Holodomor on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Holodomor ( uk, –ď–ĺ–Ľ–ĺ–ī–ĺ–ľ–ĺŐĀ—Ä, Holodomor, ; derived from uk, –ľ–ĺ—Ä–ł—ā–ł –≥–ĺ–Ľ–ĺ–ī–ĺ–ľ, lit=to kill by starvation, translit=moryty holodom, label=none), also known as the Terror-Famine or the Great Famine, was a man-made

According to a

According to a

Several repressive policies were implemented in Ukraine immediately preceding, during, and proceeding the famine, including but not limited to cultural-religious persecution the Law of Spikelets,

Several repressive policies were implemented in Ukraine immediately preceding, during, and proceeding the famine, including but not limited to cultural-religious persecution the Law of Spikelets,

Between January and mid-April 1933, a factor contributing to a surge of deaths within certain regions of Ukraine during the period was the relentless search for alleged hidden grain by the confiscation of all food stuffs from certain households, which Stalin implicitly approved of through a telegram he sent on the 1 January 1933 to the Ukrainian government reminding Ukrainian farmers of the severe penalties for not surrendering grain they may be hiding.

In order to make up for unfulfilled grain procurement quotas in Ukraine, reserves of grain were confiscated from three sources including, according to Oleh Wolowyna, "(a) grain set side for seed for the next harvest; (b) a grain fund for emergencies; (c) grain issued to collective farmers for previously completed work, which had to be returned if the collective farm did not fulfill its quota."

Between January and mid-April 1933, a factor contributing to a surge of deaths within certain regions of Ukraine during the period was the relentless search for alleged hidden grain by the confiscation of all food stuffs from certain households, which Stalin implicitly approved of through a telegram he sent on the 1 January 1933 to the Ukrainian government reminding Ukrainian farmers of the severe penalties for not surrendering grain they may be hiding.

In order to make up for unfulfilled grain procurement quotas in Ukraine, reserves of grain were confiscated from three sources including, according to Oleh Wolowyna, "(a) grain set side for seed for the next harvest; (b) a grain fund for emergencies; (c) grain issued to collective farmers for previously completed work, which had to be returned if the collective farm did not fulfill its quota."

The Soviet Union long denied that the famine had taken place. The

The Soviet Union long denied that the famine had taken place. The

A 2002 study by French demographer Jacques Vallin and colleagues utilising some similar primary sources to Kulchytsky, and performing an analysis with more sophisticated demographic tools with forward projection of expected growth from the 1926 census and backward projection from the 1939 census estimates the number of direct deaths for 1933 as 2.582 million. This number of deaths does not reflect the total demographic loss for Ukraine from these events as the fall of the birth rate during the crisis and the out-migration contribute to the latter as well. The total population shortfall from the expected value between 1926 and 1939 estimated by Vallin amounted to 4.566 million.

Of this number, 1.057 million is attributed to the birth deficit, 930,000 to forced out-migration, and 2.582 million to the combination of excess mortality and voluntary out-migration. With the latter assumed to be negligible, this estimate gives the number of deaths as the result of the 1933 famine about 2.2 million. According to demographic studies,

A 2002 study by French demographer Jacques Vallin and colleagues utilising some similar primary sources to Kulchytsky, and performing an analysis with more sophisticated demographic tools with forward projection of expected growth from the 1926 census and backward projection from the 1939 census estimates the number of direct deaths for 1933 as 2.582 million. This number of deaths does not reflect the total demographic loss for Ukraine from these events as the fall of the birth rate during the crisis and the out-migration contribute to the latter as well. The total population shortfall from the expected value between 1926 and 1939 estimated by Vallin amounted to 4.566 million.

Of this number, 1.057 million is attributed to the birth deficit, 930,000 to forced out-migration, and 2.582 million to the combination of excess mortality and voluntary out-migration. With the latter assumed to be negligible, this estimate gives the number of deaths as the result of the 1933 famine about 2.2 million. According to demographic studies,

Scholars continue to debate whether the man-made Soviet famine was a central act in a campaign of

Scholars continue to debate whether the man-made Soviet famine was a central act in a campaign of

Scholars consider Holodomor denial to be the assertion that the 1932‚Äď1933 famine in

Scholars consider Holodomor denial to be the assertion that the 1932‚Äď1933 famine in

On 10 November 2003 at the

On 10 November 2003 at the

Since 1998, Ukraine has officially observed a

Since 1998, Ukraine has officially observed a

File:Holodomor education van.jpg, A touring van devoted to Holodomor education, seen in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, 2017

File:HolodomorKyivSvichky.jpg, "Light the candle" event at a Holodomor memorial in Kyiv

File:HolodomorKharkiv.jpg, Memorial cross in

Original online issues for series: ::: ::: ::: ::: ::: ::: * * * * * * * * * * Liber, George. ''Total wars and the making of modern Ukraine, 1914‚Äď1954'' ( U of Toronto Press, 2016). * * * * * * * * * (A collection of Mace's articles and columns published in ''Den (newspaper), Den'' from 1993 to 2004). * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ::: * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * , author-link=U.S. Commission on the Ukraine Famine, editor1-link=James Mace ::: ::: ::: * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Findings of the Commission on the Ukraine Famine

(Report to Congress). *

(Script text.)

* * *

Famine in Ukraine 1932‚Äď1933

at the Central State Archive of Ukraine

photoslinks

* * Stanislav Kulchytsky's articles in Dzerkalo Tyzhnia, Kyiv, Ukraine ** ''"How many of us perish in Holodomor on 1933"'', 23 November 2002 ‚Äď 29 November 2002

Available online

** ''"Reasons of the 1933 famine in Ukraine. Through the pages of one almost forgotten book"'' 16‚Äď22 August 2003

** ''"Reasons of the 1933 famine in Ukraine-2"'', 4 October 2003 ‚Äď 10 October 2003

** ''"Demographic losses in Ukraine in the twentieth century"'', 2 October 2004 ‚Äď 8 October 2004

Revelations from the Russian Archives at the Library of Congress * Sergei Melnikoff

Photos of Holodomor

''gulag.ipvnews.org''

''www.un.org'' * Nicolas Werth [http://www.massviolence.org/The-1932-1933-Great-Famine-in-Ukraine?artpage=1-5 Case Study: The Great Ukrainian Famine of 1932‚Äď1933] / CNRSFrance

HolodomorFamine in Soviet Ukraine 1932‚Äď1933

archived from ''kiev.usembassy.gov''

Famine in the Soviet Union 1929‚Äď1934

ollection of archive materials ''rusarchives.ru''

Holodomor: The Secret Holocaust in Ukraine

fficial site of the Security Service of Ukraine, ''www.sbu.gov.ua''

CBC program about the Great Hunger

archived from ''www.cbc.ca'' *

archived from ''www.narodnaviyna.org.ua'' * Oksana Kis

Defying Death Women's Experience of the Holodomor, 1932‚Äď1933

''www.academia.edu'' {{Authority control Holodomor, Genocides in Europe 1932 disasters in Europe 1932 in the Soviet Union 1932 in Ukraine 1933 disasters in Europe 1933 in the Soviet Union 1933 in Ukraine Agriculture in the Soviet Union Agriculture in Ukraine Anti-Ukrainian sentiment Crimes of the communist regime in Ukraine against Ukrainians Famines in Europe Famines in the Soviet Union Incidents of cannibalism Joseph Stalin Stalinism in Ukraine 20th-century famines Famines in Ukraine 1932 disasters in the Soviet Union 1933 disasters in the Soviet Union

famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including war, natural disasters, crop failure, population imbalance, widespread poverty, an economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenomenon is usually accompan ...

in Soviet Ukraine

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, –£–ļ—Ä–į—óŐĀ–Ĺ—Ā—Ć–ļ–į –†–į–ī—ŹŐĀ–Ĺ—Ā—Ć–ļ–į –°–ĺ—Ü—Ė–į–Ľ—Ė—Ā—ā–łŐĀ—á–Ĺ–į –†–Ķ—Ā–Ņ—ÉŐĀ–Ī–Ľ—Ė–ļ–į, ; russian: –£–ļ—Ä–į–łŐĀ–Ĺ—Ā–ļ–į—Ź –°–ĺ–≤–ĶŐĀ—ā—Ā–ļ–į—Ź –°–ĺ—Ü–ł–į–Ľ–ł—Ā—ā–łŐĀ—á–Ķ—Ā–ļ–į—Ź –†–Ķ—Ā–Ņ ...

from 1932 to 1933 that killed millions of Ukrainians

Ukrainians ( uk, –£–ļ—Ä–į—ó–Ĺ—Ü—Ė, Ukraintsi, ) are an East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. They are the seventh-largest nation in Europe. The native language of the Ukrainians is Ukrainian. The majority of Ukrainians are Eastern Ort ...

. The Holodomor was part of the wider Soviet famine of 1932‚Äď1933 which affected the major grain-producing areas of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

.

