Immanuel Church (Tel Aviv-Yafo) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Immanuel Church ( he, ææ æÀæææˆ æÂææ æææ, Knesiyat Immanu'el; german: Immanuelkirche; no, Immanuelkirken) is a

George Adams and Abraham McKenzie, colonists from

George Adams and Abraham McKenzie, colonists from

German Emperor William II, his wife Auguste Victoria, protectress of Jerusalem's Association, and their entourage stayed in Jaffa on 27 October 1898. Their travel agency Thomas Cook accommodated the imperial guests in Ustinov's "HûÇtel du Parc", the only establishment in Jaffa regarded suited for them, while the further entourage stayed in Hotel Jerusalem (then Seestraûe, today's Rechov Auerbach #6; æ´æææ ææææ´ææ) of the Templer Ernst Hardegg. Thus William II, as (Supreme governor of the Evangelical State Church in Prussia's older Provinces) kept the balance between Templers and Evangelical Protestants at his visit.

German Emperor William II, his wife Auguste Victoria, protectress of Jerusalem's Association, and their entourage stayed in Jaffa on 27 October 1898. Their travel agency Thomas Cook accommodated the imperial guests in Ustinov's "HûÇtel du Parc", the only establishment in Jaffa regarded suited for them, while the further entourage stayed in Hotel Jerusalem (then Seestraûe, today's Rechov Auerbach #6; æ´æææ ææææ´ææ) of the Templer Ernst Hardegg. Thus William II, as (Supreme governor of the Evangelical State Church in Prussia's older Provinces) kept the balance between Templers and Evangelical Protestants at his visit.

All German citizens hoped after the visit for an improvement of their treatment by the Ottoman authorities, but in vain, the tiny community of Germans in the Holy Land only played a marginal role in the German-Ottoman relationship, which was not to be obfuscated by quarrelling settlers in the Holy Land.

The hospital, founded by Metzler and run since 1869 by Templers and Protestant deaconesses, was financed by a health insurance, which provided for higher contributions by Protestants and lower ones for Templers, who considered themselves as the main providers of the hospital since its purchase in 1869. Generally the revenues of the health insurance also covered the cost caused by poor patients from the general Jaffa population, who were treated even though they could not pay for it. In 1901 the relations between Protestants and Templers had eased so far, that the Protestant contributions were lowered to 20 and 30 francs p.a., before both religious groups paid equal contributions as of 1906

Pastor Zeller, who officiated in Jaffa since 1906, took his efforts to reconcile both groups. After ten years of negotiating the unification of the Evangelical and the Templer school, long rejected by the Provost of Jerusalem and Jerusalem's Association, due to their prejudices against Templers as sectarians, an agreement was achieved. On 27 October 1913 the Evangelical and the Templer school merged into a common school in the new school building of the Templers, completed in October 1912, until its demolition located in today's Rechov Pines, opposite to #44 It remained an

All German citizens hoped after the visit for an improvement of their treatment by the Ottoman authorities, but in vain, the tiny community of Germans in the Holy Land only played a marginal role in the German-Ottoman relationship, which was not to be obfuscated by quarrelling settlers in the Holy Land.

The hospital, founded by Metzler and run since 1869 by Templers and Protestant deaconesses, was financed by a health insurance, which provided for higher contributions by Protestants and lower ones for Templers, who considered themselves as the main providers of the hospital since its purchase in 1869. Generally the revenues of the health insurance also covered the cost caused by poor patients from the general Jaffa population, who were treated even though they could not pay for it. In 1901 the relations between Protestants and Templers had eased so far, that the Protestant contributions were lowered to 20 and 30 francs p.a., before both religious groups paid equal contributions as of 1906

Pastor Zeller, who officiated in Jaffa since 1906, took his efforts to reconcile both groups. After ten years of negotiating the unification of the Evangelical and the Templer school, long rejected by the Provost of Jerusalem and Jerusalem's Association, due to their prejudices against Templers as sectarians, an agreement was achieved. On 27 October 1913 the Evangelical and the Templer school merged into a common school in the new school building of the Templers, completed in October 1912, until its demolition located in today's Rechov Pines, opposite to #44 It remained an

After Emperor William II's inauguration of the then Evangelical Church of the Redeemer in Jerusalem on Reformation Day, 31 October 1898, the bulk of the accompanying entourage was determined to return to Jaffa, to get back to their ship. However, a train accident on the

After Emperor William II's inauguration of the then Evangelical Church of the Redeemer in Jerusalem on Reformation Day, 31 October 1898, the bulk of the accompanying entourage was determined to return to Jaffa, to get back to their ship. However, a train accident on the

The interior of the approximately oriented prayer hall is covered by

The interior of the approximately oriented prayer hall is covered by

The furnishings were mostly imported from Germany. King

The furnishings were mostly imported from Germany. King

* 1858ã1870: Missionary (*1824ã1907*)

* 1866ã1886?: Pastor Johannes Gruhler (*1833ã1905*), only partially accepted due to his Anglican Rite

* 1870/1886ã1897: vacant

** 1885ã1895: Pastor Carl Schlicht (*1855ã1930*) in Jerusalem, per pro

* 1897ã1906: Pastor Albert Eugen Schlaich (*1870ã1954*)

* 1906ã1912: Pastor Wilhelm Georg Albert Zeller (*1879ã1929*)

* 1912ã1917: Pastor (*1884ã1959*)

* 1917ã1920 (in Egyptian exile): Pastor von Rabenau continued to serve the interned parishioners

* 1917ã1926 (for the parishioners remaining in Jaffa): vacant

** 1917ã1918: D. Dr. Friedrich Jeremias (*1868ã1945*), Provost of Jerusalem, per pro

** 1921: Prof. D. Dr.

* 1858ã1870: Missionary (*1824ã1907*)

* 1866ã1886?: Pastor Johannes Gruhler (*1833ã1905*), only partially accepted due to his Anglican Rite

* 1870/1886ã1897: vacant

** 1885ã1895: Pastor Carl Schlicht (*1855ã1930*) in Jerusalem, per pro

* 1897ã1906: Pastor Albert Eugen Schlaich (*1870ã1954*)

* 1906ã1912: Pastor Wilhelm Georg Albert Zeller (*1879ã1929*)

* 1912ã1917: Pastor (*1884ã1959*)

* 1917ã1920 (in Egyptian exile): Pastor von Rabenau continued to serve the interned parishioners

* 1917ã1926 (for the parishioners remaining in Jaffa): vacant

** 1917ã1918: D. Dr. Friedrich Jeremias (*1868ã1945*), Provost of Jerusalem, per pro

** 1921: Prof. D. Dr.

Website

Website

{{in lang, en Tel Aviv Immanuel Churches in Tel Aviv Tel Aviv Immanuel American diaspora in Israel Arab Israeli culture in Tel Aviv Austrian diaspora in Israel European-Israeli culture in Tel Aviv German diaspora in Israel Lutheran churches in Israel Messianic Judaism Norwegian diaspora in Asia Tel Aviv Immanuel Swiss diaspora in Israel

Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

church in the AmericanãGerman Colony

The AmericanãGerman Colony ( he, ææææˋææ ææææ´ææÏæææˆãææ´ææ ææˆ, ''HaMoshava HaAmerika'itãGermanit'') is a residential neighborhood in the southern part of Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel. It is located between Eilat Street and HaRabbi M ...

neighbourhood of Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( he, æˆøçø¥æøƒæø¡æøÇææ-æø¡æÊæø¿, translit=Tál-òƒává¨v-Yáfé ; ar, Ĉììì ÄÈìÄ´ììÄ´ ã ììÄÏììÄÏ, translit=Tall òƒAbá¨b-Yáfá, links=no), often referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the ...

in Israel

Israel (; he, æøÇæˋø¯ææ´ø¡æøçæ, ; ar, ÄËìÄ°ìÄÝìÄÏÄÎììì, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, æø¯æøÇææ øñæˆ æøÇæˋø¯ææ´ø¡æøçæ, label=none, translit=Medá¨nat Yá¨sráòƒál; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

.

The church was built in 1904 for the benefit of the German Evangelical community, which it served until its dissolution at the onset of World War II in 1940. In 1955, the Lutheran World Federation transferred control of the church building to the , and a new congregation started taking shape. Today the church is used by a variety of Protestant denominations, including the Messianic movement.

Historical background

George Adams and Abraham McKenzie, colonists from

George Adams and Abraham McKenzie, colonists from Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and ...

arrived in Jaffa on 22 September 1866. They founded the ''American Colony'' in Jaffa, now part of Tel Aviv-Yafo

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( he, æˆøçø¥æøƒæø¡æøÇææ-æø¡æÊæø¿, translit=Tál-òƒává¨v-Yáfé ; ar, Ĉììì ÄÈìÄ´ììÄ´ ã ììÄÏììÄÏ, translit=Tall òƒAbá¨b-Yáfá, links=no), often referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the ...

municipality. They erected their wooden houses from prefabricated segments they had brought with them. Many settlers contracted cholera, and about a third of them died. Most returned to America. In 1869, newly arriving settlers from the Kingdom of Wû¥rttemberg

The Kingdom of Wû¥rttemberg (german: KûÑnigreich Wû¥rttemberg ) was a German state that existed from 1805 to 1918, located within the area that is now Baden-Wû¥rttemberg. The kingdom was a continuation of the Duchy of Wû¥rttemberg, which existe ...

led by Georg David Hardegg (1812ã1879) and Christoph Hoffmann (1815-1885), members of the Temple Society, replaced them.

