Holocaust in Poland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Holocaust in Poland was part of the European-wide

The plight of Jews in war-torn Poland could be divided into stages defined by the existence of the ghettos. Before the formation of ghettos, the escape from persecution did not involve extrajudicial punishment by death. Once the ghettos were sealed off from the outside, death by starvation and disease became rampant, alleviated only by the smuggling of food and medicine by Polish gentile volunteers, in what was described by Emanuel Ringelblum as "one of the finest pages in the history between the two peoples". In Warsaw, up to 80 percent of food consumed in the Ghetto was brought in illegally. The

The plight of Jews in war-torn Poland could be divided into stages defined by the existence of the ghettos. Before the formation of ghettos, the escape from persecution did not involve extrajudicial punishment by death. Once the ghettos were sealed off from the outside, death by starvation and disease became rampant, alleviated only by the smuggling of food and medicine by Polish gentile volunteers, in what was described by Emanuel Ringelblum as "one of the finest pages in the history between the two peoples". In Warsaw, up to 80 percent of food consumed in the Ghetto was brought in illegally. The

From the first days of the war, violence against civilians accompanied the arrival of German troops. In the September 1939

From the first days of the war, violence against civilians accompanied the arrival of German troops. In the September 1939

Messages of Murder: A Study of the Reports of the Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the Security Service, 1941–1943.

' Fairleigh Dickinson Univ. Press, pp. 125–126. . The survivors of mass killing operations were incarcerated in the new ghettos of economic exploitation, and slowly starved to death by artificial famine at the whim of German authorities. Because of sanitation concerns, the corpses of people who had died as a result of starvation and mistreatment were buried in mass graves in their tens of thousands. Gas vans became available in November 1941; in June 1942 the Polish National Council's Samuel Zygelbaum reported that these had murdered 35,000 Jews in Lodz alone. He also reported that

On January 20, 1942, during the Wannsee conference near Berlin, State Secretary of the Government General,

On January 20, 1942, during the Wannsee conference near Berlin, State Secretary of the Government General,  Systematic liquidation of the ghettos began across

Systematic liquidation of the ghettos began across

Death factories were only one means of mass extermination. There were secluded killing sites set up further east. At

Death factories were only one means of mass extermination. There were secluded killing sites set up further east. At

Połonka Little Hill

subdivision) is misspelled in the documentary, with testimony of eyewitness Shmuel Shilo. The execution site for the

The

The

The

The

Designed and built for the sole purpose of exterminating its internees,

Designed and built for the sole purpose of exterminating its internees,  Located northeast of

Located northeast of

The

The

The

The

Heinrich Himmler ordered the camp dismantled following a prisoner revolt on October 14, 1943; one of only two successful uprisings by Jewish ''Sonderkommando'' inmates in any extermination camp, with 300 escapees (most of them were recaptured by the SS and killed).

The Majdanek

The Majdanek

A popular misconception exists that most Jews went to their deaths passively. 10% of the Polish Army which fought alone against the Nazi-Soviet Invasion of Poland were Jewish Poles, some 100,000 troops. Of these, the Germans took 50,000 as prisoners-of-war and did not treat them according to the Geneva Convention; most were sent to concentration camps and then extermination camps. As Poland continued to fight an insurgency war against the occupying powers, other Jews joined the Polish Resistance, sometimes forming exclusively Jewish units.

Jewish resistance to the Nazis comprised their armed struggle, as well as spiritual and cultural opposition which brought dignity despite the inhumane conditions of life in the ghettos. Many forms of resistance existed, even though the elders were terrified by the prospect of mass retaliation against the women and children in the case of anti-Nazi revolt. ''Also in:'' As the German authorities undertook to liquidate the ghettos, armed resistance was offered in over 100 locations on either side of Polish-Soviet border of 1939, overwhelmingly in eastern Poland. ''Also in:'' Uprisings erupted in 5 major cities, 45 provincial towns, 5 major concentration and extermination camps, as well as in at least 18 forced labor camps.. Significantly, the only rebellions in

A popular misconception exists that most Jews went to their deaths passively. 10% of the Polish Army which fought alone against the Nazi-Soviet Invasion of Poland were Jewish Poles, some 100,000 troops. Of these, the Germans took 50,000 as prisoners-of-war and did not treat them according to the Geneva Convention; most were sent to concentration camps and then extermination camps. As Poland continued to fight an insurgency war against the occupying powers, other Jews joined the Polish Resistance, sometimes forming exclusively Jewish units.

Jewish resistance to the Nazis comprised their armed struggle, as well as spiritual and cultural opposition which brought dignity despite the inhumane conditions of life in the ghettos. Many forms of resistance existed, even though the elders were terrified by the prospect of mass retaliation against the women and children in the case of anti-Nazi revolt. ''Also in:'' As the German authorities undertook to liquidate the ghettos, armed resistance was offered in over 100 locations on either side of Polish-Soviet border of 1939, overwhelmingly in eastern Poland. ''Also in:'' Uprisings erupted in 5 major cities, 45 provincial towns, 5 major concentration and extermination camps, as well as in at least 18 forced labor camps.. Significantly, the only rebellions in

Zegota

, page 4/34 of the Report. In his work on Warsaw's Jews, Paulsson demonstrates that under much harsher conditions of the occupation, Warsaw's Polish citizens managed to support and hide a comparable percentage of Jews as the citizens of Western countries such as Holland or Denmark. According to historian

, Polin Museum, July 9, 2016; accessed April 2, 2018

The vast majority of Polish Jews were a "visible minority" by modern standards, distinguishable by language, behavior, and appearance. In the 1931 Polish national census, only 12 percent of Jews declared Polish as their first language, while 79 percent listed

The vast majority of Polish Jews were a "visible minority" by modern standards, distinguishable by language, behavior, and appearance. In the 1931 Polish national census, only 12 percent of Jews declared Polish as their first language, while 79 percent listed

Lukas, 2013 edition.

. Thousands of so-called Convent children hidden by the non-Jewish Poles and the Catholic Church remained in orphanages run by the Sisters of the Family of Mary in more than 20 locations, similar as in other Catholic convents. Given the severity of the German measures designed to prevent this occurrence, the survival rate among the Jewish fugitives was relatively high and by far, the individuals who circumvented deportation were the most successful. In September 1942, on the initiative of Zofia Kossak-Szczucka and with financial assistance from the

Zegota

, page 4/34 of the Report. The

Indiana University Press, Jan Grabowski, pp. 2–3. Some Polish peasants participated in German-organized ''

Many German-inspired massacres were carried out across occupied eastern Poland with the active participation of indigenous people. The guidelines for such massacres were formulated by

Many German-inspired massacres were carried out across occupied eastern Poland with the active participation of indigenous people. The guidelines for such massacres were formulated by

Haaretz.com May 18, 2009 via Internet Archive. A horrific page of history unfolded last Monday in Ukraine. It concerned the gruesome and untold story of a spontaneous pogrom by local villagers against hundreds of Jews in a town ow suburbsouth of Ternopil in 1941. Not one, but five independent witnesses recounted the tale. The SS shot the remaining two-thirds, in the same week. In Stanisławów – another provincial capital in the Kresy macroregion (now

A total of 31 deadly pogroms were carried out throughout the region in conjunction with the Belarusian, Lithuanian and Ukrainian Schuma. The genocidal techniques learned from the Germans, such as the advanced planning of the pacification actions, site selection, and sudden encirclement, became the hallmark of the

Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

organized by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and took place in German-occupied Poland

German-occupied Poland during World War II consisted of two major parts with different types of administration.

The Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany following the invasion of Poland at the beginning of World War II—nearly a quarter of the ...

. During the genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the ...

, three million Polish Jews

The history of the Jews in Poland dates back at least 1,000 years. For centuries, Poland was home to the largest and most significant Ashkenazi Jewish community in the world. Poland was a principal center of Jewish culture, because of the l ...

were murdered, half of all Jews murdered during the Holocaust.

The Holocaust in Poland was marked by the construction of death camps

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (german: Vernichtungslager), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocaust. T ...

by Nazi Germany, German use of gas vans

A gas van or gas wagon (russian: душегубка, ''dushegubka'', literally "soul killer"; german: Gaswagen) was a truck reequipped as a mobile gas chamber. During the World War II Holocaust, Nazi Germany developed and used gas vans on a larg ...

