Jack Benny on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jack Benny (born Benjamin Kubelsky, February 14, 1894 – December 26, 1974) was an American entertainer who evolved from a modest success playing violin on the vaudeville circuit to one of the leading entertainers of the twentieth century with a highly popular comedic career in radio, television, and film. He was known for his comic timing and the ability to cause laughter with a long pause or a single expression, such as his signature exasperated summation "''Well!''"

His radio and television programs, popular from 1932 until his death in 1974, were a major influence on the

Benny was born Benjamin Kubelsky in

Benny was born Benjamin Kubelsky in  In 1922, Benny accompanied Zeppo Marx to a Passover Seder in

In 1922, Benny accompanied Zeppo Marx to a Passover Seder in

Benny had been a minor vaudeville performer before becoming a national figure with '' The Jack Benny Program'', a weekly radio show that ran from 1932 to 1948 on NBC and from 1949 to 1955 on CBS. It was among the most highly rated programs during its run.

Benny's long radio career began on April 6, 1932, when the NBC Commercial Program Department auditioned him for the N. W. Ayer & Son agency and their client

Benny had been a minor vaudeville performer before becoming a national figure with '' The Jack Benny Program'', a weekly radio show that ran from 1932 to 1948 on NBC and from 1949 to 1955 on CBS. It was among the most highly rated programs during its run.

Benny's long radio career began on April 6, 1932, when the NBC Commercial Program Department auditioned him for the N. W. Ayer & Son agency and their client

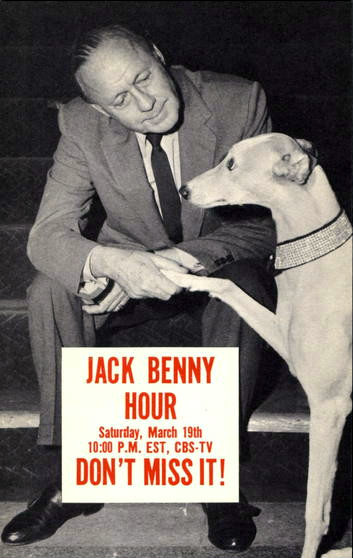

After making his television debut in 1949 on local Los Angeles station KTTV, then a CBS affiliate, the network television version of '' The Jack Benny Program'' ran from October 28, 1950, to 1965, all but the last season on CBS. Initially scheduled as a series of five "specials" during the 1950–1951 season, the show appeared every six weeks for the 1951–1952 season, every four weeks for the 1952–1953 season and every three weeks in 1953–1954. For the 1953–1954 season, half the episodes were live and half were filmed during the summer, to allow Benny to continue doing his radio show. From the fall of 1954 to 1960, it appeared every other week, and from 1960 to 1965 it was seen weekly.

On March 28, 1954, Benny co-hosted '' General Foods 25th Anniversary Show: A Salute to Rodgers and Hammerstein'' with Groucho Marx and

After making his television debut in 1949 on local Los Angeles station KTTV, then a CBS affiliate, the network television version of '' The Jack Benny Program'' ran from October 28, 1950, to 1965, all but the last season on CBS. Initially scheduled as a series of five "specials" during the 1950–1951 season, the show appeared every six weeks for the 1951–1952 season, every four weeks for the 1952–1953 season and every three weeks in 1953–1954. For the 1953–1954 season, half the episodes were live and half were filmed during the summer, to allow Benny to continue doing his radio show. From the fall of 1954 to 1960, it appeared every other week, and from 1960 to 1965 it was seen weekly.

On March 28, 1954, Benny co-hosted '' General Foods 25th Anniversary Show: A Salute to Rodgers and Hammerstein'' with Groucho Marx and  Benny was able to attract guests who rarely, if ever, appeared on television. In 1953, both

Benny was able to attract guests who rarely, if ever, appeared on television. In 1953, both  In his unpublished autobiography, ''I Always Had Shoes'' (portions of which were later incorporated by Jack's daughter, Joan Benny, into her memoir of her parents, ''Sunday Nights at Seven''), Benny said that he, not NBC, made the decision to end his TV series in 1965. He said that while the ratings were still very good (he cited a figure of some 18 million viewers per week, although he qualified that figure by saying he never believed the ratings services were doing anything more than guessing, no matter what they promised), advertisers were complaining that commercial time on his show was costing nearly twice as much as what they paid for most other shows, and he had grown tired of what was called the "rate race". Thus, after some three decades on radio and television in a weekly program, Jack Benny went out on top. In fairness, Benny himself shared Fred Allen's ambivalence about television, though not quite to Allen's extent. "By my second year in television, I saw that the camera was a man-eating monster ... It gave a performer close-up exposure that, week after week, threatened his existence as an interesting entertainer."

