Isma'ilism ( ar, الإسماعيلية, al-ʾIsmāʿīlīyah) is a branch or sub-sect of

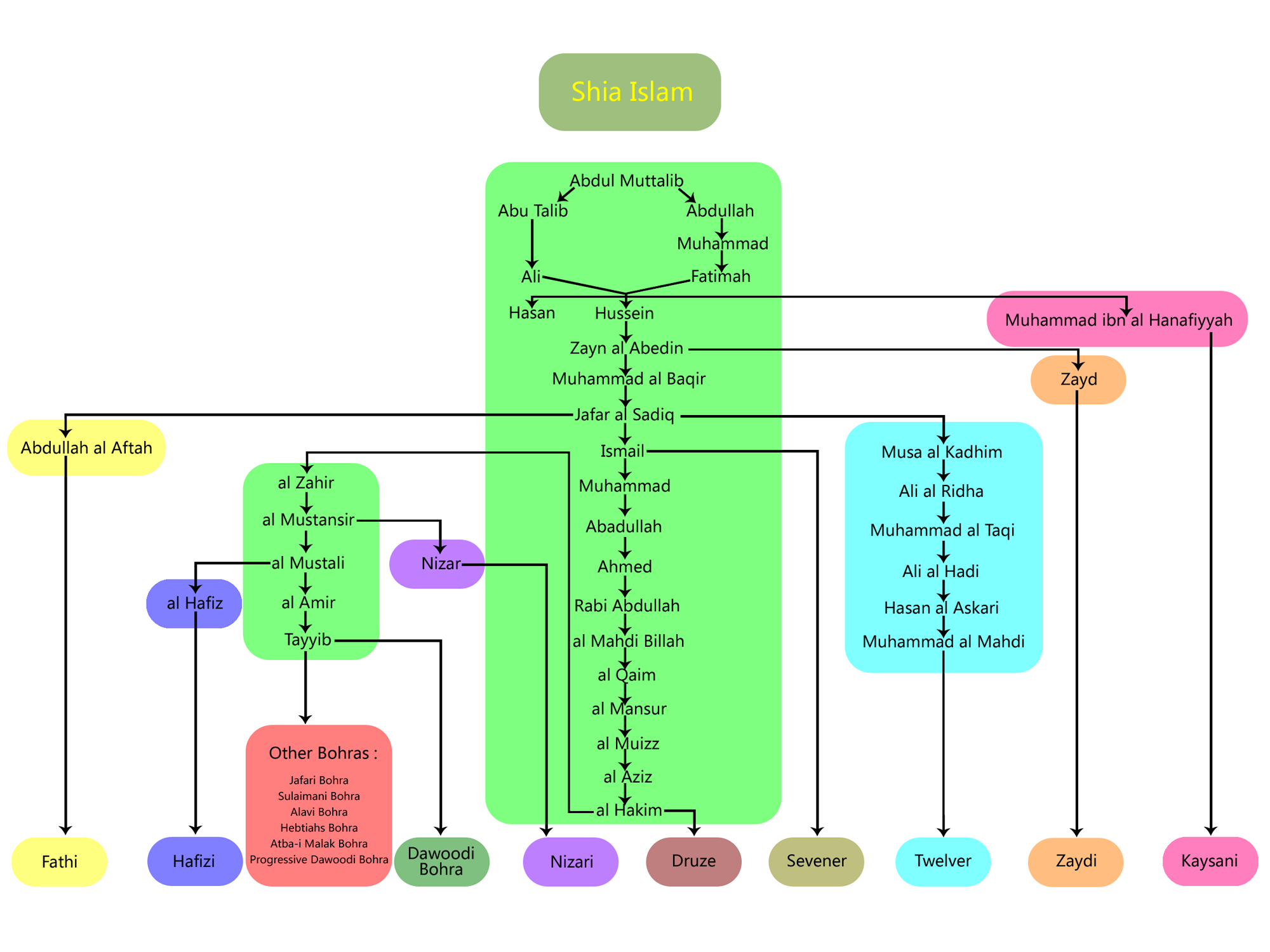

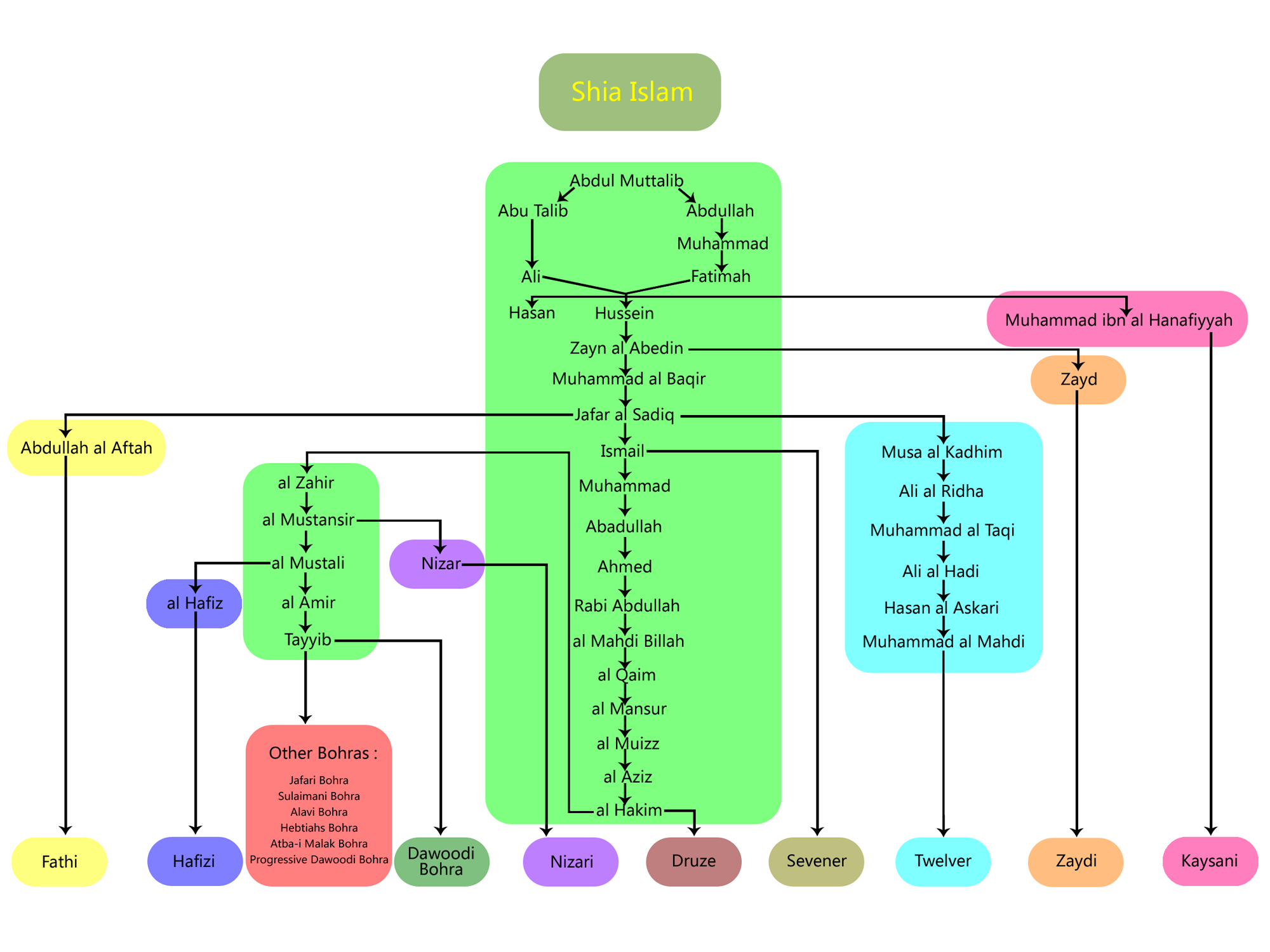

Shia Islam

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that the Islamic prophet Muhammad designated ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his successor (''khalīfa'') and the Imam (spiritual and political leader) after him, mos ...

. The Isma'ili () get their name from their acceptance of Imam

Isma'il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor (

imām) to

Ja'far al-Sadiq

Jaʿfar ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAlī al-Ṣādiq ( ar, جعفر بن محمد الصادق; 702 – 765 CE), commonly known as Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq (), was an 8th-century Shia Muslim scholar, jurist, and theologian.. He was the founder of th ...

, wherein they differ from the

Twelver Shia

Twelver Shīʿīsm ( ar, ٱثْنَا عَشَرِيَّة; '), also known as Imāmīyyah ( ar, إِمَامِيَّة), is the largest branch of Shīʿa Islam, comprising about 85 percent of all Shīʿa Muslims. The term ''Twelver'' refers t ...

