Isaac Isaacs on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

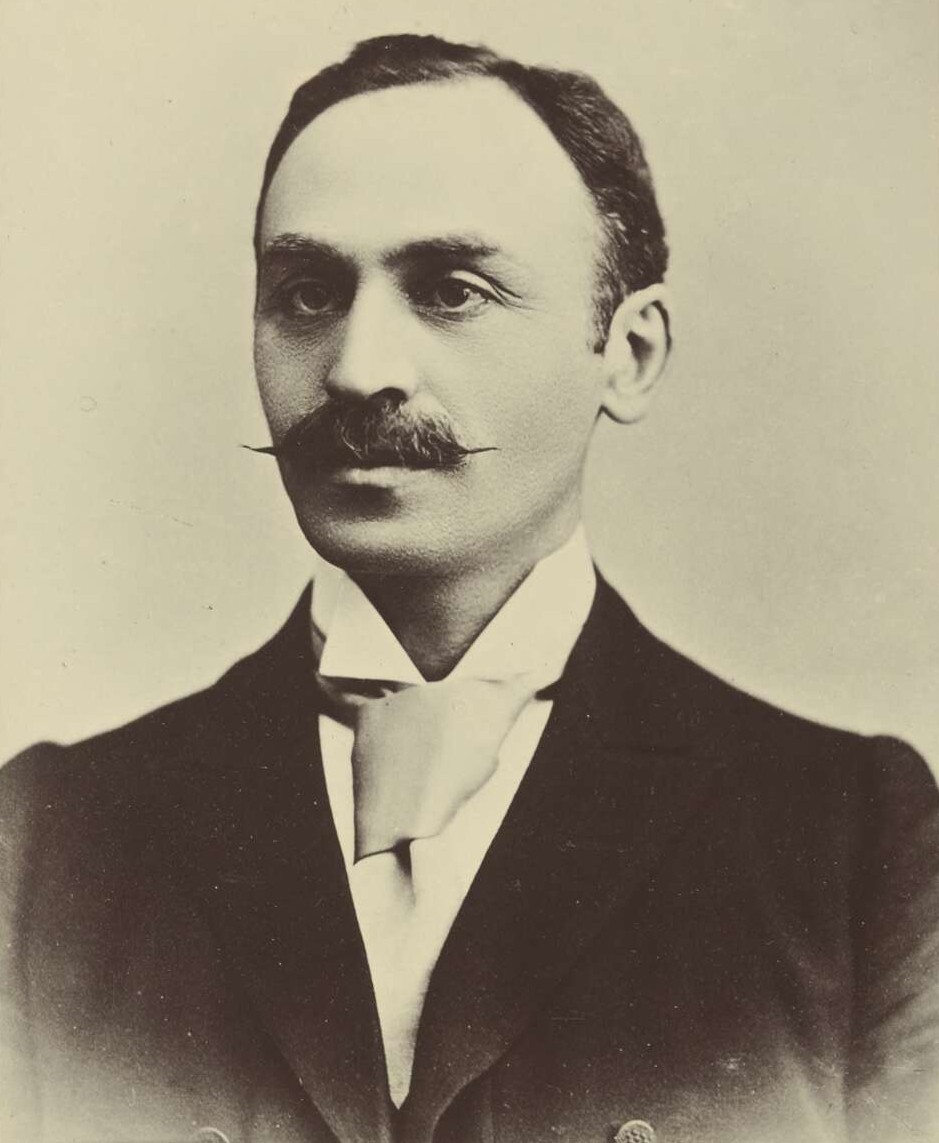

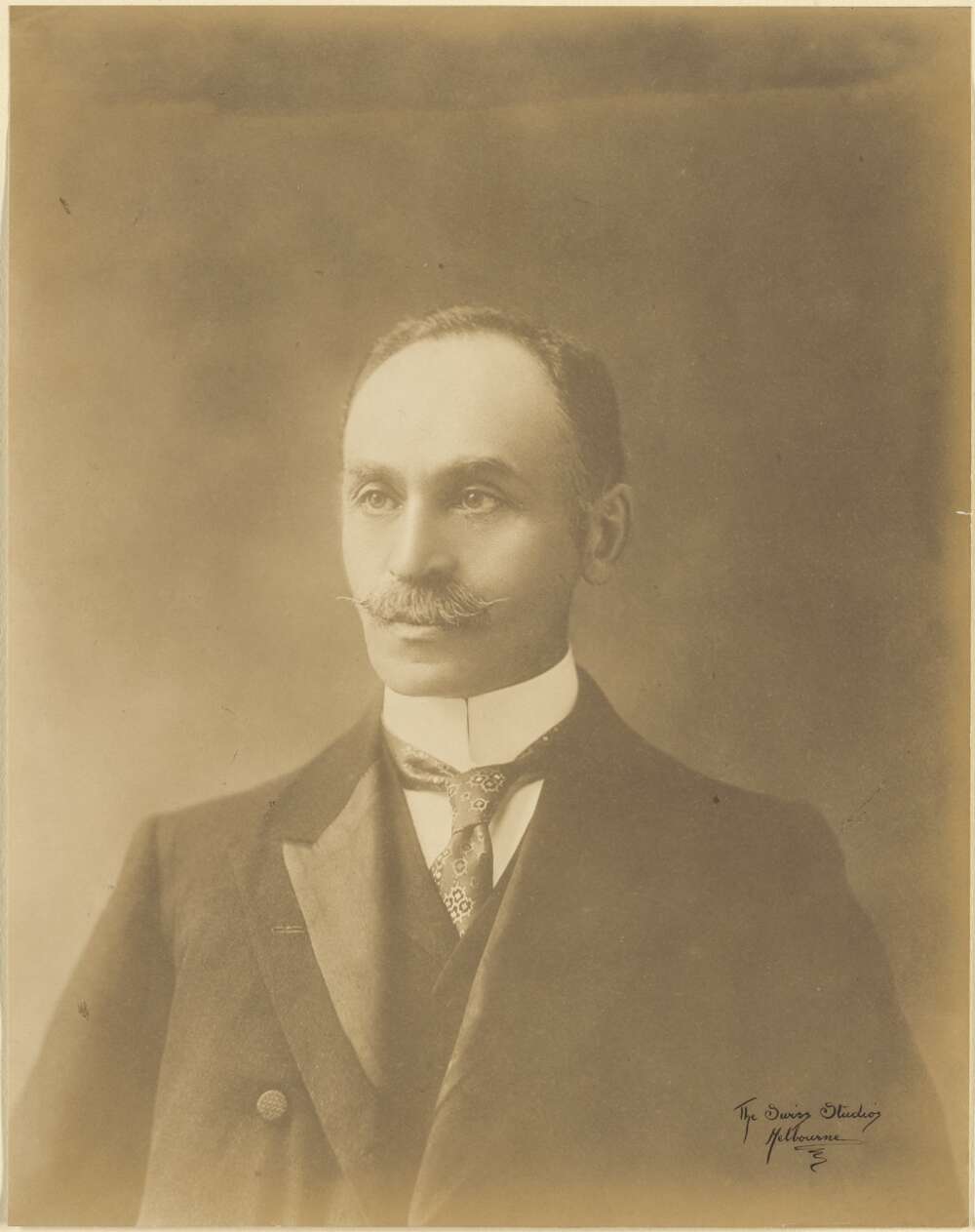

Sir Isaac Alfred Isaacs (6 August 1855 – 11 February 1948) was an Australian lawyer, politician, and judge who served as the ninth Governor-General of Australia, in office from 1931 to 1936. He had previously served on the

Isaacs was the son of Alfred Isaacs, a tailor of

Isaacs was the son of Alfred Isaacs, a tailor of

Isaacs was elected to the first federal Parliament in 1901 to the seat of

Isaacs was elected to the first federal Parliament in 1901 to the seat of

On the High Court, Isaacs joined H. B. Higgins as a radical minority on the court in opposition to the chief justice, Sir Samuel Griffith. He served on the court for 24 years, acquiring a reputation as a learned and radical but uncollegial justice. Isaacs was appointed a

On the High Court, Isaacs joined H. B. Higgins as a radical minority on the court in opposition to the chief justice, Sir Samuel Griffith. He served on the court for 24 years, acquiring a reputation as a learned and radical but uncollegial justice. Isaacs was appointed a

Shortly after Isaacs became Chief Justice, the office of governor-general fell vacant and, after Cabinet discussion, Scullin offered the post to Isaacs. Although the proposal was supposed to be confidential until communicated to

Shortly after Isaacs became Chief Justice, the office of governor-general fell vacant and, after Cabinet discussion, Scullin offered the post to Isaacs. Although the proposal was supposed to be confidential until communicated to

