Jim Thorpe on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

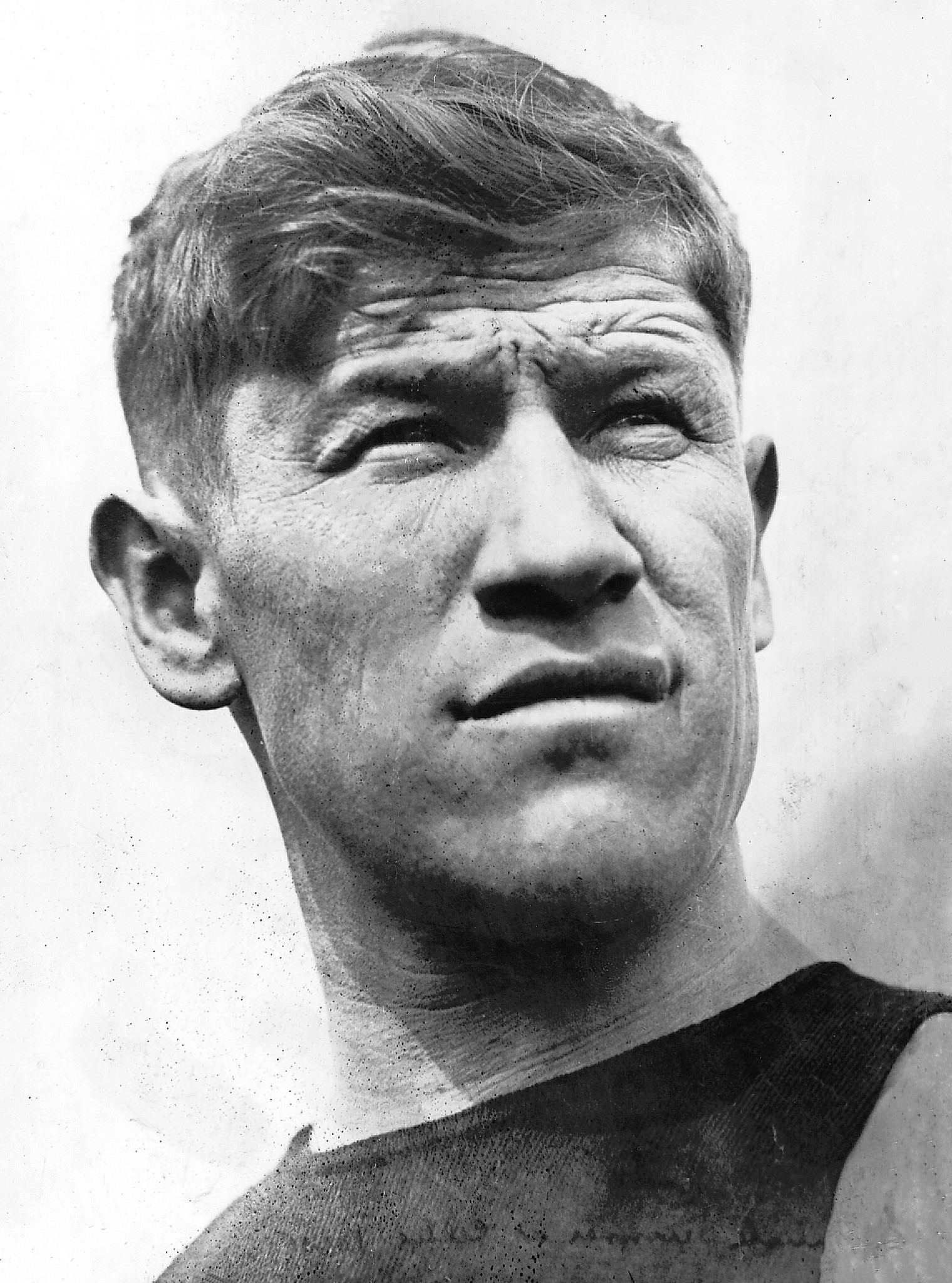

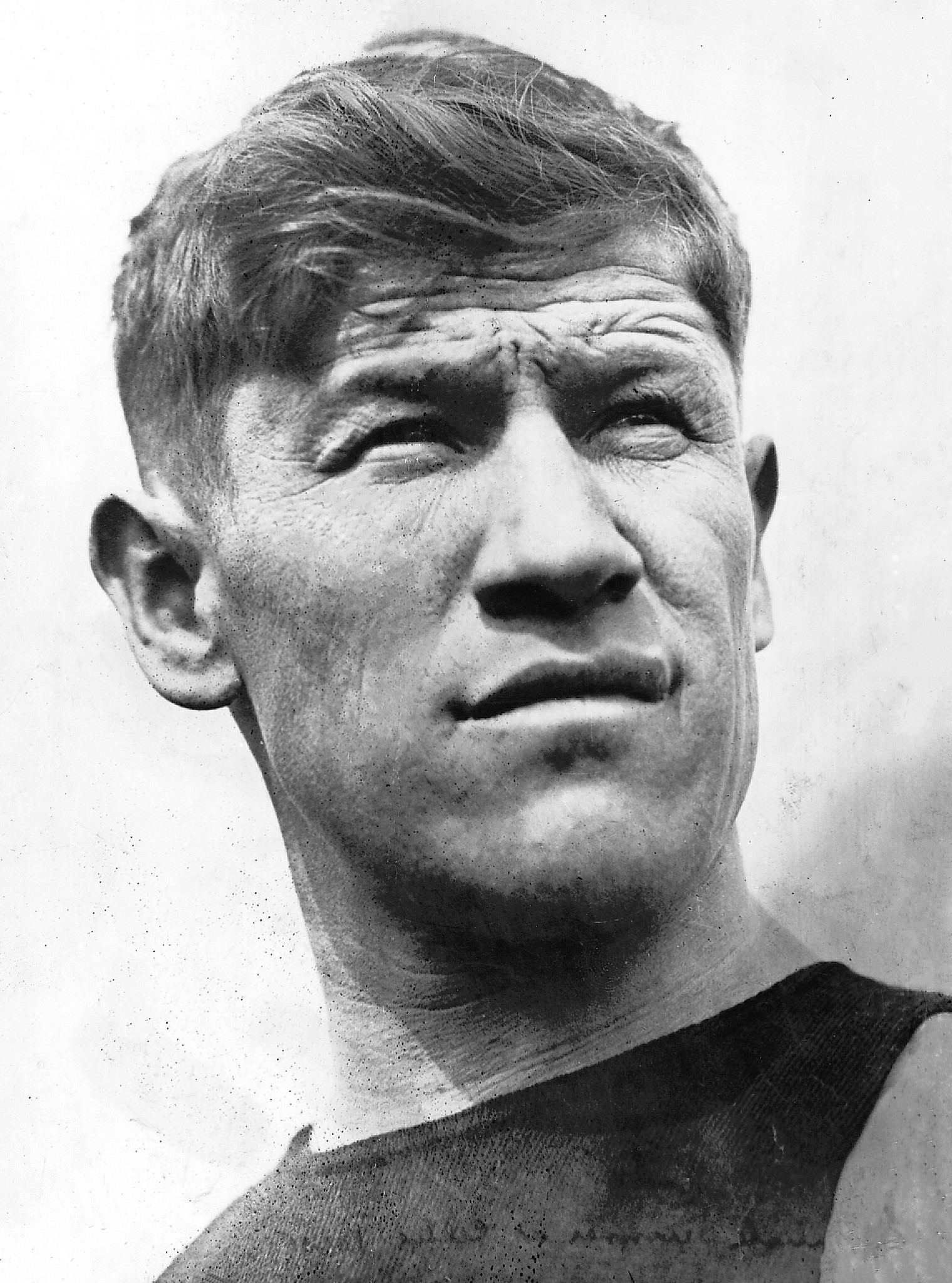

James Francis Thorpe ( Sac and Fox (Sauk): ''Wa-Tho-Huk'', translated as "Bright Path"; May 22 or 28, 1887March 28, 1953) was an American athlete and Olympic gold medalist. A member of the Sac and Fox Nation, Thorpe was the first Native American to win a gold medal for the United States in the Olympics. Considered one of the most versatile athletes of modern sports, he won two Olympic gold medals in the

cgmworldwide.com. Retrieved May 20, 2018. Thorpe ran away from school several times. His father sent him to the Haskell Institute, an

olympics30.com. Retrieved July 30, 2018. In 1904 the sixteen-year-old Thorpe returned to his father and decided to attend

Thorpe began his athletic career at Carlisle in 1907 when he walked past the track and, still in street clothes, beat all the school's

Thorpe began his athletic career at Carlisle in 1907 when he walked past the track and, still in street clothes, beat all the school's