In a joint appearance with Phil Silvers on Dick Cavett's show, Benny recalled that he had advised Silvers not to appear on television. However, Silvers ignored Benny's advice and proceeded to win several Emmy awards as Sergeant Bilko on the popular series '' The Phil Silvers Show''.

In his unpublished autobiography, ''I Always Had Shoes'' (portions of which were later incorporated by Jack's daughter, Joan Benny, into her memoir of her parents, ''Sunday Nights at Seven''), Benny said that he, not NBC, made the decision to end his TV series in 1965. He said that while the ratings were still very good (he cited a figure of some 18 million viewers per week, although he qualified that figure by saying he never believed the ratings services were doing anything more than guessing, no matter what they promised), advertisers were complaining that commercial time on his show was costing nearly twice as much as what they paid for most other shows, and he had grown tired of what was called the "rate race". Thus, after some three decades on radio and television in a weekly program, Jack Benny went out on top. In fairness, Benny himself shared Fred Allen's ambivalence about television, though not quite to Allen's extent. "By my second year in television, I saw that the camera was a man-eating monster ... It gave a performer close-up exposure that, week after week, threatened his existence as an interesting entertainer."

In a joint appearance with Phil Silvers on Dick Cavett's show, Benny recalled that he had advised Silvers not to appear on television. However, Silvers ignored Benny's advice and proceeded to win several Emmy awards as Sergeant Bilko on the popular series '' The Phil Silvers Show''.

Benny also acted in films, including the

Benny also acted in films, including the

After his broadcasting career ended, Benny performed live as a standup comedian.

In the 1960s Benny was the headlining act at Harrah's Lake Tahoe with performer

After his broadcasting career ended, Benny performed live as a standup comedian.

In the 1960s Benny was the headlining act at Harrah's Lake Tahoe with performer

In October 1974, Benny cancelled a performance in

In October 1974, Benny cancelled a performance in

''Jack Benny v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue''

25 T.C. 197 (1955). * Balzer, George. ''They'll Break Your Heart'' (unpublished autobiography, undated), available a

jackbenny.org

* Hilmes, M. (1997). Radio voices American broadcasting, 1922–1952. Minnesota Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. * Josefsberg, Milt. (1977) ''The Jack Benny Show.'' New Rochelle: Arlington House. * Leannah, Michael, editor. (2007) ''Well! Reflections on the Life and Career of Jack Benny.'' BearManor Media. Contributing authors: Frank Bresee, Clair Schulz, Kay Linaker, Janine Marr, Pam Munter, Mark Higgins, B. J. Borsody, Charles A. Beckett, Jordan R. Young, Philip G. Harwood, Noell Wolfgram Evans, Jack Benny, Michael Leannah, Steve Newvine, Ron Sayles, Kathryn Fuller-Seeley, Marc Reed, Derek Tague, Michael J. Hayde, Steve Thompson, Michael Mildredson * Wise, James. ''Stars in Blue: Movie Actors in America's Sea Services''. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1997. * Zolotow, Maurice. "Jack Benny: the fine art of self-disparagement" in Zolotow, ''No People Like Show People'', Random House (New York: 1951); rpt Bantam Books (New York: 1952).

Jack Benny

at the National Radio Hall of Fame

International Jack Benny Fan Club

Jack Benny

on grubstreet.ca

Copies of Jack Benny's Radio and TV scripts, with handwritten edits

(archived)

Jack Benny papers

at the University of Wyoming American Heritage Center

FBI file on Jack Benny

Audio

All available Jack Benny radio programs in mp3

Jack Benny Show – OTR Podcast

Video * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Benny, Jack 1894 births 1974 deaths 20th-century American comedians 20th-century American male actors 20th-century American male musicians 20th-century American violinists Actors from Waukegan, Illinois American male comedy actors American male film actors American male radio actors American male television actors American male violinists American people of Lithuanian-Jewish descent American people of Polish-Jewish descent American radio personalities American stand-up comedians Television personalities from Los Angeles Burials at Hillside Memorial Park Cemetery Comedians from California Comedians from Illinois Deaths from cancer in California Deaths from pancreatic cancer Golden Globe Award winners Jewish American comedians Jewish American male actors Male actors from Chicago Military personnel from Illinois Outstanding Performance by a Lead Actor in a Comedy Series Primetime Emmy Award winners Peabody Award winners People from Bel Air, Los Angeles United States Navy personnel of World War I Vaudeville performers 20th-century American Jews United Service Organizations entertainers

sitcom

A sitcom, a portmanteau of situation comedy, or situational comedy, is a genre of comedy centered on a fixed set of characters who mostly carry over from episode to episode. Sitcoms can be contrasted with sketch comedy, where a troupe may use ...

genre. Benny portrayed himself as a miser who obliviously played his violin badly and claimed perpetually to be 39 years of age.