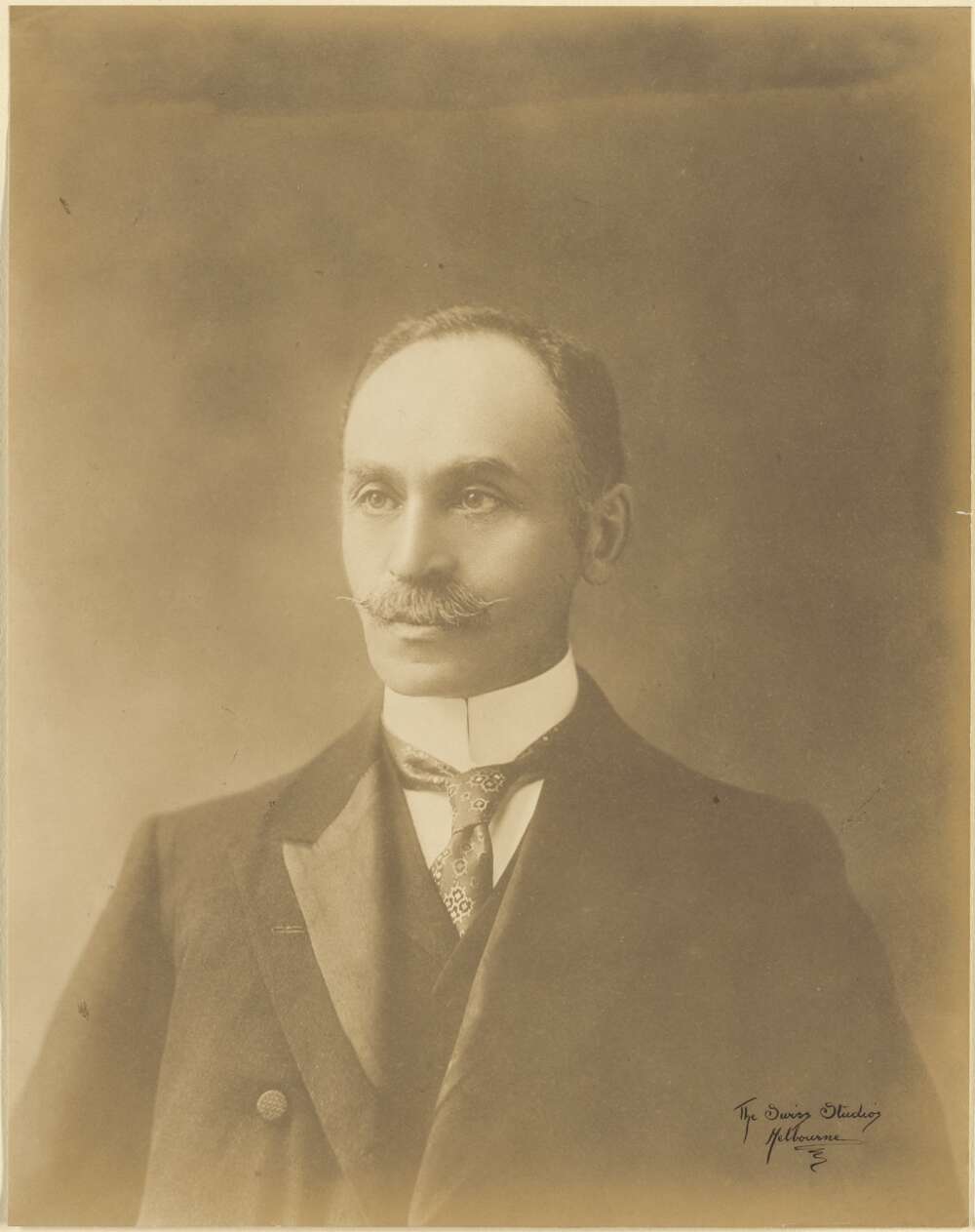

University of Melbourne: Isaac Alfred Isaacs

includes photograph (1898).

