James Naismith on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

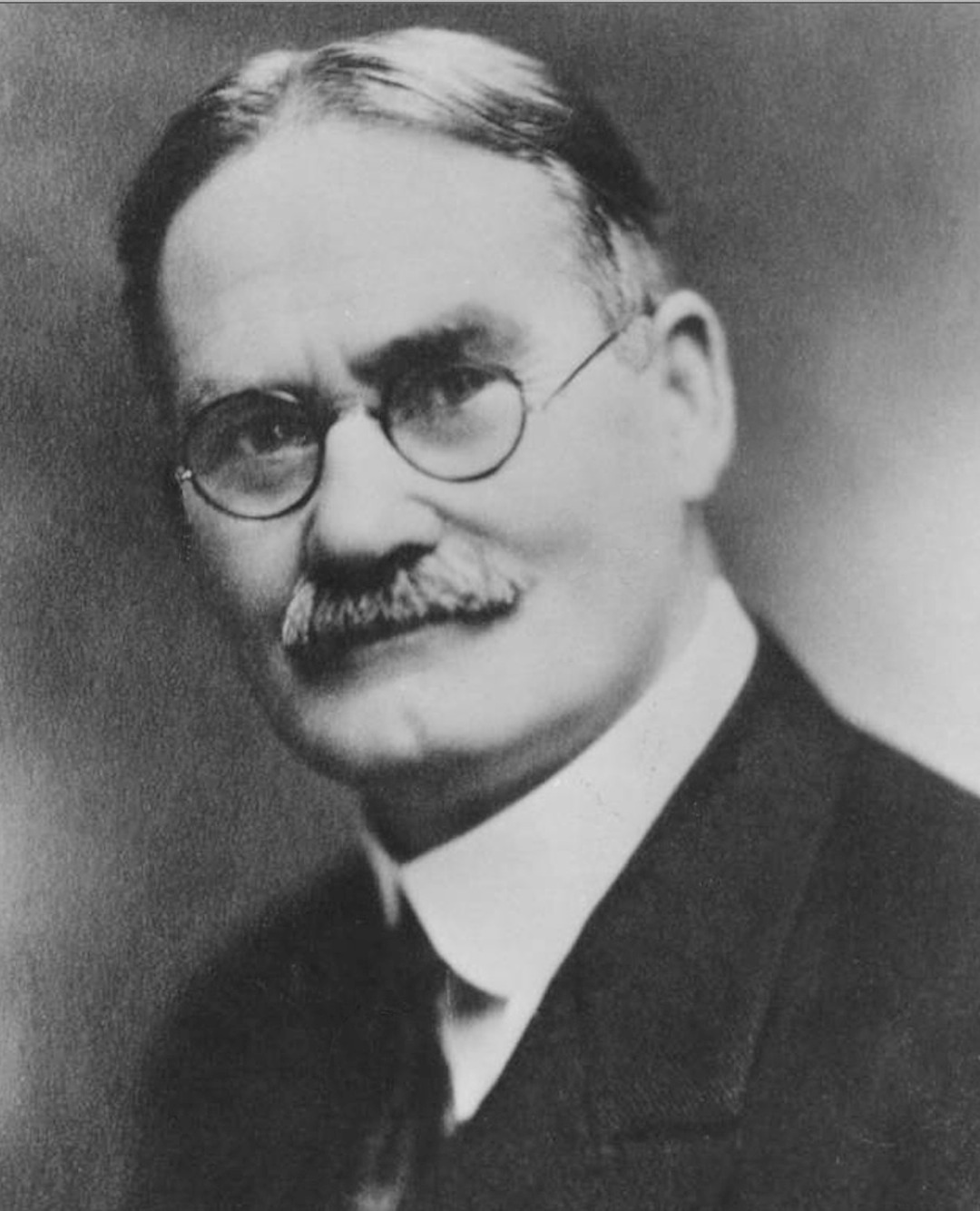

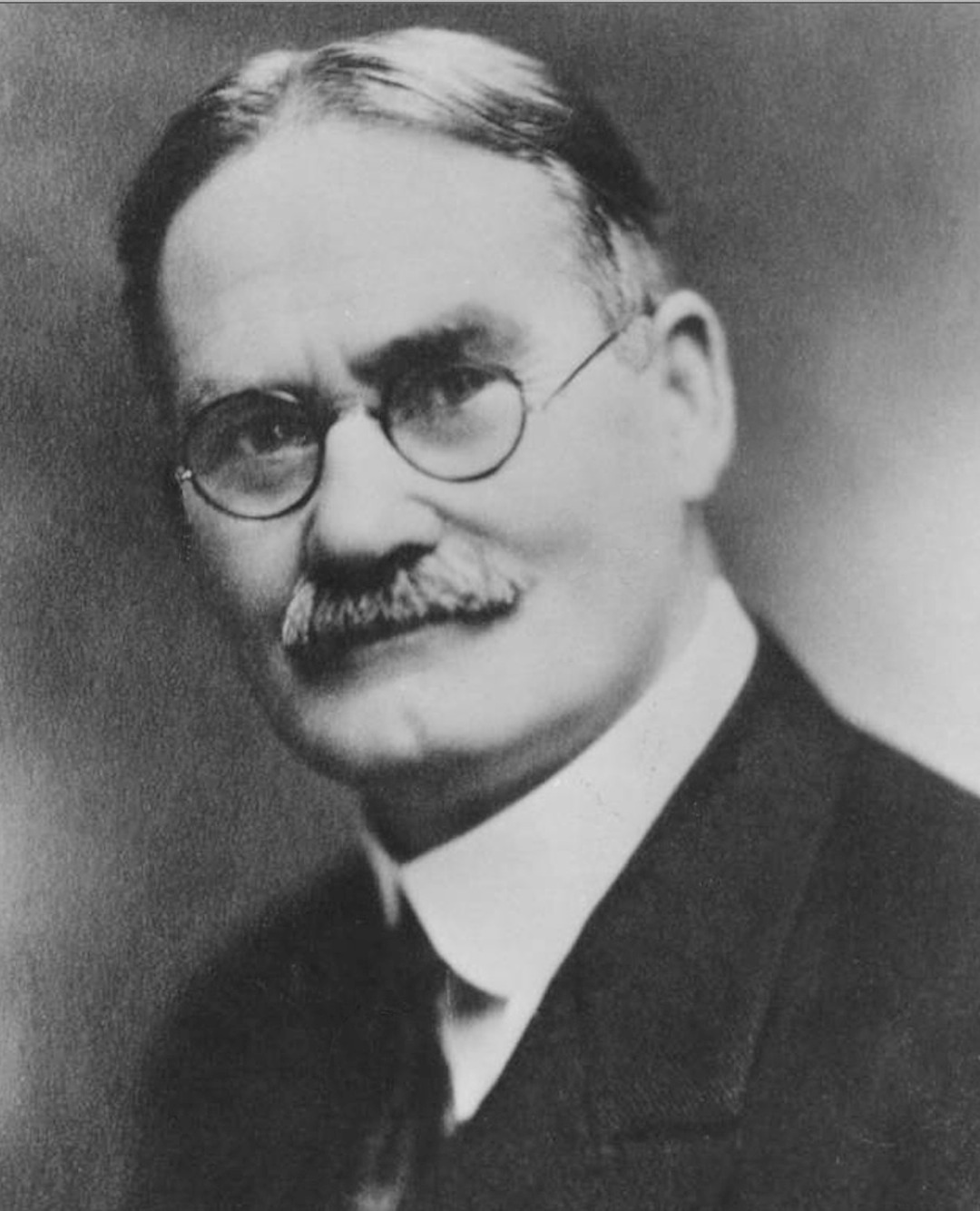

James Naismith (; November 6, 1861November 28, 1939) was a Canadian-American physical educator, physician, Christian

Naismith was born on November 6, 1861, in Almonte,

Naismith was born on November 6, 1861, in Almonte,

After completing the

After completing the

In 1898, Naismith became the first basketball coach of

In 1898, Naismith became the first basketball coach of

Naismith invented the game of basketball and wrote the original 13 rules of this sport; for comparison, the NBA rule book today features 66 pages. The

Naismith invented the game of basketball and wrote the original 13 rules of this sport; for comparison, the NBA rule book today features 66 pages. The  The original rules of basketball written by James Naismith in 1891, considered to be basketball's founding document, was auctioned at Sotheby's, New York, in December 2010. Josh Swade, a University of Kansas alumnus and basketball enthusiast, went on a crusade in 2010 to persuade moneyed alumni to consider bidding on and hopefully winning the document at auction to give it to the University of Kansas. Swade eventually persuaded

The original rules of basketball written by James Naismith in 1891, considered to be basketball's founding document, was auctioned at Sotheby's, New York, in December 2010. Josh Swade, a University of Kansas alumnus and basketball enthusiast, went on a crusade in 2010 to persuade moneyed alumni to consider bidding on and hopefully winning the document at auction to give it to the University of Kansas. Swade eventually persuaded

Amos Alonzo Stagg, College Football's Greatest Pioneer

'. Jefferson, NC: McFarland Books, 2021.

James Naismith

at

chaplain

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a Minister (Christianity), minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a laity, lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secularity, secular institution (such as a hosp ...

, and sports coach, best known as the inventor of the game of basketball

Basketball is a team sport in which two teams, most commonly of five players each, opposing one another on a rectangular Basketball court, court, compete with the primary objective of #Shooting, shooting a basketball (ball), basketball (appr ...

. After moving to the United States, he wrote the original basketball rule book and founded the University of Kansas

The University of Kansas (KU) is a public research university with its main campus in Lawrence, Kansas, United States, and several satellite campuses, research and educational centers, medical centers, and classes across the state of Kansas. Tw ...

basketball program. Naismith lived to see basketball adopted as an Olympic demonstration sport in 1904

Events

January

* January 7 – The distress signal ''CQD'' is established, only to be replaced 2 years later by ''SOS''.

* January 8 – The Blackstone Library is dedicated, marking the beginning of the Chicago Public Library system.

