Indian removals in Indiana on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Indian removals in Indiana followed a series of the land cession treaties made between 1795 and 1846 that led to the removal of most of the native tribes from

Indian removals in Indiana followed a series of the land cession treaties made between 1795 and 1846 that led to the removal of most of the native tribes from

The

The

In 1818

In 1818  Under the terms of the Treaty of St. Mary's, the

Under the terms of the Treaty of St. Mary's, the

Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th ...

. Some of the removals occurred prior to 1830, but most took place between 1830 and 1846. The Lenape

The Lenape (, , or Lenape , del, Lënapeyok) also called the Leni Lenape, Lenni Lenape and Delaware people, are an indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, who live in the United States and Canada. Their historical territory inclu ...

(Delaware), Piankashaw, Kickapoo, Wea, and Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

were removed in the 1820s and 1830s, but the Potawatomi

The Potawatomi , also spelled Pottawatomi and Pottawatomie (among many variations), are a Native American people of the western Great Lakes region, upper Mississippi River and Great Plains. They traditionally speak the Potawatomi language, a m ...

and Miami

Miami ( ), officially the City of Miami, known as "the 305", "The Magic City", and "Gateway to the Americas", is a coastal metropolis and the county seat of Miami-Dade County in South Florida, United States. With a population of 442,241 at ...

removals in the 1830s and 1840s were more gradual and incomplete, and not all of Indiana's Native Americans voluntarily left the state. The most well-known resistance effort in Indiana was the forced removal of Chief Menominee and his Yellow River band of Potawatomi in what became known as the Potawatomi Trail of Death

The Potawatomi Trail of Death was the forced removal by militia in 1838 of about 859 members of the Potawatomi nation from Indiana to reservation lands in what is now eastern Kansas.

The march began at Twin Lakes, Indiana (Myers Lake and Cook ...

in 1838, in which 859 Potawatomi were removed to Kansas

Kansas () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its Capital city, capital is Topeka, Kansas, Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita, Kansas, Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebras ...

and at least forty died on the journey west. The Miami were the last to be removed from Indiana, but tribal leaders delayed the process until 1846. Many of the Miami were permitted to remain on land allotments guaranteed to them under the Treaty of St. Mary's (1818) and subsequent treaties.

Between 1803 and 1809, future President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

negotiated more than a dozen treaties on behalf of the federal government

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government ( federalism). In a federation, the self-gover ...

that purchased nearly all the Indian-owned land in most of present-day Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

and the southern third of Indiana from various tribes. Most of the Wea and the Kickapoo were removed west to Illinois and Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

after 1813. The Treaty of St. Mary's led to the removal of the Delaware, in 1820, and the remaining Kickapoo, who removed west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

. After the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is Bicameralism, bicameral, composed of a lower body, the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives, and an upper body, ...

passed the Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for ...

(1830), removals in Indiana became part of a larger nationwide effort that was carried out under President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

's administration. Most of the tribes had already removed from the state. The only major tribes remaining in Indiana were the Miami and the Potawatomi, and both of them were already confined to reservation lands under the terms of previous treaties. Between 1832 and 1837 the Potawatomi ceded their Indiana land and agreed to remove to reservations in Kansas. A small group joined the Potawatomi in Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

. Between 1834 and 1846 the Miami ceded their reservation land in Indiana and agreed to remove west of the Mississippi River; the major Miami removal to Kansas occurred in October 1846.

Not all of Indiana's Native Americans left the state. Less than one half of the Miami removed. More than a half of the Miami either returned to Indiana or were never required to leave under the terms of the treaties. The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians

Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians (Potawatomi: Pokégnek Bodéwadmik) are a federally recognized Potawatomi-speaking tribe based in southwestern Michigan and northeastern Indiana. Tribal government functions are located in Dowagiac, Michigan. ...

were the only other Indians left in the state after the end of the removals. Native Americans remaining in Indiana settled on privately owned land and eventually merged into the majority culture, although some retained ties to their Native American heritage. Members of the Miami Nation of Indiana concentrated along the Wabash River, while other Native Americans settled in Indiana's urban centers. In 2000 the state's population included more than 39,000 Native Americans from more than 150 tribes.

Indian settlement

TheMiami people

The Miami ( Miami-Illinois: ''Myaamiaki'') are a Native American nation originally speaking one of the Algonquian languages. Among the peoples known as the Great Lakes tribes, they occupied territory that is now identified as North-central Indi ...

and the Potawatomi

The Potawatomi , also spelled Pottawatomi and Pottawatomie (among many variations), are a Native American people of the western Great Lakes region, upper Mississippi River and Great Plains. They traditionally speak the Potawatomi language, a m ...

were the most important native tribes to establish themselves in the region now known as Indiana. In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, some of these Algonquians

The Algonquian are one of the most populous and widespread North American native language groups. Historically, the peoples were prominent along the Atlantic Coast and into the interior along the Saint Lawrence River and around the Great Lakes. T ...

returned from the north, where they had sought refuge from the Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian Peoples, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Indigenous confederations in North America, confederacy of First Nations in Canada, First Natio ...

during the Beaver Wars

The Beaver Wars ( moh, Tsianì kayonkwere), also known as the Iroquois Wars or the French and Iroquois Wars (french: Guerres franco-iroquoises) were a series of conflicts fought intermittently during the 17th century in North America throughout t ...