, and mass shootings by German troops and their Ukrainian and Lithuanian auxiliaries. The extermination camps played a central role in the extermination both of Polish Jews, and of Jews whom Germany transported to their deaths from western and southern Europe.

Every branch of the sophisticated German bureaucracy was involved in the killing process, from the interior and finance ministries to German firms and state-run railroads. Approximately 98 percent of Jewish population of Nazi-occupied Poland during the Holocaust were killed. About 350,000 Polish Jews survived the war; most survivors never lived in Nazi-occupied Poland, but lived in the Soviet-occupied zone of Poland during 1939 and 1940, and fled or were evacuated by the Soviets further east to avoid the German advance in 1941.

Of over 3,000,000 Polish Jews deported to Nazi concentration camps

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps, (officially) or (more commonly). The Nazi concentration camps are distinguished from other types of Nazi camps such as forced-labor camps, as well as con ...

, only about 50,000 survived.

Background

Following the 1939invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week af ...

, in accordance with the secret protocol of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

, long_name = Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

, image = Bundesarchiv Bild 183-H27337, Moskau, Stalin und Ribbentrop im Kreml.jpg

, image_width = 200

, caption = Stalin and Ribbentrop shaking ...

, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union partitioned Poland into occupation zones. Large areas of western Poland were annexed by Germany. Some 52% of Poland's territory, mainly the Kresy

Eastern Borderlands ( pl, Kresy Wschodnie) or simply Borderlands ( pl, Kresy, ) was a term coined for the eastern part of the Second Polish Republic during the History of Poland (1918–1939), interwar period (1918–1939). Largely agricultural ...

borderlands—inhabited by between 13.2 and 13.7 million people, including 1,300,000 Jews—was annexed by the Soviet Union. An estimated 157,000 to 375,000 Polish Jews either fled into the Soviet Union or were deported eastward by the Soviet authorities. Within months, Polish Jews in the Soviet zone who refused to swear allegiance were deported deep into the Soviet interior along with ethnic Poles. The number of deported Polish Jews is estimated at 200,000–230,000 men, women, and children.

Both occupying powers were hostile to the existence of a sovereign Polish state. However, Soviet possession was short-lived because the terms of the Nazi–Soviet Pact, signed earlier in Moscow, were broken when the German army

The German Army (, "army") is the land component of the armed forces of Germany. The present-day German Army was founded in 1955 as part of the newly formed West German ''Bundeswehr'' together with the ''Marine'' (German Navy) and the ''Luftwaf ...

invaded the Soviet occupation zone

The Soviet Occupation Zone ( or german: Ostzone, label=none, "East Zone"; , ''Sovetskaya okkupatsionnaya zona Germanii'', "Soviet Occupation Zone of Germany") was an area of Germany in Central Europe that was occupied by the Soviet Union as a ...

on June 22, 1941 ''(see map)''. From 1941 to 1943, all of Poland was under Germany's control. The semi-colonial General Government

The General Government (german: Generalgouvernement, pl, Generalne Gubernatorstwo, uk, Генеральна губернія), also referred to as the General Governorate for the Occupied Polish Region (german: Generalgouvernement für die be ...

, set up in central and southeastern Poland, comprised 39 percent of occupied Polish territory.

Nazi ghettoization policy

Prior to World War II, there were 3,500,000 Jews in Poland, living mainly in cities: about 10% of the general population. The database of thePOLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews

POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews ( pl, Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich) is a museum on the site of the former Warsaw Ghetto. The Hebrew word ''Polin'' in the museum's English name means either "Poland" or "rest here" and relates to a ...

provides information on 1,926 Jewish communities across the country. Following the conquest of Poland and the 1939 murder of intelligentsia, the first German anti-Jewish measures involved a policy of expelling Jews from Polish territories annexed by the Third Reich. The westernmost provinces, of Greater Poland

Greater Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska (; german: Großpolen, sv, Storpolen, la, Polonia Maior), is a historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief and largest city is Poznań followed by Kalisz, the oldest cit ...

and Pomerelia, were turned into new German ''Reichsgau

A (plural ) was an administrative subdivision created in a number of areas annexed by Nazi Germany between 1938 and 1945.

Overview

The term was formed from the words (realm, empire) and , the latter a deliberately medieval-sounding word w ...

e'' named Danzig-West Prussia

Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia (german: Reichsgau Danzig-Westpreußen) was an administrative division of Nazi Germany created on 8 October 1939 from annexed territory of the Free City of Danzig, the Greater Pomeranian Voivodship ( Polish Corrido ...

and Wartheland

The ''Reichsgau Wartheland'' (initially ''Reichsgau Posen'', also: ''Warthegau'') was a Nazi German ''Reichsgau'' formed from parts of Polish territory annexed in 1939 during World War II. It comprised the region of Greater Poland and adjacent ...

, with the intent to completely Germanize them through settler colonization (''Lebensraum

(, ''living space'') is a German concept of settler colonialism, the philosophy and policies of which were common to German politics from the 1890s to the 1940s. First popularized around 1901, '' lso in:' became a geopolitical goal of Imper ...

''). Annexed directly to the new ''Warthegau'' district, the city of Łódź

Łódź, also rendered in English as Lodz, is a city in central Poland and a former industrial centre. It is the capital of Łódź Voivodeship, and is located approximately south-west of Warsaw. The city's coat of arms is an example of ca ...

absorbed an initial influx of some 40,000 Polish Jews forced out of surrounding areas. A total of 204,000 Jewish people passed through the ghetto in Łódź. Initially, they were to be expelled to the '' Generalgouvernement''. However, the ultimate destination for the massive removal of Jews was left open until the Final Solution

The Final Solution (german: die Endlösung, ) or the Final Solution to the Jewish Question (german: Endlösung der Judenfrage, ) was a Nazi plan for the genocide of individuals they defined as Jews during World War II. The "Final Solution to th ...

was set in motion two years later.

