Background

Pérez and Caldera administrations

When world oil prices 1980s oil glut, collapsed in the 1980s, the economy contracted, and. Indexmundi. 2010. Retrieved 16 August 2010. In 1989, the inflation rate peaked at 84%. The same year, following a cut in government spending and the opening of markets by President Carlos Andrés Pérez, the capital city of Caracas suffered from Caracazo, looting and rioting. After Pérez initiated liberal economic policies and made Venezuelan markets Free market, more free, Venezuela's GDP increased from a −8.3% decline in 1989 to 4.4% in 1990 and 9.2% in 1991, though wages remained low and unemployment remained high among Venezuelans. While some claim that liberalization was the cause of Venezuelan economic difficulties, an over-reliance on oil prices and a fractured political system have been identified to have caused many of the problems. By the mid-1990s under President Rafael Caldera, Venezuela saw annual inflation rates of 50 to 60% from 1993 to 1997, with an exceptional peak of 100% in 1996. The percentage of people living in poverty rose from 36% in 1984 to 66% in 1995, with the country suffering Venezuelan banking crisis of 1994, a severe banking crisis in 1994. In 1998, the economic crisis had worsened, with GDP per capita at the same level as it was in 1963 (after adjusting 1963 dollars to 1998 value), down a third from its peak in 1978; the purchasing power of the average salary was a third of its 1978 level.

Chávez and Maduro administrations

Following the 1998 Venezuelan presidential election, the inflation rate, measured by consumer price index, was 35.8% in 1998, falling to a low of 12.5% in 2001 but rising to 31.1% in 2003. In an attempt to support the Venezuelan bolívar, bolster the government's declining level of international reserves, and mitigate the impact of the oil industry work stoppage on the economy, the Ministry of Finance (Venezuela), Ministry of Finance and the Central Bank of Venezuela (BCV) suspended foreign exchange trading on 23 January 2003. On 6 February, the government created CADIVI, a currency-control board charged with handling foreign exchange procedures. The board set the USD exchange rate at 1,596 bolívares to the dollar for purchases and 1,600 to the dollar for sales. The Venezuela economy, Venezuelan economy shrank 5.8% in the first three months of 2010 compared to the same period in 2009,Toothaker, Christopher

The Venezuela economy, Venezuelan economy shrank 5.8% in the first three months of 2010 compared to the same period in 2009,Toothaker, Christopher"Chavez: Venezuela's economy soon to recover"

. Bloomberg Businessweek. 8 August 2010. Retrieved 3 September 2010. and had the highest inflation rate in Latin America at 30.5%. President Hugo Chávez expressed optimism that Venezuela would emerge from recession despite International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasts that Venezuela would be the only country in the region to remain in recession that year. The IMF categorized the economic recovery of Venezuela as "delayed and weak" in comparison with other countries in the region."FMI: Venezuela único país cuya economía se contraerá este año"

. El Universal. 21 April 2010. Retrieved 3 September 2010. Following Chávez's death in early 2013, the country's economy continued to fall into an even greater recession. The annual inflation rate for consumer prices has increased by hundreds and thousands of percentage points during the crisis. Inflation rates remained high during Chávez's presidency. By 2010, inflation had removed any advancement of wage increases. By 2014, it was the highest in the world at 69%. By 2016, the media reported that Venezuelan Economic Collapse of 2016, Venezuela was suffering an economic collapse. The IMF estimated a 500% inflation rate and a 10% contraction in GDP.

History

Maduro administration

In November 2016, Venezuela entered a period of2018 inflation estimate

In 2018, the IMF estimated that Venezuela's inflation rate would reach 1,000,000% by the end of the year. This forecast was criticized by economist Steve Hanke, who claimed that the IMF had released a "bogus forecast" because "no one has ever been able to accurately forecast the course or the duration of an episode of hyperinflation. But that has not stopped the IMF from offering inflation forecasts for Venezuela that have proven to be wildly inaccurate". According to Hanke, Venezuela's inflation rate on 31 July 2018 was 33,151%, suggesting that "Venezuela is now experiencing the 23rd most severe episode of hyperinflation in history." The IMF reported that the inflation rate for 2018 reached 929,790%, slightly below the original 1,000,000% estimate.2019 inflation estimate

In October 2018, the IMF estimated that the inflation rate would reach 10,000,000% by the end of 2019, which was again mentioned in its April 2019 World Economic Outlook report.2021 inflation estimate

In December 2021, economists and the Central Bank of Venezuela announced that Venezuela would reach in the first quarter of 2022 more than 12 months with monthly inflation below 50% after more than four years of a hyperinflationary cycle, which would technically indicate its exit from hyperinflation, but its consequences remained by that date.Causes

A monetarist view is that a general increase in the prices of things is less a commentary on the worth of those things than on the worth of the money. This has objective and subjective components:

*Objectively, that the money has no firm basis to give it a value.

