Hussite wars on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Hussite Wars, also called the Bohemian Wars or the Hussite Revolution, were a series of civil wars fought between the

Starting around 1402, priest and scholar

Starting around 1402, priest and scholar

Late 14th and early 15th century saw gradually increasing use of firearms in siege operations both by defenders and attackers. Weight, lack of accuracy and cumbersome use of early types limited their employment to static operations and prevented wider use in open battlefield or by civilian individuals. Nevertheless, lack of guild monopolies and low training requirements led to their relatively low price. This together with high effectiveness against armour led to their popularity for castle and town defenses.

When the Hussite revolt started in 1419, the Hussite militias heavily depended on converted farm equipment and weapons looted from castle and town armories, including early firearms. Hussite militia comprised mostly commoners without prior military experience, and included both men and women. Use of crossbows and firearms became critical as those weapons didn't require extensive training, nor did their effectiveness rely on the operator's physical strength.

Firearms were first used in the field as provisional last resort together with wagon fort. Significantly outnumbered Hussite militia led by

Late 14th and early 15th century saw gradually increasing use of firearms in siege operations both by defenders and attackers. Weight, lack of accuracy and cumbersome use of early types limited their employment to static operations and prevented wider use in open battlefield or by civilian individuals. Nevertheless, lack of guild monopolies and low training requirements led to their relatively low price. This together with high effectiveness against armour led to their popularity for castle and town defenses.

When the Hussite revolt started in 1419, the Hussite militias heavily depended on converted farm equipment and weapons looted from castle and town armories, including early firearms. Hussite militia comprised mostly commoners without prior military experience, and included both men and women. Use of crossbows and firearms became critical as those weapons didn't require extensive training, nor did their effectiveness rely on the operator's physical strength.

Firearms were first used in the field as provisional last resort together with wagon fort. Significantly outnumbered Hussite militia led by  Throughout 1420 and most of 1421 the Hussite tactical use of wagonfort and firearms was defensive. The wagons wall was stationary and firearms were used to break initial charge of the enemy. After this, firearms played auxiliary role supporting mainly cold weapons based defense at the level of the wagon wall. Counterattacks were done by cold weapons armed infantry and cavalry charges outside of the wagon fort.

The first mobile use of war wagons and firearms took place during the Hussite breakthrough of Catholic encirclement at in November 1421 at the . The wagons and firearms were used on the move, at this point still only defensively. Žižka avoided the main camp of the enemy and employed the moving wagon fort in order to cover his retreating troops.

The first true engagement where firearms played primary role happened a month later during the

Throughout 1420 and most of 1421 the Hussite tactical use of wagonfort and firearms was defensive. The wagons wall was stationary and firearms were used to break initial charge of the enemy. After this, firearms played auxiliary role supporting mainly cold weapons based defense at the level of the wagon wall. Counterattacks were done by cold weapons armed infantry and cavalry charges outside of the wagon fort.

The first mobile use of war wagons and firearms took place during the Hussite breakthrough of Catholic encirclement at in November 1421 at the . The wagons and firearms were used on the move, at this point still only defensively. Žižka avoided the main camp of the enemy and employed the moving wagon fort in order to cover his retreating troops.

The first true engagement where firearms played primary role happened a month later during the

After the death of his childless brother Wenceslaus, Sigismund inherited a claim on the Bohemian crown, though it was then, and remained till much later, in question whether Bohemia was a hereditary or an elective monarchy, especially as the line through which Sigismund claimed the throne had accepted that the Kingdom of Bohemia was an elective monarchy elected by the nobles, and thus the regent of the kingdom (ÄenÄk of Wartenberg) also explicitly stated that Sigismund had not been elected as reason for Sigismund's claim to not be accepted. A firm adherent of the Church of Rome, Sigismund was aided by

After the death of his childless brother Wenceslaus, Sigismund inherited a claim on the Bohemian crown, though it was then, and remained till much later, in question whether Bohemia was a hereditary or an elective monarchy, especially as the line through which Sigismund claimed the throne had accepted that the Kingdom of Bohemia was an elective monarchy elected by the nobles, and thus the regent of the kingdom (ÄenÄk of Wartenberg) also explicitly stated that Sigismund had not been elected as reason for Sigismund's claim to not be accepted. A firm adherent of the Church of Rome, Sigismund was aided by  These articles, which contain the essence of the Hussite doctrine, were rejected by King Sigismund, mainly through the influence of the

These articles, which contain the essence of the Hussite doctrine, were rejected by King Sigismund, mainly through the influence of the

Bohemia was for a time free from foreign intervention, but internal discord again broke out, caused partly by theological strife and partly by the ambition of agitators. On 9 March 1422, Jan ŽelivskĆ½ was arrested by the town council of Prague and beheaded. There were troubles at TĆ”bor also, where a more radical party opposed Žižka's authority.

Bohemia was for a time free from foreign intervention, but internal discord again broke out, caused partly by theological strife and partly by the ambition of agitators. On 9 March 1422, Jan ŽelivskĆ½ was arrested by the town council of Prague and beheaded. There were troubles at TĆ”bor also, where a more radical party opposed Žižka's authority.

Papal influence had succeeded in calling forth a new crusade against Bohemia, but it resulted in complete failure. In spite of the endeavours of their rulers, Poles and Lithuanians did not wish to attack the kindred Czechs; the Germans were prevented by internal discord from taking joint action against the Hussites; and King Eric VII of Denmark, who had landed in Germany with a large force intending to take part in the crusade, soon returned to his own country. Free for a time from foreign threat, the Hussites invaded Moravia, where a large part of the population favored their creed; but, paralysed again by dissensions, they soon returned to Bohemia.

The city of

Papal influence had succeeded in calling forth a new crusade against Bohemia, but it resulted in complete failure. In spite of the endeavours of their rulers, Poles and Lithuanians did not wish to attack the kindred Czechs; the Germans were prevented by internal discord from taking joint action against the Hussites; and King Eric VII of Denmark, who had landed in Germany with a large force intending to take part in the crusade, soon returned to his own country. Free for a time from foreign threat, the Hussites invaded Moravia, where a large part of the population favored their creed; but, paralysed again by dissensions, they soon returned to Bohemia.

The city of

In 1426, the Hussites were attacked again by foreign enemies. In June 1426 Hussite forces, led by Prokop and Sigismund Korybut, significantly defeated the invaders in the

In 1426, the Hussites were attacked again by foreign enemies. In June 1426 Hussite forces, led by Prokop and Sigismund Korybut, significantly defeated the invaders in the

During the Hussite Wars, the Hussites launched raids against many bordering countries. The Hussites called them ''SpanilĆ© jĆzdy'' ("glorious rides"). Especially under the leadership of Prokop the Great, Hussites invaded

During the Hussite Wars, the Hussites launched raids against many bordering countries. The Hussites called them ''SpanilĆ© jĆzdy'' ("glorious rides"). Especially under the leadership of Prokop the Great, Hussites invaded

On 1 August 1431, a large army of crusaders under Frederick I, Elector of Brandenburg, accompanied by Cardinal Cesarini as

On 1 August 1431, a large army of crusaders under Frederick I, Elector of Brandenburg, accompanied by Cardinal Cesarini as

On 15 October 1431, the Council of Basel issued a formal invitation to the Hussites to take part in its deliberations. Prolonged negotiations ensued, but a Hussite embassy, led by Prokop and including John of Rokycan, the Taborite bishop Nicolas of PelhÅimov, the "English Hussite" Peter Payne and many others, arrived at Basel on 4 January 1433. No agreement could be reached, but negotiations were not broken off, and a change in the political situation of Bohemia finally resulted in a settlement.

In 1434, war again broke out between the Utraquists and the Taborites. On 30 May 1434, the Taborite army, led by Prokop the Great and Prokop the Lesser, who both fell in the battle, was totally defeated and almost annihilated at the Battle of Lipany.

The Polish Hussite movement also came to an end. Polish royal troops under

On 15 October 1431, the Council of Basel issued a formal invitation to the Hussites to take part in its deliberations. Prolonged negotiations ensued, but a Hussite embassy, led by Prokop and including John of Rokycan, the Taborite bishop Nicolas of PelhÅimov, the "English Hussite" Peter Payne and many others, arrived at Basel on 4 January 1433. No agreement could be reached, but negotiations were not broken off, and a change in the political situation of Bohemia finally resulted in a settlement.

