Jack Parsons (rocket engineer) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Whiteside Parsons (born Marvel Whiteside Parsons; October 2, 1914 – June 17, 1952) was an American rocket engineer,

The Parsons family spent mid-1929 touring Europe before returning to Pasadena, where they moved into a house on San Rafael Avenue. With the onset of the

The Parsons family spent mid-1929 touring Europe before returning to Pasadena, where they moved into a house on San Rafael Avenue. With the onset of the

In hopes of gaining access to the state-of-the-art resources of Caltech for their rocketry research, Parsons and Forman attended a lecture on the work of Austrian rocket engineer

In hopes of gaining access to the state-of-the-art resources of Caltech for their rocketry research, Parsons and Forman attended a lecture on the work of Austrian rocket engineer  Parsons met Helen Northrup at a local church dance and proposed marriage in July 1934. She accepted and they were married in April 1935 at the Little Church of the Flowers in

Parsons met Helen Northrup at a local church dance and proposed marriage in July 1934. She accepted and they were married in April 1935 at the Little Church of the Flowers in  In April 1937, Caltech mathematician

In April 1937, Caltech mathematician

For the JATO project, they were joined by Caltech mathematician

For the JATO project, they were joined by Caltech mathematician

The Group then agreed to produce and sell 60 JATO engines to the

The Group then agreed to produce and sell 60 JATO engines to the

Aerojet's first two contracts were from the U.S. Navy; the

Aerojet's first two contracts were from the U.S. Navy; the  Crowley and Germer wanted to see Smith removed as head of the Agape Lodge, believing that he had become a bad influence on its members. Parsons and Helen wrote to them to defend their mentor but Germer ordered him to stand down; Parsons was appointed as temporary head of the Lodge. Some veteran Lodge members disliked Parsons' influence, concerned that it encouraged excessive sexual

Crowley and Germer wanted to see Smith removed as head of the Agape Lodge, believing that he had become a bad influence on its members. Parsons and Helen wrote to them to defend their mentor but Germer ordered him to stand down; Parsons was appointed as temporary head of the Lodge. Some veteran Lodge members disliked Parsons' influence, concerned that it encouraged excessive sexual  By mid-1943, Aerojet was operating on a budget of $650,000. The same year Parsons and von Kármán traveled to

By mid-1943, Aerojet was operating on a budget of $650,000. The same year Parsons and von Kármán traveled to

Now disassociated from JPL and Aerojet, Parsons and Forman founded the Ad Astra Engineering Company, under which Parsons founded the chemical manufacturing Vulcan Powder Company. Ad Astra was subject to an FBI investigation under suspicion of espionage when security agents from the

Now disassociated from JPL and Aerojet, Parsons and Forman founded the Ad Astra Engineering Company, under which Parsons founded the chemical manufacturing Vulcan Powder Company. Ad Astra was subject to an FBI investigation under suspicion of espionage when security agents from the

Parsons was employed by

Parsons was employed by  Parsons testified to a closed federal court that the moral philosophy of Thelema was both anti-fascist and anti-communist, emphasizing his belief in individualism. This along with references from his scientific colleagues resulted in his security clearance being reinstated by the Industrial Employment Review Board, which ruled that there was insufficient evidence that he had ever had communist sympathies. This allowed Parsons to obtain a contract in designing and constructing a chemical plant for the

Parsons testified to a closed federal court that the moral philosophy of Thelema was both anti-fascist and anti-communist, emphasizing his belief in individualism. This along with references from his scientific colleagues resulted in his security clearance being reinstated by the Industrial Employment Review Board, which ruled that there was insufficient evidence that he had ever had communist sympathies. This allowed Parsons to obtain a contract in designing and constructing a chemical plant for the

In the decades following his death, Parsons was well remembered among the Western esoteric community; his scientific recognition frequently amounted to a footnote. For instance, English Thelemite Kenneth Grant suggested that Parsons' Babalon Working marked the start of the appearance of flying saucers in the skies, leading to phenomena such as the Roswell UFO incident and Kenneth Arnold UFO sighting. Cameron postulated that the 1952 Washington, D.C. UFO incident was a spiritual reaction to Parsons' death. In 1954 she portrayed Babalon in American Thelemite Kenneth Anger's short film ''Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome'', viewing this cinematic depiction of a Thelemic ritual as aiding the literal invocation of Babalon begun by Parsons' working, and later said that his ''Book of the AntiChrist'' prophecies were fulfilled through the manifestation of Babalon in her person.

In December 1958, JPL was integrated into the newly established National Aeronautics and Space Administration, having built the ''Explorer 1'' satellite that commenced America's Space Race with the Soviet Union. Aerojet was contracted by NASA to build the main engine of the Apollo Command/Service Module, and the Space Shuttle Orbital Maneuvering System. In a letter to

In the decades following his death, Parsons was well remembered among the Western esoteric community; his scientific recognition frequently amounted to a footnote. For instance, English Thelemite Kenneth Grant suggested that Parsons' Babalon Working marked the start of the appearance of flying saucers in the skies, leading to phenomena such as the Roswell UFO incident and Kenneth Arnold UFO sighting. Cameron postulated that the 1952 Washington, D.C. UFO incident was a spiritual reaction to Parsons' death. In 1954 she portrayed Babalon in American Thelemite Kenneth Anger's short film ''Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome'', viewing this cinematic depiction of a Thelemic ritual as aiding the literal invocation of Babalon begun by Parsons' working, and later said that his ''Book of the AntiChrist'' prophecies were fulfilled through the manifestation of Babalon in her person.

In December 1958, JPL was integrated into the newly established National Aeronautics and Space Administration, having built the ''Explorer 1'' satellite that commenced America's Space Race with the Soviet Union. Aerojet was contracted by NASA to build the main engine of the Apollo Command/Service Module, and the Space Shuttle Orbital Maneuvering System. In a letter to

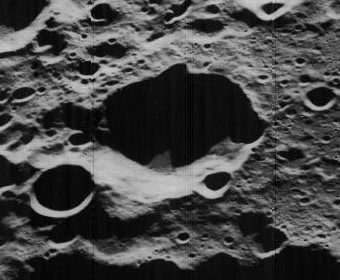

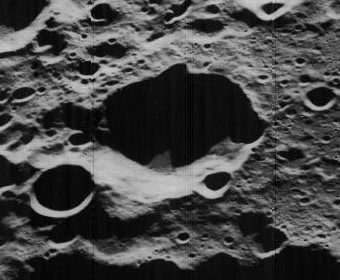

The same month, JPL held an open access event to mark the 32nd anniversary of its foundation—which featured a "nativity scene" of mannequins reconstructing the November 1936 photograph of the GALCIT Group—and erected a monument commemorating their first rocket test on Halloween 1936. Among the aerospace industry, JPL was nicknamed as standing for "Jack Parsons' Laboratory" or "Jack Parsons Lives". The International Astronomical Union decided to name a crater on the far side (Moon), far side of the Moon Parsons (crater), Parsons after him in 1972. JPL later credited him for making "distinctive technical innovations that advanced early efforts" in rocket engineering, with aerospace journalist Craig Covault stating that the work of Parsons, Qian Xuesen and the GALCIT Group "planted the seeds for JPL to become preeminent in space and rocketry."

Many of Parsons' writings were posthumously published as ''Freedom is a Two-Edged Sword'' in 1989, a compilation co-edited by Cameron and O.T.O. leader Hymenaeus Beta, which incited a resurgence of interest in Parsons within occult and countercultural circles. For example, comic book artist and occultist Alan Moore noted Parsons as a creative influence in a 1998 interview with Clifford Meth. The Cameron-Parsons Foundation was founded as an incorporated company in 2006, with the intention of conserving and promoting Parsons' writings and Cameron's artwork, and in 2014 Fulger Esoterica published ''Songs for the Witch Woman''—a limited edition book of poems by Parsons with illustrations by Cameron, released to coincide with his centenary. An exhibition of the same name was held at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.

