Ibn Wahshiyya on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

( ar, ابن وحشية), died , was a

Kitāb Shawq al-mustahām fī maʿrifat rumūz al-aqlām

(1791) * * {{Authority control Alchemists of the medieval Islamic world Arab historians Wahshiyah, Ibn 9th-century Arabs 10th-century Arabs 10th-century Arabic writers 9th-century Arabic writers 10th-century agronomists

Nabataean

The Nabataeans or Nabateans (; Nabataean Aramaic: , , vocalized as ; Arabic: , , singular , ; compare grc, Ναβαταῖος, translit=Nabataîos; la, Nabataeus) were an ancient Arab people who inhabited northern Arabia and the southern L ...

(Aramaic

The Aramaic languages, short Aramaic ( syc, ܐܪܡܝܐ, Arāmāyā; oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; tmr, אֲרָמִית), are a language family containing many varieties (languages and dialects) that originated i ...

-speaking, rural Iraqi) agriculturalist

An agriculturist, agriculturalist, agrologist, or agronomist (abbreviated as agr.), is a professional in the science, practice, and management of agriculture and agribusiness. It is a regulated profession in Canada, India, the Philippines, the ...

, toxicologist, and alchemist

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim ...

born in Qussīn, near Kufa

Kufa ( ar, الْكُوفَة ), also spelled Kufah, is a city in Iraq, about south of Baghdad, and northeast of Najaf. It is located on the banks of the Euphrates River. The estimated population in 2003 was 110,000. Currently, Kufa and Najaf a ...

in Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

. He is the author of the '' Nabataean Agriculture'' (), an influential Arabic work on agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people ...

, astrology

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Di ...

, and magic.

Already by the end of the tenth century, various works were being falsely attributed to him. One of these spurious writings, the ("The Book of the Desire of the Maddened Lover for the Knowledge of Secret Scripts", perhaps ), is notable as an early proposal that some Egyptian hieroglyphs

Egyptian hieroglyphs (, ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt, used for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with some 1,000 distinct characters.There were about 1, ...

could be read phonetic

Phonetics is a branch of linguistics that studies how humans produce and perceive sounds, or in the case of sign languages, the equivalent aspects of sign. Linguists who specialize in studying the physical properties of speech are phoneticians. ...

ally, rather than only logograph

In a written language, a logogram, logograph, or lexigraph is a written character that represents a word or morpheme. Chinese characters (pronounced ''hanzi'' in Mandarin, '' kanji'' in Japanese, '' hanja'' in Korean) are generally logograms, ...

ically.

Name

His full name was . Just like the semi-legendaryJabir ibn Hayyan

Abū Mūsā Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (Arabic: , variously called al-Ṣūfī, al-Azdī, al-Kūfī, or al-Ṭūsī), died 806−816, is the purported author of an enormous number and variety of works in Arabic, often called the Jabirian corpus. The ...

, he carried the despite the fact that he is not known to have engaged in or to have written anything about Sufism

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality ...

. The is a variant of ( 'Chaldaean'), a term referring to the native inhabitants of Mesopotamia that was also used in Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, but (given the known -shd-/-ld- variation in Babylonian language) may perhaps be based on a living oral tradition indigenous to Iraq.

Biography

Ibn Wahshiyya was likely born in (Iraq) and died in the year 318 of theIslamic calendar

The Hijri calendar ( ar, ٱلتَّقْوِيم ٱلْهِجْرِيّ, translit=al-taqwīm al-hijrī), also known in English as the Muslim calendar and Islamic calendar, is a lunar calendar consisting of 12 lunar months in a year of 354 ...

(). Very little else is known about his life. Our main source of information are Ibn Wahshiyya's own writings, as well as the short entry in Ibn al-Nadim

Abū al-Faraj Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq al-Nadīm ( ar, ابو الفرج محمد بن إسحاق النديم), also ibn Abī Ya'qūb Isḥāq ibn Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq al-Warrāq, and commonly known by the ''nasab'' (patronymic) Ibn al-Nadīm ...

's (died ) , where he is explicitly said to be among the "authors whose life is not well known". Ibn Wahshiyya himself claimed to be a descendant of the Neo-Assyrian king Sennacherib

Sennacherib ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: or , meaning " Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Sargon II in 705BC to his own death in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynas ...

(), whom the rural, Aramaic

The Aramaic languages, short Aramaic ( syc, ܐܪܡܝܐ, Arāmāyā; oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; tmr, אֲרָמִית), are a language family containing many varieties (languages and dialects) that originated i ...

