Jeanne Sauvé on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jeanne Mathilde Sauvé (; April 26, 1922 – January 26, 1993) was a Canadian politician and journalist who served as

It was there that Sauvé met Maurice Sauvé, and the two married on September 24, 1948, the same year the couple moved to London; Maurice had obtained a scholarship to the

It was there that Sauvé met Maurice Sauvé, and the two married on September 24, 1948, the same year the couple moved to London; Maurice had obtained a scholarship to the

It was the

It was the

Sauvé was on May 14, 1984, sworn in as governor general in a ceremony in the Senate chamber, during which Trudeau said: "It is right and proper that Her Majesty should finally have a woman representative here", though stressing that the Queen had not appointed Sauvé simply because she was a woman. Almost immediately, Sauvé made it clear that she would use her time as vicereine to promote issues surrounding youth and world peace, as well as that of national unity.

The Governor General kept up to date with Cabinet papers and met every two weeks with her successive prime ministers. She would not speak openly about her relationship with these individuals, but there was reported friction between Sauvé and Brian Mulroney, whom she had appointed as her chief minister in 1984. It was speculated Sauvé disapproved of the way Mulroney elevated the stature of his office with more presidential trappings and aura, as exemplified by his insistence that he alone greet American President Ronald Reagan upon his arrival at

Sauvé was on May 14, 1984, sworn in as governor general in a ceremony in the Senate chamber, during which Trudeau said: "It is right and proper that Her Majesty should finally have a woman representative here", though stressing that the Queen had not appointed Sauvé simply because she was a woman. Almost immediately, Sauvé made it clear that she would use her time as vicereine to promote issues surrounding youth and world peace, as well as that of national unity.

The Governor General kept up to date with Cabinet papers and met every two weeks with her successive prime ministers. She would not speak openly about her relationship with these individuals, but there was reported friction between Sauvé and Brian Mulroney, whom she had appointed as her chief minister in 1984. It was speculated Sauvé disapproved of the way Mulroney elevated the stature of his office with more presidential trappings and aura, as exemplified by his insistence that he alone greet American President Ronald Reagan upon his arrival at  Also in her capacity as vicereine, in 1986 Sauvé accepted, on behalf of the "People of Canada", the Nansen Medal and, two years later, opened the

Also in her capacity as vicereine, in 1986 Sauvé accepted, on behalf of the "People of Canada", the Nansen Medal and, two years later, opened the

;Appointments

* January 4, 1973 – January 15, 1984:

;Appointments

* January 4, 1973 – January 15, 1984:

;Buildings

* : Fort Sauvé, Kingston

;Schools

* : '' Collège Jeanne-Sauvé'',

;Buildings

* : Fort Sauvé, Kingston

;Schools

* : '' Collège Jeanne-Sauvé'',

Governor General of Canada

The governor general of Canada (french: gouverneure générale du Canada) is the federal viceregal representative of the . The is head of state of Canada and the 14 other Commonwealth realms, but resides in oldest and most populous realm, ...

, the 23rd since Canadian Confederation

Canadian Confederation (french: Confédération canadienne, link=no) was the process by which three British North American provinces, the Province of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick, were united into one federation called the Dominion ...

.

Sauvé was born in Prud'homme, Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan ( ; ) is a province in western Canada, bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and on the south by the U.S. states of Montana and North Dak ...

, and educated in Ottawa and Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

, prior to working as a journalist for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (french: Société Radio-Canada), branded as CBC/Radio-Canada, is a Canadian public broadcaster for both radio and television. It is a federal Crown corporation that receives funding from the government. ...

(CBC). She was then elected to the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

in 1972, whereafter she served as a minister of the Crown until 1980, when she became the Speaker of the House of Commons Speaker of the House of Commons is a political leadership position found in countries that have a House of Commons, where the membership of the body elects a speaker to lead its proceedings.

Systems that have such a position include:

* Speaker of ...

. She was in 1984 appointed as governor general by Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

, on the recommendation of Prime Minister of Canada

The prime minister of Canada (french: premier ministre du Canada, link=no) is the head of government of Canada. Under the Westminster system, the prime minister governs with the confidence of a majority the elected House of Commons; as su ...

Pierre Trudeau, to replace Edward Schreyer

Edward Richard Schreyer (born December 21, 1935) is a Canadian politician, diplomat, and statesman who served as Governor General of Canada, the 22nd since Canadian Confederation.

Schreyer was born and educated in Manitoba, and was first electe ...

as vicereine

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning "k ...

, and she occupied the post until succeeded by Ray Hnatyshyn

Ramon John Hnatyshyn ( ; uk, Роман Іванович Гнатишин, Roman Ivanovych Hnatyshyn, ; March 16, 1934December 18, 2002) was a Canadian lawyer and statesman who served as governor general of Canada, the 24th since Canadian Co ...

in 1990. She was the first woman to serve as Canada's governor general and, while her appointment as the Queen's representative was initially and generally welcomed, Sauvé caused some controversy during her time as vicereine, mostly due to increased security around the office, as well as an anti-monarchist attitude towards the position.

On November 27, 1972, Sauvé was sworn into the Queen's Privy Council for Canada

The 's Privy Council for Canada (french: Conseil privé du Roi pour le Canada),) during the reign of a queen. sometimes called Majesty's Privy Council for Canada or simply the Privy Council (PC), is the full group of personal consultants to the ...

. She subsequently founded and worked with the Sauvé Foundation until her death, caused by Hodgkin's lymphoma

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is a type of lymphoma, in which cancer originates from a specific type of white blood cell called lymphocytes, where multinucleated Reed–Sternberg cells (RS cells) are present in the patient's lymph nodes. The condition w ...

