Hubert Humphrey 1968 presidential campaign on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 1968 presidential campaign of Hubert Humphrey began when

The 1968 presidential campaign of Hubert Humphrey began when

Hubert Humphrey was first elected to public office in 1945 as

Hubert Humphrey was first elected to public office in 1945 as

Johnson assigned Humphrey the task of campaigning for re-election. In this role, the

Johnson assigned Humphrey the task of campaigning for re-election. In this role, the

On August 10, just two weeks prior to the convention opening, South Dakota Senator

On August 10, just two weeks prior to the convention opening, South Dakota Senator

On September 30, hoping to separate himself from the policies of the Johnson administration at the advice of O'Brien who noted that he needed the anti-war vote to win in New York and California, Humphrey delivered a televised speech in

On September 30, hoping to separate himself from the policies of the Johnson administration at the advice of O'Brien who noted that he needed the anti-war vote to win in New York and California, Humphrey delivered a televised speech in

On

On

After the defeat, Humphrey suffered from depression. To stay active, his friends helped him get hired as a professor at

After the defeat, Humphrey suffered from depression. To stay active, his friends helped him get hired as a professor at

What has Nixon done for you?

, Humphrey campaign advertisement

Shifting Nixon

advertisement

Nixon Peace Plan

advertisement {{DEFAULTSORT:Hubery Humphrey presidential campaign, 1968 Hubert Humphrey Humphrey, Hubert

Vice President of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest officer in the executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks first in the presidential line of succession. The vice p ...

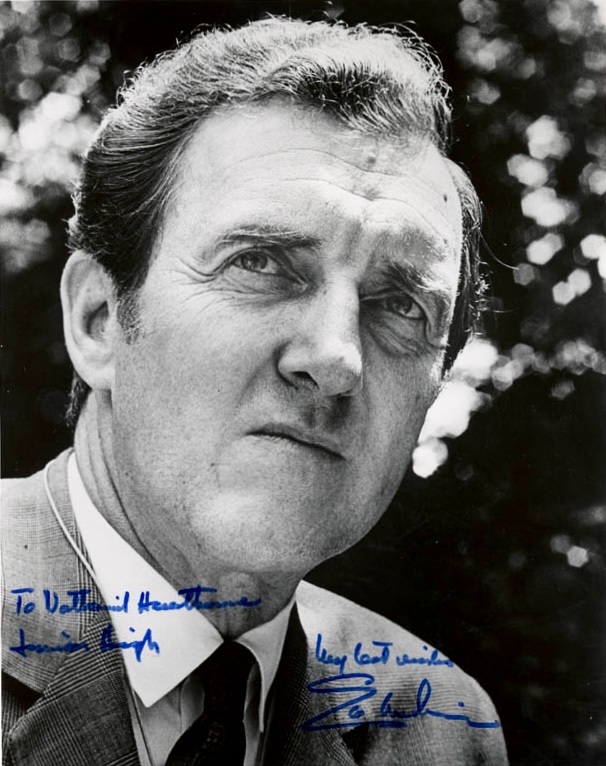

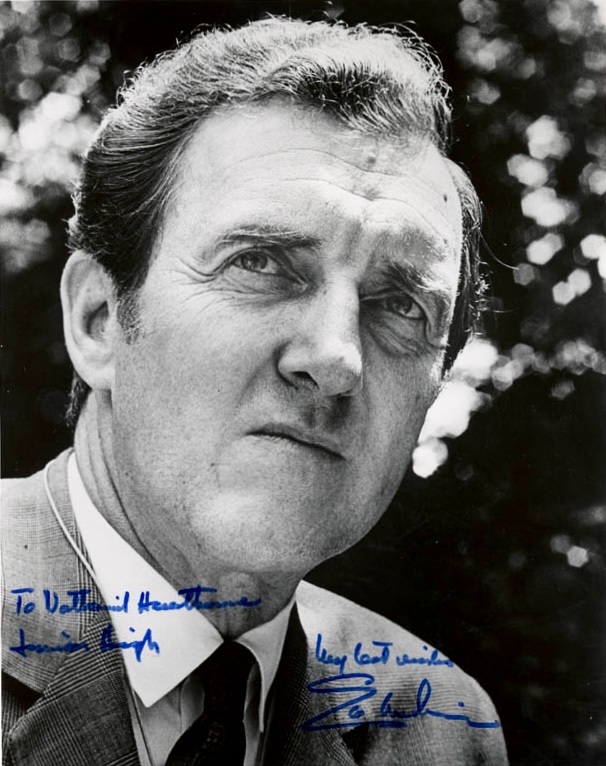

Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American pharmacist and politician who served as the 38th vice president of the United States from 1965 to 1969. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing ...

of Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over t ...

decided to seek the Democratic Party nomination for President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

following President Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

's announcement ending his own bid for the nomination. Johnson withdrew after an unexpectedly strong challenge from anti-Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

presidential candidate, Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

Eugene McCarthy

Eugene Joseph McCarthy (March 29, 1916December 10, 2005) was an American politician, writer, and academic from Minnesota. He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1949 to 1959 and the United States Senate from 1959 to 1971. ...

of Minnesota, in the early Democratic primaries. McCarthy, along with Senator Robert F. Kennedy of New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, became Humphrey's main opponents for the nomination. Their "new politics" contrasted with Humphrey's "old politics" as the increasingly unpopular Vietnam War intensified.

Humphrey entered the race too late to participate in the Democratic primaries. He relied on "favorite son

Favorite son (or favorite daughter) is a political term.

* At the quadrennial American national political party conventions, a state delegation sometimes nominates a candidate from the state, or less often from the state's region, who is not a ...

" candidates to win delegates and lobbied for endorsements from powerful bosses to obtain slates of delegates. The other candidates, who strove to win the nomination through popular support, criticized Humphrey's traditional approach. The June 1968 assassination of Robert Kennedy

On June 5, 1968, Robert F. Kennedy was shot by Sirhan Sirhan shortly after midnight at the Ambassador Hotel, Los Angeles. He was pronounced dead at 1:44 a.m. PDT the following day.