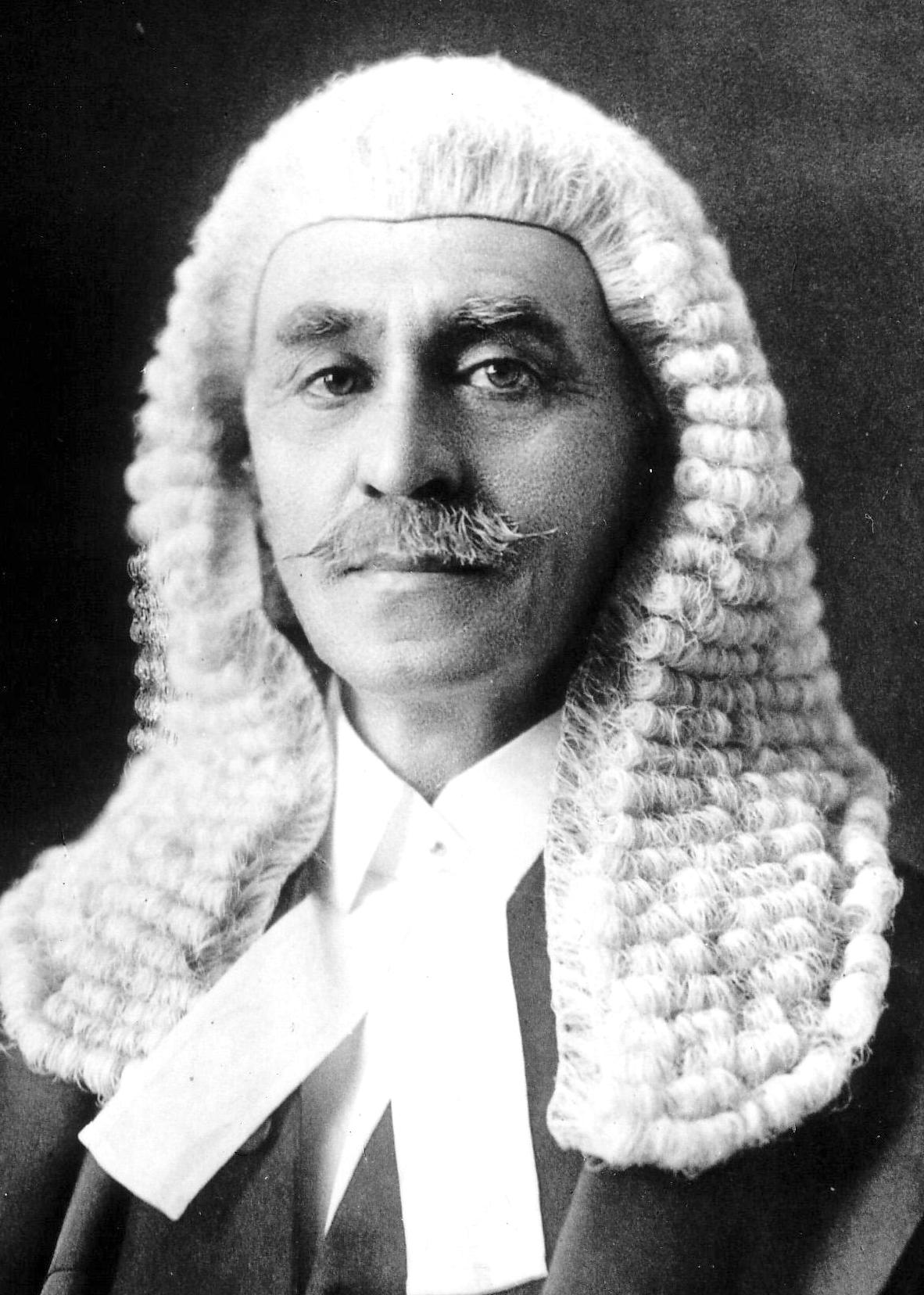

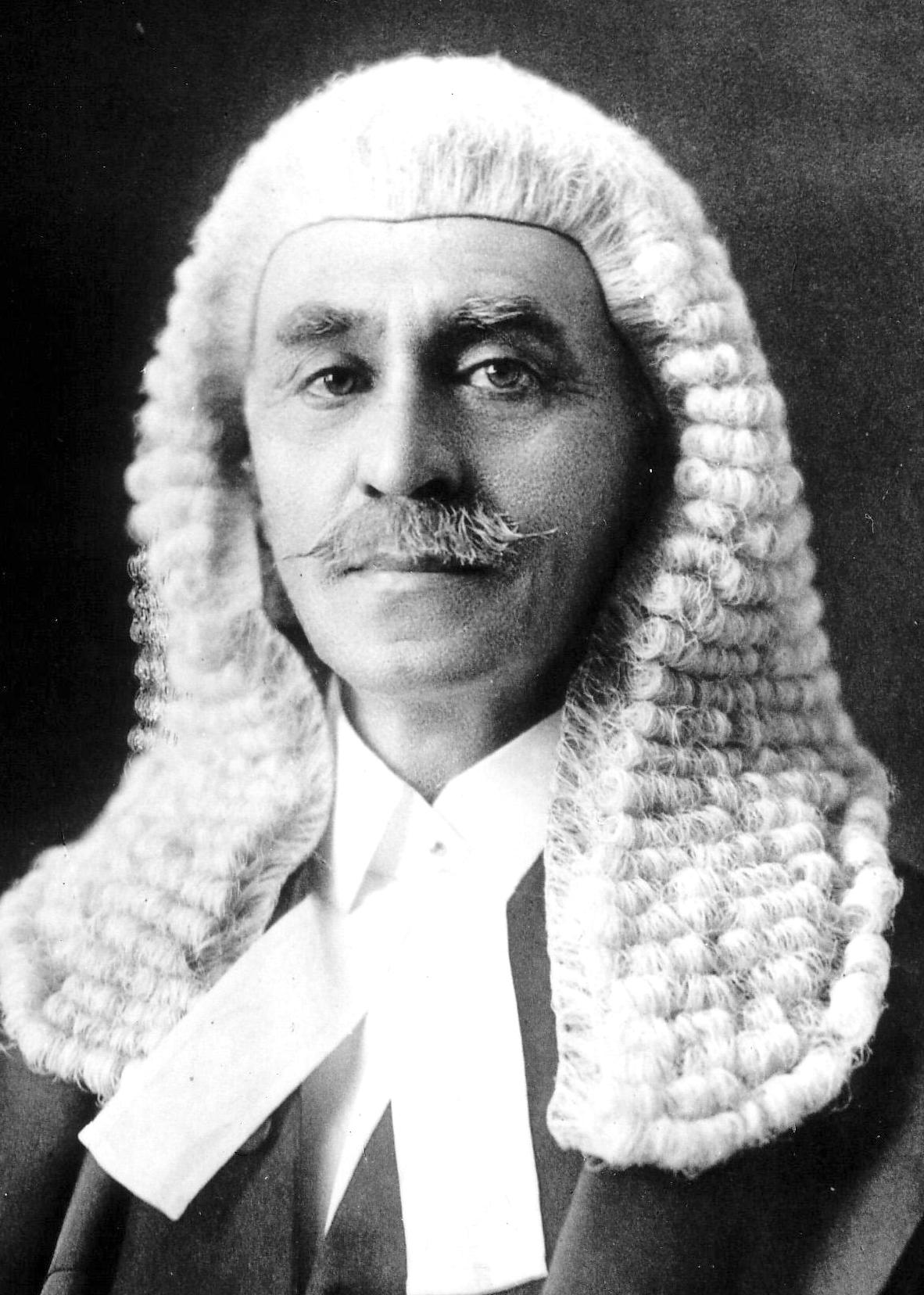

includes portrait as Chief Justice

Indi Election Results 1901Hail to the Chief

Isaacs ("per the medium of" Tony Blackshield) interviewed by Keith Mason in 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2014 * {{DEFAULTSORT:Isaacs, Isaac 1855 births 1948 deaths Governors-General of Australia Australian members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Chief justices of Australia Justices of the High Court of Australia Australian Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Australian Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Australian politicians awarded knighthoods Australian federationists Australian Jews Members of the Australian House of Representatives Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Indi Protectionist Party members of the Parliament of Australia Attorneys-General of Australia Members of the Victorian Legislative Assembly Solicitors-General of Victoria Attorneys-General of the Colony of Victoria Politicians from Melbourne Australian King's Counsel 20th-century King's Counsel Australian people of Polish-Jewish descent Jewish anti-Zionism in Oceania Jewish Australian politicians Melbourne Law School alumni 20th-century Australian politicians Burials at Melbourne General Cemetery

High Court of Australia

The High Court of Australia is Australia's apex court. It exercises original and appellate jurisdiction on matters specified within Australia's Constitution.

