Holocaust survivors on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Holocaust survivors are people who survived

The term "Holocaust survivor" applies to Jews who lived through the mass exterminations which were carried out by the Nazis. However, the term can also be applied to those who did not come under the direct control of the Nazi regime in

The term "Holocaust survivor" applies to Jews who lived through the mass exterminations which were carried out by the Nazis. However, the term can also be applied to those who did not come under the direct control of the Nazi regime in

The largest group of survivors were the Jews who managed to escape from German-occupied Europe before or during the war. Jews had begun emigrating from Germany in 1933 once the Nazis came to power, and from Austria from 1938, after the ''

The largest group of survivors were the Jews who managed to escape from German-occupied Europe before or during the war. Jews had begun emigrating from Germany in 1933 once the Nazis came to power, and from Austria from 1938, after the ''

For survivors, the end of the war did not bring an end to their suffering. Liberation itself was extremely difficult for many survivors and the transition to freedom from the terror, brutality and starvation they had just endured was frequently traumatic:

As Allied forces fought their way across Europe and captured areas that had been occupied by the Germans, they discovered the Nazi concentration and extermination camps. In some places, the Nazis had tried to destroy all evidence of the camps to conceal the crimes that they had perpetrated there. In other places, the Allies found only empty buildings, as the Nazis had already moved the prisoners, often on death marches, to other locations. However, in many camps, the Allied soldiers found hundreds or even thousands of weak and starving survivors. Soviet forces reached Majdanek concentration camp in July 1944 and soon came across many other sites but often did not publicize what they had found; British and American units on the Western front did not reach the concentration camps in Germany until the spring of 1945.

