Inquisition (Warhammer 40,000) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the

The term "Inquisition" comes from the

The term "Inquisition" comes from the

While belief in

While belief in

"Witchcraft."

''The Catholic Encyclopedia'', Vol. 15. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 12 Jul. 2015 The medieval Church distinguished between "white" and "black" magic. Local folk practice often mixed chants, incantations, and prayers to the appropriate patron saint to ward off storms, to protect cattle, or ensure a good harvest. Bonfires on Midsummer's Eve were intended to deflect natural catastrophes or the influence of fairies, ghosts, and witches. Plants, often harvested under particular conditions, were deemed effective in healing. Black magic was that which was used for a malevolent purpose. This was generally dealt with through confession, repentance, and charitable work assigned as penance. Early Irish canons treated sorcery as a crime to be visited with

Portugal and Spain in the late Middle Ages consisted largely of multicultural territories of Muslim and Jewish influence, reconquered from Islamic control, and the new Christian authorities could not assume that all their subjects would suddenly become and remain orthodox Catholics. So the Inquisition in

Portugal and Spain in the late Middle Ages consisted largely of multicultural territories of Muslim and Jewish influence, reconquered from Islamic control, and the new Christian authorities could not assume that all their subjects would suddenly become and remain orthodox Catholics. So the Inquisition in

The Portuguese Inquisition formally started in Portugal in 1536 at the request of King

The Portuguese Inquisition formally started in Portugal in 1536 at the request of King

Some instruments of torture awarded to the Inquisition, actually originated in the

Some instruments of torture awarded to the Inquisition, actually originated in the

Frequently Asked Questions About the Inquisition

by James Hannam

{{Authority control Anti-Islam sentiment in Europe Anti-Judaism Antisemitism in Europe Christianity-related controversies Counter-Reformation Islamophobia in Europe Persecution of Muslims by Christians Tribunals of the Catholic Church Violence against Muslims Ethnic persecution

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

whose aim was to combat heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances

Penance is any act or a set of actions done out of repentance for sins committed, as well as an alternate name for the Catholic, Lutheran, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox sacrament of Reconciliation or Confession. It also plays a part i ...

, but convictions of unrepentant heresy were handed over to the secular courts, which generally resulted in execution or life imprisonment. The Inquisition had its start in the 12th-century Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France ( fro, Reaume de France; frm, Royaulme de France; french: link=yes, Royaume de France) is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the medieval and early modern period ...

, with the aim of combating religious deviation (e.g. apostasy

Apostasy (; grc-gre, ἀποστασία , 'a defection or revolt') is the formal disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of embracing an opinion that ...

or heresy), particularly among the Cathars

Catharism (; from the grc, καθαροί, katharoi, "the pure ones") was a Christian dualist or Gnostic movement between the 12th and 14th centuries which thrived in Southern Europe, particularly in northern Italy and southern France. F ...

and the Waldensians

The Waldensians (also known as Waldenses (), Vallenses, Valdesi or Vaudois) are adherents of a church tradition that began as an ascetic movement within Western Christianity before the Reformation.

Originally known as the "Poor Men of Lyon" in ...

. The inquisitorial courts from this time until the mid-15th century are together known as the Medieval Inquisition. Other groups investigated during the Medieval Inquisition, which primarily took place in France and Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, include the Spiritual Franciscans

The Fraticelli (Italian for "Little Brethren") or Spiritual Franciscans opposed changes to the rule of Saint Francis of Assisi, especially with regard to poverty, and regarded the wealth of the Church as scandalous, and that of individual church ...

, the Hussites

The Hussites ( cs, Husité or ''Kališníci''; "Chalice People") were a Czech proto-Protestant Christian movement that followed the teachings of reformer Jan Hus, who became the best known representative of the Bohemian Reformation.

The Huss ...

, and the Beguines

The Beguines () and the Beghards () were Christian lay religious orders that were active in Western Europe, particularly in the Low Countries, in the 13th–16th centuries. Their members lived in semi-monastic communities but did not take forma ...

. Beginning in the 1250s, inquisitors were generally chosen from members of the Dominican Order

The Order of Preachers ( la, Ordo Praedicatorum) abbreviated OP, also known as the Dominicans, is a Catholic mendicant order of Pontifical Right for men founded in Toulouse, France, by the Spanish priest, saint and mystic Dominic of ...

, replacing the earlier practice of using local clergy as judges.

During the Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Europe, the Renai ...

and the early Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD ...

, the scope of the Inquisition grew significantly in response to the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and ...

and the Catholic Counter-Reformation. During this period, the Inquisition conducted by the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

was known as the Roman Inquisition

The Roman Inquisition, formally the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Roman and Universal Inquisition, was a system of partisan tribunals developed by the Holy See of the Roman Catholic Church, during the second half of the 16th century, respons ...

. The Inquisition also expanded to other European countries, resulting in the Spanish Inquisition

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition ( es, Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición), commonly known as the Spanish Inquisition ( es, Inquisición española), was established in 1478 by the Catholic Monarchs, King Ferdinand ...

and the Portuguese Inquisition

The Portuguese Inquisition ( Portuguese: ''Inquisição Portuguesa''), officially known as the General Council of the Holy Office of the Inquisition in Portugal, was formally established in Portugal in 1536 at the request of its king, John III. ...

. The Spanish and Portuguese Inquisitions were instead focused particularly on the New Christians

New Christian ( es, Cristiano Nuevo; pt, Cristão-Novo; ca, Cristià Nou; lad, Christiano Muevo) was a socio-religious designation and legal distinction in the Spanish Empire and the Portuguese Empire. The term was used from the 15th century ...

or ''Conversos'', as the former Jews who converted to Christianity to avoid antisemitic regulations and persecution were called, the anusim

Anusim ( he, אֲנוּסִים, ; singular male, anús, he, אָנוּס ; singular female, anusáh, , meaning "coerced") is a legal category of Jews in ''halakha'' (Jewish law) who were forced to abandon Judaism against their will, typically ...

(people who were forced to abandon Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in t ...

against their will by violence and threats of expulsion) and on Muslim converts to Catholicism. The scale of the persecution of converted Muslims and converted Jews in Spain and Portugal was the result of suspicions that they had secretly reverted to their previous religions, although both religious minority groups were also more numerous on the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

than in other parts of Europe, as well as the fear of possible rebellions and armed uprisings, as had occurred in previous times.

During this time, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

and Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

operated inquisitorial courts not only in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

, but also throughout their empires in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an are ...

, and the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

. This resulted in the Goa Inquisition

The Goa Inquisition ( pt, Inquisição de Goa) was an extension of the Portuguese Inquisition in Portuguese India. Its objective was to enforce Catholic Orthodoxy and allegiance to the Apostolic See of Rome (Pontifex). The inquisition primaril ...

, the Peruvian Inquisition

The Peruvian Inquisition was established on January 9, 1570 and ended in 1820. The Holy Office and tribunal of the Inquisition were located in Lima, the administrative center of the Viceroyalty of Peru. History

Unlike the Spanish Inquisition and th ...

, and the Mexican Inquisition

The Mexican Inquisition was an extension of the Spanish Inquisition into New Spain. The Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire was not only a political event for the Spanish, but a religious event as well. In the early 16th century, the Reformat ...

