James Harrington (author) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

James Harrington (or Harington) (3 January 1611 – 11 September 1677) was an English

Harrington was born in 1611 in Upton, Northamptonshire, the eldest son of Sir Sapcote(s) Harrington of Rand, Lincolnshire who died in 1630, and his first wife Jane Samwell of Upton, daughter of

Harrington was born in 1611 in Upton, Northamptonshire, the eldest son of Sir Sapcote(s) Harrington of Rand, Lincolnshire who died in 1630, and his first wife Jane Samwell of Upton, daughter of

Knowledge of Harrington's childhood and early education is thin, though he clearly spent time both in Milton Malsor and at the family manor in Rand. In 1629 he entered

Knowledge of Harrington's childhood and early education is thin, though he clearly spent time both in Milton Malsor and at the family manor in Rand. In 1629 he entered

By this time, Harrington's father had died, and his inheritance helped pay his way through several years of continental travel. There is some suggestion that he enlisted in a Dutch militia regiment (apparently seeing no service), before touring the Netherlands, Denmark, Germany, France, Switzerland and Italy. He was in Geneva with James Zouche in the summer of 1635 and subsequently travelled to Rome. In the light of this, Toland's reference to his visiting the Vatican, where he "refused to kiss the Pope's foot", probably refers to early 1636; meanwhile his visit to Venice helped bolster his knowledge of, and enthusiasm for, the Italian republics. The following decade, including his comings and goings during the Civil Wars, are largely unaccounted for by anything other than unsubstantiated stories, for example that he accompanied Charles I to Scotland in 1639 in connection with the first Bishops' War. In 1641–42 and in 1645 he provided financial assistance to Parliament, providing loans and perhaps also collecting money on behalf of Parliament in Lincolnshire. Yet, around the same time, he was acting as 'agent' for Charles Louis, the Prince Elector Palatine, who was nephew of Charles I and whose brother Prince Rupert led the Royalist forces in the

By this time, Harrington's father had died, and his inheritance helped pay his way through several years of continental travel. There is some suggestion that he enlisted in a Dutch militia regiment (apparently seeing no service), before touring the Netherlands, Denmark, Germany, France, Switzerland and Italy. He was in Geneva with James Zouche in the summer of 1635 and subsequently travelled to Rome. In the light of this, Toland's reference to his visiting the Vatican, where he "refused to kiss the Pope's foot", probably refers to early 1636; meanwhile his visit to Venice helped bolster his knowledge of, and enthusiasm for, the Italian republics. The following decade, including his comings and goings during the Civil Wars, are largely unaccounted for by anything other than unsubstantiated stories, for example that he accompanied Charles I to Scotland in 1639 in connection with the first Bishops' War. In 1641–42 and in 1645 he provided financial assistance to Parliament, providing loans and perhaps also collecting money on behalf of Parliament in Lincolnshire. Yet, around the same time, he was acting as 'agent' for Charles Louis, the Prince Elector Palatine, who was nephew of Charles I and whose brother Prince Rupert led the Royalist forces in the

After Charles' death, Harrington probably devoted his time to the composition of ''The Commonwealth of Oceana''. By order of England's then Lord Protector

After Charles' death, Harrington probably devoted his time to the composition of ''The Commonwealth of Oceana''. By order of England's then Lord Protector

political theorist

A political theorist is someone who engages in constructing or evaluating political theory, including political philosophy. Theorists may be Academia, academics or independent scholars. Here the most notable political theorists are categorized b ...

of classical republicanism

Classical republicanism, also known as civic republicanism or civic humanism, is a form of republicanism developed in the Renaissance inspired by the governmental forms and writings of classical antiquity, especially such classical writers as Ar ...

. He is best known for his controversial publication ''The Commonwealth of Oceana

''The Commonwealth of Oceana'' , published 1656, is a work of political philosophy by the English politician and essayist James Harrington (1611–1677). The unsuccessful first attempt to publish ''Oceana'' was officially censored by Lord Prote ...