* ...

and as an official event at the 1936 Summer Olympics

The 1936 Summer Olympics (German: ''Olympische Sommerspiele 1936''), officially known as the Games of the XI Olympiad (German: ''Spiele der XI. Olympiade'') and commonly known as Berlin 1936 or the Nazi Olympics, were an international multi-sp ...

in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

, as well as the birth of the National Invitation Tournament

The National Invitational Tournament (NIT) is a men's college basketball tournament operated by the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA). Played at regional sites and traditionally at Madison Square Garden (Final Four) in New York City ...

(1938) and the NCAA Tournament (1939).

Born and raised on a farm near Almonte, Ontario

Almonte ( ; ) is a former mill town in Lanark County, in the eastern portion of Ontario, Canada. Formerly a separate municipality, Almonte is a ward of the town of Mississippi Mills, which was created on January 1, 1998, by the merging of Almont ...

, Naismith studied and taught physical education

Physical education, often abbreviated to Phys Ed. or P.E., is a subject taught in schools around the world. It is usually taught during primary and secondary education, and encourages psychomotor learning by using a play and movement explorati ...

at McGill University

McGill University (french: link=no, Université McGill) is an English-language public research university located in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Founded in 1821 by royal charter granted by King George IV,Frost, Stanley Brice. ''McGill Universit ...

in Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

until 1890 before moving to Springfield, Massachusetts

Springfield is a city in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, United States, and the seat of Hampden County. Springfield sits on the eastern bank of the Connecticut River near its confluence with three rivers: the western Westfield River, the ...

, United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

later that year, where in 1891 he designed the game of basketball while he was teaching at the International YMCA Training School. Seven years after inventing basketball, Naismith received his medical degree

A medical degree is a professional degree admitted to those who have passed coursework in the fields of medicine and/or surgery from an accredited medical school. Obtaining a degree in medicine allows for the recipient to continue on into special ...

in Denver

Denver () is a consolidated city and county, the capital, and most populous city of the U.S. state of Colorado. Its population was 715,522 at the 2020 census, a 19.22% increase since 2010. It is the 19th-most populous city in the Unit ...

in 1898. He then arrived at the University of Kansas

The University of Kansas (KU) is a public research university with its main campus in Lawrence, Kansas, United States, and several satellite campuses, research and educational centers, medical centers, and classes across the state of Kansas. Tw ...