, who accept

Musa al-Kadhim

Musa ibn Ja'far al-Kazim ( ar, مُوسَىٰ ٱبْن جَعْفَر ٱلْكَاظِم, Mūsā ibn Jaʿfar al-Kāẓim), also known as Abū al-Ḥasan, Abū ʿAbd Allāh or Abū Ibrāhīm, was the seventh Imam in Twelver Shia Islam, after hi ...

, the younger brother of Isma'il, as the

true Imām.

Isma'ilism rose at one point to become the largest branch of Shia Islam, climaxing as a political power with the

Fatimid Caliphate

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Ismaili Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east. The Fatimids, a ...

in the 10th through 12th centuries.

Ismailis believe in the

oneness of God

Tawhid ( ar, , ', meaning "unification of God in Islam (Allāh)"; also romanized as ''Tawheed'', ''Tawhid'', ''Tauheed'' or ''Tevhid'') is the indivisible oneness concept of monotheism in Islam. Tawhid is the religion's central and single mo ...

, as well as the closing of

divine revelation with

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mon ...

, whom they see as "the final Prophet and Messenger of God to all humanity". The Isma'ili and the Twelvers both accept the same six initial Imams; the Isma'ili accept Isma'il ibn Jafar as the seventh Imam.

After the death of

Muhammad ibn Isma'il

Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Ismāʿīl (), also known in his own time as al-Maymūn and hence sometimes incorrectly identified as Maymūn al-Qaddāḥ, was the son of Isma'il ibn Ja'far; he was an Ismāʿīlī Imam. The majority of Ism� ...

in the 8th century CE, the teachings of Ismailism further transformed into the belief system as it is known today, with an explicit concentration on the deeper, esoteric meaning () of the Islamic religion. With the eventual development of

Usuli

Usulis ( ar, اصولیون, fa, اصولیان) are the majority Twelver Shi'a Muslim group. They differ from their now much smaller rival Akhbari group in favoring the use of ''ijtihad'' (i.e., reasoning) in the creation of new rules of ''fiq ...

sm and

Akhbari

The ʾAkhbāri's ( ar, أخباریون, fa, اخباریان) are a minority of Twelver Shia Muslims who reject the use of reasoning in deriving verdicts, and believe in Quran and Hadith.

The term ʾAkhbāri's (from ''khabāra'', news or r ...

sm into the more literalistic () oriented, Shia Islam developed into two separate directions: the metaphorical Ismaili,

Alevi

Alevism or Anatolian Alevism (; tr, Alevilik, ''Anadolu Aleviliği'' or ''Kızılbaşlık''; ; az, Ələvilik) is a local Islamic tradition, whose adherents follow the mystical Alevi Islamic ( ''bāṭenī'') teachings of Haji Bektash Veli, w ...

,

Bektashi,

Alian, and

Alawite

The Alawis, Alawites ( ar, علوية ''Alawīyah''), or pejoratively Nusayris ( ar, نصيرية ''Nuṣayrīyah'') are an ethnoreligious group that lives primarily in Levant and follows Alawism, a sect of Islam that originated from Shia Isl ...

groups focusing on the

mystical

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning. It may also refer to the attainment of insight in u ...

path and nature of

God, along with the "Imam of the Time" representing the manifestation of esoteric truth and intelligible divine reality, with the more literalistic

Usuli

Usulis ( ar, اصولیون, fa, اصولیان) are the majority Twelver Shi'a Muslim group. They differ from their now much smaller rival Akhbari group in favoring the use of ''ijtihad'' (i.e., reasoning) in the creation of new rules of ''fiq ...

and

Akhbari

The ʾAkhbāri's ( ar, أخباریون, fa, اخباریان) are a minority of Twelver Shia Muslims who reject the use of reasoning in deriving verdicts, and believe in Quran and Hadith.

The term ʾAkhbāri's (from ''khabāra'', news or r ...

groups focusing on divine law (

sharia

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

) and the deeds and sayings (

sunnah

In Islam, , also spelled ( ar, سنة), are the traditions and practices of the Islamic prophet Muhammad that constitute a model for Muslims to follow. The sunnah is what all the Muslims of Muhammad's time evidently saw and followed and passed ...

) of Muhammad and

the Twelve Imams who were guides and a

light

Light or visible light is electromagnetic radiation that can be perceived by the human eye. Visible light is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400–700 nanometres (nm), corresponding to frequencies of 750–420 t ...

to God.

Isma'ili thought is heavily influenced by

neoplatonism

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some ...

.

The larger sect of Ismaili are the

Nizari

The Nizaris ( ar, النزاريون, al-Nizāriyyūn, fa, نزاریان, Nezāriyān) are the largest segment of the Ismaili Muslims, who are the second-largest branch of Shia Islam after the Twelvers. Nizari teachings emphasize independent ...

s, who recognize

Aga Khan IV

Shāh Karim al-Husayni (born 13 December 1936), known by the religious title Mawlānā Hazar Imam by his Ismaili followers and elsewhere as Aga Khan IV, is the 49th and current Imam of Nizari Ismailis, a denomination within Shia Islam. He ha ...

[Aga Khan IV](_blank)

as the 49th hereditary Imam, while other groups are known as the

Tayyibi branch. The biggest Ismaili community is in

Gorno-Badakhshan

Gorno-Badakhshan, officially the Badakhshan Mountainous Autonomous Region,, abbr. / is an autonomous region in eastern Tajikistan, in the Pamir Mountains. It makes up nearly forty-five percent of the country's land area, but only two percen ...

,

but Isma'ilis can be found in

Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes the fo ...

,

Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is borde ...

,

Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

,

Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast and ...

,

Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus lie ...

,

Malaysia

Malaysia ( ; ) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federal constitutional monarchy consists of thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two regions: Peninsular Malaysia and Borneo's East Mal ...

,

Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

,

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

,

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the fifth-largest country in Asia, the second-largest in the Ara ...

,

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

,

Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

,

Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

,

Kuwait

Kuwait (; ar, الكويت ', or ), officially the State of Kuwait ( ar, دولة الكويت '), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated in the northern edge of Eastern Arabia at the tip of the Persian Gulf, bordering Iraq to Iraq–Ku ...

,

East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territories make up Eastern Africa:

Due to the historica ...

,

Angola

, national_anthem = "Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordinat ...

,

Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mo ...

, and

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

, and have in recent years emigrated to

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

,

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

,

Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

,

New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

, the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

, and

Trinidad and Tobago

Trinidad and Tobago (, ), officially the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, is the southernmost island country in the Caribbean. Consisting of the main islands Trinidad and Tobago, and numerous much smaller islands, it is situated south of ...

.

History

Succession crisis

Ismailism shares its beginnings with other early Shia sects that emerged during the succession crisis that spread throughout the early Muslim community. From the beginning, the Shia asserted the right of

Ali, cousin of

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mon ...

, to have both political and spiritual control over the community. This also included his two sons, who were the grandsons of Muhammad through his daughter

Fatimah

Fāṭima bint Muḥammad ( ar, فَاطِمَة ٱبْنَت مُحَمَّد}, 605/15–632 CE), commonly known as Fāṭima al-Zahrāʾ (), was the daughter of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and his wife Khadija. Fatima's husband was Ali, ...

.

The conflict remained relatively peaceful between the partisans of Ali and those who asserted a semi-democratic system of electing caliphs, until the third of the

Rashidun caliphs,

Uthman

Uthman ibn Affan ( ar, عثمان بن عفان, ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān; – 17 June 656), also spelled by Colloquial Arabic, Turkish and Persian rendering Osman, was a second cousin, son-in-law and notable companion of the Islamic prop ...

was killed, and Ali, with popular support, ascended to the caliphate.

Soon after his ascendancy,

Aisha

Aisha ( ar, , translit=ʿĀʾisha bint Abī Bakr; , also , ; ) was Muhammad's third and youngest wife. In Islamic writings, her name is thus often prefixed by the title "Mother of the Believers" ( ar, links=no, , ʾumm al- muʾminīn), referr ...

, the third of Muhammad's wives, claimed along with Uthman's tribe, the

Ummayads, that Ali should take (blood for blood) from the people responsible for Uthman's death. Ali voted against it, as he believed that the situation at the time demanded a peaceful resolution of the matter. Though both parties could rightfully defend their claims, due to escalated misunderstandings, the

Battle of the Camel

The Battle of the Camel, also known as the Battle of Jamel or the Battle of Basra, took place outside of Basra, Iraq, in 36 AH (656 CE). The battle was fought between the army of the fourth caliph Ali, on one side, and the rebel army led by ...

was fought and Aisha was defeated, but was respectfully escorted to Medina by Ali.