Jim Thorpe

Thomson-Gale, ''Bookrags'', June 2006. Retrieved April 23, 2007. His earliest recorded track and field results come from 1907. He also competed in football, baseball,

usoc.org, Retrieved April 26, 2007. Future President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who played against him in that game, recalled of Thorpe in a 1961 speech:

"Thorpe preceded Deion, Bo"

File:Photograph of Jim Thorpe with Admirers - NARA - 595392.tif, Thorpe shaking hands with Moses Friedman while Glenn "Pop" Warner (left),

"The Inside Story of Baseball's Grand World Tour of 1914"

''Smithsonian'', March 21, 2014. Retrieved May 18, 2017. He met with

Thorpe signed with the

Thorpe signed with the

After his athletic career, Thorpe struggled to provide for his family. He found it difficult to work a non-sports-related job and never held a job for an extended period of time. During the

After his athletic career, Thorpe struggled to provide for his family. He found it difficult to work a non-sports-related job and never held a job for an extended period of time. During the

''Time'', February 22, 1943, available online via time.com. Retrieved May 21, 2007. Thorpe was a chronic alcoholic during his later life. He ran out of money sometime in the early 1950s. When hospitalized for lip cancer in 1950, Thorpe was admitted as a charity case. At a press conference announcing the procedure, his wife, Patricia, wept and pleaded for help, saying, "We're broke ... Jim has nothing but his name and his memories. He has spent money on his own people and has given it away. He has often been exploited." In early 1953, Thorpe went into

Over the years, supporters of Thorpe attempted to have his Olympic titles reinstated. US Olympic officials, including former teammate and later president of the IOC

Over the years, supporters of Thorpe attempted to have his Olympic titles reinstated. US Olympic officials, including former teammate and later president of the IOC

Thorpe's monument, featuring the quote from Gustav V ("You, sir, are the greatest athlete in the world."), still stands near the town named for him,

Thorpe's monument, featuring the quote from Gustav V ("You, sir, are the greatest athlete in the world."), still stands near the town named for him,

"Baseball in the Olympics"

. ''Citius, Altius, Fortius''. 1 (1): 7–15. Retrieved May 4, 2017. * Cook, William A. ''Jim Thorpe: A Biography''. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 2011. . * Dodge, Robert. ''Which Chosen People? Manifest Destiny Meets the Sioux: As Seen by Frank Fiske, Frontier Photographer''. New York: Algora Publishing, 2013. . * Dyreson, Mark. ''Making the American Team: Sport, Culture, and the Olympic Experience''. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998. . * Elfers, James E. ''The Tour to End All Tours''. Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2003. . * Findling, John E. and Pelle, Kimberly D., eds. ''Encyclopedia of the Modern Olympic Movement''. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2004. . * Gerasimo, Luisa and Whiteley, Sandra. ''The Teacher's Calendar of Famous Birthdays''.

1912 Summer Olympics

The 1912 Summer Olympics ( sv, Olympiska sommarspelen 1912), officially known as the Games of the V Olympiad ( sv, Den V olympiadens spel) and commonly known as Stockholm 1912, were an international multi-sport event held in Stockholm, Sweden, b ...

(one in classic pentathlon and the other in decathlon

The decathlon is a combined event in athletics consisting of ten track and field events. The word "decathlon" was formed, in analogy to the word "pentathlon", from Greek δέκα (''déka'', meaning "ten") and ἄθλος (''áthlos'', or ἄ ...

). He also played American football

American football (referred to simply as football in the United States and Canada), also known as gridiron, is a team sport played by two teams of eleven players on a rectangular field with goalposts at each end. The offense, the team wi ...

(collegiate and professional), professional baseball, and basketball.

He lost his Olympic titles after it was found he had been paid for playing two seasons of semi-professional baseball before competing in the Olympics, thus violating the contemporary amateurism

An amateur () is generally considered a person who pursues an avocation independent from their source of income. Amateurs and their pursuits are also described as popular, informal, self-taught, user-generated, DIY, and hobbyist.

History

...

rules. In 1983, 30 years after his death, the International Olympic Committee

The International Olympic Committee (IOC; french: link=no, Comité international olympique, ''CIO'') is a non-governmental sports organisation based in Lausanne, Switzerland. It is constituted in the form of an association under the Swis ...

(IOC) restored his Olympic medals with replicas, after ruling that the decision to strip him of his medals fell outside of the required 30 days. Official IOC records still listed Thorpe as co-champion in decathlon and pentathlon until 2022, when it was decided to restore him as the sole champion in both events.

Thorpe grew up in the Sac and Fox Nation in Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

(what is now the U.S. state of Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a state in the South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the north, Missouri on the northeast, Arkansas on the east, New ...

). As a youth, he attended Carlisle Indian Industrial School

The United States Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, generally known as Carlisle Indian Industrial School, was the flagship Indian boarding school in the United States from 1879 through 1918. It took over the historic Carlisle ...

in Carlisle, Pennsylvania

Carlisle is a borough in and the county seat of Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, United States. Carlisle is located within the Cumberland Valley, a highly productive agricultural region. As of the 2020 census, the borough population was 20,118; ...

, where he was a two-time All-America

The All-America designation is an annual honor bestowed upon an amateur sports person from the United States who is considered to be one of the best amateurs in their sport. Individuals receiving this distinction are typically added to an All-Am ...

n for the school's football team under coach Pop Warner

Glenn Scobey Warner (April 5, 1871 – September 7, 1954), most commonly known as Pop Warner, was an American college football coach at various institutions who is responsible for several key aspects of the modern game. Included among his inn ...

. After his Olympic success in 1912, which included a record score in the decathlon, he added a victory in the All-Around Championship of the Amateur Athletic Union

The Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) is an amateur sports organization based in the United States. A multi-sport organization, the AAU is dedicated exclusively to the promotion and development of amateur sports and physical fitness programs. It h ...

. In 1913, he played for the Pine Village Pros in Indiana. Later in 1913, Thorpe signed with the New York Giants

The New York Giants are a professional American football team based in the New York metropolitan area. The Giants compete in the National Football League (NFL) as a member club of the league's National Football Conference (NFC) East divisio ...

, and he played six seasons in Major League Baseball

Major League Baseball (MLB) is a professional baseball organization and the oldest major professional sports league in the world. MLB is composed of 30 total teams, divided equally between the National League (NL) and the American League (A ...

between 1913 and 1919. Thorpe joined the Canton Bulldogs

The Canton Bulldogs were a professional American football team, based in Canton, Ohio. They played in the Ohio League from 1903 to 1906 and 1911 to 1919, and the American Professional Football Association (later renamed the National Football Lea ...

American football team in 1915, helping them win three professional championships. He later played for six teams in the National Football League

The National Football League (NFL) is a professional American football league that consists of 32 teams, divided equally between the American Football Conference (AFC) and the National Football Conference (NFC). The NFL is one of the majo ...

(NFL). He played as part of several all-American Indian teams throughout his career, and barnstormed as a professional basketball player with a team composed entirely of American Indians.

From 1920 to 1921, Thorpe was nominally the first president of the American Professional Football Association

The National Football League (NFL) is a professional American football league that consists of 32 teams, divided equally between the American Football Conference (AFC) and the National Football Conference (NFC). The NFL is one of the majo ...

, which became the NFL in 1922. He played professional sports until age 41, the end of his sports career coinciding with the start of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

. He struggled to earn a living after that, working several odd jobs. He suffered from alcoholism

Alcoholism is, broadly, any drinking of alcohol that results in significant mental or physical health problems. Because there is disagreement on the definition of the word ''alcoholism'', it is not a recognized diagnostic entity. Predomi ...

, and lived his last years in failing health and poverty. He was married three times and had eight children, before suffering from heart failure and dying in 1953.

Thorpe has received numerous accolades for his athletic accomplishments. The Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. new ...

ranked him as the "greatest athlete" from the first 50 years of the 20th century, and the Pro Football Hall of Fame

The Pro Football Hall of Fame is the hall of fame for professional American football, located in Canton, Ohio. Opened on September 7, , the Hall of Fame enshrines exceptional figures in the sport of professional football, including players, coa ...

inducted him as part of its inaugural class in 1963. The town of Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania

Jim Thorpe is a borough and the county seat of Carbon County in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. It is part of Northeastern Pennsylvania. It is historically known as the burial site of Native American sports legend Jim Thorpe.

Jim Thorpe is l ...

was named in his honor. It has a monument site that contains his remains, which were the subject of legal action. Thorpe appeared in several films and was portrayed by Burt Lancaster

Burton Stephen Lancaster (November 2, 1913 – October 20, 1994) was an American actor and producer. Initially known for playing tough guys with a tender heart, he went on to achieve success with more complex and challenging roles over a 45-yea ...

in the 1951 film '' Jim Thorpe – All-American''.

