Johann von Klenau on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Johann Josef Cajetan Graf von Klenau, Freiherr von Janowitz ( cs, Jan hrabě z Klenové, svobodný pán z Janovic; 13 April 1758 – 6 October 1819) was a field marshal in the

Johann Josef Cajetan von Klenau und Janowitz was born into an old Bohemian nobile family at Benatek Castle in the Habsburg province of

Johann Josef Cajetan von Klenau und Janowitz was born into an old Bohemian nobile family at Benatek Castle in the Habsburg province of

At Handschuhsheim, Klenau commanded a mounted brigade that included the six squadrons of the 4th Cuirassiers Regiment ''Hohenzollern'', two squadrons of the 3rd Dragoon Regiment ''Kaiser'', six squadrons of the 44th Hussar regiment ''Szeckler'', and four squadrons of the French ''

At Handschuhsheim, Klenau commanded a mounted brigade that included the six squadrons of the 4th Cuirassiers Regiment ''Hohenzollern'', two squadrons of the 3rd Dragoon Regiment ''Kaiser'', six squadrons of the 44th Hussar regiment ''Szeckler'', and four squadrons of the French ''

"Klenau"

At Handschuhsheim, as he had earlier at Zemon, Klenau demonstrated his "higher military calling," establishing himself as an intrepid, tenacious, and quick-thinking field officer.

In 1796, Klenau commanded the advance guard of Peter Quasdanovich's right column in northern Italy. As the column descended from the Alps at the city of

In 1796, Klenau commanded the advance guard of Peter Quasdanovich's right column in northern Italy. As the column descended from the Alps at the city of

(''ADB''). Following the Austrian loss at the

Other factors contributed to the rising tensions. On his way to

Other factors contributed to the rising tensions. On his way to

The

The

''The 1799 Campaign in Italy: Klenau and Ott Vanguards and the Coalition's Left Wing April–June 1799''

Klenau took possession of the town on 21 May, and garrisoned it with a light battalion. The Jewish residents of Ferrara paid 30,000 ducats to prevent the pillage of the city by Klenau's forces; this was used to pay the wages of Gardani's troops. Although Klenau held the town, the French still possessed the town's fortress. After making the standard request for surrender at 0800, which was refused, Klenau ordered a barrage from his mortars and howitzers. After two Magazine (artillery), magazines caught fire, the commandant was summoned again to surrender; there was some delay, but a flag of truce was sent at 2100, and the capitulation was concluded at 0100 the next day. Upon taking possession of the fortress, Klenau found 75 new artillery pieces, plus ammunition and six months' worth of provisions. The peasant uprisings pinned down the French and, by capturing Ferrara, Klenau helped to isolate the other French-held fortresses from patrols, reconnaissance, and relief and supply forces. This made the fortresses and their garrisons vulnerable to Alexander Suvorov, Suvorov's main force, operating in the

"General der Kavallerie Graf von Klenau"

Stockach, at the western tip of

The campaign began in October, with several clashes in

The campaign began in October, with several clashes in

Both sides lost close to 28,000 men, to wounds and death. For Napoleon, whose force was smaller, the losses were more costly. For Charles, the victory, which occurred within visual range of the Vienna ramparts, won him support from the hawks, or the pro-war party, in the Hofburg Imperial Palace, Hofburg. The Austrian victory at Aspern-Essling proved that Napoleon could be beaten. His force had been divided (Davout's corps had never made it over the Danube), and Napoleon had underestimated the Austrian strength of force and, more importantly, the tenacity the Austrians showed in situations like that of Essling, when Klenau marched his force across open country under enemy fire. After Aspern-Essling, Napoleon revised his opinion of the Austrian soldier.

Both sides lost close to 28,000 men, to wounds and death. For Napoleon, whose force was smaller, the losses were more costly. For Charles, the victory, which occurred within visual range of the Vienna ramparts, won him support from the hawks, or the pro-war party, in the Hofburg Imperial Palace, Hofburg. The Austrian victory at Aspern-Essling proved that Napoleon could be beaten. His force had been divided (Davout's corps had never made it over the Danube), and Napoleon had underestimated the Austrian strength of force and, more importantly, the tenacity the Austrians showed in situations like that of Essling, when Klenau marched his force across open country under enemy fire. After Aspern-Essling, Napoleon revised his opinion of the Austrian soldier.

As a consequence, Austria withdrew from the Coalition. Although France had not completely defeated them, the Treaty of Schönbrunn, signed on 14 October 1809, imposed a heavy political, territorial, and economic price. France received Duchy of Carinthia, Carinthia, Carniola, and the Adriatic ports, while Galicia (Eastern Europe), Galicia was given to France's ally Poland. The Archbishopric of Salzburg, Salzburg area went to the French ally,

As a consequence, Austria withdrew from the Coalition. Although France had not completely defeated them, the Treaty of Schönbrunn, signed on 14 October 1809, imposed a heavy political, territorial, and economic price. France received Duchy of Carinthia, Carinthia, Carniola, and the Adriatic ports, while Galicia (Eastern Europe), Galicia was given to France's ally Poland. The Archbishopric of Salzburg, Salzburg area went to the French ally,

By waiting one day, the Coalition lost the advantage. As the Coalition assaulted the southern suburbs of the city, Napoleon arrived from the north and west with the Imperial Guard (Napoleon I), Guard and Marmont's VI Corps, covering in forced marches over three days. The leading elements of Klenau's corps were placed on the army's left flank, separated from the main body by the Weißeritz, flooded after almost a week of rain. Marshal of France, Marshal

By waiting one day, the Coalition lost the advantage. As the Coalition assaulted the southern suburbs of the city, Napoleon arrived from the north and west with the Imperial Guard (Napoleon I), Guard and Marmont's VI Corps, covering in forced marches over three days. The leading elements of Klenau's corps were placed on the army's left flank, separated from the main body by the Weißeritz, flooded after almost a week of rain. Marshal of France, Marshal

"General der Kavallerie Graf von Klenau"

Klenau

(''ADB''). After the death of a relative Major Karl Alexander von Klenau in 1845, the male line of the Klenau family ended. Svoboda. p. 207.

Napoleon Series, Robert Burnham, editor in chief. March 2008. Retrieved 30 October 2009. *

"Klenau, Johann Graf"

in: ''Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie'', herausgegeben von der Historischen Kommission bei der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Band 16 (1882), ab Seite 156, Digitale Volltext-Ausgabe in (Version vom 27. Oktober 2009, 21:33 Uhr UTC). * Arnold, James R. ''Napoleon Conquers Austria: the 1809 campaign for Vienna, 1809''. Westport: Conn: Praeger, 1995, . * Ashton, John. ''English caricature and satire on Napoleon I''. London: Chatto & Windus, 1888. * Atkinson, Christopher Thomas. ''A history of Germany, 1715–1815.'' London: Methuen, 1908. * Bernau, Friedrich. ''Studien und Materialien zur Specialgeschichte und Heimatskunde des deutschen Sprachgebiets in Böhmen und Mähren''. Prag: J.G. Calve, 1903. * T. C. W. Blanning, Blanning, Timothy. ''The French Revolutionary Wars''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996, . * Boué, Gilles. ''The Battle of Essling: Napoleon's first defeat?'' Alan McKay, Translator. Elkar, Spain: Histoire & Collectgions, 2008. . * Boycott-Brown, Martin. ''The Road to Rivoli.'' London: Cassell & Co., 2001. . * Bruce, Robert B. et al. ''Fighting techniques of the Napoleonic Age, 1792–1815''. New York: Thomas Dunne Books, St. Martin's Press, 2008, 978-0312375874 * Castle, Ian

''The Battle of Wagram''

The Napoleon Foundation 2009. Also found in ''Zusammenfassung der Beitraege zum Napoleon Symposium "Feldzug 1809"'', Vienna: Heeresgeschichtlichen Museum, 2009, pp. 191–199. * David G. Chandler, Chandler, David. ''The Campaigns of Napoleon.'' New York: Macmillan, 1966. . * Haan, Hermann. ''Die Habsburger, Ein biographisches Lexikon''. München: Piper 1988. * Dill, Marshall. ''Germany: a modern history''. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1970. ASIN B000NW7BFM * Dyer, Thomas Henry. ''Modern Europe from the fall of Constantinople to the establishment of the German Empire, A.D. 1453–1871.'' London: G. Bell & Sons, 1877. * Ebert, Jens-Florian. "Klenau". Die Österreichischen Generäle 1792–1815. Napoleon Online.DE. Retrieved 15 October 2009. Retrieved 23 October 2009. * Feller, François-Xavier and François Marie Pérennès. ''Biographie universelle, ou Dictionnaire historique des hommes qui se sont fait un nom par leur talens, leur génie ...'', Paris: Éditeurs Gauthier frères, 1834. Volume 4. * Fremont-Barnes, Gregory. ''The Napoleonic Wars: the rise and fall of an empire.'' Oxford: Osprey, 2004, . * Gates, David. ''The Napoleonic Wars 1803–1815''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997, . * Gill, John. ''Thunder on the Danube Napoleon's Defeat of the Habsburgs,'' Volume 1. London: Frontline Books, 2008, . * Heermannm, Norbert (or Enoch), Johann Matthäus Klimesch, and Václav Březan. ''Norbert Heermann's Rosenberg'sche chronik''. Prag, Köngl. Böhmische gesellschaft der wissenschaften, 1897 * Herold, Stephen

The Austrian Army in 1812.

