Italian war crimes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Italian war crimes have mainly been associated with Fascist Italy in the

In 1923,

In 1923,

Google books link

/ref> Italian authorities claimed that these actions were in response to the Ethiopians' use of Dum-Dum bullets, which had been banned by declaration IV, 3 of the Hague Convention, and mutilation of captured soldiers. According to the Ethiopian government, 382,800 civilian deaths were directly attributable to the Italian invasion. 17,800 women and children killed by bombing, 30,000 people were killed in the massacre of February 1937, 35,000 people died in concentration camps, and 300,000 people died of privations due to the destruction of their villages and farms. The Ethiopian government also claimed that the Italians destroyed 2,000 churches and 525,000 houses, while confiscating or slaughtering 6 million cattle, 7 million sheep and goats, and 1.7 million horses, mules, and camels, leading to the latter deaths. During the 1936–1941 Italian occupation, atrocities also occurred; in the February 1937

(Archived by

''«Si ammazza troppo poco». I crimini di guerra italiani. 1940–43''

Mondadori, Baldissara, Luca & Pezzino, Paolo (2004). ''Crimini e memorie di guerra: violenze contro le popolazioni e politiche del ricordo'', L'Ancora del Mediterraneo.

In April 1941, Italy invaded Yugoslavia, occupying large portions of Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, Montenegro, Serbia and Macedonia, while directly annexing to Italy the Ljubljana Province, Gorski Kotar and Central

In April 1941, Italy invaded Yugoslavia, occupying large portions of Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, Montenegro, Serbia and Macedonia, while directly annexing to Italy the Ljubljana Province, Gorski Kotar and Central

In the

In the

On their own, or with their Nazi allies, the occupying Italian army undertook many armed actions, including brutal offensives intended to wipe out Partisan resistance. This included

On their own, or with their Nazi allies, the occupying Italian army undertook many armed actions, including brutal offensives intended to wipe out Partisan resistance. This included  In Ljubljana Province, in July 1941, the Italian army assembled 80,000 well-armed troops to attack 2,500-3,000 poorly armed Partisans, who had liberated large portions of the Province. Italian general

In Ljubljana Province, in July 1941, the Italian army assembled 80,000 well-armed troops to attack 2,500-3,000 poorly armed Partisans, who had liberated large portions of the Province. Italian general

A similar phenomenon took place in Greece in the immediate postwar years. The Italian occupation of Greece was often brutal, resulting in reprisals such as the Domenikon Massacre. The Greek government claimed that Italian occupation forces destroyed 110,000 buildings and via various causes inflicted economic damage of $6 billion (1938 exchange rates) while executing 11,000 civilians; in terms of the percentage of direct and indirect destruction this was almost identical to the figures attributed to German occupation forces. The Italians also presided over the

A similar phenomenon took place in Greece in the immediate postwar years. The Italian occupation of Greece was often brutal, resulting in reprisals such as the Domenikon Massacre. The Greek government claimed that Italian occupation forces destroyed 110,000 buildings and via various causes inflicted economic damage of $6 billion (1938 exchange rates) while executing 11,000 civilians; in terms of the percentage of direct and indirect destruction this was almost identical to the figures attributed to German occupation forces. The Italians also presided over the

2003,

General Roatta's war against the partisans in Yugoslavia: 1942

Journal of Modern Italian Studies, Volume 9, Number 3, pp. 314–329(16) for which after the war the Yugoslav government sought unsuccessfully to have him extradited for war crimes. He was quoted as saying "''Non dente per dente, ma testa per dente''" ("''Not a tooth for tooth but a head for a tooth''"), while Robotti was quoted as saying "''Non si ammazza abbastanza!''" ("''There are not enough killings''") in 1942. "On 1 March 1942, he ''(Roatta)'' circulated a pamphlet entitled '3C' among his commanders that spelled out military reform and draconian measures to intimidate the Slav populations into silence by means of summary executions, hostage-taking, reprisals, internments and the burning of houses and villages. By his reckoning, military necessity knew no choice, and law required only lip service. Roatta's merciless suppression of partisan insurgency was not mitigated by his having saved the lives of both Serbs and Jews from the persecution of Italy's allies Germany and Croatia. Under his watch, the 2nd Army's record of violence against the Yugoslav population easily matched the German. Tantamount to a declaration of war on civilians, Roatta's '3C' pamphlet involved him in war crimes." One of Roatta's soldiers wrote home on July 1, 1942: "We have destroyed everything from top to bottom without sparing the innocent. We kill entire families every night, beating them to death or shooting them." As noted by Minister of Foreign Affairs in Mussolini government,

Giuseppe Piemontese (1946): Twenty-nine months of Italian occupation of the Province of LjubljanaMichael Palumbo, ''L'olocausto rimosso'', Milano, Rizzoli, 1992

* Lidia Santarelli: "Muted violence: Italian war crimes in occupied Greece", ''Journal of Modern Italian Studies'', September 2004, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 280–299(20); Routledge, part of the Taylor & Francis Group * Effie Pedaliu (2004): Britain and the ‘Hand-Over’ of Italian War Criminals to Yugoslavia, 1945–48, ''Journal of Contemporary History'', Vol. 39, No. 4, 503–529 * Pietro Brignoli (1973):

messa per i miei fucilati

', Longanesi & C., Milano, * H. James Burgwyn (2004): "General Roatta's war against the partisans in Yugoslavia: 1942", ''Journal of Modern Italian Studies'', September vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 314–329(16) * Gianni Oliva (2006): 'Si ammazza troppo poco'. I crimini di guerra italiani 1940–43. ('There are too few killings'. Italian war crimes 1940–43), Mondadori, *

Italian Crimes In Yugoslavia (Yugoslav Information Office – London 1945)

Mass internment of civil population under inhuman conditions – Italian concentration camps

{{World War II War crimes committed by country

Pacification of Libya

The Second Italo-Senussi War, also referred to as the Pacification of Libya, was a conflict that occurred during the Italian colonization of Libya between Italian military forces (composed mainly of colonial troops from Libya, Eritrea, and ...

, the Second Italo-Ethiopian War

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a war of aggression which was fought between Fascist Italy (1922–1943), Italy and Ethiopian Empire, Ethiopia from October 1935 to February 1937. In Ethio ...

, the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

, and World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

.

Italo-Turkish War

In 1911, Italy went to war with theOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

and invaded Ottoman Tripolitania

The coastal region of what is today Libya was ruled by the Ottoman Empire from 1551 to 1912. First, from 1551 to 1864, as the Eyalet of Tripolitania ( ota, ایالت طرابلس غرب ''Eyālet-i Trâblus Gârb'') or '' Bey and Subjects of Tr ...

. One of the most notorious incidents during this conflict was the October Tripoli massacre, wherein many civilian inhabitants of the Mechiya oasis were killed over a period of three days as retribution for the execution and mutilation of Italian captives taken in an ambush at nearby Sciara Sciat. In 1912, 10,000 Turkish and Arab troops were imprisoned in concentration camps in Libya, all Turkish troops were executed.

