Japanese nuclear weapons program on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Japanese program to develop nuclear weapons was conducted during

In 1934,

In 1934,

The leading figure in the Japanese atomic program was Dr.

The leading figure in the Japanese atomic program was Dr.  Due to the German Japanese alliance resulting from Germany's 4-Year-Plan, Japan and its military had already been pursuing nuclear science to catch up to the West in nuclear technology. This allowed for Nishina to introduce quantum mechanics to Japan.

In 1939 Nishina recognized the military potential of nuclear fission, and was worried that the Americans were working on a nuclear weapon which might be used against Japan.

In August 1939, Hungarian-born physicists

Due to the German Japanese alliance resulting from Germany's 4-Year-Plan, Japan and its military had already been pursuing nuclear science to catch up to the West in nuclear technology. This allowed for Nishina to introduce quantum mechanics to Japan.

In 1939 Nishina recognized the military potential of nuclear fission, and was worried that the Americans were working on a nuclear weapon which might be used against Japan.

In August 1939, Hungarian-born physicists  In the early summer of 1940 Nishina met Lieutenant-General

In the early summer of 1940 Nishina met Lieutenant-General

After Arakatsu and Nishina's meeting, in Spring 1944 the Army-Navy Technology Enforcement Committee formed due to lack of progress in the development of Japanese nuclear weapons. This led to the only meeting of the leaders of the F-Go Project scientists, on July 21, 1945. After the meeting, nuclear weaponry research ended as a result of the destruction of the facility that housed isotope separation research, known as Building 49.

Shortly after the surrender of Japan, the

After Arakatsu and Nishina's meeting, in Spring 1944 the Army-Navy Technology Enforcement Committee formed due to lack of progress in the development of Japanese nuclear weapons. This led to the only meeting of the leaders of the F-Go Project scientists, on July 21, 1945. After the meeting, nuclear weaponry research ended as a result of the destruction of the facility that housed isotope separation research, known as Building 49.

Shortly after the surrender of Japan, the

Annotated bibliography of Japanese atomic bomb program from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues.FAS: Nuclear Weapons Program: Japan

Ćö

Japan's atomic bomb

History Channel International documentary

Japanese Nuclear Weapons Program during the WWIIJapan Plutonium Overhang Origins and Dangers Debated by U.S. Officials

published by the

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countriesŌĆöincluding all of the great power ...

. Like the German nuclear weapons program, it suffered from an array of problems, and was ultimately unable to progress beyond the laboratory stage before the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the onl ...

and the Japanese surrender

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally signed on 2 September 1945, bringing the war's hostilities to a close. By the end of July 1945, the Imperial Japanese Navy ( ...

in August 1945.

Today, Japan's nuclear energy infrastructure makes it capable of constructing nuclear weapons at will. The de-militarization of Japan and the protection of the United States' nuclear umbrella

The "nuclear umbrella" is a guarantee by a nuclear weapons state to defend a non-nuclear allied state. The context is usually the security alliances of the United States with Japan, South Korea, and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (m ...

have led to a strong policy of non-weaponization of nuclear technology, but in the face of nuclear weapons testing by North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu (Amnok) and T ...

, some politicians and former military officials in Japan are calling for a reversal of this policy.

Background

Tohoku University

, or is a Japanese national university located in Sendai, Miyagi in the T┼Źhoku Region, Japan. It is informally referred to as . Established in 1907, it was the third Imperial University in Japan and among the first three Designated Natio ...

professor Hikosaka Tadayoshi Hikosaka (written: ÕĮ”ÕØé) is a Japanese surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*, Japanese rugby sevens player

*, Japanese Go player

{{surname

Japanese-language surnames ...

's "atomic physics theory" was released. Hikosaka pointed out the huge energy contained by nuclei and the possibility that both nuclear power generation and weapons could be created.

In December 1938, the German chemists Otto Hahn

Otto Hahn (; 8 March 1879 ŌĆō 28 July 1968) was a German chemist who was a pioneer in the fields of radioactivity and radiochemistry. He is referred to as the father of nuclear chemistry and father of nuclear fission. Hahn and Lise Meitner ...

and Fritz Strassmann

Friedrich Wilhelm Strassmann (; 22 February 1902 ŌĆō 22 April 1980) was a German chemist who, with Otto Hahn in December 1938, identified the element barium as a product of the bombardment of uranium with neutrons. Their observation was the ke ...

sent a manuscript to ''Naturwissenschaften

''The Science of Nature'', formerly ''Naturwissenschaften'', is a monthly peer-reviewed scientific journal published by Springer Science+Business Media covering all aspects of the natural sciences relating to questions of biological significance. I ...

'' reporting that they had detected the element barium

Barium is a chemical element with the symbol Ba and atomic number 56. It is the fifth element in group 2 and is a soft, silvery alkaline earth metal. Because of its high chemical reactivity, barium is never found in nature as a free element.

Th ...

after bombarding uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weak ...

with neutrons

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , which has a neutral (not positive or negative) charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. Protons and neutrons constitute the nuclei of atoms. Since protons and neutrons behave ...

; simultaneously, they communicated these results to Lise Meitner

Elise Meitner ( , ; 7 November 1878 ŌĆō 27 October 1968) was an Austrian-Swedish physicist who was one of those responsible for the discovery of the element protactinium and nuclear fission. While working at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute on r ...

. Meitner, and her nephew Otto Robert Frisch

Otto Robert Frisch FRS (1 October 1904 ŌĆō 22 September 1979) was an Austrian-born British physicist who worked on nuclear physics. With Lise Meitner he advanced the first theoretical explanation of nuclear fission (coining the term) and first ...

, correctly interpreted these results as being nuclear fission

Nuclear fission is a reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into two or more smaller nuclei. The fission process often produces gamma photons, and releases a very large amount of energy even by the energetic standards of radio ...

and Frisch confirmed this experimentally on 13 January 1939. Physicists around the world immediately realized that chain reactions could be produced and notified their governments of the possibility of developing nuclear weapons.