.Glenn and Rafert, p. 20. The Miami remained Indiana's largest tribal group, and had a significant presence along the Maumee, Wabash, and Miami rivers in what is now central and west central Indiana. They also held land in a large part of northwest Ohio

Ohio () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Of the List of states and territories of the United States, fifty U.S. states, it is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 34th-l ...

. The Potawatomi settled north of the Wabash River, along Lake Michigan

Lake Michigan is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is the second-largest of the Great Lakes by volume () and the third-largest by surface area (), after Lake Superior and Lake Huron. To the east, its basin is conjoined with that o ...

in northern Indiana, and in present-day Michigan

Michigan () is a state in the Great Lakes region of the upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the 10th-largest state by population, the 11th-largest by area, and t ...

. The Wea settled on the middle Wabash, near present-day Lafayette; the Piankeshaw

The Piankeshaw, Piankashaw or Pianguichia were members of the Miami tribe who lived apart from the rest of the Miami nation, therefore they were known as Peeyankihšiaki ("splitting off" from the others, Sing.: ''Peeyankihšia'' - "Piankeshaw Per ...

established themselves near the French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

settlement at Vincennes

Vincennes (, ) is a commune in the Val-de-Marne department in the eastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the centre of Paris. It is next to but does not include the Château de Vincennes and Bois de Vincennes, which are attache ...

; and the Eel River band settled along the river in northwestern and north central Indiana. The Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

came to west central Indiana after American colonists forced them out of Ohio

Ohio () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Of the List of states and territories of the United States, fifty U.S. states, it is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 34th-l ...

. Smaller groups, including the Lenape

The Lenape (, , or Lenape , del, Lënapeyok) also called the Leni Lenape, Lenni Lenape and Delaware people, are an indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, who live in the United States and Canada. Their historical territory inclu ...

(Delaware), Wyandott, Kickapoo, and others were scattered across other areas. These native tribes lived in agricultural villages along the rivers and exchanged furs for European goods with French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

traders, who began to arrive in region in the late 1600s.

Treaties

Early treaties

FollowingBritain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

's victory over the French in the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the st ...

(as part of the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754 ...

), the 1763 Treaty of Paris

The Treaty of Paris, also known as the Treaty of 1763, was signed on 10 February 1763 by the kingdoms of Great Britain, France and Spain, with Portugal in agreement, after Great Britain and Prussia's victory over France and Spain during the ...

which ended the war gave the British nominal control over North American territories east of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

. Upon hearing news of the victory, thousands of American settlers moved westward to settle east of the Mississippi. After the Indian tribes in the region, dissatisfied with British policies, launched Pontiac's War

Pontiac's War (also known as Pontiac's Conspiracy or Pontiac's Rebellion) was launched in 1763 by a loose confederation of Native Americans dissatisfied with British rule in the Great Lakes region following the French and Indian War (1754–17 ...

, the Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has differ ...

issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The Procla ...

, which forbade American colonists from settling west of the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. The ...

- an act which proved ineffective. Westward movement of American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

settler

A settler is a person who has migrated to an area and established a permanent residence there, often to colonize the area.

A settler who migrates to an area previously uninhabited or sparsely inhabited may be described as a pioneer.

Settle ...

s onto Indian lands continued.

After the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

and the newly independent United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

signed the 1783 Treaty of Paris, in which Britain ceded to the Americans a large portion of their land claims in North America, including present-day Indiana, but the native tribes who occupied the land argued that they had not been represented in the treaty negotiations and ignored its terms. Further negotiations were held to establish compensation for the loss of tribal lands, while American military expeditions were called to control Indian resistance. An Indian confederacy waged war against the Americans, but the confederacy was defeated at the Battle of Fallen Timbers (1794), at the conclusion of the Northwest Indian War

The Northwest Indian War (1786–1795), also known by other names, was an armed conflict for control of the Northwest Territory fought between the United States and a united group of Native American nations known today as the Northwestern ...

. With the loss of British military support and supplies after their withdrawal from the Northwest Territory, the defeat was a turning point that lead to land cessions and the eventual removal of most Native Americans from present-day Indiana.

The 1795 Treaty of Greenville was the first to cede Native American land in what became the state of Indiana and made it easier for American settlers to reach territorial lands north of the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of ...

. Under its terms, the American government acquired two-thirds of present-day Ohio

Ohio () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Of the List of states and territories of the United States, fifty U.S. states, it is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 34th-l ...

, a small tract of land in what would become southeastern Indiana, the Wabash-Maumee portage (near the present-day site of Fort Wayne, Indiana

Fort Wayne is a city in and the county seat of Allen County, Indiana, United States. Located in northeastern Indiana, the city is west of the Ohio border and south of the Michigan border. The city's population was 263,886 as of the 2020 Censu ...

), and early settlements at Vincennes

Vincennes (, ) is a commune in the Val-de-Marne department in the eastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the centre of Paris. It is next to but does not include the Château de Vincennes and Bois de Vincennes, which are attache ...

, Ouiatenon

Ouiatenon ( mia, waayaahtanonki) was a dwelling place of members of the Wea tribe of Native Americans. The name ''Ouiatenon'', also variously given as ''Ouiatanon'', ''Oujatanon'', ''Ouiatano'' or other similar forms, is a French rendering of ...

(in present-day Tippecanoe County, Indiana, and Clark's Grant, (near present-day Clarksville, Indiana

Clarksville is a town in Clark County, Indiana, United States, along the Ohio River and is a part of the Louisville Metropolitan area. The population was 22,333 at the 2020 census. The town was founded in 1783 by early resident George Rogers Cla ...

, along the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of ...