'' (1656). This work was an exposition of an ideal constitution, a utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book '' Utopia'', describing a fictional island societ ...

, designed to facilitate the development of the English republic established after the regicide, the execution of Charles I in 1649.

Early life

Harrington was born in 1611 in Upton, Northamptonshire, the eldest son of Sir Sapcote(s) Harrington of Rand, Lincolnshire who died in 1630, and his first wife Jane Samwell of Upton, daughter of

Harrington was born in 1611 in Upton, Northamptonshire, the eldest son of Sir Sapcote(s) Harrington of Rand, Lincolnshire who died in 1630, and his first wife Jane Samwell of Upton, daughter of Sir William Samwell

Sir William Samwell (1559–1628) of Northampton and Upton

Upton may refer to:

Places United Kingdom England

* Upton, Slough, Berkshire (in Buckinghamshire until 1974)

* Upton, Buckinghamshire, a hamlet near Aylesbury

* Upton, Cambridgeshire, P ...

. James Harrington was the great-nephew of John Harington, 1st Baron Harington of Exton

John Harington, 1st Baron Harington (1539/40 – 23 August 1613) of Exton in Rutland, was an English courtier and politician.

Family

He was the eldest son and heir of Sir James Harington (c. 1511–1592) of Exton, by his wife Lucy Sidney (c. 1 ...

, who died in 1613. He was for a time a resident, with his father, in the manor house

A manor house was historically the main residence of the lord of the manor. The house formed the administrative centre of a manor in the European feudal system; within its great hall were held the lord's manorial courts, communal meals w ...

at Milton Malsor

Milton Malsor is a village and civil parish in West Northamptonshire, England. The population of the civil parish at the 2011 census was 761. It is south of Northampton town centre, south-east of Birmingham, and north of central London; jun ...

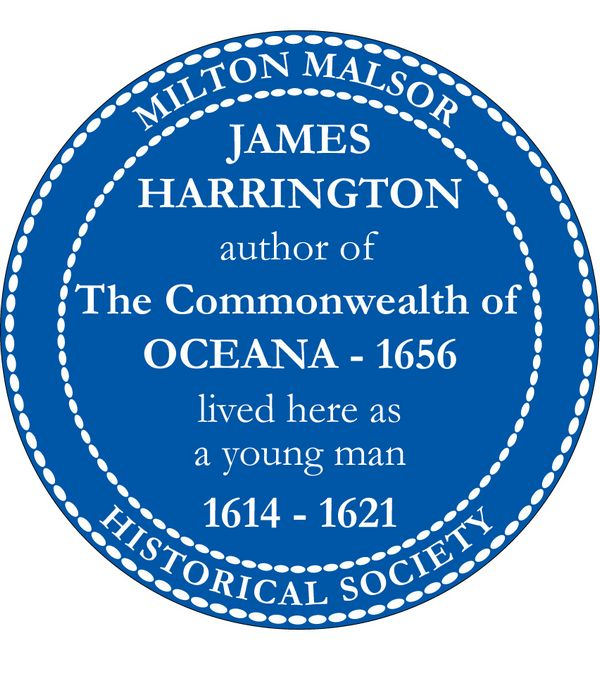

, Northamptonshire, which had been bequeathed by Sir William Samwell to his daughter following her marriage. A blue plaque on Milton Malsor Manor marks this.

Holy Cross Church in Milton Malsor contains a monument on the south wall of the chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may terminate in an apse.

Ov ...

to Harrington's mother, Dame Jane Harrington. According to the memorial, she died on 30 March 1619, when James was 7 or 8 years old. The memorial reads, in modern English but punctuated as in the original:

"Here under lies the body of Dame Jane, daughter of Sir William Samwell Knight, & late wife to Sir Sapcotes Harington of Milton Knight, by whom he had issue 2 sons & 3 daughters, viz James, William, Jane, Anne & Elizabeth. Which Lady died March 30, 1619".When his father died in June 1630, James commissioned a second monument, which can still be seen in the Church of St Oswald at Rand in Lincolnshire. It depicts Sapcotes and his first wife Jane together with their five children.