Early life

Information about Thorpe's birth, name and ethnic background varies widely.O'Hanlon-Lincoln. p. 129. He was baptized "Jacobus Franciscus Thorpe" in theCatholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

. Thorpe was born in Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

of the United States (later Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a state in the South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the north, Missouri on the northeast, Arkansas on the east, New ...

), but no birth certificate

A birth certificate is a vital record that documents the birth of a person. The term "birth certificate" can refer to either the original document certifying the circumstances of the birth or to a certified copy of or representation of the ensui ...

has been found. He was generally considered to have been born on May 22, 1887, near the town of Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

. Thorpe said in a note to ''The Shawnee News-Star

''The Shawnee News-Star'' is an American daily newspaper published in Shawnee, Oklahoma. It is the newspaper of record for Pottawatomie, Lincoln and Seminole counties, in the Oklahoma City metropolitan area.

It took its current name in 1943 aft ...

'' in 1943 that he was born May 28, 1888, "near and south of Bellemont – Pottawatomie County – along the banks of the North Fork River ... hope this will clear up the inquiries as to my birthplace."Wheeler. p. 291. Most biographers believe that he was born on May 22, 1887, the date listed on his baptismal certificate. Thorpe referred to Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

as his birthplace in his 1943 note to the newspaper.

Thorpe's parents were both of mixed-race ancestry. His father, Hiram Thorpe, had an Irish father and a Sac and Fox Indian mother. His mother, Charlotte Vieux, had a French father and a Potawatomi

The Potawatomi , also spelled Pottawatomi and Pottawatomie (among many variations), are a Native American people of the western Great Lakes region, upper Mississippi River and Great Plains. They traditionally speak the Potawatomi language, a m ...

mother, a descendant of Chief Louis Vieux Louis may refer to:

* Louis (coin)

* Louis (given name), origin and several individuals with this name

* Louis (surname)

* Louis (singer), Serbian singer

* HMS ''Louis'', two ships of the Royal Navy

See also

Derived or associated terms

* Lewis ...

. Thorpe was raised as a Sac and Fox, and his native name, ''Wa-Tho-Huk'', is translated as "path lit by great flash of lightning" or, more simply, "Bright Path". As was the custom for Sac and Fox, he was named for something occurring around the time of his birth, in this case the light brightening the path to the cabin where he was born. Thorpe's parents were both Roman Catholic, a faith which Thorpe observed throughout his adult life.

Thorpe attended the Sac and Fox Indian Agency school in Stroud

Stroud is a market town and civil parish in Gloucestershire, England. It is the main town in Stroud District. The town's population was 13,500 in 2021.

Below the western escarpment of the Cotswold Hills, at the meeting point of the Five Va ...

, with his twin brother, Charlie. Charlie helped him through school until he died of pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severit ...

when they were nine years old.Jim Thorpe – Fast factscgmworldwide.com. Retrieved May 20, 2018. Thorpe ran away from school several times. His father sent him to the Haskell Institute, an

Indian boarding school

American Indian boarding schools, also known more recently as American Indian residential schools, were established in the United States from the mid 17th to the early 20th centuries with a primary objective of "civilizing" or assimilating Na ...

in Lawrence, Kansas

Lawrence is the county seat of Douglas County, Kansas, Douglas County, Kansas, United States, and the sixth-largest city in the state. It is in the northeastern sector of the state, astride Interstate 70, between the Kansas River, Kansas and Waka ...

, so that he would not run away again.

When Thorpe's mother died of childbirth complications two years later, the youth became depressed. After several arguments with his father, he left home to work on a horse ranch.Jim Thorpe – Olympic Hero and Native Americanolympics30.com. Retrieved July 30, 2018. In 1904 the sixteen-year-old Thorpe returned to his father and decided to attend

Carlisle Indian Industrial School

The United States Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, generally known as Carlisle Indian Industrial School, was the flagship Indian boarding school in the United States from 1879 through 1918. It took over the historic Carlisle ...

in Carlisle, Pennsylvania

Carlisle is a borough in and the county seat of Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, United States. Carlisle is located within the Cumberland Valley, a highly productive agricultural region. As of the 2020 census, the borough population was 20,118; ...

. There his athletic ability was recognized and he was coached by Glenn Scobey "Pop" Warner, one of the most influential coaches of early American football history. Later that year the youth was orphaned after his father Hiram Thorpe died from gangrene

Gangrene is a type of tissue death caused by a lack of blood supply. Symptoms may include a change in skin color to red or black, numbness, swelling, pain, skin breakdown, and coolness. The feet and hands are most commonly affected. If the gan ...

poisoning, after being wounded in a hunting accident.Hoxie. p. 628. The young Thorpe again dropped out of school. He resumed farm work for a few years before returning to Carlisle School.

Amateur career

College career

Thorpe began his athletic career at Carlisle in 1907 when he walked past the track and, still in street clothes, beat all the school's

Thorpe began his athletic career at Carlisle in 1907 when he walked past the track and, still in street clothes, beat all the school's high jump

The high jump is a track and field event in which competitors must jump unaided over a horizontal bar placed at measured heights without dislodging it. In its modern, most-practiced format, a bar is placed between two standards with a crash mat f ...

ers with an impromptu 5-ft 9-in jump.''Encyclopedia of World Biography''Jim Thorpe

Thomson-Gale, ''Bookrags'', June 2006. Retrieved April 23, 2007. His earliest recorded track and field results come from 1907. He also competed in football, baseball,

lacrosse

Lacrosse is a team sport played with a lacrosse stick and a lacrosse ball. It is the oldest organized sport in North America, with its origins with the indigenous people of North America as early as the 12th century. The game was extensiv ...

, and ballroom dancing

Ballroom dance is a set of partner dances, which are enjoyed both socially and competitively around the world, mostly because of its performance and entertainment aspects. Ballroom dancing is also widely enjoyed on stage, film, and television. ...

, winning the 1912 intercollegiate ballroom dancing championship.

Pop Warner

Glenn Scobey Warner (April 5, 1871 – September 7, 1954), most commonly known as Pop Warner, was an American college football coach at various institutions who is responsible for several key aspects of the modern game. Included among his inn ...

was hesitant to allow Thorpe, his best track and field athlete, to compete in such a physical game as football.Jeansonne. p. 60. Thorpe, however, convinced Warner to let him try some rushing plays in practice against the school team's defense; Warner assumed he would be tackled easily and give up the idea. Thorpe "ran around past and through them not once, but twice". He walked over to Warner and said, "Nobody is going to tackle Jim", while flipping him the ball.

Thorpe first gained nationwide notice in 1911 for his athletic ability. As a running back

A running back (RB) is a member of the offensive backfield in gridiron football. The primary roles of a running back are to receive handoffs from the quarterback to rush the ball, to line up as a receiver to catch the ball,

and block. Th ...

, defensive back

In gridiron football, defensive backs (DBs), also called the secondary, are the players on the defensive side of the ball who play farthest back from the line of scrimmage. They are distinguished from the other two sets of defensive players, the ...

, placekicker

Placekicker, or simply kicker (PK or K), is the player in gridiron football who is responsible for the kicking duties of field goals and extra points. In many cases, the placekicker also serves as the team's kickoff specialist or punter.

S ...

and punter, Thorpe scored all of his team's four field goals in an 18–15 upset of Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

, a top-ranked team in the early days of the National Collegiate Athletic Association

The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) is a nonprofit organization that regulates student athletics among about 1,100 schools in the United States, Canada, and Puerto Rico. It also organizes the athletic programs of colleges ...

(NCAA). His team finished the season 11–1. In 1912 Carlisle won the national collegiate championship largely as a result of Thorpe's efforts: he scored 25 touchdown

A touchdown (abbreviated as TD) is a scoring play in gridiron football. Whether running, passing, returning a kickoff or punt, or recovering a turnover, a team scores a touchdown by advancing the ball into the opponent's end zone. In Amer ...

s and 198 points during the season, according to CNN's Greg Botelho. Steve Boda, a researcher for the NCAA, credits Thorpe with 27 touchdowns and 224 points. Thorpe rushed 191 times for 1,869 yards, according to Boda; the figures do not include statistics from two of Carlisle's 14 games in 1912 because full records are not available.