. In exchange, the Indians received goods valued at $20,000 and annuity payments. Most of the remaining territory, including a large portion of present-day Indiana, remained occupied by native tribes, but the tribes living along the Wabash-Maumee portage had to relocate. The Shawnee removed east to Ohio; the Delaware established villages along the White River; and the Miami at Kekionga moved to the Upper Wabash and its tributaries.

Territorial treaties

Indian removal followed a sequence of the land cession treaties that began during Indiana's territorial era. TheNorthwest Ordinance

The Northwest Ordinance (formally An Ordinance for the Government of the Territory of the United States, North-West of the River Ohio and also known as the Ordinance of 1787), enacted July 13, 1787, was an organic act of the Congress of the Co ...

(1787), which created the Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

, provided for the future division of western land into smaller territories, including the Indiana Territory

The Indiana Territory, officially the Territory of Indiana, was created by a congressional act that President John Adams signed into law on May 7, 1800, to form an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, ...

, established in 1800. One of the immediate needs for the federal government and William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

, who was appointed governor of the Indiana Territory in 1800 and served until 1812, was to encourage rapid settlement by reducing threats of violence from the area's native tribes and to establish a policy for acquiring ownership of territorial lands. Harrison initially had no power to negotiate treaties with the tribes; however, after his reappointment in 1803, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

granted Harrison the authority to conduct negotiations with the tribes and to open up new land for settlement, primarily the American claim to the Vincennes tract. The Vincennes tract had been purchased by the French colonial authorities from the natives in the mid-18th century and transferred to Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

after the French and Indian War, and finally to the Americans at the end of the Revolutionary War.

Harrison intended to expand settlement beyond the small population centers of Vincennes and Clarks Grant through a series of land cession treaties. Efforts were also made to establish the Indians as farmers. The other alternative was their removal to unsettled lands farther west. Harrison's tactics to obtain land cessions from the Indians included aggressive negotiations with the weaker tribes first, and then divide and conquer the remaining groups. The American military was available to resolve any conflicts. Harrison offered annuity payments of money and goods in exchange for land as part of his negotiations. He also rewarded cooperative tribal leaders with trips to Washington, D.C., and offered bribes. Negotiations often relied on intermediaries, especially those who could act as interpreters, such as Jean Baptiste Richardville

Jean Baptiste de Richardville ( 1761 – 13 August 1841), also known as or in the Miami-Illinois language (meaning 'Wildcat' or 'Lynx') or John Richardville in English, was the last 'civil chief' of the Miami people. He began his career in the ...

, William Wells, William Conner

William Conner (December 10, 1777 – August 28, 1855) was an American trader, interpreter, military scout, community leader, entrepreneur, and politician. Although Conner initially established himself as a fur trader on the Michigan and ...

, and others.

Between 1803 and 1809, Harrison negotiated land cession treaties with the Delaware, Shawnee, Potawatomi, and Miami tribes, among others, to secure nearly all the Indian land in most of present-day Illinois and the southern third of Indiana for new settlement. In total, Harrison negotiated thirteen land treaties across the Northwest Territory, which included eleven land cession treaties from 1803 through 1809 that encompassed more than 2.5 million acres (10,000 km2) of land in the Indiana Territory. Several factors worked in Harrison's favor: a declining fur trade, the Indians' increased dependency on annuity payments and manufactured goods, and internal conflicts among the tribes, many of whom did not agree with the American concept of land ownership and transfer of land titles.

Harrison's first treaty, the 1803 Treaty of Vincennes, was successful in getting the Wea and the Miami to recognize American ownership of the Vincennes tract between Kaskaskia

The Kaskaskia were one of the indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands. They were one of about a dozen cognate tribes that made up the Illiniwek Confederation, also called the Illinois Confederation. Their longstanding homeland was in ...

and Clark's Grant.

The

The Treaty of Grouseland

The Treaty of Grouseland was an agreement negotiated by Governor William Henry Harrison of the Indiana Territory on behalf of the government of the United States of America with Native American leaders, including Little Turtle and Buckongahelas, ...

(1805) was the second significant treaty to expand the Indiana Territory for additional settlement. Harrison negotiated with the Delaware, Potawatomi, Miami, Wea, and the Eel River band at Grouseland

Grouseland, the William Henry Harrison Mansion and Museum, is a National Historic Landmark important for its Federal-style architecture and role in American history. The two-story, red brick home was built between 1802 and 1804 in Vincennes, I ...

, Harrison's home at Vincennes. Under its terms the tribes ceded their land in southern Indiana south of the Grouseland Line, which began at the northeast corner of the Vincennes tract and passed northeast to the Greenville Treaty Line. Settlers, like Squire Boone

In the Middle Ages, a squire was the shield- or armour-bearer of a knight.

Use of the term evolved over time. Initially, a squire served as a knight's apprentice. Later, a village leader or a lord of the manor might come to be known as a " ...

, moved into the new land and established new towns, including Corydon—the future capitol—in 1808, and Madison Madison may refer to:

People

* Madison (name), a given name and a surname

* James Madison (1751–1836), fourth president of the United States

Place names

* Madison, Wisconsin, the state capital of Wisconsin and the largest city known by this ...

in 1809.

Under the terms of the Treaty of Fort Wayne (1809)

The Treaty of Fort Wayne, sometimes called the Ten O'clock Line Treaty or the Twelve Mile Line Treaty, is an 1809 treaty that obtained 29,719,530 acres of Native American land for the settlers of Illinois and Indiana. The negotiations primaril ...

