Jean-Victor Poncelet on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jean-Victor Poncelet (; 1 July 1788 – 22 December 1867) was a French

Poncelet was born in

Poncelet was born in

''Traité des propriétés projectives des figures''

* (1826) ''Cours de mécanique appliqué aux machines'' * * (1829) ''Introduction à la mécanique industrielle'' * * * * (1862/64) ''Applications d'analyse et de géométrie'' * *

Mémoires de l'Académie nationale de Metz

1870 (50e année / 1868–1869; 2e série) pp. 101–159. * *

engineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considering the limit ...

and mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems.

Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, structure, space, models, and change.

History

On ...

who served most notably as the Commanding General of the École Polytechnique

École may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* École, Savoi ...

. He is considered a reviver of projective geometry

In mathematics, projective geometry is the study of geometric properties that are invariant with respect to projective transformations. This means that, compared to elementary Euclidean geometry, projective geometry has a different setting, ...

, and his work ''Traité des propriétés projectives des figures'' is considered the first definitive text on the subject since Gérard Desargues' work on it in the 17th century. He later wrote an introduction to it: ''Applications d'analyse et de géométrie''.

As a mathematician, his most notable work was in projective geometry

In mathematics, projective geometry is the study of geometric properties that are invariant with respect to projective transformations. This means that, compared to elementary Euclidean geometry, projective geometry has a different setting, ...

, although an early collaboration with Charles Julien Brianchon provided a significant contribution to Feuerbach's theorem

In the geometry of triangles, the incircle and nine-point circle of a triangle are internally tangent to each other at the Feuerbach point of the triangle. The Feuerbach point is a triangle center, meaning that its definition does not depend on th ...

. He also made discoveries about projective harmonic conjugates; relating these to the poles and polar lines associated with conic section

In mathematics, a conic section, quadratic curve or conic is a curve obtained as the intersection of the surface of a cone with a plane. The three types of conic section are the hyperbola, the parabola, and the ellipse; the circle is a spe ...

s. He developed the concept of parallel lines meeting at a point at infinity and defined the circular points at infinity that are on every circle of the plane. These discoveries led to the principle of duality, and the principle of continuity and also aided in the development of complex number

In mathematics, a complex number is an element of a number system that extends the real numbers with a specific element denoted , called the imaginary unit and satisfying the equation i^= -1; every complex number can be expressed in the fo ...

s.

As a military engineer, he served in Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's campaign against the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

in 1812, in which he was captured and held prisoner until 1814. Later, he served as a professor

Professor (commonly abbreviated as Prof.) is an academic rank at universities and other post-secondary education and research institutions in most countries. Literally, ''professor'' derives from Latin as a "person who professes". Professors ...

of mechanics

Mechanics (from Ancient Greek: μηχανική, ''mēkhanikḗ'', "of machines") is the area of mathematics and physics concerned with the relationships between force, matter, and motion among physical objects. Forces applied to object ...

at the École d'application in his home town of Metz

Metz ( , , lat, Divodurum Mediomatricorum, then ) is a city in northeast France located at the confluence of the Moselle and the Seille rivers. Metz is the prefecture of the Moselle department and the seat of the parliament of the Grand ...

, during which time he published ''Introduction à la mécanique industrielle'', a work he is famous for, and improved the design of turbines and water wheel

A water wheel is a machine for converting the energy of flowing or falling water into useful forms of power, often in a watermill. A water wheel consists of a wheel (usually constructed from wood or metal), with a number of blades or bucket ...

s. In 1837, a tenured 'Chaire de mécanique physique et expérimentale' was specially created for him at the Sorbonne (the University of Paris

, image_name = Coat of arms of the University of Paris.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of Arms

, latin_name = Universitas magistrorum et scholarium Parisiensis

, motto = ''Hic et ubique terrarum'' (Latin)

, mottoeng = Here and a ...

). In 1848, he became the commanding general of his ''alma mater'', the École Polytechnique

École may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* École, Savoi ...

