Hydrolyze on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Hydrolysis (; ) is any chemical reaction in which a molecule of water breaks one or more chemical bonds. The term is used broadly for

Hydrolysis (; ) is any chemical reaction in which a molecule of water breaks one or more chemical bonds. The term is used broadly for

Upon hydrolysis, an

Upon hydrolysis, an

ATP + H2O -> ADP + P_

Secondly, the removal of a terminal diphosphate to yield

M(H2O)_\mathit^ + H2O <=> M(H2O)_(OH)^ + H3O+

Thus the aqua

Hydrolysis (; ) is any chemical reaction in which a molecule of water breaks one or more chemical bonds. The term is used broadly for

Hydrolysis (; ) is any chemical reaction in which a molecule of water breaks one or more chemical bonds. The term is used broadly for substitution

Substitution may refer to:

Arts and media

*Chord substitution, in music, swapping one chord for a related one within a chord progression

*Substitution (poetry), a variation in poetic scansion

* "Substitution" (song), a 2009 song by Silversun Pic ...

, elimination, and solvation

Solvation (or dissolution) describes the interaction of a solvent with dissolved molecules. Both ionized and uncharged molecules interact strongly with a solvent, and the strength and nature of this interaction influence many properties of t ...

reactions in which water is the nucleophile

In chemistry, a nucleophile is a chemical species that forms bonds by donating an electron pair. All molecules and ions with a free pair of electrons or at least one pi bond can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they ar ...

.

Biological hydrolysis is the cleavage of biomolecules where a water molecule is consumed to effect the separation of a larger molecule into component parts. When a carbohydrate

In organic chemistry, a carbohydrate () is a biomolecule consisting of carbon (C), hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) atoms, usually with a hydrogen–oxygen atom ratio of 2:1 (as in water) and thus with the empirical formula (where ''m'' may o ...

is broken into its component sugar molecules by hydrolysis (e.g., sucrose

Sucrose, a disaccharide, is a sugar composed of glucose and fructose subunits. It is produced naturally in plants and is the main constituent of white sugar. It has the molecular formula .

For human consumption, sucrose is extracted and refine ...

being broken down into glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, u ...

and fructose

Fructose, or fruit sugar, is a ketonic simple sugar found in many plants, where it is often bonded to glucose to form the disaccharide sucrose. It is one of the three dietary monosaccharides, along with glucose and galactose, that are absorb ...

), this is recognized as saccharification

In chemistry, saccharification is a term for denoting any chemical change wherein a monosaccharide molecule remains intact after becoming unbound from another saccharide.

For example, when a carbohydrate is broken into its component sugar molecul ...

.

Hydrolysis reactions can be the reverse of a condensation reaction

In organic chemistry, a condensation reaction is a type of chemical reaction in which two molecules are combined to form a single molecule, usually with the loss of a small molecule such as water. If water is lost, the reaction is also known as a ...

in which two molecules join into a larger one and eject a water molecule. Thus hydrolysis adds water to break down, whereas condensation builds up by removing water.

Types

Usually hydrolysis is a chemical process in which a molecule of water is added to a substance. Sometimes this addition causes both the substance and water molecule to split into two parts. In such reactions, one fragment of the target molecule (or parent molecule) gains ahydrogen ion

A hydrogen ion is created when a hydrogen atom loses or gains an electron. A positively charged hydrogen ion (or proton) can readily combine with other particles and therefore is only seen isolated when it is in a gaseous state or a nearly particle ...

. It breaks a chemical bond in the compound.

Salts

A common kind of hydrolysis occurs when asalt

Salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl), a chemical compound belonging to the larger class of salts; salt in the form of a natural crystalline mineral is known as rock salt or halite. Salt is present in vast quant ...

of a weak acid

Acid strength is the tendency of an acid, symbolised by the chemical formula HA, to dissociate into a proton, H+, and an anion, A-. The dissociation of a strong acid in solution is effectively complete, except in its most concentrated solutions ...

or weak base

A weak base is a base that, upon dissolution in water, does not dissociate completely, so that the resulting aqueous solution contains only a small proportion of hydroxide ions and the concerned basic radical, and a large proportion of undissociat ...

(or both) is dissolved in water. Water spontaneously ionizes into hydroxide anions and hydronium cations. The salt also dissociates into its constituent anions and cations. For example, sodium acetate

Sodium acetate, CH3COONa, also abbreviated Na O Ac, is the sodium salt of acetic acid. This colorless deliquescent salt has a wide range of uses.

Applications

Biotechnological

Sodium acetate is used as the carbon source for culturing bacteria ...

dissociates in water into sodium

Sodium is a chemical element with the symbol Na (from Latin ''natrium'') and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 of the periodic table. Its only stable ...

and acetate

An acetate is a salt formed by the combination of acetic acid with a base (e.g. alkaline, earthy, metallic, nonmetallic or radical base). "Acetate" also describes the conjugate base or ion (specifically, the negatively charged ion called ...

ions. Sodium ions react very little with the hydroxide ions whereas the acetate ions combine with hydronium ions to produce acetic acid

Acetic acid , systematically named ethanoic acid , is an acidic, colourless liquid and organic compound with the chemical formula (also written as , , or ). Vinegar is at least 4% acetic acid by volume, making acetic acid the main componen ...