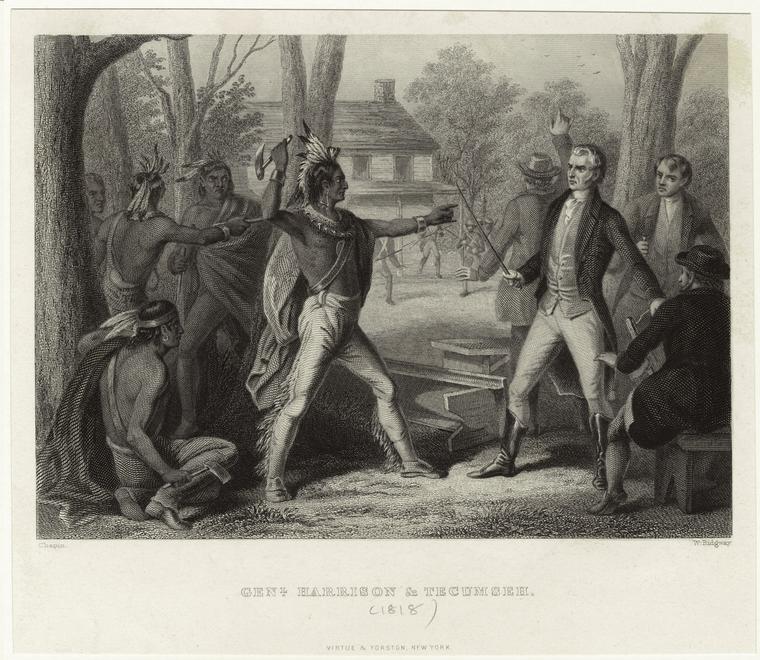

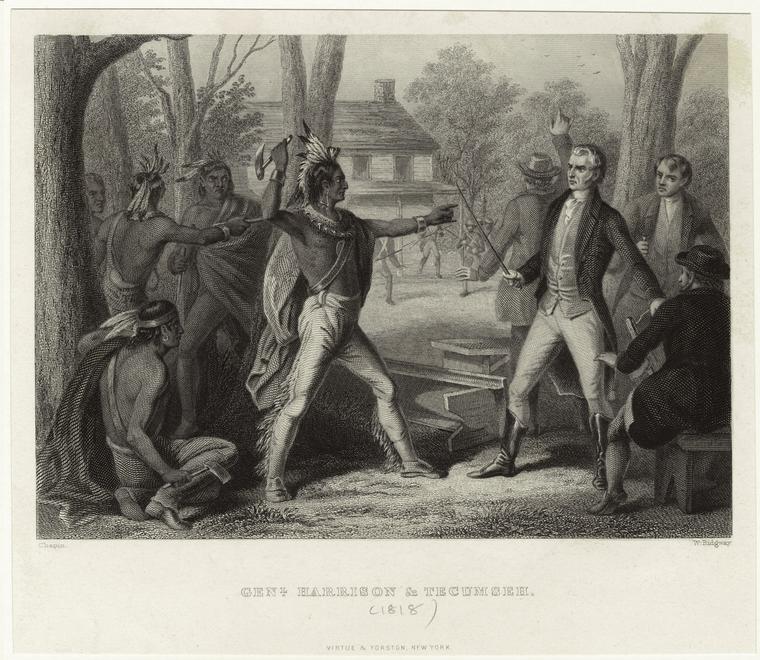

Harrison purchased an estimated 2.5 million acres (10,000 km2) of land, now a part of present-day Illinois and Indiana, from the Miami. The Shawnee, who were not included in the negotiations, inhabited the western tract of land that the Miami ceded to the federal government sold were angered by its terms, but Harrison refused to rescind the treaty. In August 1810 Harrison and the Shawnee leader Tecumseh

Tecumseh ( ; October 5, 1813) was a Shawnee chief and warrior who promoted resistance to the expansion of the United States onto Native American lands. A persuasive orator, Tecumseh traveled widely, forming a Native American confederacy and ...

met at Grouseland to discuss the continued conflict. Tecumseh bitterly complained about the land ceded to the federal government. Speaking through an interpreter, Tecumseh argued: "The Great Sp rit has given them as common property to all the Indians, and that they could not, nor should not be sold without the sent of all." The gathering ended without a resolution, as did a subsequent meeting in 1811. This disagreement escalated into an armed conflict, called

Tecumseh's War

Tecumseh's War or Tecumseh's Rebellion was a conflict between the United States and Tecumseh's Confederacy, led by the Shawnee leader Tecumseh in the Indiana Territory. Although the war is often considered to have climaxed with William Henry Ha ...

. The final blow that destroyed the Indian confederacy took place at the Battle of the Thames

The Battle of the Thames , also known as the Battle of Moraviantown, was an American victory in the War of 1812 against Tecumseh's Confederacy and their British allies. It took place on October 5, 1813, in Upper Canada, near Chatham. The Britis ...

in Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central Ca ...

, Canada, where Tecumseh was killed in 1813.

The War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

and subsequent treaties ended the Indians' militant resistance to dispossession of their lands. Although the Miami, Delaware, and Potawatomi remained in Indiana, most of the Wea band and the Kickapoo removed west to Illinois and Missouri. The U.S. government began to change its policy from coexistence with the Indians to increased acquisitions of their lands and provided the first hints of an official removal policy of tribes to the west, beyond the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

.