*Subjectively, that the people holding the money lack confidence in its ability to retain its value.

According to experts, Venezuela's economy began to experience hyperinflation during the first year of Nicolás Maduro's presidency. Potential causes of the hyperinflation include heavy money-printing and deficit spending. In April 2013, the month Maduro took office, the annual inflation rate was 29.4%, only 0.1% less than the rate in 1999 when Hugo Chávez took office. By April 2014, the annual inflation rate was 61.5%. In early 2014, the BCV did not release statistics for the first time in its history, with ''Forbes'' reporting that it was a possible way to manipulate the image of economy. In April 2014, the IMF stated that economic activity in Venezuela was uncertain but may continue to slow, and that "loose macroeconomic policies have generated high inflation and a drain on official foreign exchange reserves". The IMF suggested that "more significant policy changes are needed to stave off a disorderly adjustment". According to economist Steve Hanke, Venezuela's current economy, as of March 2014, had an inflation rate hovering above 300%, an official inflation rate around 60%, and a product scarcity index rising above 25% of goods. The Venezuelan government did not report inflation data for September and October 2014.

The growth in the BCV's money supply accelerated during the beginning of Maduro's presidency, which increased price inflation in the country. The money supply of the bolívar fuerte in Venezuela increased 64% in 2014, three times faster than any other economy observed by Bloomberg News at the time. Due to the rapidly decreasing value of the bolívar fuerte, Venezuelans jokingly called it "bolívar muerto" ("dead bolívar").

Maduro has blamed capitalist speculation for driving high inflation rates and creating widespread shortages of basic necessities. He has said he is fighting an "economic war", referring to newly enacted economic measures as "economic offensives" against political opponents, who, according to Maduro and his loyalists, are behind an international economic conspiracy. Maduro has been criticized for concentrating on public opinion instead of tending to practical issues that have been warned by economists, or creating solutions to improve Venezuela's economic prospects.

A monetarist view is that a general increase in the prices of things is less a commentary on the worth of those things than on the worth of the money. This has objective and subjective components:

*Objectively, that the money has no firm basis to give it a value.

*Subjectively, that the people holding the money lack confidence in its ability to retain its value.

According to experts, Venezuela's economy began to experience hyperinflation during the first year of Nicolás Maduro's presidency. Potential causes of the hyperinflation include heavy money-printing and deficit spending. In April 2013, the month Maduro took office, the annual inflation rate was 29.4%, only 0.1% less than the rate in 1999 when Hugo Chávez took office. By April 2014, the annual inflation rate was 61.5%. In early 2014, the BCV did not release statistics for the first time in its history, with ''Forbes'' reporting that it was a possible way to manipulate the image of economy. In April 2014, the IMF stated that economic activity in Venezuela was uncertain but may continue to slow, and that "loose macroeconomic policies have generated high inflation and a drain on official foreign exchange reserves". The IMF suggested that "more significant policy changes are needed to stave off a disorderly adjustment". According to economist Steve Hanke, Venezuela's current economy, as of March 2014, had an inflation rate hovering above 300%, an official inflation rate around 60%, and a product scarcity index rising above 25% of goods. The Venezuelan government did not report inflation data for September and October 2014.

The growth in the BCV's money supply accelerated during the beginning of Maduro's presidency, which increased price inflation in the country. The money supply of the bolívar fuerte in Venezuela increased 64% in 2014, three times faster than any other economy observed by Bloomberg News at the time. Due to the rapidly decreasing value of the bolívar fuerte, Venezuelans jokingly called it "bolívar muerto" ("dead bolívar").