In 1999, Feral House published the biography ''Sex and Rockets: The Occult World of Jack Parsons'' by John Carter, who opined that Parsons had accomplished more in under five years of research than Robert H. Goddard had in his lifetime, and said that his role in the development of rocket technology had been neglected by historians of science; Carter thought that Parsons' abilities and accomplishments as an occultist had been overestimated and exaggerated among Western esotericists, emphasizing his disowning by Crowley for practicing magic beyond his grade. Feral House republished the work as a new edition in 2004, accompanied with an introduction by Robert Anton Wilson. Wilson believed that Parsons was "the one single individual who contributed the most to rocket science", describing him as being "very strange, very brilliant, very funny, [and] very tormented", and considering it noteworthy that the day of Parsons' birth was the predicted beginning of the apocalypse advocated by Charles Taze Russell, the founder of the Bible Student movement.

In 2005, Weidenfeld & Nicolson published ''Strange Angel: The Otherworldly Life of Rocket Scientist John Whiteside Parsons'' by George Pendle, who described Parsons as "the Che Guevara of occultism". Pendle said that although Parsons "would not live to see his dream of space travel come true, he was essential to making it a reality." Pendle considered that the cultural stigma attached to Parsons' occultism was the primary cause of his low public profile, noting that "Like many scientific mavericks, Parsons was eventually discarded by the establishment once he had served his purpose." It was this unorthodox mindset, creatively facilitated by his science fiction fandom and "willingness to believe in magic's efficacy", Pendle argued, "that allowed him to break scientific barriers previously thought to be indestructible"—commenting that Parsons "saw both space and magic as ways of exploring these new frontiers—one breaking free from Earth literally and metaphysically."

L. Ron Hubbard's role in Parsons' Agape Lodge and the ensuing yacht scam were explored in Russell Miller's 1987 Hubbard biography ''Bare-faced Messiah''. Parsons' involvement in the Agape Lodge was also discussed by Martin P. Starr in his history of the American Thelemite movement, ''The Unknown God: W.T. Smith and the Thelemites'', published by Teitan Press in 2003. ''The QI Book of the Dead'' (2004), based on QI, the BBC game show, included a Parsons obituary. Parsons' occult partnership with Hubbard was also mentioned in Alex Gibney's 2015 documentary film ''Going Clear (film), Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief'', produced by HBO.

Before his death, Parsons appeared in science fiction writer Anthony Boucher's murder-mystery novel ''Rocket to the Morgue'' (1942) under the guise of mad scientist character Hugo Chantrelle. Another fictional character based on Parsons was Courtney James, a wealthy socialite who features in L. Sprague de Camp's 1956 short time travel story ''A Gun for Dinosaur''. In 2005, ''Pasadena Babalon'', a stage play about Parsons written by George D. Morgan and directed by Brian Brophy, premiered at Caltech as a production by its theater Arts Group in 2010, the same year Cellar Door Publishing released Richard Carbonneau and Robin Simon Ng's graphic novel, ''The Marvel: A Biography of Jack Parsons''.

Parsons' mythology was incorporated into the narrative of David Lynch's mystery-horror television series ''Twin Peaks''. In 2014, AMC Networks announced plans for a serial television dramatization of Parsons' life, but in 2016 it was reported that the series "will not be going forward." In 2017, the project was adopted as a web television series by CBS All Access. ''Strange Angel'', produced by Mark Heyman and starring Irish actor Jack Reynor as Parsons, premiered in June 2018 and ran for two seasons. In 2018, Parsons was featured in an episode of the Amazon series ''Lore (TV series), Lore''.

Parsons is the subject of musical tributes by Jóhann Jóhannsson, Johan Johannson (''Fordlandia (album), Fordlandia'', 2008), Six Organs of Admittance (''Parsons' Blues'', 2012), The Claypool Lennon Delirium (''South of Reality'', 2019), and Luke Haines and Peter Buck (''Beat Poetry for Survivalists'', 2020).

The same month, JPL held an open access event to mark the 32nd anniversary of its foundation—which featured a "nativity scene" of mannequins reconstructing the November 1936 photograph of the GALCIT Group—and erected a monument commemorating their first rocket test on Halloween 1936. Among the aerospace industry, JPL was nicknamed as standing for "Jack Parsons' Laboratory" or "Jack Parsons Lives". The International Astronomical Union decided to name a crater on the far side (Moon), far side of the Moon Parsons (crater), Parsons after him in 1972. JPL later credited him for making "distinctive technical innovations that advanced early efforts" in rocket engineering, with aerospace journalist Craig Covault stating that the work of Parsons, Qian Xuesen and the GALCIT Group "planted the seeds for JPL to become preeminent in space and rocketry."

Many of Parsons' writings were posthumously published as ''Freedom is a Two-Edged Sword'' in 1989, a compilation co-edited by Cameron and O.T.O. leader Hymenaeus Beta, which incited a resurgence of interest in Parsons within occult and countercultural circles. For example, comic book artist and occultist Alan Moore noted Parsons as a creative influence in a 1998 interview with Clifford Meth. The Cameron-Parsons Foundation was founded as an incorporated company in 2006, with the intention of conserving and promoting Parsons' writings and Cameron's artwork, and in 2014 Fulger Esoterica published ''Songs for the Witch Woman''—a limited edition book of poems by Parsons with illustrations by Cameron, released to coincide with his centenary. An exhibition of the same name was held at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.

In 1999, Feral House published the biography ''Sex and Rockets: The Occult World of Jack Parsons'' by John Carter, who opined that Parsons had accomplished more in under five years of research than Robert H. Goddard had in his lifetime, and said that his role in the development of rocket technology had been neglected by historians of science; Carter thought that Parsons' abilities and accomplishments as an occultist had been overestimated and exaggerated among Western esotericists, emphasizing his disowning by Crowley for practicing magic beyond his grade. Feral House republished the work as a new edition in 2004, accompanied with an introduction by Robert Anton Wilson. Wilson believed that Parsons was "the one single individual who contributed the most to rocket science", describing him as being "very strange, very brilliant, very funny, [and] very tormented", and considering it noteworthy that the day of Parsons' birth was the predicted beginning of the apocalypse advocated by Charles Taze Russell, the founder of the Bible Student movement.

In 2005, Weidenfeld & Nicolson published ''Strange Angel: The Otherworldly Life of Rocket Scientist John Whiteside Parsons'' by George Pendle, who described Parsons as "the Che Guevara of occultism". Pendle said that although Parsons "would not live to see his dream of space travel come true, he was essential to making it a reality." Pendle considered that the cultural stigma attached to Parsons' occultism was the primary cause of his low public profile, noting that "Like many scientific mavericks, Parsons was eventually discarded by the establishment once he had served his purpose." It was this unorthodox mindset, creatively facilitated by his science fiction fandom and "willingness to believe in magic's efficacy", Pendle argued, "that allowed him to break scientific barriers previously thought to be indestructible"—commenting that Parsons "saw both space and magic as ways of exploring these new frontiers—one breaking free from Earth literally and metaphysically."

L. Ron Hubbard's role in Parsons' Agape Lodge and the ensuing yacht scam were explored in Russell Miller's 1987 Hubbard biography ''Bare-faced Messiah''. Parsons' involvement in the Agape Lodge was also discussed by Martin P. Starr in his history of the American Thelemite movement, ''The Unknown God: W.T. Smith and the Thelemites'', published by Teitan Press in 2003. ''The QI Book of the Dead'' (2004), based on QI, the BBC game show, included a Parsons obituary. Parsons' occult partnership with Hubbard was also mentioned in Alex Gibney's 2015 documentary film ''Going Clear (film), Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief'', produced by HBO.

