Jewish question on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Jewish question, also referred to as the Jewish problem, was a wide-ranging debate in 19th- and 20th-century

Werner Sombart praised Jews for their capitalism and presented the seventeenth–eighteenth century court Jews as integrated and a model for integration. By the turn of the twentieth century, the debate was still widely discussed. The

Werner Sombart praised Jews for their capitalism and presented the seventeenth–eighteenth century court Jews as integrated and a model for integration. By the turn of the twentieth century, the debate was still widely discussed. The

excerpt

* Roudinesco, Elisabeth (2013

''Returning to the Jewish Question''

London, Polity Press, p. 280 * Wolf, Lucien (1919

"Notes on the Diplomatic History of the Jewish Question"

Jewish Historical Society of England * The Jewish cause: an introduction to a different Israeli history – the subject's impact during the Holocaust *

Israeli Foreign Policy and the Jewish Question

{{DEFAULTSORT:Jewish Question National questions Jewish political status The Holocaust Adolf Hitler Karl Marx Debates about social issues Minority rights

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

an society that pertained to the appropriate status and treatment of Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

. The debate, which was similar to other " national questions", dealt with the civil, legal, national, and political status of Jews as a minority within society, particularly in Europe during the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries.

The debate began with Jewish emancipation

Jewish emancipation was the process in various nations in Europe of eliminating Jewish disabilities, e.g. Jewish quotas, to which European Jews were then subject, and the recognition of Jews as entitled to equality and citizenship rights. It in ...

in western and central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the a ...

an societies during the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

and after the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

. The debate's issues included the legal and economic Jewish disabilities (such as Jewish quota

A Jewish quota was a discriminatory racial quota designed to limit or deny access for Jews to various institutions. Such quotas were widespread in the 19th and 20th centuries in developed countries and frequently present in higher education, o ...

s and segregation), Jewish assimilation

Jewish assimilation ( he, התבוללות, ''hitbolelut'') refers either to the gradual cultural assimilation and social integration of Jews in their surrounding culture or to an ideological program in the age of emancipation promoting conf ...

, and Jewish Enlightenment.

The expression has been used by antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Ant ...

movements from the 1880s onwards, culminating in the Nazi phrase of the " Final Solution to the Jewish Question". Similarly, the expression was used by proponents for and opponents of the establishment of an autonomous Jewish homeland or a sovereign Jewish state.

History of "the Jewish question"

The term "Jewish question" was first used in Great Britain around 1750 when the expression was used during the debates related to the Jewish Naturalisation Act 1753. Freely available at According to Holocaust scholar Lucy Dawidowicz, the term "Jewish Question," as introduced inwestern Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

, was a neutral expression for the negative attitude toward the apparent and persistent singularity of the Jews as a people against the background of the rising political nationalism and new nation-state

A nation state is a political unit where the state and nation are congruent. It is a more precise concept than "country", since a country does not need to have a predominant ethnic group.

A nation, in the sense of a common ethnicity, may in ...

s. Dawidowicz writes that "the histories of Jewish emancipation and of European antisemitism are replete with proffered 'solutions to the Jewish question.'"

The question was next discussed in France () after the French Revolution in 1789. It was discussed in Germany in 1843 via Bruno Bauer

Bruno Bauer (; 6 September 180913 April 1882) was a German philosopher and theologian. As a student of G. W. F. Hegel, Bauer was a radical Rationalist in philosophy, politics and Biblical criticism. Bauer investigated the sources of the New Te ...

's treatise ("The Jewish Question"). He argued that Jews could achieve political emancipation only if they let go their religious consciousness, as he proposed that political emancipation required a secular state

A secular state is an idea pertaining to secularity, whereby a state is or purports to be officially neutral in matters of religion, supporting neither religion nor irreligion. A secular state claims to treat all its citizens equally regard ...