While scholars universally agree that the cause of the famine was man-made, whether the Holodomor constitutes a genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people‚ÄĒusually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group‚ÄĒin whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the ...

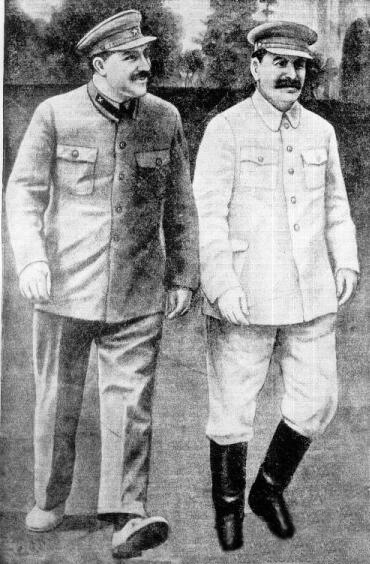

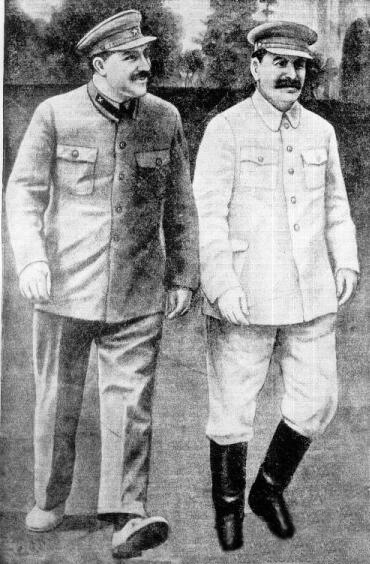

remains in dispute. Some historians conclude that the famine was planned and exacerbated by Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; ‚Äď 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

in order to eliminate a Ukrainian independence movement. This conclusion is supported by Raphael Lemkin. Others suggest that the famine arose because of rapid Soviet industrialisation and collectivization of agriculture.

Ukraine was one of the largest grain-producing states in the USSR and was subject to unreasonably higher grain quotas, when compared to the rest of the country. This caused Ukraine to be hit particularly hard by the famine. Early estimates of the death toll by scholars and government officials vary greatly. A joint statement to the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

signed by 25 countries in 2003 declared that 7‚Äď10 million died. However, current scholarship estimates a range significantly lower, with 3.5 to 5 million victims. The famine's widespread impact on Ukraine persists to this day.

Since 2006, the Holodomor has been recognized by the European Parliament

The European Parliament (EP) is one of the Legislature, legislative bodies of the European Union and one of its seven Institutions of the European Union, institutions. Together with the Council of the European Union (known as the Council and in ...

, Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, –£–ļ—Ä–į—ó–Ĺ–į, Ukra√Įna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

alongside 22 countries, as a genocide against the Ukrainian people carried out by the Soviet regime.

Etymology

''Holodomor'' literally translated fromUkrainian

Ukrainian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Ukraine

* Something relating to Ukrainians, an East Slavic people from Eastern Europe

* Something relating to demographics of Ukraine in terms of demography and population of Ukraine

* So ...

means "death by hunger", "killing by hunger, killing by starvation", or sometimes "murder by hunger or starvation." It is a compound of the Ukrainian uk, holod, lit= hunger, label=none, italic=yes; and uk, mor, lit=plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pes ...

, label=none, italic=yes. The expression uk, holodom moryty , lit=, label=none, italic=yes means "to inflict death by hunger." The Ukrainian verb uk, moryty, lit=, label=none, italic=yes ( uk, –ľ–ĺ—Ä–ł—ā–ł, lit=, label=none, italic=) means "to poison, to drive to exhaustion, or to torment." The perfective form of uk, moryty, lit=, label=none, italic=yes is uk, zamoryty, lit=kill or drive to death, label=none, italic=yes In English, the Holodomor has also been referred to as the ''artificial famine'', ''famine genocide'', ''terror famine'', and ''terror-genocide''.

It was used in print in the 1930s in Ukrainian diaspora publications in Czechoslovakia

, rue, –ß–Ķ—Ā—Ć–ļ–ĺ—Ā–Ľ–ĺ–≤–Ķ–Ĺ—Ć—Ā–ļ–ĺ, , yi, ◊ė◊©◊Ę◊õ◊ź◊°◊ú◊ź◊ē◊ē◊ź◊ß◊ô◊ô,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918‚Äď19391945‚Äď1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

as ''Haladamor'', and by Ukrainian immigrant organisations in the United States and Canada by 1978; in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, of which Ukraine was a constituent republic

Administrative division, administrative unit,Article 3(1). country subdivision, administrative region, subnational entity, constituent state, as well as many similar terms, are generic names for geographical areas into which a particular, ind ...

, any references to the famine were dismissed as anti-Soviet propaganda, even after de-Stalinization in 1956, until the declassification and publication of historical documents in the late 1980s made continued denial of the catastrophe unsustainable

Discussion of the Holodomor became possible as part of the '' glasnost'' policy of openness. In Ukraine, the first official use of ''famine'' was a December 1987 speech by Volodymyr Shcherbytskyi, First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, on the occasion of the republic's 70th anniversary. Another early public usage in the Soviet Union was in a February 1988 speech by Oleksiy Musiyenko, Deputy Secretary for ideological matters of the party organisation of the Kyiv branch of the Union of Soviet Writers in Ukraine.

The term ''holodomor'' may have first appeared in print in the Soviet Union on 18 July 1988, when Musiyenko's article on the topic was published. ''Holodomor'' is now an entry in the modern, two-volume dictionary of the Ukrainian language, published in 2004, described as "artificial hunger, organised on a vast scale by a criminal regime

In politics, a regime (also "régime") is the form of government or the set of rules, cultural or social norms, etc. that regulate the operation of a government or institution and its interactions with society. According to Yale professor Juan Jo ...

against a country's population."

According to Elazar Barkan, Elizabeth A. Cole, and Kai Struve, the Holodomor has been described as a “Ukrainian Holocaust". They assert that since the 1990s the term ''Holodomor'' has been widely adopted by anti-communists in order to draw parallels to the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europ ...

. However this term has been criticized by some academics, as the Holocaust was a heavily documented, coordinated effort by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and its collaborators to eliminate certain ethnic groups such as Jews, Slavs, and Romani, ultimately killing 11 million people. By contrast, the Holodomor does not have definitive documentation that Stalin directly ordered the mass murder of Ukrainians. Barkan et al. state that the term ''Holodomor'' was "introduced and popularized by the Ukrainian diaspora in North America before Ukraine became independent" and that the term 'Holocaust' in reference to the famine "is not explained at all."

History

Scope and duration

The famine affected the Ukrainian SSR as well as the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (a part of theUkrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, –£–ļ—Ä–į—óŐĀ–Ĺ—Ā—Ć–ļ–į –†–į–ī—ŹŐĀ–Ĺ—Ā—Ć–ļ–į –°–ĺ—Ü—Ė–į–Ľ—Ė—Ā—ā–łŐĀ—á–Ĺ–į –†–Ķ—Ā–Ņ—ÉŐĀ–Ī–Ľ—Ė–ļ–į, ; russian: –£–ļ—Ä–į–łŐĀ–Ĺ—Ā–ļ–į—Ź –°–ĺ–≤–ĶŐĀ—ā—Ā–ļ–į—Ź –°–ĺ—Ü–ł–į–Ľ–ł—Ā—ā–łŐĀ—á–Ķ—Ā–ļ–į—Ź –†–Ķ—Ā–Ņ ...

at the time) in spring 1932, and from February to July 1933, with the most victims recorded in spring 1933. The consequences are evident in demographic statistics: between 1926 and 1939, the Ukrainian population increased by only 6.6%, whereas Russia and Belarus grew by 16.9% and 11.7%, respectively.

From the 1932 harvest, Soviet authorities were able to procure only 4.3 million tons as compared with 7.2 million tons obtained from the 1931 harvest. Rations in towns were drastically cut back, and in winter 1932‚Äď1933 and spring 1933, people in many urban areas starved. Urban workers were supplied by a rationing system and therefore could occasionally assist their starving relatives in the countryside, but rations were gradually cut. By spring 1933, urban residents also faced starvation. At the same time, workers were shown agitprop

Agitprop (; from rus, –į–≥–ł—ā–Ņ—Ä–ĺ–Ņ, r=agitpr√≥p, portmanteau of ''agitatsiya'', "agitation" and ''propaganda'', " propaganda") refers to an intentional, vigorous promulgation of ideas. The term originated in Soviet Russia where it referred ...

movies depicting peasants as counterrevolutionaries who hid grain and potatoes at a time when workers, who were constructing the "bright future" of socialism, were starving.

