James Brooke on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

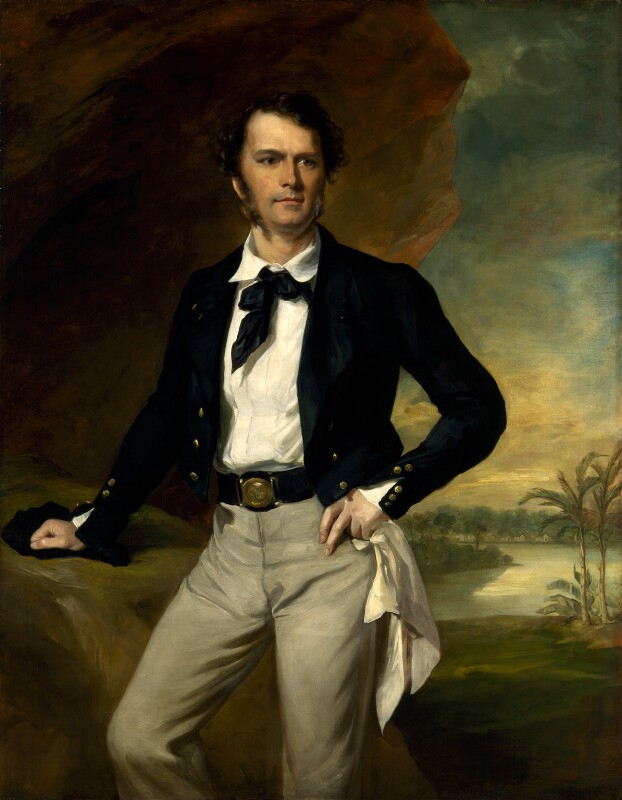

Sir James Brooke, Rajah of Sarawak (29 April 1803 – 11 June 1868), was a British soldier and adventurer who founded the Raj of Sarawak in

Brooke was born in

Brooke was born in

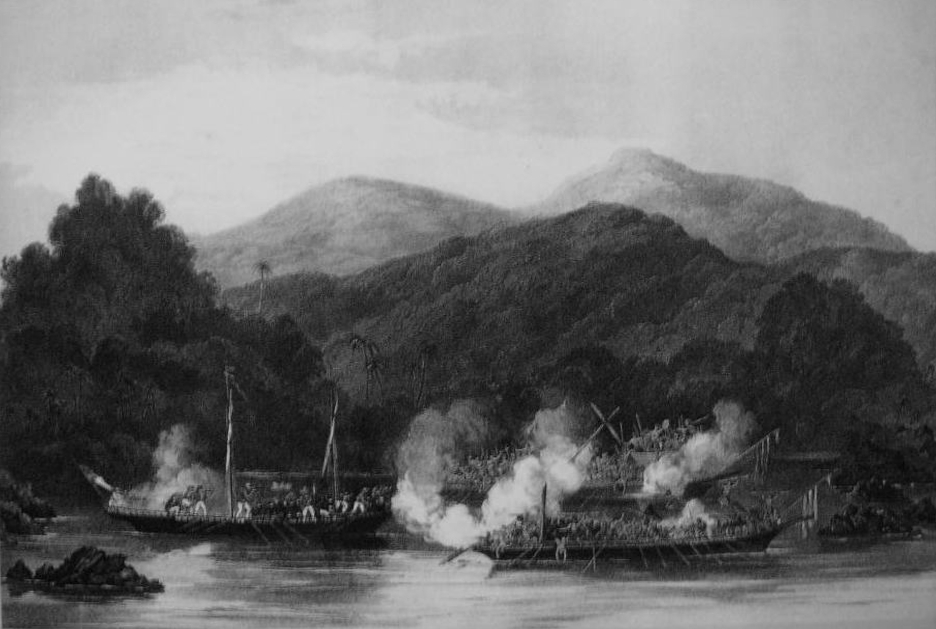

Brooke began 1844 in anti-pirate operations with ships of the Royal Navy and the East India Company off NE Sumatra: on 12 February, he received a gunshot wound to his right arm and a spear cut to his eyebrow in their second engagement, at Murdu. Later in 1844 Brooke presented the island of

Brooke began 1844 in anti-pirate operations with ships of the Royal Navy and the East India Company off NE Sumatra: on 12 February, he received a gunshot wound to his right arm and a spear cut to his eyebrow in their second engagement, at Murdu. Later in 1844 Brooke presented the island of

During his reign, Brooke began to establish and cement his rule over Sarawak: reforming the administration, codifying laws and fighting piracy, which proved to be an ongoing issue throughout his rule. Brooke returned temporarily to England in 1847, where he was given the

