent, Тошкент/, ) (from russian: Ташкент), or Toshkent (; ), also historically known as Chach is the capital and largest city of Uzbekistan. It is the most populous city in Central Asia, with a population of 2 ...

, as were most of the communist émigrés. It became the center of evacuation for hundreds of thousands of Russians and Ukrainians from the war zones, and the government relocated industry here to preserve some capacity from the Germans.

During his time in Tashkent, he befriended Georg Lukács

Georg may refer to:

* ''Georg'' (film), 1997

* Georg (musical), Estonian musical

* Georg (given name)

* Georg (surname)

* , a Kriegsmarine coastal tanker

See also

* George (disambiguation)

{{disambiguation ...

, the Hungarian philosopher and literary critic, who was also evacuated there.ed. Rodney Livingstone, MIT Press, 2000, p. xv

Socialist Realism

Socialist realism is a style of idealized realistic art that was developed in the Soviet Union and was the official style in that country between 1932 and 1988, as well as in other socialist countries after World War II. Socialist realism is c ...

.

Becher was recalled to Moscow by 1942. In 1943, he became one of the founders of the National Committee for a Free Germany.

Return to East Germany

After the Second World War, Becher returned to Germany with a KPD team, where he settled in the Soviet zone of occupation. There he was appointed to various cultural-political positions. He took part in the establishment of the Cultural Association, to "revive German culture," and founded the Aufbau-Verlag publishing house and the literature magazine, '' Sinn und Form''. He also contributed to the satirical magazine, '' Ulenspiegel''. In 1946, Becher was selected for the Party Executive Committee and the Central Committee of the Socialist Unity Party. After the establishment of theGerman Democratic Republic

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**G ...

(GDR) on 7 October 1949, he became a member of the Volkskammer

__NOTOC__

The Volkskammer (, ''People's Chamber'') was the unicameral legislature of the German Democratic Republic (colloquially known as East Germany).

The Volkskammer was initially the lower house of a bicameral legislature. The upper house w ...

. He also wrote the lyrics to Hanns Eisler

Hanns Eisler (6 July 1898 – 6 September 1962) was an Austrian composer (his father was Austrian, and Eisler fought in a Hungarian regiment in World War I). He is best known for composing the national anthem of East Germany, for his long artisti ...

's melody " Auferstanden aus Ruinen," which became the national anthem of the GDR.

That year, he helped establish the DDR Academy of Arts, Berlin

The Academy of Arts (german: Akademie der Künste) is a state arts institution in Berlin, Germany. The task of the Academy is to promote art, as well as to advise and support the states of Germany.

The Academy's predecessor organization was fo ...

. He served as its president from 1953 to 1956, succeeding Arnold Zweig

Arnold Zweig (10 November 1887 – 26 November 1968) was a German writer, pacifist and socialist.

He is best known for his six-part cycle on World War I.

Life and work

Zweig was born in Glogau, Prussian Silesia (now Głogów, Poland), the son ...

. In January 1953 he received the Stalin Peace Prize (later renamed the Lenin Peace Prize) in Moscow.

In Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as ...

in 1955, the German Institute for Literature was founded and originally named in Becher's honor. The institute's purpose was to train socialist writers. Institute graduates include Erich Loest, Volker Braun, Sarah Kirsch and Rainer Kirsch.

From 1954 to 1958, Becher served as Minister of Culture of the GDR. During the Khrushchev Thaw, Becher fell out of favor. Internal struggles of the party eventually lead to his political demotion in 1956.

Late in his life, Becher began to renounce socialism. His book ''Das poetische Prinzip'' (The Poetic Principle) wherein he calls socialism the fundamental error of his life Grundirrtum meines Lebens"was only published in 1988.