World War II

Yoshio Nishina

was a Japanese physicist who was called "the founding father of modern physics research in Japan". He led the efforts of Japan to develop an atomic bomb during World War II.

Early life and career

Nishina was born in Satosh┼Ź, Okayama. He rece ...

, a close associate of Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr (; 7 October 1885 ŌĆō 18 November 1962) was a Danish physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum theory, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922 ...

and a contemporary of Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 ŌĆō 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theor ...

. Nishina had co-authored the KleinŌĆōNishina formula. Nishina had established his own Nuclear Research Laboratory to study high-energy physics

Particle physics or high energy physics is the study of fundamental particles and forces that constitute matter and radiation. The fundamental particles in the universe are classified in the Standard Model as fermions (matter particles) a ...

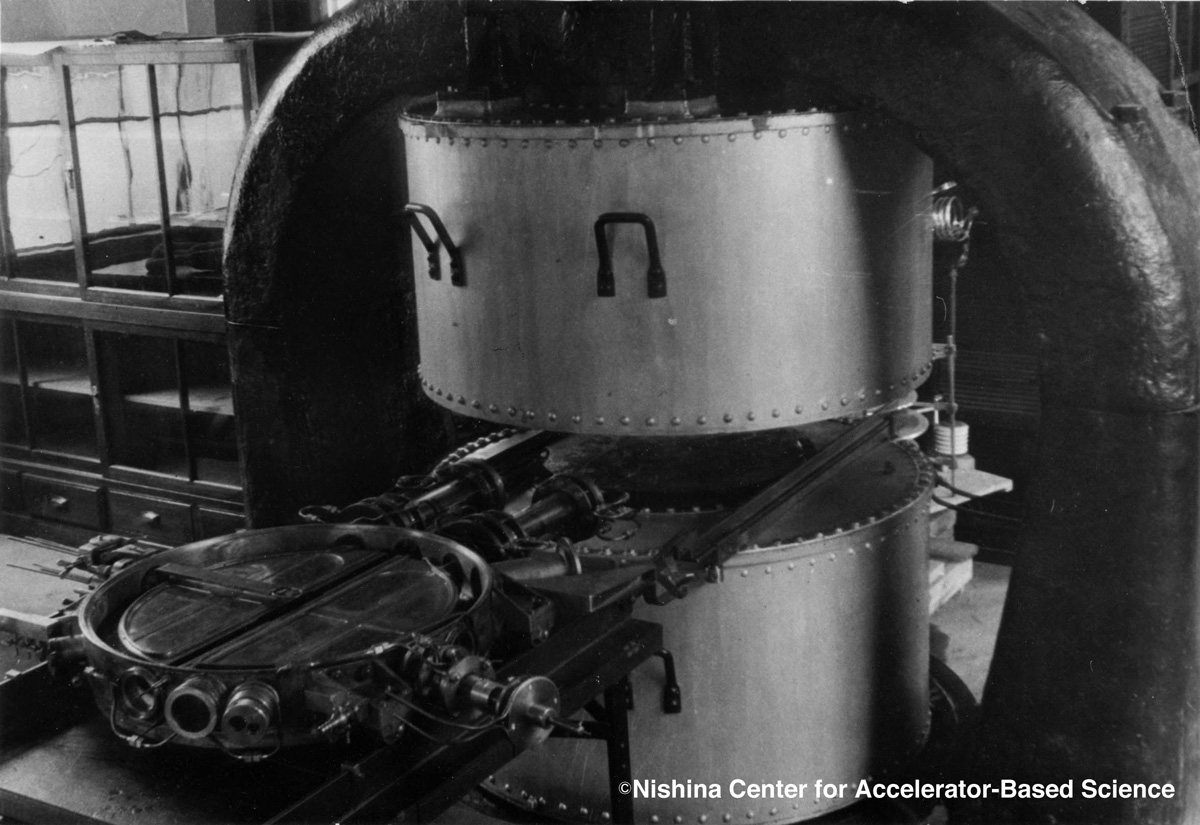

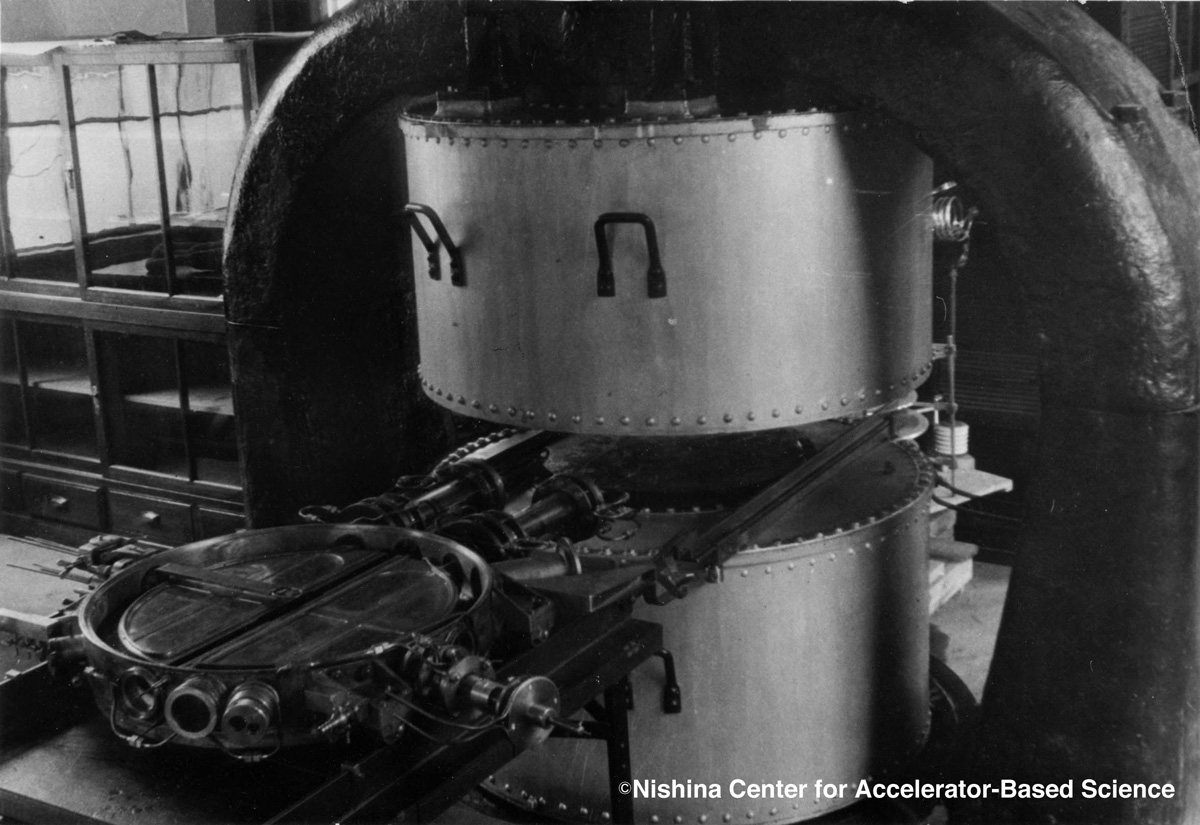

in 1931 at RIKEN Institute (the Institute for Physical and Chemical Research), which had been established in 1917 in Tokyo to promote basic research. Nishina had built his first cyclotron

A cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator invented by Ernest O. Lawrence in 1929ŌĆō1930 at the University of California, Berkeley, and patented in 1932. Lawrence, Ernest O. ''Method and apparatus for the acceleration of ions'', filed: Jan ...

in 1936, and another , 220-ton cyclotron in 1937. In 1938 Japan also purchased a cyclotron from the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant un ...

.

Due to the German Japanese alliance resulting from Germany's 4-Year-Plan, Japan and its military had already been pursuing nuclear science to catch up to the West in nuclear technology. This allowed for Nishina to introduce quantum mechanics to Japan.

In 1939 Nishina recognized the military potential of nuclear fission, and was worried that the Americans were working on a nuclear weapon which might be used against Japan.

In August 1939, Hungarian-born physicists

Due to the German Japanese alliance resulting from Germany's 4-Year-Plan, Japan and its military had already been pursuing nuclear science to catch up to the West in nuclear technology. This allowed for Nishina to introduce quantum mechanics to Japan.

In 1939 Nishina recognized the military potential of nuclear fission, and was worried that the Americans were working on a nuclear weapon which might be used against Japan.

In August 1939, Hungarian-born physicists Leo Szilard

Leo Szilard (; hu, Szil├Īrd Le├│, pronounced ; born Le├│ Spitz; February 11, 1898 ŌĆō May 30, 1964) was a Hungarian-German-American physicist and inventor. He conceived the nuclear chain reaction in 1933, patented the idea of a nuclear ...

and Eugene Wigner

Eugene Paul "E. P." Wigner ( hu, Wigner Jen┼æ P├Īl, ; November 17, 1902 ŌĆō January 1, 1995) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who also contributed to mathematical physics. He received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1963 "for his co ...

drafted the EinsteinŌĆōSzilard letter, which warned of the potential development of "extremely powerful bombs of a new type".

The United States started the investigations into fission weapons in the United States, which eventually evolved into the massive Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, and the laboratory from which Japan purchased a cyclotron became one of the major sites for weapons research.