, later becoming the Kansas Jayhawks

The Kansas Jayhawks, commonly referred to as simply KU or Kansas, are the athletic teams that represent the University of Kansas. KU is one of three schools in the state of Kansas that participate in NCAA Division I. The Jayhawks are also a mem ...

' athletic director and coach. While a coach at Kansas, Naismith coached Phog Allen

Forrest Clare "Phog" Allen (November 18, 1885 – September 16, 1974) was an American basketball coach. Known as the "Father of Basketball Coaching,"coaching tree

A coaching tree is similar to a family tree except it shows the relationships of coaches instead of family members. There are several ways to define a relationship between two coaches. The most common way to make the distinction is if a coach work ...

. Allen then went on to coach legends including Adolph Rupp

Adolph Frederick Rupp (September 2, 1901 – December 10, 1977) was an American college basketball coach. He is ranked seventh in total victories by a men's NCAA Division I college coach, winning 876 games in 41 years of coaching at the Univ ...

and Dean Smith

Dean Edwards Smith (February 28, 1931 – February 7, 2015) was an American men's college basketball head coach. Called a "coaching legend" by the Basketball Hall of Fame, he coached for 36 years at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hi ...

, among others, who themselves coached many notable players and future coaches.

Early years

Naismith was born on November 6, 1861, in Almonte,

Naismith was born on November 6, 1861, in Almonte, Province of Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central Cana ...

(now part of Mississippi Mills, Ontario

Mississippi Mills is a town in eastern Ontario, Canada, in Lanark County on the Mississippi River. It is made up of the former Townships of Ramsay and Pakenham, as well as the Town of Almonte. It is partly located within Canada's National Capital ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

) to Scottish parents.

He never had a middle name and never signed his name with an "A" initial. The "A" was added by someone in administration at the University of Kansas. Gifted in farm labor, Naismith spent his days outside playing catch, hide-and-seek, or duck on a rock

Duck on a rock is a medieval children’s game that combines tag and marksmanship (via throwing accuracy). James Naismith used the game as an inspiration when he developed the rules of modern basketball.

Gameplay

"Duck on a rock" is played by p ...

, a medieval game in which a person guards a large drake stone from opposing players, who try to knock it down by throwing smaller stones at it. To play duck on a rock most effectively, Naismith soon found that a soft lobbing shot was far more effective than a straight hard throw, a thought that later proved essential for the invention of basketball.

Orphaned early in his life, Naismith lived with his aunt and uncle for many years and attended grade school at Bennies Corners near Almonte. Then, he enrolled in Almonte High School, in Almonte, Ontario, from which he graduated in 1883.

In the same year, Naismith entered McGill University

McGill University (french: link=no, Université McGill) is an English-language public research university located in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Founded in 1821 by royal charter granted by King George IV,Frost, Stanley Brice. ''McGill Universit ...

in Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

. Although described as a slight figure, standing and listed at

he was a talented and versatile athlete, representing McGill in football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kicking a ball to score a goal. Unqualified, the word ''football'' normally means the form of football that is the most popular where the word is used. Sports commonly c ...

, lacrosse

Lacrosse is a team sport played with a lacrosse stick and a lacrosse ball. It is the oldest organized sport in North America, with its origins with the indigenous people of North America as early as the 12th century. The game was extensively ...

, rugby

Rugby may refer to:

Sport

* Rugby football in many forms:

** Rugby league: 13 players per side

*** Masters Rugby League

*** Mod league

*** Rugby league nines

*** Rugby league sevens

*** Touch (sport)

*** Wheelchair rugby league

** Rugby union: 1 ...

, soccer

Association football, more commonly known as football or soccer, is a team sport played between two teams of 11 players who primarily use their feet to propel the ball around a rectangular field called a pitch. The objective of the game is ...

, and gymnastics

Gymnastics is a type of sport that includes physical exercises requiring balance, strength, flexibility, agility, coordination, dedication and endurance. The movements involved in gymnastics contribute to the development of the arms, legs, shou ...

. He played centre on the football team, and made himself some padding to protect his ears. It was for personal use, not team use. He won multiple Wicksteed medals for outstanding gymnastics performances. Naismith earned a BA in physical education (1888) and a diploma at the Presbyterian College in Montreal (1890). From 1888 to 1890, Naismith taught physical education and became the first McGill director of athletics, but then left Montreal to study at the YMCA International Training School in Springfield, Massachusetts

Springfield is a city in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, United States, and the seat of Hampden County. Springfield sits on the eastern bank of the Connecticut River near its confluence with three rivers: the western Westfield River, the ...

. Naismith played football during his one year as a student at Springfield, where he was coached by Amos Alonzo Stagg

Amos Alonzo Stagg (August 16, 1862 – March 17, 1965) was an American athlete and college coach in multiple sports, primarily American football. He served as the head football coach at the International YMCA Training School (now called Springfie ...

and scored a touchdown in the first exhibition of indoor college football at Madison Square Garden

Madison Square Garden, colloquially known as The Garden or by its initials MSG, is a multi-purpose indoor arena in New York City. It is located in Midtown Manhattan between Seventh and Eighth avenues from 31st to 33rd Street, above Pennsylva ...

.

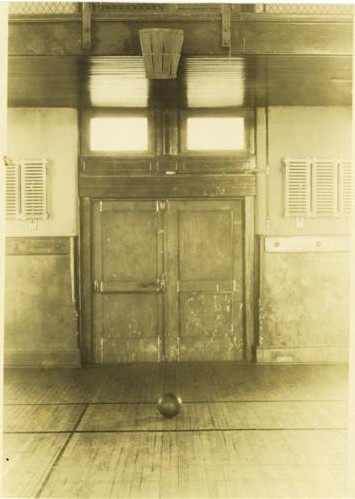

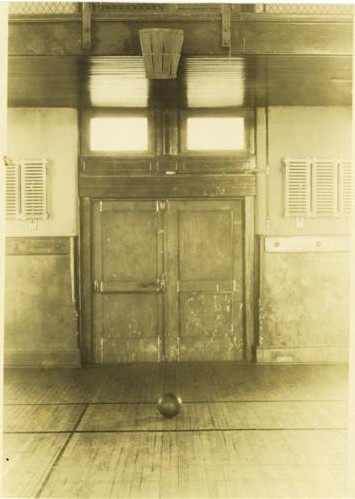

Springfield College: invention of basketball

After completing the

After completing the YMCA

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It was founded on 6 June 1844 by George Williams in London, originally ...

