Hylaeosaurus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Hylaeosaurus'' ( ;

The first ''Hylaeosaurus''

The first ''Hylaeosaurus''  On 30 November Mantell sent the piece to the

On 30 November Mantell sent the piece to the  ''Hylaeosaurus'' is the most obscure of the three animals used by Sir Richard Owen to first define the new group

''Hylaeosaurus'' is the most obscure of the three animals used by Sir Richard Owen to first define the new group  Additional remains have been referred to ''Hylaeosaurus'', from the

Additional remains have been referred to ''Hylaeosaurus'', from the

''Hylaeosaurus armatus'' Mantell 1833 is currently considered the only valid

''Hylaeosaurus armatus'' Mantell 1833 is currently considered the only valid

Gideon Mantell originally estimated that ''Hylaeosaurus'' was about long, or about half the size of the other two original dinosaurs, '' Iguanodon'' and '' Megalosaurus''. At the time, he modelled the animal after a modern lizard. Modern estimates range up to in length. Gregory S. Paul in 2010 estimated the length at , the weight at . Some estimates are considerably lower: in 2001 Darren Naish e.a. gave a length of .Naish, D. and Martill, D.M., 2001, "Armoured Dinosaurs: Thyreophorans". In: Martill, D.M., Naish, D., (editors). ''Dinosaurs of the Isle of Wight''. Palaeontological Association Field Guides to Fossils 10. pp. 147–184

Many details about the build of ''Hylaeosaurus'' are unknown, especially if the material is strictly limited to the holotype. Maidment gave two

Gideon Mantell originally estimated that ''Hylaeosaurus'' was about long, or about half the size of the other two original dinosaurs, '' Iguanodon'' and '' Megalosaurus''. At the time, he modelled the animal after a modern lizard. Modern estimates range up to in length. Gregory S. Paul in 2010 estimated the length at , the weight at . Some estimates are considerably lower: in 2001 Darren Naish e.a. gave a length of .Naish, D. and Martill, D.M., 2001, "Armoured Dinosaurs: Thyreophorans". In: Martill, D.M., Naish, D., (editors). ''Dinosaurs of the Isle of Wight''. Palaeontological Association Field Guides to Fossils 10. pp. 147–184

Many details about the build of ''Hylaeosaurus'' are unknown, especially if the material is strictly limited to the holotype. Maidment gave two

''Hylaeosaurus'' was the first

''Hylaeosaurus'' was the first

Paper Dinosaurs, 1824–1969, from Linda Hall Library.illustration

{{Taxonbar, from=Q131770 Nodosaurids Valanginian life Early Cretaceous dinosaurs of Europe Cretaceous England Fossils of England Fossil taxa described in 1833 Taxa named by Gideon Mantell Ornithischian genera

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

: / "belonging to the forest" and / "lizard") is a herbivorous ankylosaurian dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

that lived about 136 million years ago

The abbreviation Myr, "million years", is a unit of a quantity of (i.e. ) years, or 31.556926 teraseconds.

Usage

Myr (million years) is in common use in fields such as Earth science and cosmology. Myr is also used with Mya (million years ago ...

, in the late Valanginian

In the geologic timescale, the Valanginian is an age or stage of the Early or Lower Cretaceous. It spans between 139.8 ± 3.0 Ma and 132.9 ± 2.0 Ma (million years ago). The Valanginian Stage succeeds the Berriasian Stage of the Lower Cretace ...

stage of the early Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

period of England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

. It was found in the Grinstead Clay Formation

Grinstead is an English surname, and a place name. It may refer to:

People

*Baron Grinstead, a title in the peerage of Ireland (see Earl of Enniskillen)

* Burt Grinstead (born 1988), U.S. actor

* Charles Walder Grinstead (1860–1930), English ten ...

.

''Hylaeosaurus'' was one of the first dinosaurs to be discovered, in 1832 by Gideon Mantell. In 1842 it was one of the three dinosaurs Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Ow ...

based the Dinosauria on, the others being '' Iguanodon'' and '' Megalosaurus''. Four species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriat ...

were named in the genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

, but only the type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specim ...

''Hylaeosaurus armatus'' is today considered valid. Only limited remains have been found of ''Hylaeosaurus'' and much of its anatomy is unknown. It might have been a basal nodosaurid, although a recent cladistic analysis recovers it as a basal ankylosaurid.