The High Court was established following passage of the '' Judiciary Act 1903''. ...

from 1906 to 1931, including as Chief Justice from 1930.

Isaacs was born in Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/ Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a metro ...

and grew up in Yackandandah and Beechworth (in country Victoria). He began working as a schoolteacher at the age of 15, and later moved to Melbourne to work as a clerk and studied law part-time at the University of Melbourne

The University of Melbourne is a public research university located in Melbourne, Australia. Founded in 1853, it is Australia's second oldest university and the oldest in Victoria. Its main campus is located in Parkville, an inner suburb ...

. Isaacs was admitted to the bar in 1880, and soon became one of Melbourne's best-known barristers. He was elected to the Victorian Legislative Assembly

The Victorian Legislative Assembly is the lower house of the bicameral Parliament of Victoria in Australia; the upper house being the Victorian Legislative Council. Both houses sit at Parliament House in Spring Street, Melbourne.

The presidin ...

in 1892, and subsequently served as Solicitor-General under James Patterson, and Attorney-General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

under George Turner and Alexander Peacock

Sir Alexander James Peacock (11 June 1861 – 7 October 1933) was an Australian politician who served as the 20th Premier of Victoria.

Early Years

Peacock was born of Scottish descent at Creswick, the first Victorian Premier born after ...

.

Isaacs entered the new federal parliament at the 1901 election, representing the Protectionist Party

The Protectionist Party or Liberal Protectionist Party was an Australian political party, formally organised from 1887 until 1909, with policies centred on protectionism. The party advocated protective tariffs, arguing it would allow Australi ...

. He became Attorney-General of Australia

The Attorney-GeneralThe title is officially "Attorney-General". For the purposes of distinguishing the office from other attorneys-general, and in accordance with usual practice in the United Kingdom and other common law jurisdictions, the Aust ...

in 1905, under Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin (3 August 1856 – 7 October 1919) was an Australian politician who served as the second Prime Minister of Australia. He was a leader of the movement for Federation, which occurred in 1901. During his three terms as prime ministe ...

, but the following year left politics in order to become a justice of the High Court. Isaacs was often in the minority in his early years on the court, particularly with regard to federalism

Federalism is a combined or compound mode of government that combines a general government (the central or "federal" government) with regional governments ( provincial, state, cantonal, territorial, or other sub-unit governments) in a single ...

, where he advocated the supremacy of the Commonwealth Government. The balance of the court eventually shifted, and he famously authored the majority opinion in the '' Engineers case'' of 1920, which abolished the reserved powers doctrine and fully established the paramountcy of Commonwealth law.

In 1930, Prime Minister James Scullin appointed Isaacs as Chief Justice, in succession to Sir Adrian Knox

Sir Adrian Knox KCMG, KC (29 November 186327 April 1932) was an Australian lawyer and judge who served as the second Chief Justice of Australia, in office from 1919 to 1930.

Knox was born in Sydney, the son of businessman Sir Edward Knox. H ...

. Later that year, Scullin nominated Isaacs as his preferred choice for governor-general. The selection of an Australian (rather than the usual British aristocrat) was unprecedented and highly controversial. King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother ...

was opposed to the idea but eventually consented, and Isaacs took office in January 1931 as the first Australian-born holder of the office. He was the first governor-general to live full-time at Yarralumla, and throughout his five-year term was popular among the public for his frugality during the Depression. Isaacs was Australia's first Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

High Court Justice, the first Jewish Chief Justice of Australia and also the first Jewish Governor-General of Australia. He was a strong Anti-Zionist

Anti-Zionism is opposition to Zionism. Although anti-Zionism is a heterogeneous phenomenon, all its proponents agree that the creation of the modern State of Israel, and the movement to create a sovereign Jewish state in the region of Palesti ...

. Early life

Isaacs was the son of Alfred Isaacs, a tailor of

Isaacs was the son of Alfred Isaacs, a tailor of Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

ancestry from the town of Mława, Poland. Seeking better prospects, Alfred left Poland and worked his way across what is now Germany, spending some months in Berlin and Frankfurt

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , " Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on it ...

. By 1845 he had passed through Paris and arrived to work in London, where he met Rebecca Abrahams; the two married in 1849. After news of the 1851 Victorian gold rush

The Victorian gold rush was a period in the history of Victoria, Australia approximately between 1851 and the late 1860s. It led to a period of extreme prosperity for the Australian colony, and an influx of population growth and financial capit ...

reached England, Australia became a very popular destination and the Isaacs decided to emigrate. By 1854 they had saved enough for the fare, departing from Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

in June 1854 and arriving in Melbourne in September. Some time after arriving the Isaacs moved into a cottage and shopfront

Shopfront Arts Co-op is a theatre facility, with three rehearsal studios, sound studio and digital film editing suite, located in Carlton, New South Wales, Australia. Also known as Shopfront Theatre For Young People, its stated aim is to p ...

in Elizabeth Street, Melbourne, where Alfred continued his tailoring. Isaac Alfred Isaacs was born in this cottage on 6 August 1855. His family moved to various locations around Melbourne while he was young, then in 1859 moved to Yackandandah in northern Victoria, close to family friends. At this time Yackandandah was a gold mining settlement of 3,000 people.