, among others.

With the exception of the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

, the institution of the Inquisition was abolished in the early 19th century, after the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

in Europe and the Spanish American wars of independence

The Spanish American wars of independence (25 September 1808 – 29 September 1833; es, Guerras de independencia hispanoamericanas) were numerous wars in Spanish America with the aim of political independence from Spanish rule during the early ...

in the Americas. The institution survived as part of the Roman Curia, but in 1908 it was renamed the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office. In 1965, it became the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith

The Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith (DDF) is the oldest among the departments of the Roman Curia. Its seat is the Palace of the Holy Office in Rome. It was founded to defend the Catholic Church from heresy and is the body responsible ...

. In 2022, this office was renamed the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith.

Definition and purpose

The term "Inquisition" comes from the

The term "Inquisition" comes from the Medieval Latin

Medieval Latin was the form of Literary Latin used in Roman Catholic Western Europe during the Middle Ages. In this region it served as the primary written language, though local languages were also written to varying degrees. Latin functione ...

word , which described any court process based on Roman law

Roman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the '' Corpus Juris Civilis'' (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor Ju ...

, which had gradually come back into use during the Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Europe, the Renai ...

. Today, the English term "Inquisition" can apply to any one of several institutions that worked against heretics

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

(or other offenders against canon law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is th ...

) within the judicial system of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. Although the term "Inquisition" is usually applied to ecclesiastical courts of the Catholic Church, it refers to a judicial process, not an organization. Inquisitors '...were called such because they applied a judicial technique known as ''inquisitio'', which could be translated as "inquiry" or "inquest".' In this process, which was already widely used by secular rulers ( Henry II used it extensively in England in the 12th century), an official inquirer called for information on a specific subject from anyone who felt he or she had something to offer."

The Inquisition, as a church-court, had no jurisdiction over Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

and Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

as such. Generally, the Inquisition was concerned only with the heretical behaviour of Catholic adherents or converts.

The overwhelming majority of sentences seem to have consisted of penances like wearing a cross sewn on one's clothes or going on pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a journey, often into an unknown or foreign place, where a person goes in search of new or expanded meaning about their self, others, nature, or a higher good, through the experience. It can lead to a personal transformation, aft ...

. When a suspect was convicted of unrepentant heresy, canon law required the inquisitorial tribunal to hand the person over to secular authorities for final sentencing. A secular magistrate, the "secular arm", would then determine the penalty based on local law. Those local laws included proscriptions against certain religious crimes, and the punishments included death by burning

Death by burning (also known as immolation) is an execution and murder method involving combustion or exposure to extreme heat. It has a long history as a form of public capital punishment, and many societies have employed it as a punishment f ...

, although the penalty was more usually banishment or imprisonment for life, which was generally commuted after a few years. Thus the inquisitors generally knew the fate which expected anyone so remanded.

The 1578 edition of the Directorium Inquisitorum

The ''Directorium Inquisitorum'' is Nicholas Eymerich's most prominent and enduring work, written in Latin and consisting of approximately 800 pages, which he had composed as early as 1376. Eymerich had written an earlier treatise on sorcery, perh ...

(a standard Inquisitorial manual) spelled out the purpose of inquisitorial penalties: ''... quoniam punitio non refertur primo & per se in correctionem & bonum eius qui punitur, sed in bonum publicum ut alij terreantur, & a malis committendis avocentur'' (translation: "... for punishment does not take place primarily and ''per se'' for the correction and good of the person punished, but for the public good in order that others may become terrified and weaned away from the evils they would commit").

Origin

Before the 12th century, the Catholic Church suppressed what they believed to beheresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

, usually through a system of ecclesiastical proscription or imprisonment, but without using torture,

and seldom resorting to executions. Such punishments were opposed by a number of clergymen and theologians, although some countries punished heresy with the death penalty. Pope Siricius

Pope Siricius (334 – 26 November 399) was the bishop of Rome from December 384 to his death. In response to inquiries from Bishop Himerius of Tarragona, Siricius issued the ''Directa'' decretal, containing decrees of baptism, church discipline ...

, Ambrose of Milan

Ambrose of Milan ( la, Aurelius Ambrosius; ), venerated as Saint Ambrose, ; lmo, Sant Ambroeus . was a theologian and statesman who served as Bishop of Milan from 374 to 397. He expressed himself prominently as a public figure, fiercely promot ...

, and Martin of Tours protested against the execution of Priscillian, largely as an undue interference in ecclesiastical discipline by a civil tribunal. Though widely viewed as a heretic, Priscillian was executed as a sorcerer. Ambrose refused to give any recognition to Ithacius of Ossonuba, "not wishing to have anything to do with bishops who had sent heretics to their death".

In the 12th century, to counter the spread of Catharism, prosecution of heretics became more frequent. The Church charged councils composed of bishops and archbishops with establishing inquisitions (the Episcopal Inquisition). The first Inquisition was temporarily established in Languedoc

The Province of Languedoc (; , ; oc, Lengadòc ) is a former province of France.

Most of its territory is now contained in the modern-day region of Occitanie in Southern France. Its capital city was Toulouse. It had an area of approximately ...

(south of France) in 1184. The murder of Pope Innocent's papal legate Pierre de Castelnau

Pierre de Castelnau (? - died 15 January 1208), French ecclesiastic, made papal legate in 1199 to address the Cathar heresy, he was subsequently murdered in 1208. Following his death Pope Innocent III beatified him by papal order, excommunicated ...

in 1208 sparked the Albigensian Crusade (1209–1229). The Inquisition was permanently established in 1229 ( Council of Toulouse), run largely by the Dominicans in Rome and later at Carcassonne

Carcassonne (, also , , ; ; la, Carcaso) is a French fortified city in the department of Aude, in the region of Occitanie. It is the prefecture of the department.

Inhabited since the Neolithic, Carcassonne is located in the plain of the Au ...

in Languedoc.

Medieval Inquisition

Historians use the term "Medieval Inquisition" to describe the various inquisitions that started around 1184, including the Episcopal Inquisition (1184–1230s) and later the Papal Inquisition (1230s). These inquisitions responded to large popular movements throughout Europe consideredapostate

Apostasy (; grc-gre, ἀποστασία , 'a defection or revolt') is the formal religious disaffiliation, disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of emb ...

or heretical to Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

, in particular the Cathars

Catharism (; from the grc, καθαροί, katharoi, "the pure ones") was a Christian dualist or Gnostic movement between the 12th and 14th centuries which thrived in Southern Europe, particularly in northern Italy and southern France. F ...

in southern France and the Waldensians

The Waldensians (also known as Waldenses (), Vallenses, Valdesi or Vaudois) are adherents of a church tradition that began as an ascetic movement within Western Christianity before the Reformation.

Originally known as the "Poor Men of Lyon" in ...

in both southern France and northern Italy. Other Inquisitions followed after these first inquisition movements. The legal basis for some inquisitorial activity came from Pope Innocent IV

Pope Innocent IV ( la, Innocentius IV; – 7 December 1254), born Sinibaldo Fieschi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 25 June 1243 to his death in 1254.

Fieschi was born in Genoa and studied at the universitie ...

