James Fitzjames Stephen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

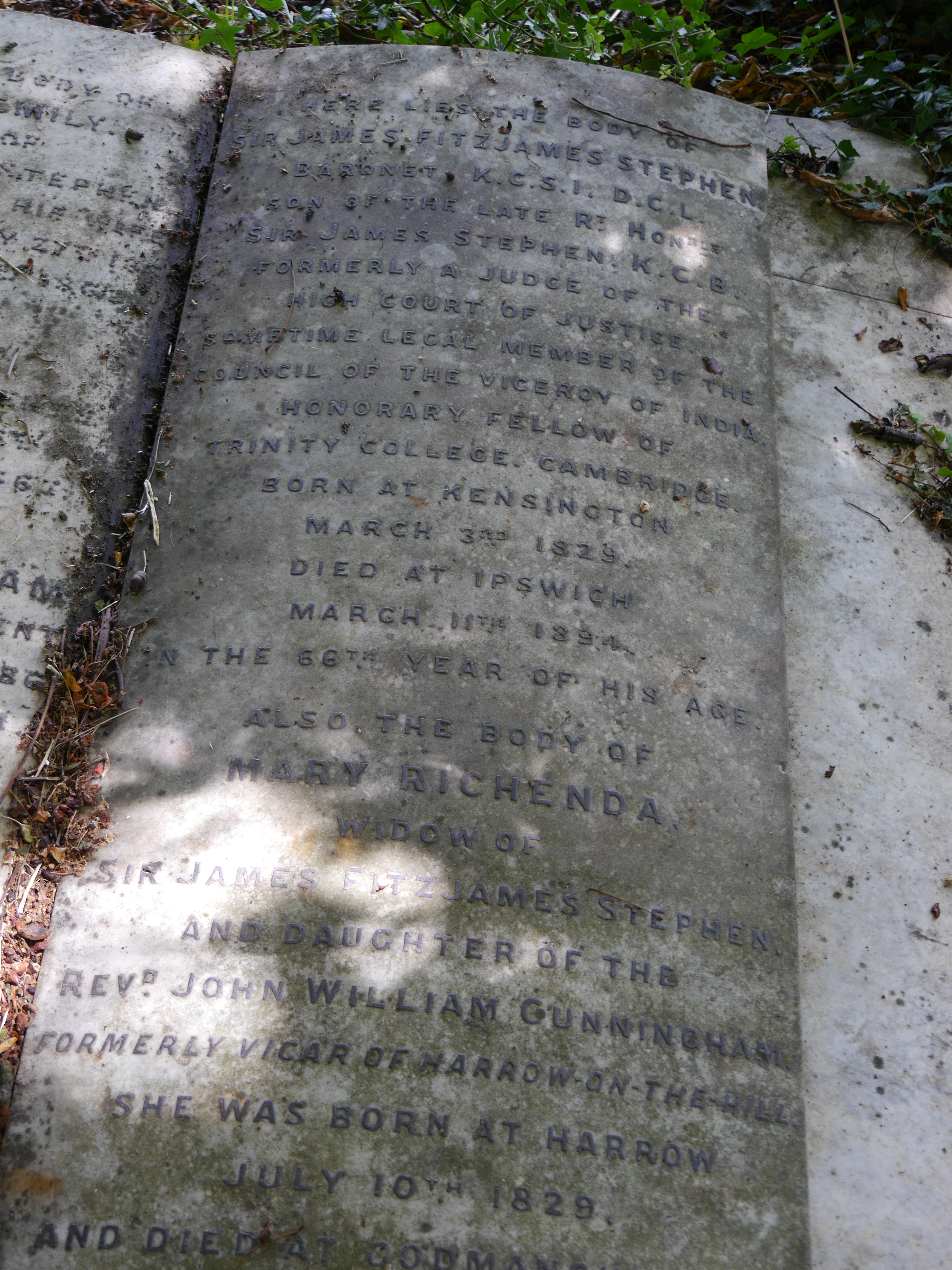

Sir James Fitzjames Stephen, 1st Baronet, KCSI (3 March 1829 – 11 March 1894) was an English lawyer, judge, writer, and philosopher. One of the most famous critics of John Stuart Mill, Stephen achieved prominence as a philosopher, law reformer, and writer.

After leaving Cambridge, Stephen chose to enter a legal career, though his father had hoped for a clerical career. He was called to the bar in January 1854 by the

After leaving Cambridge, Stephen chose to enter a legal career, though his father had hoped for a clerical career. He was called to the bar in January 1854 by the

The decisive point of Stephen's career was in the summer of 1869, when he accepted the post of legal member of the Viceroy's Executive Council in India. His appointment was at the recommendation of his friend Henry Maine, who was his immediate predecessor. He arrived in India in December 1869. During his time in India, Stephen would draft twelve acts and eight other enactments, most of which are still in force.

Guided by Maine's comprehensive talents, the government of India had entered a period of systematic legislation which was to last about twenty years. Stephen had the task of continuing this work by conducting the Bills through the Legislative Council. The Native Marriages Act of 1872 was the result of deep consideration on both Maine's and Stephen's part. The Indian Contract Act had been framed in England by a learned commission, and the draft was materially altered in Stephen's hands before, also in 1872, it became law.

