Horatio Seymour 1868 presidential campaign on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In 1868, the Democrats nominated former

The 1868 election occurred three years after the end of the

The 1868 election occurred three years after the end of the

New York Governor

The governor of New York is the head of government of the U.S. state of New York. The governor is the head of the executive branch of New York's state government and the commander-in-chief of the state's military forces. The governor ha ...

Horatio Seymour

Horatio Seymour (May 31, 1810February 12, 1886) was an American politician. He served as Governor of New York from 1853 to 1854 and from 1863 to 1864. He was the Democratic Party nominee for president in the 1868 United States presidential elec ...

for President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

and Francis Preston Blair Jr.

Francis Preston Blair Jr. (February 19, 1821 – July 8, 1875) was a United States Senator, a United States Congressman and a Union Major General during the Civil War. He represented Missouri in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, a ...

(a Representative

Representative may refer to:

Politics

* Representative democracy, type of democracy in which elected officials represent a group of people

* House of Representatives, legislative body in various countries or sub-national entities

* Legislator, som ...

from Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

) for Vice President

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

. The Seymour-Blair ticket ran on a platform which supported national reconciliation and states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the ...

, opposed Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

, and opposed both Black equality and Black suffrage. Meanwhile, the Republican presidential ticket led by General Ulysses S. Grant benefited from Grant's status as a war hero (for winning the American Civil War) and ran on a pro-Reconstruction (and pro-Fourteenth Amendment) platform. Ultimately, the Seymour-Blair ticket ended up losing to the Republican ticket of General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

and House Speaker Schuyler Colfax

Schuyler Colfax Jr. (; March 23, 1823 – January 13, 1885) was an American journalist, businessman, and politician who served as the 17th vice president of the United States from 1869 to 1873, and prior to that as the 25th speaker of the Hous ...

in the 1868 U.S. presidential election.

Background

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

and less than a year after President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Andrew Johnson's impeachment (Johnson failed to get convicted by one vote). In addition, during the 1868 campaign season, the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified in order to secure basic rights for newly freed African-Americans. Some controversy was generated due to the fact that the Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

U.S. Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washin ...

made ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment a precondition for the former Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

states to rejoin the Union.

The run-up to the 1868 Democratic National Convention

After the 1866 elections, some prominent Democrats considered nominatingGeneral

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

Ulysses S. Grant as the Democratic nominee for U.S. president in 1868. However, this idea was dropped after Grant made it clear that he did not want to be associated with the Democratic Party. The Democrats then turned to their 1864 vice presidential nominee and former Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

Congressman George H. Pendleton

George Hunt Pendleton (July 19, 1825November 24, 1889) was an American politician and lawyer. He represented Ohio in both houses of Congress and was the unsuccessful Democratic nominee for Vice President of the United States in 1864.

After study ...

. Pendleton – the initial frontrunner for the 1868 Democratic presidential nomination – was a principled opponent of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

during the American Civil War, was noted for his intelligence and civility, and had a lot of support in the Western United States

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Far West, and the West) is the region comprising the westernmost states of the United States. As American settlement in the U.S. expanded westward, the meaning of the term ''the We ...

. What ultimately doomed Pendleton's bid was his "soft money views" and specifically his support of printing more money in order to spur inflation so that debtors can have some relief. Thus, some Democrats searched for a "hard money" alternative (specifically someone who supported the gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from the l ...

) to Pendleton – with Indiana Senator Thomas A. Hendricks

Thomas Andrews Hendricks (September 7, 1819November 25, 1885) was an American politician and lawyer from Indiana who served as the 16th governor of Indiana from 1873 to 1877 and the 21st vice president of the United States from March until his ...

being a possible contender for this role.

Another prominent candidate for the 1868 Democratic presidential nomination was Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase

Salmon Portland Chase (January 13, 1808May 7, 1873) was an American politician and jurist who served as the sixth chief justice of the United States. He also served as the 23rd governor of Ohio, represented Ohio in the United States Senate, a ...

. While Chase won the support of Democrats such as Congressmen S. S. "Sunset" Cox of New York and Daniel Voorhees of Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

, what ultimately doomed his bid was his support of Black manhood suffrage and other basic rights for African-Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of enslav ...

