Invisible Man on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Invisible Man'' is a novel by

Ellison's "ancestors" included, among others, ''

Ellison's "ancestors" included, among others, ''

Ralph Ellison, 1914–1994: His Book ''Invisible Man'' Won Awards and Is Still Discussed Today

(VOA Special English).

Full text of ''The Paris Review'''s 1955 interview with Mr. Ellison

* ttp://www.randomhouse.com/highschool/catalog/display.pperl?isbn=9780679732761&view=tg Teacher's Guideat Random House.

''Invisible Man''

study guide, themes, quotes, character analyses, teaching resources. {{Authority control 1952 American novels 1952 debut novels African-American novels American autobiographical novels Existentialist novels Harlem in fiction National Book Award for Fiction winning works Novels about race and ethnicity Novels by Ralph Ellison Novels set in Manhattan Random House books Southern United States in fiction

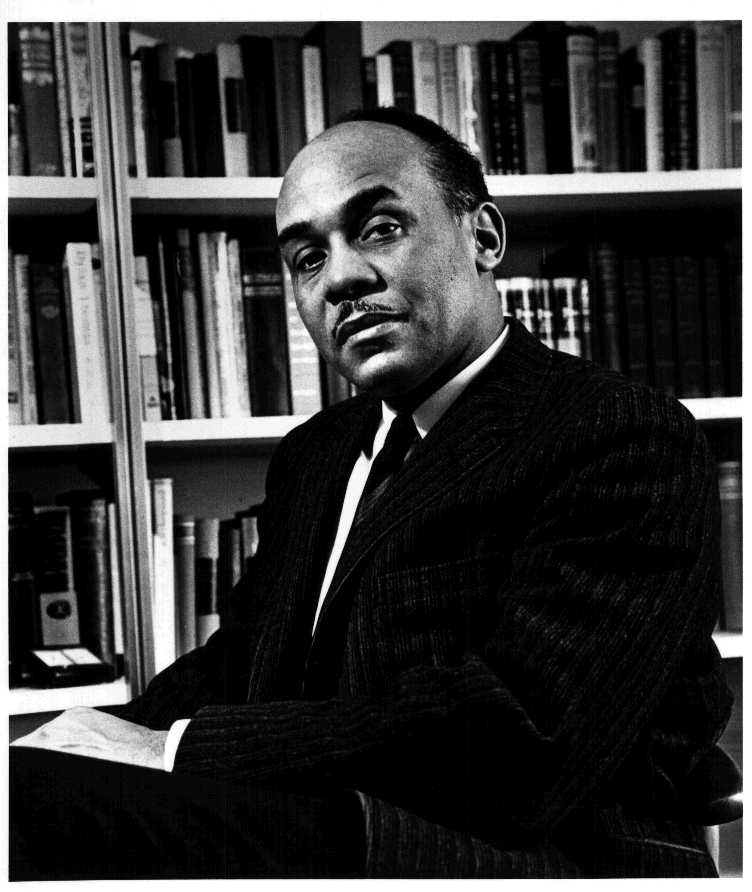

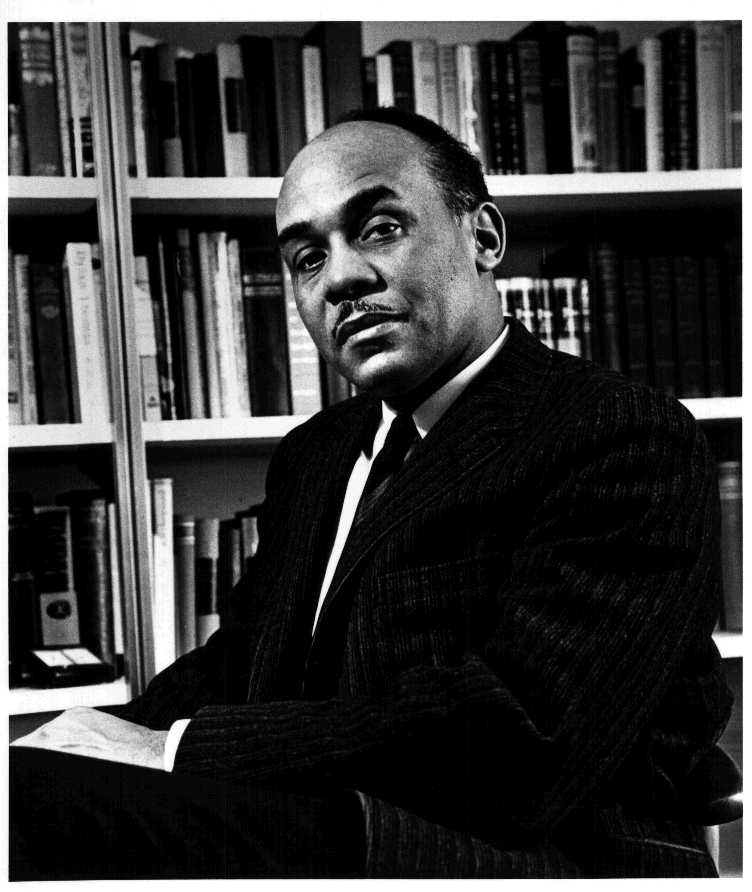

Ralph Ellison

Ralph Waldo Ellison (March 1, 1913 – April 16, 1994) was an American writer, literary critic, and scholar best known for his novel '' Invisible Man'', which won the National Book Award in 1953. He also wrote ''Shadow and Act'' (1964), a collec ...

, published by Random House

Random House is an American book publisher and the largest general-interest paperback publisher in the world. The company has several independently managed subsidiaries around the world. It is part of Penguin Random House, which is owned by Germ ...

in 1952. It addresses many of the social and intellectual issues faced by African Americans in the early twentieth century, including black nationalism

Black nationalism is a type of racial nationalism or pan-nationalism which espouses the belief that black people are a race, and which seeks to develop and maintain a black racial and national identity. Black nationalist activism revolves aro ...

, the relationship between black identity and Marxism

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialectical ...

, and the reformist racial policies of Booker T. Washington, as well as issues of individuality

An individual is that which exists as a distinct entity. Individuality (or self-hood) is the state or quality of being an individual; particularly (in the case of humans) of being a person unique from other people and possessing one's own need ...

and personal identity

Personal identity is the unique numerical identity of a person over time. Discussions regarding personal identity typically aim to determine the necessary and sufficient conditions under which a person at one time and a person at another time ca ...

.