Early life

Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

, on February 14, 1894, and grew up in nearby Waukegan. He was the son of Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

immigrants Meyer Kubelsky (1864–1946) and Emma Sachs Kubelsky (1869–1917), sometimes called "Naomi". Meyer was a saloon owner and later a haberdasher who had emigrated to the United States of America from Poland. Emma had emigrated from Lithuania. At the age of 6, Benny began studying violin

The violin, sometimes known as a '' fiddle'', is a wooden chordophone ( string instrument) in the violin family. Most violins have a hollow wooden body. It is the smallest and thus highest-pitched instrument ( soprano) in the family in regu ...

, an instrument that became his trademark; his parents hoped for him to become a professional violinist. He loved the instrument but hated to practice. His music teacher was Otto Graham Sr., a neighbor and father of football player Otto Graham. At 14, Benny was playing in dance bands and his high school orchestra. He was a dreamer and poor at his studies, ultimately getting expelled from high school. He later did poorly in business school and in attempts to join his father's business. In 1911, he began playing the violin in local vaudeville theaters for $7.50 a week (about $ in 2020 dollars). He was joined on the circuit by Ned Miller

Henry Ned Miller (April 12, 1925 – March 18, 2016) was an American country music singer-songwriter. Active as a recording artist from 1956 to 1970, he is known primarily for his hit single " From a Jack to a King", a crossover hit in 1962 wh ...

, a young composer and singer.

That same year, Benny was playing in the same theater as the young Marx Brothers. Minnie, their mother, enjoyed Benny's violin playing and invited him to accompany her boys in their act. Benny's parents refused to let their son go on the road at 17, but it was the beginning of his long friendship with the Marx Brothers, especially Zeppo Marx.

The next year, Benny formed a vaudeville musical duo with pianist Cora Folsom Salisbury, who needed a partner for her act. This angered famous violinist Jan Kubelik, who feared that the young vaudevillian with a similar name would damage his reputation. Under legal pressure, Benjamin Kubelsky agreed to change his name to Ben K. Benny, sometimes spelled Bennie. When Salisbury left the act, Benny found a new pianist, Lyman Woods, and renamed the act "From Grand Opera to Ragtime". They worked together for five years and slowly integrated comedy elements into the show. They reached the Palace Theater, the "Mecca of Vaudeville", and did not do well. Benny left show business briefly in 1917 to join the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

during World War I, often entertaining fellow sailors with his violin playing. One evening, his violin performance was booed by the sailors, so with prompting from fellow sailor and actor Pat O'Brien, he ad-libbed his way out of the jam and left them laughing. He received more comedy spots in the revues and did well, earning a reputation as a comedian and musician. Despite stories to the contrary, no reliable evidence indicates Jack Benny was aboard during the 1915 Eastland

SS ''Eastland'' was a passenger ship based in Chicago and used for tours. On 24 July 1915, the ship rolled over onto its side while tied to a dock in the Chicago River. In total, 844 passengers and crew were killed in what was the largest loss ...

disaster or scheduled to be on the excursion; possibly the basis for this report was that Eastland was a training vessel during World War I and Benny received his training in the Great Lakes naval base where Eastland was stationed.

Shortly after the war, Benny developed a one-man act, "Ben K. Benny: Fiddle Funology". He then received legal pressure from Ben Bernie, a "patter-and-fiddle" performer, regarding his name, so he adopted the sailor's nickname of Jack. By 1921, the fiddle was more of a prop, and the low-key comedy took over.

Benny had some romantic encounters, including one with dancer Mary Kelly, whose devoutly Catholic family forced her to turn down his proposal because he was Jewish. Benny was introduced to Kelly by Gracie Allen.

Vancouver

Vancouver ( ) is a major city in western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the city, up from 631,486 in 2016. ...

at the residence where he met 17-year-old Sadie Marks (whose family was friends with, but not related to, the Marx family). Their first meeting did not go well when he tried to leave during Sadie's violin performance. They met again in 1926. Jack had not remembered their earlier meeting and instantly fell for her. They married the following year. She was working in the hosiery section of the Hollywood Boulevard branch of the May Company, where Benny courted her. Called on to fill in for the "dumb girl" part in a Benny routine, Sadie proved to be a natural comedienne. Adopting the stage name Mary Livingstone, Sadie collaborated with Benny throughout most of his career. They later adopted a daughter, Joan (1934–2021). Sadie's older sister Babe would often be the target of jokes about unattractive or masculine women, while her younger brother Hilliard would later produce Benny's radio and TV work.