. He is honoured by having his name listed among notable French engineers and scientists displayed around the first stage of the Eiffel tower

The Eiffel Tower ( ; french: links=yes, tour Eiffel ) is a wrought-iron lattice tower on the Champ de Mars in Paris, France. It is named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose company designed and built the tower.

Locally nicknamed "' ...

.

Biography

Birth, education, and capture (1788–1814)

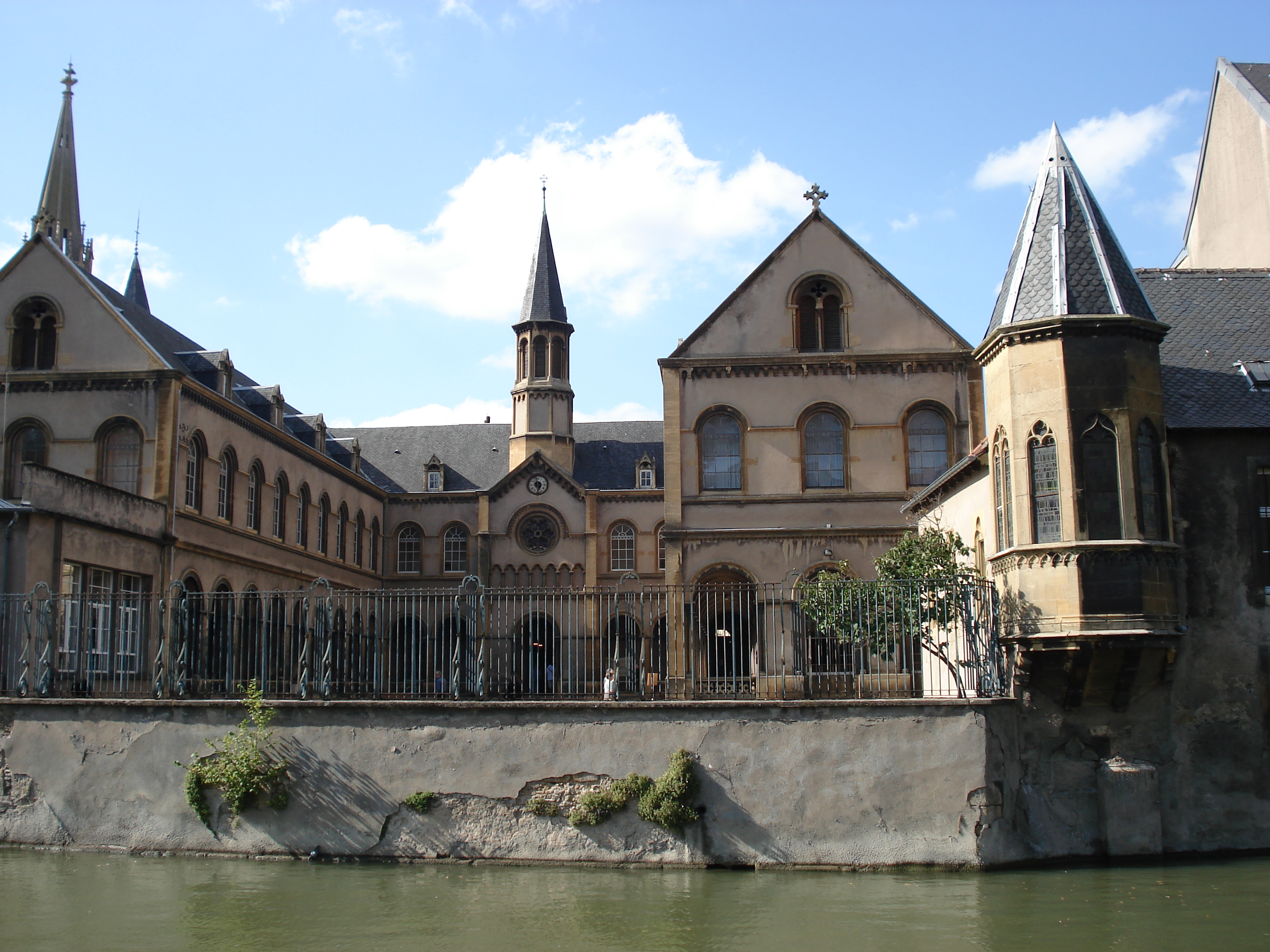

Metz

Metz ( , , lat, Divodurum Mediomatricorum, then ) is a city in northeast France located at the confluence of the Moselle and the Seille rivers. Metz is the prefecture of the Moselle department and the seat of the parliament of the Grand ...

