Islamic Modernism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Islamic modernism is a movement that has been described as "the first

, Dr. Yasir Qadhi April 22, 2014 According to Quintan Wiktorowicz:

Muhammad 'Abduh and his movement have sometimes been referred to as "Neo-''Mu'tazilites''" in reference to the '' According to Oxford Bibliographies, the early Islamic Modernists (al-Afghani and Muhammad Abdu) used the term "salafiyya" to refer to their attempt at renovation of Islamic thought, and this movement is often known in the

According to Oxford Bibliographies, the early Islamic Modernists (al-Afghani and Muhammad Abdu) used the term "salafiyya" to refer to their attempt at renovation of Islamic thought, and this movement is often known in the

Islamic modernist discourse emerged as an intellectual movement in the second quarter of nineteenth century; during an era of wide-ranging reforms initiated across the

Islamic modernist discourse emerged as an intellectual movement in the second quarter of nineteenth century; during an era of wide-ranging reforms initiated across the

The theological views of the Azharite scholar Muhammad 'Abduh (d. 1905) were greatly shaped by the 19th century Ottoman intellectual discourse. Similar to the early Ottoman modernists, Abduh tried to bridge the gap between Enlightenment ideals and traditional religious values. He believed that classical Islamic theology was intellectually vigorous and portrayed ''

The theological views of the Azharite scholar Muhammad 'Abduh (d. 1905) were greatly shaped by the 19th century Ottoman intellectual discourse. Similar to the early Ottoman modernists, Abduh tried to bridge the gap between Enlightenment ideals and traditional religious values. He believed that classical Islamic theology was intellectually vigorous and portrayed '' Commencing in the late nineteenth century and impacting the twentieth-century, Muhammed Abduh and his followers undertook an educational and social project to defend, modernize and revitalize Islam to match Western institutions and social processes. Its most prominent intellectual founder,

Commencing in the late nineteenth century and impacting the twentieth-century, Muhammed Abduh and his followers undertook an educational and social project to defend, modernize and revitalize Islam to match Western institutions and social processes. Its most prominent intellectual founder,

By Noor al-Deen Atabek, onislam.net, 30 March 2005

In popular Western discourse during the early twentieth century; the term "''

Historian Henri Lauzière asserts that modernist intellectuals like Abduh and Afghani had not identified their movement with "''Salafiyya''". On the other hand, Islamic revivalists like :ar:محمود شكري الآلوسي, Mahmud Shukri Al-Alusi (1856–1924 C.E), Rashid Rida, Muhammad Rashid Rida (1865–1935 C.E), Jamal al-Din Qasimi, Jamal al-Din al-Qasimi (1866–1914 C.E), etc. used "''Salafiyya''" as a term primarily to denote the traditionalist Sunni theology, Traditionalist theology (Islam), Atharism. Rida also regarded the

Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

ideological response to the Western cultural challenge" attempting to reconcile the Islamic faith with modern values such as democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose g ...

, civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ...

, rationality

Rationality is the quality of being guided by or based on reasons. In this regard, a person acts rationally if they have a good reason for what they do or a belief is rational if it is based on strong evidence. This quality can apply to an ab ...

, equality, and progress

Progress is the movement towards a refined, improved, or otherwise desired state. In the context of progressivism, it refers to the proposition that advancements in technology, science, and social organization have resulted, and by extension w ...

.''Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World'', Thompson Gale (2004) It featured a "critical reexamination of the classical conceptions and methods of jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, or legal theory, is the theoretical study of the propriety of law. Scholars of jurisprudence seek to explain the nature of law in its most general form and they also seek to achieve a deeper understanding of legal reasoning ...

" and a new approach to Islamic theology

Schools of Islamic theology are various Islamic schools and branches in different schools of thought regarding '' ʿaqīdah'' (creed). The main schools of Islamic Theology include the Qadariyah, Falasifa, Jahmiyya, Murji'ah, Muʿtazila, Batin ...

and Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , ...

ic exegesis

Exegesis ( ; from the Greek , from , "to lead out") is a critical explanation or interpretation of a text. The term is traditionally applied to the interpretation of Biblical works. In modern usage, exegesis can involve critical interpretation ...

(''Tafsir

Tafsir ( ar, تفسير, tafsīr ) refers to exegesis, usually of the Quran. An author of a ''tafsir'' is a ' ( ar, مُفسّر; plural: ar, مفسّرون, mufassirūn). A Quranic ''tafsir'' attempts to provide elucidation, explanation, in ...

''). A contemporary definition describes it as an "effort to re-read Islam's fundamental sources—the Qur'an and the Sunna, (the practice of the Prophet) —by placing them in their historical context, and then reinterpreting them, non-literally, in the light of the modern context."

It was one of the of several Islamic movements – including Islamic secularism, Islamism

Islamism (also often called political Islam or Islamic fundamentalism) is a political ideology which posits that modern State (polity), states and Administrative division, regions should be reconstituted in constitutional, Economics, econom ...

, and Salafism

The Salafi movement or Salafism () is a reform branch movement within Sunni Islam that originated during the nineteenth century. The name refers to advocacy of a return to the traditions of the "pious predecessors" (), the first three generat ...

– that emerged in the middle of the 19th century in reaction to the rapid changes of the time, especially the perceived onslaught of Western civilization and colonialism

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose their reli ...

on the Muslim world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. I ...

. Prominent leaders of the movement include Sir Sayyid Ahmed Khan, Namik Kemal, Rifa'a al-Tahtawi, Muhammad Abduh

; "The Theology of Unity")

, alma_mater = Al-Azhar University

, office1 = Grand Mufti of Egypt

, term1 = 1899 – 1905

, Sufi_order = Shadhiliyya

, disciple_of =

, awards =

, in ...

(former Sheikh of Al-Azhar University

, image = جامعة_الأزهر_بالقاهرة.jpg

, image_size = 250

, caption = Al-Azhar University portal

, motto =

, established =

*970/972 first foundat ...

), Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani

Sayyid Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī (Pashto/ fa, سید جمالالدین افغانی), also known as Sayyid Jamāl ad-Dīn Asadābādī ( fa, سید جمالالدین اسدآبادی) and commonly known as Al-Afghani (1 ...

and South Asian poet Muhammad Iqbal

Sir Muhammad Iqbal ( ur, ; 9 November 187721 April 1938), was a South Asian Muslim writer, philosopher, Quote: "In Persian, ... he published six volumes of mainly long poems between 1915 and 1936, ... more or less complete works on philos ...

. In the Indian subcontinent, the movement is also known as Farahi, and is mainly regarded as the school of thought named after Hamiduddin Farahi.

Since its inception, Islamic modernism has suffered from co-option

Co-option (also co-optation, sometimes spelt coöption or coöptation) has two common meanings.

It may refer to the process of adding members to an elite group at the discretion of members of the body, usually to manage opposition and so maintai ...

of its original reformism by both secularist rulers and by "the official ''ulama

In Islam, the ''ulama'' (; ar, علماء ', singular ', "scholar", literally "the learned ones", also spelled ''ulema''; feminine: ''alimah'' ingularand ''aalimath'' lural are the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious ...

''" whose "task it is to legitimise" rulers' actions in religious terms.

Islamic modernism differs from secularism in that it insists on the importance of religious faith in public life, and from Salafism

The Salafi movement or Salafism () is a reform branch movement within Sunni Islam that originated during the nineteenth century. The name refers to advocacy of a return to the traditions of the "pious predecessors" (), the first three generat ...

or Islamism

Islamism (also often called political Islam or Islamic fundamentalism) is a political ideology which posits that modern State (polity), states and Administrative division, regions should be reconstituted in constitutional, Economics, econom ...

in that it embraces contemporary European institutions, social processes, and values. One expression of Islamic modernism, formulated by Mahathir Mohammed, is that "only when Islam is interpreted so as to be relevant in a world which is different from what it was 1400 years ago, can Islam be regarded as a religion for all ages." Warde, ''Islamic finance in the global economy'', 2000: p.127

Overview

Relations with Arab Salafism

During the second half of the 19th century, numerous Muslim reformers began efforts to reconcile Islamic values with the social and intellectual ideas of theAge of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

by purging Islam from alleged alterations and adhering to the basic tenets held during the Rashidun

, image = تخطيط كلمة الخلفاء الراشدون.png

, caption = Calligraphic representation of Rashidun Caliphs

, birth_place = Mecca, Hejaz, Arabia present-day Saudi Arabia

, known_for = Companions of ...

era. Their movement is regarded as the precursor to Islamic Modernism.Henri Lauzière ''The Making of Salafism: Islamic Reform in the Twentieth Century'' Columbia University Press

Columbia University Press is a university press based in New York City, and affiliated with Columbia University. It is currently directed by Jennifer Crewe (2014–present) and publishes titles in the humanities and sciences, including the fie ...