Maduro has blamed capitalist speculation for driving high inflation rates and creating widespread shortages of basic necessities. He has said he is fighting an "economic war", referring to newly enacted economic measures as "economic offensives" against political opponents, who, according to Maduro and his loyalists, are behind an international economic conspiracy. Maduro has been criticized for concentrating on public opinion instead of tending to practical issues that have been warned by economists, or creating solutions to improve Venezuela's economic prospects.

Devaluation of the ''bolívar''

After the Chávez administration established strict currency controls in 2003, there have been a series of five currency devaluations, disrupting the economy. On 8 January 2010, the government changed the official fixed exchange rate from 2.15 bolívares fuertes (Bs.F) to 2.60 bolívares (for imported healthcare goods and certain foods) and 4.30 bolívares (for imported cars, petrochemicals, and electronics). On 4 January 2011, the fixed exchange rate became 4.30 bolívares per US$1.00 for both sides of the economy. On 13 February 2013, the bolívar was devalued to 6.30 bolívares per USD in an attempt to counter budget deficits. The black (or parallel) market value of the ''bolívar fuerte'' and the ''bolívar soberano'' has been significantly lower than the fixed exchange rate and other rates set by the Venezuelan government (SICAD, SIMADI, DICOM). In November 2013, it was almost one-tenth that of the official fixed exchange rate of 6.3 bolívares per U.S. dollar. On 18 February 2016, President Maduro used his newly granted economic powers to devalue the official exchange rate of the bolívar fuerte from 6.3 Bs.F per USD to 10 Bs.F per USD. In September 2014, the unofficial exchange rate for the bolívar fuerte in Cúcuta, Colombia reached 100 Bs.F per USD. In May 2015, the bolívar fuerte lost 25% of its value in a week; the unofficial exchange rate was at 300 Bs.F per USD on 14 May and reached 400 Bs.F per USD on 21 May. In July 2015, the bolívar fuerte again dropped sharply, reaching 500 Bs.F per USD on 3 July and 600 Bs.F per USD on 9 July. By February 2016, the unofficial rate reached 1,000 Bs.F per USD. In November 2016, the bolívar fuerte saw its largest-ever monthly loss of value; the exchange rate reached 2,000 Bs.F per USD on 21 November 2016 and nearly 3,000 Bs.F per USD only days after. On 29 November 2016, the exchange rate surpassed 3,000 Bs.F per USD. In the month preceding 28 November 2016, the bolívar fuerte lost over 60% of its value. On 26 January 2018, the government retired the protected and subsidized 10 Bs.F per USD exchange rate that was highly overvalued following rampant inflation. On 5 February 2018, the BCV announced a devaluation, with the exchange rate going to 25,000 Bs.F per USD. This made the bolívar fuerte the second least-valued circulating currency in the world based on the official exchange rate, behind only the Iranian rial. Between September 2017 and August 2018, according to the informal exchange rate, the bolívar fuerte was the least-valued circulating currency in the world. The official exchange rate stood at 248,832 Bs.F per USD as of 10 August 2018, making it the least valued circulating currency in the world based on official exchange rates. In June 2018, the government authorized a new exchange rate for buying, but not selling currency. On 13 August 2018, the rate was 4,010,000 Bs.F per USD according to ZOOM Remesas.Minimum wage

The minimum wage in Venezuela dropped significantly in dollar terms during Maduro's presidency. It decreased from about 360 per month in 2012 to $31 per month in March 2015 based on the weakest legal exchange rate. On the Venezuelan currency black market, the minimum wage was only $20 per month. In April 2014, President Maduro raised the minimum wage by 30%, hoping to improve citizens' purchasing power. According to ''El Nuevo Herald'', most economists said that the measure would only help temporarily due to the official inflation rate being over 59%, and that the wage increase would only make things more difficult for companies, since they already faced a shortage of currency. In January 2015, the government announced that the minimum wage would be raised by 15%. On 1 May 2015, President Maduro announced that the minimum wage would increase by 30%, including 20% in May and 10% in July. The newly announced minimum wage was about $30 per month at the black market rate. In August 2018, following the release of a new currency, the minimum wage was raised from 392,646 Bs.F to 180 million Bs.F (equivalent to 1,800 bolívares soberanos, or Bs.S) per month. Sales tax was increased from 12% to 16%. The new wage was estimated to be around $30 per month at the black market rate. It became effective on 1 September 2018. The minimum wage was further increased to 4,500 Bs.S ($9.50) a month in November 2018 and then to 18,000 Bs.S ($6.52) a month in January 2019, a 300% increase. By early April 2019, the 18,000 Bs.S monthly minimum wage was the equivalent of $5.50 – less than the price of a McDonald's Happy Meal. Ecoanalitica estimated that prices jumped by 465% in the first two and a half months of 2019. In March 2019, ''The Wall Street Journal'' stated that the "main cause of hyperinflation is the central bank printing money to fund gaping public spending deficits", reporting that a teacher could only buy a dozen eggs and two pounds of cheese with a month's wages. On 27 April 2019, President Nicolás Maduro increased the minimum wage from 18,000 Bs.S ($3.46) to 40,000 Bs.S ($7.69), according to a presidential decree. In addition, President Maduro also announced the resumption of food vouchers worth 25,000 Bs.S ($4.80). The new wages became effective on 1 May 2019. According to a local NGO, the new minimum wage covers only one tenth of the cost of basic food products. The wage only allows Venezuelans to buy about four kilograms of beef or two McDonald's Happy Meals per month. By mid-August 2019, further inflation of the bolívar soberano had decreased the minimum wage by 65% from $8 a month to $2.80 a month and it had decreased further to $2 a month by late August.Government spending