, France, on 1 July 1788, the illegitimate

Legitimacy, in traditional Western common law, is the status of a child born to parents who are legally married to each other, and of a child conceived before the parents obtain a legal divorce. Conversely, ''illegitimacy'', also known as '' ...

then legitimated son of Claude Poncelet, a lawyer of the Parliament of Metz and wealthy landowner. His mother, Anne-Marie Perrein, had a more modest background. At a young age, he was sent to live with the Olier family at Saint-Avold.Didion 1870, p. 102 He returned to Metz for his secondary education, at Lycée Fabert

Lycée Fabert is a senior high school in Metz, Moselle department, Lorraine, France. The school, in the city centre, was the first lycée in Metz.

Facility

The high school consists of several buildings. They include:

* The old lycée called "l' ...

. After this, he attended the École Polytechnique

École may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* École, Savoi ...

, a prestigious school in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

, from 1808 to 1810, though he fell behind in his studies in his third year due to poor health. After graduation, he joined the Corps of Military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

Engineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considering the limit ...

s. He attended the École d'application in his hometown during this time, and achieved the rank of lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

in the French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (french: Armée de Terre, ), is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces. It is responsible to the Government of France, along with the other components of the Armed Force ...

the same year he graduated.

Poncelet took part in Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's invasion of Russia in 1812. His biographer Didion writes that he was part of the group which was cut from Marshal Michel Ney

Michel Ney, 1st Duke of Elchingen, 1st Prince of the Moskva (; 10 January 1769 – 7 December 1815), was a French military commander and Marshal of the Empire who fought in the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars. He was one o ...

's army at the Battle of Krasnoi and was forced to capitulate to the Russians,Didion 1870, p. 116 though other sources say that he was left for dead. Upon capture, he was interrogated by General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

Mikhail Andreyevich Miloradovich, but he did not disclose any information.Didion 1870, p. 166 The Russians held him as a prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

and confined him at Saratov. During his imprisonment, in the years 1812–1814, he wrote his most notable work, ''Traité des propriétés projectives des figures'', which outlined the foundations of projective geometry, as well as some new results. Poncelet, however, could not publish it until after his release in 1814.

Release and later employment (1822–1848)

In 1815, the year after his release, Poncelet was employed a military engineer at his hometown of Metz. In 1822, while at this position, he published ''Traité des propriétés projectives des figures''. This was the first major work to discussprojective geometry

In mathematics, projective geometry is the study of geometric properties that are invariant with respect to projective transformations. This means that, compared to elementary Euclidean geometry, projective geometry has a different setting, ...

since Desargues', though Gaspard Monge had written a few minor works about it previously. It is considered the founding work of modern projective geometry. Joseph Diaz Gergonne

Joseph Diez Gergonne (19 June 1771 at Nancy, France – 4 May 1859 at Montpellier, France) was a French mathematician and logician.

Life

In 1791, Gergonne enlisted in the French army as a captain. That army was undergoing rapid expansion becau ...

also wrote about this branch of geometry at approximately the same time, beginning in 1810. Poncelet published several papers about the subject in Annales de Gergonne

The ''Annales de Mathématiques Pures et Appliquées'', commonly known as the ''Annales de Gergonne'', was a mathematical journal published in Nimes, France from 1810 to 1831 by Joseph Diez Gergonne. The annals were largely devoted to geometry, ...

(officially known as ''Annales de mathématiques pures et appliquées''). However, Poncelet and Gergonne ultimately engaged in a bitter priority dispute over the Principle of Duality.