Before his death, Parsons appeared in science fiction writer Anthony Boucher's murder-mystery novel ''Rocket to the Morgue'' (1942) under the guise of mad scientist character Hugo Chantrelle. Another fictional character based on Parsons was Courtney James, a wealthy socialite who features in L. Sprague de Camp's 1956 short time travel story ''A Gun for Dinosaur''. In 2005, ''Pasadena Babalon'', a stage play about Parsons written by George D. Morgan and directed by Brian Brophy, premiered at Caltech as a production by its theater Arts Group in 2010, the same year Cellar Door Publishing released Richard Carbonneau and Robin Simon Ng's graphic novel, ''The Marvel: A Biography of Jack Parsons''.

Parsons' mythology was incorporated into the narrative of David Lynch's mystery-horror television series ''Twin Peaks''. In 2014, AMC Networks announced plans for a serial television dramatization of Parsons' life, but in 2016 it was reported that the series "will not be going forward." In 2017, the project was adopted as a web television series by CBS All Access. ''Strange Angel'', produced by Mark Heyman and starring Irish actor Jack Reynor as Parsons, premiered in June 2018 and ran for two seasons. In 2018, Parsons was featured in an episode of the Amazon series ''Lore (TV series), Lore''.

Parsons is the subject of musical tributes by Jóhann Jóhannsson, Johan Johannson (''Fordlandia (album), Fordlandia'', 2008), Six Organs of Admittance (''Parsons' Blues'', 2012), The Claypool Lennon Delirium (''South of Reality'', 2019), and Luke Haines and Peter Buck (''Beat Poetry for Survivalists'', 2020).

chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe th ...

, and Thelemite

Thelema () is a Western esoteric and occult social or spiritual philosophy and new religious movement founded in the early 1900s by Aleister Crowley (1875–1947), an English writer, mystic, occultist, and ceremonial magician. The word ...

occult

The occult, in the broadest sense, is a category of esoteric supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving otherworldly agency, such as magic and mysticism a ...

ist. Associated with the California Institute of Technology

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech or CIT)The university itself only spells its short form as "Caltech"; the institution considers other spellings such a"Cal Tech" and "CalTech" incorrect. The institute is also occasional ...

(Caltech), Parsons was one of the principal founders of both the Jet Propulsion Laboratory

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) is a Federally funded research and development centers, federally funded research and development center and NASA field center in the City of La Cañada Flintridge, California, La Cañada Flintridge, California ...

(JPL) and the Aerojet Engineering Corporation. He invented the first rocket engine

A rocket engine uses stored rocket propellants as the reaction mass for forming a high-speed propulsive jet of fluid, usually high-temperature gas. Rocket engines are reaction engines, producing thrust by ejecting mass rearward, in accorda ...

to use a castable

In materials science, a refractory material or refractory is a material that is resistant to decomposition by heat, pressure, or chemical attack, and retains strength and form at high temperatures. Refractories are polycrystalline, polyphase ...

, composite

Composite or compositing may refer to:

Materials

* Composite material, a material that is made from several different substances

** Metal matrix composite, composed of metal and other parts

** Cermet, a composite of ceramic and metallic materials ...

rocket propellant

Rocket propellant is the reaction mass of a rocket. This reaction mass is ejected at the highest achievable velocity from a rocket engine to produce thrust. The energy required can either come from the propellants themselves, as with a chemic ...

, and pioneered the advancement of both liquid-fuel and solid-fuel rockets.

Born in Los Angeles, Parsons was raised by a wealthy family on Orange Grove Boulevard

Orange Grove Boulevard is a main thoroughfare in Pasadena and South Pasadena, California. Each New Year's Day, the Rose Parade participants and floats line up before dawn on Orange Grove Boulevard, facing north, for the beginning of the parade. So ...

in Pasadena. Inspired by science fiction literature

Science fiction (sometimes shortened to Sci-Fi or SF) is a genre of speculative fiction which typically deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts such as advanced science and technology, space exploration, time travel, parallel u ...

, he developed an interest in rocketry in his childhood and in 1928 began amateur rocket experiments with school friend Edward S. Forman. He dropped out of Pasadena Junior College

Pasadena City College (PCC) is a public community college in Pasadena, California.

History

Pasadena City College was founded in 1924 as Pasadena Junior College. From 1928 to 1953, it operated as a four-year junior college, combining the las ...

and Stanford University

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is conside ...

due to financial difficulties during the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, and in 1934 he united with Forman and graduate Frank Malina

Frank Joseph Malina (October 2, 1912 — November 9, 1981) was an American aeronautical engineer and painter, especially known for becoming both a pioneer in the art world and the realm of scientific engineering.

Early life

Malina was born in B ...

to form the Caltech-affiliated Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory (GALCIT) Rocket Research Group, supported by GALCIT chairman Theodore von Kármán

Theodore von Kármán ( hu, ( szőllőskislaki) Kármán Tódor ; born Tivadar Mihály Kármán; 11 May 18816 May 1963) was a Hungarian-American mathematician, aerospace engineer, and physicist who was active primarily in the fields of aeronaut ...

. In 1939 the GALCIT Group gained funding from the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nat ...

(NAS) to work on Jet-Assisted Take Off (JATO) for the U.S. military. After the U.S. entered World War II, they founded Aerojet in 1942 to develop and sell JATO technology; the GALCIT Group became JPL in 1943.

Following some brief involvement with Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

in 1939, Parsons converted to Thelema

Thelema () is a Western esoteric and occult social or spiritual philosophy and new religious movement founded in the early 1900s by Aleister Crowley (1875–1947), an English writer, mystic, occultist, and ceremonial magician. The word ' ...

, the new religious movement

A new religious movement (NRM), also known as alternative spirituality or a new religion, is a religious or Spirituality, spiritual group that has modern origins and is peripheral to its society's dominant religious culture. NRMs can be novel in ...

founded by the English occultist Aleister Crowley

Aleister Crowley (; born Edward Alexander Crowley; 12 October 1875 – 1 December 1947) was an English occultist, ceremonial magician, poet, painter, novelist, and mountaineer. He founded the religion of Thelema, identifying himself as the pr ...

. Together with his first wife, Helen Northrup, Parsons joined the Agape Lodge, the Californian branch of the Thelemite Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O.) in 1941. At Crowley's bidding, Parsons replaced Wilfred Talbot Smith

Wilfred Talbot Smith (born Frank Wenham; 8 June 1885 – 27 April 1957) was an English occultist and ceremonial magician known as a prominent advocate of the religion of Thelema. Living most of his life in North America, he played a key role in ...

as its leader in 1942 and ran the Lodge from his mansion on Orange Grove Boulevard. Parsons was expelled from JPL and Aerojet in 1944 owing to the Lodge's infamous reputation and his hazardous workplace conduct.

In 1945, Parsons separated from Helen, after having an affair with her sister Sara

Sara may refer to:

Arts, media and entertainment Film and television

* ''Sara'' (1992 film), 1992 Iranian film by Dariush Merhjui

* ''Sara'' (1997 film), 1997 Polish film starring Bogusław Linda

* ''Sara'' (2010 film), 2010 Sri Lankan Sinhal ...

; when Sara left him for L. Ron Hubbard

Lafayette Ronald Hubbard (March 13, 1911 – January 24, 1986) was an American author, primarily of science fiction and fantasy stories, who is best known for having founded the Church of Scientology. In 1950, Hubbard authored '' Dianetic ...

, Parsons conducted the Babalon Working

The Babalon Working was a series of magic ceremonies or rituals performed from January to March 1946 by author, pioneer rocket-fuel scientist and occultist Jack Parsons and Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard. This ritual was essentially designe ...

, a series of rituals intended to invoke the Thelemic goddess Babalon

Babalon (also known as the Scarlet Woman, Great Mother or Mother of Abominations) is a goddess found in the occult system of Thelema, which was established in 1904 with the writing of '' The Book of the Law'' by English author and occultist ...

on Earth. He and Hubbard continued the working with Marjorie Cameron, whom Parsons married in 1946. After Hubbard and Sara defrauded him of his life savings, Parsons resigned from the O.T.O., then held various jobs while acting as a consultant for Israel's rocket program. Amid McCarthyism

McCarthyism is the practice of making false or unfounded accusations of subversion and treason, especially when related to anarchism, communism and socialism, and especially when done in a public and attention-grabbing manner.