's papal bull ''Ad extirpanda

''Ad extirpanda'' ("To eradicate"; named for its Latin incipit) was a papal bull promulgated on Wednesday, May 15, 1252 by Pope Innocent IV which authorized in limited and defined circumstances the use of torture by the Inquisition as a tool for ...

'' of 1252, which explicitly authorized (and defined the appropriate circumstances for) the use of torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons such as punishment, extracting a confession, interrogational torture, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties. definitions of tortur ...

by the Inquisition for eliciting confessions from heretics. However, Nicholas Eymerich

Nicholas Eymerich ( ca, Nicolau Eimeric) (Girona, ''c.'' 1316 – Girona, 4 January 1399) was a Roman Catholic theologian in Medieval Spain and Inquisitor General of the Inquisition in the Crown of Aragon in the later half of the 14th century. He ...

, the inquisitor who wrote the "Directorium Inquisitorum", stated: 'Quaestiones sunt fallaces et ineficaces' ("interrogations via torture are misleading and futile"). By 1256 inquisitors were given absolution

Absolution is a traditional theological term for the forgiveness imparted by ordained Christian priests and experienced by Christian penitents. It is a universal feature of the historic churches of Christendom, although the theology and the pr ...

if they used instruments of torture.

In the 13th century, Pope Gregory IX

Pope Gregory IX ( la, Gregorius IX; born Ugolino di Conti; c. 1145 or before 1170 – 22 August 1241) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 March 1227 until his death in 1241. He is known for issuing the '' Decre ...

(reigned 1227–1241) assigned the duty of carrying out inquisitions to the Dominican Order

The Order of Preachers ( la, Ordo Praedicatorum) abbreviated OP, also known as the Dominicans, is a Catholic mendicant order of Pontifical Right for men founded in Toulouse, France, by the Spanish priest, saint and mystic Dominic of ...

and Franciscan Order. By the end of the Middle Ages, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

and Castile were the only large western nations without a papal inquisition.

Most inquisitors were friars who taught theology and/or law in the universities. They used inquisitorial procedures, a common legal practice adapted from the earlier Ancient Roman court procedures. They judged heresy along with bishops and groups of "assessors" (clergy serving in a role that was roughly analogous to a jury or legal advisers), using the local authorities to establish a tribunal and to prosecute heretics. After 1200, a Grand Inquisitor

Grand Inquisitor ( la, Inquisitor Generalis, literally ''Inquisitor General'' or ''General Inquisitor'') was the lead official of the Inquisition. The title usually refers to the chief inquisitor of the Spanish Inquisition, even after the reuni ...

headed each Inquisition. Grand Inquisitions persisted until the mid 19th century.

Inquisition in Italy

Only fragmentary data is available for the period before theRoman Inquisition

The Roman Inquisition, formally the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Roman and Universal Inquisition, was a system of partisan tribunals developed by the Holy See of the Roman Catholic Church, during the second half of the 16th century, respons ...

of 1542. In 1276, some 170 Cathars

Catharism (; from the grc, καθαροί, katharoi, "the pure ones") was a Christian dualist or Gnostic movement between the 12th and 14th centuries which thrived in Southern Europe, particularly in northern Italy and southern France. F ...

were captured in Sirmione

Sirmione ( Brescian: ; vec, Sirmion) is a comune in the province of Brescia, in Lombardy (northern Italy). It is bounded by Desenzano del Garda ( Lombardy) and Peschiera del Garda in the province of Verona and the region of Veneto. It has a h ...

, who were then imprisoned in Verona

Verona ( , ; vec, Verona or ) is a city on the Adige River in Veneto, Italy, with 258,031 inhabitants. It is one of the seven provincial capitals of the region. It is the largest city municipality in the region and the second largest in nor ...

, and there, after a two-year trial, on February 13 from 1278, more than a hundred of them were burned. In Orvieto, at the end of 1268/1269, 85 heretics were sentenced, none of whom were executed, but in 18 cases the sentence concerned people who had already died. In Tuscany

it, Toscano (man) it, Toscana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Citizenship

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 = Italian

, demogra ...

, the inquisitor Ruggiero burned at least 11 people in about a year (1244/1245). Excluding the executions of the heretics at Sirmione in 1278, 36 Inquisition executions are documented in the March of Treviso between 1260 and 1308. Ten people were executed in Bologna

Bologna (, , ; egl, label=Emilian language, Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bononia) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400,000 inhabitants and 1 ...

between 1291 and 1310.Paweł Kras: ''Ad abolendam diversarum haeresium pravitatem. System inkwizycyjny w średniowiecznej Europie'', KUL 2006, p. 413. In Piedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

, 22 heretics (mainly Waldensians

The Waldensians (also known as Waldenses (), Vallenses, Valdesi or Vaudois) are adherents of a church tradition that began as an ascetic movement within Western Christianity before the Reformation.

Originally known as the "Poor Men of Lyon" in ...

) were burned in the years 1312-1395 out of 213 convicted. 22 Waldensians were burned in Cuneo

Cuneo (; pms, Coni ; oc, Coni/Couni ; french: Coni ) is a city and ''comune'' in Piedmont, Northern Italy, the capital of the province of Cuneo, the fourth largest of Italy’s provinces by area.

It is located at 550 metres (1,804 ft) in ...

around 1440 and another 5 in the Marquisate of Saluzzo

The Marquisate of Saluzzo () was a historical Italian state that included parts of the current region of Piedmont and of the French Alps. The Marquisate was much older than the Renaissance lordships, being a legacy of the feudalism of the High ...

in 1510. There are also fragmentary records of a good number of executions of people suspected of witchcraft in northern Italy in the 15th and early 16th centuries. Wolfgang Behringer estimates that there could have been as many as two thousand executions. This large number of witches executed was probably because some inquisitors took the view that the crime of witchcraft was exceptional, which meant that the usual rules for heresy trials did not apply to its perpetrators. Many alleged witches were executed even though they were first tried and pleaded guilty, which under normal rules would have meant only canonical sanctions, not death sentences. The episcopal inquisition was also active in suppressing witches. alleged witches; in 1518, judges delegated by the Bishop of Brescia, Paolo Zane, sent some 70 witches from Val Camonica

Val Camonica (also ''Valcamonica'' or Camonica Valley, Eastern Lombard dialect, Eastern Lombard: ''Al Camònega'') is one of the largest valleys of the central Alps, in eastern Lombardy, Italy. It extends about from the Tonale Pass to ...

to the stake.

Inquisition in France

France has the best preserved archives of the medieval inquisition (13th-14th centuries), although they are still very incomplete. The activity of the inquisition in this country was very diverse, both in terms of time and territory. In the first period (1233 to c. 1330), the courts ofLanguedoc

The Province of Languedoc (; , ; oc, Lengadòc ) is a former province of France.

Most of its territory is now contained in the modern-day region of Occitanie in Southern France. Its capital city was Toulouse. It had an area of approximately ...

(Toulouse

Toulouse ( , ; oc, Tolosa ) is the prefecture of the French department of Haute-Garonne and of the larger region of Occitania. The city is on the banks of the River Garonne, from the Mediterranean Sea, from the Atlantic Ocean and from Pa ...

, Carcassonne

Carcassonne (, also , , ; ; la, Carcaso) is a French fortified city in the department of Aude, in the region of Occitanie. It is the prefecture of the department.