Kennedy was a senator from New York and a candidate in ...

left McCarthy as Humphrey's only major opponent. That changed at the 1968 Democratic National Convention

The 1968 Democratic National Convention was held August 26–29 at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Earlier that year incumbent President Lyndon B. Johnson had announced he would not seek reelection, thus maki ...

when Senator George McGovern

George Stanley McGovern (July 19, 1922 – October 21, 2012) was an American historian and South Dakota politician who was a U.S. representative and three-term U.S. senator, and the Democratic Party presidential nominee in the 1972 pr ...

of South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota and Dakota Sioux Native American tribes, who comprise a large po ...

entered the race as the successor of Kennedy. Humphrey won the party's nomination at the Convention on the first ballot, amid protests

A protest (also called a demonstration, remonstration or remonstrance) is a public expression of objection, disapproval or dissent towards an idea or action, typically a political one.

Protests can be thought of as acts of coopera ...

in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

. He selected little-known Senator Edmund Muskie

Edmund Sixtus Muskie (March 28, 1914March 26, 1996) was an American statesman and political leader who served as the 58th United States Secretary of State under President Jimmy Carter, a United States Senator from Maine from 1959 to 1980, the 6 ...

of Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and nor ...

as his running mate

A running mate is a person running together with another person on a joint ticket during an election. The term is most often used in reference to the person in the subordinate position (such as the vice presidential candidate running with a p ...

.

During the general election, Humphrey faced former Vice President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

of California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

, the Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

nominee, and Governor of Alabama

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who served as the 45th governor of Alabama for four terms. A member of the Democratic Party, he is best remembered for his staunch segregationist a ...

, the American Independent Party

The American Independent Party (AIP) is a far-right political party in the United States that was established in 1967. The AIP is best known for its nomination of former Democratic Governor George Wallace of Alabama, who carried five states in t ...

nominee. Nixon led in most polls throughout the campaign, and successfully criticized Humphrey's role in the Vietnam War, connecting him to the unpopular president and the general disorder in the nation. Humphrey experienced a surge in the polls in the days prior to the election, largely due to incremental progress in the peace process in Vietnam and a break with the Johnson war policy. On Election Day, Humphrey narrowly fell short of Nixon in the popular vote, but lost, by a large margin, in the Electoral College.

Background

Hubert Humphrey was first elected to public office in 1945 as

Hubert Humphrey was first elected to public office in 1945 as Mayor of Minneapolis

This is a list of mayors of Minneapolis, Minnesota. The current mayor is Jacob Frey (DFL).

Minneapolis

From 1867 to 1878 mayors were elected for a 1-year term. Beginning in 1878 the term was extended to 2 years.

As the city became larger and mo ...

. He served two, two-year terms, and gained a reputation as an anti-Communist and ardent supporter of the Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

. He gave a rousing speech at the 1948 Democratic National Convention

The 1948 Democratic National Convention was held at Philadelphia Convention Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from July 12 to July 14, 1948, and resulted in the nominations of President Harry S. Truman for a full term and Senator Alben W ...

arguing for the adoption of a pro-Civil Rights plank, exclaiming "The time has arrived in America for the Democratic Party to get out of the shadow of states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the ...

and to walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

." That same year, Minnesota voters elected him to the United States Senate, where he worked closely with Senate Majority Leader

The positions of majority leader and minority leader are held by two United States senators and members of the party leadership of the United States Senate. They serve as the chief spokespersons for their respective political parties holding t ...

Lyndon Johnson. Humphrey's persona and tactics in the Senate led colleagues to nickname him "The Happy Warrior". Contemporaries attributed his success in politics to his likable personality and ability to connect with voters on a personal level.

Humphrey first entered presidential politics in 1952

Events January–February

* January 26 – Black Saturday in Egypt: Rioters burn Cairo's central business district, targeting British and upper-class Egyptian businesses.

* February 6

** Princess Elizabeth, Duchess of Edinburgh, becomes m ...

, running as a favorite son candidate in Minnesota. In 1960

It is also known as the "Year of Africa" because of major events—particularly the independence of seventeen African nations—that focused global attention on the continent and intensified feelings of Pan-Africanism.

Events

January

* Ja ...

, he mounted a full-scale run, winning primaries in South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota and Dakota Sioux Native American tribes, who comprise a large po ...

and Washington D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, Na ...

; ultimately losing the Democratic nomination to Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

Senator and future President John F. Kennedy. In 1964

Events January

* January 1 – The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland is dissolved.

* January 5 - In the first meeting between leaders of the Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches since the fifteenth century, Pope Paul VI and Patriarc ...

, with Lyndon Johnson now as president following the assassination of Kennedy, Johnson tapped Humphrey as his running mate and went on to win in a landslide victory over Republican Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater (January 2, 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician and United States Air Force officer who was a five-term U.S. Senator from Arizona (1953–1965, 1969–1987) and the Republican Party nominee for president ...

. As vice president, Humphrey oversaw turbulent times in America, including race riots and growing frustration and anger over the large number of casualties in the Vietnam War. President Johnson's popularity plummeted as the election grew closer.

Lyndon Johnson campaign

Prior to Humphrey's run, President Lyndon Johnson began a campaign for re-election, placing his name in the first-in-the-nationNew Hampshire primary

The New Hampshire presidential primary is the first in a series of nationwide party primary elections and the second party contest (the first being the Iowa caucuses) held in the United States every four years as part of the process of choos ...

. Late in 1967, building upon anti-war sentiment, Senator Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota entered the race with heavy criticism of the President's Vietnam War policies. Even before McCarthy's entrance, Johnson grew concerned about a primary challenge. He confided to Democratic Congressional leaders that an opponent could draw the support of Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

and Dr. Benjamin Spock

Benjamin McLane Spock (May 2, 1903 – March 15, 1998) was an American pediatrician and left-wing political activist whose book '' Baby and Child Care'' (1946) is one of the best-selling books of the twentieth century, selling 500,000 copies ...