''Invisible Man'' won the U.S. National Book Award for Fiction in 1953, making Ellison the first African American writer to win the award.

In 1998, the Modern Library ranked ''Invisible Man'' 19th on its list of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century. ''Time'' magazine included the novel in its 100 Best English-language Novels from 1923 to 2005 list, calling it "the quintessential American picaresque

The picaresque novel ( Spanish: ''picaresca'', from ''pícaro'', for "rogue" or "rascal") is a genre of prose fiction. It depicts the adventures of a roguish, but "appealing hero", usually of low social class, who lives by his wits in a corru ...

of the 20th century," rather than a "race novel, or even a ''bildungsroman

In literary criticism, a ''Bildungsroman'' (, plural ''Bildungsromane'', ) is a literary genre that focuses on the psychological and moral growth of the protagonist from childhood to adulthood (coming of age), in which character change is import ...

''." Malcolm Bradbury

Sir Malcolm Stanley Bradbury, (7 September 1932 – 27 November 2000) was an English author and academic.

Life

Bradbury was born in Sheffield, the son of a railwayman. His family moved to London in 1935, but returned to Sheffield in 1941 with ...

and Richard Ruland recognize an existential vision with a "Kafka-like absurdity." According to ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'', Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the ...

modeled his 1995 memoir '' Dreams from My Father'' on Ellison's novel.

Background

Ellison says in his introduction to the 30th Anniversary Edition that he started to write what would eventually become ''Invisible Man'' in a barn inWaitsfield, Vermont

Waitsfield is a town in Washington County, Vermont, United States. The population was 1,844 as of the 2020 census. It was created by a Vermont charter on February 25, 1782, and was granted to militia Generals Benjamin Wait, Roger Enos and oth ...

, in the summer of 1945 while on sick leave

Sick leave (or paid sick days or sick pay) is paid time off from work that workers can use to stay home to address their health needs without losing pay. It differs from paid vacation time or time off work to deal with personal matters, because sic ...

from the Merchant Marine.Ellison, Ralph Waldo 1982. ''Invisible Man''. New York: Random House. The barn was actually in the neighboring town of Fayston. The book took five years to complete with one year off for what Ellison termed an "ill-conceived short novel". ''Invisible Man'' was published as a whole in 1952. Ellison had published a section of the book in 1947, the famous "Battle Royal" scene, which had been shown to Cyril Connolly, the editor of '' Horizon'' magazine by Frank Taylor, one of Ellison's early supporters.