In the early summer of 1940 Nishina met Lieutenant-General

In the early summer of 1940 Nishina met Lieutenant-General Takeo Yasuda

was a lieutenant general in the Imperial Japanese Army. While serving as director of the Army's Aviation Technology Research Institute during World War II, he was a key figure in scientific and technological development for the Imperial Japane ...

on a train. Yasuda was at the time director of the Army Aeronautical Department's Technical Research Institute. Nishina told Yasuda about the possibility of building nuclear weapons. However, the Japanese fission project did not formally begin until April 1941 when Yasuda acted on Army Minister Hideki T┼Źj┼Ź

Hideki Tojo (, ', December 30, 1884 ŌĆō December 23, 1948) was a Japanese politician, general of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA), and convicted war criminal who served as prime minister of Japan and president of the Imperial Rule Assista ...

's order to investigate the possibilities of nuclear weapons. Yasuda passed the order down the chain of command to Viscount Masatoshi ┼īk┼Źchi

Viscount was a Japanese physicist and business executive. He was the third director of the Riken Institute, a position which he assumed in 1921 and held for 25 years. During this period, he was notable for establishing the ''Riken Konzern'', ...

, director of the RIKEN Institute, who in turn passed it to Nishina, whose Nuclear Research Laboratory by 1941 had over 100 researchers.

B-Research

Meanwhile, the Imperial Japanese Navy's Technology Research Institute had been pursuing its own separate investigations, and had engaged professors from the Imperial University, Tokyo, for advice on nuclear weapons. Before the Attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, Captain Yoji Ito of the Naval Technical Research Institution of Japan initiated a study that would allow for the Japanese Navy to use nuclear fission. After consulting with Professor Sagane at Tokyo Imperial University, his research showed that nuclear fission would be a potential power source for the Navy. This resulted in the formation of the Committee on Research in the Application of Nuclear Physics, chaired by Nishina, that met ten times between July 1942 and March 1943. After the Japanese Navy lost at Midway, Captain Ito proposed a new type of nuclear weapons development designated as "B-Research" (also called "Jin Project", ja, õ╗üĶ©łńö╗, lit. "Nuclear Project") by the end of June 1942. By December, deep in the project, it became evident that while an atomic bomb was feasible in principle, "Japanese scientists believed that it would be difficult for even the United States to realize the application of atomic energy in time to influence the outcome of the war." This caused the Navy to lose interest and to concentrate instead on research intoradar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, Marine radar, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor v ...

.

Ni-Go Project

The Army was not discouraged, and soon after the Committee issued its report it set up an experimental project at RIKEN, the Ni-Go Project (lit. "The Second Project"). Its aim was to separateuranium-235

Uranium-235 (235U or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exi ...

by thermal diffusion, ignoring alternative methods such as electromagnetic separation, gaseous diffusion, and centrifugal separation

Centrifugation is a mechanical process which involves the use of the centrifugal force to separate particles from a solution according to their size, shape, density, medium viscosity and rotor speed. The denser components of the mixture migrate ...

