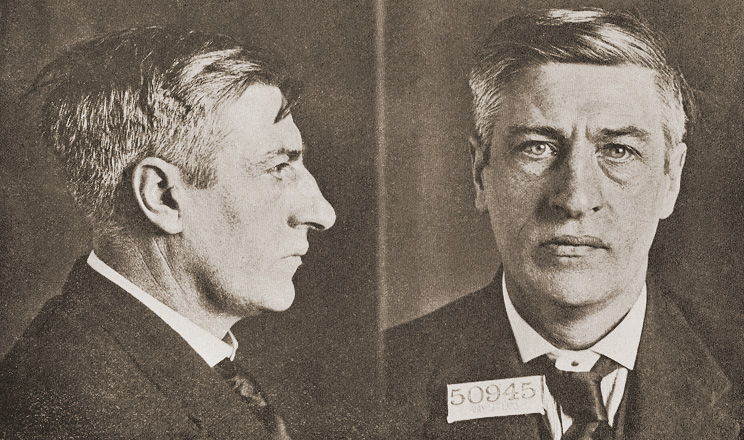

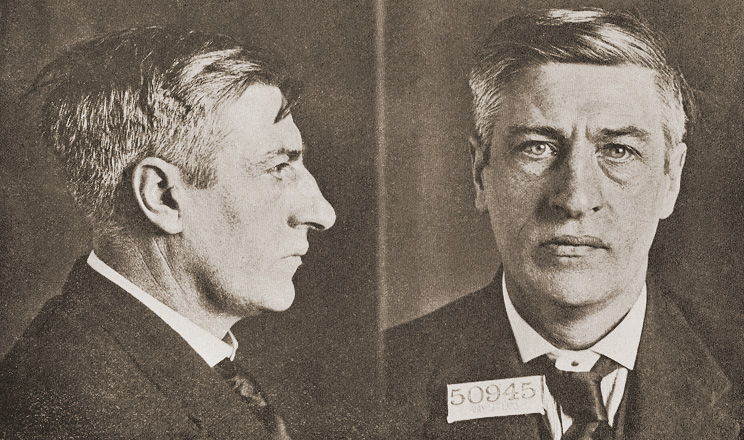

James Larkin (28 January 1874 – 30 January 1947), sometimes known as Jim Larkin or Big Jim, was an

Irish republican

Irish republicanism ( ga, poblachtánachas Éireannach) is the political movement for the unity and independence of Ireland under a republic. Irish republicans view British rule in any part of Ireland as inherently illegitimate.

The developm ...

,

socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

and trade union leader. He was one of the founders of the Irish

Labour Party along with

James Connolly

James Connolly ( ga, Séamas Ó Conghaile; 5 June 1868 – 12 May 1916) was an Irish republican, socialist and trade union leader. Born to Irish parents in the Cowgate area of Edinburgh, Scotland, Connolly left school for working life at the a ...

and

William O'Brien

William O'Brien (2 October 1852 – 25 February 1928) was an Irish nationalist, journalist, agrarian agitator, social revolutionary, politician, party leader, newspaper publisher, author and Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons ...

, and later the founder of the

Irish Worker League

The Irish Worker League was an Irish communist party, established in September 1923 by Jim Larkin, following his return to Ireland. Larkin re-established the newspaper '' The Irish Worker''. The Irish Worker League (IWL) superseded the first ...

(a communist party which was recognised by the

Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

as the Irish section of the world communist movement), as well as the

Irish Transport and General Workers' Union (ITGWU) and the

Workers' Union of Ireland

The Workers' Union of Ireland (WUI), later the Federated Workers' Union of Ireland, was an Irish trade union formed in 1924. In 1990, it merged with the Irish Transport and General Workers Union to form the Services, Industrial, Professional an ...

(the two unions later merged to become

SIPTU

SIPTU (; ''Services, Industrial, Professional and Technical Union''; ga, An Ceardchumann Seirbhísí, Tionsclaíoch, Gairmiúil agus Teicniúil) is Ireland's largest trade union, with around 200,000 members. Most of these members are in the Rep ...

, Ireland's largest trade union). Along with Connolly and

Jack White

John Anthony White (; born July 9, 1975), commonly known as Jack White, is an American musician, best known as the lead singer and guitarist of the duo the White Stripes. White has enjoyed consistent critical and popular success and is widely c ...

, he was also a founder of the

Irish Citizen Army

The Irish Citizen Army (), or ICA, was a small paramilitary group of trained trade union volunteers from the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union (ITGWU) established in Dublin for the defence of workers' demonstrations from the Dublin M ...

(ICA; a paramilitary group which was integral to both the

Dublin lock-out

The Dublin lock-out was a major industrial dispute between approximately 20,000 workers and 300 employers that took place in Ireland's capital and largest city, Dublin. The dispute, lasting from 26 August 1913 to 18 January 1914, is often vi ...

and the

Easter Rising

The Easter Rising ( ga, Éirí Amach na Cásca), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with t ...

). Larkin was a leading figure in the

Syndicalist

Syndicalism is a revolutionary current within the left-wing of the labor movement that seeks to unionize workers according to industry and advance their demands through strikes with the eventual goal of gaining control over the means of pr ...

movement.

Larkin was born to Irish parents in

Toxteth

Toxteth is an inner-city area of Liverpool in the historic county of Lancashire and the ceremonial county of Merseyside.

Toxteth is located to the south of Liverpool city centre, bordered by Aigburth, Canning, Dingle, and Edge Hill.

The area ...

,

Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

, England.

Growing up in poverty, he received little formal education and began working in a variety of jobs while still a child. He became a full-time trade union organiser in 1905.

Larkin moved to

Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdom ...

in 1907, where he was involved in trade unionism and syndicalist strike action including organising the

1907 Belfast Dock strike

The Belfast Dock strike or Belfast lockout took place in Belfast, Ireland from 26 April to 28 August 1907. The strike was called by Liverpool-born trade union leader James Larkin who had successfully organised the dock workers to join the Nation ...

. Larkin later moved south and organised workers in Dublin, Cork and Waterford, with considerable success. He founded the

Irish Transport and General Workers' Union after his expulsion from the

National Union of Dock Labourers

The National Union of Dock Labourers (NUDL) was a trade union in the United Kingdom which existed between 1889 and 1922.

History

It was formed in Glasgow in 1889 but moved its headquarters to Liverpool within a few years and was thereafter ...

for his taking part in strike action in Dublin against union instructions, this new union would quickly replace the NUDL in Ireland. He later moved to Dublin which would become the headquarters of his union and the focus of his union activity, as well as where the Irish

Labour Party would be formed. He is perhaps best known for his role in organising the 1913 strike that led to the

Dublin lock-out

The Dublin lock-out was a major industrial dispute between approximately 20,000 workers and 300 employers that took place in Ireland's capital and largest city, Dublin. The dispute, lasting from 26 August 1913 to 18 January 1914, is often vi ...

. The lock-out was an industrial dispute over workers pay and conditions as well as their right to organise, and received world-wide attention and coverage. It has been described as the "coming of age of the Irish trade union movement". The Irish Citizen Army was formed during the lock-out to protect striking workers from police violence. Not long after the lockout Larkin assumed direct command of the ICA, beginning the process of its reform into a revolutionary paramilitary organisation by arming them with

Mauser rifles

Mauser, originally Königlich Württembergische Gewehrfabrik ("Royal Württemberg Rifle Factory"), was a German arms manufacturer. Their line of bolt-action rifles and semi-automatic pistols has been produced since the 1870s for the German arm ...

bought from Germany by the

Irish Volunteers

The Irish Volunteers ( ga, Óglaigh na hÉireann), sometimes called the Irish Volunteer Force or Irish Volunteer Army, was a military organisation established in 1913 by Irish nationalists and republicans. It was ostensibly formed in respon ...

and smuggled into Ireland at Howth in July 1914.

[Charles Townshend, "Easter 1916: The Irish Rebellion", p.93.]