In his speech accepting the 1953 National Book Award

The National Book Awards are a set of annual U.S. literary awards. At the final National Book Awards Ceremony every November, the National Book Foundation presents the National Book Awards and two lifetime achievement awards to authors.

The Nat ...

, Ellison said that he considered the novel's chief significance to be its "experimental attitude". Before ''Invisible Man'', many (if not most) novels dealing with African Americans were written solely for social protest, notably, '' Native Son'' and ''Uncle Tom's Cabin

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans and slavery in the U ...

''. The narrator in ''Invisible Man'' says, "I am not complaining, nor am I protesting either", signaling the break from the normal protest novel that Ellison held about his work. In the essay 'The World and the Jug,' which is a response to Irving Howe

Irving Howe (; June 11, 1920 – May 5, 1993) was an American literary and social critic and a prominent figure of the Democratic Socialists of America.

Early years

Howe was born as Irving Horenstein in The Bronx, New York. He was the son of ...

's essay 'Black Boys and Native Sons,' which "pit Ellison and ames

Ames may refer to:

Places United States

* Ames, Arkansas, a place in Arkansas

* Ames, Colorado

* Ames, Illinois

* Ames, Indiana

* Ames, Iowa, the most populous city bearing this name

* Ames, Kansas

* Ames, Nebraska

* Ames, New York

* Ames, Ok ...

Baldwin against ichardWright and then", as Ellison would say, "gives Wright the better argument", Ellison makes a fuller statement about the position he held about his book in the larger canon of work by an American who happens to be of African ancestry. In the opening paragraph to that essay Ellison poses three questions: "Why is it so often true that when critics confront the American as Negro they suddenly drop their advanced critical armament and revert with an air of confident superiority to quite primitive modes of analysis? Why is it that Sociology-oriented critics seem to rate literature

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to include ...

so far below politics and ideology that they would rather kill a novel than modify their presumptions concerning a given reality which it seeks in its own terms to project? Finally, why is it that so many of those who would tell us the meaning of Negro life never bother to learn how varied it really is?"

Placing Invisible Man within the canon of either the Harlem Renaissance or the Black Arts Movement is difficult. It owes allegiance to both and neither. Ellison's resistance to being pigeonholed by his peers bubbled over into his statement to Irving Howe about what he deemed to be a relative vs. an ancestor. He says to Howe "...perhaps you will understand when I say that he right

Rights are legal, social, or ethical principles of freedom or entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal system, social convention, or ethical ...

did not influence me if I point out that while one can do nothing about choosing one's relatives, one can, as an artist, choose one's 'ancestors'. Wright was, in this sense, a 'relative'; Hemingway an 'ancestor.' " It was this idea of "playing the field," so to speak, not being "all-in," that lead to some of Ellison's more staunch critics. Howe, in "Black Boys and Native Sons" but also other black writers such as John Oliver Killens, who once denounced ''Invisible Man'' by saying: “The Negro people need Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man like we need a hole in the head or a stab in the back. … It is a vicious distortion of Negro life."

Ellison's "ancestors" included, among others, ''

Ellison's "ancestors" included, among others, ''The Waste Land

''The Waste Land'' is a poem by T. S. Eliot, widely regarded as one of the most important poems of the 20th century and a central work of modernist poetry. Published in 1922, the 434-line poem first appeared in the United Kingdom in the Octob ...

'' by T.S. Eliot. In an interview with Richard Kostelanetz, Ellison states that what he had learned from the poem was imagery and also improvisation techniques he had only before seen in jazz. Some other influences include William Faulkner

William Cuthbert Faulkner (; September 25, 1897 – July 6, 1962) was an American writer known for his novels and short stories set in the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, based on Lafayette County, Mississippi, where Faulkner spent most o ...

and Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer, and journalist. His economical and understated style—which he termed the iceberg theory—had a strong influence on 20th-century f ...

. Ellison once called Faulkner the South's greatest artist. In the Spring 1955 ''Paris Review'', Ellison said of Hemingway: "I read him to learn his sentence structure and how to organize a story. I guess many young writers were doing this, but I also used his description of hunting when I went into the fields the next day. I had been hunting since I was eleven, but no one had broken down the process of wing-shooting for me, and it was from reading Hemingway that I learned to lead a bird. When he describes something in print, believe him; believe him even when he describes the process of art in terms of baseball or boxing; he’s been there."