The following year, in declining health, Becher gave up all his offices and functions in September 1958. He died of

The following year, in declining health, Becher gave up all his offices and functions in September 1958. He died of cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal b ...

on 11 October 1958 in the East Berlin government hospital. Becher was buried at the Dorotheenstadt cemetery

The Dorotheenstadt Cemetery, officially the Cemetery of the Dorotheenstadt and Friedrichswerder Parishes, is a landmarked Protestant burial ground located in the Berlin district of Mitte which dates to the late 18th century. The entrance to the ...

in central Berlin, with his gravesite designated as a ''grave of honor'' (german: Ehrengrab) of Berlin. Becher lived at Majakowskiring 34, Pankow

Pankow () is the most populous and the second-largest borough by area of Berlin. In Berlin's 2001 administrative reform, it was merged with the former boroughs of Prenzlauer Berg and Weißensee; the resulting borough retained the name Pankow. ...

, East Berlin.

Legacy and honours

The party praised Becher after his death as the "greatest German poet in recent history". However, his work was criticised by younger East German authors, such as Katja Lange-Müller, as backward. Official awards and honours include the following: *1953 Stalin Peace Prize (later renamed the Lenin Peace Prize) *The Institut für Literatur Johannes R. Becher was founded in 1955 in Leipzig and named in his honor.Works

* ''Der Ringende. Kleist-Hymne.'' (1911) * ''Erde'', novel (1912) * ''De profundis domine'' (1913) * ''Der Idiot'' (1913) * ''Verfall und Triumph'' (1914) ** ''Erster Teil'', Poetry ** ''Zweiter Teil. Versuche in Prosa.'' * ''Verbrüderung'', Poetry (1916) * ''An Europa'', Poetry (1916) * ''Päan gegen die Zeit'', Poetry (1918) * ''Die heilige Schar'', Poetry (1918) * ''Das neue Gedicht. Auswahl (1912–1918)'', Poetry (1918) * ''Gedichte um Lotte'' (1919) * ''Gedichte für ein Volk'' (1919) * ''An alle!'', Poetry (1919) * ''Zion'', Poetry (1920) * ''Ewig im Aufruhr'' (1920) * ''Mensch, steh auf!'' (1920) * ''Um Gott'' (1921) * ''Der Gestorbene'' (1921) * ''Arbeiter, Bauern, Soldaten. Entwurf zu einem revolutionären Kampfdrama.'' (1921) * ''Verklärung'' (1922) * ''Vernichtung'' (1923) * ''Drei Hymnen'' (1923) * ''Vorwärts, du rote Front! Prosastücke.'' (1924) * ''Hymnen'' (1924) * ''Am Grabe Lenins'' (1924) * ''Roter Marsch. Der Leichnam auf dem Thron/Der Bombenflieger'' (1925) * ''Maschinenrhythmen'', Poetry (1926) * ''Der Bankier reitet über das Schlachtfeld'', Narrative (1926) * ''Levisite oder Der einzig gerechte Krieg'', Novel (1926) * ''Die hungrige Stadt'', Poetry (1927) * ''Im Schatten der Berge'', Poetry (1928) * ''Ein Mensch unserer Zeit: Gesammelte Gedichte'', Poetry (1929) * ''Graue Kolonnen: 24 neue Gedichte'' (1930) * ''Der große Plan. Epos des sozialistischen Aufbaus.'' (1931) * ''Der Mann, der in der Reihe geht. Neue Gedichte und Balladen.'', Poetry (1932) * ''Der Mann, der in der Reihe geht. Neue Gedichte und Balladen.'', Poetry (1932) * ''Neue Gedichte'' (1933) * ''Mord im Lager Hohenstein. Berichte aus dem Dritten Reich.'' (1933) * ''Es wird Zeit'' (1933) * ''Deutscher Totentanz 1933'' (1933) * ''An die Wand zu kleben'', Poetry (1933) * ''Deutschland. Ein Lied vom Köpferollen und von den „nützlichen Gliedern“'' (1934) * ''Der verwandelte Platz. Erzählungen und Gedichte'', Narrative and Poetry (1934) * ''Der verwandelte Platz. Erzählungen und Gedichte'', Narrative and Poetry (1934) * ''Das Dritte Reich'', Poetry illustrated byHeinrich Vogeler

Heinrich Vogeler (December 12, 1872 – June 14, 1942) was a German painter, designer, and architect, associated with the Düsseldorf school of painting.