The first reports of mass malnutrition

Malnutrition occurs when an organism gets too few or too many nutrients, resulting in health problems. Specifically, it is "a deficiency, excess, or imbalance of energy, protein and other nutrients" which adversely affects the body's tissues ...

and deaths from starvation emerged from two urban areas of the city of Uman

Uman ( uk, –£–ľ–į–Ĺ—Ć, ; pl, HumaŇĄ; yi, ◊ź◊ē◊ě◊ź÷∑◊ü) is a city located in Cherkasy Oblast in central Ukraine, to the east of Vinnytsia. Located in the historical region of the eastern Podolia, the city rests on the banks of the Umanka River ...

, reported in January 1933 by Vinnytsia and Kyiv

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

oblast

An oblast (; ; Cyrillic (in most languages, including Russian and Ukrainian): , Bulgarian: ) is a type of administrative division of Belarus, Bulgaria, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, and Ukraine, as well as the Soviet Union and the Kingdo ...

s. By mid-January 1933, there were reports about mass "difficulties" with food in urban areas, which had been undersupplied through the rationing system, and deaths from starvation among people who were refused rations, according to the December 1932 decree of the Central Committee of the Ukrainian Communist Party

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known as ...

. By the beginning of February 1933, according to reports from local authorities and Ukrainian GPU (secret police), the most affected area was Dnipropetrovsk Oblast

Dnipropetrovsk Oblast ( uk, –Ē–Ĺ—Ė–Ņ—Ä–ĺ–Ņ–Ķ—ā—Ä–ĺŐĀ–≤—Ā—Ć–ļ–į –ĺŐĀ–Ī–Ľ–į—Ā—ā—Ć, translit=Dnipropetrovska oblast), also referred to as Dnipropetrovshchyna ( uk, –Ē–Ĺ—Ė–Ņ—Ä–ĺ–Ņ–Ķ—ā—Ä–ĺŐĀ–≤—Č–ł–Ĺ–į), is an oblast (province) of central-eastern Ukr ...

, which also suffered from epidemics of typhus and malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

. Odessa and Kyiv oblasts were second and third, respectively. By mid-March, most of the reports of starvation originated from Kyiv Oblast.

By mid-April 1933, Kharkov Oblast reached the top of the most affected list, while Kiev, Dnipropetrovsk, Odessa, Vinnytsia, and Donetsk oblasts, and Moldavian SSR were next on the list. Reports about mass deaths from starvation, dated mid-May through the beginning of June 1933, originated from raion

A raion (also spelt rayon) is a type of administrative unit of several post-Soviet states. The term is used for both a type of subnational entity and a division of a city. The word is from the French (meaning 'honeycomb, department'), and is c ...

s in Kiev and Kharkov oblasts. The "less affected" list noted Chernihiv Oblast

Chernihiv Oblast ( uk, –ß–Ķ—Ä–Ĺ—ĖŐĀ–≥—Ė–≤—Ā—Ć–ļ–į –ĺŐĀ–Ī–Ľ–į—Ā—ā—Ć, translit=Chernihivska oblast; also referred to as Chernihivshchyna, uk, –ß–Ķ—Ä–Ĺ—ĖŐĀ–≥—Ė–≤—Č–ł–Ĺ–į, translit=Chernihivshchyna) is an oblast (province) of northern Ukraine. T ...

and northern parts of Kyiv and Vinnytsia oblasts. The Central Committee of the CP(b) of Ukraine Decree of 8 February 1933 said no hunger cases should have remained untreated. '' The Ukrainian Weekly'', which was tracking the situation in 1933, reported the difficulties in communications and the appalling situation in Ukraine.

Local authorities had to submit reports about the numbers suffering from hunger, the reasons for hunger, number of deaths from hunger, food aid provided from local sources, and centrally provided food aid required. The GPU managed parallel reporting and food assistance in the Ukrainian SSR. Many regional reports and most of the central summary reports are available from present-day central and regional Ukrainian archives.

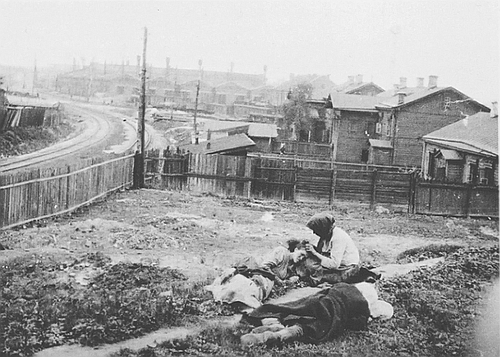

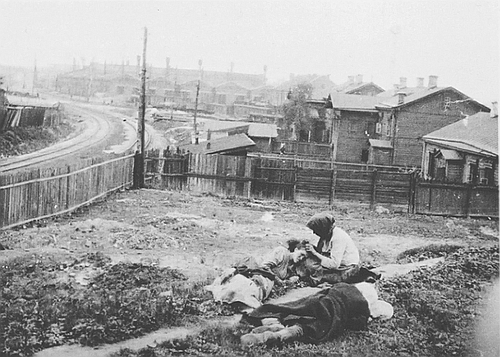

Cannibalism

Evidence of widespread cannibalism was documented during the Holodomor:Survival was a moral as well as a physical struggle. A woman doctor wrote to a friend in June 1933 that she had not yet become a cannibal, but was "not sure that I shall not be one by the time my letter reaches you." The good people died first. Those who refused to steal or toThe Soviet regime printed posters declaring: "To eat your own children is a barbarian act." More than 2,500 people were convicted of cannibalism during the Holodomor.prostitute Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in Sex work, sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, n ...themselves died. Those who gave food to others died. Those who refused to eatcorpses A cadaver or corpse is a dead human body that is used by medical students, physicians and other scientists to study anatomy, identify disease sites, determine causes of death, and provide tissue to repair a defect in a living human being. Stu ...died. Those who refused to kill their fellow man died. Parents who resisted cannibalism died before their children did.

Causes

The overlying causes for the famine are still disputed. Some scholars suggest that the famine was a consequence of man-made and natural factors. The most prevalent man-made factor was the economic problems associated with changes implemented during the period of Soviet industrialisation. There are also those who blame a systematic set of policies perpetrated by the Soviet government under Stalin designed to exterminate the Ukrainians. According to historian Stephen G. Wheatcroft, the grain yield for the Soviet Union preceding the famine was a low harvest of between 55 and 60 million tons, likely in part caused by damp weather and low traction power, yet official statistics mistakenly reported a yield of 68.9 million tons. Historian Mark Tauger has suggested that drought and damp weather were a causes of the low harvest. Mark Tauger suggested that heavy rains would help the harvest while Stephen Wheatcroft suggested it would hurt it which Natalya Naumenko notes as a disagreement in scholarship. Another factor which reduced the harvest suggested by Tauger included endemic plant rust. However in regard to plant disease Stephen Wheatcroft notes that the Soviet extension of sown area may have exacerbated the problem. According to Natalya Naumenko, collectivization in the Soviet Union and lack of favored industries were primary contributors to famine mortality (52% of excess deaths), and some evidence shows there was discrimination against ethnic Ukrainians and Germans. Lewis H. Siegelbaum, Professor of History at Michigan State University, states that Ukraine was hit particularly hard by grain quotas which were set at levels which most farms could not produce. The 1933 harvest was poor, coupled with the extremely high quota level, which led to starvation conditions. The shortages were blamed on kulak sabotage, and authorities distributed what supplies were available only in the urban areas. According to a

According to a Centre for Economic Policy Research

The Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) is an independent, non‚Äźpartisan, pan‚ÄźEuropean non‚Äźprofit organisation. Its mission is to enhance the quality of policy decisions through providing policy‚Äźrelevant research, based soundly in e ...

paper published in 2021 by Andrei Markevich, Natalya Naumenko, and Nancy Qian, regions with higher Ukrainian population shares were struck harder with centrally planned policies corresponding to famine such as increased procurement rate, and Ukrainian populated areas were given lower amounts of tractors which the paper argues demonstrates that ethnic discrimination across the board was centrally planned, ultimately concluding that 92% of famine deaths in Ukraine alone along with 77% of famine deaths in Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus combined can be explained by systematic bias against Ukrainians.

The collectivization and high procurement quota explanation for the famine is somewhat called into question by the fact that the oblasts of Ukraine with the highest losses being Kyiv

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

and Kharkiv

Kharkiv ( uk, –•–įŐĀ—Ä–ļ—Ė–≤, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: –•–į—Ä—Ć–ļo–≤, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine.

which produced far lower amounts of grain than other sections of the country. Oleh Wolowyna comments that peasant resistance and the ensuing repression of said resistance was a critical factor for the famine in Ukraine and parts of Russia populated by national minorities like Germans and Ukrainians allegedly tainted by "fascism and bourgeois nationalism" according to Soviet authorities.