Childhood and education

Knowledge of Harrington's childhood and early education is thin, though he clearly spent time both in Milton Malsor and at the family manor in Rand. In 1629 he entered

Knowledge of Harrington's childhood and early education is thin, though he clearly spent time both in Milton Malsor and at the family manor in Rand. In 1629 he entered Trinity College, Oxford

(That which you wish to be secret, tell to nobody)

, named_for = The Holy Trinity

, established =

, sister_college = Churchill College, Cambridge

, president = Dame Hilary Boulding

, location = Broad Street, Oxford OX1 3BH

, coordinates ...

as a gentleman commoner

A commoner is a student at certain universities in the British Isles who historically pays for his own tuition and commons, typically contrasted with scholars and exhibitioners, who were given financial emoluments towards their fees.

Cambridge

...

and left two years later with no degree. His eighteenth-century biographer, John Toland, says that while there one of his tutors was the royalist High Churchman William Chillingworth, which may have been the case before the latter left for the Catholic seminary in Douai in 1630. On 27 October 1631 Harrington entered the Middle Temple

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, commonly known simply as Middle Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court exclusively entitled to call their members to the English Bar as barristers, the others being the Inner Temple, Gray's Inn ...

.

Youth

By this time, Harrington's father had died, and his inheritance helped pay his way through several years of continental travel. There is some suggestion that he enlisted in a Dutch militia regiment (apparently seeing no service), before touring the Netherlands, Denmark, Germany, France, Switzerland and Italy. He was in Geneva with James Zouche in the summer of 1635 and subsequently travelled to Rome. In the light of this, Toland's reference to his visiting the Vatican, where he "refused to kiss the Pope's foot", probably refers to early 1636; meanwhile his visit to Venice helped bolster his knowledge of, and enthusiasm for, the Italian republics. The following decade, including his comings and goings during the Civil Wars, are largely unaccounted for by anything other than unsubstantiated stories, for example that he accompanied Charles I to Scotland in 1639 in connection with the first Bishops' War. In 1641–42 and in 1645 he provided financial assistance to Parliament, providing loans and perhaps also collecting money on behalf of Parliament in Lincolnshire. Yet, around the same time, he was acting as 'agent' for Charles Louis, the Prince Elector Palatine, who was nephew of Charles I and whose brother Prince Rupert led the Royalist forces in the

By this time, Harrington's father had died, and his inheritance helped pay his way through several years of continental travel. There is some suggestion that he enlisted in a Dutch militia regiment (apparently seeing no service), before touring the Netherlands, Denmark, Germany, France, Switzerland and Italy. He was in Geneva with James Zouche in the summer of 1635 and subsequently travelled to Rome. In the light of this, Toland's reference to his visiting the Vatican, where he "refused to kiss the Pope's foot", probably refers to early 1636; meanwhile his visit to Venice helped bolster his knowledge of, and enthusiasm for, the Italian republics. The following decade, including his comings and goings during the Civil Wars, are largely unaccounted for by anything other than unsubstantiated stories, for example that he accompanied Charles I to Scotland in 1639 in connection with the first Bishops' War. In 1641–42 and in 1645 he provided financial assistance to Parliament, providing loans and perhaps also collecting money on behalf of Parliament in Lincolnshire. Yet, around the same time, he was acting as 'agent' for Charles Louis, the Prince Elector Palatine, who was nephew of Charles I and whose brother Prince Rupert led the Royalist forces in the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

. Charles Louis and his mother had declared their support for Parliament in 1642.