In

Le Societé Napoléonienne.

1996–2003. Retrieved 30 December 2009. * Hicks, Peter

''The Battle of Aspern-Essling''.History of Two Empires Reading Room

Napoleon Foundation, 2008. Retrieved 9 December 2009. * Hochedlinger, Michael. ''Austria's Wars of Emergence 1683–1797''. London: Pearson, 2003, . * Hofschroer, Peter, M. Townsend, et al.

Napoleon, His Army and Enemies. Retrieved 7 December 2009. * Hirtenfeld, Jaromir. ''Der militär-Maria-Theresien-Orden und seine Mitglieder: nach authentischen Quellen bearbeitet.'' Wien: Hofdruckerie, 1857 * Frederick Kagan, Kagan, Frederick W. ''The End of the Old Order''. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press 2006, . * Michael Leggiere, Leggiere, Michael V. "From Berlin to Leipzig: Napoleon's Gamble in North Germany, 1813." ''The Journal of Military History'', Vol. 67, No. 1 (January 2003), pp. 39–84. * Marcellin Marbot, Marbot, Jean-Baptiste Antoine Marcellin, ''The Memoirs of General Baron De Marbot'', Volume II, Chapter 23, no pagination. Electronic book widely available. * Menzel, Wolfgang. ''Germany from the Earliest Period''. Mrs. George Horrocks, trans. 4th German edition, volume 3, London: Bohn, 1849. * Naulet, Frédéric. ''Wagram, 5–6 juillet 1809, Une victoire chèrement acquise'', Collections Grandes Batailles, Napoléon Ier Éditions, 2009. * Perkow, Ursula

"Der Schlacht bei Handshuhsheim"

''KuK Militärgeschichte''. Lars-Holger Thümmler, editor. 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2009. * Francis Loraine Petre, Petre, F. Loraine. ''Napoleons̓ last campaign in Germany, 1813.'' London: John Lane Co., 1912. * Pivka, Otto von. ''Armies of the Napoleonic Era''. New York: Taplinger Publishing, 1979. * Ramsay Weston Phipps, Phipps, Ramsay Weston. ''The Armies of the First French Republic'', volume 5: The armies of the Rhine in Switzerland, Holland, Italy, Egypt and the coup d'état of Brumaire, 1797–1799, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1939. * Gunther E. Rothenberg, Rothenberg, Gunther E. ''Napoleon's Great Adversary: Archduke Charles and the Austrian Army 1792–1814''. Spellmount: Stroud, (Gloucester), 2007. . * Alan Sked, Sked, Alan. "Historians, the Nationality Question, and the Downfall of the Habsburg Empire." ''Transactions of the Royal Historical Society,'' Fifth Series, Vol. 31, (1981), pp. 175–193. * Digby Smith, Smith, Digby. ''The Napoleonic Wars Data Book.'' London: Greenhill, 1998. * _____.

Klenau"Mesko""Quosdanovich"

Leopold Kudrna and Digby Smith (compilers). ''A biographical dictionary of all Austrian Generals in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, 1792–1815''. The Napoleon Series, Robert Burnham, editor in chief. April 2008 version. Retrieved 19 October 2009. * _____. ''Charge! Great cavalry charges of the Napoleonic Wars.'' London: Greenhill, 2007. * _____. ''1813: Leipzig Napoleon and the Battle of Nations.'' PA: Stackpole Books, 2001, . * Vann, James Allen. "Habsburg Policy and the Austrian War of 1809." ''Central European History,'' Vol. 7, No. 4 (December 1974), pp. 291–310, pp. 297–298. * Völkerschlacht-Gedenksteine an vielen Stellen in und um Leipzig

. Farbfotos: www-itoja-de, Nov.2007. Retrieved 28 November 2009. * Young, John D.D. ''A History of the Commencement, Progress, and Termination of the Late War between Great Britain and France which continued from the first day of February 1793 to the first of October 1801'', in two volumes. Edinburg: Turnbull, 1802, vol. 2. {{DEFAULTSORT:Klenau, Johann Von 1758 births 1819 deaths 18th-century Austrian people 18th-century Bohemian people 19th-century Austrian people 19th-century Czech people Austrian Empire commanders of the Napoleonic Wars Austrian Empire military leaders of the French Revolutionary Wars Austrian generals 18th-century Austrian military personnel Austrian people of German Bohemian descent German Bohemian people Bohemian nobility Military leaders of the French Revolutionary Wars People from Benátky nad Jizerou Czech military leaders 19th-century Austrian military personnel Commanders Cross of the Military Order of Maria Theresa Recipients of the Order of St. Vladimir, 2nd class

Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

army. Klenau, the son of a Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

n noble, joined the Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

military as a teenager and fought in the War of Bavarian Succession

The War of the Bavarian Succession (; 3 July 1778 – 13 May 1779) was a dispute between the Austrian Habsburg monarchy and an alliance of Saxony and Prussia over succession to the Electorate of Bavaria after the extinction of the Bavarian bran ...

against Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

, Austria's wars

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular ...

with the Ottoman Empire, the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted French First Republic, France against Ki ...

, and the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, in which he commanded a corps in several important battles.

In the early years of the French Revolutionary Wars, Klenau distinguished himself at the Wissembourg lines, and led a battle-winning charge at Handschuhsheim in 1795. As commander of the Coalition's left flank in the Adige

The Adige (; german: Etsch ; vec, Àdexe ; rm, Adisch ; lld, Adesc; la, Athesis; grc, Ἄθεσις, Áthesis, or , ''Átagis'') is the second-longest river in Italy, after the Po. It rises near the Reschen Pass in the Vinschgau in the pro ...

campaign in northern Italy in 1799, he was instrumental in isolating the French-held fortresses on the Po River

The Po ( , ; la, Padus or ; Ligurian language (ancient), Ancient Ligurian: or ) is the longest river in Italy. It flows eastward across northern Italy starting from the Cottian Alps. The river's length is either or , if the Maira (river), Mair ...

by organizing and supporting a peasant uprising in the countryside. Afterward, Klenau became the youngest lieutenant field marshal

Lieutenant field marshal, also frequently historically field marshal lieutenant (german: Feldmarschall-Leutnant, formerly , historically also and, in official Imperial and Royal Austrian army documents from 1867 always , abbreviated ''FML''), wa ...

in the history of the Habsburg military.

As a corps commander, Klenau led key elements of the Austrian army in its victory at Aspern-Esslingen and its defeat at Wagram

Deutsch-Wagram (literally "German Wagram", ), often shortened to Wagram, is a village in the Gänserndorf District, in the state of Lower Austria, Austria. It is in the Marchfeld Basin, close to the Vienna city limits, about 15 km (9 mi) northeas ...

, where his troops covered the retreat of the main Austrian force. He commanded the IV Corps at the 1813 Battle of Dresden

The Battle of Dresden (26–27 August 1813) was a major engagement of the Napoleonic Wars. The battle took place around the city of Dresden in modern-day Germany. With the recent addition of Austria, the Sixth Coalition felt emboldened in t ...

and again at the Battle of Nations

The Battle of Leipzig (french: Bataille de Leipsick; german: Völkerschlacht bei Leipzig, ); sv, Slaget vid Leipzig), also known as the Battle of the Nations (french: Bataille des Nations; russian: Битва народов, translit=Bitva ...

at Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as wel ...

