Israel Eldad on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

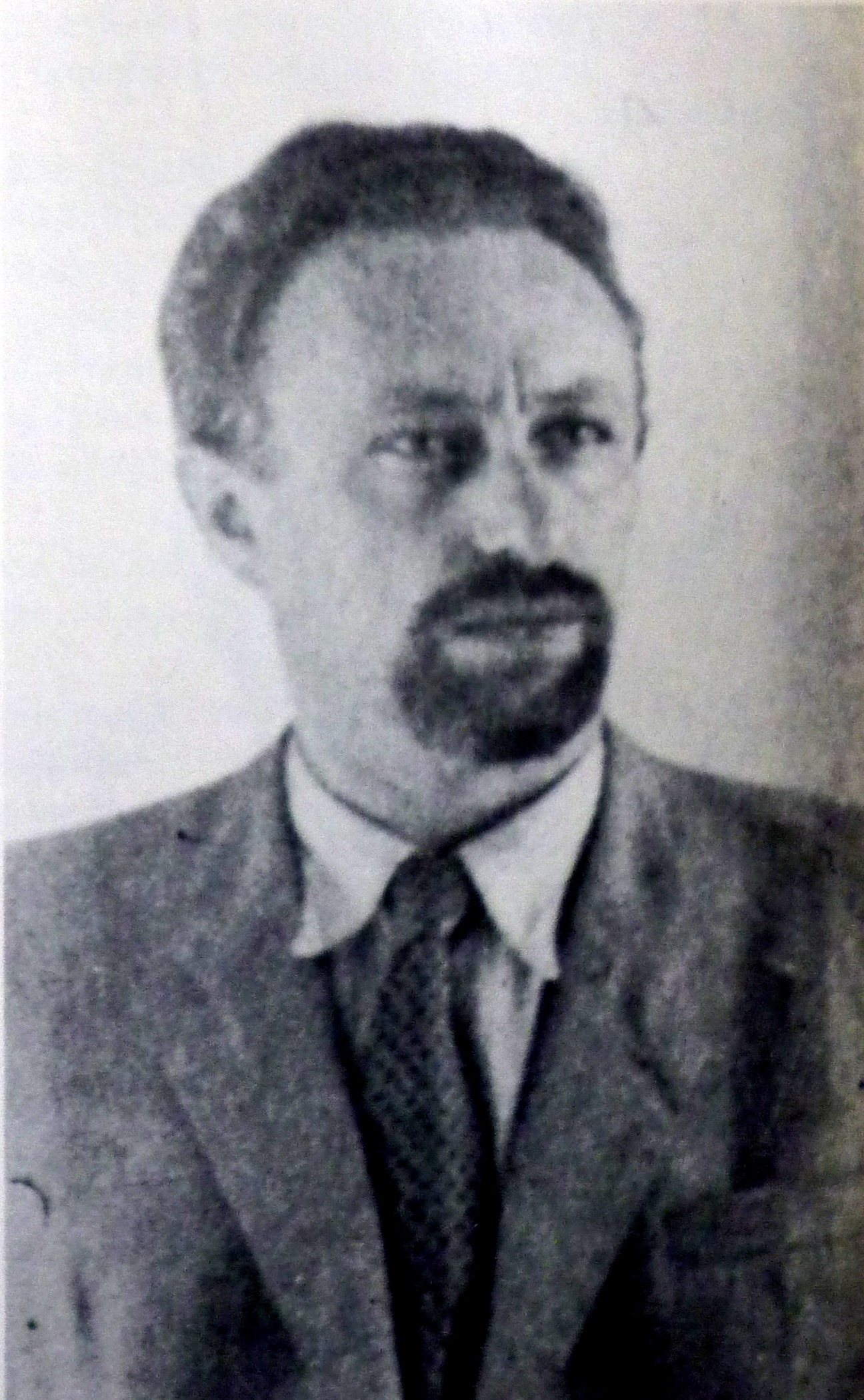

Israel Eldad () (11 November 1910 – 22 January 1996), was an Israeli

Eldad was arrested by the British when trying to flee from a Tel Aviv apartment; he was injured in a fall from a water pipe, and imprisoned in Jerusalem in a body cast. He continued his political and philosophical writing from Cell 18 of the hospital ward at the Jerusalem Central Prison. Eventually, in June 1946, Eldad healed enough to escape while on a visit in a dentist's clinic, from which several Lehi fighters spirited him away.