In 1434, war again broke out between the Utraquists and the Taborites. On 30 May 1434, the Taborite army, led by Prokop the Great and Prokop the Lesser, who both fell in the battle, was totally defeated and almost annihilated at the Battle of Lipany.

The Polish Hussite movement also came to an end. Polish royal troops under

The Utraquist creed, frequently varying in its details, continued to be that of the established church of Bohemia until all non-Catholic religious services were prohibited shortly after the

The Utraquist creed, frequently varying in its details, continued to be that of the established church of Bohemia until all non-Catholic religious services were prohibited shortly after the

Joan of Arc's Letter to the Hussites

(23 March 1430) ā In 1430,

Tactics of the Hussite Wars

Jan Hus and the Hussite Wars

o

Medieval Archives Podcast

{{Authority control 15th-century crusades European wars of religion Wars involving the Teutonic Order

Hussites

The Hussites ( cs, HusitĆ© or ''KaliÅ”nĆci''; "Chalice People") were a Czech proto-Protestant Christian movement that followed the teachings of reformer Jan Hus, who became the best known representative of the Bohemian Reformation.

The Huss ...

and the combined Catholic forces of Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund

Sigismund of Luxembourg (15 February 1368 ā 9 December 1437) was a monarch as King of Hungary and Croatia (''jure uxoris'') from 1387, King of Germany from 1410, King of Bohemia from 1419, and Holy Roman Emperor from 1433 until his death in ...

, the Papacy

The pope ( la, papa, from el, ĻĪ¬ĻĻĪ±Ļ, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

, European monarchs loyal to the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

, as well as various Hussite factions. At a late stage of the conflict, the Utraquists

Utraquism (from the Latin ''sub utraque specie'', meaning "under both kinds") or Calixtinism (from chalice; Latin: ''calix'', mug, borrowed from Greek ''kalyx'', shell, husk; Czech: kaliÅ”nĆci) was a belief amongst Hussites, a reformist Chri ...

changed sides in 1432 to fight alongside Roman Catholics and opposed the Taborites

The Taborites ( cs, TƔboritƩ, cs, singular TƔborita), known by their enemies as the Picards, were a faction within the Hussite movement in the medieval Lands of the Bohemian Crown.

Although most of the Taborites were of rural origin, the ...

and other Hussite spinoffs. These wars lasted from 1419 to approximately 1434.

The unrest began after pre-Protestant Christian reformer Jan Hus

Jan Hus (; ; 1370 ā 6 July 1415), sometimes anglicized as John Hus or John Huss, and referred to in historical texts as ''Iohannes Hus'' or ''Johannes Huss'', was a Czech theologian and philosopher who became a Church reformer and the insp ...

was executed by the Catholic Church in 1415 for heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important relig ...

. Because the King Wenceslaus IV

Wenceslaus IV (also ''Wenceslas''; cs, VƔclav; german: Wenzel, nicknamed "the Idle"; 26 February 136116 August 1419), also known as Wenceslaus of Luxembourg, was King of Bohemia from 1378 until his death and King of Germany from 1376 until he ...

of Bohemia had plans to be crowned the Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Rƶmer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

(requiring Papal Coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the presentation of o ...

), he suppressed the religion of the Hussites, yet it continued to spread. When King Wenceslaus IV died of natural causes a few years later, the tension stemming from the Hussites grew stronger. In Prague and various other parts of Bohemia, the Catholic Germans living there were forced out.

Wenceslaus's brother, Sigismund, who had inherited the throne, was outraged by the spread of Hussitism. He got permission from the pope to launch a crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

against the Hussites, and large numbers of crusaders came from all over Europe to fight. They made early advances, forcing the Hussites back and taking Prague. However, the Hussites subsequently laid siege to the garrison of crusaders and took back nearly all of the land they had previously captured, resulting in the failure of the crusade.

After the reins of the Hussite army were handed over to yeoman Jan Žižka

Jan Žižka z Trocnova a Kalicha ( en, John Zizka of Trocnov and the Chalice; 1360 ā 11 October 1424) was a Czech general ā a contemporary and follower of Jan Hus and a Radical Hussite who led the Taborites. Žižka was a successful milit ...

, internal strife followed. Seeing that the Hussites were weakened, the Germans undertook another crusade, but were defeated by Žižka at the Battle of Deutschbrod

The Battle of Deutschbrod''Encyclopedia Americana'' or NÄmeckĆ½ Brod took place on 10 January 1422, in Deutschbrod (NÄmeckĆ½ Brod, now HavlĆÄkÅÆv Brod), Bohemia, during the Hussite Wars. Led by Jan Žižka, the Hussites

The Hussites ( cs, ...

. Three more crusades were attempted by the papacy

The pope ( la, papa, from el, ĻĪ¬ĻĻĪ±Ļ, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

, but none achieved their objectives. The Lithuanians and Poles did not wish to attack the Czechs, Germany was having internal conflicts and could not muster up a sufficient force to battle the Hussites, and the king of Denmark

The monarchy of Denmark is a constitutional institution and a historic office of the Kingdom of Denmark. The Kingdom includes Denmark proper and the autonomous territories of the Faroe Islands and Greenland. The Kingdom of Denmark was alre ...

left the Czech border to go back to his home. As the conflicts went on, the Hussites also made raids into German territory.

The wars eventually ended in 1434 when the moderate Utraquist

Utraquism (from the Latin ''sub utraque specie'', meaning "under both kinds") or Calixtinism (from chalice; Latin: ''calix'', mug, borrowed from Greek ''kalyx'', shell, husk; Czech: kaliÅ”nĆci) was a belief amongst Hussites, a reformist Christi ...

faction of the Hussites defeated the radical Taborite faction. The Hussites agreed to submit to the authority of the king of Bohemia

The Duchy of Bohemia was established in 870 and raised to the Kingdom of Bohemia in 1198. Several Bohemian monarchs ruled as non-hereditary kings beforehand, first gaining the title in 1085. From 1004 to 1806, Bohemia was part of the Holy Roman ...

and the Roman Catholic Church, and were allowed to practice their somewhat variant rite.

The Hussite community included much of the Czech population of the Kingdom of Bohemia

The Kingdom of Bohemia ( cs, ÄeskĆ© krĆ”lovstvĆ),; la, link=no, Regnum Bohemiae sometimes in English literature referred to as the Czech Kingdom, was a medieval and early modern monarchy in Central Europe, the predecessor of the modern Czec ...

and formed a major spontaneous military power. The Hussite Wars were notable for the extensive use of early hand-held firearms such as hand cannons, as well as wagon forts.

Origins

Starting around 1402, priest and scholar

Starting around 1402, priest and scholar Jan Hus

Jan Hus (; ; 1370 ā 6 July 1415), sometimes anglicized as John Hus or John Huss, and referred to in historical texts as ''Iohannes Hus'' or ''Johannes Huss'', was a Czech theologian and philosopher who became a Church reformer and the insp ...

denounced what he judged as the corruption of the church and the papacy, and he promoted some of the reformist ideas of English theologian John Wycliffe

John Wycliffe (; also spelled Wyclif, Wickliffe, and other variants; 1328 ā 31 December 1384) was an English scholastic philosopher, theologian, biblical translator, reformer, Catholic priest, and a seminary professor at the University of ...

. His preaching was widely heeded in Bohemia, and provoked suppression by the church, which had declared many of Wycliffe's ideas heretical. In 1411, in the course of the Western Schism

The Western Schism, also known as the Papal Schism, the Vatican Standoff, the Great Occidental Schism, or the Schism of 1378 (), was a split within the Catholic Church lasting from 1378 to 1417 in which bishops residing in Rome and Avignon b ...

, "Antipope

An antipope ( la, antipapa) is a person who makes a significant and substantial attempt to occupy the position of Bishop of Rome and leader of the Catholic Church in opposition to the legitimately elected pope. At times between the 3rd and mi ...