, where he prevented the French from outflanking the main Austrian force on the first day of the engagement. After the Battle of Nations, Klenau organized and implemented the successful Dresden blockade and negotiated the French capitulation there. In the 1814–15 campaign, he commanded the ''Corps Klenau'' of the Army of Italy. After the war in 1815, Klenau was appointed commanding general in Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The me ...

and Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

. He died in 1819.

Family and early career

Johann Josef Cajetan von Klenau und Janowitz was born into an old Bohemian nobile family at Benatek Castle in the Habsburg province of

Johann Josef Cajetan von Klenau und Janowitz was born into an old Bohemian nobile family at Benatek Castle in the Habsburg province of Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

on 13 April 1758. The family of Klenau dates to the fifteenth century, and the family of Janowitz to the fourteenth. The family name of Klenau regularly appears in records after the sixteenth century. The Klenau family was one of the oldest dynasties in Bohemia, and many of the noble families of Bohemia have sprung from marriages into the Klenau line. The original name of the family was Przibik, with the predicate ''von Klenowa''. The family was raised to the baronetcy in 1623 with the certificate granted to one Johann von Klenowa and, in 1629, to his son, Wilhelm. The Imperial councilor and judge in Regensburg, Wilhelm von Klenau, was raised to comital

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility. Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty''. New York: ...

status in 1630, and to the status of ''Reichsgraf'', or imperial count, in 1633.

Johann Klenau entered the 47th Infantry Regiment ''Ellrichshausen'' in 1774, at the age of 17, and became a second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

in 1775. After transferring to a ''Chevauleger'' regiment as a ''Rittmeister

__NOTOC__

(German and Scandinavian for "riding master" or "cavalry master") is or was a military rank of a commissioned cavalry officer in the armies of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Scandinavia, and some other countries. A ''Rittmeister'' is typic ...

'', or captain of cavalry, Klenau fought in the short War of the Bavarian Succession

The War of the Bavarian Succession (; 3 July 1778 – 13 May 1779) was a dispute between the Austrian Habsburg monarchy and an alliance of Saxony and Prussia over succession to the Electorate of Bavaria after the extinction of the Bavarian br ...

, also known as the Potato War. Most of this conflict occurred in Bohemia (part of the modern Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, it is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the southeast. The ...

) from 1778 to 1779, between the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy (german: Habsburgermonarchie, ), also known as the Danubian monarchy (german: Donaumonarchie, ), or Habsburg Empire (german: Habsburgerreich, ), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities ...

, Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a landlocked state of ...

, Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

and Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

. The war had no battles, but was instead a series of skirmishes and raids, making it the ideal situation for a captain of light cavalry. In their raids, forces from both sides sought to confiscate or destroy the other's provisions, fodder, and materiel.

In the Austro–Turkish War (1787–1791), one of the House of Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

's many 18th-century wars with the Ottoman Empire, Klenau served in the 26th Dragoon Regiment ''Toscana'', and later transferred to the 1st Dragoon Regiment ''Kaiser''. His regiment repulsed an attack of superior numbers of Ottoman forces on 28 September 1788, at Zemun

Zemun ( sr-cyrl, Земун, ; hu, Zimony) is a municipality in the city of Belgrade. Zemun was a separate town that was absorbed into Belgrade in 1934. It lies on the right bank of the Danube river, upstream from downtown Belgrade. The developme ...

, near Belgrade, for which he received a personal commendation and earned his promotion to major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

. In his early military career Klenau demonstrated, not only at Zemun but also in the earlier skirmishing and raids of 1778 and 1779, the attributes required of a successful cavalry officer: the military acumen to evaluate a situation, the flexibility to adjust his plans on a moment's notice, and the personal courage to take the same risks he demanded of his men.

French Revolutionary Wars

Background

Initially, the rulers of Europe considered the 1789revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

in France as an affair between the French king and his subjects, and not a matter in which they should interfere. However, as the rhetoric grew more strident after 1790, the European monarchs began to view the French upheavals with alarm. Among the concerned monarchs were the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II, who feared for the life and well-being of his sister, the Queen of France, Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette Josèphe Jeanne (; ; née Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last queen of France before the French Revolution. She was born an archduchess of Austria, and was the penultimate child a ...

. In August 1791, in consultation with French ''émigré

An ''émigré'' () is a person who has emigrated, often with a connotation of political or social self-exile. The word is the past participle of the French ''émigrer'', "to emigrate".

French Huguenots

Many French Huguenots fled France followi ...

'' nobles and Frederick William II of Prussia, he issued the Declaration of Pillnitz

The Declaration of Pillnitz was a statement of five sentences issued on 27 August 1791 at Pillnitz Castle near Dresden (Saxony) by Frederick William II of Prussia and the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II who was Marie Antoinette's broth ...

, in which they declared the interest of the monarchs of Europe as one with the interests of Louis XVI

Louis XVI (''Louis-Auguste''; ; 23 August 175421 January 1793) was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. He was referred to as ''Citizen Louis Capet'' during the four months just before he was ...

and his family. They threatened ambiguous, but quite serious, consequences if anything should happen to the royal family.

The French Republican position became increasingly difficult. Compounding problems in international relations, French ''émigrés'' agitated for support of a counter-revolution. From their base in Koblenz

Koblenz (; Moselle Franconian language, Moselle Franconian: ''Kowelenz''), spelled Coblenz before 1926, is a German city on the banks of the Rhine and the Moselle, a multi-nation tributary.

Koblenz was established as a Roman Empire, Roman mili ...

, adjacent to the French–German border, they sought direct support for military intervention from the royal houses of Europe, and raised an army. On 20 April 1792, the French National Convention

The National Convention (french: link=no, Convention nationale) was the parliament of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for the rest of its existence during the French Revolution, following the two-year National ...

declared war on Austria and its allies. In this War of the First Coalition

The War of the First Coalition (french: Guerre de la Première Coalition) was a set of wars that several European powers fought between 1792 and 1797 initially against the constitutional Kingdom of France and then the French Republic that suc ...

(1792–1798), France ranged itself against most of the European states sharing land or water borders with her. Portugal and the Ottoman Empire also joined the alliance against France.

Klenau and the War of the First Coalition

On 12 February 1793, Klenau received his promotion tolieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

in a Lancer regiment, and joined the Austrian force in the Rhineland, serving under General of Cavalry Count Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser

Dagobert Sigismund, Count von Wurmser (7 May 1724 – 22 August 1797) was an Austrian field marshal during the French Revolutionary Wars. Although he fought in the Seven Years' War, the War of the Bavarian Succession, and mounted several succes ...

. He was captured later in the spring near the town of Offenbach, but was freed unexpectedly by two Austrian Hussars from the 17th Regiment ''Archduke Alexander Leopold'', who came upon him and his captors. At the first Battle of Wissembourg, Klenau commanded a brigade in Friedrich, Baron von Hotze's 3rd Column on 13 October 1793, during which the Habsburg force stormed the earthen ramparts held by the French.

By the terms of the Peace of Basel

The Peace of Basel of 1795 consists of three peace treaties involving France during the French Revolution (represented by François de Barthélemy).

*The first was with Prussia (represented by Karl August von Hardenberg) on 5 April;

*The sec ...

(22 July 1795), the Prussian army was to leave the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

and Main

Main may refer to:

Geography

* Main River (disambiguation)

**Most commonly the Main (river) in Germany

* Main, Iran, a village in Fars Province

*"Spanish Main", the Caribbean coasts of mainland Spanish territories in the 16th and 17th centuries

...

river valleys; as it did so, the French quickly overran these territories. On 20 September, the fortress at Mannheim

Mannheim (; Palatine German: or ), officially the University City of Mannheim (german: Universitätsstadt Mannheim), is the second-largest city in the German state of Baden-Württemberg after the state capital of Stuttgart, and Germany's 2 ...

surrendered to the French without firing a shot. Mannheim had been garrisoned by a Bavarian commander, Lieutenant General Baron von Belderbusch, and several battalions of Bavarian grenadiers, fusiliers, and guard regiments, plus six companies of artillery. A small Austrian force augmented the Bavarian contingent. At the same time, further north, the fortified town of Düsseldorf

Düsseldorf ( , , ; often in English sources; Low Franconian and Ripuarian: ''Düsseldörp'' ; archaic nl, Dusseldorp ) is the capital city of North Rhine-Westphalia, the most populous state of Germany. It is the second-largest city in th ...