Pacification of Libya

In 1923,

In 1923, Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

embarked upon a pacification of Libya campaign to consolidate control over the Italian territory of Libya and Italian forces began to occupy large areas of Libya in order to allow Italian colonists to rapidly settle in it. They were met with resistance by the Senussi

The Senusiyya, Senussi or Sanusi ( ar, السنوسية ''as-Sanūssiyya'') are a Muslim political-religious tariqa (Sufi order) and clan in colonial Libya and the Sudan region founded in Mecca in 1837 by the Grand Senussi ( ar, السنوسي ...

who were led by Omar Mukhtar

Omar al-Mukhṭār Muḥammad bin Farḥāṭ al-Manifī ( ar, عُمَر الْمُخْتَار مُحَمَّد بِن فَرْحَات الْمَنِفِي ; 20 August 1858 – 16 September 1931), called The Lion of the Desert, known among ...

. Civilians suspected of collaboration with the Senussi were executed. Refugees from the fighting were subject to bombing and strafing by Italian aircraft. In 1930, in northern Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika ( ar, برقة, Barqah, grc-koi, Κυρηναϊκή ��παρχίαKurēnaïkḗ parkhíā}, after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between ...

, 20,000 Bedouins

The Bedouin, Beduin, or Bedu (; , singular ) are nomadic Arab tribes who have historically inhabited the desert regions in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. The Bedouin originated in the Syrian Desert and Ar ...

were relocated and their land was given to Italian settlers. The Bedouins were forced to march across the desert into concentration camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

. Starvation and other poor conditions in the camps were rampant and the internees were used for forced labour

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

, ultimately leading to the death of nearly 4,000 internees by the time they were closed in September 1933. Over 80,000 Cyrenaicans died during the Pacification in all.

Second Italo-Ethiopian War

During theSecond Italo-Ethiopian War

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a war of aggression which was fought between Fascist Italy (1922–1943), Italy and Ethiopian Empire, Ethiopia from October 1935 to February 1937. In Ethio ...

, Italian violations of the laws of war

The law of war is the component of international law that regulates the conditions for initiating war ('' jus ad bellum'') and the conduct of warring parties (''jus in bello''). Laws of war define sovereignty and nationhood, states and territ ...

were reported and documented. Effie G. H. Pedaliu (2004) Britain and the 'Hand-over' of Italian War Criminals to Yugoslavia, 1945–48. ''Journal of Contemporary History''. Vol. 39, No. 4, Special Issue: Collective Memory, pp. 503–529 These included the use of chemical weapons

A chemical weapon (CW) is a specialized munition that uses chemicals formulated to inflict death or harm on humans. According to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), this can be any chemical compound intended as a ...

such as mustard gas

Mustard gas or sulfur mustard is a chemical compound belonging to a family of cytotoxic and blister agents known as mustard agents. The name ''mustard gas'' is technically incorrect: the substance, when dispersed, is often not actually a gas, ...

, the use of concentration camps in counter-insurgency, and attacks on Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

facilities.Rainer Baudendistel, ''Between bombs and good intentions: the Red Cross and the Italo-Ethiopian War, 1935-1936'', Berghahn Books, 2006, p.239; 131-2Google books link

/ref> Italian authorities claimed that these actions were in response to the Ethiopians' use of Dum-Dum bullets, which had been banned by declaration IV, 3 of the Hague Convention, and mutilation of captured soldiers. According to the Ethiopian government, 382,800 civilian deaths were directly attributable to the Italian invasion. 17,800 women and children killed by bombing, 30,000 people were killed in the massacre of February 1937, 35,000 people died in concentration camps, and 300,000 people died of privations due to the destruction of their villages and farms. The Ethiopian government also claimed that the Italians destroyed 2,000 churches and 525,000 houses, while confiscating or slaughtering 6 million cattle, 7 million sheep and goats, and 1.7 million horses, mules, and camels, leading to the latter deaths. During the 1936–1941 Italian occupation, atrocities also occurred; in the February 1937

Yekatit 12

Yekatit 12 () is a date in the Ge'ez calendar which refers to the massacre and imprisonment of Ethiopians by the Italian occupation forces following an attempted assassination of Marshal Rodolfo Graziani, Marquis of Negele, Viceroy of Italian ...

massacres as many as 30,000 Ethiopians may have been killed and many more imprisoned as a reprisal for the attempted assassination of Viceroy Rodolfo Graziani

Rodolfo Graziani, 1st Marquis of Neghelli (; 11 August 1882 – 11 January 1955), was a prominent Italian military officer in the Kingdom of Italy's '' Regio Esercito'' ("Royal Army"), primarily noted for his campaigns in Africa before and durin ...

. A 2017 study estimated that 19,200 were killed - a fifth of the population of Addis Ababa. The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church ( am, የኢትዮጵያ ኦርቶዶክስ ተዋሕዶ ቤተ ክርስቲያን, ''Yäityop'ya ortodoks täwahedo bétäkrestyan'') is the largest of the Oriental Orthodox Churches. One of the few Chris ...

was especially singled out. Thousands of Ethiopians also died in concentration camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

such as Danane

Danane ( so, Danaane, ar, دنانه) is a coastal town in the southern Lower Shebelle province of Somalia. It is located approximately to the southwest of the nation's capital Mogadishu.

History

In the past the Italians set a concentrati ...

and Nocra.

Spanish Civil War

75,000 Italian soldiers of the Corpo Truppe Volontarie fought on the side of the Nationalists during theSpanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

, as did 7,000 men of the Aviazione Legionaria

The Legionary Air Force ( it, Aviazione Legionaria, es, Aviación Legionaria) was an expeditionary corps from the Italian Royal Air Force that was set up in 1936. It was sent to provide logistical and tactical support to the Nationalist facti ...

. While they also bombed valid military targets such as the railway infrastructure of Xativa, the Italian air force partook in many bombings of civilian targets for the purposes of "weakening the morale of the Reds". One of the more notable bombings was the Bombing of Barcelona

The Bombing of Barcelona was a series of airstrikes led by Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany supporting the Franco-led Nationalist rebel army, which took place from 16 to 18 March 1938, during the Spanish Civil War. Up to 1,300 people were killed ...

, in which 1,300 civilians were killed, with thousands more being wounded or dehoused. Other cities subjected to terror bombing by the Italians included Durango

Durango (), officially named Estado Libre y Soberano de Durango ( en, Free and Sovereign State of Durango; Tepehuán: ''Korian''; Nahuatl: ''Tepēhuahcān''), is one of the 31 states which make up the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico, situated in ...

, Alicante

Alicante ( ca-valencia, Alacant) is a city and municipality in the Valencian Community, Spain. It is the capital of the province of Alicante and a historic Mediterranean port. The population of the city was 337,482 , the second-largest in ...

, Granollers

Granollers () is a city in central Catalonia, about 30 kilometres north-east of Barcelona. It is the capital and most densely populated city in the comarca of Vallès Oriental.

Granollers is now a bustling business centre, having grown from a ...

, and Guernica

Guernica (, ), official name (reflecting the Basque language) Gernika (), is a town in the province of Biscay, in the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country, Spain. The town of Guernica is one part (along with neighbouring Lumo) of the m ...

.

Documents found in British archives by the historian Effie Pedaliu and documents found in Italian archives by the Italian historian Davide Conti, pointed out that the memory of the existence of the Italian concentration camps

Italian concentration camps include camps from the Italian colonial wars in Africa as well as camps for the civilian population from areas occupied by Italy during World War II. Memory of both camps were subjected to "historical amnesia". The rep ...

and Italian war crimes committed during the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

had been repressed due to the Cold War.

World War II

TheBritish

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

and American governments, fearful of the post-war Italian Communist Party

The Italian Communist Party ( it, Partito Comunista Italiano, PCI) was a communist political party in Italy.