However, in June 1874 the Temple denomination underwent a schism. Temple leader Hardegg and about a third of the Templers seceded from the Temple Society, after personal and substantial quarrels with Christoph Hoffmann. In 1878 Hardegg and most of the schismatics founded the ''Temple Association'' (Tempelverein), but after Hardegg's death in the following year the cohesion of its adherents faded.

First congregation (1899-1948)

History

Establishment

In 1885 Pastor Carl Schlicht of the started toproselytise

Proselytism () is the policy of attempting to convert people's religious or political beliefs. Proselytism is illegal in some countries.

Some draw distinctions between ''evangelism'' or '' Daãwah'' and proselytism regarding proselytism as invol ...

among the schismatics and succeeded in forming Evangelical congregations. In 1889 former Templers, Protestant German and Swiss expatriates, and domestic and foreign proselytes established the Evangelical congregation of Jaffa. Johann Georg Kappus sen. (1826ã1905) became the first chairman of the congregation, seconded and later followed by his son Johann Georg Kappus jun. (1855ã1928).

Sponsorship and pastors until 1914

Among the parishioners were wealthy members such asPlato von Ustinov

Plato Freiherr von Ustinov (born Platon Grigoryevich Ustinov, russian: ÅţůîŃŧ ÅîšŰŃîîÅçÅýÅ¡î ÅÈîîšŧŃÅý; 1840ã1918) was a Russian-born German citizen and the owner of the HûÇtel du Parc (Park Hotel) in Jaffa, Ottoman Empire ...

and Wilhelm Friedrich Faber (1863ã1923), president of the Deutsche PalûÊstina-Bank

The Deutsche Orientbank (DOB, ) was a German bank, founded in 1905-1906 in Berlin and merged into Dresdner Bank in 1931-1932. It was originally intended for financing ventures in the Ottoman Empire and the Khedivate of Egypt.

In mid-1914 the ...

, who moved to Jaffa in 1899 when the bank opened its branch there.Eisler 1997, p. 128. Ustinov offered the new congregation the hall of his ''HûÇtel du Parc'' in Jaffa for services.Eisler 1997, p. 133.

Starting in 1890 granted Jaffa's Evangelical congregation financial subsidies. The pupils of apostate families had been excluded from the Templer school since 1874. The German government generally co-financed the schools of German language in the Holy Land with about a quarter of their annual budgets since 1880.

The Jerusalem's Association and the Lutheran Evangelical State Church in Wû¥rttemberg

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide interdenominational movement within Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being "born again", in which an individual experi ...

agreed to pay the salary of a professional pastor for the Jaffa congregation. They hired Albert Eugen Schlaich from Korntal, a theologian and educator. He arrived on 10 March 1897 and stayed at Ustinov's hotel until he and his wife found suitable accommodations. The congregation rented the local chapel of the London Society for Promoting Christianity Amongst the Jews for an annual payment of 100 franc

The franc is any of various units of currency. One franc is typically divided into 100 centimes. The name is said to derive from the Latin inscription ''francorum rex'' (King of the Franks) used on early French coins and until the 18th centu ...

s of the Latin Monetary Union

The Latin Monetary Union (LMU) was a 19th-century system that unified several European currencies into a single currency that could be used in all member states when most national currencies were still made out of gold and silver. It was establ ...

for its services. Schlaich introduced some Lutheran traditions from Wû¥rttemberg's state church. In 1900 ca. 30ã40 congregants attended services on Sundays in the chapel of the London Jews Missionary Society.

In 1905 Schlaich accused the German Vice Consul

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

Dr. Eugen Bû¥ge (1859ã1936) in Jaffa to be breaking consular secrets in return for gifts. So Bû¥ge was transferred for disciplinary reasons to Aleppo, however, the German Foreign Office urged also Schlaich's transfer, since it considered Schlaich and not Bû¥ge to have damaged its reputation abroad. The , the executive board of the Prussian state church, pressurised Jerusalem's Association to release Schlaich from his office in Jaffa, thus he was appointed for another pastorate in Germany. The Jaffa congregation gave Schlaich a farewell on 25 December 1905, and Georg Johannes Egger (1842) thanked Schlaich and his wife for 9 years of successful pastoral work.Eisler 1997, p. 139.

Between 1906 and 1912 the Jerusalem's Association and Evangelical State Church of Wû¥rttemberg financed Pastor Wilhelm Georg Albert Zeller.Foerster 1991, p. 118. He considered the growing Jewish immigration a threat to the Gentile

Gentile () is a word that usually means "someone who is not a Jew". Other groups that claim Israelite heritage, notably Mormons, sometimes use the term ''gentile'' to describe outsiders. More rarely, the term is generally used as a synonym fo ...

German colonists, reporting their fears, that they could be expelled in the end, and thus recommended their emigration to a German, less populated colony in Africa. He was followed by the charismatic pastor Dr. , again supported by Stuttgart-based sponsors.

On 6 April 1910 Prince Eitel Friedrich of Prussia

Prince Wilhelm Eitel Friedrich Christian Karl of Prussia (7 July 1883 ã 8 December 1942) was the second son of Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany by his first wife, Princess Augusta Viktoria of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg. He was born ...

and his wife Sophie Charlotte of Oldenburg visited Jaffa and Immanuel Church, where they were received by Pastor Zeller.

World War I (1914-1917)

After the outbreak ofWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

the Sublime Porte

The Sublime Porte, also known as the Ottoman Porte or High Porte ( ota, Ä´ÄÏÄ´ Ä¿ÄÏìÜ, Báb-áÝ álᨠor ''BabáÝali'', from ar, Ä´ÄÏÄ´, báb, gate and , , ), was a synecdoche for the central government of the Ottoman Empire.

History

The name ...

de facto abolished the personal exterritoriality

In international law, extraterritoriality is the state of being exempted from the jurisdiction of local law, usually as the result of diplomatic negotiations.

Historically, this primarily applied to individuals, as jurisdiction was usually cla ...

and consular jurisdiction for foreigners according to Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire

Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire were contracts between the Ottoman Empire and other powers in Europe, particularly France. Turkish capitulations, or AhidnûÂmes were generally bilateral acts whereby definite arrangements were entered int ...

on 7 September 1914.Foerster 1991, p. 124. Many young male parishioners left Jaffa to join the German Imperial Army

The Imperial German Army (1871ã1919), officially referred to as the German Army (german: Deutsches Heer), was the unified ground and air force of the German Empire. It was established in 1871 with the political unification of Germany under the ...

. Rabenau accompanied them to serve as military chaplain

A military chaplain ministers to military personnel and, in most cases, their families and civilians working for the military. In some cases they will also work with local civilians within a military area of operations.

Although the term ''cha ...

. The Prussian ''Evangelical Supreme Ecclesiastical Council'' ordered his return in October.Foerster 1991, p. 126. His wife and their two sons moved to Germany for the duration of the war.

The Ottoman authorities forced all enemy missionary institutions to close in October 1914 and many missionary pupils then joined the joint Evangelical-Templer school of Jaffa. Their premises were confiscated for military purposes. In November 1914 the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed V

Mehmed V ReéûÂd ( ota, ì

ÄÙì

Ä₤ ÄÛÄÏì

Ä°, MeáËmed-i á¨ûÂmis; tr, V. Mehmed or ; 2 November 1844 ã 3 July 1918) reigned as the 35th and penultimate Ottoman Sultan (). He was the son of Sultan Abdulmejid I. He succeeded his half-brother ...

declared in his function as Caliph

A caliphate or khiláfah ( ar, ÄÛìììÄÏììÄˋ, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, ÄÛììììììÄˋ , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

the Jihad, which aroused fear for anti-Christian atrocities among the parishioners.

The war years were characterised by an increasing inflation of the Ottoman banknotes, causing Jerusalem's Association severe transfer losses at remitting salaries to its collaborators in the Holy Land, since the association had to purchase ã in return for marks

Marks may refer to:

Business

* Mark's, a Canadian retail chain

* Marks & Spencer, a British retail chain

* Collective trade marks, trademarks owned by an organisation for the benefit of its members

* Marks & Co, the inspiration for the novel ...

ã foreign exchange

The foreign exchange market (Forex, FX, or currency market) is a global decentralized or over-the-counter (OTC) market for the trading of currencies. This market determines foreign exchange rates for every currency. It includes all as ...

denominated in inflationary Ottoman banknotes, which had to be sold again in Jaffa for less inflated Ottoman hard coins at a rate far below par. Until 1916 the Ottoman banknotes had dropped to a ô¥, later to of their pre-war rate in mark, which was inflated itself. The war-related scarcity of goods further caused a dearness of most products so Jerusalem's Association had to increase its transfers to the Holy Land.