, also garrisoned by Bavarians, capitulated to the French. With these capitulations, the French controlled the Rhine crossings at Düsseldorf and at the junction of the Rhine and the Main rivers. To maintain contact with the forces on their flanks, the Austrian commanders, outraged at this '' fait accompli'', had to withdraw across the Main river.

The nearby city of Heidelberg

Heidelberg (; Palatine German language, Palatine German: ''Heidlberg'') is a city in the States of Germany, German state of Baden-Württemberg, situated on the river Neckar in south-west Germany. As of the 2016 census, its population was 159,914 ...

, further south of the Main on the Neckar

The Neckar () is a river in Germany, mainly flowing through the southwestern state of Baden-Württemberg, with a short section through Hesse. The Neckar is a major right tributary of the Rhine. Rising in the Schwarzwald-Baar-Kreis near Schwenn ...

River, appeared to be the next French target. Lieutenant Field Marshal Peter Quasdanovich

Peter Vitus Freiherr von Quosdanovich ( Croatian: Petar Vid Gvozdanović; 12 June 1738 – 13 August 1802) was a nobleman and general of the Habsburg monarchy of Croatian descent. He achieved the rank of Feldmarschall-Lieutenant and was awarded t ...

, who had remained in the region between Mannheim and Heidelberg, used a hastily enhanced abatis

An abatis, abattis, or abbattis is a field fortification consisting of an obstacle formed (in the modern era) of the branches of trees laid in a row, with the sharpened tops directed outwards, towards the enemy. The trees are usually interlaced ...

to establish a defensive line at the sleepy country village of Handschuhsheim, east of the city of Heidelberg. The French force of two divisions—about 12,000 men—outnumbered the 8,000 defenders, and the position seemed untenable.

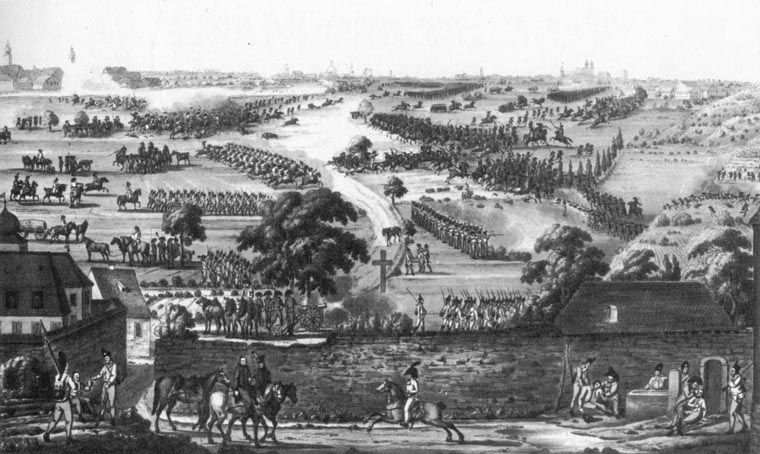

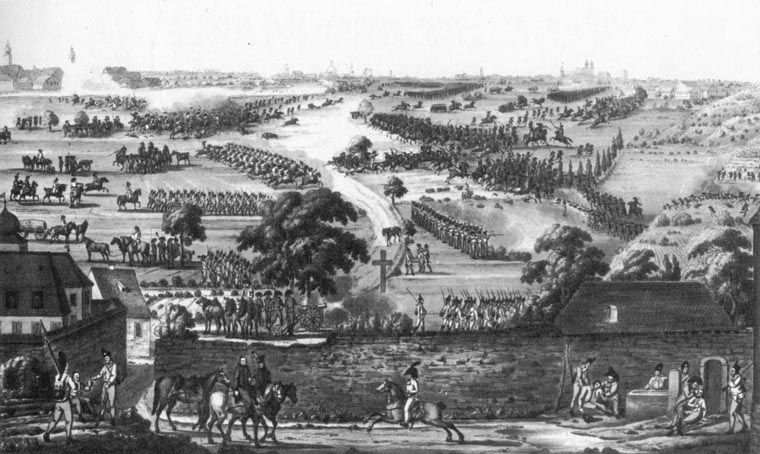

Klenau's charge

At Handschuhsheim, Klenau commanded a mounted brigade that included the six squadrons of the 4th Cuirassiers Regiment ''Hohenzollern'', two squadrons of the 3rd Dragoon Regiment ''Kaiser'', six squadrons of the 44th Hussar regiment ''Szeckler'', and four squadrons of the French ''

At Handschuhsheim, Klenau commanded a mounted brigade that included the six squadrons of the 4th Cuirassiers Regiment ''Hohenzollern'', two squadrons of the 3rd Dragoon Regiment ''Kaiser'', six squadrons of the 44th Hussar regiment ''Szeckler'', and four squadrons of the French ''émigré

An ''émigré'' () is a person who has emigrated, often with a connotation of political or social self-exile. The word is the past participle of the French ''émigrer'', "to emigrate".

French Huguenots

Many French Huguenots fled France followi ...

'' regiment ''Allemand''. On 24 September 1795, seeing the French, with five battalions and a regiment of Chasseurs overwhelming the troops of General Adam Bajalics von Bajahaza, Klenau quickly organized his own brigade into three columns and attacked. In a battle-winning charge, Klenau's brigade (approximately 4,000 men) dispersed the French divisions of Charles Pichegru's Army of the Upper Rhine, under the command of General of Division Georges Joseph Dufour. His cavalry caught Dufour's entire division in the open, dispersed Dufour's six squadrons of Chasseurs, and cut down Dufour's infantry. With a loss of 193 men and 54 horses, the Austrians inflicted over 1,500 French casualties, including 1,000 killed; they also captured eight guns, nine ammunition caissons and their teams, and General Dufour himself. In the action, General of Brigade Dusirat was wounded, as was Dufour before his capture. Additional Austrian losses included 35 men and 58 horses killed, six officers, 144 men and 78 horses wounded, and two men and three horses missing. For his role in this exploit, Klenau was promoted to colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

and awarded the Knight's Cross of the Military Order of Maria Theresa.Kudrna and Smith"Klenau"

At Handschuhsheim, as he had earlier at Zemon, Klenau demonstrated his "higher military calling," establishing himself as an intrepid, tenacious, and quick-thinking field officer.

Action in the Italian theater

In 1796, Klenau commanded the advance guard of Peter Quasdanovich's right column in northern Italy. As the column descended from the Alps at the city of

In 1796, Klenau commanded the advance guard of Peter Quasdanovich's right column in northern Italy. As the column descended from the Alps at the city of Brescia

Brescia (, locally ; lmo, link=no, label= Lombard, Brèsa ; lat, Brixia; vec, Bressa) is a city and ''comune'' in the region of Lombardy, Northern Italy. It is situated at the foot of the Alps, a few kilometers from the lakes Garda and Iseo ...

, reconnaissance found the local French garrison unprepared. At midnight, Klenau led two squadrons of the 8th Hussar Regiment ''Wurmser'' (named for its Colonel-Proprietor Dagobert von Wurmser), a battalion of the 37th Infantry Regiment ''De Vins'', and one company of the Mahony Jäger. With their approach masked by fog and darkness, the small force surprised the Brescia garrison on the morning of 30 July, capturing not only the 600–700 French soldiers stationed there, but also three officials of the French Directory: Jean Lannes

Jean Lannes, 1st Duke of Montebello, Prince of Siewierz (10 April 1769 – 31 May 1809), was a French military commander and a Marshal of the Empire who served during both the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. He was one of Napoleon's ...

, Joachim Murat

Joachim Murat ( , also , ; it, Gioacchino Murati; 25 March 1767 – 13 October 1815) was a French military commander and statesman who served during the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars. Under the French Empire he received the ...

, and François Étienne de Kellermann

François Étienne de Kellermann, 2nd Duke of Valmy (4 August 1770 – 2 June 1835) was a French cavalry general noted for his daring and skillful exploits during the Napoleonic Wars. He was the son of François Christophe de Kellermann and the fat ...