Carlisle's 1912 record included a 27–6 victory over the West Point Army team. In that game, Thorpe's 92-yard touchdown was nullified by a teammate's penalty, but on the next play Thorpe rushed for a 97-yard touchdown.Jim Thorpeusoc.org, Retrieved April 26, 2007. Future President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who played against him in that game, recalled of Thorpe in a 1961 speech:

Here and there, there are some people who are supremely endowed. My memory goes back to Jim Thorpe. He never practiced in his life, and he could do anything better than any other football player I ever saw.Botelho, GregThorpe was awarded third-team All-American honors in 1908, and named a first-team All-American in 1911 and 1912. Football was – and remained – Thorpe's favorite sport. He did not compete in track and field in 1910 or 1911, although this turned out to be the sport in which he gained his greatest fame.

"Roller-coaster life of Indian icon, sports' first star"

CNN.com, July 14, 2004. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

In the spring of 1912, he started training for the Olympics. He had confined his efforts to jumps, hurdles and shot-puts, but now added pole vaulting, javelin, discus, hammer and 56 lb weight. In the Olympic trials held at Celtic Park in New York, his all-round ability stood out in all these events and so he earned a place on the team that went to Sweden.

Olympic career

For the1912 Summer Olympics

The 1912 Summer Olympics ( sv, Olympiska sommarspelen 1912), officially known as the Games of the V Olympiad ( sv, Den V olympiadens spel) and commonly known as Stockholm 1912, were an international multi-sport event held in Stockholm, Sweden, b ...

in Stockholm, Sweden, two new multi-event disciplines were included, the pentathlon

A pentathlon is a contest featuring five events. The name is derived from Greek: combining the words ''pente'' (five) and -''athlon'' (competition) ( gr, πένταθλον). The first pentathlon was documented in Ancient Greece and was part of ...

and the decathlon

The decathlon is a combined event in athletics consisting of ten track and field events. The word "decathlon" was formed, in analogy to the word "pentathlon", from Greek δέκα (''déka'', meaning "ten") and ἄθλος (''áthlos'', or ἄ ...

.Buford. p. 112. A pentathlon, based on the ancient Greek event, had been introduced at the 1906 Intercalated Games

The 1906 Intercalated Games or 1906 Olympic Games was an international multi-sport event that was celebrated in Athens, Greece. They were at the time considered to be Olympic Games and were referred to as the "Second International Olympic Gam ...

. The 1912 version consisted of the long jump

The long jump is a track and field event in which athletes combine speed, strength and agility in an attempt to leap as far as possible from a takeoff point. Along with the triple jump, the two events that measure jumping for distance as a ...

, javelin throw, 200-meter dash, discus throw

The discus throw (), also known as disc throw, is a track and field event in which an athlete throws a heavy disc—called a discus—in an attempt to mark a farther distance than their competitors. It is an ancient sport, as demonstrated by th ...

, and 1500-meter run.

The decathlon was a relatively new event in modern athletics, although a similar competition known as the all-around championship had been part of American track meets since the 1880s. A men's version had been featured on the program of the 1904 St. Louis Olympics. The events of the new decathlon differed slightly from the American version.

Both events seemed appropriate for Thorpe, who was so versatile that he served as Carlisle's one-man team in several track meets. According to his obituary in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', he could run the 100-yard dash in 10 seconds flat; the 220 in 21.8 seconds; the 440 in 51.8 seconds; the 880 in 1:57, the mile in 4:35; the 120-yard high hurdles in 15 seconds; and the 220-yard low hurdles in 24 seconds. He could long jump 23 ft 6 in and high-jump 6 ft 5 in. He could pole vault

Pole vaulting, also known as pole jumping, is a track and field event in which an athlete uses a long and flexible pole, usually made from fiberglass or carbon fiber, as an aid to jump over a bar. Pole jumping competitions were known to the M ...

11 feet; put the shot

The shot put is a track and field event involving "putting" (throwing) a heavy spherical Ball (sports), ball—the ''shot''—as far as possible. The shot put competition for men has been a part of the Olympic Games, modern Olympics since their r ...

47 ft 9 in; throw the javelin 163 feet; and throw the discus 136 feet.

Thorpe entered the U.S. Olympic trials for both the pentathlon and the decathlon. He easily earned a place on the pentathlon team, winning three events. The decathlon trial was subsequently cancelled, and Thorpe was chosen to represent the U.S. in the event. The pentathlon and decathlon teams also included Avery Brundage

Avery Brundage (; September 28, 1887 – May 8, 1975) was an American sports administrator who served as the fifth president of the International Olympic Committee from 1952 to 1972. The only American and only non-European to attain that p ...

, a future International Olympic Committee

The International Olympic Committee (IOC; french: link=no, Comité international olympique, ''CIO'') is a non-governmental sports organisation based in Lausanne, Switzerland. It is constituted in the form of an association under the Swis ...

president.

Thorpe was extremely busy in the Olympics. Along with the decathlon and pentathlon, he competed in the long jump and high jump. The first competition was the pentathlon on July 7. He won four of the five events and placed third in the javelin, an event he had not competed in before 1912. Although the pentathlon was primarily decided on place points, points were also earned for the marks achieved in the individual events. Thorpe won the gold medal. That same day, he qualified for the high jump final, in which he finished in a tie for fourth. On July 12, Thorpe placed seventh in the long jump.

Thorpe's final event was the decathlon, his first (and as it turned out, his only) decathlon. Strong competition from local favorite Hugo Wieslander was expected. Thorpe, however, defeated Wieslander by 688 points. He placed in the top four in all ten events, and his Olympic record of 8,413 points stood for nearly two decades. Even more remarkably, because someone had stolen his shoes just before he was due to compete, he found a mismatched pair of replacements, including one from a trash can, and won the gold medal wearing them. Overall, Thorpe won eight of the 15 individual events comprising the pentathlon and decathlon.

As was the custom of the day, the medals were presented to the athletes during the closing ceremonies of the games. Along with the two gold medals, Thorpe also received two challenge prizes, which were donated by King Gustav V of Sweden for the decathlon and Czar Nicholas II of Russia for the pentathlon. Several sources recount that, when awarding Thorpe his prize, King Gustav said, "You, sir, are the greatest athlete in the world", to which Thorpe replied, "Thanks, King".Flatter, Ron"Thorpe preceded Deion, Bo"

ESPN.com

ESPN.com is the official website of ESPN. It is owned by ESPN Internet Ventures, a division of ESPN Inc.

History

Since launching in April 1995 as ESPNET.SportsZone.com (ESPNET SportsZone), the website has developed numerous sections including: ...

. Retrieved April 23, 2007. Thorpe biographer Kate Buford suggests that the story is apocryphal

Apocrypha are works, usually written, of unknown authorship or of doubtful origin. The word ''apocryphal'' (ἀπόκρυφος) was first applied to writings which were kept secret because they were the vehicles of esoteric knowledge considered ...

, as she believes that such a comment "would have been out of character for a man who was highly uncomfortable in public ceremonies and hated to stand out." The anecdote appeared in newspapers by 1948, 36 years after his appearance in the Olympics and time for myth making, and in books as early as 1952.

Thorpe's successes were followed in the United States. On the Olympic team's return, Thorpe was the star attraction in a ticker-tape parade

A ticker-tape parade is a parade event held in an urban setting, characterized by large amounts of shredded paper thrown onto the parade route from the surrounding buildings, creating a celebratory flurry of paper. Originally, actual ticker tap ...

on Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

**Broadway Theatre (53rd Stree ...

. He remembered later, "I heard people yelling my name, and I couldn't realize how one fellow could have so many friends."

Apart from his track and field appearances, Thorpe also played in one of two exhibition baseball games at the 1912 Olympics, which featured two teams composed mostly of U.S. track and field athletes. Thorpe had previous experience in the sport, as the public soon learned.

Lewis Tewanima

Louis Tewanima (1888 – January 18, 1969), also known as Tsökahovi Tewanima and Lewis Tewanima, was an American two-time Olympic distance runner and silver medalist in the 10,000 meter run in 1912. He was a Hopi Indian and ran for the Carlis ...

(center), and a crowd look on

File:Jim Thorpe.jpg, upThorpe in Carlisle Indian Industrial School

The United States Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, generally known as Carlisle Indian Industrial School, was the flagship Indian boarding school in the United States from 1879 through 1918. It took over the historic Carlisle ...

uniform, c. 1909

File:Photograph of Jim Thorpe - NARA - 595347.jpg, Thorpe, c. 1910

File:Jim Thorpe, 1912 Summer Olympics.jpg, Thorpe at the 1912 Summer Olympics

All-Around champion

After his victories at the Olympic Games in Sweden, on September 2, 1912, Thorpe returned to Celtic Park, the home of the Irish American Athletic Club, inQueens

Queens is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Queens County, in the U.S. state of New York. Located on Long Island, it is the largest New York City borough by area. It is bordered by the borough of Brooklyn at the western tip of Long ...