In 2014, ''El Nuevo Herald'' reported that due a lack of money, SEBIN had decreased its work of monitoring of "potential external threats" and asked for Dirección de Inteligencia, Cuban intelligence agents to return to Venezuela.Bolivarian propaganda

According to ''El Nacional (Caracas), El Nacional'' newspaper, funding for Bolivarian propaganda, "official propaganda" increased. 65% of the funds of the Venezuelan Ministry of Popular Power for Communication and Information (MINCI) were used for propaganda in 2014. A total of over 500 million bolívares were allocated as funds to MINCI. In the 2015 Venezuelan government budget, the government designated 1.8 billion Bs.F for the promotion of the supposed achievements of the Maduro administration, which was more than the 1.3 billion Bs.F designated by the Ministry of Popular Power for Interior, Justice and Peace for public safety of the most populous Venezuelan municipality, Libertador Bolivarian Municipality, Libertador Bolívarian Municipality. Funding for domestic propaganda increased 139.3% in the 2015 budget; 73.7% of the MINCI's budget was used for official propaganda.Inflation rate

BCV estimates

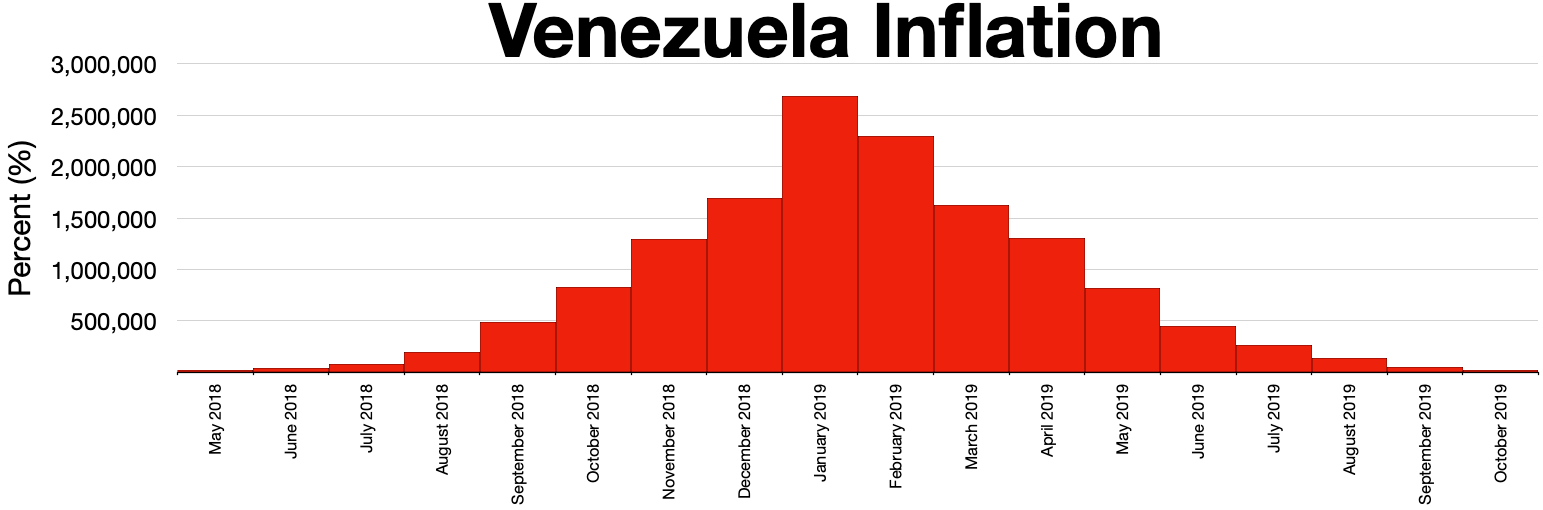

Under President Maduro, the inflation rate has been increasing at the highest levels, with the Central Bank of Venezuela, BCV estimating that inflation was at 56% in 2013, 69% in 2014 (highest in the world), and 181% in 2015 (highest in the world and the country's history). In 2016, Venezuela entered hyperinflation. The inflation rate reached 274% in 2016, 863% in 2017, 130,060% in 2018 and 9,586% in 2019. Since 2016, the overall inflation rate has increased to 53,798,500%. (*) Data was unpublished between 2016 and 2018, finally revealed in 2019.National Assembly estimates

Since 2017, the opposition-led National Assembly (Venezuela), National Assembly has been estimating the inflation rate after the BCV stopped publishing inflation rates between 2015 and 2019. In May 2019, Venezuela's annual inflation rate dropped below 1,000,000% for the first time since 2018, with the BCV restricting the domestic money supply.

(*) Formula applied to the Month Accumulated: Current Month Accumulated =

Since 2017, the opposition-led National Assembly (Venezuela), National Assembly has been estimating the inflation rate after the BCV stopped publishing inflation rates between 2015 and 2019. In May 2019, Venezuela's annual inflation rate dropped below 1,000,000% for the first time since 2018, with the BCV restricting the domestic money supply.

(*) Formula applied to the Month Accumulated: Current Month Accumulated =

IMF estimates

In its World Economic Outlook report, the IMF has provided inflation rate estimates between 1998 and 2019. In 2018, the annual inflation rate reached 929,790% and was expected to reach 10,000,000% by the end of 2019. According to the October 2019 World Economic Outlook report, Venezuela's inflation rate of 500,000 is the highest in the world. In comparison, in Latin America,''Café Con Leche'' and Misery Indexes