''Hylaeosaurus'' was about five metres long. It was an armoured dinosaur that carried at least three long spines on its shoulder.

History of discovery

The first ''Hylaeosaurus''

The first ''Hylaeosaurus'' fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s were discovered in the Grinstead Clay Formation

Grinstead is an English surname, and a place name. It may refer to:

People

*Baron Grinstead, a title in the peerage of Ireland (see Earl of Enniskillen)

* Burt Grinstead (born 1988), U.S. actor

* Charles Walder Grinstead (1860–1930), English ten ...

, West Sussex

West Sussex is a county in South East England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the shire districts of Adur, Arun, Chichester, Horsham, and Mid Sussex, and the boroughs of Crawley and Worthing. Covering an ...

. On 20 July 1832, fossil collector Gideon Mantell wrote to Professor Benjamin Silliman that when a gunpowder explosion had demolished a quarry rock face in Tilgate Forest, several of the boulders freed showed the bones of a saurian. A local fossil dealer had assembled the about fifty pieces, described by him as a "great consarn of bites and boanes". Having doubts about the value of the fragments, Mantell had nevertheless purchased the pieces and soon discovered they could be united into a single skeleton, partially articulated. Mantell was delighted with the find because previous specimens of '' Megalosaurus'' and '' Iguanodon'' had consisted of single bone elements. The discovery in fact represented the most complete non-avian dinosaur skeleton known at the time. He was strongly inclined to describe the find as belonging to the latter genus, but during a visit by William Clift, the curator of the Royal College of Surgeons of England

The Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCS England) is an independent professional body and registered charity that promotes and advances standards of surgical care for patients, and regulates surgery and dentistry in England and Wales. T ...

museum, and his assistant John Edward Gray

John Edward Gray, FRS (12 February 1800 – 7 March 1875) was a British zoologist. He was the elder brother of zoologist George Robert Gray and son of the pharmacologist and botanist Samuel Frederick Gray (1766–1828). The same is used f ...

, he began to doubt the identification. Clift was the first to point out that several plates and spikes were probably part of a body armour, attached to the back or sides of the rump.Dennis R. Dean, 1999, ''Gideon Mantell and the Discovery of Dinosaurs'', Cambridge University Press, 315 pp In November 1832 Mantell decided to create a new generic name: ''Hylaeosaurus''. It is derived from the Greek ὑλαῖος, ''hylaios'', "of the wood". Mantell originally claimed the name ''Hylaeosaurus'' meant "forest

A forest is an area of land dominated by trees. Hundreds of definitions of forest are used throughout the world, incorporating factors such as tree density, tree height, land use, legal standing, and ecological function. The United Nations' ...

lizard", after the Tilgate Forest in which it was discovered. Later, he claimed that it meant "Weald

The Weald () is an area of South East England between the parallel chalk escarpments of the North and the South Downs. It crosses the counties of Hampshire, Surrey, Sussex and Kent. It has three separate parts: the sandstone "High Weald" in the ...

en lizard" ("wealden" being another word for ''forest''), in reference to the Wealden Group

The Wealden Group, occasionally also referred to as the Wealden Supergroup, is a group (a sequence of rock strata) in the lithostratigraphy of southern England. The Wealden group consists of paralic to continental (freshwater) facies sedimenta ...

, the name for the early Cretaceous geological formation in which the dinosaur was first found.

On 30 November Mantell sent the piece to the

On 30 November Mantell sent the piece to the Geological Society of London

The Geological Society of London, known commonly as the Geological Society, is a learned society based in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest national geological society in the world and the largest in Europe with more than 12,000 Fellows.

Fe ...

. Shortly afterwards he himself went to London and on 5 December during a meeting of the Society, in which he for the first time personally met Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Ow ...

, reported on the find to large acclaim. However, he was also informed that a paper he had already prepared, was a third too long. On advice of his friend Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known as the author of ''Principles of Geolo ...

, Mantell decided instead of rewriting the paper, to publish an entire book on his fossil finds and dedicate a chapter to ''Hylaeosaurus''. Within three weeks Mantell composed the volume from earlier notes. On 17 December Henry De la Beche

Sir Henry Thomas De la Beche KCB, FRS (10 February 179613 April 1855) was an English geologist and palaeontologist, the first director of the Geological Survey of Great Britain, who helped pioneer early geological survey methods. He was the ...

warned him that the changed conventions in nomenclature implied that only he who provided a full species name was recognised as the author: to ''Hylaeosaurus'' a specific name needed to be added. Mantell on 19 December chose ''armatus'', Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

for "armed" or "armoured", in reference to the spikes and armour plates. As Mantell himself put it: "there appears every reason to conclude that either its back was armed with a formidable row of spines, constituting a dermal fringe, or that its tail possessed the same appendage". In May 1833 his ''The Geology of the South-East of England'' appeared, hereby validly naming the type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specim ...