In 1929, Benny's agent, Sam Lyons, convinced Irving Thalberg, American film producer at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc., also known as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures and abbreviated as MGM, is an American film, television production, distribution and media company owned by amazon (company), Amazon through MGM Holdings, founded o ...

, to watch Benny at the Orpheum Theatre in Los Angeles. Benny signed a five-year contract with MGM, where his first role was in '' The Hollywood Revue of 1929''. The next film, '' Chasing Rainbows'', did not do well, and after several months Benny was released from his contract and returned to Broadway in Earl Carroll's ''Vanities''. At first dubious about the viability of radio, Benny grew eager to break into the new medium. In 1932, after a four-week nightclub run, he was invited onto Ed Sullivan's radio program, uttering his first radio spiel "This is Jack Benny talking. There will be a slight pause while you say, 'Who cares?

Radio

Canada Dry

Canada Dry is a brand of soft drinks founded in 1904 and owned since 2008 by the American company Dr Pepper Snapple (now Keurig Dr Pepper). For over 100 years, Canada Dry has been known mainly for its ginger ale, though the company also manuf ...

, after which Bertha Brainard

Bertha Brainard (June 16, 1890 – June 11, 1946), known to her friends as Betty, was a pioneering NBC executive responsible for setting trends in network broadcasting.

Life and career

She was born and raised in South Orange, New Jersey, the daugh ...

, head of the division, said, "We think Mr. Benny is excellent for radio and, while the audition was unassisted as far as orchestra was concerned, we believe he would make a great bet for an air program." Recalling the experience in 1956, Benny said Ed Sullivan had invited him to guest on his program (1932), and "the agency for Canada Dry ginger ale heard me and offered me a job."

With Canada Dry ginger ale as a sponsor, Benny came to radio on ''The Canada Dry Program'', on May 2, 1932, broadcast on Mondays and Wednesdays on the NBC Blue Network, featuring George Olsen and his orchestra. After a few shows, Benny hired Harry Conn as writer. The show continued on Blue for six months until October 26, moving to CBS on October 30, now airing Thursdays and Sundays. With Ted Weems leading the band, Benny stayed on CBS until January 26, 1933, when Canada Dry opted not to renew Benny's contract after it attempted to replace Conn with Sid Silvers, who would have also gotten a co-starring role. Unlike later incarnations of the Benny show, ''The Canada Dry'' ''Program'' was primarily a musical program.

Benny then appeared on ''The Chevrolet Program'', airing on the NBC Red Network between March 17, 1933, until April 1, 1934, initially airing on Fridays (replacing Al Jolson), moving to Sunday nights in the fall. The show, which featured Benny and Livingstone alongside Frank Black's orchestra and vocalists James Melton and (later) Frank Parker, ended after General Motors' president insisted on a musical program. He continued with sponsor General Tire on Fridays through the end of September.

The show switched networks to CBS on January 2, 1949, as part of CBS president William S. Paley's notorious "raid" on NBC talent in 1948–1949. It stayed there for the remainder of its radio run, ending on May 22, 1955. CBS aired repeat episodes from 1956 to 1958 as ''The Best of Benny''.

Television

After making his television debut in 1949 on local Los Angeles station KTTV, then a CBS affiliate, the network television version of '' The Jack Benny Program'' ran from October 28, 1950, to 1965, all but the last season on CBS. Initially scheduled as a series of five "specials" during the 1950–1951 season, the show appeared every six weeks for the 1951–1952 season, every four weeks for the 1952–1953 season and every three weeks in 1953–1954. For the 1953–1954 season, half the episodes were live and half were filmed during the summer, to allow Benny to continue doing his radio show. From the fall of 1954 to 1960, it appeared every other week, and from 1960 to 1965 it was seen weekly.

On March 28, 1954, Benny co-hosted '' General Foods 25th Anniversary Show: A Salute to Rodgers and Hammerstein'' with Groucho Marx and

After making his television debut in 1949 on local Los Angeles station KTTV, then a CBS affiliate, the network television version of '' The Jack Benny Program'' ran from October 28, 1950, to 1965, all but the last season on CBS. Initially scheduled as a series of five "specials" during the 1950–1951 season, the show appeared every six weeks for the 1951–1952 season, every four weeks for the 1952–1953 season and every three weeks in 1953–1954. For the 1953–1954 season, half the episodes were live and half were filmed during the summer, to allow Benny to continue doing his radio show. From the fall of 1954 to 1960, it appeared every other week, and from 1960 to 1965 it was seen weekly.