The PCI was founded as ''Communist Party of Italy'' on 21 January 1921 in Livorno by seceding from the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) ...

, effectively undermined the quest for justice by tolerating the efforts made by Italy's top authorities to prevent any of the alleged Italian war criminals from being extradited and taken to court.Italy's bloody secret(Archived by

WebCite

WebCite was an on-demand archive site, designed to digitally preserve scientific and educationally important material on the web by taking snapshots of Internet contents as they existed at the time when a blogger or a scholar cited or quoted ...

®), written by Rory Carroll

Rory Carroll (born 1972) is an Irish journalist working for ''The Guardian'' who has reported from the Balkans, Afghanistan, Iraq, Latin America and Los Angeles. He is the Ireland correspondent for ''The Guardian''. His book on Hugo Chávez, '' ...

, Education, The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers '' The Observer'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the ...

, June 2001 Effie Pedaliu (2004) Britain and the 'Hand-over' of Italian War Criminals to Yugoslavia, 1945–48. Journal of Contemporary History. Vol. 39, No. 4, Special Issue: Collective Memory, pp. 503–529 Fillipo Focardi, a historian at Rome's ''German Historical Institute'', has discovered archived documents showing how Italian civil servants were told to avoid extraditions. A typical instruction was issued by the Italian prime minister, Alcide De Gasperi, reading: "Try to gain time, avoid answering requests." The denial of Italian war crimes was backed up by the Italian state, academe, and media, re-inventing Italy as only a victim of the German Nazism and the post-war Foibe massacres

The foibe massacres (; ; ), or simply the foibe, refers to mass killings both during and after World War II, mainly committed by Yugoslav Partisans and OZNA in the then-Italian territories of Julian March (Karst Region and Istria), Kvarner an ...

.

A number of suspects, known to be on the list of Italian war criminals that Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label= Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavij ...

, Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

and Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

requested an extradition

Extradition is an action wherein one jurisdiction delivers a person accused or convicted of committing a crime in another jurisdiction, over to the other's law enforcement. It is a cooperative law enforcement procedure between the two jurisdi ...

of, at the end of World War II never saw anything like the Nuremberg trial

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945, Nazi Germany invaded ...

, because with the beginning of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

, the British government saw in Pietro Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino (, ; 28 September 1871 – 1 November 1956), was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regime ...

, who was also on the list, a guarantee of an anti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and the ...

post-war Italy. Oliva, Gianni (2006''«Si ammazza troppo poco». I crimini di guerra italiani. 1940–43''

Mondadori, Baldissara, Luca & Pezzino, Paolo (2004). ''Crimini e memorie di guerra: violenze contro le popolazioni e politiche del ricordo'', L'Ancora del Mediterraneo.

Yugoslavia

In April 1941, Italy invaded Yugoslavia, occupying large portions of Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, Montenegro, Serbia and Macedonia, while directly annexing to Italy the Ljubljana Province, Gorski Kotar and Central

In April 1941, Italy invaded Yugoslavia, occupying large portions of Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, Montenegro, Serbia and Macedonia, while directly annexing to Italy the Ljubljana Province, Gorski Kotar and Central Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

, along with most Croatian islands. To suppress the mounting resistance led by the Slovenian

Slovene or Slovenian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Slovenia, a country in Central Europe

* Slovene language, a South Slavic language mainly spoken in Slovenia

* Slovenes, an ethno-linguistic group mainly living in Slovenia

* Sl ...

and Croatian Partisans, the Italians adopted tactics of "summary execution

A summary execution is an execution in which a person is accused of a crime and immediately killed without the benefit of a full and fair trial. Executions as the result of summary justice (such as a drumhead court-martial) are sometimes includ ...

s, hostage-taking, reprisals, internments and the burning of houses and villages.".

In May 1942 Mussolini told Mario Roatta

Mario Roatta (2 February 1887 – 7 January 1968) was an Italian general. After serving in World War I he rose to command the Corpo Truppe Volontarie which assisted Francisco Franco's force during the Spanish Civil War. He was the Deputy Chief o ...

, commander of the Italian 2nd Army, that "the best situation is when the enemy is dead. So we must take numerous hostages and shoot them whenever necessary." To implement this Roatta suggested the closure of the Province of Fiume

The Province of Fiume (or Province of Carnaro) was a province of the Kingdom of Italy from 1924 to 1943, then under control of the Italian Social Republic and German Wehrmacht from 1943 to 1945. Its capital was the city of Fiume. It took the othe ...

and Croatia, the evacuation of people in the east of the former frontiers to a distance of 3–4 km inland, the organization of border patrols to kill anyone attempting to cross, the mass internment of "twenty to thirty thousand persons" to Italian concentration camps

Italian concentration camps include camps from the Italian colonial wars in Africa as well as camps for the civilian population from areas occupied by Italy during World War II. Memory of both camps were subjected to "historical amnesia". The rep ...

, burning down houses, and the confiscation of property from villagers suspected of having contact with Partisans for families of Italian soldiers. He also mentioned the need to extend the plan to Dalmatia and for the construction of concentration camps. Roatta insisted, "If necessary don't shy away from using cruelty. It must be a complete cleansing. We need to intern all the inhabitants and put Italian families in their place."

Italian concentration camps

In the

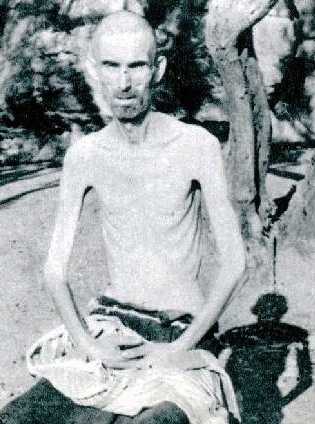

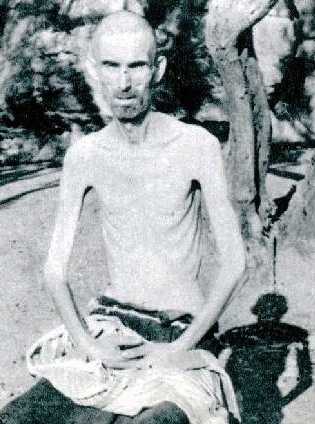

In the Province of Ljubljana The Province of Ljubljana ( it, Provincia di Lubiana, sl, Ljubljanska pokrajina, german: Provinz Laibach) was the central-southern area of Slovenia. In 1941, it was annexed by Fascist Italy, and after 1943 occupied by Nazi Germany. Created on May ...

, alone, the Italians sent some 25,000 to 40,000 Slovene civilians to concentrations camps, which equaled 7.5% to 12% of its total population. The Italians also sent tens-of-thousands of Croats, Serbs, Montenegrins and others to concentration camps, including many women and children. 80,000 people from Dalmatia (12% of the population) passed through various Italian concentration camps. 98,703 Montenegrin civilians (one-third of the entire population of Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = ...

) were sent to Italian concentration camps. The operation, one of the most drastic in Europe, filled up many Italian concentration camps

Italian concentration camps include camps from the Italian colonial wars in Africa as well as camps for the civilian population from areas occupied by Italy during World War II. Memory of both camps were subjected to "historical amnesia". The rep ...

, such as Rab

Rab �âːb( dlm, Arba, la, Arba, it, Arbe, german: Arbey) is an island in the northern Dalmatia region in Croatia, located just off the northern Croatian coast in the Adriatic Sea.