Physical Director training program that had brought him to Springfield, Naismith was hired as a full-time faculty member in 1891. At the Springfield YMCA, Naismith struggled with a rowdy class that was confined to indoor games throughout the harsh New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

winter, thus was perpetually short-tempered. Under orders from Dr. Luther Gulick, head of physical education there, Naismith was given 14 days to create an indoor game that would provide an "athletic distraction"; Gulick demanded that it would not take up much room, could help its track athletes to keep in shape and explicitly emphasized to "make it fair for all players and not too rough".

In his attempt to think up a new game, Naismith was guided by three main thoughts. Firstly, he analyzed the most popular games of those times (rugby, lacrosse, soccer

Association football, more commonly known as football or soccer, is a team sport played between two teams of 11 players who primarily use their feet to propel the ball around a rectangular field called a pitch. The objective of the game is ...

, football, hockey

Hockey is a term used to denote a family of various types of both summer and winter team sports which originated on either an outdoor field, sheet of ice, or dry floor such as in a gymnasium. While these sports vary in specific rules, numbers o ...

, and baseball

Baseball is a bat-and-ball sport played between two teams of nine players each, taking turns batting and fielding. The game occurs over the course of several plays, with each play generally beginning when a player on the fielding tea ...

); Naismith noticed the hazards of a ball and concluded that the big, soft soccer ball was safest. Secondly, he saw that most physical contacts occurred while running with the ball, dribbling, or hitting it, so he decided that passing was the only legal option. Finally, Naismith further reduced body contact by making the goal unguardable by placing it high above the player's heads with the plane of the goal's opening parallel to the floor. This placement forced the players to score goals by throwing a soft, lobbing shot like that which had proven effective in his old favorite game duck on a rock

Duck on a rock is a medieval children’s game that combines tag and marksmanship (via throwing accuracy). James Naismith used the game as an inspiration when he developed the rules of modern basketball.

Gameplay

"Duck on a rock" is played by p ...

. For this purpose, Naismith asked a janitor to find a pair of boxes, but the janitor brought him peach baskets instead. Naismith christened this new game "Basket Ball" and put his thoughts together in 13 basic rules.

The first game of "Basket Ball" was played in December 1891. In a handwritten report, Naismith described the circumstances of the inaugural match; in contrast to modern basketball, the players played nine versus nine, handled a soccer ball, not a basketball, and instead of shooting at two hoops, the goals were a pair of peach baskets: "When Mr. Stubbins brot up the peach baskets to the gym I secured them on the inside of the railing of the gallery. This was about 10 feet metersfrom the floor, one at each end of the gymnasium. I then put the 13 rules on the bulletin board just behind the instructor's platform, secured a soccer ball, and awaited the arrival of the class ... The class did not show much enthusiasm, but followed my lead ... I then explained what they had to do to make goals, tossed the ball up between the two center men and tried to keep them somewhat near the rules. Most of the fouls were called for running with the ball, though tackling the man with the ball was not uncommon." In contrast to modern basketball, the original rules did not include what is known today as the dribble

In sports, dribbling is maneuvering a ball by one player while moving in a given direction, avoiding defenders' attempts to intercept the ball. A successful dribble will bring the ball past defenders legally and create opportunities to score.

A ...

. Since the ball could only be moved up the court by a pass early players tossed the ball over their heads as they ran up court. Also following each "goal", a jump ball was taken in the middle of the court. Both practices are obsolete in the rules of modern basketball.

In a radio interview in January 1939, Naismith gave more details of the first game and the initial rules that were used:

I showed them two peach baskets I'd nailed up at each end of the gym, and I told them the idea was to throw the ball into the opposing team's peach basket. I blew a whistle, and the first game of basketball began. ... The boys began tackling, kicking, and punching in the clinches. They ended up in a free-for-all in the middle of the gym floor. he injury toll: several black eyes, one separated shoulder, and one player knocked unconscious."It certainly was murder." aismith changed some of the rules as part of his quest to develop a clean sport.The most important one was that there should be no running with the ball. That stopped tackling and slugging. We tried out the game with those ewrules (fouls), and we didn't have one casualty.Naismith was a classmate of

Amos Alonzo Stagg

Amos Alonzo Stagg (August 16, 1862 – March 17, 1965) was an American athlete and college coach in multiple sports, primarily American football. He served as the head football coach at the International YMCA Training School (now called Springfie ...

at the YMCA School, where Stagg coached the football team. They became close friends and Naismith played on the football team and Stagg played on the basketball team. Naismith invited Stagg to play in the first public basketball game on March 12, 1892. The students defeated the faculty 5–1 and Stagg scored the only basket for the faculty. The Springfield Republican reported on the same: "Over 200 spectators crammed their necks over the gallery railing of the Christian Workers gymnasium while they watched the game of 'basket ball' between the teachers and the students. The most conspicuous figure on the floor was Stagg in the blue Yale uniform who managed to have a hand in every scrimmage."

By 1892, basketball had grown so popular on campus that Dennis Horkenbach (editor-in-chief of ''The Triangle'', the Springfield college newspaper) featured it in an article called "A New Game", and there were calls to call this new game "Naismith Ball", but Naismith refused. By 1893, basketball was introduced internationally by the YMCA

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It was founded on 6 June 1844 by George Williams in London, originally ...

movement. From Springfield, Naismith went to Denver, where he acquired a medical degree, and in 1898, he joined the University of Kansas

The University of Kansas (KU) is a public research university with its main campus in Lawrence, Kansas, United States, and several satellite campuses, research and educational centers, medical centers, and classes across the state of Kansas. Tw ...

faculty at Lawrence

Lawrence may refer to:

Education Colleges and universities

* Lawrence Technological University, a university in Southfield, Michigan, United States

* Lawrence University, a liberal arts university in Appleton, Wisconsin, United States

Preparator ...