.

By Spring 1944, the Nishina Project barely made any progress due to insufficient uranium hexafluoride for its Clusius tube. The previously provided uranium within the copper tube had corroded and the project was unable to separate U-235 isotopes.

By February 1945, a small group of scientists had succeeded in producing a small amount of material in a rudimentary separator in the RIKEN complexŌĆömaterial which RIKEN's cyclotron indicated was ''not'' uranium-235. The separator project came to an end in March 1945, when the building housing it was destroyed by a fire caused by the USAAF's ''Operation Meetinghouse'' raid on Tokyo. No attempt was made to build a uranium pile; heavy water was unavailable, but Takeuchi Masa, who was in charge of Nishina's separator, calculated that light water would suffice if the uranium could be enriched to 5ŌĆō10% uranium-235.

While these experiments were in progress, the Army and Navy searched for uranium ore, in locations ranging from Fukushima Prefecture

Fukushima Prefecture (; ja, ń”ÅÕ│Čń£ī, Fukushima-ken, ) is a prefecture of Japan located in the T┼Źhoku region of Honshu. Fukushima Prefecture has a population of 1,810,286 () and has a geographic area of . Fukushima Prefecture borders Miyagi ...

to Korea, China, and Burma. The Japanese also requested materials from their German allies and of unprocessed uranium oxide

Uranium oxide is an oxide of the element uranium.

The metal uranium forms several oxides:

* Uranium dioxide or uranium(IV) oxide (UO2, the mineral uraninite or pitchblende)

* Diuranium pentoxide or uranium(V) oxide (U2O5)

* Uranium trioxide o ...

was dispatched to Japan in April 1945 aboard the submarine , which however surrendered to US forces in the Atlantic following Germany's surrender. The uranium oxide was reportedly labeled as "U-235", which may have been a mislabeling of the submarine's name and its exact characteristics remain unknown; some sources believe that it was not weapons-grade material and was intended for use as a catalyst in the production of synthetic methanol

Methanol (also called methyl alcohol and wood spirit, amongst other names) is an organic chemical and the simplest aliphatic alcohol, with the formula C H3 O H (a methyl group linked to a hydroxyl group, often abbreviated as MeOH). It is ...

to be used for aviation fuel.

The attack also effectively destroyed the Clusius tube and any chances of the Japanese producing an atomic bomb in time to influence the war in their favor and rival the West in nuclear weaponry.

According to the historian Williams, "The same lack of sufficient high quality uranium that had impeded the German atomic project had also, as it turned out, obstructed Japanese attempts to make a bomb." This was the conclusion of the Manhattan Project Intelligence Group, who also reported Japan's nuclear physicists were just as good as those from other nations.

F-Go Project

In 1943 a different Japanese naval command began a nuclear research program, the F-Go Project (lit. "The F Project"), under Bunsaku Arakatsu at the Imperial University, Kyoto. Arakatsu had spent some years studying abroad including at theCavendish Laboratory

The Cavendish Laboratory is the Department of Physics at the University of Cambridge, and is part of the School of Physical Sciences. The laboratory was opened in 1874 on the New Museums Site as a laboratory for experimental physics and is named ...

at Cambridge under Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson, (30 August 1871 ŌĆō 19 October 1937) was a New Zealand physicist who came to be known as the father of nuclear physics.

''Encyclop├”dia Britannica'' considers him to be the greatest ...

and at Berlin University

Humboldt-Universit├żt zu Berlin (german: Humboldt-Universit├żt zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a German public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin. It was established by Frederick William III on the initiative o ...

under Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 ŌĆō 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theor ...

. Next to Nishina, Arakatsu was the most notable nuclear physicist in Japan. His team included Hideki Yukawa

was a Japanese theoretical physicist and the first Japanese Nobel laureate for his prediction of the pi meson, or pion.

Biography

He was born as Hideki Ogawa in Tokyo and grew up in Kyoto with two older brothers, two older sisters, and two yo ...

, who would become in 1949 the first Japanese physicist to receive a Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

.

Early on in the war Commander Kitagawa, head of the Navy Research Institute's Chemical Section, had requested Arakatsu to carry out work on the separation of Uranium-235. The work went slowly, but shortly before the end of the war he had designed an ultracentrifuge (to spin at 60,000 rpm) which he was hopeful would achieve the required results. Only the design of the machinery was completed before the Japanese surrender.

After Arakatsu and Nishina's meeting, in Spring 1944 the Army-Navy Technology Enforcement Committee formed due to lack of progress in the development of Japanese nuclear weapons. This led to the only meeting of the leaders of the F-Go Project scientists, on July 21, 1945. After the meeting, nuclear weaponry research ended as a result of the destruction of the facility that housed isotope separation research, known as Building 49.

Shortly after the surrender of Japan, the

After Arakatsu and Nishina's meeting, in Spring 1944 the Army-Navy Technology Enforcement Committee formed due to lack of progress in the development of Japanese nuclear weapons. This led to the only meeting of the leaders of the F-Go Project scientists, on July 21, 1945. After the meeting, nuclear weaponry research ended as a result of the destruction of the facility that housed isotope separation research, known as Building 49.

Shortly after the surrender of Japan, the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

's Atomic Bomb Mission, which had deployed to Japan in September, reported that the F-Go Project had obtained 20 grams a month of heavy water from electrolytic ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous ...

plants in Korea and Kyushu

is the third-largest island of Japan's five main islands and the most southerly of the four largest islands ( i.e. excluding Okinawa). In the past, it has been known as , and . The historical regional name referred to Kyushu and its surround ...

. In fact, the industrialist Jun Noguchi had launched a heavy water production program some years previously. In 1926, Noguchi founded the Korean Hydro Electric Company at Konan (now known as Hungnam

H┼Łngnam is a district of Hamhung, the second largest city in North Korea. It is a port city on the eastern coast on the Sea of Japan. It is only from the slightly inland city of Hamhung. In 2005 it became a ward of Hamhung.