The island is long, has an area of and 9,328 inhabitants (2 ...

, Gonars, Monigo, Renicci di Anghiari

Renicci is a village in the municipality of Anghiari, which was the site of a fascist concentration camp for civilians from Yugoslavia, mostly rounded up by Italian troops in Slovenia and in particular in the then Province of Ljubljana.

It is e ...

, Molat

Molat (pronounced ; it, Melada) is a Croatian island in the Adriatic Sea. It is situated near Zadar, southeast from Ist, separated by Zapuntel strait. It has area of .

The settlements on the island are Molat (population 107), Zapuntel (pop. 42) ...

and elsewhere. Among the 10,619 civilians held in October 1942 in just the Rab concentration camp, 3,413 were women and children, with children accounting for 1,422 of the prisoners. Over 3,500 internees died at Rab alone, including at least 163 children listed by name, giving it a mortality rate of 18%. Concentration camp survivors received no compensation from the Italian state after the war.

Mass killings of civilians and hostages

In retaliation for Partisan actions during the Uprising in Montenegro, Italian forces, under the command of General Alessandro Pirzio Biroli, killed 74 Montenegrin civilians and captured Partisans inPljevlja

Pljevlja ( srp, Пљевља, ) is a town and the center of Pljevlja Municipality located in the northern part of Montenegro. The town lies at an altitude of . In the Middle Ages, Pljevlja had been a crossroad of the important commercial roads an ...

on 2 December 1941. Italian forces committed further massacres on 14 December 1941, in the villages of Babina Vlaka, Jabuka and Mihailovici, destroying homes and killing 120 Montenegrin civilians.

In early July 1942, Italian troops operating opposite Fiume, were reported to have shot and killed 800 Croat and Slovene civilians and burned down 20 houses near Split on the Dalmatian coast. On 12 July 1942, Italian forces killed around 100 Croat civilians in the Podhum massacre

The Podhum massacre was the mass murder of Croat civilians by Italian occupation forces on 12 July 1942, in the village of Podhum, in retaliation for an earlier Partisan attack.

Background

Axis forces, including the Kingdom of Italy, invad ...

, and deported another 889 civilians to concentration camps. Later that month, the Italian Air Force was reported to have practically destroyed four Yugoslav villages near Prozor, killing hundreds of civilians in revenge for a local guerrilla attack that resulted in the death of two high-ranking officers. In the second week of August 1942, Italian troops were reported to have burned down six Croatian villages and shot dead more than 200 civilians in retaliation for guerrilla attacks. In September 1942, the Italian Army was reported to have destroyed 100 villages in Slovenia and killed 7,000 villagers in reprisal for local guerrilla attacks.

On 16 November 1942, after a Partisan attack on a military truck convoy, Italian forces launched a combined and indiscriminate land, air and naval bombardment targeting the small Croatian town of Primošten

Primošten (; it, Capocesto) is a village and municipality in Šibenik-Knin County, Croatia. It is situated in the south, between the cities of Šibenik and Trogir, on the Adriatic coast.

Demographics

The total population of the municipality i ...

in reprisal. Some 150 civilians were killed in the attack, nearby villages were also burned and 200 citizens were arrested.

Italian authorities enacted a quota for civilian hostages to be shot in retaliation for Italian soldiers and citizens killed by Partisan attacks. In Dalmatia, five civilian hostages were to be executed for every Italian civilian killed and twenty civilian hostages were to be executed for every Italian officer or civil servant killed. Hostages were taken from the civilian population and were interned in concentration camps.

In other areas, the quota was more arbitrary. For example, Italian forces ordered the execution of 66 civilian hostages from Šibenik on 22 May 1943, in retaliation for 22 telegraph poles sabotaged by Partisans, a quota of three hostages for each telegraph pole damaged.

In Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = ...

, the hostage quota was higher; in January 1942, the Governor of Montenegro ordered 50 civilian hostages to be executed for every Italian officer killed or wounded, and 10 civilians hostages to be executed for every Italian NCO and regular soldier killed or wounded.

Between 24 April and 24 June 1942, Italian forces executed more than 1,000 hostages from across the Province of Ljubljana. In the Šibenik district, 240 hostages were executed between 23 April and 15 June 1942, a further 470 civilians were killed in reprisals at the same time across other areas of Dalmatia. In late-June 1943, the Governor of Montenegro ordered the execution of 180 hostages from the Bar concentration camp.

On 11 October 1941, governor Giuseppe Bastianini

Giuseppe Bastianini (8 March 1899 – 17 December 1961) was an Italian politician and diplomat. Initially associated with the hard-line elements of the fascist movements he later became a member of the dissident tendency.

Early years

Bastianini ...

, established the Extraordinary Tribunal for Dalmatia, a special judicial body operating within the Governorate of Dalmatia

The Governorate of Dalmatia ( it, Governatorato di Dalmazia) was a territory divided into three provinces of Italy during the Italian Kingdom and Italian Empire epoch. It was created later as an entity in April 1941 at the start of World War II ...

, with the task of judging political crimes

In criminology, a political crime or political offence is an offence involving overt acts or omissions (where there is a duty to act), which prejudice the interests of the state, its government, or the political system. It is to be distinguish ...

and individuals belonging to Communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

organizations. The Tribunal held four trials characterized by a hasty procedure without any guarantee for the accused, imposing forty-eight death sentences, of which thirty-five were executed, as well as thirty-seven prison sentences of different lengths.

A decree given by Mussolini on 24 October 1941, replaced the Extraordinary Tribunal with the Special Court for Dalmatia, which took over the tribunal's functionality and had wide jurisdiction. Like the Extraordinary Tribunal, the Special Court worked quickly, informally and arbitrarily. According to statistics of the Yugoslav State Commission of Crimes of

the Occupier and Their Assistants, a total of 5,000 people became subject to

proceedings in these Italian courts and the courts condemned 500 of them

to death. The remainder were given punishments ranging from long prison sentences, being assigned to forced labour or being sent to concentration camps.

According to statistics collected through 1946 by the Commission for

War Damages on the Territory of the People’s Republic of Croatia, Italian authorities with their collaborators killed 30,795 civilians (not including those killed in concentration camps and prisons) in Dalmatia, Istria, Gorski Kotar and the Croatian Littoral, compared to 9,439 partisans.

In 2012, a Slovenian census determined that the Italian occupiers were responsible for the deaths of 6,400 Slovene civilians.

Other repressive anti-Partisan measures

On their own, or with their Nazi allies, the occupying Italian army undertook many armed actions, including brutal offensives intended to wipe out Partisan resistance. This included

On their own, or with their Nazi allies, the occupying Italian army undertook many armed actions, including brutal offensives intended to wipe out Partisan resistance. This included Case White

Case White (german: Fall Weiss), also known as the Fourth Enemy Offensive ( sh, Četvrta neprijateljska ofenziva/ofanziva), was a combined Axis strategic offensive launched against the Yugoslav Partisans throughout occupied Yugoslavia during ...

in Bosnia, in which German, Italian and allied quisling forces killed 12,000 Partisans, plus 3,370 civilians, while sending 1,722 civilians to concentration camps. During the Case Black

Case Black (german: Fall Schwarz), also known as the Fifth Enemy Offensive ( sh-Latn, Peta neprijateljska ofanziva) in Yugoslav historiography and often identified with its final phase, the Battle of the Sutjeska ( sh-Latn, Bitka na Sutjesci ) ...

offensive, German, Italian and allied troops killed 7,000 Partisans (two-thirds of the total 22,000 Partisan force were killed or wounded), and executed 2,537 civilians.