" John XXIII

Pope John XXIII ( la, Ioannes XXIII; it, Giovanni XXIII; born Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli, ; 25 November 18813 June 1963) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 28 October 1958 until his death in June ...

proclaimed a "crusade" against King Ladislaus of Naples, the protector of rival Pope Gregory XII

Pope Gregory XII ( la, Gregorius XII; it, Gregorio XII; ā 18 October 1417), born Angelo Corraro, Corario," or Correr, was head of the Catholic Church from 30 November 1406 to 4 July 1415. Reigning during the Western Schism, he was oppos ...

. To raise money for this, he proclaimed indulgences

In the teaching of the Catholic Church, an indulgence (, from , 'permit') is "a way to reduce the amount of punishment one has to undergo for sins". The ''Catechism of the Catholic Church'' describes an indulgence as "a remission before God o ...

in Bohemia. Hus bitterly denounced this and explicitly quoted Wycliffe against it, provoking further complaints of heresy but winning much support in Bohemia.

In 1414, Sigismund of Hungary convened the Council of Constance

The Council of Constance was a 15th-century ecumenical council recognized by the Catholic Church, held from 1414 to 1418 in the Bishopric of Constance in present-day Germany. The council ended the Western Schism by deposing or accepting the r ...

to end the Schism and resolve other religious controversies. Hus went to the Council, under a safe-conduct from Sigismund, but was imprisoned, tried, and executed on 6 July 1415. The knights and nobles of Bohemia and Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, MƤhren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The ...

, who were in favour of church reform, sent the ''protestatio Bohemorum'' to the Council of Constance on 2 September 1415, which condemned the execution of Hus in the strongest language. This angered Sigismund, who was "King of the Romans

King of the Romans ( la, Rex Romanorum; german: Kƶnig der Rƶmer) was the title used by the king of Germany following his election by the princes from the reign of Henry II (1002ā1024) onward.

The title originally referred to any German k ...

" (head of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

, though not yet Emperor), and brother of King Wenceslaus of Bohemia

Wenceslaus, Wenceslas, Wenzeslaus and Wenzslaus (and other similar names) are Latinized forms of the Slavic names#In Slovakia and Czech_Republic, Czech name VĆ”clav. The other language versions of the name are german: Wenzel, pl, WacÅaw, WiÄcesÅ ...

. He had been persuaded by the Council that Hus was a heretic. He sent threatening letters to Bohemia declaring that he would shortly drown all Wycliffites and Hussites, greatly incensing the people.

Disorder broke out in various parts of Bohemia, and drove many Catholic priests from their parishes. Almost from the beginning the Hussites divided into two main groups, though many minor divisions also arose among them. Shortly before his death Hus had accepted the doctrine of Utraquism preached during his absence by his adherents at Prague: the obligation of the faithful to receive communion in both kinds, bread and wine (''sub utraque specie''). This doctrine became the watchword of the moderate Hussites known as the Utraquists or Calixtines, from the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

''calix'' (the chalice), in Czech ''KaliÅ”nĆci'' (from ''kalich''). The more extreme Hussites became known as Taborites

The Taborites ( cs, TƔboritƩ, cs, singular TƔborita), known by their enemies as the Picards, were a faction within the Hussite movement in the medieval Lands of the Bohemian Crown.

Although most of the Taborites were of rural origin, the ...

(''TƔboritƩ''), after the town of TƔbor

TƔbor (; german: Tabor) is a town in the South Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 33,000 inhabitants. The town centre is well preserved and is protected by law as an urban monument reservation.

Administrative parts

The follow ...

that became their centre; or Orphans (''Sirotci''), a name they adopted after the death of their leader and general Jan Žižka.

Under the influence of Sigismund, Wenceslaus endeavoured to stem the Hussite movement. A number of Hussites led by MikulĆ”Å” of Hus left Prague. They held meetings in various parts of Bohemia, particularly at Sezimovo ĆstĆ, near the spot where the town of TĆ”bor was founded soon afterwards. At these meetings they violently denounced Sigismund, and the people everywhere prepared for war.

In spite of the departure of many prominent Hussites, the troubles at Prague continued. On 30 July 1419 a Hussite procession headed by the priest Jan ŽelivskĆ½

Jan ŽelivskĆ½ (1380 in Humpolec ā 9 March 1422 in Prague) was a prominent Czech priest during the Hussite Reformation.

Life

ŽelivskĆ½ preached at Church of Saint Mary Major. He was one of a few Utraquist

Utraquism (from the Latin ''sub u ...

attacked New Town Hall in Prague and threw the king's representatives, the burgomaster, and some town councillors from the windows into the street (the first "Defenestration of Prague

The Defenestrations of Prague ( cs, PražskĆ” defenestrace, german: Prager Fenstersturz, la, Defenestratio Pragensis) were three incidents in the history of Bohemia in which people were defenestrated (thrown out of a window). Though already exi ...

"), where several were killed by the fall, after a rock was allegedly thrown from the town hall and hit ŽelivskĆ½. It has been suggested that Wenceslaus was so stunned by the defenestration that it caused his death on 16 August 1419. Alternatively, it is possible that he may have just died of natural causes.

The outbreak of fighting

The death of Wenceslaus resulted in renewed troubles in Prague and in almost all parts of Bohemia. Many Catholics, mostly Germans ā mostly still faithful to the Pope ā were expelled from the Bohemian cities. Wenceslaus' widowSophia of Bavaria

Sophia of Bavaria (; ; 1376 ā 4 November 1428In a Munich archive, letters of Sophia from the years 1422ā1427 have been found. B. KopiÄkovĆ”, MnichovskĆ½ fascikl Ä. 543. Korespondence krĆ”lovny Žofie z obdobĆ bÅezen 1422 ā prosinec 14 ...

, acting as regent in Bohemia, hurriedly collected a force of mercenaries and tried to gain control of Prague, which led to severe fighting. After a considerable part of the city had been damaged or destroyed, the parties declared a truce on 13 November. The nobles, sympathetic to the Hussite cause, but supporting the regent, promised to act as mediators with Sigismund, while the citizens of Prague consented to restore to the royal forces the castle of VyŔehrad

VyŔehrad ( Czech for "upper castle") is a historic fort in Prague, Czech Republic, just over 3 km southeast of Prague Castle, on the east bank of the Vltava River. It was probably built in the 10th century. Inside the fort are the Basil ...

, which had fallen into their hands. Žižka, who disapproved of this compromise, left Prague and retired to PlzeÅ

PlzeÅ (; German and English: Pilsen, in German ) is a city in the Czech Republic. About west of Prague in western Bohemia, it is the fourth most populous city in the Czech Republic with about 169,000 inhabitants.

The city is known worldwid ...

. Unable to maintain himself there he marched to southern Bohemia. He defeated the Catholics at the Battle of SudomÄÅ (25 March 1420), the first pitched battle of the Hussite wars. After SudomÄÅ, he moved to ĆstĆ, one of the earliest meeting-places of the Hussites. Not considering its situation sufficiently strong, he moved to the neighboring new settlement of the Hussites, called by the biblical name of TĆ”bor

TƔbor (; german: Tabor) is a town in the South Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 33,000 inhabitants. The town centre is well preserved and is protected by law as an urban monument reservation.

Administrative parts

The follow ...

.

TĆ”bor soon became the center of the most militant Hussites, who differed from the Utraquists by recognizing only two sacraments ā Baptism

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, Ī²Ī¬ĻĻĪ¹ĻĪ¼Ī±, vĆ”ptisma) is a form of ritual purificationāa characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost ...

and Communion ā and by rejecting most of the ceremony of the Roman Catholic Church. The ecclesiastical organization of Tabor had a somewhat puritanical character, and the government was established on a thoroughly democratic basis. Four captains of the people (''hejtmanĆ©'') were elected, one of whom was Žižka, and a very strict military discipline was instituted.