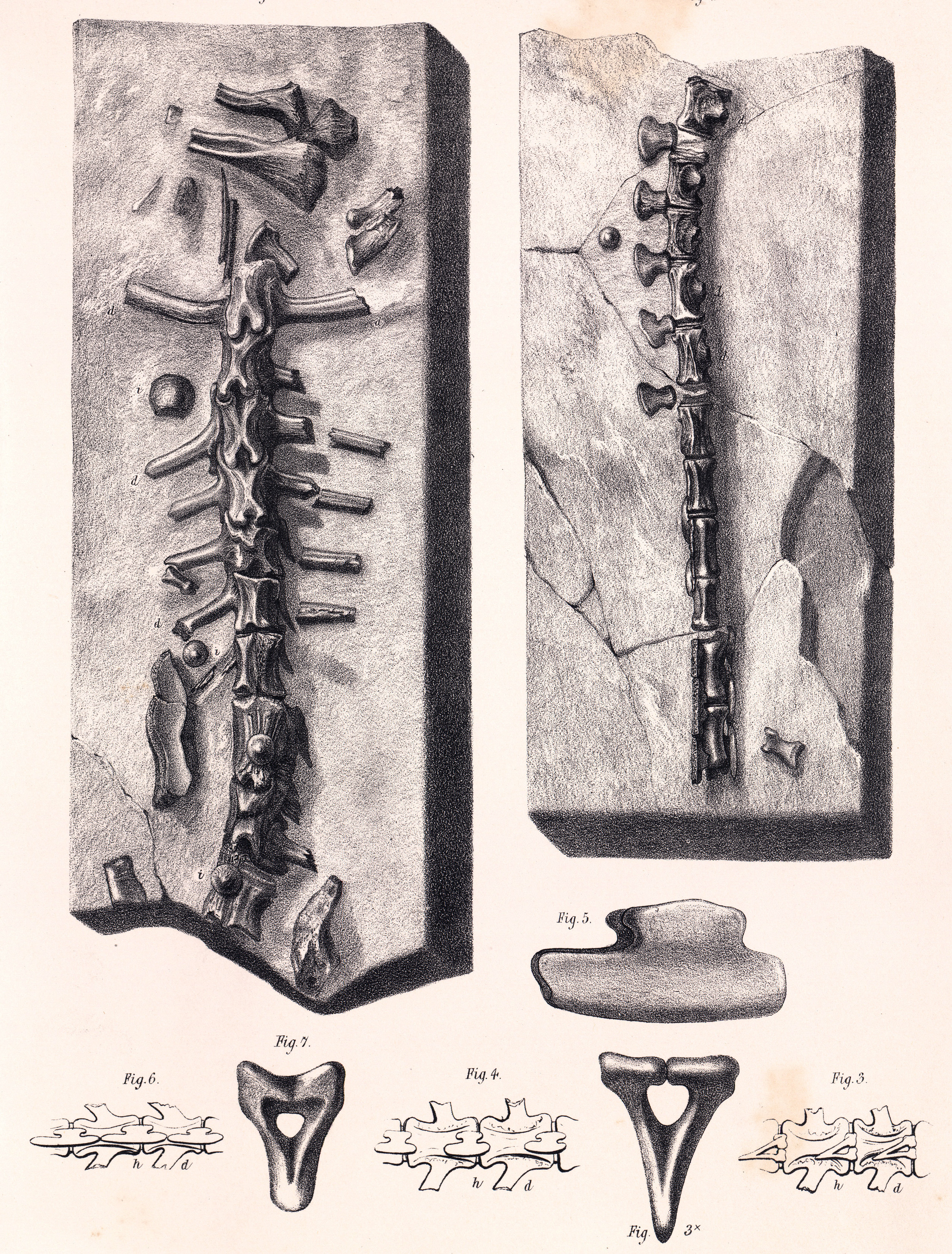

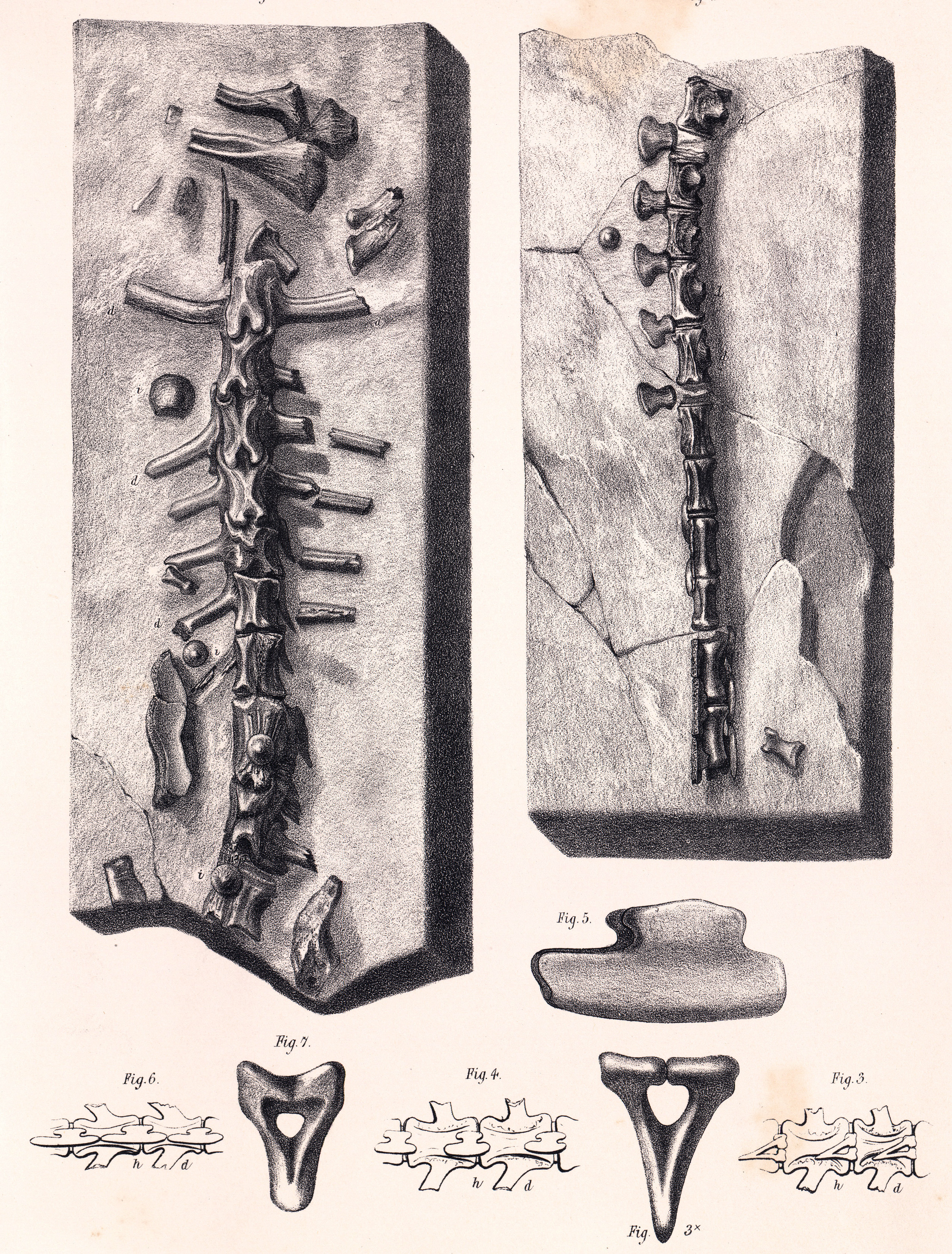

''Hylaeosaurus armatus''. Mantell published a lithograph

Lithography () is a planographic method of printing originally based on the immiscibility of oil and water. The printing is from a stone (lithographic limestone) or a metal plate with a smooth surface. It was invented in 1796 by the German a ...

of his find in ''The Geology of the South-East of England''; and another drawing in the fourth edition of ''The Wonders of Geology'', in 1840.