In Ljubljana Province, in July 1941, the Italian army assembled 80,000 well-armed troops to attack 2,500-3,000 poorly armed Partisans, who had liberated large portions of the Province. Italian general

In Ljubljana Province, in July 1941, the Italian army assembled 80,000 well-armed troops to attack 2,500-3,000 poorly armed Partisans, who had liberated large portions of the Province. Italian general Mario Robotti

Mario Robotti (25 November 1882–1955) was a general in the Royal Italian Army who commanded the XI Corps during the World War II Axis invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941.

He then became military commander in the province of Ljubljana, the Ita ...

issued commands for all persons caught with arms or false identification papers to be shot on the spot, while most other men of military age were to be sent to concentration camps. All buildings from which shots were fired on Italian troops, or in which ammunition was found, or the owners showed hospitality to Partisans, were to be destroyed. Italian troops were ordered to burn crops, kill livestock and burn villages which supported Partisans. To destroy the resistance, the Italian occupiers also completely surrounded the capital city of Ljubljana with barbed wire, bunkers and control points. Civilians, particularly families of partisans and their supporters, were sent by the tens-of-thousands to Italian concentration camps, and in a meeting in Gorizia in July 1942, between Italian generals and Mussolini, they agreed to forcefully deport all 330,000 inhabitants of Ljubljana Province, if necessary, and replace them with Italians.

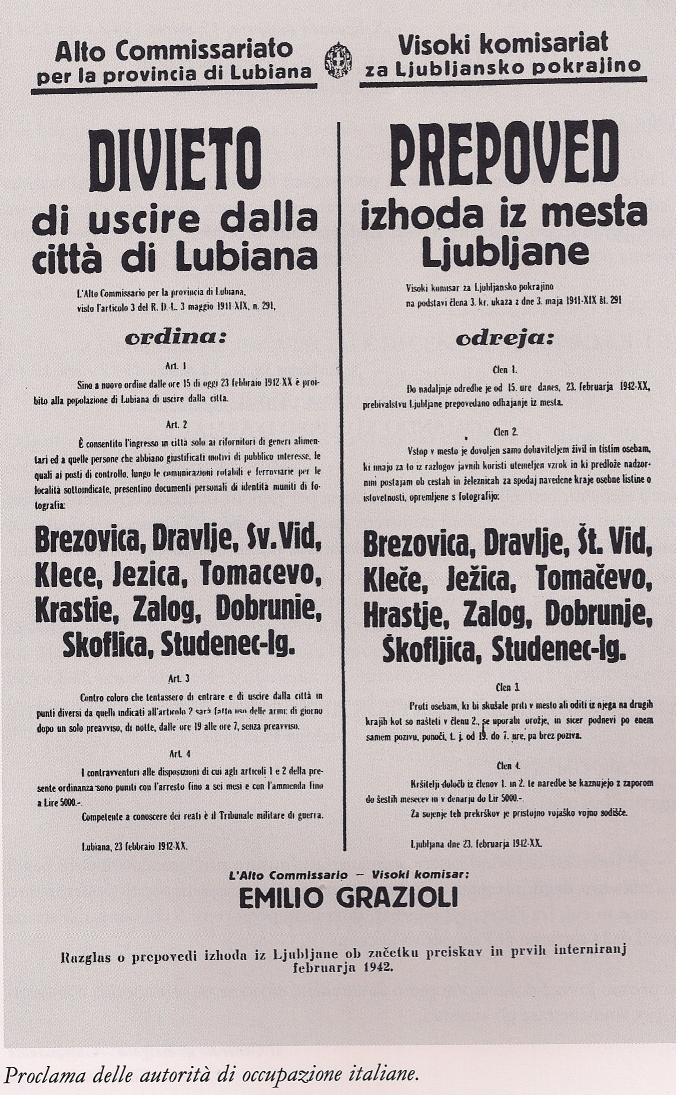

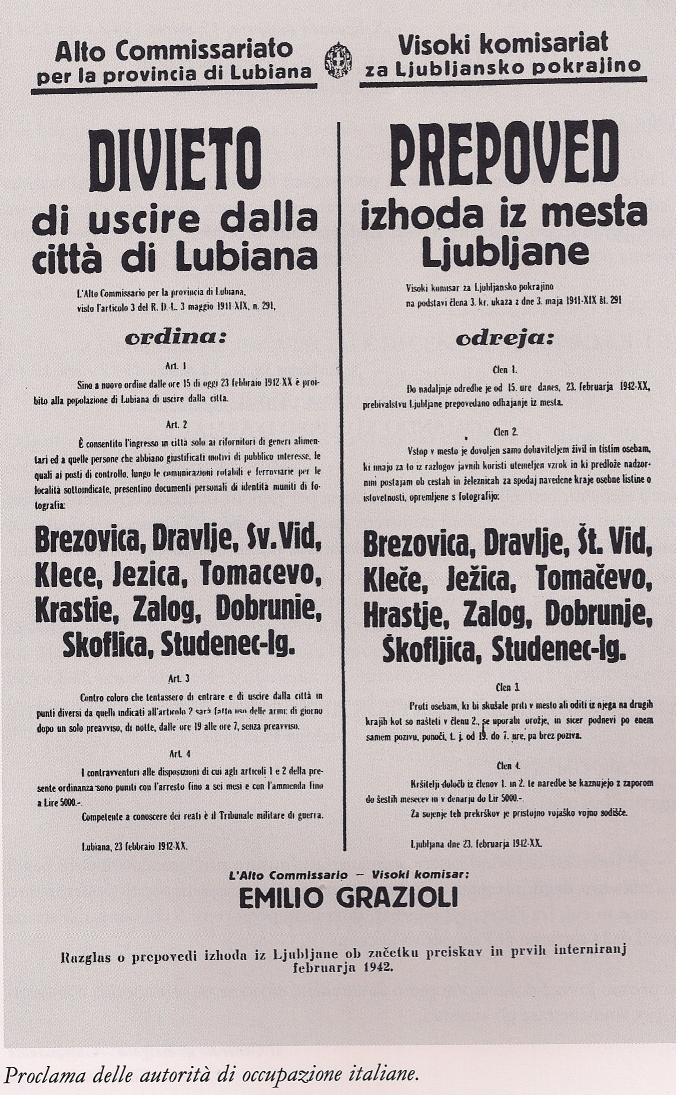

None of the Italians responsible for the many war crimes against Yugoslavs - including Generals Roatta and Robotti, Fascist Commissar Emilio Grazioli, etc - were ever brought to trial.