, defeating him in New Hampshire, and forcing his withdrawal from the race; similar to Senator Estes Kefauver

Carey Estes Kefauver (;

July 26, 1903 – August 10, 1963) was an American politician from Tennessee. A member of the Democratic Party, he served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1939 to 1949 and in the Senate from 1949 until his ...

's 1952 challenge to President Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

, which preceded Truman's decision not to seek re-election.

Johnson assigned Humphrey the task of campaigning for re-election. In this role, the

Johnson assigned Humphrey the task of campaigning for re-election. In this role, the Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. new ...

described him as the "administration's strongest advocate on Vietnam" policy. That task proved difficult following the Tet Offensive

The Tet Offensive was a major escalation and one of the largest military campaigns of the Vietnam War. It was launched on January 30, 1968 by forces of the Viet Cong (VC) and North Vietnamese People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) against the forces o ...

, which despite being a tactical victory, resulted in the deaths of thousands of American and South Vietnamese soldiers.Solberg, p. 319 The offensive included an invasion of the United States Embassy in Saigon, which changed the American public perception of North Vietnamese strength and the projected length of the war. Most Americans favored either an escalation in the number of American troops in Vietnam to overwhelm the enemy or a total withdrawal of American troops to prevent expending additional resources on the "hopeless task". McCarthy decried Johnson's handling of the war. He regarded "the Administration's reports of progress sthe products of their own self-deception". The Johnson campaign tried to negate the war's detractors before the New Hampshire primary. They circulated literature, warning voters "the communists in Vietnam are watching ... don't vote for fuzzy thinking and surrender". Despite opinion polls showing McCarthy's support around 10 to 20 percent in the state, in the primary itself McCarthy received 42.2 percent of the total vote, slightly below Johnson's 49.4 percent. Observers hailed the outcome as a "moral victory" for McCarthy. Senator Robert Kennedy of New York cited it as an inspiration to enter the race himself, despite previously announcing he would not challenge Johnson for the nomination. Humphrey tried to encourage the President to be more involved in the campaign, but he appeared disinterested. He delayed meetings with Indiana Governor Roger Branigin to arrange a favorite son "stand in" for the campaign; and despite Humphrey's insistence, Johnson neglected to hire the campaign's 1964 campaign manager Larry O'Brien

Lawrence Francis O'Brien Jr. (July 7, 1917September 28, 1990) was an American politician and basketball commissioner. He was one of the United States Democratic Party's leading electoral strategists for more than two decades. He served as Pos ...

. Humphrey did convince Johnson to speak to the influential National Farmers Union in Minneapolis, ahead of the Wisconsin Primary.

In late March, opinion polls suggested McCarthy would likely win the Wisconsin Primary. With defeat looming, Johnson decided to drop out of the race. When he informed Humphrey of his decision, Humphrey urged Johnson to reconsider. Johnson argued it betrayed the best interests of the nation to mix the partisan politics of a presidential election with the ongoing Vietnam crisis. Furthermore, Johnson said that if elected, he probably would not be able to complete the term since the men in his family usually died in their early sixties.Humphrey, p. 267 A week prior to the primary, on March 31, the President publicly announced he would not seek or accept the Democratic Party nomination, thus setting the stage for Humphrey's presidential run.

Announcement

After Johnson's withdrawal, Humphrey was hit with a barrage of media interest and fanfare. His aidesMax Kampelman

Max Kampelman (born Max Kampelmacher; November 7, 1920 – January 25, 2013) was an American diplomat.

Biography

Kampelman was born in New York, New York to Jewish Austrian immigrant parents on 7 November 1920. He grew up in the Bronx, New York ...

and Bill Connell began to set up an organization and held meetings with Humphrey and his advisors, encouraging him to start a campaign. Humphrey set up offices for preparation, and unsuccessfully courted Larry O'Brien as campaign manager. O'Brien explained that his loyalties lay with the Kennedy family

The Kennedy family is an American political family that has long been prominent in American politics, public service, entertainment, and business. In 1884, 35 years after the family's arrival from Ireland, Patrick Joseph "P. J." Kennedy beca ...

, leaving Humphrey undecided on whom to hire. Connell added lawyer and former DNC Treasurer Richard McGuire, who established the temporary campaign headquarters at his law firm. Eventually, Humphrey decided to embrace the youth of politics, adding Senators Fred R. Harris

Fred Roy Harris (born November 13, 1930) is an American academic, author, and former politician who served as a Democratic member of the United States Senate from Oklahoma.

Born in Walters, Oklahoma, Harris was elected to the Oklahoma Senate a ...

and Walter Mondale

Walter Frederick "Fritz" Mondale (January 5, 1928 – April 19, 2021) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 42nd vice president of the United States from 1977 to 1981 under President Jimmy Carter. A U.S. senator from Minnesota ...

, who agreed to lead the Democrats United for Humphrey organization. Harris was put in charge of winning delegates, and Mondale prepared for the convention, helping to keep an organization in place. Kampelman, Connell and McGuire questioned Humphrey's decision to hire the Senators, explaining that they had no organizational experience. Humphrey worried about his organization in the state of Iowa, but Harris and Mondale assured him that what would be lost in the state would be made up in Maryland.Solberg, p. 332 The campaign believed they could build a coalition of southern and border state Democrats as well as Union and Civil rights leaders to win the nomination. Mondale and Harris also desired to add a few anti-war liberals to the coalition. Meanwhile, Humphrey's office constantly received calls urging him to announce. Congressman Hale Boggs

Thomas Hale Boggs Sr. (February 15, 1914 – disappeared October 16, 1972; declared dead December 29, 1972) was an American Democratic politician and a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New Orleans, Louisiana. He was the House ma ...

and Senator Russell Long

Russell Billiu Long (November 3, 1918 – May 9, 2003) was an American Democratic politician and United States Senator from Louisiana from 1948 until 1987. Because of his seniority, he advanced to chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, servin ...

