Huaynaputina on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Huaynaputina ( ; ) is a

The oceanic Nazca tectonic plate is

The oceanic Nazca tectonic plate is

Ash fall from Huaynaputina reached a thickness of within a area of southern Peru, Bolivia and Chile, and of over closer to the volcano. The tephra was deposited in a major westerly lobe and a minor northerly lobe; this is an unusual distribution, as tephra from volcanoes in the Central Andes is usually carried eastward by winds. The deposition of the tephra was influenced by topography and wind changes during the eruption, which led to changes in the fallout pattern. The ash deposits from the eruption are visible to this day, and several

Ash fall from Huaynaputina reached a thickness of within a area of southern Peru, Bolivia and Chile, and of over closer to the volcano. The tephra was deposited in a major westerly lobe and a minor northerly lobe; this is an unusual distribution, as tephra from volcanoes in the Central Andes is usually carried eastward by winds. The deposition of the tephra was influenced by topography and wind changes during the eruption, which led to changes in the fallout pattern. The ash deposits from the eruption are visible to this day, and several

The eruption had a devastating impact on the region. Ash falls and pumice falls buried the surroundings beneath more than of rocks, while pyroclastic flows incinerated everything within their path, wiping out vegetation over a large area. Of the volcanic phenomena, the ash and pumice falls were the most destructive. These and the debris and pyroclastic flows devastated an area of about around Huaynaputina, and both crops and livestock sustained severe damage.

Between 11 and 17 villages within from the volcano were buried by the ash, including Calicanto, Chimpapampa, Cojraque, Estagagache, Moro Moro and San Juan de Dios south and southwest of Huaynaputina. The Huayruro Project began in 2015 and aims to rediscover these towns, and Calicanto was christened one of the 100

The eruption had a devastating impact on the region. Ash falls and pumice falls buried the surroundings beneath more than of rocks, while pyroclastic flows incinerated everything within their path, wiping out vegetation over a large area. Of the volcanic phenomena, the ash and pumice falls were the most destructive. These and the debris and pyroclastic flows devastated an area of about around Huaynaputina, and both crops and livestock sustained severe damage.

Between 11 and 17 villages within from the volcano were buried by the ash, including Calicanto, Chimpapampa, Cojraque, Estagagache, Moro Moro and San Juan de Dios south and southwest of Huaynaputina. The Huayruro Project began in 2015 and aims to rediscover these towns, and Calicanto was christened one of the 100

Thin tree rings and

Thin tree rings and

The Spanish explorers

The Spanish explorers

Ice cores in the Russian

Ice cores in the Russian

volcano

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plates ...

in a volcanic high plateau in southern Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = National seal

, national_motto = "Firm and Happy f ...

. Lying in the Central Volcanic Zone

The Andean Volcanic Belt is a major volcanic belt along the Andean cordillera in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. It is formed as a result of subduction of the Nazca Plate and Antarctic Plate underneath the South American ...

of the Andes

The Andes, Andes Mountains or Andean Mountains (; ) are the longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range is long, wide (widest between 18°S – 20°S ...

, it was formed by the subduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, ...

of the oceanic Nazca Plate

The Nazca Plate or Nasca Plate, named after the Nazca region of southern Peru, is an oceanic tectonic plate in the eastern Pacific Ocean basin off the west coast of South America. The ongoing subduction, along the Peru–Chile Trench, of the N ...

under the continental South American Plate

The South American Plate is a major tectonic plate which includes the continent of South America as well as a sizable region of the Atlantic Ocean seabed extending eastward to the African Plate, with which it forms the southern part of the Mid ...

. Huaynaputina is a large volcanic crater

A volcanic crater is an approximately circular depression in the ground caused by volcanic activity. It is typically a bowl-shaped feature containing one or more vents. During volcanic eruptions, molten magma and volcanic gases rise from an und ...

, lacking an identifiable mountain profile, with an outer stratovolcano and three younger volcanic vents within an amphitheatre

An amphitheatre (British English) or amphitheater (American English; both ) is an open-air venue used for entertainment, performances, and sports. The term derives from the ancient Greek ('), from ('), meaning "on both sides" or "around" and ...

-shaped structure that is either a former caldera

A caldera ( ) is a large cauldron-like hollow that forms shortly after the emptying of a magma chamber in a volcano eruption. When large volumes of magma are erupted over a short time, structural support for the rock above the magma chamber is ...

or a remnant of glacial

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betwe ...

erosion. The volcano has erupted dacitic

Dacite () is a volcanic rock formed by rapid solidification of lava that is high in silica and low in alkali metal oxides. It has a fine-grained (aphanitic) to porphyritic texture and is intermediate in composition between andesite and rhyol ...

magma.

In the Holocene

The Holocene ( ) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years Before Present (), after the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene togeth ...

, Huaynaputina has erupted several times, including on 19February 1600 – the largest eruption ever recorded in South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sou ...

– which continued with a series of events into March. Witnessed by people in the city of Arequipa

Arequipa (; Aymara and qu, Ariqipa) is a city and capital of province and the eponymous department of Peru. It is the seat of the Constitutional Court of Peru and often dubbed the "legal capital of Peru". It is the second most populated city ...

, it killed at least 1,000–1,500 people in the region, wiped out vegetation, buried the surrounding area with of volcanic rock and damaged infrastructure and economic resources. The eruption had a significant impact on Earth's climate, causing a volcanic winter

A volcanic winter is a reduction in global temperatures caused by volcanic ash and droplets of sulfuric acid and water obscuring the Sun and raising Earth's albedo (increasing the reflection of solar radiation) after a large, particularly explosiv ...

: temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the Equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined as being in the same celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the solar system as Earth's Nort ...

decreased; cold waves hit parts of Europe, Asia and the Americas; and the climate disruption may have played a role in the onset of the Little Ice Age

The Little Ice Age (LIA) was a period of regional cooling, particularly pronounced in the North Atlantic region. It was not a true ice age of global extent. The term was introduced into scientific literature by François E. Matthes in 1939. Ma ...

. Floods, famines, and social upheavals resulted. This eruption has been computed to measure 6 on the Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI).

The volcano has not erupted since 1600. There are fumarole

A fumarole (or fumerole) is a vent in the surface of the Earth or other rocky planet from which hot volcanic gases and vapors are emitted, without any accompanying liquids or solids. Fumaroles are characteristic of the late stages of volcani ...

s in the amphitheatre-shaped structure, and hot spring

A hot spring, hydrothermal spring, or geothermal spring is a spring produced by the emergence of geothermally heated groundwater onto the surface of the Earth. The groundwater is heated either by shallow bodies of magma (molten rock) or by circ ...

s occur in the region, some of which have been associated with Huaynaputina. The volcano lies in a remote region where there is little human activity, but about 30,000 people live in the immediately surrounding area, and another one million in the Arequipa metropolitan area. If an eruption similar to the 1600 event were to occur, it would quite likely lead to a high death toll and cause substantial socioeconomic disruption. The Peruvian Geophysical Institute announced in 2017 that Huaynaputina would be monitored by the Southern Volcanological Observatory, and seismic

Seismology (; from Ancient Greek σεισμός (''seismós'') meaning "earthquake" and -λογία (''-logía'') meaning "study of") is the scientific study of earthquakes and the propagation of elastic waves through the Earth or through other ...

observation began in 2019.

Name

The name Huaynaputina, also spelled Huayna Putina, was given to the volcano after the 1600 eruption. According to one translation cited by the Peruvian Ministry of Foreign Trade and Tourism, Huayna means 'new', and Putina means 'fire-throwing mountain'; the full name is meant to suggest the aggressiveness of its volcanic activity and refers to the 1600 eruption being its first one. Two other translations are 'young boiling one' – perhaps a reference to earlier eruptions – or 'where young were boiled', which may refer tohuman sacrifice

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease gods, a human ruler, an authoritative/priestly figure or spirits of dead ancestors or as a retainer sacrifice, wherei ...

s. Other names for the volcano include Chequepuquina, Chiquimote, Guayta, Omate and Quinistaquillas. The volcano El Misti was sometimes confused with and thus referred to mistakenly as Huaynaputina.