The term origin ...

, Parsons was accused of espionage and left unable to work in rocketry. In 1952, Parsons died at the age of 37 in a home laboratory explosion that attracted national media attention; the police ruled it an accident, but many associates suspected suicide or murder.

Parsons's libertarian

Libertarianism (from french: libertaire, "libertarian"; from la, libertas, "freedom") is a political philosophy that upholds liberty as a core value. Libertarians seek to maximize autonomy and political freedom, and minimize the state's en ...

and occult writings were published posthumously. Historians of Western esoteric tradition cite him as one of the more prominent figures in propagating Thelema across North America. Although academic interest in his scientific career was negligible, historians have come to recognize Parsons's contributions to rocket engineering. For these innovations, his advocacy of space exploration

Space exploration is the use of astronomy and space technology to explore outer space. While the exploration of space is carried out mainly by astronomers with telescopes, its physical exploration though is conducted both by uncrewed robo ...

and human spaceflight

Human spaceflight (also referred to as manned spaceflight or crewed spaceflight) is spaceflight with a crew or passengers aboard a spacecraft, often with the spacecraft being operated directly by the onboard human crew. Spacecraft can also be ...

, and his role in founding JPL and Aerojet, Parsons is regarded as among the most important figures in the history of the U.S. space program. He has been the subject of several biographies and fictionalized portrayals.

Biography

Early life: 1914–1934

Marvel Whiteside Parsons was born on October 2, 1914, at the Good Samaritan Hospital in Los Angeles. His parents, Ruth Virginia Whiteside (''c.'' 1893–1952) and Marvel H. Parsons (''c.'' 1894–1947), had moved to California from Massachusetts the previous year, purchasing a house on Scarff Street in downtown Los Angeles. Their son was his father's namesake, but was known in the household as Jack. The marriage broke down soon after Jack's birth, when Ruth discovered that his father had made numerous visits to a prostitute, and she filed for divorce in March 1915. Jack's father returned to Massachusetts after being publicly exposed as an adulterer, with Ruth forbidding him from having any contact with Jack. His father later joined the armed forces, reaching the rank of major, and married a woman with whom he had a son, Charles, a half-brother Jack only met once. Although she retained her ex-husband's surname, Ruth started calling her son John, but many friends throughout his life knew him as Jack. Ruth's parents Walter and Carrie Whiteside moved to California to be with Jack and their daughter, using their wealth to buy an upscale house on Orange Grove Boulevard in Pasadena—known locally as "Millionaire's Mile"—where they could live together. Jack was surrounded by domestic servants. Having few friends, he lived a solitary childhood and spent much time reading; he took a particular interest in works of mythology,Arthurian legend

The Matter of Britain is the body of medieval literature and legendary material associated with Great Britain and Brittany and the legendary kings and heroes associated with it, particularly King Arthur. It was one of the three great Wester ...

, and the ''Arabian Nights

''One Thousand and One Nights'' ( ar, أَلْفُ لَيْلَةٍ وَلَيْلَةٌ, italic=yes, ) is a collection of Middle Eastern folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age. It is often known in English as the ''Arabian ...

''. Through the works of Jules Verne

Jules Gabriel Verne (;''Longman Pronunciation Dictionary''. ; 8 February 1828 – 24 March 1905) was a French novelist, poet, and playwright. His collaboration with the publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel led to the creation of the '' Voyages extra ...

he became interested in science fiction

Science fiction (sometimes shortened to Sci-Fi or SF) is a genre of speculative fiction which typically deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts such as advanced science and technology, space exploration, time travel, parallel uni ...

and a keen reader of pulp magazine

Pulp magazines (also referred to as "the pulps") were inexpensive fiction magazines that were published from 1896 to the late 1950s. The term "pulp" derives from the cheap wood pulp paper on which the magazines were printed. In contrast, magazine ...

s like ''Amazing Stories

''Amazing Stories'' is an American science fiction magazine launched in April 1926 by Hugo Gernsback's Experimenter Publishing. It was the first magazine devoted solely to science fiction. Science fiction stories had made regular appearances ...

'', which led to his early interest in rocket

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entir ...

ry.

At age 12 Parsons began attending Washington Junior High School, where he performed poorly—which biographer George Pendle

George Pendle (born 1976) is a British author and journalist. He was educated at Stowe School and St Peter's College, Oxford.

After working at '' The Times'' from 1997 to 2001, Pendle wrote his first book, ''Strange Angel: The Otherworldly Life ...

attributed to undiagnosed dyslexia

Dyslexia, also known until the 1960s as word blindness, is a disorder characterized by reading below the expected level for one's age. Different people are affected to different degrees. Problems may include difficulties in spelling words, r ...

—and was bullied for his upper-class status and perceived effeminacy. Although unpopular, he formed a strong friendship with Edward Forman, a boy from a poor working-class family who defended him from bullies and shared his interest in science fiction and rocketry, with the well-read Parsons enthralling Forman with his literary prowess. In 1928 the pair—adopting the Latin motto '' per aspera ad astra'' (''through hardship to the stars'')—began engaging in homemade gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). T ...

-based rocket experiments in the nearby Arroyo Seco canyon, as well as the Parsons family's back garden, which left it pockmarked with craters from explosive test failures. They incorporated commonly available fireworks such as cherry bombs into their rockets, and Parsons suggested using glue as a binding agent to increase the rocket fuel's stability. This research became more complex when they began using materials such as aluminium foil

Aluminium foil (or aluminum foil in North American English; often informally called tin foil) is aluminium prepared in thin metal leaves with a thickness less than ; thinner gauges down to are also commonly used. Standard household foil is typ ...

to make the gunpowder easier to cast. Parsons had also begun to investigate occultism

The occult, in the broadest sense, is a category of esoteric supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving otherworldly agency, such as magic and mysticism a ...

, and performed a ritual intended to invoke the Devil into his bedroom; he worried that the invocation was successful and was frightened into ceasing these activities. In 1929 he began attending John Muir High School

John Muir High School is a four-year comprehensive secondary school in Pasadena, California, United States and is a part of the Pasadena Unified School District. The school is named after preservationist John Muir.

History

In 1926 the Pasadena ...

, where he maintained an insular friendship with Forman and was a keen participant in fencing

Fencing is a group of three related combat sports. The three disciplines in modern fencing are the foil, the épée, and the sabre (also ''saber''); winning points are made through the weapon's contact with an opponent. A fourth discipline, ...

and archery

Archery is the sport, practice, or skill of using a bow to shoot arrows.Paterson ''Encyclopaedia of Archery'' p. 17 The word comes from the Latin ''arcus'', meaning bow. Historically, archery has been used for hunting and combat. In ...

. After he received poor school results, Parsons's mother sent him away to study at the Brown Military Academy for Boys, a private boarding school in San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United States ...

, but he was expelled for blowing up the toilets.

The Parsons family spent mid-1929 touring Europe before returning to Pasadena, where they moved into a house on San Rafael Avenue. With the onset of the

The Parsons family spent mid-1929 touring Europe before returning to Pasadena, where they moved into a house on San Rafael Avenue. With the onset of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

their fortune began to dwindle, and in July 1931 Jack's grandfather Walter died. Parsons began studying at the privately run University School, a liberal institution that took an unconventional approach to teaching. He flourished academically, becoming editor of the school newspaper, ''El Universitano'', and winning an award for literary excellence; teachers who had trained at the nearby California Institute of Technology

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech or CIT)The university itself only spells its short form as "Caltech"; the institution considers other spellings such a"Cal Tech" and "CalTech" incorrect. The institute is also occasional ...