The decisive point of Stephen's career was in the summer of 1869, when he accepted the post of legal member of the Viceroy's Executive Council in India. His appointment was at the recommendation of his friend Henry Maine, who was his immediate predecessor. He arrived in India in December 1869. During his time in India, Stephen would draft twelve acts and eight other enactments, most of which are still in force.

Guided by Maine's comprehensive talents, the government of India had entered a period of systematic legislation which was to last about twenty years. Stephen had the task of continuing this work by conducting the Bills through the Legislative Council. The Native Marriages Act of 1872 was the result of deep consideration on both Maine's and Stephen's part. The Indian Contract Act had been framed in England by a learned commission, and the draft was materially altered in Stephen's hands before, also in 1872, it became law.

After his return from India, Stephen had sought a judgeship for both professional and financial reasons. In 1873, 1877, and 1878, he went on circuit as a commissioner of assize. In 1878, he was considered, but not selected as

After his return from India, Stephen had sought a judgeship for both professional and financial reasons. In 1873, 1877, and 1878, he went on circuit as a commissioner of assize. In 1878, he was considered, but not selected as

Stephen married Mary Richenda Cunningham, daughter of

Stephen married Mary Richenda Cunningham, daughter of

''Essays by a Barrister.''

London: Elder and Co., 1862.

''A General View of the Criminal Law of England.''

London: Macmillan & Co., 1890 (1st Pub. 1863).

''The Indian evidence act (I. of 1872): With an Introduction on the Principles of Judicial Evidence.''

London: Macmillan and Co., 1872.

''Liberty, Equality, Fraternity.''

New York: Holt & Williams, 1873 (2nd ed.

1874

''A History of the Criminal Law of England,''Vol. 2Vol. 3

London: Macmillan & Co., 1883.

''The Story of Nuncomar and the Impeachment of Sir Elijah Impey,''Vol. 2

London: Macmillan and Co., 1885.

''Horae Sabbaticae: Reprint of Articles Contributed to the Saturday Review.''

First Series. London: Macmillan & Co., 1892.

''Horae Sabbaticae: Reprint of Articles Contributed to the Saturday Review.''

Second Series. London: Macmillan & Co., 1892.

''Horae Sabbaticae: Reprint of Articles Contributed to the Saturday Review.''

Third Series. London: Macmillan & Co., 1892.

"Responsibility and Mental Competence,"

''Transactions of the

"Codification in India and England,"

''The Fortnightly Review,'' Vol. XVIII, 1872.

"Parliamentary Government,"Part II

''The Contemporary Review,'' Vol. XXIII, December 1873/May 1874.

"Caesarism and Ultramontanism,"

ref>Cardinal Manning

"Ultramontanism and Christianity,"

''The Contemporary Review,'' Vol. XXIII, December 1873/May 1874.Part II

''The Contemporary Review,'' Vol. XXIII, December 1873/May 1874.

"Necessary Truth,"

''The Contemporary Review,'' Vol. XXV, December 1874/May 1875.

"The Laws of England as to the Expression of Religious Opinion,"

''The Contemporary Review,'' Vol. XXV, December 1874/May 1875.

"Mr. Gladstone and Sir George Lewis on Authority in Matters of Opinion,"

''The Nineteenth Century,'' March/July, 1877.

"Improvement of the Law by Private Enterprise,"

''The Nineteenth Century,'' Vol. II, August/December, 1877.

"Suggestions as to the Reform of the Criminal Law,"

''The Nineteenth Century,'' Vol. II, August/December, 1877.

"The Influence Upon Morality of a Decline in Religious Belief."

In: ''A Modern Symposium,'' Rose-Belford Publishing Co., 1878.

"Gambling and the Law,"

''The Nineteenth Century,'' Vol. XXX, July/December, 1891.

"Criminal Procedure from the Thirteenth to the Eighteenth Century."

In: ''Select Essays in Anglo-American Legal History,'' Vol. II, Little, Brown & Company, 1908.

"Codification in India and England,"

Opening Address of the Session 1872-3 of the Law Amendment Society, ''The Law Magazine'', Vol. I, New Series, 1872.

"Against Theories of Punishment: The Thought of Sir James Fitzjames Stephen,"

''Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law,'' Vol. 9, pp. 1–57. * Kirk, Russell (1952). "The Foreboding Conservatism of Stephen," ''Western Political Quarterly,'' Vol. 5, No. 4, pp. 563–577. * Lipincott, Benjamin (1931). "James Fitzjames Stephen: Critic of Democracy," ''Economica,'' No. 33, pp. 296–307. * Livingston, James C. (1974). "The Religious Creed and Criticism of Sir James Fitzjames Stephen," ''Victorian Studies,'' Vol. 17, No. 3, pp. 279–300. * Morse, Stephen J. (2008)

"Thoroughly Modern: Sir James Fitzjames Stephen on Criminal Responsibility,"

''Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law,'' Vol. 5, pp. 505–522. * Posner, Richard A. (2012)

"The Romance of Force: James Fitzjames Stephen on Criminal Law,"

''Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law,'' Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 263–275. * Roach, John (1956). "James Fitzjames Stephen (1829–94)," ''Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society'' (New Series), Vol. 88, No. 1/2, pp. 1–16. * Smith, K.J.M. (2002). ''James Fitzjames Stephen: Portrait of a Victorian Rationalist.'' Cambridge University Press. * Stapleton, Julia (1998). "James Fitzjames Stephen: Liberalism, Patriotism, and English Liberty," ''Victorian Studies,'' Vol. 41, No. 2, pp. 243–263. * Stephen, Leslie (1895)

''The Life of Sir James Fitzjames Stephen, Bart., K.C.S.I.: A Judge of the High Court of Justice.''