.

The family of Lambert G. Will, disputing Naismith's sole creation of the game, has claimed that Naismith borrowed components for the game of basketball from Will, citing alleged photos and letters. In an interview, the family did give Naismith credit for the general idea of the sport, but they claimed Will changed aspects of Naismith's original plans for the game and Naismith took credit for the changes.

Spalding worked with Naismith to develop the official basketball and the Spalding Athletic Library official basketball rule book for 1893–1894.

University of Kansas

TheUniversity of Kansas

The University of Kansas (KU) is a public research university with its main campus in Lawrence, Kansas, United States, and several satellite campuses, research and educational centers, medical centers, and classes across the state of Kansas. Tw ...

men's basketball program officially began following Naismith's arrival in 1898, seven years after Naismith drafted the sport's first official rules. Naismith was not initially hired to coach basketball, but rather as a chapel director and physical-education instructor. In those early days, the majority of the basketball games were played against nearby YMCA teams, with YMCAs across the nation having played an integral part in the birth of basketball. Other common opponents were Haskell Indian Nations University

Haskell Indian Nations University is a public tribal land-grant university in Lawrence, Kansas, United States. Founded in 1884 as a residential boarding school for American Indian children, the school has developed into a university operated by t ...

and William Jewell College

William Jewell College is a private liberal arts college in Liberty, Missouri. It was founded in 1849 by members of the Missouri Baptist Convention and endowed with $10,000 by William Jewell. It was associated with the Missouri Baptist Conventi ...

. Under Naismith, the team played only one current Big 12

The Big 12 Conference is a college athletic conference headquartered in Irving, Texas, USA. It consists of ten full-member universities. It is a member of Division I of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) for all sports. Its fo ...

school: Kansas State

Kansas State University (KSU, Kansas State, or K-State) is a public land-grant research university with its main campus in Manhattan, Kansas, United States. It was opened as the state's land-grant college in 1863 and was the first public instit ...

(once). Naismith is, ironically, the only coach in the program's history to have a losing record (55–60). However, Naismith coached Forrest "Phog" Allen, his eventual successor at Kansas, who went on to join his mentor in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame

The Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame is an American history museum and hall of fame, located at 1000 Hall of Fame Avenue in Springfield, Massachusetts. It serves as basketball's most complete library, in addition to promoting and pres ...

. When Allen became a coach himself and told him that he was going to coach basketball at Baker University

Baker University is a private university in Baldwin City, Kansas. Founded in 1858, it was the first four-year university in Kansas and is affiliated with the United Methodist Church. Baker University is made up of four schools. The College of Art ...

in 1904, Naismith discouraged him: "You can't coach basketball; you just play it." Instead, Allen embarked on a coaching career that would lead him to be known as "the Father of Basketball Coaching". During his time at Kansas, Allen coached Dean Smith

Dean Edwards Smith (February 28, 1931 – February 7, 2015) was an American men's college basketball head coach. Called a "coaching legend" by the Basketball Hall of Fame, he coached for 36 years at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hi ...

(1952 National Championship team) and Adolph Rupp

Adolph Frederick Rupp (September 2, 1901 – December 10, 1977) was an American college basketball coach. He is ranked seventh in total victories by a men's NCAA Division I college coach, winning 876 games in 41 years of coaching at the Univ ...

(1922 Helms Foundation National Championship team). Smith and Rupp have joined Naismith and Allen as members of the Basketball Hall of Fame.

By the turn of the century, enough college teams were in the East that the first intercollegiate competitions could be played out. Although the sport continued to grow, Naismith long regarded the game as a curiosity and preferred gymnastics and wrestling

Wrestling is a series of combat sports involving grappling-type techniques such as clinch fighting, throws and takedowns, joint locks, pins and other grappling holds. Wrestling techniques have been incorporated into martial arts, combat ...

as better forms of physical activity. However, basketball became a demonstration sport

A demonstration sport, or exhibition sport, is a sport which is played to promote it, rather than as part of standard medal competition. This occurs commonly during the Olympic Games, but may also occur at other sporting events.

Demonstration spor ...

at the 1904 Summer Olympics

The 1904 Summer Olympics (officially the Games of the III Olympiad and also known as St. Louis 1904) were an international multi-sport event held in St. Louis, Missouri, United States, from 29 August to 3 September 1904, as part of an extended s ...

in St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

. As the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame

The Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame is an American history museum and hall of fame, located at 1000 Hall of Fame Avenue in Springfield, Massachusetts. It serves as basketball's most complete library, in addition to promoting and pres ...

reports, Naismith was not interested in self-promotion nor was he interested in the glory of competitive sports. Instead, he was more interested in his physical-education career; he received an honorary PE master's degree in 1910, patrolled the Mexican border

Mexico shares international borders with three nations:

*To the north the United States–Mexico border, which extends for a length of through the states of Baja California, Sonora, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo León and Tamaulipas.

*To the south ...

for four months in 1916, traveled to France, and published two books (''A Modern College'' in 1911 and ''Essence of a Healthy Life'' in 1918). He took American citizenship on May 4, 1925. In 1909, Naismith's duties at Kansas were redefined as a professorship; he served as the ''de facto'' athletic director at Kansas for much of the early 20th century.

Naismith had "strong feelings against segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of humans ...

," dating back to his World War I-era service in France and his service on the United States-Mexico border, and he strove for progress in race relations through modest steps. During the 1930s, he would not or could not get African-Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ensl ...

onto Kansas' varsity Jayhawks, but he did help engineer the admission of black students to the university's swimming pool

A swimming pool, swimming bath, wading pool, paddling pool, or simply pool, is a structure designed to hold water to enable Human swimming, swimming or other leisure activities. Pools can be built into the ground (in-ground pools) or built ...

. Until then, they had been given automatic passing grades on a required swimming test without entering the pool, so it could remain all-white.