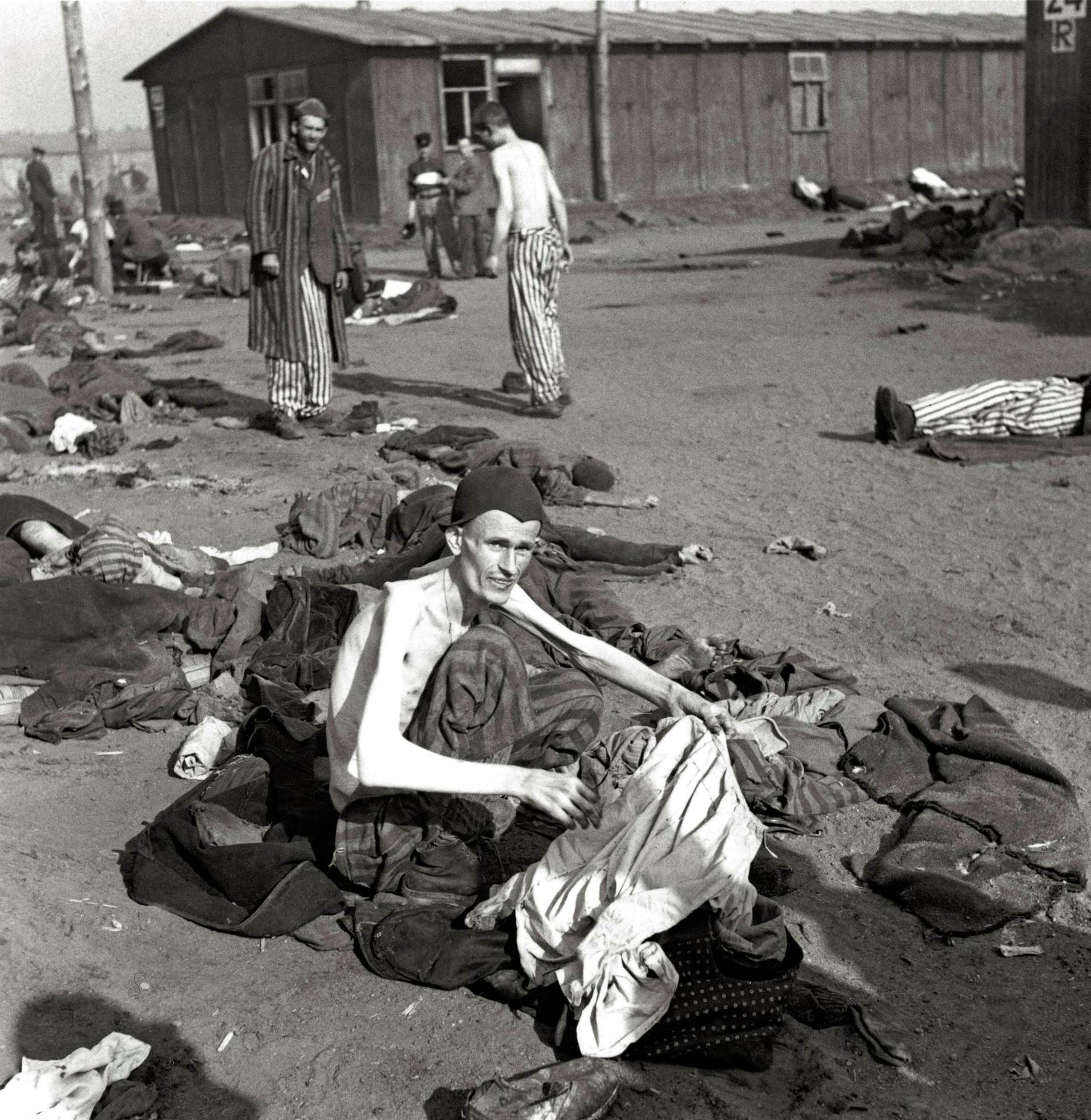

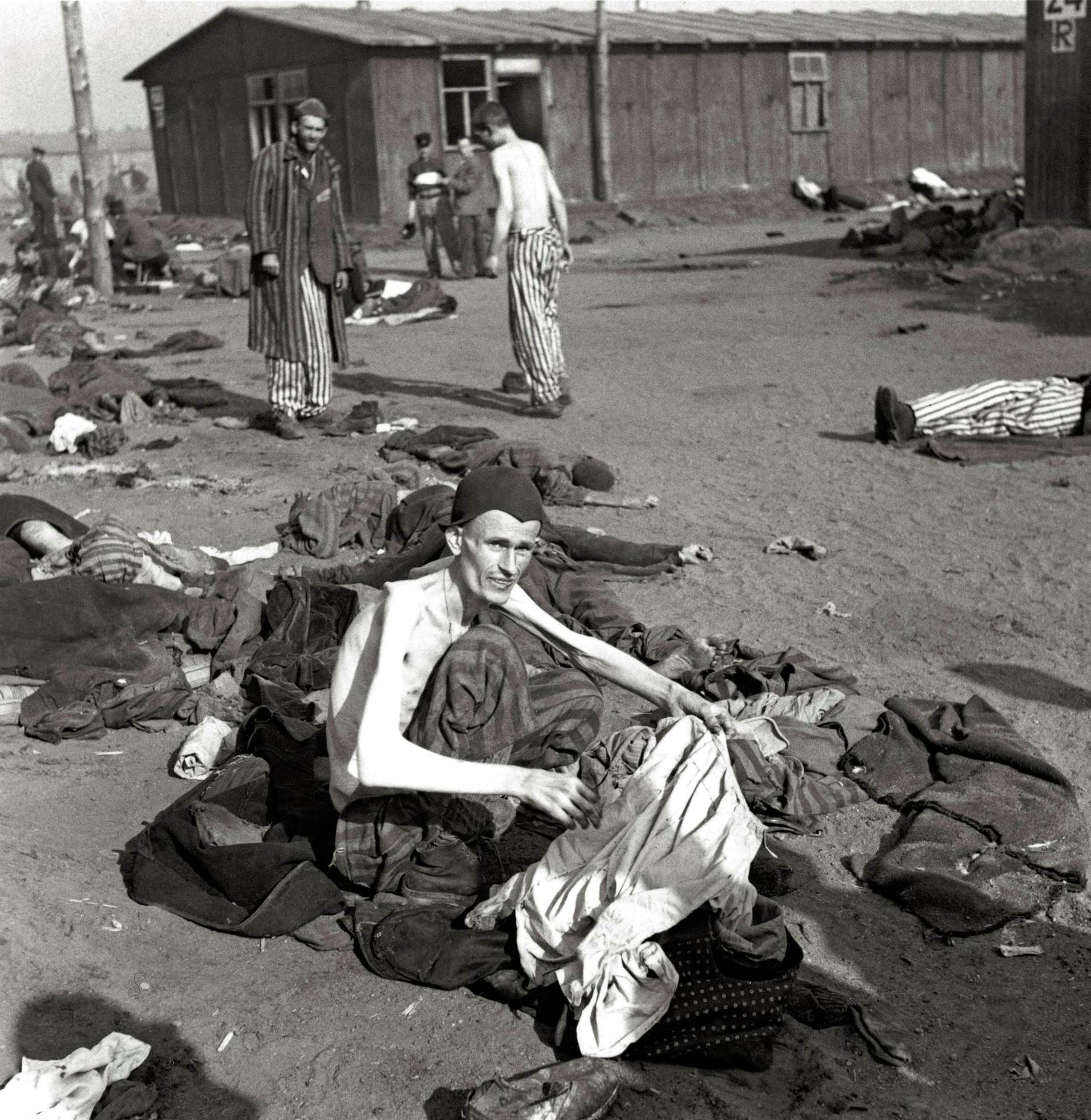

When Allied troops entered the death camps, they discovered thousands of Jewish and non-Jewish survivors suffering from starvation and disease, living in the most terrible conditions, many of them dying, along with piles of corpses, bones, and the human ashes of the victims of the Nazi mass murder. The liberators were unprepared for what they found but did their best to help the survivors. Despite this, thousands died in the first weeks after liberation. Many died from disease. Some died from refeeding syndrome since after prolonged starvation their stomachs and bodies could not take normal food. Survivors also had no possessions. At first, they still had to wear their concentration camp uniforms as they had no other clothes to wear.

During the first weeks of liberation, survivors faced the challenges of eating suitable food, in appropriate amounts for their physical conditions; recuperating from illnesses, injuries and extreme fatigue and rebuilding their health; and regaining some sense of mental and social normality. Almost every survivor also had to deal with loss of many loved ones, many being the only one remaining alive from their entire family, as well as the loss of their homes, former activities or livelihoods, and ways of life.

As survivors faced the daunting challenges of rebuilding their broken lives and finding any remaining family members, the vast majority also found that they needed to find new places to live. Returning to life as it had been before the Holocaust proved to be impossible. At first, following liberation, numerous survivors tried to return to their previous homes and communities, but Jewish communities had been ravaged or destroyed and no longer existed in much of Europe, and returning to their homes frequently proved to be dangerous. When people tried to return to their homes from camps or hiding places, they found that, in many cases, their homes had been looted or taken over by others. Most did not find any surviving relatives, encountered indifference from the local population almost everywhere, and, in eastern Europe in particular, were met with hostility and sometimes violence.

For survivors, the end of the war did not bring an end to their suffering. Liberation itself was extremely difficult for many survivors and the transition to freedom from the terror, brutality and starvation they had just endured was frequently traumatic:

As Allied forces fought their way across Europe and captured areas that had been occupied by the Germans, they discovered the Nazi concentration and extermination camps. In some places, the Nazis had tried to destroy all evidence of the camps to conceal the crimes that they had perpetrated there. In other places, the Allies found only empty buildings, as the Nazis had already moved the prisoners, often on death marches, to other locations. However, in many camps, the Allied soldiers found hundreds or even thousands of weak and starving survivors. Soviet forces reached Majdanek concentration camp in July 1944 and soon came across many other sites but often did not publicize what they had found; British and American units on the Western front did not reach the concentration camps in Germany until the spring of 1945.

When Allied troops entered the death camps, they discovered thousands of Jewish and non-Jewish survivors suffering from starvation and disease, living in the most terrible conditions, many of them dying, along with piles of corpses, bones, and the human ashes of the victims of the Nazi mass murder. The liberators were unprepared for what they found but did their best to help the survivors. Despite this, thousands died in the first weeks after liberation. Many died from disease. Some died from refeeding syndrome since after prolonged starvation their stomachs and bodies could not take normal food. Survivors also had no possessions. At first, they still had to wear their concentration camp uniforms as they had no other clothes to wear.

During the first weeks of liberation, survivors faced the challenges of eating suitable food, in appropriate amounts for their physical conditions; recuperating from illnesses, injuries and extreme fatigue and rebuilding their health; and regaining some sense of mental and social normality. Almost every survivor also had to deal with loss of many loved ones, many being the only one remaining alive from their entire family, as well as the loss of their homes, former activities or livelihoods, and ways of life.

As survivors faced the daunting challenges of rebuilding their broken lives and finding any remaining family members, the vast majority also found that they needed to find new places to live. Returning to life as it had been before the Holocaust proved to be impossible. At first, following liberation, numerous survivors tried to return to their previous homes and communities, but Jewish communities had been ravaged or destroyed and no longer existed in much of Europe, and returning to their homes frequently proved to be dangerous. When people tried to return to their homes from camps or hiding places, they found that, in many cases, their homes had been looted or taken over by others. Most did not find any surviving relatives, encountered indifference from the local population almost everywhere, and, in eastern Europe in particular, were met with hostility and sometimes violence.

One of the most well-known and comprehensive archives of Holocaust-era records, including lists of survivors, is the ''

One of the most well-known and comprehensive archives of Holocaust-era records, including lists of survivors, is the ''

Resources for Holocaust Survivors and Their Families (US and international)

–

Resources on Survivors and Victims

– United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Kavod: Honoring Aging Survivors

– journal for caregivers and families

The Holocaust: Survivors

– collection at the Jewish Virtual Library including articles, photographs, famous survivors, testimonies and reports

A Teacher's Guide to the Holocaust: Survivors

– University of South Florida

Amcha, the Israeli Center for Psychological and Social Support for Holocaust Survivors and the Second Generation

(in English)

American Gathering of Jewish Holocaust Survivors

Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany

World Federation of Jewish Child Survivors of the Holocaust & Descendants

World Jewish Restitution Organization

Holocaust Survivor Children

Holocaust Global Registry

– at

The Holocaust Survivors and Victims Database

– at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Registry of Survivors

– Museum of Jewish Heritage – A Living Memorial to the Holocaust

USC Shoah Foundation

– first-hand accounts of survivors and other eyewitnesses of the Holocaust

Holocaust Literature Research Institute

– collection of Holocaust survivor testimonials and witness accounts

an

Holocaust Survivors

– accounts of wartime and post-war experiences

Holocaust Survivor Oral History Archive

– at the University of Michigan

Talk Louder - Michael Bornstein

– Holocaust survivor's documentary {{Authority control Aftermath of the Holocaust Society of Israel Holocaust-related organizations

the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

, defined as the persecution and attempted annihilation of the Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and its allies before and during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

in Europe and North Africa. There is no universally accepted definition of the term, and it has been applied variously to Jews who survived the war in German-occupied Europe or other Axis territories, as well as to those who fled to Allied and neutral countries before or during the war. In some cases, non-Jews who also experienced collective persecution under the Nazi regime are also considered Holocaust survivors. The definition has evolved over time.