London: Smith, Elder & Co. * Wedgewood, Julia (1909)

"James Fitzjames Stephen."

In: ''Nineteenth Century Teachers and Other Essays.'' London: Hodder & Stoughton, pp. 201–224.

Works by James Fitzjames Stephen

at

Archive of articles by James Fitzjames Stephen in the public domain

* Smith, K.J.M

''"Stephen, Sir James Fitzjames,"''

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press 2004. * {{DEFAULTSORT:Stephen, James Fitzjames 1829 births 1894 deaths Alumni of King's College London Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge Baronets in the Baronetage of the United Kingdom Burials at Kensal Green Cemetery People educated at Eton College Stephen-Bell family English legal writers English male non-fiction writers English King's Counsel Members of the Inner Temple Knights Commander of the Order of the Star of India Queen's Bench Division judges Exchequer Division judges 19th-century English lawyers 19th-century King's Counsel English political philosophers Utilitarians Liberal Party (UK) parliamentary candidates Members of the Council of the Governor General of India

Early life and education, 1829–1854

James Fitzjames Stephen was born on 3 March 1829 at Kensington Gore,London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, the third child and second son of Sir James Stephen and Jane Catherine Venn. Stephen came from a distinguished family. His father, the drafter of the Slavery Abolition Act 1833

The Slavery Abolition Act 1833 (3 & 4 Will. IV c. 73) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which provided for the gradual abolition of slavery in most parts of the British Empire. It was passed by Earl Grey's reforming administrat ...

, was Permanent Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies

Permanent may refer to:

Art and entertainment

* ''Permanent'' (film), a 2017 American film

* ''Permanent'' (Joy Division album)

* "Permanent" (song), by David Cook

Other uses

*Permanent (mathematics), a concept in linear algebra

*Permanent (cycl ...

and Regius Professor of Modern History at Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a College town, university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cam ...

. His grand-father James Stephen and uncle George Stephen were both leading anti-slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

campaigners. His younger brother was the author and critic Sir Leslie Stephen, whilst his younger sister Caroline Stephen

Caroline Emelia Stephen (8 December 1834 – 7 April 1909), also known as Milly Stephen, was a British philanthropist and a writer on Quakerism. Her niece was Virginia Woolf.

Life

Stephen was born on 8 December 1834 at Kensington Gore on Hyde P ...

was a philanthropist and a writer on Quakerism. Through his brother Leslie Stephen, he was the uncle of Virginia Woolf

Adeline Virginia Woolf (; ; 25 January 1882 28 March 1941) was an English writer, considered one of the most important modernist 20th-century authors and a pioneer in the use of stream of consciousness as a narrative device.

Woolf was born i ...

, He was also a cousin of the jurist A.V. Dicey.

Stephen was first educated at the Reverend Benjamin Guest's school in Brighton from the age of seven, before spending three years at Eton College

Eton College () is a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. intended as a sister institution to King's College, ...

from 1842. Strongly disliking Eton, Stephen completed his pre-university education by attending King's College, London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public university, public research university located in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of George IV of the United Kingdom, King G ...

for two years.

In October 1847 he entered Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any college at either Cambridge or Oxford. ...

. Although an outstanding intellect, he took an undistinguished BA in Classics in 1851, being, in his own words, one of the "most unteachable of human beings". He was, however, well-known as a strong debater at the Cambridge Union

The Cambridge Union Society, also known as the Cambridge Union, is a debating and free speech society in Cambridge, England, and the largest society in the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1815, it is the oldest continuously running debati ...

. He was also elected to the exclusive Cambridge Apostles

The Cambridge Apostles (also known as ''Conversazione Society'') is an intellectual society at the University of Cambridge founded in 1820 by George Tomlinson, a Cambridge student who became the first Bishop of Gibraltar.W. C. Lubenow, ''The Ca ...

, his proposer being Henry Maine, the newly-appointed Regius Professor of Civil Law, who became a lifelong friend despite their differing temperaments. At Apostles meetings, he frequently sparred with William Harcourt, later leader of the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

, in debates described by contemporaries as "veritable battles of the gods". Another Apostles contemporary was the physicist James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish mathematician and scientist responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism and li ...

.

Being conscious of the slightness of his legal education, he then read for an LL.B. from the University of London. This was an unusual step for its day, and it was there that he first seriously engaged with the works of Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

.

Early career, 1854–1869

After leaving Cambridge, Stephen chose to enter a legal career, though his father had hoped for a clerical career. He was called to the bar in January 1854 by the

After leaving Cambridge, Stephen chose to enter a legal career, though his father had hoped for a clerical career. He was called to the bar in January 1854 by the Inner Temple

The Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, commonly known as the Inner Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court and is a professional associations for barristers and judges. To be called to the Bar and practise as a barrister in England and ...

, and joined the Midland Circuit. His own estimation of his professional success—written in later years—was that in spite of such training rather than because of it, he became a moderately successful advocate and a rather distinguished judge.