''Hylaeosaurus'' is the most obscure of the three animals used by Sir Richard Owen to first define the new group

''Hylaeosaurus'' is the most obscure of the three animals used by Sir Richard Owen to first define the new group Dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

ia, in 1842, the other genera being ''Megalosaurus'' and ''Iguanodon''. Not only has ''Hylaeosaurus'' received less public attention, despite being included in the life-sized models by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins placed in the Crystal Palace

Crystal Palace may refer to:

Places Canada

* Crystal Palace Complex (Dieppe), a former amusement park now a shopping complex in Dieppe, New Brunswick

* Crystal Palace Barracks, London, Ontario

* Crystal Palace (Montreal), an exhibition building ...

Park, it also never functioned as a "wastebasket taxon". Owen in 1840 developed a new hypothesis about the spikes; noting they were asymmetrical he correctly rejected the notion they formed a row on the back but incorrectly assumed they were gastralia

Gastralia (singular gastralium) are dermal bones found in the ventral body wall of modern crocodilians and tuatara, and many prehistoric tetrapods. They are found between the sternum and pelvis, and do not articulate with the vertebrae. In thes ...

or belly-ribs.

The original specimen, recovered by Gideon Mantell from the Tilgate

Tilgate is one of 14 neighbourhoods within the town of Crawley in West Sussex, England. The area contains a mixture of privately developed housing, self-build groups and ex-council housing. It is bordered by the districts of Furnace Green to th ...

Forest, was in 1838 acquired by the Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleontology, climatology, and more. ...

of London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

. It has the inventory number NHMUK 3775 (earlier BMNH R3775). It was found in a layer of the Tunbridge Wells Sand Formation

The Tunbridge Wells Sand Formation is a geological unit which forms part of the Wealden Group and the uppermost and youngest part of the unofficial Hastings Beds. These geological units make up the core of the geology of the Weald in the English c ...

dating from the Valanginian

In the geologic timescale, the Valanginian is an age or stage of the Early or Lower Cretaceous. It spans between 139.8 ± 3.0 Ma and 132.9 ± 2.0 Ma (million years ago). The Valanginian Stage succeeds the Berriasian Stage of the Lower Cretace ...

, about 137 million years old. This holotype

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of seve ...

is the best specimen and is composed of the front end of a skeleton minus most of the head and the forelimbs, though only the parts on the face of the stone block are easily studied. The block measures about 135 by 75 centimetres. The holotype consists of the rear of the skull and perhaps lower jaws, ten vertebrae, both scapulae, both coracoids and several spikes and armour plates. The skeleton is viewed from below. For a long time no further preparation had taken place, beyond the assembly and chiselling out by Mantell himself, but in the early twenty-first century the museum began to further free the bones by both chemical and mechanical means. This has proven difficult because the acids used tended to dissolve the glue and gypsum with which the fossils had been repaired, causing the blocks to fall apart. The limited information gained by the preparations by Mark Graham since 2003, was published in 2020, together with a revised description.

Several finds from the mainland of Britain have been referred to ''Hylaeosaurus armatus''. However, in 2011 Paul Barrett and Susannah Maidment concluded that only the holotype could with certainty be associated with the species, in view of the presence of '' Polacanthus'' in the same layers.Barrett, P.M. and Maidment, S.C.R., 2011, "Wealden armoured dinosaurs". In: Batten, D.J. (ed.). ''English Wealden fossils''. Palaeontological Association, London, Field Guides to Fossils 14, 769 pp

Additional remains have been referred to ''Hylaeosaurus'', from the

Additional remains have been referred to ''Hylaeosaurus'', from the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Is ...

, (the Ardennes

The Ardennes (french: Ardenne ; nl, Ardennen ; german: Ardennen; wa, Årdene ; lb, Ardennen ), also known as the Ardennes Forest or Forest of Ardennes, is a region of extensive forests, rough terrain, rolling hills and ridges primarily in Be ...

of) France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, Bückeberg Formation

The Bückeberg Formation is a geologic formation and LagerstätteHornung et al., in Reitner et al., 2013, p.75 in Germany. It preserves fossils dating back to the Berriasian of the Cretaceous period.Hornung et al., 2012 The Bückeberg Formation ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

and Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

. The remains from France may actually belong to '' Polacanthus'' and the other references are today also considered dubious. However, possible remains were reported from Germany in 2013: a spike, specimen DLM 537 and the lower end of a humerus, specimen GPMM A3D.3, which were referred to a ''Hylaeosaurus'' sp.