Survivors of the Holocaust include those persecuted civilians who were still alive in the concentration camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

when they were liberated at the end of the war, or those who had either survived as partisans or been hidden with the assistance of non-Jews, or had escaped to territories beyond the control of the Nazis before the Final Solution

The Final Solution (german: die Endlösung, ) or the Final Solution to the Jewish Question (german: Endlösung der Judenfrage, ) was a Nazi plan for the genocide of individuals they defined as Jews during World War II. The "Final Solution to th ...

was implemented.

At the end of the war, the immediate issues which faced Holocaust survivors were physical and emotional recovery from the starvation, abuse and suffering which they had experienced; the need to search for their relatives and reunite with them if any of them were still alive; rebuild their lives by returning to their former homes, or more often, by immigrating to new and safer locations because their homes and communities had been destroyed or because they were endangered by renewed acts of antisemitic violence.

After the initial and immediate needs of Holocaust survivors were addressed, additional issues came to the forefront. These included social welfare and psychological care, reparations and restitution for the persecution, slave labor

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

and property losses which they had suffered, the restoration of looted books, works of art and other stolen property to their rightful owners, the collection of witness and survivor testimonies, the memorialization of murdered family members and destroyed communities, and care for disabled and aging survivors.

Definition

The term "Holocaust survivor" applies to Jews who lived through the mass exterminations which were carried out by the Nazis. However, the term can also be applied to those who did not come under the direct control of the Nazi regime in

The term "Holocaust survivor" applies to Jews who lived through the mass exterminations which were carried out by the Nazis. However, the term can also be applied to those who did not come under the direct control of the Nazi regime in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

or occupied Europe

German-occupied Europe refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly occupied and civil-occupied (including puppet governments) by the military forces and the government of Nazi Germany at various times between 1939 an ...

, but were substantially affected by it, such as Jews who fled Germany or their homelands in order to escape the Nazis, and never lived in a Nazi-controlled country after Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

came to power but lived in it before the Nazis put the "Final Solution

The Final Solution (german: die Endlösung, ) or the Final Solution to the Jewish Question (german: Endlösung der Judenfrage, ) was a Nazi plan for the genocide of individuals they defined as Jews during World War II. The "Final Solution to th ...

" into effect, or others who were not persecuted by the Nazis themselves, but were persecuted by their allies or collaborators both in Nazi satellite countries and occupied countries.

Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem ( he, יָד וַשֵׁם; literally, "a memorial and a name") is Israel's official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust. It is dedicated to preserving the memory of the Jews who were murdered; honoring Jews who fought against th ...

, the State of Israel's official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust, defines Holocaust survivors as Jews who lived under Nazi control, whether it was direct or indirect, for any amount of time, and survived it. This definition includes Jews who spent the entire war living under Nazi collaborationist regimes, including France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

and Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

, but were not deported, as well as Jews who fled or were forced to leave Germany in the 1930s. Additionally, other Jewish refugees are considered Holocaust survivors, including those who fled their home countries in Eastern Europe in order to evade the invading German army and spent years living in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) is the United States' official memorial to the Holocaust. Adjacent to the National Mall in Washington, D.C., the USHMM provides for the documentation, study, and interpretation of Holocaust hi ...

gives a broader definition of Holocaust survivors: "The Museum honors any persons as survivors, Jewish or non-Jewish, who were displaced, persecuted, or discriminated against due to the racial, religious, ethnic, social, and political policies of the Nazis and their collaborators between 1933 and 1945. In addition to former inmates of concentration camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

, ghettos

A ghetto, often called ''the'' ghetto, is a part of a city in which members of a minority group live, especially as a result of political, social, legal, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished t ...

, and prisons, this definition includes, among others, people who lived as refugees or people who lived in hiding."

In the later years of the twentieth century, as public awareness of the Holocaust evolved, other groups who had previously been overlooked or marginalized as survivors began to share their testimonies with memorial projects and seek restitution for their experiences. One such group consisted of Sinti (Gypsy) survivors of Nazi persecution who went on a hunger strike at Dachau, Germany, in 1980 in order to draw attention to their situation and demand moral rehabilitation for their suffering during the Holocaust, and West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

formally recognized the genocide of the Roma in 1982. Another group that has been defined as Holocaust survivors consists of "flight survivors", that is, refugees who fled eastward into Soviet-controlled areas from the start of the war, or people were deported to various parts of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

by the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

.

The growing awareness of additional categories of survivors has prompted a broadening of the definition of Holocaust survivors by institutions such as the Claims Conference

The Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, or Claims Conference, represents the world's Jews in negotiating for compensation and restitution for victims of Nazi persecution and their heirs. According to Section 2(1)(3) of the Proper ...

, Yad Vashem and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum so it can include flight survivors and others who were previously excluded from restitution and recognition, such as those who lived in hiding during the war, including children who were hidden in order to protect them from the Nazis.

Numbers of survivors

At the start of World War II in September 1939, about nine and a half million Jews lived in the European countries that were either already under the control of Nazi Germany or would be invaded or conquered during the war. Almost two-thirds of these European Jews, nearly six million people, were annihilated, so that by the end of the war in Europe in May 1945, about 3.5 million of them had survived. Those who managed to stay alive until the end of the war, under varying circumstances, comprise the following:Concentration camp prisoners

Between 250,000 and 300,000 Jews withstood theconcentration camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

and death marches, although tens of thousands of these survivors were too weak or sick to live more than a few days, weeks or months, notwithstanding the care that they received after liberation.

Other survivors

Other Jews throughout Europe survived because the Germans and their collaborators did not manage to complete the deportations and mass-murder before Allied forces arrived, or the collaborationist regimes were overthrown. Thus, for example, in western Europe, around three quarters of the pre-war Jewish population survived theHolocaust in Italy

The Holocaust in Italy was the persecution, deportation, and murder of Jews between 1943 and 1945 in the Italian Social Republic, the part of the Kingdom of Italy occupied by Nazi Germany after the Italian surrender on September 8, 1943, dur ...

and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, about half survived in Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

, while only a quarter of the pre-war Jewish population survived in the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

. In eastern and south-eastern Europe, most of Bulgaria's Jews survived the war, as well as 60% of Jews in Romania and nearly 30% of the Jewish population in Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the ...

. Two-thirds survived in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

. In Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

, the Baltic states, Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

, Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

and Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

close to 90% of Jews were murdered by the Nazis and their local collaborators.

Throughout Europe, a few thousand Jews also survived in hiding, or with false papers posing as non-Jews, hidden or assisted by non-Jews who risked their lives to rescue Jews individually or in small groups. Several thousand Jews also survived by hiding in dense forests in Eastern Europe, and as Jewish partisans

Jewish partisans were fighters in irregular military groups participating in the Jewish resistance movement against Nazi Germany and its collaborators during World War II.

A number of Jewish partisan groups operated across Nazi-occupied Euro ...

actively resisting the Nazis as well as protecting other escapees, and, in some instances, working with non-Jewish partisan groups to fight against the German invaders.