In Ukraine collectivisation policy was enforced, entailing extreme crisis and contributing to the famine. In 1929‚Äď1930, peasants were induced to transfer land and livestock to state-owned farms, on which they would work as day-labourers for payment in kind. Collectivization in the Soviet Union, including the Ukrainian SSR, was not popular among the peasantry, and forced collectivisation led to numerous peasant revolts. The first five-year plan changed the output expected from Ukrainian farms, from the familiar crop of grain to unfamiliar crops like sugar beet

A sugar beet is a plant whose root contains a high concentration of sucrose and which is grown commercially for sugar production. In plant breeding, it is known as the Altissima cultivar group of the common beet ('' Beta vulgaris''). Together ...

s and cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

. In addition, the situation was exacerbated by poor administration of the plan and the lack of relevant general management. Significant amounts of grain remained unharvested, and‚ÄĒeven when harvested‚ÄĒa significant percentage was lost during processing, transportation, or storage.

In the summer of 1930, the government instituted a program of food requisitioning, ostensibly to increase grain exports. Food theft was made punishable by death or 10 years imprisonment. Food exports continued during the famine, albeit at a reduced rate. In regard to exports, Michael Ellman states that the 1932‚Äď1933 grain exports amounted to 1.8 million tonnes, which would have been enough to feed 5 million people for one year.

It has been proposed that the Soviet leadership used the man-made famine to attack Ukrainian nationalism

Ukrainian nationalism refers to the promotion of the unity of Ukrainians as a people and it also refers to the promotion of the identity of Ukraine as a nation state. The nation building that arose as nationalism grew following the French ...

, and thus it could fall under the legal definition of genocide. For example, special and particularly lethal policies were adopted in and largely limited to Soviet Ukraine at the end of 1932 and 1933. According to Timothy Snyder, "each of them may seem like an anodyne administrative measure, and each of them was certainly presented as such at the time, and yet each had to kill."

Under the collectivism policy, for example, farmers were not only deprived of their properties but a large swath of these were also exiled in Siberia with no means of survival. Those who were left behind and attempted to escape the zones of famine were ordered to be shot. There were foreign individuals who witnessed this atrocity and its effects. For example, the account of Arthur Koestler

Arthur Koestler, (, ; ; hu, K√∂sztler Art√ļr; 5 September 1905 ‚Äď 1 March 1983) was a Hungarian-born author and journalist. Koestler was born in Budapest and, apart from his early school years, was educated in Austria. In 1931, Koestler join ...

, a Hungarian-British journalist, described the peak years of Holodomor in these words:At everyrain Rain is water droplets that have condensed from atmospheric water vapor and then fall under gravity. Rain is a major component of the water cycle and is responsible for depositing most of the fresh water on the Earth. It provides water f ...station there was a crowd of peasants in rags, offering icons and linen in exchange for a loaf of bread. The women were lifting up their infants to the compartment windows‚ÄĒinfants pitiful and terrifying with limbs like sticks, puffed bellies, big cadaverous heads lolling on thin necks.

Regional variation

The collectivization and high procurement quota explanation for the famine is called into question by the fact that the oblasts of Ukraine with the highest losses beingKyiv

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

and Kharkiv

Kharkiv ( uk, –•–įŐĀ—Ä–ļ—Ė–≤, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: –•–į—Ä—Ć–ļo–≤, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine.

which produced far lower amounts of grain than other sections of the country. A potential explanation for this was that Kharkiv and Kyiv fulfilled and over fulfilled their grain procurements in 1930 which led to raions in these Oblasts having their procurement quotas doubled in 1931 compared to the national average increase in procurement rate of 9%. While Kharkiv and Kyiv had their quotas increased, the Odesa oblast and some raions of Dnipropetrovsk oblast had their procurement quotas decreased.

According to Nataliia Levchuk of the Ptoukha Institute of Demography and Social Studies, "the distribution of the largely increased 1931 grain quotas in Kharkiv and Kyiv oblasts by raion was very uneven and unjustified because it was done disproportionally to the percentage of wheat sown area and their potential grain capacity.‚ÄĚ

Repressive policies

Several repressive policies were implemented in Ukraine immediately preceding, during, and proceeding the famine, including but not limited to cultural-religious persecution the Law of Spikelets,

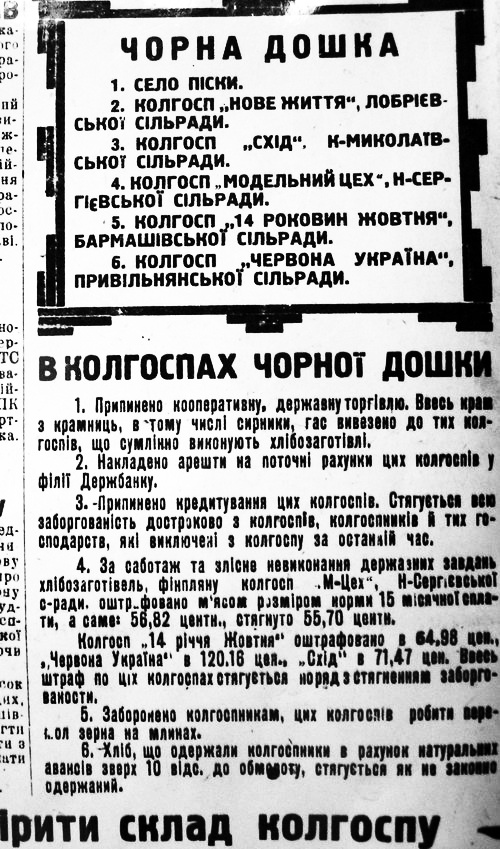

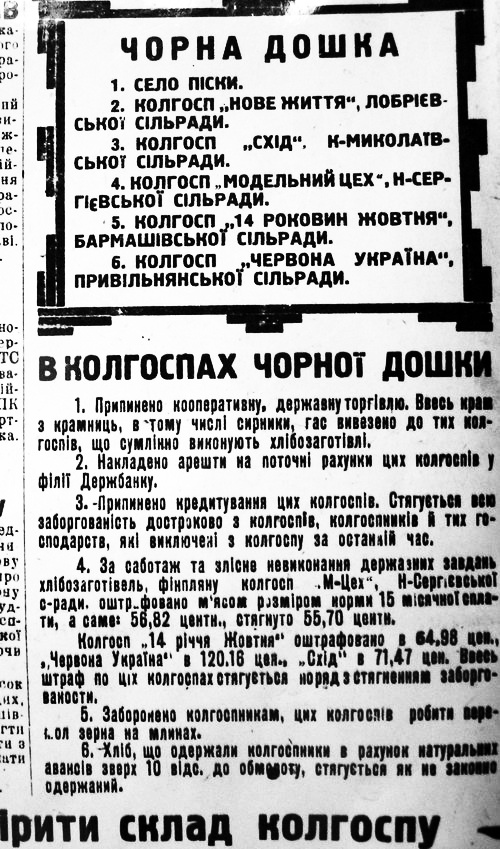

Several repressive policies were implemented in Ukraine immediately preceding, during, and proceeding the famine, including but not limited to cultural-religious persecution the Law of Spikelets, Blacklisting

Blacklisting is the action of a group or authority compiling a blacklist (or black list) of people, countries or other entities to be avoided or distrusted as being deemed unacceptable to those making the list. If someone is on a blacklist, t ...

, the internal passport system, and harsh grain requisitions.Preceding the famine

Coiner of the termgenocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people‚ÄĒusually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group‚ÄĒin whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the ...

, Raphael Lemkin considered the repression of the Orthodox Church to be a prong of genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people‚ÄĒusually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group‚ÄĒin whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the ...

against Ukrainians when seen in correlation to the Holodomor famine. Collectivization did not just entail the acquisition of land from farmers but also the closing of churches, burning of icons, and the arrests of priests. Associating the church with the tsarist regime, the Soviet state continued to undermine the church through expropriations and repression. They cut off state financial support to the church and secularized church schools. By early 1930 75% of the Autocephalist parishes in Ukraine were persecuted by Soviet authorities. The GPU instigated a show trial which denounced the Orthodox Church in Ukraine as a "nationalist, political, counter-revolutionary organization" and instigated a staged "self-dissolution." However the Church was later allowed to reorganize in December 1930 under a pro-Soviet cosmopolitan leader of Ivan Pavlovsky

Ivan Grigorievich Pavlovsky (Russian:–ė–≤–įŐĀ–Ĺ –ď—Ä–ł–≥–ĺŐĀ—Ä—Ć–Ķ–≤–ł—á –ü–į–≤–Ľ–ĺŐĀ–≤—Ā–ļ–ł–Ļ) (February 11 (24) 1909 - April 27 1999) was a Soviet military leader, Commander-in-Chief Soviet Ground Forces, Ground Forces - Deputy Minister of Defe ...

yet purges of the Church reignited during the Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: –Ď–ĺ–Ľ—Ć—ą–ĺ–Ļ —ā–Ķ—Ä—Ä–ĺ—Ä), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-–Ļ –≥–ĺ–ī, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secreta ...

.