Geography

The volcano is part of theCentral Volcanic Zone

The Andean Volcanic Belt is a major volcanic belt along the Andean cordillera in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. It is formed as a result of subduction of the Nazca Plate and Antarctic Plate underneath the South American ...

of the Andes. Other volcanoes in this zone from northwest to southeast include Sara Sara

Sara Sara is a volcano lying between Lake Parinacochas and the Ocoña River in Peru. It is situated in the Parinacochas Province and the Paucar del Sara Sara Province. The volcano formed during the Pleistocene during four different stages of ...

, Coropuna

Coropuna is a dormant compound volcano located in the Andes mountains of southeast-central Peru. The upper reaches of Coropuna consist of several perennially snowbound conical summits, lending it the name Nevado Coropuna in Spanish. The compl ...

, Ampato

Ampato (possibly from Quechua ''hamp'atu'' or from Aymara ''jamp'atu'', both meaning "frog") is a dormant stratovolcano in the Andes of southern Peru. It lies about northwest of Arequipa and is part of a north-south chain that includes the volc ...

, Sabancaya

Sabancaya is an active stratovolcano in the Andes of southern Peru, about northwest of Arequipa. It is considered part of the Central Volcanic Zone of the Andes, one of the three distinct volcanic belts of the Andes. The Central Volcanic Zone ...

, El Misti, Ubinas

Ubinas is an active stratovolcano in the Moquegua Region of southern Peru, approximately east of the city of Arequipa. Part of the Central Volcanic Zone of the Andes, it rises above sea level. The volcano's summit is cut by a and caldera, w ...

, Ticsani

Ticsani is a volcano in Peru northwest of Moquegua and consists of two volcanoes ("Old Ticsani" and "Modern Ticsani") that form a complex. "Old Ticsani" is a compound volcano that underwent a large collapse in the past and shed of mass down the ...

, Tutupaca

Tutupaca is a volcano in the region of Tacna in Peru. It is part of the Peruvian segment of the Central Volcanic Zone, one of several volcanic belts in the Andes. Tutupaca consists of three overlapping volcanoes formed by lava flows and lava d ...

and Yucamane

Yucamane, Yucamani or Yucumane is an andesitic stratovolcano in the Tacna Region of southern Peru. It is part of the Peruvian segment of the Central Volcanic Zone, one of the three volcanic belts of the Andes generated by the subduction of the N ...

. Ubinas is the most active volcano in Peru; Huaynaputina, El Misti, Sabancaya, Ticsani, Tutupaca, Ubinas and Yucamane have been active in historical time, while Sara Sara, Coropuna, Ampato, Casiri and Chachani

Chachani is a volcanic group in southern Peru, northwest of the city of Arequipa. Part of the Central Volcanic Zone of the Andes, it is above sea level. It consists of several lava domes and individual volcanoes such as Nocarane, along with ...

are considered to be dormant. Most volcanoes of the Central Volcanic Zone are large composite volcano

A stratovolcano, also known as a composite volcano, is a conical volcano built up by many layers (strata) of hardened lava and tephra. Unlike shield volcanoes, stratovolcanoes are characterized by a steep profile with a summit crater and peri ...

es that can remain active over the span of several million years, but there are also conical stratovolcanoes with shorter lifespans. In the Central Volcanic Zone, large explosive eruption

In volcanology, an explosive eruption is a volcanic eruption of the most violent type. A notable example is the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens. Such eruptions result when sufficient gas has dissolved under pressure within a viscous magma su ...

s with Volcanic Explosivity Index of 6 and higher occur on average every 2,000 to 4,000 years.

Huaynaputina is in the Omate

Omate is a town in Southern Peru, capital of the province General Sánchez Cerro in the region Moquegua

Moquegua (, founded by the Spanish colonists as Villa de Santa Catalina de Guadalcázar del Valle de Moquegua) is a city in southern Peru ...

and Quinistaquillas Districts, which are part of the General Sánchez Cerro Province

The General Sánchez Cerro Province is the smallest of three provinces in the Moquegua Region of Peru. The capital of the province is Omate. The province was named after the former Peruvian army officer and president Luis Miguel Sánchez Cerro.

B ...

in the Moquegua Region

Moquegua () is a department and region in southern Peru that extends from the coast to the highlands. Its capital is the city of Moquegua, which is among the main Peruvian cities for its high rates of GDP and national education.

Geography

The ...

of southern Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = National seal

, national_motto = "Firm and Happy f ...

. The town of Omate

Omate is a town in Southern Peru, capital of the province General Sánchez Cerro in the region Moquegua

Moquegua (, founded by the Spanish colonists as Villa de Santa Catalina de Guadalcázar del Valle de Moquegua) is a city in southern Peru ...

lies southwest of Huaynaputina. The city of Moquegua

Moquegua (, founded by the Spanish colonists as Villa de Santa Catalina de Guadalcázar del Valle de Moquegua) is a city in southern Peru, located in the Department of Moquegua, of which it is the capital. It is also capital of Mariscal Nieto P ...

is south-southwest of the volcano and Arequipa

Arequipa (; Aymara and qu, Ariqipa) is a city and capital of province and the eponymous department of Peru. It is the seat of the Constitutional Court of Peru and often dubbed the "legal capital of Peru". It is the second most populated city ...

is to its north-northwest.

The region is generally remote and the terrain extreme, the area around Huaynaputina is not easily accessible and human activity low. Within of Huaynaputina there are a number of small farms. A cattle-grazing footpath leads from Quinistaquillas to the volcano, and it is possible to approach the volcano over surrounding ash plains. The landscapes around the volcano have unique characteristics that make them an important geological heritage.

Structure

Huaynaputina lies at an elevation of about . It consists of an outer composite volcano, or stratovolcano, and three younger volcanic vents nested within an amphitheatre that is wide and deep. Thishorseshoe-shaped

Many shapes have metaphorical names, i.e., their names are metaphors: these shapes are named after a most common object that has it. For example, "U-shape" is a shape that resembles the letter U, a bell-shaped curve has the shape of the vertical ...

structure opens eastwards and is set in the older volcano at an elevation of . The amphitheatre lies at the margin of a rectangular high plateau

In geology and physical geography, a plateau (; ; ), also called a high plain or a tableland, is an area of a highland consisting of flat terrain that is raised sharply above the surrounding area on at least one side. Often one or more sides ...

that is covered by about thick ash, extending over an area of . The volcano has generally modest dimensions and rises less than above the surrounding terrain, but the products of the volcano's 1600 eruption cover much of the region especially west, north and south from the amphitheatre. These include pyroclastic flow

A pyroclastic flow (also known as a pyroclastic density current or a pyroclastic cloud) is a fast-moving current of hot gas and volcanic matter (collectively known as tephra) that flows along the ground away from a volcano at average speeds of b ...

dune

A dune is a landform composed of wind- or water-driven sand. It typically takes the form of a mound, ridge, or hill. An area with dunes is called a dune system or a dune complex. A large dune complex is called a dune field, while broad, f ...

s that crop out from underneath the tephra

Tephra is fragmental material produced by a volcanic eruption regardless of composition, fragment size, or emplacement mechanism.

Volcanologists also refer to airborne fragments as pyroclasts. Once clasts have fallen to the ground, they r ...

. Deposits from the 1600 eruption and previous events also crop out within the amphitheatre walls. Another southeastward-opening landslide scar lies just north of Huaynaputina.

One of these funnel-shaped vents is a trough that cuts into the amphitheatre. The trough appears to be a remnant of a fissure vent

A fissure vent, also known as a volcanic fissure, eruption fissure or simply a fissure, is a linear volcanic vent through which lava erupts, usually without any explosive activity. The vent is often a few metres wide and may be many kilo ...

. A second vent appears to have been about wide before the development of a third vent, which has mostly obscured the first two. The third vent is steep-walled, with a depth of ; it contains a pit that is wide, set within a small mound that is in part nested within the second vent. This third vent is surrounded by concentric faults. At least one of the vents has been described as an ash cone. A fourth vent lies on the southern slope of the composite volcano outside of the amphitheatre and has been described as a maar

A maar is a broad, low-relief volcanic crater caused by a phreatomagmatic eruption (an explosion which occurs when groundwater comes into contact with hot lava or magma). A maar characteristically fills with water to form a relatively shallo ...