. Other Democratic presidential candidates in 1868 included Senator James Doolittle of Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

, Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

Joel Parker of New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

, Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

James English of Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its capita ...

, General Winfield Scott Hancock

Winfield Scott Hancock (February 14, 1824 – February 9, 1886) was a United States Army officer and the Democratic nominee for President of the United States in 1880. He served with distinction in the Army for four decades, including service ...

of Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

(who ultimately ended up becoming the Democratic presidential nominee in 1880

Events

January–March

* January 22 – Toowong State School is founded in Queensland, Australia.

* January – The international White slave trade affair scandal in Brussels is exposed and attracts international infamy.

* February � ...

), former Lieutenant Governor Sanford Church of New York, and former Congressman and railroad

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a pre ...

president Asa Packer

Asa Packer (December 29, 1805May 17, 1879) was an American businessman who pioneered railroad construction, was active in Pennsylvania politics, and founded Lehigh University. He was a conservative and religious man who reflected the image of th ...

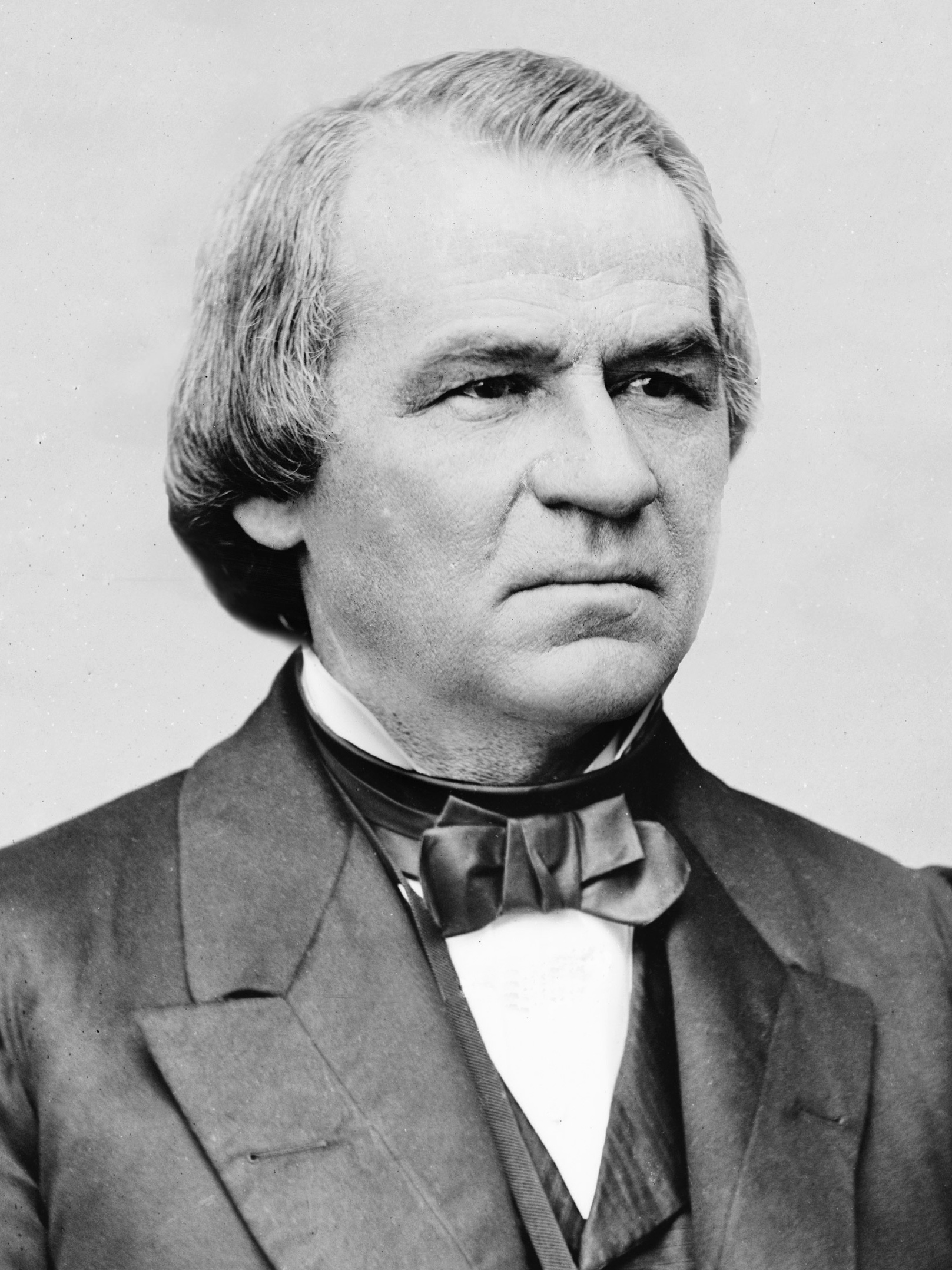

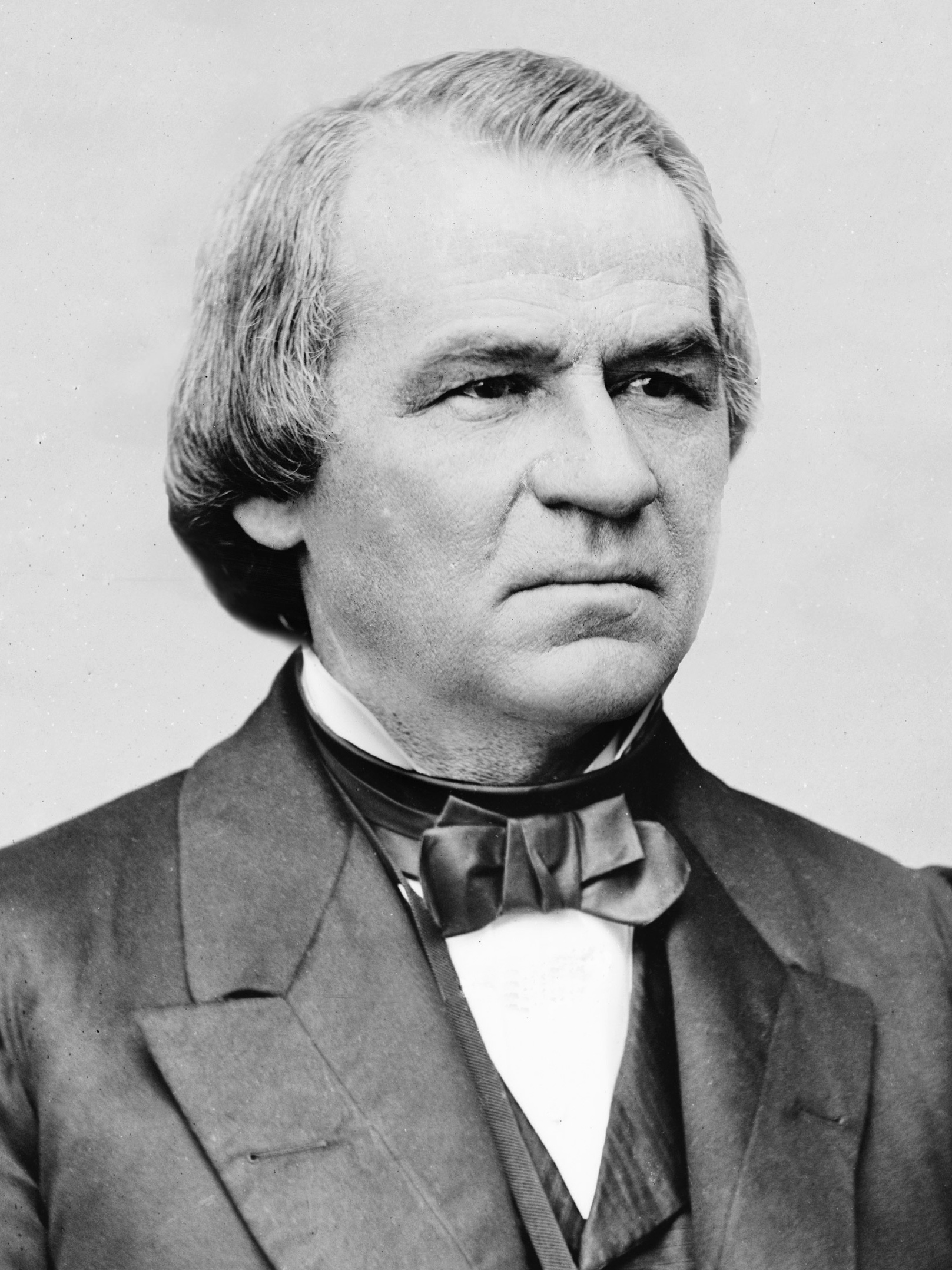

of Pennsylvania. In addition, incumbent U.S. President Andrew Johnson attempted to secure conservative support for getting the 1868 Democratic presidential nomination. However, many of President Johnson's initial supporters abandoned him as a result of his 1868 impeachment.

