Islamic philosophers on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Muslim philosophers both profess

, Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy The tenth century philosopher

/ref> , - , , Spain

(Andalusia)

, 1126–1198

, Peripatetic

, Being described as "founding father of secular thought in Western Europe", He was known by the nickname ''the Commentator'' for his precious commentaries on Aristotle's works. His main work was ''

, Spain

(Andalusia)

, 1126–1198

, Peripatetic

, Being described as "founding father of secular thought in Western Europe", He was known by the nickname ''the Commentator'' for his precious commentaries on Aristotle's works. His main work was '' , Spain

(Andalusia)

, 1165–1240

, Sufi

, He was an

, Spain

(Andalusia)

, 1165–1240

, Sufi

, He was an  , Damascus

(Syria)

, 1213–1288

,

, His ''Al-Risalah al-Kamiliyyah fil Siera al-Nabawiyyah'' or''

, Damascus

(Syria)

, 1213–1288

,

, His ''Al-Risalah al-Kamiliyyah fil Siera al-Nabawiyyah'' or''

''Encyclopedia of Islamic World'

He described this book as a defense of "the system of Islam and the Muslims' doctrines on the missions of prophets, the religious laws, the resurrection of the body, and the transitoriness of the world". , - , Qotb al-Din Shirazi , , Persia (Iran)

, 1217–1311

,

, He was a

, Persia (Iran)

, 1217–1311

,

, He was a  , Persia (Iran)

, 1414–1492

, Sufi

, His Haft Awrang (Seven Thrones) includes seven stories, among which ''Salaman and Absal'' tells the story of a sensual attraction of a prince for his wet-nurse, through which Jami uses figurative symbols to depict the key stages of the

, Persia (Iran)

, 1414–1492

, Sufi

, His Haft Awrang (Seven Thrones) includes seven stories, among which ''Salaman and Absal'' tells the story of a sensual attraction of a prince for his wet-nurse, through which Jami uses figurative symbols to depict the key stages of the  , Persia

, 1547–1621

,

, Regarded as a leading scholar and mujaddid of the seventeenth century,

, Persia

, 1547–1621

,

, Regarded as a leading scholar and mujaddid of the seventeenth century,

BAHĀʾ-AL-DĪN ʿĀMELĪ, SHAIKH MOḤAMMAD B. ḤOSAYN BAHĀʾĪ

' by E. Kohlberg. he worked on , (British India)

Pakistan

, 1877–1938

, Modernist/

Sufi

, Other than being an eminent poet, he is recognized as the "Muslim philosophical thinker of modern times". He wrote two books on the topic of ''

, (British India)

Pakistan

, 1877–1938

, Modernist/

Sufi

, Other than being an eminent poet, he is recognized as the "Muslim philosophical thinker of modern times". He wrote two books on the topic of '' , Persia (Iran)

, 1892–1981

, Shia

, He is famous for ''

, Persia (Iran)

, 1892–1981

, Shia

, He is famous for ''

an article by Encyclopedia of Religion In his History of Islamic Philosophy, he refuted the view that philosophy among the Muslims came to an end after Averroes, showed rather that a vivid philosophical activity persisted in the eastern Muslim world – especially Iran. , - , Abdel Rahman Badawi , , Egypt , 1917–2002 , , He adopted existentialism since he wrote his ''Existentialist Time'' in 1943. His version of existentialism, according to his own description, differs from Heidegger's and other existentialists in that it gives preference to action rather than thought. in his later work,''Humanism And Existentialism In Arab Thought'', however, he tried to root his ideas in his own culture. , - , , Persia (Iran)

, 1919–1979

, Shia

, Considered among the important influences on the ideologies of the

, Persia (Iran)

, 1919–1979

, Shia

, Considered among the important influences on the ideologies of the  , Persia (Iran)

, 1923–1998

, Shia

, He wrote many books on variety of fields, the most prominent of which are his 15-volume Interpretation and Criticism of

, Persia (Iran)

, 1923–1998

, Shia

, He wrote many books on variety of fields, the most prominent of which are his 15-volume Interpretation and Criticism of  , Persia (Iran)

, 1933–1977

, Modernist/

Shia

, Ali Shariati Mazinani (Persian: علی شریعتی مزینانی, 23 November 1933 – 18 June 1977) was an Iranian revolutionary and sociologist who focused on the sociology of religion. He is held as one of the most influential Iranian intellectuals of the 20th century and has been called the "ideologue of the Iranian Revolution", although his ideas ended up not forming the basis of the Islamic Republic

, -

,

, Persia (Iran)

, 1933–1977

, Modernist/

Shia

, Ali Shariati Mazinani (Persian: علی شریعتی مزینانی, 23 November 1933 – 18 June 1977) was an Iranian revolutionary and sociologist who focused on the sociology of religion. He is held as one of the most influential Iranian intellectuals of the 20th century and has been called the "ideologue of the Iranian Revolution", although his ideas ended up not forming the basis of the Islamic Republic

, -

,  , Persia (Iran)

, 1933–

, Sufi/Shia

, He is a major perennialist thinker. His works defend Islamic and perennialist doctrines and principles while challenging the theoretical underpinnings of modern science. He argues that knowledge has been desacralized in the modern period, that is, separated from its divine source—God—and calls for its resacralization through sacred traditions and sacred science. His

, Persia (Iran)

, 1933–

, Sufi/Shia

, He is a major perennialist thinker. His works defend Islamic and perennialist doctrines and principles while challenging the theoretical underpinnings of modern science. He argues that knowledge has been desacralized in the modern period, that is, separated from its divine source—God—and calls for its resacralization through sacred traditions and sacred science. His  , Turkey

, 1934–2016

,

, He was working on

, Turkey

, 1934–2016

,

, He was working on  , Persia (Iran)

, 1945–

, Shia/

Neoplatonist

, Being interested in the philosophy of religion and the philosophical system of

, Persia (Iran)

, 1945–

, Shia/

Neoplatonist

, Being interested in the philosophy of religion and the philosophical system of  , Pakistan

, 1951-

, Modernist

, Javed Ahmed Ghamidi is a Pakistani theologian. He is regarded as one of the contemporary modernists of Islamic world. Like ''Parwez'' he also promotes rationalism and secular thought with deen. Ghamidi is also popular for his moderate

, Pakistan

, 1951-

, Modernist

, Javed Ahmed Ghamidi is a Pakistani theologian. He is regarded as one of the contemporary modernists of Islamic world. Like ''Parwez'' he also promotes rationalism and secular thought with deen. Ghamidi is also popular for his moderate  , Switzerland/

France

, 1962–

, Modernist

, Working mainly on Islamic theology and the place of Muslims in the West, he believes that western Muslims must think up a "Western Islam" in accordance to their own social circumstances.

, Switzerland/

France

, 1962–

, Modernist

, Working mainly on Islamic theology and the place of Muslims in the West, he believes that western Muslims must think up a "Western Islam" in accordance to their own social circumstances.

Islamic Philosophy Online

Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

and engage in a style of philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. ...

situated within the structure of the Arabic language and Islam, though not necessarily concerned with religious issues. The sayings of the companions of Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mon ...

contained little philosophical discussion. In the eighth century, extensive contact with the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

led to a drive to translate philosophical works of Ancient Greek Philosophy

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC, marking the end of the Greek Dark Ages. Greek philosophy continued throughout the Hellenistic period and the period in which Greece and most Greek-inhabited lands were part of the Roman Empire ...

(especially the texts of Aristotle) into Arabic.

The ninth-century Al-Kindi

Abū Yūsuf Yaʻqūb ibn ʼIsḥāq aṣ-Ṣabbāḥ al-Kindī (; ar, أبو يوسف يعقوب بن إسحاق الصبّاح الكندي; la, Alkindus; c. 801–873 AD) was an Arab Muslim philosopher, polymath, mathematician, physician ...

is considered the founder of Islamic peripatetic philosophy (800–1200).Islamic philosophy, Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy The tenth century philosopher

al-Farabi

Abu Nasr Muhammad Al-Farabi ( fa, ابونصر محمد فارابی), ( ar, أبو نصر محمد الفارابي), known in the West as Alpharabius; (c. 872 – between 14 December, 950 and 12 January, 951)PDF version was a renowned early Isl ...

contributed significantly to the introduction of Greek and Roman philosophical works into Muslim philosophical discourse and established many of the themes that would occupy Islamic philosophy for the next centuries; in his broad-ranging work, his work on logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from prem ...

stands out particularly. In the eleventh century, Ibn Sina

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islami ...

, one of the greatest Muslim philosophers ever, developed his own unique school of philosophy known as Avicennism

Avicennism is a school of Persian philosophy which was established by Avicenna. He developed his philosophy throughout the course of his life after being deeply moved and concerned by the ''Metaphysics'' of Aristotle and studying it for over a ye ...

which had strong Aristotelian and Neoplatonist

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some id ...

roots. Al-Ghazali

Al-Ghazali ( – 19 December 1111; ), full name (), and known in Persian-speaking countries as Imam Muhammad-i Ghazali (Persian: امام محمد غزالی) or in Medieval Europe by the Latinized as Algazelus or Algazel, was a Persian poly ...