, both of Louisiana, warned Humphrey that if he did not declare his candidacy soon, Kennedy would secure the nomination.Solberg, p. 325 Labor leader George Meany

William George Meany (August 16, 1894 – January 10, 1980) was an American labor union leader for 57 years. He was the key figure in the creation of the AFL–CIO and served as the AFL–CIO's first president, from 1955 to 1979.

Meany, the son ...

also called for Humphrey to announce immediately, but when Humphrey explained that he did not want to rush into a campaign, Meany called President Johnson to demand that Humphrey announce. Johnson refused, and never explicitly asked Humphrey to run. Governors Harold Hughes

Harold Everett Hughes (February 10, 1922 – October 23, 1996) was the 36th Governor of Iowa from 1963 until 1969, and a United States senator from Iowa from 1969 until 1975. He began his political career as a Republican but changed his affi ...

of Iowa and Philip H. Hoff

Philip Henderson Hoff (June 29, 1924 – April 26, 2018) was an American politician from the U.S. state of Vermont. He was most notable for his service as the 73rd governor of Vermont from 1963 to 1969, the state's first Democratic governor si ...

of Vermont, each advised Humphrey to resign as vice president to separate himself from Johnson, but he declined. Before the official announcement, Humphrey met with Johnson and discussed the future. The President advised Humphrey that his biggest obstacle as a candidate would be money and organization, and that he must focus on the Midwest and Rust Belt

The Rust Belt is a region of the United States that experienced industrial decline starting in the 1950s. The U.S. manufacturing sector as a percentage of the U.S. GDP peaked in 1953 and has been in decline since, impacting certain regions an ...

states in order to win.

After weeks of speculation, Humphrey finally announced his candidacy on April 27, 1968, in front of a crowd of 1,700 supporters in Washington D.C. chanting "We Want Hubert". He delivered a twenty-minute speech, broadcast throughout the nation on television and radio that had been in preparation for four days after Johnson's withdrawal. Labor Secretary

The United States Secretary of Labor is a member of the Cabinet of the United States, and as the head of the United States Department of Labor, controls the department, and enforces and suggests laws involving Trade union, unions, the workplace ...

W. Willard Wirtz, White House staffers Harry McPherson and Charles Murphy, and journalists Norman Cousins

Norman Cousins (June 24, 1915 – November 30, 1990) was an American political journalist, author, professor, and world peace advocate.

Early life

Cousins was born to Jewish immigrant parents Samuel Cousins and Sarah Babushkin Cousins, in West ...

and Bill Moyers

Bill Moyers (born Billy Don Moyers, June 5, 1934) is an American journalist and political commentator. Under the Johnson administration he served from 1965 to 1967 as the eleventh White House Press Secretary. He was a director of the Counci ...

all contributed to the speech. In the speech, Humphrey proclaimed that the election would be about "common sense, and a time for maturity, strength and responsibility". He set his goals at not simply winning the nomination but winning in a way that would "unite heparty" so he could then "unite and govern henation". He argued that his campaign was "the way politics ought to be ... the politics of happiness, the politics of purpose, the politics of joy." His entrance occurred too late in the process to qualify for ballot access in the primaries.

Campaign developments

As the campaign got underway, Humphrey tried to position himself as theconservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

Democrat in the race, hoping to appeal to Southern delegates. Republicans, feeling that the Vice President might be the nominee, began to attack him, describing his positions as socialistic and reminding voters that Southern Democrats

Southern Democrats, historically sometimes known colloquially as Dixiecrats, are members of the U.S. Democratic Party who reside in the Southern United States. Southern Democrats were generally much more conservative than Northern Democrats wi ...

once considered him a "wild-eyed liberal". Democrats conceded this point but argued that compared to McCarthy and Kennedy, Humphrey was conservative. He immediately made an impact on the polls, rocketing to number one among Democrats in the beginning of May with 38%, ahead of both McCarthy and Kennedy.

An internal struggle within the campaign between the new politics of Mondale and Harris, and the old politics of Connell, Kampelman and Maguire, sometimes disrupted the organization of staffers in different states. Humphrey ordered Connell to not circumvent Mondale and Harris on campaign decisions, but the clashing continued throughout the campaign. The older faction referred to Mondale and Harris as "boy scouts".Solberg, p. 336

At the Indiana primary, Humphrey began the strategy of using "favorite son" candidates as surrogates for his campaign, and to weaken his opponents. Governor Roger Branigin stood in for Humphrey in Indiana, and placed second, in front of McCarthy but below Kennedy. Senator Stephen M. Young

Stephen Marvin Young (May 4, 1889December 1, 1984) was an American politician from the U.S. state of Ohio. A member

of the Democratic Party, he served as a United States Senator from Ohio from 1959 until 1971.

Life and career

Young was born o ...

of Ohio stood in for the Vice President in Ohio, and won the primary. He won his largest share of delegates during a six-week period after May 10, when the Vietnam War was briefly removed as a campaign issue due to the delicate peace talks with Hanoi. Later in May, he gained 57 delegates from Florida, as favorite son candidate Senator George Smathers defeated McCarthy in the Florida primary with 46% of the vote. Humphrey also picked up delegates from Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, following an endorsement from Philadelphia Mayor James Hugh Joseph Tate, and collected delegates from leaders in New York, Minnesota, Montana, Utah, Delaware and Connecticut. The other candidates criticized this tactic, and accused Humphrey of organizing a "bossed convention" against the wishes of the people.Solberg, p. 343

Frank Sinatra

Francis Albert Sinatra (; December 12, 1915 – May 14, 1998) was an American singer and actor. Nicknamed the " Chairman of the Board" and later called "Ol' Blue Eyes", Sinatra was one of the most popular entertainers of the 1940s, 1950s, and ...

performed at a fundraising rally for Humphrey's campaign at the Oakland Arena on 22 May.

The next month, Humphrey's rival Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world ...