2015 The origins of Arab Salafiyya movement from the modernist movement of Jamal al-Din al-Afghani and Muhammad Abduh

; "The Theology of Unity")

, alma_mater = Al-Azhar University

, office1 = Grand Mufti of Egypt

, term1 = 1899 – 1905

, Sufi_order = Shadhiliyya

, disciple_of =

, awards =

, in ...

is mentioned by some authors, although other scholars note that Modernism only influenced Salafism

The Salafi movement or Salafism () is a reform branch movement within Sunni Islam that originated during the nineteenth century. The name refers to advocacy of a return to the traditions of the "pious predecessors" (), the first three generat ...

.On Salafi Islam , IV Conclusion, Dr. Yasir Qadhi April 22, 2014 According to Quintan Wiktorowicz:

There has been some confusion in recent years because both the Islamic modernists and the contemporary Salafis refer (referred) to themselves as al-salafiyya, leading some observers to erroneously conclude a common ideological lineage. The earlier salafiyya (modernists), however, were predominantly rationalist Asharis.

Muhammad 'Abduh and his movement have sometimes been referred to as "Neo-''Mu'tazilites''" in reference to the ''

Mu'tazila

Muʿtazila ( ar, المعتزلة ', English: "Those Who Withdraw, or Stand Apart", and who called themselves ''Ahl al-ʿAdl wa al-Tawḥīd'', English: "Party of ivineJustice and Oneness f God); was an Islamic group that appeared in early Islami ...

'' school of theology. Some have said Abduh's ideas are congruent to ''Mu'tazilism''. Abduh himself denied being either ''Ash'ari

Ashʿarī theology or Ashʿarism (; ar, الأشعرية: ) is one of the main Sunnī schools of Islamic theology, founded by the Muslim scholar, Shāfiʿī jurist, reformer, and scholastic theologian Abū al-Ḥasan al-Ashʿarī in th ...

'' or a ''Mu'tazilite'', although he only denied being a ''Mu'tazilite'' on the basis that he rejected strict ''taqlid

''Taqlid'' (Arabic تَقْليد ''taqlīd'') is an Islamic term denoting the conformity of one person to the teaching of another. The person who performs ''taqlid'' is termed ''muqallid''. The definite meaning of the term varies depending on con ...

'' (conformity) to one group.

West

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some ...

as "Islamic modernism," although it is very different from what is called the ''Salafiyya'', which generally refers to movements such as ''Ahl-i Hadith

Ahl-i Hadith or Ahl-e-Hadith ( bn, আহলে হাদীছ, hi, एहले हदीस, ur, اہلِ حدیث, ''people of hadith'') is a Salafi reform movement that emerged in North India in the mid-nineteenth century from the teac ...

'', Wahhabism

Wahhabism ( ar, ٱلْوَهَّابِيَةُ, translit=al-Wahhābiyyah) is a Sunni Islamic revivalist and fundamentalist movement associated with the reformist doctrines of the 18th-century Arabian Islamic scholar, theologian, preacher, and ...

, etc. Associate Professor

Associate professor is an academic title with two principal meanings: in the North American system and that of the ''Commonwealth system''.

Overview

In the '' North American system'', used in the United States and many other countries, it is ...

of Middle Eastern History

The Middle East, interchangeable with the Near East, is home to one of the Cradles of Civilization and has seen many of the world's oldest cultures and civilizations. The region's history started from the earliest human settlements and continue ...

at Northwestern University

Northwestern University is a private research university in Evanston, Illinois. Founded in 1851, Northwestern is the oldest chartered university in Illinois and is ranked among the most prestigious academic institutions in the world.

Charte ...

Henri Lauziere disputes the notion that al-Afghani and 'Abduh advocated a modernist movement of Salafism. According to Lauziere:"...based on what the technical term Salafism meant to Muslim religious specialists until the early twentieth century, al-Afghani and Abduh were hardly Salafis to begin with. No wonder they never claimed the label for themselves.Islamic Modernism began as an intellectual movement during the Tanzimat era and was part of the Ottoman constitutional movement and newly emerging patriotic trends of Ottomanism during the mid-19th century. It advocated for novel redefinitions of Ottoman imperial structure, bureaucratic reforms, implementing liberal constitution, centralisation, parliamentary system and was supportive of the Young Ottoman movement. Although modernist activists agreed with the conservative Ottoman clergy in emphasising the Muslim character of the empire, they also had fierce disputes with them. While the Ottoman clerical establishment called for Muslim unity through the preservation of the dynastic authority and unquestionable

allegiance

An allegiance is a duty of fidelity said to be owed, or freely committed, by the people, subjects or citizens to their state or sovereign.

Etymology

From Middle English ''ligeaunce'' (see medieval Latin ''ligeantia'', "a liegance"). The ''al ...

to the Ottoman Sultan

The sultans of the Ottoman Empire ( tr, Osmanlı padişahları), who were all members of the Ottoman dynasty (House of Osman), ruled over the transcontinental empire from its perceived inception in 1299 to its dissolution in 1922. At its hei ...

; modernist intellectuals argued that imperial unity was better served through parliamentary reforms and enshrining equal treatment of all Ottoman subjects; Muslim and non-Muslim. The modernist elites frequently invoked religious slogans to gain support for cultural and educational efforts as well as their political efforts to unite the Ottoman empire under a secular constitutional order.

On the other hand, ''Salafiyya

The Salafi movement or Salafism () is a reform branch movement within Sunni Islam that originated during the nineteenth century. The name refers to advocacy of a return to the traditions of the "pious predecessors" (), the first three generat ...

'' movement emerged as an independent revivalist trend in Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

amongst the scholarly circles of scripture-oriented Damascene ''ulema

In Islam, the ''ulama'' (; ar, علماء ', singular ', "scholar", literally "the learned ones", also spelled ''ulema''; feminine: ''alimah'' ingularand ''aalimath'' lural are the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious ...

'' during the 1890s. Although Salafis shared many of the socio-political grievances of the modernist activists, they held different objectives from both the modernist and the wider constitutionalist movements. While the Salafis opposed the autocratic policies of the Sultan Abdul Hamid II and the Ottoman clergy; they also intensely denounced the secularising and centralising tendencies of ''Tanzimat

The Tanzimat (; ota, تنظيمات, translit=Tanzimāt, lit=Reorganization, ''see'' nizām) was a period of reform in the Ottoman Empire that began with the Gülhane Hatt-ı Şerif in 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 187 ...

'' reforms brought forth by the Constitutionalist activists, accusing them of emulating Europeans

Europeans are the focus of European ethnology, the field of anthropology related to the various ethnic groups that reside in the states of Europe. Groups may be defined by common genetic ancestry, common language, or both. Pan and Pfeil (20 ...

. Set apart by their status as ''Ulema'', Salafi scholars called for an Islamic solution to the social, political and technological challenges faced by Muslims; by directly turning to the Scriptures. Opposing monarchy and despotism, Salafis envisioned an Islamic state

An Islamic state is a state that has a form of government based on Islamic law (sharia). As a term, it has been used to describe various historical polities and theories of governance in the Islamic world. As a translation of the Arabic ter ...

based on ''Shura

Shura ( ar, شُورَىٰ, translit=shūrā, lit=consultation) can for example take the form of a council or a referendum. The Quran encourages Muslims to decide their affairs in consultation with each other.

Shura is mentioned as a praisewor ...

'' (consultative system) and guided by qualified ''Ulema

In Islam, the ''ulama'' (; ar, علماء ', singular ', "scholar", literally "the learned ones", also spelled ''ulema''; feminine: ''alimah'' ingularand ''aalimath'' lural are the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious ...

'' (Islamic scholars); whose duty was to uphold the pristine Islam of the '' Salaf al-Salih'' (pious forebears). Salafi scholars stood for decentralisation, demanded more autonomy to Arab provinces and called for the integration of reformist

Reformism is a political doctrine advocating the reform of an existing system or institution instead of its abolition and replacement.

Within the socialist movement, reformism is the view that gradual changes through existing institutions can ...

''Ulema'' to the Syrian political leadership. Both the Salafis and the Ottoman clerical elite were locked in bitter political and religious rivalry throughout the late nineteenth and early 20th centuries, with their fierce polemical feuds often ending in violent clashes. Some of the famous encounters include "''Mujtahid

''Ijtihad'' ( ; ar, اجتهاد ', ; lit. physical or mental ''effort'') is an Islamic legal term referring to independent reasoning by an expert in Islamic law, or the thorough exertion of a jurist's mental faculty in finding a solution to a l ...

s'' incident" of 1896 in which leading Salafi figures like Jamal al-Din Qasimi

Jamal al-Din bin Muhammad Saeed bin Qasim al-Hallaq al-Qasimi (1283 AH / 1866 CE - 1332 AH / 1914 CE) (Arabic: جمال الدين القاسمي), was the organizer of the story of Kalila and Dimna. He was one of the pioneers of the modern sci ...

was put to trial for their claims of ''Ijtihad

''Ijtihad'' ( ; ar, اجتهاد ', ; lit. physical or mental ''effort'') is an Islamic legal term referring to independent reasoning by an expert in Islamic law, or the thorough exertion of a jurist's mental faculty in finding a solution to a l ...