Changes in cultural politics also occurred. An early example was the 1930 show trial of the "Union for the Freedom of Ukraine" at which 45 intellectuals, higher education professors, writers, a theologian and a priest were publicly prosecuted in Kharkiv

Kharkiv ( uk, –•–įŐĀ—Ä–ļ—Ė–≤, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: –•–į—Ä—Ć–ļo–≤, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine.

, then capital of Soviet Ukraine. Fifteen of the accused were executed, many more with links to the defendants (248) were sent to the camps. (This was one of a series of contemporary show trials, held in the North Caucasus, 1929 in Shakhty, and in Moscow, the 1930 Industrial Party Trial and the 1931 Menshevik Trial The Menshevik Trial was one of the early purges carried out by Stalin in which 14 economists, who were former members of the Menshevik party, were put on trial and convicted for trying to re-establish their party as the "Union Bureau of the Menshev ...

.) The total number is not known, but tens of thousands of people are estimated to have been arrested, exiled, and/or executed during and after the trial including 30,000 intellectuals, writers, teachers, and scientists. In this vein the secretary of the Kharkiv Oblast referred to "bourgeois-nationalistic rabble" as "class enemies" near the end of the famine.

During the famine

The "Decree About the Protection of Socialist Property", nicknamed by the farmers the Law of Spikelets, was enacted on 7 August 1932. The purpose of the law was to protect the property of the kolkhoz collective farms. It was nicknamed the Law of Spikelets because it allowed people to be prosecuted for gleaning leftover grain from the fields. There were more than 200,000 people sentenced under this law. The blacklist system was formalized in 1932 by the November 20 decree "The Struggle against Kurkul Influence in Collective Farms"; blacklisting, synonymous with a board of infamy, was one of the elements of agitation-propaganda in theSoviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, and especially Ukraine and the ethnically Ukrainian Kuban region in the 1930s. A blacklisted collective farm, village, or raion

A raion (also spelt rayon) is a type of administrative unit of several post-Soviet states. The term is used for both a type of subnational entity and a division of a city. The word is from the French (meaning 'honeycomb, department'), and is c ...

(district) had its monetary loans and grain advances called in, stores closed, grain supplies, livestock, and food confiscated as a penalty, and was cut off from trade. Its Communist Party and collective farm committees were purged and subject to arrest, and their territory was forcibly cordoned off by the OGPU secret police.

Although nominally targeting collective farms failing to meet grain quotas and independent farmers with outstanding tax-in-kind, in practice the punishment was applied to all residents of affected villages and raions, including teachers, tradespeople, and children. In the end 37 out of 392 districts along with at least 400 collective farms where put on the "black board" in Ukraine, more than half of the blacklisted farms being in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast

Dnipropetrovsk Oblast ( uk, –Ē–Ĺ—Ė–Ņ—Ä–ĺ–Ņ–Ķ—ā—Ä–ĺŐĀ–≤—Ā—Ć–ļ–į –ĺŐĀ–Ī–Ľ–į—Ā—ā—Ć, translit=Dnipropetrovska oblast), also referred to as Dnipropetrovshchyna ( uk, –Ē–Ĺ—Ė–Ņ—Ä–ĺ–Ņ–Ķ—ā—Ä–ĺŐĀ–≤—Č–ł–Ĺ–į), is an oblast (province) of central-eastern Ukr ...

alone. Every single raion in Dnipropetrovsk had at least one blacklisted village, and in Vinnytsia oblast five entire raions were blacklisted. This oblast is situated right in the middle of traditional lands of the Zaporizhian Cossacks. Cossack villages were also blacklisted in the Volga and Kuban regions of Russia. In 1932, 32 (out of less than 200) districts in Kazakhstan that did not meet grain production quotas were blacklisted. Some blacklisted areas in Kharkiv

Kharkiv ( uk, –•–įŐĀ—Ä–ļ—Ė–≤, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: –•–į—Ä—Ć–ļo–≤, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine.

could have death rates exceeding 40% while in other areas such as Vinnytsia blacklisting had no particular effect on mortality.

The passport system in the Soviet Union (identity cards) was introduced on 27 December 1932 to deal with the exodus of peasants from the countryside. Individuals not having such a document could not leave their homes on pain of administrative penalties, such as internment in labour camp

A labor camp (or labour camp, see spelling differences) or work camp is a detention facility where inmates are forced to engage in penal labor as a form of punishment. Labor camps have many common aspects with slavery and with prisons (espe ...

s (Gulag

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the State Political Directorate, GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= ...

). Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; ‚Äď 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

signed the January 1933 secret decree named "Preventing the Mass Exodus of Peasants who are Starving", restricting travel by peasants after requests for bread began in the Kuban and Ukraine; Soviet authorities blamed the exodus of peasants during the famine on anti-Soviet elements, saying that "like the outflow from Ukraine last year, was organized by the enemies of Soviet power."

There was a wave of migration due to starvation and authorities responded by introducing a requirement that passports be used to go between republics and banning travel by rail. During March of 1933 GPU reported that 219,460 people were either intercepted and escorted back or arrested at it's checkpoints meant to prevent movement of peasants between districts. It has been estimated that there were some 150,000 excess deaths as a result of this policy, and one historian asserts that these deaths constitute a crime against humanity

Crimes against humanity are widespread or systemic acts committed by or on behalf of a ''de facto'' authority, usually a state, that grossly violate human rights. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity do not have to take place within the ...

. In contrast, historian Stephen Kotkin argues that the sealing of the Ukrainian borders caused by the internal passport system was in order to prevent the spread of famine-related diseases.

Between January and mid-April 1933, a factor contributing to a surge of deaths within certain regions of Ukraine during the period was the relentless search for alleged hidden grain by the confiscation of all food stuffs from certain households, which Stalin implicitly approved of through a telegram he sent on the 1 January 1933 to the Ukrainian government reminding Ukrainian farmers of the severe penalties for not surrendering grain they may be hiding.

In order to make up for unfulfilled grain procurement quotas in Ukraine, reserves of grain were confiscated from three sources including, according to Oleh Wolowyna, "(a) grain set side for seed for the next harvest; (b) a grain fund for emergencies; (c) grain issued to collective farmers for previously completed work, which had to be returned if the collective farm did not fulfill its quota."

Between January and mid-April 1933, a factor contributing to a surge of deaths within certain regions of Ukraine during the period was the relentless search for alleged hidden grain by the confiscation of all food stuffs from certain households, which Stalin implicitly approved of through a telegram he sent on the 1 January 1933 to the Ukrainian government reminding Ukrainian farmers of the severe penalties for not surrendering grain they may be hiding.

In order to make up for unfulfilled grain procurement quotas in Ukraine, reserves of grain were confiscated from three sources including, according to Oleh Wolowyna, "(a) grain set side for seed for the next harvest; (b) a grain fund for emergencies; (c) grain issued to collective farmers for previously completed work, which had to be returned if the collective farm did not fulfill its quota."

Near the end of and after the famine

In Ukraine, there was a widespread purge of Communist party officials at all levels. According to Oleh Wolowyna, 390 "anti-Soviet, counter-revolutionary insurgent and chauvinist" groups were eliminated resulting in 37,797 arrests, that led to 719 executions, 8,003 people being sent toGulag

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the State Political Directorate, GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= ...

camps, and 2,728 being put into internal exile. 120,000 individuals in Ukraine were reviewed in the first 10 months of 1933 in a top-to-bottom purge of the Communist party resulting in 23% being eliminated as perceived class hostile elements. Pavel Postyshev was set in charge of placing people at the head of Machine-Tractor Stations in Ukraine which were responsible for purging elements deemed to be class hostile.

By the end of 1933, 60% of the heads of village councils and raion committees in Ukraine were replaced with an additional 40,000 lower-tier workers being purged. Purges were also extensive in the Ukrainian populated territories of the Kuban and North Caucasus. 358 of 716 party secretaries in Kuban were removed, along with 43% of the 25,000 party members there; in total, 40% of the 115,000 to 120,000 rural party members in the North Caucasus were removed. Party officials associated with Ukrainization were targeted, as the national policy was viewed to be connected with the failure of grain procurement by Soviet authorities.

Despite the crisis, the Soviet government refused to ask for foreign aid for the famine and persistently denied the famine's existence. What aid was given was selectively distributed to preserve the collective farm system. Grain producing oblasts in Ukraine such as Dnipropetrovsk

Dnipro, previously called Dnipropetrovsk from 1926 until May 2016, is Ukraine's fourth-largest city, with about one million inhabitants. It is located in the eastern part of Ukraine, southeast of the Ukrainian capital Kyiv on the Dnieper Rive ...

were given more aid at an earlier time than more severely affected regions like Kharkiv

Kharkiv ( uk, –•–įŐĀ—Ä–ļ—Ė–≤, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: –•–į—Ä—Ć–ļo–≤, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine.

which produced less grain. Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; ‚Äď 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

had quoted Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 ‚Äď 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

during the famine declaring: " He who does not work, neither shall he eat."