In October 1914 Larkin left Ireland and travelled to America to raise funds for the ITGWU and the ICA, leaving Connolly in charge of both organisations. During his time in America, Larkin became involved in the socialist movement there, becoming a member of the

Socialist Party of America

The Socialist Party of America (SPA) was a socialist political party in the United States formed in 1901 by a merger between the three-year-old Social Democratic Party of America and disaffected elements of the Socialist Labor Party of Ameri ...

. Larkin then became involved in the early communist movement in America, and he was later jailed in 1920 in the midst of the

Red Scare

A Red Scare is the promotion of a widespread fear of a potential rise of communism, anarchism or other leftist ideologies by a society or state. The term is most often used to refer to two periods in the history of the United States which ar ...

after being found guilty of 'criminal anarchy'. He then spent several years in

Sing Sing

Sing Sing Correctional Facility, formerly Ossining Correctional Facility, is a maximum-security prison operated by the New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision in the village of Ossining, New York. It is about north of ...

, before he was eventually pardoned by the Governor of New York

Al Smith

Alfred Emanuel Smith (December 30, 1873 – October 4, 1944) was an American politician who served four terms as Governor of New York and was the Democratic Party's candidate for president in 1928.

The son of an Irish-American mother and a Ci ...

in 1923 and later deported. Larkin then returned to Ireland where he again became involved in Irish socialism and politics, both in the Labour Party and then his newly formed

Irish Worker League

The Irish Worker League was an Irish communist party, established in September 1923 by Jim Larkin, following his return to Ireland. Larkin re-established the newspaper '' The Irish Worker''. The Irish Worker League (IWL) superseded the first ...

. Connolly by this time had been executed for his part in the

Easter Rising

The Easter Rising ( ga, Éirí Amach na Cásca), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with t ...

and Larkin mourned the passing of his friend and colleague.

Larkin also formed the

Workers' Union of Ireland

The Workers' Union of Ireland (WUI), later the Federated Workers' Union of Ireland, was an Irish trade union formed in 1924. In 1990, it merged with the Irish Transport and General Workers Union to form the Services, Industrial, Professional an ...

(WUI) after he lost control of the ITGWU, the WUI was affiliated to

Red International of Labour Unions

The Red International of Labor Unions (russian: Красный интернационал профсоюзов, translit=Krasnyi internatsional profsoyuzov, RILU), commonly known as the Profintern, was an international body established by the Comm ...

(Promintern) soon after its formation. Larkin served as a

Teachta Dála

A Teachta Dála ( , ; plural ), abbreviated as TD (plural ''TDanna'' in Irish, TDs in English), is a member of Dáil Éireann, the lower house of the Oireachtas (the Irish Parliament). It is the equivalent of terms such as ''Member of Parl ...

on three occasions, and two of his sons (

James Larkin Jnr

James Larkin Jnr (20 August 1904 – 18 February 1969) was an Irish Labour Party politician and trade union official.

He was born in Liverpool, England, the eldest of four sons of James Larkin, trade union leader, and Elizabeth Larkin (née ...

and

Denis Larkin

Denis Larkin (1908 – 2 July 1987) was an Irish Labour Party politician and trade union official. He was the son of Dublin trade union leader, James Larkin. He was first elected to Dáil Éireann as a Labour Party Teachta Dála (TD) for the ...

) also served as

Teachta Dála

A Teachta Dála ( , ; plural ), abbreviated as TD (plural ''TDanna'' in Irish, TDs in English), is a member of Dáil Éireann, the lower house of the Oireachtas (the Irish Parliament). It is the equivalent of terms such as ''Member of Parl ...

. Jim Larkin served as Labour Party deputy in

Dáil Éireann

Dáil Éireann ( , ; ) is the lower house, and principal chamber, of the Oireachtas (Irish legislature), which also includes the President of Ireland and Seanad Éireann (the upper house).Article 15.1.2º of the Constitution of Ireland rea ...

from 1943 to 1944, leaving Dáil Éireann for the last time in 1944, and dying in Dublin in 1947. Catholic

Archbishop of Dublin

The Archbishop of Dublin is an archepiscopal title which takes its name after Dublin, Ireland. Since the Reformation, there have been parallel apostolic successions to the title: one in the Catholic Church and the other in the Church of Ireland ...

John Charles McQuaid

John Charles McQuaid, C.S.Sp. (28 July 1895 – 7 April 1973), was the Catholic Primate of Ireland and Archbishop of Dublin between December 1940 and January 1972. He was known for the unusual amount of influence he had over successive govern ...

gave his funeral mass, and the ICA in its last public appearance escorted his funeral procession through Dublin to his burial site at

Glasnevin Cemetery

Glasnevin Cemetery ( ga, Reilig Ghlas Naíon) is a large cemetery in Glasnevin, Dublin, Ireland which opened in 1832. It holds the graves and memorials of several notable figures, and has a museum.

Location

The cemetery is located in Glasne ...

.

Larkin was respected by commentators both during and after his lifetime, with

George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

describing him as the "greatest Irishman since

Parnell", his friend and colleague in the labour movement

James Connolly

James Connolly ( ga, Séamas Ó Conghaile; 5 June 1868 – 12 May 1916) was an Irish republican, socialist and trade union leader. Born to Irish parents in the Cowgate area of Edinburgh, Scotland, Connolly left school for working life at the a ...

describing him as a "man of genius, of splendid vitality, great in his conceptions, magnificent in his courage", and

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

noting him as 'a remarkable speaker and a man of seething energy

hoperformed miracles amongst the unskilled workers'.

[Lenin, V I. Class war in Dublin. Severnaya Pravda. 29 August 1913] However other commentators have noted that Larkin was "vilified as a wrecker by former comrades", with anthologist

Donal Nevin

Donal Nevin (20 January 1924 – 16 December 2012) was an Irish trade unionist.

Born in Limerick, Nevin was educated at a Christian Brothers school before joining the civil service. His next job, from 1949, was as research officer of the Ir ...

noting that some of Larkin's actions, including his attacks on others in the labour movement, meant Larkin had "alienated practically all the leaders of the movement

ndthe mass of trade union members" by the mid-1920s.

"Big Jim" Larkin continues to occupy a position in

Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

's collective memory and streetscape, with a statue of him unveiled on

O'Connell Street

O'Connell Street () is a street in the centre of Dublin, Ireland, running north from the River Liffey. It connects the O'Connell Bridge to the south with Parnell Street to the north and is roughly split into two sections bisected by Hen ...

in 1979.

Early years

Larkin was said to have been born on 21 January 1876, and this was the date that he himself believed was accurate, however it is now believed that he was actually born 28 January 1874. He was the second eldest son of Irish emigrants, James Larkin, from

Drumintee and Mary Ann McNulty, from

Burren, County Down

Burren () is a small village in County Down, Northern Ireland. It is near Warrenpoint. It is not to be confused with the Burren area in County Clare.

Places of interest

Burren Heritage Centre is a converted national school at the foot of t ...

. The impoverished Larkin family lived in the slums of Liverpool during the early years of his life. From the age of seven, he attended school in the mornings and worked in the afternoons to supplement the family income, a common arrangement in working-class families at the time. At the age of fourteen, after the death of his father, he was apprenticed to the firm his father had worked for, but was dismissed after two years. He was unemployed for a time and then worked as a sailor and

docker. By 1903, he was a dock foreman, and on 8 September of that year, he married Elizabeth Brown.

From 1893, Larkin developed an interest in socialism and became a member of the

Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse working-class candidates ...

. In 1905, he was one of the few foremen to take part in a strike on the Liverpool docks. He was elected to the strike committee, and although he lost his foreman's job as a result, his performance so impressed the

National Union of Dock Labourers

The National Union of Dock Labourers (NUDL) was a trade union in the United Kingdom which existed between 1889 and 1922.

History

It was formed in Glasgow in 1889 but moved its headquarters to Liverpool within a few years and was thereafter ...

(NUDL) that he was appointed a temporary organiser. He later gained a permanent position with the union, which, in 1906, sent him to

Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, where he successfully organised workers in

Preston

Preston is a place name, surname and given name that may refer to:

Places

England

*Preston, Lancashire, an urban settlement

**The City of Preston, Lancashire, a borough and non-metropolitan district which contains the settlement

**County Boro ...

and

Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popu ...