. It is about wide and deep and appears to have formed during a phreatomagmatic

Phreatomagmatic eruptions are volcanic eruptions resulting from interaction between magma and water. They differ from exclusively magmatic eruptions and phreatic eruptions. Unlike phreatic eruptions, the products of phreatomagmatic eruptions cont ...

eruption. These vents lie at an elevation of about , making them among the highest vents of a Plinian eruption in the world.

Slumps have buried parts of the amphitheatre. Dacitic

Dacite () is a volcanic rock formed by rapid solidification of lava that is high in silica and low in alkali metal oxides. It has a fine-grained (aphanitic) to porphyritic texture and is intermediate in composition between andesite and rhyol ...

dykes crop out within the amphitheatre and are aligned along a northwest–south trending lineament ''See also Line (geometry)''

A lineament is a linear feature in a landscape which is an expression of an underlying geological structure such as a fault. Typically a lineament will appear as a fault-aligned valley, a series of fault or fold-alig ...

that the younger vents are also located on. These dykes and a dacitic

Dacite () is a volcanic rock formed by rapid solidification of lava that is high in silica and low in alkali metal oxides. It has a fine-grained (aphanitic) to porphyritic texture and is intermediate in composition between andesite and rhyol ...

lava dome

In volcanology, a lava dome is a circular mound-shaped protrusion resulting from the slow extrusion of viscous lava from a volcano. Dome-building eruptions are common, particularly in convergent plate boundary settings. Around 6% of eruptions ...

of similar composition were formed before the 1600 eruption. Faults with recognizable scarp

Scarp may refer to:

Landforms and geology

* Cliff, a significant vertical, or near vertical, rock exposure

* Escarpment, a steep slope or long rock that occurs from erosion or faulting and separates two relatively level areas of differing elevatio ...

s occur within the amphitheatre and have offset the younger vents; some of these faults existed before the 1600 eruption while others were activated during the event.

Surroundings

The terrain west of the volcano is a high plateau at an elevation of about ; north of Huaynaputina the volcano Ubinas and the depression of Laguna Salinas lie on the plateau, while the peaks Cerro El Volcán and Cerro Chen are situated south of it. The lava dome Cerro El Volcán and another small lava dome, Cerro Las Chilcas, lie south from Huaynaputina. Northeast-east of Huaynaputina, the terrain drops off steeply ( vertically and horizontally) into the Río Tambo valley, which rounds Huaynaputina east and south of the volcano. Some tributary valleys join the Río Tambo from Huaynaputina; clockwise from the east these are the Quebradas Huaynaputina, Quebrada Tortoral, Quebrada Aguas Blancas and Quebrada del Volcán. The Río Tambo eventually flows southwestward into thePacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the conti ...

.

Geology

The oceanic Nazca tectonic plate is

The oceanic Nazca tectonic plate is subduct

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, the ...

ing at a rate of beneath the continental part of the South American tectonic plate; this process is responsible for volcanic activity and the uplift of the Andes

The Andes, Andes Mountains or Andean Mountains (; ) are the longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range is long, wide (widest between 18°S – 20°S ...

mountains and of the Altiplano

The Altiplano (Spanish for "high plain"), Collao (Quechua and Aymara: Qullaw, meaning "place of the Qulla") or Andean Plateau, in west-central South America, is the most extensive high plateau on Earth outside Tibet. The plateau is located at ...

plateau. The subduction is oblique, leading to strike-slip fault

In geology, a fault is a planar fracture or discontinuity in a volume of rock across which there has been significant displacement as a result of rock-mass movements. Large faults within Earth's crust result from the action of plate tectoni ...

ing. Volcanic activity does not occur along the entire length of the Andes; where subduction is shallow, there are gaps with little volcanic activity. Between these gaps lie volcanic belts: the Northern Volcanic Zone

The Andean Volcanic Belt is a major volcanic belt along the Andean cordillera in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. It is formed as a result of subduction of the Nazca Plate and Antarctic Plate underneath the South America ...

, the Central Volcanic Zone, the Southern Volcanic Zone

The Andean Volcanic Belt is a major volcanic belt along the Andean cordillera in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. It is formed as a result of subduction of the Nazca Plate and Antarctic Plate underneath the South America ...

and the Austral Volcanic Zone

The Andean Volcanic Belt is a major volcanic belt along the Andean cordillera in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. It is formed as a result of subduction of the Nazca Plate and Antarctic Plate underneath the South America ...

.

There are about 400 Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.333 million to 2.58Quaternary

The Quaternary ( ) is the current and most recent of the three periods of the Cenozoic Era in the geologic time scale of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS). It follows the Neogene Period and spans from 2.58 million year ...

volcanoes in Peru, with Quaternary activity occurring only in the southern part of the country. Peruvian volcanoes are part of the Central Volcanic Zone. Volcanic activity in that zone has moved eastward since the Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The Jurassic constitutes the middle period of ...

. Remnants of the older volcanism persist in the coastal Cordillera de la Costa but the present-day volcanic arc lies in the Andes, where it is defined by stratovolcano

A stratovolcano, also known as a composite volcano, is a conical volcano built up by many layers (strata) of hardened lava and tephra. Unlike shield volcanoes, stratovolcanoes are characterized by a steep profile with a summit crater and peri ...

es. Many Peruvian volcanoes are poorly studied because they are remote and difficult to access.

The basement

A basement or cellar is one or more Storey, floors of a building that are completely or partly below the storey, ground floor. It generally is used as a utility space for a building, where such items as the Furnace (house heating), furnace, ...

underneath Huaynaputina is formed by almost sediments

Sediment is a naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and erosion, and is subsequently transported by the action of wind, water, or ice or by the force of gravity acting on the particles. For example, sa ...

and volcanic intrusions of Paleozoic

The Paleozoic (or Palaeozoic) Era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The name ''Paleozoic'' ( ;) was coined by the British geologist Adam Sedgwick in 1838

by combining the Greek words ''palaiós'' (, "old") and ...

to Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretace ...

age including the Yura Group, as well as the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

Matalaque Formation of volcanic origin – these are all units of rock that existed before the formation of Huaynaputina. During the Tertiary

Tertiary ( ) is a widely used but obsolete term for the geologic period from 66 million to 2.6 million years ago.

The period began with the demise of the non-avian dinosaurs in the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, at the start ...

, these were overlaid by a total of deposits from the ignimbritic Capillune, Llallahui and Sencca Formation

Formation may refer to:

Linguistics

* Back-formation, the process of creating a new lexeme by removing or affixes

* Word formation, the creation of a new word by adding affixes

Mathematics and science

* Cave formation or speleothem, a secondar ...

s – all older rock units. Cretaceous sediments and Paleogene–Neogene volcanic rocks form the high plateau around Huaynaputina. The emplacement of the Capillune Formation continued into the earliest Pliocene; subsequently the Plio-Pleistocene

The Plio-Pleistocene is an informally described geological pseudo-period, which begins about 5 million years ago (Mya) and, drawing forward, combines the time ranges of the formally defined Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs—marking from about 5&n ...

Barroso Group was deposited. It includes the composite volcano that hosts Huaynaputina as well as ignimbrites that appear to come from caldera

A caldera ( ) is a large cauldron-like hollow that forms shortly after the emptying of a magma chamber in a volcano eruption. When large volumes of magma are erupted over a short time, structural support for the rock above the magma chamber is ...

s. One such caldera is located just south of Huaynaputina. The late Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

to Holocene

The Holocene ( ) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years Before Present (), after the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene togeth ...

volcanoes have been classified as the Arequipa Volcanics.

Local

The vents of Huaynaputina trend from the north-northwest to the south-southeast, and this trend encompasses the neighbouring volcanoes Ubinas and Ticsani. Ubinas is a typical stratovolcano while Ticsani has a similar structure to Huaynaputina. These volcanoes constitute avolcanic field

A volcanic field is an area of Earth's crust that is prone to localized volcanic activity. The type and number of volcanoes required to be called a "field" is not well-defined. Volcanic fields usually consist of clusters of up to 100 volcanoes ...

located behind the major volcanic arc, associated with faults at the margin of the Río Tambo graben

In geology, a graben () is a depressed block of the crust of a planet or moon, bordered by parallel normal faults.