'', a mob attack by supporters of a Sufi Shaykh on Rashid Rida

Muḥammad Rashīd ibn ʿAlī Riḍā ibn Muḥammad Shams al-Dīn ibn Muḥammad Bahāʾ al-Dīn ibn Munlā ʿAlī Khalīfa (23 September 1865 or 18 October 1865 – 22 August 1935 CE/ 1282 - 1354 AH), widely known as Sayyid Rashid Rida ( ar, � ...

at the Umayyad Mosque

The Umayyad Mosque ( ar, الجامع الأموي, al-Jāmiʿ al-Umawī), also known as the Great Mosque of Damascus ( ar, الجامع الدمشق, al-Jāmiʿ al-Damishq), located in the old city of Damascus, the capital of Syria, is one of the ...

in 1908, detention and arrest of Abd al Hamid al-Zahrawi, raids conducted on the homes of various Salafi scholars like Tahir al-Jaza'iri, etc.

Themes

Some themes in modern Islamic thought include: * The acknowledgement "with varying degrees of criticism or emulation", of the technological, scientific and legal achievements of the West; while at the same time objecting "to Western colonial exploitation of Muslim countries and the imposition of Western secular values" and aiming to develop a modern and dynamic understanding of science among Muslims that would strengthen the Muslim world and prevent further exploitation. * Denying that "the Islamic code of law is unalterable and unchangeable", and instead claiming it can "adapt itself to the social and political revolutions going on around it". (Cheragh Ali in 1883) * Invocation of the "objectives" of Islamic law ('' maqasid al-sharia'') in support of "public interest", (or ''maslahah

Maslaha or maslahah ( ar, مصلحة, lit=public interest) is a concept in shari'ah ( Islamic divine law) regarded as a basis of law.I. Doi, Abdul Rahman. (1995). "Mașlahah". In John L. Esposito. ''The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Modern Islamic Wo ...

'', a secondary source for Islamic jurisprudence).Djamil 1995, 60Mausud 2005 This was done by Islamic reformists in "many parts of the globe to justify initiatives not addressed in classical commentaries but regarded as of urgent political and ethical concern."

* Reinterpreting traditional Islamic law using the four traditional sources of Islamic jurisprudence – the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , ...

, the reported deeds and sayings of Muhammad (hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approva ...

), consensus of the theologians (''ijma

''Ijmāʿ'' ( ar, إجماع , " consensus") is an Arabic term referring to the consensus or agreement of the Islamic community on a point of Islamic law. Sunni Muslims regard ''ijmā as one of the secondary sources of Sharia law, after the Qur' ...

'') and juristic reasoning by analogy (''qiyas

In Islamic jurisprudence, qiyas ( ar, قياس , " analogy") is the process of deductive analogy in which the teachings of the hadith are compared and contrasted with those of the Quran, in order to apply a known injunction ('' nass'') to a ...

''), plus another source ''ijtihad

''Ijtihad'' ( ; ar, اجتهاد ', ; lit. physical or mental ''effort'') is an Islamic legal term referring to independent reasoning by an expert in Islamic law, or the thorough exertion of a jurist's mental faculty in finding a solution to a l ...

'' (independent reasoning to find a solution to a legal question).

** Taking and reinterpreting the first two sources (the Quran and ahadith) "to transform the last two ''ijma'' and ''qiyas'')in order to formulate a reformist project in light of the prevailing standards of scientific rationality and modern social theory."

** Restricting traditional Islamic law by limiting its basis to the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , ...

and authentic Sunnah

In Islam, , also spelled ( ar, سنة), are the traditions and practices of the Islamic prophet Muhammad that constitute a model for Muslims to follow. The sunnah is what all the Muslims of Muhammad's time evidently saw and followed and passed ...

, limiting the Sunna with radical hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approva ...

criticism.

**Employing ''ijtihad

''Ijtihad'' ( ; ar, اجتهاد ', ; lit. physical or mental ''effort'') is an Islamic legal term referring to independent reasoning by an expert in Islamic law, or the thorough exertion of a jurist's mental faculty in finding a solution to a l ...

'' not to only in the traditional, narrow way to arrive at legal rulings in unprecedented cases (where Quran, hadith, and rulings of earlier jurists are silent), but for critical independent reasoning in all domains of thought, and perhaps even approving of its use by non-jurists.

* A more or less radical (re)interpretation of the authoritative sources. This is particularly the case with the Quranic verses on polygyny

Polygyny (; from Neoclassical Greek πολυγυνία (); ) is the most common and accepted form of polygamy around the world, entailing the marriage of a man with several women.

Incidence

Polygyny is more widespread in Africa than in any ...

, the '' hadd'' (penal) punishments, ''jihad

Jihad (; ar, جهاد, jihād ) is an Arabic word which literally means "striving" or "struggling", especially with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it can refer to almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with G ...

'', and treatment of unbelievers, banning of usury

Usury () is the practice of making unethical or immoral monetary loans that unfairly enrich the lender. The term may be used in a moral sense—condemning taking advantage of others' misfortunes—or in a legal sense, where an interest rate is c ...

or interest on loans (''riba

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) is a professional body for architects primarily in the United Kingdom, but also internationally, founded for the advancement of architecture under its royal charter granted in 1837, three supp ...

''), which conflict with "modern" views.

**On the topic of Jihad

Jihad (; ar, جهاد, jihād ) is an Arabic word which literally means "striving" or "struggling", especially with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it can refer to almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with G ...

, Islamic scholars like Ibn al-Amir al-San'ani, Muhammad Abduh

; "The Theology of Unity")

, alma_mater = Al-Azhar University

, office1 = Grand Mufti of Egypt

, term1 = 1899 – 1905

, Sufi_order = Shadhiliyya

, disciple_of =

, awards =

, in ...

, Rashid Rida

Muḥammad Rashīd ibn ʿAlī Riḍā ibn Muḥammad Shams al-Dīn ibn Muḥammad Bahāʾ al-Dīn ibn Munlā ʿAlī Khalīfa (23 September 1865 or 18 October 1865 – 22 August 1935 CE/ 1282 - 1354 AH), widely known as Sayyid Rashid Rida ( ar, � ...

, Ubaidullah Sindhi

Maulana Ubaidullah Sindhi (10 March 1872 – 21 August 1944) was a political activist of the Indian independence movement and one of its vigorous leaders. According to ''Dawn'', Karachi, Maulana Ubaidullah Sindhi struggled for the independence ...

, Yusuf al-Qaradawi, Shibli Nomani

Shibli Nomani ( ur, – ; 3 June 1857 – 18 November 1914) was an Islamic scholar from the Indian subcontinent during the British Raj. He was born at Bindwal in Azamgarh district of present-day Uttar Pradesh.Al-Jassas

Al-Jaṣṣās (, 305 AH/917 AD - 370 AH/981 AD; full name ''Abū Bakr Aḥmad ibn ʿAlī al-Rāzī al-Jaṣṣāṣ'') was a Hanafite scholar, Jonathan A.C. Brown (2007), ''The Canonization of al-Bukhārī and Muslim: The Formation and Function ...

, Ibn Taymiyya

Ibn Taymiyyah (January 22, 1263 – September 26, 1328; ar, ابن تيمية), birth name Taqī ad-Dīn ʾAḥmad ibn ʿAbd al-Ḥalīm ibn ʿAbd al-Salām al-Numayrī al-Ḥarrānī ( ar, تقي الدين أحمد بن عبد الحليم � ...

, etc. According to Ibn Taymiyya

Ibn Taymiyyah (January 22, 1263 – September 26, 1328; ar, ابن تيمية), birth name Taqī ad-Dīn ʾAḥmad ibn ʿAbd al-Ḥalīm ibn ʿAbd al-Salām al-Numayrī al-Ḥarrānī ( ar, تقي الدين أحمد بن عبد الحليم � ...

, the reason for Jihad

Jihad (; ar, جهاد, jihād ) is an Arabic word which literally means "striving" or "struggling", especially with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it can refer to almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with G ...

against non-Muslims is not their disbelief, but the threat they pose to Muslims. Citing Ibn Taymiyya

Ibn Taymiyyah (January 22, 1263 – September 26, 1328; ar, ابن تيمية), birth name Taqī ad-Dīn ʾAḥmad ibn ʿAbd al-Ḥalīm ibn ʿAbd al-Salām al-Numayrī al-Ḥarrānī ( ar, تقي الدين أحمد بن عبد الحليم � ...

, scholars like Rashid Rida

Muḥammad Rashīd ibn ʿAlī Riḍā ibn Muḥammad Shams al-Dīn ibn Muḥammad Bahāʾ al-Dīn ibn Munlā ʿAlī Khalīfa (23 September 1865 or 18 October 1865 – 22 August 1935 CE/ 1282 - 1354 AH), widely known as Sayyid Rashid Rida ( ar, � ...