Treaties after statehood

In 1818

In 1818 Jonathan Jennings

Jonathan Jennings (March 27, 1784 – July 26, 1834) was the first governor of Indiana and a nine-term congressman from Indiana. Born in either Hunterdon County, New Jersey, or Rockbridge County, Virginia, he studied law before migrating to the ...

, the first governor of Indiana

The governor of Indiana is the head of government of the State of Indiana. The governor is elected to a four-year term and is responsible for overseeing the day-to-day management of the functions of many agencies of the Indiana state governmen ...

, Lewis Cass

Lewis Cass (October 9, 1782June 17, 1866) was an American military officer, politician, and statesman. He represented Michigan in the United States Senate and served in the Cabinets of two U.S. Presidents, Andrew Jackson and James Buchanan. He w ...

, and Benjamin Parke

Benjamin Parke (September 2, 1777 – July 12, 1835) was an American lawyer, politician, militia officer, businessman, treaty negotiator in the Indiana Territory who also served as a United States federal judge in Indiana after it attained stateho ...

negotiated a series of agreements collectively known as the Treaty of St. Mary's with the Miami, Wea, Delaware, Potawatomi, and other tribes that relinquished land in central Indiana and Ohio to the federal government. The treaty with the Miami acquired most of their land south of the Wabash River

The Wabash River (French: Ouabache) is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed May 13, 2011 river that drains most of the state of Indiana in the United States. It flows from ...

, except for the Big Miami Reserve in north central Indiana between the Eel River and the Salamonie River

The Salamonie River is a tributary of the Wabash River, in eastern Indiana in the United States. The river is long.U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed May 19, 2011 It is ...

. Portions of these lands were assigned to individual members of the Miami tribe. These allotments to individuals would protect many of the Miami, especially its leaders, from removal in 1846.

The Miami were in good standing with the state because they had opposed Tecumseh

Tecumseh ( ; October 5, 1813) was a Shawnee chief and warrior who promoted resistance to the expansion of the United States onto Native American lands. A persuasive orator, Tecumseh traveled widely, forming a Native American confederacy and ...

and tried to remain neutral during the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

. Under the terms of the treaty, the Miami also recognized the validity of a treaty with the Kickapoo, made in 1809, and led to the Kickapoo's subsequent removal from Indiana. The Wea, who inhabited the area around present-day Lafayette, Indiana

Lafayette ( , ) is a city in and the county seat of Tippecanoe County, Indiana, United States, located northwest of Indianapolis and southeast of Chicago. West Lafayette, on the other side of the Wabash River, is home to Purdue University, whi ...

, agreed to a $3,000 annuity for their cessions of land in Indiana, Ohio, and Illinois.

Under the terms of the Treaty of St. Mary's, the

Under the terms of the Treaty of St. Mary's, the Lenape

The Lenape (, , or Lenape , del, Lënapeyok) also called the Leni Lenape, Lenni Lenape and Delaware people, are an indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, who live in the United States and Canada. Their historical territory inclu ...

(Delaware), who lived in central Indiana, around present-day Indianapolis, ceded their lands to the federal government, opening the area to further settlement, and agreed to leave Indiana and settle on lands provided for them west of the Mississippi River. In exchange for leaving the state, the Lenape were granted gifts and an annuity totaling $15,500. Most of the tribe left for the West during August and September 1820. The Potawatomi received annuities for ceding a portion of their Indiana land. Several tribal members were given individual grants of reservation land. Most of the Potawatomi did not remove from the state until 1838.Madison and Sandweiss, ''Hoosiers and the American Story'', p. 22.

After the years of peace that followed the War of 1812 and the land cessions under the Treaty of St. Mary's, Indiana's state government took a more conciliatory approach to Indiana relations, embarking on a plan to "civilize" their members rather than remove them. Using federal grants, several mission schools were opened to educate the tribes and promote Christianity; however, the missions were largely ineffective in meeting their goals.Esarey, p. 332.

Land cessions resumed in 1819. On August 30, Benjamin Parke concluded negotiations with the Kickapoo to cede their land in Indiana, which included most of present-day Vermillion County, in exchange for goods worth $3,000 and a ten-year annuity of $2,000 in silver. The treaty was not recognized by the Miami, who claimed the Kickapoos' land, but European-American pioneers continued to settle in the area.

Other agreements with the Wea, Potawatomi, Miami, Delaware, and Kickapoo were reached in 1819, when the tribes were invited to attend a meeting to establish a trade agreement. Trade with the Indians was among the most lucrative enterprises in the state. In exchange for treaty agreements the Wea were granted a $3,000 annuity; the Potawatomi were given a $2,500 annuity; the Delaware received a $4,000 annuity' and the Miami were granted a $15,000 annuity. Smaller amounts were to other tribes. The annuities were accompanied by additional gifts to tribal leaders that were close to the same value of the annuity payments. Tribes also agreed to annual meetings at trading grounds near Fort Wayne

Fort Wayne is a city in and the county seat of Allen County, Indiana, United States. Located in northeastern Indiana, the city is west of the Ohio border and south of the Michigan border. The city's population was 263,886 as of the 2020 Cens ...

, where the annuities would be paid and tribes could sell their goods to traders. The annual event was the most important trading enterprise in the state from 1820 until 1840. Traders would gather and offer goods to the tribes, often at inflated prices and sell them on credit. After the tribes approved the bills traders would take them to the Indian agent, who would pay the claims out of tribe's annuity funds. (Traders frequently served liquor to their customers and took advantage of their drunken state during trading.Esaray, p. 333.) Many of the leading politicians in the state, including Jonathan Jennings

Jonathan Jennings (March 27, 1784 – July 26, 1834) was the first governor of Indiana and a nine-term congressman from Indiana. Born in either Hunterdon County, New Jersey, or Rockbridge County, Virginia, he studied law before migrating to the ...

and John W. Davis, took active part in the trade and made significant profits in the enterprise.