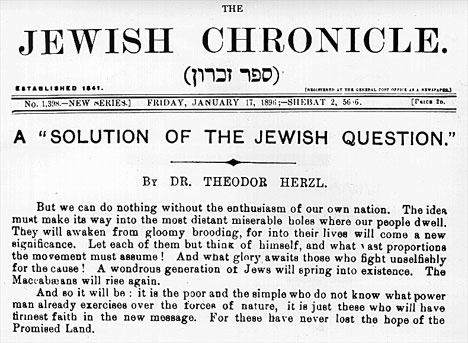

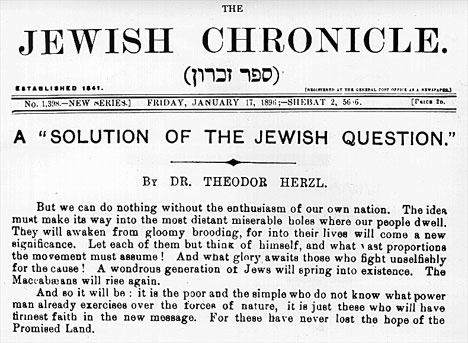

. In 1898, Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl; hu, Herzl Tivadar; Hebrew name given at his brit milah: Binyamin Ze'ev (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austro-Hungarian Jewish lawyer, journalist, playwright, political activist, and writer who was the father of modern po ...

's treatise, , advocates Zionism

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

as a "modern solution for the Jewish question" by creating an independent Jewish state, preferably in Palestine.

According to Otto Dov Kulka

Otto Dov Kulka (''Ôttô Dov Qûlqā''; 16 January 1933 in Nový Hrozenkov, Czechoslovakia – 29 January 2021 in Jerusalem) was an Israeli historian, professor emeritus of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His primary areas of specialization ...

of Hebrew University

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HUJI; he, הַאוּנִיבֶרְסִיטָה הַעִבְרִית בִּירוּשָׁלַיִם) is a public university, public research university based in Jerusalem, Israel. Co-founded by Albert Einstein ...

, the term became widespread in the 19th century when it was used in discussions about Jewish emancipation

Jewish emancipation was the process in various nations in Europe of eliminating Jewish disabilities, e.g. Jewish quotas, to which European Jews were then subject, and the recognition of Jews as entitled to equality and citizenship rights. It in ...

in Germany (). In the 19th century hundreds of tractates, pamphlets, newspaper articles and books were written on the subject, with many offering such solutions as resettlement, deportation, or assimilation of the Jewish population. Similarly, hundreds of works were written opposing these solutions and offering instead solutions such as re-integration and education. This debate however, could not decide whether the problem of the Jewish question had more to do with the problems posed by the German Jews' opponents or vice versa: the problem posed by the existence of the German Jews to their opponents.

From around 1860, the term was used with an increasingly antisemitic tendency: Jews were described under this term as a stumbling block to the identity and cohesion of the German nation and as enemies within the Germans' own country. Antisemites such as Wilhelm Marr, Karl Eugen Dühring, Theodor Fritsch, Houston Stewart Chamberlain, Paul de Lagarde

Paul Anton de Lagarde (2 November 1827 – 22 December 1891) was a German biblical scholar and orientalist, sometimes regarded as one of the greatest orientalists of the 19th century. Lagarde's strong support of anti-Semitism, vocal opposition t ...

and others declared it a racial problem insoluble through integration. They stressed this in order to strengthen their demands to "de-jewify" the press, education, culture, state and economy. They also proposed to condemn inter-marriage between Jews and non-Jews. They used this term to oust the Jews from their supposedly socially dominant positions.

The most infamous use of this expression was by the Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

s in the early- and mid-twentieth century. They implemented what they called their " Final Solution to the Jewish question" through the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, when they attempted to exterminate Jews in Europe.

Bruno Bauer – ''The Jewish Question''

In his book ''The Jewish Question

The Jewish question, also referred to as the Jewish problem, was a wide-ranging debate in 19th- and 20th-century European society that pertained to the appropriate status and treatment of Jews. The debate, which was similar to other "national ...

'' (1843), Bauer argued that Jews could only achieve political emancipation if they relinquish their particular religious consciousness. He believed that political emancipation requires a secular state

A secular state is an idea pertaining to secularity, whereby a state is or purports to be officially neutral in matters of religion, supporting neither religion nor irreligion. A secular state claims to treat all its citizens equally regard ...

, and such a state did not leave any "space" for social identities such as religion

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatur ...

. According to Bauer, such religious demands were incompatible with the idea of the " Rights of Man." True political emancipation, for Bauer, required the abolition of religion.

Karl Marx – ''On the Jewish Question''

Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

replied to Bauer in his 1844 essay '' On the Jewish Question''. Marx repudiated Bauer's view that the nature of the Jewish religion prevented assimilation by Jews. Instead, Marx attacked Bauer's very formulation of the question from "can the Jews become politically emancipated?" as fundamentally masking the nature of political emancipation itself.