, a famous Muslim philosopher and theologian, took the approach to resolving apparent contradictions between reason and revelation. He understood the importance of philosophy and developed a complex response that rejected and condemned some of its teachings, while it also allowed him to accept and apply others. It was al-Ghazali's acceptance of demonstration (''apodeixis'') that led to a much more refined and precise discourse on epistemology and a flowering of Aristotelian logic and metaphysics in Muslim theological circles. Averroes

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psy ...

, the last notable Muslim peripatetic philosopher, defended the use of Aristotelian philosophy against this charge; his extensive works include noteworthy commentaries on Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

. In the twelfth century, the philosophy of illumination was founded by Shahab al-Din Suhrawardi. Although philosophy in its traditional Aristotelian form fell out of favor in much of the Arab world after the twelfth century, forms of mystical philosophy became more prominent.

After Averroes

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psy ...

, a vivid peripatetic philosophical school persisted in the eastern Muslim world during the Safavid Empire

Safavid Iran or Safavid Persia (), also referred to as the Safavid Empire, '. was one of the greatest Iranian empires after the 7th-century Muslim conquest of Persia, which was ruled from 1501 to 1736 by the Safavid dynasty. It is often conside ...

which scholars have termed as the School of Isfahan. It was founded by the Shia

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that the Islamic prophet Muhammad designated ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his successor (''khalīfa'') and the Imam (spiritual and political leader) after him, mos ...

philosopher Mir Damad and developed further by Mulla Sadra and others.

List

}), commonly known simply as Ibn Zafar al-Siqilli, was aphilosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

, polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

and Arab-Sicilian politician of the Norman period (1104 - 1170), and has come to be known in the West as "Niccolò Machiavelli

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli ( , , ; 3 May 1469 – 21 June 1527), occasionally rendered in English as Nicholas Machiavel ( , ; see below), was an Italian diplomat, author, philosopher and historian who lived during the Renaissance. ...

's Arab Precursor". Ibn Zafar was said to have authored 32 books., especially the ''Sulwān al-Muṭā fī Udwān al-Atbā'' ( ar, سلوان المطاع في عدوان الأتباع, , Consolation for the Ruler During the Hostility of his Subjects) is his magnum opus.

, -

, Al-Ghazali

Al-Ghazali ( – 19 December 1111; ), full name (), and known in Persian-speaking countries as Imam Muhammad-i Ghazali (Persian: امام محمد غزالی) or in Medieval Europe by the Latinized as Algazelus or Algazel, was a Persian poly ...

,

, Persia (Iran)

, 1058–1111

, Sufi/Ashari

, His main work The Incoherence of the Philosophers

''The Incoherence of the Philosophers'' (تهافت الفلاسفة ''Tahāfut al-Falāsifaʰ'' in Arabic) is the title of a landmark 11th-century work by the Persian theologian Abū Ḥāmid Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad al-Ghazali and a student o ...

made a turn in Islamic epistemology

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Epi ...

. His encounter with skepticism

Skepticism, also spelled scepticism, is a questioning attitude or doubt toward knowledge claims that are seen as mere belief or dogma. For example, if a person is skeptical about claims made by their government about an ongoing war then the p ...

made him believe that all causative events are not product of material conjunctions but are due to the Will of God. Later on, in the next century, Averroes

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psy ...

's rebuttal of al-Ghazali's ''Incoherence'' became known as The Incoherence of the Incoherence

''The Incoherence of the Incoherence'' ( ar, تهافت التهافت ''Tahāfut al-Tahāfut'') by Andalusian Muslim polymath and philosopher Averroes (Arabic , ''ibn Rushd'', 1126–1198) is an important Islamic philosophical treatise in w ...

.

, -

, Avempace

Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Yaḥyà ibn aṣ-Ṣā’igh at-Tūjībī ibn Bājja ( ar, أبو بكر محمد بن يحيى بن الصائغ التجيبي بن باجة), best known by his Latinised name Avempace (; – 1138), was an A ...

,

, Andalusia (Spain)

, 1095–1138

,

, His main philosophical idea is that the human soul could become one with the Divine through a hierarchy starting with sensing of the forms (containing less and less matter) to the impression of Active Intellect. His most important philosophical work is ''Tadbīr al-mutawaḥḥid'' (The Regime of the Solitary).

, -

, Ibn Tufail

Ibn Ṭufail (full Arabic name: ; Latinized form: ''Abubacer Aben Tofail''; Anglicized form: ''Abubekar'' or ''Abu Jaafar Ebn Tophail''; c. 1105 – 1185) was an Arab Andalusian Muslim polymath: a writer, Islamic philosopher, Islamic the ...

,

, Andalusia

(Spain)

, 1105–1185

,

, His work Hayy ibn Yaqdhan, is known as ''The Improvement of Human Reason'' in English and is a philosophical and allegorical novel which tells the story of a feral child

A feral child (also called wild child) is a young individual who has lived isolated from human contact from a very young age, with little or no experience of human care, social behavior, or language. The term is used to refer to children who h ...

named Hayy who is raised by a gazelle

A gazelle is one of many antelope species in the genus ''Gazella'' . This article also deals with the seven species included in two further genera, '' Eudorcas'' and '' Nanger'', which were formerly considered subgenera of ''Gazella''. A third ...

and is living alone without contact with other human beings. This work is continuing Avicenna's version of the story and is considered as a response to al-Ghazali

Al-Ghazali ( – 19 December 1111; ), full name (), and known in Persian-speaking countries as Imam Muhammad-i Ghazali (Persian: امام محمد غزالی) or in Medieval Europe by the Latinized as Algazelus or Algazel, was a Persian poly ...

's ''The Incoherence of the Philosophers

''The Incoherence of the Philosophers'' (تهافت الفلاسفة ''Tahāfut al-Falāsifaʰ'' in Arabic) is the title of a landmark 11th-century work by the Persian theologian Abū Ḥāmid Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad al-Ghazali and a student o ...

'', which had criticized Avicenna's philosophy.Nahyan A. G. Fancy (2006), "Pulmonary Transit and Bodily Resurrection: The Interaction of Medicine, Philosophy and Religion in the Works of Ibn al-Nafīs (died 1288)", pp. 95–102, ''Electronic Theses and Dissertations'', University of Notre Dame

The University of Notre Dame du Lac, known simply as Notre Dame ( ) or ND, is a private Catholic research university in Notre Dame, Indiana, outside the city of South Bend. French priest Edward Sorin founded the school in 1842. The main c ...

br>/ref> , - ,

Averroes

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psy ...

,  , Spain

(Andalusia)

, 1126–1198

, Peripatetic

, Being described as "founding father of secular thought in Western Europe", He was known by the nickname ''the Commentator'' for his precious commentaries on Aristotle's works. His main work was ''

, Spain

(Andalusia)

, 1126–1198

, Peripatetic

, Being described as "founding father of secular thought in Western Europe", He was known by the nickname ''the Commentator'' for his precious commentaries on Aristotle's works. His main work was ''The Incoherence of the Incoherence

''The Incoherence of the Incoherence'' ( ar, تهافت التهافت ''Tahāfut al-Tahāfut'') by Andalusian Muslim polymath and philosopher Averroes (Arabic , ''ibn Rushd'', 1126–1198) is an important Islamic philosophical treatise in w ...

'' in which he defended philosophy against al-Ghazali

Al-Ghazali ( – 19 December 1111; ), full name (), and known in Persian-speaking countries as Imam Muhammad-i Ghazali (Persian: امام محمد غزالی) or in Medieval Europe by the Latinized as Algazelus or Algazel, was a Persian poly ...

's claims in ''The Incoherence of the Philosophers

''The Incoherence of the Philosophers'' (تهافت الفلاسفة ''Tahāfut al-Falāsifaʰ'' in Arabic) is the title of a landmark 11th-century work by the Persian theologian Abū Ḥāmid Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad al-Ghazali and a student o ...

''. His other works were the ''Fasl al-Maqal'' and the ''Kitab al-Kashf''.

, -

, Afdal al-Din Kashani Afzal ad-Din Maragi Kashani ( fa, افضلالدین مَرَقی کاشانی) also known as Baba Afzal ( fa, بابا افضل) was a Persian poet and philosopher. Several dates have been suggested for his death, with the best estimate bein ...

,

, Persia (Iran)

, ?-1213

,

, He was involved in explaining the salvific power of self-awareness. That is: "To know oneself is to know the everlasting reality that is consciousness, and to know it is to be it." His ontology is interconnected with his epistemology

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Epi ...

, as he believes a full actualization of the potentialities of the world is only possible through self-knowledge.

, -

, Najmuddin Kubra

Najm ad-Dīn Kubrà ( fa, نجمالدین کبری) was a 13th-century Khwarezmian Sufi from Khwarezm and the founder of the Kubrawiya, influential in the Ilkhanate and Timurid dynasty. His method, exemplary of a "golden age" of Sufi metaphy ...