. Larkin campaigned against Chinese immigration, presenting it as a threat that would undercut workers, leading processions in 1906 in Liverpool with fifty dockers dressed as 'Chinamen', wearing faux-

'pigtails' and wearing powder to provide a 'yellow countenance'.

Organising Irish labour movement (1907–14)

Belfast Dock Strike

In January 1907, Larkin undertook his first task on behalf of the trade union movement in Ireland, when he arrived in

Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdom ...

to organise the city's dock workers for the NUDL. He succeeded in unionising the workforce, and as employers refused to meet the wage demands, he called the dockers out on strike in June.

The Belfast Dock strike was soon joined by carters and coal men, the latter settling their dispute after a month. With active support from the

Independent Orange Order and its Grand Master,

R. Lindsay Crawford

R. or r. may refer to:

* '' Reign'', the period of time during which an Emperor, king, queen, etc., is ruler.

* '' Rex'', abbreviated as R., the Latin word meaning King

* ''Regina'', abbreviated as R., the Latin word meaning Queen

* or , abbrevia ...

, urging the "unity of all Irishmen",

Larkin succeeded in uniting

Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

and

Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

workers and even persuaded the local

Royal Irish Constabulary

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC, ga, Constáblacht Ríoga na hÉireann; simply called the Irish Constabulary 1836–67) was the police force in Ireland from 1822 until 1922, when all of the country was part of the United Kingdom. A separate ...

to strike at one point, but the strike ended by November without having achieved significant success. Tensions regarding leadership arose between Larkin and NUDL general secretary

James Sexton

Sir James Sexton CBE (13 April 1856 – 27 December 1938) was a British trade unionist and politician.

Sexton was born in Newcastle upon Tyne on 13 April 1856 to an Irish-born family of market traders, who soon moved to St Helens, Lancashire. ...

. The latter's handling of negotiations and agreement to a disastrous settlement for the last of the strikers resulted in a lasting rift between Sexton and Larkin.

Formation of Irish Transport and General Workers' Union and founding of the Irish Labour Party

In 1908, Larkin moved south and organised workers in

Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

,

Cork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

and

Waterford

"Waterford remains the untaken city"

, mapsize = 220px

, pushpin_map = Ireland#Europe

, pushpin_map_caption = Location within Ireland##Location within Europe

, pushpin_relief = 1

, coordinates ...

, with considerable success. His involvement, against union instructions, in a dispute in Dublin resulted in his expulsion from the NUDL. The union later prosecuted him for diverting union funds to give strike pay to Cork workers engaged in an unofficial dispute. After trial and conviction for embezzlement in 1910, he was sentenced to prison for a year. This was widely regarded as unjust, and the

Lord-Lieutenant

A lord-lieutenant ( ) is the British monarch's personal representative in each lieutenancy area of the United Kingdom. Historically, each lieutenant was responsible for organising the county's militia. In 1871, the lieutenant's responsibilit ...

,

Lord Aberdeen

George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen, (28 January 178414 December 1860), styled Lord Haddo from 1791 to 1801, was a British statesman, diplomat and landowner, successively a Tory, Conservative and Peelite politician and specialist in ...

, pardoned him after he had served three months in prison. Also in 1908,

Arthur Griffith

Arthur Joseph Griffith ( ga, Art Seosamh Ó Gríobhtha; 31 March 1871 – 12 August 1922) was an Irish writer, newspaper editor and politician who founded the political party Sinn Féin. He led the Irish delegation at the negotiations that pro ...

during the Dublin carter's strike described Larkin as an "Englishman importing foreign political disruption into this country and putting native industry at risk".

After his expulsion from the NUDL, Larkin founded the

Irish Transport and General Workers' Union (ITGWU) at the end of December 1908. The organisation exists today as the

Services Industrial Professional & Technical Union (SIPTU). It quickly gained the affiliation of the NUDL branches in Dublin, Cork,

Dundalk

Dundalk ( ; ga, Dún Dealgan ), meaning "the fort of Dealgan", is the county town (the administrative centre) of County Louth, Ireland. The town is on the Castletown River, which flows into Dundalk Bay on the east coast of Ireland. It is h ...

, Waterford and

Sligo

Sligo ( ; ga, Sligeach , meaning 'abounding in shells') is a coastal seaport and the county town of County Sligo, Ireland, within the western province of Connacht. With a population of approximately 20,000 in 2016, it is the largest urban ce ...

. The

Derry

Derry, officially Londonderry (), is the second-largest city in Northern Ireland and the fifth-largest city on the island of Ireland. The name ''Derry'' is an anglicisation of the Old Irish name (modern Irish: ) meaning 'oak grove'. The ...

and

Drogheda

Drogheda ( , ; , meaning "bridge at the ford") is an industrial and port town in County Louth on the east coast of Ireland, north of Dublin. It is located on the Dublin–Belfast corridor on the east coast of Ireland, mostly in County Louth ...

NUDL branches stayed with the British union, and

Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdom ...

split along sectarian lines. Early in the new year, 1909, Larkin moved to Dublin, which became the main base of the ITGWU and the focus of all his future union activity in Ireland.

In June 1911, Larkin established a newspaper, ''

The Irish Worker and People's Advocate'', as a pro-labour alternative to the capitalist-owned press. This organ was characterised by a campaigning approach and the denunciation of unfair employers and of Larkin's political enemies. Its columns also included pieces by intellectuals. The paper was produced until its suppression by the authorities in 1915. Afterwards, the ''Worker'' metamorphosed into the new ''Ireland Echo''.

In May 1912, in partnership with

James Connolly

James Connolly ( ga, Séamas Ó Conghaile; 5 June 1868 – 12 May 1916) was an Irish republican, socialist and trade union leader. Born to Irish parents in the Cowgate area of Edinburgh, Scotland, Connolly left school for working life at the a ...

and

William O'Brien

William O'Brien (2 October 1852 – 25 February 1928) was an Irish nationalist, journalist, agrarian agitator, social revolutionary, politician, party leader, newspaper publisher, author and Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons ...

Larkin formed the

Irish Labour Party as the political wing of the

Irish Trades Union Congress

The Irish Trades Union Congress (ITUC) was a union federation covering the island of Ireland.

History

Until 1894, representatives of Irish trade unions attended the British Trades Union Congress (TUC). However, many felt that they had little im ...

. Later that year, he was elected to

Dublin Corporation

Dublin Corporation (), known by generations of Dubliners simply as ''The Corpo'', is the former name of the city government and its administrative organisation in Dublin since the 1100s. Significantly re-structured in 1660-1661, even more sign ...

. He did not hold his seat long, as a month later he was removed because he had a criminal record from his conviction in 1910.

Under Larkin's leadership the union continued to grow, reaching approximately 20,000 members in the time leading up to the Dublin lock-out. In August 1913 during the lock-out, Larkin was described by

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

as a 'talented leader' as well as 'a remarkable speaker and a man of seething energy

hohas performed miracles amongst the unskilled workers'.

Dublin Lockout, 1913

Build up to the lock-out, and its proceedings

In early 1913, Larkin achieved some successes in industrial disputes in Dublin and, notably, in the

Sligo Dock strike; these involved frequent recourse to

sympathetic strikes and

blacking (boycotting) of goods. Two major employers,

Guinness

Guinness () is an Irish dry stout that originated in the brewery of Arthur Guinness at St. James's Gate, Dublin, Ireland, in 1759. It is one of the most successful alcohol brands worldwide, brewed in almost 50 countries, and available in ov ...

and the

Dublin United Tramway Company, were the main targets of Larkin's organising ambitions. Both had craft unions for skilled workers, but Larkin's main aim was to unionise the unskilled workers as well. He coined the slogan "A fair day's work for a fair day's pay".

Larkin advocated

Syndicalism

Syndicalism is a revolutionary current within the left-wing of the labor movement that seeks to unionize workers according to industry and advance their demands through strikes with the eventual goal of gaining control over the means of prod ...