On March 28, 1954, Benny co-hosted '' General Foods 25th Anniversary Show: A Salute to Rodgers and Hammerstein'' with Groucho Marx and Mary Martin

Mary Virginia Martin (December 1, 1913 – November 3, 1990) was an American actress and singer. A muse of Rodgers and Hammerstein, she originated many leading roles on stage over her career, including Nellie Forbush in ''South Pacific'' (194 ...

. In September 1954, CBS premiered Chrysler's ''Shower of Stars

''Shower of Stars'' (also known as ''Chrysler Shower of Stars'') is an American variety television series broadcast live in the United States from 1954 to 1958 by CBS. The series was broadcast in color which was a departure from the usual CBS p ...

'' co-hosted by Jack Benny and William Lundigan. It enjoyed a successful run from 1954 until 1958. Both television shows often overlapped the radio show. In fact, the radio show alluded frequently to its television counterparts. Often as not, Benny would sign off the radio show in such circumstances with the line "Well, good night, folks. I'll see you on television."

When Benny moved to television, audiences learned that his verbal talent was matched by his controlled repertory of dead-pan facial expressions and gesture. The program was similar to the radio show (several of the radio scripts were recycled for television, as was somewhat common with other radio shows that moved to television), but with the addition of visual gags. Lucky Strike was the sponsor. Benny did his opening and closing monologues before a live audience, which he regarded as essential to timing of the material. As in other TV comedy shows, a laugh track was added to "sweeten" the soundtrack, as when the studio audience missed some close-up comedy because of cameras or microphones obstructing their view. Television viewers became accustomed to live without Mary Livingstone, who was afflicted by a striking case of stage fright that didn't lessen even after performing with Benny for 20 years. Hence, Livingstone appeared rarely if at all on the television show. In fact, for the last few years of the radio show, she pre-recorded her lines and Jack and Mary's daughter, Joan, stood in for the live taping, with Mary's lines later edited into the tape replacing Joan's before broadcast. Mary Livingstone finally retired from show business permanently in 1958, as her friend Gracie Allen had done.

Benny's television program relied more on guest stars and less on his regulars than his radio program. In fact, the only radio cast members who appeared regularly on the television program as well were Don Wilson and Eddie "Rochester" Anderson. Singer Dennis Day appeared sporadically, and Harris had left the radio program in 1952, although he did make a guest appearance on the television show ( Bob Crosby, Phil's "replacement", frequently appeared on television through 1956). A frequent guest was the Canadian-born singer-violinist Gisele Mackenzie.

As a gag, Benny made a 1957 appearance on the then-wildly popular ''$64,000 Question

''The $64,000 Question'' was an American game show broadcast in primetime on CBS-TV from 1955 to 1958, which became embroiled in the 1950s quiz show scandals. Contestants answered general knowledge questions, earning money which doubled as the ...

''. His category of choice was "Violins", but after answering the first question correctly Benny opted out of continuing, leaving the show with just $64; host Hal March gave Benny the prize money out of his own pocket. March made an appearance on Benny's show the same year.

Marilyn Monroe

Marilyn Monroe (; born Norma Jeane Mortenson; 1 June 1926 4 August 1962) was an American actress. Famous for playing comedic " blonde bombshell" characters, she became one of the most popular sex symbols of the 1950s and early 1960s, as wel ...

and Humphrey Bogart made their television debuts on Benny's program.

Another guest star on the Jack Benny show was Rod Serling, who starred in a spoof of '' The Twilight Zone'' in which Benny goes to his own house and finds that no one knows who he is; Jack runs away screaming in panic; Serling breaks the fourth wall and remarks not to worry about Benny on the grounds that anyone who has been 39 years old as long as he has is a citizen of the "Twilight Zone".

Canadian

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

singer Gisele MacKenzie, who toured with Benny in the early 1950s, guest starred seven times on ''The Jack Benny Program''. Benny was so impressed with MacKenzie's talents that he served as co- executive producer and guest starred on her 1957–1958 NBC variety show, '' The Gisele MacKenzie Show''.

In 1964, Walt Disney

Walter Elias Disney (; December 5, 1901December 15, 1966) was an American animator, film producer and entrepreneur. A pioneer of the American animation industry, he introduced several developments in the production of cartoons. As a film p ...

was a guest, primarily to promote his production of ''Mary Poppins It may refer to:

* ''Mary Poppins'' (book series), the original 1934–1988 children's fantasy novels that introduced the character.

* Mary Poppins (character), the nanny with magical powers.

* ''Mary Poppins'' (film), a 1964 Disney film star ...