British rule until 1931

On 17 November 1917 Britons captured Jaffa and most male parishioners of Austrian, German or Ottoman nationality from Jaffa and Sarona, including Rabenau, were interned in Wilhelma as enemy nationals . In 1918 the interned men were deported to a camp south of Gaza, while the parishioners remaining in Jaffa were subjected to strict police control.Foerster 1991, p. 137. In August 1918 the internees were relocated toSidi Bishr

Sidi Bishr ( ar, Ä°ìÄ₤ì Ä´ÄÇÄÝ) is a neighborhood in the Montaza District of Alexandria, Egypt. Established as a summering site by the Egyptian middle class before the Revolution of 1952, it has since become one of the largest neighborhoods of ...

and Helwan near Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ìÝììÄËìÄ°ìììììÄ₤ìÄÝììììÄˋì ; grc-gre, öö£öçöƒö˜ö§öÇüöçö¿öÝ, AlexûÀndria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, ì

ÄçÄÝ , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

. Rabenau and the internees built up congregational life in their Egyptian exile, lasting three years. With the Treaty of Versailes

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traitûˋ de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

becoming effective on 10 January 1920 the Egyptian camps were dissolved and Rabenau became the internees' coordinator of the closedown.Foerster 1991, p. 143. Most internees returned to the Holy Land, except of those banned by a British black list, such as D. Dr. Friedrich Jeremias, Provost of Jerusalem. Rabenau went to Germany to reunite with his family, the Britons refused his return to Jaffa in July 1920. In April 1921 the Prussian ''Evangelical Supreme Ecclesiastical Council'' appointed Gustaf Dalman

Gustaf Hermann Dalman (9 June 1855 ã 19 August 1941) was a German Lutheran theologian and orientalist. He did extensive field work in Palestine before the First World War, collecting inscriptions, poetry, and proverbs. He also collected physic ...

, formerly head of the German Protestant Institute of Archaeology in Jerusalem as Provost at the Evangelical Church of the Redeemer until Albrecht Alt

Albrecht Alt (20 September 1883, in Stû¥bach (Franconia) ã 24 April 1956, in Leipzig), was a leading Germany, German Protestantism, Protestant theology, theologian.

Eldest son of a Lutheran minister, he completed high school in Ansbach and stud ...

arrived.

In April 1926 Jerusalem's Association appointed Ernst Paetzold as auxiliary pastor for Jaffa.Foerster 1991, p. 152. In September 1928 he held a lecture at the annual conference of Levantine Protestant pastors titled "Our congregations in their position towards other groups of German culture". By 1930 the German Jew

Jews ( he, æø¯ææø¥æøÇææ, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

s made up the biggest group of Germans in the Holy Land, however a minority among all Palestinians, the Templers amounted to 1,300, and the remaining 400 Germans were ã except of few Catholics (mostly clergy) and few irreligionist

Irreligion or nonreligion is the absence or rejection of religion, or indifference to it. Irreligion takes many forms, ranging from the casual and unaware to full-fledged philosophies such as atheism and agnosticism, secular humanism and anti ...

s ã prevailingly Protestant, among them 160 parishioners (as of 1927) of the Jaffa congregation.Foerster 1991, p. 177.

In April 1931 Paetzold returned to Germany, and the pastorate remained unstaffed due to financial constraints in the Great Depression.Foerster 1991, p. 162.

Pre-WWII position vs. the Nazis

When theNazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

aimed at roughing up with the Protestant church bodies in Germany as of 1932, especially with the constitutional election of presbyter

Presbyter () is an honorific title for Christian clergy. The word derives from the Greek ''presbyteros,'' which means elder or senior, although many in the Christian antiquity would understand ''presbyteros'' to refer to the bishop functioning a ...

s and synodals of the old-Prussian church in November 1932, this did not play a role in the Holy Land. However, the newly founded Nazi Faith Movement of German Christians

German Christians (german: Deutsche Christen) were a pressure group and a movement within the German Evangelical Church that existed between 1932 and 1945, aligned towards the antisemitic, racist and ''Fû¥hrerprinzip'' ideological principles ...

gained an average of a third of the presbyters and synodals in Germany.

After Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

imposed on all German church bodies an unconstitutional reelection of all presbyters and synodals on 23 July 1933, the massive voter participation of Protestant Nazis, who had not shown up for years in services, let alone church elections, caused an extraordinarily high turnout, which yielded the ''German Christians'' a share of 70ã80% of the presbyters and synodals, with some exceptions. However, this did not automatically mean the total takeover of the German Christians in all Protestant organisations, since due to the decentral and grassroot organisation of many Protestant groups, the official church bodies had no direct control, this was especially true for missionary endowments such as Jerusalem's Association.

In Germany the Protestant opposition first formed among pastors with the Emergency Covenant of Pastors, founded to fight for pastors discriminated by the ''German Christians'' for their Jewish ancestry. This covenant helped to found the Protestant Confessing Church

The Confessing Church (german: link=no, Bekennende Kirche, ) was a movement within German Protestantism during Nazi Germany that arose in opposition to government-sponsored efforts to unify all Protestant churches into a single pro-Nazi German ...

es, which paralleled in all destroyed Protestant church bodies the official ''German Christian''-subjected church bodies, which the Confessing Church considered to be schismatic for their abandonment of the universal sacrament of baptism

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, öýö˜üüö¿üö¥öÝ, vûÀptisma) is a form of ritual purificationãa characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost ...

. Most pastors in the Holy Land sided with the Confessing Church as also did most members of the executive board of Jerusalem's Association, among them Rabenau, an opponent of Nazism since 1931. Jerusalem's Association appointed pastors, fired or furloughed by Nazi-submissive official church bodies, for congregations in the Holy Land.

On October 18ã20, 1933 the German Protestant missionary endowments within ''Deutscher Evangelischer Missionsbund'' (DEMB) convened in Barmen and rejected the attempt to subject the missionary societies ã in the course of the pervasive Gleichschaltung of all civic organisations ã to the Nazi-submissive German Evangelical Church

The German Evangelical Church (german: Deutsche Evangelische Kirche) was a successor to the German Evangelical Church Confederation from 1933 until 1945.

The German Christians, an antisemitic and racist pressure group and ''Kirchenpartei'', ga ...

. Jerusalem's Association retained its legal independence, successfully rejected the application of the so-called Aryan paragraph

An Aryan paragraph (german: Arierparagraph) was a clause in the statutes of an organization, corporation, or real estate deed that reserved membership and/or right of residence solely for members of the "Aryan race" and excluded from such rights a ...

for its own employees and the new appointment of its executive board with a majority of two thirds for ''German Christians''.

However, the Nazi-submissive ''German Christians'', holding crucial positions in the bureaucracy of the official Protestant church bodies, found other ways to pressurise the missionary societies. Foreign exchange assigned at non-market rates was exclusively to be disbursed for salaries of German nationals, thus salaries of Palestinian citizens (e.g. Arab Protestants) became very difficult to organise, Jerusalem's Association had to incur debts in Palestine pound

The Palestine pound ( ar, Ęìììììì ììììÄ°ìÄñìììììì, ; he, æÊæø¥æ ø¯æ æÊøñø¥æøÑæˋø¯ææˆøÇææ ø¡æøÇæ (ææÇæ), funt palestina'i (eretz-yisra'eli) or he, æææ´æ (ææÇæ), lira eretz-yisra'elit, link=no; Sign: ôÈP) was the ...

s with Deutsche PalûÊstina-Bank, which again had to be permitted by the Nazi government, which submitted any foreign indebtedness of German legal entities to its agreement as part of its austerity policy.

Since missions depended on transferring funds abroad the government rationing of foreign exchange became the means to blackmail their cooperation. Jerusalem's Association gained a certain support within the ''German Christian''-streamlined old-Prussian ''Evangelical Supreme Ecclesiastical Council'' and the Confessing Church, which both collected and transferred funds for the efforts of Jerusalem's Association. Since February 1934 the new Ecclesiastical Foreign Department (Kirchliches Auûenamt) under ''German Christian'' (1894ã1967) of the new Nazi-submissive ''German Evangelical Church'' claimed the supervision of German Protestant missions.Foerster 1991, p. 173. Heckel also presided the board of trustees of the Evangelical Jerusalem Foundation since 1933. Heckel decided on behalf of the Ecclesiastical Foreign Department to also subsidise salaries of ecclesiastical employees in Jaffa and Haifa earlier paid by Jerusalem's Association alone.

Unlike other missions Jerusalem's Association had only tiny revenues in foreign exchange out of Nazi control, namely the rent from the former Armenian Orphanage in Bethlehem, rented out to the British mandatory government for its insane asylum. Thus the foreign efforts of Jerusalem's Association mostly depended on transfers from Germany, now under Nazi government financial control. To get a ration of foreign exchange Jerusalem's Association needed the consent of the ''Evangelical Supreme Ecclesiastical Council'', to cause the government rationing office allotting foreign exchange.

The Levantine Protestant pastors decided on their annual conference at Easter

Easter,Traditional names for the feast in English are "Easter Day", as in the '' Book of Common Prayer''; "Easter Sunday", used by James Ussher''The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher, Volume 4'') and Samuel Pepys''The Diary of Samuel ...

1934 (1 April), to keep their congregations out of the German Nazi struggle of the churches . The pastors of Jaffa and Haifa anyway reported, that their congregations felt more related to Jerusalem's Association than to the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union

The Prussian Union of Churches (known under multiple other names) was a major Protestant church body which emerged in 1817 from a series of decrees by Frederick William III of Prussia that united both Lutheran and Reformed denominations in Pr ...

and its Provostry of Jerusalem.