, which was a revolutionary brand of socialism. Larkin gained few supporters from within, particularly from the British

Trade Union Congress

The Trades Union Congress (TUC) is a national trade union centre, a federation of trade unions in England and Wales, representing the majority of trade unions. There are 48 affiliated unions, with a total of about 5.5 million members. Frances ...

who did not want strike action such as the lock-out to lead to a growth in radicalism.

Guinness staff were relatively well-paid and enjoyed generous benefits from a paternalistic management that refused to join a lockout of unionised staff by virtually all the major Dublin employers. This was far from the case on the tramways.

The chairman of the Dublin United Tramway Company, industrialist and newspaper proprietor

William Martin Murphy

William Martin Murphy (6 January 1845 – 26 June 1919) was an Irish businessman, newspaper publisher and politician. A member of parliament (MP) representing Dublin from 1885 to 1892, he was dubbed "William ''Murder'' Murphy" among the Iri ...

, was determined not to allow the ITGWU to unionise his workforce. On 15 August, he dismissed 40 workers he suspected of ITGWU membership, followed by another 300 over the next week. On 26 August 1913, the tramway workers officially went on strike. Led by Murphy, over 400 of the city's employers retaliated by requiring their workers to sign a pledge not to be a member of the ITGWU and not to engage in sympathetic strikes.

The resulting industrial dispute was the most severe in Ireland's history. Employers in Dublin engaged in a sympathetic

lockout of their workers when the latter refused to sign the pledge, employing

blackleg labour from Britain and from elsewhere in Ireland. Guinness, the largest employer in Dublin, refused the employers' call to lock out its workers but it sacked 15 workers who struck in sympathy. Dublin's workers, amongst the poorest in the whole of what was then the

Great Britain and Ireland, were forced to survive on generous but inadequate donations from the British

Trades Union Congress

The Trades Union Congress (TUC) is a national trade union centre, a federation of trade unions in England and Wales, representing the majority of trade unions. There are 48 affiliated unions, with a total of about 5.5 million members. Frances ...

(TUC) and sources in Ireland, distributed by the ITGWU.

For seven months the lockout affected tens of thousands of Dublin workers and employers, with Larkin portrayed as the villain by Murphy's three main newspapers, the ''

Irish Independent

The ''Irish Independent'' is an Irish daily newspaper and online publication which is owned by Independent News & Media (INM), a subsidiary of Mediahuis.

The newspaper version often includes glossy magazines.

Traditionally a broadsheet new ...

'', the ''

Sunday Independent

''Sunday Independent'' may refer to:

* ''The Independent'' (Perth)

* ''Sunday Independent'' (South Africa)

* ''Sunday Independent'' (England), in south-west England, UK

* ''Sunday Independent'' (Ireland), in Ireland

See also

*'' The Independent on ...

'' and the ''

Evening Herald

''The Herald'' is a nationwide mid-market tabloid newspaper headquartered in Dublin, Ireland, and published by Independent News & Media who are a subsidiary of Mediahuis. It is published Monday–Saturday. The newspaper was known as the ''Even ...

'', and by other bourgeois publications in Ireland.

Other leaders in the ITGWU at the time were

James Connolly

James Connolly ( ga, Séamas Ó Conghaile; 5 June 1868 – 12 May 1916) was an Irish republican, socialist and trade union leader. Born to Irish parents in the Cowgate area of Edinburgh, Scotland, Connolly left school for working life at the a ...

and

William O'Brien

William O'Brien (2 October 1852 – 25 February 1928) was an Irish nationalist, journalist, agrarian agitator, social revolutionary, politician, party leader, newspaper publisher, author and Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons ...

; influential figures such as

Patrick Pearse,

Constance Markievicz

Constance Georgine Markievicz ( pl, Markiewicz ; ' Gore-Booth; 4 February 1868 – 15 July 1927), also known as Countess Markievicz and Madame Markievicz, was an Irish politician, revolutionary, nationalist, suffragist, socialist, and the fir ...

and

William Butler Yeats

William Butler Yeats (13 June 186528 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival and became a pillar of the Irish liter ...

supported the workers in the generally anti-Larkin Irish press. ''The Irish Worker'' published the names and addresses of strike-breakers, the ''Irish Independent'' published the names and addresses of men and women who attempted to send their children out of the city to be cared for in foster homes in Belfast and Britain.

[

A group including ]Tom Kettle

Thomas Michael Kettle (9 February 1880 – 9 September 1916) was an Irish economist, journalist, barrister, writer, war poet, soldier and Home Rule politician. As a member of the Irish Parliamentary Party, he was Member of Parliament (MP) for ...

and Thomas MacDonagh

Thomas Stanislaus MacDonagh ( ga, Tomás Anéislis Mac Donnchadha; 1 February 1878 – 3 May 1916) was an Irish political activist, poet, playwright, educationalist and revolutionary leader. He was one of the seven leaders of the Easter Rising ...

formed the Industrial Peace Committee to attempt to negotiate between employers and workers; the employers refused to meet them.

Larkin and others were arrested for sedition

Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that tends toward rebellion against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent toward, or insurrection against, esta ...

on 28 August, and he was released on bail later that day. Connolly told the authorities "I do not recognise the English government in Ireland at all. I do not even recognise the King except when I am compelled to do so". On 30 August a warrant for Larkin's arrest was put out claiming he had again been seditious and, had incited people to riot and to pillage shops. When a meeting called by Larkin for Sunday 31 August 1913 was proscribed, Constance Markievicz

Constance Georgine Markievicz ( pl, Markiewicz ; ' Gore-Booth; 4 February 1868 – 15 July 1927), also known as Countess Markievicz and Madame Markievicz, was an Irish politician, revolutionary, nationalist, suffragist, socialist, and the fir ...

and her husband Casimir disguised Larkin in Casimir's frock coat and trousers and stage makeup and beard, and Nellie Gifford, who was unknown to the police, led him into William Martin Murphy's Imperial Hotel Imperial Hotel or Hotel Imperial may refer to:

Hotels Australia

* Imperial Hotel, Ravenswood, Queensland

* Imperial Hotel, York, Western Australia

Austria

* Hotel Imperial, Vienna

India

* The Imperial, New Delhi

Ireland

* Imperial Hotel, D ...

, pretending to be her stooped, deaf old clergyman uncle (to disguise his instantly recognisable Liverpool accent). Larkin tore off his beard inside the hotel and raced to a balcony, where he shouted his speech to the crowd below. The police – some 300 Royal Irish Constabulary

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC, ga, Constáblacht Ríoga na hÉireann; simply called the Irish Constabulary 1836–67) was the police force in Ireland from 1822 until 1922, when all of the country was part of the United Kingdom. A separate ...

reinforcing Dublin Metropolitan Police

The Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP) was the police force of Dublin, Ireland, from 1836 to 1925, when it was amalgamated into the new Garda Síochána.

History

19th century

The Dublin city police had been subject to major reforms in 1786 and ...

– savagely baton-charged the crowd, injuring between 400 and 600 people. MP Handel Booth, who was present, said that the police "behaved like men possessed. They drove the crowd into the side streets to meet other batches of the government's minions, wildly striking with their truncheons at everyone within reach ... The few roughs got away first, most respectable people left their hats and crawled away with bleeding heads. Kicking victims when prostrate was a settled part of the police programme." Larkin went into hiding, charged with incitement to breach the peace. Larkin was later re-arrested, charged with sedition

Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that tends toward rebellion against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent toward, or insurrection against, esta ...

and was handed a 7 months imprisonment. The Attorney General claimed Larkin had said: ‘People make kings and can unmake them. I never said ‘God Save the King’, but in derision. I say it now in derision.’ to a crowd of 8,000 people from the windows of Liberty Hall

Liberty Hall ( ga, Halla na Saoirse), in Dublin, Ireland, is the headquarters of the Services, Industrial, Professional, and Technical Union (SIPTU). Designed by Desmond Rea O'Kelly, it was completed in 1965. It was for a time the tallest ...

. The sentence was widely seen as unjust. Larkin was released about a week later.