. In this case the net result is a relative excess of hydroxide ions, yielding a basic solution

Solution may refer to:

* Solution (chemistry), a mixture where one substance is dissolved in another

* Solution (equation), in mathematics

** Numerical solution, in numerical analysis, approximate solutions within specified error bounds

* Solutio ...

.

Strong acids

Acid strength is the tendency of an acid, symbolised by the chemical formula HA, to dissociate into a proton, H+, and an anion, A-. The dissociation of a strong acid in solution is effectively complete, except in its most concentrated solutions ...

also undergo hydrolysis. For example, dissolving sulfuric acid

Sulfuric acid (American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphuric acid ( Commonwealth spelling), known in antiquity as oil of vitriol, is a mineral acid composed of the elements sulfur, oxygen and hydrogen, with the molecular fo ...

() in water is accompanied by hydrolysis to give hydronium

In chemistry, hydronium (hydroxonium in traditional British English) is the common name for the aqueous cation , the type of oxonium ion produced by protonation of water. It is often viewed as the positive ion present when an Arrhenius acid ...

and bisulfate

The sulfate or sulphate ion is a polyatomic anion with the empirical formula . Salts, acid derivatives, and peroxides of sulfate are widely used in industry. Sulfates occur widely in everyday life. Sulfates are salts of sulfuric acid and many ...

, the sulfuric acid's conjugate base

A conjugate acid, within the Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory, is a chemical compound formed when an acid donates a proton () to a base—in other words, it is a base with a hydrogen ion added to it, as in the reverse reaction it loses a ...

. For a more technical discussion of what occurs during such a hydrolysis, see Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory

The Brønsted–Lowry theory (also called proton theory of acids and bases) is an acid–base reaction theory which was proposed independently by Johannes Nicolaus Brønsted and Thomas Martin Lowry in 1923. The fundamental concept of this theory ...

.