Inhabited since the Neolithic, Carcassonne is located in the plain of the Au ...

) are the most active. After 1330 the center of the persecution of heretics shifted to the Alpine regions, while in Languedoc they ceased almost entirely. In northern France, the activity of the Inquisition was irregular throughout this period and, except for the first few years, it was not very intense.

France's first Dominican inquisitor, Robert le Bougre, working in the years 1233-1244, earned a particularly grim reputation. In 1236, Robert burned about 50 people in the area of Champagne and Flanders, and on May 13, 1239, in Montwimer, he burned 183 Cathars. Following Robert's removal from office, Inquisition activity in northern France remained very low. One of the largest trials in the area took place in 1459-1460 at Arras; 34 people were then accused of witchcraft and satanism, 12 of them were burned at the stake.

The main center of the medieval inquisition was undoubtedly the Languedoc. The first inquisitors were appointed there in 1233, but due to strong resistance from local communities in the early years, most sentences concerned dead heretics, whose bodies were exhumed and burned. Actual executions occurred sporadically and, until the fall of the fortress of Montsegur (1244), probably accounted for no more than 1% of all sentences. In addition to the cremation of the remains of the dead, a large percentage were also sentences in absentia and penances imposed on heretics who voluntarily confessed their faults (for example, in the years 1241-1242 the inquisitor Pierre Ceila reconciled 724 heretics with the Church). Inquisitor Ferrier of Catalonia, investigating Montauban between 1242 and 1244, questioned about 800 people, of whom he sentenced 6 to death and 20 to prison. Between 1243 and 1245, Bernard de Caux handed down 25 sentences of imprisonment and confiscation of property in Agen and Cahors. After the fall of Montsegur and the seizure of power in Toulouse by Count Alfonso de Poitiers, the percentage of death sentences increased to around 7% and remained at this level until the end of the Languedoc Inquisition around from 1330. Between 1245 and 1246, the inquisitor Bernard de Caux carried out a large-scale investigation in the area of Lauragais

The Lauragais () is an area of the south-west of France that is south-east of Toulouse.

The Lauragais, a former county in the south-west of France, takes its name from the town of Laurac and has a large area. It covers both sides of the Canal ...

and Lavaur. He covered 39 villages, and probably all the adult inhabitants (5,471 people) were questioned, of whom 207 were found guilty of heresy. Of these 207, no one was sentenced to death, 23 were sentenced to prison and 184 to penance. Between 1246 and 1248, the inquisitors Bernard de Caux and Jean de Saint-Pierre handed down 192 sentences in Toulouse, of which 43 were sentences in absentia and 149 were prison sentences. In Pamiers in 1246/1247 there were 7 prison sentences 01and in Limoux in the county of Foix 156 people were sentenced to carry crosses. Between 1249 and 1257, in Toulouse, the Inquisition handed down 306 sentences, without counting the penitential sentences imposed during "times of grace". 21 people were sentenced to death, 239 to prison, in addition, 30 people were sentenced in absentia and 11 posthumously; In another five cases the type of sanction is unknown, but since they all involve repeat offenders, only prison or burning is at stake. Between 1237 and 1279, at least 507 convictions were passed in Toulouse (most in absentia or posthumously) resulting in the confiscation of property; in Albi between 1240 and 1252 there were 60 sentences of this type.

The activities of Bernard Gui, inquisitor of Toulouse from 1307 to 1323, are better documented, as a complete record of his trials has been preserved. During the entire period of his inquisitorial activity, he handed down 633 sentences against 602 people (31 repeat offenders), including:

* 41 death sentences,

* 40 convictions of fugitive heretics (in absentia),

* 20 sentences against people who died before the end of the trial (3 of them Bernardo considered unrepentant, and his remains were burned at the stake),

* 69 exhumation orders for the remains of dead heretics (66 of whom were subsequently burned),

* 308 prison sentences,

* 136 orders to carry crosses,

* 18 mandates to make a pilgrimage (17) or participate in a crusade (1),

* in one case, sentencing was postponed.

In addition, Bernard Gui

Bernard Gui (), also known as Bernardo Gui or Bernardus Guidonis (c. 1261/62 – 30 December 1331), was a Dominican friar, Bishop of Lodève, and a papal inquisitor during the later stages of the Medieval Inquisition.

Due to his fictionali ...

issued 274 more sentences involving the mitigation of sentences already served to convicted heretics; in 139 cases he exchanged prison for carrying crosses, and in 135 cases, carrying crosses for pilgrimage. To the full statistics, there are 22 orders to demolish houses used by heretics as meeting places and one condemnation and burning of Jewish writings (including commentaries on the Torah).List of judgments from: James Given: ''Inquisition and Medieval Society'', Cornell University Press, 2001, s. 69–70.

The episcopal inquisition was also active in Languedoc. In the years 1232–1234, the Bishop of Toulouse, Raymond, sentenced several dozen Cathars to death. In turn, Bishop Jacques Fournier

Pope Benedict XII ( la, Benedictus XII, french: Benoît XII; 1285 – 25 April 1342), born Jacques Fournier, was head of the Catholic Church from 30 December 1334 to his death in April 1342. He was the third Avignon pope. Benedict was a careful ...

of Pamiers

Pamiers (; oc, Pàmias ) is a commune and largest city in the Ariège department in the Occitanie region in southwestern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department. It is the most populous commune in the Ariège department, although i ...

in the years 1318-1325 conducted an investigation against 89 people, of whom 64 were found guilty and 5 were sentenced to death.

After 1330, the center of activity of the French Inquisition moved east, to the Alpine regions, where there were numerous Waldensian communities. The repression against them was not continuous and was very ineffective. Data on sentences issued by inquisitors are fragmentary. In 1348, 12 Waldensians were burned in Embrun, and in 1353/1354 as many as 168 received penances. In general, however, few Waldensians fell into the hands of the Inquisition, for they took refuge in hard-to-reach mountainous regions, where they formed close-knit communities. Inquisitors operating in this region, in order to be able to conduct trials, often had to resort to the armed assistance of local secular authorities (e.g. military expeditions in 1338–1339 and 1366). In the years 1375–1393 (with some breaks), the Dauphiné was the scene of the activities of the inquisitor Francois Borel, who gained an extremely gloomy reputation among the locals. It is known that on July 1, 1380, he pronounced death sentences in absentia against 169 people, including 108 from the Valpute valley, 32 from Argentiere and 29 from Freyssiniere. It is not known how many of them were actually carried out, only six people captured in 1382 are confirmed to be executed.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, major trials took place only sporadically, e.g. against the Waldensians in Delphinate in 1430–1432 (no numerical data) and 1532–1533 (7 executed out of about 150 tried) or the aforementioned trial in Arras 1459–1460 . In the 16th century, the jurisdiction of the Inquisition in the kingdom of France was effectively limited to clergymen, while local parliaments took over the jurisdiction of the laity. Between 1500 and 1560, 62 people were burned for heresy in the Languedoc, all of whom were convicted by the Parliament of Toulouse.

Between 1657 and 1659, twenty-two alleged witches were burned on the orders of the inquisitor Pierre Symard in the province of Franche-Comte, then part of the Empire.

The inquisitorial tribunal in papal Avignon, established in 1541, passed 855 death sentences, almost all of them (818) in the years 1566–1574, but the vast majority of them were pronounced in absentia.