, New York (where he had qualified four months earlier for the Olympic Games), to compete in the Amateur Athletic Union

The Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) is an amateur sports organization based in the United States. A multi-sport organization, the AAU is dedicated exclusively to the promotion and development of amateur sports and physical fitness programs. It h ...

's All-Around Championship. Competing against Bruno Brodd Bruno Brodd (July 2, 1886 – April 24, 1956) was an American track and field athlete, born in Finland, who specialized in the javelin throw. He competed for the Irish American Athletic Club and the Kaleva Athletic Club.

1910 American javelin cham ...

of the Irish American Athletic Club and John L. Bredemus of Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

, he won seven of the ten events contested and came in second in the remaining three. With a total point score of 7,476 points, Thorpe broke the previous record of 7,385 points set in 1909 (also at Celtic Park), by Martin Sheridan, the champion athlete of the Irish American Athletic Club. Sheridan, a five-time Olympic gold medalist, was present to watch his record broken. He approached Thorpe after the event and shook his hand saying, "Jim, my boy, you're a great man. I never expect to look upon a finer athlete." He told a reporter from ''New York World

The ''New York World'' was a newspaper published in New York City from 1860 until 1931. The paper played a major role in the history of American newspapers. It was a leading national voice of the Democratic Party. From 1883 to 1911 under pub ...

'', "Thorpe is the greatest athlete that ever lived. He has me beaten fifty ways. Even when I was in my prime, I could not do what he did today."

Controversy

In 1912, strict rules regardingamateurism

An amateur () is generally considered a person who pursues an avocation independent from their source of income. Amateurs and their pursuits are also described as popular, informal, self-taught, user-generated, DIY, and hobbyist.

History

...

were in effect for athletes participating in the Olympics. Athletes who received money prizes for competitions, were sports teachers, or had competed previously against professionals were not considered amateurs. They were barred from competition.

In late January 1913, the ''Worcester Telegram

The ''Telegram & Gazette'' (and ''Sunday Telegram'') is the only daily newspaper of Worcester, Massachusetts

Worcester ( , ) is a city and county seat of Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. Named after Worcester, England, the c ...

'' reported that Thorpe had played professional baseball before the Olympics, and other U.S. newspapers followed up the story. Thorpe had played professional baseball in the Eastern Carolina League for Rocky Mount, North Carolina

Rocky Mount is a city in Edgecombe and Nash counties in the U.S. state of North Carolina. The city's population was 54,341 as of the 2020 census, making it the 20th-most populous city in North Carolina at the time. The city is 45 mi (7 ...

, in 1909 and 1910, receiving meager pay; reportedly as little as US$2 ($ today) per game and as much as US$35 ($ today) per week. College players, in fact, regularly spent summers playing professionally in order to earn some money, but most used aliases, unlike Thorpe. Although the public did not seem to care much about Thorpe's past,Schaffer and Smith. p. 50. the Amateur Athletic Union

The Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) is an amateur sports organization based in the United States. A multi-sport organization, the AAU is dedicated exclusively to the promotion and development of amateur sports and physical fitness programs. It h ...

(AAU), and especially its secretary James Edward Sullivan

James Edward Sullivan (8 November 1862 – 16 September 1914) was an American sports official of Irish descent. He was one of the founders of the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) on Jan 21, 1888, serving as its secretary from 1889 until 1906 whe ...

, took the case very seriously.

Thorpe wrote a letter to Sullivan, in which he admitted playing professional baseball:

His letter did not help. The AAU decided to withdraw Thorpe's amateur status retroactively. Later that year, the International Olympic Committee

The International Olympic Committee (IOC; french: link=no, Comité international olympique, ''CIO'') is a non-governmental sports organisation based in Lausanne, Switzerland. It is constituted in the form of an association under the Swis ...

(IOC) unanimously decided to strip Thorpe of his Olympic titles, medals and awards, and declare him a professional.

Although Thorpe had played for money, the AAU and IOC did not follow their own rules for disqualification. The rulebook for the 1912 Olympics stated that protests had to be made "within 30 days from the closing ceremonies of the games." The first newspaper reports did not appear until January 1913, about six months after the Stockholm Games had concluded. There is also some evidence that Thorpe was known to have played professional baseball before the Olympics, but the AAU had ignored the issue until being confronted with it in 1913. The only positive aspect of this affair for Thorpe was that, as soon as the news was reported that he had been declared a professional, he received offers from professional sports clubs.

Professional career

Baseball free agent

Because the minor league team that last held Jim Thorpe's contract had disbanded in 1910, the athlete had the unusual status as a sought-afterfree agent

In professional sports, a free agent is a player who is eligible to sign with other clubs or franchises; i.e., not under contract to any specific team. The term is also used in reference to a player who is under contract at present but who i ...

at the major league level during the era of the reserve clause

The reserve clause, in North American professional sports, was part of a player contract which stated that the rights to players were retained by the team upon the contract's expiration. Players under these contracts were not free to enter into an ...

. He could choose the baseball team for which to play. In January 1913, he turned down a starting position with the St. Louis Browns, then at the bottom of the American League. He chose to join the 1912 National League champion New York Giants

The New York Giants are a professional American football team based in the New York metropolitan area. The Giants compete in the National Football League (NFL) as a member club of the league's National Football Conference (NFC) East divisio ...

. With Thorpe playing in 19 of their 151 games, they repeated as the 1913 National League champions. Immediately following the Giants' October loss in the 1913 World Series

The 1913 World Series was the championship series in Major League Baseball for the 1913 season. The tenth edition of the World Series, it matched the American League (AL) champion Philadelphia Athletics against the National League (NL) New York ...

, Thorpe and the Giants joined the Chicago White Sox

The Chicago White Sox are an American professional baseball team based in Chicago. The White Sox compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) Central division. The team is owned by Jerry Reinsdorf, and ...

for a world tour. Barnstorming across the United States and around the world, Thorpe was the celebrity of the tour. Thorpe's presence increased the publicity, attendance and gate receipts Gate receipts, or simply "gate", is the sum of money taken at a sporting venue for the sale of tickets.

Traditionally, gate receipts were largely or entirely taken in cash. Today, many sporting venues will operate a season ticket scheme, which will ...

for the tour.Clavin, Tom"The Inside Story of Baseball's Grand World Tour of 1914"

''Smithsonian'', March 21, 2014. Retrieved May 18, 2017. He met with

Pope Pius X

Pope Pius X ( it, Pio X; born Giuseppe Melchiorre Sarto; 2 June 1835 – 20 August 1914) was head of the Catholic Church from 4 August 1903 to his death in August 1914. Pius X is known for vigorously opposing modernist interpretations of ...

and Abbas II Hilmi Bey (the last Khedive

Khedive (, ota, خدیو, hıdiv; ar, خديوي, khudaywī) was an honorific title of Persian origin used for the sultans and grand viziers of the Ottoman Empire, but most famously for the viceroy of Egypt from 1805 to 1914.Adam Mestyan"K ...

of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

), and played before 20,000 people in London including King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

. Thorpe was the last man to compete in both the Olympics (in a non-baseball sport) and Major League Baseball

Major League Baseball (MLB) is a professional baseball organization and the oldest major professional sports league in the world. MLB is composed of 30 total teams, divided equally between the National League (NL) and the American League (A ...

before Eddy Alvarez

Eduardo Cortes Alvarez (born January 30, 1990) is an American professional baseball infielder in the Milwaukee Brewers organization. He has played in Major League Baseball (MLB) for the Miami Marlins and Los Angeles Dodgers. Prior to his ba ...

did the same in 2020.

Baseball, football, and other sports

Thorpe signed with the

Thorpe signed with the New York Giants

The New York Giants are a professional American football team based in the New York metropolitan area. The Giants compete in the National Football League (NFL) as a member club of the league's National Football Conference (NFC) East divisio ...

baseball club in 1913 and played sporadically with them as an outfielder for three seasons. After playing in the minor leagues with the Milwaukee Brewers

The Milwaukee Brewers are an American professional baseball team based in Milwaukee. They compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the National League (NL) National League Central, Central division. The Brewers are named for t ...

in 1916, he returned to the Giants in 1917. He was sold to the Cincinnati Reds

The Cincinnati Reds are an American professional baseball team based in Cincinnati. They compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the National League (NL) National League Central, Central division and were a charter member of ...

early in the season. In the "double no-hitter

In baseball, a no-hitter is a game in which a team was not able to record a hit. Major League Baseball (MLB) officially defines a no-hitter as a completed game in which a team that batted in at least nine innings recorded no hits. A pitcher wh ...