The 1868 Democratic National Convention

On July 4, 1868, the 1868 Democratic National Convention opened in the newTammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York City political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society. It became the main loc ...

building in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

. New York Governor Horatio Seymour, who first supported Thomas A. Hendricks and then Salmon P. Chase for the 1868 Democratic presidential nomination, was selected as the chairman of this convention. The 1868 Democratic Party platform accepted the demise of both slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

and secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics le ...

, but also demanded the end of Reconstruction by calling for the return of authority to the states, the non-renewal of the Freedmen’s Bureau

The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, usually referred to as simply the Freedmen's Bureau, was an agency of early Reconstruction, assisting freedmen in the South. It was established on March 3, 1865, and operated briefly as a ...

, amnesty for all former Confederates, and the withdrawal of the U.S. military from the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

. The platform also accused the Republicans – "the Radical party" – of violating the constitutional rights of the Southern states and of subjecting them to "military despotism and Negro supremacy."

On the first ballot, George Pendleton led with 105 votes to President Johnson's 65, Sanford Church's 34, and General Hancock's 33.5. For the next several ballots, Pendleton increased his support among the delegates while Hancock moved into a distant second place and while Hendricks moved into third place. Meanwhile, support for President Johnson dwindled until it disappeared on the 14th ballot. On the seventh and eighth ballots, Pendleton peaked at 156.5 delegates – which caused New York's delegation to switch their support from favorite son Sanford Church to Thomas Hendricks. As Pendleton's support collapsed, Hendricks took the lead for a while but was unable to sustain it after General Winfield Scott Hancock's home state of Pennsylvania added its delegates to his column – thus allowing Hancock to overtake Hendricks and to take the lead for the first time. Ultimately, Hancock led through the 21st ballot. Meanwhile, Salmon Chase’s name was put into nomination on the 17th ballot and George Pendleton’s name was withdrawn on the 18th ballot.

On the 22nd ballot, General George McCook nominated former New York Governor Horatio Seymour, causing spontaneous cheering and demonstrations of approval. Seymour did not want the nomination and thus declined it, but the delegates unanimously nominated him anyway. For Seymour's running mate, the delegates unanimously voted for Missouri Congressman Francis Preston Blair Jr.

Francis Preston Blair Jr. (February 19, 1821 – July 8, 1875) was a United States Senator, a United States Congressman and a Union Major General during the Civil War. He represented Missouri in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, a ...

(also known as Frank Blair Jr.).

Campaign

The 1868 Republican presidential nominee, General Ulysses S. Grant, did not openly campaign and instead left the job to surrogates. Grant's surrogates gave stumpspeeches

This list of speeches includes those that have gained notability in English or in English translation. The earliest listings may be approximate dates.

Before the 1st century

*c.570 BC : Gautama Buddha gives his first sermon at Sarnath

*431 ...