, prompting the Vice-President to return to his home in Minnesota and "think about the next stage". Shaken by the event, Humphrey took off two weeks from campaigning. He met with President Johnson, and the two talked about "everything"Solberg, p. 341 during a three-hour meeting. The assassination all but guaranteed Humphrey the nomination. He commented that he "was doing everything I could to win the nomination ... but God knows I didn't want it that way."Solberg, p. 340 A large number of Kennedy delegates switched to Humphrey, but he lost money from Republican donors concerned about a Kennedy nomination, and popular opinion polls shifted in favor of Senator McCarthy. In fact, Humphrey was booed before 50,000 people on June 19 at the Lincoln Memorial

The Lincoln Memorial is a U.S. national memorial built to honor the 16th president of the United States, Abraham Lincoln. It is on the western end of the National Mall in Washington, D.C., across from the Washington Monument, and is in ...

as he was introduced at a Solidarity March for civil rights. Drew Pearson and Jack Anderson described the response as ironic, given that Humphrey was booed at the 1948 Democratic National Convention after advocating a civil rights plank. He tried to defend his record against the liberal detractors, but often encountered anti-war protesters and hostile crowds while campaigning. At the end of June, Republican Senator Mark Hatfield

Mark Odom Hatfield (July 12, 1922 – August 7, 2011) was an American politician and educator from the state of Oregon. A Republican, he served for 30 years as a United States senator from Oregon, and also as chairman of the Senate Approp ...

of Oregon assessed the race, arguing that Humphrey would be the party's nominee for president but criticized him for being too closely aligned with Johnson's policies. Humphrey asked for Johnson's permission to deviate from the administration's position on the war for a plan that included a bombing halt and drawback of forces,Van Dyk, p. 74 but Johnson refused, explaining that it would disrupt the peace process and endanger American soldiers. He relayed to Humphrey that the blood of his son-in-law who was serving in Vietnam, would be on his hands if he announced the new position.

In July, Humphrey criticized McCarthy for simply complaining about the war effort and offering no plan for peace. Afterwards, McCarthy challenged Humphrey to a series of debates on an assortment of issues including Vietnam. The Vice-President accepted the invitation but modified the proposal, requesting there be only one debate prior to the Democratic National Convention. However, the one-on-one debate never occurred, largely due to the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

invasion of Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, and the insistence of other candidates to participate. At the end of the month, Humphrey began to court Senator Edward Kennedy

Edward Moore Kennedy (February 22, 1932 – August 25, 2009) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a United States senator from Massachusetts for almost 47 years, from 1962 until his death in 2009. A member of the Democratic ...

of Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

, the younger brother of Robert Kennedy, as a possible running mate, hoping the Senator would increase his chances of winning the support of liberals, and alleviate the criticism spawned from his connections to Johnson. Kennedy declined. Humphrey also asked Larry O'Brien, who had been named as chairman of the Democratic National Committee

The Democratic National Committee (DNC) is the governing body of the United States Democratic Party. The committee coordinates strategy to support Democratic Party candidates throughout the country for local, state, and national office, as well ...

, to be his campaign manager. O'Brien privately believed that Humphrey could not win in the general election, but joined because he felt "sympathy for Humphrey and the problems he faced".Richardson, p. 403 He publicly predicted the race would come "down to the wire".

As former Vice President Richard Nixon gained the Republican Party nomination, Humphrey held what he thought was a private meeting with 23 college students in his office. There, he candidly discussed his thoughts about the political climate, unaware that reporters were also in the room and that his statements would become public. Humphrey remarked that youths were using the Vietnam War as "escapism" and ignoring domestic issues. He stated that he had received thousands of letters from young people about the Vietnam War but received zero about Head Start as part of the program designed for poor preschool children began to expire, which he saved with a tie-breaking Senate vote. As the national convention approached with Humphrey's likely nomination, the war continued to divide the party and set the stage for a battle in Chicago, Humphrey hoped to move the convention to Miami

Miami ( ), officially the City of Miami, known as "the 305", "The Magic City", and "Gateway to the Americas", is a coastal metropolis and the county seat of Miami-Dade County in South Florida, United States. With a population of 442,241 at ...

. At first a cover story for relocation was an unsettled communications workers strike. The truth was to escape a vitriolic venue. President Johnson vetoed the idea.

Democratic National Convention

On August 10, just two weeks prior to the convention opening, South Dakota Senator

On August 10, just two weeks prior to the convention opening, South Dakota Senator George McGovern

George Stanley McGovern (July 19, 1922 – October 21, 2012) was an American historian and South Dakota politician who was a U.S. representative and three-term U.S. senator, and the Democratic Party presidential nominee in the 1972 pr ...

entered the race, casting himself as the standard-bearer of the Robert Kennedy legacy. As the 1968 Democratic National Convention

The 1968 Democratic National Convention was held August 26–29 at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Earlier that year incumbent President Lyndon B. Johnson had announced he would not seek reelection, thus maki ...

started, Humphrey stated that he had more than enough delegates to secure the nomination, but commentators questioned the campaign's ability to hold on to the delegates. The Texas delegation announced frustration at the McCarthy campaign's attempts to change procedures, and declared that they might renominate President Johnson as a result. Observers noted that Humphrey's delegates were supporters of Johnson, and could follow suit. Meanwhile, protests and sleep-ins were held in the streets and parks

A park is an area of natural, semi-natural or planted space set aside for human enjoyment and recreation or for the protection of wildlife or natural habitats. Urban parks are green spaces set aside for recreation inside towns and cities. ...

of Chicago, forcing Mayor

In many countries, a mayor is the highest-ranking official in a municipal government such as that of a city or a town. Worldwide, there is a wide variance in local laws and customs regarding the powers and responsibilities of a mayor as well ...

Richard J. Daley to order federal troops into the city. Eventually, 6,000 federal troops and 18,000 Illinois National Guardsmen were outside the convention, defending the premises. A televised debate was held featuring Humphrey, McCarthy and McGovern. Humphrey hoped to unite the party during the debate, affirming his support for peace in Vietnam, but his challengers were received better by the crowd, drawing more applause.