In his earlier years at the bar he supplemented his income from a successful but modest practice with journalism. He contributed to the '' Saturday Review'' from the time it was founded in 1855. He was in company with Maine, Harcourt, G.S. Venables, Charles Bowen, E.A. Freeman, Goldwin Smith and others. Both the first and the last books published by Stephen were selections from his papers in the ''Saturday Review'' (''Essays by a Barrister'', 1862, anonymous; ''Horae sabbaticae'', 1892). These volumes embodied the results of his studies of publicists and theologians

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the s ...

, chiefly English, from the 17th century onwards. He never professed his essays to be more than the occasional products of an amateur's leisure, but they were well received.

From 1858 to 1861, Stephen served as secretary to a Royal Commission on popular education, whose conclusions were promptly put into effect. In 1859 he was appointed Recorder of Newark. In 1863 he published his ''General View of the Criminal Law of England'', the first attempt made since William Blackstone

Sir William Blackstone (10 July 1723 – 14 February 1780) was an English jurist, judge and Tory politician of the eighteenth century. He is most noted for writing the ''Commentaries on the Laws of England''. Born into a middle-class family ...

to explain the principles of English law and justice in a literary form, and it enjoyed considerable success. The foundation of the ''Pall Mall Gazette

''The Pall Mall Gazette'' was an evening newspaper founded in London on 7 February 1865 by George Murray Smith; its first editor was Frederick Greenwood. In 1921, '' The Globe'' merged into ''The Pall Mall Gazette'', which itself was absorbed in ...

'' in 1865 gave Stephen a new literary avenue. He continued to contribute until he became a judge.

Stephen's practice at the Bar was an uneven one, though he appeared in two notable cases. In 1861–62, he unsuccessfully defended the Reverend Rowland Williams in the Court of Arches against charges of heresy, though he was ultimately acquitted in the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council

The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) is the highest court of appeal for the Crown Dependencies, the British Overseas Territories, some Commonwealth countries and a few institutions in the United Kingdom. Established on 14 Aug ...

. In 1865–66, Stephen was retained (along with Edward James

Edward Frank Willis James (16 August 1907 – 2 December 1984) was a British poet known for his patronage of the surrealist art movement.

Early life and marriage

James was born on 16 August 1907, the only son of William James (who had inherite ...

QC) by the Jamaica Committee, which sought to prosecute Edward Eyre, Governor of Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

, for his excesses in suppressing the Morant Bay rebellion of 1865. They produced a legal opinion, which charged Eyre and his officers with serious breaches of English criminal law, some of them capital.

In early 1867, Stephen was retained by the Jamaica Committee to prosecute Alexander Abercromby Nelson and Herbert Brand, two military officers who had sat on the court martial which sentenced George William Gordon

George William Gordon (1820 – 23 October 1865) was a wealthy mixed-race Jamaican businessman, magistrate and politician, one of two representatives to the Assembly from St. Thomas-in-the-East parish. He was a leading critic of the colonia ...

to death; but the grand jury declined to return a true bill

True most commonly refers to truth, the state of being in congruence with fact or reality.

True may also refer to:

Places

* True, West Virginia, an unincorporated community in the United States

* True, Wisconsin, a town in the United States

* ...

. He was then retained to prosecute Eyre: when he began his case, Stephen surprised observers by praising Eyre as a courageous man who had acted honourably in an emergency. Eyre was discharged and Stephen fell out with the Jamaica Committee. His friendship with John Stuart Mill, who was a leading member of the Committee, was permanently damaged. Stephen was a critic of Mill's "sentimental liberalism", arguing that the British government was justified in applying force to prevent subject societies from descending into anarchy.

Meanwhile, Stephen's legal career proceeded apace, and in 1868, he became a Queen's Counsel

In the United Kingdom and in some Commonwealth countries, a King's Counsel (post-nominal initials KC) during the reign of a king, or Queen's Counsel (post-nominal initials QC) during the reign of a queen, is a lawyer (usually a barrister o ...

, one of fifteen that year. However, he suffered a setback in January 1869, when he was passed over for the Whewell Professorship of International Law

The Whewell Professorship of International Law is a professorship in the University of Cambridge.

The Professorship was established in 1868 by the will of the 19th-century scientist and moral philosopher, William Whewell, with a view to devising ...

in favour of his old rival William Harcourt.

Stephen in India, 1869–1872

The decisive point of Stephen's career was in the summer of 1869, when he accepted the post of legal member of the Viceroy's Executive Council in India. His appointment was at the recommendation of his friend Henry Maine, who was his immediate predecessor. He arrived in India in December 1869. During his time in India, Stephen would draft twelve acts and eight other enactments, most of which are still in force.

Guided by Maine's comprehensive talents, the government of India had entered a period of systematic legislation which was to last about twenty years. Stephen had the task of continuing this work by conducting the Bills through the Legislative Council. The Native Marriages Act of 1872 was the result of deep consideration on both Maine's and Stephen's part. The Indian Contract Act had been framed in England by a learned commission, and the draft was materially altered in Stephen's hands before, also in 1872, it became law.

The decisive point of Stephen's career was in the summer of 1869, when he accepted the post of legal member of the Viceroy's Executive Council in India. His appointment was at the recommendation of his friend Henry Maine, who was his immediate predecessor. He arrived in India in December 1869. During his time in India, Stephen would draft twelve acts and eight other enactments, most of which are still in force.

Guided by Maine's comprehensive talents, the government of India had entered a period of systematic legislation which was to last about twenty years. Stephen had the task of continuing this work by conducting the Bills through the Legislative Council. The Native Marriages Act of 1872 was the result of deep consideration on both Maine's and Stephen's part. The Indian Contract Act had been framed in England by a learned commission, and the draft was materially altered in Stephen's hands before, also in 1872, it became law.