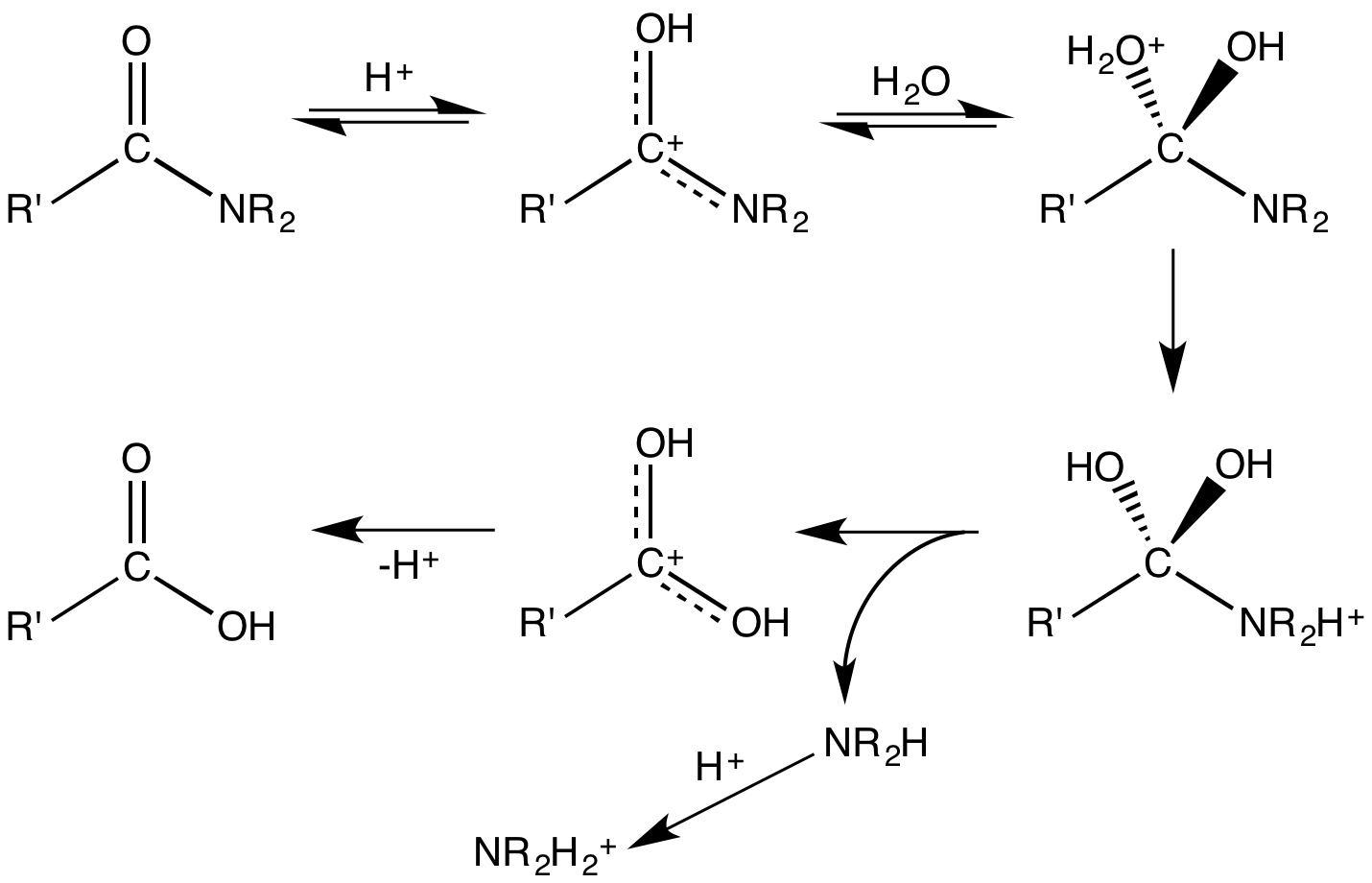

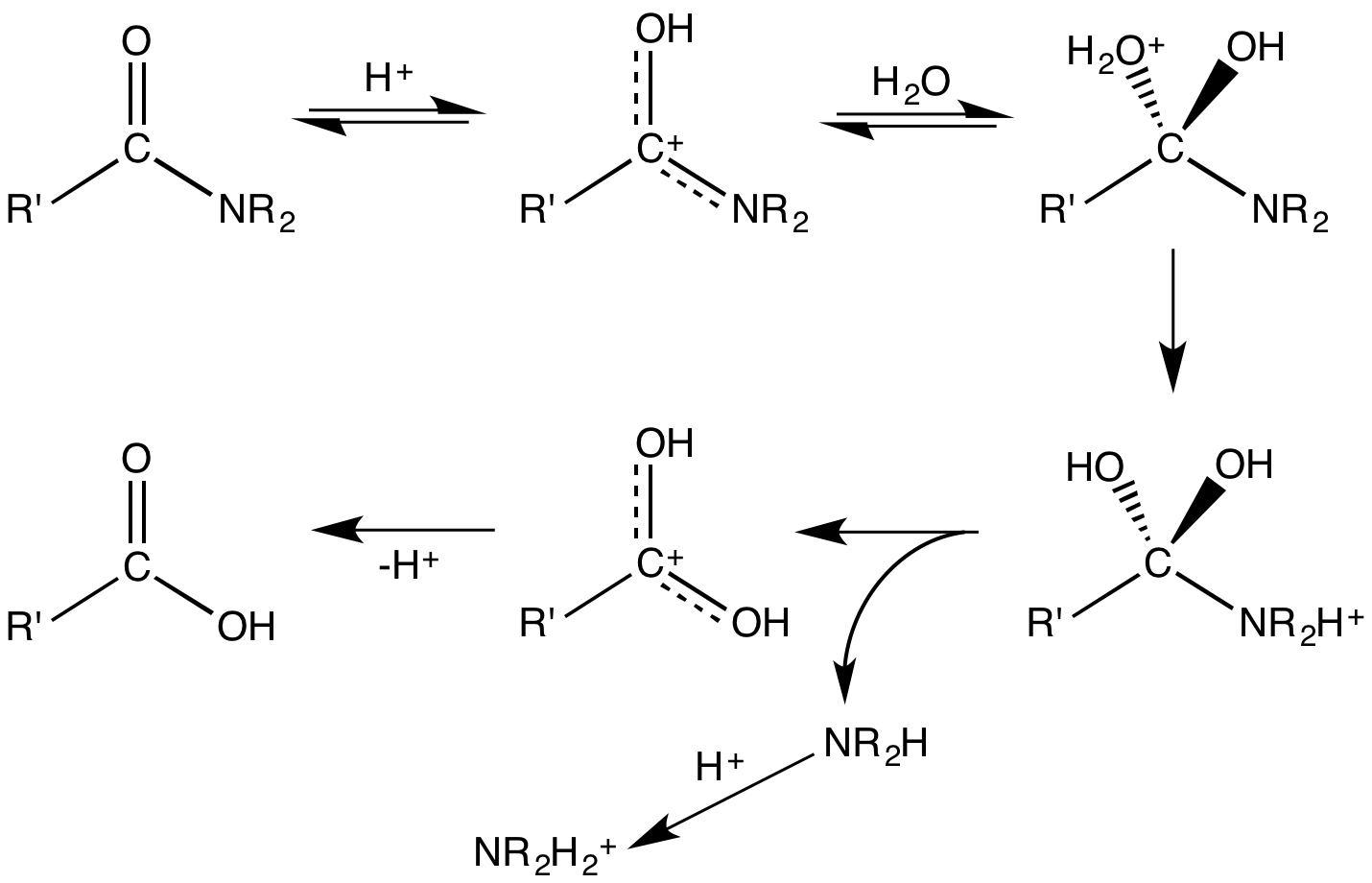

Esters and amides

Acid–base-catalysed hydrolyses are very common; one example is the hydrolysis ofamide

In organic chemistry, an amide, also known as an organic amide or a carboxamide, is a compound with the general formula , where R, R', and R″ represent organic groups or hydrogen atoms. The amide group is called a peptide bond when it i ...

s or ester

In chemistry, an ester is a compound derived from an oxoacid (organic or inorganic) in which at least one hydroxyl group () is replaced by an alkoxy group (), as in the substitution reaction of a carboxylic acid and an alcohol. Glycerides ...

s. Their hydrolysis occurs when the nucleophile

In chemistry, a nucleophile is a chemical species that forms bonds by donating an electron pair. All molecules and ions with a free pair of electrons or at least one pi bond can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they ar ...