(Caltech) honed his attention on the study of chemistry. With the family's financial difficulties deepening, Parsons began working on weekends and school holidays at the Hercules Powder Company

Hercules, Inc. was a chemical and munitions manufacturing company based in Wilmington, Delaware, United States, incorporated in 1912 as the Hercules Powder Company following the breakup of the DuPont explosives monopoly by the U.S. Circuit C ...

, where he learned more about explosives and their potential use in rocket propulsion. He and Forman continued to independently explore the subject in their spare time, building and testing different rockets, sometimes with materials that Parsons had stolen from work. Parsons soon constructed a solid-fuel rocket engine

A rocket engine uses stored rocket propellants as the reaction mass for forming a high-speed propulsive jet of fluid, usually high-temperature gas. Rocket engines are reaction engines, producing thrust by ejecting mass rearward, in accorda ...

, and with Forman corresponded with pioneer rocket engineers including Robert H. Goddard, Hermann Oberth

Hermann Julius Oberth (; 25 June 1894 – 28 December 1989) was an Austro-Hungarian-born German physicist and engineer. He is considered one of the founding fathers of rocketry and astronautics, along with Robert Esnault-Pelterie, Konstantin ...

, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky

Konstantin Eduardovich Tsiolkovsky (russian: Константи́н Эдуа́рдович Циолко́вский , , p=kənstɐnʲˈtʲin ɪdʊˈardəvʲɪtɕ tsɨɐlˈkofskʲɪj , a=Ru-Konstantin Tsiolkovsky.oga; – 19 September 1935) ...

, Willy Ley

Willy or Willie is a masculine, male given name, often a diminutive form of William (given name), William or Wilhelm (name), Wilhelm, and occasionally a nickname. It may refer to:

People Given name or nickname

* Willie Aames (born 1960), American ...

and Wernher von Braun

Wernher Magnus Maximilian Freiherr von Braun ( , ; 23 March 191216 June 1977) was a German and American aerospace engineer and space architect. He was a member of the Nazi Party and Allgemeine SS, as well as the leading figure in the develop ...

. Parsons and von Braun had hours of telephone conversations about rocketry in their respective countries as well as their own research.

Parsons graduated from University School in 1933, and moved with his mother and grandmother to a more modest house on St. John Avenue, where he continued to pursue his interests in literature and poetry. He enrolled in Pasadena Junior College

Pasadena City College (PCC) is a public community college in Pasadena, California.

History

Pasadena City College was founded in 1924 as Pasadena Junior College. From 1928 to 1953, it operated as a four-year junior college, combining the las ...

with the hope of earning an associate degree

An associate degree is an undergraduate degree awarded after a course of post-secondary study lasting two to three years. It is a level of qualification above a high school diploma, GED, or matriculation, and below a bachelor's degree.

Th ...

in physics and chemistry, but dropped out after one term because of his financial situation and took up permanent employment at the Hercules Powder Company. His employers then sent him to work at their manufacturing plant in Hercules, California

Hercules is a city in western Contra Costa County, California. Situated along the coast of San Pablo Bay, it is located in the eastern region of the San Francisco Bay Area, about north of Berkeley, California. As of 2010, its population was 24, ...

on San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay is a large tidal estuary in the U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the big cities of San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland.

San Francisco Bay drains water f ...

, where he earned a relatively high monthly wage of $100; he was plagued by headaches caused by exposure to nitroglycerin

Nitroglycerin (NG), (alternative spelling of nitroglycerine) also known as trinitroglycerin (TNG), nitro, glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), or 1,2,3-trinitroxypropane, is a dense, colorless, oily, explosive liquid most commonly produced by nitrating g ...

. He saved money in hopes of continuing his academic studies and began a degree in chemistry at Stanford University

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is conside ...

, but found the tuition unaffordable and returned to Pasadena.

GALCIT Rocket Research Group and the Kynette trial: 1934–1938

In hopes of gaining access to the state-of-the-art resources of Caltech for their rocketry research, Parsons and Forman attended a lecture on the work of Austrian rocket engineer

In hopes of gaining access to the state-of-the-art resources of Caltech for their rocketry research, Parsons and Forman attended a lecture on the work of Austrian rocket engineer Eugen Sänger

Eugen Sänger (22 September 1905 – 10 February 1964) was an Austrian aerospace engineer best known for his contributions to lifting body and ramjet technology.

Early career

Sänger was born in the former mining town of Preßnitz (Přísečni ...

and hypothetical above-stratospheric

The stratosphere () is the second layer of the atmosphere of the Earth, located above the troposphere and below the mesosphere. The stratosphere is an atmospheric layer composed of stratified temperature layers, with the warm layers of air h ...

aircraft by the institute's William Bollay

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Eng ...

—a PhD student specializing in rocket-powered aircraft

A rocket-powered aircraft or rocket plane is an aircraft that uses a rocket engine for propulsion, sometimes in addition to airbreathing jet engines. Rocket planes can achieve much higher speeds than similarly sized jet aircraft, but typicall ...

—and approached him to express their interest in designing a liquid-fuel rocket motor. Bollay redirected them to another PhD student, Frank Malina

Frank Joseph Malina (October 2, 1912 — November 9, 1981) was an American aeronautical engineer and painter, especially known for becoming both a pioneer in the art world and the realm of scientific engineering.

Early life

Malina was born in B ...

, a mathematician and mechanical engineer writing a thesis on rocket propulsion who shared their interests and soon befriended them. Parsons, Forman, and Malina applied for funding from Caltech together; they did not mention that their ultimate objective was to develop rockets for space exploration, realizing that most of the scientific establishment then considered such ideas science fiction. Caltech's Clark Blanchard Millikan

Clark Blanchard Millikan (August 23, 1903 – January 2, 1966) was a distinguished professor of aeronautics at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), and a founding member of the National Academy of Engineering.

Biography

Millikan's par ...

immediately rebuffed them, but Malina's doctoral advisor Theodore von Kármán

Theodore von Kármán ( hu, ( szőllőskislaki) Kármán Tódor ; born Tivadar Mihály Kármán; 11 May 18816 May 1963) was a Hungarian-American mathematician, aerospace engineer, and physicist who was active primarily in the fields of aeronaut ...

saw more promise in their proposal and agreed to allow them to operate under the auspices of the university's Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory (GALCIT). Naming themselves the GALCIT Rocket Research Group, they gained access to Caltech's specialist equipment, though the economics of the Great Depression left von Kármán unable to finance them.

The trio focused their distinct skills on collaborative rocket development; Parsons was the chemist, Forman the machinist, and Malina the technical theoretician. Malina wrote in 1968 that the self-educated Parsons "lacked the discipline of a formal higher education, uthad an uninhibited and fruitful imagination." Parsons and Forman who, as described by Geoffrey A. Landis

Geoffrey Alan Landis (; born May 28, 1955) is an American aerospace engineer and author, working for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) on planetary exploration, interstellar propulsion, solar power and photovoltaics. He h ...

, "were eager to try whatever idea happened to spring to mind", contrasted with Malina, who insisted on scientific discipline as informed by von Kármán. Landis writes that their creativity "kept Malina focused toward building actual rocket engines, not just solving equations on paper". Sharing socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

values, they operated on an egalitarian

Egalitarianism (), or equalitarianism, is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds from the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all hu ...

basis; Malina taught the others about scientific procedure and they taught him about the practical elements of rocketry. They often socialized, smoking marijuana

Cannabis, also known as marijuana among other names, is a psychoactive drug from the cannabis plant. Native to Central or South Asia, the cannabis plant has been used as a drug for both recreational and entheogenic purposes and in various t ...

and drinking, while Malina and Parsons set about writing a semiautobiographical science fiction screenplay they planned to pitch to Hollywood with strong anti-capitalist

Anti-capitalism is a political ideology and movement encompassing a variety of attitudes and ideas that oppose capitalism. In this sense, anti-capitalists are those who wish to replace capitalism with another type of economic system, such as so ...

and pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campai ...

themes.