In October 1934 the DEMB convened again in Tû¥bingen, declaring its partisanship with the Confessing Church and its Barmen declaration

__NOTOC__

The Barmen Declaration or the Theological Declaration of Barmen 1934 (German: ''Die Barmer Theologische ErklûÊrung'') was a document adopted by Christians in Nazi Germany who opposed the German Christian movement. In the view of the de ...

of May 1934, however, the actual policy depended ã case to case ã on the opinion of the respective responsible person. While in Germany ecclesiastical media were banned to report on the struggle of the churches, there was no censorship in British Palestine. So Provost Ernst Rhein, the responsible editor of the "Gemeindeblatt", let his then Vicar

A vicar (; Latin: '' vicarius'') is a representative, deputy or substitute; anyone acting "in the person of" or agent for a superior (compare "vicarious" in the sense of "at second hand"). Linguistically, ''vicar'' is cognate with the English pre ...

Georg Weiû (later deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Chur ...

in Nuremberg

Nuremberg ( ; german: link=no, Nû¥rnberg ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''NûÊmberch'' ) is the second-largest city of the German state of Bavaria after its capital Munich, and its 518,370 (2019) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest ...

) report on the German struggle of the churches, openly siding with the Confessing Church, in his article on the occasion of Harvest Festival

A harvest festival is an annual celebration that occurs around the time of the main harvest of a given region. Given the differences in climate and crops around the world, harvest festivals can be found at various times at different places. ...

(german: Erntedankfest). ''German Christian'' Heckel, head of the Ecclesiastical Foreign Department, heftily criticised Rhein and Weiû for that article.

In February 1935 Rabenau, meanwhile a leading representative of the Confessing Church and opponent of Nazism, resigned from doing the German public relations of Jerusalem's Association. After the ''Brethren Council'' of the old-Prussian Ecclesiastical Province of Pomerania

The Pomeranian Evangelical Church (german: link=no, Pommersche Evangelische Kirche; PEK) was a Protestant Landeskirche, regional church in the Germany, German state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, serving the citizens living in Hither Pomerania. The Po ...

, the Pomeranian Confessing Church executive, had agreed to release its Vicar Felix Moderow, he moved to Jaffa to serve there as auxiliary pastor from 1935 to 1937.LûÑffler 2001, p. 210. Also Provost Rhein demanded an opponent pastor as his new vicar and chose another Pomeranian theologist, Fritz Maass (1910ã2005), as his vicar in Jerusalem.Christoph Rhein, "Als Kind der deutschen Propstes in Jerusalem 1930ã1938", in: ''Dem ErlûÑser der Welt zur Ehre: Festschrift zum hundertjûÊhrigen JubilûÊum der Einweihung der evangelischen ErlûÑserkirche in Jerusalem'', Karl-Heinz Ronecker (ed.) on behalf of the 'Jerusalem-Stiftung' and 'Jerusalemsverein', Leipzig: Evangelische Verlags-Anstalt, 1998, pp. 222ã228, here p. 227. .

However, in the German diplomatic service the so-called Aryan paragraph

An Aryan paragraph (german: Arierparagraph) was a clause in the statutes of an organization, corporation, or real estate deed that reserved membership and/or right of residence solely for members of the "Aryan race" and excluded from such rights a ...

caused the furlough of Jerusalem's German Consul-General Dr. in summer 1935, since his Protestant wife Ilse (d. 1988), serving as presbyter of the Jerusalem Evangelical congregation, counted by the Nazi racist categories as partially Jewish. "Among the German inhabitants in the country, only the ews and theLutherans expressed sorrow at Wolff's dismissal and their Jerusalem newspaper emeindeblattpublished a warm article in praise of his activities. Similar sentiments were expressed in the Hebrew newspaper , which lauded his consular activity and heralded his efforts not to hurt the feelings of those opposed to the Nazi regime

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

."

In 1937 Pastor Christian Berg succeeded the retired Detwig von Oertzen in Haifa. Berg had been furloughed by his employer, the ''German Christian''-streamlined Evangelical Lutheran State Church of Mecklenburg The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Mecklenburg (german: Evangelisch-Lutherische Landeskirche Mecklenburgs; abbreviated ELLM) was a Lutheran church in the German state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, serving the citizens living in Mecklenburg. The seat of ...

, after the Nazi government sued him in a political trial in Schwerin

Schwerin (; Mecklenburgian Low German: ''Swerin''; Latin: ''Suerina'', ''Suerinum'') is the capital and second-largest city of the northeastern German state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern as well as of the region of Mecklenburg, after Rostock. It ...

in June 1934. For him Palestine became a safe exile from further Nazi stalking. After the Olympic close hunting season was over in Germany, the Nazi government increased again its persecution of opponents. The Gestapo arrested Rabenau and seven further leaders of the Confessing Church on 23 June 1937, when leaving Berlin's Friedrichswerder Church

Friedrichswerder Church (german: Friedrichswerdersche Kirche, french: Temple du Werder) was the first Neo-Gothic church built in Berlin, Germany. It was designed by an architect better known for his Neoclassical architecture, Karl Friedrich Schink ...

. After interrogations and some time in detention he was released again.

The "Neueste Nachrichten aus dem Morgenland", the journal of Jerusalem's Association, complained about Jewish immigration to Palestine (1937) and Arab Nationalism (1939), which it regarded as being due to the infiltration by European decomposing ideologies.

After Moderow's return to Germany in 1937 the retired Oertzen served again as pastor in Jaffa until 1939. Jerusalem's Association in Germany experienced a growing hostility by anti-Semites to its name, referring to Jerusalem, and its journal, referring to the Levant. Thus on 27 February 1938 Jerusalem's Association adopted the name affix Jerusalemsverein/Versorgung deutscher evangelischer Gemeinden und Arabermission in PalûÊstina (Jerusalem's Association/Maintenance of German Protestant congregations and missioning of Arabs in Palestine).

In July 1939 Oertzen left Jaffa for a summer holiday in Germany, but also to look after his salary, which had been withheld on a German account, for ã in preparation of the war ã the rationing office blocked most transfers abroad since early 1939. Jerusalem's Association used Haavara Ltd. for its transfers to Palestine between 1937 and 1939.Foerster 1991, p. 178.

World War II and after

WithGermany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

(September 1) and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

(September 17) invading Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

in 1939, the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countriesãincluding all of the great powersãforming two opposi ...

started, followed by the British internment of most male Jaffa parishioners of German or other enemy nationality as enemy alien

In customary international law, an enemy alien is any native, citizen, denizen or subject of any foreign nation or government with which a domestic nation or government is in conflict and who is liable to be apprehended, restrained, secured and ...

s. In May 1940 all remaining enemy aliens of Jaffa, Bir Salem, Sarona and Tel Aviv, not yet interned, such as Gentile

Gentile () is a word that usually means "someone who is not a Jew". Other groups that claim Israelite heritage, notably Mormons, sometimes use the term ''gentile'' to describe outsiders. More rarely, the term is generally used as a synonym fo ...

Germans, Hungarians, and Italians, were interned in Wilhelma, which was converted into an internment camp.Foerster 1991, p. 184. The remainder was evacuated to Cyprus in April 1948.

Relation to the Templers

The relations of the early Protestants of Jaffa were without major tensions. had sold other real estate and his hospital, which he had built up, to the Templers on 5 March 1869 under the proviso to further cooperate with Reformed (Calvinist)deaconess

The ministry of a deaconess is, in modern times, a usually non-ordained ministry for women in some Protestant, Oriental Orthodox, and Eastern Orthodox churches to provide pastoral care, especially for other women, and which may carry a limited l ...

es from Riehen and to provide charitable health care for all, who needed itEisler 1997, p. 140. The physician was Dr. Gottlob Sandel, father of the engineer . In 1882 the Wû¥rttembergian royal court preacher Dr. , however, defamed Templers in his "Protestantismus und Sekten" (Protestantism and sects) as bearing "the character of the morbidly abnormal." When in March 1897 Pastor Schlaich had arrived in Jaffa, the Templers offered him their fellowship hall for his first accession preach to the Evangelical congregation, and Schlaich acceptedEisler 1997, p. 115. However, in October the same year, travelling and fund-raising in Wû¥rttemberg, Schlaich unveiled that his aim is proselytising among Muslims and Templers, who felt deeply insulted to be mentioned in the same breath with non-Christian Muslims. So the relations chilled down again.

In 1897 and 1898 Templers of Jaffa and Sarona intrigued with the Sublime Porte

The Sublime Porte, also known as the Ottoman Porte or High Porte ( ota, Ä´ÄÏÄ´ Ä¿ÄÏìÜ, Báb-áÝ álᨠor ''BabáÝali'', from ar, Ä´ÄÏÄ´, báb, gate and , , ), was a synecdoche for the central government of the Ottoman Empire.

History

The name ...

and the German Foreign Office against the plans to build a combined Evangelical school and community centre, financed by generous donations of Braun and others. So the laying of the cornerstone for the Evangelical community centre was delayed, for Templers argued the title to the construction site would be under dispute So William II and Auguste Victoria could not attend it.

German Emperor William II, his wife Auguste Victoria, protectress of Jerusalem's Association, and their entourage stayed in Jaffa on 27 October 1898. Their travel agency Thomas Cook accommodated the imperial guests in Ustinov's "HûÇtel du Parc", the only establishment in Jaffa regarded suited for them, while the further entourage stayed in Hotel Jerusalem (then Seestraûe, today's Rechov Auerbach #6; æ´æææ ææææ´ææ) of the Templer Ernst Hardegg. Thus William II, as (Supreme governor of the Evangelical State Church in Prussia's older Provinces) kept the balance between Templers and Evangelical Protestants at his visit.