''. Benny persuaded Disney to give him over 110 free admission tickets to Disneyland

Disneyland is a theme park in Anaheim, California. Opened in 1955, it was the first theme park opened by The Walt Disney Company and the only one designed and constructed under the direct supervision of Walt Disney. Disney initially envisio ...

for his friends and one for his wife, but later in the show Disney apparently sent his pet tiger after Benny as revenge, at which point Benny opened his umbrella and soared above the stage like Mary Poppins. Jack ends TV episode as Mary Poppins

CBS dropped the show in 1964, citing Benny's lack of appeal to the younger demographic the network began courting, and he went to NBC, his original network, in the fall, only to be out-rated by CBS's ''Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C.

''Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C.''The show (and CBS) renders the title as ''Gomer Pyle – USMC''. is an American situation comedy that originally aired on CBS from September 25, 1964, to May 2, 1969. The series was a spin-off of ''The Andy Griffith Sho ...

'' The network dropped Benny at the end of the season. He continued to make occasional specials into the 1970s, the last one airing in January 1974. Benny also appeared on '' The Lucy Show'' twice: Once as a plumber who resembles Jack Benny and in 1967 "Lucy Gets Jack Benny's account" where Lucy takes Jack on a tour of his new money vault. In the late 1960s, Benny did a series of commercials for Texaco Sky Chief gasoline, using his "stingy" television persona, always telling the attendant, played by Dennis Day, after being implored, "Mr. Benny, won't you please fill up?", "I'll take a gallon."

Films

Benny also acted in films, including the

Benny also acted in films, including the Academy Award

The Academy Awards, better known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international film industry. The awards are regarded by many as the most prestigious, significant awards in the entertainment ind ...

-winning '' The Hollywood Revue of 1929'', '' Broadway Melody of 1936'' (as a benign nemesis for Eleanor Powell

Eleanor Torrey Powell (November 21, 1912 – February 11, 1982) was an American dancer and actress. Best remembered for her tap dance numbers in musical films in the 1930s and 1940s, she was one of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's top dancing stars du ...

and Robert Taylor), ''George Washington Slept Here

''George Washington Slept Here'' is a 1942 comedy film starring Jack Benny, Ann Sheridan, Charles Coburn, Percy Kilbride, and Hattie McDaniel. It was based on the 1940 play of the same name by Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman, adapted by Everet ...

'' (1942), and notably, '' Charley's Aunt'' (1941) and '' To Be or Not to Be'' (1942). He and Livingstone also appeared in Ed Sullivan's '' Mr. Broadway'' (1933) as themselves. Benny often parodied contemporary films and genres on the radio program, and the 1940 film '' Buck Benny Rides Again'' features all the main radio characters in a funny Western parody adapted from program skits. The failure of one cinematic Benny vehicle, '' The Horn Blows at Midnight'', became a running gag on his radio and television programs, although contemporary viewers may not find the film as disappointing as the jokes suggest.

Benny may have had an uncredited cameo role in '' Casablanca'', claimed by a contemporary newspaper article and advertisement and reportedly in the ''Casablanca'' press book. When asked in his column "Movie Answer Man", film critic Roger Ebert first replied, "It looks something like him. That's all I can say." RogerEbert.com He wrote in a later column, "I think you're right."

Benny also was caricatured in several Warner Brothers cartoons including '' Daffy Duck and the Dinosaur'' (1939, as Casper the Caveman), '' I Love to Singa'', ''Slap Happy Pappy'', and ''Goofy Groceries'' (1936, 1940, and 1941 respectively, as Jack Bunny), ''Malibu Beach Party'' (1940, as himself), and '' The Mouse that Jack Built'' (1959). The last of these is probably the most memorable: Robert McKimson engaged Benny and his actual cast (Mary Livingstone, Eddie “Rochester” Anderson, and Don Wilson) to do the voices for the mouse versions of their characters, with Mel Blancthe usual Warner Brothers cartoon voicemeisterreprising his old vocal turn as the always-aging Maxwell, always a ''phat''-phat-''bang!'' away from collapse. In the cartoon, Benny and Livingstone agree to spend their anniversary at the Kit-Kat Club, which they discover the hard way is inside the mouth of a live cat. Before the cat can devour the mice, Benny himself awakens from his dream, then shakes his head, smiles wryly, and mutters, "Imagine, me and Mary as little mice." Then, he glances toward the cat lying on a throw rug in a corner and sees his and Livingstone's cartoon alter egos scampering out of the cat's mouth. The cartoon ends with a classic Benny look of befuddlement. It was rumored that Benny requested that, in lieu of monetary compensation, he receive a copy of the finished film.