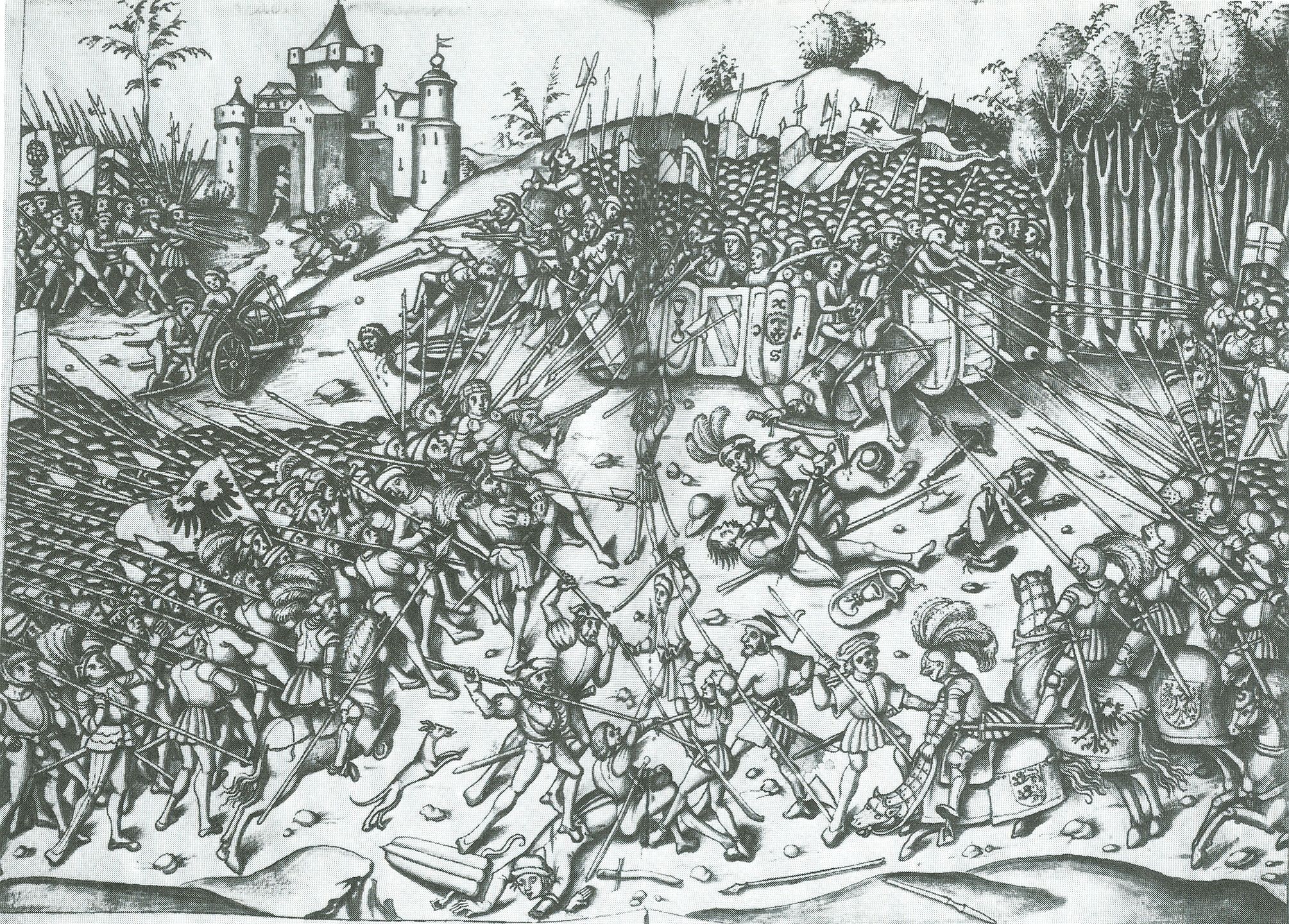

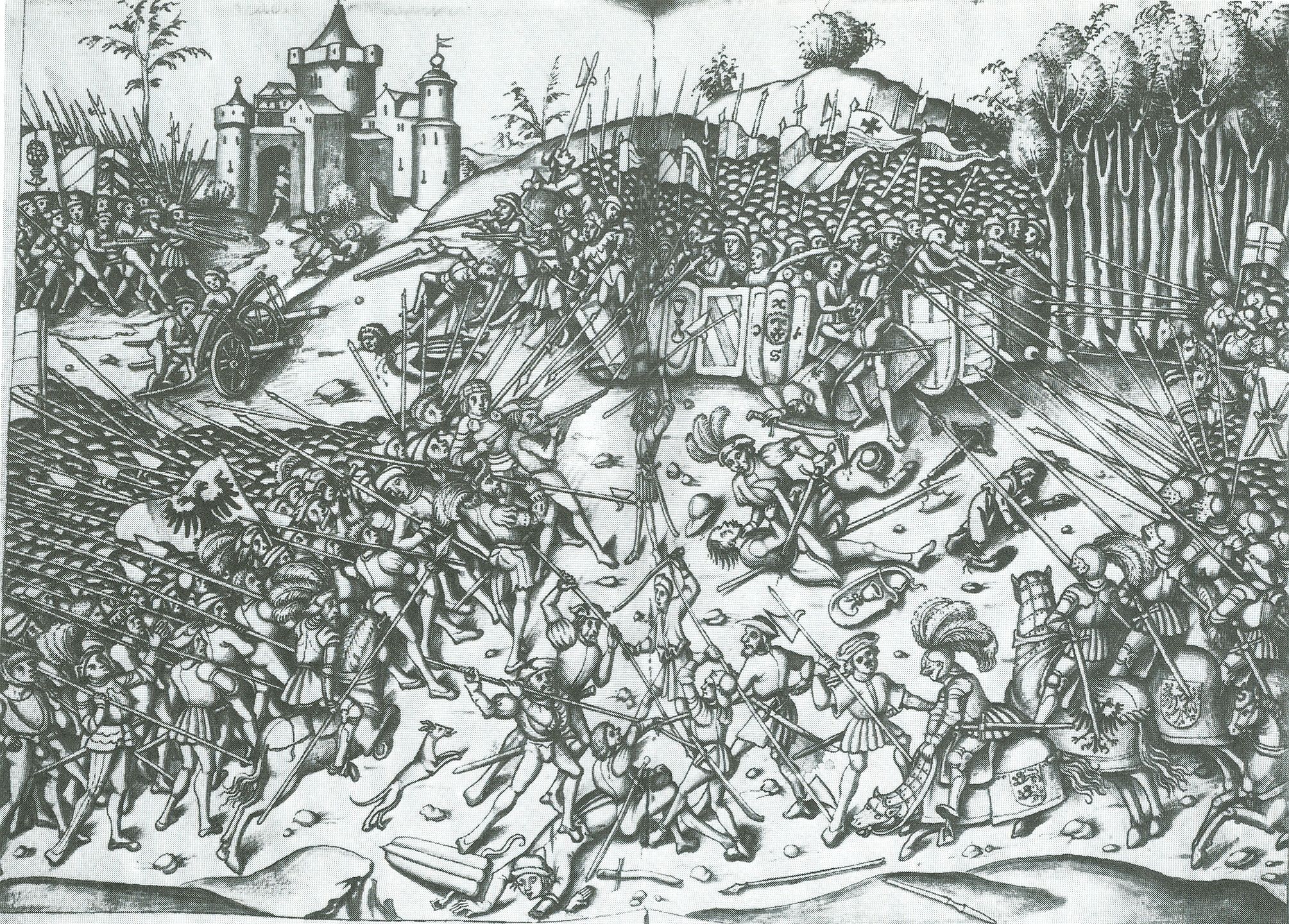

Use of war wagons and firearms

Late 14th and early 15th century saw gradually increasing use of firearms in siege operations both by defenders and attackers. Weight, lack of accuracy and cumbersome use of early types limited their employment to static operations and prevented wider use in open battlefield or by civilian individuals. Nevertheless, lack of guild monopolies and low training requirements led to their relatively low price. This together with high effectiveness against armour led to their popularity for castle and town defenses.

When the Hussite revolt started in 1419, the Hussite militias heavily depended on converted farm equipment and weapons looted from castle and town armories, including early firearms. Hussite militia comprised mostly commoners without prior military experience, and included both men and women. Use of crossbows and firearms became critical as those weapons didn't require extensive training, nor did their effectiveness rely on the operator's physical strength.

Firearms were first used in the field as provisional last resort together with wagon fort. Significantly outnumbered Hussite militia led by

Late 14th and early 15th century saw gradually increasing use of firearms in siege operations both by defenders and attackers. Weight, lack of accuracy and cumbersome use of early types limited their employment to static operations and prevented wider use in open battlefield or by civilian individuals. Nevertheless, lack of guild monopolies and low training requirements led to their relatively low price. This together with high effectiveness against armour led to their popularity for castle and town defenses.