During his reign, Brooke began to establish and cement his rule over Sarawak: reforming the administration, codifying laws and fighting piracy, which proved to be an ongoing issue throughout his rule. Brooke returned temporarily to England in 1847, where he was given the  Brooke became the centre of controversy in 1851 when accusations against him of excessive use of force against the native people, under the guise of anti-piracy operations, ultimately led to the appointment of a Commission of Inquiry in

Brooke became the centre of controversy in 1851 when accusations against him of excessive use of force against the native people, under the guise of anti-piracy operations, ultimately led to the appointment of a Commission of Inquiry in

James Brooke was 'a great admirer' of the novels of

James Brooke was 'a great admirer' of the novels of

Having suffered three strokes over the last ten years, Brooke died in

Having suffered three strokes over the last ten years, Brooke died in

"The Enigmatic Sir James Brooke."

''Contemporary Review'', July 2003. (Book review of ''White Rajah'' by Nigel Barley. Little, Brown. .) * Jacob, Gertrude Le Grand.

''The Raja of Saráwak: An Account of Sir James Brooks. K. C. B., LL. D., Given Chiefly Through Letters and Journals''

London: MacMillan, 1876. * Rutter, Owen (ed) ''Rajah Brooke & Baroness Burdett Coutts. Consisting of the letters from Sir James Brooke to Miss Angela, afterwards Baroness, Burdett Coutts'' 1935. * Wason, Charles William. ''The Annual Register: A Review of Public Events at Home and Abroad for the Year 1868.'' London: Rivingtons, Waterloo Place, 1869.

pp. 162–163

Adventures of Sir James Brooke, K.C.B., Rajah of Sarawak, "sovereign de facto of Borneo proper," late governor of Labuan: from Rajah Brooke's own diary and correspondence, or from government official documents

'' London: Effingham Wilson. * Hahn, Emily (1953) ''James Brooke of Sarawak'', London, Arthur Barker. * Ingleson, John (1979) ''Expanding the empire: James Brooke and the Sarawak lobby, 1839–1868'', Nedlands, W.A.: Centre for South and Southeast Asian Studies, University of Western Australia. * Payne, Robert (1960) ''The White Rajahs of Sarawak'', Robert Hale. * Pybus, Cassandra (1996) 'White Rajah: A Dynastic Intrigue' University of Queensland Press. * Runciman, Steve (1960) ''The White Rajahs: A History of Sarawak from 1841 to 1946'', Cambridge University Press. * Tarling, Nicholas (1982) ''The burthen, the risk, and the glory: a biography of Sir James Brooke'', Kuala Lumpur; New York: Oxford University Press. {{DEFAULTSORT:Brooke, James 1803 births 1868 deaths Anglo-Scots James Brooke People involved in anti-piracy efforts People educated at Norwich School Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath 19th-century monarchs in Asia Southeast Asian monarchs Burials in Devon Administrators in British Brunei

Borneo

Borneo (; id, Kalimantan) is the third-largest island in the world and the largest in Asia. At the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, in relation to major Indonesian islands, it is located north of Java, west of Sulawesi, and e ...

. He ruled as the first White Rajah of Sarawak from 1841 until his death in 1868.

Brooke was born and raised during the Company Raj

Company rule in India (sometimes, Company ''Raj'', from hi, rāj, lit=rule) refers to the rule of the British East India Company on the Indian subcontinent. This is variously taken to have commenced in 1757, after the Battle of Plassey, when ...

of the British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

in India. After a few years of education in England, he served in the Bengal Army

The Bengal Army was the army of the Bengal Presidency, one of the three presidencies of British India within the British Empire.

The presidency armies, like the presidencies themselves, belonged to the East India Company (EIC) until the Gover ...

, was wounded, and resigned his commission. He then bought a ship and sailed out to the Malay Archipelago where, by helping to crush a rebellion, he became governor of Sarawak. He then vigorously suppressed piracy in the region and, in the ensuing turmoil, restored the Sultan of Brunei

The sultan of Brunei is the monarchical head of state of Brunei and head of government in his capacity as prime minister of Brunei. Since independence from the British in 1984, only one sultan has reigned, though the royal institution dates ...

to his throne, for which the Sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it c ...

made Brooke the Rajah of Sarawak. He ruled until his death.

Brooke was not without detractors and was criticised in the British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprem ...

and officially investigated in Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

for his anti-piracy measures. He was, however, honoured and feted in London for his activities in Southeast Asia. The naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was a British natural history, naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He is best known for independently conceiving the theory of evolution thro ...

was one of many visitors whose published work spoke of his hospitality and achievements.

Early life

Bandel

Bandel is a neighbourhood in the Hooghly district of the Indian state of West Bengal. It is founded by Portuguese settlers and falls under the jurisdiction of Chandernagore Police Commissionerate. It is a part of the area covered by Kolkata Me ...