,

, Persia

, 1145–1220

, Sufism

, As the founder of the Kubrawiyya Sufi order,Henry Corbin

Henry Corbin (14 April 1903 – 7 October 1978)Shayegan, DaryushHenry Corbin in Encyclopaedia Iranica. was a French philosopher, theologian, and Iranologist, professor of Islamic studies at the École pratique des hautes études. He was in ...

, "''History of Islamic Philosophy''" and "''En Islam Iranien''". he is regarded as a pioneer of the Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, r ...

sm. His books are discussing dreams and visionary experience, among which is a Sufi commentary on the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , ...

.

, -

, Fakhr al-Din al-Razi

,

, Persia (Iran)

, 1149–1209

, Ashari

, His major work Tafsir-e Kabir included many philosophical thoughts, among which was the self-sufficiency

Self-sustainability and self-sufficiency are overlapping states of being in which a person or organization needs little or no help from, or interaction with, others. Self-sufficiency entails the self being enough (to fulfill needs), and a self-s ...

of the intellect. He believed that proofs based on tradition hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approva ...

could never lead to certainty but only to presumption

In the law of evidence, a presumption of a particular fact can be made without the aid of proof in some situations. The invocation of a presumption shifts the burden of proof from one party to the opposing party in a court trial.

There are two ...

. Al-Razi's rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification".Lacey, A.R. (1996), ''A Dictionary of Philosophy' ...

"holds an important place in the debate in the Islamic tradition on the harmonization of reason and revelation."

, -

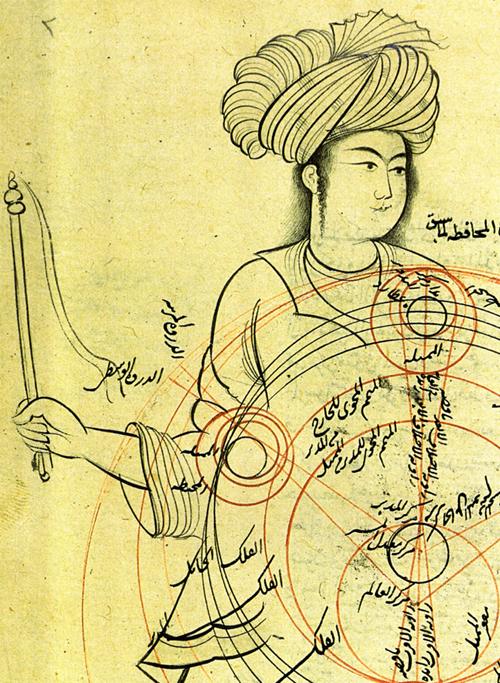

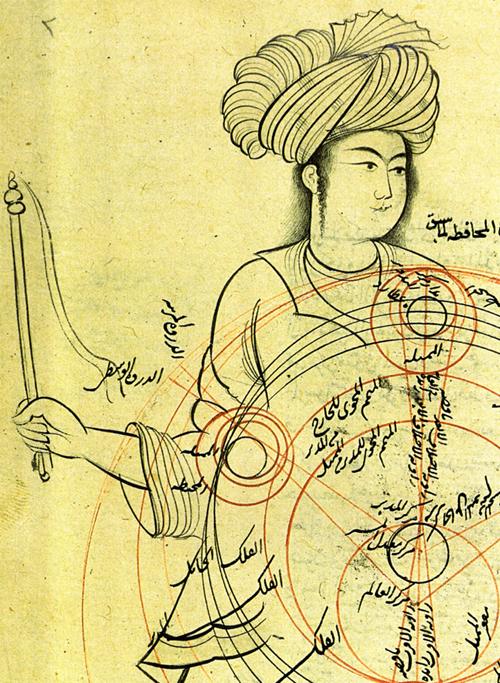

, Shahab al-Din Suhrawardi

,

, Persia (Iran)

, 1155–1191

, Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, r ...

, As the founder of Illuminationism, an important school in Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

ic mysticism

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning. It may also refer to the attainment of insight in ...

, The "light" in his "Philosophy of Illumination" is a divine source of knowledge which has significantly affected Islamic philosophy and esoteric

Western esotericism, also known as esotericism, esoterism, and sometimes the Western mystery tradition, is a term scholars use to categorise a wide range of loosely related ideas and movements that developed within Western society. These ideas ...

knowledge.

, -

, Ibn Arabi

Ibn ʿArabī ( ar, ابن عربي, ; full name: , ; 1165–1240), nicknamed al-Qushayrī (, ) and Sulṭān al-ʿĀrifīn (, , ' Sultan of the Knowers'), was an Arab Andalusian Muslim scholar, mystic, poet, and philosopher, extremely influen ...

,  , Spain

(Andalusia)

, 1165–1240

, Sufi

, He was an

, Spain

(Andalusia)

, 1165–1240

, Sufi

, He was an Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

Andalusian Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, r ...

mystic whose work ''Fusus al-Hikam'' (The Ringstones of Wisdom) can be described as a summary of his mystical beliefs concerning the role of different prophets in divine revelation.

, -

, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi

Muhammad ibn Muhammad ibn al-Hasan al-Tūsī ( fa, محمد ابن محمد ابن حسن طوسی 18 February 1201 – 26 June 1274), better known as Nasir al-Din al-Tusi ( fa, نصیر الدین طوسی, links=no; or simply Tusi in the West ...

,

, Persia (Iran)

, 1201–1274

,

, As a supporter of Avicennian logic

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic G ...

he was described by Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldun (; ar, أبو زيد عبد الرحمن بن محمد بن خلدون الحضرمي, ; 27 May 1332 – 17 March 1406, 732-808 AH) was an Arab

The Historical Muhammad', Irving M. Zeitlin, (Polity Press, 2007), p. 21; "It is, of ...

as the greatest of the later Persian scholars.Dabashi, Hamid. ''Khwajah Nasir al-Din Tusi: The philosopher/vizier and the intellectual climate of his times''. Routledge History of World Philosophies. Vol I. Corresponding with Sadr al-Din al-Qunawi

Ṣadr al-Dīn Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq ibn Muḥammad ibn Yūnus Qūnawī lternatively, Qūnavī, Qūnyawī ( fa, صدر الدین قونوی; 1207–1274), was a PersianF. E. Peters, "The Monotheists", Published by Princeton University Press ...

, the son-in-law of Ibn al-'Arabi, he thought mysticism, as disseminated by Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, r ...

principles of his time, was not appealing to his mind so he wrote his own book of philosophical Sufism entitled ''Awsaf al-Ashraf'' (The Attributes of the Illustrious).

, -

, Rumi

Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī ( fa, جلالالدین محمد رومی), also known as Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Balkhī (), Mevlânâ/Mawlānā ( fa, مولانا, lit= our master) and Mevlevî/Mawlawī ( fa, مولوی, lit= my ma ...

,

, Persia

, 1207–1273

, Sufi

, Described as the "most popular poet in America", he was an evolutionary thinker, in that he believed that all matter after devolution from the divine Ego experience an evolutionary cycle by which it return to the same divine Ego, which is due to an innate motive which he calls ''love''. Rumi's major work is the ''Maṭnawīye Ma'nawī'' (Spiritual Couplets) regarded by some Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, r ...

s as the Persian-language Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , si ...

. His other work, ''Fihi Ma Fihi'' (In It What's in It), includes seventy-one talks given on various occasions to his disciples.

, -

, Ibn al-Nafis

,  , Damascus

(Syria)

, 1213–1288

,

, His ''Al-Risalah al-Kamiliyyah fil Siera al-Nabawiyyah'' or''

, Damascus

(Syria)

, 1213–1288

,

, His ''Al-Risalah al-Kamiliyyah fil Siera al-Nabawiyyah'' or''Theologus Autodidactus

''Theologus Autodidactus'' ("The Self-taught Theologian"), originally titled ''The Treatise of Kāmil on the Prophet's Biography'' ( ar, الرسالة الكاملية في السيرة النبوية), also known as ''Risālat Fādil ibn Nātiq'' ...

'' is said to be the first theological novel in which he attempted to prove that the human mind is able to deduce the truths of the world through reasoning.Abu Shadi Al-Roubi (1982), ''Ibn Al-Nafis as a philosopher'', ''Symposium on Ibn al-Nafis'', Second International Conference on Islamic Medicine: Islamic Medical Organization, Kuwait (cf.