(a nucleus-seeking agent, e.g., water or hydroxyl ion) attacks the carbon of the carbonyl group

In organic chemistry, a carbonyl group is a functional group composed of a carbon atom double-bonded to an oxygen atom: C=O. It is common to several classes of organic compounds, as part of many larger functional groups. A compound containi ...

of the ester

In chemistry, an ester is a compound derived from an oxoacid (organic or inorganic) in which at least one hydroxyl group () is replaced by an alkoxy group (), as in the substitution reaction of a carboxylic acid and an alcohol. Glycerides ...

or amide

In organic chemistry, an amide, also known as an organic amide or a carboxamide, is a compound with the general formula , where R, R', and R″ represent organic groups or hydrogen atoms. The amide group is called a peptide bond when it i ...

. In an aqueous base, hydroxyl ions are better nucleophiles than polar molecules such as water. In acids, the carbonyl group becomes protonated, and this leads to a much easier nucleophilic attack. The products for both hydrolyses are compounds with carboxylic acid

In organic chemistry, a carboxylic acid is an organic acid that contains a carboxyl group () attached to an R-group. The general formula of a carboxylic acid is or , with R referring to the alkyl, alkenyl, aryl, or other group. Carboxyli ...

groups.

Perhaps the oldest commercially practiced example of ester hydrolysis is saponification

Saponification is a process of converting esters into soaps and alcohols by the action of aqueous alkali (for example, aqueous sodium hydroxide solutions). Soaps are salts of fatty acids, which in turn are carboxylic acids with long carbon chains. ...

(formation of soap). It is the hydrolysis of a triglyceride

A triglyceride (TG, triacylglycerol, TAG, or triacylglyceride) is an ester derived from glycerol and three fatty acids (from ''tri-'' and ''glyceride'').

Triglycerides are the main constituents of body fat in humans and other vertebrates, as ...

(fat) with an aqueous base such as sodium hydroxide

Sodium hydroxide, also known as lye and caustic soda, is an inorganic compound with the formula NaOH. It is a white solid ionic compound consisting of sodium cations and hydroxide anions .

Sodium hydroxide is a highly caustic base and al ...

(NaOH). During the process, glycerol

Glycerol (), also called glycerine in British English and glycerin in American English, is a simple triol compound. It is a colorless, odorless, viscous liquid that is sweet-tasting and non-toxic. The glycerol backbone is found in lipids known ...

is formed, and the fatty acid

In chemistry, particularly in biochemistry, a fatty acid is a carboxylic acid with an aliphatic chain, which is either saturated or unsaturated. Most naturally occurring fatty acids have an unbranched chain of an even number of carbon atoms, f ...

s react with the base, converting them to salts. These salts are called soaps, commonly used in households.

In addition, in living systems, most biochemical reactions (including ATP hydrolysis) take place during the catalysis of enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products ...

s. The catalytic action of enzymes allows the hydrolysis of protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, res ...

s, fats, oils, and carbohydrate

In organic chemistry, a carbohydrate () is a biomolecule consisting of carbon (C), hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) atoms, usually with a hydrogen–oxygen atom ratio of 2:1 (as in water) and thus with the empirical formula (where ''m'' may o ...

s. As an example, one may consider protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalyzes (increases reaction rate or "speeds up") proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the ...

s (enzymes that aid digestion

Digestion is the breakdown of large insoluble food molecules into small water-soluble food molecules so that they can be absorbed into the watery blood plasma. In certain organisms, these smaller substances are absorbed through the small intest ...

by causing hydrolysis of peptide bond

In organic chemistry, a peptide bond is an amide type of covalent chemical bond linking two consecutive alpha-amino acids from C1 (carbon number one) of one alpha-amino acid and N2 (nitrogen number two) of another, along a peptide or protein cha ...

s in protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, res ...

s). They catalyze the hydrolysis of interior peptide bonds in peptide chains, as opposed to exopeptidase

An exopeptidase is any peptidase that catalyzes the cleavage of the terminal (or the penultimate) peptide bond; the process releases a single amino acid, dipeptide or a tripeptide from the peptide chain. Depending on whether the amino acid is rel ...

s (another class of enzymes, that catalyze the hydrolysis of terminal peptide bonds, liberating one free amino acid at a time).