Greece

A similar phenomenon took place in Greece in the immediate postwar years. The Italian occupation of Greece was often brutal, resulting in reprisals such as the Domenikon Massacre. The Greek government claimed that Italian occupation forces destroyed 110,000 buildings and via various causes inflicted economic damage of $6 billion (1938 exchange rates) while executing 11,000 civilians; in terms of the percentage of direct and indirect destruction this was almost identical to the figures attributed to German occupation forces. The Italians also presided over the

A similar phenomenon took place in Greece in the immediate postwar years. The Italian occupation of Greece was often brutal, resulting in reprisals such as the Domenikon Massacre. The Greek government claimed that Italian occupation forces destroyed 110,000 buildings and via various causes inflicted economic damage of $6 billion (1938 exchange rates) while executing 11,000 civilians; in terms of the percentage of direct and indirect destruction this was almost identical to the figures attributed to German occupation forces. The Italians also presided over the Greek famine

The Great Famine ( el, Μεγάλος Λιμός, and sometimes known as the Grand Famine) was a period of mass starvation during the Axis occupation of Greece, during World War II (1941–1944). The local population suffered greatly during t ...

while occupying the majority of the country, and along with the Germans were responsible for it by initiating a policy of wide-scale plunder of everything of value in Greece, including food for its occupation forces. Ultimately, the Greek famine led to the deaths of 300,000 Greek civilians. Pope Pius XII

Pope Pius XII ( it, Pio XII), born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli (; 2 March 18769 October 1958), was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death in October 1958. Before his e ...

, in a contemporary letter, directly blamed the Fascist Italian government for the deaths in addition to the Germans: "Axis authorities in Greece are robbing the starving population of their entire harvest of corn, grapes, olives, and currants; even vegetables, fish, milk, and butter are being seized... Italy is the occupying power and Italy is responsible for the proper feeding of the Greek people... after the war the story of Greece will be an indelible blot on the good name of Italy, at any rate Fascist Italy."

After two Italian filmmakers were jailed in the 1950s for depicting the Italian invasion of Greece

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

and the subsequent occupation of the country as a "soft war", the Italian public and media were forced to repress their collective memory. The repression of memory led to historical revisionismAlessandra Kersevan 2008: (Editor) Foibe – Revisionismo di stato e amnesie della repubblica. Kappa Vu. Udine. in Italy and in 2003, the Italian media published Silvio Berlusconi

Silvio Berlusconi ( ; ; born 29 September 1936) is an Italian media tycoon and politician who served as Prime Minister of Italy in four governments from 1994 to 1995, 2001 to 2006 and 2008 to 2011. He was a member of the Chamber of Deputies f ...

's statement that Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

only "used to send people on vacation".''Survivors of war camp lament Italy's amnesia''2003,

International Herald Tribune

The ''International Herald Tribune'' (''IHT'') was a daily English-language newspaper published in Paris, France for international English-speaking readers. It had the aim of becoming "the world's first global newspaper" and could fairly be said ...

Albania

Italyinvaded

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing con ...

the Albanian Kingdom on 7 April 1939. Albania was quickly overrun by the 12 April 1939, forcing its ruler, King Zog

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the t ...

, into exile, Albania was then made a part of the Italian Empire

The Italian colonial empire ( it, Impero coloniale italiano), known as the Italian Empire (''Impero Italiano'') between 1936 and 1943, began in Africa in the 19th century and comprised the colonies, protectorates, concessions and dependenci ...

as a protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its in ...

in personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interli ...

with the Italian Crown. Italian citizens began to settle in Albania as colonists

A settler is a person who has migrated to an area and established a permanent residence there, often to colonize the area.

A settler who migrates to an area previously uninhabited or sparsely inhabited may be described as a pioneer.

Settle ...

and to own land so that they could gradually transform it into Italian soil. The Italianization

Italianization ( it, italianizzazione; hr, talijanizacija; french: italianisation; sl, poitaljančevanje; german: Italianisierung; el, Ιταλοποίηση) is the spread of Italian culture, language and identity by way of integration or ass ...

of Albania was one of Mussolini's plans.

From 1940, growing Albanian resistance to Italian rule, led to an increase in repressive and punitive measures against the Albanian population. From 14-18 July 1943, the Italian army conducted a large anti-Partisan operation in villages surrounding the town of Mallakastër

Mallakastër ( sq-definite, Mallakastra) is a region and a municipality in Fier County, southwestern Albania. It was created in 2015 by the merger of the present municipalities Aranitas, Ballsh, Fratar, Greshicë, Hekal, Kutë, Ngraçan, Qendër Du ...

, destroying 80 Albanian villages and killing hundreds of civilians.

According to the Statistics of the Albanian National Institute of Resistance, the Italian occupiers were responsible for 28,000 dead, 12,600 wounded, 43,000 interned in concentration camps, 61,000 homes burned, 850 villages destroyed.

The Holocaust

Libya

After the passing of the anti-SemiticManifesto of Race

The "Manifesto of Race" ( it, "Manifesto della razza", italics=no), otherwise referred to as the Charter of Race or the Racial Manifesto, was a manifesto which was promulgated by the Council of Ministers on the 14th of July 1938, its promulgation ...

in 1938, conditions worsened for the Jews of Libya.

In 1942, 2,600 Jews were sent by Italian authorities to the Giado concentration camp, where they remained until they were liberated by British forces in January 1943. 564 prisoners died from typhus and other privations.

The Soviet Union

In at least one recorded case, Italian forces taking part in theinvasion of the Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

, handed over a captured group of Jews to be killed by a German Einsatzkommando

During World War II, the Nazi German ' were a sub-group of the ' (mobile killing squads) – up to 3,000 men total – usually composed of 500–1,000 functionaries of the SS and Gestapo, whose mission was to exterminate Jews, Polish intellect ...

unit.

Italy

The oppression of Italian Jews began in 1938 with the enactment of Racial Laws of segregation by the fascist regime ofBenito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

. This changed in September 1943, when German forces occupied the country, installed the puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sove ...

of the Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic ( it, Repubblica Sociale Italiana, ; RSI), known as the National Republican State of Italy ( it, Stato Nazionale Repubblicano d'Italia, SNRI) prior to December 1943 but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò ...

(RSI) and immediately began persecuting and deporting the Jews found there.

In November 1943, the Fascist authorities of the RSI declared Italian Jews to be of "enemy nationality" during the Congress of Verona

The Congress of Verona met at Verona on 20 October 1822 as part of the series of international conferences or congresses that opened with the Congress of Vienna in 1814–15, which had instituted the Concert of Europe at the close of the Napol ...

and began to participate actively in the prosecution and arrest of Jews. Initially, after the Italian surrender, the Italian police had only assisted in the round-up of Jews when requested to do so by German authorities. With the Manifest of Verona, in which Jews were declared foreigners, and in times of war enemies, this changed. Police Order No. 5 on November 30, 1943, issued by Guido Buffarini Guidi

Guido Buffarini Guidi (17 August 1895 – 10 July 1945) was an Italian army officer and politician, executed for war crimes in 1945.

Biography

Buffarini Guidi was born in Pisa in 1895. When Italy entered World War I, he volunteered in an ...

, minister of the interior of the RSI, ordered the Italian police to arrest Jews and confiscate their property.

Approximately half of all Jews arrested during the Holocaust in Italy were arrested in 1944 by the Italian police.

Of the estimated 44,500 Jews living in Italy before September 1943, 7,680 were murdered during the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europ ...

(mostly at Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 Nazi concentration camps, concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, occupied Poland (in a portion annexed int ...

), while nearly 37,000 survived.

List of Italian war criminals

This is a working list of Italian high-ranking military personnel or other officials involved in acts of war. It includes also such personnel of lower rank that were accused of grave breaches of the laws of war. Inclusion of a person does not imply that the person was qualified as a war criminal by a court of justice. As noted in the relevant section, very few cases have been brought to court due to diplomatic activities of, notably, the government of the United Kingdom and subsequent general abolition. The criterion for inclusion in the list is the existence of reliable documented sources. *Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

: In 1936, during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a war of aggression which was fought between Fascist Italy (1922–1943), Italy and Ethiopian Empire, Ethiopia from October 1935 to February 1937. In Ethio ...