History

The port a ...

) in north-eastern Korea: this became the site of an industrial complex producing ammonia for fertilizer production. However, despite the availability of a heavy-water production facility whose output could potentially have rivalled that of Norsk Hydro

Norsk Hydro ASA (often referred to as just ''Hydro'') is a Norwegian aluminium and renewable energy company, headquartered in Oslo. It is one of the largest aluminium companies worldwide. It has operations in some 50 countries around the world a ...

at Vemork in Norway, it appears that the Japanese did not carry out neutron-multiplication studies using heavy water as a moderator at Kyoto.

Postwar aftermath

On 16 October 1945 Nishina sought permission from the American occupation forces to use the twocyclotron

A cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator invented by Ernest O. Lawrence in 1929ŌĆō1930 at the University of California, Berkeley, and patented in 1932. Lawrence, Ernest O. ''Method and apparatus for the acceleration of ions'', filed: Jan ...

s at the Riken Institute for biological and medical research, which was soon granted; however, on 10 November instructions were received from the US Secretary of War in Washington to destroy the cyclotrons at the Riken, Kyoto University, and Osaka University. This was done on 24 November; the Riken's cyclotrons were taken apart and thrown into Tokyo Bay.Maas and Hogg, pp. 198-199

In a letter of protest against this destruction Nishina wrote that the cyclotrons at the Riken had had nothing to do with the production of nuclear weapons, however the large cyclotron had officially been a part of the Ni-Go Project. Nishina had placed it within the Project by suggesting that the cyclotron could serve basic research for the use of nuclear power, simply so that he could continue working on the device; the military nature of the Project gave him access to funding and kept his researchers from being drafted into the armed forces. He felt no qualms about this because he saw no possibility of producing nuclear weapons in Japan before the end of the war.

Reports of a Japanese weapon test

On October 2, 1946 the ''Atlanta Constitution

''The Atlanta Journal-Constitution'' is the only major daily newspaper in the metropolitan area of Atlanta, Georgia. It is the flagship publication of Cox Enterprises. The ''Atlanta Journal-Constitution'' is the result of the merger between ...

'' published a story by reporter David Snell, who had been an investigator with the 24th Criminal Investigation Detachment in Korea after the war, which alleged that the Japanese had successfully tested a nuclear weapon near Hungnam

H┼Łngnam is a district of Hamhung, the second largest city in North Korea. It is a port city on the eastern coast on the Sea of Japan. It is only from the slightly inland city of Hamhung. In 2005 it became a ward of Hamhung.

History

The port a ...

(Konan) before the town was captured by the Soviets. He said that he had received his information at Seoul in September 1945 from a Japanese officer to whom he gave the pseudonym of Captain Wakabayashi, who had been in charge of counter-intelligence at Hungnam.Dees, pp. 20-21 SCAP

SCAP may refer to:

* S.C.A.P., an early French manufacturer of cars and engines

* Security Content Automation Protocol

* '' The Shackled City Adventure Path'', a role-playing game

* SREBP cleavage activating protein

* Supervisory Capital Assessm ...

officials, who were responsible for strict censorship of all information about Japan's wartime interest in nuclear physics, were dismissive of Snell's report.

Under the 1947-48 investigation, comments were sought from Japanese scientists who would or should have known about such a project. Further doubt is cast on Snell's story by the lack of evidence of large numbers of Japanese scientists leaving Japan for Korea and never returning. Snell's statements were repeated by Robert K. Wilcox in his 1985 book '' Japan's Secret War: Japan's Race Against Time to Build Its Own Atomic Bomb''. The book also included what Wilcox stated was new evidence from intelligence material which indicated the Japanese might have had an atomic program at Hungnam. These specific reports were dismissed in a review of the book by Department of Energy A Ministry of Energy or Department of Energy is a government department in some countries that typically oversees the production of fuel and electricity; in the United States, however, it manages nuclear weapons development and conducts energy-re ...

employee Roger M. Anders which was published in the journal ''Military Affairs'', an article written by two historians of science in the journal ''Isis'', and another article in the journal ''Intelligence and National Security''. On the other hand, Wilcox issued a new expanded edition of his book in 2019, elaborating the bomb's development in detail and corroborating his account using additional information that had emerged, including documents that had been declassified in the meantime.

In 1946 talking about his wartime efforts Arakatsu said he was making "tremendous strides" towards making an atomic bomb and that the Soviet Union probably already had one.

Postwar

Since the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan has been a staunch upholder of antinuclear sentiments. Its postwarConstitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these pr ...

forbids the establishment of offensive military forces, and in 1967 it adopted the Three Non-Nuclear Principles, ruling out the production, possession, or introduction of nuclear weapons. Despite this, the idea that Japan might become a nuclear power has persisted. After China's first nuclear test in 1964, Japanese Prime Minister Eisaku Sat┼Ź

was a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister from 1964 to 1972. He is the third-longest serving Prime Minister, and ranks second in longest uninterrupted service as Prime Minister.

Sat┼Ź entered the National Diet in 1949 as a membe ...

said to President Lyndon Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

when they met in January 1965, that if the Chinese Communists had nuclear weapons, the Japanese should also have them. This shocked Johnson's administration, especially when Sato added that "Japanese public opinion will not permit this at present, but I believe that the public, especially the younger generation, can be 'educated'."

Throughout Sato's administration Japan continued to discuss the nuclear option. It was suggested that tactical nuclear weapon

A tactical nuclear weapon (TNW) or non-strategic nuclear weapon (NSNW) is a nuclear weapon that is designed to be used on a battlefield in military situations, mostly with friendly forces in proximity and perhaps even on contested friendly territo ...

s, as opposed to larger strategic weapons, could be defined as defensive, and therefore be allowed by the Japanese Constitution. A White Paper commissioned by future Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone opined that it would be possible that possessing small-yield, purely defensive nuclear weapons would not violate the Constitution, but that in view of the danger of adverse foreign reaction and possible war, a policy would be followed of not acquiring nuclear weapons "at present".

Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty

The Johnson administration became anxious about Sato's intentions and made securing Japan's signature to theNuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty

The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, commonly known as the Non-Proliferation Treaty or NPT, is an international treaty whose objective is to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and weapons technology, to promote cooperation ...

(NPT) one of its top priorities. In December 1967, to reassure the Japanese public, Sato announced the adoption of the Three Non-Nuclear Principles. These were that Japan would not manufacture, possess, or permit nuclear weapons on Japanese soil. The principles, which were adopted by the Diet, but are not law, have remained the basis of Japan's nuclear policy ever since.

According to Kei Wakaizumi

Kei may refer to:

People

* Kei (given name)

* Kei, Cantonese for Ji(Õ¦½)

* Kei, Cantonese for Qi(Õźć, ńźü, õ║ō)

* Sh┼Ź Kei (1700ŌĆō1752), king of the Ry┼½ky┼½ Kingdom

* Kei (singer) (born 1995), stage name of South Korean singer Kim Ji-yeon

* ...

, one of Sato's policy advisers, Sato realized soon after making the declaration that it might be too constraining. He therefore clarified the principles in a February 1968 address to the Diet by declaring the "Four Nuclear Policies" ("Four-Pillars Nuclear Policy"):

* Promotion of the peaceful use of nuclear energy

* Efforts towards global nuclear disarmament

* Reliance and dependence on US extended deterrence, based on the 1960 US-Japan Security Treaty

* Support for the "Three Non-Nuclear Principles under the circumstances where Japan's national security is guaranteed by the other three policies."

It followed that if American assurance was ever removed or seemed unreliable, Japan might have no choice but to go nuclear. In other words, it kept the nuclear option available.

In 1969 a policy planning study for Japan's Foreign Ministry concluded that Japan should, even if it signed the NPT, maintain the economic and technical ability to develop and produce nuclear weapons in case it should ever become necessary, for example due to the international situation.

Japan finally signed the NPT in 1970 and ratified it in 1976, but only after West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 ...

became a signatory and the US promised "not to interfere with Tokyo's pursuit of independent reprocessing capabilities in its civilian nuclear power program".

Extension of Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty

In 1995 theClinton administration

Bill Clinton's tenure as the 42nd president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1993, and ended on January 20, 2001. Clinton, a Democrat from Arkansas, took office following a decisive election victory over ...

pushed the Japanese government to endorse the indefinite extension of the NPT, but it opted for an ambiguous position on the issue. A former Japanese government official recalled, "We thought it was better for us not to declare that we will give up our nuclear option forever and ever". However, eventually pressure from Washington and other nations led to Japan's supporting the indefinite extension.

In 1998 two events strengthened the hand of those in Japan advocating that the nation should at least reconsider if not reverse its non-nuclear policy. Advocates of such policies included conservative academics, some government officials, a few industrialists, and nationalist groups.

The first of these events was India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

and Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

both conducting nuclear tests; the Japanese were troubled by a perceived reluctance on the part of the international community to condemn the two countries' actions, since one of the reasons Japan had opted to join the NPT was that it had anticipated severe penalties for those states who defied the international consensus against further nuclear proliferation. Also, Japan and other nations feared that an Indian nuclear arsenal could cause a localized nuclear arms race with China.

The second event was the August 1998 launch of a North Korean Taepodong-1

Taepodong-1 ( ko, ļīĆĒżļÅÖ-1) was a three-stage technology demonstrator developed by North Korea, a development step toward an intermediate-range ballistic missile. The missile was derived originally from the Scud rocket and was tested once in 1 ...

missile over Japan which caused a public outcry and led some to call for remilitarization or the development of nuclear weapons. Fukushiro Nukaga

is a Japanese politician and a member of the Liberal Democratic Party. He has been a member of the House of Representatives since 1983 and represents Ibaraki's 2nd district.Japan Defense Agency

The is an executive department of the Government of Japan responsible for preserving the peace and independence of Japan, and maintaining the countryŌĆÖs national security and the Japan Self-Defense Forces.

The ministry is headed by the Mi ...

, said that his government would be justified in mounting pre-emptive strikes against North Korean missile bases. Prime Minister Keiz┼Ź Obuchi

was a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan from 1998 to 2000.

Obuchi was elected to the House of Representatives in Gunma Prefecture in 1963, becoming the youngest legislator in Japanese history, and was re-elected to his ...

reiterated Japan's non-nuclear weapon principles and said that Japan would not possess a nuclear arsenal, and that the matter was not even worthy of discussion.

However, it is thought that Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi

Junichiro Koizumi (; , ''Koizumi Jun'ichir┼Ź'' ; born 8 January 1942) is a former Japanese politician who was Prime Minister of Japan and President of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) from 2001 to 2006. He retired from politics in 2009. He is ...

implied he agreed that Japan had the right to possess nuclear weapons when he added, "it is significant that although we could have them, we don't".

Earlier, Shinz┼Ź Abe

Shinzo Abe ( ; ja, Õ«ēÕĆŹ µÖŗõĖē, Hepburn: , ; 21 September 1954 ŌĆō 8 July 2022) was a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan and President of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) from 2006 to 2007 and again from 2012 to 20 ...

had said that Japan's constitution did not necessarily ban possession of nuclear weapons, so long as they were kept at a minimum and were tactical weapons, and Chief Cabinet Secretary Yasuo Fukuda had expressed a similar view.

De facto nuclear state

While there are currently no known plans in Japan to produce nuclear weapons, it has been argued Japan has the technology, raw materials, and the capital to produce nuclear weapons within one year if necessary, and many analysts consider it a ''de facto'' nuclear state for this reason. For this reason Japan is often said to be a "screwdriver's turn" away from possessing nuclear weapons, or to possess a "bomb in the basement". The United States stored extensive nuclear assets inOkinawa prefecture

is a prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 km2 (880 sq mi).

Naha is the capital and largest cit ...

when it was under American administration until the 1970s. There were approximately 1,200 nuclear warheads in Okinawa.