This perspective is argued by Michael Ellman to have influenced official policy during the famine, with those deemed to be idlers being disfavored in aid distribution as compared to those deemed "conscientiously working collective farmers". In this vein, Olga Andriewsky states that Soviet archives indicate that the most productive workers were prioritized for receiving food aid.

Food rationing in Ukraine was determined by city categories (where one lived, with capitals and industrial centers being given preferential distribution), occupational categories (with industrial and railroad workers being prioritized over blue collar workers and intelligentsia), status in the family unit (with employed persons being entitled to higher rations than dependents and the elderly), and type of workplace in relation to industrialization (with those who worked in industrial endeavors near steel mills being preferred in distribution over those who worked in rural areas or in food).

Areas depopulated by the famine were resettled by Russians in the Zaporizhzhya, Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts, but not as much so in central Ukraine. In some areas where depopulation was due to migration rather than mortality, Ukrainians returned to their places of residence to find their homes occupied by Russians, leading to widespread fights between Ukrainian farmers and Russian settlers. Such clashes caused around one million Russian settlers to be returned home.

Ukrainians in other Republics

Ukrainians in other parts of the Soviet Union also experienced famine and repressive policies. Rural districts with Ukrainian populations in parts of the Soviet Union outside of Ukraine had higher mortality rates in Russia and Belarus than other districts, this discrepancy did not however apply to urban Ukrainians in these areas. This is sometimes viewed as being connected to the Holodomor in Ukraine. In 1932‚Äď1933, the policies of forced collectivization of the Ukrainian population of the Soviet Union, which caused a devastating famine that greatly affected the Ukrainian population of the Kuban. According to the All-Union census of 1926‚Äď1937, the rural population in theNorth Caucasus

The North Caucasus, ( ady, –Ę–Ķ–ľ—č—Ä –ö—ä–į—Ą–ļ—ä–į—Ā, TemńĪr Qafqas; kbd, –ė—ą—Ö—ä—ć—Ä—ć –ö—ä–į—É–ļ—ä–į–∑, ńįŠĻ©xh…ôr…ô Qauqaz; ce, –ö—ä–ł–Ľ–Ī–į—Ā–Ķ–ī–į –ö–į–≤–ļ–į–∑, QŐáilbaseda Kavkaz; , os, –¶”ē–≥–į—ā –ö–į–≤–ļ–į–∑, C√¶gat Kavkaz, inh, ...

decreased by 24%. In the Kuban alone, from November 1932 to the spring of 1933, the number of documented victims of famine was 62,000. According to other historians, the real death toll is many times higher.

During the Soviet famine of 1932‚Äď1933 Krasnodar lost over 14% of its population. The mass repressions of the 1930s also resulted in the arrest and execution of over 1,500 Ukrainian speaking intellectuals from Krasnodar. Many teachers of the Ukrainian language were arrested and exiled from the region. By 1932, all Ukrainian language education establishments were closed. The professional Ukrainian theatre in Krasnodar was closed. All Ukrainian toponyms in the Kuban, which reflected the areas from which the first Ukrainians settlers had moved, were changed.

The names of Stanytsias such as the rural town of Kiev, in Krasnodar, was changed to "Krasnoartilyevskaya", and Uman

Uman ( uk, –£–ľ–į–Ĺ—Ć, ; pl, HumaŇĄ; yi, ◊ź◊ē◊ě◊ź÷∑◊ü) is a city located in Cherkasy Oblast in central Ukraine, to the east of Vinnytsia. Located in the historical region of the eastern Podolia, the city rests on the banks of the Umanka River ...

to "Leningrad", and Poltavska to "Krasnoarmieiskaya". The physical destruction of all aspects of Ukrainian culture and the Ukrainian population, and the resultant ethnic cleansing of the population, the Russification, the Holodomor of 1932‚Äď1933 and 1946‚Äď1947 and other tactics used by the Union government led to a catastrophic fall in the population that self-identified as being Ukrainian in the Kuban. Official Soviet Union statistics of 1959 state that Ukrainians made up 4% of the population, in 1989 ‚Äď 3%. The self-identified Ukrainian population of Kuban decreased from 915,000 in 1926, to 150,000 in 1939. and to 61,867 in 2002.

Ethnic minorities in Kazakhstan were significantly affected by the Kazakh famine of 1931‚Äď1933 in addition to the Kazakhs. Ukrainians in Kazakhstan had the second highest proportional death rate after the Kazakhs themselves. The Ukrainian population in Kazakhstan decreased from 859,396 to 549,859> (a reduction of almost 36% of their population) while other ethnic minorities in Kazakhstan lost 12% and 30% of their populations.

Aftermath and immediate reception

Despite attempts by the Soviet authorities to hide the scale of the disaster, it became known abroad thanks to the publications of journalists Gareth Jones, Malcolm Muggeridge,Ewald Ammende

Ewald Ammende (3 January 1893 in Pernau, Livonia, Russian Empire - 15 April 1936 in Peking, China) was an Estonian journalist, human rights activist and politician of Baltic German origin.

Biography

Ewald Ammende came from a wealthy, infl ...

, Rhea Clyman, photographs made by engineer Alexander Wienerberger

Alexander Wienerberger (December 8, 1891, Vienna ‚Äď January 5, 1955, Salzburg) was an Austrians, Austrian chemical engineer and right wing nationalist, who worked for 19 years in the chemical industry of the Soviet Union. While he worked in ...

, and others. To support their denial of the famine, the Soviets hosted prominent Westerners such as George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 ‚Äď 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

, French ex-prime minister √Čdouard Herriot, and others at Potemkin villages, who then made statements that they had not seen hunger.

During the German occupation of Ukraine, the occupation authorities allowed the publication of articles in local newspapers about Holodomor and other communist crimes, but they also did not want to pay too much attention to this issue in order to avoid stirring national sentiment. In 1942, Stepan Sosnovy

Stepan Mykolayovych Sosnovy (March 23, 1896, in Sivaske (now –°–ł–≤–į—Ā—Ć–ļ–Ķ), Russian Empire - March 26, 1961, in Kiev, Ukrainian SSR) was a Ukrainian-Soviet agronomist and economist and author of the first comprehensive study of the 1932-1933 ...

, an agronomist in Kharkiv

Kharkiv ( uk, –•–įŐĀ—Ä–ļ—Ė–≤, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: –•–į—Ä—Ć–ļo–≤, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine.

, published a comprehensive statistical research on the number of Holodomor casualties, based on documents from Soviet archives.

In the post-war period, the Ukrainian diaspora

The Ukrainian diaspora comprises Ukrainians and their descendants who live outside Ukraine around the world, especially those who maintain some kind of connection, even if ephemeral, to the land of their ancestors and maintain their feeling of Uk ...

disseminated information about the Holodomor in Europe and North America. At first, the public attitude was rather cautious, as the information came from people who had lived in the occupied territories, but it gradually changed in the 1950s. Scientific study of the Holodomor, based on the growing number of memoirs published by survivors, began in the 1950s.

Death toll

The Soviet Union long denied that the famine had taken place. The

The Soviet Union long denied that the famine had taken place. The NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: –Ě–į—Ä–ĺŐĀ–ī–Ĺ—č–Ļ –ļ–ĺ–ľ–ł—Ā—Ā–į—Ä–ł–įŐĀ—ā –≤–Ĺ—ÉŐĀ—ā—Ä–Ķ–Ĺ–Ĺ–ł—Ö –ī–Ķ–Ľ, Nar√≥dnyy komissari√°t vn√ļtrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

(and later KGB) controlled the archives for the Holodomor period and made relevant records available very slowly. The exact number of the victims remains unknown and is probably impossible to estimate even within a margin of error of a hundred thousand. However, by the end of 1933, millions of people had starved to death or otherwise died unnaturally in the Soviet republics. In 2001, based on a range of official demographic data, historian Stephen G. Wheatcroft noted that official death statistics for this period were systematically repressed and showed that many deaths were un-registered.

Estimates vary in their coverage, with some using the 1933 Ukraine borders, some of the current borders, and some counting ethnic Ukrainians. Some extrapolate

In mathematics, extrapolation is a type of estimation, beyond the original observation range, of the value of a variable on the basis of its relationship with another variable. It is similar to interpolation, which produces estimates between kn ...

on the basis of deaths in a given area, while others use archival data. Some historians question the accuracy of Soviet censuses, as they may reflect Soviet propaganda.

Other estimates come from recorded discussions between world leaders. In an August 1942 conversation, Stalin gave Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

his estimates of the number of " kulaks" who were repressed for resisting collectivisation as 10 million, in all of the Soviet Union, rather than only in Ukraine. When using this number, Stalin implied that it included not only those who lost their lives but also those who were forcibly deported.