, Al San'ani, Qaradawi

Yusuf al-Qaradawi ( ar, يوسف القرضاوي, translit=Yūsuf al-Qaraḍāwī; or ''Yusuf al-Qardawi''; 9 September 1926 – 26 September 2022) was an Egyptian Islamic scholar based in Doha, Qatar, and chairman of the International Union of ...

, etc. argues that unbelievers need not be fought unless they pose a threat to Muslims. Thus, Jihad is obligatory only as a defensive warfare to respond to aggression or "perfidy" against the Muslim community, and that the "normal and desired state" between Islamic and non-Islamic territories was one of "peaceful coexistence." Similarly the 18th-century Islamic scholar Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhabconversion to Islam

Conversion to Islam is accepting Islam as a religion or faith and rejecting any other religion or irreligion. Requirements

Converting to Islam requires one to declare the '' shahādah'', the Muslim profession of faith ("there is no god but Allah ...

by unbelievers in fear of death at the hands of jihadists (mujahideen

''Mujahideen'', or ''Mujahidin'' ( ar, مُجَاهِدِين, mujāhidīn), is the plural form of ''mujahid'' ( ar, مجاهد, mujāhid, strugglers or strivers or justice, right conduct, Godly rule, etc. doers of jihād), an Arabic term t ...

) was unlikely to prove sincere or lasting. Much preferable means of conversion was education. They pointed to the verse "No compulsion is there in religion"

**On the topic of ''riba

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) is a professional body for architects primarily in the United Kingdom, but also internationally, founded for the advancement of architecture under its royal charter granted in 1837, three supp ...

'', Syed Ahmad Khan

Sir Syed Ahmad Khan KCSI (17 October 1817 – 27 March 1898; also Sayyid Ahmad Khan) was an Indian Muslim reformer, philosopher, and educationist in nineteenth-century British India. Though initially espousing Hindu-Muslim unity, h ...

, Fazlur Rahman Malik, Muhammad Abduh

; "The Theology of Unity")

, alma_mater = Al-Azhar University

, office1 = Grand Mufti of Egypt

, term1 = 1899 – 1905

, Sufi_order = Shadhiliyya

, disciple_of =

, awards =

, in ...

, Rashid Rida

Muḥammad Rashīd ibn ʿAlī Riḍā ibn Muḥammad Shams al-Dīn ibn Muḥammad Bahāʾ al-Dīn ibn Munlā ʿAlī Khalīfa (23 September 1865 or 18 October 1865 – 22 August 1935 CE/ 1282 - 1354 AH), widely known as Sayyid Rashid Rida ( ar, � ...

, Abd El-Razzak El-Sanhuri, Muhammad Asad

Muhammad Asad, ( ar, محمد أسد , ur, , born Leopold Weiss; 2 July 1900 – 20 February 1992) was an Austro-Hungarian-born Pakistani journalist, traveler, writer, linguist, political theorist and diplomat. He was a Jew but, later conve ...

, Mahmoud Shaltout all took issue with the jurist orthodoxy that any and all interest was ''riba'' and forbidden, believing that there was a difference between interest and usury

Usury () is the practice of making unethical or immoral monetary loans that unfairly enrich the lender. The term may be used in a moral sense—condemning taking advantage of others' misfortunes—or in a legal sense, where an interest rate is c ...

. Khan, ''Islamic Banking in Pakistan'', 2015: p. 56 These jurists took precedent for their position from the classical scholar Ibn Taymiyya

Ibn Taymiyyah (January 22, 1263 – September 26, 1328; ar, ابن تيمية), birth name Taqī ad-Dīn ʾAḥmad ibn ʿAbd al-Ḥalīm ibn ʿAbd al-Salām al-Numayrī al-Ḥarrānī ( ar, تقي الدين أحمد بن عبد الحليم � ...

who argued in his treatise "The Removal of Blames from the Great Imams", that scholars are divided on the prohibition of ''riba al-fadl''. Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya, the student of Ibn Taymiyya, also distinguished between ''riba al-nasi'ah'' and ''riba al-fadl'', maintaining that only ''rib al-nasi'ah'' was prohibited by ''Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , si ...

'' and ''Sunnah

In Islam, , also spelled ( ar, سنة), are the traditions and practices of the Islamic prophet Muhammad that constitute a model for Muslims to follow. The sunnah is what all the Muslims of Muhammad's time evidently saw and followed and passed ...

'' definitively while the latter was only prohibited in order to stop the charging of interest. According to him, the prohibition of ''riba al-fadl'' was less severe and it could be allowed in dire need or greater public interest (''maslaha

Maslaha or maslahah ( ar, مصلحة, lit=public interest) is a concept in shari'ah ( Islamic divine law) regarded as a basis of law.I. Doi, Abdul Rahman. (1995). "Mașlahah". In John L. Esposito. ''The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Modern Islamic W ...

''). Hence under a compelling need, an item may be sold with delay in return for dirhams or for another weighed substance despite implicating ''riba al-nasi'ah''.

* An apologetic which links aspects of the Islamic tradition with Western ideas and practices, and claims Western practices in question were originally derived from Islam. Islamic apologetics has however been severely criticized by many scholars as superficial, tendentious and even psychologically destructive, so much so that the term "apologetics" has almost become a term of abuse in the literature on modern Islam.

History of Modernism

Origins

Islamic modernist discourse emerged as an intellectual movement in the second quarter of nineteenth century; during an era of wide-ranging reforms initiated across the

Islamic modernist discourse emerged as an intellectual movement in the second quarter of nineteenth century; during an era of wide-ranging reforms initiated across the Ottoman empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

known as the Tanzimat

The Tanzimat (; ota, تنظيمات, translit=Tanzimāt, lit=Reorganization, ''see'' nizām) was a period of reform in the Ottoman Empire that began with the Gülhane Hatt-ı Şerif in 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 187 ...

(1839–1876 C.E). The movement sought to harmonise classical Islamic theological concepts with liberal constitutional

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these prin ...

ideas and advocated the reformulation of religious values in light of drastic social, political and technological changes. Intellectuals like Namik Kemal (1840–1888 C.E) called for popular sovereignty and "natural rights

Some philosophers distinguish two types of rights, natural rights and legal rights.

* Natural rights are those that are not dependent on the laws or customs of any particular culture or government, and so are ''universal'', '' fundamental'' an ...

" of citizens. Major scholarly figures of this movement included the Grand Imam of al-Azhar Hassan al-Attar (d. 1835), Ottoman Vizier Mehmed Emin Âli Pasha

Mehmed Emin Âli Pasha, also spelled as Mehmed Emin Aali (March 5, 1815 – September 7, 1871) was a prominent Ottoman statesman during the Tanzimat period, best known as the architect of the Ottoman Reform Edict of 1856, and for his role in ...

(d. 1871), South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The region consists of the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.;;;;; ...