Etymology

''Graben'' is a loan word from German, meaning 'ditch' or 'trench'. The word was first used in the geologic conte ...

and regional strike-slip faults. The faults associated with the volcanic complex have influenced the evolution of the constituent volcanoes including Huaynaputina by acting as conduits for ascending magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also been discovered on other terrestrial planets and some natura ...

especially at fault intersections. The volcanic rocks produced by these volcanoes have similar compositions, and historical seismic and volcanic activity at Ubinas and Ticsani indicate that they share a magma reservoir. A magma reservoir may underpin this volcanic system.

Composition

The eruption products of the 1600 eruption aredacite

Dacite () is a volcanic rock formed by rapid solidification of lava that is high in silica and low in alkali metal oxides. It has a fine-grained ( aphanitic) to porphyritic texture and is intermediate in composition between andesite and rhyo ...

s, which define a calc-alkaline

The calc-alkaline magma series is one of two main subdivisions of the subalkaline magma series, the other subalkaline magma series being the tholeiitic series. A magma series is a series of compositions that describes the evolution of a mafic m ...

, potassium

Potassium is the chemical element with the symbol K (from Neo-Latin '' kalium'') and atomic number19. Potassium is a silvery-white metal that is soft enough to be cut with a knife with little force. Potassium metal reacts rapidly with atmos ...

-rich suite sometimes described as adakitic. The 1600 rocks also contain rhyolite

Rhyolite ( ) is the most silica-rich of volcanic rocks. It is generally glassy or fine-grained (aphanitic) in texture, but may be porphyritic, containing larger mineral crystals ( phenocrysts) in an otherwise fine-grained groundmass. The miner ...

inclusions and a rhyolite matrix

Matrix most commonly refers to:

* ''The Matrix'' (franchise), an American media franchise

** '' The Matrix'', a 1999 science-fiction action film

** "The Matrix", a fictional setting, a virtual reality environment, within ''The Matrix'' (franchi ...

. Andesite

Andesite () is a volcanic rock of intermediate composition. In a general sense, it is the intermediate type between silica-poor basalt and silica-rich rhyolite. It is fine-grained (aphanitic) to porphyritic in texture, and is composed predo ...

has also been found at Huaynaputina. Phenocryst

300px, feldspathic phenocrysts. This granite, from the Switzerland">Swiss side of the Mont Blanc massif, has large white plagioclase phenocrysts, triclinic minerals that give trapezoid shapes when cut through). 1 euro coins, 1 euro coin (diameter ...

s include biotite

Biotite is a common group of phyllosilicate minerals within the mica group, with the approximate chemical formula . It is primarily a solid-solution series between the iron- endmember annite, and the magnesium-endmember phlogopite; more ...

, chalcopyrite

Chalcopyrite ( ) is a copper iron sulfide mineral and the most abundant copper ore mineral. It has the chemical formula CuFeS2 and crystallizes in the tetragonal system. It has a brassy to golden yellow color and a hardness of 3.5 to 4 on the Mo ...

, hornblende

Hornblende is a complex inosilicate series of minerals. It is not a recognized mineral in its own right, but the name is used as a general or field term, to refer to a dark amphibole. Hornblende minerals are common in igneous and metamorphic rock ...

, ilmenite

Ilmenite is a titanium-iron oxide mineral with the idealized formula . It is a weakly magnetic black or steel-gray solid. Ilmenite is the most important ore of titanium and the main source of titanium dioxide, which is used in paints, printing ...

, magnetite

Magnetite is a mineral and one of the main iron ores, with the chemical formula Fe2+Fe3+2O4. It is one of the oxides of iron, and is ferrimagnetic; it is attracted to a magnet and can be magnetized to become a permanent magnet itself. With ...

and plagioclase

Plagioclase is a series of tectosilicate (framework silicate) minerals within the feldspar group. Rather than referring to a particular mineral with a specific chemical composition, plagioclase is a continuous solid solution series, more p ...

; amphibole

Amphibole () is a group of inosilicate minerals, forming prism or needlelike crystals, composed of double chain tetrahedra, linked at the vertices and generally containing ions of iron and/or magnesium in their structures. Its IMA symbol is ...

, apatite

Apatite is a group of phosphate minerals, usually hydroxyapatite, fluorapatite and chlorapatite, with high concentrations of OH−, F− and Cl− ions, respectively, in the crystal. The formula of the admixture of the three most common ...

and pyroxene

The pyroxenes (commonly abbreviated to ''Px'') are a group of important rock-forming inosilicate minerals found in many igneous and metamorphic rocks. Pyroxenes have the general formula , where X represents calcium (Ca), sodium (Na), iron (Fe I ...

have been reported as well. Aside from newly formed volcanic rocks, Huaynaputina in 1600 also erupted material that is derived from rocks underlying the volcano, including sediments and older volcanic rocks, both of which were hydrothermal

Hydrothermal circulation in its most general sense is the circulation of hot water (Ancient Greek ὕδωρ, ''water'',Liddell, H.G. & Scott, R. (1940). ''A Greek-English Lexicon. revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones. with th ...

ly altered. Pumice

Pumice (), called pumicite in its powdered or dust form, is a volcanic rock that consists of highly vesicular rough-textured volcanic glass, which may or may not contain crystals. It is typically light-colored. Scoria is another vesicular v ...

s from Huaynaputina are white.

The amount of volatiles in the magma appears to have decreased during the 1600 eruption, indicating that it originated either in two separate magma chamber

A magma chamber is a large pool of liquid rock beneath the surface of the Earth. The molten rock, or magma, in such a chamber is less dense than the surrounding country rock, which produces buoyant forces on the magma that tend to drive it up ...

s or from one zoned chamber. This may explain changes in the eruption phenomena during the 1600 activity as the "Dacite 1" rocks erupted early during the 1600 event were more buoyant and contained more gas and thus drove a Plinian eruption, while the latter "Dacite 2" rocks were more viscous and only generated Vulcanian eruption

A Vulcanian eruption is a type of volcanic eruption characterized by a dense cloud of ash-laden gas exploding from the crater and rising high above the peak. They usually commence with phreatomagmatic eruptions which can be extremely noisy due t ...

s. Interactions with the crust and crystal fractionation processes were involved in the genesis of the magmas as well, with the so-called "Dacite 1" geochemical suite forming deep in the crust, while the "Dacite 2" geochemical suite appears to have interacted with the upper crust.

The rocks had a temperature of about when they were erupted, with the "Dacite 1" being hotter than the "Dacite 2". Their formation may have been stimulated by the entry of mafic

A mafic mineral or rock is a silicate mineral or igneous rock rich in magnesium and iron. Most mafic minerals are dark in color, and common rock-forming mafic minerals include olivine, pyroxene, amphibole, and biotite. Common mafic rocks in ...

magmas into the magmatic system; such an entry of new magma in a volcanic system is often the trigger for explosive eruptions. The magmas erupted early during the 1600 event (in the first stage of the eruption) appear to have originated from depths of more than ; petrological analysis indicates that some magmas came from depths greater than and others from about . An older hypothesis by de Silva and Francis held that the entry of water into the magmatic system may have triggered the eruption. A 2006 study argues that the entry of new dacitic magma into an already existing dacitic magma system triggered the 1600 eruption; furthermore movement of deep andesitic magmas that had generated the new dacite produced movements within the volcano.

Eruption history

The ancestral composite volcano that holds Huaynaputina is part of the Pastillo volcanic complex, which developed in the form of thick andesitic rocks after the Miocene, and appears to be of Miocene to Pleistocene age. It underwentsector collapse

A sector collapse is the collapse of a portion of a volcano due to a phreatic eruption, an earthquake, or the intervention of new magma. Occurring on many volcanoes, sector collapses are generally one of the most hazardous volcanic events, and will ...

s and glacial erosion

Erosion is the action of surface processes (such as water flow or wind) that removes soil, rock, or dissolved material from one location on the Earth's crust, and then transports it to another location where it is deposited. Erosion is dist ...