, near Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , the official name until 2001) is the capital of the Indian state of West Bengal, on the eastern bank of the Hooghly River west of the border with Bangladesh. It is the primary business, commer ...

, Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

, but baptised in Secrole, a suburb of Benares

Varanasi (; ; also Banaras or Benares (; ), and Kashi.) is a city on the Ganges river in northern India that has a central place in the traditions of pilgrimage, death, and mourning in the Hindu world.

*

*

*

* The city has a syncretic tra ...

. His father, Thomas Brooke, was an English Judge in the Court of Appeal at Bareilly

Bareilly () is a city in Bareilly district in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. It is among the largest metropolises in Western Uttar Pradesh and is the centre of the Bareilly division as well as the historical region of Rohilkhand. The ...

, British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

; his mother, Anna Maria, born in Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For gov ...

, was the daughter of Scottish peer

Peer may refer to:

Sociology

* Peer, an equal in age, education or social class; see Peer group

* Peer, a member of the peerage; related to the term "peer of the realm"

Computing

* Peer, one of several functional units in the same layer of a ne ...

Colonel William Stuart, 9th Lord Blantyre

Lord Blantyre was a title in the Peerage of Scotland. It was created in 1606 for the politician Walter Stewart. The lordship was named for Blantyre Priory in Lanarkshire, where Walter Stewart had been commendator. The main residences associated ...

, and his mistress Harriott Teasdale. Brooke stayed at home in India until he was sent, aged 12, to England for a brief education at Norwich School

Norwich School (formally King Edward VI Grammar School, Norwich) is a selective English independent day school in the close of Norwich Cathedral, Norwich. Among the oldest schools in the United Kingdom, it has a traceable history to 1096 as a ...

from which he ran away. Some home tutoring followed in Bath

Bath may refer to:

* Bathing, immersion in a fluid

** Bathtub, a large open container for water, in which a person may wash their body

** Public bathing, a public place where people bathe

* Thermae, ancient Roman public bathing facilities

Plac ...

before he returned to India in 1819 as an ensign

An ensign is the national flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality. The ensign is the largest flag, generally flown at the stern (rear) of the ship while in port. The naval ensign (also known as war ensign), used on warships, may be diffe ...

in the Bengal Army

The Bengal Army was the army of the Bengal Presidency, one of the three presidencies of British India within the British Empire.

The presidency armies, like the presidencies themselves, belonged to the East India Company (EIC) until the Gover ...

of the British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

. He saw action in Assam

Assam (; ) is a state in northeastern India, south of the eastern Himalayas along the Brahmaputra and Barak River valleys. Assam covers an area of . The state is bordered by Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh to the north; Nagaland and Manipur ...

during the First Anglo-Burmese War

The First Anglo-Burmese War ( my, ပထမ အင်္ဂလိပ်-မြန်မာ စစ်; ; 5 March 1824 – 24 February 1826), also known as the First Burma War, was the first of three wars fought between the British and Burmes ...

until seriously wounded in 1825, and was sent to England for recovery. In 1830, he arrived back in Madras

Chennai (, ), formerly known as Madras ( the official name until 1996), is the capital city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost Indian state. The largest city of the state in area and population, Chennai is located on the Coromandel Coast of th ...

but was too late to rejoin his unit, and resigned his commission. He remained on the ship he had travelled out in, the ''Castle Huntley'', and returned home via China.

Sarawak

Brooke attempted to trade in the Far East, but was not successful. In 1835 he inherited £30,000 (£3M or US$3.7M in 2022 currency), which he used as capital to purchase a 142-ton schooner, ''Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gov ...

''.

Setting sail for Borneo

Borneo (; id, Kalimantan) is the third-largest island in the world and the largest in Asia. At the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, in relation to major Indonesian islands, it is located north of Java, west of Sulawesi, and e ...

in 1838, he arrived in Kuching

Kuching (), officially the City of Kuching, is the capital and the most populous city in the state of Sarawak in Malaysia. It is also the capital of Kuching Division. The city is on the Sarawak River at the southwest tip of the state of Sar ...

in August to find the settlement facing an uprising against the Sultan of Brunei

The sultan of Brunei is the monarchical head of state of Brunei and head of government in his capacity as prime minister of Brunei. Since independence from the British in 1984, only one sultan has reigned, though the royal institution dates ...