When the Hussite revolt started in 1419, the Hussite militias heavily depended on converted farm equipment and weapons looted from castle and town armories, including early firearms. Hussite militia comprised mostly commoners without prior military experience, and included both men and women. Use of crossbows and firearms became critical as those weapons didn't require extensive training, nor did their effectiveness rely on the operator's physical strength.

Firearms were first used in the field as provisional last resort together with wagon fort. Significantly outnumbered Hussite militia led by Jan Žižka

Jan Žižka z Trocnova a Kalicha ( en, John Zizka of Trocnov and the Chalice; 1360 ā 11 October 1424) was a Czech general ā a contemporary and follower of Jan Hus and a Radical Hussite who led the Taborites. Žižka was a successful milit ...

repulsed surprise assaults by heavy cavalry during Battle of NekmĆÅ in December 1419 and Battle of SudomÄÅ in March 1420. In these battles, Žižka employed transport carriages as wagon fort to stop enemy's cavalry charge. Main weight of fighting rested on militiamen armed with cold weapons, however firearms shooting from behind the safety of the wagon fort proved to be very effective. Following this experience, Žižka ordered mass manufacturing of war wagons according to a universal template as well as manufacturing of new types of firearms that would be more suitable for use in the open battlefield.

Throughout 1420 and most of 1421 the Hussite tactical use of wagonfort and firearms was defensive. The wagons wall was stationary and firearms were used to break initial charge of the enemy. After this, firearms played auxiliary role supporting mainly cold weapons based defense at the level of the wagon wall. Counterattacks were done by cold weapons armed infantry and cavalry charges outside of the wagon fort.

The first mobile use of war wagons and firearms took place during the Hussite breakthrough of Catholic encirclement at in November 1421 at the . The wagons and firearms were used on the move, at this point still only defensively. Žižka avoided the main camp of the enemy and employed the moving wagon fort in order to cover his retreating troops.

The first true engagement where firearms played primary role happened a month later during the

Throughout 1420 and most of 1421 the Hussite tactical use of wagonfort and firearms was defensive. The wagons wall was stationary and firearms were used to break initial charge of the enemy. After this, firearms played auxiliary role supporting mainly cold weapons based defense at the level of the wagon wall. Counterattacks were done by cold weapons armed infantry and cavalry charges outside of the wagon fort.

The first mobile use of war wagons and firearms took place during the Hussite breakthrough of Catholic encirclement at in November 1421 at the . The wagons and firearms were used on the move, at this point still only defensively. Žižka avoided the main camp of the enemy and employed the moving wagon fort in order to cover his retreating troops.

The first true engagement where firearms played primary role happened a month later during the Battle of KutnĆ” Hora

The Battle of KutnĆ” Hora ( Kuttenberg) was an early battle and subsequent campaign in the Hussite Wars, fought on 21 December 1421 between German and Hungarian troops of the Holy Roman Empire and the Hussites, an early ecclesiastical reformist ...

. Žižka positioned his forces between the town of KutnĆ” Hora that pledged alliegance to the Hussite cause and the main camp of the enemy, leaving supplies in the well defended town. However uprising of ethnic German townsmen led the town into Crusader's control.

In late night between 21 and 22 December 1421, Žižka ordered an attack against the enemy's main camp. The attack was conducted by using a gradually moving wagon wall. Instead of the usual infantry raids beyond the wagons, the attack relied mainly on use of ranged weapons from the moving wagons. Nighttime use of firearms proved extremely effective, not only practically but also psychologically.

1421 marked not only a shift in the importance of firearms, from auxiliary to primary weapons of Hussite militia, but also the establishment of the ÄĆ”slav diet of formal legal duty for all inhabitants to obey call to arms of the elected provisional Government. For the first time in medieval European history, this was not put in place in order to fulfill duties to a feudal lord or to the church, but in order to participate in the defense of the country.

Firearms design underwent fast development during the hussite wars and their civilian possession became a matter of course throughout the war as well as after its end in 1434. The word used for one type of hand held firearm used by the Hussites, cz, pĆŔńala, later found its way through German and French into English as the term pistol

A pistol is a handgun, more specifically one with the chamber integral to its gun barrel, though in common usage the two terms are often used interchangeably. The English word was introduced in , when early handguns were produced in Europe, a ...

. Name of a cannon used by the Hussites, the cz, houfnice, gave rise to the English term, "howitzer

A howitzer () is a long- ranged weapon, falling between a cannon (also known as an artillery gun in the United States), which fires shells at flat trajectories, and a mortar, which fires at high angles of ascent and descent. Howitzers, like ot ...

" (''houf'' meaning ''crowd'' for its intended use of shooting stone and iron shots against mass enemy forces). Other types of firearms commonly used by the Hussites included , an infantry weapon heavier than pĆŔńala, and yet heavier ''tarasnice'' ( fauconneau). As regards cannons, apart from houfnice Hussites employed ''bombarda'' ( mortar) and ''dÄlo'' (cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

).

First anti-Hussite crusade

After the death of his childless brother Wenceslaus, Sigismund inherited a claim on the Bohemian crown, though it was then, and remained till much later, in question whether Bohemia was a hereditary or an elective monarchy, especially as the line through which Sigismund claimed the throne had accepted that the Kingdom of Bohemia was an elective monarchy elected by the nobles, and thus the regent of the kingdom (ÄenÄk of Wartenberg) also explicitly stated that Sigismund had not been elected as reason for Sigismund's claim to not be accepted. A firm adherent of the Church of Rome, Sigismund was aided by

After the death of his childless brother Wenceslaus, Sigismund inherited a claim on the Bohemian crown, though it was then, and remained till much later, in question whether Bohemia was a hereditary or an elective monarchy, especially as the line through which Sigismund claimed the throne had accepted that the Kingdom of Bohemia was an elective monarchy elected by the nobles, and thus the regent of the kingdom (ÄenÄk of Wartenberg) also explicitly stated that Sigismund had not been elected as reason for Sigismund's claim to not be accepted. A firm adherent of the Church of Rome, Sigismund was aided by Pope Martin V

Pope Martin V ( la, Martinus V; it, Martino V; January/February 1369 ā 20 February 1431), born Otto (or Oddone) Colonna, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 11 November 1417 to his death in February 1431. Hi ...

, who issued a bull on 17 March 1420 proclaiming a crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

"for the destruction of the Wycliffites, Hussites and all other heretic

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important relig ...

s in Bohemia". Sigismund and many German princes arrived before Prague on 30 June at the head of a vast army of crusaders from all parts of Europe, largely consisting of adventurers attracted by the hope of pillage. They immediately began a siege of the city, which had, however, soon to be abandoned. Negotiations took place for a settlement of the religious differences.

The united Hussites formulated their demands in a statement known as the "Four Articles of Prague

The Hussites ( cs, HusitĆ© or ''KaliÅ”nĆci''; "Chalice People") were a Czech proto-Protestant Christian movement that followed the teachings of reformer Jan Hus, who became the best known representative of the Bohemian Reformation.

The Hussi ...

". This document, the most important of the Hussite period, ran, in the wording of the contemporary chronicler, Laurence of Brezova, as follows:

These articles, which contain the essence of the Hussite doctrine, were rejected by King Sigismund, mainly through the influence of the

These articles, which contain the essence of the Hussite doctrine, were rejected by King Sigismund, mainly through the influence of the papal legate

300px, A woodcut showing Henry II of England greeting the pope's legate.

A papal legate or apostolic legate (from the ancient Roman title '' legatus'') is a personal representative of the pope to foreign nations, or to some part of the Catholic ...

s, who considered them prejudicial to the authority of the pope. Hostilities therefore continued. However Sigismund was defeated at the Battle of VĆtkov Hill on July 1420.

Though Sigismund had retired from Prague, his troops held the castles of VyŔehrad

VyŔehrad ( Czech for "upper castle") is a historic fort in Prague, Czech Republic, just over 3 km southeast of Prague Castle, on the east bank of the Vltava River. It was probably built in the 10th century. Inside the fort are the Basil ...

and HradÄany

HradÄany (; german: Hradschin), the Castle District, is the district of the city of Prague, Czech Republic surrounding Prague Castle.