, which altered its appearance and its flanks. The amphitheatre which contains the Huaynaputina vents formed probably not as a caldera but either a glacial cirque

A (; from the Latin word ') is an amphitheatre-like valley formed by glacial erosion. Alternative names for this landform are corrie (from Scottish Gaelic , meaning a pot or cauldron) and (; ). A cirque may also be a similarly shaped landf ...

, a sector collapse scar or another kind of structure that was altered by fluvial and glacial erosion. Other extinct volcanoes in the area have similar amphitheatre structures. It is likely that the development of the later Huaynaputina volcano within the composite volcano is coincidental, although a similar tectonic

Tectonics (; ) are the processes that control the structure and properties of the Earth's crust and its evolution through time. These include the processes of mountain building, the growth and behavior of the strong, old cores of continents ...

stress field controlled the younger vents.

Recently emplaced, postglacial

The Holocene ( ) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years Before Present (), after the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene togethe ...

dacite bodies occur in the Huaynaputina area, some of which probably formed shortly before the 1600 eruption. Cerro Las Chilcas also predates the 1600 eruption and appears to be the earliest volcanic centre in the area. The Cerro El Volcán dome formed during the Quaternary and may be the remnant of a cluster of lava domes south of Huaynaputina.

Holocene

Tephra and block-and-ash flow deposits from Holocene eruptions can be found within the amphitheatre. Some tephra layers that are 7,000 to 1,000 years old and close to Ubinas volcano have been attributed to activity at Huaynaputina. Three eruptions of the volcano have been dated to 9,700 ± 190, less than 7,480 ± 40 years ago and 5,750 yearsBefore Present

Before Present (BP) years, or "years before present", is a time scale used mainly in archaeology, geology and other scientific disciplines to specify when events occurred relative to the origin of practical radiocarbon dating in the 1950s. Beca ...

, respectively. The first two eruptions produced pumice falls and pyroclastic flow

A pyroclastic flow (also known as a pyroclastic density current or a pyroclastic cloud) is a fast-moving current of hot gas and volcanic matter (collectively known as tephra) that flows along the ground away from a volcano at average speeds of b ...

s. The first of these, a Plinian eruption, also deposited tephra in Laguna Salinas, north of Huaynaputina, and produced a block-and-ash flow to its south. A debris avalanche deposit crops out on the eastern side of the Río Tambo, opposite to the amphitheatre; it may have been formed not long before the 1600 eruption.

The existence of a volcano at Huaynaputina was not recognized before the 1600 eruption, with no known previous eruptions other than fumarolic

A fumarole (or fumerole) is a vent in the surface of the Earth or other rocky planet from which hot volcanic gases and vapors are emitted, without any accompanying liquids or solids. Fumaroles are characteristic of the late stages of volc ...

activity. As a result, the 1600 eruption has been referred to as an instance of monogenetic volcanism. The pre-1600 topography of the volcano was described as "a low ridge in the center of a Sierra", and it is possible that a cluster of lava domes existed at the summit before the 1600 eruption which was blown away during the event.

The last eruption before 1600 may have preceded that year by several centuries, based on the presence of volcanic eruption products buried under soil. Native people reportedly offered sacrifices and offerings to the mountain such as birds, personal clothing and sheep, although it is known that non-volcanic mountains in southern Peru received offerings as well. There have been no eruptions since 1600; a report of an eruption in 1667 is unsubstantiated and unclear owing to the sparse historical information. It probably reflects an eruption at Ubinas instead.

Fumaroles and hot springs

Fumaroles occur in the amphitheatre close to the three vents, on the third vent, and in association with dykes that crop out in the amphitheatre. In 1962, there were reportedly no fumaroles within the amphitheatre. These fumaroles produce white fumes and smell of rotten eggs. The fumarolic gas composition is dominated bywater vapour

(99.9839 °C)

, -

, Boiling point

,

, -

, specific gas constant

, 461.5 J/( kg·K)

, -

, Heat of vaporization

, 2.27 MJ/kg

, -

, Heat capacity

, 1.864 kJ/(kg·K)

Water vapor, water vapour or aqueous vapor is the gaseous pha ...

, with smaller quantities of carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide ( chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is t ...

and sulfur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formul ...

gases. Investigations in 2010 recorded temperatures of for the gases, with seasonal variations. Vegetation has grown at their vents.

Hot spring

A hot spring, hydrothermal spring, or geothermal spring is a spring produced by the emergence of geothermally heated groundwater onto the surface of the Earth. The groundwater is heated either by shallow bodies of magma (molten rock) or by circ ...

s occur in the region and some of these have been associated with Huaynaputina; these include Candagua and Palcamayo northeast, Agua Blanca and Cerro Reventado southeast from the volcano on the Río Tambo and Ullucan almost due west. The springs have temperatures ranging from and contain large amounts of dissolved salt

Salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl), a chemical compound belonging to the larger class of salts; salt in the form of a natural crystalline mineral is known as rock salt or halite. Salt is present in vast quant ...

s. Cerro Reventado and Ullucan appear to be fed from magmatic water and a deep reservoir, while Agua Blanca is influenced by surface waters.