Harrington's apparent political loyalty to Parliament did not interfere with a strong personal devotion to the King. Following the capture of Charles I, Harrington accompanied a "commission" of MPs appointed to accompany Charles in the move from Newcastle Newcastle usually refers to:

*Newcastle upon Tyne, a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England

*Newcastle-under-Lyme, a town in Staffordshire, England

*Newcastle, New South Wales, a metropolitan area in Australia, named after Newcastle ...

to Holdenby House

Holdenby House is a historic country house in Northamptonshire, traditionally pronounced, and sometimes spelt, Holmby. The house is situated in the parish of Holdenby, six miles (10 km) northwest of Northampton and close to Althorp. It is a ...

(Holmby), after he had been relinquished by the Scots, who had captured him. Harrington's cousin Sir James Harrington was one of the Commissioners, which perhaps explains why the future author of ''Oceana'' was one of those who accompanied the commissioners as servants 'to wait upon' the King on the journey. Harrington continued as 'gentleman of the bedchamber' to the King once they reached Holdenby House, and we see him acting in that capacity through to the end of the year at both Carisbrooke Castle

Carisbrooke Castle is a historic motte-and-bailey castle located in the village of Carisbrooke (near Newport), Isle of Wight, England. Charles I was imprisoned at the castle in the months prior to his trial.

Early history

The site of Carisb ...

and Hurst Castle

Hurst Castle is an artillery fort established by Henry VIII on the Hurst Spit in Hampshire, England, between 1541 and 1544. It formed part of the king's Device Forts coastal protection programme against invasion from France and the Holy Rom ...

. However, while at Hurst Castle Harrington got into a discussion with the Governor and various army officers during which he voiced his support for the King's position concerning the Treaty of Newport, resulting in his dismissal.

At least two contemporary accounts have Harrington with Charles on the scaffold, but these do not rise above the level of rumour.

''Oceana''

After Charles' death, Harrington probably devoted his time to the composition of ''The Commonwealth of Oceana''. By order of England's then Lord Protector

After Charles' death, Harrington probably devoted his time to the composition of ''The Commonwealth of Oceana''. By order of England's then Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three K ...

, it was seized when passing through the press. Harrington, however, managed to secure the favour of Cromwell's favourite daughter, Elizabeth Claypole

Elizabeth Claypolealso ''Cleypole'' and ''Claypoole'' (Noble and Firth DNB) (''née'' Cromwell; 2 July 1629 – 6 August 1658) was the second daughter of Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector of the The Protectorate, Commonwealth of England, Scotlan ...

. The work was restored to him, and appeared in 1656, newly dedicated ''to'' Cromwell. The views embodied in ''Oceana'', particularly those bearing on vote by ballot and rotation of magistrates and legislators, Harrington and others (who in 1659 formed a club called the " Rota") endeavoured to push practically, but with little success.

Editorial history

Harrington's manuscripts have vanished; his printed writings consist of ''Oceana'', and papers, pamphlets, aphorisms and treatises, many of which are devoted to its defence. The first two editions of ''Oceana'' are known as the "Chapman" and the "Pakeman". Their contents are nearly identical. His ''Works'', including the Pakeman ''Oceana'' and a previously unpublished but important manuscript ''A System of Politics'', were first edited with a biography by John Toland in 1700. Toland's edition, with numerous substantial additions byThomas Birch

Thomas Birch (23 November 17059 January 1766) was an English historian.

Life

He was the son of Joseph Birch, a coffee-mill maker, and was born at Clerkenwell.

He preferred study to business but, as his parents were Quakers, he did not go to t ...

, appeared first in London in 1737. An edition not including Birch's additions but rather a copy of Henry Neville's ''Plato'' ''Redivivus'' was published in Dublin in the same year. The 1737 London edition was reprinted in 1747 and 1771. ''Oceana'' was reprinted in Henry ''Morley's Universal Library'' in 1887; S.B. Liljegren reissued a fastidiously prepared version of the Pakeman edition in 1924.