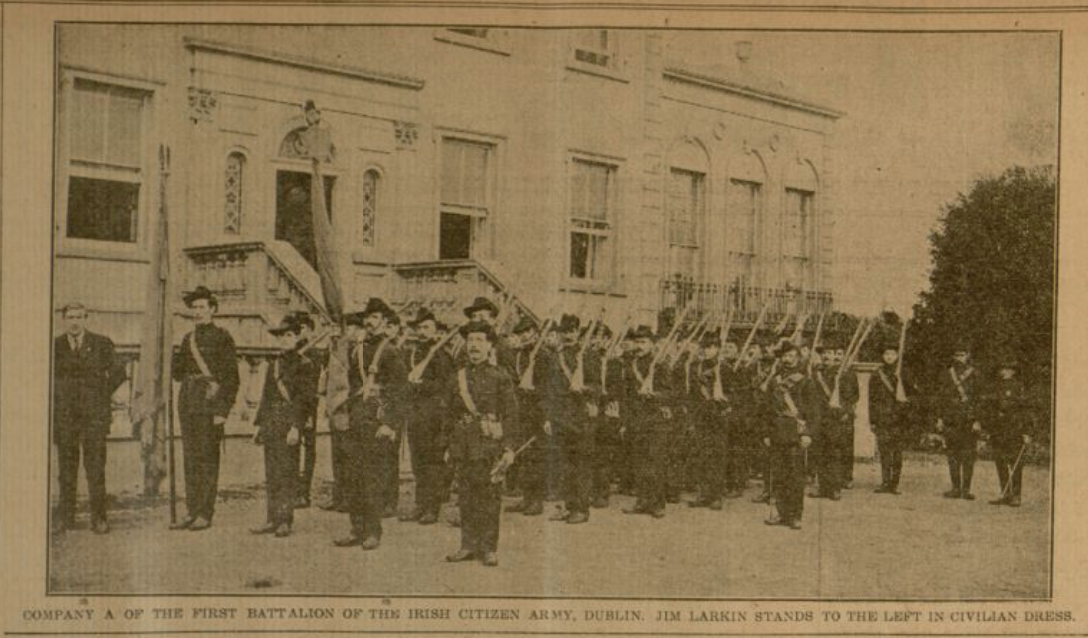

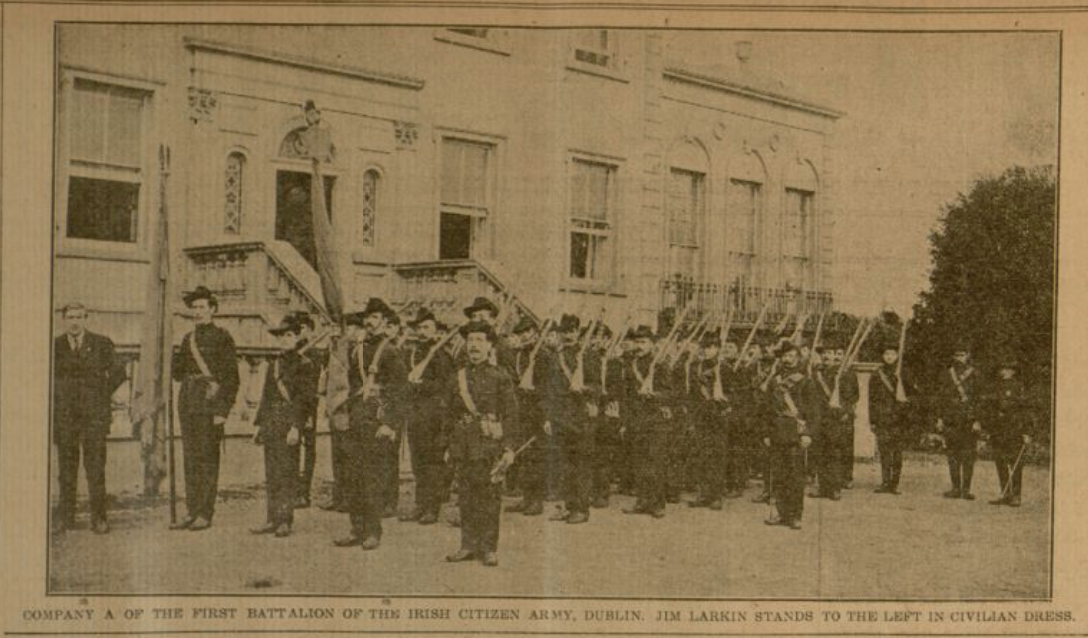

Formation of the Irish Citizen Army

The violence at union rallies during the strike prompted Larkin to call for a workers' militia to be formed to protect themselves against the police, thus Larkin,

The violence at union rallies during the strike prompted Larkin to call for a workers' militia to be formed to protect themselves against the police, thus Larkin, James Connolly

James Connolly ( ga, Séamas Ó Conghaile; 5 June 1868 – 12 May 1916) was an Irish republican, socialist and trade union leader. Born to Irish parents in the Cowgate area of Edinburgh, Scotland, Connolly left school for working life at the a ...

, and Jack White

John Anthony White (; born July 9, 1975), commonly known as Jack White, is an American musician, best known as the lead singer and guitarist of the duo the White Stripes. White has enjoyed consistent critical and popular success and is widely c ...

created the Irish Citizen Army

The Irish Citizen Army (), or ICA, was a small paramilitary group of trained trade union volunteers from the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union (ITGWU) established in Dublin for the defence of workers' demonstrations from the Dublin M ...

. The Citizen Army for the duration of the lock-out was armed with hurleys (sticks used in hurling, a traditional Irish sport) and bats to protect workers' demonstrations from the police. Jack White, a former Captain in the British Army, volunteered to train this army and offered £50 towards the cost of shoes to workers so that they could train. In addition to its role as a self-defence organisation, the Army, which was drilled in Croydon Park in Fairview by White, provided a diversion for workers unemployed and idle during the dispute.

End of the lock-out

The lock-out eventually concluded in early 1914 when calls by Connolly and Larkin for a sympathetic strike in Britain were rejected by the British TUC. Larkin's attacks on the TUC leadership for this stance also led to the cessation of financial aid to the ITGWU, which in any case was not affiliated to the TUC.

Although the actions of the ITGWU and the smaller UBLU were unsuccessful in achieving substantially better pay and conditions for the workers, they marked a watershed in Irish labour history. The principle of union action and workers' solidarity had been firmly established. Perhaps even more importantly, Larkin's rhetoric condemning poverty and injustice and calling for the oppressed to stand up for themselves made a lasting impression.

Not long after the lockout Jack White resigned as commander and Larkin assumed direct command of the ICA. Beginning the process of its reform into a revolutionary paramilitary organisation by arming them with

The lock-out eventually concluded in early 1914 when calls by Connolly and Larkin for a sympathetic strike in Britain were rejected by the British TUC. Larkin's attacks on the TUC leadership for this stance also led to the cessation of financial aid to the ITGWU, which in any case was not affiliated to the TUC.

Although the actions of the ITGWU and the smaller UBLU were unsuccessful in achieving substantially better pay and conditions for the workers, they marked a watershed in Irish labour history. The principle of union action and workers' solidarity had been firmly established. Perhaps even more importantly, Larkin's rhetoric condemning poverty and injustice and calling for the oppressed to stand up for themselves made a lasting impression.