Later species

''Hylaeosaurus armatus'' Mantell 1833 is currently considered the only valid

''Hylaeosaurus armatus'' Mantell 1833 is currently considered the only valid species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriat ...

in the genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

. However, three others have been named. In 1844, Mantell named ''Hylaeosaurus oweni'' based on the same specimen as ''H. armatus'', wanting to honour Richard Owen. This has been sunk as a junior objective synonym of ''H. armatus''. In 1956 Alfred Romer renamed ''Regnosaurus

''Regnosaurus'' (meaning "Sussex lizard") is a genus of herbivorous stegosaurian dinosaur that lived during the Early Cretaceous Period in what is now England. It was one of the first stegosaurs disvovered.

Discovery and species

The fossil r ...

'' into ''Hylaeosaurus northhamptoni''. '' Polacanthus'' Owen 1865 was by Walter Coombs

Walter may refer to:

People

* Walter (name), both a surname and a given name

* Little Walter, American blues harmonica player Marion Walter Jacobs (1930–1968)

* Gunther (wrestler), Austrian professional wrestler and trainer Walter Hahn (born 19 ...

in 1971 renamed into ''Hylaeosaurus foxii''. These last two names have found no acceptance; ''H. foxii'' remained an invalid ''nomen ex dissertatione''. It has also been suggested that '' Polacanthus'' is simply the same species as ''Hylaeosaurus armatus'' and thus a junior synonym, but there are a number of differences in their osteology

Osteology () is the scientific study of bones, practised by osteologists. A subdiscipline of anatomy, anthropology, and paleontology, osteology is the detailed study of the structure of bones, skeletal elements, teeth, microbone morphology, func ...

.

Sometimes bones from the ''Hylaeosaurus'' material have later been made separate species. In 1928 Franz Nopcsa Franz may refer to:

People

* Franz (given name)

* Franz (surname)

Places

* Franz (crater), a lunar crater

* Franz, Ontario, a railway junction and unorganized town in Canada

* Franz Lake, in the state of Washington, United States – see Fran ...

made specimen BMNH 2584, a left scapula referred by Mantell to ''H. armatus'', part of the type material of ''Polacanthoides ponderosus''. Though in 1978 synonymised with ''Hylaeosaurus'', ''Polacanthoides'' is today considered a ''nomen dubium

In binomial nomenclature, a ''nomen dubium'' (Latin for "doubtful name", plural ''nomina dubia'') is a scientific name that is of unknown or doubtful application.

Zoology

In case of a ''nomen dubium'' it may be impossible to determine whether a s ...

'', an indeterminate member of the Thyreophora.

Description

Gideon Mantell originally estimated that ''Hylaeosaurus'' was about long, or about half the size of the other two original dinosaurs, '' Iguanodon'' and '' Megalosaurus''. At the time, he modelled the animal after a modern lizard. Modern estimates range up to in length. Gregory S. Paul in 2010 estimated the length at , the weight at . Some estimates are considerably lower: in 2001 Darren Naish e.a. gave a length of .Naish, D. and Martill, D.M., 2001, "Armoured Dinosaurs: Thyreophorans". In: Martill, D.M., Naish, D., (editors). ''Dinosaurs of the Isle of Wight''. Palaeontological Association Field Guides to Fossils 10. pp. 147–184

Many details about the build of ''Hylaeosaurus'' are unknown, especially if the material is strictly limited to the holotype. Maidment gave two

Gideon Mantell originally estimated that ''Hylaeosaurus'' was about long, or about half the size of the other two original dinosaurs, '' Iguanodon'' and '' Megalosaurus''. At the time, he modelled the animal after a modern lizard. Modern estimates range up to in length. Gregory S. Paul in 2010 estimated the length at , the weight at . Some estimates are considerably lower: in 2001 Darren Naish e.a. gave a length of .Naish, D. and Martill, D.M., 2001, "Armoured Dinosaurs: Thyreophorans". In: Martill, D.M., Naish, D., (editors). ''Dinosaurs of the Isle of Wight''. Palaeontological Association Field Guides to Fossils 10. pp. 147–184

Many details about the build of ''Hylaeosaurus'' are unknown, especially if the material is strictly limited to the holotype. Maidment gave two autapomorphies

In phylogenetics, an autapomorphy is a distinctive feature, known as a derived trait, that is unique to a given taxon. That is, it is found only in one taxon, but not found in any others or outgroup taxa, not even those most closely related to t ...