Isaacs had siblings born in Melbourne and Yackandandah: John A. Isaacs, who later became a solicitor and Victorian Member of Parliament, and sisters Carolyn and Hannah were all born in Yackandandah. A brother was born in Melbourne, and another sister was born in Yackandandah, but both died very young. His first formal schooling was from sometime after 1860 at a small private establishment. At eight he won the school arithmetic

Arithmetic () is an elementary part of mathematics that consists of the study of the properties of the traditional operations on numbers— addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, exponentiation, and extraction of roots. In the 19th ...

prize, winning his photograph by the schoolmaster, who was also a photographer and bootmaker. Yackandandah state school was opened in 1863 and Isaacs enrolled as a pupil. Here he excelled academically, particularly in arithmetic and languages, though he was a frequent truant

Truancy is any intentional, unjustified, unauthorised, or illegal absence from compulsory education. It is a deliberate absence by a student's own free will (though sometimes adults or parents will allow and/or ignore it) and usually does not ref ...

, walking off to spend time in the nearby mining camps. To help Isaacs gain a better quality education, in 1867, his family moved to nearby Beechworth first enrolling him in the Common school then in the Beechworth Grammar School

A grammar school is one of several different types of school in the history of education in the United Kingdom and other English-speaking countries, originally a school teaching Latin, but more recently an academically oriented secondary school ...

. He excelled at the Grammar School, becoming dux in his first year and winning many academic prizes. In his second year he was employed part-time as an assistant teacher at the school, and took up after school tutoring of fellow students. In September 1870, when Isaacs was just 15 years old, he passed his examination as a pupil teacher and taught at the school from then until 1873. Isaacs was next employed as an assistant teacher at the Beechworth State School, the successor to the Common school.

While employed at the State School, Isaacs had his first experience of the law, as an unsuccessful litigant in an 1875 County Court case. He disputed a payment arrangement with the headmaster of his school, resigning as part of the dispute. After returning to teaching, now back at the Grammar School, he expanded his interest in the law; reading law books and attending court sittings.

As a child Isaacs became fluent in Russian, which his parents spoke frequently, as well as English and some German. Isaacs later gained varying degrees of proficiency in Italian, French, Greek, Hindustani and Chinese.

Legal career

In 1875, he moved to Melbourne and found work at the Prothonotary's Office of the Law Department. In 1876, while still working full-time, he studied law at theUniversity of Melbourne

The University of Melbourne is a public research university located in Melbourne, Australia. Founded in 1853, it is Australia's second oldest university and the oldest in Victoria. Its main campus is located in Parkville, an inner suburb ...

. He graduated in 1880 with a Master of Laws

A Master of Laws (M.L. or LL.M.; Latin: ' or ') is an advanced postgraduate academic degree, pursued by those either holding an undergraduate academic law degree, a professional law degree, or an undergraduate degree in a related subject. In mo ...

degree in 1883. He took silk as a Queen's Counsel

In the United Kingdom and in some Commonwealth countries, a King's Counsel (post-nominal initials KC) during the reign of a king, or Queen's Counsel (post-nominal initials QC) during the reign of a queen, is a lawyer (usually a barrister o ...

in 1899.

Political career

Victorian MP, 1892–1901

In 1892 Isaacs was elected to the Victorian Legislative Assembly as a liberal. He was the member for Bogong from May 1892 until May 1893 and between June 1893 and May 1901. In 1893 he became Solicitor-General in the Patterson ministry. From 1894 to 1899 he was Attorney-General in the Turner ministry, and served as acting Premier on some occasions. In 1897 he was elected to the convention to approve the terms of theAustralian Constitution

The Constitution of Australia (or Australian Constitution) is a constitutional document that is supreme law in Australia. It establishes Australia as a federation under a constitutional monarchy and outlines the structure and powers of the A ...

. However, he was not elected to the committee drafting the constitution; Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin (3 August 1856 – 7 October 1919) was an Australian politician who served as the second Prime Minister of Australia. He was a leader of the movement for Federation, which occurred in 1901. During his three terms as prime ministe ...

attributed this failure to "a plot discreditable to all engaged in it" and thought that this antagonizing and humiliating snub sharpened Isaacs's "tendency to minute technical criticism ... so as to bring him not infrequently into collision" with the committee. Isaacs had many reservations about the draft constitution, but he campaigned in support of it after the Australian Natives' Association gave the draft its full support, rejecting his plea to delay for further consideration.

Federal MP, 1901–1906

Isaacs was elected to the first federal Parliament in 1901 to the seat of

Isaacs was elected to the first federal Parliament in 1901 to the seat of Indi

Indi may refer to:

*Mag-indi language

* Division of Indi, an electoral division in the Australian House of Representatives

*Indi, Karnataka, a town in the state of Karnataka, India

*Instrument Neutral Distributed Interface, a distributed control sy ...

as a critical supporter of Edmund Barton

Sir Edmund "Toby" Barton, (18 January 18497 January 1920) was an Australian politician and judge who served as the first prime minister of Australia from 1901 to 1903, holding office as the leader of the Protectionist Party. He resigned to b ...

and his Protectionist government. He was one of a group of backbenchers pushing for more radical policies and he earned the dislike of many of his colleagues through what they saw as his aloofness and rather self-righteous attitude to politics.

Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin (3 August 1856 – 7 October 1919) was an Australian politician who served as the second Prime Minister of Australia. He was a leader of the movement for Federation, which occurred in 1901. During his three terms as prime ministe ...

appointed Isaacs Attorney-General in 1905 but he was a difficult colleague and in 1906 Deakin was keen to get him out of politics by appointing him to the High Court bench. He was the first serving minister to resign from the parliament.

High Court, 1906–1931

On the High Court, Isaacs joined H. B. Higgins as a radical minority on the court in opposition to the chief justice, Sir Samuel Griffith. He served on the court for 24 years, acquiring a reputation as a learned and radical but uncollegial justice. Isaacs was appointed a

On the High Court, Isaacs joined H. B. Higgins as a radical minority on the court in opposition to the chief justice, Sir Samuel Griffith. He served on the court for 24 years, acquiring a reputation as a learned and radical but uncollegial justice. Isaacs was appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George IV, Prince of Wales, while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George III.

It is named in honour ...

in the King's Birthday Honours of 1928 for his service on the High Court. Isaacs is one of only eight justices of the High Court to have served in the Parliament of Australia

The Parliament of Australia (officially the Federal Parliament, also called the Commonwealth Parliament) is the legislative branch of the government of Australia. It consists of three elements: the monarch (represented by the governor- ...

prior to his appointment to the court; the others were Edmund Barton

Sir Edmund "Toby" Barton, (18 January 18497 January 1920) was an Australian politician and judge who served as the first prime minister of Australia from 1901 to 1903, holding office as the leader of the Protectionist Party. He resigned to b ...

, Richard O'Connor, H. B. Higgins, Edward McTiernan, John Latham, Garfield Barwick

Sir Garfield Edward John Barwick, (22 June 190313 July 1997) was an Australian judge who was the seventh and longest serving Chief Justice of Australia, in office from 1964 to 1981. He had earlier been a Liberal Party politician, serving as a m ...

, and Lionel Murphy. He was also one of two to have served in the Parliament of Victoria, along with Higgins. In April 1930, the Labor

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the la ...

Prime Minister, James Scullin, appointed the 75-year-old Isaacs as chief justice, succeeding Sir Adrian Knox

Sir Adrian Knox KCMG, KC (29 November 186327 April 1932) was an Australian lawyer and judge who served as the second Chief Justice of Australia, in office from 1919 to 1930.

Knox was born in Sydney, the son of businessman Sir Edward Knox. H ...

.

Governor-General, 1931–1936

Shortly after Isaacs became Chief Justice, the office of governor-general fell vacant and, after Cabinet discussion, Scullin offered the post to Isaacs. Although the proposal was supposed to be confidential until communicated to

Shortly after Isaacs became Chief Justice, the office of governor-general fell vacant and, after Cabinet discussion, Scullin offered the post to Isaacs. Although the proposal was supposed to be confidential until communicated to King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

, word got out. While Isaacs was personally esteemed, public opinion divided strongly over whether a governor-general should be an Australian, with perceived risks of local political bias. During Scullin's 1930 trip to Europe he personally advised the King to make the appointment and, although the King shared the concern about local political bias, he reluctantly accepted Scullin's advice, while noting in his diary that he thought the choice would be “very unpopular” in Australia.

Isaacs's appointment was announced in December 1930, and he was sworn in on 22 January 1931. He was the first Australian-born governor-general. Thus Isaacs agreed to a reduction in salary and conducted the office with great frugality. He gave up his official residences in Sydney and Melbourne and most official entertaining. Although he was sworn into office in the chamber of the Victorian Legislative Council

The Victorian Legislative Council (VLC) is the upper house of the bicameral Parliament of Victoria, Australia, the lower house being the Legislative Assembly. Both houses sit at Parliament House in Spring Street, Melbourne. The Legislative C ...

in Melbourne, rather than in Parliament House in Canberra, he was the first governor-general to live permanently at Government House, Canberra. This was well-received with the public, as was Isaacs's image of rather austere dignity. Isaacs was promoted to a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George IV, Prince of Wales, while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George III.

It is named in honour ...

in April 1932. His term as governor-general concluded on 23 January 1936, and he retired to Victoria. In 1937, he was further honoured with the award of Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved bathing (as a symbol of purification) as one ...

.

Personal life

Isaacs married Deborah "Daisy" Jacobs, daughter of a tobacco merchant, at her parents' home in St Kilda on 18 July 1888. They had two daughters, one born in 1890 and the other in 1892. The daughters were Marjorie Isaacs Cohen who died in 1968 and was survived by a son (Thomas B. Cohen), and Nancy Isaacs Cullen. Lady Isaacs died atBowral, New South Wales

Bowral () is the largest town in the Southern Highlands of New South Wales, Australia, about ninety minutes southwest of Sydney. It is the main business and entertainment precinct of the Wingecarribee Shire and Highlands.

Bowral once served a ...

, in 1960.

Later life and death

Isaacs was 81 when his term ended in 1936, but his public life was far from over. He remained active in various causes for another decade and wrote frequently on matters of constitutional law. In the 1940s he became embroiled in controversy with the Jewish community both in Australia and internationally through his outspoken opposition toZionism

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

. His principal critic was Julius Stone. Isaacs was supported by Rabbi Jacob Danglow (1880–1962) and Harold Boas

Harold Boas OBE (27 September 1883 – 17 September 1980) was a town planner and architect in Western Australia. Boas designed many public buildings in and around Perth and was an influential Jewish community leader. He served as an elected me ...