German Emperor William II, his wife Auguste Victoria, protectress of Jerusalem's Association, and their entourage stayed in Jaffa on 27 October 1898. Their travel agency Thomas Cook accommodated the imperial guests in Ustinov's "HûÇtel du Parc", the only establishment in Jaffa regarded suited for them, while the further entourage stayed in Hotel Jerusalem (then Seestraûe, today's Rechov Auerbach #6; æ´æææ ææææ´ææ) of the Templer Ernst Hardegg. Thus William II, as (Supreme governor of the Evangelical State Church in Prussia's older Provinces) kept the balance between Templers and Evangelical Protestants at his visit.

All German citizens hoped after the visit for an improvement of their treatment by the Ottoman authorities, but in vain, the tiny community of Germans in the Holy Land only played a marginal role in the German-Ottoman relationship, which was not to be obfuscated by quarrelling settlers in the Holy Land.

The hospital, founded by Metzler and run since 1869 by Templers and Protestant deaconesses, was financed by a health insurance, which provided for higher contributions by Protestants and lower ones for Templers, who considered themselves as the main providers of the hospital since its purchase in 1869. Generally the revenues of the health insurance also covered the cost caused by poor patients from the general Jaffa population, who were treated even though they could not pay for it. In 1901 the relations between Protestants and Templers had eased so far, that the Protestant contributions were lowered to 20 and 30 francs p.a., before both religious groups paid equal contributions as of 1906

Pastor Zeller, who officiated in Jaffa since 1906, took his efforts to reconcile both groups. After ten years of negotiating the unification of the Evangelical and the Templer school, long rejected by the Provost of Jerusalem and Jerusalem's Association, due to their prejudices against Templers as sectarians, an agreement was achieved. On 27 October 1913 the Evangelical and the Templer school merged into a common school in the new school building of the Templers, completed in October 1912, until its demolition located in today's Rechov Pines, opposite to #44 It remained an

All German citizens hoped after the visit for an improvement of their treatment by the Ottoman authorities, but in vain, the tiny community of Germans in the Holy Land only played a marginal role in the German-Ottoman relationship, which was not to be obfuscated by quarrelling settlers in the Holy Land.

The hospital, founded by Metzler and run since 1869 by Templers and Protestant deaconesses, was financed by a health insurance, which provided for higher contributions by Protestants and lower ones for Templers, who considered themselves as the main providers of the hospital since its purchase in 1869. Generally the revenues of the health insurance also covered the cost caused by poor patients from the general Jaffa population, who were treated even though they could not pay for it. In 1901 the relations between Protestants and Templers had eased so far, that the Protestant contributions were lowered to 20 and 30 francs p.a., before both religious groups paid equal contributions as of 1906

Pastor Zeller, who officiated in Jaffa since 1906, took his efforts to reconcile both groups. After ten years of negotiating the unification of the Evangelical and the Templer school, long rejected by the Provost of Jerusalem and Jerusalem's Association, due to their prejudices against Templers as sectarians, an agreement was achieved. On 27 October 1913 the Evangelical and the Templer school merged into a common school in the new school building of the Templers, completed in October 1912, until its demolition located in today's Rechov Pines, opposite to #44 It remained an oecumenical

Ecumenism (), also spelled oecumenism, is the concept and principle that Christians who belong to different Christian denominations should work together to develop closer relationships among their churches and promote Christian unity. The adjec ...

school until its closure by the Britons in November 1917. Jerusalem's Association spent 10% of its budget for schools in the Holy Land.

With the philosophy of the Temple Society, to reconstruct the Holy Land in order to gather the people of God, fading in view of the resurrection of the Holy Land by Jewish settlement, the Templers' faith lost binding power for many of its members and especially many younger discovered Nazism as a non-denominational replacement of the vacuum. Thus most Nazis in the Holy Land were from Templer background. This led to a complete turnaround in the Evangelical-Templers' relationship, because before 1933 the Evangelical Protestants had strong mental and financial support by German Protestant church bodies, while Templers were somewhat orphaned. After 1933 Templers increasingly usurped positions with influential connections to Nazi party and Nazi government bodies in Germany, while the German Protestant church bodies as partners of the Evangelical congregations in the Holy Land lost government support by the struggle of the churches and by Hitler's and Alfred Rosenberg

Alfred Ernst Rosenberg ( ã 16 October 1946) was a Baltic German Nazi theorist and ideologue. Rosenberg was first introduced to Adolf Hitler by Dietrich Eckart and he held several important posts in the Nazi government. He was the head o ...

's general abandonment of Christianity, considered indissolubly Judaised with the Ten Commandments and the Old Testament. Cornelius Schwarz, a Templer from Jaffa, led the Palestinian faction (Landesgruppe) of the Nazi party, with him many young men gained influence over long established institutions as the Evangelical provostry and its congregations as well as the Temple Society itself.LûÑffler 2001, p. 208. The German Foreign Office imposed on Gentile Germans of different denominational affiliations a stronger co-operation under influence of Palestinian Nazi officials of Temple background.

Status and number of parishioners, 1899ã1940

* 1889 ã the Evangelical congregation emergedFoerster 1991, p. 117. * 1890 ã it opened its school, its first permanent institution * 1894 and after ã the congregation comprised parishioners in Jaffa and Sarona (today's haQiriya). * 1906 ã the congregation of Jaffa included besides Sarona alsoIsdud

Isdud ( ar, ÄÏÄ°Ä₤ìÄ₤) is a former Palestinian village and the site of the ancient and classical-era Levantine metropolis of Ashdod. The Arab village, which had a population of 4,910 in 1945, was depopulated during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. T ...

and Ramla

Ramla or Ramle ( he, æ´øñæø¯æø¡æ, ''Ramlá''; ar, ÄÏìÄÝì

ìÄˋ, ''ar-Ramleh'') is a city in the Central District of Israel. Today, Ramle is one of Israel's mixed cities, with both a significant Jewish and Arab populations.

The city was f ...

, and became a fully fledged congregation within the ''Evangelical State Church of Prussia's older Provinces'', established according to its standards with full rights and bodies such as an elected presbytery (german: Gemeindekirchenrat, literally: congregation council).

* 1925 ã in December 1925 the Evangelical congregations of Jaffa, as well as that of Beirut (est. 1856), Haifa, Jerusalem and Waldheim joined the new umbrella organisation of the German Federation of Protestant Churches (1922ã1933), then led by President Hermann Kappler.

* 1940 ã with the internment of most of its parishioners in Wilhelma the congregation de facto ceased to exist in 1940.

The number of parishioners developed as follows:

*1869: 18 persons

*1889: 50 persons

*1898: 75 persons

*1900: 93 persons

*1901: 104 persons

In 1903 parishioners in Jaffa and Haifa amounted to 250 altogether.

*1904: 130 persons

*1913: 136 persons.

*1920: Jaffa congregation had lost parishioners through emigration after 1918.

*1927: 160 persons

*1934: 80ã90 persons

Congregational institutions

On 18 July 1898 Metzler, who then lived in Stuttgart, conveyed his last piece of real estate in Jaffa for the construction of an Evangelical church, community centre and pastor's apartment, to the congregation, while his friend and divorced son-in-law Ustinov rewarded Metzler with 10,000 francs two thirds of the site's estimated price In August 1898 Ernst August Voigt, architect of Haifa, handed in his plans for a combined church, community centre, school and pastor's apartment. The belated firman, permitting the building, finally arrived on 27 October 1898, after attempts of Templers to baffle the planned constructions, however, too late for an imperial attendance in the laying of the cornerstone. After Emperor William II's inauguration of the then Evangelical Church of the Redeemer in Jerusalem on Reformation Day, 31 October 1898, the bulk of the accompanying entourage was determined to return to Jaffa, to get back to their ship. However, a train accident on the

After Emperor William II's inauguration of the then Evangelical Church of the Redeemer in Jerusalem on Reformation Day, 31 October 1898, the bulk of the accompanying entourage was determined to return to Jaffa, to get back to their ship. However, a train accident on the JaffaãJerusalem railway

The JaffaãJerusalem railway (also J & J) is a railway that connected Jaffa and Jerusalem. The line was built in the Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem (Ottoman Syria) by the French company ''Sociûˋtûˋ du Chemin de Fer Ottoman de Jaffa û Jûˋrusalem et P ...

, opened in 1892, interrupted their journey, so that they only arrived in Jaffa on November 2.