Parsons met Helen Northrup at a local church dance and proposed marriage in July 1934. She accepted and they were married in April 1935 at the Little Church of the Flowers in

Parsons met Helen Northrup at a local church dance and proposed marriage in July 1934. She accepted and they were married in April 1935 at the Little Church of the Flowers in Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale

Forest Lawn Memorial Park is a privately owned cemetery in Glendale, California. It is the original and current flagship location of Forest Lawn Memorial-Parks & Mortuaries, a chain of six cemeteries and four additional mortuaries in Southern Cal ...

, before undertaking a brief honeymoon in San Diego. They moved into a house on South Terrace Drive, Pasadena, while Parsons got a job at the explosives manufacturer Halifax Powder Company's facility in Saugus. Much to Helen's dismay, Parsons spent most of his wages funding the GALCIT Rocket Research Group. For extra money, he manufactured nitroglycerin in their home, constructing a laboratory on their front porch. At one point, he pawned Helen's engagement ring, and he often asked her family for loans.

Malina recounted that "Parsons and Forman were not too pleased with an austere program that did not include at least the launching of model rockets", but the Group reached the consensus of developing a working static rocket motor before embarking on more complex research. They contacted liquid-fuel rocket

A liquid-propellant rocket or liquid rocket utilizes a rocket engine that uses liquid propellants. Liquids are desirable because they have a reasonably high density and high specific impulse (''I''sp). This allows the volume of the propellant ta ...

pioneer Robert H. Goddard and he invited Malina to his facility in Roswell, New Mexico

Roswell () is a city in, and the seat of, Chaves County in the U.S. state of New Mexico. Chaves County forms the entirety of the Roswell micropolitan area. As of the 2020 census it had a population of 48,422, making it the fifth-largest city ...

, but he was not interested in cooperating—reticent about sharing his research and having been subjected to widespread derision for his work in rocketry. They were instead joined by Caltech graduate students Apollo M. O. "Amo" Smith, Carlos C. Wood, Mark Muir Mills, Fred S. Miller, William C. Rockefeller, and Rudolph Schott; Schott's pickup truck transported their equipment. Their first liquid-fuel motor test took place near the Devil's Gate Dam in the Arroyo Seco on Halloween 1936. Parsons's biographer John Carter described the layout of the contraption as showing

Three attempts to fire the rocket failed; on the fourth the oxygen line accidentally ignited and perilously billowed fire at the Group, but they viewed this experience as formative. They continued their experiments throughout the last quarter of 1936; after the final test was successfully completed in January 1937 von Kármán agreed that they could perform future experiments at an exclusive rocket testing facility on campus.

In April 1937, Caltech mathematician

In April 1937, Caltech mathematician Qian Xuesen

Qian Xuesen, or Hsue-Shen Tsien (; 11 December 1911 – 31 October 2009), was a Chinese mathematician, cyberneticist, aerospace engineer, and physicist who made significant contributions to the field of aerodynamics and established engineering ...

joined the Group. Several months later, Weld Arnold, a Caltech laboratory assistant who worked as the Group's official photographer, also joined. The main reason for Arnold's appointment to this position was his provision of a donation to the Group on behalf of an anonymous benefactor. They became well known on campus as the "Suicide Squad" for the dangerous nature of some of their experiments and attracted attention from the local press. Parsons himself gained further media publicity when he appeared as an expert explosives witness in the trial of Captain Earl Kynette, the head of police intelligence in Los Angeles who was accused of conspiring to set a car bomb

A car bomb, bus bomb, lorry bomb, or truck bomb, also known as a vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (VBIED), is an improvised explosive device designed to be detonated in an automobile or other vehicles.

Car bombs can be roughly divided ...

in the attempted murder of private investigator Harry Raymond, a former LAPD detective who was fired after whistleblowing against police corruption. When Kynette was convicted largely on Parsons' testimony, which included his forensic reconstruction of the car bomb and its explosion, his identity as an expert scientist in the public eye was established despite his lack of a university education. While working at Caltech, Parsons was admitted to evening courses in chemistry at the University of Southern California

, mottoeng = "Let whoever earns the palm bear it"

, religious_affiliation = Nonsectarian—historically Methodist

, established =

, accreditation = WSCUC

, type = Private research university

, academic_affiliations =

, endowment = $8.1 ...

(USC), but distracted by his GALCIT workload he attended sporadically and received unexceptional grades.

By early 1938, the Group had made their static rocket motor, which originally burned for three seconds, run for over a minute. In May that year, Parsons was invited by Forrest J Ackerman

Forrest James Ackerman (November 24, 1916 – December 4, 2008) was an American magazine editor; science fiction writer and literary agent; a founder of science fiction fandom; a leading expert on science fiction, horror, and fantasy films; a pr ...

to lecture on his rocketry work at Chapter Number 4 of the Los Angeles Science Fiction League (LASFL). Although he never joined the society, he occasionally attended their talks, on one occasion conversing with a teenage Ray Bradbury

Ray Douglas Bradbury (; August 22, 1920June 5, 2012) was an American author and screenwriter. One of the most celebrated 20th-century American writers, he worked in a variety of modes, including fantasy, science fiction, horror, mystery, and ...

. Another scientist to become involved in the GALCIT project was Sidney Weinbaum, a Jewish refugee from Europe who was a vocal Marxist; he led Parsons, Malina, and Qian in their creation of a largely secretive communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

discussion group at Caltech, which became known as Professional Unit 122 of the Pasadena Communist Party. Although Parsons subscribed to the '' People's Daily World'' and joined the American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1920 "to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States". T ...

(ACLU), he refused to join the American Communist Party

The Communist Party USA, officially the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), is a communist party in the United States which was established in 1919 after a split in the Socialist Party of America following the Russian Revo ...

, causing a break in his and Weinbaum's friendship. This, coupled with the need to focus on paid employment, led to the disintegration of much of the Rocket Research Group, leaving only its three founding members by late 1938.

Embracing Thelema; advancing JATO and foundation of Aerojet: 1939–1942

In January 1939, John and Frances Baxter, a brother and sister who had befriended Jack and Helen Parsons, took Jack to the Church of Thelema on Winona Boulevard, Hollywood, where he witnessed the performance ofThe Gnostic Mass

Aleister Crowley wrote The Gnostic Mass — technically called Liber XV or "Book 15" — in 1913 while travelling in Moscow, Russia. The structure is similar to the Mass of the Eastern Orthodox Church and Roman Catholic Church, communica ...

. Celebrants of the church had included Hollywood actor John Carradine

John Carradine ( ; born Richmond Reed Carradine; February 5, 1906 – November 27, 1988) was an American actor, considered one of the greatest character actors in American cinema. He was a member of Cecil B. DeMille's stock company and later ...

and gay rights activist Harry Hay

Henry "Harry" Hay Jr. (April 7, 1912 – October 24, 2002) was an American gay rights activist, communist, and labor advocate. He was a co-founder of the Mattachine Society, the first sustained gay rights group in the United States, as well a ...

. Parsons was intrigued, having already heard of Thelema's founder and Outer Head of the Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O.), Aleister Crowley

Aleister Crowley (; born Edward Alexander Crowley; 12 October 1875 – 1 December 1947) was an English occultist, ceremonial magician, poet, painter, novelist, and mountaineer. He founded the religion of Thelema, identifying himself as the pr ...

, after reading a copy of Crowley's text '' Konx om Pax'' (1907).

Parsons was introduced to leading members Regina Kahl, Jane Wolfe

Sarah Jane Wolfe (March 21, 1875 – March 29, 1958) was an American silent film character actress who is considered an important female figure in magick. She was a friend and a colleague of Aleister Crowley and a founding member of Agape Lodg ...