-speaking population of southern Iraq (known to Arabic authors of Ibn Wahshiyya's time as 'Nabataeans') revered as their illustrious ancestor. Despite the fact that these Iraqi 'Nabataeans' (who are not to be confused with the ancient Nabataeans

The Nabataeans or Nabateans (; Nabataean Aramaic: , , vocalized as ; Arabic language, Arabic: , , singular , ; compare grc, Ναβαταῖος, translit=Nabataîos; la, Nabataeus) were an ancient Arab people who inhabited northern Arabian Pe ...

of Petra

Petra ( ar, ٱلْبَتْرَاء, Al-Batrāʾ; grc, Πέτρα, "Rock", Nabataean: ), originally known to its inhabitants as Raqmu or Raqēmō, is an historic and archaeological city in southern Jordan. It is adjacent to the mountain of Ja ...

, with whom they have nothing in common) were generally looked down upon as lowly peasants, Ibn Wahshiyya identified himself as one of them. Ibn Wahshiyya's self-identifaction as 'Nabataean' seems credible given the accurate use of Aramaic terms in his works.

Works

Ibn Wahshiyya's works were written down and redacted after his death by his student and scribe Abū Ṭālib al-Zayyāt. They were used not only by later agriculturalists, but also by authors of works on magic like Maslama al-Qurṭubī (died 964, author of the '' Ghāyat al-ḥakīm'', "The Aim of the Sage", Latin: ''Picatrix''), and by philosophers likeMaimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah ...

(1138–1204) in his ''Dalālat al-ḥāʾirīn'' ("Guide for the Perplexed", c. 1190).

Ibn al-Nadim

Abū al-Faraj Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq al-Nadīm ( ar, ابو الفرج محمد بن إسحاق النديم), also ibn Abī Ya'qūb Isḥāq ibn Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq al-Warrāq, and commonly known by the ''nasab'' (patronymic) Ibn al-Nadīm ...

, in his ''Kitāb al-Fihrist

The ''Kitāb al-Fihrist'' ( ar, كتاب الفهرست) (''The Book Catalogue'') is a compendium of the knowledge and literature of tenth-century Islam compiled by Ibn Al-Nadim (c.998). It references approx. 10,000 books and 2,000 authors.''The ...

'' (c. 987), lists approximately twenty works attributed to Ibn Wahshiyya. However, most of these were probably not written by Ibn Wahshiyya himself, but rather by other tenth-century authors inspired by him.

The ''Nabataean Agriculture''

Ibn Wahshiyya's major work, the '' Nabataean Agriculture'' (''Kitāb al-Filāḥa al-Nabaṭiyya'', c. 904), claims to have been translated from an "ancient Syriac" original, written c. 20,000 years ago by the ancient inhabitants ofMesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

. In Ibn Wahshiyya's time, Syriac was thought to have been the primordial language used at the time of creation. While the work may indeed have been translated from a Syriac original, in reality Syriac is a language that only emerged in the first century. By the ninth century, it had become the carrier of a rich literature, including many works translated from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

. The book's extolling of Babylonian civilization against that of the conquering Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

forms part of a wider movement (the '' Shu'ubiyya'' movement) in the early Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Mutta ...

period (750-945 CE), which witnessed the emancipation of non-Arabs from their former status as second-class Muslims.

Other Works

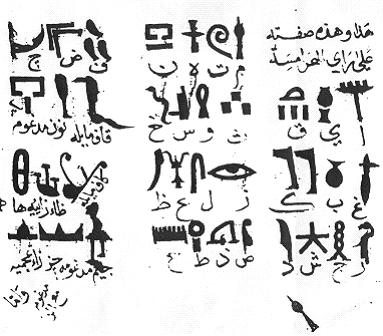

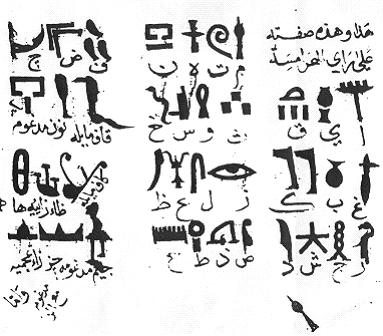

''The Book of the Desire of the Maddened Lover for the Knowledge of Secret Scripts''

One of the works attributed to Ibn Wahshiyya is the ("The Book of the Desire of the Maddened Lover for the Knowledge of Secret Scripts”), a work dealing amongst other things withEgyptian hieroglyphs

Egyptian hieroglyphs (, ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt, used for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with some 1,000 distinct characters.There were about 1, ...