Inquisition in Germany

The Rhineland and Thuringia in the years 1231-1233 were the field of activity of the notorious inquisitor Konrad of Marburg. Unfortunately, the documentation of his trials has not been preserved, making it impossible to determine the number of his victims. The chronicles only mention "many" heretics that he burned. The only concrete information is about the burning of four people in Erfurt in May 1232. After the murder of Konrad of Marburg, burning at the stake in Germany was virtually unknown for the next 80 years. It was not until the early fourteenth century that stronger measures were taken against heretics, largely at the initiative of bishops. In the years 1311-1315, numerous trials were held against the Waldensians in Austria, resulting in the burning of at least 39 people, according to incomplete records. In 1336, inAngermünde

Angermünde () is a town in the district of Uckermark in the state of Brandenburg, Germany. It is about northeast of Berlin, the capital of Germany.

The population is about 14,000, but has been declining since its traditional industrial base, ...

, in the diocese of Brandenburg, another 14 heretics were burned.

The number of those convicted by the papal inquisitors was smaller. Walter Kerlinger burned 10 begards in Erfurt

Erfurt () is the capital and largest city in the Central German state of Thuringia. It is located in the wide valley of the Gera river (progression: ), in the southern part of the Thuringian Basin, north of the Thuringian Forest. It sits i ...

and Nordhausen in 1368-1369. In turn, Eylard Schöneveld burned a total of four people in various Baltic cities in 1402-1403.

In the last decade of the 14th century, episcopal inquisitors carried out large-scale operations against heretics in eastern Germany, Pomerania, Austria, and Hungary. In Pomerania, of 443 sentenced in the years 1392-1394 by the inquisitor Peter Zwicker, the provincial of the Celestinians, none went to the stake, because they all submitted to the Church. Bloodier were the trials of the Waldensians in Austria in 1397, where more than a hundred Waldensians were burned at the stake. However, it seems that in these trials the death sentences represented only a small percentage of all the sentences, because according to the account of one of the inquisitors involved in these repressions, the number of heretics reconciled with the Church from Thuringia to Hungary amounted to about 2,000.

In 1414, the inquisitor Heinrich von Schöneveld arrested 84 flagellants in Sangerhausen

Sangerhausen () is a town in Saxony-Anhalt, central Germany, capital of the district of Mansfeld-Südharz. It is situated southeast of the Harz, approx. east of Nordhausen, and west of Halle (Saale). About 26,000 people live in Sangerhausen ( ...

, of whom he burned 3 leaders, and imposed penitential sentences on the rest. However, since this sect was associated with the peasant revolts in Thuringia from 1412, after the departure of the inquisitor, the local authorities organized a mass hunt for flagellants and, regardless of their previous verdicts, sent at least 168 to the stake (possibly up to 300) people. Inquisitor Friedrich Müller (d. 1460) sentenced to death 12 of the 13 heretics he had tried in 1446 at Nordhausen. In 1453 the same inquisitor burned 2 heretics in Göttingen

Göttingen (, , ; nds, Chöttingen) is a university city in Lower Saxony, central Germany, the capital of the eponymous district. The River Leine runs through it. At the end of 2019, the population was 118,911.

General information

The ori ...

.

Inquisitor Heinrich Kramer

Heinrich Kramer ( 1430 – 1505, aged 74-75), also known under the Latinized name Henricus Institor, was a German churchman and inquisitor. With his widely distributed book ''Malleus Maleficarum'' (1487), which describes witchcraft and endorse ...

, author of the Malleus Maleficarum

The ''Malleus Maleficarum'', usually translated as the ''Hammer of Witches'', is the best known treatise on witchcraft. It was written by the German Catholic clergyman Heinrich Kramer (under his Latinized name ''Henricus Institor'') and first ...

, in his own words, sentenced 48 people to the stake in five years (1481-1486). Jacob Hoogstraten, inquisitor of Cologne from 1508 to 1527, sentenced four people to be burned at the stake.

Inquisition in Hungary and the Balkans

Very little is known about the activities of the inquisition in Hungary and the countries under its influence (Bosnia, Croatia), as there are few sources about this activity. Numerous conversions and executions of Bosnian Cathars are known to have taken place around 1239/40, and in 1268 the Dominican inquisitor Andrew reconciled many heretics with the Church in the town of Skradin, but precise figures are unknown. The border areas with Bohemia and Austria were under major inquisitorial action against the Waldensians in the early 15th century. In addition, in the years 1436-1440 in the Kingdom of Hungary, the Franciscan Jacobo de la Marcha acted as an inquisitor... his mission was mixed, preaching and inquisitorial. The correspondence preserved between James, his collaborators, the Hungarian bishops and Pope Eugene IV shows that he reconciled up to 25,000 people with the Church. This correspondence also shows that he punished recalcitrant heretics with death, and in 1437 numerous executions were carried out in the diocese of Sirmium, although the number of those executed is also unknown.Inquisition in the Czech Republic and Poland

In Bohemia and Poland, the inquisition was established permanently in 1318, although anti-heretical repressions were carried out as early as 1315 in the episcopal inquisition, when more than 50 Waldensians were burned in various Silesian cities. The fragmentary surviving protocols of the investigations carried out by the Prague inquisitor Gallus de Neuhaus in the years 1335 to around 1353 mention 14 heretics burned out of almost 300 interrogated, but it is estimated that the actual number executed could have been even more than 200. , and the entire process was covered to varying degrees by some 4,400 people. In the lands belonging to the Kingdom of Poland little is known of the activities of the Inquisition until the appearance of the Hussite heresy in the 15th century. Polish courts of the inquisition in the fight against this heresy issued at least 8 death sentences for some 200 trials carried out. There are 558 court cases finished with conviction researched in Poland from XV to XVIII centuries.Early modern European history

With the sharpening of debate and of conflict between theProtestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and ...

and the Catholic Counter-Reformation, Protestant societies came to see/use the Inquisition as a terrifying "Other

Other often refers to:

* Other (philosophy), a concept in psychology and philosophy

Other or The Other may also refer to:

Film and television

* ''The Other'' (1913 film), a German silent film directed by Max Mack

* ''The Other'' (1930 film), a ...

", while staunch Catholics regarded the Holy Office as a necessary bulwark against the spread of reprehensible heresies.

Witch-trials

witchcraft

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have ...

, and persecutions directed at or excused by it, were widespread in pre-Christian Europe, and reflected in Germanic law

Germanic law is a scholarly term used to described a series of commonalities between the various law codes (the ''Leges Barbarorum'', 'laws of the barbarians', also called Leges) of the early Germanic peoples. These were compared with statements ...

, the influence of the Church in the early medieval era resulted in the revocation of these laws in many places, bringing an end to traditional pagan witch hunts. Throughout the medieval era, mainstream Christian teaching had denied the existence of witches and witchcraft, condemning it as pagan superstition. However, Christian influence on popular beliefs in witches and ''maleficium'' (harm committed by magic) failed to entirely eradicate folk belief in witches.

The fierce denunciation and persecution of supposed sorceresses that characterized the cruel witchhunts of a later age were not generally found in the first thirteen hundred years of the Christian era.Thurston, Herber"Witchcraft."