, and Wilfred Talbot Smith

Wilfred Talbot Smith (born Frank Wenham; 8 June 1885 – 27 April 1957) was an English occultist and ceremonial magician known as a prominent advocate of the religion of Thelema. Living most of his life in North America, he played a key role in ...

at the mass. Feeling both "repulsion and attraction" for Smith, Parsons continued to sporadically attend the Church's events for a year. He continued to read Crowley's works, which increasingly interested him, and encouraged Helen to read them. Parsons came to believe in the reality of Thelemic magick as a force that could be explained through quantum physics

Quantum mechanics is a fundamental theory in physics that provides a description of the physical properties of nature at the scale of atoms and subatomic particles. It is the foundation of all quantum physics including quantum chemistry, qua ...

. He tried to interest his friends and acquaintances in Thelema, taking science fiction writers Jack Williamson

John Stewart Williamson (April 29, 1908 – November 10, 2006), who wrote as Jack Williamson, was an American science fiction writer, often called the "Dean of Science Fiction". He is also credited with one of the first uses of the term ''genet ...

and Cleve Cartmill

Cleve Cartmill (June 21, 1908 in Platteville, Wisconsin – February 11, 1964 in Orange County, California) was an American writer of science fiction and fantasy short stories. He is best remembered for what is sometimes referred to as "the Cl ...

to a performance of The Gnostic Mass. Although they were unimpressed, Parsons was more successful with Grady Louis McMurtry

Grady Louis McMurtry (October 18, 1918 – July 12, 1985) was a student of author and occultist Aleister Crowley and an adherent of Thelema. He is best known for reviving the fraternal organization Ordo Templi Orientis, which he headed from 197 ...

, a young Caltech student he had befriended, as well as McMurtry's fiancée Claire Palmer, and Helen's sister Sara "Betty" Northrup.

Jack and Helen were initiated into the Agape Lodge, the renamed Church of Thelema, in February 1941. Parsons adopted the Thelemic motto of ''Thelema Obtenteum Proedero Amoris Nuptiae'', a Latin mistranslation of "The establishment of Thelema through the rituals of love". The initials of this motto spelled out T.O.P.A.N., also serving as the declaration "To Pan". Commenting on Parsons' errors of translation, in jest Crowley said that "the motto which you mention is couched in a language beyond my powers of understanding". Parsons also adopted the Thelemic title ''Frater T.O.P.A.N''—with ''T.O.P.A.N'' represented in Kabbalistic

Kabbalah ( he, קַבָּלָה ''Qabbālā'', literally "reception, tradition") is an esoteric method, discipline and Jewish theology, school of thought in Jewish mysticism. A traditional Kabbalist is called a Mekubbal ( ''Məqūbbāl'' "rece ...

numerology as ''210''the name with which he frequently signed letters to occult associates—while Helen became known as ''Soror Grimaud''. Smith wrote to Crowley saying that Parsons was "a really excellent man ... He has an excellent mind and much better intellect than myself ... JP is going to be very valuable". Wolfe wrote to German O.T.O. representative Karl Germer

Karl Johannes Germer (22 January 1885 – 25 October 1962), also known as ''Frater Saturnus'', was a German occultist and the United States representative and later a successor of author and occultist Aleister Crowley as the Outer Head of the Ord ...

that Parsons was "an A1 man ... Crowleyesque in attainment as a matter of fact", and mooted Parsons as a potential successor to Crowley as Outer Head of the Order. Crowley concurred with such assessments, informing Smith that Parsons "is the most valued member of the whole Order, with no exception!"

At von Kármán's suggestion, Frank Malina

Frank Joseph Malina (October 2, 1912 — November 9, 1981) was an American aeronautical engineer and painter, especially known for becoming both a pioneer in the art world and the realm of scientific engineering.

Early life

Malina was born in B ...

approached the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nat ...

(NAS) Committee on Army Air Corps Research to request funding for research into what they referred to as "jet propulsion

Jet propulsion is the propulsion of an object in one direction, produced by ejecting a jet of fluid in the opposite direction. By Newton's third law, the moving body is propelled in the opposite direction to the jet. Reaction engines operatin ...

", a term chosen to avoid the stigma attached to rocketry. The military were interested in jet propulsion as a means of getting aircraft quickly airborne where there was insufficient room for a full-length runway, and gave the Rocket Research Group $1,000 to put together a proposal on the feasibility of Jet-Assisted Take Off (JATO) by June 1939, making Parsons et al. the first U.S. government-sanctioned rocket research group. Since their formation in 1934, they had also performed experiments involving model, black powder motor-propelled multistage rocket

A multistage rocket or step rocket is a launch vehicle that uses two or more rocket ''stages'', each of which contains its own engines and propellant. A ''tandem'' or ''serial'' stage is mounted on top of another stage; a ''parallel'' stage i ...

s. In a research paper submitted to the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

The American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) is a professional society for the field of aerospace engineering. The AIAA is the U.S. representative on the International Astronautical Federation and the International Council of ...

(AIAA), Parsons reported these rockets reaching exhaust velocities of 4,875 miles per hour, thereby demonstrating the potential of solid fuels to be more effective than the liquid types primarily preferred by researchers such as Goddard. In light of this progress, Caltech and the GALCIT Group received an additional $10,000 rocketry research grant from the AIAA.

Although a quarter of their funding went to repairing damage to Caltech buildings caused by their experiments, in June 1940 they submitted a report to the NAS in which they showed the feasibility of the project for the development of JATO and requested $100,000 to continue; they received $22,000. Now known as GALCIT Project Number 1, they continued to be ostracized by other Caltech scientists who grew increasingly irritated by their accidents and noise pollution, and were forced to relocate their experiments back to the Arroyo Seco, at a site with unventilated, corrugated iron sheds that served as both research facilities and administrative offices. It was here that JPL would be founded. Parsons and Forman's rocket experiments were the cover story of the August 1940 edition of ''Popular Mechanics

''Popular Mechanics'' (sometimes PM or PopMech) is a magazine of popular science and technology, featuring automotive, home, outdoor, electronics, science, do-it-yourself, and technology topics. Military topics, aviation and transportation o ...

'', in which the pair discussed the prospect of rockets being able to ascend above Earth's atmosphere and orbit around it for research purposes, as well as reaching the Moon.

For the JATO project, they were joined by Caltech mathematician

For the JATO project, they were joined by Caltech mathematician Martin Summerfield

Martin Summerfield (20 October 1916 – 18 July 1996) was an American physicist and rocket scientist, a co-founder of Aerojet, head of Princeton University propulsion and combustion laboratory.

and 18 workers supplied by the Works Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; renamed in 1939 as the Work Projects Administration) was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers (mostly men who were not formally educated) to carry out public works projects, i ...

. Former colleagues like Qian were prevented from returning to the project by the Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice ...

(FBI), who ensured the secrecy of the operation and restricted the involvement of foreign nationals and political extremists. The FBI was satisfied that Parsons was not a Marxist but were concerned when Thelemite friend Paul Seckler used Parsons' gun in a drunken car hijacking, for which Seckler was imprisoned in San Quentin State Prison

San Quentin State Prison (SQ) is a California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation state prison for men, located north of San Francisco in the unincorporated place of San Quentin in Marin County.

Opened in July 1852, San Quentin is t ...

for two years. Englishman George Emerson replaced Arnold as the Group's official photographer.

The Group's aim was to find a replacement for black-powder rocket motors—units consisting of charcoal, sulfur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formul ...

and potassium nitrate

Potassium nitrate is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . This alkali metal nitrate salt is also known as Indian saltpetre (large deposits of which were historically mined in India). It is an ionic salt of potassium ions K+ and ...

with a binding agent

A binder or binding agent is any material or substance that holds or draws other materials together to form a cohesive whole mechanically, chemically, by adhesion or cohesion.

In a more narrow sense, binders are liquid or dough-like substances th ...