. Greatly impressed with the Malay Archipelago, in Sarawak

Sarawak (; ) is a state of Malaysia. The largest among the 13 states, with an area almost equal to that of Peninsular Malaysia, Sarawak is located in northwest Borneo Island, and is bordered by the Malaysian state of Sabah to the northeast, ...

he met the sultan's uncle, Pangeran Muda Hashim, to whom he gave assistance in crushing the rebellion, thereby winning the gratitude of the Omar Ali Saifuddin II

Omar Ali Saifuddin II (; ; 3 February 1799 – 20 November 1852) was the 23rd Sultan of Brunei, then known as the Bruneian Empire. During his reign, Western powers such as Great Britain and the United States visited the country. His reign saw ...

, the 23rd Sultan of Brunei

The sultan of Brunei is the monarchical head of state of Brunei and head of government in his capacity as prime minister of Brunei. Since independence from the British in 1984, only one sultan has reigned, though the royal institution dates ...

, who in 1841 offered Brooke the governorship of Sarawak in return for his help.

Rajah Brooke was highly successful in suppressing the widespread piracy of the region. However, some Malay nobles in Brunei, unhappy over Brooke's measures against piracy, arranged for the murder of Muda Hashim and his followers. Brooke, with assistance from a unit of Britain's China Squadron, took over Brunei and restored its sultan to the throne.

In 1842, the Sultan ceded complete sovereignty of Sarawak to Brooke. He was granted the title of Rajah of Sarawak

The White Rajahs were a dynastic monarchy of the British Brooke family, who founded and ruled the Raj of Sarawak, located on the north west coast of the island of Borneo, from 1841 to 1946. The first ruler was Briton James Brooke. As a reward f ...

on 24 September 1841, although the official declaration was not made until 18 August 1842. Brooke's cousin Arthur Chichester Crookshank (1825–1891) joined his service on 1 March 1843 and was appointed a magistrate.

Cession of Labuan to Great Britain

Brooke began 1844 in anti-pirate operations with ships of the Royal Navy and the East India Company off NE Sumatra: on 12 February, he received a gunshot wound to his right arm and a spear cut to his eyebrow in their second engagement, at Murdu. Later in 1844 Brooke presented the island of

Brooke began 1844 in anti-pirate operations with ships of the Royal Navy and the East India Company off NE Sumatra: on 12 February, he received a gunshot wound to his right arm and a spear cut to his eyebrow in their second engagement, at Murdu. Later in 1844 Brooke presented the island of Labuan

Labuan (), officially the Federal Territory of Labuan ( ms, Wilayah Persekutuan Labuan), is a Federal Territory of Malaysia. Its territory includes and six smaller islands, off the coast of the state of Sabah in East Malaysia. Labuan's capita ...

to the British government. He was appointed governor and commander-in-chief of Labuan

Labuan (), officially the Federal Territory of Labuan ( ms, Wilayah Persekutuan Labuan), is a Federal Territory of Malaysia. Its territory includes and six smaller islands, off the coast of the state of Sabah in East Malaysia. Labuan's capita ...

in 1848.

Reign

During his reign, Brooke began to establish and cement his rule over Sarawak: reforming the administration, codifying laws and fighting piracy, which proved to be an ongoing issue throughout his rule. Brooke returned temporarily to England in 1847, where he was given the

During his reign, Brooke began to establish and cement his rule over Sarawak: reforming the administration, codifying laws and fighting piracy, which proved to be an ongoing issue throughout his rule. Brooke returned temporarily to England in 1847, where he was given the Freedom of the City

The Freedom of the City (or Borough in some parts of the UK) is an honour bestowed by a municipality upon a valued member of the community, or upon a visiting celebrity or dignitary. Arising from the medieval practice of granting respected ...

of London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, appointed British consul-general

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

in Borneo and created a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved bathing (as a symbol of purification) a ...

(KCB).

Brooke pacified the native peoples, including the Dayaks, and suppressed headhunting

Headhunting is the practice of hunting a human and collecting the severed head after killing the victim, although sometimes more portable body parts (such as ear, nose or scalp) are taken instead as trophies. Headhunting was practiced in h ...

and piracy. He had many Dayaks in his forces and said that only Dayaks can kill Dayaks.

Brooke became the centre of controversy in 1851 when accusations against him of excessive use of force against the native people, under the guise of anti-piracy operations, ultimately led to the appointment of a Commission of Inquiry in

Brooke became the centre of controversy in 1851 when accusations against him of excessive use of force against the native people, under the guise of anti-piracy operations, ultimately led to the appointment of a Commission of Inquiry in Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

in 1854. After investigation, the Commission dismissed the charges but the accusations continued to haunt him.

Brooke wrote to Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was a British natural history, naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He is best known for independently conceiving the theory of evolution thro ...

on leaving England in April 1853, "to assure Wallace that he would be very glad to see him at Sarawak." This was an invitation that helped Wallace decide on the Malay Archipelago for his next expedition, an expedition that lasted for eight years and established him as one of the foremost Victorian intellectuals and naturalists of the time. When Wallace arrived in Singapore in September 1854, he found Rajah Brooke "reluctantly preparing to give evidence to the special commission set up to investigate his controversial anti-piracy activities."