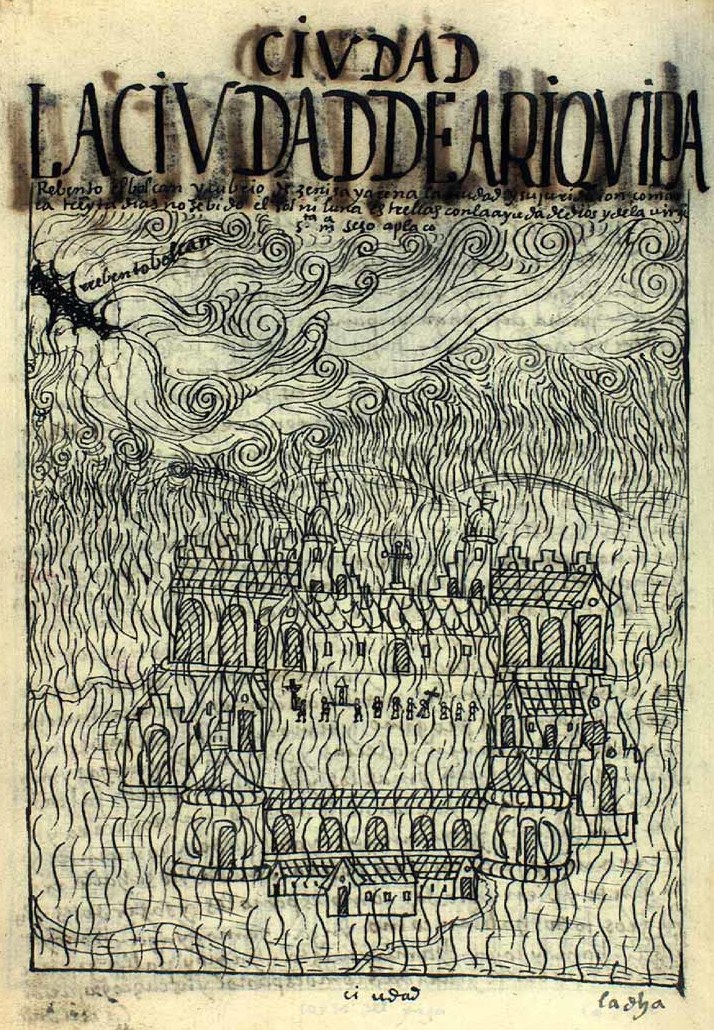

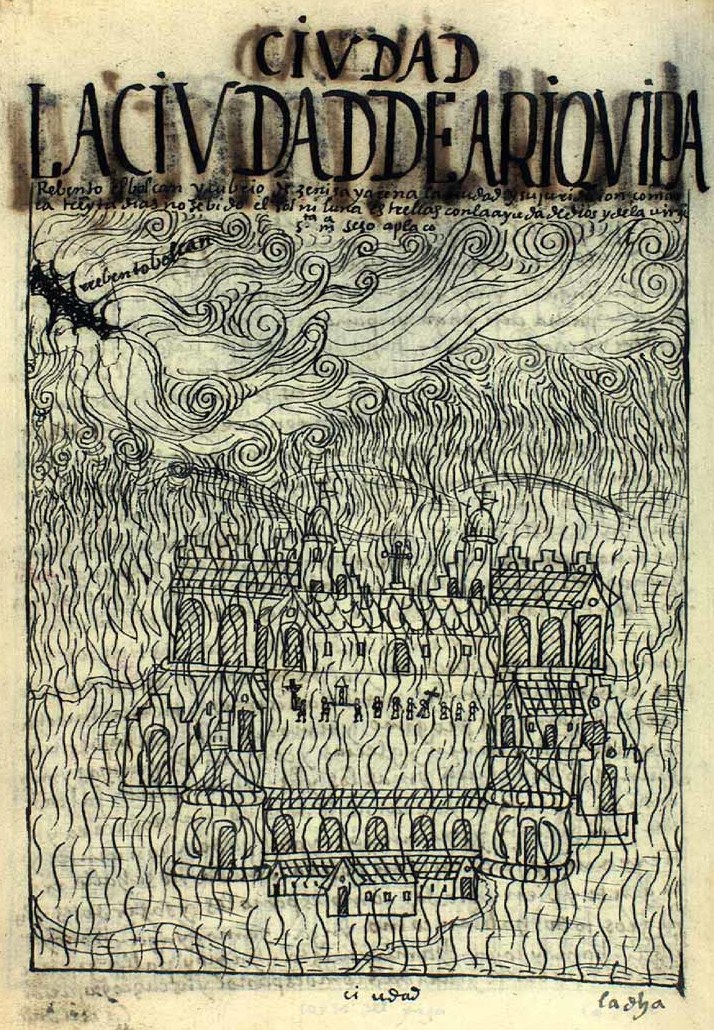

1600 eruption

Based on historical records, Huaynaputina's eruption commenced on 19February 1600 (following earthquakes that began four days prior), with the earliest signs of the impending eruption perhaps in December1599. The duration of the eruption is not well constrained but may have lasted up to 12–19 hours. The event continued with earthquakes and ash fall for about two weeks and ended on 6March; the air was clear of ash from the eruption on 2April 1600. Some reports of late ash falls may be due to wind-transported ash, and there are no deposits from a supposed eruption in August1600; such reports may refer tomudflow

A mudflow or mud flow is a form of mass wasting involving fast-moving flow of debris that has become liquified by the addition of water. Such flows can move at speeds ranging from 3 meters/minute to 5 meters/second. Mudflows contain a significa ...

s or explosions in pyroclastic flows.

The eruption of 1600 was initially attributed to Ubinas volcano and sometimes to El Misti. Priests observed and recorded the eruption from Arequipa, and the friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders founded in the twelfth or thirteenth century; the term distinguishes the mendicants' itinerant apostolic character, exercised broadly under the jurisdiction of a superior general, from the ...

Antonio Vázquez de Espinosa

Fray Antonio Vazquez de Espinosa (born in Jerez de la Frontera and died Seville, 1630) was a Spanish friar of the Discalced Carmelites originally from Jerez de la Frontera whose ''Compendio y Descripcion de las Indias Occidentales'' has become a so ...

wrote a second-hand account of the eruption based on a witness's report from the city. The scale of the eruption and its impact on climate have been determined from historical records, tree ring data, the position of glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires distinguishing features, such a ...

s, the thickness of speleothem

A speleothem (; ) is a geological formation by mineral deposits that accumulate over time in natural caves. Speleothems most commonly form in calcareous caves due to carbonate dissolution reactions. They can take a variety of forms, dependi ...

s and ice, plant flower

A flower, sometimes known as a bloom or blossom, is the reproductive structure found in flowering plants (plants of the division Angiospermae). The biological function of a flower is to facilitate reproduction, usually by providing a mechanis ...

ing times, wine

Wine is an alcoholic drink typically made from Fermentation in winemaking, fermented grapes. Yeast in winemaking, Yeast consumes the sugar in the grapes and converts it to ethanol and carbon dioxide, releasing heat in the process. Different ...

harvests and coral

Corals are marine invertebrates within the class Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact colonies of many identical individual polyps. Coral species include the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and se ...

growth. Stratigraphically, the eruption deposits have been subdivided into five formation

Formation may refer to:

Linguistics

* Back-formation, the process of creating a new lexeme by removing or affixes

* Word formation, the creation of a new word by adding affixes

Mathematics and science

* Cave formation or speleothem, a secondar ...

s.

Prelude and sequence of events

The eruption may have been triggered when new, "Dacite 1" magma entered into a magmatic system containing "Dacite 2" magma and pressurized the system, causing magma to begin ascending to the surface. In the prelude to the eruption, magma moving upwards to the future vents caused earthquakes beginning at a shallow reservoir at a depth of ; according to the accounts of priests, people in Arequipa fled their houses out of fear that they would collapse. The rising magma appears to have intercepted an older hydrothermal system that existed as much as below the vents; parts of the system were expelled during the eruption. Once the magma reached the surface, the eruption quickly became intense. A first Plinian stage took place on 19 and 20February, accompanied by an increase of earthquake activity. The first Plinian event lasted for about 20 hours and formed pumice deposits close to the vent that were thick. The pumice was buried by the ash erupted during this stage, which has been recorded as far asAntarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest cont ...

. This stage of the eruption produced at least of rocks, comprising the bulk of the output from the 1600 eruption. A sustained eruption column

An eruption column or eruption plume is a cloud of super-heated ash and tephra suspended in gases emitted during an explosive volcanic eruption. The volcanic materials form a vertical column or plume that may rise many kilometers into the ai ...

about high likely created a mushroom cloud

A mushroom cloud is a distinctive mushroom-shaped flammagenitus cloud of debris, smoke and usually condensed water vapor resulting from a large explosion. The effect is most commonly associated with a nuclear explosion, but any sufficiently ener ...

that darkened the sky, obscuring the sun and the stars. Afterwards, collapses in the amphitheatre and within the vent enlarged both features; they also decreased the intensity of the eruption. A first pyroclastic flow was deposited already during this time when the column became unstable.

The Plinian stage was channelled by a fracture

Fracture is the separation of an object or material into two or more pieces under the action of stress. The fracture of a solid usually occurs due to the development of certain displacement discontinuity surfaces within the solid. If a displ ...

and had the characteristics of a fissure-fed eruption. Possibly, the second vent formed during this stage, but another interpretation is that the second vent is actually a collapse structure that formed late during the eruption. Much of the excavation of the conduit took place during this stage.

After a hiatus the volcano began erupting pyroclastic flows; these were mostly constrained by the topography and were erupted in stages, intercalated by ash fall that extended to larger distances. Most of these pyroclastic flows accumulated in valleys radiating away from Huaynaputina, reaching distances of from the vents. Winds blew ash from the pyroclastic flows, and rain eroded freshly deposited pyroclastic deposits. Ash fall and pyroclastic flows alternated during this stage, probably caused by brief obstructions of the vent; at this time a lava dome formed within the second vent. A change in the composition of the erupted rocks occurred, the "Dacite 1" geochemical suite being increasingly modified by the "Dacite 2" geochemical suite that became dominant during the third stage.

Pyroclastic flows ran down the slopes of the volcano, entered the Río Tambo valley and formed dams on the river, probably mainly at the mouth of the Quebrada Aguas Blancas; one of the two dammed lakes was about long. When the dams failed, the lakes released hot water with floating pumice and debris down the Río Tambo. The deposits permanently altered the course of the river. The volume of the ignimbrites has been estimated to be about , excluding the ash that was erupted during this stage. The pyroclastic flows along with pumice falls covered an area of about .

In the third stage, Vulcanian eruptions took place at Huaynaputina and deposited another ash layer; it is thinner than the layer produced by the first stage eruption and appears to be partly of phreatomagmatic origin. During this stage the volcano also emitted lava bomb

A volcanic bomb or lava bomb is a mass of partially molten rock (tephra) larger than 64 mm (2.5 inches) in diameter, formed when a volcano ejects viscous fragments of lava during an eruption. Because volcanic bombs cool after they l ...

s; the total volume of erupted tephra is about . This third stage destroyed the lava dome and formed the third vent, which then began to settle along the faults as the underlying magma was exhausted. The fourth vent formed late during the eruption, outside of the amphitheatre.