Through Naismith's association with Baker University Basketball Coach Emil Liston, he became familiar and impressed with Emil Liston's fraternity at Baker University, Sigma Phi Epsilon (SigEp). As a result, he started the effort to bring a Sigma Phi Epsilon chapter to his University of Kansas (KU). On February 18, 1923, Naismith, intending to bring a SigEp Chapter to KU, was initiated as a SigEp member by national office of the fraternity. Under Naismith's leadership, the University of Kansas Sigma Phi Epsilon Chapter was founded and officially Charted on April 28, 1923, with Dr. Naismith leading the new 40-member fraternity as "Chapter Counselor." Naismith was deeply involved with the members, serving as Chapter Counselor for 16 years, from 1923 until his death in 1939. During those 16 years as Chapter Counselor, he married SigEp's housemother, Mrs. Florence Kincaid. Members who were interviewed during that era remembered Dr. Naismith: "He was deeply religious", "He listened more than he spoke", "He thought sports were nothing but an avenue to keep young people involved so they could do their studies and relate to their community", and "It was really nice having someone with the caliber of Dr. Naismith, he helped many a SigEp"

In 1935, the National Association of Basketball Coaches

The National Association of Basketball Coaches (NABC), headquartered in Kansas City, Missouri, is an American organization of men's college basketball coaches. It was founded in 1927 by Phog Allen, head men's basketball coach at the University o ...

(founded by Naismith's pupil Phog Allen) collected money so the 74-year-old Naismith could witness the introduction of basketball into the official Olympic sports program of the 1936 Summer Olympic Games

The 1936 Summer Olympics (German: ''Olympische Sommerspiele 1936''), officially known as the Games of the XI Olympiad (German: ''Spiele der XI. Olympiade'') and commonly known as Berlin 1936 or the Nazi Olympics, were an international multi-sp ...

in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

. There, Naismith handed out the medals to three North American teams: the [United States, for the gold medal, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, for the silver medal, and Mexico, for their bronze medal. During the Olympics, he was named the honorary president of the International Basketball Federation. When Naismith returned, he commented that seeing the game played by many nations was the greatest compensation he could have received for his invention. In 1937, Naismith played a role in the formation of the National Association of Intercollegiate Basketball, which later became the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics

The National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) established in 1940, is a college athletics association for colleges and universities in North America. Most colleges and universities in the NAIA offer athletic scholarships to its stu ...

(NAIA).

Naismith became professor ''emeritus'' at Kansas when he retired in 1937 at the age of 76. In addition to his years as a coach, for a total of almost 40 years, Naismith worked at the school and during those years, he also served as its athletic director and was also a faculty member at the school. In 1939, Naismith suffered a fatal brain hemorrhage. He was interred at Memorial Park Cemetery in Lawrence, Kansas

Lawrence is the county seat of Douglas County, Kansas, Douglas County, Kansas, United States, and the sixth-largest city in the state. It is in the northeastern sector of the state, astride Interstate 70, between the Kansas River, Kansas and Waka ...

. His masterwork "Basketball — its Origins and Development" was published posthumously in 1941. In Lawrence, Naismith has a road named in his honor, Naismith Drive, which runs in front of Allen Fieldhouse and James Naismith Court therein are named in his honor, despite Naismith's having the worst record in school history. Naismith Hall, a dormitory, is located on the northeastern edge of 19th Street and Naismith Drive.

Head-coaching record

In 1898, Naismith became the first basketball coach of

In 1898, Naismith became the first basketball coach of University of Kansas

The University of Kansas (KU) is a public research university with its main campus in Lawrence, Kansas, United States, and several satellite campuses, research and educational centers, medical centers, and classes across the state of Kansas. Tw ...

. He compiled a record of 55–60 and is ironically the only losing coach in Kansas history. Naismith is at the beginning of a massive and prestigious coaching tree, as he coached Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame

The Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame is an American history museum and hall of fame, located at 1000 Hall of Fame Avenue in Springfield, Massachusetts. It serves as basketball's most complete library, in addition to promoting and pres ...

coach Phog Allen

Forrest Clare "Phog" Allen (November 18, 1885 – September 16, 1974) was an American basketball coach. Known as the "Father of Basketball Coaching,"Dean Smith

Dean Edwards Smith (February 28, 1931 – February 7, 2015) was an American men's college basketball head coach. Called a "coaching legend" by the Basketball Hall of Fame, he coached for 36 years at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hi ...

, Adolph Rupp

Adolph Frederick Rupp (September 2, 1901 – December 10, 1977) was an American college basketball coach. He is ranked seventh in total victories by a men's NCAA Division I college coach, winning 876 games in 41 years of coaching at the Univ ...

, and Ralph Miller

Ralph H. Miller (March 9, 1919 – May 15, 2001) was an American college basketball coach, a head coach for 38 years at three universities: Wichita (now known as Wichita State), Iowa, and Oregon State. With an overall record of , his teams had ...

who all coached future coaches as well. In addition to Allen, Naismith also can be seen as a mentor and therefore beginning for the coaching tree branches of John McLendon

John B. McLendon Jr. (April 5, 1915 – October 8, 1999) was an American basketball coach who is recognized as the first African American basketball coach at a predominantly white university and the first African American head coach in any professi ...

who wasn't permitted to play at Kansas but was close to Naismith during his time as an athletic director. Amos Alonzo Stagg

Amos Alonzo Stagg (August 16, 1862 – March 17, 1965) was an American athlete and college coach in multiple sports, primarily American football. He served as the head football coach at the International YMCA Training School (now called Springfie ...

, was primarily a football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kicking a ball to score a goal. Unqualified, the word ''football'' normally means the form of football that is the most popular where the word is used. Sports commonly c ...

coach, but he did play basketball for Naismith in Springfield, coached a year of basketball at Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

and had several football players who also coached basketball such as Jesse Harper

Jesse Clair Harper (December 10, 1883 – July 31, 1961) was an American football and baseball player, coach, and college athletics administrator. He served as the head football coach at Alma College (1906–1907), Wabash College (1909–1912), an ...

, Fred Walker Frederick, Frederic, Friedrich or Fred Walker may refer to:

*Frederick Walker (native police commandant) (died 1866), explorer

* Frederick Walker (painter) (1840–1875), English painter and illustrator

*Frederic John Walker (1896–1944), ...

and Tony Hinkle

Paul D. "Tony" Hinkle (December 19, 1899 – September 22, 1992) was an American football, basketball, and baseball player, coach, and college athletic administrator. He attended the University of Chicago, where he won varsity letters in three spo ...