During his rule, Brooke suppressed an uprising by Liu Shan Bang in 1857 and faced threats from Sarawak warriors like Sharif Masahor

Sharif Masahor bin Muhammad Al-Shahab, also written as Syed Mashhor and commonly known as Syarif Masahor, or Sharif Masahor in Malayan contexts, (died 1890 in Selangor) was a famous Malay rebel of Hadhrami descent in Sarikei, Sarawak state, ...

and Rentap and managed to suppress them.

Personal life

James Brooke was 'a great admirer' of the novels of

James Brooke was 'a great admirer' of the novels of Jane Austen

Jane Austen (; 16 December 1775 – 18 July 1817) was an English novelist known primarily for her six major novels, which interpret, critique, and comment upon the British landed gentry at the end of the 18th century. Austen's plots of ...

, and would 'read them and re-read them', including aloud to his companions in Sarawak.

Brooke was influenced by the success of previous British adventurers and the exploits of the British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

. His actions in Sarawak were directed at expanding the British Empire and the benefits of its rule, assisting the local people by fighting piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

and slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, and securing his own personal wealth to further these activities. His own abilities, and those of his successors, provided Sarawak with excellent leadership and wealth generation during difficult times, and resulted in both fame and notoriety in some circles. His appointment as Rajah by the Sultan, and his subsequent knighthood, are evidence that his efforts were widely applauded in both Sarawak and British society.

Among his alleged relationships was one with Badruddin, a Sarawak prince, of whom he wrote, "my love for him was deeper than anyone I knew." This phrase led to some considering him to be either homosexual or bisexual. Later, in 1848, Brooke is alleged to have formed a relationship with 16‑year‑old Charles T. C. Grant, grandson of the seventh Earl of Elgin

Earl of Elgin is a title in the Peerage of Scotland, created in 1633 for Thomas Bruce, 3rd Lord Kinloss. He was later created Baron Bruce, of Whorlton in the County of York, in the Peerage of England on 30 July 1641. The Earl of Elgin is the h ...

, who supposedly 'reciprocated'. Whether this relationship was purely a friendship or otherwise has not been fully revealed. One of Brooke's recent biographers wrote that during Brooke's final years in Burrator

Burrator is a grouped parish council in the English county of Devon. It is entirely within the boundaries of the Dartmoor National Park and was formed as a result of the Local Government Act 1972 from the older councils of Meavy, Sheepstor and Wa ...

in Devon "there is little doubt ... he was carnally involved with the rough trade

Rough Trade may refer to:

* Rough Trade Records, a record label

*Rough Trade (shops)

Rough Trade is a group of independent record shops in the United Kingdom and the United States with headquarters in London.

The first Rough Trade shop was o ...

of Totnes

Totnes ( or ) is a market town and civil parish at the head of the estuary of the River Dart in Devon, England, within the South Devon Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. It is about west of Paignton, about west-southwest of Torquay and abo ...

." However, Barley does not note from where he garnered this opinion. Others have suggested Brooke was instead "homo-social" and simply preferred the social company of other men, disagreeing with assertions he was a homosexual.

Although Brooke died unmarried, he did acknowledge a son to his family in 1858. Neither the identity of the son's mother nor his birth date is clear. This son was brought up as Reuben George Walker in the Brighton household of Frances Walker (1841 and 1851 census, apparently born ca. 1836). By 1858 he was aware of his Brooke connection and by 1871 he is on the census at the parish of Plumtree, Nottinghamshire as "George Brooke", age "40", birthplace "Sarawak, Borneo". He married Martha Elizabeth Mowbray on 10 July 1862, and had seven children, three of whom survived infancy; the oldest was called James. George died travelling to Australia, in the wreck of the SS ''British Admiral'' on 23 May 1874. A memorial to this effect – giving a birthdate of 1834 – is in the churchyard at Plumtree.

It has also been mentioned by Francis William Douglas (1874–1953), the Acting Resident for Brunei and Labuan from November 1913 to January 1915 in his letter to the Foreign Office on 19 July 1915 that he heard from the Bruneian woman Pengiran Anak Hashima that Brooke was married, by Muslim rites, to her aunt Pengiran Anak Fatima, the daughter of Pengiran Anak Abdul Kadir and also the granddaughter of Sultan Muhammad Kanzul Alam, the 21st Sultan of Brunei. This marriage would not be valid in Europe. They had a daughter, who was interviewed by the then British Consul in 1864. Douglas also mentioned about this daughter on the same letter after he met a physician Dr Ogilvie quite recently who told him that he had met Brooke's already married Bruneian daughter in 1866.