Benny made a cameo appearance in '' It's A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World''.

Final years

Harry James

Harry Haag James (March 15, 1916 – July 5, 1983) was an American musician who is best known as a trumpet-playing band leader who led a big band from 1939 to 1946. He broke up his band for a short period in 1947 but shortly after he reorganized ...

, and Vocalist Ray Vasquez.

Benny made one of his final television appearances on January 23, 1974, as a guest on '' The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson'', the day before his final television special aired. Benny was preparing to star in the film version of Neil Simon's '' The Sunshine Boys'' when his health failed later the same year. He prevailed upon his longtime best friend, George Burns, to take his place on a nightclub tour while preparing for the film. Burns ultimately had to replace Benny in the film as well, going on to win an Academy Award

The Academy Awards, better known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international film industry. The awards are regarded by many as the most prestigious, significant awards in the entertainment ind ...

for his performance.

Despite his failing health, Benny would go on to make one last appearance on The Tonight Show on August 21, 1974, with Rich Little as guest host. Benny also made several appearances on '' The Dean Martin Celebrity Roast'' in his final 18 months, roasting Ronald Reagan, Johnny Carson, Bob Hope

Leslie Townes "Bob" Hope (May 29, 1903 – July 27, 2003) was a British-American comedian, vaudevillian, actor, singer and dancer. With a career that spanned nearly 80 years, Hope appeared in more than 70 short and feature films, with ...

and Lucille Ball

Lucille Désirée Ball (August 6, 1911 – April 26, 1989) was an American actress, comedienne and producer. She was nominated for 13 Primetime Emmy Awards, winning five times, and was the recipient of several other accolades, such as the Gold ...

, in addition to himself being roasted in February 1974. The Lucille Ball roast, his last public performance, aired on February 7, 1975, several weeks after his death.

Death

Dallas

Dallas () is the third largest city in Texas and the largest city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the fourth-largest metropolitan area in the United States at 7.5 million people. It is the largest city in and seat of Dallas County ...

after suffering a dizzy spell, coupled with numbness in his arms. Despite a battery of tests, Benny's ailment could not be determined. When he complained of stomach pains in early December, a first test showed nothing, but a subsequent examination showed that he had inoperable pancreatic cancer. Benny went into a coma at home on December 22, 1974. While in a coma, he was visited by close friends, including George Burns, Bob Hope

Leslie Townes "Bob" Hope (May 29, 1903 – July 27, 2003) was a British-American comedian, vaudevillian, actor, singer and dancer. With a career that spanned nearly 80 years, Hope appeared in more than 70 short and feature films, with ...

, Frank Sinatra, Johnny Carson, John Rowles and then Governor Ronald Reagan. He died on December 26, 1974, at age 80. At the funeral, Burns, Benny's best friend for more than fifty years, attempted to deliver a eulogy but broke down shortly after he began and was unable to continue. Hope also delivered a eulogy in which he stated, "For a man who was the undisputed master of comedic timing, you would have to say this is the only time when Jack Benny's timing was all wrong. He left us much too soon." Benny was interred in a crypt at Hillside Memorial Park Cemetery in Culver City, California. His will arranged for a single long-stemmed red rose

A rose is either a woody perennial flowering plant of the genus ''Rosa'' (), in the family Rosaceae (), or the flower it bears. There are over three hundred species and tens of thousands of cultivars. They form a group of plants that can be ...

to be delivered to his widow, Mary Livingstone, every day for the rest of her life. Livingstone died eight and a half years later on June 30, 1983, at the age of 78.

In trying to explain his successful life, Benny summed it up by stating: "Everything good that happened to me happened by accident. I was not filled with ambition nor fired by a drive toward a clear-cut goal. I never knew exactly where I was going."

Upon his death, Benny's family donated his personal, professional and business papers, as well as a collection of his television shows, to UCLA. The university established the Jack Benny Award for Comedy in his honor in 1977 to recognize outstanding people in the field of comedy. Johnny Carson was the first award recipient. Benny also donated a Stradivarius violin (purchased in 1957) to the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra. Benny had quipped, "If it isn't a $30,000 Strad, I'm out $120."

Honors and tributes

In 1960, Benny was inducted into the Hollywood Walk of Fame with three stars. His stars for television and motion pictures are located at 6370 and 6650 Hollywood Boulevard, respectively, and at 1505 Vine Street for radio. He was inducted into theTelevision Hall of Fame

The Television Academy Hall of Fame honors individuals who have made extraordinary contributions to U.S. television. The hall of fame was founded by former Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (ATAS) president John H. Mitchell (1921–1988). ...

in 1988 and the National Radio Hall of Fame in 1989. He was also inducted into the Broadcasting and Cable Hall of Fame.