Following this battle,

Muawiya

Mu'awiya I ( ar, معاوية بن أبي سفيان, Muʿāwiya ibn Abī Sufyān; –April 680) was the founder and first caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate, ruling from 661 until his death. He became caliph less than thirty years after the dea ...

, the

Umayyad governor of Syria, also staged a revolt under the same pretences. Ali led his forces against Muawiya until the side of Muawiya held copies of the

Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , ...

against their spears and demanded that the issue be decided by Islam's holy book. Ali accepted this, and an arbitration was done which ended in his favor.

A group among Ali's army believed that subjecting his legitimate authority to arbitration was tantamount to apostasy, and abandoned his forces. This group was known as the

Khawarij

The Kharijites (, singular ), also called al-Shurat (), were an Islamic sect which emerged during the First Fitna (656–661). The first Kharijites were supporters of Ali who rebelled against his acceptance of arbitration talks to settle the ...

and Ali wished to defeat their forces before they reached the cities, where they would be able to blend in with the rest of the population. While he was unable to do this, he nonetheless defeated their forces in subsequent battles.

Regardless of these defeats, the Kharijites survived and became a violently problematic group in Islamic history. After plotting an assassination against Ali, Muawiya, and the arbitrator of their conflict, Ali was successfully assassinated in 661 CE, and the Imāmate passed on to his son

Hasan and then later his son

Husayn, or according to the Nizari Isma'ili, the Imamate passed to Hasan, who was an Entrusted Imam ( ar, الإمام المستودع, al-imām al-mustawdaʿ), and afterward to Husayn who was the Permanent Imam ( ar, الإمام المستقر, al-imām al-mustaqar). The Entrusted Imam is an Imam in the full sense except that the lineage of the Imamate must continue through the Permanent Imam. However, the political caliphate was soon taken over by Muawiya, the only leader in the empire at that time with an army large enough to seize control.

Even some of Ali's early followers regarded him as "an absolute and divinely guided leader", whose demands of his followers were "the same kind of loyalty that would have been expected for the Prophet". For example, one of Ali's supporters who also was devoted to Muhammad said to him: "our opinion is your opinion and we are in the palm of your right hand." The early followers of Ali seem to have taken his guidance as "right guidance" deriving from Divine support. In other words, Ali's guidance was seen to be the expression of God's will and the Quranic message. This spiritual and absolute authority of Ali was known as , and it was inherited by his successors, the Imams.

In the 1st century after Muhammad, the term was not specifically defined as " of the Prophet", but was used in connection to Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and some Umayyad Caliphs. The idea of , or traditions ascribed to Muhammad, was not mainstream, nor was criticised. Even the earliest legal texts by Malik b. Anas and Abu Hanifa employ many methods including analogical reasoning and opinion and do not rely exclusively on . Only in the 2nd century does the Sunni jurist al-Shafi'i first argue that only the sunnah of Muhammad should be a source of law, and that this is embodied in s. It would take another one hundred years after al-Shafi'i for Sunni Muslim jurists to fully base their methodologies on prophetic s. Meanwhile, Imami Shia Muslims followed the Imams' interpretations of Islam as normative without any need for s and other sources of Sunni law such as analogy and opinion.

Karbala and afterward

The Battle of Karbala

After the death of Imam Hasan, Imam Husayn and his family were increasingly worried about the religious and political persecution that was becoming commonplace under the reign of Muawiya's son,

Yazid. Amidst this turmoil in 680, Husayn along with the women and children of his family, upon receiving invitational letters and gestures of support by Kufis, wished to go to

Kufa

Kufa ( ar, الْكُوفَة ), also spelled Kufah, is a city in Iraq, about south of Baghdad, and northeast of Najaf. It is located on the banks of the Euphrates River. The estimated population in 2003 was 110,000. Currently, Kufa and Najaf a ...

and confront Yazid as an intercessor on part of the citizens of the empire. However, he was stopped by Yazid's army in

Karbala

Karbala or Kerbala ( ar, كَرْبَلَاء, Karbalāʾ , , also ;) is a city in central Iraq, located about southwest of Baghdad, and a few miles east of Lake Milh, also known as Razzaza Lake. Karbala is the capital of Karbala Governor ...

during the month of

Muharram

Muḥarram ( ar, ٱلْمُحَرَّم) (fully known as Muharram ul Haram) is the first month of the Islamic calendar. It is one of the four sacred months of the year when warfare is forbidden. It is held to be the second holiest month after ...

. His family was starved and deprived of water and supplies, until eventually the army came in on the tenth day and martyred Husayn and his companions, and enslaved the rest of the women and family, taking them to Kufa.

This battle would become extremely important to the Shia psyche. The

Twelvers

Twelver Shīʿīsm ( ar, ٱثْنَا عَشَرِيَّة; '), also known as Imāmīyyah ( ar, إِمَامِيَّة), is the largest branch of Shīʿa Islam, comprising about 85 percent of all Shīʿa Muslims. The term ''Twelver'' refers t ...

as well as

Musta'li

The Musta‘lī ( ar, مستعلي) are a branch of Isma'ilism named for their acceptance of al-Musta'li as the legitimate nineteenth Fatimid caliph and legitimate successor to his father, al-Mustansir Billah. In contrast, the Nizari—the other ...

Isma'ili still mourn this event during an occasion known as

Ashura

Ashura (, , ) is a day of commemoration in Islam. It occurs annually on the 10th of Muharram, the first month of the Islamic calendar. Among Shia Muslims, Ashura is observed through large demonstrations of high-scale mourning as it marks ...

.

The

Nizari

The Nizaris ( ar, النزاريون, al-Nizāriyyūn, fa, نزاریان, Nezāriyān) are the largest segment of the Ismaili Muslims, who are the second-largest branch of Shia Islam after the Twelvers. Nizari teachings emphasize independent ...

Isma'ili, however, do not mourn this in the same way because of the belief that the light of the Imam never dies but rather passes on to the succeeding Imām, making mourning arbitrary. However, during commemoration they do not have any celebrations in

Jamatkhana

Jamatkhana (from fa, جماعت خانه , literally "congregational place") is an amalgamation derived from the Arabic word ''jama‘a'' (gathering) and the Persian word ''khana'' (house, place). It is a term used by some Muslim communities ar ...

during Muharram and may have announcements or sessions regarding the tragic events of

Karbala

Karbala or Kerbala ( ar, كَرْبَلَاء, Karbalāʾ , , also ;) is a city in central Iraq, located about southwest of Baghdad, and a few miles east of Lake Milh, also known as Razzaza Lake. Karbala is the capital of Karbala Governor ...

. Also, individuals may observe Muharram in a wide variety of ways. This respect for Muharram does not include self-flagellation and beating because they feel that harming one's body is harming a gift from

Allah

Allah (; ar, الله, translit=Allāh, ) is the common Arabic word for God. In the English language, the word generally refers to God in Islam. The word is thought to be derived by contraction from '' al- ilāh'', which means "the god", a ...

.

The beginnings of Ismāʿīlī Daʿwah

After being set free by Yazid,

Zaynab bint Ali

Zaynab bint Ali ( ar, زَيْنَب بِنْت عَلِيّ, ', ), was the eldest daughter of Ali, the fourth Rashidun Caliphate, Rashidun caliph () and the first Imamate in Shia doctrine, Shia Imam, and Fatima, the daughter of the Muhammad, Is ...

, the daughter of

Fatimah

Fāṭima bint Muḥammad ( ar, فَاطِمَة ٱبْنَت مُحَمَّد}, 605/15–632 CE), commonly known as Fāṭima al-Zahrāʾ (), was the daughter of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and his wife Khadija. Fatima's husband was Ali, ...

and

Ali and the sister of Hasan and Husayn, started to spread the word of Karbala to the Muslim world, making speeches regarding the event. This was the first organized

daʿwah of the Shia, which would later develop into an extremely spiritual institution for the Ismāʿīlīs.

After the poisoning of

Ali ibn Husayn Zayn al-Abidin

ʿAlī ibn al-Ḥusayn Zayn al-ʿĀbidīn ( ar, علي بن الحسين زين العابدين), also known as al-Sajjād (, ) or simply as Zayn al-ʿĀbidīn (), , was an Imam in Shiʻi Islam after his father Husayn ibn Ali, his uncle Hasan ...

by

Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik

Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik ( ar, هشام بن عبد الملك, Hishām ibn ʿAbd al-Malik; 691 – 6 February 743) was the tenth Umayyad caliph, ruling from 724 until his death in 743.