The castle is one of the biggest in the world at about in length and an average of about wide. Its histo ...

. The citizens of Prague laid siege to VyŔehrad (see Battle of VyŔehrad

The Battle of VyŔehrad was a series of engagements at the start of the Hussite War between Hussite forces and Catholic crusaders sent by Emperor Sigismund. The battle took place at the castle of VyŔehrad from 16 August 1419 to c. 1 November 142 ...

), and towards the end of October (1420) the garrison was on the point of capitulating through famine. Sigismund tried to relieve the fortress but was decisively defeated by the Hussites on 1 November near the village of PankrĆ”c. The castles of VyÅ”ehrad and HradÄany now capitulated, and shortly afterwards almost all Bohemia fell into the hands of the Hussites.

Second anti-Hussite crusade

Internal troubles prevented the followers of Hus from fully capitalizing on their victory. At Prague a demagogue, the priestJan ŽelivskĆ½

Jan ŽelivskĆ½ (1380 in Humpolec ā 9 March 1422 in Prague) was a prominent Czech priest during the Hussite Reformation.

Life

ŽelivskĆ½ preached at Church of Saint Mary Major. He was one of a few Utraquist

Utraquism (from the Latin ''sub u ...

, for a time obtained almost unlimited authority over the lower classes of the townsmen; and at TƔbor a religious communistic movement (that of the so-called Adamites

The Adamites, or Adamians, were adherents of an Early Christian group in North Africa in the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th centuries. They wore no clothing during their religious services. There were later reports of similar sects in Central Europe during ...

) was sternly suppressed by Žižka. Shortly afterwards a new crusade against the Hussites was undertaken. A large German army entered Bohemia and in August 1421 laid siege to the town of Žatec

Žatec (; german: Saaz) is a town in Louny District in the ĆstĆ nad Labem Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 19,000 inhabitants. It lies on the OhÅe river. The town centre is well preserved and is protected by law as an urban monumen ...

. After an unsuccessful attempt of storming the city, the crusaders retreated somewhat ingloriously on hearing that the Hussite troops were approaching. Sigismund only arrived in Bohemia at the end of 1421. He took possession of the town of KutnĆ” Hora

KutnƔ Hora (; medieval Czech: ''Hory KutnƩ''; german: Kuttenberg) is a town in the Central Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 20,000 inhabitants. The centre of KutnƔ Hora, including the Sedlec Abbey and its ossuary, was design ...

but was decisively defeated by Jan Žižka at the Battle of Deutschbrod

The Battle of Deutschbrod''Encyclopedia Americana'' or NÄmeckĆ½ Brod took place on 10 January 1422, in Deutschbrod (NÄmeckĆ½ Brod, now HavlĆÄkÅÆv Brod), Bohemia, during the Hussite Wars. Led by Jan Žižka, the Hussites

The Hussites ( cs, ...

(NÄmeckĆ½ Brod) on 6 January 1422.

Bohemian civil war

Bohemia was for a time free from foreign intervention, but internal discord again broke out, caused partly by theological strife and partly by the ambition of agitators. On 9 March 1422, Jan ŽelivskĆ½ was arrested by the town council of Prague and beheaded. There were troubles at TĆ”bor also, where a more radical party opposed Žižka's authority.

Bohemia was for a time free from foreign intervention, but internal discord again broke out, caused partly by theological strife and partly by the ambition of agitators. On 9 March 1422, Jan ŽelivskĆ½ was arrested by the town council of Prague and beheaded. There were troubles at TĆ”bor also, where a more radical party opposed Žižka's authority.

Polish and Lithuanian involvement

The Hussites were aided at various times byPoland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

. Because of this, Jan Žižka arranged for the crown of Bohemia to be offered to King WÅadysÅaw II JagieÅÅo

Jogaila (; 1 June 1434), later WÅadysÅaw II JagieÅÅo ()He is known under a number of names: lt, Jogaila Algirdaitis; pl, WÅadysÅaw II JagieÅÅo; be, JahajÅa (ŠÆŠ³Š°Š¹Š»Š°). See also: Names and titles of WÅadysÅaw II JagieÅÅo. ...

of Poland, who, under pressure from his own advisors, refused it. The crown was then offered to WÅadysÅaw's cousin, Vytautas

Vytautas (c. 135027 October 1430), also known as Vytautas the Great ( Lithuanian: ', be, ŠŃŃŠ°ŃŃ, ''VitaÅt'', pl, Witold Kiejstutowicz, ''Witold Aleksander'' or ''Witold Wielki'' Ruthenian: ''Vitovt'', Latin: ''Alexander Vitoldus'', O ...

, the Grand Duke of Lithuania

The monarchy of Lithuania concerned the monarchical head of state of Lithuania, which was established as an absolute and hereditary monarchy. Throughout Lithuania's history there were three ducal dynasties that managed to stay in powerā Ho ...

. Vytautas accepted it, with the condition that the Hussites reunite with the Catholic Church. In 1422, Žižka accepted Prince Sigismund Korybut

Sigismund Korybut ( lt, Žygimantas Kaributaitis; be, ŠŃŠ³ŃŠ¼Š¾Š½Ń ŠŠ°ŃŃŠ±ŃŃŠ°Š²ŃŃ; pl, Zygmunt Korybutowicz; cz, Zikmund KorybutoviÄ; uk, ŠŠøŅŠøŠ¼Š¾Š½Ń ŠŠ¾ŃŠøŠ±ŃŃŠ¾Š²ŠøŃ or Š”ŠøŠ³ŃŠ·Š¼ŃŠ½Š“ ŠŠ¾ŃŠøŠ±ŃŃŠ¾Š²ŠøŃ, 1395 ā ...

of Lithuania (nephew of WÅadysÅaw II) as regent of Bohemia for Vytautas.

His authority was recognized by the Utraquist nobles, the citizens of Prague, and the more moderate of the Taborites, but he failed to bring the Hussites back into the church. On a few occasions, he fought against both the Taborites and the Orebites to try to force them into reuniting. After WÅadysÅaw II and Vytautas signed the Treaty of Melno

The Treaty of Melno ( lt, Melno taika; pl, PokĆ³j melneÅski) or Treaty of Lake Melno (german: Friede von Melnosee) was a peace treaty ending the Gollub War. It was signed on 27 September 1422, between the Teutonic Knights and an alliance of th ...

with Sigismund of Hungary in 1423, they recalled Sigismund Korybut to Lithuania, under pressure from Sigismund of Hungary and the pope.

On his departure, civil war broke out, the Taborites opposing in arms the more moderate Utraquists, who at this period are also called by the chroniclers the "Praguers", as Prague was their principal stronghold. On 27 April 1423, Žižka now again leading, the Taborites defeated the Utraquist army under ÄenÄk of Wartenberg at the Battle of HoÅice

The Battle of HoÅice (German name: ''Horschitz'') was fought on April 27, 1423, between the Orebites faction of the Hussites and Bohemian Catholics. The Hussites were led by Jan Žižka (who was completely blind at the time of the battle), whil ...

; shortly afterwards an armistice was concluded at Konopilt.

Third anti-Hussite crusade

Papal influence had succeeded in calling forth a new crusade against Bohemia, but it resulted in complete failure. In spite of the endeavours of their rulers, Poles and Lithuanians did not wish to attack the kindred Czechs; the Germans were prevented by internal discord from taking joint action against the Hussites; and King Eric VII of Denmark, who had landed in Germany with a large force intending to take part in the crusade, soon returned to his own country. Free for a time from foreign threat, the Hussites invaded Moravia, where a large part of the population favored their creed; but, paralysed again by dissensions, they soon returned to Bohemia.

The city of

Papal influence had succeeded in calling forth a new crusade against Bohemia, but it resulted in complete failure. In spite of the endeavours of their rulers, Poles and Lithuanians did not wish to attack the kindred Czechs; the Germans were prevented by internal discord from taking joint action against the Hussites; and King Eric VII of Denmark, who had landed in Germany with a large force intending to take part in the crusade, soon returned to his own country. Free for a time from foreign threat, the Hussites invaded Moravia, where a large part of the population favored their creed; but, paralysed again by dissensions, they soon returned to Bohemia.