Indian Evidence Act

The Indian Evidence Act of the same year, entirely Stephen's own work, made the rules of evidence uniform for all residents of India, regardless of caste, social position, or religion. Besides drafting legislation, at this time Stephen had to attend to the current administrative business of his department, and he took a full share in the general deliberations of the viceroy's council. His last official act in India was the publication of a minute on the administration of justice which pointed the way to reforms not yet fully realized, and is still a valuable tool for anyone wishing to understand the judicial system ofBritish India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

.

Return to England, 1872–1879

Stephen, mainly for family reasons, returned to England in the spring of 1872. During the voyage he wrote a series of articles which resulted in his book ''Liberty, Equality, Fraternity'' (1873–1874)--a protest against John Stuart Mill's neo-utilitarianism

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different chara ...

. Around this time, Leslie Stephen noted the influence of Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, Dum ...

on his brother's thought. This showed in Stephen's famous attack on the thesis of John Stuart Mill's essay ''On Liberty

''On Liberty'' is a philosophical essay by the English philosopher John Stuart Mill. Published in 1859, it applies Mill's ethical system of utilitarianism to society and state. Mill suggests standards for the relationship between authority a ...

'', arguing for legal compulsion, coercion and restraint in the interests of morality and religion. Stephen argued, "Force is an absolutely essential element of all law whatever."

Fitzjames Stephen stood in an 1873 by-election as a Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

for Dundee, but came in last place. The same year, he was elected to the Metaphysical Society

The Metaphysical Society was a famous British debating society, founded in 1869 by James Knowles, who acted as Secretary. Membership was by invitation only, and was exclusively male. Many of its members were prominent clergymen, philosophers, and ...

; he gave seven papers to the Society, making him one of its most active members. In 1875, he was appointed Professor of Common Law at the Inns of Court

The Inns of Court in London are the professional associations for barristers in England and Wales. There are four Inns of Court – Gray's Inn, Lincoln's Inn, Inner Temple and Middle Temple.

All barristers must belong to one of them. They have ...

. He also sat on government commissions on fugitive slaves (1876), extradition (1878), and copyright (1878). He also appeared irregularly as counsel in the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council

The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) is the highest court of appeal for the Crown Dependencies, the British Overseas Territories, some Commonwealth countries and a few institutions in the United Kingdom. Established on 14 Aug ...

.

Experience in India gave Stephen opportunity for his next activity. The government of India had been driven by the conditions of the Indian judicial system to recast a considerable part of the English law which had been informally imported. Criminal law procedure, and a good deal of commercial law, had been or were being put into easily understood language, intelligible to civilian magistrates. The rational substance of the law was preserved, while disorder and excessive technicalities were removed. Using Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

's ideal of codification, he attempted to get the same principles put into practice in the United Kingdom. As a preparatory step, Stephen also privately published digests in code form of the law of evidence

The law of evidence, also known as the rules of evidence, encompasses the rules and legal principles that govern the proof of facts in a legal proceeding. These rules determine what evidence must or must not be considered by the trier of f ...

(1876) and criminal law (1877).

In August 1877, Stephen's proposals were taken up by the government and he was asked to draft a criminal code for England. He completed his draft in early 1878 and it was debated in Parliament, after which it was referred to a Royal Commission under the chairmanship of Lord Blackburn, with Stephen as a member. In 1879, the Commission produced a draft bill, which received opposition from many quarters. It did, however, serve as the basis of the criminal codes of many parts of the British Empire, including those of Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

Judicial career and final years, 1879–1894

After his return from India, Stephen had sought a judgeship for both professional and financial reasons. In 1873, 1877, and 1878, he went on circuit as a commissioner of assize. In 1878, he was considered, but not selected as

After his return from India, Stephen had sought a judgeship for both professional and financial reasons. In 1873, 1877, and 1878, he went on circuit as a commissioner of assize. In 1878, he was considered, but not selected as Recorder of London

The Recorder of London is an ancient legal office in the City of London. The Recorder of London is the senior circuit judge at the Central Criminal Court (the Old Bailey), hearing trials of criminal offences. The Recorder is appointed by the Cr ...

in succession to Russell Gurney. In 1873, he had also been proposed as Solicitor-General by Sir John Coleridge, the Attorney-General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

, though Sir Henry James was chosen instead.

When Stephen was charged with the preparation of the English criminal code, he was virtually promised a judgeship, though no explicit promise could be made. Finally, in January 1879, Stephen was appointed a Justice of the High Court, in succession to Sir Anthony Cleasby. He was initially assigned to the Exchequer Division. When that division was merged into the Queen's Bench Division in 1881, Stephen was transferred to the latter, where he remained until his retirement. Occupied with the preparation of the criminal code, he only made his first appearance as a judge in April 1879 at the Old Bailey, when he passed a death sentence against a matricide.