.

Legacy

Naismith invented the game of basketball and wrote the original 13 rules of this sport; for comparison, the NBA rule book today features 66 pages. The

Naismith invented the game of basketball and wrote the original 13 rules of this sport; for comparison, the NBA rule book today features 66 pages. The Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame

The Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame is an American history museum and hall of fame, located at 1000 Hall of Fame Avenue in Springfield, Massachusetts. It serves as basketball's most complete library, in addition to promoting and pres ...

in Springfield, Massachusetts, is named in his honor, and he was an inaugural inductee in 1959. The National Collegiate Athletic Association

The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) is a nonprofit organization that regulates student athletics among about 1,100 schools in the United States, Canada, and Puerto Rico. It also organizes the athletic programs of colleges an ...

rewards its best players and coaches annually with the Naismith Award Naismith Award is a basketball award named after James Naismith, and awarded by the Atlanta Tipoff Club.

Naismith Awards include:

* Naismith College Player of the Year (men's and women's; NCAA Division I basketball)

* Naismith College Coach of the ...

s, among them the Naismith College Player of the Year

The Naismith College Player of the Year is an annual basketball award given by the Atlanta Tipoff Club to the top men's and women's collegiate basketball players. It is named in honor of Dr. James Naismith, the inventor of basketball.

History an ...

, the Naismith College Coach of the Year

Naismith College Coach of the Year Award is an award given by the Atlanta Tipoff Club to one men's and one women's NCAA Division I collegiate coach each season since 1987. The award was originally given to the two winning coaches of the NCAA Divis ...

, and the Naismith Prep Player of the Year

The Naismith Prep Player of the Year award, named for Canadian basketball inventor James Naismith, is given annually by the Atlanta Tipoff Club to high school basketball's top male and female player. The inaugural awards were given to Dennis Sco ...

. After the Olympic introduction to men's basketball in 1936, women's basketball became an Olympic event in Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

during the 1976 Summer Olympics

Events January

* January 3 – The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights enters into force.

* January 5 – The Pol Pot regime proclaims a new constitution for Democratic Kampuchea.

* January 11 – The 1976 Phi ...

. Naismith was also inducted into the Canadian Basketball Hall of Fame, the Canadian Olympic Hall of Fame The Canadian Olympic Hall of Fame is an honour roll of the top Canadian Olympic athletes, teams, coaches, and builders (officials, administrators, and volunteers). It was established in 1949. Selections are made by a committee appointed by the Canad ...

, the Canadian Sports Hall of Fame

Canada's Sports Hall of Fame (french: Panthéon des sports canadiens; sometimes referred to as the Canadian Sports Hall of Fame) is a Canadian sports hall of fame and museum in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. Dedicated to the history of sports in Canada, ...

, the Ontario Sports Hall of Fame

The Ontario Sports Hall of Fame is an association dedicated to honouring athletes and personalities with outstanding achievement in sports in Ontario, Canada. The hall of fame was established in 1994 by Bruce Prentice, following his 15-year tenure ...

, the Ottawa Sports Hall of Fame, the McGill University Sports Hall of Fame, the Kansas State Sports Hall of Fame, FIBA Hall of Fame

The FIBA Hall of Fame, or FIBA Basketball Hall of Fame, honors players, coaches, teams, referees, and administrators who have greatly contributed to international competitive basketball. It was established by FIBA, in 1991. It includes the " Samar ...

. The FIBA Basketball World Cup

The FIBA Basketball World Cup, also known as the FIBA World Cup of Basketball or simply the FIBA World Cup, between 1950 and 2010 known as the FIBA World Championship, is an international basketball competition contested by the senior men's nat ...

trophy is named the "James Naismith Trophy" in his honor. On June 21, 2013, Dr. Naismith was inducted into the Kansas Hall of Fame during ceremonies in Topeka.

Naismith's home town of Almonte, Ontario

Almonte ( ; ) is a former mill town in Lanark County, in the eastern portion of Ontario, Canada. Formerly a separate municipality, Almonte is a ward of the town of Mississippi Mills, which was created on January 1, 1998, by the merging of Almont ...

, hosts an annual 3-on-3 tournament for all ages and skill levels in his honor. Every year, this event attracts hundreds of participants and involves over 20 half-court games along the main street of the town. All proceeds of the event go to youth basketball programs in the area.

Today basketball is played by more than 300 million people worldwide, making it one of the most popular team sports. In North America, basketball has produced some of the most-admired athletes of the 20th century. ESPN

ESPN (originally an initialism for Entertainment and Sports Programming Network) is an American international basic cable sports channel owned by ESPN Inc., owned jointly by The Walt Disney Company (80%) and Hearst Communications (20%). The ...

and the Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. newspa ...

both conducted polls to name the greatest North American athlete of the 20th century. Basketball player Michael Jordan

Michael Jeffrey Jordan (born February 17, 1963), also known by his initials MJ, is an American businessman and former professional basketball player. His biography on the official NBA website states: "By acclamation, Michael Jordan is the g ...

came in first in the ESPN poll and second (behind Babe Ruth

George Herman "Babe" Ruth Jr. (February 6, 1895 – August 16, 1948) was an American professional baseball player whose career in Major League Baseball (MLB) spanned 22 seasons, from 1914 through 1935. Nicknamed "the Bambino" and "the Su ...

) in the AP poll. Both polls featured fellow basketball players Wilt Chamberlain

Wilton Norman Chamberlain (; August 21, 1936 – October 12, 1999) was an American professional basketball player who played as a Center (basketball), center. Standing at tall, he played in the National Basketball Association (NBA) for 14 yea ...

(of KU, like Naismith) and Bill Russell

William Felton Russell (February 12, 1934 – July 31, 2022) was an American professional basketball player who played as a center for the Boston Celtics of the National Basketball Association (NBA) from 1956 to 1969. A five-time NBA Most V ...

in the top 20.