Eldad was arrested by the British when trying to flee from a Tel Aviv apartment; he was injured in a fall from a water pipe, and imprisoned in Jerusalem in a body cast. He continued his political and philosophical writing from Cell 18 of the hospital ward at the Jerusalem Central Prison. Eventually, in June 1946, Eldad healed enough to escape while on a visit in a dentist's clinic, from which several Lehi fighters spirited him away.

The Lehi veterans organized politically as the

The Lehi veterans organized politically as the

The book ''Stern: The Man and His Gang'' by Zev Golan has a biography of Eldad and a detailed comparison of his political ideas and goals with those of other Lehi leaders.

The book ''Stern: The Man and His Gang'' by Zev Golan has a biography of Eldad and a detailed comparison of his political ideas and goals with those of other Lehi leaders.

Revisionist Zionist

Revisionist Zionism is an ideology developed by Ze'ev Jabotinsky, who advocated a "revision" of the " practical Zionism" of David Ben-Gurion and Chaim Weizmann which was focused on the settling of ''Eretz Yisrael'' ( Land of Israel) by independe ...

philosopher and member of the Jewish underground group Lehi

Lehi (; he, לח"י – לוחמי חרות ישראל ''Lohamei Herut Israel – Lehi'', "Fighters for the Freedom of Israel – Lehi"), often known pejoratively as the Stern Gang,"This group was known to its friends as LEHI and to its enemie ...

in Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine ( ar, فلسطين الانتدابية '; he, פָּלֶשְׂתִּינָה (א״י) ', where "E.Y." indicates ''’Eretz Yiśrā’ēl'', the Land of Israel) was a geopolitical entity established between 1920 and 1948 ...

.

Biography

Israel Scheib (later Eldad) was born in 1910 in Pidvolochysk,Galicia

Galicia may refer to:

Geographic regions

* Galicia (Spain), a region and autonomous community of northwestern Spain

** Gallaecia, a Roman province

** The post-Roman Kingdom of the Suebi, also called the Kingdom of Gallaecia

** The medieval King ...

in a traditional Jewish home. The Scheibs wandered as refugees during the First World War. In 1918, in Lvov

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in western Ukraine, and the seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is one of the main cultural centres of Ukrain ...

, young Scheib witnessed a funeral procession for Jews murdered in a pogrom. After high school, Scheib enrolled at the Rabbinical Seminary of Vienna for religious studies and the University of Vienna

The University of Vienna (german: Universität Wien) is a public research university located in Vienna, Austria. It was founded by Duke Rudolph IV in 1365 and is the oldest university in the German-speaking world. With its long and rich hi ...

for secular studies. He completed his doctorate on "The Voluntarism of Eduard von Hartmann, Based on Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer ( , ; 22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher. He is best known for his 1818 work ''The World as Will and Representation'' (expanded in 1844), which characterizes the phenomenal world as the pr ...

," but never took his rabbinical exams at the seminary.

Meanwhile, he attended, with his father, a protest demonstration in front of the local British Consulate following the 1929 Arab riots in Palestine. The next year he read a poem by Uri Zvi Greenberg, "I'll Tell It to a Child," about a messiah who cannot redeem his people because they are not ready to accept redemption. Two or three years later, Scheib met Greenberg at a speech Greenberg was giving entitled “The Land of Israel Is in Flames.”

Pedagogic and academic career 1937-1939

Scheib's first job after graduation was high school teaching in Volkovisk. Scheib joined the staff of the Teachers Seminary inVilna

Vilnius ( , ; see also other names) is the capital and largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the municipality of Vilnius). The population of Vilnius's functional urba ...

in 1937 while this city was part of Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

, where he stayed for two years.