The city of Hradec KrƔlovƩ

Hradec KrƔlovƩ (; german: KƶniggrƤtz) is a city of the Czech Republic. It has about 91,000 inhabitants. It is the capital of the Hradec KrƔlovƩ Region. The historic centre of Hradec KrƔlovƩ is well preserved and is protected by law as an ...

, which had been under Utraquist rule, espoused the doctrine of TĆ”bor, and called Žižka to its aid. After several military successes gained by Žižka in 1423 and the following year, a treaty of peace between the Hussite factions was concluded on 13 September 1424 at LibeÅ, a village near Prague (now part of that city).

Sigismund Korybut, who had returned to Bohemia in 1424 with 1,500 troops, helped broker this peace. After Žižka's death in October 1424, Prokop the Great took command of the Taborites. Korybut, who had come in defiance of WÅadysÅaw II and Vytautas, also became a Hussite leader.

Fourth anti-Hussite crusade

In 1426, the Hussites were attacked again by foreign enemies. In June 1426 Hussite forces, led by Prokop and Sigismund Korybut, significantly defeated the invaders in the

In 1426, the Hussites were attacked again by foreign enemies. In June 1426 Hussite forces, led by Prokop and Sigismund Korybut, significantly defeated the invaders in the Battle of Aussig

The Battle of Aussig (german: Schlacht bei Aussig) or Battle of ĆstĆ nad Labem ( cs, Bitva u ĆstĆ nad Labem) was fought on 16 June 1426, between Roman Catholic crusaders and the Hussites during the Fourth Crusade of the Hussite Wars. It was ...

.

Despite this result, the death of Jan Žižka caused many, including Pope Martin V, to believe that the Hussites were much weakened. Martin proclaimed yet another crusade in 1427. He appointed Cardinal Henry Beaufort

Cardinal Henry Beaufort (c. 1375 ā 11 April 1447), Bishop of Winchester, was an English prelate and statesman who held the offices of Bishop of Lincoln (1398) then Bishop of Winchester (1404) and was from 1426 a Cardinal of the Church of R ...

of England as the papal legate of Germany, Hungary, and Bohemia, to lead the crusader forces. The crusaders were defeated at the Battle of Tachov

The Battle of Tachov (german: Schlacht bei Tachau) or Battle of Mies (german: Schlacht bei Mies) was a battle fought on 4 August 1427 near the Bohemian towns of Tachov (''Tachau'') and StÅĆbro (''Mies''). The Hussites won over the armies led by ...

.

The Hussites invaded parts of Germany several times, but they made no attempt to occupy permanently any part of the country.

Korybut was imprisoned in 1427 for allegedly conspiring to surrender the Hussite forces to Sigismund of Hungary. He was released in 1428, and participated in the Hussite invasion of Silesia.

After a few years, Korybut returned to Poland with his men. Korybut and his Poles did not really want to leave, but the pope threatened to call a crusade against Poland if they did not.

Glorious rides (ChevauchƩe)

During the Hussite Wars, the Hussites launched raids against many bordering countries. The Hussites called them ''SpanilĆ© jĆzdy'' ("glorious rides"). Especially under the leadership of Prokop the Great, Hussites invaded

During the Hussite Wars, the Hussites launched raids against many bordering countries. The Hussites called them ''SpanilĆ© jĆzdy'' ("glorious rides"). Especially under the leadership of Prokop the Great, Hussites invaded Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. S ...

, Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a ...

, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, MagyarorszƔg ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Cr ...

, Lusatia

Lusatia (german: Lausitz, pl, Åużyce, hsb, Åužica, dsb, Åužyca, cs, Lužice, la, Lusatia, rarely also referred to as Sorbia) is a historical region in Central Europe, split between Germany and Poland. Lusatia stretches from the BĆ³br ...

, and Meissen

Meissen (in German orthography: ''MeiĆen'', ) is a town of approximately 30,000 about northwest of Dresden on both banks of the Elbe river in the Free State of Saxony, in eastern Germany. Meissen is the home of Meissen porcelain, the Albre ...

. These raids were against countries that had supplied the Germans with men during the anti-Hussite crusades, to deter further participation. However, the raids did not have the desired effect; these countries kept supplying soldiers for the crusades against the Hussites.

During a war between Poland and the Teutonic Order, some Hussite troops helped the Poles. In 1433, a Hussite army of 7,000 men marched through Neumark into Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

and captured Dirschau

Tczew (, csb, DĆ«rszewĆ²; formerly ) is a city on the Vistula River in Eastern Pomerania, Kociewie, northern Poland with 59,111 inhabitants (December 2021). The city is known for its Old Town and the Vistula Bridge, or Bridge of Tczew, which pl ...

on the Vistula River

The Vistula (; pl, WisÅa, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania GĆ³ra in ...

. They eventually reached the mouth of the Vistula where it enters the Baltic Sea near Danzig. There, they performed a great victory celebration to show that nothing but the ocean could stop the Hussites. The Prussian historian Heinrich von Treitschke later wrote that they had "greeted the sea with a wild Czech song about God's warriors, and filled their water bottles with brine in token that the Baltic once more obeyed the Slavs."

Peace talks

The almost uninterrupted series of victories of the Hussites now rendered vain all hope of subduing them by force of arms. Moreover, the conspicuously democratic character of the Hussite movement caused the German princes, who were afraid that such ideas might spread to their own countries, to desire peace. Many Hussites, particularly the Utraquist clergy, were also in favour of peace. Negotiations for this purpose were to take place at the ecumenicalCouncil of Basel

The Council of Florence is the seventeenth ecumenical council recognized by the Catholic Church, held between 1431 and 1449. It was convoked as the Council of Basel by Pope Martin V shortly before his death in February 1431 and took place in ...

which had been summoned to meet on 3 March 1431. The Roman See reluctantly consented to the presence of heretics at this council, but indignantly rejected the suggestion of the Hussites that members of the Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops via ...

, and representatives of all Christian creeds, should also be present. Before definitely giving its consent to peace negotiations, the Roman Church determined on making a last effort to reduce the Hussites to subjection; this resulted in the fifth Crusade against the Hussites.

Fifth anti-Hussite crusade

On 1 August 1431, a large army of crusaders under Frederick I, Elector of Brandenburg, accompanied by Cardinal Cesarini as

On 1 August 1431, a large army of crusaders under Frederick I, Elector of Brandenburg, accompanied by Cardinal Cesarini as papal legate

300px, A woodcut showing Henry II of England greeting the pope's legate.

A papal legate or apostolic legate (from the ancient Roman title '' legatus'') is a personal representative of the pope to foreign nations, or to some part of the Catholic ...

, crossed the Bohemian border. On 8 August the crusaders reached the town of Domažlice

Domažlice (; german: Taus) is a town in the PlzeŠRegion of the Czech Republic. It has about 11,000 inhabitants. The historic town centre is well preserved and is protected by law as an urban monument reservation.

Administrative parts

The tow ...

and began besieging it. On 14 August, a Hussite relief army arrived, reinforced with some 6,000 Polish Hussites and under the command of Prokop the Great, and it completely routed the crusaders at the resulting Battle of Domažlice. According to legend, upon seeing the Hussite banners and hearing their battle hymn "Ktož jsĆŗ boÅ¾Ć bojovnĆci

"Ye Who Are Warriors of God", the English translation of "Ktož jsĆŗ BoÅ¾Ć bojovnĆci" from Old Czech, is a 15th-century Hussite war song. Alternate modern Czech spellings of the title are: "Kdož jsou BoÅ¾Ć bojovnĆci" and "Kdo jsou BoÅ¾Ć bo ...

" ("Ye Who are Warriors of God"), the invading papal forces immediately took to flight.

New negotiations and the defeat of Radical Hussites

On 15 October 1431, the Council of Basel issued a formal invitation to the Hussites to take part in its deliberations. Prolonged negotiations ensued, but a Hussite embassy, led by Prokop and including John of Rokycan, the Taborite bishop Nicolas of PelhÅimov, the "English Hussite" Peter Payne and many others, arrived at Basel on 4 January 1433. No agreement could be reached, but negotiations were not broken off, and a change in the political situation of Bohemia finally resulted in a settlement.

In 1434, war again broke out between the Utraquists and the Taborites. On 30 May 1434, the Taborite army, led by Prokop the Great and Prokop the Lesser, who both fell in the battle, was totally defeated and almost annihilated at the Battle of Lipany.