, unique derived traits: the scapula did not fuse with the coracoid, even when the animal was of a considerable size; there were three long spines on its shoulder. Even these traits are not very distinctive: Mantell and Owen had attributed the lack of fusion to ontogeny

Ontogeny (also ontogenesis) is the origination and development of an organism (both physical and psychological, e.g., moral development), usually from the time of fertilization of the egg to adult. The term can also be used to refer to the s ...

and the total number of spines cannot be observed. ''Hylaeosaurus'' is often styled as a fairly typical nodosaur, with rows of armour plating on the back and tail combined with a relatively long head, equipped with a beak

The beak, bill, or rostrum is an external anatomical structure found mostly in birds, but also in turtles, non-avian dinosaurs and a few mammals. A beak is used for eating, preening, manipulating objects, killing prey, fighting, probing for fo ...

used to crop low-lying vegetation.

In 2001 the skull and lower jaws remains were described by Kenneth Carpenter. The damaged and shifted skull elements provided little information. The quadrate is laterally bowed. The quadratojugal has a high attachment point on the shaft of the quadrate. A triangular postorbital

The ''postorbital'' is one of the bones in vertebrate skulls which forms a portion of the dermal skull roof and, sometimes, a ring about the orbit. Generally, it is located behind the postfrontal and posteriorly to the orbital fenestra. In some ...

horn was present. In 2020, it was concluded that the presumed quadrate was in fact the jugal.

Several distinguishing traits were established in 2020. On the shoulder blade, there is a sharp angle of 120° between the acromion and the proximal plate. The acromial process is shelf-shaped instead of thumb-like or folded, from a point positioned at a third from the top edge projecting obliquely to below and sideways instead of strictly laterally. The top edge of the proximal plate is curved sideways. The sides of the centra of the neck vertebrae show a horizontal ridge. Apart from these autapomorphies, the undersides of the side processes of the back vertebrae are exceptionally concave.

The spines at the shoulder are curved to the rear, long, flattened, narrow and pointed. Their underside shows a shallow trough. The front spine is the longest at 42.5 centimetres; to the rear the spines become gradually shorter and wider. A fourth spine, of about the same build but more forward-pointing, is present immediately behind the skull. In 2013 Sven Sachs

Sven (in Danish and Norwegian, also Svend and also in Norwegian most commonly Svein) is a Scandinavian first name which is also used in the Low Countries and German-speaking countries. The name itself is Old Norse for "young man" or "young ...

and Jahn Hornung suggested a configuration in which there were five lateral neck spines, the new German spine having a morphology adapted to fit in the third position.

Phylogeny

''Hylaeosaurus'' was the first

''Hylaeosaurus'' was the first ankylosaur

Ankylosauria is a group of herbivorous dinosaurs of the order Ornithischia. It includes the great majority of dinosaurs with armor in the form of bony osteoderms, similar to turtles. Ankylosaurs were bulky quadrupeds, with short, powerful limbs. ...

discovered. Until well into the twentieth century its exact affinities would remain uncertain. In 1978 Coombs assigned it to the Nodosauridae

Nodosauridae is a family of ankylosaurian dinosaurs, from the Late Jurassic to the Late Cretaceous period in what is now North America, South America, Europe, and Asia.

Description

Nodosaurids, like their close relatives the ankylosaurids ...

within the Ankylosauria. This is still a usual classification, ''Hylaeosaurus'' being recovered as a basal nodosaurid in most exact cladistic

Cladistics (; ) is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups ("clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is typically shared derived char ...

analyses, sometimes more precisely as a member of the Polacanthinae, and thus being related to '' Gastonia'' and ''Polacanthus''. However, in the 1990s, the polacanthines were sometimes seen as basal ankylosaurids, because they were mistakenly believed to have small tail-clubs. A more popular alternative today is that they formed a Polacanthidae, a basal group outside of the nodosaurids + ankylosaurids clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English ter ...

.

A 2012 study finding ''Hylaeosaurus'' to be a basal nodosaurid but not a polacanthine is shown in this cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an evolutionary tree because it does not show how ancestors are related to ...

:

See also

* Timeline of ankylosaur researchReferences

External links

Paper Dinosaurs, 1824–1969, from Linda Hall Library.

{{Taxonbar, from=Q131770 Nodosaurids Valanginian life Early Cretaceous dinosaurs of Europe Cretaceous England Fossils of England Fossil taxa described in 1833 Taxa named by Gideon Mantell Ornithischian genera