Some of Ellison's influences had a more direct impact on his novel as when Ellison divulges this, in his introduction to the 30th anniversary of ''Invisible Man'', that the "character" ("in the dual sense of the word") who had announced himself on his page he "associated, ever so distantly, with the narrator of Dostoevsky's Notes From Underground

''Notes from Underground'' ( pre-reform Russian: ; post-reform Russian: ; also translated as ''Notes from the Underground'' or ''Letters from the Underworld'') is a novella by Fyodor Dostoevsky, first published in the journal ''Epoch'' in 186 ...

". Although, despite the "distantly" remark, it appears that Ellison used that novella more than just on that occasion. The beginning of ''Invisible Man'', for example, seems to be structured very similar to ''Notes from Underground'': "I am a sick man" compared to "I am an invisible man".

Arnold Rampersad, Ellison's biographer, expounds that Melville had a profound influence on Ellison's freedom to describe race so acutely and generously. he narrator

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

"resembles no one else in previous fiction so much as he resembles Ishmael of Moby-Dick." Ellison signals his debt in the prologue to the novel, where the narrator remembers a moment of truth under the influence of marijuana and evokes a church service: "Brothers and sisters, my text this morning is the 'Blackness of Blackness.' And the congregation answers: 'That blackness is most black, brother, most black…'" In this scene Ellison "reprises a moment in the second chapter of Moby-Dick", where Ishmael wanders around New Bedford looking for a place to spend the night and enters a black church: "It was a negro church; and the preacher's text was about the blackness of darkness, and the weeping and wailing and teeth-gnashing there." According to Rampersad, it was Melville who "empowered Ellison to insist on a place in the American literary tradition" by his example of "representing the complexity of race and racism so acutely and generously" in Moby-Dick. Other likely influences to Ellison, by way of how much he speaks about them, are: Kenneth Burke

Kenneth Duva Burke (May 5, 1897 – November 19, 1993) was an American literary theorist, as well as poet, essayist, and novelist, who wrote on 20th-century philosophy, aesthetics, criticism, and rhetorical theory. As a literary theorist, Burk ...

, Andre Malraux, and Mark Twain, to name a few.

Political influences and the Communist Party

The letters he wrote to fellow novelist Richard Wright as he started working on the novel provide evidence for his disillusion with and defection from the CPUSA for perceived revisionism. In a letter to Wright on August 18, 1945, Ellison poured out his anger toward party leaders for betraying African-American and Marxist class politics during the war years: "If they want to play ball with the bourgeoisie they needn't think they can get away with it... Maybe we can't smash the atom, but we can, with a few well-chosen, well-written words, smash all that crummy filth to hell." Ellison resisted attempts to ferret out such allusions in the book itself however, stating "I did not want to describe an existing Socialist or Communist or Marxist political group, primarily because it would have allowed the reader to escape confronting certain political patterns, patterns which still exist and of which our two major political parties are guilty in their relationships to Negro Americans."Plot summary

The narrator, an unnamed black man, begins by describing his living conditions: an underground room wired with hundreds of electric lights, operated by power stolen from the city's electric grid. He reflects on the various ways in which he has experienced social invisibility during his life and begins to tell his story, returning to his teenage years. The narrator lives in a small Southern town and, upon graduating from high school, wins a scholarship to an all-black college. However, to receive it, he must first take part in a brutal, humiliatingbattle royal

Battle royal (; also royale) traditionally refers to a fight involving many combatants that is fought until only one fighter remains standing, usually conducted under either boxing or wrestling rules. In recent times, the term has been used in a ...

for the entertainment of the town's rich white dignitaries.

One afternoon during his junior year at the college, the narrator chauffeurs Mr. Norton, a visiting rich white trustee

Trustee (or the holding of a trusteeship) is a legal term which, in its broadest sense, is a synonym for anyone in a position of trust and so can refer to any individual who holds property, authority, or a position of trust or responsibility to ...

, out among the old slave-quarters beyond the campus. By chance, he stops at the cabin of Jim Trueblood, who has caused a scandal by impregnating both his wife and his daughter in his sleep. Trueblood's account horrifies Mr. Norton so badly that he asks the narrator to find him a drink. The narrator drives him to a bar filled with prostitutes and patients from a nearby mental hospital. The mental patients rail against both of them and eventually overwhelm the orderly assigned to keep the patients under control, injuring Mr. Norton in the process. The narrator hurries Mr. Norton away from the chaotic scene and back to campus.