. However, within two days, Klenau's force had to face Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

and 12,000 Frenchmen; his small advance guard was quickly pushed out of Brescia on 1 August. At the subsequent Battle of Lonato

The Battle of Lonato was fought on 3 and 4 August 1796 between the French Army of Italy under General Napoleon Bonaparte and a corps-sized Austrian column led by Lieutenant General Peter Quasdanovich. A week of hard-fought actions that began ...

of 2–3 August 1796, the French forced Quasdanovich's column to withdraw into the mountains. This isolated Quasdanovich's force from Wurmser's main army by Lake Garda

Lake Garda ( it, Lago di Garda or ; lmo, label=Eastern Lombard, Lach de Garda; vec, Ƚago de Garda; la, Benacus; grc, Βήνακος) is the largest lake in Italy.

It is a popular holiday location in northern Italy, about halfway between ...

, and freed the French to concentrate on the main force at Castiglione delle Stiviere

Castiglione delle Stiviere ( Upper Mantovano: ) is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Mantua, in Lombardy, Italy, northwest of Mantua by road.

History

The town's castle was home to a cadet branch of the House of Gonzaga, headed by the M ...

, further south; Bonaparte's victory at the Battle of Castiglione

The Battle of Castiglione saw the French Army of Italy under General Napoleon Bonaparte attack an army of the Habsburg monarchy led by ''Feldmarschall'' Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser on 5 August 1796. The outnumbered Austrians were defeated ...

forced Wurmser across the Mincio River

The Mincio (; Latin: Mincius, Ancient Greek: Minchios, ''Μίγχιος'', Lombard: Mens, Venetian: Menzo) is a river in the Lombardy region of northern Italy.

The river is the main outlet of Lake Garda. It is a part of the ''Sarca-Mincio'' ...

, and allowed the French to return to the siege of Mantua.

By early September, Klenau's force had rejoined Wurmser's column and fought at the Battle of Bassano

The Battle of Bassano was fought on 8 September 1796, during the French Revolutionary Wars, in the territory of the Republic of Venice, between a French army under Napoleon Bonaparte and Austrian forces led by Count Dagobert von Wurmser. The ...

on 8 September. Here, the Austrians were outnumbered almost two to one by the French. As the Austrian army retreated, Bonaparte ordered a pursuit that caused the Austrians to abandon their artillery and baggage. Most of the third battalion of the 59th ''Jordis'', and the first battalion of the Border Infantry Banat were captured and these units ceased to exist after this battle. The Austrians lost 600 killed and wounded, and 2,000 captured, plus lost 30 guns, eight colors, and 200 limbers and ammunition waggons. Klenau was with Wurmser's column again as it fought its way to besieged Mantua

Mantua ( ; it, Mantova ; Lombard language, Lombard and la, Mantua) is a city and ''comune'' in Lombardy, Italy, and capital of the Province of Mantua, province of the same name.

In 2016, Mantua was designated as the Italian Capital of Culture ...

and he participated in the combat at La Favorita

''La favorite'' (''The Favourite'', sometimes referred to by its Italian title: ''La favorita'') is a grand opera in four acts by Gaetano Donizetti to a French-language libretto by Alphonse Royer and Gustave Vaëz, based on the play ''Le comt ...

near there on 15 September. This was the second attempt to relieve the fortress; as the Austrians withdrew from the battle, they retreated into Mantua itself, and from 15 September until 2 February 1797, Klenau was trapped in the fortress while the city was besieged.Klenau(''ADB''). Following the Austrian loss at the

Battle of Rivoli

The Battle of Rivoli (14–15 January 1797) was a key victory in the French campaign in Italy against Austria. Napoleon Bonaparte's 23,000 Frenchmen defeated an attack of 28,000 Austrians under General of the Artillery Jozsef Alvinczi, e ...

, north of Mantua, on 14–15 January 1797, when clearly there would be no Austrian relief for Mantua, Klenau negotiated conditions of surrender with French General Jean Sérurier, although additional evidence suggests that Bonaparte was present and dictated far more generous terms than Klenau expected. When the garrison capitulated in February, Klenau co-signed the document with Wurmser.

Peace and the Congress of Rastatt

Although the Coalition forces—Austria, Russia, Prussia, Great Britain, Sardinia, among others—had achieved several victories atVerdun

Verdun (, , , ; official name before 1970 ''Verdun-sur-Meuse'') is a large city in the Meuse department in Grand Est, northeastern France. It is an arrondissement of the department.

Verdun is the biggest city in Meuse, although the capital ...

, Kaiserslautern

Kaiserslautern (; Palatinate German: ''Lautre'') is a city in southwest Germany, located in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate at the edge of the Palatinate Forest. The historic centre dates to the 9th century. It is from Paris, from Frankfur ...

, Neerwinden

Neerwinden is a village in Belgium in the province of Flemish Brabant, a few miles southeast of Tienen. It is now part of the municipality of Landen.

The village gave its name to two great battles. The first battle was fought in 1693 between t ...

, Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main (river), Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-we ...

, Amberg

Amberg () is a town in Bavaria, Germany. It is located in the Upper Palatinate, roughly halfway between Regensburg and Bayreuth. In 2020, over 42,000 people lived in the town.

History

The town was first mentioned in 1034, at that time under t ...

and Würzburg

Würzburg (; Main-Franconian: ) is a city in the region of Franconia in the north of the German state of Bavaria. Würzburg is the administrative seat of the ''Regierungsbezirk'' Lower Franconia. It spans the banks of the Main River.

Würzburg is ...

, in Italy the Coalition's achievements were more limited. In northern Italy, despite the presence of the most experienced of the Austrian generals—Dagobert Wurmser—the Austrians could not lift the siege at Mantua, and the efforts of Napoleon in northern Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

pushed Austrian forces to the border of Habsburg lands. Napoleon dictated a cease-fire at Leoben

Leoben () is a Styrian city in central Austria, located on the Mur river. With a population of about 25,000 it is a local industrial centre and hosts the University of Leoben, which specialises in mining. The Peace of Leoben, an armistice bet ...

on 17 April 1797, which led to the formal peace treaty, the Treaty of Campo Formio

The Treaty of Campo Formio (today Campoformido) was signed on 17 October 1797 (26 Vendémiaire VI) by Napoleon Bonaparte and Count Philipp von Cobenzl as representatives of the French Republic and the Austrian monarchy, respectively. The treat ...

, which went into effect on 17 October 1797.

The treaty called for meetings between the involved parties to work out the exact territorial and remunerative details. These were to be convened at a small town in the upper Rhine valley, Rastatt

Rastatt () is a town with a Baroque core, District of Rastatt, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is located in the Upper Rhine Plain on the Murg river, above its junction with the Rhine and has a population of around 50,000 (2011). Rastatt was a ...

, close to the French border. The primary combatants of the First Coalition, France and Austria, were highly suspicious of each other's motives, and the Congress quickly derailed in a mire of intrigue and diplomatic posturing. The French demanded more territory than originally agreed. The Austrians were reluctant to cede the designated territories. The Rastatt delegates could not, or would not, orchestrate the transfer of agreed-upon territories to compensate the German princes for their losses. Compounding the Congress's problems, tensions grew between France and most of the First Coalition allies, either separately or jointly. Ferdinand of Naples refused to pay agreed-upon tribute to France, and his subjects followed this refusal with a rebellion. The French invaded Naples and established the Parthenopean Republic

The Parthenopean Republic ( it, Repubblica Partenopea, french: République Parthénopéenne) or Neapolitan Republic (''Repubblica Napoletana'') was a short-lived, semi-autonomous republic located within the Kingdom of Naples and supported by the ...

. A republican uprising in the Swiss cantons, encouraged by the French Republic which offered military support, led to the overthrow of the Swiss Confederation

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

and the establishment of the Helvetic Republic.

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

in 1798, Napoleon had stopped on the Island of Malta and forcibly removed the Hospitallers

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic Church, Catholic Military ord ...

from their possessions. This angered Paul, Tsar of Russia, who was the honorary head of the Order. The French Directory was convinced that the Austrians were conniving to start another war. Indeed, the weaker the French Republic seemed, the more seriously the Austrians, the Neapolitans, the Russians, and the English actually discussed this possibility.