, on January 26, 1993.

The highest trophy for the Canadian Ringette Championships

Canadian Ringette Championships, ''(french: Championnats Canadien d'Ringuette)'', sometimes abbreviated ''CRC'', is Canada's annual premiere national ringette tournament for the best ringette players and teams in the country. It encompasses three a ...

, the major national competition for the sport of ringette

Ringette is a non-contact winter team sport played on ice hockey rinks using ice hockey skates, straight sticks with drag-tips, and a blue, rubber, pneumatic ring designed for use on ice surfaces. The sport is among a small number of organize ...

, is named in her honour. Initially called the Jeanne Sauvé Cup, it was post-humously renamed the Jeanne Sauvé Memorial Cup.

Early life, youth, and first career

Sauvé was born in theFransaskois

Fransaskois (), (cf. Québécois people, Québécois), Franco-Saskatchewanais () or Franco-Saskatchewanians are French Canadians or Canadian francophones living in the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Saskatchewan. According to t ...

community of Prud'homme, Saskatchewan

Prud'homme (; 2016 population: ) is a village in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan within the Rural Municipality of Bayne No. 371 and Census Division No. 15. It is approximately northeast of Saskatoon. Prud'homme was first known by the n ...

, to Charles Albert Benoît and Anna Vaillant, and three years later moved with them to Ottawa, where her family had previously lived. In Ottawa, her father would take her to see the bronze bust on Parliament Hill

Parliament Hill (french: Colline du Parlement, colloquially known as The Hill, is an area of Crown land on the southern banks of the Ottawa River in downtown Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Its Gothic revival suite of buildings, and their archit ...

of Canada's first female Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

(MP), Agnes Macphail. Sauvé studied at Notre Dame du Rosaire Convent in Ottawa, becoming head of her class in her first year, and continued her education at the University of Ottawa

The University of Ottawa (french: Université d'Ottawa), often referred to as uOttawa or U of O, is a bilingual public research university in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. The main campus is located on directly to the northeast of Downtown Ottaw ...

, working for the government of Canada

The government of Canada (french: gouvernement du Canada) is the body responsible for the federal administration of Canada. A constitutional monarchy, the Crown is the corporation sole, assuming distinct roles: the executive, as the ''Crown ...

as a translator in order to pay her tuition. At the same time, Sauvé actively involved herself in student and political affairs; at the age of 20, she became the national president of the Young Catholic Students Group, which employed her in 1942, necessitating her move to Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple ...

.

It was there that Sauvé met Maurice Sauvé, and the two married on September 24, 1948, the same year the couple moved to London; Maurice had obtained a scholarship to the

It was there that Sauvé met Maurice Sauvé, and the two married on September 24, 1948, the same year the couple moved to London; Maurice had obtained a scholarship to the London School of Economics

The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) is a public university, public research university located in London, England and a constituent college of the federal University of London. Founded in 1895 by Fabian Society members Sidn ...

, and Sauvé worked as a teacher and tutor. Two years later, they moved to Paris, where Sauvé was employed as the assistant to the director of the Youth Secretariat at UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

, and in 1951, she enrolled for one year at the Sorbonne

Sorbonne may refer to:

* Sorbonne (building), historic building in Paris, which housed the University of Paris and is now shared among multiple universities.

*the University of Paris (c. 1150 – 1970)

*one of its components or linked institution, ...

, graduating with a degree in French civilization. Sauvé and her husband returned to Canada near the end of 1952, where the couple settled in Saint-Hyacinthe, Quebec

Saint-Hyacinthe (; French: ) is a city in southwestern Quebec east of Montreal on the Yamaska River. The population as of the 2021 Canadian census was 57,239. The city is located in Les Maskoutains Regional County Municipality of the Montér� ...

, and in 1959 had one child, Jean-François. Sauvé then became a founding member of the Institute of Political Research and was hired as a journalist and broadcaster with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (french: Société Radio-Canada), branded as CBC/Radio-Canada, is a Canadian public broadcaster for both radio and television. It is a federal Crown corporation that receives funding from the government. ...

's French-language broadcaster, Radio-Canada

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (french: Société Radio-Canada), branded as CBC/Radio-Canada, is a Canadian public broadcaster for both radio and television. It is a federal Crown corporation that receives funding from the government. ...

.

After success on her first radio programme, ''Fémina'', Sauvé was moved to CBC television and focused her efforts on covering political topics on both radio and television, in both English and French. She soon drew attention to herself and was frequently invited by her friend Gérard Pelletier as a panellist on the controversial show ''Les Idées en Marche'', there revealing her left-wing political ideologies. This absorption of a woman into the traditionally male world of political journalism and commentary was unusual, yet Sauvé managed to be taken seriously, even being given her own television show, ''Opinions'', which covered "such taboo subjects as teenage sex, parental authority, and student discipline". On air from 1956 to 1963, "it was the show that made Jeanne famous". However, Sauvé also attracted negative attention due to her husband's eventual elevation as a Crown minister; in a piece in ''The Globe and Mail

''The Globe and Mail'' is a Canadian newspaper printed in five cities in western and central Canada. With a weekly readership of approximately 2 million in 2015, it is Canada's most widely read newspaper on weekdays and Saturdays, although it ...

'', Progressive Conservative MP Louis-Joseph Pigeon

Louis-Joseph Pigeon (7 July 1922 – 2 March 1993) was a Progressive Conservative party member of the House of Commons of Canada. He was an agrologist by career, and worked for the Liberal minister of labour during the St Laurent government.

...

expressed concern over the wife of a minister being paid "fabulous sums by the CBC", calling the circumstances a "shame and a scandal".