Bloomberg L.P., Bloomberg's ''Café Con Leche'' Index calculated the price of a cup of coffee to have increased 718% in the 12 weeks before 18 January 2018, an annualized inflation rate of 448,000%. Venezuela's Misery index (economics), misery rate was forecasted to reach 8,000,000% in 2019, making it the world's most miserable economy. The country has topped Bloomberg's Misery index (economics), Misery Index for the fifth consecutive year since 2013.Exchange rate history

Under Venezuelan law, it is illegal to publish the "Exchange rate#Parallel exchange rate, parallel exchange rate" in Venezuela. One popular website that has been publishing parallel exchange rates since 2010 is DolarToday, which has also been critical of the Maduro government. These tables and graphs show the exchange rate history of both the ''bolívar fuerte'' and the ''bolívar soberano'' compared to the United States dollar (USD) between 2012 and 2021.Effects

Unemployment

Unemployment has been increasing in the years of hyperinflation with the 2019 rate seen as Venezuela's highest since the end of the Bosnian War in 1995 and the biggest contraction since 2014 start of Libyan Civil War, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). In January 2016, the unemployment rate was 18.1% and the economy was the worst in the world according to the Misery index (economics), misery index. Venezuela has not reported official unemployment figures since April 2016, when the rate was at 7.3%. In October 2019, the unemployment rate reached 35%. By the end of the year, it was estimated that it would increase to 39% to 40%, and that 60% of the economically active population belong to the informal sector, which influences the low salary that has caused many young people to emigrate to other countries.Refugee and migration crisis

Emigration in Venezuela has always existed in a moderate way under Maduro's predecessor Hugo Chávez. It is from 2015 when the departure from the country of almost 30% of the population increases due to inflation in its economy, and that it increased when the country entered hyperinflation. The Organization of American States (OAS) and United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, UNHCR has been classified as one of the largest emigrations in the history of the Western Hemisphere, Western hemisphere. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, UNHCR, the deterioration of the political, economic and human rights situation in Venezuela continues, making international support necessary. The latest report discloses that 4.8 million Venezuelans are registered between refugees and migrants.Solutions and adaptations