Witness observations

The eruption was accompanied by intense earthquakes, deafening explosions and noises that could be heard beyondLima

Lima ( ; ), originally founded as Ciudad de Los Reyes (City of The Kings) is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín Rivers, in the desert zone of the central coastal part of ...

and as far away as . In Arequipa, the sky was illuminated by lightning

Lightning is a naturally occurring electrostatic discharge during which two electrically charged regions, both in the atmosphere or with one on the ground, temporarily neutralize themselves, causing the instantaneous release of an average ...

, and ash fell so thick that houses collapsed. The noise of the eruption was perceived as resembling artillery fire. There and in Copacabana the sky became dark. The blasts of the eruption could be heard (anecdotally) as far as Argentina and in the coastal localities of Lima, Chiquiabo and Arica

Arica ( ; ) is a commune and a port city with a population of 222,619 in the Arica Province of northern Chile's Arica y Parinacota Region. It is Chile's northernmost city, being located only south of the border with Peru. The city is the capita ...

. In these coastal localities it was thought that the sound came from naval engagements, likely with English corsairs. In view of this, the Viceroy of Peru sent reinforcement troops to El Callao. Closer to the vents, inhabitants of the village of Puquina saw large tongues of fire rising into the sky from Huaynaputina before they were enveloped by raining pumice and ash.

Caldera collapse

It was initially assumed that caldera collapse took place during the 1600 event, as accounts of the eruption stated that the volcano was obliterated to its foundation; later investigation suggested otherwise. Normally very large volcanic eruptions are accompanied by the formation of a caldera, but exceptions do exist. This might reflect either the regional tectonics or the absence of a shallow magma chamber, which prevented the collapse of the chamber from reaching the surface; most of the magma erupted in 1600 originated at a depth of . Some collapse structures did nevertheless develop at Huaynaputina, in the form of two not readily recognizable circular areas within the amphitheatre and around the three vents, probably when the magmatic system depressurized during the eruption. Also, part of the northern flank of the amphitheatre collapsed during the eruption, and some of the debris fell into the Río Tambo canyon.Volume and products

The 1600 eruption had a Volcanic Explosivity Index of 6 and is considered to be the only major explosive eruption of the Andes in historical time. It is the largest volcanic eruption throughout South America in historical time, as well as one of the largest in the last millennium and the largest historical eruption in theWestern Hemisphere

The Western Hemisphere is the half of the planet Earth that lies west of the prime meridian (which crosses Greenwich, London, United Kingdom) and east of the antimeridian. The other half is called the Eastern Hemisphere. Politically, the te ...

. It was larger than the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa

Krakatoa (), also transcribed (), is a caldera in the Sunda Strait between the islands of Java and Sumatra in the Indonesian province of Lampung. The caldera is part of a volcanic island group ( Krakatoa archipelago) comprising four islands. T ...

in Indonesia and the 1991 eruption of Pinatubo in the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

. Huaynaputina's eruption column was high enough to penetrate the tropopause

The tropopause is the atmospheric boundary that demarcates the troposphere from the stratosphere; which are two of the five layers of the atmosphere of Earth. The tropopause is a thermodynamic gradient-stratification layer, that marks the end of ...

and influence the climate of Earth.

The total volume of volcanic rocks erupted by Huaynaputina was about , in the form of dacitic tephra, pyroclastic flows and pyroclastic surges, although smaller estimates have been proposed. It appears that the bulk of the fallout originated during the first stage of the eruption, the second and third stage contributing a relatively small portion. For comparison, another large Holocene eruption in the Central Andes—the eruption of Cerro Blanco in Argentina about 2,300 ± 60 BCE

Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE) are year notations for the Gregorian calendar (and its predecessor, the Julian calendar), the world's most widely used calendar era. Common Era and Before the Common Era are alternatives to the or ...

—produced a bulk volume of of rock, equivalent to a Volcanic Explosivity Index of 7. Estimates have been made for the dense-rock equivalent

Dense-rock equivalent (DRE) is a volcanologic calculation used to estimate volcanic eruption volume. One of the widely accepted measures of the size of a historic or prehistoric eruption is the volume of magma ejected as pumice and volcanic ash, ...

of the Huaynaputina eruption, ranging between , with a 2019 estimate, that accounts for far-flung tephra, of .

Tephra fallout

archeological site

An archaeological site is a place (or group of physical sites) in which evidence of past activity is preserved (either prehistoric or historic or contemporary), and which has been, or may be, investigated using the discipline of archaeology an ...

s are preserved under them.

Some tephra was deposited on the volcanoes El Misti and Ubinas, into lakes of southern Peru such as Laguna Salinas, possibly into a peat bog close to Sabancaya volcano where it reached thicknesses of , as far south as in the Peruvian Atacama Desert

The Atacama Desert ( es, Desierto de Atacama) is a desert plateau in South America covering a 1,600 km (990 mi) strip of land on the Pacific coast, west of the Andes Mountains. The Atacama Desert is the driest nonpolar desert in th ...

where it forms discontinuous layers and possibly to the Cordillera Vilcabamba in the north. Ash layers about thick were noted in the ice cap

In glaciology, an ice cap is a mass of ice that covers less than of land area (usually covering a highland area). Larger ice masses covering more than are termed ice sheets.

Description

Ice caps are not constrained by topographical feat ...

s of Quelccaya in Peru and Sajama in Bolivia, although the deposits in Sajama may instead have originated from Ticsani volcano. Reports of Huaynaputina-related ashfall in Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the coun ...

are implausible, as Nicaragua is far from Huaynaputina and has several local volcanoes that could generate tephra fallout.

The Huaynaputina ash layer has been used as a tephrochronological marker for the region, for example in archeology

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts ...

and in geology, where it was used to date an eruption in the Andagua volcanic field and fault movements that could have produced destructive earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, fr ...

s. The ash layer, which may have reached as far as East Rongbuk Glacier

The Rongbuk Glacier () is located in the Himalaya of southern Tibet. Two large tributary glaciers, the East Rongbuk Glacier and the West Rongbuk Glacier, flow into the main Rongbuk Glacier. It flows north and forms the Rongbuk Valley north of Moun ...

at Mount Everest

Mount Everest (; Tibetan: ''Chomolungma'' ; ) is Earth's highest mountain above sea level, located in the Mahalangur Himal sub-range of the Himalayas. The China–Nepal border runs across its summit point. Its elevation (snow hei ...

in the Himalaya

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; ; ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest. Over 10 ...

, has also been used as a tephrochronological marker in Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland ...

and Antarctic

The Antarctic ( or , American English also or ; commonly ) is a polar region around Earth's South Pole, opposite the Arctic region around the North Pole. The Antarctic comprises the continent of Antarctica, the Kerguelen Plateau and othe ...

ice cores. It has been proposed as a marker for the onset of the Anthropocene

The Anthropocene ( ) is a proposed geological epoch dating from the commencement of significant human impact on Earth's geology and ecosystems, including, but not limited to, anthropogenic climate change.

, neither the International Commissio ...

.

Local impact

The eruption had a devastating impact on the region. Ash falls and pumice falls buried the surroundings beneath more than of rocks, while pyroclastic flows incinerated everything within their path, wiping out vegetation over a large area. Of the volcanic phenomena, the ash and pumice falls were the most destructive. These and the debris and pyroclastic flows devastated an area of about around Huaynaputina, and both crops and livestock sustained severe damage.

Between 11 and 17 villages within from the volcano were buried by the ash, including Calicanto, Chimpapampa, Cojraque, Estagagache, Moro Moro and San Juan de Dios south and southwest of Huaynaputina. The Huayruro Project began in 2015 and aims to rediscover these towns, and Calicanto was christened one of the 100

The eruption had a devastating impact on the region. Ash falls and pumice falls buried the surroundings beneath more than of rocks, while pyroclastic flows incinerated everything within their path, wiping out vegetation over a large area. Of the volcanic phenomena, the ash and pumice falls were the most destructive. These and the debris and pyroclastic flows devastated an area of about around Huaynaputina, and both crops and livestock sustained severe damage.