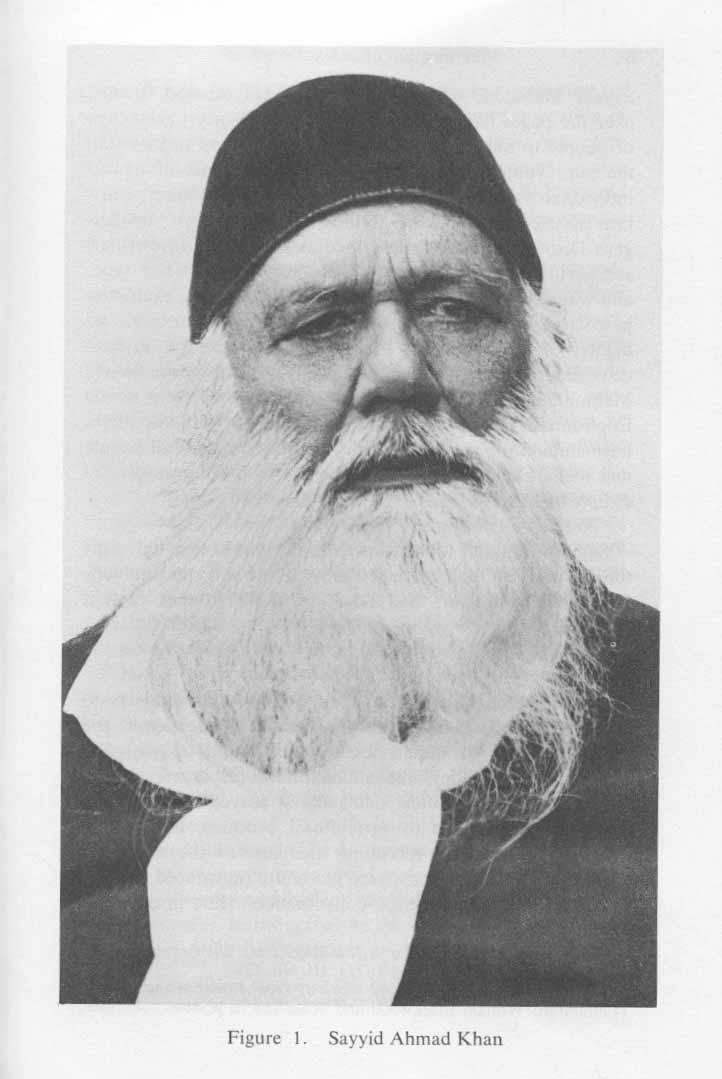

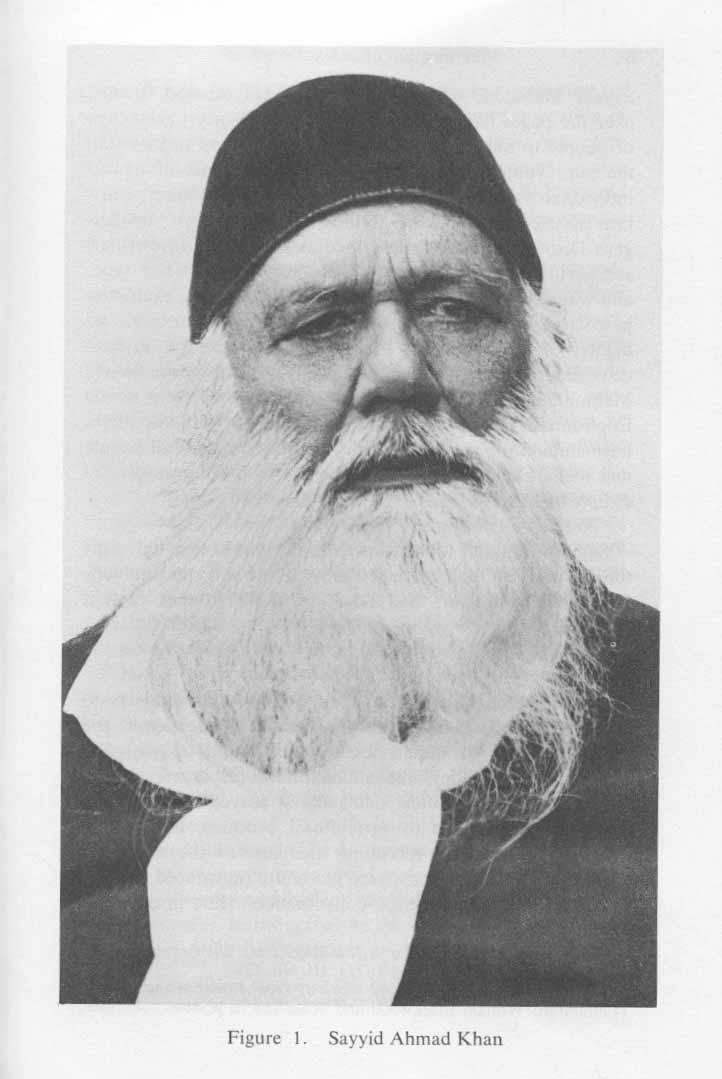

n philosopher Sayyid Ahmad Khan

Sir Syed Ahmad Khan KCSI (17 October 1817 – 27 March 1898; also Sayyid Ahmad Khan) was an Indian Muslim reformer, philosopher, and educationist in nineteenth-century British India. Though initially espousing Hindu-Muslim unity, he ...

(d. 1898), Jamal al-Din Afghani (d. 1897), etc. Inspired by their understanding of classical Islamic thought, these rationalist scholars regarded Islam as a religion compatible with Western philosophy

Western philosophy encompasses the philosophy, philosophical thought and work of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the Pre-Socratic p ...

and modern science

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal.

Science's earliest roots can be traced to Ancient Egypt and Mesop ...

. Eventually the modernist intellectuals formed a secret society known as ''Ittıfak-ı Hamiyet'' (Patriotic Alliance) in 1865; which advocated political liberalism and modern constitutionalist ideals of popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the authority of a state and its government are created and sustained by the consent of its people, who are the source of all political power. Popular sovereignty, being a principle, does not imply any ...

through religious discourse. During this era, numerous intellectuals and social activists like Muhammad Iqbal (1877-1938 C.E), Egyptian Nahda figure Rifaa al-Tahtawi (1801-1873), etc. introduced Western ideological themes and ethical notions into local Muslim communities and religious seminaries.Spread

The theological views of the Azharite scholar Muhammad 'Abduh (d. 1905) were greatly shaped by the 19th century Ottoman intellectual discourse. Similar to the early Ottoman modernists, Abduh tried to bridge the gap between Enlightenment ideals and traditional religious values. He believed that classical Islamic theology was intellectually vigorous and portrayed ''

The theological views of the Azharite scholar Muhammad 'Abduh (d. 1905) were greatly shaped by the 19th century Ottoman intellectual discourse. Similar to the early Ottoman modernists, Abduh tried to bridge the gap between Enlightenment ideals and traditional religious values. He believed that classical Islamic theology was intellectually vigorous and portrayed ''Kalam

''ʿIlm al-Kalām'' ( ar, عِلْم الكَلام, literally "science of discourse"), usually foreshortened to ''Kalām'' and sometimes called "Islamic scholastic theology" or "speculative theology", is the philosophical study of Islamic doc ...

'' (speculative theology) as a logical methodology that demonstrated the rational spirit and vitality of Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

. Key themes of modernists would eventually be adopted by the Ottoman clerical elite who underpinned liberty as a basic Islamic principle. Portraying Islam as a religion that exemplified national development, human societal progress and evolution; Ottoman Shaykh al-Islam Musa Kazim Efendi (d. 1920) wrote in his article "Islam and Progress" published in 1904:"the religion of Islam is not an obstacle to progress. On the contrary, it is that which commands and encourages progress; it is the very reason for progress itself"

Commencing in the late nineteenth century and impacting the twentieth-century, Muhammed Abduh and his followers undertook an educational and social project to defend, modernize and revitalize Islam to match Western institutions and social processes. Its most prominent intellectual founder,

Commencing in the late nineteenth century and impacting the twentieth-century, Muhammed Abduh and his followers undertook an educational and social project to defend, modernize and revitalize Islam to match Western institutions and social processes. Its most prominent intellectual founder, Muhammad Abduh

; "The Theology of Unity")

, alma_mater = Al-Azhar University

, office1 = Grand Mufti of Egypt

, term1 = 1899 – 1905

, Sufi_order = Shadhiliyya

, disciple_of =

, awards =

, in ...

(d. 1323 AH/1905 CE), was Sheikh of Al-Azhar University

, image = جامعة_الأزهر_بالقاهرة.jpg

, image_size = 250

, caption = Al-Azhar University portal

, motto =

, established =

*970/972 first foundat ...

for a brief period before his death. This project superimposed the world of the nineteenth century on the extensive body of Islamic knowledge that had accumulated in a different milieu. These efforts had little impact at first. After Abduh's death, his movement was catalysed by the demise of the Ottoman Caliphate in 1924 and promotion of secular liberalism – particularly with a new breed of writers being pushed to the fore including Egyptian Ali Abd al-Raziq's publication attacking Islamic politics for the first time in Muslim history. Subsequent secular writers of this trend including Farag Foda

Farag Foda or Fouda ( ar, فرج فودة ; 20 August 1945 – 8 June 1992) was a prominent Egyptian professor, writer, columnist, and human rights activist.

He was assassinated on 8 June 1992 by members of the Islamist group El Gama'a El Isl ...

, al-Ashmawi, Muhamed Khalafallah, Taha Husayn, Husayn Amin, et al., have argued in similar tones.

Abduh was skeptical towards many Hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approva ...

(or "Traditions"), i.e. towards the body of reports of the teachings, doings, and sayings of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Particularly towards those Traditions that are reported through few chains of transmission, even if they are deemed rigorously authenticated in any of the six canonical books of Hadith (known as the Kutub al-Sittah). Furthermore, he advocated a reassessment of traditional assumptions even in Hadith studies, though he did not devise a systematic methodology before his death.The Modernist Approach to Hadith StudiesBy Noor al-Deen Atabek, onislam.net, 30 March 2005

Ibn Ashur's ''Maqasid al-Sharia''

TunisianMaliki

The ( ar, مَالِكِي) school is one of the four major schools of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was founded by Malik ibn Anas in the 8th century. The Maliki school of jurisprudence relies on the Quran and hadiths as prima ...

scholar Muhammad al-Tahir ibn Ashur (1879-1973 C.E) who rose to the position of chief judge at Zaytuna university was a major student of Muhammad 'Abduh. He met 'Abduh in 1903 during his visit to Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

and thereafter became a passionate advocate of 'Abduh's modernist vision. He called for a revamping of the educational curriculum and became noteworthy for his role in revitalising the discourse of ''Maqasid al-Sharia'' (Higher Objectives of Islamic Law) in scholarly and intellectual ciricles. Ibn Ashur authored the book "''Maqasid al-Shari'ah al-Islamiyyah''" in 1946 which was widely accepted by modernist intellectuals and writers. In his treatise, Ibn Ashur called for a legal theory that is flexible towards 'urf (local customs) and adopted contextualised approach towards re-interpretation of hadiths based on applying the principle of ''Maqasid'' (objectives).