''The Catholic Encyclopedia'', Vol. 15. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 12 Jul. 2015 The medieval Church distinguished between "white" and "black" magic. Local folk practice often mixed chants, incantations, and prayers to the appropriate patron saint to ward off storms, to protect cattle, or ensure a good harvest. Bonfires on Midsummer's Eve were intended to deflect natural catastrophes or the influence of fairies, ghosts, and witches. Plants, often harvested under particular conditions, were deemed effective in healing. Black magic was that which was used for a malevolent purpose. This was generally dealt with through confession, repentance, and charitable work assigned as penance. Early Irish canons treated sorcery as a crime to be visited with

excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

until adequate penance had been performed. In 1258, Pope Alexander IV

Pope Alexander IV (1199 or 1185 – 25 May 1261) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 12 December 1254 to his death in 1261.

Early career

He was born as Rinaldo di Jenne in Jenne (now in the Province of Rome), he ...

ruled that inquisitors should limit their involvement to those cases in which there was some clear presumption of heretical belief.

The prosecution of witchcraft generally became more prominent in the late medieval and Renaissance era, perhaps driven partly by the upheavals of the era – the Black Death, the Hundred Years War, and a gradual cooling of the climate that modern scientists call the Little Ice Age (between about the 15th and 19th centuries). Witches were sometimes blamed. Since the years of most intense witch-hunting largely coincide with the age of the Reformation, some historians point to the influence of the Reformation on the European witch-hunt.

Dominican priest Heinrich Kramer

Heinrich Kramer ( 1430 – 1505, aged 74-75), also known under the Latinized name Henricus Institor, was a German churchman and inquisitor. With his widely distributed book ''Malleus Maleficarum'' (1487), which describes witchcraft and endorse ...

was assistant to the Archbishop of Salzburg. In 1484 Kramer requested that Pope Innocent VIII clarify his authority to prosecute witchcraft in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, where he had been refused assistance by the local ecclesiastical authorities. They maintained that Kramer could not legally function in their areas.

The papal bull ''Summis desiderantes affectibus

(Latin for "desiring with supreme ardor"), sometimes abbreviated to was a papal bull regarding witchcraft issued by Pope Innocent VIII on 5 December 1484.

Witches and the Church

Belief in witchcraft is ancient. in the Hebrew Bible states: ...

'' sought to remedy this jurisdictional dispute by specifically identifying the dioceses of Mainz, Köln, Trier, Salzburg, and Bremen. Some scholars view the bull as "clearly political". The bull failed to ensure that Kramer obtained the support he had hoped for. In fact he was subsequently expelled from the city of Innsbruck by the local bishop, George Golzer, who ordered Kramer to stop making false accusations. Golzer described Kramer as senile in letters written shortly after the incident. This rebuke led Kramer to write a justification of his views on witchcraft in his 1486 book ''Malleus Maleficarum

The ''Malleus Maleficarum'', usually translated as the ''Hammer of Witches'', is the best known treatise on witchcraft. It was written by the German Catholic clergyman Heinrich Kramer (under his Latinized name ''Henricus Institor'') and first ...

'' ("Hammer against witches"). In the book, Kramer stated his view that witchcraft was to blame for bad weather. The book is also noted for its animus against women. Despite Kramer's claim that the book gained acceptance from the clergy at the University of Cologne

The University of Cologne (german: Universität zu Köln) is a university in Cologne, Germany. It was established in the year 1388 and is one of the most prestigious and research intensive universities in Germany. It was the sixth university to ...

, it was in fact condemned by the clergy at Cologne for advocating views that violated Catholic doctrine and standard inquisitorial procedure. In 1538 the Spanish Inquisition cautioned its members not to believe everything the ''Malleus'' said.

Spanish Inquisition

Portugal and Spain in the late Middle Ages consisted largely of multicultural territories of Muslim and Jewish influence, reconquered from Islamic control, and the new Christian authorities could not assume that all their subjects would suddenly become and remain orthodox Catholics. So the Inquisition in

Portugal and Spain in the late Middle Ages consisted largely of multicultural territories of Muslim and Jewish influence, reconquered from Islamic control, and the new Christian authorities could not assume that all their subjects would suddenly become and remain orthodox Catholics. So the Inquisition in Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

, in the lands of the Reconquista

The ' (Spanish, Portuguese and Galician for "reconquest") is a historiographical construction describing the 781-year period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the Nasrid ...

counties and kingdoms like León, Castile, and Aragon, had a special socio-political basis as well as more fundamental religious motives.

In some parts of Spain towards the end of the 14th century, there was a wave of violent anti-Judaism

Anti-Judaism is the "total or partial opposition to Judaism as a religion—and the total or partial opposition to Jews as adherents of it—by persons who accept a competing system of beliefs and practices and consider certain genuine Judai ...

, encouraged by the preaching of Ferrand Martínez

Ferrand Martinez (fl. 14th century) was a Spanish cleric and archdeacon of Écija, most noted for being an antisemitic agitator whom historians cite as the prime mover behind the series of pogroms against the Spanish Jews in 1391, beginning in the ...

, Archdeacon of Écija

Écija () is a city and municipality of Spain belonging to the province of Seville, in the autonomous community of Andalusia. It is in the countryside, 85 km east of the city of Seville. According to the 2008 census, Écija had a total populat ...

. In the pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russia ...

s of June 1391 in Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula ...

, hundreds of Jews were killed, and the synagogue was completely destroyed. The number of people killed was also high in other cities, such as Córdoba, Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. The wider urban area al ...

, and Barcelona.

One of the consequences of these pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russia ...

s was the mass conversion of thousands of surviving Jews. Forced baptism was contrary to the law of the Catholic Church, and theoretically anybody who had been forcibly baptized could legally return to Judaism. However, this was very narrowly interpreted. Legal definitions of the time theoretically acknowledged that a forced baptism was not a valid sacrament, but confined this to cases where it was literally administered by physical force. A person who had consented to baptism under threat of death or serious injury was still regarded as a voluntary convert, and accordingly forbidden to revert to Judaism. After the public violence, many of the converted "felt it safer to remain in their new religion". Thus, after 1391, a new social group appeared and were referred to as ''conversos

A ''converso'' (; ; feminine form ''conversa''), "convert", () was a Jew who converted to Catholicism in Spain or Portugal, particularly during the 14th and 15th centuries, or one of his or her descendants.

To safeguard the Old Christian p ...

'' or ''New Christians''.

King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile established the Spanish Inquisition

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition ( es, Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición), commonly known as the Spanish Inquisition ( es, Inquisición española), was established in 1478 by the Catholic Monarchs, King Ferdinand ...

in 1478. In contrast to the previous inquisitions, it operated completely under royal Christian authority, though staffed by clergy and orders, and independently of the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

. It operated in Spain and in most Spanish colonies and territories, which included the Canary Islands, the Kingdom of Sicily, and all Spanish possessions in North, Central, and South America. It primarily focused upon forced converts from Islam (Morisco

Moriscos (, ; pt, mouriscos ; Spanish for "Moorish") were former Muslims and their descendants whom the Roman Catholic church and the Spanish Crown commanded to convert to Christianity or face compulsory exile after Spain outlawed the open ...

s, Conversos and ''secret Moors'') and from Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in t ...