Change of inflation rate calculations

In September 2014, the BCV reportedly changed its inflation rate calculation methods from the more common Laspeyres price index to the Price index#Fisher index and Marshall.E2.80.93Edgeworth index, Fisher price index. This changed the government's June inflation data from 5.7% to 4.4%, July's 5.5% rate to 4.1%, and August's 4.3% to 3.9%.< It was also stated in the BCV's August report that it was an "economic war that hindered the normal course of production activities and distribution of essential goods demanded by the Venezuelan people".Bolívar fuerte

On 7 March 2007, the Chávez administration announced that the bolívar would be revalued at a ratio of 1,000 to 1 on 1 January 2008, and renamed it the ''bolívar fuerte'' in an effort to facilitate the ease of transaction and accounting, responding to double-digit inflation. The new name is literally translated as "strong bolívar". It is also a reference to the ''peso fuerte'', an old coin worth 10 Spanish reales. The official exchange rate is restricted to individuals by CADIVI, which imposes an annual limit on the amount available for travel.Introduction of higher denomination banknotes

Denominations of 2 and 5 Bs.F banknotes were no longer found in circulation due to the inflation in 2015, but remained legal tender. By early December 2016, the 100 Bs.F note—Venezuela's largest denomination of currency—was only worth about US$0.23 on the black market. On 7 December 2016, a new series of notes (recolors of previous notes) in denominations of 500, 1,000, 2,000, 5,000, 10,000, and 20,000 Bs.F were unveiled to the public. On 3 November 2017, President Maduro unveiled a 100,000 Bs.F note, which was similar to the 2007-series 100 Bs.F note and the 2016-series 20,000 Bs.F note, but with the denomination spelled out in full instead of adding an additional three zeros after 100. This denomination was worth US$2.42 through black market exchange rates at the time of its release. By July 2018, increasing hyperinflation had reduced its value by 99.9% to less than US$0.01. On March 6, 2021, the government issued three new bills, worth Bs.F 200,000, 500,000, and 1,000,000. The last is worth US$0.52.Withdrawal of the 100 Bs.F banknote

On 11 December 2016, President Maduro, who had been ruling by decree, wrote into law that 100 Bs.F notes would be pulled from circulation within 72 hours due to "mafias" allegedly storing them to drive inflation. With more than 6 billion 100 Bs.F notes issued consisting of 46% of Venezuela's issued currency, Maduro allowed for Venezuelans to exchange all 100 Bs.F notes for 100 Bs.F coins or higher denomination banknotes while also blocking international travel to prevent the return of notes that were supposedly stockpiled. The government justified the move by claiming that the US was working with crime syndicates to move Venezuelan banknotes to warehouses in Europe to cause the fall of the government, and that the government was thwarting this threat by withdrawing the notes from circulation. The government of India has done a similar action in November 2016, by 2016 Indian banknote demonetisation, withdrawing the 500 and 1000 rupee notes from circulation that would curtail the shadow economy and reduce the use of illicit and counterfeit cash to fund illegal activity and terrorism. On 14 February 2017, Paraguayan authorities uncovered a stash of 50 and 100 Bs.F banknotes totaling 1.5 billion Bs.F on Brazil–Paraguay border, its Brazilian border that had not yet been circulated. According to a US Department of Defense adviser linked to The Pentagon, the 1.5 billion Bs.F was printed by Venezuela and destined for Bolivia, since unlike the implied exchange rate of thousands of Bs.F per USD, the exchange rate was approximately 10 Bs.F per USD, making the value of the stash 419 times stronger, from US$358,000 to US$150 million. The adviser further stated that the Venezuelan government tried to send the newly printed notes to be exchanged by the Bolivian government, so Bolivia could pay 20% of its debt to Venezuela, and so Venezuela could use the United States dollar, US dollars for its own disposal.Petro cryptocurrency

In December 2017, President Maduro announced that Venezuela would introduce a state cryptocurrency called the 'Petro' in an attempt to shore up its struggling economy. This new cryptocurrency would be backed by Venezuela's reserves of petroleum, oil, gasoline, gold, and diamonds. Maduro stated that the Petro would allow Venezuela to "advance in issues of monetary sovereignty", and that it would make "new forms of international financing" available to the country. Democratic Unity Roundtable, Opposition leaders, however, expressed doubt due to Economy of Venezuela#2013–present, Venezuela's economic turmoil, pointing to the falling value of the Venezuelan bolívar, its fiat currency, and $140 billion in Foreign Debt, foreign debt.