. Isaacs insisted that Judaism was a religious identity and not a national or ethnic one. He opposed the notion of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Isaacs said " litical Zionism to which I am irrevocably opposed for the reasons which will be found clearly stated, must be sharply distinguished from religious and cultural Zionism to which I am strongly attached."

Isaacs opposed Zionism partly because he disliked nationalism of all kinds and saw Zionism as a form of Jewish national chauvinism—and partly because he saw the Zionist agitation in Palestine as disloyalty to the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

, to which he was devoted. Following the King David Hotel bombing

The British administrative headquarters for Mandatory Palestine, housed in the southern wing of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, were bombed in a terrorist attack on 22 July 1946 by the militant right-wing Zionist underground organization th ...

in 1946, he wrote that "the honour of Jews throughout the world demands the renunciation of political Zionism".

Isaacs's main objections to Political Zionism were:

# "A negation of Democracy, and an attempt to revert to the Church-State of bygone ages.

# Provocative of anti-Semitism.

# Unwarranted by the Balfour Declaration, the Mandate, or any other right; contrary to Zionist assurances to Britain and to the Arabs and in present conditions unjust to other Palestinians politically and to other religions.

# As regards unrestricted immigration, a discriminatory and an undemocratic camouflage for a Jewish State.

# An obstruction to the consent of the Arabs to the peaceful and prosperous settlement in Palestine of hundreds of thousands of suffering European Jews, the victims of Nazi atrocities; and provocative of Muslim antagonism within and beyond the Empire, and consequently a danger to its integrity and safety.

# Inconsistent in demanding on one hand, on a basis of a separate Jewish nationality everywhere Jews are found, Jewish domination in Palestine, and at the same time claiming complete Jewish equality elsewhere than in Palestine, on the basis of a nationality common to the citizens of every faith."

Isaacs said "the Zionist movement as a whole...now places its own unwarranted interpretation on the Balfour Declaration, and makes demands that are arousing the antagonism of the Muslim world of nearly 400 millions, thereby menacing the safety of our Empire, endangering world peace and imperiling some of the most sacred associations of the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim faiths. Besides their inherent injustice to others these demands would, I believe, seriously and detrimentally affect the general position of Jews throughout the world".

In his later years, Isaacs became embroiled in legal battles with Edna Davis, the wife of his brother John. He forced her out of the family home, reclaimed her wedding ring, and finally had her declared a vexatious litigant.

Isaacs died at his home in South Yarra

South Yarra is an inner-city suburb in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 4 km south-east of Melbourne's Central Business District, located within the Cities of Melbourne and Stonnington local government areas. South Yarra recorded a popu ...

, Victoria, in the early hours of 11 February 1948, at the age of 92. He was the last surviving member of Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin (3 August 1856 – 7 October 1919) was an Australian politician who served as the second Prime Minister of Australia. He was a leader of the movement for Federation, which occurred in 1901. During his three terms as prime ministe ...

's 1905–1906 Cabinet. The Commonwealth government accorded him a state funeral, held on 13 February, and he was buried in Melbourne General Cemetery

The Melbourne General Cemetery is a large (43 hectare) necropolis located north of the city of Melbourne in the suburb of Carlton North.

The cemetery is notably the resting place of four Prime Ministers of Australia, more than any othe ...

after a synagogue service.

Honours

In May 1949 he was honoured with the naming of the Australian Electoral Division of Isaacs in the outer southern suburbs of Melbourne. At a redistribution in November 1968, the electorate was abolished and a separate Division of Isaacs was created in the south-eastern suburbs of Melbourne. It exists to this day. TheCanberra

Canberra ( )

is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The ci ...

suburb of Isaacs Isaacs may refer to:

* The Isaacs, a bluegrass Southern gospel music group

* Isaacs (surname)

* Isaacs, Australian Capital Territory, a suburb of Canberra, Australia

* Division of Isaacs, a federal electoral division in Victoria, Australia

* Divi ...

was named after him in 1966.

In 1973 Isaacs was honoured with an Australian postage stamp bearing his portrait.

Bibliography

Works by Isaacs

* * * * * * *Works about Isaacs

* ; new ed. University of Queensland Press, 1993 * * * * *Notes

Sources

* * *External links

University of Melbourne: Isaac Alfred Isaacs

includes photograph (1898).

includes portrait as Chief Justice

Isaacs ("per the medium of" Tony Blackshield) interviewed by Keith Mason in 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2014 * {{DEFAULTSORT:Isaacs, Isaac 1855 births 1948 deaths Governors-General of Australia Australian members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Chief justices of Australia Justices of the High Court of Australia Australian Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Australian Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Australian politicians awarded knighthoods Australian federationists Australian Jews Members of the Australian House of Representatives Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Indi Protectionist Party members of the Parliament of Australia Attorneys-General of Australia Members of the Victorian Legislative Assembly Solicitors-General of Victoria Attorneys-General of the Colony of Victoria Politicians from Melbourne Australian King's Counsel 20th-century King's Counsel Australian people of Polish-Jewish descent Jewish anti-Zionism in Oceania Jewish Australian politicians Melbourne Law School alumni 20th-century Australian politicians Burials at Melbourne General Cemetery