Between 11 and 17 villages within from the volcano were buried by the ash, including Calicanto, Chimpapampa, Cojraque, Estagagache, Moro Moro and San Juan de Dios south and southwest of Huaynaputina. The Huayruro Project began in 2015 and aims to rediscover these towns, and Calicanto was christened one of the 100 International Union of Geological Sciences

The International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) is an international non-governmental organization devoted to international cooperation in the field of geology.

About

The IUGS was founded in 1961 and is a Scientific Union member of the Int ...

heritage sites in 2021. The death toll in villages from toxic gases and ash fall was severe; reportedly, some villages lost their entire populations to the eruption and a priest visiting Omate after the eruption claimed to have "found its inhabitants dead and cooked with the fire of the burning stones". Estagagache has been deemed the "Pompeii

Pompeii (, ) was an ancient city located in what is now the ''comune'' of Pompei near Naples in the Campania region of Italy. Pompeii, along with Herculaneum and many villas in the surrounding area (e.g. at Boscoreale, Stabiae), was burie ...

of Peru".

The impact was noticeable in Arequipa, where up to of ash fell causing roofs to collapse under its weight. Ash fall was reported in an area of across Peru, Chile and Bolivia, mostly west and south from the volcano, including in La Paz

La Paz (), officially known as Nuestra Señora de La Paz (Spanish pronunciation: ), is the seat of government of the Plurinational State of Bolivia. With an estimated 816,044 residents as of 2020, La Paz is the third-most populous city in Bol ...

, Cuzco

Cusco, often spelled Cuzco (; qu, Qusqu ()), is a city in Southeastern Peru near the Urubamba Valley of the Andes mountain range. It is the capital of the Cusco Region and of the Cusco Province. The city is the seventh most populous in Peru; ...

, Camaná

Camaná is the district capital of the homonymous province, located in the Department of Arequipa, Peru. In 2015, it had an estimate of 39,026 inhabitants.

It lies 180 km from Arequipa, on the Panamerican Highway

The Pan-American Hig ...

, where it was thick enough to cause palm trees to collapse, Potosi, Arica

Arica ( ; ) is a commune and a port city with a population of 222,619 in the Arica Province of northern Chile's Arica y Parinacota Region. It is Chile's northernmost city, being located only south of the border with Peru. The city is the capita ...

as well as in Lima where it was accompanied by sounds of explosions. Ships observed ash fall from as far as west of the coast.

The surviving local population fled during the eruption and wild animals sought refuge in the city of Arequipa. The site of Torata Alta, a former Inka administrative centre, was destroyed during the Huaynaputina eruption and after a brief reoccupation abandoned in favour of Torata. Likewise, the occupation of the site of Pillistay close to Camana ended shortly after the eruption. Together with earthquakes unrelated to the eruption and El Niño

El Niño (; ; ) is the warm phase of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and is associated with a band of warm ocean water that develops in the central and east-central equatorial Pacific (approximately between the International Date ...

-related flooding, the Huaynaputina eruption led to the abandonment of some irrigated

Irrigation (also referred to as watering) is the practice of applying controlled amounts of water to land to help grow crops, landscape plants, and lawns. Irrigation has been a key aspect of agriculture for over 5,000 years and has been develo ...

land in Carrizal, Peru.

The eruption claimed 1,000–1,500 fatalities, not counting these from earthquakes or flooding on the Río Tambo. In Arequipa, houses and the cathedral

A cathedral is a church that contains the ''cathedra'' () of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually specific to those Christian denominations ...

collapsed during mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different ele ...

after an earthquake on 27February, concomitant with the beginning of the second stage of the eruption. Tsunami

A tsunami ( ; from ja, 津波, lit=harbour wave, ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and other underwater exp ...

s were reported during the eruption as well. Flooding ensued when volcanic dams in the Río Tambo broke, and debris and lahars

A lahar (, from jv, ꦮ꧀ꦭꦲꦂ) is a violent type of mudflow or debris flow composed of a slurry of pyroclastic material, rocky debris and water. The material flows down from a volcano, typically along a river valley.

Lahars are extremel ...

reached the Pacific Ocean 120–130 km () away. Occasionally the flows that reached the Pacific Ocean have been described as pyroclastic flows. Reportedly, fish were killed by the flood in the Pacific Ocean at the mouth of the river.

Damage to infrastructure and economic resources of the southern then-Viceroyalty of Peru

The Viceroyalty of Peru ( es, Virreinato del Perú, links=no) was a Spanish imperial provincial administrative district, created in 1542, that originally contained modern-day Peru and most of the Spanish Empire in South America, governed fro ...

was severe. The colonial wine industry in southern Peru was wiped out; chroniclers tell how all wines were lost during the eruption and the tsunamis that accompanied it. Before the eruption the Moquegua region had been a source of wine, and afterwards the focus of viticulture shifted to Pisco, Ica and Nazca; later sugarcane

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of (often hybrid) tall, perennial grass (in the genus '' Saccharum'', tribe Andropogoneae) that is used for sugar production. The plants are 2–6 m (6–20 ft) tall with stout, jointed, fibrous stalk ...

became an important crop in Moquegua valley. Tephra fallout fertilized the soil and may have allowed increased agriculture in certain areas. Cattle ranching

A ranch (from es, rancho/Mexican Spanish) is an area of land, including various structures, given primarily to ranching, the practice of raising grazing livestock such as cattle and sheep. It is a subtype of a farm. These terms are most ofte ...

also was severely impacted by the 1600 eruption. The Arequipa and Moquegua areas were depopulated by epidemics and famine; recovery only began towards the end of the 17th century. Indigenous people from the Quinistacas valley moved to Moquegua because the valley was covered with ash; population movements resulting from the Huaynaputina eruption may have occurred as far away as Bolivia. After the eruption, taxes were suspended for years, and indigenous workers were recruited from as far as Lake Titicaca

Lake Titicaca (; es, Lago Titicaca ; qu, Titiqaqa Qucha) is a large freshwater lake in the Andes mountains on the border of Bolivia and Peru. It is often called the highest navigable lake in the world. By volume of water and by surface area, i ...

and Cuzco to aid in the reconstruction. Arequipa went from being a relatively wealthy city to be a place of famine and disease in the years after the eruption, and its port of Chule was abandoned. Despite the damage, recovery was fast in Arequipa. The population declined in the region, although some of the decline may be due to earthquakes and epidemic

An epidemic (from Greek ἐπί ''epi'' "upon or above" and δῆμος ''demos'' "people") is the rapid spread of disease to a large number of patients among a given population within an area in a short period of time.

Epidemics of infectious ...

s before 1600. New administrative surveys – called – had to be carried out in the Colca Valley in 1604 after population losses and the effects of the Huaynaputina eruption had reduced the ability of the local population to pay the tribute

A tribute (; from Latin ''tributum'', "contribution") is wealth, often in kind, that a party gives to another as a sign of submission, allegiance or respect. Various ancient states exacted tribute from the rulers of land which the state conq ...

s.

Religious responses

Historians' writings about conditions in Arequipa tell of religious processions seeking to soothe the divine anger, people praying all day and those who had lost faith in the church resorting to magic spells as the eruption was underway, while in Moquegua children were reportedly running around, women screaming and numerous anecdotes of people who survived eruption or didn't exist. In the city of Arequipa church authorities organized a series ofprocession

A procession is an organized body of people walking in a formal or ceremonial manner.

History

Processions have in all peoples and at all times been a natural form of public celebration, as forming an orderly and impressive ceremony. Religious ...

s, requiem masses

A Requiem or Requiem Mass, also known as Mass for the dead ( la, Missa pro defunctis) or Mass of the dead ( la, Missa defunctorum), is a Mass of the Catholic Church offered for the repose of the soul or souls of one or more deceased persons, ...

and exorcism

Exorcism () is the religious or spiritual practice of evicting demons, jinns, or other malevolent spiritual entities from a person, or an area, that is believed to be possessed. Depending on the spiritual beliefs of the exorcist, this may be ...

s in response to the eruption. In Copacabana and La Paz, there were religious processions, the churches opened their doors and people prayed. Some indigenous people organized their own rituals which included feasting on whatever food and drink they had and battering dogs that were hanged alive. The apparent effectiveness of the Christian rituals led many previously hesitant indigenous inhabitants to embrace Christianity and abandon their clandestine native religion.

News of the event was propagated throughout the American colonies