Succession, death and burial

Having no legitimate children, in 1861 he formally named CaptainJohn Brooke Johnson Brooke

John Brooke Johnson Brooke (born John Brooke Johnson, 1823 – 1 December 1868) was a soldier and Rajah Muda, heir to the Raj, of the Raj of Sarawak until disinherited in favour of his younger brother, Charles.

Born in South Stoke near Bath, ...

, his sister's eldest son, as his successor. Two years later, the Rajah reacted to criticism by returning to the east: after a brief meeting in Singapore, John was deposed and banished from Sarawak. James increased the charges to treasonous conduct and later named John's younger brother, Charles Anthoni Johnson Brooke

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was ...

, as his successor.

Having suffered three strokes over the last ten years, Brooke died in

Having suffered three strokes over the last ten years, Brooke died in Burrator

Burrator is a grouped parish council in the English county of Devon. It is entirely within the boundaries of the Dartmoor National Park and was formed as a result of the Local Government Act 1972 from the older councils of Meavy, Sheepstor and Wa ...

, Dartmoor

Dartmoor is an upland area in southern Devon, England. The moorland and surrounding land has been protected by National Park status since 1951. Dartmoor National Park covers .

The granite which forms the uplands dates from the Carboniferous P ...

, Devonshire

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, ...

in England on 11 June 1868 and was buried at the graveyard of St Leonard's Church in Sheepstor.

In popular culture

Fictionalised accounts of Brooke's exploits in Sarawak include '' Kalimantaan'' by C. S. Godshalk and ''The White Rajah'' byNicholas Monsarrat

Lieutenant Commander Nicholas John Turney Monsarrat FRSL RNVR (22 March 19108 August 1979) was a British novelist known for his sea stories, particularly '' The Cruel Sea'' (1951) and ''Three Corvettes'' (1942–45), but perhaps known best i ...

. Another book, also called ''The White Rajah'', by Tom Williams, was published by JMS Books in 2010. Brooke is also featured in ''Flashman's Lady

''Flashman's Lady'' is a 1977 novel by George MacDonald Fraser. It is the sixth of the Flashman novels.

Plot introduction

Presented within the frame of the supposedly discovered historical Flashman Papers, this book describes the bully Flashma ...

'', the 6th book in George MacDonald Fraser

George MacDonald Fraser (2 April 1925 – 2 January 2008) was a British author and screenwriter. He is best known for a series of works that featured the character Flashman.

Biography

Fraser was born to Scottish parents in Carlisle, England, ...

's meticulously researched ''The Flashman Papers

''The Flashman Papers'' is a series of novels and shorter stories written by George MacDonald Fraser, the first of which was published in 1969. The books centre on the exploits of the fictional protagonist Harry Flashman. He is a cowardly Bri ...

'' novels; and in ''Sandokan: The Pirates of Malaysia

''The Pirates of Malaysia'' ( it, I pirati della Malesia) is an exotic adventure novel written by Italian author Emilio Salgari, published in 1896. It features his most famous character, Sandokan, and is a sequel to ''The Tigers of Mompracem''.

Sy ...

'' (''I pirati della Malesia''), the second novel in Emilio Salgari

Emilio Salgari (, but often erroneously ; 21 August 1862 – 25 April 1911) was an Italian writer of action adventure swashbucklers and a pioneer of science fiction

Science fiction (sometimes shortened to Sci-Fi or SF) is a genre of spe ...

's Sandokan

Sandokan is a fictional late 19th-century pirate created by Italian author Emilio Salgari. His adventures first appeared in publication in 1883. Sandokan is the protagonist of 11 adventure novels. Sandokan is known throughout the South China ...

series.

Brooke was also a model for the hero of Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Polish-British novelist and short story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in the English language; though he did not spe ...

's novel ''Lord Jim

''Lord Jim'' is a novel by Joseph Conrad originally published as a serial in ''Blackwood's Magazine'' from October 1899 to November 1900. An early and primary event in the story is the abandonment of a passenger ship in distress by its crew, i ...

'', and he is briefly mentioned in Kipling's short story " The Man Who Would Be King".

Charles Kingsley

Charles Kingsley (12 June 1819 – 23 January 1875) was a broad church priest of the Church of England, a university professor, social reformer, historian, novelist and poet. He is particularly associated with Christian socialism, the worki ...

dedicated the novel ''Westward Ho!

Westward Ho! is a seaside village near Bideford in Devon, England. The A39 road provides access from the towns of Barnstaple, Bideford, and Bude. It lies at the south end of Northam Burrows and faces westward into Bideford Bay, opposite Sau ...