In exchange for land cessions to the federal government, the Native Americans usually received annuities in cash and goods and an agreement to pay tribal debts. In some cases tribes were granted reservation lands for their use, salt, trinkets, and other gifts. Treaty provisions of land allotments to individuals and families and funds for fences, tools, and livestock were intended to help the Indians assimilate as farmers. Some treaties also provided assistance with land clearing, construction of mills, and provisions for blacksmiths, teachers, and schools.

The 1821 Treaty of Chicago concluded negotiations between the federal government and the Michigan Potawatomi to cede a narrow tract of Indiana land along the southern tip of Lake Michigan

Lake Michigan is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is the second-largest of the Great Lakes by volume () and the third-largest by surface area (), after Lake Superior and Lake Huron. To the east, its basin is conjoined with that o ...

and extended east of the St. Joseph River, near present-day South Bend

South Bend is a city in and the county seat of St. Joseph County, Indiana, on the St. Joseph River near its southernmost bend, from which it derives its name. As of the 2020 census, the city had a total of 103,453 residents and is the fourt ...

,

along with other lands in Illinois and the Michigan Territory

The Territory of Michigan was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from June 30, 1805, until January 26, 1837, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Michigan. Detroit ...

. In this treaty, the federal government also indicated its intention to construct an east–west road between Chicago, Detroit, and Fort Wayne.

The 1826 Treaty of Mississinewas with the Miami and Potawatomi included most of what remained of the Miami reservation lands in northeastern Indiana and northwestern Ohio, and confined the Miami to their reservations along the Wabash, Mississinewa, and Eel rivers. This included the land they had retained under the Treaty of St. Mary's. During treaty negotiations Lewis Cass described the federal government's rationale for Indian relocation: " u have a large tract of land here, which is of no service to you–You do not cultivate it, and this is but little game on it.... Your father owns a large country west of the Mississippi–He is anxious that his red children should remove there." The land cessions freed up the first public lands for settlement in northern Indiana, which developed into South Bend and Michigan City and included much of present-day LaPorte County, and portions of Porter County and Lake County, Indiana

Lake County is a county (United States), county located in the U.S. state of Indiana. In 2020, its population was 498,700, making it Indiana's List of counties in Indiana, second-most populous county. The county seat is Crown Point, Indiana, Cro ...

. The treaty with the Potawatomi also arranged for the purchase of a narrow tract of land, where the federal government would construct the Michigan Road from Lake Michigan to Ohio River. In exchange for Indiana land north of the Wabash River, with the exception of some reserved lands that assured their continued presence in the area, the Miami agreed to receive livestock, goods, and annuity payments, while the Potawatomi received annuities in cash and goods, and funds from the federal government to erect a mill and employ a miller and blacksmith, among other provisions. The federal government also agreed to pay tribal debts. Treaties with the Potawatomi were renegotiated in October 1832, when the tribe was granted larger annuities in cash and goods which totaled $365,729.87, and set aside land west of the Mississippi River (in present-day Kansas and Missouri) for the tribe's relocation.

Removals

Although the Delaware, Piankashaw, Kickapoo, Wea, and Shawnee tribes removed in the 1820s and 1830s, the Miami and the Potawatomi removals of the 1830s and 1840s were more gradual and incomplete. By 1840 the Miami remained the only "intact tribe wholly within Indiana." Although the Miami agreed to remove in 1840, their tribal leaders delayed the process for several years. Most but not all of the remaining Miami left in 1846. Removal of Indiana's Native Americans did not begin immediately after the U.S. Congress passed theIndian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for ...

in 1830; however, the Black Hawk War

The Black Hawk War was a conflict between the United States and Native Americans led by Black Hawk, a Sauk leader. The war erupted after Black Hawk and a group of Sauks, Meskwakis (Fox), and Kickapoos, known as the "British Band", cross ...

in neighboring Illinois in 1832 renewed the fear of violence between Indiana's settlers and the local tribes. Other factors lead to the increased pressure for removal. New roads and canals passed through Indian lands within Indiana, providing easier access to settlement in northern Indiana. White settlers also argued that the native tribes had rejected earlier efforts to adapt to "civilized society," and suggested that removal west would allow them to progress on their own timetable, away from some of the more negative changes in their lives, most notably the consumption of liquor.

Organized efforts began to remove the native tribes from the state in 1832. In July the Indian Services Bureau of the state was reorganized. Funds were appropriated to hold negotiations with tribal leaders and offer inducements for them to leave Indiana for lands in the West. The rising tensions following the Black Hawk War had also caused alarm among the tribes. By the 1830s white settlers far outnumbered the native tribes still living in Indiana. Some, but not all of the tribal leaders thought resistance would be futile and encouraged their people to accept the best deal for their lands while they were still in a position to negotiate. Other tribes did not want to leave their lands in Indiana and refused to cooperate.Madison and Sandweiss, ''Hoosiers and the American Story'', p. 21.

Not everyone in Indiana wanted the Native Americans to leave, but most of their reasons served economic interests. Towns near the reservation lands depended on increased tribes' annual annuities as an ongoing source of revenue, especially the Indian traders. A few of the traders were also land speculators, who purchased the ceded Indian lands from the federal government and sold them to pioneer settlers, amassing considerable profits for their efforts. In addition, land cession treaties often included provisions for payment of claims on Indian debts to the traders.