Early life

Hisham was born in Damascus, the administra ...

in 713, the first succession crisis of the Shia arose with

Zayd ibn ʻAlī's companions and the

Zaydīs who claimed

Zayd ibn ʻAlī as the Imām, whilst the rest of the Shia upheld

Muhammad al-Baqir

Muḥammad al-Bāqir ( ar, مُحَمَّد ٱلْبَاقِر), with the full name Muḥammad ibn ʿAlī ibn al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib, also known as Abū Jaʿfar or simply al-Bāqir () was the fifth Imam in Shia Islam, succee ...

as the Imām. The Zaidis argued that any

sayyid

''Sayyid'' (, ; ar, سيد ; ; meaning 'sir', 'Lord', 'Master'; Arabic plural: ; feminine: ; ) is a surname of people descending from the Islamic prophet Muhammad through his grandsons, Hasan ibn Ali and Husayn ibn Ali, sons of Muhamm ...

or "descendant of Muhammad through Hasan or Husayn" who rebelled against tyranny and the injustice of his age could be the Imām. The Zaidis created the first Shia states in Iran, Iraq, and Yemen.

In contrast to his predecessors, Muhammad al-Baqir focused on academic Islamic scholarship in

Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the Holiest sites in Islam, second-holiest city in Islam, ...

, where he promulgated his teachings to many Muslims, both Shia and non-Shia, in an extremely organized form of Daʿwah. In fact, the earliest text of the Ismaili school of thought is said to be the ''

Umm al-kitab'' (The Archetypal Book), a conversation between Muhammad al-Baqir and three of his disciples.

This tradition would pass on to his son,

Ja'far al-Sadiq

Jaʿfar ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAlī al-Ṣādiq ( ar, جعفر بن محمد الصادق; 702 – 765 CE), commonly known as Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq (), was an 8th-century Shia Muslim scholar, jurist, and theologian.. He was the founder of th ...

, who inherited the Imāmate on his father's death in 743. Ja'far al-Sadiq excelled in the scholarship of the day and had many pupils, including three of the four founders of the Sunni

madhhab

A ( ar, مذهب ', , "way to act". pl. مَذَاهِب , ) is a school of thought within '' fiqh'' (Islamic jurisprudence).

The major Sunni Mathhab are Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i and Hanbali.

They emerged in the ninth and tenth centurie ...

s.

However, following al-Sadiq's poisoning in 765, a fundamental split occurred in the community.

Ismaʻil ibn Jafar, who at one point was appointed by his father as the next Imam, appeared to have predeceased his father in 755. While Twelvers argue that either he was never heir apparent or he truly predeceased his father and hence

Musa al-Kadhim

Musa ibn Ja'far al-Kazim ( ar, مُوسَىٰ ٱبْن جَعْفَر ٱلْكَاظِم, Mūsā ibn Jaʿfar al-Kāẓim), also known as Abū al-Ḥasan, Abū ʿAbd Allāh or Abū Ibrāhīm, was the seventh Imam in Twelver Shia Islam, after hi ...

was the true heir to the Imamate, the Ismāʿīlīs argue that either the death of Ismaʻil was staged in order to protect him from Abbasid persecution or that the Imamate passed to Muhammad ibn Ismaʻil in lineal descent.

Ascension of the Dais

For some partisans of Isma'il, the Imamate ended with Isma'il ibn Ja'far. Most Ismailis recognized Muhammad ibn Ismaʻil as the next Imam and some saw him as the expected

Mahdi

The Mahdi ( ar, ٱلْمَهْدِيّ, al-Mahdī, lit=the Guided) is a messianic figure in Islamic eschatology who is believed to appear at the end of times to rid the world of evil and injustice. He is said to be a descendant of Muhammad w ...

that Ja'far al-Sadiq had preached about. However, at this point the Isma'ili Imams according to the

Nizari

The Nizaris ( ar, النزاريون, al-Nizāriyyūn, fa, نزاریان, Nezāriyān) are the largest segment of the Ismaili Muslims, who are the second-largest branch of Shia Islam after the Twelvers. Nizari teachings emphasize independent ...

and

Mustaali found areas where they would be able to be safe from the recently founded

Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttal ...

, which had defeated and seized control from the Umayyads in 750 CE.

At this point, some of the Isma'ili community believed that Muhammad ibn Isma'il had gone into

the Occultation

Occultation ( ar, غَيْبَة, ') in Shia Islam refers to the eschatological belief that Mahdi, a descendant of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, has already been born and subsequently concealed, but will reemerge to establish justice and peace ...

and that he would one day return. A small group traced the Imamate among Muhammad ibn Isma'il's lineal descendants. With the status and location of the Imams not known to the community, the concealed Isma'ili Imams began to propagate the faith through

Da'iyyun from its base in Syria. This was the start of the spiritual beginnings of the Daʿwah that would later play important parts in the all Ismaili branches, especially the Nizaris and the Musta'lis.

The Da'i was not a missionary in the typical sense, and he was responsible for both the conversion of his student as well as the mental and spiritual well-being. The Da'i was a guide and light to the Imam. The teacher-student relationship of the Da'i and his student was much like the one that would develop in

Sufism

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality ...

. The student desired God, and the Da'i could bring him to God by making him recognize the Imam, who possesses the knowledge of the Oneness of God. The Da'i and Imam were respectively the spiritual mother and spiritual father of the Isma'ili believers.

Ja'far bin Mansur al-Yaman's ''

The Book of the Sage and Disciple

''The Book of the Sage and Disciple'' ( ar, كتاب العالم والغلام, Kitāb al-‘ālim wa-l-ghulām) is a religious narrative of spiritual initiation written in the form of a dramatic dialogue by Ja'far ibn Mansur al-Yaman (270 AH/ ...

'' is a classic of early

Fatimid

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Ismaili Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east. The Fatimids, a dyna ...

literature, documenting important aspects of the development of the Isma'ili da'wa in tenth-century Yemen. The book is also of considerable historical value for modern scholars of Arabic prose literature as well as those interested in the relationship of esoteric Shia with early Islamic mysticism. Likewise is the book an important source of information regarding the various movements within tenth-century Shīa leading to the spread of the Fatimid-Isma'ili da'wa throughout the medieval Islamicate world and the religious and philosophical history of post-Fatimid Musta'li branch of Isma'ilism in Yemen and India.

The Qarmatians

While many of the Isma'ili were content with the Da'i teachings, a group that mingled Persian nationalism and

Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism is an Iranian religion and one of the world's oldest organized faiths, based on the teachings of the Iranian-speaking prophet Zoroaster. It has a dualistic cosmology of good and evil within the framework of a monotheisti ...

surfaced known as the Qarmatians. With their headquarters in

Bahrain

Bahrain ( ; ; ar, البحرين, al-Bahrayn, locally ), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, ' is an island country in Western Asia. It is situated on the Persian Gulf, and comprises a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and a ...

, they accepted a young Persian former prisoner by the name of

Abu'l-Fadl al-Isfahani Abu'l-Fadl al-Isfahani, also known as the Isfahani Mahdi, was a young Persian man who in 931 CE was declared to be "God incarnate" by the Qarmatian leader of Bahrayn, Abu Tahir al-Jannabi. This new apocalyptic leader, however, caused great disrupt ...

, who claimed to be the descendant of the Persian kings

as their Mahdi, and rampaged across the Middle-East in the tenth century, climaxing their violent campaign by stealing the

Black Stone from the

Kaaba

The Kaaba (, ), also spelled Ka'bah or Kabah, sometimes referred to as al-Kaʿbah al-Musharrafah ( ar, ٱلْكَعْبَة ٱلْمُشَرَّفَة, lit=Honored Ka'bah, links=no, translit=al-Kaʿbah al-Musharrafah), is a building at the c ...

in

Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow v ...

in 930 under

Abu Tahir al-Jannabi

Abu Tahir Sulayman al-Jannabi ( ar, ابو طاهر سلیمان الجنّابي, Abū Tāhir Sulaymān al-Jannābī, fa, ابوطاهر سلیمانِ گناوهای ''Abu-Tāher Soleymān-e Genāve'i'') was a Persian warlord and the ruler ...

. Following the arrival of the Al-Isfahani, they changed their

qibla

The qibla ( ar, قِبْلَة, links=no, lit=direction, translit=qiblah) is the direction towards the Kaaba in the Sacred Mosque in Mecca, which is used by Muslims in various religious contexts, particularly the direction of prayer for the ...

from the

Kaaba

The Kaaba (, ), also spelled Ka'bah or Kabah, sometimes referred to as al-Kaʿbah al-Musharrafah ( ar, ٱلْكَعْبَة ٱلْمُشَرَّفَة, lit=Honored Ka'bah, links=no, translit=al-Kaʿbah al-Musharrafah), is a building at the c ...

in

Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow v ...

to the Zoroastrian-influenced fire. After their return of the Black Stone in 951 and a defeat by the Abbasids in 976 the group slowly dwindled off and no longer has any adherents.