However, proteases do not catalyze the hydrolysis of all kinds of proteins. Their action is stereo-selective: Only proteins with a certain tertiary structure are targeted as some kind of orienting force is needed to place the amide group in the proper position for catalysis. The necessary contacts between an enzyme and its substrates (proteins) are created because the enzyme folds in such a way as to form a crevice into which the substrate fits; the crevice also contains the catalytic groups. Therefore, proteins that do not fit into the crevice will not undergo hydrolysis. This specificity preserves the integrity of other proteins such as hormone

A hormone (from the Greek participle , "setting in motion") is a class of signaling molecules in multicellular organisms that are sent to distant organs by complex biological processes to regulate physiology and behavior. Hormones are required ...

s, and therefore the biological system continues to function normally.

Upon hydrolysis, an

Upon hydrolysis, an amide

In organic chemistry, an amide, also known as an organic amide or a carboxamide, is a compound with the general formula , where R, R', and R″ represent organic groups or hydrogen atoms. The amide group is called a peptide bond when it i ...

converts into a carboxylic acid

In organic chemistry, a carboxylic acid is an organic acid that contains a carboxyl group () attached to an R-group. The general formula of a carboxylic acid is or , with R referring to the alkyl, alkenyl, aryl, or other group. Carboxyli ...

and an amine

In chemistry, amines (, ) are compounds and functional groups that contain a basic nitrogen atom with a lone pair. Amines are formally derivatives of ammonia (), wherein one or more hydrogen atoms have been replaced by a substituent ...

or ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous ...

(which in the presence of acid are immediately converted to ammonium salts). One of the two oxygen groups on the carboxylic acid are derived from a water molecule and the amine (or ammonia) gains the hydrogen ion. The hydrolysis of peptides

Peptides (, ) are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Long chains of amino acids are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty amino acids are called oligopeptides, and include dipeptides, tripeptides, and tetrapeptides.

...

gives amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha ...

s.

Many polyamide

A polyamide is a polymer with repeating units linked by amide bonds.

Polyamides occur both naturally and artificially. Examples of naturally occurring polyamides are proteins, such as wool and silk. Artificially made polyamides can be made th ...

polymers such as nylon 6,6

Nylon 66 (loosely written nylon 6-6, nylon 6/6, nylon 6,6, or nylon 6:6) is a type of polyamide or nylon. It, and nylon 6, are the two most common for textile and plastic industries. Nylon 66 is made of two monomers each containing 6 carbon atoms ...

hydrolyze in the presence of strong acids. The process leads to depolymerization Depolymerization (or depolymerisation) is the process of converting a polymer into a monomer or a mixture of monomers. This process is driven by an increase in entropy.

Ceiling temperature

The tendency of polymers to depolymerize is indicated by ...

. For this reason nylon products fail by fracturing when exposed to small amounts of acidic water. Polyesters are also susceptible to similar polymer degradation

Polymer degradation is the reduction in the physical properties of a polymer, such as strength, caused by changes in its chemical composition. Polymers and particularly plastics are subject to degradation at all stages of their product life cycl ...

reactions. The problem is known as environmental stress cracking

Environmental Stress Cracking (ESC) is one of the most common causes of unexpected brittle failure of thermoplastic (especially amorphous) polymers known at present. According to ASTM D883, stress cracking is defined as "an external or inter ...

.

ATP

Hydrolysis is related toenergy metabolism

Bioenergetics is a field in biochemistry and cell biology that concerns energy flow through living systems. This is an active area of biological research that includes the study of the transformation of energy in living organisms and the study of ...

and storage. All living cells require a continual supply of energy for two main purposes: the biosynthesis

Biosynthesis is a multi-step, enzyme-catalyzed process where substrates are converted into more complex products in living organisms. In biosynthesis, simple compounds are modified, converted into other compounds, or joined to form macromolecul ...

of micro and macromolecules, and the active transport of ions and molecules across cell membranes. The energy derived from the oxidation

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or ...

of nutrients is not used directly but, by means of a complex and long sequence of reactions, it is channeled into a special energy-storage molecule, adenosine triphosphate

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is an organic compound that provides energy to drive many processes in living cells, such as muscle contraction, nerve impulse propagation, condensate dissolution, and chemical synthesis. Found in all known forms ...

(ATP). The ATP molecule contains pyrophosphate

In chemistry, pyrophosphates are phosphorus oxyanions that contain two phosphorus atoms in a P–O–P linkage. A number of pyrophosphate salts exist, such as disodium pyrophosphate (Na2H2P2O7) and tetrasodium pyrophosphate (Na4P2O7), among othe ...

linkages (bonds formed when two phosphate units are combined) that release energy when needed. ATP can undergo hydrolysis in two ways: Firstly, the removal of terminal phosphate to form adenosine diphosphate

Adenosine diphosphate (ADP), also known as adenosine pyrophosphate (APP), is an important organic compound in metabolism and is essential to the flow of energy in living cells. ADP consists of three important structural components: a sugar backbone ...