Outbreak of war in 1799

Archduke Charles of Austria

Archduke Charles Louis John Joseph Laurentius of Austria, Duke of Teschen (german: link=no, Erzherzog Karl Ludwig Johann Josef Lorenz von Österreich, Herzog von Teschen; 5 September 177130 April 1847) was an Austrian field-marshal, the third s ...

, arguably among the best commanders of the House of Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, had taken command of the Austrian army in late January. Although Charles was unhappy with the strategy set by his brother, the Holy Roman Emperor Francis II, he had acquiesced to the less ambitious plan to which Francis and his advisers, the Aulic Council

The Aulic Council ( la, Consilium Aulicum, german: Reichshofrat, literally meaning Court Council of the Empire) was one of the two supreme courts of the Holy Roman Empire, the other being the Imperial Chamber Court. It had not only concurrent juri ...

, had agreed: Austria would fight a defensive war and would maintain a continuous defensive line from the southern bank of the Danube, across the Swiss Cantons and into northern Italy. The archduke had stationed himself at Friedberg for the winter, east-south-east of Augsburg

Augsburg (; bar , Augschburg , links=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swabian_German , label=Swabian German, , ) is a city in Swabia, Bavaria, Germany, around west of Bavarian capital Munich. It is a university town and regional seat of the ' ...

. His army settled into cantonments in the environs of Augsburg, extending south along the Lech

Lech may refer to:

People

* Lech (name), a name of Polish origin

* Lech, the legendary founder of Poland

* Lech (Bohemian prince)

Products and organizations

* Lech (beer), Polish beer produced by Kompania Piwowarska, in Poznań

* Lech Poznań, ...

river.

As winter broke in 1799, on 1 March, General Jean-Baptiste Jourdan

Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, 1st Count Jourdan (29 April 1762 – 23 November 1833), was a French military commander who served during the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars. He was made a Marshal of the Empire by Emperor Napoleon I in ...

and his army of 25,000, the Army of the Danube, crossed the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

at Kehl

Kehl (; gsw, label= Low Alemannic, Kaal) is a town in southwestern Germany in the Ortenaukreis, Baden-Württemberg. It is on the river Rhine, directly opposite the French city of Strasbourg, with which it shares some municipal servicesfor exa ...

. Instructed to block the Austrians from access to the Swiss alpine passes, Jourdan planned to isolate the armies of the Coalition in Germany from allies in northern Italy, and prevent them from assisting one another. By crossing the Rhine in early March, Jourdan acted before Charles' army could be reinforced by Austria's Russian allies, who had agreed to send 60,000 seasoned soldiers and their more-seasoned commander, Generalissimo Alexander Suvorov

Alexander Vasilyevich Suvorov (russian: Алекса́ндр Васи́льевич Суво́ров, Aleksándr Vasíl'yevich Suvórov; or 1730) was a Russian general in service of the Russian Empire. He was Count of Rymnik, Count of the Holy ...

. Furthermore, if the French held the interior passes in Switzerland, they could prevent the Austrians from transferring troops between northern Italy and southwestern Germany, and use the routes to move their own forces between the two theaters.

The Army of the Danube advanced through the Black Forest

The Black Forest (german: Schwarzwald ) is a large forested mountain range in the state of Baden-Württemberg in southwest Germany, bounded by the Rhine Valley to the west and south and close to the borders with France and Switzerland. It is t ...

and eventually established a line from Lake Constance

Lake Constance (german: Bodensee, ) refers to three Body of water, bodies of water on the Rhine at the northern foot of the Alps: Upper Lake Constance (''Obersee''), Lower Lake Constance (''Untersee''), and a connecting stretch of the Rhine, ca ...

to the south bank of the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

, centered at the Imperial City

In the Holy Roman Empire, the collective term free and imperial cities (german: Freie und Reichsstädte), briefly worded free imperial city (', la, urbs imperialis libera), was used from the fifteenth century to denote a self-ruling city that ...

of Pfullendorf

Pfullendorf is a small town of about 13,000 inhabitants located north of Lake Constance in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It was a Free Imperial City of the Holy Roman Empire for nearly 600 years.

The town is in the district of Sigmaringen south of ...

in Upper Swabia

Swabia ; german: Schwaben , colloquially ''Schwabenland'' or ''Ländle''; archaic English also Suabia or Svebia is a cultural, historic and linguistic region in southwestern Germany.

The name is ultimately derived from the medieval Duchy of ...

. At the same time, the Army of Switzerland, under command of André Masséna

André Masséna, Prince of Essling, Duke of Rivoli (born Andrea Massena; 6 May 1758 – 4 April 1817) was a French military commander during the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars.Donald D. Horward, ed., trans, annotated, The Fre ...

, pushed toward the Grisons

The Grisons () or Graubünden,Names include:

*german: (Kanton) Graubünden ;

* Romansh:

** rm, label= Sursilvan, (Cantun) Grischun

** rm, label=Vallader, (Chantun) Grischun

** rm, label= Puter, (Chantun) Grischun

** rm, label=Surmiran, (Cant ...

, intending to cut the Austrian lines of communication and relief at the mountain passes by Luziensteig and Feldkirch. The Army of Italy, commanded by Louis Joseph Schérer, had already advanced into northern Italy, to deal with Ferdinand and the recalcitrant Neapolitans.

Campaigns of 1799–1800

At the onset of the 1799 campaign in Italy, Klenau and his 4,500 troops incited and then assisted an uprising of 4,000 or more peasants in the Italian countryside, adjacent to thePo River

The Po ( , ; la, Padus or ; Ligurian language (ancient), Ancient Ligurian: or ) is the longest river in Italy. It flows eastward across northern Italy starting from the Cottian Alps. The river's length is either or , if the Maira (river), Mair ...

, and the subsequent general insurgency pinned down the French on the river's east bank. Klenau's troops, especially some of his Italian-speaking officers, incited peasants against French authority, provided arms and suggested military targets of opportunity, and incorporated the Austrian-armed peasants into their military actions.

Klenau's siege of Ferrara

The

The Ferrara

Ferrara (, ; egl, Fràra ) is a city and ''comune'' in Emilia-Romagna, northern Italy, capital of the Province of Ferrara. it had 132,009 inhabitants. It is situated northeast of Bologna, on the Po di Volano, a branch channel of the main stream ...

fortress had been constructed in the 16th century by Pope Paul V

Pope Paul V ( la, Paulus V; it, Paolo V) (17 September 1550 – 28 January 1621), born Camillo Borghese, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 16 May 1605 to his death in January 1621. In 1611, he honored ...

, built in the style of the Trace italienne

A bastion fort or ''trace italienne'' (a phrase derived from non-standard French, literally meaning ''Italian outline'') is a fortification in a style that evolved during the early modern period of gunpowder when the cannon came to domin ...

, or a star, and it straddled the southwest corner of the town's fortifications. The fortress offered whoever possessed it a strategic point in the region: it was the lynch-pin of the French defense. In spring 1799, it was commanded by Chef-de-brigade Lapointe with a garrison of close to 2,500. On 15 April, Klenau approached the fortress and requested its capitulation. The commander refused. Klenau blockaded the city, leaving a small group of artillery and troops to continue the siege. For the next three days, Klenau patrolled the countryside, capturing the surrounding strategic points of Lagoscuro, Borgoforte and the Mirandola fortress. The besieged garrison made several sorties from the Saint Paul's Gate, which were repulsed by the insurgent peasants. The French attempted two rescues of the beleaguered fortress: In the first, on 24 April, a force of 400 Modenese was repulsed at Mirandola. In the second, General Montrichard tried to raise the city blockade by advancing with a force of 4,000. Finally, at the end of the month, a column of Pierre-Augustin Hulin reached and resupplied the fortress.Acerbi''The 1799 Campaign in Italy: Klenau and Ott Vanguards and the Coalition's Left Wing April–June 1799''

Klenau took possession of the town on 21 May, and garrisoned it with a light battalion. The Jewish residents of Ferrara paid 30,000 ducats to prevent the pillage of the city by Klenau's forces; this was used to pay the wages of Gardani's troops. Although Klenau held the town, the French still possessed the town's fortress. After making the standard request for surrender at 0800, which was refused, Klenau ordered a barrage from his mortars and howitzers. After two Magazine (artillery), magazines caught fire, the commandant was summoned again to surrender; there was some delay, but a flag of truce was sent at 2100, and the capitulation was concluded at 0100 the next day. Upon taking possession of the fortress, Klenau found 75 new artillery pieces, plus ammunition and six months' worth of provisions. The peasant uprisings pinned down the French and, by capturing Ferrara, Klenau helped to isolate the other French-held fortresses from patrols, reconnaissance, and relief and supply forces. This made the fortresses and their garrisons vulnerable to Alexander Suvorov, Suvorov's main force, operating in the

Po River

The Po ( , ; la, Padus or ; Ligurian language (ancient), Ancient Ligurian: or ) is the longest river in Italy. It flows eastward across northern Italy starting from the Cottian Alps. The river's length is either or , if the Maira (river), Mair ...

valley. In the course of the summer, Suvorov's forces took a key position on the Tidone River on 17 June 1799, west of Piacenza, another at the junction of the Trebbia River and the Po, in northern Italy, on 17–20 June 1799, and the town of Novi Ligure on 15 August 1799, southeast of Alessandria on the Tanaro river.