Distracted by his literary and intellectual pursuits, his time as a judge was unimpressive relative to the rest of his career, though his judgments were of a high quality. He had transient hopes of an Evidence Act being brought before Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

, and in 1878 the Digest of Criminal Law became a Ministerial Bill with the cooperation of Sir John Holker, who was Attorney-General in the second government of Benjamin Disraeli. The Bill was referred to a judicial commission, which included Stephen, but ultimately failed, and was revised and reintroduced in 1879 and again in 1880. It dealt with procedure as well as substantive law, and provided for a court of criminal appeal, though after several years of judicial experience Stephen changed his mind as to the wisdom of this course. However, no substantial progress was made during any sessions of Parliament. In 1883 the part relating to procedure was brought in separately by Gladstone's law officer Sir Henry James, and went to the grand committee on law, which found that there was insufficient time to deal with it satisfactorily in the course of the session.

Stephen's final years were undermined first by physical and then steady mental decline. In 1885, he had his first stroke. Despite accusations of unfairness and bias regarding the murder trials of Israel Lipski in 1887 and Florence Maybrick in 1889, Stephen continued performing his judicial duties. However, by early 1891 his declining capacity to exercise judicial functions had become a matter of public discussion and press comment, and following medical advice Stephen resigned in April of that year, whereupon he was made a baronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14t ...

. Even during his final days on the bench, Stephen is reported to have been 'brief, terse and to the point, and as lucid as in the old days'. Having lost his intellectual power, however, 'as the hours wore on his voice dropped almost to a whisper'.

Stephen died of chronic renal failure on 11 March 1894 at Red House Park, a nursing home near Ipswich

Ipswich () is a port town and borough in Suffolk, England, of which it is the county town. The town is located in East Anglia about away from the mouth of the River Orwell and the North Sea. Ipswich is both on the Great Eastern Main Line ...

, and was buried at Kensal Green Cemetery

Kensal Green Cemetery is a cemetery in the Kensal Green area of Queens Park in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in London, England. Inspired by Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, it was founded by the barrister George Frederick ...

, London. His wife survived him.

Honours

Stephen was knighted as aKnight Commander of the Order of the Star of India

The Most Exalted Order of the Star of India is an order of chivalry founded by Queen Victoria in 1861. The Order includes members of three classes:

# Knight Grand Commander (GCSI)

# Knight Commander ( KCSI)

# Companion ( CSI)

No appointments ...

(KCSI) in January 1877. He was created a Baronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14t ...

, of De Vere Gardens

De Vere Gardens is a street in Kensington, London, that in 2015 was considered the fifth most expensive street in England.

Location

The street runs roughly north to south, from Kensington Road to Canning Place, and parallel to Victoria Road, Ken ...

in the parish of Saint Mary Abbott, Kensington, in the County of London, on 29 June 1891, shortly after his resignation from the bench. He was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, a ...

, a corresponding member of the Institut de France

The (; ) is a French learned society, grouping five , including the Académie Française. It was established in 1795 at the direction of the National Convention. Located on the Quai de Conti in the 6th arrondissement of Paris, the institute ...

(1888). He received honorary doctorates from the University of Oxford (1878) and the University of Edinburgh University (1884), and was elected an honorary fellowship of Trinity College, Cambridge (1885).

Legacy

Criminal appeal was discussed and an Act passed in 1907; otherwise nothing has been done in the UK with either part of the draft code since. The historical materials which Stephen had long been collecting took permanent shape in 1883 as his ''History of the Criminal Law of England''. He lacked time for a planned ''Digest of the Law of Contract'' (which would have been much fuller than the Indian Code). Thus none of Stephen's own plans of English codification took effect. The Parliament of Canada used a version of Stephen's Draft Bill revised and augmented byGeorge Burbidge

George Wheelock Burbidge (6 February 1847 – 18 February 1908) was a Canadian lawyer, judge and author. After being called to the bar of New Brunswick in 1872, he became a partner in the Saint John, New Brunswick law firm of Harrison and Burbidge. ...

, at the time Judge of the Exchequer Court of Canada, to codify its criminal law in 1892 as the ''Criminal Code, 1892''. New Zealand followed with the ''New Zealand Criminal Code Act 1893'' and a number of Australian colonies adopted their own versions as Criminal Codes in following years

His book ''Liberty, Equality, Fraternity'' was called the "finest exposition of conservative thought in the latter half of the 19th century" by Ernest Barker. It was listed as one of Ten Conservative Books to read in the chapter of that name in ''The Politics of Prudence'' by Russell Kirk

Russell Amos Kirk (October 19, 1918 – April 29, 1994) was an American political theorist, moralist, historian, social critic, and literary critic, known for his influence on 20th-century American conservatism. His 1953 book ''The Conservativ ...

. According to Princeton University political theorist Greg Conti, Stephen's political thought had liberal characteristics, even though he has frequently been characterized as conservative or religious authoritarian. According to Conti, Stephen "articulated robustly both technocratic and pluralistic visions of politics. Perhaps more stridently than any Victorian, he put forward an argument for the necessity and legitimacy of expert rule against claims for popular government. Yet he also insisted on the plurality of perspectives on public affairs and on the ineluctable conflict between them."

The 1957 Wolfenden report

The Report of the Departmental Committee on Homosexual Offences and Prostitution (better known as the Wolfenden report, after Sir John Wolfenden, the chairman of the committee) was published in the United Kingdom on 4 September 1957 after a suc ...

recommended the decriminalisation of homosexuality and this sparked off the Hart

Hart often refers to:

* Hart (deer)

Hart may also refer to:

Organizations

* Hart Racing Engines, a former Formula One engine manufacturer

* Hart Skis, US ski manufacturer

* Hart Stores, a Canadian chain of department stores

* Hart's Reptile Wo ...