Parliamentary career

It was the

It was the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

that wooed Sauvé into politics, asking her to run as a candidate in the Montreal riding of Ahuntsic during the 1972 federal election. Though she found campaigning arduous, saying: "I felt uneasy for the first time in my life when I was campaigning ... I must say I had qualms about it myself", Sauvé won, becoming one of five female MPs. She was subsequently both sworn into the Queen's Privy Council and appointed as Minister of State

Minister of State is a title borne by politicians in certain countries governed under a parliamentary system. In some countries a Minister of State is a Junior Minister of government, who is assigned to assist a specific Cabinet Minister. In ...

for Science and Technology in the Cabinet chaired by Pierre Trudeau, thus becoming the first woman from Quebec to become a minister of the Crown and the sole female in that Cabinet. Sauvé ran again in the election two years later, re-winning Ahuntsic, and was given the environment portfolio until 1975, when she was appointed Minister of Communications.

In the 1979 election, Sauvé won the riding of Laval-des-Rapides

Laval-des-Rapides is a district in Laval, Quebec, Canada. It was a separate city until the municipal mergers on August 6, 1965.

Geography

The neighbourhood is delimited on the north, north-west and west by Chomedey, on the east and north-eas ...

, but the Liberals lost their majority in the commons to the Progressive Conservative Party; she thus lost her Cabinet position. She remained MP for her riding after the federal election of 1980, which saw both the Liberals returned to majority position and Trudeau returned to position of prime minister, and Trudeau indicated Sauvé as his choice for the Speaker of the House of Commons Speaker of the House of Commons is a political leadership position found in countries that have a House of Commons, where the membership of the body elects a speaker to lead its proceedings.

Systems that have such a position include:

* Speaker of ...

. Because she strongly desired to campaign for the "No" forces in the weeks leading up to Quebec's 1980 referendum on separation from Canada, Sauvé initially refused the offer to run for the non-partisan position. But she eventually acquiesced after Trudeau convinced her that she was the right person for the job and she received permission from the leaders of all the parties in the House of Commons to engage in the federalist campaign in Quebec. She became the first female Speaker of the House.

In her early days as speaker, Sauvé often made mistakes with the names of MPs or the ridings they represented—once calling on the Prime Minister as the "leader of the opposition"—and occasionally miscarried procedural rulings, which led to MPs addressing her with increasing curtness. Further, all 32 of the New Democratic Party MPs in the house walked out in protest of what they viewed as a bias on Sauvé's part; they felt she allowed Liberal MPs to ask more questions than those from any other party. In a CBC interview, Sauvé conceded that the NDP members may have been right that the Liberals may have been allowed more questions over two or three days, but, on the whole, each party received an equal number of opportunities. It was also speculated that MPs had taken to showboating

A showboat, or show boat, was a floating theater that traveled along the waterways of the United States, especially along the Mississippi and Ohio rivers, to bring culture and entertainment to the inhabitants of river frontiers. Showboats were a ...

for the television cameras that had recently been installed in the chamber.

Sauvé did, however, find success in implementing reforms that professionalised the speaker's tasks of managing expenses and staff for the House of Commons, cutting back on the excess bureaucracy, personnel, overtime waste, and costs she discovered upon her installation. Once the changes were made, Sauvé had reduced the commons' support personnel by 300 and saved $18 million out of the annual expenses, all of which, to some, actually improved overall service. Sauvé was lauded, by MPs and the media alike, for her courage in challenging the establishment. Other MPs, though, stated that she had gone too far and balked at the resulting inconveniences, such as having to clear their own plates in the commons cafeteria. At the same time, Sauvé also established the first daycare

Child care, otherwise known as day care, is the care and supervision of a child or multiple children at a time, whose ages range from two weeks of age to 18 years. Although most parents spend a significant amount of time caring for their child(r ...

for Parliament Hill staff, MPs, and senators.

She also presided over debates on the constitution, dealing with filibusters and numerous points of order, as well as discussions over the proposed Energy Security Act

The Energy Security Act was signed into law by U.S. President Jimmy Carter on June 30, 1980. Thursday, 19 January 2017

It consisted of six major acts:

* U.S. Synthetic Fuels Corporation Act

* Biomass Energy and Alcohol Fuels Act

* Renewable Ener ...

, against which the loyal opposition

Loyal opposition in terms of politics, refers to specific political concepts that are related to the opposition parties of a particular political system. In many Westminster-style parliamentary systems of government, the loyal opposition indicate ...

mounted a counter-campaign that culminated in a two-week bell-ringing episode when the Conservatives' Whip refused to appear in the Commons to indicate that the opposition was ready for a vote. Despite pressure from the government that she intervene to break the deadlock, Sauvé maintained that it was up to the parties to resolve it themselves through negotiation.

Governor General of Canada

Sauvé was the first female governor general inCanada's history

''Canada's History'' () is the official magazine of Canada's National History Society. It is published six times a year and aims to foster greater popular interest in Canadian history.

Founded as ''The Beaver'' in 1920 by the Hudson's Bay Co ...

, and only the second woman amongst all the Commonwealth realms—both previous and contemporary to the time—to assume the equivalent office, after Elmira Minita Gordon

Dame Elmira Minita Gordon (30 December 1930 – 1 January 2021) was a Belizean educator, psychologist and politician; she served as the first governor general of Belize from its independence in 1981 until 1993. She was the first Belizean to r ...

, who was in 1981 appointed Governor-General of Belize

The governor-general of Belize is the vice-regal representative of the Belizean monarch, currently King Charles III, in Belize. The governor-general is appointed by the monarch on the recommendation of the prime minister of Belize. The function ...

.