, circulated campaign pamphlets

A pamphlet is an unbound book (that is, without a hard cover or binding). Pamphlets may consist of a single sheet of paper that is printed on both sides and folded in half, in thirds, or in fourths, called a ''leaflet'' or it may consist of a ...

and political broadsides, rallied the voters with barbecues

Barbecue or barbeque (informally BBQ in the UK, US, and Canada, barbie in Australia and braai in South Africa) is a term used with significant regional and national variations to describe various cooking methods that use live fire and smoke t ...

and torchlight parades

A parade is a procession of people, usually organized along a street, often in costume, and often accompanied by marching bands, floats, or sometimes large balloons. Parades are held for a wide range of reasons, but are usually celebrations of ...

, and organized into pro-Grant clubs like the Tanners and the Boys in Blue. The Republicans based their campaign on being the party that saved the Union, ended slavery, and began reforming the South. They argued that the election of a Democratic president would result in gridlock which would hamper Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

. Meanwhile, the Democrats argued that Republicans were in favor of Black equality or even Black superiority not only in the Southern U.S., but throughout the entire United States. They also attacked the Republican-backed military rule in the Southern U.S. and argued that they were the only truly national party and thus the only party that could bring national reconciliation. The Democrats also attacked Grant as being "a besotted, uncouth, simple-minded, unprincipled, Negro-loving tyrant."

As a result of the Democrats' feeling of hopelessness, Horatio Seymour—the 1868 Democratic presidential nominee – engaged in a speaking tour near the end of the 1868 campaign. On October 21, Seymour spoke in Syracuse and later traveled to Buffalo, Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...

, Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Western Pennsylvania, the second-most populous city in Pennsylva ...

, Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

, Columbus

Columbus is a Latinized version of the Italian surname "''Colombo''". It most commonly refers to:

* Christopher Columbus (1451-1506), the Italian explorer

* Columbus, Ohio, capital of the U.S. state of Ohio

Columbus may also refer to:

Places ...

, Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at t ...

, Indianapolis, and Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

. However, the lackluster tone and repetitiveness of Seymour's speeches did not help his case (though these speeches were praised by Democratic newspapers

A newspaper is a periodical publication containing written information about current events and is often typed in black ink with a white or gray background.

Newspapers can cover a wide variety of fields such as politics, business, sports ...

) and it also did not help Seymour that his running mate Blair was a loose cannon who made various gaffes – such as predicting that a Grant Presidency would transform the U.S. into a military dictatorship.

Results

In the U.S. presidential election on November 3, 1868, Ulysses S. Grant defeated Horatio Seymour in the popular vote by a 53% to 47% margin and in the electoral vote by a margin of 214 to 80. 78% of the American electorate participated in this election – including 500,000 African-American men who voted for the first time in this election. While Seymour lost the election, there were some bright spots for him. Specifically, he won New Jersey, New York andOregon

Oregon () is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of its eastern boundary with Idaho. T ...

and almost won California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

. In addition, Seymour won Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, and Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent Del ...

. In addition, it is worth noting that Grant only managed to win the popular vote in 1868 as a result of Black suffrage. Historian Paul F. Boller Jr. wrote that " is apparent that if rant

A diatribe (from the Greek ''διατριβή''), also known less formally as rant, is a lengthy oration, though often reduced to writing, made in criticism of someone or something, often employing humor, sarcasm, and appeals to emotion.

His ...

had not won the 450,000 to 500,000 votes cast by the freedmen in the Southern states under military occupation, he would not have won his popular majority."

In spite of the fact that Grant won the 1868 election, the Republicans largely lost interest in Reconstruction within the next several years – thus paving the way for the eventual emergence of the Jim Crow South. On the bright side, the Republicans' victory (with the help of African-American voters) in 1868 motivated them to pass and ratify the Fifteenth Amendment which forbade discrimination in regards to the suffrage based on race, color, or former condition of servitude (though this Amendment was later largely circumvented in the former Confederate states through things such as poll taxes

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources.

Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments f ...

(including grandfather clauses) and literacy tests). This is a notable development since, just a couple of years earlier, Republicans had refused to guarantee African-American suffrage in the Fourteenth Amendment due to their belief and fear that this will prevent the Fourteenth Amendment from being ratified.

References

{{Democratic presidential campaigns Democratic Party (United States) presidential campaigns 1868 United States presidential election Democratic Party (United States) Aftermath of the American Civil War