" between Fred Toney

Fred Toney (December 11, 1888 – March 11, 1953) was an American right-handed pitcher in Major League Baseball for the Chicago Cubs, Cincinnati Reds, New York Giants and St. Louis Cardinals from 1911 to 1923. His career record was 139 wins, 102 ...

of the Reds and Hippo Vaughn

James Leslie "Hippo" Vaughn (April 9, 1888 – May 29, 1966) was an American left-handed pitcher in Major League Baseball. In a career that spanned thirteen seasons, he played for the New York Highlanders (1908, 1910–1912), the Washington Senat ...

of the Chicago Cubs

The Chicago Cubs are an American professional baseball team based in Chicago. The Cubs compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as part of the National League (NL) Central division. The club plays its home games at Wrigley Field, which is locate ...

, Thorpe drove in the winning run in the 10th inning. Late in the season, he was sold back to the Giants. Again, he played sporadically for them in 1918 before being traded to the Boston Braves

The Atlanta Braves, a current Major League Baseball franchise, originated in Boston, Massachusetts. This article details the history of the Boston Braves, from 1871 to 1952, after which they moved to Milwaukee, and then to Atlanta.

During it ...

on May 21, 1919, for Pat Ragan. In his career, he amassed 91 runs scored

In baseball, a run is scored when a player advances around first, second and third base and returns safely to home plate, touching the bases in that order, before three outs are recorded and all obligations to reach base safely on batted bal ...

, 82 runs batted in

A run batted in (RBI; plural RBIs ) is a statistic in baseball and softball that credits a batter for making a play that allows a run to be scored (except in certain situations such as when an error is made on the play). For example, if the b ...

and a .252 batting average

Batting average is a statistic in cricket, baseball, and softball that measures the performance of batters. The development of the baseball statistic was influenced by the cricket statistic.

Cricket

In cricket, a player's batting average is ...

over 289 games. He continued to play minor league baseball until 1922, and once played for the minor league Toledo Mud Hens

The Toledo Mud Hens are a Minor League Baseball team of the International League and the Triple-A affiliate of the Detroit Tigers. They are located in Toledo, Ohio, and play their home games at Fifth Third Field. A Mud Hens team has played in ...

.

But Thorpe had not abandoned football either. He first played professional football in 1913 as a member of the Indiana-based Pine Village Pros, a team that had a several-season winning streak against local teams during the 1910s. He signed with the Canton Bulldogs

The Canton Bulldogs were a professional American football team, based in Canton, Ohio. They played in the Ohio League from 1903 to 1906 and 1911 to 1919, and the American Professional Football Association (later renamed the National Football Lea ...

in 1915. They paid him $250 ($ today) a game, a tremendous wage at the time.Neft, Cohen, and Korch. p. 18. Before signing him Canton was averaging 1,200 fans a game, but 8,000 showed up for Thorpe's debut against the Massillon Tigers

The Massillon Tigers were an early professional football team from Massillon, Ohio. Playing in the "Ohio League", the team was a rival to the pre-National Football League version of the Canton Bulldogs. The Tigers won Ohio League championships i ...

. The team won titles in 1916, 1917, and 1919. Thorpe reportedly ended the 1919 championship game by kicking a wind-assisted 95-yard punt from his team's own 5-yard line, effectively putting the game out of reach.

In 1920, the Bulldogs were one of 14 teams to form the American Professional Football Association

The National Football League (NFL) is a professional American football league that consists of 32 teams, divided equally between the American Football Conference (AFC) and the National Football Conference (NFC). The NFL is one of the majo ...

, which became the National Football League

The National Football League (NFL) is a professional American football league that consists of 32 teams, divided equally between the American Football Conference (AFC) and the National Football Conference (NFC). The NFL is one of the majo ...

(NFL) two years later. Thorpe was nominally their first president, but spent most of the year playing for Canton; a year later, he was replaced as president by Joseph Carr

Joseph Francis Carr (October 22, 1879 – May 20, 1939) was an American sports executive in American football, baseball, and basketball. He is best known as the president of the National Football League from 1921 until 1939. He was also one of ...

. He continued to play for Canton, coaching the team as well. Between 1921 and 1923, he helped organize and played for the Oorang Indians (LaRue, Ohio

LaRue is a village in Marion County, Ohio, United States. The population was 747 at the 2010 census. The village is served by Elgin Local School District. LaRue has a public library, a branch of Marion Public Library.

Geography

LaRue is located ...

), an all-Native American team. Although the team's record was 3–6 in 1922, and 1–10 in 1923, Thorpe played well and was selected for the ''Green Bay Press-Gazette

The ''Green Bay Press-Gazette'' is a newspaper whose primary coverage is of northeastern Wisconsin, including Green Bay. It was founded as the ''Green Bay Gazette'' in 1866 as a weekly paper, becoming a daily newspaper in 1871. The ''Green Ba ...

'' first All-NFL team in 1923. This was later formally recognized in 1931 by the NFL as the league's official All-NFL team).

Thorpe never played for an NFL championship team. He retired from professional football at age 41, having played 52 games for six teams from 1920 to 1928.

Most of Thorpe's biographers were unaware of his basketball career until a ticket that documented his time in professional basketball was discovered in an old book in 2005. By 1926, he was the main feature of the "World Famous Indians" of LaRue, a traveling basketball team. "Jim Thorpe's world famous Indians" barnstormed for at least two years (1927–28) in multiple states. Although stories about Thorpe's team were published in some local newspapers at the time, his basketball career is not well-documented. For a brief time in 1913, he was considering going into professional hockey

Hockey is a term used to denote a family of various types of both summer and winter team sports which originated on either an outdoor field, sheet of ice, or dry floor such as in a gymnasium. While these sports vary in specific rules, numbers o ...

for the Tecumseh Hockey Club in Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the anch ...

, Ontario, Canada.

Marriage and family

Thorpe married three times and had a total of eight children. In 1913, Thorpe married Iva M. Miller, whom he had met at Carlisle. In 1917, Iva and Thorpe bought a house now known as theJim Thorpe House

The Jim Thorpe House is a historic house in Yale, Oklahoma.

In 1917, Jim Thorpe bought a small home in Yale, Oklahoma and lived there until 1923 with his wife, Iva Miller, and children, one of whom, Jim Jr., died at the age of two. The house ...

in Yale, Oklahoma

Yale is a city in Payne County, Oklahoma, United States. The population was 1,059 at the 2020 census, a decline of 13.6 percent from the figure of 1,227 in 2010.

History

Yale's founding in 1895 is attributed to a local farmer, Sterling F. Under ...

, and lived there until 1923. They had four children: James F., Gale, Charlotte, and Frances Thorpe. Miller filed for divorce from Thorpe in 1925, claiming desertion.

In 1926, Thorpe married Freeda Verona Kirkpatrick (September 19, 1905 – March 2, 2007). She was working for the manager of the baseball team for which he was playing at the time. They had four sons: Phillip, William, Richard, and John Thorpe. Kirkpatrick divorced Thorpe in 1941, after they had been married for 15 years.

Lastly, Thorpe married Patricia Gladys Askew on June 2, 1945. She was with him when he died.

Later life, film career, and death

After his athletic career, Thorpe struggled to provide for his family. He found it difficult to work a non-sports-related job and never held a job for an extended period of time. During the

After his athletic career, Thorpe struggled to provide for his family. He found it difficult to work a non-sports-related job and never held a job for an extended period of time. During the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

in particular, he had various jobs, among others as an extra

Extra or Xtra may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media Film

* ''The Extra'' (1962 film), a Mexican film

* ''The Extra'' (2005 film), an Australian film

Literature

* ''Extra'' (newspaper), a Brazilian newspaper

* ''Extra!'', an American me ...

for several movies, usually playing an American Indian chief in Westerns

The Western is a genre set in the American frontier and commonly associated with folk tales of the Western United States, particularly the Southwestern United States, as well as Northern Mexico and Western Canada. It is commonly referred ...

. In the 1932 comedy ''Always Kickin'', Thorpe was prominently cast in a speaking part as himself, a kicking coach teaching young football players to drop-kick

A drop kick is a type of kick in various codes of football. It involves a player dropping the ball and then kicking it as it touches the ground.

Drop kicks are used as a method of restarting play and scoring points in rugby union and rugby leagu ...

. In 1931, during the Great Depression, he sold the film rights to his life story to MGM for $1,500 ($ today). Thorpe portrayed an umpire in the 1940 film ''Knute Rockne, All American

''Knute Rockne, All American'' is a 1940 American biographical film that tells the story of Knute Rockne, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame's legendary football coach. It stars Pat O'Brien (actor), Pat O'Brien as Rockne and Ronald Reagan as pl ...