In January 2018, as a response to the petro, Venezuela's National Assembly (Venezuela), National Assembly, headed by the opposition Democratic Unity Roundtable, declared the petro to be an illegal debt issuance by a government desperate for cash, and said it would not recognize it. On the same month, Maduro announced that Venezuela would issue 100 million Tokenization (data security), tokens of the petro, which would put the value of the entire issuance at just over $6 billion. It also established a cryptocurrency government advisory group called VIBE to act as "an institutional, political and legal base" from which to launch the petro.

In March 2018, US President Donald Trump signed an executive order prohibiting transactions in any Venezuelan government-issued cryptocurrency by any US citizen or any person within the US, effective on 19 March, after claiming that the cryptocurrency was designed to obfuscate US sanctions and access international financing.

In August 2018, the bolívar soberano had a fixed exchange rate of 3,600 Bs.S per Petro. The Petro was supposedly tied to the price of a barrel of oil (about US$60 in August 2018). As of late-August 2018, there is no evidence that the Petro is being traded. The Petro is regarded by many as a Confidence trick, scam.

In December 2017, President Maduro announced that Venezuela would introduce a state cryptocurrency called the 'Petro' in an attempt to shore up its struggling economy. This new cryptocurrency would be backed by Venezuela's reserves of petroleum, oil, gasoline, gold, and diamonds. Maduro stated that the Petro would allow Venezuela to "advance in issues of monetary sovereignty", and that it would make "new forms of international financing" available to the country. Democratic Unity Roundtable, Opposition leaders, however, expressed doubt due to Economy of Venezuela#2013–present, Venezuela's economic turmoil, pointing to the falling value of the Venezuelan bolívar, its fiat currency, and $140 billion in Foreign Debt, foreign debt.

In January 2018, as a response to the petro, Venezuela's National Assembly (Venezuela), National Assembly, headed by the opposition Democratic Unity Roundtable, declared the petro to be an illegal debt issuance by a government desperate for cash, and said it would not recognize it. On the same month, Maduro announced that Venezuela would issue 100 million Tokenization (data security), tokens of the petro, which would put the value of the entire issuance at just over $6 billion. It also established a cryptocurrency government advisory group called VIBE to act as "an institutional, political and legal base" from which to launch the petro.

In March 2018, US President Donald Trump signed an executive order prohibiting transactions in any Venezuelan government-issued cryptocurrency by any US citizen or any person within the US, effective on 19 March, after claiming that the cryptocurrency was designed to obfuscate US sanctions and access international financing.

In August 2018, the bolívar soberano had a fixed exchange rate of 3,600 Bs.S per Petro. The Petro was supposedly tied to the price of a barrel of oil (about US$60 in August 2018). As of late-August 2018, there is no evidence that the Petro is being traded. The Petro is regarded by many as a Confidence trick, scam.