Dr. Bledsoe, the college president, excoriates the narrator for showing Mr. Norton the underside of black life beyond the campus and expels him. However, Bledsoe gives several sealed letters of recommendation to the narrator, to be delivered to friends of the college in order to assist him in finding a job so that he may eventually earn enough to re-enroll. The narrator travels to New York and distributes his letters, with no success; the son of one recipient shows him the letter, which reveals Bledsoe's intent to never admit the narrator as a student again.

Acting on the son's suggestion, the narrator seeks work at the Liberty Paint factory, renowned for its pure white paint. He is assigned first to the shipping department, then to the boiler room, whose chief attendant, Lucius Brockway, is highly paranoid

Paranoia is an instinct or thought process that is believed to be heavily influenced by anxiety or fear, often to the point of delusion and irrationality. Paranoid thinking typically includes persecutory beliefs, or beliefs of conspiracy c ...

and suspects that the narrator is trying to take his job. This distrust worsens after the narrator stumbles into a union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

meeting, and Brockway attacks the narrator and tricks him into setting off an explosion in the boiler room. The narrator is hospitalized and subjected to shock treatment

''Shock Treatment'' is a 1981 American musical comedy film directed by Jim Sharman, and co-written by Sharman and Richard O'Brien. It is a follow-up to the 1975 film ''The Rocky Horror Picture Show''.

While not an outright sequel, the film do ...

, overhearing the doctors' discussion of him as a possible mental patient.

After leaving the hospital, the narrator faints on the streets of Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and Central Park North on the south. The greater Ha ...

and is taken in by Mary Rambo, a kindly old-fashioned woman who reminds him of his relatives in the South. He later happens across the eviction of an elderly black couple and makes an impassioned speech that incites the crowd to attack the law enforcement officials in charge of the proceedings. The narrator escapes over the rooftops and is confronted by Brother Jack, the leader of a group known as "the Brotherhood" that professes its commitment to bettering conditions in Harlem and the rest of the world. At Jack's urging, the narrator agrees to join and speak at rallies to spread the word among the black community. Using his new salary, he pays Mary back the rent he owes her and moves into an apartment provided by the Brotherhood.

The rallies go smoothly at first, with the narrator receiving extensive indoctrination on the Brotherhood's ideology and methods. Soon, though, he encounters trouble from Ras the Exhorter, a fanatical black nationalist

Black nationalism is a type of racial nationalism or pan-nationalism which espouses the belief that black people are a race, and which seeks to develop and maintain a black racial and national identity. Black nationalist activism revolves aro ...

who believes that the Brotherhood is controlled by whites. Neither the narrator nor Tod Clifton, a youth leader within the Brotherhood, is particularly swayed by his words. The narrator is later called before a meeting of the Brotherhood and accused of putting his own ambitions ahead of the group. He is reassigned to another part of the city to address issues concerning women, seduced by the wife of a Brotherhood member, and eventually called back to Harlem when Clifton is reported missing and the Brotherhood's membership and influence begin to falter.

The narrator can find no trace of Clifton at first, but soon discovers him selling dancing Sambo

, aka = Sombo (in English-speaking countries)

, focus = Hybrid

, country = Soviet Union

, pioneers = Viktor Spiridonov, Vasili Oshchepkov, Anatoly Kharlampiev

, famous_pract = List of Practitioners

, oly ...

dolls on the street, having become disillusioned with the Brotherhood. Clifton is shot and killed by a policeman while resisting arrest; at his funeral, the narrator delivers a rousing speech that rallies the crowd to support the Brotherhood again. At an emergency meeting, Jack and the other Brotherhood leaders criticize the narrator for his unscientific arguments and the narrator determines that the group has no real interest in the black community's problems.