( Conversos, Crypto-Jews

Crypto-Judaism is the secret adherence to Judaism while publicly professing to be of another faith; practitioners are referred to as "crypto-Jews" (origin from Greek ''kryptos'' – , 'hidden').

The term is especially applied historically to Sp ...

and Marranos)—both groups still resided in Spain after the end of the Islamic control of Spain—who came under suspicion of either continuing to adhere to their old religion or of having fallen back into it.

All Jews who had not converted were expelled from Spain in 1492, and all Muslims ordered to convert in different stages starting in 1501. Those who converted or simply remained after the relevant edict became nominally, and legally Catholics and thus subject to the Inquisition.

Inquisition in the Spanish overseas empire

In the Americas, King Philip II of Spain set up three tribunals (each formally titled ''Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición'') in 1569, one inMexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

, Cartagena de Indias (in modern-day Colombia) and Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = National seal

, national_motto = "Firm and Happy f ...

. The Mexican office administered Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

(central and southeastern Mexico), Nueva Galicia

Nuevo Reino de Galicia (''New Kingdom of Galicia'', gl, Reino de Nova Galicia) or simply Nueva Galicia (''New Galicia'', ''Nova Galicia'') was an autonomous kingdom of the Viceroyalty of New Spain. It was named after Galicia in Spain. Nueva ...

(northern and western Mexico), the Audiencias of Guatemala (Guatemala, Chiapas, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica), and the Spanish East Indies

The Spanish East Indies ( es , Indias orientales españolas ; fil, Silangang Indiyas ng Espanya) were the overseas territories of the Spanish Empire in Asia and Oceania from 1565 to 1898, governed for the Spanish Crown from Mexico City and Madri ...

. The Peruvian Inquisition

The Peruvian Inquisition was established on January 9, 1570 and ended in 1820. The Holy Office and tribunal of the Inquisition were located in Lima, the administrative center of the Viceroyalty of Peru. History

Unlike the Spanish Inquisition and th ...

, based in Lima, administered all the Spanish territories in South America and Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Co ...

.

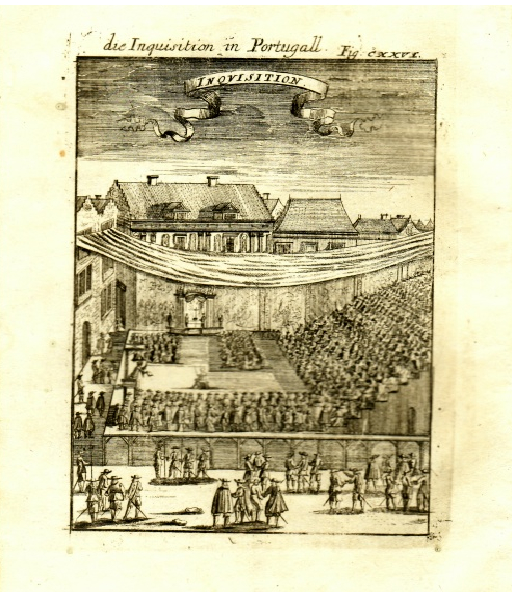

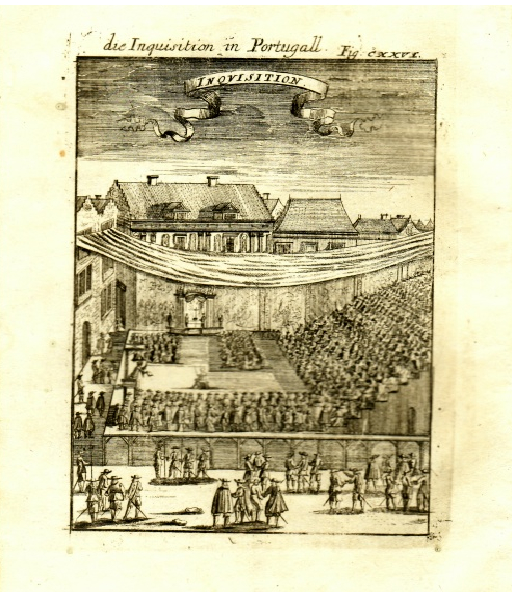

Portuguese Inquisition

The Portuguese Inquisition formally started in Portugal in 1536 at the request of King

The Portuguese Inquisition formally started in Portugal in 1536 at the request of King João III

John III ( pt, João III ; 7 June 1502 – 11 June 1557), nicknamed The Pious ( Portuguese: ''o Piedoso''), was the King of Portugal and the Algarves from 1521 until his death in 1557. He was the son of King Manuel I and Maria of Aragon, the t ...

. Manuel I Manuel I may refer to:

* Manuel I Komnenos, Byzantine emperor (1143–1180)

*Manuel I of Trebizond, Emperor of Trebizond (1228–1263)

*Manuel I of Portugal

Manuel I (; 31 May 146913 December 1521), known as the Fortunate ( pt, O Venturoso), wa ...

had asked Pope Leo X

Pope Leo X ( it, Leone X; born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, 11 December 14751 December 1521) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 March 1513 to his death in December 1521.

Born into the prominent political an ...

for the installation of the Inquisition in 1515, but only after his death in 1521 did Pope Paul III acquiesce. At its head stood a ''Grande Inquisidor'', or General Inquisitor, named by the Pope but selected by the Crown, and always from within the royal family. The Portuguese Inquisition principally focused upon the Sephardi Jews

Sephardic (or Sephardi) Jews (, ; lad, Djudíos Sefardíes), also ''Sepharadim'' , Modern Hebrew: ''Sfaradim'', Tiberian: Səp̄āraddîm, also , ''Ye'hude Sepharad'', lit. "The Jews of Spain", es, Judíos sefardíes (or ), pt, Judeus sefa ...

, whom the state forced to convert to Christianity. Spain had expelled its Sephardi population in 1492; many of these Spanish Jews left Spain for Portugal but eventually were subject to inquisition there as well.

The Portuguese Inquisition held its first ''auto-da-fé'' in 1540. The Portuguese inquisitors mostly focused upon the Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

ish New Christians

New Christian ( es, Cristiano Nuevo; pt, Cristão-Novo; ca, Cristià Nou; lad, Christiano Muevo) was a socio-religious designation and legal distinction in the Spanish Empire and the Portuguese Empire. The term was used from the 15th century ...

(i.e. ''conversos

A ''converso'' (; ; feminine form ''conversa''), "convert", () was a Jew who converted to Catholicism in Spain or Portugal, particularly during the 14th and 15th centuries, or one of his or her descendants.

To safeguard the Old Christian p ...

'' or ''marranos

Marranos were Spanish and Portuguese Jews living in the Iberian Peninsula who converted or were forced to convert to Christianity during the Middle Ages, but continued to practice Judaism in secrecy.

The term specifically refers to the cha ...

''). The Portuguese Inquisition expanded its scope of operations from Portugal to its colonial possessions, including Brazil, Cape Verde, and Goa

Goa () is a state on the southwestern coast of India within the Konkan region, geographically separated from the Deccan highlands by the Western Ghats. It is located between the Indian states of Maharashtra to the north and Karnataka to the ...