(ADP) and inorganic phosphate, with the reaction:

: adenosine monophosphate

Adenosine monophosphate (AMP), also known as 5'-adenylic acid, is a nucleotide. AMP consists of a phosphate group, the sugar ribose, and the nucleobase adenine; it is an ester of phosphoric acid and the nucleoside adenosine. As a substit ...

(AMP) and pyrophosphate

In chemistry, pyrophosphates are phosphorus oxyanions that contain two phosphorus atoms in a P–O–P linkage. A number of pyrophosphate salts exist, such as disodium pyrophosphate (Na2H2P2O7) and tetrasodium pyrophosphate (Na4P2O7), among othe ...

. The latter usually undergoes further cleavage into its two constituent phosphates. This results in biosynthesis reactions, which usually occur in chains, that can be driven in the direction of synthesis when the phosphate bonds have undergone hydrolysis.

Polysaccharides

Monosaccharide

Monosaccharides (from Greek '' monos'': single, '' sacchar'': sugar), also called simple sugars, are the simplest forms of sugar and the most basic units (monomers) from which all carbohydrates are built.

They are usually colorless, water- so ...

s can be linked together by glycosidic bond

A glycosidic bond or glycosidic linkage is a type of covalent bond that joins a carbohydrate (sugar) molecule to another group, which may or may not be another carbohydrate.

A glycosidic bond is formed between the hemiacetal or hemiketal group ...

s, which can be cleaved by hydrolysis. Two, three, several or many monosaccharides thus linked form disaccharide

A disaccharide (also called a double sugar or ''biose'') is the sugar formed when two monosaccharides are joined by glycosidic linkage. Like monosaccharides, disaccharides are simple sugars soluble in water. Three common examples are sucrose, la ...

s, trisaccharide

''Trisaccharides'' are oligosaccharides composed of three monosaccharide

Monosaccharides (from Greek '' monos'': single, '' sacchar'': sugar), also called simple sugars, are the simplest forms of sugar and the most basic units (monomers) from ...

s, oligosaccharide

An oligosaccharide (/ˌɑlɪgoʊˈsækəˌɹaɪd/; from the Greek ὀλίγος ''olígos'', "a few", and σάκχαρ ''sácchar'', "sugar") is a saccharide polymer containing a small number (typically two to ten) of monosaccharides (simple sug ...

s, or polysaccharide

Polysaccharides (), or polycarbohydrates, are the most abundant carbohydrates found in food. They are long chain polymeric carbohydrates composed of monosaccharide units bound together by glycosidic linkages. This carbohydrate can react with w ...

s, respectively. Enzymes that hydrolyze glycosidic bonds are called "glycoside hydrolase

Glycoside hydrolases (also called glycosidases or glycosyl hydrolases) catalyze the hydrolysis of glycosidic bonds in complex sugars. They are extremely common enzymes with roles in nature including degradation of biomass such as cellulose (cel ...

s" or "glycosidases".

The best-known disaccharide is sucrose

Sucrose, a disaccharide, is a sugar composed of glucose and fructose subunits. It is produced naturally in plants and is the main constituent of white sugar. It has the molecular formula .

For human consumption, sucrose is extracted and refine ...

(table sugar). Hydrolysis of sucrose yields glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, u ...

and fructose

Fructose, or fruit sugar, is a ketonic simple sugar found in many plants, where it is often bonded to glucose to form the disaccharide sucrose. It is one of the three dietary monosaccharides, along with glucose and galactose, that are absorb ...

. Invertase

Invertase is an enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis (breakdown) of sucrose (table sugar) into fructose and glucose. Alternative names for invertase include , saccharase, glucosucrase, beta-h-fructosidase, beta-fructosidase, invertin, sucrase, m ...

is a sucrase used industrially for the hydrolysis of sucrose to so-called invert sugar

Inverted sugar syrup, also called invert syrup, invert sugar, simple syrup, sugar syrup, sugar water, bar syrup, syrup USP, or sucrose inversion, is a syrup mixture of the monosaccharides glucose and fructose, that is made by hydrolytic s ...

. Lactase

Lactase is an enzyme produced by many organisms. It is located in the brush border of the small intestine of humans and other mammals. Lactase is essential to the complete digestion of whole milk; it breaks down lactose, a sugar which gives ...

is essential for digestive hydrolysis of lactose

Lactose is a disaccharide sugar synthesized by galactose and glucose subunits and has the molecular formula C12H22O11. Lactose makes up around 2–8% of milk (by mass). The name comes from ' (gen. '), the Latin word for milk, plus the suffix ' ...

in milk; many adult humans do not produce lactase and cannot digest the lactose in milk.

The hydrolysis of polysaccharides to soluble sugars can be recognized as saccharification

In chemistry, saccharification is a term for denoting any chemical change wherein a monosaccharide molecule remains intact after becoming unbound from another saccharide.

For example, when a carbohydrate is broken into its component sugar molecul ...