Benny was inducted as a laureate of The Lincoln Academy of Illinois and awarded the Order of Lincoln (the state's highest honor) by the governor of Illinois in 1972 in the area of the performing arts.

When the price of a standard first-class U.S. postal stamp was increased to 39 cents in 2006, fans petitioned for a Jack Benny stamp to honor his stage persona's perpetual age. The U.S. Postal Service had issued a stamp depicting Benny in 1991 as part of a booklet of stamps honoring comedians; however, the stamp was issued at the then-current rate of 29 cents.

Jack Benny Middle School in Waukegan is named after Benny. Its motto matches his famous statement as "Home of the '39ers." A statue of Benny with his violin stands in downtown Waukegan.

The British comedian Benny Hill, whose original name was Alfred Hawthorne Hill, changed his name as a tribute to Jack Benny.

He was mentioned by Doc Brown in '' Back to the Future'', in which Doc guesses who would be Secretary of the Treasury by 1985, not believing Ronald Reagan was President of the United States of America. In reality, Benny died before 1985.

Filmography

Selected radio appearances

References

Further reading

* The New York Times, April 16, 1953, p. 43, "Jack Benny plans more work on TV" * The New York Times, March 16, 1960, p. 75, "Canned laughter: Comedians are crying on the inside about CBS rule that public know of its use" * ''Jack Benny'', Mary Livingstone Benny, Hilliard Marks with Marcia Borie, Doubleday & Company, 1978, 322 p. * ''Sunday Nights at Seven: The Jack Benny Story'', Jack Benny and Joan Benny, Warner Books, 1990, 302 p. * ''CBS: Reflections in a Bloodshot Eye'', by Robert Metz, New American Library, 1978. * ''The Laugh Crafters: Comedy Writing in Radio and TV's Golden Age'', by Jordan R. Young; Past Times Publishing, 1999. * ''Well! Reflections on the Life and Career of Jack Benny'', edited by Michael Leannah, BearManor Media, 2007.''Jack Benny v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue''

25 T.C. 197 (1955). * Balzer, George. ''They'll Break Your Heart'' (unpublished autobiography, undated), available a

jackbenny.org

* Hilmes, M. (1997). Radio voices American broadcasting, 1922–1952. Minnesota Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. * Josefsberg, Milt. (1977) ''The Jack Benny Show.'' New Rochelle: Arlington House. * Leannah, Michael, editor. (2007) ''Well! Reflections on the Life and Career of Jack Benny.'' BearManor Media. Contributing authors: Frank Bresee, Clair Schulz, Kay Linaker, Janine Marr, Pam Munter, Mark Higgins, B. J. Borsody, Charles A. Beckett, Jordan R. Young, Philip G. Harwood, Noell Wolfgram Evans, Jack Benny, Michael Leannah, Steve Newvine, Ron Sayles, Kathryn Fuller-Seeley, Marc Reed, Derek Tague, Michael J. Hayde, Steve Thompson, Michael Mildredson * Wise, James. ''Stars in Blue: Movie Actors in America's Sea Services''. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1997. * Zolotow, Maurice. "Jack Benny: the fine art of self-disparagement" in Zolotow, ''No People Like Show People'', Random House (New York: 1951); rpt Bantam Books (New York: 1952).

External links

* * * *Jack Benny

at the National Radio Hall of Fame

International Jack Benny Fan Club

Jack Benny

on grubstreet.ca

Copies of Jack Benny's Radio and TV scripts, with handwritten edits

(archived)

Jack Benny papers

at the University of Wyoming American Heritage Center

FBI file on Jack Benny

Audio

All available Jack Benny radio programs in mp3

Jack Benny Show – OTR Podcast

Video * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Benny, Jack 1894 births 1974 deaths 20th-century American comedians 20th-century American male actors 20th-century American male musicians 20th-century American violinists Actors from Waukegan, Illinois American male comedy actors American male film actors American male radio actors American male television actors American male violinists American people of Lithuanian-Jewish descent American people of Polish-Jewish descent American radio personalities American stand-up comedians Television personalities from Los Angeles Burials at Hillside Memorial Park Cemetery Comedians from California Comedians from Illinois Deaths from cancer in California Deaths from pancreatic cancer Golden Globe Award winners Jewish American comedians Jewish American male actors Male actors from Chicago Military personnel from Illinois Outstanding Performance by a Lead Actor in a Comedy Series Primetime Emmy Award winners Peabody Award winners People from Bel Air, Los Angeles United States Navy personnel of World War I Vaudeville performers 20th-century American Jews United Service Organizations entertainers