The Fatimid Caliphate

Rise of the Fatimid Caliphate

The political asceticism practiced by the Imāms during the period after Muhammad ibn Ismail was to be short-lived and finally concluded with the Imāmate of Abdullah al-Mahdi Billah, who was born in 873. After decades of Ismāʿīlīs believing that Muhammad ibn Ismail was in the Occultation and would return to bring an age of justice, al-Mahdi taught that the Imāms had not been literally secluded, but rather had remained hidden to protect themselves and had been organizing the Da'i, and even acted as Da'i themselves.

After raising an army and successfully defeating the

Aghlabids

The Aghlabids ( ar, الأغالبة) were an Arab dynasty of emirs from the Najdi tribe of Banu Tamim, who ruled Ifriqiya and parts of Southern Italy, Sicily, and possibly Sardinia, nominally on behalf of the Abbasid Caliph, for about a ...

in North Africa and a number of other victories, al-Mahdi Billah successfully established a Shia political state ruled by the Imāmate in 910. This was the only time in history where the Shia Imamate and Caliphate were united after the first Imam, Ali ibn Abi Talib.

In parallel with the dynasty's claim of descent from ʻAlī and

Fāṭimah, the empire was named "Fatimid". However, this was not without controversy, and recognizing the extent that Ismāʿīlī doctrine had spread, the

Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttal ...

assigned

Sunni

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word '' Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a dis ...

and

Twelver

Twelver Shīʿīsm ( ar, ٱثْنَا عَشَرِيَّة; '), also known as Imāmīyyah ( ar, إِمَامِيَّة), is the largest branch of Shīʿa Islam, comprising about 85 percent of all Shīʿa Muslims. The term ''Twelver'' refers t ...

scholars the task to disprove the lineage of the new dynasty. This became known as the

Baghdad Manifesto

The Baghdad Manifesto was a polemical tract issued in 1011 on behalf of the Abbasid caliph al-Qadir against the rival Isma'ili Fatimid Caliphate.

Background

The manifesto was the result of the steady expansion of the Fatimid Caliphate since its es ...

, which tries to trace the lineage of the Fatimids to an alleged

Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

blacksmith

A blacksmith is a metalsmith who creates objects primarily from wrought iron or steel, but sometimes from other metals, by forging the metal, using tools to hammer, bend, and cut (cf. tinsmith). Blacksmiths produce objects such as gates, gr ...

.

The Middle East under Fatimid rule

The Fatimid Caliphate expanded quickly under the subsequent Imams. Under the Fatimids,

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

became the center of an

empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

that included at its peak

North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

,

Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

,

Palestine,

Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, the

Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

coast of Africa,

Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast and ...

,

Hejaz

The Hejaz (, also ; ar, ٱلْحِجَاز, al-Ḥijāz, lit=the Barrier, ) is a region in the west of Saudi Arabia. It includes the cities of Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, Tabuk, Yanbu, Taif, and Baljurashi. It is also known as the "Western Prov ...

and the

Tihamah

Tihamah or Tihama ( ar, تِهَامَةُ ') refers to the Red Sea coastal plain of the Arabian Peninsula from the Gulf of Aqaba to the Bab el Mandeb.

Etymology

Tihāmat is the Proto-Semitic language's term for 'sea'. Tiamat (or Tehom, in mas ...

. Under the Fatimids, Egypt flourished and developed an extensive trade network in both the

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

and the

Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by ...

, which eventually determined the economic course of Egypt during the

High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the periodization, period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended ...

.

The Fatimids promoted ideas that were radical for that time. One was a promotion by merit rather than genealogy.

Also during this period, the three contemporary branches of Isma'ilism formed. The first branch (

Druze

The Druze (; ar, دَرْزِيٌّ, ' or ', , ') are an Arabic-speaking esoteric ethnoreligious group from Western Asia who adhere to the Druze faith, an Abrahamic, monotheistic, syncretic, and ethnic religion based on the teachings of ...

) occurred with the

al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah

Abū ʿAlī Manṣūr (13 August 985 – 13 February 1021), better known by his regnal name al-Ḥākim bi-Amr Allāh ( ar, الحاكم بأمر الله, lit=The Ruler by the Order of God), was the sixth Fatimid caliph and 16th Ismaili i ...

. Born in 985, he ascended as ruler at the age of eleven. A religious group that began forming in his lifetime broke off from mainstream Ismailism and refused to acknowledge his successor. Later to be known as the Druze, they believe Al-Hakim to be the manifestation of God and the prophesied Mahdi, who would one day return and bring justice to the world. The faith further split from Ismailism as it developed unique doctrines which often class it separately from both Ismailism and Islam.

Arwa al-Sulayhi was the Hujjah in Yemen from the time of Imam al Mustansir. She appointed Da'i in Yemen to run religious affairs. Ismaili missionaries Ahmed and

Abadullah (in about 1067 CE (460 AH)) were also sent to India in that time. They sent

Syedi Nuruddin to Dongaon to look after southern part and

Syedi Fakhruddin to East

Rajasthan

Rajasthan (; lit. 'Land of Kings') is a state in northern India. It covers or 10.4 per cent of India's total geographical area. It is the largest Indian state by area and the seventh largest by population. It is on India's northwestern ...

, India.

The second split occurred following the death of

al-Mustansir Billah

Abū Tamīm Maʿad al-Mustanṣir biʾllāh ( ar, أبو تميم معد المستنصر بالله; 2 July 1029 – 29 December 1094) was the eighth Fatimid Caliph from 1036 until 1094. He was one of the longest reigning Muslim rulers. ...

in 1094 CE. His rule was the longest of any caliph in both the Fatimid and other Islamic empires. After he died, his sons

Nizar, the older, and

al-Musta'li

Abu al-Qasim Ahmad ibn al-Mustansir ( ar, أبو القاسم أحمد بن المستنصر, Abū al-Qāsim Aḥmad ibn al-Mustanṣir; 15/16 September 1074 – 12 December 1101), better known by his regnal name al-Musta'li Billah ( ar, ال� ...

, the younger, fought for political and spiritual control of the dynasty. Nizar was defeated and jailed, but according to

Nizari

The Nizaris ( ar, النزاريون, al-Nizāriyyūn, fa, نزاریان, Nezāriyān) are the largest segment of the Ismaili Muslims, who are the second-largest branch of Shia Islam after the Twelvers. Nizari teachings emphasize independent ...

sources his son escaped to

Alamut

Alamut ( fa, الموت) is a region in Iran including western and eastern parts in the western edge of the Alborz (Elburz) range, between the dry and barren plain of Qazvin in the south and the densely forested slopes of the Mazandaran provinc ...

, where the

Iranian

Iranian may refer to:

* Iran, a sovereign state

* Iranian peoples, the speakers of the Iranian languages. The term Iranic peoples is also used for this term to distinguish the pan ethnic term from Iranian, used for the people of Iran

* Iranian lan ...

Isma'ilis had accepted his claim.

The Musta'li line split again between the

Taiyabi

Tayyibi Isma'ilism is the only surviving sect of the Musta'li branch of Isma'ilism, the other being the extinct Hafizi branch. Followers of Tayyibi Isma'ilism are found in various Bohra communities: Dawoodi, Sulaymani, and Alavi.

The Tayyibi ...

and the

Hafizi, the former claiming that the 21st Imam and son of

al-Amir bi-Ahkami'l-Lah

Abu Ali al-Mansur ibn al-Musta'li ( ar, أبو علي المنصور بن المستعلي, Abū ʿAlī al-Manṣūr ibn al-Mustaʿlī; 31 December 1096 – 7 October 1130), better known by his regnal name al-Amir bi-Ahkam Allah ( ar, الآمر ...

went into occultation and appointed a Da'i al-Mutlaq to guide the community, in a similar manner as the Isma'ili had lived after the death of Muhammad ibn Isma'il. The latter claimed that the ruling Fatimid caliph was the Imām.

However, in the Mustaali branch, Dai came to have a similar but more important task. The term ''Da'i al-Mutlaq'' ( ar, الداعي المطلق, al-dāʿī al-muṭlaq) literally means "the absolute or unrestricted

missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Tho ...

". This da'i was the only source of the Imam's knowledge after the occultation of al-Qasim in Musta'li thought.