, Mussolini ordered the manufacturing/purchase of hundreds of tons of yperite

Mustard gas or sulfur mustard is a chemical compound belonging to a family of cytotoxic and blister agents known as mustard agents. The name ''mustard gas'' is technically incorrect: the substance, when dispersed, is often not actually a gas, b ...

, phosgene

Phosgene is the organic chemical compound with the formula COCl2. It is a toxic, colorless gas; in low concentrations, its musty odor resembles that of freshly cut hay or grass. Phosgene is a valued and important industrial building block, esp ...

, and fire munitions in the form of aerial bombs and artillery and mortar shells.

* Pietro Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino (, ; 28 September 1871 – 1 November 1956), was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regime ...

: In 1936, during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a war of aggression which was fought between Fascist Italy (1922–1943), Italy and Ethiopian Empire, Ethiopia from October 1935 to February 1937. In Ethio ...

, Badoglio approved, as commander in chief of the Italian army, the use of poisonous gas against enemy troops.

* Rodolfo Graziani

Rodolfo Graziani, 1st Marquis of Neghelli (; 11 August 1882 – 11 January 1955), was a prominent Italian military officer in the Kingdom of Italy's '' Regio Esercito'' ("Royal Army"), primarily noted for his campaigns in Africa before and durin ...

: In 1950, a military tribunal sentenced Graziani to prison for a term of 19 years (but released after a few months) as punishment for his collaboration with the Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in N ...

, when he was Minister of Defense of the Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic ( it, Repubblica Sociale Italiana, ; RSI), known as the National Republican State of Italy ( it, Stato Nazionale Repubblicano d'Italia, SNRI) prior to December 1943 but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò ...

. He was a key figure in the Pacification of Libya

The Second Italo-Senussi War, also referred to as the Pacification of Libya, was a conflict that occurred during the Italian colonization of Libya between Italian military forces (composed mainly of colonial troops from Libya, Eritrea, and ...

and authorized the mass killing of Ethiopians known as ''Yekatit 12

Yekatit 12 () is a date in the Ge'ez calendar which refers to the massacre and imprisonment of Ethiopians by the Italian occupation forces following an attempted assassination of Marshal Rodolfo Graziani, Marquis of Negele, Viceroy of Italian ...

''.

* Alessandro Pirzio Biroli: The Governor of the Italian governorate of Montenegro, he ordered that fifty Montenegrin civilians be executed for every Italian killed, and ten be executed for every Italian wounded.

* Mario Roatta

Mario Roatta (2 February 1887 – 7 January 1968) was an Italian general. After serving in World War I he rose to command the Corpo Truppe Volontarie which assisted Francisco Franco's force during the Spanish Civil War. He was the Deputy Chief o ...

: In 1941–1943, during the 22-month existence of the Province of Ljubljana The Province of Ljubljana ( it, Provincia di Lubiana, sl, Ljubljanska pokrajina, german: Provinz Laibach) was the central-southern area of Slovenia. In 1941, it was annexed by Fascist Italy, and after 1943 occupied by Nazi Germany. Created on May ...

, Roatta ordered the deportation of 25,000 people, which equaled 7.5% of the total population. The operation, one of the most drastic in Europe, filled up Italian concentration camps

Italian concentration camps include camps from the Italian colonial wars in Africa as well as camps for the civilian population from areas occupied by Italy during World War II. Memory of both camps were subjected to "historical amnesia". The rep ...

on the island of Rab, in Gonars, Monigo (Treviso), Renicci d'Anghiari, Chiesanuova and elsewhere. The survivors received no compensation from the Italian state after the war. He had, as the commander of the 2nd Italian Army in Province of Ljubljana, ordered besides internments also summary executions, hostage-taking, and burning of houses and villages,James H. Burgwyn (2004)General Roatta's war against the partisans in Yugoslavia: 1942

Journal of Modern Italian Studies, Volume 9, Number 3, pp. 314–329(16) for which after the war the Yugoslav government sought unsuccessfully to have him extradited for war crimes. He was quoted as saying "''Non dente per dente, ma testa per dente''" ("''Not a tooth for tooth but a head for a tooth''"), while Robotti was quoted as saying "''Non si ammazza abbastanza!''" ("''There are not enough killings''") in 1942. "On 1 March 1942, he ''(Roatta)'' circulated a pamphlet entitled '3C' among his commanders that spelled out military reform and draconian measures to intimidate the Slav populations into silence by means of summary executions, hostage-taking, reprisals, internments and the burning of houses and villages. By his reckoning, military necessity knew no choice, and law required only lip service. Roatta's merciless suppression of partisan insurgency was not mitigated by his having saved the lives of both Serbs and Jews from the persecution of Italy's allies Germany and Croatia. Under his watch, the 2nd Army's record of violence against the Yugoslav population easily matched the German. Tantamount to a declaration of war on civilians, Roatta's '3C' pamphlet involved him in war crimes." One of Roatta's soldiers wrote home on July 1, 1942: "We have destroyed everything from top to bottom without sparing the innocent. We kill entire families every night, beating them to death or shooting them." As noted by Minister of Foreign Affairs in Mussolini government,

Galeazzo Ciano

Gian Galeazzo Ciano, 2nd Count of Cortellazzo and Buccari ( , ; 18 March 1903 – 11 January 1944) was an Italian diplomat and politician who served as Foreign Minister in the government of his father-in-law, Benito Mussolini, from 1936 until 1 ...

, when describing a meeting with secretary general of the Fascist party who wanted Italian army to kill all Slovenes:

* Mario Robotti

Mario Robotti (25 November 1882–1955) was a general in the Royal Italian Army who commanded the XI Corps during the World War II Axis invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941.

He then became military commander in the province of Ljubljana, the Ita ...

, Commander of the Italian 11th Division in Slovenia and Croatia, issued an order in line with a directive received from Mussolini in June 1942: "I would not be opposed to all (''sic'') Slovenes being imprisoned and replaced by Italians. In other words, we should take steps to ensure that political and ethnic frontiers coincide.", which qualifies as ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population transfer ...

policy.

* Nicola Bellomo was an Italian general who was tried and found guilty for killing a British prisoner of war and wounding another in 1941. He was one of the few Italians to be executed for war crimes by the Allies, and the only one executed by the British military.

* Italo Simonitti, a captain in the Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic ( it, Repubblica Sociale Italiana, ; RSI), known as the National Republican State of Italy ( it, Stato Nazionale Repubblicano d'Italia, SNRI) prior to December 1943 but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò ...

's 4th ''Monterosa'' Alpine

Alpine may refer to any mountainous region. It may also refer to:

Places Europe

* Alps, a European mountain range

** Alpine states, which overlap with the European range

Australia

* Alpine, New South Wales, a Northern Village

* Alpine National P ...

division, was executed for his involvement in the 1945 execution of an American prisoner. He was the only Italian war criminal to be executed by the U.S. military. Simonitti's subordinate, Benedetto Pilon, received a life sentence. He was later transferred to Italian custody, but freed under an amnesty from Minister of Justice

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

Attilio Piccioni in January 1951.