Refugees

The largest group of survivors were the Jews who managed to escape from German-occupied Europe before or during the war. Jews had begun emigrating from Germany in 1933 once the Nazis came to power, and from Austria from 1938, after the ''

The largest group of survivors were the Jews who managed to escape from German-occupied Europe before or during the war. Jews had begun emigrating from Germany in 1933 once the Nazis came to power, and from Austria from 1938, after the ''Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a " Greater Germany ...

''. By the time war began in Europe, approximately 282,000 Jews had left Germany and 117,000 had left Austria.

Nearly 300,000 Polish Jews fled to Soviet-occupied Poland and the interior of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

between the start of the war in September 1939 and the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. After the German invasion of the Soviet Union, more than a million Soviet Jews fled eastward into the interior. The Soviet authorities imprisoned many refugees and deportees in the Gulag system in the Urals, Soviet Central Asia

Soviet Central Asia (russian: link=no, Советская Средняя Азия, Sovetskaya Srednyaya Aziya) was the part of Central Asia administered by the Soviet Union between 1918 and 1991, when the Central Asian republics declared ind ...

or Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive region, geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a ...

, where they endured forced labor, extreme conditions, hunger and disease. Nonetheless, most managed to survive, despite the harsh circumstances.

During the war, some Jews managed to escape to neutral European countries, such as Switzerland, which allowed in nearly 30,000, but turned away some 20,000 others; Spain, which permitted the entry of almost 30,000 Jewish refugees between 1939 and 1941, mostly from France, on their way to Portugal, but under German pressure allowed in fewer than 7,500 between 1942 and 1944; Portugal, which allowed thousands of Jews to enter so that they could continue their journeys from the port of Lisbon to the United States and South America; and Sweden, which allowed in some Norwegian Jews in 1940, and in October 1943, accepted almost the entire Danish Jewish community, rescued by the Danish resistance movement, which organized the escape of 7,000 Danish Jews and 700 of their non-Jewish relatives in small boats from Denmark to Sweden. About 18,000 Jews escaped by means of clandestine immigration to Palestine from central and eastern Europe between 1937 and 1944 on 62 voyages organized by the ''Mossad l'Aliyah Bet'' (Organization for Illegal Immigration), which was established by the Jewish leadership in Palestine in 1938. These voyages were conducted under dangerous conditions during the war, with hundreds of lives lost at sea.

Immediate aftermath

When the Second World War ended, the Jews who had survived theNazi concentration camps

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps, (officially) or (more commonly). The Nazi concentration camps are distinguished from other types of Nazi camps such as forced-labor camps, as well as con ...

, extermination camps, death marches, as well as the Jews who had survived by hiding in forests or hiding with rescuers, were almost all suffering from starvation, exhaustion and the abuse which they had endured, and tens of thousands of survivors continued to die from weakness, eating more than their emaciated bodies could handle, epidemic diseases, exhaustion and the shock of liberation. Some survivors returned to their countries of origin while others sought to leave Europe by immigrating to Palestine or other countries.

Trauma of liberation

For survivors, the end of the war did not bring an end to their suffering. Liberation itself was extremely difficult for many survivors and the transition to freedom from the terror, brutality and starvation they had just endured was frequently traumatic:

As Allied forces fought their way across Europe and captured areas that had been occupied by the Germans, they discovered the Nazi concentration and extermination camps. In some places, the Nazis had tried to destroy all evidence of the camps to conceal the crimes that they had perpetrated there. In other places, the Allies found only empty buildings, as the Nazis had already moved the prisoners, often on death marches, to other locations. However, in many camps, the Allied soldiers found hundreds or even thousands of weak and starving survivors. Soviet forces reached Majdanek concentration camp in July 1944 and soon came across many other sites but often did not publicize what they had found; British and American units on the Western front did not reach the concentration camps in Germany until the spring of 1945.

When Allied troops entered the death camps, they discovered thousands of Jewish and non-Jewish survivors suffering from starvation and disease, living in the most terrible conditions, many of them dying, along with piles of corpses, bones, and the human ashes of the victims of the Nazi mass murder. The liberators were unprepared for what they found but did their best to help the survivors. Despite this, thousands died in the first weeks after liberation. Many died from disease. Some died from refeeding syndrome since after prolonged starvation their stomachs and bodies could not take normal food. Survivors also had no possessions. At first, they still had to wear their concentration camp uniforms as they had no other clothes to wear.

During the first weeks of liberation, survivors faced the challenges of eating suitable food, in appropriate amounts for their physical conditions; recuperating from illnesses, injuries and extreme fatigue and rebuilding their health; and regaining some sense of mental and social normality. Almost every survivor also had to deal with loss of many loved ones, many being the only one remaining alive from their entire family, as well as the loss of their homes, former activities or livelihoods, and ways of life.

As survivors faced the daunting challenges of rebuilding their broken lives and finding any remaining family members, the vast majority also found that they needed to find new places to live. Returning to life as it had been before the Holocaust proved to be impossible. At first, following liberation, numerous survivors tried to return to their previous homes and communities, but Jewish communities had been ravaged or destroyed and no longer existed in much of Europe, and returning to their homes frequently proved to be dangerous. When people tried to return to their homes from camps or hiding places, they found that, in many cases, their homes had been looted or taken over by others. Most did not find any surviving relatives, encountered indifference from the local population almost everywhere, and, in eastern Europe in particular, were met with hostility and sometimes violence.

For survivors, the end of the war did not bring an end to their suffering. Liberation itself was extremely difficult for many survivors and the transition to freedom from the terror, brutality and starvation they had just endured was frequently traumatic:

As Allied forces fought their way across Europe and captured areas that had been occupied by the Germans, they discovered the Nazi concentration and extermination camps. In some places, the Nazis had tried to destroy all evidence of the camps to conceal the crimes that they had perpetrated there. In other places, the Allies found only empty buildings, as the Nazis had already moved the prisoners, often on death marches, to other locations. However, in many camps, the Allied soldiers found hundreds or even thousands of weak and starving survivors. Soviet forces reached Majdanek concentration camp in July 1944 and soon came across many other sites but often did not publicize what they had found; British and American units on the Western front did not reach the concentration camps in Germany until the spring of 1945.

When Allied troops entered the death camps, they discovered thousands of Jewish and non-Jewish survivors suffering from starvation and disease, living in the most terrible conditions, many of them dying, along with piles of corpses, bones, and the human ashes of the victims of the Nazi mass murder. The liberators were unprepared for what they found but did their best to help the survivors. Despite this, thousands died in the first weeks after liberation. Many died from disease. Some died from refeeding syndrome since after prolonged starvation their stomachs and bodies could not take normal food. Survivors also had no possessions. At first, they still had to wear their concentration camp uniforms as they had no other clothes to wear.

During the first weeks of liberation, survivors faced the challenges of eating suitable food, in appropriate amounts for their physical conditions; recuperating from illnesses, injuries and extreme fatigue and rebuilding their health; and regaining some sense of mental and social normality. Almost every survivor also had to deal with loss of many loved ones, many being the only one remaining alive from their entire family, as well as the loss of their homes, former activities or livelihoods, and ways of life.

As survivors faced the daunting challenges of rebuilding their broken lives and finding any remaining family members, the vast majority also found that they needed to find new places to live. Returning to life as it had been before the Holocaust proved to be impossible. At first, following liberation, numerous survivors tried to return to their previous homes and communities, but Jewish communities had been ravaged or destroyed and no longer existed in much of Europe, and returning to their homes frequently proved to be dangerous. When people tried to return to their homes from camps or hiding places, they found that, in many cases, their homes had been looted or taken over by others. Most did not find any surviving relatives, encountered indifference from the local population almost everywhere, and, in eastern Europe in particular, were met with hostility and sometimes violence.