Decline

After its peak during the early 20th century, the modernist movement would gradually decline after theDissolution of the Ottoman Empire

The dissolution of the Ottoman Empire (1908–1922) began with the Young Turk Revolution which restored the constitution of 1876 and brought in multi-party politics with a two-stage electoral system for the Ottoman parliament. At the same t ...

in the 1920s and eventually lost ground to conservative reform movements such as Salafism

The Salafi movement or Salafism () is a reform branch movement within Sunni Islam that originated during the nineteenth century. The name refers to advocacy of a return to the traditions of the "pious predecessors" (), the first three generat ...

. From 1919, Western Oriental scholar

Oriental studies is the academic field that studies Near Eastern and Far Eastern societies and cultures, languages, peoples, history and archaeology. In recent years, the subject has often been turned into the newer terms of Middle Eastern studie ...

s like Louis Massignon began categorising broad swathes of scripture-oriented rationalist scholars and modernists as part of the paradigm of "''Salafiyya

The Salafi movement or Salafism () is a reform branch movement within Sunni Islam that originated during the nineteenth century. The name refers to advocacy of a return to the traditions of the "pious predecessors" (), the first three generat ...

''"; a theological term which was erroneously perceived as a "reformist slogan".Robert Rabil ''Salafism in Lebanon: From Apoliticism to Transnational Jihadism'' Georgetown University Press

Georgetown University Press is a university press affiliated with Georgetown University that publishes about forty new books a year. The press's major subject areas include bioethics, international affairs, languages and linguistics, political s ...

2014 chapter: "Doctrine" Following the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, Western colonialism of Muslim lands and the advancement of secularist trends; Islamic reformers felt betrayed by the Arab nationalists and underwent a crisis. This schism was epitomised by the ideological transformation of Sayyid Rashid Rida, a pupil of 'Abduh, who began to resuscitate the treatises of Hanbali theologian Ibn Taymiyyah

Ibn Taymiyyah (January 22, 1263 – September 26, 1328; ar, ابن تيمية), birth name Taqī ad-Dīn ʾAḥmad ibn ʿAbd al-Ḥalīm ibn ʿAbd al-Salām al-Numayrī al-Ḥarrānī ( ar, تقي الدين أحمد بن عبد الحليم � ...

and became the "forerunner of Islamist thought" by popularising his ideals. Unlike 'Abduh and Afghani, Rida and his disciples susbcribed to the Hanbali theology. They would openly campaign against adherents of other schools, like the Shi'ites, who were critical of Wahhabi

Wahhabism ( ar, ٱلْوَهَّابِيَةُ, translit=al-Wahhābiyyah) is a Sunni Islamic revivalist and fundamentalist movement associated with the reformist doctrines of the 18th-century Arabian Islamic scholar, theologian, preacher, an ...

doctrines. Rida transformed the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

into a puritanical movement that advanced Muslim identitarianism, pan-Islamism

Pan-Islamism ( ar, الوحدة الإسلامية) is a political movement advocating the unity of Muslims under one Islamic country or state – often a caliphate – or an international organization with Islamic principles. Pan-Islamism wa ...

and preached the superiority of Islamic culture

Islamic culture and Muslim culture refer to cultural practices which are common to historically Islamic people. The early forms of Muslim culture, from the Rashidun Caliphate to the early Umayyad period and the early Abbasid period, were predom ...

while attacking Westernisation

Westernization (or Westernisation), also Europeanisation or occidentalization (from the '' Occident''), is a process whereby societies come under or adopt Western culture in areas such as industry, technology, science, education, politics, eco ...

. One of the major hallmarks of Rida's movement was his advocacy of a theological doctrine that obligated the establishment of an Islamic state

An Islamic state is a state that has a form of government based on Islamic law (sharia). As a term, it has been used to describe various historical polities and theories of governance in the Islamic world. As a translation of the Arabic ter ...

led by the ''Ulema

In Islam, the ''ulama'' (; ar, علماء ', singular ', "scholar", literally "the learned ones", also spelled ''ulema''; feminine: ''alimah'' ingularand ''aalimath'' lural are the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious ...

'' (Islamic scholars).

Rida's fundamentalist

Fundamentalism is a tendency among certain groups and individuals that is characterized by the application of a strict literal interpretation to scriptures, dogmas, or ideologies, along with a strong belief in the importance of distinguishi ...

doctrines would later be adopted by Islamic scholars and Islamist movements like the Muslim Brotherhood

The Society of the Muslim Brothers ( ar, جماعة الإخوان المسلمين'' ''), better known as the Muslim Brotherhood ( '), is a transnational Sunni Islamist organization founded in Egypt by Islamic studies, Islamic scholar and scho ...

. According to the German scholar Bassam Tibi

Bassam Tibi ( ar, بسام طيبي), is a Syrian-born German political scientist and professor of international relations specializing in Islamic studies and Middle Eastern studies. He was born in 1944 in Damascus, Syria to an aristocratic famil ...

:"Rida's Islamic fundamentalism has been taken up by the Muslim Brethren, a right wing radical movement founded in 1928, which has ever since been in inexorable opposition to secular nationalism."

Contemporary Era

Contemporary Muslim modernism is charactarised by its emphasis on the doctrine of "''Maqasid al-sharia''" to navigate the currents of modernity and address issues related to international human rights. Another aspect is its promotion of ''Fiqh al-Aqalliyat'' (minority jurisprudence) during the late 20th century to answer the challenges facing the growing Muslim minority populations in theWest

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some ...

. Islamic scholar Abdullah Bin Bayyah, professor

Professor (commonly abbreviated as Prof.) is an academic rank at universities and other post-secondary education and research institutions in most countries. Literally, ''professor'' derives from Latin as a "person who professes". Professo ...

of Islamic studies

Islamic studies refers to the academic study of Islam, and generally to academic multidisciplinary "studies" programs—programs similar to others that focus on the history, texts and theologies of other religious traditions, such as Easter ...

at King Abdul Aziz University

King Abdulaziz University (KAU) ( ar, جامعة الملك عبد العزيز) is a public university in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. With over 117,096 students in 2022, it is the largest university in the country. Located in south Jeddah, the univ ...

in Jiddah

Jeddah ( ), also spelled Jedda, Jiddah or Jidda ( ; ar, , Jidda, ), is a city in the Hejaz region of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) and the country's commercial center. Established in the 6th century BC as a fishing village, Jeddah's promi ...

, is one of the major proponents of ''Fiqh al-Aqalliyat'' and advocates remodelling the legal system based on the principles of ''Maqasid al-Sharia'' to suit the sensitivities of the modern era.

Influence on Revivalist movements

Muslim Brotherhood

Islamist movements likeMuslim Brotherhood

The Society of the Muslim Brothers ( ar, جماعة الإخوان المسلمين'' ''), better known as the Muslim Brotherhood ( '), is a transnational Sunni Islamist organization founded in Egypt by Islamic studies, Islamic scholar and scho ...

(''al-Ikhwān al-Muslimūn'') were highly influenced by both Islamic Modernism and Salafism

The Salafi movement or Salafism () is a reform branch movement within Sunni Islam that originated during the nineteenth century. The name refers to advocacy of a return to the traditions of the "pious predecessors" (), the first three generat ...

. Its founder Hassan Al-Banna

Sheikh Hassan Ahmed Abdel Rahman Muhammed al-Banna ( ar, حسن أحمد عبد الرحمن محمد البنا; 14 October 1906 – 12 February 1949), known as Hassan al-Banna ( ar, حسن البنا), was an Egyptian schoolteacher and imam, b ...

was influenced by Muhammad Abduh

; "The Theology of Unity")

, alma_mater = Al-Azhar University

, office1 = Grand Mufti of Egypt

, term1 = 1899 – 1905

, Sufi_order = Shadhiliyya

, disciple_of =

, awards =

, in ...

and his Salafi student Rashid Rida

Muḥammad Rashīd ibn ʿAlī Riḍā ibn Muḥammad Shams al-Dīn ibn Muḥammad Bahāʾ al-Dīn ibn Munlā ʿAlī Khalīfa (23 September 1865 or 18 October 1865 – 22 August 1935 CE/ 1282 - 1354 AH), widely known as Sayyid Rashid Rida ( ar, � ...