As governor general-designate

It was in December 1983 announced from theOffice of the Prime Minister of Canada

The Prime Minister's Office (PMO; french: Cabinet du Premier minister; french: CPM, label=none) is the political arm of the staff housed in the Office of the Prime Minister and Privy Council building that supports the role of the Prime Minister o ...

that Trudeau had put forward Sauvé's name to Queen Elizabeth II as his recommendation on who should succeed Edward Schreyer as the Queen's representative. In the national media, the reception was generally positive, with Sauvé's elegance, refined nature, and bilingualism viewed as an asset to such a posting, despite speculation regarding her ability to remain non-partisan, as would be expected of the vicereine. However, by January 15, of the following year Sauvé resigned as an MP, and thus as speaker, and two days later she was hospitalised; rumours circulated that it was due to cancer, but the official story was that she had contracted a respiratory virus, which was further complicated by an allergy to antibiotics.

Still, Queen

Queen or QUEEN may refer to:

Monarchy

* Queen regnant, a female monarch of a Kingdom

** List of queens regnant

* Queen consort, the wife of a reigning king

* Queen dowager, the widow of a king

* Queen mother, a queen dowager who is the mother ...

Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

, by commission under the royal sign-manual

The royal sign-manual is the signature of the sovereign, by the affixing of which the monarch expresses his or her pleasure either by order, commission, or warrant. A sign-manual warrant may be either an executive act (for example, an appointmen ...

and Great Seal of Canada

The Great Seal of Canada (french: Grand Sceau du Canada) is a governmental seal used for purposes of state in Canada, being set on letters patent, proclamations and commissions, both to representatives of the monarch and for the appointment of ...

, appointed on January 28, 1984, Trudeau's recommendation that she appoint Sauvé as her representative. However, the latter remained in hospital, and her illness only worsened, leading colleagues to believe that she would die, and the Canadian Press and CBC to draft preliminary obituaries

An obituary (obit for short) is an article about a recently deceased person. Newspapers often publish obituaries as news articles. Although obituaries tend to focus on positive aspects of the subject's life, this is not always the case. Acc ...

. Sauvé did recover, and was released from care on March 3, though the illness had delayed her installation ceremony, which had been scheduled to take place that month. Sauvé remained secretive about the exact nature of the illness, and did not pay attention to rumours that she had developed Hodgkin's lymphoma

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is a type of lymphoma, in which cancer originates from a specific type of white blood cell called lymphocytes, where multinucleated Reed–Sternberg cells (RS cells) are present in the patient's lymph nodes. The condition w ...

, stating in interviews that it was a private matter, and that she was well enough to uphold her responsibilities.

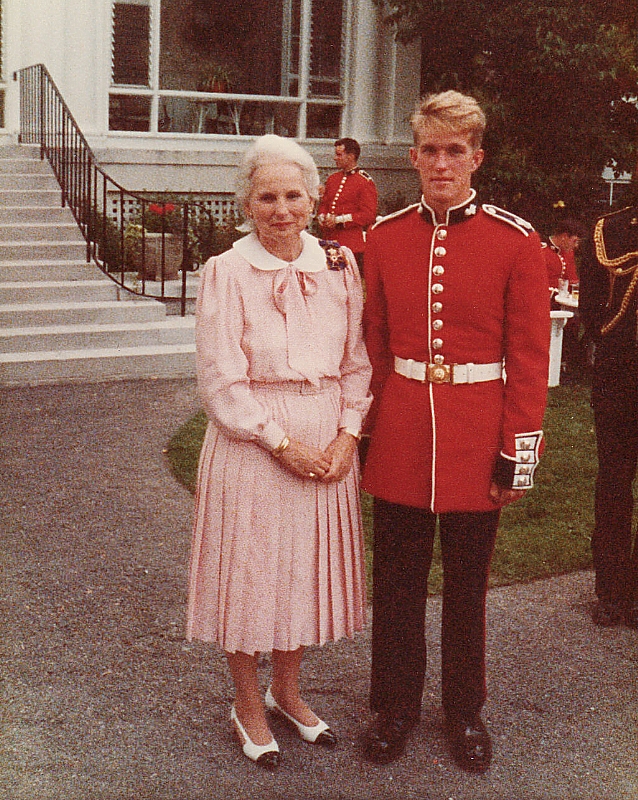

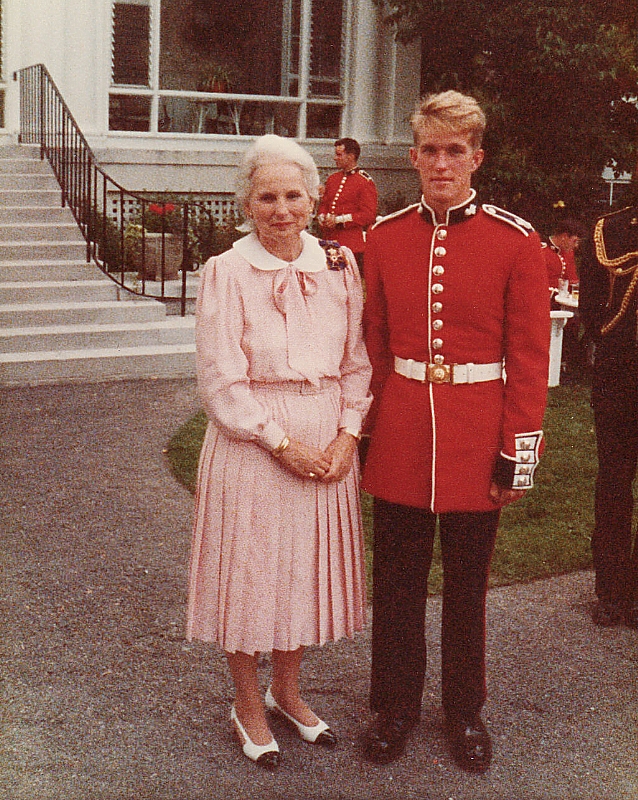

In office

Sauvé was on May 14, 1984, sworn in as governor general in a ceremony in the Senate chamber, during which Trudeau said: "It is right and proper that Her Majesty should finally have a woman representative here", though stressing that the Queen had not appointed Sauvé simply because she was a woman. Almost immediately, Sauvé made it clear that she would use her time as vicereine to promote issues surrounding youth and world peace, as well as that of national unity.