Humphrey won the party's nomination on the first ballot after a two-hour debate among delegates the next day, defeating McCarthy 1759.25 to 601. McGovern finished in third with 146.5, and gave a lukewarm endorsement of Humphrey, asking him to be "his own man". McCarthy refused to make an endorsement, although he privately confided to Humphrey that his supporters would not understand if he immediately showed his support. Humphrey also narrowly won the party plank in support of the Vietnam War, although his officials pleaded with Johnson to accept a compromise with the doves, which he refused. The results caused the protests to intensify, prompting the use of tear gas

Tear gas, also known as a lachrymator agent or lachrymator (), sometimes colloquially known as "mace" after the early commercial aerosol, is a chemical weapon that stimulates the nerves of the lacrimal gland in the eye to produce tears. In ...

, which Humphrey could smell in his hotel room. He also received six death threats. The tactics used to quell the protests were criticized by certain Democrats as being excessive. During his acceptance speech, Humphrey tried to unify the party, stating "the policies of tomorrow need not be limited to the policies of yesterday." He asked former Republican candidate Nelson Rockefeller

Nelson Aldrich Rockefeller (July 8, 1908 – January 26, 1979), sometimes referred to by his nickname Rocky, was an American businessman and politician who served as the 41st vice president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. A member of t ...

to be his running mate, but he declined. Several other names were mentioned to Humphrey during the convention. Texas Governor John Connally

John Bowden Connally Jr. (February 27, 1917June 15, 1993) was an American politician. He served as the 39th governor of Texas and as the 61st United States secretary of the Treasury. He began his career as a Democrat and later became a Republic ...

was suggested by a delegation of southern Democratic governors, but the Governor himself suggested Vietnam ambassador Cyrus Vance

Cyrus Roberts Vance Sr. (March 27, 1917January 12, 2002) was an American lawyer and United States Secretary of State under President Jimmy Carter from 1977 to 1980. Prior to serving in that position, he was the United States Deputy Secretary o ...

. O'Brien and Fred Harris appeared to suggest themselves for the position, and adviser Connell also suggested Harris, although Max Kampelman favored former Peace Corps

The Peace Corps is an independent agency and program of the United States government that trains and deploys volunteers to provide international development assistance. It was established in March 1961 by an executive order of President John ...

director Sargent Shriver

Robert Sargent Shriver Jr. (November 9, 1915 – January 18, 2011) was an American diplomat, politician, and activist. As the husband of Eunice Kennedy Shriver, he was part of the Kennedy family. Shriver was the driving force behind the creatio ...

. Humphrey instead decided on senator and former governor Edmund Muskie of Maine, who had been his preferred choice. Observers noted the selection of the Senator, active in civil rights and labor and on neither side of the war issue, was a move to appeal to liberals while not upsetting establishment Democrats. Republican nominee Richard Nixon congratulated Humphrey on his victory as the general election campaign began.

General election

As the general election got underway, the largest hurdle for the campaign was finances. Polling numbers showed Humphrey trailing Nixon, causing donations to decrease. President Johnson refused to use the power of his office to help raise money, although many speculated that the tardiness of the Convention, scheduled to coincide with Johnson's birthday, contributed to the issue. To stay afloat, several loans were made, which eventually accounted for half of the $11.6 million used by Humphrey throughout the general election. Campaign workers decided that no money would be spent on radio or television advertising until the final three weeks of the election. In September, President Johnson showed his support for Humphrey by giving what was described as the strongest endorsement of the campaign when he asked Texas Democrats to throw their support behind the Vice President. However, Johnson did not give his official endorsement until an October 10 radio address. Meanwhile, Humphrey campaigned in New York where he labeled Nixon a "Hawk

Hawks are birds of prey of the family Accipitridae. They are widely distributed and are found on all continents except Antarctica.

* The subfamily Accipitrinae includes goshawks, sparrowhawks, sharp-shinned hawks and others. This subfa ...

", stating that the former Vice President "wanted to go to war (in Vietnam) in 1954". At a later stop in Buffalo, Humphrey was met by protesters.

Both campaigns began to use their running mates to attack the other candidate. Republican vice presidential nominee Spiro Agnew

Spiro Theodore Agnew (November 9, 1918 – September 17, 1996) was the 39th vice president of the United States, serving from 1969 until his resignation in 1973. He is the second vice president to resign the position, the other being John ...

criticized the current Vice President for being "soft on communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

" and "soft on inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reduct ...

and soft on law and order". He then compared the nominee to former British Prime Minister

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As moder ...

Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeaseme ...

. But Agnew often made gaffes on the campaign trail, in contrast to Muskie who was viewed as a natural campaigner. In Missouri, in preparation for a meeting with former President Harry Truman, Muskie tried to defend his running mate from connections made by the Nixon campaign to the Johnson administration. He reversed the accusation by claiming that Nixon should be held accountable for the shortcomings of the Eisenhower administration

Dwight D. Eisenhower's tenure as the 34th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1953, and ended on January 20, 1961. Eisenhower, a Republican from Kansas, took office following a landslide victory ...

, under his logic. He then lambasted the Republican ticket for ignoring such issues as urban renewal, housing, and federal aid for education and sewage. Muskie was renowned for his speaking ability, and was known to turn around hostile crowds including one well publicized event when he asked an anti-war protester to join him on the stage. Although he provided a small boost for the campaign, Nixon remained fifteen points ahead, 44% to 29% in the September 27 Gallup poll. Diplomat George W. Ball soon resigned his position in the Johnson administration to campaign for and advise Humphrey, hoping to prevent a Nixon victory. At the end of September, Humphrey's chances for the presidency further declined as media outlets observed that the Republican Party would be the likely winners in the election. Humphrey acknowledged his odds, proclaiming at an event in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

: "regardless of the outcome of this election, I want it to be said of Hubert Humphrey that at an important and tough moment of his life he stood up for what he believed and was not shouted down." The comment drew boos from the crowd. Individuals close to the campaign noted that Humphrey looked tired and worn-out while flying from stop to stop, but would brighten up when he encountered a crowd.