Early life

He was born in Bremen, and studied at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf from 1 ...

(1934)

* ''Der Mann, der alles glaubte'', Poetry (1935)

* ''Der Glücksucher und die sieben Lasten. Ein hohes Lied.'' (1938)

* ''Gewißheit des Siegs und Sicht auf große Tage. Gesammelte Sonette 1935–1938.'' (1939)

* ''Wiedergeburt'', Poetry (1940)

* ''Die sieben Jahre. Fünfundzwanzig ausgewählte Gedichte aus den Jahren 1933–1940.'' (1940)

* ''Abschied. Einer deutschen Tragödie erster Teil, 1900–1914.'', Novel (1940)

* ''Deutschland ruft'', Poetry (1942)

* ''Deutsche Sendung. Ein Ruf an die deutsche Nation.'' (1943_

* ''Dank an Stalingrad'', Poetry (1943)

* ''Die Hohe Warte Deutschland-Dichtung'', Poetry (1944)

* ''Dichtung. Auswahl aus den Jahren 1939–1943.'' (1944)

* ''Das Sonett'' (1945)

* ''Romane in Versen'' (1946)

* ''Heimkehr. Neue Gedichte.'', Poetry (1946)

* ''Erziehung zur Freiheit. Gedanken und Betrachtungen.'' (1946)

* ''Deutsches Bekenntnis. 5 Reden zu Deutschlands Erneuerung.'' (1945)

* ''Das Führerbild. Ein deutsches Spiel in fünf Teilen.'' (1946)

* ''Wiedergeburt. Buch der Sonette.'' (1947)

* ''Lob des Schwabenlandes. Schwaben in meinem Gedicht.'' (1947)

* ''Volk im Dunkel wandelnd'' (1948)

* ''Die Asche brennt auf meiner Brust'' (1948)

* ''Neue deutsche Volkslieder'' (1950)

* ''Glück der Ferne – leuchtend nah. Neue Gedichte'', Poetry (1951)

* ''Auf andere Art so große Hoffnung. Tagebuch 1950.'' (1951)

* ''Verteidigung der Poesie. Vom Neuen in der Literatur.'' (1952)

* ''Schöne deutsche Heimat'' (1952)

* ''Winterschlacht (Schlacht um Moskau). Eine deutsche Tragödie in 5 Akten mit einem Vorspiel.'' (1953)

* ''Der Weg nach Füssen'', Play (1953)

* ''Zum Tode J. W. Stalins'' (1953)

* ''Wir, unsere Zeit, das zwanzigste Jahrhundert'' (1956)

* ''Das poetische Prinzip'' (1957)

* ''Schritt der Jahrhundertmitte. Neue Dichtungen'', Poetry (1958)

References

External links

* *Robert K. Shirer, "Johannes R. Becher 1891–1958"

''Encyclopedia of German Literature,'' Chicago and London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 2000, by permission at Digital Commons, University of Nebraska {{DEFAULTSORT:Becher, Johannes R. 1891 births 1958 deaths Writers from Munich People from the Kingdom of Bavaria Independent Social Democratic Party politicians Communist Party of Germany politicians Members of the Central Committee of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany Government ministers of East Germany Members of the Provisional Volkskammer Members of the 1st Volkskammer Members of the 2nd Volkskammer Cultural Association of the GDR members National Committee for a Free Germany members 20th-century German novelists German Communist writers German Communist poets East German poets East German writers German Expressionist writers German male novelists German-language poets German poets National anthem writers Refugees from Nazi Germany in the Soviet Union Stalin Peace Prize recipients Recipients of the National Prize of East Germany Recipients of the Patriotic Order of Merit in silver German magazine founders