Thus the Protestant dignitaries among them participated in the laying of the cornerstone for the Evangelical church and community centre in Jaffa, among them Dr. (*1832ã1901*), Prussian minister of education, cult, culture and medicine, the executive board of Jerusalem's Association, D. (*1831ã1903*), president of the ''Evangelical Supreme Ecclesiastical Council'' and General Superintendents of different ecclesiastical provinces within the Evangelical State Church of Prussia's older Provinces, representatives of other German and Swiss Protestant church bodies (Braun for Wû¥rttemberg), of the Lutheran Church of Norway and Church of Sweden

The Church of Sweden ( sv, Svenska kyrkan) is an Evangelical Lutheran national church in Sweden. A former state church, headquartered in Uppsala, with around 5.6 million members at year end 2021, it is the largest Christian denomination in Sw ...

as well as of other Protestant churches in Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, and the US, altogether 45 women and men of the imperial delegation. From the local notables Christoph Hoffmann II (jun.), president of the Temple Society, and representatives of the Evangelical congregations in Bethlehem in Judea, Bir Salem, Haifa, and Jerusalem participated in the ceremony. Braun, court preacher of King William II of Wû¥rttemberg

, spouse =

, issue = Pauline, Princess of WiedPrince Ulrich

, house = Wû¥rttemberg

, father = Prince Frederick of Wû¥rttemberg

, mother = Princess Catherine of Wû¥rttemberg

, birth_date =

, birth_place = St ...

, held the speech at the ceremony and donated himself 10,000 marksEisler 1997, p. 131. The actual cornerstone included the deed of foundation and seeds of grain and vegetables, symbolising the fertility of the Sharon plain

The Sharon plain ( ''HaSharon Arabic: Ä°ìì ÄÇÄÏÄÝìì Sahel Sharon'') is the central section of the Israeli coastal plain. The plain lies between the Mediterranean Sea to the west and the Samarian Hills, to the east. It stretches from Nahal T ...

.

The projected overall 30,000 marks were much too little, so some months later Jerusalem's Association withdrew from co-financing the project, it regarded to be nonserious. In 1899 Voigt declared the site to be too small for a community centre and a church, as was plannedEisler 1997, p. 132. The congregation then spent with Braun's consent his donation of 10,000 marks for Heilpern's house (today's Rechov Beer-Hofmann #9), to become the school and rectory, for the latter of which it also serves today's congregation. However, then the German vice-consulate, still resided in that house and Consul Edmund Schmidt asked to be allowed to further stay there until the new, still-existing vice-consulate in today's Rechov Eilath # 59 would be completed. So the school stayed ad interim with Ustinov's "HûÇtel du Parc". Metzler's former site in then Wilhelmstraûe (today's Rechov Beer-Hofmann #15) was thus reserved for a future solitary church building.

In April 1900 Pastor Schlaich and his wife moved into Heilpern's house, as well as the school with its 30 pupils, among them Catholic and Jewish pupils, but no Templers, from Jaffa and neighbouring Neveh Tzedeq and . In November 1917 the school had been closed by the Britons. All the property of the congregation, Jerusalem's Association and of parishioners of German and other enemy nationality was taken into public custodianship. With the establishment of a regular British administration in 1918 Edward Keith-Roach

Edward Keith-Roach (Born 1885 Gloucester, England - died 1954). Keith-Roach was the British Colonial administrator during the British mandate on Palestine, who also served as the governor of Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, æø¯æ´æø¥æˋø ...

became the ''Public Custodian of Enemy Property in Palestine'', who rented out the property and collected the rents, until the property was finally returned to its actual proprietors in 1925.Foerster 1991, p. 138.

On 14 April 1918 John Mott

John Raleigh Mott (May 25, 1865 ã January 31, 1955) was an evangelist and long-serving leader of the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) and the World Student Christian Federation (WSCF). He received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1946 for hi ...

and J. H. Oldham, two oecumenists, founded the ''Emergency Committee of Cooperating Missions'', Mott becoming the president and Oldham the secretary. Mott and Oldham succeeded to get Art. 438 into the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traitûˋ de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

, so that the property of German missions would be excepted from being expropriated for German reparations for World War I.LûÑffler 2001, p. 194. Jerusalem's Association and the Evangelical Jerusalem Foundation had meanwhile appointed the Swedish Lutheran Archbishop Nathan SûÑderblom

Lars Olof Jonathan SûÑderblom (; 15 January 1866 – 12 July 1931) was a Swedish clergyman. He was the Church of Sweden Archbishop of Uppsala between 1914 and 1931, and recipient of the 1930 Nobel Peace Prize. He is commemorated in the Cale ...

their speaker at the Britons.

In May 1919 Jerusalem's Association informed the ''Reich's commissioner on Germans as enemy nationals abroad'', that its loss of property in the Holy Land amounted to 891,785 marks at its pre-war rate (about ôÈ44,589.25 or $212,329.76). The Treaty of Versailles, signed on 28 June 1919, finally became effective on 10 January 1920 and thus legalised the existing British custodianship of the property of the congregation, the parishioners and Jerusalem's Association. The schools of Jerusalem's Association were reopened under British government management in 1920. In April 1920 the Allies convened at the Conference of San Remo and agreed on the British rule in Palestine, followed by the official establishment of the civil administration on 1 July 1920. From that date on Keith-Roach transferred the collected rents for property in custodianship to the actual proprietors. The League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Sociûˋtûˋ des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

legitimised this by granting a mandate to Britain in 1922 and Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Tû¥rkiye ), officially the Republic of Tû¥rkiye ( tr, Tû¥rkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula in ...

, the Ottoman successor, finally legalised the British Mandate by the Treaty of Lausanne, signed on 24 July 1923 and becoming effective on 5 August 1925. Thus the public custodianship ended in the same year and the prior holders achieved the fully protected legal position as proprietors. Jerusalem's Association applied for registration as Palestinian legal entity, granted in 1928.

Jerusalem's Association resumed its own schools and its school in Jaffa, held in condominium with the Templers, however, Provost Rhein complained about the decline of pupils in the Evangelical schools, whose parents were German, Austrian or other German-speaking Jews, especially in the difficult years of 1931 and 1932.

Starting in 1933 the new German Nazi government tried to get the German schools in the Holy Land under its influence, using again the dependence of the school providers on transfers from Germany. Oertzen and Rhein fought the deconfessionalisation of the Evangelical schools. Provost Rhein succeeded to resist the merger of the remaining Evangelical schools with Templer schools until 1937, on which occasion they became paganised, teaching the pupils Nazi ''Weltanschauung

A worldview or world-view or ''Weltanschauung'' is the fundamental cognitive orientation of an individual or society encompassing the whole of the individual's or society's knowledge, culture, and point of view. A worldview can include natural ...

''. In order to regain influence on the curriculum, Rhein then tried to join the Palestinian section of the National Socialist Teachers League

The National Socialist Teachers League (German: , NSLB), was established on 21 April 1929. Its original name was the Organization of National Socialist Educators. Its founder and first leader was former schoolteacher Hans Schemm, the Gauleiter ...

(NSLB), but Palestinian NSLB president Dr. Kurt Hegele refused Rhein's membership. So by 1938 all Gentile teachers of German nationality had joined the NSLB, except of Rhein and some further Evangelical missionary .

After the begin of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countriesãincluding all of the great powersãforming two opposi ...

in September 1939 all property of the Jaffa congregation, of its parishioners of German or other enemy nationality and of Jerusalem's Association were submitted to the ''Custodian of Enemy Property'', Keith-Roach again, and the schools were supervised by the ''Committee for Supervision of German Educational Institutions'' under the Anglican bishop of Jerusalem, George Francis Graham Brown. With the internment of all Jaffa parishioners of German or other enemy nationality in 1940 the premises and houses in Jaffa were confiscated by the Mandatory government. Later the Anglican Church's Ministry Among Jewish People used the Immanuel Church for its services until 1947. The State of Israel, with Jaffa belonging to its state territory, succeeded the mandatory government in this custodianship in May 1948, however, excluding the building of Immanuel Church proper, since the new state did not seize places of worship.

Church building

History

After in 1899 the first construction works of a combined Evangelical church, community centre and school ended, with the cornerstone having been laid in November 1898, Jerusalem's Association returned as partner and financier of the church and commissioned Paul Ferdinand Groth (1859ã1955), architect of Jerusalem's Evangelical Church of the Redeemer and renovator ofAll Saints' Church, Wittenberg

All Saints' Church, commonly referred to as ''Schlosskirche'' (Castle Church) to distinguish it from the '' Stadtkirche'' (Town Church) of St. Mary's ã and sometimes known as the Reformation Memorial Church ã is a Lutheran church in Wittenberg, ...

, by the end of 1901 to design plans for the future solitary Immanuel Church.

Stuttgart's Court Preacher Braun started a fund-raising campaign, also attended by Grand Duchess Vera Constantinovna of Russia

Grand Duchess Vera Konstantinovna of Russia (16 February 1854 ã 11 April 1912), ) was a daughter of Grand Duke Konstantine Nicholaievich of Russia. She was a granddaughter of Tsar Nicholas I and first cousin of Tsar Alexander III of Russia. ...

, the niece and adoptee of the late Wû¥rttembergian Queen Olga and King Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742ã814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226ã1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

, to collect the needed funds, with Braun and his wife themselves donating 25,000 marks. In 1902 the Ottoman authorities recognised the construction site in then ''Wilhelmstraûe'' (today's ''Rechov Beer-Hofmann'' #15) as religious property, including its liberation from property tax

A property tax or millage rate is an ad valorem tax on the value of a property.In the OECD classification scheme, tax on property includes "taxes on immovable property or net wealth, taxes on the change of ownership of property through inhe ...

.