Zionist activism

In Poland

During that time he rose in theBetar

The Betar Movement ( he, תנועת בית"ר), also spelled Beitar (), is a Revisionist Zionist youth movement founded in 1923 in Riga, Latvia, by Vladimir (Ze'ev) Jabotinsky. Chapters sprang up across Europe, even during World War II. After t ...

ranks to the position of regional staff officer. In 1938, at the Third Betar Conference in Warsaw, when the Revisionist leader Ze'ev Jabotinsky

Ze'ev Jabotinsky ( he, זְאֵב זַ׳בּוֹטִינְסְקִי, ''Ze'ev Zhabotinski'';, ''Wolf Zhabotinski'' 17 October 1880 – 3 August 1940), born Vladimir Yevgenyevich Zhabotinsky, was a Russian Jewish Revisionist Zionist leade ...

attacked the militant stance of Poland's Betar leader Menachem Begin

Menachem Begin ( ''Menaḥem Begin'' (); pl, Menachem Begin (Polish documents, 1931–1937); ''Menakhem Volfovich Begin''; 16 August 1913 – 9 March 1992) was an Israeli politician, founder of Likud and the sixth Prime Minister of Israel. ...

, Scheib spoke in Begin's defense.

The next year, when the Second World War broke out, Scheib and Begin escaped together from Warsaw. Begin was arrested by the Soviet police in the middle of a chess game with Scheib, and it was several years before their next encounter.

Eldad immigrated

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not natives or where they do not possess citizenship in order to settle as permanent residents or naturalized citizens. Commuters, tourists, and ...

to Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine ( ar, فلسطين الانتدابية '; he, פָּלֶשְׂתִּינָה (א״י) ', where "E.Y." indicates ''’Eretz Yiśrā’ēl'', the Land of Israel) was a geopolitical entity established between 1920 and 1948 ...

in 1941.

Leader of Lehi in Mandatory Palestine

Eladad and Begin met again in British-ruled Mandatory Palestine, where Scheib was already a leader of the Lehi underground and Begin would soon command theIrgun

Irgun • Etzel

, image = Irgun.svg , image_size = 200px

, caption = Irgun emblem. The map shows both Mandatory Palestine and the Emirate of Transjordan, which the Irgun claimed in its entirety for a future Jewish state. The acronym "Etzel" i ...

. The Lehi was at that point waging a violent struggle for freedom from British rule and the Irgun would, under Begin, soon join the revolt in hopes of turning Palestine into a Jewish state.

Scheib adopted several aliases while living underground, including "Sambatyon" and "Eldad". He worked in 1942 directly with Lehi founder Avraham Stern

Avraham Stern ( he, אברהם שטרן, ''Avraham Shtern''), alias Yair ( he, יאיר; December 23, 1907 – February 12, 1942) was one of the leaders of the Jewish paramilitary organization Irgun. In September 1940, he founded a breakaway m ...

. After Stern's killing by the British, Eldad became one of a triumvirate of Lehi commanders, working together with Natan Yellin-Mor

Nathan Yellin-Mor ( he, נתן ילין-מור, Nathan Friedman-Yellin; 28 June 1913 – 18 February 1980) was a Revisionist Zionist activist, Lehi leader and Israeli politician. In later years, he became a leader of the Israeli peace camp, a ...

and future prime minister Yitzhak Shamir

Yitzhak Shamir ( he, יצחק שמיר, ; born Yitzhak Yezernitsky; October 22, 1915 – June 30, 2012) was an Israeli politician and the seventh Prime Minister of Israel, serving two terms, 1983–1984 and 1986–1992. Before the establishment ...

.Moshe and Tova Svorai, ''Me'Etzel Le'Lechi'', 1989, pp. 419-422 (Hebrew) and Israel Eldad, ''Maaser Rishon'', pp. 133-145 (Hebrew) Yellin-Mor was the diplomatic "foreign minister," Shamir the operations man, and Eldad the ideologue. For the next six years Eldad wrote articles for various underground newspapers, some of which he edited. Eldad also wrote some of the speeches delivered in court by Lehi defendants.

Eldad was arrested by the British when trying to flee from a Tel Aviv apartment; he was injured in a fall from a water pipe, and imprisoned in Jerusalem in a body cast. He continued his political and philosophical writing from Cell 18 of the hospital ward at the Jerusalem Central Prison. Eventually, in June 1946, Eldad healed enough to escape while on a visit in a dentist's clinic, from which several Lehi fighters spirited him away.

Eldad was arrested by the British when trying to flee from a Tel Aviv apartment; he was injured in a fall from a water pipe, and imprisoned in Jerusalem in a body cast. He continued his political and philosophical writing from Cell 18 of the hospital ward at the Jerusalem Central Prison. Eventually, in June 1946, Eldad healed enough to escape while on a visit in a dentist's clinic, from which several Lehi fighters spirited him away.