. In the colonies, it continued as a religious court, investigating and trying cases of breaches of the tenets of orthodox Catholicism until 1821. King João III

John III ( pt, João III ; 7 June 1502 – 11 June 1557), nicknamed The Pious ( Portuguese: ''o Piedoso''), was the King of Portugal and the Algarves from 1521 until his death in 1557. He was the son of King Manuel I and Maria of Aragon, the t ...

(reigned 1521–57) extended the activity of the courts to cover censorship

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by governments ...

, divination, witchcraft

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have ...

, and bigamy

In cultures where monogamy is mandated, bigamy is the act of entering into a marriage with one person while still legally married to another. A legal or de facto separation of the couple does not alter their marital status as married persons. I ...

. Originally oriented for a religious action, the Inquisition exerted an influence over almost every aspect of Portuguese society: political, cultural, and social.

According to Henry Charles Lea, between 1540 and 1794, tribunals in Lisbon, Porto

Porto or Oporto () is the second-largest city in Portugal, the capital of the Porto District, and one of the Iberian Peninsula's major urban areas. Porto city proper, which is the entire municipality of Porto, is small compared to its metropol ...

, Coimbra

Coimbra (, also , , or ) is a city and a municipality in Portugal. The population of the municipality at the 2011 census was 143,397, in an area of .

The fourth-largest urban area in Portugal after Lisbon, Porto, and Braga, it is the largest cit ...

, and Évora

Évora ( , ) is a city and a municipality in Portugal. It has 53,591 inhabitants (2021), in an area of 1307.08 km2. It is the historic capital of the Alentejo and serves as the seat of the Évora District.

Due to its well-preserved old ...

resulted in the burning of 1,175 persons, the burning of another 633 in effigy, and the penancing of 29,590. But documentation of 15 out of 689 autos-da-fé has disappeared, so these numbers may slightly understate the activity.

Inquisition in the Portuguese overseas empire

= Goa Inquisition

= TheGoa Inquisition

The Goa Inquisition ( pt, Inquisição de Goa) was an extension of the Portuguese Inquisition in Portuguese India. Its objective was to enforce Catholic Orthodoxy and allegiance to the Apostolic See of Rome (Pontifex). The inquisition primaril ...

began in 1560 at the order of John III of Portugal. It had originally been requested in a letter in the 1540s by Jesuit priest Francis Xavier

Francis Xavier (born Francisco de Jasso y Azpilicueta; Latin: ''Franciscus Xaverius''; Basque: ''Frantzisko Xabierkoa''; French: ''François Xavier''; Spanish: ''Francisco Javier''; Portuguese: ''Francisco Xavier''; 7 April 15063 December ...

, because of the New Christian

New Christian ( es, Cristiano Nuevo; pt, Cristão-Novo; ca, Cristià Nou; lad, Christiano Muevo) was a socio-religious designation and legal distinction in the Spanish Empire and the Portuguese Empire. The term was used from the 15th century ...

s who had arrived in Goa and then reverted to Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in t ...

. The Goa Inquisition also focused upon Catholic converts from Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

or Islam who were thought to have returned to their original ways. In addition, this inquisition prosecuted non-converts who broke prohibitions against the public observance of Hindu

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

or Muslim rites or interfered with Portuguese attempts to convert non-Christians to Catholicism.Salomon, H. P. and Sassoon, I. S. D., in Saraiva, Antonio Jose. ''The Marrano Factory. The Portuguese Inquisition and Its New Christians, 1536–1765'' (Brill, 2001), pgs. 345-7 Aleixo Dias Falcão and Francisco Marques set it up in the palace of the Sabaio Adil Khan.

= Brazilian Inquisition

= Theinquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

was active in colonial Brazil. The religious mystic and formerly enslaved prostitute, Rosa Egipcíaca

Rosa Egipcíaca, also known as Rosa Maria Egipcíaca of Vera Cruz and Rosa Courana (1719 – 12 October 1771), was a formerly enslaved writer and religious mystic, who was the author of '' A Sagrada Teologia do Amor de Deus Luz Brilhante das Alma ...

was arrested, interrogated and imprisoned, both in the colony and in Lisbon. Egipcíaca was the first black woman in Brazil to write a book - this work detailed her visions and was entitled ''Sagrada Teologia do Amor Divino das Almas Peregrinas Sagrada is a Spanish word meaning "sacred".

It may refer to:

*Sagrada, Missouri, a community in the United States

* La Sagrada Família, a church in Barcelona, Spain

*Rhamnus purshiana

''Frangula purshiana'' (cascara, cascara buckthorn, cascara ...

.''

Roman Inquisition

With theProtestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and ...

, Catholic authorities became much more ready to suspect heresy in any new ideas,

including those of Renaissance humanism

Renaissance humanism was a revival in the study of classical antiquity, at first in Italy and then spreading across Western Europe in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. During the period, the term ''humanist'' ( it, umanista) referred to teache ...

, previously strongly supported by many at the top of the Church hierarchy. The extirpation of heretics became a much broader and more complex enterprise, complicated by the politics of territorial Protestant powers, especially in northern Europe. The Catholic Church could no longer exercise direct influence in the politics and justice-systems of lands that officially adopted Protestantism. Thus war (the French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion is the term which is used in reference to a period of civil war between French Catholics and Protestants, commonly called Huguenots, which lasted from 1562 to 1598. According to estimates, between two and four mi ...

, the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of battle ...

), massacre (the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre) and the missional and propaganda work (by the ''Sacra congregatio de propaganda fide

Sacra may refer to :

* '' Bibliotheca Sacra'', the theological journal published by Dallas Theological Seminary

* '' Harmonia Sacra'', a Mennonite shape note hymn and tune book

* Isola Sacra, an island in the Lazio region of Italy south of Rome

* ...

'') of the Counter-Reformation came to play larger roles in these circumstances, and the Roman law

Roman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the '' Corpus Juris Civilis'' (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor Ju ...

type of a "judicial" approach to heresy represented by the Inquisition became less important overall. In 1542 Pope Paul III established the Congregation of the Holy Office of the Inquisition as a permanent congregation staffed with cardinals

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**''Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, the ...

and other officials. It had the tasks of maintaining and defending the integrity of the faith and of examining and proscribing errors and false doctrines; it thus became the supervisory body of local Inquisitions. A famous case tried by the Roman Inquisition was that of Galileo Galilei in 1633.

The penances and sentences for those who confessed or were found guilty were pronounced together in a public ceremony at the end of all the processes. This was the ''sermo generalis'' or ''auto-da-fé

An ''auto-da-fé'' ( ; from Portuguese , meaning 'act of faith'; es, auto de fe ) was the ritual of public penance carried out between the 15th and 19th centuries of condemned heretics and apostates imposed by the Spanish, Portuguese, or Mexi ...

''. Penances (not matters for the civil authorities) might consist of a pilgrimage, a public scourging, a fine, or the wearing of a cross. The wearing of two tongues of red or other brightly colored cloth, sewn onto an outer garment in an "X" pattern, marked those who were under investigation. The penalties in serious cases were confiscation of property by the Inquisition or imprisonment. This led to the possibility of false charges to enable confiscation being made against those over a certain income, particularly rich ''marranos

Marranos were Spanish and Portuguese Jews living in the Iberian Peninsula who converted or were forced to convert to Christianity during the Middle Ages, but continued to practice Judaism in secrecy.

The term specifically refers to the cha ...