Redenomination

Bolívar soberano

On 22 March 2018, President Maduro announced a new monetary reform, in which the bolívar would once again be revalued at a ratio of 1 to 1,000, making the new bolívar equal to one million pre-2008 bolívares. The currency was renamed as the ''bolívar soberano'' ("sovereign bolívar"). New coins in denominations of 50 céntimos and 1 Bs.S, as well as new banknotes in denominations of 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, and 500 Bs.S, were introduced. The change was to be made effective on 4 June 2018. Starting on 1 May 2018, prices were expressed in both bolívares and bolívares soberanos at the original rate of 1,000 to 1. (For example, one kilogram of pasta was shown with prices of 695,000 Bs.F and 695 Bs.S) Prices expressed in the new currency were rounded to the nearest 50 céntimos, as this was expected to be the lowest denomination in circulation at launch. The rounding created difficulties because some items and sales quantities were priced significantly less than 0.50 Bs.S; for example, of gasoline and a Caracas Metro ticket typically cost 0.06 Bs.S and 0.04 Bs.S, respectively. The launch of the bolívar soberano was originally scheduled for 4 June 2018. Maduro delayed the launch date, quoting Aristides Maza: "the period established to carry out the conversion is not enough". The revaluation was rescheduled to 20 August 2018, and the rate changed to 100,000 to 1, with prices being required to be expressed at the new rate starting 1 August 2018. On 20 August 2018, the Maduro administration launched the bolívar soberano, with 1 Bs.S worth 100,000 Bs.F. New coins in denominations of 50 céntimos and 1 Bs.S, as well as new banknotes in denominations of 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, and 500 Bs.S, were introduced. Under the country's official fixed exchange rate to the US dollar, the new currency was devalued by roughly 95% compared to the old bolívar fuerte. The day was declared a bank holiday to allow banks to adjust to the new currency. Initially, the bolívar soberano was to be run alongside the bolívar fuerte during a transition period. However, from the start of the transition (20 August), bolívar fuerte notes of 500 or less could not be used, only deposited at banks. Maduro also announced that after the currency redenomination on 20 August, old banknotes with a face value of 1,000 Bs.F or higher would circulate in parallel with bolívar soberano notes and would continue to be used for a limited time, and that banknotes with a face value below 1,000 Bs.F would be withdrawn from circulation and cease to be legal tender. Immediately following the introduction of the bolívar soberano, the inflation rate increased from 61,463% on 21 August to 65,320% on 22 August. By 24 August 2018, the introduction of the bolívar soberano had not prevented hyperinflation. According to economist Steve Hanke, between 18 August and 21 August 2018, the inflation rate increased from 48,760% to 65,320%. On 22 August, DolarToday estimated that the free-market exchange rate was 71.2 Bs.S per USD. AirTM's reported exchange rate was 75.6 Bs.S per USD. According to DolarToday, the estimated exchange rate was 2700 Bs.S per USD in Venezuela's free market . AirTM's exchange rate was 2200 Bs.S per USD.= Introduction of larger banknotes

= By June 2019, further inflation of the bolívar soberano since redenomination had resulted in 10,000, 20,000, and 50,000 Bs.S banknotes entering circulation effective on 13 June. The BCV stated that the introduction of the new banknotes will "make the payment system more efficient and facilitate commercial transactions." The highest denomination banknote (Bs.S 50,000) was worth US$8 on the black market and was more than the monthly minimum wage of Bs.S 40,000. On 14 June, the BCV estimated the official exchange rate to be 6,244 Bs.S per USD. DolarToday estimated the free market exchange rate to be 6,803 Bs.S per USD. By mid-August 2019, the exchange rate reached an all-time high of 13,921 Bs.S per USD, while the euro was at 15,515 Bs.S per EUR. According to Venezuelan economist Luis Oliveros, the exchange rate experienced "a 30,000% increase" compared to the rate one year ago, 37 Bs.S per USD. By the end of the month, the parallel exchange rate reached nearly 23,000 Bs.S per USD. However, the exchange rate appreciated to about 20,000 Bs.S per USD by 10 October 2019Informal dollarization

Following increased international sanctions throughout 2019, the Maduro government abandoned policies established by Chávez such as price and currency controls (imposed since 2003) which resulted in the country seeing a rebound from economic decline. According to a survey by economic consultant Econalítica, about 54% of transactions in Venezuelan during September 2019 were in United States dollar, US dollars. The number of transactions in dollars raised up to 86% in Maracaibo. The survey also found that almost all sales of electrical appliances are dollarized, as well as half of the sales of clothes, spare car parts and food. In a November 2019 interview with Venezuelan journalist José Vicente Rangel, President Nicolás Maduro described dollarization as an "escape valve" that helps the recovery of the country, the spread of productive forces in the country and the economy. However, Maduro said that the Venezuelan bolívar will still remain as the national currency. Some Venezuelan banks began to issue debit cards in U.S. dollars on January 29, 2021 in Venezuela, 2021.See also

* Hyperinflation in Brazil * Hyperinflation in Zimbabwe * International sanctions during the Venezuelan crisis * Venezuelan bolívar * Viernes Rojo * Viernes NegroReferences

{{South America in topic, Hyperinflation in, countries_only=yes Inflation by country Crisis in Venezuela 2010s in Venezuela 2020s in Venezuela 2010s economic history 2020s economic history Man-made disasters in Venezuela Economic crises Economic history of Venezuela