During the 1948 War

During the1948 Palestine war

The 1948 Palestine war was fought in the territory of what had been, at the start of the war, British-ruled Mandatory Palestine. It is known in Israel as the War of Independence ( he, מלחמת העצמאות, ''Milkhemet Ha'Atzma'ut'') and ...

, Eldad continued to be active as a co-leader of Lehi. Acting in this role, Eldad participated in September 1948 in ordering the assassination of Folke Bernadotte

Folke Bernadotte, Count of Wisborg (2 January 1895 – 17 September 1948) was a Swedish nobleman and diplomat. In World War II he negotiated the release of about 31,000 prisoners from German concentration camps, including 450 Danish Jews fr ...

, a United Nations mediator, as he subsequently admitted.

During the war Eldad was critical of Menachem Begin's Irgun for them, as he thought, not fighting against the Israel Defence Forces

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; he, צְבָא הַהֲגָנָה לְיִשְׂרָאֵל , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the State of Israel. It consists of three service branch ...

during the Altalena Affair

The ''Altalena'' Affair was a violent confrontation that took place in June 1948 by the newly created Israel Defense Forces against the Irgun (also known as IZL), one of the Jewish paramilitary groups that were in the process of merging to form ...

. He was also critical of the IDF for not fighting harder to conquer Jerusalem's Old City, and critical of Lehi fighters who did not rush to fight in Jerusalem. Towards the end of the war, Eldad disguised himself as a foreign journalist in order to sneak past Israeli military roadblocks and join the battle for Jerusalem.

Political career

The Lehi veterans organized politically as the

The Lehi veterans organized politically as the Fighters' List

The Fighters' List ( he, רשימת הלוחמים, ''Reshimat HaLohmim'') was a political party in Israel.

History

The Fighters' List grew out of Lehi, a militant Revisionist paramilitary organisation that operated in Palestine during the Ma ...

. The party won one seat in the election for the First Knesset

Constituent Assembly elections were held in newly independent Israel on 25 January 1949. Voter turnout was 86.9%. Two days after its first meeting on 14 February 1949, legislators voted to change the name of the body to the Knesset (Hebrew: כ ...

and dissolved afterwards. At one party meeting, Eldad lectured on ''Sulam'', Jacob's ladder

Jacob's Ladder ( he, סֻלָּם יַעֲקֹב ) is a ladder leading to heaven that was featured in a dream the biblical Patriarch Jacob had during his flight from his brother Esau in the Book of Genesis (chapter 28).

The significance of th ...

(based on , where Jacob

Jacob (; ; ar, يَعْقُوب, Yaʿqūb; gr, Ἰακώβ, Iakṓb), later given the name Israel, is regarded as a patriarch of the Israelites and is an important figure in Abrahamic religions, such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. ...

dreams of a ladder uniting heaven and earth).

Eldad taught Bible and Hebrew literature in an Israeli high school until Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion

David Ben-Gurion ( ; he, דָּוִד בֶּן-גּוּרִיּוֹן ; born David Grün; 16 October 1886 – 1 December 1973) was the primary national founder of the State of Israel and the first prime minister of Israel. Adopting the nam ...

intervened and had him dismissed. Ben-Gurion was afraid Eldad would imbue the students with his Lehi ideology. Eldad went to court and won, but found few people willing to hire him after Ben-Gurion had labeled him a danger to the state.

In 1962, Eldad was made a lecturer at the Technion in Haifa

Haifa ( he, חֵיפָה ' ; ar, حَيْفَا ') is the third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropol ...

. He taught there for twenty years. Starting from 1982 Eldad was a lecturer at the Ariel University Center of Samaria

Ariel University ( he, אוניברסיטת אריאל), previously a public college known as the Ariel University Center of Samaria, is an Israeli university located in the urban Israeli settlement of Ariel in the West Bank.

The college preced ...

.

Literary career

For 14 years he published a revolutionary journal, ''Sulam''. Eldad spent half of 1949 writing his memoirs, entitled ''Maaser Rishon''. He wrote histories of underground battles, a biography of the mayor of Ramat Gan, a newspaper-style review of Jewish history called ''Chronicles'', a book of Bible commentary, ''Hegionot Mikra'', weekly newspaper columns, and many more books, encyclopedia entries and other works. In 1988, Eldad was awardedTel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( he, תֵּל־אָבִיב-יָפוֹ, translit=Tēl-ʾĀvīv-Yāfō ; ar, تَلّ أَبِيب – يَافَا, translit=Tall ʾAbīb-Yāfā, links=no), often referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the G ...