According to

Taiyabi Ismaili tradition, after the death of Imam al-Amir, his infant son,

at-Tayyib Abu'l-Qasim, about 2 years old, was protected by the most important woman in Musta'li history after Muhammad's daughter, Fatimah. She was

Arwa al-Sulayhi, a queen in Yemen. She was promoted to the post of hujjah long before by Imām Mustansir at the death of her husband. She ran the da'wat from Yemen in the name of Imaam Tayyib. She was instructed and prepared by Imam Mustansir and ran the dawat from Yemen in the name of Imaam Tayyib, following Imams for the second period of Satr. It was going to be on her hands, that Imam Tayyib would go into seclusion, and she would institute the office of the Da'i al-Mutlaq.

Zoeb bin Moosa was first to be instituted to this office. The office of da'i continued in Yemen up to 24th da'i

Yusuf who shifted da'wat to India. . Before the shift of da'wat in India, the da'i's representative were known as Wali-ul-Hind.

Syedi Hasan Feer was one of the prominent Isma'ili wali of 14th century. The line of Tayyib Da'is that began in 1132 is still continuing under the main sect known as

Dawoodi Bohra (see

list of Dai of Dawoodi Bohra

Short history The Dua't al-Mutlaqin

Al-Malika al-Sayyida (Hurratul-Malika) was instructed and prepared by Imām Mustansir and following Imāms for the second period of ''satr''. It was going to be on her hands that Imām Taiyab abi al-Qasi ...

).

The Musta'li split several times over disputes regarding who was the rightful Da'i al-Mutlaq, the leader of the community within

The Occultation

Occultation ( ar, غَيْبَة, ') in Shia Islam refers to the eschatological belief that Mahdi, a descendant of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, has already been born and subsequently concealed, but will reemerge to establish justice and peace ...

.

After the 27th Da'i, Syedna Dawood bin Qutub Shah, there was another split; the ones following Syedna Dawood came to be called Dawoodi Bohra, and followers of Suleman were then called Sulaimani. Dawoodi Bohra's present Da'i al Mutlaq, the 53rd, is Syedna Mufaddal Saifuddin, and he and his devout followers tread the same path, following the same tradition of the Aimmat Fatimiyyeen. The

Sulaymani

The Sulaymani branch of Tayyibi Isma'ilism is an Islamic community, of which around 70,000 members reside in Yemen, while a few thousand Sulaymani Bohras can be found in India. The Sulaymanis are sometimes headed by a ''Da'i al-Mutlaq'' from ...

are mostly concentrated in Yemen and Saudi Arabia with some communities in the

South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The region consists of the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.;;;;; ...

. The

Dawoodi Bohra and

Alavi Bohra are mostly exclusive to South Asia, after the migration of the da'wah from Yemen to India. Other groups include

Atba-i-Malak

The Atba-e-Malak community are a branch of Musta'ali Isma'ili Shi'a Islam that broke off from the mainstream Dawoodi Bohra after the death of the 46th Da'i al-Mutlaq, under the leadership of Moulana Abdul Hussain Jivaji Saheb in 1890. They are bas ...

and

Hebtiahs Bohra

The Hebtiahs Bohra are a branch of Mustaali Ismaili Shi'a Islam that broke off from the mainstream Dawoodi Bohra after the death of the 39th Da'i al-Mutlaq in 1754. They are mostly concentrated in Ujjain in India with a few families who are Heb ...

. Mustaali beliefs and practices, unlike those of the Nizari and Druze, are regarded as compatible with mainstream Islam, representing a continuation of Fatimid tradition and

fiqh

''Fiqh'' (; ar, فقه ) is Islamic jurisprudence. Muhammad-> Companions-> Followers-> Fiqh.

The commands and prohibitions chosen by God were revealed through the agency of the Prophet in both the Quran and the Sunnah (words, deeds, and e ...

.

Decline of the Caliphate

In the 1040s, the

Zirid dynasty

The Zirid dynasty ( ar, الزيريون, translit=az-zīriyyūn), Banu Ziri ( ar, بنو زيري, translit=banū zīrī), or the Zirid state ( ar, الدولة الزيرية, translit=ad-dawla az-zīriyya) was a Sanhaja Berber dynasty from m ...

(governors of the

Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ar, الْمَغْرِب, al-Maghrib, lit=the west), also known as the Arab Maghreb ( ar, المغرب العربي) and Northwest Africa, is the western part of North Africa and the Arab world. The region includes Algeria, ...

under the Fatimids) declared their independence and their conversion to

Sunni Islam

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word '' Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disag ...

, which led to the devastating

Banu Hilal

The Banu Hilal ( ar, بنو هلال, translit=Banū Hilāl) was a confederation of Arabian tribes from the Hejaz and Najd regions of the Arabian Peninsula that emigrated to North Africa in the 11th century. Masters of the vast plateaux of t ...

invasions. After about 1070, the Fatimid hold on the

Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

coast and parts of Syria was challenged by first

Turkish invasions, then the

First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Islamic ...

, so that Fatimid territory shrunk until it consisted only of Egypt. Damascus fell to the

Seljuk Empire

The Great Seljuk Empire, or the Seljuk Empire was a high medieval, culturally Turko-Persian, Sunni Muslim empire, founded and ruled by the Qïnïq branch of Oghuz Turks. It spanned a total area of from Anatolia and the Levant in the west to ...

in 1076, leaving the Fatimids only in charge of Egypt and the Levantine coast up to

Tyre and

Sidon

Sidon ( ; he, צִידוֹן, ''Ṣīḏōn'') known locally as Sayda or Saida ( ar, صيدا ''Ṣaydā''), is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate, of which it is the capital, on the Mediterranean coast. ...

. Because of the vehement opposition to the Fatimids from the Seljuks, the Ismaili movement was only able to operate as a terrorist underground movement, much like the

Assassins

An assassin is a person who commits targeted murder.

Assassin may also refer to:

Origin of term

* Someone belonging to the medieval Persian Ismaili order of Assassins

Animals and insects

* Assassin bugs, a genus in the family ''Reduviid ...

.

After the decay of the Fatimid political system in the 1160s, the

Zengid ruler

Nur ad-Din, atabeg of Aleppo had his general,

Saladin

Yusuf ibn Ayyub ibn Shadi () ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known by the epithet Saladin,, ; ku, سهلاحهدین, ; was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from an ethnic Kurdish family, he was the first of both Egypt an ...

, seize Egypt in 1169, forming the Sunni

Ayyubid dynasty

The Ayyubid dynasty ( ar, الأيوبيون '; ) was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt. A Sunni Muslim of Kurdish origin, Saladin ...

. This signaled the end of the Hafizi Mustaali branch of Ismailism as well as the Fatimid Caliphate.

Alamut

Hassan-i Sabbah

Very early in the empire's life, the Fatimids sought to spread the Isma'ili faith, which in turn would spread loyalty to the Imamate in Egypt. One of their earliest attempts was taken by a missionary by the name of

Hassan-i Sabbah

Hasan-i Sabbāh ( fa, حسن صباح) or Hassan as-Sabbāh ( ar, حسن بن الصباح الحميري, full name: Hassan bin Ali bin Muhammad bin Ja'far bin al-Husayn bin Muhammad bin al-Sabbah al-Himyari; c. 1050 – 12 June 1124) was the ...

.

Hassan-i Sabbah was born into a

Twelver

Twelver Shīʿīsm ( ar, ٱثْنَا عَشَرِيَّة; '), also known as Imāmīyyah ( ar, إِمَامِيَّة), is the largest branch of Shīʿa Islam, comprising about 85 percent of all Shīʿa Muslims. The term ''Twelver'' refers t ...

family living in the scholarly Persian city of

Qom

Qom (also spelled as "Ghom", "Ghum", or "Qum") ( fa, قم ) is the seventh largest metropolis and also the seventh largest city in Iran. Qom is the capital of Qom Province. It is located to the south of Tehran. At the 2016 census, its pop ...

in 1056 CE. His family later relocated to the city of Tehran, which was an area with an extremely active Isma'ili Da'wah. He immersed himself in Ismāʿīlī thought; however, he did not choose to convert until he was overcome with an almost fatal illness and feared dying without knowing the Imām of his time.

Afterward, Hassan-i Sabbah became one of the most influential Da'is in Isma'ili history; he became important to the survival of the Nizari branch of Ismailism, which today is its largest branch.

Legend holds that he met with Imam

al-Mustansir Billah

Abū Tamīm Maʿad al-Mustanṣir biʾllāh ( ar, أبو تميم معد المستنصر بالله; 2 July 1029 – 29 December 1094) was the eighth Fatimid Caliph from 1036 until 1094. He was one of the longest reigning Muslim rulers. ...

and asked him who his successor would be, to which he responded that it would be his eldest son

Nizar (Fatimid Imam).