The abbreviation ''cf.'' (short for the la, confer/conferatur, both meaning "compare") is used in writing to refer the reader to other material to make a comparison with the topic being discussed. Style guides recommend that ''cf.'' be used onl ...

br>Ibn al-Nafis As a Philosopher''Encyclopedia of Islamic World'

He described this book as a defense of "the system of Islam and the Muslims' doctrines on the missions of prophets, the religious laws, the resurrection of the body, and the transitoriness of the world". , - , Qotb al-Din Shirazi ,

, Persia (Iran)

, 1217–1311

,

, He was a

, Persia (Iran)

, 1217–1311

,

, He was a Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, r ...

from Shiraz

Shiraz (; fa, شیراز, Širâz ) is the fifth-most-populous city of Iran and the capital of Fars Province, which has been historically known as Pars () and Persis. As of the 2016 national census, the population of the city was 1,565,572 p ...

who was famous for his commentary on Hikmat al-ishraq of Suhrawardi. His major work is the ''Durrat al-taj li-ghurratt al-Dubaj'' (Pearly Crown) which is an Encyclopedic work on philosophy including philosophical views on natural sciences, theology, logic, public affairs, ethnics, mysticism, astronomy, mathematics, arithmetic and music.

, -

, Ibn Sabin

,

, Andalusia

(Spain)

, 1236–1269

,

, He was a Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, r ...

philosopher, the last philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

of the Andalus, and was known for his replies to questions from Frederick II, the ruler of Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

. His school

A school is an educational institution designed to provide learning spaces and learning environments for the teaching of students under the direction of teachers. Most countries have systems of formal education, which is sometimes co ...

is a mixture of philosophical and Gnostic

Gnosticism (from grc, γνωστικός, gnōstikós, , 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems which coalesced in the late 1st century AD among Jewish and early Christian sects. These various groups emphasized p ...

thoughts.

, -

, Sayyid Haydar Amuli

,

, Persia

, 1319–1385

,

, As the main commentator of the Ibn Arabi

Ibn ʿArabī ( ar, ابن عربي, ; full name: , ; 1165–1240), nicknamed al-Qushayrī (, ) and Sulṭān al-ʿĀrifīn (, , ' Sultan of the Knowers'), was an Arab Andalusian Muslim scholar, mystic, poet, and philosopher, extremely influen ...

's mystic philosophy and the representative of Persian Imamah theosophy, he believes that the Imams

Imam (; ar, إمام '; plural: ') is an Islamic leadership position. For Sunni Muslims, Imam is most commonly used as the title of a worship leader of a mosque. In this context, imams may lead Islamic worship services, lead prayers, serve ...

who were gifted with mystical

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning. It may also refer to the attainment of insight in u ...

knowledge were not just guides to the Shia Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, r ...

s. He was both a critic of Shia whose religion was confined to legalistic system and Sufis who denied certain regulations issued from the Imams.

, -

, Taftazani

Sa'ad al-Din Masud ibn Umar ibn Abd Allah al-Taftazani ( fa, سعدالدین مسعودبن عمربن عبداللّه هروی خراسانی تفتازانی) also known as Al-Taftazani and Taftazani (1322–1390) was a Muslim Persian pol ...

,

, Persia

, 1322–1390

,

, Al-Taftazani's treatises, even the commentaries, are "standard books" for students of Islamic theology. His papers have been called a "compendium of the various views regarding the great doctrines of Islam".Al-Taftazani, Sad al-Din Masud ibn Umar ibn Abd Allah (1950). ''A Commentary on the Creed of Islam: Sad al-Din al-Taftazani on the Creed of Najm al-Din al-Nasafi'' (Earl Edgar Elder Trans.). New York: Columbia University Press. p. XX.

, -

, Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldun (; ar, أبو زيد عبد الرحمن بن محمد بن خلدون الحضرمي, ; 27 May 1332 – 17 March 1406, 732-808 AH) was an Arab

The Historical Muhammad', Irving M. Zeitlin, (Polity Press, 2007), p. 21; "It is, of ...

,

, Tunisia

, 1332–1406

, Ashari

, He is known for his The Muqaddimah which Arnold J. Toynbee

Arnold Joseph Toynbee (; 14 April 1889 – 22 October 1975) was an English historian, a philosopher of history, an author of numerous books and a research professor of international history at the London School of Economics and King's Colleg ...

called it "a philosophy of history

Philosophy of history is the philosophical study of history and its discipline. The term was coined by French philosopher Voltaire.

In contemporary philosophy a distinction has developed between ''speculative'' philosophy of history and ''crit ...

which is undoubtedly the greatest work of its kind."''Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various t ...

'', 15th ed., vol. 9, p. 148. Ernest Gellner

Ernest André Gellner FRAI (9 December 1925 – 5 November 1995) was a British- Czech philosopher and social anthropologist described by ''The Daily Telegraph'', when he died, as one of the world's most vigorous intellectuals, and by ''The ...

considered Ibn Khaldun's definition of government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government i ...

, "an institution which prevents injustice other than such as it commits itself", the best in the history of political theory

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships between them. Its topics include politics, ...

. His theory of social conflict

Social conflict is the struggle for agency or power in society.

Social conflict occurs when two or more people oppose each other in social interaction, and each exerts social power with reciprocity in an effort to achieve incompatible goals but ...

contrasts the sedentary life of city dwellers with the migratory life of nomadic people, which would result in conquering the cities by the desert warriors.

, -

, Abdul Karim Jili

,

, Iraq

, 1366–1424

, Sufi

, Jili was the primary systematizer and commentator of Ibn Arabi

Ibn ʿArabī ( ar, ابن عربي, ; full name: , ; 1165–1240), nicknamed al-Qushayrī (, ) and Sulṭān al-ʿĀrifīn (, , ' Sultan of the Knowers'), was an Arab Andalusian Muslim scholar, mystic, poet, and philosopher, extremely influen ...

's works. His ''Universal Man'' explains Ibn Arabi's teachings on reality and human perfection, which is among the masterpieces of Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, r ...

literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to ...

. Jili thought of the Absolute Being as a Self, which later on influenced Muhammad Iqbal

Sir Muhammad Iqbal ( ur, ; 9 November 187721 April 1938), was a South Asian Muslim writer, philosopher, Quote: "In Persian, ... he published six volumes of mainly long poems between 1915 and 1936, ... more or less complete works on philos ...

.

, -

, Jami

Nūr ad-Dīn 'Abd ar-Rahmān Jāmī ( fa, نورالدین عبدالرحمن جامی; 7 November 1414 – 9 November 1492), also known as Mawlanā Nūr al-Dīn 'Abd al-Rahmān or Abd-Al-Rahmān Nur-Al-Din Muhammad Dashti, or simply as J ...

,  , Persia (Iran)

, 1414–1492

, Sufi

, His Haft Awrang (Seven Thrones) includes seven stories, among which ''Salaman and Absal'' tells the story of a sensual attraction of a prince for his wet-nurse, through which Jami uses figurative symbols to depict the key stages of the

, Persia (Iran)

, 1414–1492

, Sufi

, His Haft Awrang (Seven Thrones) includes seven stories, among which ''Salaman and Absal'' tells the story of a sensual attraction of a prince for his wet-nurse, through which Jami uses figurative symbols to depict the key stages of the Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, r ...

path such as repentance. The mystical and philosophical explanations of the nature of divine mercy, is also among his works.

, -

, Bahāʾ al-dīn al-ʿĀmilī

Bahāʾ al‐Dīn Muḥammad ibn Ḥusayn al‐ʿĀmilī (also known as Sheikh Baha'i, fa, شیخ بهایی) (18 February 1547 – 1 September 1621) was an Iranian ArabEncyclopedia of Arabic Literature'. Taylor & Francis; 1998. . p. 85. Sh ...

,  , Persia

, 1547–1621

,

, Regarded as a leading scholar and mujaddid of the seventeenth century,

, Persia

, 1547–1621

,

, Regarded as a leading scholar and mujaddid of the seventeenth century,Encyclopædia Iranica

''Encyclopædia Iranica'' is a project whose goal is to create a comprehensive and authoritative English language encyclopedia about the history, culture, and civilization of Iranian peoples from prehistory to modern times.

Scope

The ''Encyc ...

, BAHĀʾ-AL-DĪN ʿĀMELĪ, SHAIKH MOḤAMMAD B. ḤOSAYN BAHĀʾĪ

' by E. Kohlberg. he worked on

tafsir

Tafsir ( ar, تفسير, tafsīr ) refers to exegesis, usually of the Quran. An author of a ''tafsir'' is a ' ( ar, مُفسّر; plural: ar, مفسّرون, mufassirūn). A Quranic ''tafsir'' attempts to provide elucidation, explanation, in ...

, hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approva ...

, grammar

In linguistics, the grammar of a natural language is its set of structural constraints on speakers' or writers' composition of clauses, phrases, and words. The term can also refer to the study of such constraints, a field that includes doma ...

and fiqh

''Fiqh'' (; ar, فقه ) is Islamic jurisprudence. Muhammad-> Companions-> Followers-> Fiqh.

The commands and prohibitions chosen by God were revealed through the agency of the Prophet in both the Quran and the Sunnah (words, deeds, and e ...

(jurisprudence). In his work ''Resāla fi’l-waḥda al-wojūdīya'' (Exposition of the concept of "Unity of Existences"), he states that the Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, r ...

s are the true believers, "calls for an unbiased assessment of their utterances, and refers to his own mystical experiences."