'' (1855) to Brooke.

In 1936, Errol Flynn

Errol Leslie Thomson Flynn (20 June 1909 – 14 October 1959) was an Australian-American actor who achieved worldwide fame during the Classical Hollywood cinema, Golden Age of Hollywood. He was known for his romantic swashbuckler roles, freque ...

intended to star in a film of Brooke's life called ''The White Rajah'' for Warner Bros., based on a script by Flynn himself. However, although the project was announced for filming, it was never made.

In September 2016, a film based on Brooke's life was to be made in Sarawak

Sarawak (; ) is a state of Malaysia. The largest among the 13 states, with an area almost equal to that of Peninsular Malaysia, Sarawak is located in northwest Borneo Island, and is bordered by the Malaysian state of Sabah to the northeast, ...

with the support of Abang Abdul Rahman Johari

Abang may refer to:

Geography

* Rantau Abang (Abang region), small village located in Terengganu, Malaysia

*Tanah Abang (Abang land), subdistrict of Central Jakarta, Indonesia

* Gunung Abang (Mount Abang), a mountain part of the caldera of Mount B ...

of the Government of Sarawak, with writer Rob Allyn and Sergei Bodrov as its director. The Brooke Heritage Trust, a non-profit organisation, was to serve as the film's technical advisors, with one of them being Jason Brooke, the current heir of the Brooke family. The film, titled ''Edge of the World

''Edge of the World'' is an album created by Judas Priest guitarist Glenn Tipton, featuring outtakes from his solo album '' Baptizm of Fire''. The Who bassist John Entwistle and drummer Cozy Powell, both recently deceased, were the session play ...

'', was released in 2021.

Honours and legacy

British Honours * KCB:Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved Bathing#Medieval ...

, ''1848''

Some Bornean plant species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriat ...

were named in Brooke's honour:

* ''Rhododendron brookeanum'', a flowering plant named by Hugh Low

Sir Hugh Low, (10 May 182418 April 1905) was a British colonial administrator and naturalist. After a long residence in various colonial roles in Labuan, he was appointed as British administrator in the Malay Peninsula where he made the first ...

and John Lindley

John Lindley FRS (5 February 1799 – 1 November 1865) was an English botanist, gardener and orchidologist.

Early years

Born in Catton, near Norwich, England, John Lindley was one of four children of George and Mary Lindley. George Lindley w ...

, now included in '' Rhododendron javanicum''

* Rajah Brooke's Pitcher Plant (''Nepenthes rajah

''Nepenthes rajah'' is a carnivorous pitcher plant species of the family Nepenthaceae. It is endemic to Mount Kinabalu and neighbouring Mount Tambuyukon in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo.Clarke 1997, p. 123. ''Nepenthes rajah'' grows exclusively ...

''), a pitcher plant named by Joseph Dalton Hooker

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (30 June 1817 – 10 December 1911) was a British botanist and explorer in the 19th century. He was a founder of geographical botany and Charles Darwin's closest friend. For twenty years he served as director of ...

also insects:

* Rajah Brooke's Birdwing (''Trogonoptera brookiana

''Trogonoptera brookiana'', Rajah Brooke's birdwing, is a birdwing butterfly from the rainforests of the Thai-Malay Peninsula, Borneo, Natuna, Sumatra, and various small islands west of Sumatra ( Banyak, Simeulue, Batu and Mentawai).ARKivRajah ...

''), a butterfly named by Alfred R. Wallace

* Rajah Brooke's Stag Beetle, ''Lucanus brookeanus'' Snellen Van Vollenhoven, 1861 = '' Odontolabis brookeana'', collected by Alfred R. Wallace

three species of reptiles:

* Brooke's house gecko, ''Hemidactylus brookii

''Hemidactylus brookii'', also known commonly as Brooke's house gecko and the spotted house gecko, is a widespread species of lizard in the family Gekkonidae.

Etymology

The specific name, ''brookii'', is in honor of British adventurer Jame ...

''

* Brooke's sea snake, '' Hydrophis brookii''

* Brooke's keeled skink, ''Tropidophorus brookei

''Tropidophorus brookei'', also known commonly as Brook's keeled skink and Brooke's keeled skink, is a species of lizard in the family Scincidae. The species is endemic to the island of Borneo.

Etymology

The specific name, ''brookei'', is in ...

''

and a snail:

* ''Bertia (Ryssota) brookei'' (Adams & Reeve, 1848)

In 1857, the native village of Newash in Grey County

Grey County is a county of the Canadian province of Ontario. The county seat is in Owen Sound. It is located in the subregion of Southern Ontario named Southwestern Ontario. Grey County is also a part of the Georgian Triangle. At the time of t ...