The Governor General kept up to date with Cabinet papers and met every two weeks with her successive prime ministers. She would not speak openly about her relationship with these individuals, but there was reported friction between Sauvé and Brian Mulroney, whom she had appointed as her chief minister in 1984. It was speculated Sauvé disapproved of the way Mulroney elevated the stature of his office with more presidential trappings and aura, as exemplified by his insistence that he alone greet American President Ronald Reagan upon his arrival at

Sauvé was on May 14, 1984, sworn in as governor general in a ceremony in the Senate chamber, during which Trudeau said: "It is right and proper that Her Majesty should finally have a woman representative here", though stressing that the Queen had not appointed Sauvé simply because she was a woman. Almost immediately, Sauvé made it clear that she would use her time as vicereine to promote issues surrounding youth and world peace, as well as that of national unity.

The Governor General kept up to date with Cabinet papers and met every two weeks with her successive prime ministers. She would not speak openly about her relationship with these individuals, but there was reported friction between Sauvé and Brian Mulroney, whom she had appointed as her chief minister in 1984. It was speculated Sauvé disapproved of the way Mulroney elevated the stature of his office with more presidential trappings and aura, as exemplified by his insistence that he alone greet American President Ronald Reagan upon his arrival at Quebec City

Quebec City ( or ; french: Ville de Québec), officially Québec (), is the capital city of the Canadian province of Quebec. As of July 2021, the city had a population of 549,459, and the metropolitan area had a population of 839,311. It is t ...

for the colloquially dubbed " Shamrock Summit". This was taken by the media as a snub against Sauvé who, as the head of state's direct representative, would otherwise have welcomed another head of state to Canada.

She did, however, greet members of the royal family, including the Queen and her husband, Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh (born Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark, later Philip Mountbatten; 10 June 1921 – 9 April 2021) was the husband of Queen Elizabeth II. As such, he served as the consort of the British monarch from E ...

; Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother; and the Duke and Duchess of York. Prince Edward met with Sauvé at Rideau Hall on June 4, 1988, to present the Governor General with royal Letters Patent permitting the federal viceroy to exercise the Queen's powers in respect of the granting of heraldic arms in Canada, leading to the eventual creation of the Canadian Heraldic Authority

The Canadian Heraldic Authority (CHA; french: Autorité héraldique du Canada) is part of the Canadian honours system under the Canadian monarch, whose authority is exercised by the Governor General of Canada. The authority is responsible for t ...

, of which Sauvé was the first head. Among foreign visitors welcomed by Sauvé were King Carl XVI Gustav of Sweden

Carl XVI Gustaf (Carl Gustaf Folke Hubertus; born 30 April 1946) is King of Sweden. He ascended the throne on the death of his grandfather, Gustaf VI Adolf, on 15 September 1973.

He is the youngest child and only son of Prince Gustaf Adolf, D ...

, Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands

Beatrix (Beatrix Wilhelmina Armgard, ; born 31 January 1938) is a member of the Dutch royal house who reigned as Queen of the Netherlands from 1980 until her abdication in 2013.

Beatrix is the eldest daughter of Queen Juliana and her husban ...

, King Hussein of Jordan

Hussein bin Talal ( ar, الحسين بن طلال, ''Al-Ḥusayn ibn Ṭalāl''; 14 November 1935 – 7 February 1999) was King of Jordan from 11 August 1952 until his death in 1999. As a member of the Hashemite dynasty, the royal family of ...

, Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II ( la, Ioannes Paulus II; it, Giovanni Paolo II; pl, Jan Paweł II; born Karol Józef Wojtyła ; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 1978 until his ...

, Secretary-General of the United Nations

The secretary-general of the United Nations (UNSG or SG) is the chief administrative officer of the United Nations and head of the United Nations Secretariat, one of the six principal organs of the United Nations.

The role of the secretary-g ...

Javier Pérez de Cuéllar

Javier Felipe Ricardo Pérez de Cuéllar de la Guerra (; ; 19 January 1920 – 4 March 2020) was a Peruvian diplomat and politician who served as the fifth Secretary-General of the United Nations from 1982 to 1991. He later served as Prime Mini ...

, President François Mitterrand of France, Chinese President Li Xiannian

Li Xiannian (pronounced ; 23 June 1909 – 21 June 1992) was a Chinese Communist military and political leader, President of the People's Republic of China (''de jure'' head of state) from 1983 to 1988 under Paramount Leader Deng Xiaoping and t ...

, Romanian President Nicolae Ceauşescu Nicolae may refer to:

* Nicolae (name), a Romanian name

* ''Nicolae'' (novel), a 1997 novel

See also

*Nicolai (disambiguation) Nicolai may refer to:

*Nicolai (given name) people with the forename ''Nicolai''

*Nicolai (surname) people with the s ...

, Mother Teresa

Mary Teresa Bojaxhiu, MC (; 26 August 1910 – 5 September 1997), better known as Mother Teresa ( sq, Nënë Tereza), was an Indian-Albanian Catholic nun who, in 1950, founded the Missionaries of Charity. Anjezë Gonxhe Bojaxhiu () was ...