1800 campaign in Swabia

In early 1800, Klenau transferred to the ''K(aiserlich) und K(oeniglich)'' (Imperial and Royal) army of Germany, inSwabia

Swabia ; german: Schwaben , colloquially ''Schwabenland'' or ''Ländle''; archaic English also Suabia or Svebia is a cultural, historic and linguistic region in southwestern Germany.

The name is ultimately derived from the medieval Duchy of ...

, under the command of Feldzeugmeister Pál Kray, Paul, Baron von Kray. The 1800 campaign in southwest Germany began on 1 May 1800, at the village of Büsingen, east of Schaffhausen (Switzerland); there a small force of 6,000 men under command of General of Brigade François Goullus defeated 4,000 men, three battalions of the 7th Infantry Regiment ''Schröder'', commanded by Lieutenant Field Marshal Karl Eugen, Prince von Lothringen-Lambesc. Following this clash, the impenetrable Württemberg fortress, Hohentwiel, capitulated to the French, in what the Duke of Württemberg considered a scandalous lack of military courage.

After these encounters, the French army moved toward Stockach, less than northwest of Hohentwiel, where they engaged the Austrian force, under Kray, in the battles of Battle of Stockach (1800), Engen and Stockach and Battle of Messkirch, Messkirch against the troops of the French Army of the Rhine (France), Army of the Rhine, under Jean Victor Moreau. Ebert"General der Kavallerie Graf von Klenau"

Stockach, at the western tip of

Lake Constance

Lake Constance (german: Bodensee, ) refers to three Body of water, bodies of water on the Rhine at the northern foot of the Alps: Upper Lake Constance (''Obersee''), Lower Lake Constance (''Untersee''), and a connecting stretch of the Rhine, ca ...

, covered east-west and north-south crossroads; it and near-by Engen, only west, had been the site of a French loss 14 months earlier. In 1800, a different general, Moreau, brought 84,000 troops against Kray's 72,000 men; this concentration of French force pushed the Austrian army eastward. Two days later, at Messkirch northeast of Stockach, Moreau brought 52,000 men, including Claude Lecourbe's and Dominique Vandamme's divisions, which had experienced the disappointing French loss in 1799, and Étienne Marie Antoine Champion de Nansouty's experienced cavalry against Kray's force of 48,000. Although the French lost more men, once again they drove the Austrians from the field.

Despite the Imperial losses at these battles, Klenau's solid field leadership led to his promotion to lieutenant general, lieutenant field marshal. That year he also married the widowed Maria Josephina Somsich de Sard, daughter of Tallian de Viseck. They had one daughter, Maria, born at the end of the year. From 1801 to 1805, during which Austria remained aloof from the ongoing friction between Britain and Napoleon's France, Klenau commanded a division in Prague, and was named as Colonel and Inhaber of the 5th Dragoon Regiment.

Napoleonic Wars

Background

In a series of conflicts from 1803 to 1815, known as the Napoleonic Wars, the alliances of the powers of Europe formed five coalitions against the First French Empire of Napoleon. Like the wars sparked by the French Revolution of 1789, these wars revolutionized the construction, organization, and training of European armies and led to an unprecedented militarization, mainly due to Levée en masse, mass conscription. French power rose quickly, conquering most of Europe, but collapsed rapidly after France's disastrous French invasion of Russia, invasion of Russia in 1812. Napoleon's empire ultimately suffered complete military defeat in the 1813–1814 campaigns, resulting in the Bourbon Restoration in France, restoration of the Bourbon monarchy in France. Although Napoleon made a spectacular return in 1815, known as the Hundred Days, his defeat at the Battle of Waterloo, the pursuit of his army and himself, his abdication, and his banishment to the Island of Saint Helena, concluded the Napoleonic wars.War of the Third Coalition

In the War of the Third Coalition, 1803–1806, an alliance of Austria, Portugal, Russia, and others fought the First French Empire and its French client republic, client states. Although several naval battles determined control of the seas, the outcome of the war was determined on the continent, predominantly in two major land operations. In the Ulm Campaign, Ulm campaign, Klenau's force achieved the single Austrian victory prior to the surrender of the Austrian army in Swabia. In the second determining event, the decisive French victory at the Battle of Austerlitz over the combined Russian and Austrian force forced a final capitulation of the Austrian forces and took the Habsburgs out of the Coalition. This did not establish a lasting peace on the continent. Kingdom of Prussia, Prussian worries about growing French influence in Central Europe sparked the War of the Fourth Coalition in 1806, in which Austria did not participate.Danube campaign: Road to Ulm

Upon Austria's entrance into the war in summer 1805, Klenau joined the Habsburg army in southern Germany and became mired in a short campaign that exposed the worst of the Habsburg military organization. Archduke Charles was sick, and had retired to recuperate. Archduke Ferdinand Karl Joseph of Austria-Este, Archduke Ferdinand, the brother-in-law of the Emperor Francis, was theoretically in command, but Ferdinand was a poor choice of replacement, having neither experience, maturity, nor aptitude. Although Ferdinand retained nominal command, decisions were placed in the hands of Karl Mack von Leiberich, Karl Mack, who was timid, indecisive, and ill-suited for such an important assignment. Furthermore, Mack had been wounded earlier in the campaign, and was unable to take full charge of the army. Consequently, command further devolved to Lieutenant Field Marshal Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwarzenberg, an able military officer, but as yet inexperienced in the command of such a large army. The campaign began in October, with several clashes in

The campaign began in October, with several clashes in Swabia

Swabia ; german: Schwaben , colloquially ''Schwabenland'' or ''Ländle''; archaic English also Suabia or Svebia is a cultural, historic and linguistic region in southwestern Germany.

The name is ultimately derived from the medieval Duchy of ...

. At the Battle of Wertingen, first, near the Bavarian town of Wertingen, northwest of Augsburg

Augsburg (; bar , Augschburg , links=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swabian_German , label=Swabian German, , ) is a city in Swabia, Bavaria, Germany, around west of Bavarian capital Munich. It is a university town and regional seat of the ' ...

, on 8 October, Joachim Murat, Murat's Cavalry Corps and grenadiers of Jean Lannes, Lannes' V Corps surprised an Austrian force half their size. The Austrians had assembled in line, and the cavalry and grenadiers cut them down before the Austrians could form their Infantry square, defensive squares. Nearly 3,000 were captured. A day later, at Günzburg immediately south of the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

, the French again met an Austrian force; General Mack could not decide on a plan, and the French 59th Regiment of the Line stormed a bridge over the Danube, and, in a humiliating episode, chased two large Austrian columns toward Ulm. In this action, the French secured an important bridgehead on the Danube River.

With the string of French victories, Lieutenant Field Marshal Klenau provided the only ray of hope in a campaign fraught with losses. At Ulm-Jungingen, Klenau had arranged his 25,000 infantry and cavalry in a prime defensive position and, on 11 October, an over-confident General of Division Pierre Dupont de l'Étang, Dupon de l'Étang attacked Klenau's force with fewer than 8,000 men. The French lost 1,500 dead and wounded, 900 captured, 11 guns and 18 ammunition wagons captured, but possibly of greater significance, the French Imperial Eagle, Imperial Eagles and Colours, standards and guidons, guidons of the 15th and 17th Dragoons were taken by the Austrians.