Hassan-i Sabbah continued his missionary activities, which climaxed with his taking of the famous

citadel of Alamut. Over the next two years, he converted most of the surrounding villages to Isma'ilism. Afterward, he converted most of the staff to Ismailism, took over the fortress, and presented Alamut's king with payment for his fortress, which he had no choice but to accept. The king reluctantly abdicated his throne, and Hassan-i Sabbah turned

Alamut

Alamut ( fa, الموت) is a region in Iran including western and eastern parts in the western edge of the Alborz (Elburz) range, between the dry and barren plain of Qazvin in the south and the densely forested slopes of the Mazandaran provinc ...

into an outpost of Fatimid rule within Abbasid territory.

The Hashasheen / Assassiyoon

Surrounded by the Abbasids and other hostile powers and low in numbers, Hassan-i Sabbah devised a way to attack the Isma'ili enemies with minimal losses. Using the method of assassination, he ordered the murders of Sunni scholars and politicians who he felt threatened the Isma'ilis. Knives and daggers were used to kill, and sometimes as a warning, a knife would be placed on the pillow of a Sunni, who understood the message to mean that he was marked for death.

When an assassination was actually carried out, the Hashasheen would not be allowed to run away; instead, to strike further fear into the enemy, they would stand near the victim without showing any emotion and departed only when the body was discovered. This further increased the ruthless reputation of the Hashasheen throughout Sunni-controlled lands.

The English word ''assassins'' is said to have been derived from the Arabic word ''Hasaseen'' meaning annihilators as mentioned in Quran 3:152 or

Hashasheen

The Order of Assassins or simply the Assassins ( fa, حَشّاشین, Ḥaššāšīn, ) were a Nizārī Ismāʿīlī order and sect of Shīʿa Islam that existed between 1090 and 1275 CE. During that time, they lived in the mountains of P ...

meaning both "those who use hashish" and "throat slitters" in

Egyptian Arabic

Egyptian Arabic, locally known as Colloquial Egyptian ( ar, العامية المصرية, ), or simply Masri (also Masry) (), is the most widely spoken vernacular Arabic dialect in Egypt. It is part of the Afro-Asiatic language family, and ...

dialect, and one of the Shia Ismaili sects in the Syria of the eleventh century.

Threshold of the Imāmate

After the imprisonment of Nizar by his younger brother Ahmad al Mustaali, various sources indicate that Nizar's son Ali Al-Hadi ibn Nizari survived and fled to Alamut. He was offered a safe place in Alamut, where Hassan-Al-Sabbah welcomed him. However, it is believed this was not announced to the public and the lineage was hidden until a few Imāms later to avoid further attacks hostility.

It was announced with the advent of Imam Hassan II. In a show of his Imamate and to emphasize the interior meaning (the

batin) over the exterior meaning (the

zahir), only two years after his accession, the Imām Hasan 'Ala Zikrihi al-Salam conducted a ceremony known as ''qiyama'' (resurrection) at the grounds of the

Alamut Castle

Alamut ( fa, الموت, meaning "eagle's nest") is a ruined mountain fortress located in the Alamut region in the South Caspian province of Qazvin near the Masoudabad region in Iran, approximately 200 km (130 mi) from present-day Teh ...

, whereby the Imam would once again become visible to his community of followers in and outside of the

Nizārī Ismā'īlī state. Given

Juwayni's polemical aims, and the fact that he burned the Isma'ili libraries which may have offered much more reliable testimony about the history, scholars have been dubious about his narrative but are forced to rely on it given the absence of alternative sources. Fortunately, descriptions of this event are also preserved in

Rashid al-Din’s narrative and recounted in the Haft Bab Baba-yi Sayyidna, written 60 years after the event, and the later Haft Bab-i Abi Ishaq, an Ismaili book of the 15th century AD. However, Rashid al-Din's narrative is based on

Juwayni,

and the Nizari sources do not go into specific details. Since very few contemporary Nizari Ismaili accounts of the events have survived, and it is likely that scholars will never know the exact details of this event. However, there was no total abrogation of all law - only certain exoteric rituals like the Salah/Namaz, Fasting in Ramadan, Hajj to Makkah, and facing Makkah in prayer were abrogated; however, the Nizaris continued to perform rituals of worship, except these rituals were more esoteric and spiritually oriented. For example, the true prayer is to remember God at every moment; true fasting is to keep all of the body's organs away from whatever is unethical and forbidden. Ethical conduct is enjoined at all times.

Afterward, his descendants ruled as the Imams at Alamut until its destruction by the Mongols.

Destruction by the Mongols

Though it had successfully warded off Sunni attempts to take it several times, including one by

Saladin

Yusuf ibn Ayyub ibn Shadi () ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known by the epithet Saladin,, ; ku, سهلاحهدین, ; was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from an ethnic Kurdish family, he was the first of both Egypt an ...

, the stronghold at Alamut soon met its destruction. By 1206,

Genghis Khan

Genghis Khan (born Temüjin; ; xng, Temüjin, script=Latn; ., name=Temujin – August 25, 1227) was the founder and first Great Khan (Emperor) of the Mongol Empire, which became the List of largest empires, largest contiguous empire in history a ...

had managed to unite many of the once antagonistic Mongol tribes into a ruthless, but nonetheless unified, force. Using many new and unique military techniques, Genghis Khan led his Mongol hordes across Central Asia into the

Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

, where they won a series of tactical military victories using a

scorched earth

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy that aims to destroy anything that might be useful to the enemy. Any assets that could be used by the enemy may be targeted, which usually includes obvious weapons, transport vehicles, commun ...

policy.

A grandson of Genghis Khan,

Hulagu Khan

Hulagu Khan, also known as Hülegü or Hulegu ( mn, Хүлэгү/ , lit=Surplus, translit=Hu’legu’/Qülegü; chg, ; Arabic: fa, هولاکو خان, ''Holâku Khân;'' ; 8 February 1265), was a Mongol ruler who conquered much of We ...

, led the devastating attack on Alamut in 1256, only a short time before sacking the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad in 1258. As he would later do to the

House of Wisdom

The House of Wisdom ( ar, بيت الحكمة, Bayt al-Ḥikmah), also known as the Grand Library of Baghdad, refers to either a major Abbasid public academy and intellectual center in Baghdad or to a large private library belonging to the Abba ...

in Baghdad, he destroyed Isma'ili as well as Islamic religious texts. The Imamate that was located in Alamut along with its few followers were forced to flee and take refuge elsewhere.

Aftermath

After the fall of the Fatimid Caliphate and its bases in Iran and Syria, the three currently living branches of Isma'ili generally developed geographically isolated from each other, with the exception of

Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

(which has both Druze and Nizari) and

Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

and the rest of South Asia (which had both Mustaali and Nizari).

The

Musta'li

The Musta‘lī ( ar, مستعلي) are a branch of Isma'ilism named for their acceptance of al-Musta'li as the legitimate nineteenth Fatimid caliph and legitimate successor to his father, al-Mustansir Billah. In contrast, the Nizari—the other ...

progressed mainly under the Isma'ili-adhering Yemeni ruling class well into the 12th century, until the fall of the last

Sulayhid dynasty,

Hamdanids (Yemen) and

Zurayids rump state

A rump state is the remnant of a once much larger state, left with a reduced territory in the wake of secession, annexation, occupation, decolonization, or a successful coup d'état or revolution on part of its former territory. In the last case ...

in 1197 AD, then they shifted their da'wat to India under the Da'i al-Mutlaq, working on behalf of their last Imam, Taiyyab, and are known as Bohra. From India, various groups spread mainly to south Asia and eventually to the Middle East, Europe, Africa, and America.

The

Nizari

The Nizaris ( ar, النزاريون, al-Nizāriyyūn, fa, نزاریان, Nezāriyān) are the largest segment of the Ismaili Muslims, who are the second-largest branch of Shia Islam after the Twelvers. Nizari teachings emphasize independent ...

have maintained large populations in

Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

,

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan (, ; uz, Ozbekiston, italic=yes / , ; russian: Узбекистан), officially the Republic of Uzbekistan ( uz, Ozbekiston Respublikasi, italic=yes / ; russian: Республика Узбекистан), is a doubly landlocked co ...

,

Tajikistan

Tajikistan (, ; tg, Тоҷикистон, Tojikiston; russian: Таджикистан, Tadzhikistan), officially the Republic of Tajikistan ( tg, Ҷумҳурии Тоҷикистон, Jumhurii Tojikiston), is a landlocked country in Centr ...

,

Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is borde ...

,

Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

,

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

, and they have smaller populations in

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

and

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

. This community is the only one with a living Imam, whose title is the

Aga Khan

Aga Khan ( fa, آقاخان, ar, آغا خان; also transliterated as ''Aqa Khan'' and ''Agha Khan'') is a title held by the Imām of the Nizari Ismāʿīli Shias. Since 1957, the holder of the title has been the 49th Imām, Prince Shah Kari ...