* Pietro Caruso

Pietro Caruso (10 November 1899 in Maddaloni – 22 September 1944 in Rome) was an Italian Fascist and head of the Rome police in 1944.

Born in Campania in 1899, he fought in the Bersaglieri in the final months of World War I and participate ...

was chief of the Fascist

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

police in Rome while it was occupied by the Germans. He helped organize the Ardeatine massacre

The Ardeatine massacre, or Fosse Ardeatine massacre ( it, Eccidio delle Fosse Ardeatine), was a mass killing of 335 civilians and political prisoners carried out in Rome on 24 March 1944 by German occupation troops during the Second World War ...

in March 1944. After Rome was liberated by the Allies he was tried that September and subsequently executed by the co-belligerent Italian government.

* Guido Buffarini Guidi

Guido Buffarini Guidi (17 August 1895 – 10 July 1945) was an Italian army officer and politician, executed for war crimes in 1945.

Biography

Buffarini Guidi was born in Pisa in 1895. When Italy entered World War I, he volunteered in an ...

was the Minister of the Interior for the Italian Social Republic; shortly after the end of the war in Europe he was found guilty of war crimes and executed by the co-belligerent government.

* Pietro Koch

Pietro Koch (18 August 1918 – 4 June 1945) was an Italian soldier and leader of the Banda Koch, a group notorious for its anti-partisan activity in the Republic of Salò.

Biography

The son of an Imperial German Navy officer, Koch was born in Be ...

was head of the ''Banda Koch'', a special task force of the '' Corpo di Polizia Repubblicana'' dedicated to hunting down partisans and rounding up deportees. His ruthless extremism was cause for concern even to his fellow fascists, who had him arrested in October 1944. When he came into Allied captivity he was convicted of war crimes and executed.

A number of names of Italians can be found in the CROWCASS list established by the Anglo-American Allies of the individuals wanted by Yugoslavia and Greece for war crimes.The Central Registry of War Criminals and Security Suspects, Consolidated Wanted Lists, Part 2 - Non-Germans only (March 1947), Uckfield 2005 (Naval & University Press); pp. 56–74The Central Registry of War Criminals and Security Suspects, Supplementary Wanted List No. 2, Part 2 - Non Germans (September 1947), Uckfield 2005 (Naval & University Press); pp. 81–82

See also

* Italian Fascism * Italian Fascism and racism *Anti-Italianism

Anti-Italianism or Italophobia is a negative attitude regarding Italian people or people with Italian ancestry, often expressed through the use of prejudice, discrimination or stereotypes. Its opposite is Italophilia.

In the United States

Ant ...

* Axis war crimes in Italy

*The Holocaust in Italy

The Holocaust in Italy was the persecution, deportation, and murder of Jews between 1943 and 1945 in the Italian Social Republic, the part of the Kingdom of Italy occupied by Nazi Germany after the Italian surrender on September 8, 1943, during ...

*Internment of Italian Americans

The internment of Italian Americans refers to the government's internment of Italian nationals in the United States during World War II. As was customary after Italy and the US were at war, they were classified as "enemy aliens" and some were de ...

*Italian Civil War

The Italian Civil War ( Italian: ''Guerra civile italiana'', ) was a civil war in the Kingdom of Italy fought during World War II by Italian Fascists against the Italian partisans (mostly politically organized in the National Liberation Committ ...

*List of war crimes

This article lists and summarizes the war crimes that have violated the laws and customs of war since the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907.

Since many war crimes are not prosecuted (due to lack of political will, lack of effective procedur ...

*Allied war crimes during World War II

Allied war crimes include both alleged and legally proven violations of the laws of war by the Allies of World War II against either civilians or military personnel of the Axis powers. At the end of World War II, many trials of Axis war criminals ...

*British war crimes

British war crimes are acts by the armed forces of the United Kingdom that have violated the laws and customs of war since the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. Such acts have included the summary executions of prisoners of war and unarmed s ...

*German war crimes

The governments of the German Empire and Nazi Germany (under Adolf Hitler) ordered, organized and condoned a substantial number of war crimes, first in the Herero and Namaqua genocide and then in the First and Second World Wars. The most no ...

*Japanese war crimes

The Empire of Japan committed war crimes in many Asian-Pacific countries during the period of Japanese imperialism, primarily during the Second Sino-Japanese and Pacific Wars. These incidents have been described as an "Asian Holocaust". Som ...

*Soviet war crimes

The war crimes and crimes against humanity which were perpetrated by the Soviet Union and its armed forces from 1919 to 1991 include acts which were committed by the Red Army (later called the Soviet Army) as well as acts which were committ ...

*United States war crimes

United States war crimes are violations of the law of war committed by members of the United States Armed Forces after the signing of the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 and the Geneva Conventions. The United States prosecutes offenders throu ...

References

Sources

Giuseppe Piemontese (1946): Twenty-nine months of Italian occupation of the Province of Ljubljana

* Lidia Santarelli: "Muted violence: Italian war crimes in occupied Greece", ''Journal of Modern Italian Studies'', September 2004, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 280–299(20); Routledge, part of the Taylor & Francis Group * Effie Pedaliu (2004): Britain and the ‘Hand-Over’ of Italian War Criminals to Yugoslavia, 1945–48, ''Journal of Contemporary History'', Vol. 39, No. 4, 503–529 * Pietro Brignoli (1973):

messa per i miei fucilati

', Longanesi & C., Milano, * H. James Burgwyn (2004): "General Roatta's war against the partisans in Yugoslavia: 1942", ''Journal of Modern Italian Studies'', September vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 314–329(16) * Gianni Oliva (2006): 'Si ammazza troppo poco'. I crimini di guerra italiani 1940–43. ('There are too few killings'. Italian war crimes 1940–43), Mondadori, *

Alessandra Kersevan

Alessandra Kersevan (born 18 December 1950) is a historian, author and editor living and working in Udine.

She researches Italian modern history, including the Italian resistance movement and Italian war crimes.

She is the editor of a group cal ...

(2003): " Un campo di concentramento fascista. Gonars 1942–1943", Comune di Gonars e Ed. Kappa Vu,

* Alessandra Kersevan

Alessandra Kersevan (born 18 December 1950) is a historian, author and editor living and working in Udine.

She researches Italian modern history, including the Italian resistance movement and Italian war crimes.

She is the editor of a group cal ...

(2008): '' Lager italiani. Pulizia etnica e campi di concentramento fascisti per civili jugoslavi 1941–1943''. Editore Nutrimenti,

* Alessandra Kersevan

Alessandra Kersevan (born 18 December 1950) is a historian, author and editor living and working in Udine.

She researches Italian modern history, including the Italian resistance movement and Italian war crimes.

She is the editor of a group cal ...

2008: (Editor) Foibe – Revisionismo di stato e amnesie della repubblica. Kappa Vu. Udine.

* Luca Baldissara, Paolo Pezzino (2004). Crimini e memorie di guerra: violenze contro le popolazioni e politiche del ricordo.

* ''The Central Registry of War Criminals and Security Suspects (CROWCASS) - Consolidated Wanted Lists'' (1947), Uckfield 2005 (Naval & University Press, facsimile edition of the original document at the National Archives in Kew/London)

Italian Crimes In Yugoslavia (Yugoslav Information Office – London 1945)

Mass internment of civil population under inhuman conditions – Italian concentration camps

{{World War II War crimes committed by country

War

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

de:Italienische Kriegsverbrechen in Jugoslawien