There are variations in opinion as to whether deaths in Gulag labour camps should be counted or only those who starved to death at home. Estimates before archival opening varied widely such as: 2.5 million ( Volodymyr Kubiyovych); 4.8 million (Vasyl Hryshko); and 5 million ( Robert Conquest).

In the 1980s, dissident demographer and historian Alexander P. Babyonyshev (writing as Sergei Maksudov) estimated officially non-accounted child mortality

Child mortality is the mortality of children under the age of five. The child mortality rate, also under-five mortality rate, refers to the probability of dying between birth and exactly five years of age expressed per 1,000 live births.

It e ...

in 1933 at 150,000, leading to a calculation that the number of births for 1933 should be increased from 471,000 to 621,000 (down from 1,184,000 in 1927). Given the decreasing birth rates and assuming the natural mortality rates in 1933 to be equal to the average annual mortality rate in 1927‚Äď1930 (524,000 per year), a natural population growth for 1933 would have been 97,000 (as opposed to the recorded decrease of 1,379,000). This was five times less than the growth in the previous three years (1927‚Äď1930). Straight-line extrapolation of population (continuation of the previous net change) between census takings in 1927 and 1936 would have been +4.043 million, which compares to a recorded ‚ąí538,000 change. Overall change in birth and death amounts to 4.581 million fewer people but whether through factors of choice, disease or starvation will never be fully known.

In the 2000s, there were debates among historians and in civil society about the number of deaths as Soviet files were released and tension built between Russia and the Ukrainian president Viktor Yushchenko. Yushchenko and other Ukrainian politicians described fatalities as in the region of seven to ten million. Yushchenko stated in a speech to the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is Bicameralism, bicameral, composed of a lower body, the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives, and an upper body, ...

that the Holodomor "took away 20 million lives of Ukrainians,". Former Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper issued a public statement giving the death toll at about 10 million.

Some Ukrainian and Western historians use similar figures. Historian David R. Marples gave a figure of 7.5 million in 2007. During an international conference held in Ukraine in 2016, ''Holodomor 1932‚Äď1933 loss of the Ukrainian nation'', at the National University of Kyiv Taras Shevchenko, it was claimed that during the Holodomor 7 million Ukrainians were killed, and in total, 10 million people died of starvation across the USSR.

However, the use of the 7 to 20 million figures has been criticized by historians Timothy D. Snyder and Stephen G. Wheatcroft. Snyder wrote: "President Viktor Yushchenko does his country a grave disservice by claiming ten million deaths, thus exaggerating the number of Ukrainians killed by a factor of three; but it is true that the famine in Ukraine of 1932‚Äď1933 was a result of purposeful political decisions, and killed about three million people." In an email to Postmedia News

Postmedia Network Canada Corp. (also known as Postmedia Network, Postmedia News or Postmedia) is a Canadian media conglomerate consisting of the publishing properties of the former Canwest, with primary operations in newspaper publishing, new ...

, Wheatcroft wrote: "I find it regrettable that Stephen Harper and other leading Western politicians are continuing to use such exaggerated figures for Ukrainian famine mortality" and " ere is absolutely no basis for accepting a figure of 10 million Ukrainians dying as a result of the famine of 1932‚Äď1933." In 2001, Wheatcroft had calculated total population loss (including stillbirth) across the Union at 10 million and possibly up to 15 million between 1931 and 1934, including 2.8 million (and possibly up to 4.8 million excess deaths) and 3.7 million (up to 6.7 million) population losses including birth losses in Ukraine.

In 2002, Ukrainian historian , using demographic data including those recently unclassified, narrowed the losses to about 3.2 million or, allowing for the lack of precise data, 3 million to 3.5 million. The number of recorded excess deaths extracted from the birth/death statistics from Soviet archives is contradictory. The data fail to add up to the differences between the results of the 1926 Census and the 1937 Census. Kulchytsky summarized the declassified Soviet statistics as showing a decrease of 538,000 people in the population of Soviet Ukraine between 1926 census (28,926,000) and 1937 census (28,388,000).

Similarly, Wheatcroft's work from Soviet archives showed that excess deaths in Ukraine in 1932‚Äď1933 numbered a minimum of 1.8 million (2.7 including birth losses): "Depending upon the estimations made concerning unregistered mortality and natality, these figures could be increased to a level of 2.8 million to a maximum of 4.8 million excess deaths and to 3.7 million to a maximum of 6.7 million population losses (including birth losses)".

A 2002 study by French demographer Jacques Vallin and colleagues utilising some similar primary sources to Kulchytsky, and performing an analysis with more sophisticated demographic tools with forward projection of expected growth from the 1926 census and backward projection from the 1939 census estimates the number of direct deaths for 1933 as 2.582 million. This number of deaths does not reflect the total demographic loss for Ukraine from these events as the fall of the birth rate during the crisis and the out-migration contribute to the latter as well. The total population shortfall from the expected value between 1926 and 1939 estimated by Vallin amounted to 4.566 million.

Of this number, 1.057 million is attributed to the birth deficit, 930,000 to forced out-migration, and 2.582 million to the combination of excess mortality and voluntary out-migration. With the latter assumed to be negligible, this estimate gives the number of deaths as the result of the 1933 famine about 2.2 million. According to demographic studies,

A 2002 study by French demographer Jacques Vallin and colleagues utilising some similar primary sources to Kulchytsky, and performing an analysis with more sophisticated demographic tools with forward projection of expected growth from the 1926 census and backward projection from the 1939 census estimates the number of direct deaths for 1933 as 2.582 million. This number of deaths does not reflect the total demographic loss for Ukraine from these events as the fall of the birth rate during the crisis and the out-migration contribute to the latter as well. The total population shortfall from the expected value between 1926 and 1939 estimated by Vallin amounted to 4.566 million.

Of this number, 1.057 million is attributed to the birth deficit, 930,000 to forced out-migration, and 2.582 million to the combination of excess mortality and voluntary out-migration. With the latter assumed to be negligible, this estimate gives the number of deaths as the result of the 1933 famine about 2.2 million. According to demographic studies, life expectancy

Life expectancy is a statistical measure of the average time an organism is expected to live, based on the year of its birth, current age, and other demographic factors like sex. The most commonly used measure is life expectancy at birth ...

, which had been in the high forties to low fifties, fell sharply for those born in 1932 to 28 years, and for 1933 fell further to the extremely low 10.8 years for females and 7.3 years for males. It remained abnormally low for 1934 but, as commonly expected for the post-crisis period peaked in 1935‚Äď36.

According to historian Snyder in 2010, the recorded figure of excess deaths was 2.4 million. However, Snyder claims that this figure is "substantially low" due to many deaths going unrecorded. Snyder states that demographic calculations carried out by the Ukrainian government provide a figure of 3.89 million dead, and opined that the actual figure is likely between these two figures, approximately 3.3 million deaths to starvation and disease related to the starvation in Ukraine from 1932 to 1933. Snyder also estimates that of the million people who died in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, –†–ĺ—Ā—Ā–ł–Ļ—Ā–ļ–į—Ź –°–ĺ–≤–Ķ—ā—Ā–ļ–į—Ź –§–Ķ–ī–Ķ—Ä–į—ā–ł–≤–Ĺ–į—Ź –°–ĺ—Ü–ł–į–Ľ–ł—Ā—ā–ł—á–Ķ—Ā–ļ–į—Ź –†–Ķ—Ā–Ņ—É–Ī–Ľ–ł–ļ–į, Ross√≠yskaya Sov√©tskaya Federat√≠vnaya Soci ...

from famine at the same time, approximately 200,000 were ethnic Ukrainians due to Ukrainian-inhabited regions being particularly hard hit in Russia.

As a child, Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 ‚Äď 30 August 2022) was a Soviet politician who served as the 8th and final leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to the country's dissolution in 1991. He served as General Secretary of the Com ...

, born into a mixed Russian-Ukrainian family, experienced the famine in Stavropol Krai

Stavropol Krai (russian: –°—ā–į–≤—Ä–ĺ–Ņ–ĺŐĀ–Ľ—Ć—Ā–ļ–ł–Ļ –ļ—Ä–į–Ļ, r=Stavropolsky kray, p=st…ôvr…źňąpol ≤sk ≤…™j kraj) is a federal subject (a krai) of Russia. It is geographically located in the North Caucasus region in Southern Russia, and i ...

, Russia. He recalled in a memoir that "In that terrible year n 1933nearly half the population of my native village, Privolnoye, starved to death, including two sisters and one brother of my father."

Wheatcroft and R. W. Davies concluded that disease was the cause of a large number of deaths: in 1932‚Äď1933, there were 1.2 million cases of typhus and 500,000 cases of typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over severa ...

. Malnourishment increases fatality rates from many diseases, and are not counted by some historians. From 1932 to 1934, the largest rate of increase was recorded for typhus, commonly spread by lice

Louse ( : lice) is the common name for any member of the clade Phthiraptera, which contains nearly 5,000 species of wingless parasitic insects. Phthiraptera has variously been recognized as an order, infraorder, or a parvorder, as a resul ...