The narrator returns to Harlem, trailed by Ras's men, and buys a hat and a pair of sunglasses to elude them. As a result, he is repeatedly mistaken for a man named Rinehart, known as a lover, a hipster, a gambler, a briber, and a spiritual leader. Understanding that Rinehart has adapted to white society at the cost of his own identity, the narrator resolves to undermine the Brotherhood by feeding them dishonest information concerning the Harlem membership and situation. After seducing the wife of one member in a fruitless attempt to learn their new activities, he discovers that riots have broken out in Harlem due to widespread unrest. He realizes that the Brotherhood has been counting on such an event in order to further its own aims. The narrator gets mixed up with a gang of looters, who burn down a tenement

A tenement is a type of building shared by multiple dwellings, typically with flats or apartments on each floor and with shared entrance stairway access. They are common on the British Isles, particularly in Scotland. In the medieval Old Town, i ...

building, and wanders away from them to find Ras, now on horseback, armed with a spear and shield, and calling himself "the Destroyer". Ras shouts for the crowd to lynch the narrator, but the narrator attacks him with the spear and escapes into an underground coal bin. Two white men seal him in, leaving him alone to ponder the racism he has experienced in his life.

The epilogue returns to the present, with the narrator stating that he is ready to return to the world because he has spent enough time hiding from it. He explains that he has told his story in order to help people see past his own invisibility, and also to provide a voice for people with a similar plight: "Who knows but that, on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?"he was happy

Reception

Critic Orville Prescott of ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' called the novel "the most impressive work of fiction by an American Negro which I have ever read," and felt it marked "the appearance of a richly talented writer." Novelist Saul Bellow

Saul Bellow (born Solomon Bellows; 10 July 1915 – 5 April 2005) was a Canadian-born American writer. For his literary work, Bellow was awarded the Pulitzer Prize, the Nobel Prize for Literature, and the National Medal of Arts. He is the only w ...

in his review found it "a book of the very first order, a superb book...it is tragi-comic, poetic, the tone of the very strongest sort of creative intelligence." George Mayberry of ''The New Republic

''The New Republic'' is an American magazine of commentary on politics, contemporary culture, and the arts. Founded in 1914 by several leaders of the progressive movement, it attempted to find a balance between "a liberalism centered in hu ...

'' said Ellison "is a master at catching the shape, flavor and sound of the common vagaries of human character and experience."

Anthony Burgess

John Anthony Burgess Wilson, (; 25 February 1917 – 22 November 1993), who published under the name Anthony Burgess, was an English writer and composer.

Although Burgess was primarily a comic writer, his dystopian satire ''A Clockwork ...

described the novel as "a masterpiece".

In 2003, a sculpture titled "Invisible Man: A Memorial to Ralph Ellison" by Elizabeth Catlett

Elizabeth Catlett, born as Alice Elizabeth Catlett, also known as Elizabeth Catlett Mora (April 15, 1915 – April 2, 2012) was an African American sculptor and graphic artist best known for her depictions of the Black-American experience in the ...

, was unveiled at Riverside Park at 150th Street in Manhattan, opposite from where Ellison lived and three blocks from the Trinity Church Cemetery

The parish of Trinity Church has three separate burial grounds associated with it in New York City. The first, Trinity Churchyard, is located in Lower Manhattan at 74 Trinity Place, near Wall Street and Broadway. Alexander Hamilton, Albert Gal ...

and Mausoleum, where he is interred in a crypt. The 15-foot-high, 10-foot-wide bronze monolith features a hollow silhouette of a man and two granite panels that are inscribed with Ellison quotations.

Adaptation

It was reported in October 2017 that streaming service Hulu was developing the novel into a television series.See also

*African-American literature

African American literature is the body of literature produced in the United States by writers of African descent. It begins with the works of such late 18th-century writers as Phillis Wheatley. Before the high point of slave narratives, African ...

* Black existentialism

* ''Juneteenth

Juneteenth is a federal holiday in the United States commemorating the emancipation of enslaved African Americans. Deriving its name from combining "June" and "nineteenth", it is celebrated on the anniversary of General Order No. 3, i ...

''

* '' Three Days Before the Shooting...''

References

External links

Ralph Ellison, 1914–1994: His Book ''Invisible Man'' Won Awards and Is Still Discussed Today

(VOA Special English).

Full text of ''The Paris Review''

* ttp://www.randomhouse.com/highschool/catalog/display.pperl?isbn=9780679732761&view=tg Teacher's Guideat Random House.

''Invisible Man''

study guide, themes, quotes, character analyses, teaching resources. {{Authority control 1952 American novels 1952 debut novels African-American novels American autobiographical novels Existentialist novels Harlem in fiction National Book Award for Fiction winning works Novels about race and ethnicity Novels by Ralph Ellison Novels set in Manhattan Random House books Southern United States in fiction