After Jerusalem's Association threatened to choose another architect, if Groth would not downsize his plans to a less costly project, Groth provided plans for a cheaper church at the begin of 1903.Eisler 1997, p. 134. Jerusalem's Association then commissioned the architect and Templer Benjamin Sandel (1877ã1941), then leading the constructions of the Hagia Maria Sion Abbey in Jerusalem and son of the late Theodor Sandel, as supervisor, and the Templer Johannes Wennagel (1846ã1927) from Sarona as building contractor, starting excavation on 11 May 1903, however, constructions progressed only slowly because Groth was late with sending the detailed plans, only completely arriving in February 1904. Groth then waived any honorary.

Braun, the most prominent donor for the congregation and church, travelled on behalf of Jerusalem's Association from Stuttgart to Jaffa to attend the inauguration of Immanuel Church, scheduled for Pentecost 1904 (May 22). Unfortunately he contracted dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

after his arrival and died hospitalised in Jerusalem on 31 May 1904.Eisler 1997, p. 135. He was buried on the Anglo-Prussian simultaneous Anglican-Evangelical Cemetery on Mount Zion, close to Samuel Gobat

Samuel Gobat (26 January 1799 ã 11 May 1879) was a Swiss Calvinist who became an Anglican missionary in Africa and was the Protestant Bishop of Jerusalem from 1846 until his death.

Biography

Samuel Gobat was born at Crûˋmines, Canton of Bern, ...

's grave.Eisler 1997, p. 136.

The inauguration of Immanuel Church was then delayed to Monday June 6, held as a sober ceremony and attended by Bû¥ge, participants from other Evangelical congregations, and Templers. A year later on June 6 celebrated a memorial service for Braun.

Description

The walls are built from two kinds of natural stone, a yellowish-grey type ofsandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicates ...

quarried close to Jaffa and a limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms whe ...

, the so-called Meliki

Meliki ( el, ööçö£ö₤ö¤öñ) is a village and a former municipality in Imathia, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Alexandreia, of which it is a municipal unit. The municipal unit has an area of 98.962&nbs ...

, from the mountains at Bir Nabala

Bir Nabala ( ar, Ä´ìÄÝ ìÄ´ÄÏìÄÏ; he, æææ´ æ ææææ) is a Palestinian enclave town in the West Bank located eight kilometers northeast of Jerusalem. In mid-year 2006, it had an estimated population of 6,100 residents. Three Bedouin tribe ...

. The roof is covered with tiles from Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-RhûÇne and capital of the Provence-Alpes-CûÇte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Fra ...

.

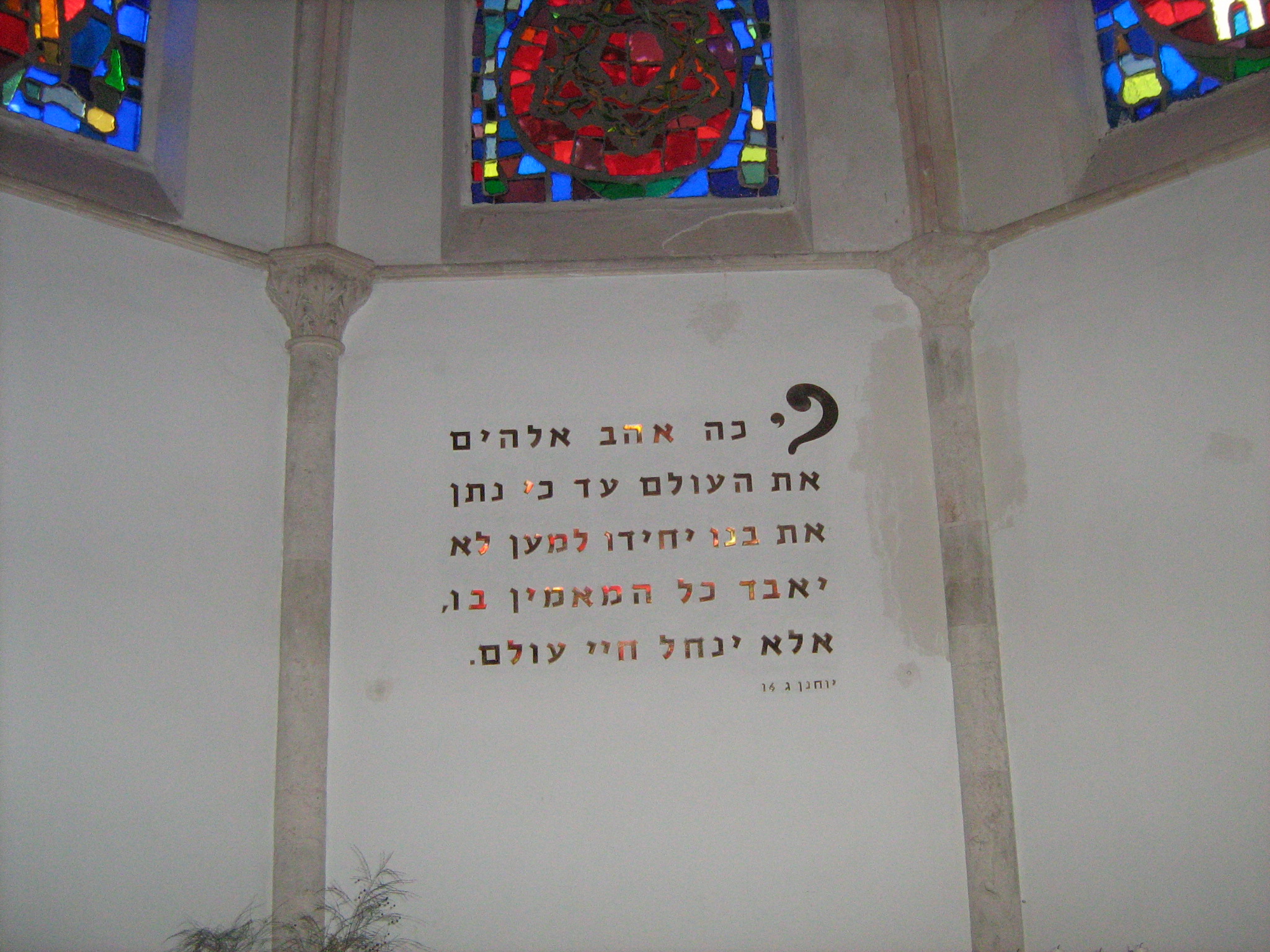

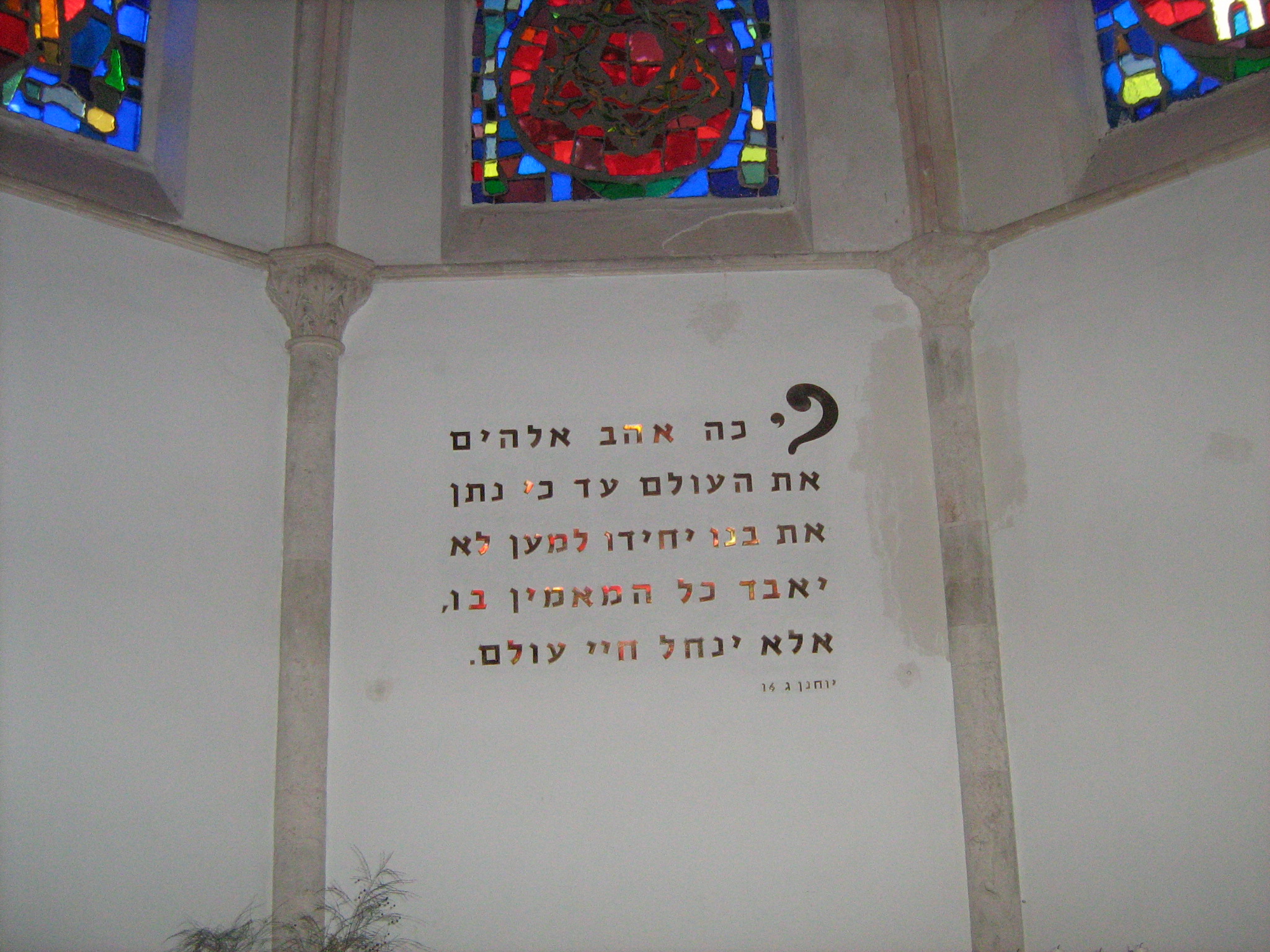

The interior of the approximately oriented prayer hall is covered by

The interior of the approximately oriented prayer hall is covered by cross vault

A groin vault or groined vault (also sometimes known as a double barrel vault or cross vault) is produced by the intersection at right angles of two barrel vaults. Honour, H. and J. Fleming, (2009) ''A World History of Art''. 7th edn. London: L ...

s, on its northern side a pipe organ was installed on a loft.