's Bialik Prize

The Bialik Prize is an annual literary award given by the municipality of Tel Aviv, Israel, for significant accomplishments in Hebrew literature. The prize is named in memory of Israel's national poet Hayyim Nahman Bialik

Hayim Nahman Bialik ...

for his contributions to Israeli thought.

By the 1990s, Eldad was known as the doyen of Israeli nationalists. Much of his work has been translated into English, mostly by Zev Golan. Among his works: ''Chronicles'' . ''The Jewish Revolution'' appeared in 1971, and was reissued in 2007. ''Free Jerusalem'' includes a chapter by Eldad ("Meanwhile, A European Interlude") about Polish Jewry on the eve of war. ''Israel: The Road to Full Redemption'', a translation of an article in ''Sulam'', was published in 1961 and is today a virtually unobtainable brochure. A website is devoted to disseminating articles by Eldad and his underground colleagues. His memoirs of the time he led the Lehi underground organisation, ''The First Tithe'', were translated and first published in 2008. ''God, Man and Nietzsche'' includes a lengthy examination of Eldad's philosophy of history and excerpts from an article about Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his car ...

written by Eldad in the underground.

When he died on the first day of the Hebrew month of Shevat, in January 1996, his funeral was attended by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu

Benjamin "Bibi" Netanyahu (; ; born 21 October 1949) is an Israeli politician who served as the ninth prime minister of Israel from 1996 to 1999 and again from 2009 to 2021. He is currently serving as Leader of the Opposition and Chairman of ...

, former Lehi commander and prime minister Yitzhak Shamir

Yitzhak Shamir ( he, יצחק שמיר, ; born Yitzhak Yezernitsky; October 22, 1915 – June 30, 2012) was an Israeli politician and the seventh Prime Minister of Israel, serving two terms, 1983–1984 and 1986–1992. Before the establishment ...

and Knesset

The Knesset ( he, הַכְּנֶסֶת ; "gathering" or "assembly") is the unicameral legislature of Israel. As the supreme state body, the Knesset is sovereign and thus has complete control of the entirety of the Israeli government (wit ...

Speaker Dov Shilansky

Dov Shilansky ( he, דב שילנסקי, 21 March 1924 – 9 December 2010) was an Israeli lawyer, politician and Speaker of the Knesset from 1988 to 1992.

Biography

Dov Shilansky (born Berelis Šilianskis) was born in Šiauliai, Lithuania. ...

. Eldad was buried on the Mount of Olives

The Mount of Olives or Mount Olivet ( he, הַר הַזֵּיתִים, Har ha-Zeitim; ar, جبل الزيتون, Jabal az-Zaytūn; both lit. 'Mount of Olives'; in Arabic also , , 'the Mountain') is a mountain ridge east of and adjacent to Jeru ...

, at the foot of the grave of his mentor and friend, Uri Zvi Greenberg.

Views and opinions

The book ''Stern: The Man and His Gang'' by Zev Golan has a biography of Eldad and a detailed comparison of his political ideas and goals with those of other Lehi leaders.

The book ''Stern: The Man and His Gang'' by Zev Golan has a biography of Eldad and a detailed comparison of his political ideas and goals with those of other Lehi leaders.

Jewish state

Eldad did not believe that the creation of the state of Israel was the goal of Zionism. He considered the state a tool to be used in realizing the true goal of Zionism, which he called ''Malkhut Yisrael'', "the Kingdom of Israel". Eldad sought what he referred to as national redemption, meaning a sovereign Jewish kingdom in the biblical borders of Israel, with all the world's Jews living there, and the JewishTemple

A temple (from the Latin ) is a building reserved for spiritual rituals and activities such as prayer and sacrifice. Religions which erect temples include Christianity (whose temples are typically called churches), Hinduism (whose temples ...

rebuilt in Jerusalem.