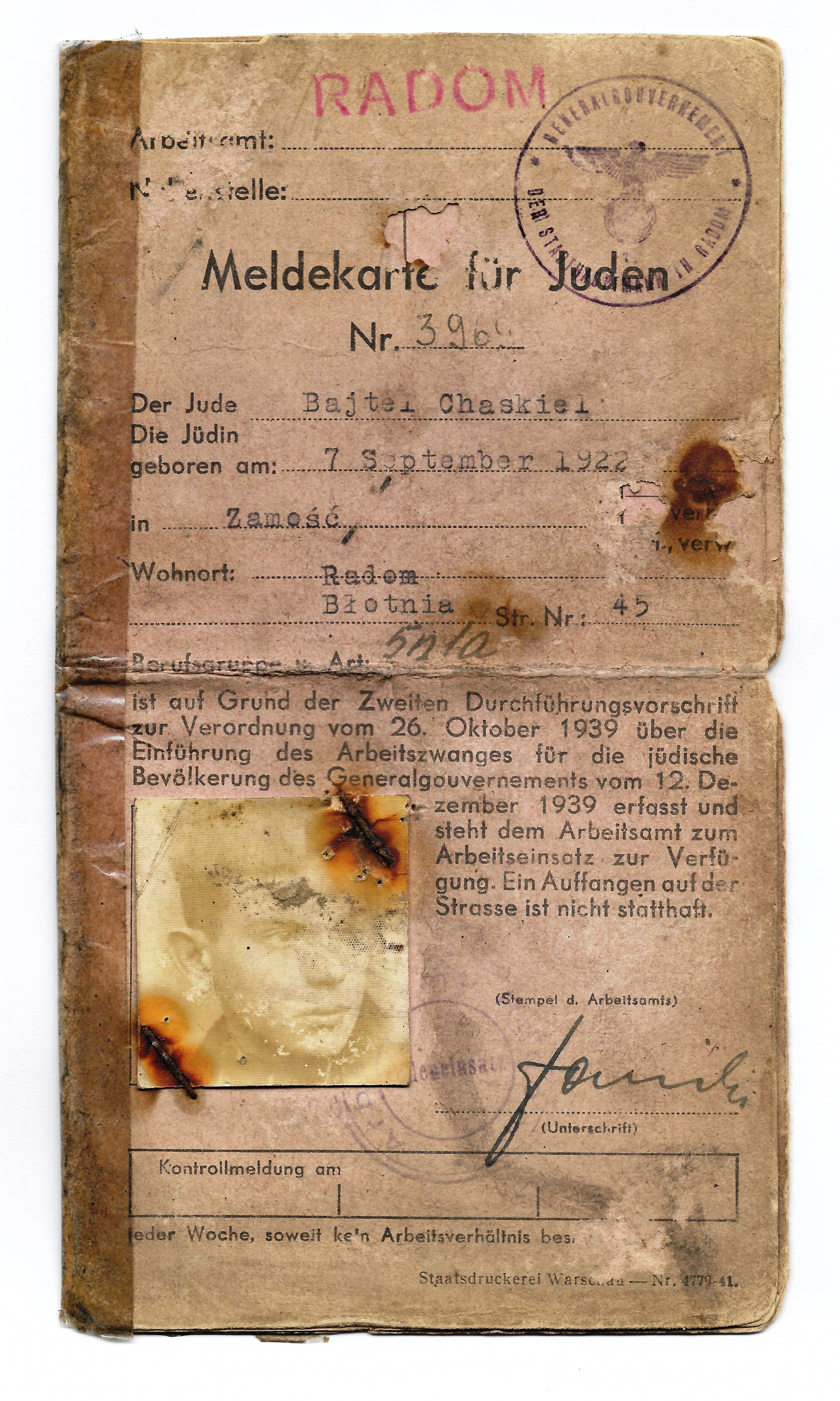

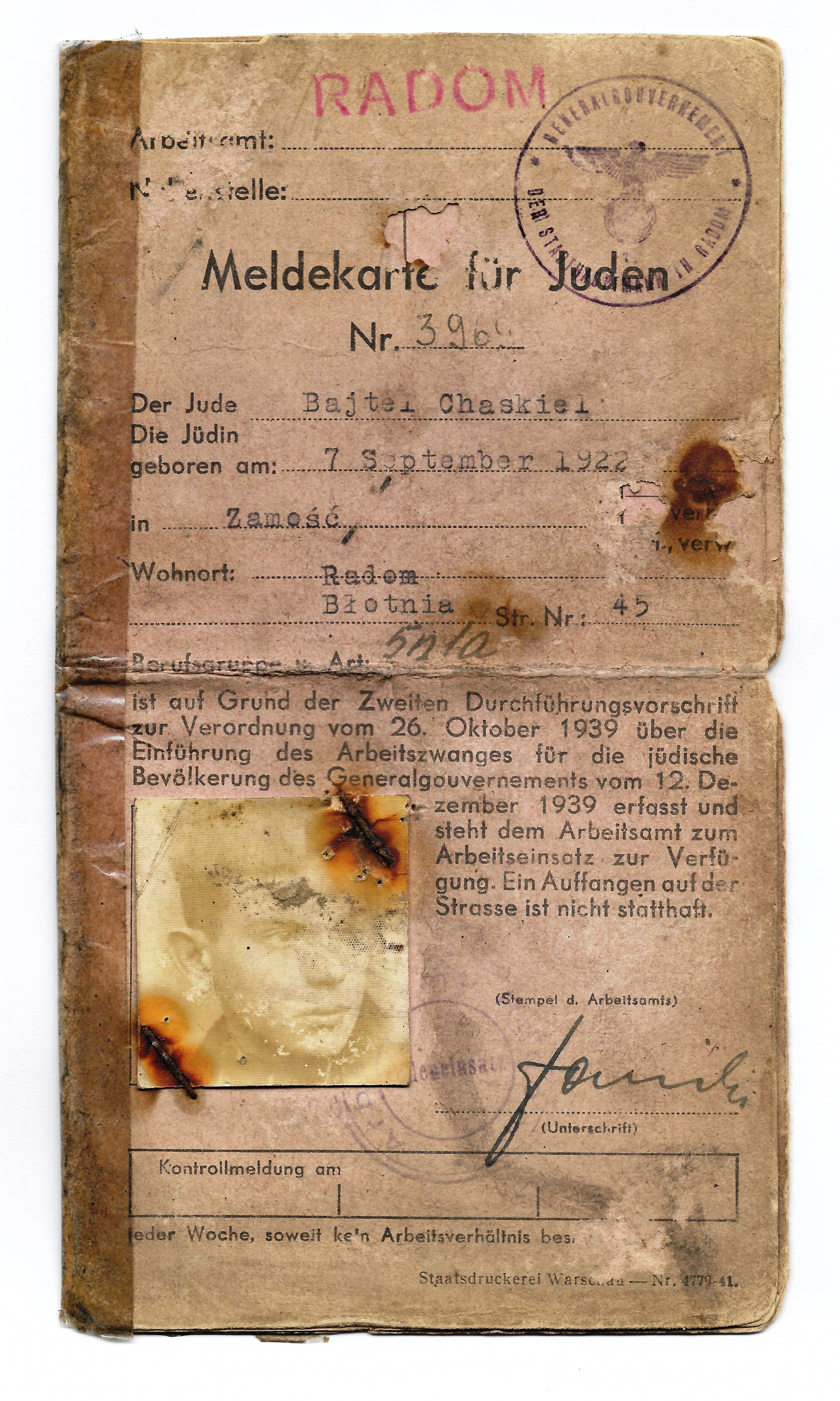

Persecution of Polish Jews by the German occupation authorities began immediately after the invasion, particularly in major urban areas. In the first year and a half, the Nazis confined themselves to stripping the Jews of their valuables and property for profit, herding them into makeshift ghettos, and forced them into slave labor

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. During this period, the Germans ordered Jewish communities to appoint Jewish Councils (''Judenräte

A ''Judenrat'' (, "Jewish council") was a World War II administrative agency imposed by Nazi Germany on Jewish communities across German-occupied Europe, occupied Europe, principally within the Nazi ghettos. The Germans required Jews to form a ' ...

'') to administer the ghettos and to be "responsible in the strictest sense" for carrying out orders. Most ghettos were established in cities and towns where Jewish life was already well organized. In a massive deportation action involving the use of freight trains, all Polish Jews had been segregated from the rest of society in dilapidated neighborhoods (''Jüdischer Wohnbezirk'') adjacent to the existing rail corridors. The food aid was completely dependent on the '' SS'', and the Jews were sealed off from the general public in an unsustainable manner.

The plight of Jews in war-torn Poland could be divided into stages defined by the existence of the ghettos. Before the formation of ghettos, the escape from persecution did not involve extrajudicial punishment by death. Once the ghettos were sealed off from the outside, death by starvation and disease became rampant, alleviated only by the smuggling of food and medicine by Polish gentile volunteers, in what was described by Emanuel Ringelblum as "one of the finest pages in the history between the two peoples". In Warsaw, up to 80 percent of food consumed in the Ghetto was brought in illegally. The

The plight of Jews in war-torn Poland could be divided into stages defined by the existence of the ghettos. Before the formation of ghettos, the escape from persecution did not involve extrajudicial punishment by death. Once the ghettos were sealed off from the outside, death by starvation and disease became rampant, alleviated only by the smuggling of food and medicine by Polish gentile volunteers, in what was described by Emanuel Ringelblum as "one of the finest pages in the history between the two peoples". In Warsaw, up to 80 percent of food consumed in the Ghetto was brought in illegally. The food stamps

In the United States, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as the Food Stamp Program, is a federal program that provides food-purchasing assistance for low- and no-income people. It is a federal aid program, ad ...

introduced by the Germans, provided only 9 percent of the calories necessary for survival. In the two and a half years between November 1940 and May 1943, around 100,000 Jews were murdered in the Warsaw Ghetto by forced starvation and disease; and about 40,000 in the Łódź Ghetto

The Łódź Ghetto or Litzmannstadt Ghetto (after the Nazi German name for Łódź) was a Nazi ghetto established by the German authorities for Polish Jews and Roma following the Invasion of Poland. It was the second-largest ghetto in all of ...

in the four-and-a-quarter years between May 1940 and August 1944. By the end of 1941, most ghettoized Jews had no savings left to pay the ''SS'' for further bulk food deliveries. The 'productionists' among the German authoritieswho attempted to make the ghettos self-sustaining by turning them into enterprisesprevailed over the 'attritionists' only after the German invasion of the Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

.. The most prominent ghettos were thus temporarily stabilized through the production of goods needed at the front, as death rates among the Jewish population there began to decline.