Significant amounts of reactor-grade plutonium Reactor-grade plutonium (RGPu) is the isotopic grade of plutonium that is found in spent nuclear fuel after the uranium-235 primary fuel that a nuclear power reactor uses has burnt up. The uranium-238 from which most of the plutonium isotopes der ...

are created as a by-product of the nuclear energy industry. During the 1970s, the Japanese government made several appeals to the United States to use reprocessed plutonium in forming a "plutonium economy" for peaceful commercial use. This began a significant debate within the Carter administration about the risk of proliferation associated with reprocessing while also acknowledging Japan's need for energy and right to the use of peaceful nuclear technology. Ultimately, an agreement was reached that allowed Japan to repurpose the byproducts of nuclear power-related activities; however their efforts regarding fast-breeding plutonium reactors were largely unsuccessful.

In 2012 Japan was reported to have 9 tonnes of plutonium stored in Japan, which would be enough for more than 1,000 nuclear warheads, and an additional 35 tonnes stored in Europe. It has constructed the Rokkasho Reprocessing Plant

The is a nuclear reprocessing plant with an annual capacity of 800 tons of uranium or 8 tons of plutonium. It is owned by Japan Nuclear Fuel Limited (JNFL) and is part of the Rokkasho complex located in the village of Rokkasho in northeast Aomor ...

, which could produce further plutonium. Japan has a considerable quantity of highly enriched uranium

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (238U ...

(HEU), supplied by the U.S. and UK, for use in its research reactor

Research reactors are nuclear fission-based nuclear reactors that serve primarily as a neutron source. They are also called non-power reactors, in contrast to power reactors that are used for electricity production, heat generation, or marit ...

s and fast neutron reactor

A fast-neutron reactor (FNR) or fast-spectrum reactor or simply a fast reactor is a category of nuclear reactor in which the fission chain reaction is sustained by fast neutrons (carrying energies above 1 MeV or greater, on average), as opposed ...

research programs; approximately 1,200 to 1,400 kg of HEU as of 2014. Japan also possesses an indigenous uranium enrichment

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (238 ...

plant which could hypothetically be used to make highly enriched uranium suitable for weapons use.

Japan has also developed the M-V three-stage solid-fuel rocket

A solid-propellant rocket or solid rocket is a rocket with a rocket engine that uses solid propellants (fuel/oxidizer). The earliest rockets were solid-fuel rockets powered by gunpowder; they were used in warfare by the Arabs, Chinese, Persia ...

, somewhat similar in design to the U.S. LGM-118A Peacekeeper

The LGM-118 Peacekeeper, originally known as the MX for "Missile, Experimental", was a MIRV-capable intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) produced and deployed by the United States from 1985 to 2005. The missile could carry up to twelve M ...

ICBM

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more thermonuclear warheads). Conventional, chemical, and biological weapons ...

, giving it a missile technology base. It now has an easier-to-launch second generation solid-fuel rocket, Epsilon

Epsilon (, ; uppercase , lowercase or lunate ; el, ╬ŁŽł╬╣╬╗╬┐╬Į) is the fifth letter of the Greek alphabet, corresponding phonetically to a mid front unrounded vowel or . In the system of Greek numerals it also has the value five. It was d ...

. Japan has experience in re-entry vehicle technology ( OREX, HOPE-X

HOPE (H-II Orbiting Plane) was a Japanese experimental spaceplane project designed by a partnership between NASDA and NAL (both now part of JAXA), started in the 1980s. It was positioned for most of its lifetime as one of the main Japanese contri ...

). Toshiyuki Shikata, a Tokyo Metropolitan Government

The is the government of the Tokyo Metropolis. One of the 56 prefectures of Japan, the government consists of a popularly elected governor and assembly. The headquarters building is located in the ward of Shinjuku. The metropolitan governme ...

adviser and former lieutenant general, said that part of the rationale for the fifth M-V Hayabusa

was a robotic spacecraft developed by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) to return a sample of material from a small near-Earth asteroid named 25143 Itokawa to Earth for further analysis.

''Hayabusa'', formerly known as MUSES-C fo ...

mission, from 2003 to 2010, was that the re-entry and landing of its return capsule demonstrated "that Japan's ballistic missile capability is credible." A Japanese nuclear deterrent

Nuclear strategy involves the development of doctrines and strategies for the production and use of nuclear weapons.

As a sub-branch of military strategy, nuclear strategy attempts to match nuclear weapons as means to political ends. In addit ...

would probably be sea-based with ballistic missile submarine

A ballistic missile submarine is a submarine capable of deploying submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) with nuclear warheads. The United States Navy's hull classification symbols for ballistic missile submarines are SSB and SSBN Ō ...

s. In 2011, former Minister of Defense Shigeru Ishiba

is a Japanese politician. Ishiba is a member of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), and is the leader of the ''Suigetsukai'' party faction, and a member of the ''Heisei Kenkyūkai'' faction, which was then led by Fukushiro Nukaga, until 2011 ...

explicitly backed the idea of Japan maintaining the capability of nuclear latency:

On 24 March 2014, Japan agreed to turn over more than of weapons grade plutonium and highly enriched uranium to the US, which started to be returned in 2016. It has been pointed out that as long as Japan enjoys the benefits of a "nuclear-ready" status held through surrounding countries, it will see no reason to actually produce nuclear arms, since by remaining below the threshold, although with the capability to cross it at short notice, Japan can expect the support of the US while posing as an equal to China and Russia.

Former Mayor and Governor of Osaka T┼Źru Hashimoto

is a Japanese TV personality, politician and lawyer. He was the mayor of Osaka city and is a member of Nippon Ishin no Kai and the Osaka Restoration Association. He is one of Japan's leading right-wing conservative-populist politicians.

Early ...

in 2008 argued on several television programs that Japan should possess nuclear weapons, but has since said that this was his private opinion.