Harrington's modern editor is J. G. A. Pocock. In 1977, he edited a compilation of many of Harrington tracts, with a lengthy historical introduction. According to Pocock, Harrington's prose was marred by an undisciplined work habit and a conspicuous "lack of sophistication," never attaining the level of "a great literary stylist." For example, as contrasted with Hobbes and Milton, "nowhere" to be found are:

"important shades of meaning...conveyed hroughrhythm, emphasis and punctuation; ...He wrote hastily, in a baroque and periodic style in which he more than once lost his way. He suffered from Latinisms...his notions of how to insert quotations, translations and references in his text were at times productive of confusion."By contrast, Rachel Hammersley has argued that Harrington's literary approach was specifically designed to serve his political purposes, to persuade his readers to act on his ideas.

Imprisonment

Following theStuart Restoration

The Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland took place in 1660 when King Charles II returned from exile in continental Europe. The preceding period of the Protectorate and the civil wars came to ...

, on 25 November 1661 Harrington was arrested on a charge of conspiring against the government in the "Bow Street" cabal

A cabal is a group of people who are united in some close design, usually to promote their private views or interests in an ideology, a state, or another community, often by intrigue and usually unbeknownst to those who are outside their group. T ...

and, without a formal trial, was thrown into the Tower. There, he was "badly treated", and in April 1662 a warrant was issued for him to be held in close custody, which led his sisters into obtaining a writ of ''habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, t ...

''. Before it could be executed, however, the authorities rushed him to St Nicholas Island off the coast of Plymouth. His brother and uncle won Harrington's release to the fort at Plymouth by posting a £5000 bond. Thereafter, his general state of health quickly deteriorated, perhaps from his ingestion on medical advice of the addictive drug guaiacum

''Guaiacum'' (''OED'' 2nd edition, 1989.Entry "guaiacum"

in

John Henry Clarke, M.D., ''Dictionary of Practical Materia Medica''

Harrington's mind appeared to be affected. He suffered "intermittent delusions;" one observer judged him "simply mad." He recovered only slightly, then slipped decidedly downhill. He proceeded to suffer attacks of gout and palsy before falling victim to a paralysing stroke. At some point between 1662 and 1669 he married "a Mrs Dayrell, his 'old sweetheart'", the daughter of a Buckinghamshire noble. Harrington died at Little Ambry,

' .

* J.G.A. Pocock, "Editorial and Historical Introductions", ''The Political Works of James Harrington'' (Cambridge: 1977), xi–xviii; 1–152. b: cited as 'Pocock, "Intro"'.

Portions have also been adapted from Pocock, "Intro" and Höpfl, ''ODNB''.

online

*Pocock, The Work of J.G.A. Pocock: ''Harrington section''. * Robbins, Caroline. ''The Eighteenth-Century Commonwealthman: Studies in the Transmission, Development, and Circumstance of English Liberal Thought from the Restoration of Charles II until the War with the Thirteen Colonies'' (1959, 2004). *Russell-Smith, Hugh Francis. ''Harrington and his Oceana; a story of a 17th century Utopia and its influence in America'' (New York: Octagon Books, 1971); . *Scott, Jonathan. "The Rapture of Motion: James Harrington's Republicanism", in Nicholas Phillipson; Quentin Skinner, eds. ''Political Discourse in Early Modern Britain'' (Cambridge: 1993), 139–163; .

Free full-text works of James Harrington online

{{DEFAULTSORT:Harrington, James 1611 births 1677 deaths English political philosophers English republicans People from Upton, Northamptonshire People from West Lindsey District People from West Northamptonshire District People of the English Civil War 17th-century English writers Authors of utopian literature

in

John Henry Clarke, M.D., ''Dictionary of Practical Materia Medica''

Harrington's mind appeared to be affected. He suffered "intermittent delusions;" one observer judged him "simply mad." He recovered only slightly, then slipped decidedly downhill. He proceeded to suffer attacks of gout and palsy before falling victim to a paralysing stroke. At some point between 1662 and 1669 he married "a Mrs Dayrell, his 'old sweetheart'", the daughter of a Buckinghamshire noble. Harrington died at Little Ambry,

Dean's Yard

Dean's Yard, Westminster, comprises most of the remaining precincts of the historically greater scope of the monastery or abbey of Westminster, not occupied by its buildings. It is known to members of Westminster School as Green (referred to ...

, Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

. He was buried next to Sir Walter Raleigh in St Margaret's, Westminster

The Church of St Margaret, Westminster Abbey, is in the grounds of Westminster Abbey on Parliament Square, London, England. It is dedicated to Margaret of Antioch, and forms part of a single World Heritage Site with the Palace of Westminster ...

. There is a slate wall memorial to him at St Michael's Church, Upton.

arrington_has_often_been_confused_with_his_cousin_Sir_James_Harrington,_3rd_Baronet_of_Ridlington,_MP,_a_member_of_the_List_of_regicides_of_Charles_I.html" ;"title="Sir James Harrington, 3rd Baronet of Ridlington">arrington has often been confused with his cousin Sir James Harrington, 3rd Baronet of Ridlington, MP, a member of the List of regicides of Charles I">parliamentary commission which tried Charles I, and twice president of Cromwell's Council of State. He was subsequently excluded from the Indemnity and Oblivion Act which pardoned many who had taken up arms against the King during the Civil Wars (1642–46).]

See also

* Gawthorpe Hall#Portraits, Gawthorpe Hall has a picture of HarringtonNotes

References

* R. Hammersley ''James Harrington: An Intellectual Biography'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019); . * H.M. Höpfl, "Harrington, James", ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', vol. 25, eds. H.C.G. Matthew; Brian Harrison (Oxford: 2004), 386–391. cited as 'Höpfl, ''ODNB''Further reading

*Blitzer, Charles. ''An Immortal Commonwealth: the Political Thought of James Harrington'' (Hamden, Conn.: Archon Books, 1970;1960); . *Cotton, James. ''James Harrington's Political Thought and its Context'' (New York: Garland Pub., 1991); . *Dickinson, W. Calvin. ''James Harrington's Republic'' (Washington, DC: University Press of America, 1983); . *Downs, Michael. ''James Harrington'' (Boston: Twayne Pubs., 1977); . *Hammersley, Rachel. ''James Harrington: An Intellectual Biography'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019); *Pocock, J.G.A. "Interregnum: the ''Oceana'' of James Harrington", chapter 6 in Pocock, ''The Ancient Constitution and the Feudal Law: a Study of English Historical Thought in the Seventeenth Century, a reissue with a retrospect'' (Cambridge: 1987;1957); b: * Pocock, J. G. A. “James Harrington and the Good Old Cause: A Study of the Ideological Context of His Writings.” ''Journal of British Studies' 10#1 1970, pp. 30–48online

*Pocock, The Work of J.G.A. Pocock: ''Harrington section''. * Robbins, Caroline. ''The Eighteenth-Century Commonwealthman: Studies in the Transmission, Development, and Circumstance of English Liberal Thought from the Restoration of Charles II until the War with the Thirteen Colonies'' (1959, 2004). *Russell-Smith, Hugh Francis. ''Harrington and his Oceana; a story of a 17th century Utopia and its influence in America'' (New York: Octagon Books, 1971); . *Scott, Jonathan. "The Rapture of Motion: James Harrington's Republicanism", in Nicholas Phillipson; Quentin Skinner, eds. ''Political Discourse in Early Modern Britain'' (Cambridge: 1993), 139–163; .

External links

* *Free full-text works of James Harrington online

{{DEFAULTSORT:Harrington, James 1611 births 1677 deaths English political philosophers English republicans People from Upton, Northamptonshire People from West Lindsey District People from West Northamptonshire District People of the English Civil War 17th-century English writers Authors of utopian literature