- Devlin debate on the relationship between politics and morals. Lord Devlin's 1959 critique of the Wolfenden report (titled 'The Enforcement of Morals') resembled Stephen's arguments, although Devlin had arrived at his opinions independently, having never read ''Liberty, Equality, Fraternity''.John Heydon, 'Reflections on James Fitzjames Stephen', ''University of Queensland Law Journal'', 29, no. 1 (2010), p. 49. Hart claimed that "though a century divides these two legal writers, the similarity in the general tone and sometimes in the detail of their arguments is very great".H. L. A. Hart, ''Law, Liberty and Morality'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1963), p. 16. Afterwards, Devlin tried to obtain a copy of ''Liberty, Equality, Fraternity'' from his local library but could only do so with "great difficulty"; the copy, when it arrived, was "held together with an elastic band". Hart, an opponent of Stephen's views, regarded ''Liberty, Equality, Fraternity'' as "sombre and impressive".

An eleven-volume set of his collected writings is currently being prepared for Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print books ...

by the Editorial Institute at Boston University

Boston University (BU) is a Private university, private research university in Boston, Massachusetts. The university is nonsectarian, but has a historical affiliation with the United Methodist Church. It was founded in 1839 by Methodists with ...

.

Personal life

John William Cunningham

John William Cunningham (1780–1861) was an evangelical clergyman of the Church of England. He was known also as a writer and an editor.

Life

Cunningham was born in London on 3 January 1780. He was educated at private schools, his last tutor bei ...

, on 19 September 1855. They had three sons and at least four daughters surviving to adulthood, but only one grandchild:

* Katharine Stephen

Katharine Stephen (26 February 1856 – 16 June 1924) was a librarian and later principal of Newnham College at Cambridge University.

Early life and family

Katharine Stephen was born in London on 26 February 1856, the daughter of Mary Richend ...

(1856–1924), librarian and Principal of Newnham College, Cambridge

Newnham College is a women's constituent college of the University of Cambridge.

The college was founded in 1871 by a group organising Lectures for Ladies, members of which included philosopher Henry Sidgwick and suffragist campaigner Millicen ...

;

* Sir Herbert Stephen, 2nd Baronet (1857–1932), barrister and clerk of assize, who succeeded him in the baronetcy;

* James Kenneth Stephen (1859-1892), poet and tutor to Prince Albert Victor, who predeceased his father;

* Sir Harry Lushington Stephen, 3rd Baronet (1860–1945), Judge of the High Court of Calcutta

The Calcutta High Court is the oldest High Court in India. It is located in B.B.D. Bagh, Kolkata, West Bengal. It has jurisdiction over the state of West Bengal and the Union Territory of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. The High Court build ...

, 1901–1914, who succeeded his eldest brother as the 3rd baronet;

* Helen Stephen (1862–1908);

* Rosamond Emily Stephen (1868–1951), lay missionary in the Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the secon ...

in Belfast and advocate of ecumenism;

* Dorothea Jane Stephen (1871–1965), teacher of religion in India.

Quotations

Oncapital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

:

"Some men, probably, abstain from murder because they fear that, if they committed murder, they would be hung. Hundreds of thousands abstain from it because they regard it with horror. One great reason why they regard it with horror is, that murderers are hung with the hearty approbation of all reasonable men".On evidence obtained by

duress

Coercion () is compelling a party to act in an involuntary manner by the use of threats, including threats to use force against a party. It involves a set of forceful actions which violate the free will of an individual in order to induce a desi ...

or torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons such as punishment, extracting a confession, interrogational torture, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties. definitions of tortur ...

:"It is far pleasanter to sit comfortably in the shade rubbing red pepper in some poor devil's eyes, than to go about in the sun hunting up evidence."Source: The

University of Chicago Law Review

The ''University of Chicago Law Review'' (Maroonbook abbreviation: ''U Chi L Rev'') is the flagship law journal published by the University of Chicago Law School. It is among the top five most cited law reviews in the world. Up until 2020, it utili ...

, Vol. 46, No. 1 (Autumn, 1978), pp. 3–22 40 1 J.F. STEPHEN, A HISTORY OF THE CRIMINAL LAW OF ENGLAND 442 n.1 (1883). Stephen's forceful quotation has been cited for this point elsewhere; McNabb v. United States, 318 U.S. 332, 344 n.8 (1943); J. LANGBEIN, supra note 1, at 147 n.14; Alschuler, supra note 11, at 1103 n.137.

Arms

Works

''Essays by a Barrister.''

London: Elder and Co., 1862.

''A General View of the Criminal Law of England.''

London: Macmillan & Co., 1890 (1st Pub. 1863).

''The Indian evidence act (I. of 1872): With an Introduction on the Principles of Judicial Evidence.''

London: Macmillan and Co., 1872.

''Liberty, Equality, Fraternity.''

New York: Holt & Williams, 1873 (2nd ed.

1874

''A History of the Criminal Law of England,''

London: Macmillan & Co., 1883.

''The Story of Nuncomar and the Impeachment of Sir Elijah Impey,''

London: Macmillan and Co., 1885.

''Horae Sabbaticae: Reprint of Articles Contributed to the Saturday Review.''

First Series. London: Macmillan & Co., 1892.

''Horae Sabbaticae: Reprint of Articles Contributed to the Saturday Review.''

Second Series. London: Macmillan & Co., 1892.