On September 30, hoping to separate himself from the policies of the Johnson administration at the advice of O'Brien who noted that he needed the anti-war vote to win in New York and California, Humphrey delivered a televised speech in

On September 30, hoping to separate himself from the policies of the Johnson administration at the advice of O'Brien who noted that he needed the anti-war vote to win in New York and California, Humphrey delivered a televised speech in Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City (often shortened to Salt Lake and abbreviated as SLC) is the capital and most populous city of Utah, United States. It is the seat of Salt Lake County, the most populous county in Utah. With a population of 200,133 in 2020, th ...

to a nationwide audience, and announced that if he was elected, he would put an end to the bombing of North Vietnam, and called for a ceasefire. He labeled the new policy "as an acceptable risk for peace". The plan was compared to Nixon's, which the candidate stated would not be revealed until Inauguration Day

The inauguration of the president of the United States is a ceremony to mark the commencement of a new four-year term of the president of the United States. During this ceremony, between 73 to 79 days after the presidential election, the pres ...

. After the speech, anti-war protesters stopped shadowing Humphrey's appearances, and a few McCarthy supporters joined the campaign. Donations totaling $300,000 were immediately made to Humphrey, and he also improved in the polls, cutting Nixon's lead to single digits by mid-October. Meanwhile, Nixon tried to shift the emphasis of the campaign to the issue of law and order

In modern politics, law and order is the approach focusing on harsher enforcement and penalties as ways to reduce crime. Penalties for perpetrators of disorder may include longer terms of imprisonment, mandatory sentencing, three-strikes laws a ...

, and declared that a vote for Humphrey, would amount to "a vote to continue a lackadaisical, do nothing attitude toward the crime crisis in America". While campaigning in San Antonio

("Cradle of Freedom")

, image_map =

, mapsize = 220px

, map_caption = Interactive map of San Antonio

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = United States

, subdivision_type1= State

, subdivision_name1 = Texas

, subdivision_ ...

, Humphrey went on the attack against Nixon. He accused the Republican nominee of playing politics with human rights, and claimed that he was "on the road to defeat". Hoping to gain favor among the Hispanic

The term ''Hispanic'' ( es, hispano) refers to people, cultures, or countries related to Spain, the Spanish language, or Hispanidad.

The term commonly applies to countries with a cultural and historical link to Spain and to viceroyalties for ...

community, Humphrey alleged that Nixon had never discussed the concerns of Hispanic-Americans during the course of the campaign. Nixon continued to tie Humphrey to Johnson. He argued that the administration was playing politics with the Vietnam War by trying to complete a treaty before the election to favor the Vice President. Humphrey fired back at Nixon's allegations, stating that the former vice president was using "the old Nixon tactic of unsubstantiated insinuation" and requested that he show evidence for his claims. Humphrey challenged Nixon to a series of presidential debates, but the Republican nominee declined, largely due to his uncomfortable experience at the 1960 presidential debates, and to deny recognition to the populist American Independent Party

The American Independent Party (AIP) is a far-right political party in the United States that was established in 1967. The AIP is best known for its nomination of former Democratic Governor George Wallace of Alabama, who carried five states in t ...

candidate, Governor George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who served as the 45th governor of Alabama for four terms. A member of the Democratic Party, he is best remembered for his staunch segregationist a ...

of Alabama, who would have been included at the event. Both the Humphrey and Nixon campaigns were concerned that Wallace would take a sizable number of states in the electoral college and force the House of Representatives to decide the election. Although Wallace had focused most of his campaign on the south, he was drawing large crowds during appearances in the north. Both campaigns delegated a large amount of resources to denounce Wallace as a "frustrated segregationist". As election day neared, Wallace fell in the polls, greatly diminishing the chance that he would influence the result.

A few days before the election, Humphrey gained the endorsement of his former rival Eugene McCarthy. During a stop in Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

, Humphrey stated that the endorsement made him a "happy man". The hopes of victory for Humphrey also began to look up as a bombing pause was achieved and that negotiations had progressed, cutting Nixon's 18 point lead to 2 points at the end of October. The Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

had tried to influence the North Vietnamese to soften on the negotiations to prevent a Nixon victory, but Nixon publicly accused President Johnson of speeding up the negotiations. Contemporary sources reveal that Nixon was personally involved in preventing the South Vietnamese from coming to the negotiation table, through the use of operative Anna Chennault

Anna Chennault, born Chan Sheng Mai, later spelled Chen Xiangmei (, actual birth year 1923, but reported as June 23, 1925 – March 30, 2018), also known as Anna Chan Chennault or Anna Chen Chennault, was a war correspondent and prominent Republ ...

who advised Saigon that a Nixon administration would offer them a better deal. Members of the campaign later claimed that Humphrey did not bring this up before the election, because he did not want to appear desperate while polls placed him even with Nixon. Humphrey held his final campaign rally at the Houston Astrodome

The NRG Astrodome, also known as the Houston Astrodome or simply the Astrodome, is the world's first multi-purpose, domed sports stadium, located in Houston, Texas. It was financed and assisted in development by Roy Hofheinz, mayor of Houston ...

on November 3 alongside President Johnson. Governor Connally did not attend the event, causing suspicion that he would back Nixon, but he later assured Humphrey that he would not do so. During his speech at the rally, Humphrey asked Americans to base their vote on hope rather than fear. The next day, the eve of the election, he appeared in Los Angeles with Muskie, and was greeted by 100,000 supporters.Richardson, p. 433 Later that day, Humphrey and Nixon each held four-hour televised forums from Los Angeles on rival television networks. Humphrey's on ABC-TV at 8:30pm EST, Nixon's on NBC-TV at 9pm EST. Humphrey, with Muskie by his side, fielded questions from a live studio audience and a phone bank of celebrities including Frank Sinatra

Francis Albert Sinatra (; December 12, 1915 – May 14, 1998) was an American singer and actor. Nicknamed the " Chairman of the Board" and later called "Ol' Blue Eyes", Sinatra was one of the most popular entertainers of the 1940s, 1950s, and ...

and Paul Newman

Paul Leonard Newman (January 26, 1925 – September 26, 2008) was an American actor, film director, race car driver, philanthropist, and entrepreneur. He was the recipient of numerous awards, including an Academy Award, a BAFTA Award, three ...