The Polish Hussite movement also came to an end. Polish royal troops under

On 15 October 1431, the Council of Basel issued a formal invitation to the Hussites to take part in its deliberations. Prolonged negotiations ensued, but a Hussite embassy, led by Prokop and including John of Rokycan, the Taborite bishop Nicolas of PelhÅimov, the "English Hussite" Peter Payne and many others, arrived at Basel on 4 January 1433. No agreement could be reached, but negotiations were not broken off, and a change in the political situation of Bohemia finally resulted in a settlement.

In 1434, war again broke out between the Utraquists and the Taborites. On 30 May 1434, the Taborite army, led by Prokop the Great and Prokop the Lesser, who both fell in the battle, was totally defeated and almost annihilated at the Battle of Lipany.

The Polish Hussite movement also came to an end. Polish royal troops under WÅadysÅaw III of Varna WÅadysÅaw is a Polish given male name, cognate with Vladislav. The feminine form is WÅadysÅawa, archaic forms are WÅodzisÅaw (male) and WÅodzisÅawa (female), and Wladislaw is a variation. These names may refer to:

Famous people Mononym

* W ...

defeated the Hussites at the Battle of Grotniki in 1439, bringing the Hussite Wars to an end.

Peace agreement

The moderate party thus obtained the upper hand and wanted to find a compromise between the council and the Hussites. It formulated its demands in a document which was accepted by the Church of Rome in a slightly modified form, and which is known as "the compacts". The compacts, mainly founded on the articles of Prague, declare that: # The Holy Sacrament is to be given freely in both kinds to all Christians in Bohemia and Moravia, and to those elsewhere who adhere to the faith of these two countries. # All mortal sins shall be punished and extirpated by those whose office it is so to do. # The word of God is to be freely and truthfully preached by the priests of the Lord, and by worthy deacons. # The priests in the time of the law of grace shall claim no ownership of worldly possessions. On 5 July 1436, the compacts were formally accepted and signed atJihlava

Jihlava (; german: Iglau) is a city in the Czech Republic. It has about 50,000 inhabitants. Jihlava is the capital of the VysoÄina Region, situated on the Jihlava River on the historical border between Moravia and Bohemia.

Historically, Jihlava ...

(Iglau), in Moravia, by King Sigismund, by the Hussite delegates, and by the representatives of the Roman Catholic Church. The latter, however, refused to recognize John of Rokycan as archbishop of Prague, who had been elected to that dignity by the estates of Bohemia.

Aftermath

The Utraquist creed, frequently varying in its details, continued to be that of the established church of Bohemia until all non-Catholic religious services were prohibited shortly after the

The Utraquist creed, frequently varying in its details, continued to be that of the established church of Bohemia until all non-Catholic religious services were prohibited shortly after the Battle of the White Mountain

The Battle of White Mountain ( cz, Bitva na BĆlĆ© hoÅe; german: Schlacht am WeiĆen Berg) was an important battle in the early stages of the Thirty Years' War. It led to the defeat of the Bohemian Revolt and ensured Habsburg control for the n ...

in 1620. The Taborite party never recovered from its defeat at Lipany, and after the town of TĆ”bor had been captured by George of PodÄbrady

George of KunÅ”tĆ”t and PodÄbrady (23 April 1420 ā 22 March 1471), also known as PodÄbrad or Podiebrad ( cs, JiÅĆ z PodÄbrad; german: Georg von Podiebrad), was the sixteenth King of Bohemia, who ruled in 1458ā1471. He was a leader of the ...

in 1452, Utraquist religious worship was established there. The Moravian Brethren (''Unitas Fratrum'') - whose intellectual originator was Petr ChelÄickĆ½ but whose actual founders were Brother Gregory, a nephew of Archbishop Rokycany, and Michael, curate of Žamberk ā to a certain extent continued the Taborite traditions, and in the 15th and 16th centuries included most of the strongest opponents of Rome in Bohemia.

John Amos Comenius, a member of the Brethren, claimed for the members of his church that they were the genuine inheritors of the doctrines of Hus. After the beginning of the German Reformation, many Utraquists adopted to a large extent the doctrines of Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 ā 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

and of John Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

and, in 1567, obtained the repeal of the Compacts which no longer seemed sufficiently far-reaching. From the end of the 16th century the inheritors of the Hussite tradition in Bohemia were included in the more general name of "Protestants" borne by the adherents of the Reformation.

At the end of the Hussite Wars in 1431, the lands of Bohemia had been totally ravaged. According to some estimates, the population of the Czech lands, estimated at 2.80ā3.37 million around 1400, fell to 1.50ā1.85 million by 1526. The adjacent Bishopric of WĆ¼rzburg

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associat ...

in Germany was left in such bad shape after the Hussite Wars, that the impoverishment of the people was still evident in 1476. The poor conditions contributed directly to the peasant conspiracy that broke out that same year in WĆ¼rzburg.

In 1466, Pope Paul II

Pope Paul II ( la, Paulus II; it, Paolo II; 23 February 1417 ā 26 July 1471), born Pietro Barbo, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States

from 30 August 1464 to his death in July 1471. When his maternal uncle Eugene IV ...

excommunicated the Hussite king George of PodÄbrady and forbade all Catholics from continuing to serve him. In 1468, the Kingdom of Bohemia was invaded

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing con ...

by the king of Hungary, Matthias Corvinus

Matthias Corvinus, also called Matthias I ( hu, Hunyadi MĆ”tyĆ”s, ro, Matia/Matei Corvin, hr, Matija/MatijaÅ” Korvin, sk, Matej KorvĆn, cz, MatyĆ”Å” KorvĆn; ), was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1458 to 1490. After conducting several m ...

. Matthias invaded with the pretext of returning Bohemia to Catholicism. The Czech Catholic Estates elected Matthias King of Bohemia. Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, MƤhren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The ...

, Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. S ...

and Lusatia

Lusatia (german: Lausitz, pl, Åużyce, hsb, Åužica, dsb, Åužyca, cs, Lužice, la, Lusatia, rarely also referred to as Sorbia) is a historical region in Central Europe, split between Germany and Poland. Lusatia stretches from the BĆ³br ...

soon accepted his rule but Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Äechy ; ; hsb, ÄÄska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

proper remained faithful to George of PodÄbrady. The religious peace of KutnĆ” Hora of 1485 finished a long series of religious conflicts in the Czech lands and constituted a definitive end to the Hussite Wars.

In popular culture

' (2013), a manga series by , focuses on a girl named Å Ć”rka who joins the Hussite Wars after the deaths of her family.See also

* Bartholomaeus of Drahonice *German Peasants' War

The German Peasants' War, Great Peasants' War or Great Peasants' Revolt (german: Deutscher Bauernkrieg) was a widespread popular revolt in some German-speaking areas in Central Europe from 1524 to 1525. It failed because of intense oppositi ...

* Schmalkaldic War

The Schmalkaldic War (german: link=no, Schmalkaldischer Krieg) was the short period of violence from 1546 until 1547 between the forces of Emperor Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire (simultaneously King Charles I ...

* The Slav Epic

''The Slav Epic'' ( cs, SlovanskĆ” epopej) is a cycle of 20 large canvases painted by Czechs, Czech Art Nouveau painter Alphonse Mucha between 1910 and 1928. The cycle depicts the mythology and history of Czechs and other Slavic peoples. In 19 ...

(Painting: "The meeting at KÅĆžky: Sub utraque")

Notes

References

Further reading

* * *External links

*Joan of Arc's Letter to the Hussites

(23 March 1430) ā In 1430,

Joan of Arc

Joan of Arc (french: link=yes, Jeanne d'Arc, translit= an daŹk} ; 1412 ā 30 May 1431) is a patron saint of France, honored as a defender of the French nation for her role in the siege of OrlĆ©ans and her insistence on the coronat ...

dictated a letter threatening to lead a crusading army against the Hussites unless they returned to "the Catholic Faith and the original Light". This link contains a translation of the letter plus notes and commentary.

Tactics of the Hussite Wars

Jan Hus and the Hussite Wars

o

Medieval Archives Podcast

{{Authority control 15th-century crusades European wars of religion Wars involving the Teutonic Order