''Horae Sabbaticae: Reprint of Articles Contributed to the Saturday Review.''

Third Series. London: Macmillan & Co., 1892.

Selected articles

"Responsibility and Mental Competence,"

''Transactions of the

National Association for the Promotion of Social Science

The National Association for the Promotion of Social Science (NAPSS), often known as the Social Science Association, was a British reformist group founded in 1857 by Lord Brougham. It pursued issues in public health, industrial relations, penal r ...

,'' 1865.

"Codification in India and England,"

''The Fortnightly Review,'' Vol. XVIII, 1872.

"Parliamentary Government,"

''The Contemporary Review,'' Vol. XXIII, December 1873/May 1874.

"Caesarism and Ultramontanism,"

ref>Cardinal Manning

"Ultramontanism and Christianity,"

''The Contemporary Review,'' Vol. XXIII, December 1873/May 1874.Part II

''The Contemporary Review,'' Vol. XXIII, December 1873/May 1874.

"Necessary Truth,"

''The Contemporary Review,'' Vol. XXV, December 1874/May 1875.

"The Laws of England as to the Expression of Religious Opinion,"

''The Contemporary Review,'' Vol. XXV, December 1874/May 1875.

"Mr. Gladstone and Sir George Lewis on Authority in Matters of Opinion,"

''The Nineteenth Century,'' March/July, 1877.

"Improvement of the Law by Private Enterprise,"

''The Nineteenth Century,'' Vol. II, August/December, 1877.

"Suggestions as to the Reform of the Criminal Law,"

''The Nineteenth Century,'' Vol. II, August/December, 1877.

"The Influence Upon Morality of a Decline in Religious Belief."

In: ''A Modern Symposium,'' Rose-Belford Publishing Co., 1878.

"Gambling and the Law,"

''The Nineteenth Century,'' Vol. XXX, July/December, 1891.

"Criminal Procedure from the Thirteenth to the Eighteenth Century."

In: ''Select Essays in Anglo-American Legal History,'' Vol. II, Little, Brown & Company, 1908.

Miscellany

"Codification in India and England,"

Opening Address of the Session 1872-3 of the Law Amendment Society, ''The Law Magazine'', Vol. I, New Series, 1872.

References

*Further reading

* Annan, Noel (1955). "The Intellectual Aristocracy." In J.H. Plumb (ed.), ''Studies in Social History: A Tribute to G. M. Trevelyan.'' London: Longmans, Green. * Colaiaco, James A. (1983). ''James Fitzjames Stephen and the Crisis of Victorian Thought.'' London: Macmillan. * DeGirolami, Marc O. (2012)"Against Theories of Punishment: The Thought of Sir James Fitzjames Stephen,"

''Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law,'' Vol. 9, pp. 1–57. * Kirk, Russell (1952). "The Foreboding Conservatism of Stephen," ''Western Political Quarterly,'' Vol. 5, No. 4, pp. 563–577. * Lipincott, Benjamin (1931). "James Fitzjames Stephen: Critic of Democracy," ''Economica,'' No. 33, pp. 296–307. * Livingston, James C. (1974). "The Religious Creed and Criticism of Sir James Fitzjames Stephen," ''Victorian Studies,'' Vol. 17, No. 3, pp. 279–300. * Morse, Stephen J. (2008)

"Thoroughly Modern: Sir James Fitzjames Stephen on Criminal Responsibility,"

''Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law,'' Vol. 5, pp. 505–522. * Posner, Richard A. (2012)

"The Romance of Force: James Fitzjames Stephen on Criminal Law,"

''Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law,'' Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 263–275. * Roach, John (1956). "James Fitzjames Stephen (1829–94)," ''Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society'' (New Series), Vol. 88, No. 1/2, pp. 1–16. * Smith, K.J.M. (2002). ''James Fitzjames Stephen: Portrait of a Victorian Rationalist.'' Cambridge University Press. * Stapleton, Julia (1998). "James Fitzjames Stephen: Liberalism, Patriotism, and English Liberty," ''Victorian Studies,'' Vol. 41, No. 2, pp. 243–263. * Stephen, Leslie (1895)

''The Life of Sir James Fitzjames Stephen, Bart., K.C.S.I.: A Judge of the High Court of Justice.''

London: Smith, Elder & Co. * Wedgewood, Julia (1909)

"James Fitzjames Stephen."

In: ''Nineteenth Century Teachers and Other Essays.'' London: Hodder & Stoughton, pp. 201–224.

External links

*Works by James Fitzjames Stephen

at

Hathi Trust

HathiTrust Digital Library is a large-scale collaborative repository of digital content from research libraries including content digitized via Google Books and the Internet Archive digitization initiatives, as well as content digitized locally ...

Archive of articles by James Fitzjames Stephen in the public domain

* Smith, K.J.M

''"Stephen, Sir James Fitzjames,"''

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press 2004. * {{DEFAULTSORT:Stephen, James Fitzjames 1829 births 1894 deaths Alumni of King's College London Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge Baronets in the Baronetage of the United Kingdom Burials at Kensal Green Cemetery People educated at Eton College Stephen-Bell family English legal writers English male non-fiction writers English King's Counsel Members of the Inner Temple Knights Commander of the Order of the Star of India Queen's Bench Division judges Exchequer Division judges 19th-century English lawyers 19th-century King's Counsel English political philosophers Utilitarians Liberal Party (UK) parliamentary candidates Members of the Council of the Governor General of India