Holocaust by bullets

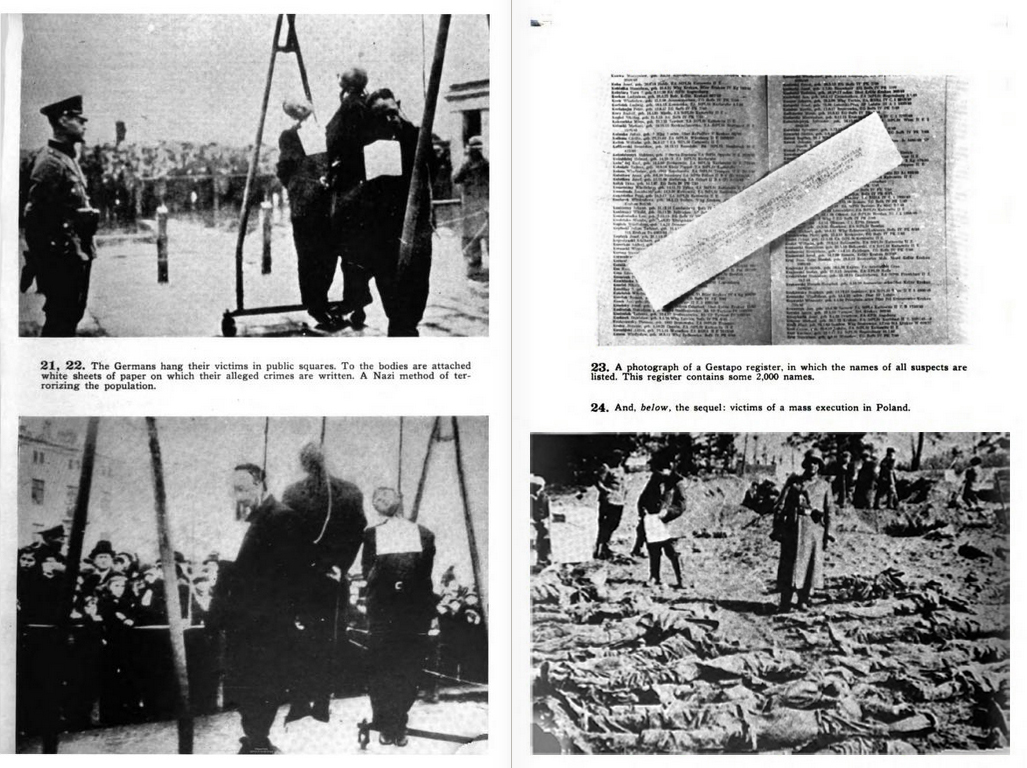

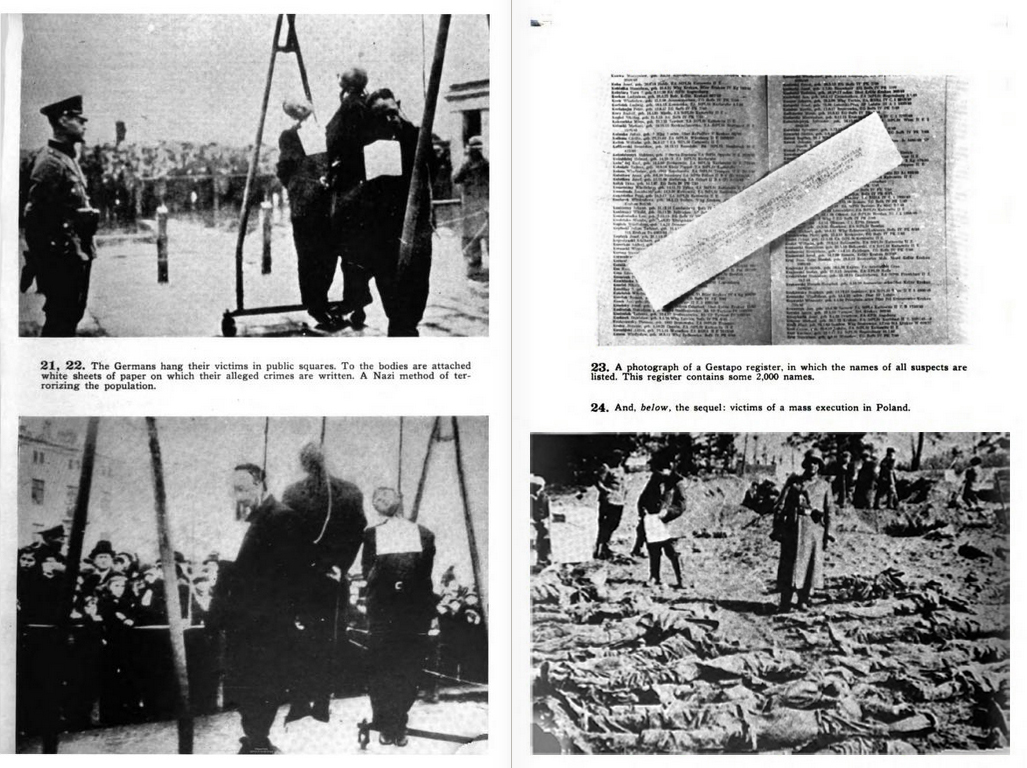

From the first days of the war, violence against civilians accompanied the arrival of German troops. In the September 1939

From the first days of the war, violence against civilians accompanied the arrival of German troops. In the September 1939 Częstochowa massacre

The Częstochowa massacre, also known as the Bloody Monday, was committed by the German '' Wehrmacht'' forces beginning on the 4th day of World War II in the Polish city of Częstochowa, between 4 and 6 September 1939. The shootings, beatings an ...

, 150 Jewish Poles were among the circa 1,140 Polish civilians shot by German Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previo ...

troops. In November 1939, outside Ostrów Mazowiecka

Ostrów Mazowiecka is a town in eastern Poland with 23,486 inhabitants (2004). Situated in the Masovian Voivodeship (since 1999), previously in Ostrołęka Voivodeship (1975–1998). It is the capital of Ostrów Mazowiecka County.

History

Os ...

, around 500 Jewish men, women and children were shot in mass graves. In December 1939, around 100 Jews were shot by Wehrmacht soldiers and gendarmes at Kolo.

Following the German attack on the USSR in June 1941, Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

assembled a force of some 11,000 men to pursue a program of physical annihilation of Jews. Also during Operation Barbarossa, the ''SS'' had recruited collaborationist auxiliary police

The ''Schutzmannschaft'' or Auxiliary Police ( "protective, or guard units"; plural: ''Schutzmannschaften'', abbreviated as ''Schuma'') was the collaborationist auxiliary police of native policemen serving in those areas of the Soviet Union an ...

from among Soviet POWs and local police which included Russians, Ukrainians, Latvians, Lithuanians and Volksdeutche

In Nazi German terminology, ''Volksdeutsche'' () were "people whose language and culture had German origins but who did not hold German citizenship". The term is the nominalised plural of ''volksdeutsch'', with ''Volksdeutsche'' denoting a sing ...

. The local '' Schutzmannschaft'' provided Germany with manpower and critical knowledge of local regions and languages. In what became known as the "Holocaust by bullets", the German police battalions (''Orpo''), ''SiPo

The ''Sicherheitspolizei'' ( en, Security Police), often abbreviated as SiPo, was a term used in Germany for security police. In the Nazi era, it referred to the state political and criminal investigation security agencies. It was made up by the ...

'', Waffen-SS

The (, "Armed SS") was the combat branch of the Nazi Party's ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with Waffen-SS foreign volunteers and conscripts, volunteers and conscripts from both occup ...

, and special-task ''Einsatzgruppen

(, ; also ' task forces') were (SS) paramilitary death squads of Nazi Germany that were responsible for mass murder, primarily by shooting, during World War II (1939–1945) in German-occupied Europe. The had an integral role in the im ...