. Malt made from barley

Barley (''Hordeum vulgare''), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains, particularly in Eurasia as early as 10,000 years ago. Globally 70% of barley p ...

is used as a source of β-amylase to break down starch

Starch or amylum is a polymeric carbohydrate consisting of numerous glucose units joined by glycosidic bonds. This polysaccharide is produced by most green plants for energy storage. Worldwide, it is the most common carbohydrate in human die ...

into the disaccharide maltose

}

Maltose ( or ), also known as maltobiose or malt sugar, is a disaccharide formed from two units of glucose joined with an α(1→4) bond. In the isomer isomaltose, the two glucose molecules are joined with an α(1→6) bond. Maltose is the tw ...

, which can be used by yeast to produce beer. Other amylase

An amylase () is an enzyme that catalyses the hydrolysis of starch (Latin ') into sugars. Amylase is present in the saliva of humans and some other mammals, where it begins the chemical process of digestion. Foods that contain large amounts of ...

enzymes may convert starch to glucose or to oligosaccharides. Cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of β(1→4) linked D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important structural component of the primary cell wa ...

is first hydrolyzed to cellobiose

Cellobiose is a disaccharide with the formula (C6H7(OH)4O)2O. It is classified as a reducing sugar. In terms of its chemical structure, it is derived from the condensation of a pair of β-glucose molecules forming a β(1→4) bond. It can be h ...

by cellulase

Cellulase (EC 3.2.1.4; systematic name 4-β-D-glucan 4-glucanohydrolase) is any of several enzymes produced chiefly by fungi, bacteria, and protozoans that catalyze cellulolysis, the decomposition of cellulose and of some related polysaccha ...

and then cellobiose is further hydrolyzed to glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, u ...

by beta-glucosidase

β-Glucosidase (EC 3.2.1.21; systematic name β-D-glucoside glucohydrolase) is an enzyme that catalyses the following reaction:

: Hydrolysis of terminal, non-reducing β-D-glucosyl residues with release of β-D-glucose

Structure

β-Glucosidase ...

. Ruminants

Ruminants (suborder Ruminantia) are hoofed herbivorous grazing or browsing mammals that are able to acquire nutrients from plant-based food by fermenting it in a specialized stomach prior to digestion, principally through microbial actions. The ...

such as cows are able to hydrolyze cellulose into cellobiose and then glucose because of symbiotic

Symbiosis (from Greek , , "living together", from , , "together", and , bíōsis, "living") is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction between two different biological organisms, be it mutualistic, commensalistic, or para ...

bacteria that produce cellulases.

Metal aqua ions

Metal ions areLewis acid

A Lewis acid (named for the American physical chemist Gilbert N. Lewis) is a chemical species that contains an empty orbital which is capable of accepting an electron pair from a Lewis base to form a Lewis adduct. A Lewis base, then, is any sp ...

s, and in aqueous solution

An aqueous solution is a solution in which the solvent is water. It is mostly shown in chemical equations by appending (aq) to the relevant chemical formula. For example, a solution of table salt, or sodium chloride (NaCl), in water would be r ...

they form metal aquo complex

In chemistry, metal aquo complexes are coordination compounds containing metal ions with only water as a ligand. These complexes are the predominant species in aqueous solutions of many metal salts, such as metal nitrates, sulfates, and perchlorat ...

es of the general formula . The aqua ions undergo hydrolysis, to a greater or lesser extent. The first hydrolysis step is given generically as

:cation

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by conven ...

s behave as acids in terms of Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory

The Brønsted–Lowry theory (also called proton theory of acids and bases) is an acid–base reaction theory which was proposed independently by Johannes Nicolaus Brønsted and Thomas Martin Lowry in 1923. The fundamental concept of this theory ...

. This effect is easily explained by considering the inductive effect

In chemistry, the inductive effect in a molecule is a local change in the electron density due to electron-withdrawing or electron-donating groups elsewhere in the molecule, resulting in a permanent dipole in a bond.

It is present in a σ (sigma ...

of the positively charged metal ion, which weakens the bond of an attached water molecule, making the liberation of a proton relatively easy.

The dissociation constant

In chemistry, biochemistry, and pharmacology, a dissociation constant (K_D) is a specific type of equilibrium constant that measures the propensity of a larger object to separate (dissociate) reversibly into smaller components, as when a complex ...

, pKa, for this reaction is more or less linearly related to the charge-to-size ratio of the metal ion. Ions with low charges, such as are very weak acids with almost imperceptible hydrolysis. Large divalent ions such as , , and have a pKa of 6 or more and would not normally be classed as acids, but small divalent ions such as undergo extensive hydrolysis. Trivalent ions like and are weak acids whose pKa is comparable to that of acetic acid

Acetic acid , systematically named ethanoic acid , is an acidic, colourless liquid and organic compound with the chemical formula (also written as , , or ). Vinegar is at least 4% acetic acid by volume, making acetic acid the main componen ...

. Solutions of salts such as or in water are noticeably acidic

In computer science, ACID ( atomicity, consistency, isolation, durability) is a set of properties of database transactions intended to guarantee data validity despite errors, power failures, and other mishaps. In the context of databases, a ...