. Al-Banna attacked the ''taqlid'' of the official ''ulama'' and insisted only the Qur'an and the best-attested ''ahadith'' should be sources of the ''Sharia''. However, it was the Syrian Salafi scholar Rashid Rida who influenced Al-Banna the most. He was a dedicated reader of the writings of Rashid Rida

Muḥammad Rashīd ibn ʿAlī Riḍā ibn Muḥammad Shams al-Dīn ibn Muḥammad Bahāʾ al-Dīn ibn Munlā ʿAlī Khalīfa (23 September 1865 or 18 October 1865 – 22 August 1935 CE/ 1282 - 1354 AH), widely known as Sayyid Rashid Rida ( ar, � ...

and the magazine that Rida published, '' Al-Manar''. Sharing Rida's central concern with the decline of Islamic civilization, Al-Banna too believed that this trend could be reversed only by returning to a pure, unadulterated form of Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

. Like Rida, (and unlike the Islamic modernists) Al-Banna viewed Western secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin ''saeculum'', "worldly" or "of a generation"), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Anything that does not have an explicit reference to religion, either negativ ...

ideas as the main danger to Islam in the modern age. As Islamic Modernist

Islamic modernism is a movement that has been described as "the first Muslim ideological response to the Western cultural challenge" attempting to reconcile the Islamic faith with modern values such as democracy, civil rights, rationality, ...

beliefs were co-opted by secularist rulers and official ''`ulama'', the Brotherhood moved in a traditionalist and conservative direction, "being the only available outlet for those whose religious and cultural sensibilities had been outraged by the impact of Westernisation

Westernization (or Westernisation), also Europeanisation or occidentalization (from the '' Occident''), is a process whereby societies come under or adopt Western culture in areas such as industry, technology, science, education, politics, eco ...

". The Brotherhood argued for a Salafist solution to the contemporary challenges faced by the Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

, advocating the establishment of an Islamic state

An Islamic state is a state that has a form of government based on Islamic law (sharia). As a term, it has been used to describe various historical polities and theories of governance in the Islamic world. As a translation of the Arabic ter ...

through implementation of the ''Shari'ah

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and th ...

'', based on Salafi revivalism.

Although the Muslim Brotherhood officially describes itself as a Salafi movement, the Quietist Salafis often contest their Salafist credentials. The Brotherhood differs from the Purists in their strategy for combating the challenge of modernity, and is focused on gaining control of the government. Despite this, both the Brotherhood and Salafists advocate the implementation of ''sharia

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

'' and emphasizes strict doctrinal adherence to the teachings of Prophet Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monoth ...

and the ''Salaf, Salaf al-Salih''.

The Salafi movement#Salafi activists, Salafi-Activists who have a long tradition of political involvement; are highly active in Islamist movements like the Muslim Brotherhood

The Society of the Muslim Brothers ( ar, جماعة الإخوان المسلمين'' ''), better known as the Muslim Brotherhood ( '), is a transnational Sunni Islamist organization founded in Egypt by Islamic studies, Islamic scholar and scho ...

and its various branches and affiliates. According to the Brotherhood affiliated former President of Egypt, Egyptian President Mohammed Morsi:"the Koran is our constitution, the Prophet Muhammad is our leader, jihad is our path, and death for the sake of Allah is our most lofty aspiration...sharia, sharia, and then finally sharia. This nation will enjoy blessing and revival only through the Islamic sharia."

Muhammadiyah

The Indonesian Islamic organization Muhammadiyah was founded in 1912. Often Described as Salafist, and sometimes as Islamic Modernist, it emphasized the authority of the ''Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , si ...

'' and the ''Hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approva ...

s'', opposing syncretism and ''taqlid

''Taqlid'' (Arabic تَقْليد ''taqlīd'') is an Islamic term denoting the conformity of one person to the teaching of another. The person who performs ''taqlid'' is termed ''muqallid''. The definite meaning of the term varies depending on con ...

'' (blind-conformity) to the ulema. As of 2006, it is said to have "veered sharply toward a more conservative brand of Islam" under the leadership of Din Syamsuddin, the head of the Indonesian Ulema Council.

Salafiyya Movement

Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, Jamal Al-Din al-Afghani, Muhammad 'Abduh, Muhammad al-Tahir ibn Ashur,Syed Ahmad Khan

Sir Syed Ahmad Khan KCSI (17 October 1817 – 27 March 1898; also Sayyid Ahmad Khan) was an Indian Muslim reformer, philosopher, and educationist in nineteenth-century British India. Though initially espousing Hindu-Muslim unity, h ...

and, to a lesser extent, Mohammed al-Ghazali took some ideals of Wahhabism

Wahhabism ( ar, ٱلْوَهَّابِيَةُ, translit=al-Wahhābiyyah) is a Sunni Islamic revivalist and fundamentalist movement associated with the reformist doctrines of the 18th-century Arabian Islamic scholar, theologian, preacher, and ...

, such as endeavor to "return" to the Islamic understanding of the first Muslim generations (Salaf) by reopening the doors of juristic deduction (''ijtihad

''Ijtihad'' ( ; ar, اجتهاد ', ; lit. physical or mental ''effort'') is an Islamic legal term referring to independent reasoning by an expert in Islamic law, or the thorough exertion of a jurist's mental faculty in finding a solution to a l ...

'') that they saw as closed. Some historians believe modernists used the term "''Salafiyya''" for their movement (although this is strongly disputed by at least one scholar – Henri Lauzière). American scholar Nuh Ha Mim Keller writes:

The term ''Salafi'' was revived as a slogan and movement, among latter-day Muslims, by the followers of Muhammad Abduh.

In popular Western discourse during the early twentieth century; the term "''

Salafiyya

The Salafi movement or Salafism () is a reform branch movement within Sunni Islam that originated during the nineteenth century. The name refers to advocacy of a return to the traditions of the "pious predecessors" (), the first three generat ...

''" stood for a wide range of revivalist, reformist and rationalist movements in the Arab world, Arab World that sought a reconciliation of Islamic faith with various aspects modernity. The rise of pan-Islamism

Pan-Islamism ( ar, الوحدة الإسلامية) is a political movement advocating the unity of Muslims under one Islamic country or state – often a caliphate – or an international organization with Islamic principles. Pan-Islamism wa ...

across the Muslim world, Muslim World after the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

and the Dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, collapse of the Ottoman empire, would herald the emergence of Salafi religious purism that fervently opposed Modernism, modernist trends. The anti-colonial struggle to restore the ''Worldwide caliphate, Khilafah'' would become the top priority; manifesting in the formation of the Muslim Brotherhood

The Society of the Muslim Brothers ( ar, جماعة الإخوان المسلمين'' ''), better known as the Muslim Brotherhood ( '), is a transnational Sunni Islamist organization founded in Egypt by Islamic studies, Islamic scholar and scho ...

, a revolutionary movement established in 1928 by the Egyptian school teacher Hassan al-Banna. Backed by the Wahhabi

Wahhabism ( ar, ٱلْوَهَّابِيَةُ, translit=al-Wahhābiyyah) is a Sunni Islamic revivalist and fundamentalist movement associated with the reformist doctrines of the 18th-century Arabian Islamic scholar, theologian, preacher, an ...

clerical elites of Saudi Arabia, Salafis who advocated pan-Islamism and religious conservatism across the Muslim World emerged dominant and gradually replaced the modernists during the Decolonization, decolonisation period. According to Abu Ammaar Yasir Qadhi:Rashid Rida popularized the term 'Salafī' to describe a particular movement that he spearheaded. That movement sought to reject the ossification of the madhhabs, and rethink through the standard issues of fiqh and modernity, at times in very liberal ways. A young scholar by the name of Muhammad Nasiruddin al-Albani read an article by Rida, and then took this term and used it to describe another, completely different movement. Ironically, the movement that Rida spearheaded eventually became Modernist Islam and dropped the 'Salafī' label, and the legal methodology that al-Albānī championed – with a very minimal overlap with Rida's vision of Islam – retained the appellation 'Salafī'. Eventually, al-Albānī's label was adopted by the Najdī daʿwah as well, until it spread in all trends of the movement. Otherwise, before this century, the term 'Salafī' was not used as a common label and proper noun. Therefore, the term 'Salafī' has attached itself to an age-old school of theology, the Atharī school.

Historian Henri Lauzière asserts that modernist intellectuals like Abduh and Afghani had not identified their movement with "''Salafiyya''". On the other hand, Islamic revivalists like :ar:محمود شكري الآلوسي, Mahmud Shukri Al-Alusi (1856–1924 C.E), Rashid Rida, Muhammad Rashid Rida (1865–1935 C.E), Jamal al-Din Qasimi, Jamal al-Din al-Qasimi (1866–1914 C.E), etc. used "''Salafiyya''" as a term primarily to denote the traditionalist Sunni theology, Traditionalist theology (Islam), Atharism. Rida also regarded the

Wahhabi

Wahhabism ( ar, ٱلْوَهَّابِيَةُ, translit=al-Wahhābiyyah) is a Sunni Islamic revivalist and fundamentalist movement associated with the reformist doctrines of the 18th-century Arabian Islamic scholar, theologian, preacher, an ...

movement as part of the ''Salafiyya'' trend. Apart from the Wahhabis of Najd, Athari theology could also be traced back to the Alusi family in Iraq, ''Ahl-i Hadith

Ahl-i Hadith or Ahl-e-Hadith ( bn, আহলে হাদীছ, hi, एहले हदीस, ur, اہلِ حدیث, ''people of hadith'') is a Salafi reform movement that emerged in North India in the mid-nineteenth century from the teac ...