In theory removals were supposed to be voluntary, but negotiators put considerable pressure on tribal leaders to accept relocation agreements. The Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

, under President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

's administration, provided federal authority under the Indian Removal Act to negotiate with native tribes living in eastern states and offer territorial land west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

in exchange lands in the established states. In a series of treaties from 1832 to 1840, tribal leaders surrendered multiple tracts of land in Indiana to the federal government.Madison, ''Hoosiers'', p. 121. According to Indian agent John Tipton, between five and six thousand Indian "tribesmen" were living in Indiana in 1831; approximately 1,200 of them were Miami and the remainder were Potawatomi. The Potawatomi held title to an estimated three million acres in north central and northwestern Indiana, while the Miami held the Big Miami Reserve, on thirty-four square miles near the Wabash River, and other smaller tracts that totaled more than nine thousand acres.

The Vermillion Kickapoo and some of the Potawatomi, who were under the leadership of Kennekuk, the Kickapoo Prophet, removed in 1832; the forced removal of the Potawatomi in what became known as the Potawatomi Trail of Death occurred in 1838; and the Miami ceded all but a small portion of their remaining land in Indiana in treaty negotiations made in 1838 and 1840. A small reservation of Miami land along the Mississinewa River, in southern Wabash County and northern Grant

Grant or Grants may refer to:

Places

*Grant County (disambiguation)

Australia

* Grant, Queensland, a locality in the Barcaldine Region, Queensland, Australia

United Kingdom

* Castle Grant

United States

* Grant, Alabama

* Grant, Inyo County, ...

counties, and scattered allotments to individuals were their only lands that the Miami retained for their use after 1840.

Potawatomi

In the 1830s Indian agents began going through the Potawatomi communities in northern Indiana, offering annuities, goods, payment of tribal debts, and reservation land in the West, among other provisions, in exchange for their land in Indiana. Most of the Potawatomi accepted the terms, including the federal government's agreement to pay for the removal to their new homes. The same type of negotiations with tribes in other states achieved similar results. TheTreaty of Tippecanoe

The Treaty of Tippecanoe was an agreement between the United States government and Native American Potawatomi tribes in Indiana on October 26, 1832.

Treaty

On October 26, 1832, the United States government entered negotiations with the Native ...

(1832), a series of three treaties negotiated with the Potawatomi in October 1832, ceded Indian land in Indiana, Illinois, and part of Michigan to the federal government, except for small reservation lands for tribal use and scattered allotments to individuals. Under these treaties the federal government acquired more than four million acres of Potawatomi land in northeastern Indiana in exchange for annuities worth $880,000, goods worth $247,000, and payment of tribal debts amounting to $111,879. The total aggregate value of these three treaties was more than $1.2 million (about thirty cents per acre). Fourteen treaties made in 1834, 1836, and in 1837 ceded additional tracts of Indiana land in exchange for payments in cash and goods that amounted to $105,440.Carmony, p. 555. The federal government also agreed to set aside reservation land west of the Mississippi River, in present-day Kansas and Missouri, and reduced the Potawatomi holdings in Indiana to a tract of reservation land along the Yellow River

The Yellow River or Huang He (Chinese: , Mandarin: ''Huáng hé'' ) is the second-longest river in China, after the Yangtze River, and the sixth-longest river system in the world at the estimated length of . Originating in the Bayan Ha ...

. In 1836 alone, the federal government negotiated nine additional treaties with the Potawatomi to cede the remaining Potawatomi land in Indiana. These treaties required the Potawatomi to leave Indiana within two years.

The Treaty of Yellow River (1836), one of Indiana's more contentious treaties, offered the Potawatomi $14,080 for two sections of Indiana land, but Chief Menominee and seventeen others refused to accept the terms of the sale.Campion, p. 51. The Yellow River band of Potawatomi living near Twin Lakes, Indiana, led by Chief Menominee, refused to take part in the negotiations and did not recognize the treaty's authority over their band. Under the terms of treaties made in 1836, the Potawatomi were required to vacate their land in Indiana within two years, including the Yellow River band. Menominee refused: "I have not signed any treaty, and will not sign any. I am not going to leave my land, and I do not want to hear anything more about it." Father Deseille, the Catholic missionary at Twin Lakes, also denounced the Yellow River Treaty (1836) as a fraud. Col. Pepper, the federal government's treaty negotiator, believed that Father Deseille was interfering with their plans for removal of the Potawatomi from Indiana, and ordered the priest to leave the mission at Twin Lakes or risk prosecution.McKee, "The Centennial of 'The Trail of Death'," p. 34–35. The federal government refused Menominee's demands, and the chief and his band were forced to leave the state in 1838.

Indiana governor David Wallace authorized General John Tipton

John Tipton (August 14, 1786 – April 5, 1839) was from Tennessee and became a farmer in Indiana; an officer in the 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe, and veteran officer of the War of 1812, in which he reached the rank of Brigadier General; and po ...

to forcefully remove the Potawatomi in what became known as the Potawatomi Trail of Death

The Potawatomi Trail of Death was the forced removal by militia in 1838 of about 859 members of the Potawatomi nation from Indiana to reservation lands in what is now eastern Kansas.

The march began at Twin Lakes, Indiana (Myers Lake and Cook ...