Not long after the lockout Jack White resigned as commander and Larkin assumed direct command of the ICA. Beginning the process of its reform into a revolutionary paramilitary organisation by arming them with Mauser rifles

Mauser, originally Königlich Württembergische Gewehrfabrik ("Royal Württemberg Rifle Factory"), was a German arms manufacturer. Their line of bolt-action rifles and semi-automatic pistols has been produced since the 1870s for the German arm ...

bought from Germany by the Irish Volunteers

The Irish Volunteers ( ga, Óglaigh na hÉireann), sometimes called the Irish Volunteer Force or Irish Volunteer Army, was a military organisation established in 1913 by Irish nationalists and republicans. It was ostensibly formed in respon ...

and smuggled into Ireland at Howth in July 1914.[

]

In the US - Socialist, Irish Republican and Communist activism (1914–23)

After the lock-out

Exhausted by the demands of organising union work; Larkin fell into bouts of depression, took a declining interest in the now crippled ITGWU, and became increasingly difficult to work with. Speculation had risen during the lock-out that he was planning to leave for America. A speaking tour of the New World had been suggested to Larkin by Bill Haywood

William Dudley "Big Bill" Haywood (February 4, 1869 – May 18, 1928) was an American labor organizer and founding member and leader of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and a member of the executive committee of the Socialist Party of A ...

in November 1913 and the following month in the growing speculation prompted the New York Times to publish an editorial simply titled 'Larkin is coming'. This dismayed colleagues in the ITGWU and Larkin felt obliged to deny that he was planning on running away. However, noting the effect that the strain of the lock-out on Larkin, union officials reluctantly concluded that a break would probably be of great benefit to him, and thus following the advice given by 'Big Bill', 'Big Jim' left for America. His decision to leave dismayed many union activists including a large number of his colleagues in the ITGWU. In addition to recuperating from the strain of the lockout and undertaking a tour of the United States, Larkin also intended to raise funds for the union and the fledgling ICA, and to rebuild their headquarters Liberty Hall

Liberty Hall ( ga, Halla na Saoirse), in Dublin, Ireland, is the headquarters of the Services, Industrial, Professional, and Technical Union (SIPTU). Designed by Desmond Rea O'Kelly, it was completed in 1965. It was for a time the tallest ...

. Many in the union assumed that Larkin's trip would be a short one and that he would soon return. However, it quickly became clear that this would not be the case, shortly before his departure he declined a request by the Irish Trades Union Congress

The Irish Trades Union Congress (ITUC) was a union federation covering the island of Ireland.

History

Until 1894, representatives of Irish trade unions attended the British Trades Union Congress (TUC). However, many felt that they had little im ...

to join a two-man mission to raise funds for the Labour Party, replying that if he went he would be 'going alone and freelance'. His intention was to agitate in America rather than organise, but it is unclear whether he intended to return. Larkin set sail for America on 25 October 1914, leaving long time associate James Connolly

James Connolly ( ga, Séamas Ó Conghaile; 5 June 1868 – 12 May 1916) was an Irish republican, socialist and trade union leader. Born to Irish parents in the Cowgate area of Edinburgh, Scotland, Connolly left school for working life at the a ...

in charge of the ITGWU and the ICA, the latter of which he would soon utilise as a revolutionary force.

Arriving in America - activism and links to espionage

Larkin arrived in New York on 5 November 1914. Following his arrival there were positive initial prospects, the lock-out had been widely reported in America and he was well received by socialists there. He found support from both socialists and Irish-Americans, who were eagerly interested to hear his position on the World War which was by now raging throughout Europe. Opposition to the war was intended to be his main position whilst in America. Upon presenting his credentials to the

Larkin arrived in New York on 5 November 1914. Following his arrival there were positive initial prospects, the lock-out had been widely reported in America and he was well received by socialists there. He found support from both socialists and Irish-Americans, who were eagerly interested to hear his position on the World War which was by now raging throughout Europe. Opposition to the war was intended to be his main position whilst in America. Upon presenting his credentials to the Socialist Party of America

The Socialist Party of America (SPA) was a socialist political party in the United States formed in 1901 by a merger between the three-year-old Social Democratic Party of America and disaffected elements of the Socialist Labor Party of Ameri ...

and John Devoy, the Irish leader of Clan na Gael

Clan na Gael ( ga, label=modern Irish orthography, Clann na nGael, ; "family of the Gaels") was an Irish republican organization in the United States in the late 19th and 20th centuries, successor to the Fenian Brotherhood and a sister org ...

(the leading Irish republican supporting organisation in America), his services were quickly taken up by both and he also became involved in the Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines general ...

union (the Wobblies). Within days of arriving in the country, he addressed a crowd of 15,000 people gathered at Madison Square Garden

Madison Square Garden, colloquially known as The Garden or by its initials MSG, is a multi-purpose indoor arena in New York City. It is located in Midtown Manhattan between Seventh and Eighth avenues from 31st to 33rd Street, above Pennsylv ...

to celebrate the election of Socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

candidate Meyer London

Meyer London (December 29, 1871 – June 6, 1926) was an American politician from New York City. He represented the Lower East Side of Manhattan and was one of only two members of the Socialist Party of America elected to the United States Congre ...

to the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

. Soon after his speech at Maddison Garden he was invited by Devoy to speak to a combined audience of German Uhlans and Irish Volunteers in Philadelphia where he enthusiastically called for money and arms for the Republican cause in Ireland to a cheering crowd. During this speech Larkin showed one of the rifles that had been smuggled into Ireland at Howth which he noted could be better but still worked (he added that better weapons could be obtained with more money), and compared it with a rifle given to the Irish Volunteers by John Redmond

John Edward Redmond (1 September 1856 – 6 March 1918) was an Irish nationalist politician, barrister, and MP in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom. He was best known as leader of the moderate Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) from ...

, which was an obsolete weapon for which no new ammunition could be procured, using this to vilify Redmond as a traitor to the Irish people who had had no intention of effectively arming the movement for Irish independence.[The Gaelic American - Vol. XI, No. 47, 21 November 1914, Whole Number 584.] He also claimed that in the process of receiving and protecting the guns, 100 of his men from the ICA with no ammunition or bayonets had faced and routed 150 of the King's Own Scottish Borderers

The King's Own Scottish Borderers (KOSBs) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army, part of the Scottish Division. On 28 March 2006 the regiment was amalgamated with the Royal Scots, the Royal Highland Fusiliers (Princess Margaret's O ...

, who he disparagingly said had been referred to as 'England's best'.[The Gaelic American - Vol. XI, No. 49, 5 December 1914, Whole Number 586.] In a speech to Clan na Gael in November 1914 Larkin promoted his Irish Republican ideals stating 'I assure you that the workers of Ireland are on the side of the dear, dark-haired mother, whose call they never failed to answer yet ... again will the call ring out over hill and dale to the men who have always answered the call of Caithlin-ni-Houlihan. For seven hundred long, weary years we have waited for this hour. The flowing tide is with us ... nd we must beready for the Rising of the Moon'.Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

of 1917. This perceived association with German agents further distanced him American socialists, and his reputation as a syndicalist

Syndicalism is a revolutionary current within the left-wing of the labor movement that seeks to unionize workers according to industry and advance their demands through strikes with the eventual goal of gaining control over the means of pr ...

and association with the Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines general ...

was looked down on by the right wing of the Socialist Party of America.

Larkin was reported as having helped to disrupt Allied munitions shipments in New York City during

Larkin was reported as having helped to disrupt Allied munitions shipments in New York City during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. In 1937, he voluntarily assisted US lawyers investigating the Black Tom explosion

The Black Tom explosion was an act of sabotage by agents of the German Empire, to destroy U.S.-made munitions that were to be supplied to the Allies of World War I, Allies in World War I. The explosions, which occurred on July 30, 1916, in New Y ...

by providing an affidavit

An ( ; Medieval Latin for "he has declared under oath") is a written statement voluntarily made by an ''affiant'' or '' deponent'' under an oath or affirmation which is administered by a person who is authorized to do so by law. Such a stateme ...

from his home in Dublin. According to British Army Intelligence officer, Henry Landau:

'Larkin testified that he himself never took part in the actual sabotage campaign but, rather, confined himself to the organising of strikes to secure both higher pay and shorter hours for workmen and to prevent the shipment of munitions to the Allies.'

Larkin, however, had first hand knowledge of German sabotage operations, supplied them with intelligence and contacts and was involved in the transfer of monies from the Germans to Irish Republican causes. He maintained communication with his German contacts, however they began to tire of his refusals to co-operate with violence and broke contact with him after a rendezvous in Mexico City in 1917.