'', along with Ukrainian and Lithuanian auxiliaries

Auxiliaries are support personnel that assist the military or police but are organised differently from regular forces. Auxiliary may be military volunteers undertaking support functions or performing certain duties such as garrison troops, ...

, operated behind front lines, systematically shooting tens of thousands of men, women, and children. The Wehrmacht participated in many aspects of the Holocaust by bullets.

Massacres were committed in over 30 locations across the formerly Soviet-occupied parts of Poland, including in Brześć

Brest ( be, Брэст / Берасьце, Bieraście, ; russian: Брест, ; uk, Берестя, Berestia; lt, Brasta; pl, Brześć; yi, בריסק, Brisk), formerly Brest-Litovsk (russian: Брест-Литовск, lit=Lithuanian Br ...

, Tarnopol

Ternópil ( uk, Тернопіль, Ternopil' ; pl, Tarnopol; yi, טאַרנאָפּל, Tarnopl, or ; he, טארנופול (טַרְנוֹפּוֹל), Tarnopol; german: Tarnopol) is a city in the west of Ukraine. Administratively, Terno ...

, and Białystok

Białystok is the largest city in northeastern Poland and the capital of the Podlaskie Voivodeship. It is the tenth-largest city in Poland, second in terms of population density, and thirteenth in area.

Białystok is located in the Białystok U ...

, as well as in prewar provincial capitals of Łuck, Lwów

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in Western Ukraine, western Ukraine, and the List of cities in Ukraine, seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is o ...

, Stanisławów, and Wilno

Vilnius ( , ; see also #Etymology and other names, other names) is the capital and List of cities in Lithuania#Cities, largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the munic ...

(see Ponary).Ronald Headland (1992), Messages of Murder: A Study of the Reports of the Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the Security Service, 1941–1943.

' Fairleigh Dickinson Univ. Press, pp. 125–126. . The survivors of mass killing operations were incarcerated in the new ghettos of economic exploitation, and slowly starved to death by artificial famine at the whim of German authorities. Because of sanitation concerns, the corpses of people who had died as a result of starvation and mistreatment were buried in mass graves in their tens of thousands. Gas vans became available in November 1941; in June 1942 the Polish National Council's Samuel Zygelbaum reported that these had murdered 35,000 Jews in Lodz alone. He also reported that

Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one orga ...

agents were routinely dragging Jews out of their homes and shooting them on the street in broad daylight. By December 1941, about one million Jews had been murdered by Nazi ''Einsatzgruppen

(, ; also ' task forces') were (SS) paramilitary death squads of Nazi Germany that were responsible for mass murder, primarily by shooting, during World War II (1939–1945) in German-occupied Europe. The had an integral role in the im ...

'' in the Soviet Union. The 'war of destruction' policy in the east against 'the Jewish race' became common knowledge among the Germans at all levels. The total number of shooting victims in the east who were Jewish are around 1.3 to 1.5 million. Entire regions behind the German–Soviet Frontier were reported to Berlin by the Nazi death squads to be ''"Judenfrei

''Judenfrei'' (, "free of Jews") and ''judenrein'' (, "clean of Jews") are terms of Nazi origin to designate an area that has been "cleansed" of Jews during The Holocaust.

While ''judenfrei'' refers merely to "freeing" an area of all of its ...

"''.

Final Solution and liquidation of Ghettos

On January 20, 1942, during the Wannsee conference near Berlin, State Secretary of the Government General,

On January 20, 1942, during the Wannsee conference near Berlin, State Secretary of the Government General, Josef Bühler

Josef Bühler (16 February 1904 – 22 August 1948) was a state secretary and deputy governor to the Nazi Germany-controlled General Government in Kraków during World War II.

Background

Bühler was born in Bad Waldsee into a Catholic family ...

, urged Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich ( ; ; 7 March 1904 – 4 June 1942) was a high-ranking German SS and police official during the Nazi era and a principal architect of the Holocaust.

He was chief of the Reich Security Main Office (inclu ...

to begin the proposed "final solution

The Final Solution (german: die Endlösung, ) or the Final Solution to the Jewish Question (german: Endlösung der Judenfrage, ) was a Nazi plan for the genocide of individuals they defined as Jews during World War II. The "Final Solution to th ...

to the Jewish question" as soon as possible. The industrial killing by exhaust fumes had been tested over several weeks at the Chełmno extermination camp

, known for =

, location = Near Chełmno nad Nerem, ''Reichsgau Wartheland'' (German-occupied Poland)

, built by =

, operated by =

, commandant = Herbert Lange, Christian Wirth

, original use =

, construction =

, in operatio ...

in the then-Wartheland, under the guise of resettlement. All condemned Ghetto prisoners were told they were going to labour camps, and asked to pack a carry-on luggage. Many Jews believed in the transfer ruse, since deportations were also part of the ghettoization process. Meanwhile, the idea of mass murder by means of stationary gas chambers was developed by September 1941 or earlier. It was a precondition for the newly drafted Operation Reinhard

or ''Einsatz Reinhard''

, location = Occupied Poland

, date = October 1941 – November 1943

, incident_type = Mass deportations to extermination camps

, perpetrators = Odilo Globočnik, Hermann Höfle, Richard Thomalla, Erwin L ...

led by Odilo Globocnik

Odilo Lothar Ludwig Globocnik (21 April 1904 – 31 May 1945) was an Austrian Nazi and a perpetrator of the Holocaust. He was an official of the Nazi Party and later a high-ranking leader of the SS. Globocnik had a leading role in Operation Re ...

who ordered the construction of death camps at Belzec, Sobibór, and Treblinka

Treblinka () was an extermination camp, built and operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland during World War II. It was in a forest north-east of Warsaw, south of the village of Treblinka in what is now the Masovian Voivodeship. The cam ...

. At Majdanek and Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 Nazi concentration camps, concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, occupied Poland (in a portion annexed int ...

, the work of the stationary gas chambers began in March and May respectively, preceded by experiments with Zyklon B

Zyklon B (; translated Cyclone B) was the trade name of a cyanide-based pesticide invented in Germany in the early 1920s. It consisted of hydrogen cyanide (prussic acid), as well as a cautionary eye irritant and one of several adsorbents such ...

. Between 1942 and 1944, the most extreme measure of the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

, the extermination of millions of Jews from Poland and all over Europe was carried out in six extermination camp

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (german: Vernichtungslager), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocaust. The v ...

s. There were no Polish guards at any of the Reinhard Reinhard is a German, Austrian, Danish, and to a lesser extent Norwegian surname (from Germanic ''ragin'', counsel, and ''hart'', strong), and a spelling variant of Reinhardt.

Persons with the given name

*Reinhard of Blankenburg (after 1107 – 11 ...

camps, despite the sometimes used misnomer Polish death camps. All killing centres were designed and operated by the Nazis in strict secrecy, aided by the Ukrainian Trawnikis. Civilians were forbidden to approach them and often shot if caught near the train tracks.

General Government

The General Government (german: Generalgouvernement, pl, Generalne Gubernatorstwo, uk, Генеральна губернія), also referred to as the General Governorate for the Occupied Polish Region (german: Generalgouvernement für die be ...

in the early spring of 1942. At that point, the only chance for survival was escape to the "Aryan side". The German round-ups for the so-called resettlement trains were connected directly with the use of top secret extermination facilities built for the SS at about the same time by various German engineering companies including HAHB, I.A. Topf and Sons of Erfurt

Erfurt () is the capital and largest city in the Central German state of Thuringia. It is located in the wide valley of the Gera river (progression: ), in the southern part of the Thuringian Basin, north of the Thuringian Forest. It sits in ...

, and C.H. Kori GmbH.