, the single largest Indian removal in the state. Beginning on September 4, 1838, a group of 859 Potawatomi were force marched from Twin Lakes to Osawatomie, Kansas. The difficult journey of about , in hot, dry weather and without sufficient food or water, lead to the death of 42 people, 28 of them children.

Subsequent treaties with other Potawatomi tribes ceded additional lands in Indiana and removals continued. In a treaty made on September 23, 1836, the federal government agreed to purchase forty-two sections of their Indiana land for $33,600 (or $1.25 per acre, the minimum purchase price the government could receive from the sale of public lands). A treaty made with the Potawatomi on February 11, 1837, provided for further cessions of Indiana land in exchange for a parcel of reservation land for tribal members on the Osage River, southwest of the Missouri River in present-day Kansas, and other guarantees. Another small group of Potawatomi from Indiana removed in 1850. Those who had been forcefully removed were initially relocated to reservation land in eastern Kansas, but moved to another reservation in the Kansas River

The Kansas River, also known as the Kaw, is a river in northeastern Kansas in the United States. It is the southwesternmost part of the Missouri River drainage, which is in turn the northwesternmost portion of the extensive Mississippi River dr ...

valley after 1846. Not all the Potawatomi from Indiana removed to Kansas. A small group joined an estimated 2,500 Potawatomi in Canada.

Miami

Under the terms of treaties negotiated in 1834, 1838, and 1840, the Miami ceded further land in Indiana to the federal government, including portions of the Big Miami Reserve along the Wabash River. In the treaty agreement made in 1838, the Miami ceded a large portion of Miami reservation land in Indiana for annuities, cash payments to tribal leaders Jean Baptiste Richardville and Francis Godfroy, payment of tribal debts, and other considerations. Under the terms of theTreaty of the Wabash

The Treaty of the Wabash was an agreement between the United States government and Native American Miami tribes in Indiana on November 28, 1840.

On November 28, 1840, the United States government entered negotiations with the Miami tribe of nor ...

(1840), another large tract of the Miami Reservation was ceded to the federal government for $550,000, including annuities, payment of tribal debts, and other provisions. The Miami also agreed to remove to lands secured for them west of the Mississippi River.

Allotment of lands to individuals made under the treaties with the Miami permitted some members of the tribe to remain on the land as private landholders under the terms of the Treaty of St. Mary's. Individuals also received additional land allotments in subsequent treaties. Allotments given to tribal leaders and others were intended to reinforce the European concept of land use, but they could also be interpreted as bribes. In five treaties negotiated with the Miami between 1818 and 1840, Jean Baptist Richardville received 44 quarter sections of Indiana land in separate allotments and Francis Godfroy received 17 sections.

The remaining Miami reservation land was ceded to the federal government in 1846. The major removal of the Miami from Indiana began on October 6, 1846. The group left Peru, Indiana

Peru is a city in, and the county seat of, Miami County, Indiana, United States. It is north of Indianapolis. The population was 11,417 at the 2010 census, making it the most populous city in Miami County. Peru is located along the Wabash Rive ...

, and traveled by canal boat and steamboat to reach their reservation lands in Kansas on November 9, 1846. Six deaths occurred along the way and 323 tribal members made it to the Kansas reservation. A small group removed in 1847. In all, less than one half of the Miami removed from Indiana. More than a half of the tribe either returned to Indiana from the West or were never required to leave under the terms of the treaties.

After removal

Indian lands ceded to the federal government were sold to new owners–settlers and land speculators. More than three million acres of the ceded lands in Indiana were sold in 1836 alone. The financialpanic of 1837

The Panic of 1837 was a financial crisis in the United States that touched off a major depression, which lasted until the mid-1840s. Profits, prices, and wages went down, westward expansion was stalled, unemployment went up, and pessimism abound ...

slowed the land rush, but it did not stop it. Squatters also hoped to claim a portion of the former Indian land. Under the provisions of the Preemption Act (1838), the squatters who were heads of families and single men aged twenty-one or older were allowed to claim up of up to 160 acres; the right was later extended to widows.

Native Americans remaining in Indiana after the 1840s eventually merged into the majority culture, although some retained ties to their Native American heritage. Some groups chose to live together in small communities, which continue to exist. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century other Native American groups migrated to Indiana, a large portion of them were Cherokee. The Miami Nation of Indiana is concentrated along the Wabash River. Other Native Americans settled in Indiana's urban centers, such as Indianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

, Elkhart, Fort Wayne

Fort Wayne is a city in and the county seat of Allen County, Indiana, United States. Located in northeastern Indiana, the city is west of the Ohio border and south of the Michigan border. The city's population was 263,886 as of the 2020 Cens ...

, and Evansville

Evansville is a city in, and the county seat of, Vanderburgh County, Indiana, United States. The population was 118,414 at the 2020 census, making it the state's third-most populous city after Indianapolis and Fort Wayne, the largest city in ...

. The state's population in 2000 included more than 39,000 Native Americans from more than 150 tribes.Glenn and Rafert, p. 6, and

See also

*History of Indiana

The history of human activity in Indiana, a U.S. state in the Midwest, stems back to the migratory tribes of Native Americans who inhabited Indiana as early as 8000 BC. Tribes succeeded one another in dominance for several thousand years and rea ...

* List of treaties between the Potawatomi and the United States.

* Trail of Death

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Indian Removals In Indiana Potawatomi Native American history of Indiana Native American genocide Former Native American populated places in the United States Aboriginal title in the United States Ethnic cleansing in the United States Forced migrations of Native Americans in the United States 19th century in Indiana