''. He played a member of the Navajo Nation in the 1950 film ''Wagon Master

''Wagon Master'' is a 1950 American Western film produced and directed by John Ford and starring Ben Johnson, Harry Carey Jr., Joanne Dru, and Ward Bond. The screenplay concerns a Mormon pioneer wagon train to the San Juan River in Utah. The ...

''.

Thorpe was memorialized in the Warner Bros. film '' Jim Thorpe – All-American'' (1951), starring Burt Lancaster

Burton Stephen Lancaster (November 2, 1913 – October 20, 1994) was an American actor and producer. Initially known for playing tough guys with a tender heart, he went on to achieve success with more complex and challenging roles over a 45-yea ...

. The film was directed by Michael Curtiz

Michael Curtiz ( ; born Manó Kaminer; since 1905 Mihály Kertész; hu, Kertész Mihály; December 24, 1886 April 10, 1962) was a Hungarian-American film director, recognized as one of the most prolific directors in history. He directed cla ...

. Although there were rumors that Thorpe received no money, he was paid $15,000 by Warner Bros. plus a $2,500 donation toward an annuity for him by the studio head of publicity. The movie included archival footage of the 1912 and 1932 Olympics. Thorpe was seen in one scene as a coaching assistant. It was also distributed in the United Kingdom, where it was called ''Man of Bronze''.

Apart from his career in films, he worked as a construction worker, a doorman/bouncer, a security guard, and a ditchdigger. He briefly joined the United States Merchant Marine

United States Merchant Marines are United States civilian mariners and U.S. civilian and federally owned merchant vessels. Both the civilian mariners and the merchant vessels are managed by a combination of the government and private sectors, an ...

in 1945, during World War II.O'Hanlon-Lincoln. pp. 144–145.Briefs''Time'', February 22, 1943, available online via time.com. Retrieved May 21, 2007. Thorpe was a chronic alcoholic during his later life. He ran out of money sometime in the early 1950s. When hospitalized for lip cancer in 1950, Thorpe was admitted as a charity case. At a press conference announcing the procedure, his wife, Patricia, wept and pleaded for help, saying, "We're broke ... Jim has nothing but his name and his memories. He has spent money on his own people and has given it away. He has often been exploited." In early 1953, Thorpe went into

heart failure

Heart failure (HF), also known as congestive heart failure (CHF), is a syndrome, a group of signs and symptoms caused by an impairment of the heart's blood pumping function. Symptoms typically include shortness of breath, excessive fatigue, ...

for the third time while dining with Patricia in their home in Lomita, California

Lomita (Spanish for "Little hill") is a city in Los Angeles County, California, United States. The population was 20,921 at the 2020 census, up from 20,256 at the 2010 census.

History

The Spanish Empire had expanded into this area when t ...

. He was briefly revived by artificial respiration

Artificial ventilation (also called artificial respiration) is a means of assisting or stimulating respiration, a metabolic process referring to the overall exchange of gases in the body by pulmonary ventilation, external respiration, and intern ...

and spoke to those around him, but lost consciousness shortly afterward. He died on March 28 at the age of 65.

Victim of racism

Thorpe, whose parents were both half Caucasian, was raised as a Native American. He accomplished his athletic feats despite the severe racial inequality of the United States. It has often been suggested that his Olympic medals were stripped by the athletic officials because of his ethnicity. While it is difficult to prove this, the public comment at the time largely reflected this view. At the time Thorpe won his gold medals, not all Native Americans were recognized as U.S. citizens (the U.S. government had frequently demanded that they make concessions to adopt European-American ways to receive such recognition). Citizenship was not granted to all American Indians until 1924. When Thorpe attended Carlisle, the students' ethnicity was used for marketing purposes. The football team was called the Indians. To create headlines, the school and journalists often portrayed sporting competitions as conflicts of Indians against whites.Bloom quoted in Bird. p. 97. The first notice of Thorpe in ''The New York Times'' was headlined "Indian Thorpe in Olympiad; Redskin from Carlisle Will Strive for Place on American Team." Throughout his life, Thorpe's accomplishments were described in a similar racial context by other newspapers and sportswriters, which reflected the era.Legacy

Olympic awards reinstated

Over the years, supporters of Thorpe attempted to have his Olympic titles reinstated. US Olympic officials, including former teammate and later president of the IOC

Over the years, supporters of Thorpe attempted to have his Olympic titles reinstated. US Olympic officials, including former teammate and later president of the IOC Avery Brundage

Avery Brundage (; September 28, 1887 – May 8, 1975) was an American sports administrator who served as the fifth president of the International Olympic Committee from 1952 to 1972. The only American and only non-European to attain that p ...

, rebuffed several attempts. Brundage once said, "Ignorance is no excuse." Most persistent were the author Robert Wheeler and his wife, Florence Ridlon. They succeeded in having the AAU and United States Olympic Committee

The United States Olympic & Paralympic Committee (USOPC) is the National Olympic Committee and the National Paralympic Committee for the United States. It was founded in 1895 as the United States Olympic Committee, and is headquartered in Col ...

overturn its decision and restore Thorpe's amateur status before 1913.

In 1982, Wheeler and Ridlon established the Jim Thorpe Foundation and gained support from the U.S. Congress. Armed with this support and evidence from 1912 proving that Thorpe's disqualification had occurred after the 30-day time period allowed by Olympics rules, they succeeded in making the case to the IOC. In October 1982, the IOC Executive Committee approved Thorpe's reinstatement. In an unusual ruling, they declared that Thorpe was co-champion with Ferdinand Bie

Ferdinand Reinhardt Bie (16 February 1888 – 9 November 1961) was a Norwegian track and field athlete. At the 1912 Summer Olympics in Stockholm he won the silver medal in pentathlon. On winner Jim Thorpe's subsequent disqualification for having ...

and Wieslander, although both of these athletes had always said they considered Thorpe to be the only champion. In a ceremony on January 18, 1983, the IOC presented two of Thorpe's children, Gale and Bill, with commemorative medals. Thorpe's original medals had been held in museums, but they were stolen and have never been recovered. The IOC listed Thorpe as a co-gold medalist.

In July 2020, a petition from Bright Path Strong began circulating that called upon the IOC to reinstate Thorpe as the sole winner in his events in the 1912 Olympics. It was backed by Pictureworks Entertainment, which is making a film about Thorpe. The petition was supported by Olympian Billy Mills, who won a gold medal in the 10,000 meters at the 1964 Tokyo Games. The IOC voted to reinstate Thorpe as the sole winner of both events on July 14, 2022.

Honors

Thorpe's monument, featuring the quote from Gustav V ("You, sir, are the greatest athlete in the world."), still stands near the town named for him,

Thorpe's monument, featuring the quote from Gustav V ("You, sir, are the greatest athlete in the world."), still stands near the town named for him, Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania

Jim Thorpe is a borough and the county seat of Carbon County in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. It is part of Northeastern Pennsylvania. It is historically known as the burial site of Native American sports legend Jim Thorpe.

Jim Thorpe is l ...

. The grave rests on mounds of soil from Thorpe's native Oklahoma and from the stadium in which he won his Olympic medals.

Thorpe's achievements received great acclaim from sports journalists, both during his lifetime and since his death. In 1950, an Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. new ...

poll of almost 400 sportswriters and broadcasters voted Thorpe the "greatest athlete" of the first half of the 20th century. That same year, the Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. new ...

ranked Thorpe as the "greatest American football player" of the first half of the century. Pro Football Hall of Fame

The Pro Football Hall of Fame is the hall of fame for professional American football, located in Canton, Ohio. Opened on September 7, , the Hall of Fame enshrines exceptional figures in the sport of professional football, including players, coa ...

voters selected him for the NFL 50th Anniversary All-Time Team The National Football League 50th Anniversary All-Time Team was selected in 1969 by Pro Football Hall of Fame voters from each franchise city of the National Football League (NFL) to honor the greatest players of the first 50 years of the league. ...

in 1967. In 1999, the Associated Press placed him third on its list of the top athletes of the century, following Babe Ruth

George Herman "Babe" Ruth Jr. (February 6, 1895 – August 16, 1948) was an American professional baseball player whose career in Major League Baseball (MLB) spanned 22 seasons, from 1914 through 1935. Nicknamed "the Bambino" and "the Su ...

and Michael Jordan

Michael Jeffrey Jordan (born February 17, 1963), also known by his initials MJ, is an American businessman and former professional basketball player. His biography on the official NBA website states: "By acclamation, Michael Jordan is the g ...