, -

, Mir Damad

,

, Persia (Iran)

, ?-1631

,

, Professing in the Neoplatonizing Islamic Peripatetic traditions of Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic ...

and Suhrawardi, he was the main figure (together with his student Mulla Sadra), of the cultural revival of Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

. He was also the central founder of the School of Isfahan, and is regarded as the Third Teacher (mu'alim al-thalith) after Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

and al-Farabi

Abu Nasr Muhammad Al-Farabi ( fa, ابونصر محمد فارابی), ( ar, أبو نصر محمد الفارابي), known in the West as Alpharabius; (c. 872 – between 14 December, 950 and 12 January, 951)PDF version was a renowned early Isl ...

. ''Taqwim al-Iman'' (Calendars of Faith), ''Kitab Qabasat al-Ilahiyah'' (Book of the Divine Embers of Fiery Kindling), ''Kitab al-Jadhawat'' (Book of Spiritual Attractions) and Sirat al-Mustaqim (The Straight Path) are among his 134 works.

, -

, Mir Fendereski

''Mir'' (russian: Мир, ; ) was a space station that operated in low Earth orbit from 1986 to 2001, operated by the Soviet Union and later by Russia. ''Mir'' was the first modular space station and was assembled in orbit from 1986 to&n ...

,

, Persia (Iran)

, 1562–1640

,

, He was trained in the works of Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic ...

, and Mulla Sadra studied under him. His main work''al-Resāla al-ṣenāʿiya'', is an examination of the arts and professions in perfect society, and combines a number of genres and subject areas such as political and ethical thought and metaphysics.

, -

, Mulla Sadra

,

, Persia (Iran)

, 1571–1641

, Shia

, According to Oliver Leaman, Mulla Sadra is the most important influential philosopher in the Muslim world in the last four hundred years. He is regarded as the master of Ishraqi

Illuminationism (Persian حكمت اشراق ''hekmat-e eshrāq'', Arabic: حكمة الإشراق ''ḥikmat al-ishrāq'', both meaning "Wisdom of the Rising Light"), also known as ''Ishrāqiyyun'' or simply ''Ishrāqi'' (Persian اشراق, Arab ...

school of Philosophy who combined the many areas of the Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

philosophies into what he called the Transcendent Theosophy

Transcendent theosophy or al-hikmat al-muta’āliyah (حكمت متعاليه), the doctrine and philosophy developed by Persian philosopher Mulla Sadra (d.1635 CE), is one of two main disciplines of Islamic philosophy that are currently live an ...

. He brought "a new philosophical insight in dealing with the nature of reality

Reality is the sum or aggregate of all that is real or existent within a system, as opposed to that which is only imaginary. The term is also used to refer to the ontological status of things, indicating their existence. In physical terms, re ...

" and created "a major transition from essentialism

Essentialism is the view that objects have a set of attributes that are necessary to their identity. In early Western thought, Plato's idealism held that all things have such an "essence"—an "idea" or "form". In ''Categories'', Aristotle sim ...

to existentialism

Existentialism ( ) is a form of philosophical inquiry that explores the problem of human existence and centers on human thinking, feeling, and acting. Existentialist thinkers frequently explore issues related to the meaning, purpose, and val ...

" in Islamic philosophy. He also created for the first time a "distinctly Muslim school of Hikmah based especially upon the inspired doctrines which form the very basis of Shiism," especially what contained in the Nahj al-Balagha

''Nahj al-Balagha'' ( ar, نَهْج ٱلْبَلَاغَة ', 'The Path of Eloquence') is the best-known collection of sermons, letters, and sayings attributed to Ali ibn Abi Talib, fourth Rashidun Caliph, first Shia Imam and the cousin and s ...

.

, -

, Qazi Sa’id Qumi

,

, Persia (Iran)

, 1633–1692

,

, He was the pupil of Rajab Ali Tabrizi, Muhsen Feyz

''Mul·lā'' "al-Muḥsin" "al-Fayḍ" al-Kāshānī (1598–1680; fa, ملا محسن فیض کاشانی) was an Iranian Twelver Shi'i Muslim, mystic, poet, philosopher, and muhaddith (died ''c''. 1680 ᴄᴇ).

Life

Mohsen Fayz Kashani was bor ...

and Abd al-Razzaq Lahiji

ʿAbd-Al-Razzāq B. ʿAlī B. Al-Hosayn Lāhījī (died c. 1072 AH 662 CE was an Iranian theologian, poet and philosopher. His mentor in philosophy was his father-in-law Mulla Sadra.

Life

Hailing from Lahijan in Gilan, he spent most of his li ...

, and wrote comments on the Theology attributed to Aristotle, a work which Muslim philosophers have always continued to read. His commentaries on al-Tawhid

Tawhid ( ar, , ', meaning "unification of God in Islam (Allāh)"; also romanized as ''Tawheed'', ''Tawhid'', ''Tauheed'' or ''Tevhid'') is the indivisible oneness concept of monotheism in Islam. Tawhid is the religion's central and single mo ...

by al-Shaykh al-Saduq

Abu Ja'far Muhammad ibn 'Ali ibn Babawayh al-Qummi ( Persian: ar, أَبُو جَعْفَر مُحَمَّد ٱبْن عَلِيّ ٱبْن بَابَوَيْه ٱلْقُمِيّ; –991), commonly referred to as Ibn Babawayh (Persian: ar, ...

is also famous.

, -

, Shah Waliullah

,

, India

, 1703–1762

,

, He attempted to reexamine Islamic theology in the view of modern changes. His main work ''The Conclusive Argument of God'' is about Muslim theology and is still frequently referred to by new Islamic circles. ''Al-Budur al-bazighah'' (The Full Moons Rising in Splendor) is another work of him in which he explains the basis of faith in view of rational and traditional arguments.

, -

, Syed Ameer Ali

Syed Ameer Ali Order of the Star of India (1849–1928) was an Indian/British Indian jurist hailing from the state of Oudh from where his father moved and settled down at Bengal Presidency. He was a prominent political leader, and author of a n ...

,

, India

, 1849–1928

, Modernist

, Sir Syed Ameer Ali was a British-Indian scholar achieving ''order of the star of India''. He was one of the leading Islamic scholars India who tried to bring modernity in Islam. Instead of revolting against British Empire, he tried to popularize modern education such as learning English language. Two of his most famous books are – ''The Spirit of Islam'' and ''Short History Of The Saracens''.

, -

, Muhammad Iqbal

Sir Muhammad Iqbal ( ur, ; 9 November 187721 April 1938), was a South Asian Muslim writer, philosopher, Quote: "In Persian, ... he published six volumes of mainly long poems between 1915 and 1936, ... more or less complete works on philos ...

,  , (British India)

Pakistan

, 1877–1938

, Modernist/

Sufi

, Other than being an eminent poet, he is recognized as the "Muslim philosophical thinker of modern times". He wrote two books on the topic of ''

, (British India)

Pakistan

, 1877–1938

, Modernist/

Sufi

, Other than being an eminent poet, he is recognized as the "Muslim philosophical thinker of modern times". He wrote two books on the topic of ''The Development of Metaphysics in Persia

''The Development of Metaphysics in Persia'' is the book form of Muhammad Iqbal's PhD thesis in philosophy at the University of Munich submitted in 1908 and published in the same year. It traces the development of metaphysics in Persia from the ...

'' and '' The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam'' In which he revealed his thoughts regarding Islamic Sufism explaining that it trigger the searching soul to a superior understanding of life. God, the meaning of prayer, human spirit and Muslim culture are among the other issues discussed in his works.

, -

, Seyed Muhammad Husayn Tabatabaei

,  , Persia (Iran)

, 1892–1981

, Shia

, He is famous for ''

, Persia (Iran)

, 1892–1981

, Shia

, He is famous for ''Tafsir al-Mizan

''Al-Mizan fi Tafsir al-Qur'an'' ( ar, الميزان في تفسير القرآن, "The balance in Interpretation of Quran"), more commonly known as ''Tafsir al-Mizan'' () or simply ''Al-Mizan'' (), is a tafsir (exegesis of the Quran) written by ...

'', the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , ...

ic exegesis

Exegesis ( ; from the Greek , from , "to lead out") is a critical explanation or interpretation of a text. The term is traditionally applied to the interpretation of Biblical works. In modern usage, exegesis can involve critical interpretation ...

. His philosophy is centered on the sociological treatment of human problems. In his later years he would often hold study meetings with Henry Corbin

Henry Corbin (14 April 1903 – 7 October 1978)Shayegan, DaryushHenry Corbin in Encyclopaedia Iranica. was a French philosopher, theologian, and Iranologist, professor of Islamic studies at the École pratique des hautes études. He was in ...

and Seyyed Hossein Nasr

Seyyed Hossein Nasr (; fa, سید حسین نصر, born April 7, 1933) is an Iranian philosopher and University Professor of Islamic studies at George Washington University.