Refugees and displaced persons

Jewish survivors who could not or did not want to go back to their old homes, particularly those whose entire families had been murdered, whose homes, or neighborhoods or entire communities had been destroyed, or who faced renewed antisemitic violence, became known by the term "''Sh'erit ha-Pletah''" (). Most of the survivors comprising the group known as ''Sh'erit ha-Pletah'' originated in central and eastern European countries, while most of those from western European countries returned to them and rehabilitated their lives there. Most of these refugees gathered in displaced persons camps in the British, French and American occupation zones of Germany, and in Austria and Italy. The conditions in these camps were harsh and primitive at first, but once basic survival needs were being met, the refugees organized representatives on a camp-by-camp basis, and then a coordinating organization for the various camps, to present their needs and requests to the authorities, supervise cultural and educational activities in the camps, and advocate that they be allowed to leave Europe and immigrate to the British Mandate of Palestine or other countries. The first meeting of representatives of survivors in the DP camps took place a few weeks after the end of the war, on 27 May 1945, at the St. Ottilien camp, where they formed and named the organization "''Sh'erit ha-Pletah''" to act on their behalf with the Allied authorities. After most survivors in the DP camps had immigrated to other countries or resettled, the Central Committee of ''She'arit Hapleta'' disbanded in December 1950 and the organization dissolved itself in the British Zone of Germany in August 1951. The term "''Sh'erit ha-Pletah''" is thus usually used in reference to Jewish refugees and displaced persons in the period after the war from 1945 to about 1950. In historical research, this term is used for Jews in Europe and North Africa in the five years or so after World War II.Displaced persons camps

After the end of World War II, most non-Jews who had been displaced by the Nazis returned to their homes and communities. For Jews, however, tens of thousands had no homes, families or communities to which they could return. Furthermore, having experienced the horrors of the Holocaust, many wanted to leave Europe entirely and restore their lives elsewhere where they would encounter lessantisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

. Other Jews who attempted to return to their previous residences were forced to leave again upon finding their homes and property stolen by their former neighbors and, particularly in central and eastern Europe, after being met with hostility and violence.

Since they had nowhere else to go, about 50,000 homeless Holocaust survivors gathered in Displaced Persons (DP) camps in Germany, Austria, and Italy. Emigration to the Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine ( ar, فلسطين الانتدابية '; he, פָּלֶשְׂתִּינָה (א״י) ', where "E.Y." indicates ''’Eretz Yiśrā’ēl'', the Land of Israel) was a geopolitical entity established between 1920 and 1948 ...

was still strictly limited by the British government and emigration to other countries such as the United States was also severely restricted. The first groups of survivors in the DP camps were joined by Jewish refugees from central and eastern Europe, fleeing to the British and American occupation zones in Germany as post-war conditions worsened in the east. By 1946, an estimated 250,000 displaced Jewish survivors – about 185,000 in Germany, 45,000 in Austria, and 20,000 in Italy – were housed in hundreds of refugee centers and DP camps administered by the militaries of the United States, Great Britain and France, and the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration

United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) was an international relief agency, largely dominated by the United States but representing 44 nations. Founded in November 1943, it was dissolved in September 1948. it became part o ...

(UNRRA).

Survivors initially endured dreadful conditions in the DP camps. The camp facilities were very poor, and many survivors were suffering from severe physical and psychological problems. Aid from the outside was slow at first to reach the survivors. Furthermore, survivors often found themselves in the same camps as German prisoners and Nazi collaborators, who had been their tormentors until just recently, along with larger number of freed non-Jewish forced laborers, and ethnic German refugees fleeing the Soviet army, and there were frequent incidents of anti-Jewish violence. Within a few months, following the visit and report of President Roosevelt's representative, Earl G. Harrison, the United States authorities recognized the need to set up separate DP camps for Jewish survivors and improve the living conditions in the DP camps. The British military administration, however, were much slower to act, fearing that recognizing the unique situation of the Jewish survivors might somehow be perceived as endorsing their calls to emigrate to Palestine and further antagonizing the Arabs there. Thus, the Jewish refugees tended to gather in the DP camps in the American zone.

The DP camps were created as temporary centers for facilitating the resettlement of the homeless Jewish refugees and to take care of immediate humanitarian needs, but they also became temporary communities where survivors began to rebuild their lives. With assistance sent from Jewish relief organizations such as the Joint Distribution Committee

American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, also known as Joint or JDC, is a Jewish relief organization based in New York City. Since 1914 the organisation has supported Jewish people living in Israel and throughout the world. The organization i ...

(JDC) in the United States and the Jewish Relief Unit in Britain, hospitals were opened, along with schools, especially in several of the camps where there were large numbers of children and orphans, and the survivors resumed cultural activities and religious practices. Many of their efforts were in preparations for emigration from Europe to new and productive lives elsewhere. They established committees to represent their issues to the Allied authorities and to a wider audience, under the Hebrew name, ''Sh'erit ha-Pletah

Sh'erit ha-Pletah is a Hebrew term for Jewish Holocaust survivors living in Displaced Persons (DP) camps, and the organisations they created to act on their behalf with the Allied authorities. These were active between 27 May 1945 and 1950–51, ...

'', an organization which existed until the early 1950s. Political life rejuvenated and a leading role was taken by the Zionist movement

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after ''Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Jew ...

, with most of the Jewish DPs declaring their intention of moving to a Jewish state in Palestine.

The slow and erratic handling of the issues regarding Jewish DPs and refugees, and the substantial increase of people in the DP camps in 1946 and 1947 gained international attention, and public opinion resulted in increasing political pressure to lift restriction on immigration to countries such as the US, Canada, and Australia and on the British authorities to stop detaining refugees who were attempting to leave Europe for Palestine, and imprisoning them in internment camps on Cyprus or returning them to Europe. Britain's treatment of Jewish refugees, such as the handling of the refugee ship '' Exodus'', shocked public opinion around the world and added to international demands to establish an independent state for the Jewish people. This led Britain to refer the matter to the United Nations which voted in 1947 to create a Jewish and an Arab state. Thus, when the British Mandate in Palestine ended in May 1948, the State of Israel was established, and Jewish refugee ships were immediately allowed unrestricted entry. In addition, the United States also changed its immigration policy to allow more Jewish refugees to enter under the provisions of the Displaced Persons Act, while other Western countries also eased curbs on emigration.

The opening of Israel's borders after its independence, as well as the adoption of more lenient emigration regulations in Western countries regarding survivors led to the closure of most of the DP camps by 1952. Föhrenwald, the last functioning DP camp closed in 1957. About 136,000 Displaced Person camp inhabitants, more than half the total, immigrated to Israel; some 80,000 emigrated to the United States, and the remainder emigrated to other countries in Europe and the rest of the world, including Canada, Australia, South Africa, Mexico and Argentina.

Searching for survivors

As soon as the war ended, survivors began looking for family members, and for most, this was their main goal once their basic needs of finding food, clothing and shelter had been met. Local Jewish committees in Europe tried to register the living and account for the dead. Parents sought the children they had hidden in convents, orphanages or with foster families. Other survivors returned to their original homes to look for relatives or gather news and information about them, hoping for a reunion or at least the certainty of knowing if a loved one had perished. The International Red Cross and Jewish relief organizations set up tracing services to support these searches, but inquiries often took a long time because of the difficulties in communications, and the displacement of millions of people by the conflict, the Nazi's policies of deportation and destruction, and the mass relocations of populations in central and eastern Europe. Location services were set up by organizations such as theWorld Jewish Congress

The World Jewish Congress (WJC) was founded in Geneva, Switzerland in August 1936 as an international federation of Jewish communities and organizations. According to its mission statement, the World Jewish Congress' main purpose is to act as ...

, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) and the Jewish Agency for Palestine

The Jewish Agency for Israel ( he, הסוכנות היהודית לארץ ישראל, translit=HaSochnut HaYehudit L'Eretz Yisra'el) formerly known as The Jewish Agency for Palestine, is the largest Jewish non-profit organization in the world. ...

. This resulted in the successful reunification of survivors, sometimes decades after their separation during the war. For example, the Location Service of the American Jewish Congress, in cooperation with other organizations, ultimately traced 85,000 survivors successfully and reunited 50,000 widely scattered relatives with their families in all parts of the world. However, the process of searching for and finding lost relatives sometimes took years and, for many survivors, continued until their end of their lives. In many cases, survivors searched all their lives for family members, without learning of their fates.

In Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

, where many Holocaust survivors emigrated, some relatives reunited after encountering each other by chance. Many survivors also found relatives from whom they had been separated through notices for missing relatives posted in newspapers and a radio program dedicated to reuniting families called ''Who Recognizes, Who Knows?''

Lists of survivors

Initially, survivors simply posted hand-written notes on message boards in the relief centers, Displaced Person's camps or Jewish community buildings where they were located, in the hope that family members or friends for whom they were looking would see them, or at the very least, that other survivors would pass on information about the people whom they were seeking. Others published notices in DP camp and survivor organization newsletters, and in newspapers, in the hopes of reconnecting with relatives who had found refuge in other places. Some survivors contacted theRed Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure respect for all human beings, and ...

and other organizations who were collating lists of survivors, such as the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration

United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) was an international relief agency, largely dominated by the United States but representing 44 nations. Founded in November 1943, it was dissolved in September 1948. it became part o ...

, which established a Central Tracing Bureau to help survivors locate relatives who had survived the concentration camps.

Various lists were collated into larger booklets and publications, which were more permanent than the original notes or newspaper notices. One such early compilation was called ''"Sharit Ha-Platah"'' (''Surviving Remnant''), published in 1946 in several volumes with the names of tens of thousands of Jews who survived the Holocaust, collected mainly by Abraham Klausner, a United States Army chaplain who visited many of the Displaced Persons camps in southern Germany and gathered lists of the people there, subsequently adding additional names from other areas.

The first "Register of Jewish Survivors" (''Pinkas HaNitzolim I'') was published by the Jewish Agency

The Jewish Agency for Israel ( he, הסוכנות היהודית לארץ ישראל, translit=HaSochnut HaYehudit L'Eretz Yisra'el) formerly known as The Jewish Agency for Palestine, is the largest Jewish non-profit organization in the world. ...

's Search Bureau for Missing Relatives in 1945, containing over 61,000 names compiled from 166 different lists of Jewish survivors in various European countries. A second volume of the "Register of Jewish Survivors" (''Pinkas HaNitzolim II'') was also published in 1945, with the names of some 58,000 Jews in Poland.

Newspapers outside of Europe also began to publish lists of survivors and their locations as more specific information about the Holocaust became known towards the end of, and after, the war. Thus, for example, the German-Jewish newspaper ''" Aufbau"'', published in New York City, printed numerous lists of Jewish Holocaust survivors located in Europe, from September 1944 until 1946.

Over time, many Holocaust survivor registries were established. Initially these were paper records, but from the 1990s, an increasing number of the records have been digitized and made available online.

Hidden children

Following the war, Jewish parents often spent months and years searching for the children they had sent into hiding. In fortunate cases, they found their children were still with the original rescuer. Many, however, had to resort to notices in newspapers, tracing services, and survivor registries in the hope of finding their children. These searches frequently ended in heartbreak — parents discovered that their child had been killed or had gone missing and could not be found. For hidden children, thousands who had been concealed with non-Jews were now orphans and no surviving family members remained alive to retrieve them. For children who had been hidden to escape the Nazis, more was often at stake than simply finding or being found by relatives. Those who had been very young when they were placed into hiding did not remember their biological parents or their Jewish origins and the only family that they had known was that of their rescuers. When they were found by relatives or Jewish organizations, they were usually afraid, and resistant to leave the only caregivers they remembered. Many had to struggle to rediscover their real identities. In some instances, rescuers refused to give up hidden children, particularly in cases where they were orphans, did not remember their identities, or had been baptized and sheltered in Christian institutions. Jewish organizations and relatives had to struggle to recover these children, including custody battles in the courts. For example, the Finaly Affair only ended in 1953, when the two young Finaly brothers, orphaned survivors in the custody of the Catholic Church in Grenoble, France, were handed over to the guardianship of their aunt, after intensive efforts to secure their return to their family. In the twenty first century, the development of DNA testing for genealogical purposes has sometimes provided essential information to people trying to find relatives from whom they were separated during the Holocaust, or to recover their Jewish identity, especially Jewish children who were hidden or adopted by non-Jewish families during the war.Immigration and absorption

After the war, anti-Jewish violence occurred in several central and Eastern European countries, motivated to varying extents by economic antagonism, increased by alarm that returning survivors would try to reclaim their stolen houses and property, as well as age-old antisemitic myths, most notably the blood libel. The largest anti-Jewish pogrom occurred in July 1946 in Kielce, a city in southeastern Poland, when rioters killed 41 people and wounded 50 more. As news of the Kielce pogrom spread, Jews began to flee from Poland, perceiving that there was no viable future for them there, and this pattern of post-war anti-Jewish violence repeated itself in other countries such as Hungary, Romania,Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

and the Ukraine. Most survivors sought to leave Europe and build new lives elsewhere.

Thus, about 50,000 survivors gathered in Displaced Persons (DP) camps in Germany, Austria, and Italy and were joined by Jewish refugees fleeing from central and eastern Europe, particularly Poland, as post-war conditions there worsened. By 1946, there were an estimated 250,000 Jewish displaced persons, of whom 185,000 were in Germany, 45,000 in Austria, and about 20,000 in Italy. As the British Mandate in Palestine ended in May 1948 and the State of Israel was established, nearly two-thirds of the survivors immigrated there. Others went to Western countries as restrictions were eased and opportunities for them to emigrate arose.

Rehabilitation

Medical care

Psychological care

Holocaust survivors suffered from the war years and afterwards in many different ways, physically, mentally and spiritually. Most survivors were deeply traumatized both physically and mentally and some of the effects lasted throughout their lives. This was expressed, among other ways, in the emotional and mental trauma of feeling that they were on a "different planet" that they could not share with others; that they had not or could not process the mourning for their murdered loved ones because at the time they were consumed with the effort required for survival; and many experienced guilt that they had survived when others had not. This dreadful period engulfed some survivors with both physical and mental scars, which were subsequently characterized by researchers as "concentration camp syndrome" (also known as survivor syndrome). Nonetheless, many survivors drew on inner strength and learned to cope, restored their lives, moved to a new place, started a family and developed successful careers.Social welfare

Restitution and reparations

Memoirs and testimonies

After the war, many Holocaust survivors engaged in efforts to record testimonies about their experiences during the war, and to memorialize lost family members and destroyed communities. These efforts included both personal accounts and memoirs of events written by individual survivors about the events that they had experienced, as well as the compilation of remembrance books for destroyed communities calledYizkor books

Yizkor books are memorial books commemorating a Jewish community destroyed during the Holocaust. The books are published by former residents or ''landsmanshaft'' societies as remembrances of homes, people and ways of life lost during World War II. ...