'' in India, and scholars such as Rashid Rida in Egypt. After 1905, Rida steered his reformist programme towards the path of fundamentalist

Fundamentalism is a tendency among certain groups and individuals that is characterized by the application of a strict literal interpretation to scriptures, dogmas, or ideologies, along with a strong belief in the importance of distinguishi ...

counter-reformation. This tendency led by Rida emphasized following the ''Salaf, salaf al-salih'' (pious predecessors) and became known as the ''Salafiyya'' movement, which advocated a re-generation of pristine religious teachings of the early Muslim community. The propagation of the flawed (yet once conventional) notion in the Western scholarship, wherein the Islamic modernist movement of 'Abduh and Afghani was equated with ''Salafiyya'' is first attributed to the French intellectual Louis Massignon.

The progressive views of the early modernists Afghani and Abduh were soon replaced by the puritan Athari tradition espoused by their students; which zealously denounced the ideas of Kuffar, non-Muslims and secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin ''saeculum'', "worldly" or "of a generation"), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Anything that does not have an explicit reference to religion, either negativ ...

ideologies like liberalism. This theological transformation was led by Syed Rashid Rida who adopted the strict Athari creedal doctrines of Ibn Taymiyyah

Ibn Taymiyyah (January 22, 1263 – September 26, 1328; ar, ابن تيمية), birth name Taqī ad-Dīn ʾAḥmad ibn ʿAbd al-Ḥalīm ibn ʿAbd al-Salām al-Numayrī al-Ḥarrānī ( ar, تقي الدين أحمد بن عبد الحليم � ...

during the early twentieth century. The ''Salafiyya'' movement popularised by Rida would advocate for an Athari-Wahhabi

Wahhabism ( ar, ٱلْوَهَّابِيَةُ, translit=al-Wahhābiyyah) is a Sunni Islamic revivalist and fundamentalist movement associated with the reformist doctrines of the 18th-century Arabian Islamic scholar, theologian, preacher, an ...

theology. Their promotion of ''Ijtihad'' was based on referring back to a strictly textual methodology. Its traditionalist vision was adopted by the Wahhabi clerical establishment and championed by influential figures such as the Syrians, Syrian-Albanians, Albanian Hadith scholar Muhammad Nasiruddin al-Albani (d. 1999 C.E/ 1420 A.H).

As a scholarly movement, "Enlightened Salafism" had begun declining some time after the death of Muhammad ʿAbduh in 1905. The Puritanical stances of Rashid Rida, accelerated by his support to the Wahhabi movement; transformed ''Salafiyya

The Salafi movement or Salafism () is a reform branch movement within Sunni Islam that originated during the nineteenth century. The name refers to advocacy of a return to the traditions of the "pious predecessors" (), the first three generat ...

'' movement incrementally and became commonly regarded as "traditional Salafism". The divisions between "Enlightened Salafis" inspired by ʿAbduh, and traditional Salafis represented by Rashid Rida and his disciples would eventually exacerbate. Gradually, the modernist Salafis became totally disassociated from the "Salafi" label in popular discourse and would identify as ''tanwiris'' (enlightened) or Islamic modernists.

Islamic modernists

Although not all of the figures named below are from the above-mentioned movement, they all share a more or less modernist thought or/and approach. *Muhammad Abduh

; "The Theology of Unity")

, alma_mater = Al-Azhar University

, office1 = Grand Mufti of Egypt

, term1 = 1899 – 1905

, Sufi_order = Shadhiliyya

, disciple_of =

, awards =

, in ...

(Egypt)

* Jamal al-Din al-Afghani (Afghanistan or Persia/Iran)

* Mohammed al-Ghazali (Egypt)

* Muhammad al-Tahir ibn Ashur (Tunisia)

* Chiragh Ali (British India)

* Syed Ameer Ali (British India)

* Qasim Amin (Egypt)

* Malek Bennabi (Algeria)

* Musa Bigiev, Musa Jarullah Bigeev (Russia)

* Ahmad Dahlan (Indonesia)

* Farag Foda, Farag Fawda (neomodernist) (Egypt)

* Abdulrauf Fitrat (Uzbekistan, then Russia)

* Muhammad Iqbal

Sir Muhammad Iqbal ( ur, ; 9 November 187721 April 1938), was a South Asian Muslim writer, philosopher, Quote: "In Persian, ... he published six volumes of mainly long poems between 1915 and 1936, ... more or less complete works on philos ...

(British India)

* Wang Jingzhai (China)

* Muhammad Ahmad Khalafallah (Egypt)

* Syed Ahmad Khan

Sir Syed Ahmad Khan KCSI (17 October 1817 – 27 March 1898; also Sayyid Ahmad Khan) was an Indian Muslim reformer, philosopher, and educationist in nineteenth-century British India. Though initially espousing Hindu-Muslim unity, h ...

(British India)

* Shibli Nomani

Shibli Nomani ( ur, – ; 3 June 1857 – 18 November 1914) was an Islamic scholar from the Indian subcontinent during the British Raj. He was born at Bindwal in Azamgarh district of present-day Uttar Pradesh.

* Ghabdennasir Qursawi, Ğäbdennasír İbrahim ulı Qursawí (Russia)

* Mahmoud Shaltout (Egypt)

* Ali Shariati (Iran)

* Mahmoud Mohammed Taha (neomodernist) (Sudan)

* Rifa'a al-Tahtawi (Egypt)

* Mahmud Tarzi (Afghanistan)

Robert Pigott, Religious affairs correspondent, BBC News, 26 February 2008 Turkey has also trained the women as the theologians, and sent them as the senior Imam, imams known as 'vaizes' all over the country, to explain these re-interpretations.

Contemporary Modernists

* Khaled Abou El Fadl (United States) * Gamal al-Banna (Egypt) * Soheib Bencheikh (France) * Abdennour Bidar (France) * Javed Ahmad Ghamidi (Pakistan) * Fethullah Gülen (Turkey) * Taha Hussein (Egypt) * Wahiduddin Khan (India) * Irshad Manji (Canada) * Abdelwahab Meddeb (France) Céline Zünd, Emmanuel Gehrig et Olivier Perrin, "Dans le Coran, sur 6300 versets, cinq contiennent un appel à tuer", ''Le Temps'', 29 January 2015, pp. 10-11. * Mahmoud Mohammed Taha (Sudan) * Ebrahim Moosa (South Africa) * Tariq Ramadan (Switzerland) * Muhammad Tahir-ul-Qadri (Pakistan) * Amina Wadud (United States) *Mahathir MuhammadContemporary use

Turkey

Turkey has reconcile the Islamic faith with modernism. in 2008, its state directorate of religious affairs (Diyanet) launched the review of all the Hadith, hadiths, the sayings of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. The school of theology at Ankara University undertook this forensic examination with the aim of removing the centuries-old conservative cultural burden and rediscovering the spirit of reason in the original message of Islam. Fadi Hakura of Chatham House in London supported these revisions to the Reformation that occurred in Protestant Christianity in the 16th century."Turkey in radical revision of Islamic texts"Robert Pigott, Religious affairs correspondent, BBC News, 26 February 2008 Turkey has also trained the women as the theologians, and sent them as the senior Imam, imams known as 'vaizes' all over the country, to explain these re-interpretations.

Pakistan

According to at least one source (Charles Kennedy), in Pakistan the range of views on the "appropriate role of Islam" in that country (as of 1992), contains "Islamic Modernists" at one end of the spectrum and "Islamic activists" at the other. "Islamic activists" support the expansion of "Islamic law and Islamic practices", "Islamic Modernists" are lukewarm to this expansion and "some may even advocate development along the secularist lines of the West."Criticism

Many orthodox, fundamentalist, and traditionalist Muslims strongly opposed modernism as ''bid'ah'' and the most dangerous heresy of the day, for its association with Westernization and Western education, whereas other orthodox/traditionalist Muslims, even some orthodox Muslim scholars think that modernisation of Islamic law is not violating the principles of ''fiqh'' and it is a form of going back to the Qur'an and the Sunnah. Supporters of Salafi movement considered modernists Neo-Mu'tazila, after the medieval Islamic school of theology based on rationalism, Mu'tazila. Critics argue that the modernist thought is little more than the fusion of Western Secularism with spiritual aspects of Islam. Other critics have described the modernist positions on politics in Islam as ideological stances. One of the leading Islamist thinkers and Islamic revivalists, Abul A'la Maududi agreed with Islamic modernists that Islam contained nothing contrary to reason, and was superior in rational terms to all other religious systems. However he disagreed with them in their examination of the Quran and the Sunna using reason as the standard. Maududi, instead started from the proposition that "true reason is Islamic", and accepted the Book and the Sunna, not reason, as the final authority. Modernists erred in examining rather than simply obeying theQuran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , ...

and the Sunna.