Born in Tehran, Nasr completed his education in Iran and the Unite ...

, in which the classical texts of divine knowledge and gnosis along with what Nasr calls comparative gnosis were discussed. Shi'a Islam

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that the Islamic prophet Muhammad designated ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his successor (''khalīfa'') and the Imam (spiritual and political leader) after him, most ...

, ''The Principles of Philosophy and the Method of Realism'' ( fa, Usul-i-falsafeh va ravesh-i-ri'alism) and ''Dialogues with Professor Corbin'' ( fa, Mushabat ba Ustad Kurban) are among his works.

, -

, Ghulam Ahmed Perwez

,

, Pakistan

, 1903–1985

, Modernist/

Quranist

Quranism ( ar, القرآنية, translit=al-Qurʾāniyya'';'' also known as Quran-only Islam) Brown, ''Rethinking tradition in modern Islamic thought'', 1996: p.38-42 is a movement within Islam. It holds the belief that traditional religious cl ...

, He was a famous theologian from Pakistan inspired by Muhammad Iqbal

Sir Muhammad Iqbal ( ur, ; 9 November 187721 April 1938), was a South Asian Muslim writer, philosopher, Quote: "In Persian, ... he published six volumes of mainly long poems between 1915 and 1936, ... more or less complete works on philos ...

. Being a protege of Allama Muhammad Iqbal his main focus was to separate between ''"Deen"'' and ''"Madhab"''. According to him Islam was revelated as Deen which's main purpose was to create a successful and happy society. He rejected the idea of a state being ruled by Islamic scholars, although he also criticized western secularism. He firmly believed that Islam isn't based on blind faith but rational thinking. His most famous book is ''"Islam: A Challenge to Religion".''

, -

, Abul A'la Maududi

Abul A'la al-Maududi ( ur, , translit=Abū al-Aʿlā al-Mawdūdī; – ) was an Islamic scholar, Islamist ideologue, Muslim philosopher, jurist, historian, journalist, activist and scholar active in British India and later, following the part ...

,

, Pakistan

, 1903–1979

,

, His major work is The Meaning of the Qur'an in which he explains that The Quran is not a book of abstract ideas, but a Book which contains a message which causes a movement. Islam, he believes, is not a 'religion' in the sense this word is usually comprehended, but a system encompassing all areas of living. In his book ''Islamic Way of Life

''Islamic Way of Life'' (Urdu: ''Islam Ka Nizam Hayat'') is a book written by prominent Muslim Sayyid Abul Ala Maududi in Lahore

Lahore ( ; pnb, ; ur, ) is the second most populous city in Pakistan after Karachi and 26th most populou ...

'', he largely expanded on this view.

, -

, Henry Corbin

Henry Corbin (14 April 1903 – 7 October 1978)Shayegan, DaryushHenry Corbin in Encyclopaedia Iranica. was a French philosopher, theologian, and Iranologist, professor of Islamic studies at the École pratique des hautes études. He was in ...

,

, France

, 1903–1978

,

, He was a philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

, theologian

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

and professor of Islamic Studies

Islamic studies refers to the academic study of Islam, and generally to academic multidisciplinary "studies" programs—programs similar to others that focus on the history, texts and theologies of other religious traditions, such as Easter ...

at the Sorbonne in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

where he encountered Louis Massignon, and it was he who introduced Corbin to the writings of Suhrawardi whose work affected the course of Corbin's life.Corbin, Henryan article by Encyclopedia of Religion In his History of Islamic Philosophy, he refuted the view that philosophy among the Muslims came to an end after Averroes, showed rather that a vivid philosophical activity persisted in the eastern Muslim world – especially Iran. , - , Abdel Rahman Badawi , , Egypt , 1917–2002 , , He adopted existentialism since he wrote his ''Existentialist Time'' in 1943. His version of existentialism, according to his own description, differs from Heidegger's and other existentialists in that it gives preference to action rather than thought. in his later work,''Humanism And Existentialism In Arab Thought'', however, he tried to root his ideas in his own culture. , - ,

Morteza Motahhari

Morteza Motahhari ( fa, مرتضی مطهری, also Romanized as "Mortezā Motahharī"; 31 January 1919 – 1 May 1979) was an Iranian Twelver Shia scholar, philosopher, lecturer. Motahhari is considered to have an important influence on ...

,  , Persia (Iran)

, 1919–1979

, Shia

, Considered among the important influences on the ideologies of the

, Persia (Iran)

, 1919–1979

, Shia

, Considered among the important influences on the ideologies of the Islamic Republic

The term Islamic republic has been used in different ways. Some Muslim religious leaders have used it as the name for a theoretical form of Islamic theocratic government enforcing sharia, or laws compatible with sharia. The term has also been u ...

, he started from the Hawza

A hawza ( ar, حوزة) or ḥawzah ʿilmīyah ( ar, حوزة علمیة) is a seminary where Shi'a Muslim scholars are educated.

The word ''ḥawzah'' is found in Arabic as well as the Persian language. In Arabic, the word means "to hold s ...

of Qom

Qom (also spelled as "Ghom", "Ghum", or "Qum") ( fa, قم ) is the seventh largest metropolis and also the seventh largest city in Iran. Qom is the capital of Qom Province. It is located to the south of Tehran. At the 2016 census, its pop ...

. Then he taught philosophy in the University of Tehran

The University of Tehran (Tehran University or UT, fa, دانشگاه تهران) is the most prominent university located in Tehran, Iran. Based on its historical, socio-cultural, and political pedigree, as well as its research and teaching pro ...

for 22 years. Between 1965 and 1973, however, he gave regular lectures at the Hosseiniye Ershad in Northern Tehran, most of which have been turned into books on Islam, Iran, and historical topics.

, -

, Mohammad-Taqi Ja'fari

, location =

, Title = Allameh

, Period =

, Predecessor =

, Successor =

, ordination =

, post =

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Tabriz, Iran (formerly Varzeqan)

, death_date =

, death_place ...

,  , Persia (Iran)

, 1923–1998

, Shia

, He wrote many books on variety of fields, the most prominent of which are his 15-volume Interpretation and Criticism of

, Persia (Iran)

, 1923–1998

, Shia

, He wrote many books on variety of fields, the most prominent of which are his 15-volume Interpretation and Criticism of Rumi

Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī ( fa, جلالالدین محمد رومی), also known as Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Balkhī (), Mevlânâ/Mawlānā ( fa, مولانا, lit= our master) and Mevlevî/Mawlawī ( fa, مولوی, lit= my ma ...

's Masnavi

The ''Masnavi'', or ''Masnavi-ye-Ma'navi'' ( fa, مثنوی معنوی), also written ''Mathnawi'', or ''Mathnavi'', is an extensive poem written in Persian by Jalal al-Din Muhammad Balkhi, also known as Rumi. The ''Masnavi'' is one of the mos ...

, and his unfinished, 27-volume Translation and Interpretation of the Nahj al-Balagha

''Nahj al-Balagha'' ( ar, نَهْج ٱلْبَلَاغَة ', 'The Path of Eloquence') is the best-known collection of sermons, letters, and sayings attributed to Ali ibn Abi Talib, fourth Rashidun Caliph, first Shia Imam and the cousin and s ...

. These works shows his ideas in fields like anthropology, sociology, moral ethics, philosophy and mysticism.

, -

, Mohammed Arkoun

,

, Algeria

, 1928–2010

, Modernist

, He wrote on Islam and modernity trying to rethink the role of Islam in the contemporary world. In his book ''Rethinking Islam: Common Questions, Uncommon Answers'' he offers his responses to several questions for those who are concerned about the identity crisis which left many Muslims estranged from both modernity and tradition. ''The Unthought In Contemporary Islamic Thought'' is also among his works.

, -

, Israr Ahmed

,

, Pakistan

, 1932–2010

,

, He is the author of ''Islamic Renaissance: The Real Task Ahead'' in which he explains the theoretical idea of the Caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

system, arguing that it would only be possible by reviving Iman and faith among the Muslims in general and intelligentsia in particular. This would, he argues, fill the existing gap between new sciences, and Islamic divine knowledge.

, -

, Ali Shariati

,  , Persia (Iran)

, 1933–1977

, Modernist/

Shia

, Ali Shariati Mazinani (Persian: علی شریعتی مزینانی, 23 November 1933 – 18 June 1977) was an Iranian revolutionary and sociologist who focused on the sociology of religion. He is held as one of the most influential Iranian intellectuals of the 20th century and has been called the "ideologue of the Iranian Revolution", although his ideas ended up not forming the basis of the Islamic Republic

, -

,

, Persia (Iran)

, 1933–1977

, Modernist/

Shia

, Ali Shariati Mazinani (Persian: علی شریعتی مزینانی, 23 November 1933 – 18 June 1977) was an Iranian revolutionary and sociologist who focused on the sociology of religion. He is held as one of the most influential Iranian intellectuals of the 20th century and has been called the "ideologue of the Iranian Revolution", although his ideas ended up not forming the basis of the Islamic Republic

, -

, Abdollah Javadi-Amoli

Abdollah Javadi Amoli ( fa, عبدالله جوادی آملی; born ) is an Iranian Twelver Shi'a Marja. He is a conservative and principlist Iranian politician, philosopher and one of the prominent Islamic scholars of the Hawza. The offic ...