Communism and arrest for 'criminal anarchy'

Following this Larkin briefly worked with the IWW in San Francisco, before settling in New York becoming involved with the Socialist Party of America again. Taking advantage of the growing support for left wing politics, and also of the increasing support for Irish republicanism amongst Irish Americans to gain influence amongst its ranks. Larkin was instrumental in the establishment of the New York James Connolly Socialist Club on St Patrick's Day 1918. Whilst in America Larkin had become an enthusiastic supporter of the Soviets and following an address at the club by Jack Reed, who had recently returned from Russia, interest in the Bolsheviks was revitalised and Larkin decided to put all his efforts into reforming the SPA into a communist party. This meant that he had to turn down an offer to lead the St Lawrence Mill Strike in March 1919. The Connolly Club became the national hub of the new communist project, housing the offices of Larkin's SPA faction's ''Revolutionary Age'' and Reed's ''Voice of Labour''. In June 1919 Larkin topped the polls for elections to the national left-wing council, he supported the view that the left of the SPA should attempt to take control at its national convention in August, a minority faction favoured the immediate creation of a new communist party and left in protest. Larkin was expelled from the Socialist Party of America at its national convention along with numerous other sympathisers of the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

during the Red Scare

A Red Scare is the promotion of a widespread fear of a potential rise of communism, anarchism or other leftist ideologies by a society or state. The term is most often used to refer to two periods in the history of the United States which ar ...

of that year. As a result of this exodus, two new parties were formed from the ranks of the SPA's communist former members; the American Communist Party

The Communist Party USA, officially the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), is a communist party in the United States which was established in 1919 after a split in the Socialist Party of America following the Russian Revo ...

and the Communist Labor Party of America

The Communist Labor Party of America (CLPA) was one of the organizational predecessors of the Communist Party USA.

The group was established at the end of August 1919 following a three-way split of the Socialist Party of America. Although a legal ...

, favouring the latter as he believed the party to be more 'American' (something which Larkin believed was crucial) Larkin joined their ranks.

Larkin's speeches in support of the Soviets, his association with founding members of both the

Larkin's speeches in support of the Soviets, his association with founding members of both the American Communist Party

The Communist Party USA, officially the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), is a communist party in the United States which was established in 1919 after a split in the Socialist Party of America following the Russian Revo ...

and Communist Labor Party of America

The Communist Labor Party of America (CLPA) was one of the organizational predecessors of the Communist Party USA.

The group was established at the end of August 1919 following a three-way split of the Socialist Party of America. Although a legal ...

, and his radical publications made him a target of the "First Red Scare

The First Red Scare was a period during the early 20th-century history of the United States marked by a widespread fear of far-left movements, including Bolshevism and anarchism, due to real and imagined events; real events included the R ...

" that was sweeping the US and he was arrested on 7 November 1919 during a series of anti Bolshevik raids. Larkin was charged with 'criminal anarchy' due to his part in the publishing of the SPA's 'Left wing manifesto' in ''Revolutionary Age''. Larkin was released on 20 November after $15,000 bail was paid, of which John Devoy paid $5,000, he resumed his political activities but was under no illusion of what was to come, expecting to be handed a lengthy jail sentence. New York State Prosecutor Alexander Rourke took advantage of a query from Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard (officially New Scotland Yard) is the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, the territorial police force responsible for policing Greater London's 32 boroughs, but not the City of London, the square mile that forms London's ...

as to whether Larkin would be allowed to travel to South Africa to turn his allies in the Irish nationalist movement against him, including Devoy. In reality this request did not stem from any association with figures of authority in Britain, but rather a request by Archie Crawford

Archibald Crawford (1883 – 23 December 1924) was a Scottish-born South African trade union leader.

Born in Glasgow, Crawford completed an apprenticeship as a fitter, before joining the British Army. He served in the Second Boer War, after ...

, President of the South African Federation of Labour who wanted Larkin for a speaking tour of the country. A trial took place in which Larkin represented himself, presenting his view that his own beliefs rather than his deeds were on trial, and exhibiting a philosophy incorporating his new found Bolshevism as well as his; Christianity, Socialism, Syndicalism, Communism and Irish nationalism. Despite many onlookers being of the opinion that he had gained enough sympathy to divide the jury, instead Larkin's fears were realised and he was found guilty and sentenced to five to ten years, to be served in the notorious Sing Sing

Sing Sing Correctional Facility, formerly Ossining Correctional Facility, is a maximum-security prison operated by the New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision in the village of Ossining, New York. It is about north of ...

prison.

Time in prison

While most of his sentence was served at Sing Sing, Larkin also spent time in other prisons in America, briefly moving to Clinton prison (Dannemora) after only one month at Sing Sing, this move was in order to discourage visitation. A journalist from the

While most of his sentence was served at Sing Sing, Larkin also spent time in other prisons in America, briefly moving to Clinton prison (Dannemora) after only one month at Sing Sing, this move was in order to discourage visitation. A journalist from the New York Call

The ''New York Call'' was a socialism, socialist daily newspaper published in New York City from 1908 through 1923. The ''Call'' was the second of three English-language dailies affiliated with the Socialist Party of America, following the ''Chica ...

managed to gain an interview with Larkin whilst he was incarcerated there, and the reported deterioration of Larkin's condition led to international protests ultimately resulting in him moving back to Sing Sing later that year. Whilst at Sing Sing Larkin was supplied with books and means to write and communicate with the outside world. Keeping a keen eye on Irish affairs, Larkin sent a 'thunderous denunciation of the Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty ( ga , An Conradh Angla-Éireannach), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the ...

to Dublin on 10 December 1921. Larkin's most famous visitor whilst imprisoned was Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin Jr. (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is conside ...

who noted that he was 'diffident' and 'concerned for his family' who he had heard nothing about since his incarceration, Chaplin sent presents to Larkin's wife Elizabeth and their children. Larkin was later moved to Great Meadow

Great Meadow is a field events center and steeplechase course located in The Plains, Virginia. It is operated under the stewardship of the Great Meadow Foundation, a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization dedicated to the preservation of open spac ...

a comfortable open prison where he was visited by Constance Markievicz

Constance Georgine Markievicz ( pl, Markiewicz ; ' Gore-Booth; 4 February 1868 – 15 July 1927), also known as Countess Markievicz and Madame Markievicz, was an Irish politician, revolutionary, nationalist, suffragist, socialist, and the fir ...

who whilst noting his apparent appreciation of his conditions, also sensed his fretfulness at being cut off from politics. On 6 May 1922 Larkin was released before being rearrested shortly afterwards for another charge of criminal anarchy and served with a deportation warrant. Larkin appealed and during his time out of jail he was cabled by Grigory Zinoviev

Grigory Yevseyevich Zinoviev, . Transliterated ''Grigorii Evseevich Zinov'ev'' according to the Library of Congress system. (born Hirsch Apfelbaum, – 25 August 1936), known also under the name Ovsei-Gershon Aronovich Radomyslsky (russian: Ов ...

President of the Communist International

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

(Comintern) who gave their 'warmest greetings to the undaunted fighter released from the "democratic" prisons', in February of that year Larkin had been elected to the Moscow Soviet to represent the Moscow International Communist Tailoring Factory by a union of tailors, most of them returnees to Russia from the USA. Larkin's court appeal failed and he was back in custody by 31 August, despite various plans being discussed, including a potential escape plan raised by Thomas Foran of the ITGWU and numerous legal challenges, Larkin decided to bide his time. During this time it was also arranged for Larkin's son James Jnr to visit his father in prison.

Release and departure from the United States

The election of Irish-American Al Smith

Alfred Emanuel Smith (December 30, 1873 – October 4, 1944) was an American politician who served four terms as Governor of New York and was the Democratic Party's candidate for president in 1928.

The son of an Irish-American mother and a Ci ...

to the position of Governor of New York in November 1922 represented a change in circumstances, and was also a clear indication that the Red Scare had largely abated. Smith granted Larkin a pardon hearing which was set for January 1923, the pardon was granted and he was released from prison. Foran cabled Larkin to convey the ITGWU's satisfaction with the events and to seek the date of his return to Ireland, although Larkin had his mind set on a return to Ireland he had grander plans than a return to union work. The Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

wrote to Larkin on 3 February to express their 'great joy' at his release and to extend an invitation to visit Soviet Russia at his earliest opportunity to 'discuss a number of burning questions affecting the international revolutionary movement'. Larkin made a number of financial requests to the ITGWU, including asking them to cover the costs of purchasing a steamer ship which he, in characteristic fashion, did not reveal the need for. The unions new leadership began to see him as out of touch, and that if allowed to do so he would attempt to restore his previous near total command over the union. The union had also already spent large sums of money on Larkin's behalf; making sure his wife Elizabeth was taken care of, covering his medical expenses and covering the costs of James Jnr's visit to see his father in America, for these reasons the requests for additional financial requests were denied, a decision which begat what would become an intense split of the union movement in Ireland. After lobbying the Secretary for Labor for a deportation order which was granted, he was arrested and charged with being an alien activist, he was then taken to the British consulate where he was given a passport to travel by ship first to the United Kingdom and then to Ireland with. Although Larkin had hoped to have been allowed to travel to; Germany, Austria and Russia on business matters this request was denied. On 21 April he boarded a ship bound for Southampton and left America for good.