. In conditions of harvest failure and increased poverty, lice are likely to increase.

Gathering numerous refugees at railway stations, on trains and elsewhere facilitates the spread. In 1933, the number of recorded cases was 20 times the 1929 level. The number of cases per head of population recorded in Ukraine in 1933 was already considerably higher than in the USSR as a whole. By June 1933, the incidence in Ukraine had increased to nearly 10 times the January level, and it was much higher than in the rest of the USSR.

Estimates of the human losses due to famine must account for the numbers involved in migration (including forced resettlement). According to Soviet statistics, the migration balance for the population in Ukraine for 1927‚Äď1936 period was a loss of 1.343 million people. Even when the data were collected, the Soviet statistical institutions acknowledged that the precision was less than for the data of the natural population change. The total number of deaths in Ukraine due to unnatural causes for the given ten years was 3.238 million. Accounting for the lack of precision, estimates of the human toll range from 2.2 million to 3.5 million deaths.

According to Babyonyshev's 1981 estimate, about 81.3% of the famine victims in the Ukrainian SSR were ethnic Ukrainians, 4.5% Russians

, native_name_lang = ru

, image =

, caption =

, population =

, popplace =

118 million Russians in the Russian Federation (2002 '' Winkler Prins'' estimate)

, region1 =

, pop1 ...

, 1.4% Jews

Jews ( he, ◊ô÷į◊Ē◊ē÷ľ◊ď÷ī◊ô◊Ě, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

and 1.1% were Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in ...

. Many Belarusians, Volga Germans and other nationalities were victims as well. The Ukrainian rural population was the hardest hit by the Holodomor. Since the peasantry constituted a demographic backbone of the Ukrainian nation, the tragedy deeply affected the Ukrainians for many years. In an October 2013 opinion poll (in Ukraine) 38.7% of those polled stated "my families had people affected by the famine", 39.2% stated they did not have such relatives, and 22.1% did not know.

There was also migration in to Ukraine as a response to the famine: in response to the demographic collapse, the Soviet authorities ordered large-scale resettlements, with over 117,000 peasants from remote regions of the Soviet Union taking over the deserted farms.

Genocide question

Scholars continue to debate whether the man-made Soviet famine was a central act in a campaign of

Scholars continue to debate whether the man-made Soviet famine was a central act in a campaign of genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people‚ÄĒusually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group‚ÄĒin whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the ...

, or a tragic byproduct of rapid Soviet industrialization

Industrialisation in the Soviet Union was a process of accelerated building-up of the industrial potential of the Soviet Union to reduce the economy's lag behind the developed capitalist states, which was carried out from May 1929 to June 1941.

...

and the collectivization of agriculture. Whether the Holodomor is a genocide is a significant and contentious issue in modern politics. There is no international consensus on whether Soviet policies would fall under the legal definition of genocide. A number of governments, such as Canada, have recognized the Holodomor as an act of genocide. The decision was criticized by David R. Marples, who claimed that states who recognize the Holodomor as a genocide are motivated by emotion, or on pressure by local and international groups rather than hard evidence. In contrast, some sources argue that Russian influence and unwillingness to worsen relations with Russia would prevent or stall the recognition of Holodomor as a genocide in certain regions (for example, Germany).

Scholarly positions are diverse. Raphael Lemkin (who coined the term "genocide" and was an initiator of the Genocide Convention

The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG), or the Genocide Convention, is an international treaty that criminalizes genocide and obligates state parties to pursue the enforcement of its prohibition. It wa ...

), James Mace

James E. Mace (February 18, 1952 – May 3, 2004) was an American historian, professor, and researcher of the Holodomor.

Biography

Born in Muscogee, Oklahoma, Mace did his undergraduate studies at the Oklahoma State University, graduating ...

, Norman Naimark, Timothy Snyder and Anne Applebaum have called the Holodomor a genocide and the intentional result of Stalinist policies.

According to Lemkin, Holodomor "is a classic example of the Soviet genocide, the longest and most extensive experiment in Russification, namely the extermination of the Ukrainian nation". Lemkin stated that, because Ukrainians were very sensitive to the racial murder of its people and way too populous, the government could not follow the pattern of the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

. Instead the extermination consisted of four steps: 1) extermination of the Ukrainian national elite 2) liquidation of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church

The Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church (UAOC; uk, –£–ļ—Ä–į—ó–Ĺ—Ā—Ć–ļ–į –į–≤—ā–ĺ–ļ–Ķ—Ą–į–Ľ—Ć–Ĺ–į –Ņ—Ä–į–≤–ĺ—Ā–Ľ–į–≤–Ĺ–į —Ü–Ķ—Ä–ļ–≤–į (–£–ź–ü–¶), Ukrayinska avtokefalna pravoslavna tserkva (UAPC)) was one of the three major Eastern Orthod ...

3) extermination of a significant part of the Ukrainian peasantry as "custodians of traditions, folklore and music, national language and literature 4) populating the territory with other nationalities with intent of mixing Ukrainians with them, which would eventually lead to the dissolvance of the Ukrainian nation.

Other historians such as Michael Ellman consider the Holodomor a crime against humanity

Crimes against humanity are widespread or systemic acts committed by or on behalf of a ''de facto'' authority, usually a state, that grossly violate human rights. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity do not have to take place within the ...

, but do not classify it as a genocide. Economist Steven Rosefielde and Robert Conquest, a historian and outspoken anti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and the ...

consider the death toll to be primarily due to state policy, not poor harvests. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, also negatively connoted as rus, –†–į–∑–≤–įŐĀ–Ľ –°–ĺ–≤–ĶŐĀ—ā—Ā–ļ–ĺ–≥–ĺ –°–ĺ—éŐĀ–∑–į, r=Razv√°l Sov√©tskogo Soy√ļza, ''Ruining of the Soviet Union''. was the process of internal disintegration within the Sov ...

, Conquest was granted access to the Soviet state archives alongside other western academics. Drawing upon evidence from the archives, Conquest would later write that the Holodomor was not purposefully inflicted by Stalin but his inadequate response did worsen the famine. Robert Davies, Stephen Kotkin, Stephen Wheatcroft

Stephen George Wheatcroft (born 1 June 1947) is a Professorial Fellow of the School of Historical Studies, University of Melbourne. His research interests include Russian pre-revolutionary and Soviet social, economic and demographic history, as ...

and J. Arch Getty reject the notion that Stalin intentionally wanted to kill Ukrainians, but conclude that Stalinist policies and widespread incompetence among government officials set the stage for famine in Ukraine and other Soviet republics. In 1991, American historian Mark Tauger

Mark may refer to:

Currency

* Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark, the currency of Bosnia and Herzegovina

* East German mark, the currency of the German Democratic Republic

* Estonian mark, the currency of Estonia between 1918 and 1927

* Finn ...

considered the Holodomor primarily the result of natural conditions and failed economic policy, not intentional state policy.

Soviet and Western denial and downplay

Scholars consider Holodomor denial to be the assertion that the 1932‚Äď1933 famine in

Scholars consider Holodomor denial to be the assertion that the 1932‚Äď1933 famine in Soviet Ukraine

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, –£–ļ—Ä–į—óŐĀ–Ĺ—Ā—Ć–ļ–į –†–į–ī—ŹŐĀ–Ĺ—Ā—Ć–ļ–į –°–ĺ—Ü—Ė–į–Ľ—Ė—Ā—ā–łŐĀ—á–Ĺ–į –†–Ķ—Ā–Ņ—ÉŐĀ–Ī–Ľ—Ė–ļ–į, ; russian: –£–ļ—Ä–į–łŐĀ–Ĺ—Ā–ļ–į—Ź –°–ĺ–≤–ĶŐĀ—ā—Ā–ļ–į—Ź –°–ĺ—Ü–ł–į–Ľ–ł—Ā—ā–łŐĀ—á–Ķ—Ā–ļ–į—Ź –†–Ķ—Ā–Ņ ...

did not occur. Denying the existence of the famine was the Soviet state's position and reflected in both Soviet propaganda and the work of some Western journalists and intellectuals including George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 ‚Äď 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

, Walter Duranty

Walter Duranty (25 May 1884 ‚Äď 3 October 1957) was an Anglo-American journalist who served as Moscow bureau chief of '' The New York Times'' for fourteen years (1922‚Äď1936) following the Bolshevik victory in the Russian Civil War (1918‚Ä ...

, and Louis Fischer. In Britain and the United States, eye-witness accounts by Welsh freelance journalist Gareth Jones and by the American Communist Fred Beal were met with widespread disbelief.

In the Soviet Union, any discussion of the famine was banned entirely. Ukrainian historian Stanislav Kulchytsky stated the Soviet government ordered him to falsify his findings and depict the famine as an unavoidable natural disaster, to absolve the Communist Party and uphold the legacy of Stalin.

In modern politics