Unlike other Nazi concentration camp

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps, (officially) or (more commonly). The Nazi concentration camps are distinguished from other types of Nazi camps such as forced-labor camps, as well as con ...

s, where prisoners from all across Europe were exploited for the war effort, German death camp

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (german: Vernichtungslager), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocaust. The v ...

spart of the secret Operation Reinhardt

or ''Einsatz Reinhard''

, location = Occupied Poland

, date = October 1941 – November 1943

, incident_type = Mass deportations to extermination camps

, perpetrators = Odilo Globočnik, Hermann Höfle, Richard Thomalla, Erwin ...

were designed exclusively for the rapid and industrial-scale murder of Polish and foreign Jews, subsisting in isolation. The camp's German overseers reported to Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

, who kept control of the extermination program, but who delegated the work in Poland to SS and police chief Odilo Globocnik

Odilo Lothar Ludwig Globocnik (21 April 1904 – 31 May 1945) was an Austrian Nazi and a perpetrator of the Holocaust. He was an official of the Nazi Party and later a high-ranking leader of the SS. Globocnik had a leading role in Operation Re ...

of the Lublin Reservation

The Nisko Plan was an operation to deport Jews to the Lublin District of the General Governorate of occupied Poland in 1939. Organized by Nazi Germany, the plan was cancelled in early 1940.

The idea for the expulsion and resettlement of the Jews ...

. The selection of sites, construction of facilities and training of personnel was based on a similar (Action T4

(German, ) was a campaign of mass murder by involuntary euthanasia in Nazi Germany. The term was first used in post-war trials against doctors who had been involved in the killings. The name T4 is an abbreviation of 4, a street address of t ...

) "racial hygiene

The term racial hygiene was used to describe an approach to eugenics in the early 20th century, which found its most extensive implementation in Nazi Germany (Nazi eugenics). It was marked by efforts to avoid miscegenation, analogous to an animal ...

" program of mass murder through involuntary euthanasia, developed in Germany.

Deportation

TheHolocaust train

Holocaust trains were railway transports run by the ''Deutsche Reichsbahn'' national railway system under the control of Nazi Germany and its allies, for the purpose of forcible deportation of the Jews, as well as other victims of the Holoc ...

s increased the scale and duration of the extermination process; and, the enclosed nature of freight cars reduced the troop numbers required to guard them. Rail shipments allowed the Nazi Germans to build and operate larger and more efficient death camps and, at the same time, openly lie to the worldand to their victimsabout a "resettlement" program. An unspecified number of deportees died in transit during Operation Reinhard from suffocation and thirst. They were not supplied with food or water. The ''Güterwagen'' boxcars were only fitted with a bucket latrine

A latrine is a toilet or an even simpler facility that is used as a toilet within a sanitation system. For example, it can be a communal trench in the earth in a camp to be used as emergency sanitation, a hole in the ground ( pit latrine), or ...

. A small barred window provided little ventilation, which often resulted in multiple deaths. A survivor of the Treblinka uprising

Treblinka () was an extermination camp, built and operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland during World War II. It was in a forest north-east of Warsaw, south of the village of Treblinka in what is now the Masovian Voivodeship. The ...

testified about one such train, from Biała Podlaska

Biała Podlaska ( la, Alba Ducalis) is a city in eastern Poland with 56,498 inhabitants as of December 2021. It is situated in the Lublin Voivodeship (since 1999), having previously been the capital of Biała Podlaska Voivodeship (1975–1998). ...

. When the sealed doors flew open, 90 percent of about 6,000 Jewish prisoners were found to have suffocated to death. Their bodies were thrown into smouldering mass grave at the "Lazaret

A lazaretto or lazaret (from it, lazzaretto a diminutive form of the Italian word for beggar cf. lazzaro) is a quarantine station for maritime travellers. Lazarets can be ships permanently at anchor, isolated islands, or mainland buildings. ...

". Millions of people were transported in similar trainsets to the extermination camps under the direction of the German Ministry of Transport, and tracked by an IBM subsidiary, until the official date of closing of the Auschwitz-Birkenau complex in December 1944.

Death factories were only one means of mass extermination. There were secluded killing sites set up further east. At

Death factories were only one means of mass extermination. There were secluded killing sites set up further east. At Bronna Góra

Bronna Góra (or Bronna Mount in English, be, Бронная Гара, ) is the name of a secluded area in present-day Belarus where mass killings of Polish Jews were carried out by Nazi Germany during World War II. The location was part of the ...

(the Bronna Mount, now Belarus) 50,000 Jews were murdered in execution pits; delivered by the Holocaust trains from the ghettos in Brześć

Brest ( be, Брэст / Берасьце, Bieraście, ; russian: Брест, ; uk, Берестя, Berestia; lt, Brasta; pl, Brześć; yi, בריסק, Brisk), formerly Brest-Litovsk (russian: Брест-Литовск, lit=Lithuanian Br ...

, Bereza, Janów Poleski, Kobryń

Kobryn ( be, Кобрын; russian: Кобрин; pl, Kobryń; lt, Kobrynas; uk, Кобринь, Kobryn'; yi, קאָברין) is a city in the Brest Region of Belarus and the center of the Kobryn District. The city is located in the southwes ...

, Horodec (pl), Antopol and other locations along the western border of ''Reichskommissariat Ostland

The Reichskommissariat Ostland (RKO) was established by Nazi Germany in 1941 during World War II. It became the civilian occupation regime in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and the western part of Byelorussian SSR. German planning documents initi ...

''. Explosives were used to reduce the time taken by digging. At the Sosenki Forest on the outskirts of Równe in prewar Wołyń Voivodeship, over 23,000 Jewish adults and children were shot. At the Górka Połonka forest ''(see map)'' 25,000 Jews forced to disrobe and lay over the bodies of others were shot in waves; most of them were deported there via the Łuck Ghetto

The Lutsk Ghetto ( pl, getto w Łucku, german: Ghetto Luzk) was a Nazi ghetto established in 1941 by the SS in Lutsk, Western Ukraine, during World War II. In the interwar period, the city was known as Łuck and was part of the Wołyń Voivodeshi ...

.Yad Vashem, ''Note:'' village Połonka ( pl, Górka Połonka or itPołonka Little Hill

subdivision) is misspelled in the documentary, with testimony of eyewitness Shmuel Shilo. The execution site for the

Lwów Ghetto

, location = Lwów, Zamarstynów( German-occupied Poland)

, date = 8 November 1941 to June 1943

, incident_type = Imprisonment, mass shootings, forced labor, starvation, forced abortions and sterilization

, perpetrators =

, pa ...

inmates was arranged near Janowska, with 35,000–40,000 Jewish victims murdered and buried at the Piaski ravine. ''Also in:''

While the Order Police performed liquidations of the Jewish ghettos in occupied Poland, loading prisoners into railcars and shooting those unable to move or attempting to flee, the collaborationist auxiliary police

The ''Schutzmannschaft'' or Auxiliary Police ( "protective, or guard units"; plural: ''Schutzmannschaften'', abbreviated as ''Schuma'') was the collaborationist auxiliary police of native policemen serving in those areas of the Soviet Union an ...

were used as a means of inflicting terror upon Jews by conducting large-scale massacres in the same locations. They were deployed in all major killing sites of Operation Reinhard (terror was a primary aim of their SS training). The Ukrainian Trawniki men

Trawniki is a village in Świdnik County, Lublin Voivodeship, in eastern Poland. It is the seat of the present-day gmina (administrative district) called Gmina Trawniki. It lies approximately south-east of Świdnik and south-east of the regio ...

formed into units took an active role in the extermination of Jews at Belzec, Sobibór, Treblinka II; during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising; pl, powstanie w getcie warszawskim; german: link=no, Aufstand im Warschauer Ghetto was the 1943 act of Jewish resistance in the Warsaw Ghetto in German-occupied Poland during World War II to oppose Nazi Germany' ...

(on three occasions, see Stroop Report), Częstochowa

Częstochowa ( , ; german: Tschenstochau, Czenstochau; la, Czanstochova) is a city in southern Poland on the Warta River with 214,342 inhabitants, making it the thirteenth-largest city in Poland. It is situated in the Silesian Voivodeship (adm ...

, Lublin

Lublin is the ninth-largest city in Poland and the second-largest city of historical Lesser Poland. It is the capital and the center of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 336,339 (December 2021). Lublin is the largest Polish city east of ...

, Lwów

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in Western Ukraine, western Ukraine, and the List of cities in Ukraine, seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is o ...

, Radom

Radom is a city in east-central Poland, located approximately south of the capital, Warsaw. It is situated on the Mleczna River in the Masovian Voivodeship (since 1999), having previously been the seat of a separate Radom Voivodeship (1975� ...

, Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula, Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland un ...

, Białystok

Białystok is the largest city in northeastern Poland and the capital of the Podlaskie Voivodeship. It is the tenth-largest city in Poland, second in terms of population density, and thirteenth in area.

Białystok is located in the Białystok U ...

(twice), Majdanek, Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 Nazi concentration camps, concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, occupied Poland (in a portion annexed int ...

, the Trawniki concentration camp

The Trawniki concentration camp was set up by Nazi Germany in the village of Trawniki about southeast of Lublin during the occupation of Poland in World War II. Throughout its existence the camp served a dual function. It was organized on the g ...

itself, and the remaining subcamps of KL Lublin/Majdanek camp complex including Poniatowa

Poniatowa is a town in southeastern Poland, in Opole Lubelskie County, in Lublin Voivodship, with 10,500 inhabitants (2006). It belongs to the historic province of Lesser Poland. During the existence of the 17th-century Polish–Lithuanian Common ...

, Budzyń, Kraśnik, Puławy, Lipowa, and also during massacres in Łomazy

Łomazy is a village in Biała Podlaska County, Lublin Voivodeship, in eastern Poland. It is the seat of the gmina (administrative district) called Gmina Łomazy. It lies approximately south of Biała Podlaska and north-east of the regional c ...

, Międzyrzec, Łuków

Łuków is a city in eastern Poland with 30,727 inhabitants (as of January 1, 2005). Since 1999, it has been situated in the Lublin Voivodeship, previously it had belonged to the Siedlce Voivodeship (between 1975–1998). It is the capital of � ...

, Radzyń, Parczew

Parczew is a town in eastern Poland, with a population of 10,281 (2006). It is the capital of Parczew County in the Lublin Voivodeship.

Parczew historically belongs to Lesser Poland (''Małopolska'') region. The town lies 60 kilometers north ...

, Końskowola, Komarówka and all other locations, augmented by members of the SS, SD, Kripo

''Kriminalpolizei'' (, "criminal police") is the standard term for the criminal investigation agency within the police forces of Germany, Austria, and the German-speaking cantons of Switzerland. In Nazi Germany, the Kripo was the criminal poli ...

, as well as the reserve police battalions from Orpo (each, responsible for annihilation of thousands of Jews). In the north-east, the "Poachers' Brigade" of Oskar Dirlewanger trained Belarusian Home Guard in murder expeditions with the help of Belarusian Auxiliary Police

The Belarusian Auxiliary Police ( be, Беларуская дапаможная паліцыя, Biełaruskaja dapamožnaja palicyja; german: Weißruthenische Schutzmannschaften, or Hilfspolizei) was a collaborationist paramilitary force establis ...

. By the end of World War II in Europe

The final battle of the European Theatre of World War II continued after the definitive overall surrender of Nazi Germany to the Allies, signed by Field marshal Wilhelm Keitel on 8 May 1945 in Karlshorst, Berlin. After German dictator Adolf ...

in May 1945, over 90% of Polish Jewry perished.

Chełmno extermination camp

The

The Chełmno extermination camp

, known for =

, location = Near Chełmno nad Nerem, ''Reichsgau Wartheland'' (German-occupied Poland)

, built by =

, operated by =

, commandant = Herbert Lange, Christian Wirth

, original use =

, construction =

, in operatio ...

(german: Kulmhof) was built as the first death camp following Hitler's launch of Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

. It was a pilot project for the development of other extermination sites. The killing method at Chełmno grew out of the 'euthanasia' program in which busloads of unsuspecting hospital patients were gassed in air-tight shower rooms at Bernburg

Bernburg (Saale) is a town in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany, capital of the Salzlandkreis district. The former residence of the Anhalt-Bernburg princes is known for its Renaissance castle.

Geography

The town centre is situated in the fertile Magdeburg ...

, Hadamar

Hadamar is a small town in Limburg-Weilburg district in Hesse, Germany.

Hadamar is known for its Clinic for Forensic Psychiatry/Centre for Social Psychiatry, lying at the edge of town, in whose outlying buildings is also found the Hadamar Mem ...

and Sonnenstein. The killing grounds at Chełmno, from Łódź

Łódź, also rendered in English as Lodz, is a city in central Poland and a former industrial centre. It is the capital of Łódź Voivodeship, and is located approximately south-west of Warsaw. The city's coat of arms is an example of ca ...

, consisted of a vacated manorial estate similar to Sonnenstein, used for undressing (with a truck-loading ramp in the back), as well as a large forest clearing northwest of Chełmno, used for the mass burial as well as open-pit cremation of corpses introduced some time later.

All Jews from the ''Judenfrei

''Judenfrei'' (, "free of Jews") and ''judenrein'' (, "clean of Jews") are terms of Nazi origin to designate an area that has been "cleansed" of Jews during The Holocaust.

While ''judenfrei'' refers merely to "freeing" an area of all of its ...

'' district of ''Wartheland

The ''Reichsgau Wartheland'' (initially ''Reichsgau Posen'', also: ''Warthegau'') was a Nazi German ''Reichsgau'' formed from parts of Polish territory annexed in 1939 during World War II. It comprised the region of Greater Poland and adjacent ...

'' were deported to Chełmno under the guise of 'resettlement'. At least 145,000 prisoners from the Łódź Ghetto

The Łódź Ghetto or Litzmannstadt Ghetto (after the Nazi German name for Łódź) was a Nazi ghetto established by the German authorities for Polish Jews and Roma following the Invasion of Poland. It was the second-largest ghetto in all of ...

were murdered at Chełmno in several waves of deportations lasting from 1942 to 1944. Among those were also approximately 11,000 Jews from Germany, Austria, Czechia and Luxembourg murdered in April 1941 and close to 5,000 Roma from Austria, murdered in January 1942. Almost all victims were murdered with the use of mobile gas van

A gas van or gas wagon (russian: душегубка, ''dushegubka'', literally "soul killer"; german: Gaswagen) was a truck reequipped as a mobile gas chamber. During the World War II Holocaust, Nazi Germany developed and used gas vans on a large ...

s (''Sonderwagen''), which had reconfigured exhaust pipes. In the last phase of the camp's existence, the exhumed bodies were cremated in open-air for several weeks during Sonderaktion 1005

' 1005 (, 'Special Action 1005'), also called ''Aktion'' 1005 or ' (, 'Exhumation Action'), was a top-secret Nazi operation conducted from June 1942 to late 1944. The goal of the project was to hide or destroy any evidence of the mass murder ...

. The ashes, mixed with crushed bones, were trucked every night to the nearby river in sacks made from blankets, to remove the evidence of mass murder.

Auschwitz-Birkenau

The

The Auschwitz concentration camp

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. I ...

was the largest of the German Nazi extermination centers. Located in the Gau Upper Silesia (then part of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

) and west of Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula, Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland un ...

. The overwhelming majority of prisoners deported there were murdered within hours of their arrival. The camp was the location of the first permanent gas chambers

A gas chamber is an apparatus for killing humans or other animals with gas, consisting of a sealed chamber into which a poisonous or asphyxiant gas is introduced. Poisonous agents used include hydrogen cyanide and carbon monoxide.

History ...

in March 1942. The extermination of Jews with Zyklon B

Zyklon B (; translated Cyclone B) was the trade name of a cyanide-based pesticide invented in Germany in the early 1920s. It consisted of hydrogen cyanide (prussic acid), as well as a cautionary eye irritant and one of several adsorbents such ...

as the killing agent began in July. At Birkenau, the four killing installations (each consisting of coatrooms, multiple gas chambers and industrial-scale crematoria) were built in the following year. By late 1943, Birkenau was engaged in industrial-scale murder, with four so-called 'Bunkers' (totaling over a dozen gas chambers) working around the clock. Up to 6,000 people were gassed and cremated there each day, after the ruthless 'selection process' at the ''Judenrampe''. Only about 10 percent of the deportees from transports organized by the Reich Main Security Office (RSHA

The Reich Security Main Office (german: Reichssicherheitshauptamt or RSHA) was an organization under Heinrich Himmler in his dual capacity as ''Chef der Deutschen Polizei'' (Chief of German Police) and '' Reichsführer-SS'', the head of the Naz ...