In 1825, he became the professor of mechanics

Mechanics (from Ancient Greek: μηχανική, ''mēkhanikḗ'', "of machines") is the area of mathematics and physics concerned with the relationships between force, matter, and motion among physical objects. Forces applied to object ...

at the École d'Application in Metz, a position he held until 1835. During his tenure at this school, he improved the design of turbines and water wheel

A water wheel is a machine for converting the energy of flowing or falling water into useful forms of power, often in a watermill. A water wheel consists of a wheel (usually constructed from wood or metal), with a number of blades or bucket ...

s, deriving his work from the mechanics of the Provençal mill from southern France. Although the turbine of his design was not constructed until 1838, he envisioned such a design twelve years previous to that. In 1835, he left École d'Application, and in December 1837 became a tenured professor at Sorbonne (the University of Paris

, image_name = Coat of arms of the University of Paris.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of Arms

, latin_name = Universitas magistrorum et scholarium Parisiensis

, motto = ''Hic et ubique terrarum'' (Latin)

, mottoeng = Here and a ...

), where a 'Chaire de mécanique physique et expérimentale' was specially created for him with the support of François Arago.

Commanding General at École Polytechnique (1848–1867)

In 1848, Poncelet became the Commanding General of his ''alma mater'', the École Polytechnique.Didion 1870, p. 101 He held the position until 1850, when he retired. During this time, he wrote ''Applications d'analyse et de géométrie'', which served as an introduction to his earlier work ''Traité des propriétés projectives des figures''. It was published in two volumes in 1862 and 1864. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of theAmerican Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, a ...

in 1865.

Contributions

Poncelet–Steiner theorem

Poncelet discovered the following theorem in 1822:Euclid

Euclid (; grc-gre, Εὐκλείδης; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the '' Elements'' treatise, which established the foundations of ...

ean compass and straightedge constructions can be carried out using only a straightedge if a single circle

A circle is a shape consisting of all points in a plane that are at a given distance from a given point, the centre. Equivalently, it is the curve traced out by a point that moves in a plane so that its distance from a given point is con ...

and its center is given. Swiss mathematician Jakob Steiner

Jakob Steiner (18 March 1796 – 1 April 1863) was a Swiss mathematician who worked primarily in geometry.

Life

Steiner was born in the village of Utzenstorf, Canton of Bern. At 18, he became a pupil of Heinrich Pestalozzi and afterwards st ...

proved this theorem in 1833, leading to the name of the theorem. The constructions that this theorem states are possible are known as Steiner constructions.

Poncelet's porism

Ingeometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is ...

, Poncelet's porism (sometimes referred to as Poncelet's closure theorem) states that whenever a polygon is inscribed in one conic section

In mathematics, a conic section, quadratic curve or conic is a curve obtained as the intersection of the surface of a cone with a plane. The three types of conic section are the hyperbola, the parabola, and the ellipse; the circle is a spe ...

and circumscribe

In geometry, the circumscribed circle or circumcircle of a polygon is a circle that passes through all the vertices of the polygon. The center of this circle is called the circumcenter and its radius is called the circumradius.

Not every polyg ...

s another one, the polygon must be part of an infinite family of polygons that are all inscribed in and circumscribe the same two conics.

List of selected works

* (1822''Traité des propriétés projectives des figures''

* (1826) ''Cours de mécanique appliqué aux machines'' * * (1829) ''Introduction à la mécanique industrielle'' * * * * (1862/64) ''Applications d'analyse et de géométrie'' * *

See also

* Poncelet, a unit of power named after him *Poncelet Prize

The Poncelet Prize (french: Prix Poncelet) is awarded by the French Academy of Sciences. The prize was established in 1868 by the widow of General Jean-Victor Poncelet for the advancement of the sciences. It was in the amount of 2,000 francs (as of ...

, a prize established in 1868 in his honor

Notes

References

* iMémoires de l'Académie nationale de Metz

1870 (50e année / 1868–1869; 2e série) pp. 101–159. * *

External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Poncelet, Jean-Victor 1788 births 1867 deaths École Polytechnique alumni Chevaliers of the Légion d'honneur Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Members of the French Academy of Sciences Foreign Members of the Royal Society Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) 19th-century French mathematicians Scientists from Metz French military personnel of the Napoleonic Wars Napoleonic Wars prisoners of war held by Russia French prisoners of war in the Napoleonic Wars