, and, eventually, President Reagan. A number of these state visits were reciprocated when Sauvé travelled to represent the Queen in Italy, the Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Vatican City, the city-state ruled by the pope in Rome, including St. Peter's Basilica, Sistine Chapel, Vatican Museum

The Holy See

* The Holy See, the governing body of the Catholic Church and sovereign entity recognized ...

, the People's Republic of China, Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

, France, Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

, and Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

.

Also in her capacity as vicereine, in 1986 Sauvé accepted, on behalf of the "People of Canada", the Nansen Medal and, two years later, opened the

Also in her capacity as vicereine, in 1986 Sauvé accepted, on behalf of the "People of Canada", the Nansen Medal and, two years later, opened the XV Olympic Winter Games

The 1988 Winter Olympics, officially known as the XV Olympic Winter Games (french: XVes Jeux olympiques d'hiver) and commonly known as Calgary 1988 ( bla, Mohkínsstsisi 1988; sto, Wîchîspa Oyade 1988 or ; cr, Otôskwanihk 1998/; srs, Guts� ...

in Calgary, Alberta

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest Ter ...

. But, one of her favourite events that she hosted was the annual Christmas party for the Ottawa Boys & Girls Club and its French-language counterpart, the Patro d'Ottawa; the children came to Rideau Hall to visit with Santa Claus and attended a lunch in the Tent Room. Sauvé personally hosted and wore a paper party hat to celebrate the special occasion.

Ironically, as with the speculations about Sauvé's standing in protocol vis-a-vis Mulroney, the Governor General herself was accused of elevating her position above its traditional place; she was criticised for her own presidentialisation of the viceregal post, with pundits at the time saying she occupied "Republican Hall". For instance, it was revealed that Sauvé's staff had meddled in Lieutenant Governor of Saskatchewan

The lieutenant governor of Saskatchewan () is the viceregal representative in Saskatchewan of the , who operates distinctly within the province but is also shared equally with the ten other jurisdictions of Canada, as well as the other Commonw ...

Frederick Johnson's plans to host a dinner at Government House

Government House is the name of many of the official residences of governors-general, governors and lieutenant-governors in the Commonwealth and the remaining colonies of the British Empire. The name is also used in some other countries.

Gover ...

in Regina, at which the Governor General was to be a guest. Further, municipal event organisers were told that singing of the Royal Anthem was not allowed and the loyal toast

A loyal toast is a salute given to the sovereign monarch or head of state of the country in which a formal gathering is being given, or by expatriates of that country, whether or not the particular head of state is present. It is usually a mat ...

to the Queen was to be replaced with a toast to Sauvé, all of which not only disregarded precedent but also grated on prairie sensitivities.

In her final address as vicereine, at Christmas, 1989, some of Sauvé's words were perceived as veiled warning about the failure of the Meech Lake Accord

The Meech Lake Accord (french: Accord du lac Meech) was a series of proposed amendments to the Constitution of Canada negotiated in 1987 by Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and all 10 Canadian provincial premiers. It was intended to persuade the gov ...

and she was criticised for this suspected breach of neutrality. The Premier of Newfoundland

The premier of Newfoundland and Labrador is the first minister and head of government for the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. Since 1949, the premier's duties and office has been the successor to the ministerial position of the pri ...

at the time, Clyde Wells, said it was "inappropriate for the Crown to be intruding in political affairs that way" and Bill Dawson, a law professor at the University of Western Ontario

The University of Western Ontario (UWO), also known as Western University or Western, is a public research university in London, Ontario, Canada. The main campus is located on of land, surrounded by residential neighbourhoods and the Thames R ...

, described Sauvé's use of the word ''pact'' as "injudicious". This was a subject on which Sauvé and the Queen agreed; Elizabeth II had also publicly expressed on October 22 and 23, 1987 her personal support for the accord and received criticism from its opponents. Sauvé, though, always held that she had been speaking about Canadian unity in general and not the Meech Lake Accord in particular, or any side of the debate around it.

Legacy

During her time as vicereine, Sauvé established in commemoration of her state visit to Brazil the Governor General Jeanne Sauvé Fellowship, awarded each year to a Brazilian graduate student in Canadian studies. She also created two awards for students entering the field of special education and subsequently created the Sauvé Foundation in 2003 "to develop the leadership potential of promising youth from around the world", which was dedicated to the cause of youth excellence in Canada and is today headed by Jean-François. The Sauvé Scholars Program has brought groups of up to fourteen young people with demonstrated leadership potential each year to Montreal, where they attend classes at McGill University, work on individual projects and "enlarge their understanding of the world". The Sauvé Scholars, who have come from 44 countries around the world, enjoy a unique residential program at Maison Jeanne Sauvé, which constitutes a key part of their experience. For sporting endeavours, Sauvé formed the Jeanne Sauvé Trophy, for the world cup championship in women'sfield hockey

Field hockey is a team sport structured in standard hockey format, in which each team plays with ten outfield players and a goalkeeper. Teams must drive a round hockey ball by hitting it with a hockey stick towards the rival team's shooting ...

, and the Jeanne Sauvé Fair Play Award

Jeanne may refer to:

Places

* Jeanne (crater), on Venus

People

* Jeanne (given name)

* Joan of Arc (Jeanne d'Arc, 1412–1431)

* Joanna of Flanders (1295–1374)

* Joan, Duchess of Brittany (1319–1384)

* Ruth Stuber Jeanne (1910–2004), Americ ...

, to recognise national amateur athletes who best demonstrate fair play and non-violence in sport. Further, Sauvé encouraged a safer society in Canada by establishing the Governor General's Award for Safety in the Workplace.