; the hydrolysis can be suppressed by adding an acid such as nitric acid

Nitric acid is the inorganic compound with the formula . It is a highly corrosive mineral acid. The compound is colorless, but older samples tend to be yellow cast due to decomposition into oxides of nitrogen. Most commercially available ni ...

, making the solution more acidic.

Hydrolysis may proceed beyond the first step, often with the formation of polynuclear species via the process of olation In inorganic chemistry, olation is the process by which metal ions form polymeric oxides in aqueous solution. The phenomenon is important for understanding the relationship between metal aquo complexes and metal oxides, which are represented by man ...

. Some "exotic" species such as are well characterized. Hydrolysis tends to proceed as pH rises leading, in many cases, to the precipitation of a hydroxide such as or . These substances, major constituents of bauxite

Bauxite is a sedimentary rock with a relatively high aluminium content. It is the world's main source of aluminium and gallium. Bauxite consists mostly of the aluminium minerals gibbsite (Al(OH)3), boehmite (γ-AlO(OH)) and diaspore (α-AlO ...

, are known as laterite

Laterite is both a soil and a rock type rich in iron and aluminium and is commonly considered to have formed in hot and wet tropical areas. Nearly all laterites are of rusty-red coloration, because of high iron oxide content. They develop by ...

s and are formed by leaching from rocks of most of the ions other than aluminium and iron and subsequent hydrolysis of the remaining aluminium and iron.

Mechanism strategies

Acetal

In organic chemistry, an acetal is a functional group with the connectivity . Here, the R groups can be organic fragments (a carbon atom, with arbitrary other atoms attached to that) or hydrogen, while the R' groups must be organic fragments n ...

s, imine

In organic chemistry, an imine ( or ) is a functional group or organic compound containing a carbon–nitrogen double bond (). The nitrogen atom can be attached to a hydrogen or an organic group (R). The carbon atom has two additional single bon ...

s, and enamines can be converted back into ketone

In organic chemistry, a ketone is a functional group with the structure R–C(=O)–R', where R and R' can be a variety of carbon-containing substituents. Ketones contain a carbonyl group –C(=O)– (which contains a carbon-oxygen double b ...

s by treatment with excess water under acid-catalyzed conditions: ; ; .

See also

*Acid hydrolysis

In organic chemistry, acid hydrolysis is a hydrolysis process in which a protic acid is used to catalyze the cleavage of a chemical bond via a nucleophilic substitution reaction, with the addition of the elements of water (H2O). For example, in th ...

* Adenosine triphosphate

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is an organic compound that provides energy to drive many processes in living cells, such as muscle contraction, nerve impulse propagation, condensate dissolution, and chemical synthesis. Found in all known forms ...

* Alkaline hydrolysis (body disposal)

Alkaline hydrolysis (also called biocremation, resomation, flameless cremation, aquamation or water cremation) is a process for the disposal of human and pet remains using lye and heat, and is an alternative to burial or cremation.

Process

The p ...

* Catabolism

Catabolism () is the set of metabolic pathways that breaks down molecules into smaller units that are either oxidized to release energy or used in other anabolic reactions. Catabolism breaks down large molecules (such as polysaccharides, li ...

* Condensation reaction

In organic chemistry, a condensation reaction is a type of chemical reaction in which two molecules are combined to form a single molecule, usually with the loss of a small molecule such as water. If water is lost, the reaction is also known as a ...

* Dehydration reaction

In chemistry, a dehydration reaction is a chemical reaction that involves the loss of water from the reacting molecule or ion. Dehydration reactions are common processes, the reverse of a hydration reaction.

Dehydration reactions in organic ch ...

* Hydrolysis constant

* Inhibitor protein

The inhibitor protein (IP) is situated in the mitochondrial matrix and protects the cell against rapid ATP hydrolysis

Hydrolysis (; ) is any chemical reaction in which a molecule of water breaks one or more chemical bonds. The term is used ...

* Polymer degradation

Polymer degradation is the reduction in the physical properties of a polymer, such as strength, caused by changes in its chemical composition. Polymers and particularly plastics are subject to degradation at all stages of their product life cycl ...

* Proteolysis

Proteolysis is the breakdown of proteins into smaller polypeptides or amino acids. Uncatalysed, the hydrolysis of peptide bonds is extremely slow, taking hundreds of years. Proteolysis is typically catalysed by cellular enzymes called protease ...

* Saponification

Saponification is a process of converting esters into soaps and alcohols by the action of aqueous alkali (for example, aqueous sodium hydroxide solutions). Soaps are salts of fatty acids, which in turn are carboxylic acids with long carbon chains. ...

* Sol–gel polymerisation

* Solvolysis

In chemistry, solvolysis is a type of nucleophilic substitution (S1/S2) or elimination reaction, elimination where the nucleophile is a solvent molecule. Characteristic of S1 reactions, solvolysis of a chirality (chemistry), chiral reactant affor ...

* Thermal hydrolysis

References

{{Authority control Chemical reactions Equilibrium chemistry