Marx used Bauer's essay as an occasion for his own analysis of liberal rights. Marx argued that Bauer was mistaken in his assumption that in a "secular state

A secular state is an idea pertaining to secularity, whereby a state is or purports to be officially neutral in matters of religion, supporting neither religion nor irreligion. A secular state claims to treat all its citizens equally regard ...

", religion would no longer play a prominent role in social life. As an example, he referred to the pervasiveness of religion in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

, which, unlike Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

, had no state religion

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular, is not necessarily a t ...

. In Marx's analysis, the "secular state" was not opposed to religion, but rather assumed it. The removal of religious or property qualifications for citizenship did not mean the abolition of religion or property, but rather naturalized both and introduced a way of regarding individuals in abstraction from them.Marx 1844: On this note Marx moved beyond the question of religious freedom to his real concern with Bauer's analysis of "political emancipation." Marx concluded that while individuals can be 'politically' free in a secular state, they were still bound to material constraints on freedom by economic inequality, an assumption that would later form the basis of his critiques of capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

.

After Marx

Werner Sombart praised Jews for their capitalism and presented the seventeenth–eighteenth century court Jews as integrated and a model for integration. By the turn of the twentieth century, the debate was still widely discussed. The

Werner Sombart praised Jews for their capitalism and presented the seventeenth–eighteenth century court Jews as integrated and a model for integration. By the turn of the twentieth century, the debate was still widely discussed. The Dreyfus Affair

The Dreyfus affair (french: affaire Dreyfus, ) was a political scandal that divided the French Third Republic from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. "L'Affaire", as it is known in French, has come to symbolise modern injustice in the Francop ...

in France, believed to be evidence of anti-semitism, increased the prominence of this issue. Within the religious and political elite, some continued to favor assimilation and political engagement in Europe while others, such as Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl; hu, Herzl Tivadar; Hebrew name given at his brit milah: Binyamin Ze'ev (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austro-Hungarian Jewish lawyer, journalist, playwright, political activist, and writer who was the father of modern po ...

, proposed the advancement of a separate Jewish state and the Zionist

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

cause.

Josef Ringo

Josef Abramovich Ringo (russian: link=no, Иосиф Абрамович Ринго) was a Russian scientist, inventor, writer.

Life and career

Josef Ringo was born in Vitebsk in 1883. From 1905 until 1918 he studied and worked in both Switzerla ...

proposed the establishment of a Jewish state in his 1917 ''The Jewish question in its historical context and proposals for its solution'' ().

Between 1880 and 1920, millions of Jews created their own solution for the pogroms

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russian ...

of eastern Europe by emigration to other places, primarily the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

and western Europe.

The Nazi "Final Solution"

InNazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, the term ''Jewish Question'' (in german: Judenfrage) referred to the belief that the existence of Jews in Germany posed a problem for the state. In 1933 two Nazi theorists, Johann von Leers

Omar Amin (born Johann Jakob von Leers; 25 January 19025 March 1965) was an '' Alter Kämpfer'' and an honorary ''Sturmbannführer'' in the ''Waffen-SS'' in Nazi Germany, where he was also a professor known for his anti-Jewish polemics. He was o ...

and Achim Gercke

Achim Gercke (3 August 1902 – 27 October 1997) was a German politician.

Born in Greifswald, Gercke became a department head of the NSDAP in Munich on 1 January 1932. In April 1933 he was appointed to the Ministry of the Interior, where he ...

, both proposed the idea that the Jewish Question could be solved by resettling Jews in Madagascar, or somewhere else in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

or South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sou ...

. They also discussed the pros and cons of supporting the German Zionists. Von Leers asserted that establishing a Jewish homeland in Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine ( ar, فلسطين الانتدابية '; he, פָּלֶשְׂתִּינָה (א״י) ', where "E.Y." indicates ''’Eretz Yiśrā’ēl'', the Land of Israel) was a geopolitical entity established between 1920 and 1948 ...

would create humanitarian and political problems for the region.

Upon achieving power in 1933, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

and the Nazi state began to implement increasingly severe legislation that was aimed at segregating and ultimately removing Jews from Germany and (eventually) all of Europe. The next stage was the persecution of the Jews and the stripping of their citizenship through the 1935 Nuremberg Laws

The Nuremberg Laws (german: link=no, Nürnberger Gesetze, ) were antisemitic and racist laws that were enacted in Nazi Germany on 15 September 1935, at a special meeting of the Reichstag convened during the annual Nuremberg Rally of ...