In 1983, then President of the national organization for the sport of ringette

Ringette is a non-contact winter team sport played on ice hockey rinks using ice hockey skates, straight sticks with drag-tips, and a blue, rubber, pneumatic ring designed for use on ice surfaces. The sport is among a small number of organize ...

in Canada, Ringette Canada, Betty Shields, had the trophy for the Canadian Ringette Championships

Canadian Ringette Championships, ''(french: Championnats Canadien d'Ringuette)'', sometimes abbreviated ''CRC'', is Canada's annual premiere national ringette tournament for the best ringette players and teams in the country. It encompasses three a ...

named in her honour. The trophy was initiated in December 1984 and was first presented at the 1985 Canadian Ringette Championships in Dollard-des-Ormeaux, Québec. While Sauvé was alive the trophy was called the Jeanne Sauvé Cup. Post-humously it was renamed the Jeanne Sauvé Memorial Cup, which remains the trophy's namesake today.

Though there was some criticism in the final evaluations of her performance as governor general, mostly for a perceived aloofness and sense of self-importance—which her closing of the Rideau Hall estate to the public came to symbolise—Sauvé was also described as having been elegant, charming, and a person who could mingle well with common Canadians—especially children—while also maintaining a sense of the dignity of state. She was said to have enjoyed both entertaining and ceremony, two necessary parts of the role of the Queen's representative. However, she was pointed out unfavourably by Canadian monarchists for her republican attitudes, as illustrated in her stated opinion that the monarchy should be abolished.

Retirement and death

After departing Rideau Hall for the last time as governor general in 1990, Sauvé and her husband returned to Montreal, where she continued to work with the Sauvé Foundation. Only two years later, however, Maurice died, and Sauvé followed him on January 26, 1993, after a long battle with Hodgkin's lymphoma. The couple were both interred inNotre Dame des Neiges Cemetery

Notre Dame des Neiges Cemetery (french: Cimetière Notre-Dame-des-Neiges) is a rural cemetery located in the borough of Côte-des-Neiges-Notre-Dame-de-Grâce, Montreal, Quebec, Canada which was founded in 1854. The entrance and the grounds run a ...

in Montreal, and, one year following her death, Canada Post

Canada Post Corporation (french: Société canadienne des postes), trading as Canada Post (french: Postes Canada), is a Crown corporation that functions as the primary postal operator in Canada. Originally known as Royal Mail Canada (the opera ...

issued a postage stamp bearing an image of Sauvé.

Titles, styles, honours, and arms

Titles

* November 27, 1972 – May 14, 1984: The Honourable Jeanne Sauvé * May 14, 1984 – January 28, 1990: Her Excellency the Right Honourable Jeanne Sauvé, Governor General and Commander-in-Chief in and over Canada * January 28, 1990 – January 26, 1993: The Right Honourable Jeanne SauvéHonours

Sauvé's personal awards and decorations include:

Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

(MP)

* November 27, 1972 – January 26, 1993: Member of the Queen's Privy Council for Canada (PC)

* May 14, 1984 – January 28, 1990: Chancellor and Principal Companion of the Order of Canada (CC)

** January 28, 1990 – January 26, 1993: Companion of the Order of Canada (CC)

* May 14, 1984 – January 28, 1990: Chancellor and Commander of the Order of Military Merit (CMM)

** January 28, 1990 – January 26, 1993: Commander of the Order of Military Merit (CMM)

* May 14, 1984 – January 28, 1990: Dame of Justice, Prior, and Chief Officer in Canada of the Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem (DStJ)

** January 28, 1990 – January 26, 1993: Dame of Justice of the Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem (DStJ)

* May 14, 1984 – January 28, 1990: Chief Scout of Canada

* 1984 – January 26, 1993: Honorary Member of the Royal Military College of Canada Club

;Medals

* 1967: Canadian Centennial Medal

The Canadian Centennial Medal (french: Médaille du centenaire du Canada) is a commemorative medal struck by the Royal Canadian Mint in 1967 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Canadian Confederation and was awarded to Canadians who were ...

* 1977: Queen Elizabeth II Silver Jubilee Medal

* May 14, 1984: Canadian Forces Decoration

The Canadian Forces' Decoration (post-nominal letters "CD") is a Canadian award bestowed upon members of the Canadian Armed Forces who have completed twelve years of military service, with certain conditions. By convention, it is also given to t ...

(CD)

* 1992: Commemorative Medal for the 125th Anniversary of the Confederation of Canada

The 125th Anniversary of the Confederation of Canada Medal (french: Médaille commémorative du 125e anniversaire de la Confédération du Canada) is a commemorative medal struck by the Royal Canadian Mint to commemorate the 125th anniversary of ...

;Foreign honours

* 1989: ''Médaille de la Chancellerie des universités de Paris''

Honorary military appointments

* May 14, 1984 – January 28, 1990: Colonel ofthe Governor General's Horse Guards

The Governor General's Horse Guards is an armoured reconnaissance regiment in the Primary Reserve of the Canadian Army. The regiment is part of 4th Canadian Division's 32 Canadian Brigade Group and is based in Toronto, Ontario. It is the most sen ...

* May 14, 1984 – January 28, 1990: Colonel of the Governor General's Foot Guards

The Governor General's Foot Guards (GGFG) is the senior reserve infantry regiment in the Canadian Army. Located in Ottawa at the Cartier Square Drill Hall, the regiment is a Primary Reserve infantry unit, and the members are part-time soldiers.

...

* May 14, 1984 – January 28, 1990: Colonel of the Canadian Grenadier Guards

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the m ...