,

, Persia (Iran)

, 1933–

, Shia

, His works are dedicated to Islamic philosophy and especially Mulla Sadra's transcendent philosophy. Tafsir Tasnim is his exegesis of the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , ...

in which he follows Tabatabaei Tabatabaei ( ar, طباطبائي, ''Ṭabāṭabāʾī''; fa, طباطبایی, ''Ṭabâṭabâyī'') (also spelled Tabatabai, Tabatabaee, Tabatabaie, Tabatabaeyan) is a surname of Iranian/Persian origin Arabic family name (Tabataba’i), an adj ...

's Tafsir al-Mizan

''Al-Mizan fi Tafsir al-Qur'an'' ( ar, الميزان في تفسير القرآن, "The balance in Interpretation of Quran"), more commonly known as ''Tafsir al-Mizan'' () or simply ''Al-Mizan'' (), is a tafsir (exegesis of the Quran) written by ...

, in that he tries to interpret a verse based on other verses. His other work ''As-Saareh-e-Khelqat'' is a discussion about the philosophy of faith and evidence of the existence of God.

, -

, Seyyed Hossein Nasr

Seyyed Hossein Nasr (; fa, سید حسین نصر, born April 7, 1933) is an Iranian philosopher and University Professor of Islamic studies at George Washington University.

Born in Tehran, Nasr completed his education in Iran and the Unite ...

,  , Persia (Iran)

, 1933–

, Sufi/Shia

, He is a major perennialist thinker. His works defend Islamic and perennialist doctrines and principles while challenging the theoretical underpinnings of modern science. He argues that knowledge has been desacralized in the modern period, that is, separated from its divine source—God—and calls for its resacralization through sacred traditions and sacred science. His

, Persia (Iran)

, 1933–

, Sufi/Shia

, He is a major perennialist thinker. His works defend Islamic and perennialist doctrines and principles while challenging the theoretical underpinnings of modern science. He argues that knowledge has been desacralized in the modern period, that is, separated from its divine source—God—and calls for its resacralization through sacred traditions and sacred science. His environmental philosophy

Environmental philosophy is a branch of philosophy that is concerned with the natural environment and humans' place within it. It asks crucial questions about human environmental relations such as "What do we mean when we talk about nature?" "What ...

is expressed in terms of Islamic environmentalism and the resacralization of nature.

, -

, Sadiq Jalal al-Azm

,  , Turkey

, 1934–2016

,

, He was working on

, Turkey

, 1934–2016

,

, He was working on Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and ...

, though, later in his life, he put greater emphasis on the Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

ic world and its relationship to the West. He was also a supporter of human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

, intellectual freedom and free speech.

, -

, Mohammad-Taqi Mesbah-Yazdi

Ayatollah Taqi Mesbah ( fa, تقی مصباح; born Taqi Givechi, fa, تقی گیوهچی), commonly known as Mohammad-Taqi Mesbah-Yazdi ( fa, محمدتقی مصباح یزدی, 31 January 1935 – 1 January 2021) was an Iranian Shi' ...

,

, Persia (Iran)

, 1934–2021

, Shia

, He is an Islamic Faqih who has also studied works of Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic ...

and Mulla Sadra. He supports Islamic philosophy

Islamic philosophy is philosophy that emerges from the Islamic tradition. Two terms traditionally used in the Islamic world are sometimes translated as philosophy—falsafa (literally: "philosophy"), which refers to philosophy as well as logic, ...

and in particular Mulla Sadra's transcendent philosophy. His book ''Philosophical Instructions: An Introduction to Contemporary Islamic Philosophy'' is translated into English.

, -

, Mohammad Baqir al-Sadr

Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr ( ar, آية الله العظمى السيد محمد باقر الصدر; 1 March 1935 – 9 April 1980), also known as al-Shahīd al-Khāmis (the fifth martyr), was an Iraqi philosopher, and the ideological founde ...

,

, Iraq

, 1935–1980

, Shia

, He was an Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

i Shia

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that the Islamic prophet Muhammad designated ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his successor (''khalīfa'') and the Imam (spiritual and political leader) after him, mos ...

philosopher and founder of the Islamic Dawa Party

The Islamic Dawa Party, also known as the Islamic Call Party ( ar, حزب الدعوة الإسلامية, Ḥizb ad-Daʿwa al-Islāmiyya), is an Shia Islamist political party in Iraq. Dawa and the Supreme Islamic Iraqi Council are two of the ...

. His ''Falsafatuna'' (Our Philosophy) is a collection of basic ideas concerning the world, and his way of considering it. These concepts are divided into two researches: The theory of knowledge, and the philosophical notion of the world.

, -

, Mohammed Abed al-Jabri

Mohammed Abed Al Jabri ( ar, محمد عابد الجابري; 27 December 1935 – 3 May 2010 Rabat) was one of the most known Moroccan and Arab philosophers; he taught philosophy, Arab philosophy, and Islamic thought in Mohammed V University ...

,

, Morocco

, 1935–2010

, Modernist

, His work ''Democracy, Human Rights and Law in Islamic Thought'' while shows the distinctive nationality of the Arabs, reject the philosophical discussion which have tried to ignore its democratic deficits. Working in the tradition of Avincenna and Averroes

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psy ...

, he emphasizes that concepts such as democracy and law cannot rely on old traditions, nor could be import, but should be created by today's Arabs themselves. ''The Formation of Arab Reason: Text, Tradition and the Construction of Modernity in the Arab World'' is also among his works.

, -

, Abdolkarim Soroush

Abdolkarim Soroush ( ; born Hossein Haj Faraj Dabbagh (born 1945; fa, حسين حاج فرج دباغ), is an Iranian Islamic thinker, reformer, Rumi scholar, public intellectual, and a former professor of philo ...

,  , Persia (Iran)

, 1945–

, Shia/

Neoplatonist

, Being interested in the philosophy of religion and the philosophical system of

, Persia (Iran)

, 1945–

, Shia/

Neoplatonist

, Being interested in the philosophy of religion and the philosophical system of Rumi

Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī ( fa, جلالالدین محمد رومی), also known as Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Balkhī (), Mevlânâ/Mawlānā ( fa, مولانا, lit= our master) and Mevlevî/Mawlawī ( fa, مولوی, lit= my ma ...

, his book ''the evolution and devolution of religious knowledge'' argues that "a religion (such as Islam) may be divine and unchanging, but our understanding of religion remains in a continuous flux and a totally human endeavor."