. The mixture was unstable and there were frequent explosions damaging military aircraft. The solid JATO fuel invented by Parsons consisted of amide

In organic chemistry, an amide, also known as an organic amide or a carboxamide, is a compound with the general formula , where R, R', and R″ represent organic groups or hydrogen atoms. The amide group is called a peptide bond when it i ...

, corn starch

Corn starch, maize starch, or cornflour (British English) is the starch derived from corn (maize) grain. The starch is obtained from the endosperm of the kernel. Corn starch is a common food ingredient, often used to thicken sauces or sou ...

, and ammonium nitrate

Ammonium nitrate is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is a white crystalline salt consisting of ions of ammonium and nitrate. It is highly soluble in water and hygroscopic as a solid, although it does not form hydrates. It is ...

bound together in the JATO unit with glue and blotting paper. It was codenamed GALCIT-27, implying the previous invention of 26 new fuels. The first JATO tests using an ERCO Ercoupe

The ERCO Ercoupe is an American low-wing monoplane aircraft that was first flown in 1937. It was originally manufactured by the Engineering and Research Corporation (ERCO) shortly before World War II; several other manufacturers continued it ...

plane took place in late July 1941; though they aided propulsion, the units frequently exploded and damaged the aircraft. Parsons theorized that this was because the ammonium nitrate became dangerously combustible following overnight storage, during which temperature and consistency changes had resulted in a chemical imbalance. Parsons and Malina accordingly devised a method in which they would fill the JATOs with the fuel in the early mornings shortly before the tests, enduring sleep deprivation to do so. On August 21, 1941, Navy Captain Homer J. Boushey, Jr.—watched by Clark Millikan and William F. Durand

William Frederick Durand (March 5, 1859 – August 9, 1958) was a United States naval officer and pioneer mechanical engineer. He contributed significantly to the development of aircraft propellers. He was the first civilian chair of the National ...

—piloted the JATO-equipped Ercoupe at March Air Force Base

March Air Reserve Base (March ARB), previously known as March Air Force Base (March AFB) is located in Riverside County, California between the cities of Riverside, Moreno Valley, and Perris. It is the home to the Air Force Reserve Command's ...

in Moreno Valley

Moreno Valley is a city in Riverside County, California, United States, and is part of the Riverside–San Bernardino–Ontario metropolitan area. It is the second-largest city in Riverside County by population and one of the Inland Empire's p ...

, California. It proved a success and reduced takeoff distance by 30%, but one of the JATOs partially exploded. Over the following weeks 62 further tests took place, and the NAS increased their grant to $125,000. During a series of static experiments, an exploding JATO did significant damage to the rear fuselage of an Ercoupe; one observer optimistically noted that "at least it wasn't a big hole", but necessary repairs delayed their efforts.

The military ordered a flight test using liquid rather than solid fuel in early 1942. Upon the United States' entry into the Second World War in December 1941, the Group realized they could be drafted directly into military service if they failed to provide viable JATO technology for the military. Informed by their left-wing politics, aiding the war effort against Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and the Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

was as much of a moral vocation to Parsons, Forman and Malina as it was a practical one. Parsons, Summerfield and the GALCIT workers focused on the task and found success with a combination of gasoline

Gasoline (; ) or petrol (; ) (see ) is a transparent, petroleum-derived flammable liquid that is used primarily as a fuel in most spark-ignited internal combustion engines (also known as petrol engines). It consists mostly of organic c ...

with red fuming nitric acid

Red fuming nitric acid (RFNA) is a storable oxidizer used as a rocket propellant. It consists of 84% nitric acid (), 13% dinitrogen tetroxide and 1–2% water. The color of red fuming nitric acid is due to the dinitrogen tetroxide, which breaks ...

as its oxidizer

An oxidizing agent (also known as an oxidant, oxidizer, electron recipient, or electron acceptor) is a substance in a redox chemical reaction that gains or " accepts"/"receives" an electron from a (called the , , or ). In other words, an oxi ...

; the latter, suggested by Parsons, was an effective substitute for liquid oxygen

Liquid oxygen—abbreviated LOx, LOX or Lox in the aerospace, submarine and gas industries—is the liquid form of molecular oxygen. It was used as the oxidizer in the first liquid-fueled rocket invented in 1926 by Robert H. Goddard, an app ...

. The testing of this fuel resulted in another calamity, when the testing rocket motor exploded; the fire, containing iron shed fragments and shrapnel, inexplicably left the experimenters unscathed. Malina solved the problem by replacing the gasoline with aniline

Aniline is an organic compound with the formula C6 H5 NH2. Consisting of a phenyl group attached to an amino group, aniline is the simplest aromatic amine. It is an industrially significant commodity chemical, as well as a versatile starti ...

, resulting in a successful test launch of a JATO-equipped A-20A plane at the Muroc Auxiliary Air Field in the Mojave Desert

The Mojave Desert ( ; mov, Hayikwiir Mat'aar; es, Desierto de Mojave) is a desert in the rain shadow of the Sierra Nevada mountains in the Southwestern United States. It is named for the indigenous Mojave people. It is located primarily ...

. It provided five times more thrust than GALCIT-27, and again reduced takeoff distance by 30%; Malina wrote to his parents that "We now have something that really works and we should be able to help give the Fascists hell!"

The Group then agreed to produce and sell 60 JATO engines to the

The Group then agreed to produce and sell 60 JATO engines to the United States Army Air Corps

The United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) was the aerial warfare service component of the United States Army between 1926 and 1941. After World War I, as early aviation became an increasingly important part of modern warfare, a philosophical r ...

. To do so they formed the Aerojet Engineering Corporation in March 1942, in which Parsons, Forman, Malina, von Kármán, and Summerfield each invested $250, opening their offices on Colorado Boulevard

Colorado Boulevard (or Colorado Street in Glendale and Arcadia) is a major east–west street in Southern California. It runs from Griffith Park in Los Angeles east through Glendale, the Eagle Rock section of Los Angeles, Pasadena, and Arcad ...

and bringing in Amo Smith as their engineer. Andrew G. Haley was recruited by von Kármán as their lawyer and treasurer. Although Aerojet was a for-profit operation that provided technology for military means, the founders' mentality was rooted in the ideal of using rockets for peaceful space exploration. As Haley recounted von Kármán requesting: "we will make the rockets—you must make the corporation and obtain the money. Later on you will have to see that we all behave well in outer space."

Despite these successes, Parsons, the project engineer

Project engineering includes all parts of the design of manufacturing or processing facilities, either new or modifications to and expansions of existing facilities. A "project" consists of a coordinated series of activities or tasks performed by ...

of Aerojet's Solid Fuel Department, remained motivated to address the malfunctions observed during the Ercoupe tests. In June 1942, assisted by Mills and Miller, he focused his attention on developing an effective method of restricted burning when using solid rocket fuel, as the military demanded JATOs that could provide over 100 pounds of thrust without any risk of exploding. Although solid fuels such as GALCIT-27 were more storable than their liquid counterparts, they were disfavored for military JATO use as they provided less immediate thrust and did not have the versatility of being turned on and off mid-flight. Parsons tried to resolve GALCIT-27's stability issue with GALCIT-46, which replaced the former's ammonium nitrate with guanidine nitrate

Guanidine nitrate is the chemical compound with the formula (NH2)3O3. It is a colorless, water-soluble salt. It is produced on a large scale and finds use as precursor for nitroguanidine, fuel in pyrotechnics and gas generators. Its correct ...

. To avoid the problems seen with ammonium nitrate, he had GALCIT-46 cooled and then heated prior to testing. When it failed the test, he realized that the fuel's binding black powders rather than the oxidizers had resulted in their instability, and in June that year had the idea of using liquid asphalt

Asphalt, also known as bitumen (, ), is a sticky, black, highly viscous liquid or semi-solid form of petroleum. It may be found in natural deposits or may be a refined product, and is classed as a pitch. Before the 20th century, the term ...

as an appropriate binding agent with potassium perchlorate