Former Governor of Tokyo 1999-2012, Shintaro Ishihara

was a Japanese politician and writer who was Governor of Tokyo from 1999 to 2012. Being the former leader of the radical right Japan Restoration Party, he was one of the most prominent ultranationalists in modern Japanese politics. An ultra ...

was a advocate of Japan having nuclear weapons.

On 29 March 2016, then-U.S. presidential candidate Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of P ...

suggested that Japan should develop its own nuclear weapons, claiming that it was becoming too expensive for the US to continue to protect Japan from countries such as China, North Korea, and Russia that already have their own nuclear weapons.

On 27 February 2022, former prime minister Shinzo Abe

Shinzo Abe ( ; ja, Õ«ēÕĆŹ µÖŗõĖē, Hepburn: , ; 21 September 1954 ŌĆō 8 July 2022) was a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan and President of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) from 2006 to 2007 and again from 2012 to 20 ...

proposed that Japan should consider a nuclear sharing

Nuclear sharing is a concept in NATO's policy of nuclear deterrence, which allows member countries without nuclear weapons of their own to participate in the planning for the use of nuclear weapons by NATO. In particular, it provides for the ar ...

arrangement with the US similar to NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du trait├® de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states ŌĆō 28 European and two N ...

. This includes housing American nuclear weapons on Japanese soil for deterrence. This plan comes in the wake of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

On 24 February 2022, in a major escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War, which began in 2014. The invasion has resulted in tens of thousands of deaths on both sides. It has caused Europe's largest refugee crisis since World War II. A ...

. Many Japanese politicians consider Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin; (born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician and former intelligence officer who holds the office of president of Russia. Putin has served continuously as president or prime minister since 1999: as prime min ...

's threat to use nuclear weapons against a non-nuclear state to be a game changer.

Although an indigenous nuclear program in Japan is unlikely to develop due to low public support, the existential Chinese and North Korean threats have raised security concerns domestically. The role of public opinion is central, and studies show that threat perceptions ŌĆō mainly of ChinaŌĆÖs growing military abilities ŌĆō have strengthened Japanese public support for a nuclear program. Japan has long held negative views on nuclear weapons, and previously, even discussions of nuclear armament or deterrence in the country was unpopular due to a strong "nuclear taboo". However, this taboo has been breaking, especially because Abe elevated the topic to mainstream politics during his tenure.

National identity is an important factor in Japanese nuclear armament. Since World War II, the peace constitution has greatly limited the ability of Japanese military advancement, restricting them from having an active military or waging war with another country. These restrictions and the strong desire of former colonies ŌĆō especially Korea and China ŌĆō for apology and reconciliation by Japan for its crimes and atrocities committed under pre-WWII imperialism, coupled with Japan's refusal to make appropriate amends, led to the rise of a conservative branch of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) in Japan that encouraged revisions to the Peace Constitution and promoted, under former prime minister Shinzo Abe, ŌĆ£healthy nationalism,ŌĆØ which aimed to restore the Japanese publicŌĆÖs sense of pride in the country. The revisionists sought to "create a new national identity" that increased national pride, allowed for collective self-defense and removed ŌĆ£institutional limitations on military activitiesŌĆØ.

Since the reliability of U.S. security guarantees shapes JapanŌĆÖs nuclear policy, a strong American nuclear umbrella is necessary to prevent Japan from developing nuclear weapons of its own. Since the 1960s, however, Japanese confidence in U.S. security guarantees has been influenced by American foreign policy shifts, from NixonŌĆÖs ŌĆ£Guam DoctrineŌĆØ to TrumpŌĆÖs desire for allies to provide more of their own security. Although Japan developing nuclear weapons would violate the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and potentially decrease U.S. power in East Asia, there is historical precedent for the U.S. to be complacent Japan building nuclear arms: as long as Japan is a democracy, a friend of Washington and has high state capacity, the U.S. alliance would likely be maintained. This was the case for France and the United Kingdom, when they developed their own nuclear weapons after the end of the Cold War despite American deterrence.

See also

*History of nuclear weapons

Nuclear weapons possess enormous destructive power from nuclear fission or combined fission and fusion reactions. Building on scientific breakthroughs made during the 1930s, the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and free France collabora ...

*Japan and weapons of mass destruction

Beginning in the mid-1930s, Japan conducted numerous attempts to acquire and develop weapons of mass destruction. The 1943 Battle of Changde saw Japanese use of both bioweapons and chemical weapons, and the Japanese conducted a serious, though ...

* Japan's non-nuclear weapons policy

* German nuclear weapons program

* Nuclear latency

References

Further reading

* Grunden, Walter E., ''Secret Weapons & World War II: Japan in the Shadow of Big Science'' (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2005). *Fintan Hoey. 2021. ŌĆ£ The ŌĆśConceit of ControllabilityŌĆÖ: Nuclear Diplomacy, JapanŌĆÖs Plutonium Reprocessing Ambitions and US Proliferation Fears, 1974-1978.ŌĆØ ''History and Technology'' 37(1): 44-66. *Ito, Kenji. 2021. " Three tons of uranium from the International Atomic Energy Agency: diplomacy over nuclear fuel for the Japan Research Reactor-3 at the Board of Governors' meetings, 1958ŌĆō1959". ''History and Technology'' 37(1): 67ŌĆō89. *Rhodes, Richard, ''The Making of the Atomic Bomb'' (New York, Simon and Schuster, 1986). * An article about uranium mining during World War II.External links

Annotated bibliography of Japanese atomic bomb program from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues.

Ćö

Federation of American Scientists

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) is an American nonprofit global policy think tank with the stated intent of using science and scientific analysis to attempt to make the world more secure. FAS was founded in 1946 by scientists who w ...

Japan's atomic bomb

History Channel International documentary

Japanese Nuclear Weapons Program during the WWII

published by the

National Security Archive

The National Security Archive is a 501(c)(3) non-governmental, non-profit research and archival institution located on the campus of the George Washington University in Washington, D.C. Founded in 1985 to check rising government secrecy. The N ...

{{JapanEmpireNavbox

Nuclear weapons programs

Nuclear history of Japan

Military history of Japan during World War II

Military history of Japan

Nuclear technology in Japan