The original rules of basketball written by James Naismith in 1891, considered to be basketball's founding document, was auctioned at Sotheby's, New York, in December 2010. Josh Swade, a University of Kansas alumnus and basketball enthusiast, went on a crusade in 2010 to persuade moneyed alumni to consider bidding on and hopefully winning the document at auction to give it to the University of Kansas. Swade eventually persuaded

The original rules of basketball written by James Naismith in 1891, considered to be basketball's founding document, was auctioned at Sotheby's, New York, in December 2010. Josh Swade, a University of Kansas alumnus and basketball enthusiast, went on a crusade in 2010 to persuade moneyed alumni to consider bidding on and hopefully winning the document at auction to give it to the University of Kansas. Swade eventually persuaded David G. Booth

David Gilbert Booth (born 1946) is an American businessman, investor, and philanthropist. He is the executive chairman of Dimensional Fund Advisors, which he co-founded with Rex Sinquefield.

Career

Booth graduated from Lawrence High School in ...

, a billionaire investment banker and KU alumnus, and his wife Suzanne Booth, to commit to bidding at the auction. The Booths won the bidding and purchased the document for a record US$4,338,500, the most ever paid for a sports memorabilia item, and gave the document to the University of Kansas. Swade's project and eventual success are chronicled in a 2012 ESPN ''30 for 30

''30 for 30'' is the title for a series of documentary films airing on ESPN, its sister networks, and online highlighting interesting people and events in sports history. This includes three "volumes" of 30 episodes each, a 13-episode series un ...

'' documentary "There's No Place Like Home" and in a corresponding book, ''The Holy Grail of Hoops: One Fan's Quest to Buy the Original Rules of Basketball''. The University of Kansas constructed an $18 million building named the Debruce Center, which houses the rules and opened in March 2016.

Naismith was designated a National Historic Person in 1976, on the advice of the national Historic Sites and Monuments Board

In 1991, postage stamps commemorated the centennial of basketball's invention: four stamps were issued by Canada Post

Canada Post Corporation (french: Société canadienne des postes), trading as Canada Post (french: Postes Canada), is a Crown corporation that functions as the primary postal operator in Canada. Originally known as Royal Mail Canada (the opera ...

, including one with Naismith's name; one stamp was issued by the US Postal Service

The United States Postal Service (USPS), also known as the Post Office, U.S. Mail, or Postal Service, is an independent agency of the executive branch of the United States federal government responsible for providing postal service in the U ...

. Another Canadian stamp, in 2009, honored the game's invention.

In July 2019, Naismith was inducted into Toronto's Walk of Fame

A hall, wall, or walk of fame is a list of individuals, achievements, or other entities, usually chosen by a group of electors, to mark their excellence or fame in their field. In some cases, these halls of fame consist of actual halls or muse ...

.

On January 15, 2021, Google

Google LLC () is an American multinational technology company focusing on search engine technology, online advertising, cloud computing, computer software, quantum computing, e-commerce, artificial intelligence, and consumer electronics. ...

placed a Google Doodle

A Google Doodle is a special, temporary alteration of the logo on Google's homepages intended to commemorate holidays, events, achievements, and notable historical figures. The first Google Doodle honored the 1998 edition of the long-running an ...

celebrating James Naismith on its home page in 18 countries, on five continents.

Personal life

Naismith was the second child of Margaret and John Naismith, two Scottish immigrants. His mother, Margaret Young, the fourth of 11 children, was born in 1833 and immigrated toLanark County

Lanark County is a county located in the Canadian province of Ontario. Its county seat is Perth, which was first settled in 1816.Brown, Howard Morton, 1984. Lanark Legacy, Nineteenth Century Glimpses of on Ontario County. Corporation of the Cou ...

, Canada in 1852. His father, John Naismith, was born in 1833, left Europe when he was 18, and also settled down in Lanark County.

On June 20, 1894, Naismith married Maude Evelyn Sherman (1870–1937) in Springfield, Massachusetts. The couple had five children.

He was a member of the Pi Gamma Mu

Pi Gamma Mu or (from Πολιτικές Γνώσεως Μάθεται) is the oldest and preeminent honor society in the social sciences. It is also the only interdisciplinary social science honor society. It serves the various social science di ...

and Sigma Phi Epsilon

Sigma Phi Epsilon (), commonly known as SigEp, is a social college fraternity for male college students in the United States. It was founded on November 1, 1901, at Richmond College (now the University of Richmond), and its national headquarte ...

fraternities. Naismith was a Presbyterian minister and was also a Freemason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

.

Maude Naismith died in 1937, and on June 11, 1939, he married his second wife, Florence B. Kincaid. On November 19 of that year, Naismith suffered a major brain hemorrhage and died nine days later in his home in Lawrence. He was 78 years old. Naismith died eight months after the birth of the NCAA Basketball Championship, which today has evolved to one of the biggest sports events in North America. Naismith is buried with his first wife in Memorial Park Cemetery in Lawrence. Florence Kincaid died in 1977 at the age of 98 and is buried with her first husband, Dr. Frank B. Kincaid, in Elmwood Cemetery in Beloit, Kansas

Beloit is a city in and the county seat of Mitchell County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 3,404.

History

On permanent organization of the county in 1870, Beloit was selected as the county seat ...

.

During his lifetime, Naismith held these educational and academic positions:

See also

* James Naismith's Original Rules of BasketballNotes

References

Further reading

* **Reprinted: * *Sumner, David E.Amos Alonzo Stagg, College Football's Greatest Pioneer

'. Jefferson, NC: McFarland Books, 2021.

External links

*James Naismith

at

Find a Grave

Find a Grave is a website that allows the public to search and add to an online database of cemetery records. It is owned by Ancestry.com. Its stated mission is "to help people from all over the world work together to find, record and present fin ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Naismith, James

1861 births

1939 deaths

American Presbyterian ministers

American inventors

Basketball people from Ontario

British emigrants to the United States

Canadian Freemasons

Canadian Presbyterian ministers

Canadian emigrants to the United States

Canadian inventors

Canadian men's basketball coaches

Canadian people of Scottish descent

College men's basketball head coaches in the United States

Creators of sports

FIBA Hall of Fame inductees

History of basketball

Kansas Jayhawks athletic directors

Kansas Jayhawks men's basketball coaches

McGill University Faculty of Education alumni

McGill University faculty

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame inductees

People from Almonte, Ontario

Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada)

Springfield College (Massachusetts) alumni

University of Kansas faculty

YMCA leaders