, usually printed by societies or groups of survivors from a common locality.

Survivors and witnesses also participated in providing oral testimonies about their experiences. At first, these were mainly for the purpose of prosecuting war criminals and often only many years later, for the sake of recounting their experiences to help process the traumatic events that they had suffered, or for the historical record and educational purposes.

Several programs were undertaken by organizations, such the as the USC Shoah Foundation Institute, to collect as many oral history testimonies of survivors as possible. In addition, survivors also began speaking at educational and commemorative events at schools and for other audiences, as well as contributing to and participating in the building of museums and memorials to remember the Holocaust.

Memoirs

Some survivors began to publish memoirs immediately after the war ended, feeling a need to write about their experiences, and about a dozen or so survivors' memoirs were published each year during the first two decades after the Holocaust, notwithstanding a general public that was largely indifferent to reading them. However, for many years after the war, many survivors felt that they could not describe their experiences to those who had not lived through the Holocaust. Those who were able to record testimony about their experiences or publish their memoirs did so inYiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ve ...

.

The number of memoirs that were published increased gradually from the 1970s onwards, indicating both the increasing need and psychological ability of survivors to relate their experiences, as well as a growing public interest in the Holocaust driven by events such as the capture and trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1961, the existential threats to Jews presented by the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab states (primarily Egypt, Syria, and Jordan) from 5 to 10 Ju ...

in 1967 and the Yom Kippur War

The Yom Kippur War, also known as the Ramadan War, the October War, the 1973 Arab–Israeli War, or the Fourth Arab–Israeli War, was an armed conflict fought from October 6 to 25, 1973 between Israel and a coalition of Arab states led by E ...

of 1973, the broadcasting in many countries of the television documentary series ''"Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

"'' in 1978, and the establishment of new Holocaust memorial centers and memorials, such as the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) is the United States' official memorial to the Holocaust. Adjacent to the National Mall in Washington, D.C., the USHMM provides for the documentation, study, and interpretation of Holocaust hi ...

.

The writing and publishing of memoirs, prevalent among Holocaust survivors, has been recognized as related to processing and recovering from memories about the traumatic past. By the end of the twentieth century, Holocaust memoirs had been written by Jews not only in Yiddish, but also other languages including Hebrew, English, French, Italian, Polish and Russian. They were written by concentration/death camp survivors, and also those who had been in hiding, or who had managed to flee from Nazi-held territories before or during the war, and sometimes they also described events after the Holocaust, including the liberation and rebuilding of lives in the aftermath of destruction.

Survivor memoirs, like other personal accounts such as oral testimony and diaries, are a significant source of information for most scholars of the history of the Holocaust, complementing more traditional sources of historical information, and presenting events from the unique points of view of individual experiences within the much greater totality, and these accounts are essential to an understanding of the Holocaust experience. While historians and survivors themselves are aware that the retelling of experiences is subjective to the source of information and sharpness of memory, they are recognized as collectively having "a firm core of shared memory" and the main substance of the accounts does not negate minor contradictions and inaccuracies in some of the details.

Yizkor books

Yizkor (Remembrance) books were compiled and published by groups of survivors or ''landsmanshaft

A landsmanshaft ( yi, לאַנדסמאַנשאַפט, also landsmanschaft; plural: landsmanshaftn) is a mutual aid society, benefit society, or hometown society of Jewish immigrants from the same European town or region.

History

The Landsmanshaf ...

'' societies of former residents to memorialize lost family members and destroyed communities and was one of the earliest ways in which the Holocaust was communally commemorated. The first of these books appeared in the 1940s and almost all were typically published privately rather than by publishing companies. Over 1,000 books of this type are estimated to have been published, albeit in very limited quantities.

Most of these books are written in Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ve ...

or Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

, while some also include sections in English or other languages, depending on where they were published. The first Yizkor books were published in the United States, mainly in Yiddish, the mother tongue of the ''landsmanschaften'' and Holocaust survivors. Beginning in the 1950s, after the mass immigration of Holocaust survivors to the newly independent State of Israel, most of the Yizkor books were published there, primarily between the mid-1950s and the mid-1970s. From the later 1970s, there was a decline in the number of collective memorial books but an increase in the number of survivors' personal memoirs. Most of the Yizkor books were devoted to the Eastern European Jewish communities in Poland, Russia, Lithuania, Latvia, Romania and Hungary, with fewer dedicated to the communities of south-eastern Europe.

Since the 1990s, many of these books, or sections of them have been translated into English, digitized, and made available online.

Testimonies and oral histories

In the immediate post-war period, officials of the DP camps and organizations providing relief to the survivors conducted interviews with survivors primarily for the purposes of providing physical assistance and assisting with relocation. Interviews were also conducted for the purpose of gathering evidence about war crimes and for the historical record. These were among the first of the recorded testimonies of the survivors Holocaust experiences. Some of the first projects to collect witness testimonies began in the DP camps, amongst the survivors themselves. Camp papers like ''Undzer Shtimme'' ("Our Voice"), published in Hohne Camp (Bergen-Belsen

Bergen-Belsen , or Belsen, was a Nazi concentration camp in what is today Lower Saxony in northern Germany, southwest of the town of Bergen near Celle. Originally established as a prisoner of war camp, in 1943, parts of it became a concentrati ...

), and ''Undzer Hofenung'' ("Our Hope"), published in Eschwege camp, (Kassel) carried the first eyewitness accounts of Jewish experiences under Nazi rule, and one of the first publications on the Holocaust, ''Fuhn Letsn Khurbn'', ("About the Recent Destruction"), was produced by DP camp members, and was eventually distributed around world.

In the following decades, a concerted effort was made to record the memories and testimonials of survivors for posterity. French Jews were amongst the first to establish an institute devoted to documentation of the Holocaust at the Center of Contemporary Jewish Documentation. In Israel, the Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem ( he, יָד וַשֵׁם; literally, "a memorial and a name") is Israel's official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust. It is dedicated to preserving the memory of the Jews who were murdered; honoring Jews who fought against th ...

memorial was officially established in 1953; the organization had already begun projects including acquiring Holocaust documentation and personal testimonies of survivors for its archives and library.

The largest collection of testimonials was ultimately gathered at the USC Shoah Foundation Institute, which was founded by Steven Spielberg in 1994 after he made the film ''Schindler’s List

''Schindler's List'' is a 1993 American epic historical drama film directed and produced by Steven Spielberg and written by Steven Zaillian. It is based on the 1982 novel ''Schindler's Ark'' by Australian novelist Thomas Keneally. The film fo ...

''. Originally named the Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation, it became a part of the University of Southern California in 2006. The foundation’s mission was to videotape the personal accounts of 50,000 Holocaust survivors and other witnesses, a goal which it achieved in 1999 and then surpassed.

In 2002, a collection of Sinti and Roma Holocaust survivor testimonies opened at the Documentation and Cultural Centre of German Sinti and Roma in Heidelberg, Germany.