Return to Ireland - communist activity and split in Irish trade union movement

Upon his return to Ireland in April 1923, Larkin received a hero's welcome and immediately set about touring the country, meeting trade union members and appealing for an end to the

Upon his return to Ireland in April 1923, Larkin received a hero's welcome and immediately set about touring the country, meeting trade union members and appealing for an end to the Irish Civil War

The Irish Civil War ( ga, Cogadh Cathartha na hÉireann; 28 June 1922 – 24 May 1923) was a conflict that followed the Irish War of Independence and accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free State, an entity independent from the United ...

. However, he soon found himself at variance with William O'Brien, who in his absence had become the leading figure in the ITGWU and the Irish Labour Party and Trades Union Congress. Larkin was still officially general secretary of the ITGWU. The ITGWU leaders (Thomas Foran, William O'Brien, Thomas Kennedy: all colleagues of Larkin during the Lockout) sued him. The bitterness of the court case between the former organisers of the 1913 Lockout would last over 20 years.[

]

Formation of the Irish Worker League and involvement with Soviet Union

Larkin agreed with British and Soviet communists to undertake the leadership of communism in Ireland, and in September 1923 Larkin formed the Irish Worker League

The Irish Worker League was an Irish communist party, established in September 1923 by Jim Larkin, following his return to Ireland. Larkin re-established the newspaper '' The Irish Worker''. The Irish Worker League (IWL) superseded the first ...

(IWL), which was soon afterwards recognised by The Communist International (Comintern; a Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

controlled international organisation that advocated world communism) as the Irish section of the world communist movement. The IWL enrolled 500 members on its inauguration, and following the death of Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

on 21 January 1924 Larkin led a march of 6,000 people to mourn his passing. In March 1924 Larkin lost his battle for control of the ITWGU and in May the army prevented his followers from seizing Liberty Hall

Liberty Hall ( ga, Halla na Saoirse), in Dublin, Ireland, is the headquarters of the Services, Industrial, Professional, and Technical Union (SIPTU). Designed by Desmond Rea O'Kelly, it was completed in 1965. It was for a time the tallest ...

. In June 1924 Larkin attended the Comintern congress in Moscow and was elected to its Executive Committee

A committee or commission is a body of one or more persons subordinate to a deliberative assembly. A committee is not itself considered to be a form of assembly. Usually, the assembly sends matters into a committee as a way to explore them more ...

.

The League's most prominent activity in its first year was to raise funds for imprisoned members of the Anti-Treaty IRA

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty ( ga , An Conradh Angla-Éireannach), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the ...

.

During Larkin absence from Ireland whilst at the 1924 Comintern Congress in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

(and apparently against his instructions), his brother Peter took his supporters out of the ITGWU, forming the Workers' Union of Ireland

The Workers' Union of Ireland (WUI), later the Federated Workers' Union of Ireland, was an Irish trade union formed in 1924. In 1990, it merged with the Irish Transport and General Workers Union to form the Services, Industrial, Professional an ...

(WUI). The new union quickly grew, gaining the allegiance of about two-thirds of the Dublin membership of the ITGWU and of a smaller number of rural members. It was affiliated to the Soviet Red International of Labour Unions

The Red International of Labor Unions (russian: Красный интернационал профсоюзов, translit=Krasnyi internatsional profsoyuzov, RILU), commonly known as the Profintern, was an international body established by the Comm ...

(Promintern).

Larkin sought with Soviet support to remove British unions from Ireland, seeing them as 'outposts of British imperialism', it was also agreed upon that Irish sections of the communist movement would deal directly with Moscow and would have permanent representation there, rather than going through Britain. Larkin later launched a vicious attack on the Tom Johnson who was now leader of the Labour Party and who like Larkin, was Liverpool-born. Johnson had been born to English parents but had spent much of his life in Ireland, Larkin although born to Irish parents had spent as long in the US as he had in Ireland. Larkin said that it was "time that Labour dealt with this English traitor. If they don't get rid of this scoundrel, they'll get the bullet and the bayonet in reward. There's nothing for it, but a dose of the lead which Johnson promises to those who look for work". This implied incitement to murder Johnson in a still-violent post-Civil War country resulted in the court awarding Johnson £1000 in libel damages against Larkin.[ In his 2006 biographical anthology, ]Donal Nevin

Donal Nevin (20 January 1924 – 16 December 2012) was an Irish trade unionist.

Born in Limerick, Nevin was educated at a Christian Brothers school before joining the civil service. His next job, from 1949, was as research officer of the Ir ...

noted that his attacks on colleagues in the labour movement, including those the subject of this libel action, meant that Larkin "alienated practically all the leaders of the movement ndthe mass of trade union members".

In January 1925, the Comintern sent Communist Party of Great Britain

The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) was the largest communist organisation in Britain and was founded in 1920 through a merger of several smaller Marxist groups. Many miners joined the CPGB in the 1926 general strike. In 1930, the CPGB ...

activist Bob Stewart to Ireland to establish a communist party in co-operation with Larkin. A formal founding conference of the Irish Worker League, which was to take up this role, was set for May 1925. A fiasco ensued when the organisers discovered at the last minute that Larkin did not intend to attend. Feeling that the proposed party could not succeed without him, they called the conference off as it was due to start in a packed room in the Mansion House, Dublin

The Mansion House ( ga, Teach an Ard-Mhéara) is a house on Dawson Street, Dublin, which has been the official residence of the Lord Mayor of Dublin since 1715, and was also the meeting place of the Dáil Éireann from 1919 until 1922.

Histor ...

. Larkin perceived certain actions undertaken by Stewart as attempts to circumvent his authority, including sending a republican delegation to Moscow, and directing £500 sent by the Russian Red Cross intended to aid the Irish famine relief effort to George Lansbury

George Lansbury (22 February 1859 – 7 May 1940) was a British politician and social reformer who led the Labour Party from 1932 to 1935. Apart from a brief period of ministerial office during the Labour government of 1929–31, he spe ...

a left-wing British Labour M.P, rather than to the WUI.

Under pressure from Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

to operate as a political party or risk losing affiliation, Larkin fielded three candidates at the September 1927 general election; himself, his son James Larkin Jnr

James Larkin Jnr (20 August 1904 – 18 February 1969) was an Irish Labour Party politician and trade union official.

He was born in Liverpool, England, the eldest of four sons of James Larkin, trade union leader, and Elizabeth Larkin (née ...

, and WUI President John Lawlor. Larkin ran in Dublin North

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ce ...

, and in circumstances that surprised many was elected, becoming the first and only communist to be elected to Dáil Éireann

Dáil Éireann ( , ; ) is the lower house, and principal chamber, of the Oireachtas (Irish legislature), which also includes the President of Ireland and Seanad Éireann (the upper house).Article 15.1.2º of the Constitution of Ireland rea ...

.James Larkin Jnr

James Larkin Jnr (20 August 1904 – 18 February 1969) was an Irish Labour Party politician and trade union official.

He was born in Liverpool, England, the eldest of four sons of James Larkin, trade union leader, and Elizabeth Larkin (née ...

were sent to Moscow to attend the International Lenin School

The International Lenin School (ILS) was an official training school operated in Moscow, Soviet Union, by the Communist International from May 1926 to 1938. It was resumed after the Second World War and run by the Communist Party of the Soviet Uni ...

. In February 1928 Larkin made what would be his penultimate visit to Moscow for the ninth plenum of the Executive Committee of the Communist International