. The Nixon telecast featured no interaction with anyone other than sports personally Bud Wilkinson

Charles Burnham "Bud" Wilkinson (April 23, 1916 – February 9, 1994) was an American football player, coach, broadcaster, and politician. He served as the head football coach at the University of Oklahoma from 1947 to 1963, compiling a record of ...

who read queries from index cards beside rows of volunteers taking calls. Muskie, commenting on the Republican broadcast from their studios noted that Spiro Agnew was nowhere to be found and how it appeared to be staged. Nixon tried to reverse Humphrey's boost from the bombing halt by stating that he had been advised that "tons of supplies" were being sent along the Ho Chi Minh Trail by the North Vietnamese, a shipment that could not be stopped. Humphrey described these claims as "irresponsible", which prompted Nixon to proclaim that Humphrey "doesn't know what's going on". McCarthy called in during Humphrey's telethon and affirmed his support for the ticket. Edward Kennedy videotaped an endorsement for Humphrey from his home in Massachusetts.

Results

Election Day

Election day or polling day is the day on which general elections are held. In many countries, general elections are always held on a Saturday or Sunday, to enable as many voters as possible to participate; while in other countries elections ...

, Humphrey was defeated by Nixon 301 to 191 in the electoral college. Wallace received 46, all in the Deep South. The popular vote was much closer as Nixon edged Humphrey 43.42% to 42.72%, with a margin of approximately 500,000 votes. Humphrey carried his home state of Minnesota and Texas, the home state of President Johnson (as well as Maine, running-mate Ed Muskie's home state). He also won most of the Northeast and Michigan, but lost the West to Nixon and the South to Wallace. Humphrey conceded the race to Nixon, and stated that he would support him as president. On his way out he remarked: "I've done my best."

Post election polls showed that Humphrey lost the white vote with 38%, nine points behind Nixon, but won the nonwhite vote solidly, 85% to 12%, including 97% of African-Americans. African-Americans favored Humphrey because of his record on civil rights, and their desire to quickly end the war in Vietnam, where blacks were overrepresented. The racial divide in the election had widened since 1964, and was attributed to civil rights protests and race riots. Humphrey won 45% of the female vote, two points ahead of Nixon, but lost to the Republican among males, 41% to 43%. Voters with only a grade school education supported Humphrey 52% to 33% over Nixon, while Nixon won among both those with no higher education than high school (43% to 42%) and those who graduated from college (54% to 37%). Occupation demographics mirrored these numbers with manual-labor workers supporting Humphrey 50% to 37%, and with white-collar (47% to 41%) and professionals (56% to 34%) favoring Nixon. Humphrey won among young voters (under 30 years old) by 47% to 38%, and also edged Nixon among those between 30 and 49 years, with 44% to 41%. Nixon won among voters over 50 years, 47% to 41%. Catholics backed Humphrey with 59%, twelve points ahead of Nixon, but Protestants favored Nixon, 49% to 35%. Humphrey lost the Independent vote 31% to 44%, with 25% going to Wallace, and won a lower percentage among Democrats (74%) than Nixon won among Republicans (86%). This discrepancy was connected to the tough Democratic primary election that caused some former McCarthy, Kennedy or McGovern supporters to vote for Nixon or Wallace as a protest.

Aftermath

After the defeat, Humphrey suffered from depression. To stay active, his friends helped him get hired as a professor at

After the defeat, Humphrey suffered from depression. To stay active, his friends helped him get hired as a professor at Macalester College

Macalester College () is a private liberal arts college in Saint Paul, Minnesota. Founded in 1874, Macalester is exclusively an undergraduate four-year institution and enrolled 2,174 students in the fall of 2018 from 50 U.S. states, four U.S te ...

and the University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota, formally the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, (UMN Twin Cities, the U of M, or Minnesota) is a public land-grant research university in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States. ...

. He also wrote a syndicated column and was added to the board of directors for the ''Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various t ...

''. Augmented by paid speaking tours, he earned $200,000 in his first year of private life, the most he ever earned in a single year. He also remained loyal to the Democratic Party, and often attended party fundraising events. In 1970, Humphrey returned to politics and ran for the Senate seat vacated by Eugene McCarthy. During the campaign, he appeared refreshed. He had lost a dozen pounds and darkened his hair in preparation for the race, hoping to appear youthful. Humphrey easily won the election, and began his new term in 1971. He ran again for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1972

Within the context of Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) it was the longest year ever, as two leap seconds were added during this 366-day year, an event which has not since been repeated. (If its start and end are defined using mean solar tim ...

, and won the most votes during the primary campaign, but lost to George McGovern at the convention. McGovern went on to be defeated by President Nixon in a landslide. Humphrey was mentioned as a potential candidate for the 1976 presidential nomination, and an early poll placed him as the leading candidate by more than ten points. Draft efforts were organized to convince him to run, and although he did not formally announce his candidacy, he affirmed that if nominated, he would accept. Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he previously served as th ...

was nominated instead, and defeated Republican nominee Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. ( ; born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was an American politician who served as the 38th president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. He was the only president never to have been elected ...

. Carter ran with Walter Mondale and would later name Edmund Muskie as Secretary of State. After being diagnosed with bladder cancer

Bladder cancer is any of several types of cancer arising from the tissues of the urinary bladder. Symptoms include blood in the urine, pain with urination, and low back pain. It is caused when epithelial cells that line the bladder become ma ...

, Humphrey died on January 13, 1978 while still serving in the Senate. He called Richard Nixon prior to his death, and invited him to attend his funeral.Kalb, p. 20

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * *External links

What has Nixon done for you?

, Humphrey campaign advertisement

Shifting Nixon

advertisement

Nixon Peace Plan

advertisement {{DEFAULTSORT:Hubery Humphrey presidential campaign, 1968 Hubert Humphrey Humphrey, Hubert