Jewish diaspora

Eldad steadfastly refused to give legitimacy to any Jewish presence in theDiaspora

A diaspora ( ) is a population that is scattered across regions which are separate from its geographic place of origin. Historically, the word was used first in reference to the dispersion of Greeks in the Hellenic world, and later Jews after ...

, which he felt was doomed to extinction. Nonetheless, in his view of history, past generations of Jews in exile from the Land of Israel

The Land of Israel () is the traditional Jewish name for an area of the Southern Levant. Related biblical, religious and historical English terms include the Land of Canaan, the Promised Land, the Holy Land, and Palestine (see also Isr ...

were not denigrated as passive sufferers, but were considered creative players in history.Zev Golan, ''God, Man and Nietzsche'', p. 113

Awards and recognition

* In 1977, Eldad was awarded theTchernichovsky Prize

Tchernichovsky Prize is an Israeli prize awarded to individuals for exemplary works of translation into Hebrew.

History

The Tchernichovsky Prize is awarded by the municipality of Tel Aviv-Yafo.

for exemplary translation.

* In 1988, he was the co-recipient (jointly with Zvi Meir Rabinovitz) of the Bialik Prize

The Bialik Prize is an annual literary award given by the municipality of Tel Aviv, Israel, for significant accomplishments in Hebrew literature. The prize is named in memory of Israel's national poet Hayyim Nahman Bialik

Hayim Nahman Bialik ...

for Jewish thought.

* In 1990, he received the Yakir Yerushalayim Yakir Yerushalayim ( he, יַקִּיר יְרוּשָׁלַיִם; en, Worthy Citizen of Jerusalem) is an annual citizenship prize in Jerusalem, inaugurated in 1967.

The prize is awarded annually by the municipality of the City of Jerusalem to o ...

(Worthy Citizen of Jerusalem) award from the city of Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

. City of Jerusalem official website

Many of Eldad's political and philosophical teachings continue to be espoused by the Magshimey Herut

World Magshimey Herut ( he, מגשימי חרות עולמי, lit=world achievers of liberty), sometimes called Magshimey Herut or World MH, is a Zionist young adult movement founded in 1999 by a group of Jewish activists based on the ideals of ali ...

(achievers of liberty) organization, the Zionist Freedom Alliance, and by the Hatikva political party, the latter one led by Eldad's son Aryeh. The Israeli settlement

Israeli settlements, or Israeli colonies, are civilian communities inhabited by Israeli citizens, overwhelmingly of Jewish ethnicity, built on lands occupied by Israel in the 1967 Six-Day War. The international community considers Israeli se ...

Kfar Eldad

Kfar Eldad ( he, כְּפַר אֶלְדָּד) is an Israeli settlement and a community settlement in the West Bank, south of Jerusalem. It is administered by the Gush Etzion Regional Council. The settlement is in the vicinity of Herodium and over ...

was named after him.

Published works

* ''The Jewish Revolution: Jewish Statehood'' (Israel: Gefen Publishing House, 2007), * ''Maaser Rishon''. Originally published in 1950 in Hebrew. English translation: ''The First Tithe'' (Tel Aviv: Jabotinsky Institute, 2008), * ''Israel: The Road to Full Redemption'' (New York: Futuro Press, 1961)See also

*List of Bialik Prize recipients

The Bialik Prize is an annual literary award given by the municipality of Tel Aviv, Israel, for significant accomplishments in Hebrew literature. The prize is named in memory of Israel's national poet Hayyim Nahman Bialik

Hayim Nahman Bialik ...

References

Further reading

* Ada Amichal Yevin, ''Sambatyon'' (Israel: Bet El, 1995) (Hebrew) * Zev Golan, ''Free Jerusalem: Heroes, Heroines and Rogues Who Created the State of Israel'' (Israel: Devora, 2003), * Zev Golan, ''God, Man and Nietzsche: A Startling Dialogue between Judaism and Modern Philosophers'' (New York: iUniverse, 2007), {{DEFAULTSORT:Eldad, Israel 1910 births 1996 deaths 20th-century Israeli philosophers Jewish philosophers Israeli philosophers Philosophers of Judaism Modern Hebrew writers Zionist activists Lehi (militant group) Polish emigrants to Mandatory Palestine 20th-century Israeli Jews Jews from Galicia (Eastern Europe) People from Pidvolochysk University of Vienna alumni Burials at the Jewish cemetery on the Mount of Olives Betar members