Organizations and conferences

A wide range of organizations have been established to address the needs and issues of Holocaust survivors and their descendants. Immediately following the war, ''"Sh'erit ha-Pletah''" was established to meet the immediate physical and rehabilitation needs in the Displaced Persons camps and to advocate for rights to immigrate. Once these aims had largely been met by the early 1950s, the organization was disbanded. In the following decades, survivors established both local, national and eventually international organizations to address longer term physical, emotional and social needs, and organizations for specific groups such as child survivors and descendants, especially children, of survivors were also set up. Starting in the late 1970s, conferences and gatherings of survivors, their descendants, as well as rescuers and liberators began to take place and were often the impetus for the establishment and maintenance of permanent organizations.Survivors

In 1981, around 6,000 Holocaust survivors gathered in Jerusalem for the first World Gathering of Jewish Holocaust Survivors. In 1988, the Center of Organizations of Holocaust Survivors in Israel, was established to as an umbrella organization of 28 Holocaust survivor groups in Israel to advocate for survivors' rights and welfare worldwide and to the Government of Israel, and to commemorate the Holocaust and revival of the Jewish people. In 2010 it was recognized by the government as the representative organization for the entire survivor population in Israel. In 2020, it represented 55 organizations and a survivor population whose average was 84.Child survivors

Child survivors of the Holocaust were often the only ones who remained alive from their entire extended families, while even more were orphans. This group of survivors included children who had survived in the concentration/death camps, in hiding with non-Jewish families or in Christian institutions, or had been sent out of harm's way by their parents onKindertransport

The ''Kindertransport'' (German for "children's transport") was an organised rescue effort of children (but not their parents) from Nazi-controlled territory that took place during the nine months prior to the outbreak of the Second World ...

s, or by escaping with their families to remote locations in the Soviet Union, or Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flowin ...

in China. After the war, child survivors were sometimes sent to be cared for by distant relatives in other parts of the world, sometimes accepted unwillingly, and mistreated or even abused. Their experiences, memories and understanding of the terrible events they had suffered as child victims of the Nazis and their accomplices was given little consideration.

In the 1970s and 80s, small groups of these survivors, now adults, began to form in a number of communities worldwide to deal with their painful pasts in safe and understanding environments. The First International Conference on Children of Holocaust Survivors took place in 1979 under the auspices of Zachor, the Holocaust Resource Center. The conference and was attended by some 500 survivors, survivors’ children and mental health professionals and established a network for children of survivors of the Holocaust in the United States and Canada.

The International Network of Children of Jewish Holocaust Survivors held its first international conference in New York City in 1984, attended by more than 1,700 children of survivors of the Holocaust with the stated purpose of creating greater understanding of the Holocaust and its impact on the contemporary world and establishing contacts among the children of survivors in the United States and Canada.

The World Federation of Jewish Child Survivors of the Holocaust and Descendants was founded in 1985 to bring child survivors together and coordinate worldwide activities. The organization began holding annual conference in cities the United States, Canada, Europe and Israel. Descendants of survivors were also recognized as having been deeply affected by their families’ histories. In addition to the annual conferences to build community among child survivors and their descendants, members speak about their histories of survival and loss, of resilience, of the heroism of Jewish resistance and self-help for other Jews, and of the Righteous Among the Nations

Righteous Among the Nations ( he, חֲסִידֵי אֻמּוֹת הָעוֹלָם, ; "righteous (plural) of the world's nations") is an honorific used by the State of Israel to describe non-Jews who risked their lives during the Holocaust to sa ...

, at schools, public and community events; they participate in Holocaust Remembrance ceremonies and projects; and campaign against antisemitism and bigotry.

Second generation of survivors

The "second generation of Holocaust survivors" is the name given to children born after World War Two to a parent or parents who survived the Holocaust. Although the second generation did not directly experience the horrors of the Holocaust, the impact of their parents' trauma is often evident in their upbringing and outlooks, and from the 1960s, children of survivors began exploring and expressing in various ways what the implications of being children of Holocaust survivors meant to them. This conversation broadened public discussion of the events and impacts of the Holocaust. The second generation of the Holocaust has raised several research questions in psychology, and psychological studies have been conducted to determine how their parents' horrendous experiences affected their lives, among them, whether psychological trauma experienced by a parent can be passed on to their children even when they were not present during the ordeal, as well as the psychological manifestations of this transference of trauma to the second generation. Soon after descriptions of concentration camp syndrome (also known as survivor syndrome) appeared, clinicians observed in 1966 that large numbers of children ofHolocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

survivors were seeking treatment in clinics in Canada. The grandchildren of Holocaust survivors were also over-represented by 300% among the referrals to a child psychiatry clinic in comparison with their representation in the general population.

A communication pattern that psychologists have identified as a communication feature between parents who experienced trauma and their children has been referred to as the "connection of silence". This silent connection is the tacit assent, in the families of Holocaust survivors, not to discuss the trauma of the parent and to disconnect it from the daily life of the family. The parent's need for this is not only due to their need to forget and adapt to their lives after the trauma, but also to protect their children's psyches from being harmed by their depictions of the atrocities that they experienced during the Holocaust.

Awareness groups have thus developed, in which children of survivors explore their feelings in a group that shares and can better understand their experiences as children of Holocaust survivors. Some second generation survivors have also organized local and even national groups for mutual support and to pursue additional goals and aims regarding Holocaust issues. For example, in November 1979, the First Conference on Children of Holocaust Survivors was held, and resulted in the establishment of support groups all over the United States.

Many members of the "second generation" have sought ways to get past their suffering as children of Holocaust survivors and to integrate their experiences and those of their parents into their lives. For example, some have become involved in activities to commemorate the lives of people and ways of life of communities that were wiped out during the Holocaust. They research the history of Jewish life in Europe before the war and the Holocaust itself; participate in the renewal of Yiddish culture; engage in educating others about the Holocaust; fight against Holocaust denial

Holocaust denial is an antisemitic conspiracy theory that falsely asserts that the Nazi genocide of Jews, known as the Holocaust, is a myth, fabrication, or exaggeration. Holocaust deniers make one or more of the following false statements: ...

, antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

and racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonis ...

; become politically active, such as with regard to finding and prosecuting Nazis, or by taking up Jewish or humanitarian causes; and through creative means such as theater, art and literature, examine the Holocaust and its consequences on themselves and their families.

In April 1983, Holocaust survivors in North America established the American Gathering of Jewish Holocaust Survivors and their Descendants; the first event was attended by President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Ronald Reagan and 20,000 survivors and their families.

Amcha, the Israeli Center for Psychological and Social Support for Holocaust Survivors and the Second Generation was established in Jerusalem in 1987 to serve survivors and their families.

Survivor registries and databases

One of the most well-known and comprehensive archives of Holocaust-era records, including lists of survivors, is the ''

One of the most well-known and comprehensive archives of Holocaust-era records, including lists of survivors, is the ''Arolsen Archives-International Center on Nazi Persecution

The Arolsen Archives – International Center on Nazi Persecution formerly the International Tracing Service (ITS), in German Internationaler Suchdienst, in French Service International de Recherches in Bad Arolsen, Germany, is an international ...

'' founded by the Allies in 1948 as the ''International Tracing Service'' (ITS). For decades after the war, in response to inquiries, the main tasks of ITS were determining the fates of victims of Nazi persecution and searching for missing people.

The ''Holocaust Global Registry'' is an online collection of databases maintained by the Jewish genealogical website JewishGen

JewishGen is a non-profit organization founded in 1987 as an international electronic resource for Jewish genealogy. In 2003, JewishGen became an affiliate of the Museum of Jewish Heritage – A Living Memorial to the Holocaust in New York C ...