Despite Klenau's success at the Battle of Haslach-Jungingen, the Austrians could not sustain their positions around him, and the entire line retreated toward Ulm. Napoleon's lightning campaign exposed the Austrian weaknesses, particularly of indecisive command structure and poor supply apparatus. The Austrians were low on ammunition and outgunned. The components of the army, division by division, were being separated from one another. Morale sank, "sapped by Mack's chaotic orders and their [the troops] growing lack of confidence in their nominal commander," Ferdinand. Following the Austrian capitulation at Memmingen, south of Ulm, the French achieved a morale boost over the Austrians at the Battle of Elchingen, outside of Biberach an der Riss, Biberach, on 14 October. Here, northeast of Ulm, and slightly north of the Danube, Ney's VI Corps (20,000 men) captured half of the Austrian Reserve Artillery park at Thalfingen. In a further blow, Field Marshal Johann Sigismund Riesch, Riesch was unable to destroy the Danube bridges, which Ney secured for the French. Ney received the victory title, Duke of Elchingen.

At this point, the entire Austrian force, including Klenau's column, withdrew into Battle of Ulm, Ulm and its environs and Napoleon himself arrived to take command of the II, V, VI Corps, Ney's Cavalry and the Imperial Guard, numbering close to 80,000 men. Archduke Ferdinand and a dozen cavalry squadrons broke out through the French army and escaped into Bohemia. Again, as he had been at Mantua, Klenau was caught in a siege from which there was no escape, and again, he helped to negotiate the terms, when, on 21 October, Karl Mack surrendered the encircled army of 20,000 infantry and 3,273 cavalry. Klenau and the other officers were released on the condition that they not serve against France until exchanged, an agreement to which they held.

Action on the Danube by Vienna

The Austrians abstained from the fighting in 1806–1808, and engaged in a military reorganization, directed by Archduke Charles. When they were ready to join the fight against France, in the spring and summer of 1809, it was a remodeled Austrian army that took the field. Despite their internal military reorganization, however, in the War of the Fifth Coalition, the army retained much of its cumbersome command structure, which complicated the issuance of orders and the timely distribution of troops. When the Austrian army took the field in 1809, it battled for the "survival of the [Habsburg] dynasty," as Archduke Charles, the army's supreme commander, described the situation to his brother John. On the Danubian plains north of Vienna, the summer battles of Battle of Aspern-Essling, Aspern-Essling andWagram

Deutsch-Wagram (literally "German Wagram", ), often shortened to Wagram, is a village in the Gänserndorf District, in the state of Lower Austria, Austria. It is in the Marchfeld Basin, close to the Vienna city limits, about 15 km (9 mi) northeas ...

shaped the outcome of the 1809 campaign. Klenau's forces played a critical role at both. At Aspern-Essling, Napoleon's army was decisively defeated for the first time in northern Europe, demonstrating that the master of Europe could himself be mastered. After their defeat at Wagram, the Austrians withdrew into Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The me ...

, leaving the French in control of that part of the Danube valley; Wagram was the largest European land-battle to date, engaging 262 battalions and 202 squadrons—153,000 men—for France and her allies, and 160 battalions and 150 squadrons—135,000 men—on the Austrian side.

For Klenau, the campaign started badly at the Battle of Eckmühl (sometimes called Eggmühl), in southeastern Germany on 22 April 1809. Klenau commanded the Advance Guard, which included the 2nd ''Archduke Charles'' Legion, the Merveldt ''Uhlanen'' and a cavalry battery. Archduke Charles misread Napoleon's intentions and lost the advantage in the battle. Klenau's division suffered heavily and the ''Archduke Charles'' Legion was nearly wiped out in a charge by Louis Friant's cavalry. Rosenberg's division on Klenau's flank was also badly mauled and suffered heavy casualties: 534 killed, 637 wounded, 865 missing, and 773 captured.

The disaster at Eckmühl was followed by another at Battle of Regensburg, Regensburg (also called the Battle of Ratisbon) on 23 April, where Klenau, at the head of six squadrons of Merveldt's Uhlanen (lancers), was crushed and scattered by Étienne Marie Antoine Champion de Nansouty's heavy cavalry. Klenau and Major General Peter Vécsey stormed back at Nansouty's force with the ''Klenau'' chevauxlegers. Although their onslaught threw back the leading French squadrons, the French heavy cavalry returned, joined by Hussars and ''Chasseurs''. In the mêlee, it was difficult to distinguish French from Austrian, but eventually the French horse overwhelmed the Austrian flank and pushed them to the gates of Regensburg.

Aspern and Essling

By May 1809, the Austrians were pushed to within visual distance of Vienna, and in a critical engagement on the banks of the Danube river, the French and their allies grappled for control of the Morava (river), Marchfeld plain with the Austrians. The French held Lobau island, a vital river crossing, and the Austrians held the heights further to the east. Between them lay several villages, two of which were central in the engagement and gave the battle its name: They lay so close to Vienna that the battle could be seen and heard from the city ramparts and Aspern and Essling (also spelled in German as Eßling) are today part of the Donaustadt, a district of Austrian capital. At the Battle of Aspern-Essling, Klenau commanded a free-standing force of close to 6,000, including a battalion of the 1st ''Jäger'', three battalions of the 3rd Infantry Regiment ''Archduke Charles'', eight squadrons each of the ''Stipcisc'' Hussars and ''Schwarzenburg'' Uhlans, and a horse artillery battery of 64 guns. Typical confusion in the Austrian command structure meant he received his orders late, and Klenau's delay in deployment meant that his men approached the French III Corps at Essling in daylight and in close order; a two-gun French battery on the plain beyond the Essling, "mowed furrows" of enfilade fire in the Austrian ranks. Despite the withering fire, Klenau's force reached Essling's edge, where his men set up 64 artillery pieces and bombarded the French for nearly an hour. Taking the village by storm, Austrian cavalry poured into the village from the north, and the French were pushed out in a methodical advance. Klenau's batteries were able to fire on the French-held bridges south of the village, over which the French had to retreat. In bitter house-to-house fighting, the Austrians entered the village. Combat at the granary was especially brutal, as Hungarian grenadiers battled unsuccessfully to dislodge the French from their positions in the second and third floors. The battle resumed at dawn of 22 April. Masséna cleared Aspern of Austrians, but while he did so, Rosenberg's force stormedJean Lannes

Jean Lannes, 1st Duke of Montebello, Prince of Siewierz (10 April 1769 – 31 May 1809), was a French military commander and a Marshal of the Empire who served during both the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. He was one of Napoleon's ...

' position at Essling. Lannes, reinforced by Louis Vincent Le Blond de Saint-Hilaire, Vincent Saint-Hilaire's division, subsequently drove Rosenberg out of Essling. At Aspern, Masséna was driven out by Hiller and Bellegarde's counter-attacks.Gilles Boué. ''The Battle of Essling: Napoleon's first defeat?'' Alan McKay, Translator. Elkar, Spain: Histoire & Collections, 2008. . pp. 35–38.

Meanwhile, Napoleon had launched an attack on the main army at the Austrian center. Klenau's force stood on the immediate right flank of the center, opposite the attacking force of Lannes. The French cavalry, in reserve, prepared to move at either flank, or to the center, depending on where the Austrian line broke first. The French nearly broke through at the center but, at the last minute, Charles arrived with his last reserve, leading his soldiers with a color in his hand. Lannes was checked, and the impetus of the attack died out all along the line. In the final hours of the battle, Lannes himself was cut down by a cannonball from Klenau's artillery. Aspern was lost to the French. The Danube bridges upon which the French relied had been cut again by heavy barges, which the Austrians had released on the river. When he lost his route across the river, Napoleon at once suspended the attack. For his leadership at Essling, Klenau received the Commander's Cross of the Military Order of Maria Theresa.

Both sides lost close to 28,000 men, to wounds and death. For Napoleon, whose force was smaller, the losses were more costly. For Charles, the victory, which occurred within visual range of the Vienna ramparts, won him support from the hawks, or the pro-war party, in the Hofburg Imperial Palace, Hofburg. The Austrian victory at Aspern-Essling proved that Napoleon could be beaten. His force had been divided (Davout's corps had never made it over the Danube), and Napoleon had underestimated the Austrian strength of force and, more importantly, the tenacity the Austrians showed in situations like that of Essling, when Klenau marched his force across open country under enemy fire. After Aspern-Essling, Napoleon revised his opinion of the Austrian soldier.