.

Badakhshan

Badakhshan is a historical region comprising parts of modern-day north-eastern Afghanistan, eastern Tajikistan, and Taxkorgan Tajik Autonomous County in China. Badakhshan Province is one of the 34 provinces of Afghanistan. Much of historic ...

, which includes parts of northeastern

Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is borde ...

and southeastern

Tajikistan

Tajikistan (, ; tg, Тоҷикистон, Tojikiston; russian: Таджикистан, Tadzhikistan), officially the Republic of Tajikistan ( tg, Ҷумҳурии Тоҷикистон, Jumhurii Tojikiston), is a landlocked country in Centr ...

, is the only part of the world where Ismailis make up the majority of the population.

The

Druze

The Druze (; ar, دَرْزِيٌّ, ' or ', , ') are an Arabic-speaking esoteric ethnoreligious group from Western Asia who adhere to the Druze faith, an Abrahamic, monotheistic, syncretic, and ethnic religion based on the teachings of ...

mainly settled in Syria and

Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus lie ...

and developed a community based upon the principles of

reincarnation

Reincarnation, also known as rebirth or transmigration, is the philosophical or religious concept that the non-physical essence of a living being begins a new life in a different physical form or body after biological death. Resurrectio ...

through their own descendants. Their leadership is based on community scholars, who are the only individuals allowed to read their holy texts. There is controversy over whether this group falls under the classification of Isma'ilism or Islam because of its unique beliefs.

The

Tajiks of Xinjiang

The Tajiks of Xinjiang ( Sarikoli: , , ), also known as Chinese Tajiks () or Mountain Tajiks, are Pamiris that live in the Pamir mountains of Taxkorgan Tajik Autonomous County, in Xinjiang, China. They are one of the 56 ethnic groups officia ...

, being Isma'ili, were not subjected to being

enslaved in China by Sunni Muslim Turkic peoples because the two peoples did not share a common geographical region. The

Burusho people

The Burusho, or Brusho, also known as the Botraj, are an ethnolinguistic group indigenous to the Yasin, Hunza, Nagar, and other valleys of Gilgit–Baltistan in northern Pakistan, as well as in Jammu and Kashmir, India. Their language, Buru ...

of

Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

are also Nizaris. However, due to their isolation from the rest of the world, Islam reached the Hunza about 350 years ago. Ismailism has been practiced by the Hunza for the last 300 years. The Hunza have been ruled by the same family of kings for over 900 years. They were called Kanjuts. Sunni Islam never took root in this part of central Asia so even now, there are less than a few dozen Sunnis living among the Hunza.

Ismaili historiography

One of the most important texts in Ismaili historiography is the ''ʿUyun al-Akhbar'', which is a reference source on the history of Ismailism that was composed in 7 books by the Tayyibi Mustaʻlian Ismaili ''daʻi''-scholar,

Idris Imad al-Din

Idris Imad al-Din ( ar, إدريس عماد الدين بن الحسن القرشي, Idrīs ʿImād al-Dīn ibn al-Ḥasan al-Qurashī; 1392 – 10 June 1468) was the 19th Tayyibi Isma'ili '' Dāʿī al-Muṭlaq'' and a major religious and politic ...

(born ca. 1392). This text presents the most comprehensive history of the Ismaili Imams and ''daʻwa'', from the earliest period of Muslim history until the late Fatimid era. The author, Idris Imad al-Din, descended from the prominent al-Walid family of the Quraysh in Yemen, who led the Tayyibi Mustaʻlian Ismaili ''daʻwa'' for more than three centuries. This gave him access to the literary heritage of the Ismailis, including the majority of the extant Fatimid manuscripts transferred to Yemen. The ''ʻUyun al-Akhbar'' is being published in 7 volumes of annotated Arabic critical editions as part of an institutional collaboration between the Institut Français du Proche Orient (IFPO) in Damascus and The Institute of Ismaili Studies (IIS) in London. This voluminous text has been critically edited based on several old manuscripts from The Institute of Ismaili Studies' vast collection. These academic editions have been prepared by a team of Syrian and Egyptian scholars, including Dr Ayman F Sayyid, and this major publication project has been coordinated by Dr

Nader El-Bizri

Nader El-Bizri ( ar, نادر البزري, ''nādir al-bizrĩ'') is the Dean of the College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences at the University of Sharjah. He served before as a tenured longstanding full Professor of philosophy and ci ...

(IIS) and Dr Sarab Atassi-Khattab (IFPO).

Beliefs

View on the Quran

In the Isma'ili belief, God’s Speech (''kalam Allah'') is the everlasting creative command that perpetuates all things and simultaneously embodies the essences of every existent being. This eternal commandment “flows” or “emanates” to Prophets (

Prophets and messengers in Islam

Prophets in Islam ( ar, الأنبياء في الإسلام, translit=al-ʾAnbiyāʾ fī al-ʾIslām) are individuals in Islam who are believed to spread God's message on Earth and to serve as models of ideal human behaviour. Some prophets a ...

) through a spiritual hierarchy that consists of the Universal Intellect, Universal Soul, and the angelic intermediaries of ''Jadd'', ''Fath'', and ''Khayal'' who are identified with the archangels

Seraphiel

Seraphiel (Hebrew , meaning "Prince of the High Angelic Order") is the name of an angel in the apocryphal Book of Enoch.

Protector of Metatron, Seraphiel holds the highest rank of the Seraphim with the following directly below him, Jehoel. In s ...

,

Michael (archangel)

Michael (; he, מִיכָאֵל, lit=Who is like El od, translit=Mīḵāʾēl; el, Μιχαήλ, translit=Mikhaḗl; la, Michahel; ar, ميخائيل ، مِيكَالَ ، ميكائيل, translit=Mīkāʾīl, Mīkāl, Mīkhāʾīl), also ...

, and

Gabriel

In Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity and Islam), Gabriel (); Greek: grc, Γαβριήλ, translit=Gabriḗl, label=none; Latin: ''Gabriel''; Coptic: cop, Ⲅⲁⲃⲣⲓⲏⲗ, translit=Gabriêl, label=none; Amharic: am, ገብ� ...

(''Jibra'il'' in Arabic), respectively. As a result, the Prophets receive revelations as divine, spiritual, and nonverbal “inspiration” (''wahy'') and “support” (''taʾyīd''), through the means of the Holy Spirit,

Gabriel

In Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity and Islam), Gabriel (); Greek: grc, Γαβριήλ, translit=Gabriḗl, label=none; Latin: ''Gabriel''; Coptic: cop, Ⲅⲁⲃⲣⲓⲏⲗ, translit=Gabriêl, label=none; Amharic: am, ገብ� ...

, which is a heavenly power that illuminates the souls of the Prophets, just as the radiance of light reflects in a mirror. Accordingly, God illuminated

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mon ...

with a divine light (

Nūr (Islam)) that constituted the divine nonverbal revelation (through the medium of archangel

Gabriel

In Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity and Islam), Gabriel (); Greek: grc, Γαβριήλ, translit=Gabriḗl, label=none; Latin: ''Gabriel''; Coptic: cop, Ⲅⲁⲃⲣⲓⲏⲗ, translit=Gabriêl, label=none; Amharic: am, ገብ� ...

), and Muhammad, then, expressed the divine truths contained within this transmission in the Arabic terms that constitute the

Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , ...

. Consequently, the Isma'ilis believe that the Arabic Qur’an is God’s Speech in a secondary and subordinate sense, as it only verbally expresses the “signs” (''āyāt'') of God’s actual cosmic commandments.

According to the 14th Isma'ili Imam and fourth Fatimid Caliph

Al-Mu'izz li-Din Allah

Abu Tamim Ma'ad al-Muizz li-Din Allah ( ar, ابو تميم معد المعزّ لدين الله, Abū Tamīm Maʿad al-Muʿizz li-Dīn Allāh, Glorifier of the Religion of God; 26 September 932 – 19 December 975) was the fourth Fatimid calip ...

, “

he Prophetonly conveyed the meanings of the inspiration

'wahy''and the light – its obligations, rulings and allusions – by means of utterances composed with arranged, combined, intelligible, and audible letters”. Hence, according to the Imam, the

Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , ...

is God’s Speech only in its inward spiritual essence, while its outward verbal form is the words of Prophet

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mon ...

.

The Isma'ili view on God’s Speech is therefore in contrast with the

Hanbali

The Hanbali school ( ar, ٱلْمَذْهَب ٱلْحَنۢبَلِي, al-maḏhab al-ḥanbalī) is one of the four major traditional Sunni schools ('' madhahib'') of Islamic jurisprudence. It is named after the Arab scholar Ahmad ibn Hanba ...