. Its author refers to his extensive travels in Egypt, but Ibn Wahshiyya himself seems never to have visited Egypt, a country which he barely even mentions in his authentic works. For this and other reasons, scholars believe the work to be spurious

Spurious may refer to:

* Spurious relationship in statistics

* Spurious emission or spurious tone in radio engineering

* Spurious key in cryptography

* Spurious interrupt in computing

* Spurious wakeup in computing

* ''Spurious'', a 2011 novel b ...

. According to Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila, it may have been authored by Hasan ibn Faraj, an obscure descendant of the Harranian Sabian scholar Sinan ibn Thabit ibn Qurra () who claimed to have merely copied the work in the year 413 AH, corresponding to 1022–3 CE.

''The Book of Poisons''

Another work attributed to Ibn Wahshiyya is a treatise on toxicology called the ''Book of Poisons'', which combines contemporary knowledge onpharmacology

Pharmacology is a branch of medicine, biology and pharmaceutical sciences concerned with drug or medication action, where a drug may be defined as any artificial, natural, or endogenous (from within the body) molecule which exerts a biochemica ...

with magic and astrology.

Cryptography

The works attributed to Ibn Wahshiyya contain several cipher alphabets that were used to encrypt magic formulas.Later influence

Pseudo

The prefix pseudo- (from Greek ψευδής, ''pseudes'', "false") is used to mark something that superficially appears to be (or behaves like) one thing, but is something else. Subject to context, ''pseudo'' may connote coincidence, imitation, ...

-Ibn Wahshiyya's ("The Book of the Desire of the Maddened Lover for the Knowledge of Secret Scripts", perhaps , see above), has been claimed by Egyptologist Okasha El-Daly to have correctly identified the phonetic

Phonetics is a branch of linguistics that studies how humans produce and perceive sounds, or in the case of sign languages, the equivalent aspects of sign. Linguists who specialize in studying the physical properties of speech are phoneticians. ...

value of a number of Egyptian hieroglyphs

Egyptian hieroglyphs (, ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt, used for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with some 1,000 distinct characters.There were about 1, ...

. However, other scholars have been highly sceptical about El-Daly's claims on the accuracy of these identifications, which betray a keen interest in (as well as some basic knowledge of) the nature of Egyptian hieroglyphs, but are in fact for the most part incorrect.

The book may have been known to the German Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

scholar and polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

Athanasius Kircher

Athanasius Kircher (2 May 1602 – 27 November 1680) was a German Jesuit scholar and polymath who published around 40 major works, most notably in the fields of comparative religion, geology, and medicine. Kircher has been compared to fe ...

(1602–1680), and was translated into English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

by Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall in 1806 as ''Ancient Alphabets and Hieroglyphic Characters Explained; with an Account of the Egyptian Priests, their Classes, Initiation, and Sacrifices in the Arabic Language by Ahmad Bin Abubekr Bin Wahishih''.. Cf. .

See also

*Alchemy

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim wo ...

* Alchemy and chemistry in the medieval Islamic world

*History of agriculture

Agriculture began independently in different parts of the globe, and included a diverse range of taxa. At least eleven separate regions of the Old and New World were involved as independent centers of origin.

The development of agriculture a ...

*Ibn Abi Usaybi'a

Ibn Abī Uṣaybiʿa Muʾaffaq al-Dīn Abū al-ʿAbbās Aḥmad Ibn Al-Qāsim Ibn Khalīfa al-Khazrajī ( ar, ابن أبي أصيبعة; 1203–1270), commonly referred to as Ibn Abi Usaibia (also ''Usaibi'ah, Usaybea, Usaibi`a, Usaybiʿah'' ...

* Muslim Agricultural Revolution

*Science in the medieval Islamic world

Science in the medieval Islamic world was the science developed and practised during the Islamic Golden Age under the Umayyads of Córdoba, the Abbadids of Seville, the Samanids, the Ziyarids, the Buyids in Persia, the Abbasid Caliphate ...

* ''The Nabataean Agriculture'' (Ibn Wahshiyya's major work)

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Kitāb Shawq al-mustahām fī maʿrifat rumūz al-aqlām

(1791) * * {{Authority control Alchemists of the medieval Islamic world Arab historians Wahshiyah, Ibn 9th-century Arabs 10th-century Arabs 10th-century Arabic writers 9th-century Arabic writers 10th-century agronomists