, Ontario, Canada, was renamed Brooke and the adjacent township was named Sarawak by William Coutts Keppel (known as Viscount Bury, later the 7th Earl of Albemarle) who was Superintendent of Indian Affairs in Canada. James Brooke was a close friend of Viscount Bury's uncle, Henry Keppel

Admiral of the Fleet The Honourable Sir Henry Keppel (14 June 1809 – 17 January 1904) was a Royal Navy officer. His first command was largely spent off the coast of Spain, which was then in the midst of the First Carlist War. As commanding off ...

; they had met in 1843 while fighting pirates off the coast of Borneo.Jacob, Gertrude L. ''The Raja of Saráwak: An Account of Sir James Brooke''. London: Macmillan, 1876, vol. 1, ch. XIII. Townships to the northwest of Sarawak were named Keppel and Albemarle. In 2001, Sarawak and Keppel became part of the township of Georgian Bluffs

Georgian Bluffs is a township in southwestern Ontario, Canada, in Grey County located between Colpoy's Bay and Owen Sound on Georgian Bay.

The township was incorporated on January 1, 2001, by amalgamating the former townships of Derby, Keppel, ...

; Albemarle joined the town of South Bruce Peninsula in 1999. Keppel-Sarawak School is located in Owen Sound, Ontario.

Brooke's Point, a major municipality on the island of Palawan

Palawan (), officially the Province of Palawan ( cyo, Probinsya i'ang Palawan; tl, Lalawigan ng Palawan), is an archipelagic province of the Philippines that is located in the region of Mimaropa. It is the largest province in the country in t ...

, Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, is named after him. Both Brooke's Lighthouse and Brooke's Port, historical landmarks in Brooke's Point, are believed to have been constructed by Sir James Brooke. Today, owing to erosion and the constant movement of the tides, only a few stones can still be seen at the Port. The remnants of the original lighthouse tower are still visible, although the area is now occupied by a new lighthouse.

Notes

:a.The term '' Rajah'' reflects traditional usage in Sarawak and English writing, although ''Raja

''Raja'' (; from , IAST ') is a royal title used for South Asian monarchs. The title is equivalent to king or princely ruler in South Asia and Southeast Asia.

The title has a long history in South Asia and Southeast Asia, being attested ...

'' may be better orthography in Malay.

References

Sources

* Barley, Nigel (2002), ''White Rajah'', Time Warner: London. . * Cavendish, Richard, "Birth of Sir James Brooke", ''History Today''. April 2003, Vol. 53, Issue 4. * Doering, Jonathan."The Enigmatic Sir James Brooke."

''Contemporary Review'', July 2003. (Book review of ''White Rajah'' by Nigel Barley. Little, Brown. .) * Jacob, Gertrude Le Grand.

''The Raja of Saráwak: An Account of Sir James Brooks. K. C. B., LL. D., Given Chiefly Through Letters and Journals''

London: MacMillan, 1876. * Rutter, Owen (ed) ''Rajah Brooke & Baroness Burdett Coutts. Consisting of the letters from Sir James Brooke to Miss Angela, afterwards Baroness, Burdett Coutts'' 1935. * Wason, Charles William. ''The Annual Register: A Review of Public Events at Home and Abroad for the Year 1868.'' London: Rivingtons, Waterloo Place, 1869.

pp. 162–163

Further reading

* Foggo, George (1853)Adventures of Sir James Brooke, K.C.B., Rajah of Sarawak, "sovereign de facto of Borneo proper," late governor of Labuan: from Rajah Brooke's own diary and correspondence, or from government official documents

'' London: Effingham Wilson. * Hahn, Emily (1953) ''James Brooke of Sarawak'', London, Arthur Barker. * Ingleson, John (1979) ''Expanding the empire: James Brooke and the Sarawak lobby, 1839–1868'', Nedlands, W.A.: Centre for South and Southeast Asian Studies, University of Western Australia. * Payne, Robert (1960) ''The White Rajahs of Sarawak'', Robert Hale. * Pybus, Cassandra (1996) 'White Rajah: A Dynastic Intrigue' University of Queensland Press. * Runciman, Steve (1960) ''The White Rajahs: A History of Sarawak from 1841 to 1946'', Cambridge University Press. * Tarling, Nicholas (1982) ''The burthen, the risk, and the glory: a biography of Sir James Brooke'', Kuala Lumpur; New York: Oxford University Press. {{DEFAULTSORT:Brooke, James 1803 births 1868 deaths Anglo-Scots James Brooke People involved in anti-piracy efforts People educated at Norwich School Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath 19th-century monarchs in Asia Southeast Asian monarchs Burials in Devon Administrators in British Brunei