. Starting with 1938 Kristallnacht pogrom and later, during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, it became state-sponsored internment in concentration camps. Finally the government implemented the systematic extermination of the Jewish people (The Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europ ...

), which took place as the so-called '' Final Solution to the Jewish Question''.

Nazi propaganda

The propaganda used by the German Nazi Party in the years leading up to and during Adolf Hitler's dictatorship of Germany from 1933 to 1945 was a crucial instrument for acquiring and maintaining power, and for the implementation of Nazi polici ...

was produced in order to manipulate the public, the most notable examples of which were based on the writings of people such as Eugen Fischer, Fritz Lenz and Erwin Baur in ''Foundations of Human Heredity Teaching and Racial Hygiene''. The work (''Allowing the Destruction of Life Unworthy of Living'') by Karl Binding

Karl Ludwig Lorenz Binding (4 June 1841 – 7 April 1920) was a German jurist known as a promoter of the theory of retributive justice. His influential book, ''Die Freigabe der Vernichtung lebensunwerten Lebens'' ("Allowing the Destruction of Life ...

and Alfred Hoche and the pseudo-scholarship that was promoted by Gerhard Kittel also played a role. In occupied France

The Military Administration in France (german: Militärverwaltung in Frankreich; french: Occupation de la France par l'Allemagne) was an interim occupation authority established by Nazi Germany during World War II to administer the occupied z ...

, the collaborationist regime established its own Institute for studying the Jewish Questions.

In the United States

A "Jewish problem" was euphemistically discussed in majority-European countries outside Europe, even as the Holocaust was in progress. American military officer and celebrity Charles A. Lindbergh used the phrase repeatedly in public speeches and writing. For example in his diary entry of September 18, 1941, published in 1970 as part of '' The Wartime Journals of Charles A. Lindbergh'', he wroteContemporary use

A dominant anti-Semitic conspiracy theory is the belief that Jewish people have undue influence over the media, banking, and politics. Based on this conspiracy theory, certain groups and activists discuss the "Jewish Question" and offer different proposals to address it. In the early 21st century, white nationalists,alt-right

The alt-right, an abbreviation of alternative right, is a far-right, white nationalist movement. A largely online phenomenon, the alt-right originated in the United States during the late 2000s before increasing in popularity during the mid-2 ...

ers, and neo-Nazis have used the initialism JQ in order to refer to the Jewish question."JQ stands for the 'Jewish Question,' an anti-Semitic conspiracy theory that Jewish people have undue influence over the media, banking and politics that must somehow be addressed" (Christopher Mathias, Jenna Amatulli, Rebecca Klein, 2018, ''The HuffPost'', 3 March 2018, https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/florida-public-school-teacher-white-nationalist-podcast_us_5a99ae32e4b089ec353a1fba)

See also

*Antisemitic canard

Antisemitic tropes, canards, or myths are " sensational reports, misrepresentations, or fabrications" that are defamatory towards Judaism as a religion or defamatory towards Jews as an ethnic or religious group. Since the Middle Ages, such repo ...

* Armenian question

* David Nirenberg § Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition

* German Question

* Irish question

* Martin Luther and antisemitism

* National question

* Negro Question

* Polish question

The Polish question ( pl, kwestia polska or ) was the issue, in international politics, of the existence of Poland as an independent state. Raised soon after the partitions of Poland in the late 18th century, it became a question current in Euro ...

* The Race Question

* Ulrich Fleischhauer

* Useful Jew

Notes

References

Further reading

* Case, Holly. ''The Age of Questions'' (Princeton University Press, 2018)excerpt

* Roudinesco, Elisabeth (2013

''Returning to the Jewish Question''

London, Polity Press, p. 280 * Wolf, Lucien (1919

"Notes on the Diplomatic History of the Jewish Question"

Jewish Historical Society of England * The Jewish cause: an introduction to a different Israeli history – the subject's impact during the Holocaust *

External links

Israeli Foreign Policy and the Jewish Question

{{DEFAULTSORT:Jewish Question National questions Jewish political status The Holocaust Adolf Hitler Karl Marx Debates about social issues Minority rights