, -

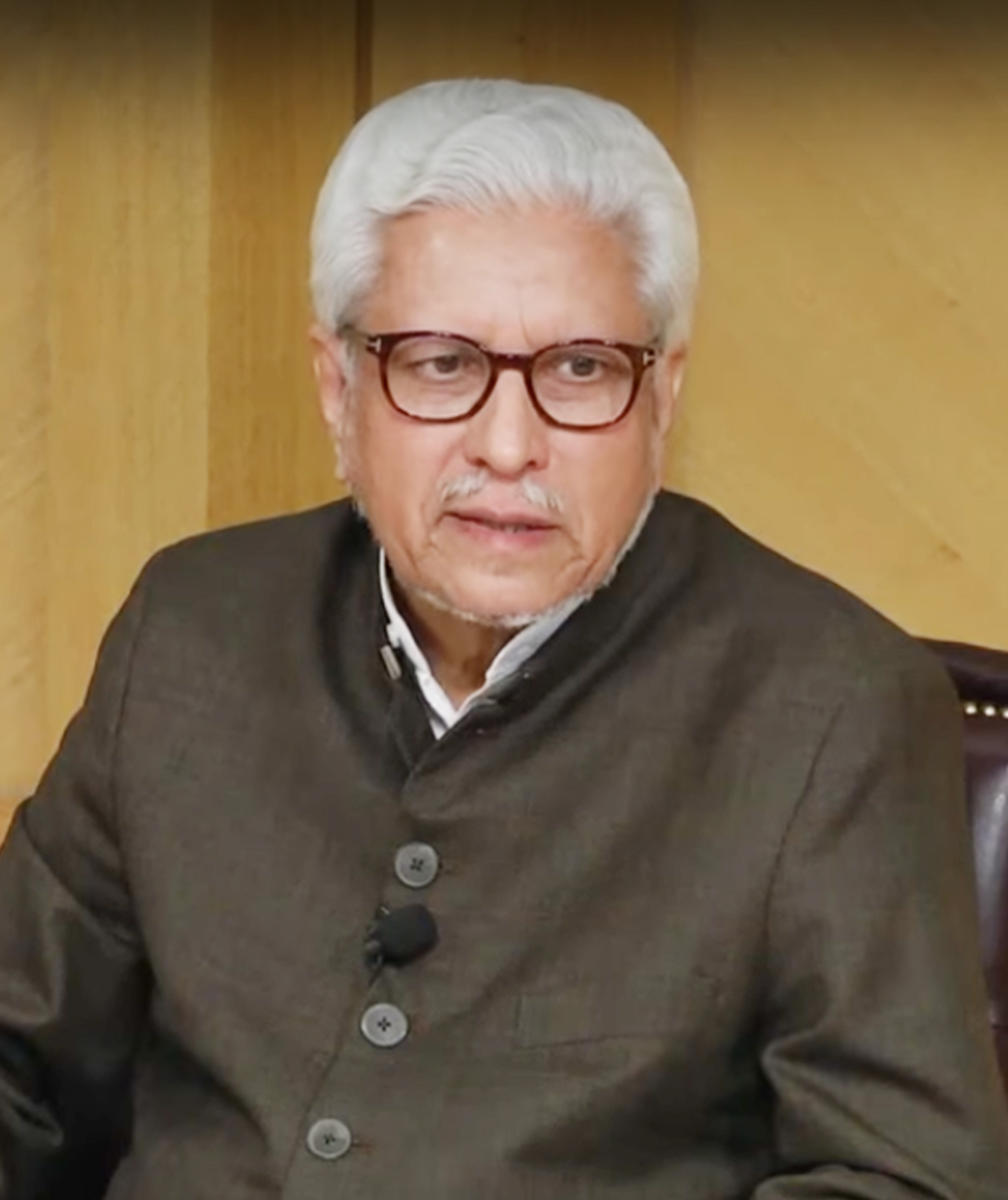

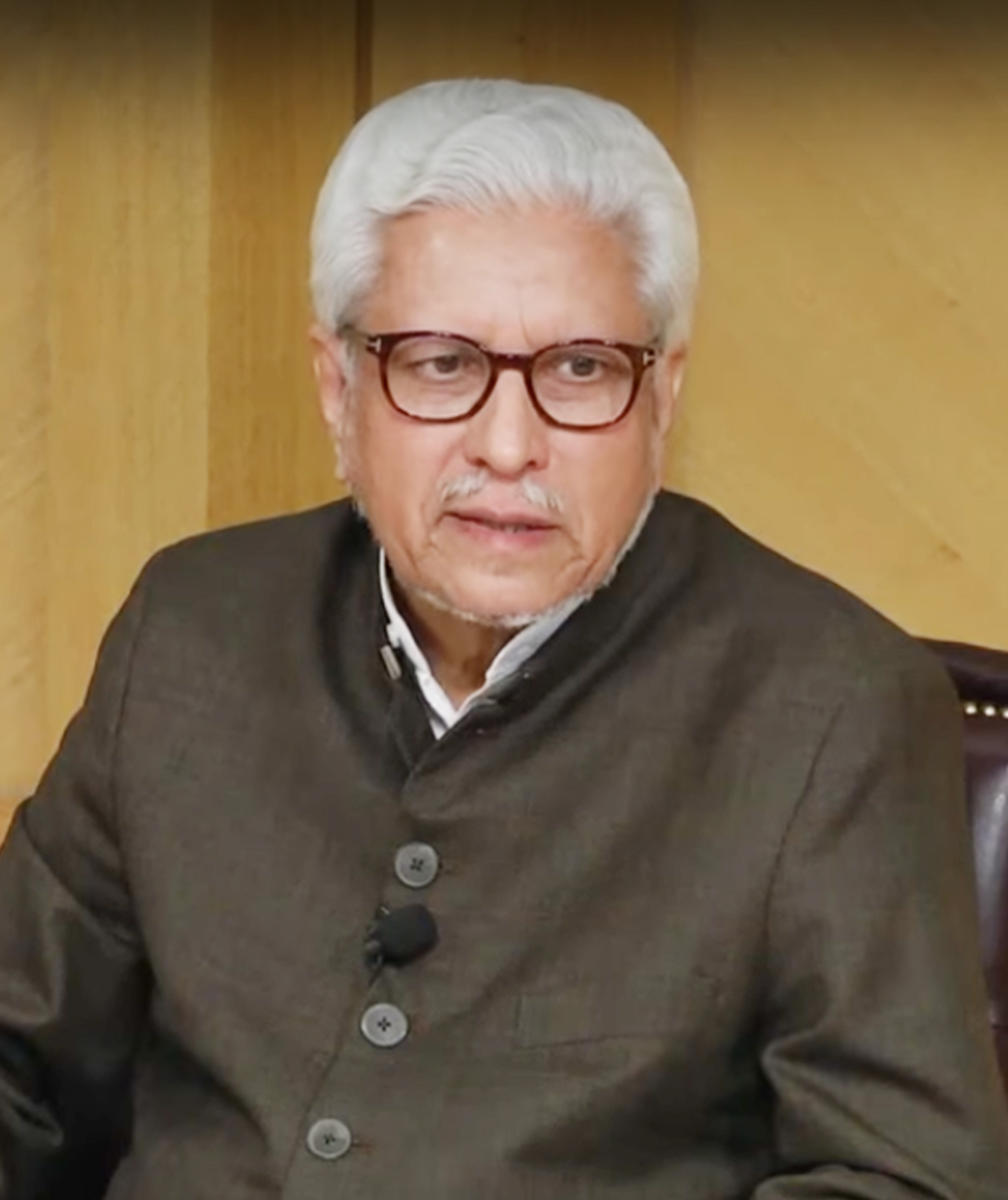

, Javed Ahmed Ghamidi

Javed Ahmad Ghamidi ( ur, , translit=Jāvēd Aḥmad Ghāmidī; April 7, 1952) is a Pakistani philosopher, educationist, and scholar of Islam. He is also the founding President of Al-Mawrid Institute of Islamic Sciences and its sister organisat ...

,  , Pakistan

, 1951-

, Modernist

, Javed Ahmed Ghamidi is a Pakistani theologian. He is regarded as one of the contemporary modernists of Islamic world. Like ''Parwez'' he also promotes rationalism and secular thought with deen. Ghamidi is also popular for his moderate

, Pakistan

, 1951-

, Modernist

, Javed Ahmed Ghamidi is a Pakistani theologian. He is regarded as one of the contemporary modernists of Islamic world. Like ''Parwez'' he also promotes rationalism and secular thought with deen. Ghamidi is also popular for his moderate fatwa

A fatwā ( ; ar, فتوى; plural ''fatāwā'' ) is a legal ruling on a point of Islamic law (''sharia'') given by a qualified '' Faqih'' (Islamic jurist) in response to a question posed by a private individual, judge or government. A jurist ...

s. Ghamidi also holds the view of democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose g ...

being compatible with Islam.

, -

, Gary Legenhausen

,

, USA

, 1953–

,

, ''Islam and Religious Pluralism'' is among his works in which he advocates "non-reductive religious pluralism". In his paper "The Relationship between Philosophy and Theology in the Postmodern Age" he is trying to examine whether philosophy can agree with theology.

, -

, Mostafa Malekian

,

, Persia (Iran)

, 1956–

, Shia

, He is working on ''Rationality and Spirituality'' in which he is trying to make Islam and reasoning compatible. His major work ''A Way to Freedom'' is about spirituality and wisdom.

, -

, Insha-Allah Rahmati

,

, Persia (Iran)

, 1966–

,

, His fields of can be summarized as follows: Ethics

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concer ...

and Philosophy of Religion

Philosophy of religion is "the philosophical examination of the central themes and concepts involved in religious traditions". Philosophical discussions on such topics date from ancient times, and appear in the earliest known texts concerning p ...

and Islamic Philosophy

Islamic philosophy is philosophy that emerges from the Islamic tradition. Two terms traditionally used in the Islamic world are sometimes translated as philosophy—falsafa (literally: "philosophy"), which refers to philosophy as well as logic, ...

. Most of his work in these three areas.

, -

, Shabbir Akhtar

Shabbir Akhtar is a British Muslim philosopher, poet, researcher, writer and multilingual scholar. He is on the Faculty of Theology and Religions at the University of Oxford. His interests include political Islam, Quranic exegesis, revival of ...

,

, England

, 1960–

, Neo-orthodox Analytical philosophy

, This Cambridge-trained thinker is trying to revive the tradition of Sunni Islamic philosophy, defunct since Ibn Khaldun, against the background of western analytical philosophical method. His major treatise is ''The Quran and the Secular Mind'' (2007).

, -

, Tariq Ramadan

,  , Switzerland/

France

, 1962–

, Modernist

, Working mainly on Islamic theology and the place of Muslims in the West, he believes that western Muslims must think up a "Western Islam" in accordance to their own social circumstances.

, Switzerland/

France

, 1962–

, Modernist

, Working mainly on Islamic theology and the place of Muslims in the West, he believes that western Muslims must think up a "Western Islam" in accordance to their own social circumstances.

See also

* Lists of philosophers *Islamic philosophy