The tower, housing a staircase, flanks the northern side aisle and the westernmost bay of the main nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

.

Furnishings

The furnishings were mostly imported from Germany. King

The furnishings were mostly imported from Germany. King William II of Wû¥rttemberg

, spouse =

, issue = Pauline, Princess of WiedPrince Ulrich

, house = Wû¥rttemberg

, father = Prince Frederick of Wû¥rttemberg

, mother = Princess Catherine of Wû¥rttemberg

, birth_date =

, birth_place = St ...

and Queen Charlotte

Charlotte ( ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of North Carolina. Located in the Piedmont region, it is the county seat of Mecklenburg County. The population was 874,579 at the 2020 census, making Charlotte the 16th-most populo ...

donated the church clock. In his function as ''summus episcopus'' of the Evangelical State Church of Prussia's older Provinces King William II of Prussia (also German Emperor) and his wife Auguste Victoria donated the main bell with the inscription "Gestiftet von S.M. d.K.u.K. Wilhelm II u. I.M. d.K.u.K. Auguste Victoria 1904/Zweifle nicht! Ap. Gesch. 10.20".

The , with Auguste Victoria as its protectress, donated the small bells. She also donated the altar bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts ...

with her handwritten dedication: "Ja kommet her zu mir alle, die ihr mû¥hselig und beladen seid; ich will Euch erquicken."

Miss Neef from Stuttgart financed the altar and the pulpit, while Ustinov granted the congregation a great crucifix from olive tree wood. The parishioners collected 4,050 francs for the pipe organ, produced by Walcker Orgelbau

Walcker Orgelbau (also known as E. F. Walcker & Cie.) of Ludwigsburg, Baden-Wû¥rttemberg, Germany, is a builder of pipe organs. It was founded in Cannstatt, a suburb of Stuttgart in 1780 by . His son Eberhard Friedrich Walcker moved the business t ...

in Ludwigsburg

Ludwigsburg (; Swabian: ''Ludisburg'') is a city in Baden-Wû¥rttemberg, Germany, about north of Stuttgart city centre, near the river Neckar. It is the largest and primary city of the Ludwigsburg district with about 88,000 inhabitants. It is s ...

. The stained glass windows were a product of in Quedlinburg

Quedlinburg () is a town situated just north of the Harz mountains, in the district of Harz in the west of Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. As an influential and prosperous trading centre during the early Middle Ages, Quedlinburg became a center of in ...

. In 1906 a plaque commemorating Friedrich Braun was fixed on the walls of Immanuel Church.

In 1977 Immanuel Church underwent a renovation, replacing the old windows and the pipe organ. The Norwegian Victor Sparre

Victor Sparre (nûˋ Smith; 4 November 1919 ã 16 March 2008) was a Norwegian painter, glass designer and non-fiction writer.

Personal life

Sparre was born in BûÎrum as the son of librarian Victor Alf Smith and Eli Sparre. He was married to nurse A ...

created the new windows of stained glass. (*1903ã1991*) from GûÑttingen

GûÑttingen (, , ; nds, ChûÑttingen) is a university city in Lower Saxony, central Germany, the capital of the eponymous district. The River Leine runs through it. At the end of 2019, the population was 118,911.

General information

The ori ...

created the new pipe organ in 1977. The apse

In architecture, an apse (plural apses; from Latin 'arch, vault' from Ancient Greek 'arch'; sometimes written apsis, plural apsides) is a semicircular recess covered with a hemispherical vault or semi-dome, also known as an '' exedra''. ...

is decorated by an inscription of the Hebrew verse from the Gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message (" the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words a ...

of John the Evangelist

John the Evangelist ( grc-gre, Ã¥¡üö˜ö§ö§öñü, IéûÀnnás; Aramaic: ÉÉÉÉÂÉÂ; Ge'ez: ÃÛÃÃÃç; ar, ììÄÙìÄÏ ÄÏìÄËìĘììì, la, Ioannes, he, ææææ æ cop, ãýãýÝãýãýãýãýãýË or ãýãýÝä

ãý) is the name traditionally given ...

:

"ææ ææ æææ æææææ ææˆ ææÂæææ æÂæ ææ æ æˆæ ææˆ ææ æ æææææ æææÂæ ææ ææææ ææ ææææææ ææ, æææ ææ ææ æææ æÂæææ."

Second congregation (1955ãpresent)

On 29 August 1951 the State of Israel and theLutheran World Federation

The Lutheran World Federation (LWF; german: Lutherischer Weltbund) is a global communion of national and regional Lutheran denominations headquartered in the Ecumenical Centre in Geneva, Switzerland. The federation was founded in the Swedish ...

, which took care of the formerly German Protestant missionary property in Israel, found an agreement on compensation for the lost missionary property and the future use of the actual places of worship.

In 1955, the Lutheran World Federation, deciding in consent with the Evangelical Church in Germany

The Evangelical Church in Germany (german: Evangelische Kirche in Deutschland, abbreviated EKD) is a federation of twenty Lutheran, Reformed (Calvinist) and United (e.g. Prussian Union) Protestant regional churches and denominations in German ...

, the new umbrella of German church bodies taking care of their foreign efforts, and the Jerusalem's Association (with its vice-president Rabenau), handed over Immanuel Church to the .

Today a number of congregations besides the Lutheran are using the church.

The present Lutheran congregation is composed of a wide range of believers in Jesus from many different denominations. Some are either permanent residents or citizens of Israel and others are temporary workers in the country. All come together to worship and to affirm their common life together in meals, prayer, bible study and simple fellowship, both in regular services and throughout the week.

Church access and worship times

The church is open to visitors through the week. People of all faiths, and none, are most welcome. The regular worship times are 11 am each Saturday (Shabbat) held in Hebrew and English, and at 10 am each Sunday in English. The Sacrament of Holy Communion is celebrated at almost all services which also have a strong element of bible teaching. Services are relatively informal and worshippers meet afterwards to share their experiences and meet visitors.Concerts

Immanuel Church is used frequently for concerts of music, generally (but not exclusively) from the classical genre. The organ of the church is regarded as one of the best in the country and plays a big part in concerts, as well as its key use in regular worship.Missionaries and pastors (1858ãpresent)

* 1858ã1870: Missionary (*1824ã1907*)

* 1866ã1886?: Pastor Johannes Gruhler (*1833ã1905*), only partially accepted due to his Anglican Rite

* 1870/1886ã1897: vacant

** 1885ã1895: Pastor Carl Schlicht (*1855ã1930*) in Jerusalem, per pro

* 1897ã1906: Pastor Albert Eugen Schlaich (*1870ã1954*)

* 1906ã1912: Pastor Wilhelm Georg Albert Zeller (*1879ã1929*)

* 1912ã1917: Pastor (*1884ã1959*)

* 1917ã1920 (in Egyptian exile): Pastor von Rabenau continued to serve the interned parishioners

* 1917ã1926 (for the parishioners remaining in Jaffa): vacant

** 1917ã1918: D. Dr. Friedrich Jeremias (*1868ã1945*), Provost of Jerusalem, per pro

** 1921: Prof. D. Dr.

* 1858ã1870: Missionary (*1824ã1907*)

* 1866ã1886?: Pastor Johannes Gruhler (*1833ã1905*), only partially accepted due to his Anglican Rite

* 1870/1886ã1897: vacant

** 1885ã1895: Pastor Carl Schlicht (*1855ã1930*) in Jerusalem, per pro

* 1897ã1906: Pastor Albert Eugen Schlaich (*1870ã1954*)

* 1906ã1912: Pastor Wilhelm Georg Albert Zeller (*1879ã1929*)

* 1912ã1917: Pastor (*1884ã1959*)

* 1917ã1920 (in Egyptian exile): Pastor von Rabenau continued to serve the interned parishioners

* 1917ã1926 (for the parishioners remaining in Jaffa): vacant

** 1917ã1918: D. Dr. Friedrich Jeremias (*1868ã1945*), Provost of Jerusalem, per pro

** 1921: Prof. D. Dr. Gustaf Dalman

Gustaf Hermann Dalman (9 June 1855 ã 19 August 1941) was a German Lutheran theologian and orientalist. He did extensive field work in Palestine before the First World War, collecting inscriptions, poetry, and proverbs. He also collected physic ...

, provost per pro