Honorary degrees

* 1986: Queen's University,Doctor of Laws

A Doctor of Law is a degree in law. The application of the term varies from country to country and includes degrees such as the Doctor of Juridical Science (J.S.D. or S.J.D), Juris Doctor (J.D.), Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.), and Legum Doctor ...

(LLD)

* 1987: Chulalongkorn University

Chulalongkorn University (CU, th, จุฬาลงกรณ์มหาวิทยาลัย, ), nicknamed Chula ( th, จุฬาฯ), is a public and autonomous research university in Bangkok, Thailand. The university was originally fo ...

, Doctor of Political Science

Political science is the scientific study of politics. It is a social science dealing with systems of governance and power, and the analysis of political activities, political thought, political behavior, and associated constitutions and la ...

(DPSci)

* 1991: University of Regina

The University of Regina is a public university, public research university located in Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada. Founded in 1911 as a private denominational high school of the Methodist Church of Canada, it began an association with the Unive ...

, Doctor of Laws (LLD)

Honorific eponyms

;Awards * : Jeanne Sauvé Undergraduate Scholarship,University of Alberta

The University of Alberta, also known as U of A or UAlberta, is a Public university, public research university located in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. It was founded in 1908 by Alexander Cameron Rutherford,"A Gentleman of Strathcona – Alexande ...

, Edmonton

* : Jeanne Sauvé Fair Play Award

Jeanne may refer to:

Places

* Jeanne (crater), on Venus

People

* Jeanne (given name)

* Joan of Arc (Jeanne d'Arc, 1412–1431)

* Joanna of Flanders (1295–1374)

* Joan, Duchess of Brittany (1319–1384)

* Ruth Stuber Jeanne (1910–2004), Americ ...

* : Governor General Jeanne Sauvé Fellowship

* : Jeanne Sauvé Memorial Cup

* : Jeanne Sauvé Trophy

;Geographic locations

* : Jeanne-Sauvé Park, Montreal

* : Jeanne-Sauvé District, Outremont

Outremont is an affluent residential borough (''arrondissement'') of the city of Montreal, Quebec, Canada. It consists entirely of the former city on the Island of Montreal in southwestern Quebec. The neighbourhood is inhabited largely by fran ...

;Buildings

* : Fort Sauvé, Kingston

;Schools

* : '' Collège Jeanne-Sauvé'',

;Buildings

* : Fort Sauvé, Kingston

;Schools

* : '' Collège Jeanne-Sauvé'', Winnipeg

Winnipeg () is the capital and largest city of the province of Manitoba in Canada. It is centred on the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, near the longitudinal centre of North America. , Winnipeg had a city population of 749, ...

* : ''École publique Jeanne-Sauvé

École may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* École, Savoi ...

'', Sudbury

* : '' Ecole Jeanne-Sauvé'', Orléans

Orléans (;"Orleans"

(US) and Jeanne Sauvé Catholic School, Stratford * : Jeanne Sauvé French Immersion Public School,

Web site of the Governor General of Canada entry for Jeanne Sauvé

Jeanne Sauvé Foundation

* , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Sauve, Jeanne 1922 births 1993 deaths Canadian women journalists Women members of the House of Commons of Canada Deaths from cancer in Quebec Companions of the Order of Canada Commanders of the Order of Military Merit (Canada) Journalists from Saskatchewan Dames of Justice of the Order of St John Fransaskois people Governors General of Canada Liberal Party of Canada MPs Members of the House of Commons of Canada from Quebec Members of the King's Privy Council for Canada Speakers of the House of Commons of Canada Women in Quebec politics Chancellors of Concordia University Canadian women viceroys Chief Scouts of Canada 20th-century Canadian women writers 20th-century Canadian non-fiction writers 20th-century Canadian women politicians Women legislative speakers Canadian women non-fiction writers Burials at Notre Dame des Neiges Cemetery Canadian expatriates in France

(US) and Jeanne Sauvé Catholic School, Stratford * : Jeanne Sauvé French Immersion Public School,

London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

* : Jeanne Sauvé French Immersion Public School, St. Catharines

* : Jeanne Sauvé French Immersion Public School, Oshawa

;Organisations

* : Jeanne Sauvé Family Service

* : Sauvé Foundation

* : Jeanne Sauvé House

;Events

* : Jeanne Sauvé Lecture Series

Arms

Archives

There is a Jeanne Sauvéfonds

In archival science, a fonds is a group of documents that share the same origin and that have occurred naturally as an outgrowth of the daily workings of an agency, individual, or organization. An example of a fonds could be the writings of a poe ...

at Library and Archives Canada.

See also

* Women in Canadian politics *List of elected or appointed female heads of state

The following is a list of women who have been elected or appointed head of state or government of their respective countries since the interwar period (1918–1939). The first list includes female presidents who are heads of state and may also ...

Notes

References

External links

Web site of the Governor General of Canada entry for Jeanne Sauvé

Jeanne Sauvé Foundation

* , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Sauve, Jeanne 1922 births 1993 deaths Canadian women journalists Women members of the House of Commons of Canada Deaths from cancer in Quebec Companions of the Order of Canada Commanders of the Order of Military Merit (Canada) Journalists from Saskatchewan Dames of Justice of the Order of St John Fransaskois people Governors General of Canada Liberal Party of Canada MPs Members of the House of Commons of Canada from Quebec Members of the King's Privy Council for Canada Speakers of the House of Commons of Canada Women in Quebec politics Chancellors of Concordia University Canadian women viceroys Chief Scouts of Canada 20th-century Canadian women writers 20th-century Canadian non-fiction writers 20th-century Canadian women politicians Women legislative speakers Canadian women non-fiction writers Burials at Notre Dame des Neiges Cemetery Canadian expatriates in France