. ESPN

ESPN (originally an initialism for Entertainment and Sports Programming Network) is an American international basic cable sports channel owned by ESPN Inc., owned jointly by The Walt Disney Company (80%) and Hearst Communications (20%). The ...

ranked Thorpe seventh on their list of best North American athletes of the century.

Thorpe was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame

The Pro Football Hall of Fame is the hall of fame for professional American football, located in Canton, Ohio. Opened on September 7, , the Hall of Fame enshrines exceptional figures in the sport of professional football, including players, coa ...

in 1963, one of seventeen players in the charter class. Thorpe is memorialized in the Pro Football Hall of Fame rotunda with a larger-than-life statue. He was also inducted into halls of fame for college football, American Olympic teams, and the national track and field competition.

In 2018, Thorpe became one of the inductees in the first induction ceremony held by the National Native American Hall of Fame. The fitness center and a hall at Haskell Indian Nations University

Haskell Indian Nations University is a public tribal land-grant university in Lawrence, Kansas, United States. Founded in 1884 as a residential boarding school for American Indian children, the school has developed into a university operated by t ...

are named in honor of Thorpe.

President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

, as authorized by U.S. Senate Joint Resolution 73, proclaimed Monday, April 16, 1973, as "Jim Thorpe Day" to promote nationwide recognition of Thorpe's life. In 1986, the Jim Thorpe Association established an award with Thorpe's name. The Jim Thorpe Award

The Jim Thorpe Award, named in memory of multi-sport athlete Jim Thorpe, has been awarded to the top defensive back in college football since 1986. It is voted on by the Oklahoma Sports Hall of Fame. In 2017, the award became sponsored by Payco ...

is given annually to the best defensive back

In gridiron football, defensive backs (DBs), also called the secondary, are the players on the defensive side of the ball who play farthest back from the line of scrimmage. They are distinguished from the other two sets of defensive players, the ...

in college football

College football (french: Football universitaire) refers to gridiron football played by teams of student athletes. It was through college football play that American football in the United States, American football rules first gained populari ...

. The annual Thorpe Cup athletics meeting is named in his honor. The United States Postal Service

The United States Postal Service (USPS), also known as the Post Office, U.S. Mail, or Postal Service, is an independent agency of the executive branch of the United States federal government responsible for providing postal service in the ...

issued a 32¢ stamp on February 3, 1998, as part of the Celebrate the Century

Celebrate the Century is the name of a series of postage stamps made by the United States Postal Service featuring images recalling various important events in the 20th century in the United States.

stamp sheet series.

In a poll of sports fans published in 2000 by ABC Sports, Thorpe was voted the Greatest Athlete of the Twentieth Century; the pool of 15 other top athletes included Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali (; born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.; January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016) was an American professional boxer and activist. Nicknamed "The Greatest", he is regarded as one of the most significant sports figures of the 20th century, ...

, Babe Ruth

George Herman "Babe" Ruth Jr. (February 6, 1895 – August 16, 1948) was an American professional baseball player whose career in Major League Baseball (MLB) spanned 22 seasons, from 1914 through 1935. Nicknamed "the Bambino" and "the Su ...

, Jesse Owens

James Cleveland "Jesse" Owens (September 12, 1913March 31, 1980) was an American track and field athlete who won four gold medals at the 1936 Olympic Games.

Owens specialized in the sprints and the long jump and was recognized in his lif ...

, Wayne Gretzky

Wayne Douglas Gretzky ( ; born January 26, 1961) is a Canadian former professional ice hockey player and former head coach. He played 20 seasons in the National Hockey League (NHL) for four teams from 1979 to 1999. Nicknamed "the Great One ...

, Jack Nicklaus

Jack William Nicklaus (born January 21, 1940), nicknamed The Golden Bear, is a retired American professional golfer and golf course designer. He is widely considered to be one of the greatest golfers of all time. He won 117 professional tou ...

, and Michael Jordan

Michael Jeffrey Jordan (born February 17, 1963), also known by his initials MJ, is an American businessman and former professional basketball player. His biography on the official NBA website states: "By acclamation, Michael Jordan is the g ...

.

In 2018, Thorpe was honored on the Native American dollar

The Sacagawea dollar (also known as the "golden dollar") is a United States dollar coin introduced in 2000, although not minted for general circulation between 2002 to 2008 and again from 2012 onward because of its general unpopularity with th ...

coin; proposed designs were released in 2015.

Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania

After Thorpe's funeral was held at St. Benedict's Catholic Church in Shawnee, Oklahoma, his body lay in state at Fairview Cemetery. Residents had paid to have it returned to Shawnee by train from California. The people began a fund-raising effort to erect a memorial for Thorpe at the town's athletic park. Local officials had asked state legislators for funding, but a bill that included $25,000 for their proposal was vetoed by GovernorJohnston Murray

Johnston Murray (July 21, 1902 – April 16, 1974) was an American lawyer, politician, and the 14th governor of Oklahoma from 1951 to 1955. He was a member of the Democratic Party.

Murray was the first Native American to be elected as governor ...

.

Meanwhile, Thorpe's third wife, unbeknownst to the rest of his family, took Thorpe's body and had it shipped to Pennsylvania when she heard that the small Pennsylvania towns of Mauch Chunk and East Mauch Chunk were seeking to attract business. She made a deal with officials which, according to Thorpe's son Jack, was made by the widowed Patricia for monetary considerations. The towns "bought" Thorpe's remains, erected a monument to him at the grave, merged, and renamed the newly united town in his honor as Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania

Jim Thorpe is a borough and the county seat of Carbon County in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. It is part of Northeastern Pennsylvania. It is historically known as the burial site of Native American sports legend Jim Thorpe.

Jim Thorpe is l ...

. Thorpe had never been there. The monument site contains his tomb, two statues of him in athletic poses, and historical markers recounting his life story.

In June 2010, Jack Thorpe filed a federal lawsuit against the borough of Jim Thorpe, seeking to have his father's remains returned to his homeland and re-interred near other family members in Oklahoma. Citing the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), Pub. L. 101-601, 25 U.S.C. 3001 et seq., 104 Stat. 3048, is a United States federal law enacted on November 16, 1990.

The Act requires federal agencies and institutions tha ...

, Jack was arguing to bring his father's remains to the reservation in Oklahoma, to be buried near those of his father, sisters and brother, a mile from the place he was born. He claimed that the agreement between his stepmother and Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania, borough officials was made against the wishes of other family members, who want him buried in Native American land. Jack Thorpe died at 73 on February 22, 2011.

In April 2013, U.S. District Judge Richard Caputo ruled that Jim Thorpe borough amounts to a museum under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act ("NAGPRA"), and therefore is bound by that law. A lawyer for Bill and Richard Thorpe said the men would pursue the legal process to have their father's remains returned to Sac and Fox land in central Oklahoma. On October 23, 2014, the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit (in case citations, 3d Cir.) is a federal court with appellate jurisdiction over the district courts for the following districts:

* District of Delaware

* District of New Jersey

* East ...

reversed Judge Caputo's ruling. The appeals court held that Jim Thorpe borough is not a "museum", as that term is used in NAGPRA, and that the plaintiffs therefore could not invoke that federal statute to seek reinterment of Thorpe's remains. In NAGPRA language, "'museum' means any institution or State or local government agency (including any institution of higher learning) that receives Federal funds and has possession of, or control over, Native American cultural items." The Court of Appeals directed the trial court to enter a judgment in favor of the borough. The appeals court said Pennsylvania law allows the plaintiffs to ask a state court to order reburial of Thorpe's remains, but noted, "once a body is interred there is great reluctance in permitting same to be moved, absent clear and compelling reasons for such a move." On October 5, 2015, the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

refused to hear the matter, effectively bringing the legal process to an end.

Jim Thorpe Marathon

The Jim Thorpe Area Running Festival is a series of races started in 2019 in Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania. It includes a marathon, a 26.2 mile footrace that features a steady elevation drop from start to finish.See also

* * * *Citations

General and cited sources

* Bird, Elizabeth S. ''Dressing in Feathers: The Construction of the Indian in American Popular Culture''. Boulder: Westview Press, 1996. . * Bloom, John. ''There is a Madness in the Air: The 1926 Haskell Homecoming and Popular Representations of Sports in Federal and Indian Boarding Schools''. ed. in Bird. Boulder: Westview Press. 1996. . * Buford, Kate. ''Native American Son: The Life and Sporting Legend of Jim Thorpe''. Lincoln:University of Nebraska Press

The University of Nebraska Press, also known as UNP, was founded in 1941 and is an academic publisher of scholarly and general-interest books. The press is under the auspices of the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, the main campus of the Unive ...

, 2010.

* Cava, Pete (Summer 1992)"Baseball in the Olympics"