) were registered and assigned to the Birkenau barracks.

Around 1.1 million people were murdered at Auschwitz. One million of them were Jews from across Europe including 200,000 children. Among the registered 400,000 victims (less than one-third of the total Auschwitz arrivals) were 140,000–150,000 non-Jewish Poles, 23,000 Gypsies, 15,000 Soviet POWs and 25,000 others. Auschwitz received a total of about 300,000 Jews from occupied Poland, shipped aboard freight trains from liquidated ghettos and transit camps, beginning with Bytom

Bytom (Polish pronunciation: ; Silesian: ''Bytōm, Bytōń'', german: Beuthen O.S.) is a city in Upper Silesia, in southern Poland. Located in the Silesian Voivodeship of Poland, the city is 7 km northwest of Katowice, the regional capi ...

(February 15, 1942), Olkusz (three days of June), Otwock

Otwock is a city in east-central Poland, some southeast of Warsaw, with 44,635 inhabitants (2019). Otwock is a part of the Warsaw Agglomeration. It is situated on the right bank of Vistula River below the mouth of Swider River. Otwock is hom ...

(in August), Łomża

Łomża (), in English known as Lomza, is a city in north-eastern Poland, approximately 150 kilometers (90 miles) to the north-east of Warsaw and west of Białystok. It is situated alongside the Narew river as part of the Podlaskie Voivodeship ...

and Ciechanów

Ciechanów is a city in north-central Poland. From 1975 to 1998, it was the capital of the Ciechanów Voivodeship. Since 1999, it has been situated in the Masovian Voivodeship. As of December 2021, it has a population of 43,495.

History

The ...

(November), then Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula, Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland un ...

(March 13, 1943), Auschwitz-Birkenau gas chambers and crematoria were blown up on November 25, 1944, in an attempt to destroy the evidence of mass-murder, by the orders of SS chief Heinrich Himmler.

Treblinka

Designed and built for the sole purpose of exterminating its internees,

Designed and built for the sole purpose of exterminating its internees, Treblinka

Treblinka () was an extermination camp, built and operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland during World War II. It was in a forest north-east of Warsaw, south of the village of Treblinka in what is now the Masovian Voivodeship. The cam ...

was one of only three such facilities in existence; the other two were Bełżec and Sobibór. All of them were situated in wooded areas away from population centres and linked to the Polish rail system by a branch line

A branch line is a phrase used in railway terminology to denote a secondary railway line which branches off a more important through route, usually a main line. A very short branch line may be called a spur line.

Industrial spur

An industr ...

. They had transferable ''SS'' staff. Passports and money were collected for "safekeeping" at a cashier's booth set up by the "Road to Heaven", a fenced-off path leading into the gas chambers disguised as communal showers. Directly behind were the burial pits, dug with a crawler excavator.

Located northeast of

Located northeast of Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officiall ...

, Treblinka became operational on July 24, 1942, after three months of forced labour construction by expellees from Germany. The shipping of Jews from the Polish capital – plan known as the '' Großaktion Warschau'' – began immediately. During two months of the summer of 1942, about 254,000 Warsaw Ghetto

The Warsaw Ghetto (german: Warschauer Ghetto, officially , "Jewish Residential District in Warsaw"; pl, getto warszawskie) was the largest of the Nazi ghettos during World War II and the Holocaust. It was established in November 1940 by the G ...

inmates were exterminated at Treblinka (by some other accounts, at least 300,000). On arrival, the transportees were made to disrobe, then the menfollowed by women and childrenwere forced into double-walled chambers and murdered in batches of 200, with the use of exhaust fumes generated by a tank engine. The gas chambers, rebuilt of brick and expanded during August–September 1942, were capable of murdering 12,000 to 15,000 victims every day, with a maximum capacity of 22,000 executions in twenty-four hours. The dead were initially buried in large mass graves, but the stench from the decomposing bodies could be smelled up to ten kilometers away. As a result, the Nazis began burning the bodies on open-air grids made of concrete pillars and railway tracks. The number of people murdered at Treblinka in about a year ranges from 800,000 to 1,200,000, with no exact figures available. The camp was closed by Globocnik on October 19, 1943, soon after the Treblinka prisoner uprising, with the murderous Operation Reinhard nearly completed.

Bełżec

The

The Bełżec extermination camp

Belzec (English: or , Polish: ) was a Nazi German extermination camp built by the SS for the purpose of implementing the secretive Operation Reinhard, the plan to murder all Polish Jews, a major part of the " Final Solution" which in tota ...

, established near the railroad station of Bełżec in the Lublin District, officially began operation on March 17, 1942, with three temporary gas chambers. Later, they were replaced with six made of brick and mortar, enabling the facility to handle over 1,000 victims at one time. At least 434,500 Jews were murdered there. The lack of verified survivors however, makes this camp little known. The bodies of the dead, buried in mass graves, swelled in the heat as a result of putrefaction

Putrefaction is the fifth stage of death, following pallor mortis, algor mortis, rigor mortis, and livor mortis. This process references the breaking down of a body of an animal, such as a human, post-mortem. In broad terms, it can be view ...

making the earth split, which was resolved with the introduction of crematoria pits in October 1942.

Kurt Gerstein from ''Waffen-SS

The (, "Armed SS") was the combat branch of the Nazi Party's ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with Waffen-SS foreign volunteers and conscripts, volunteers and conscripts from both occup ...

'', supplying Zyklon B

Zyklon B (; translated Cyclone B) was the trade name of a cyanide-based pesticide invented in Germany in the early 1920s. It consisted of hydrogen cyanide (prussic acid), as well as a cautionary eye irritant and one of several adsorbents such ...

from Degesch

The Deutsche Gesellschaft für Schädlingsbekämpfung mbH (), oft shortened to Degesch, was a German chemical corporation which manufactured pesticides. Degesch held the patent on the infamous pesticide Zyklon, a variant of which was used to execu ...

during the Holocaust, wrote after the war in his Gerstein Report

The Gerstein Report was written in 1945 by Kurt Gerstein, ''Obersturmführer'' of the ''Waffen-SS'', who served as Head of Technical Disinfection Services of the SS in World War II and in that capacity supplied the hydrogen cyanide-based pesticide ...

for the Allies

Alliance, Allies is a term referring to individuals, groups or nations that have joined together in an association for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose.

Allies may also refer to:

* Allies of World War I

* Allies of World War II

* F ...

that on August 17, 1942, at Belzec, he had witnessed the arrival of 45 wagons with 6,700 prisoners, of whom 1,450 were already dead inside. That train came with the Jewish people of the Lwów Ghetto

, location = Lwów, Zamarstynów( German-occupied Poland)

, date = 8 November 1941 to June 1943

, incident_type = Imprisonment, mass shootings, forced labor, starvation, forced abortions and sterilization

, perpetrators =

, pa ...

, less than a hundred kilometers away. The last shipment of Jews (including those who had already died in transit) arrived in Bełżec in December 1942. The burning of exhumed corpses continued until March. The remaining 500 ''Sonderkommando

''Sonderkommandos'' (, ''special unit'') were work units made up of German Nazi death camp prisoners. They were composed of prisoners, usually Jews, who were forced, on threat of their own deaths, to aid with the disposal of gas chamber vi ...

'' prisoners who dismantled the camp, and who bore witness to the extermination process, were murdered at the nearby Sobibór extermination camp

Sobibor (, Polish: ) was an extermination camp built and operated by Nazi Germany as part of Operation Reinhard. It was located in the forest near the village of Żłobek Duży in the General Government region of German-occupied Poland.

As a ...

in the following months.

Sobibór

The

The Sobibór extermination camp

Sobibor (, Polish: ) was an extermination camp built and operated by Nazi Germany as part of Operation Reinhard. It was located in the forest near the village of Żłobek Duży in the General Government region of German-occupied Poland.

As a ...

, disguised as a railway transit camp not far from Lublin

Lublin is the ninth-largest city in Poland and the second-largest city of historical Lesser Poland. It is the capital and the center of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 336,339 (December 2021). Lublin is the largest Polish city east of ...

, began mass gassing operations in May 1942. As in other extermination centers, the Jews, taken off the Holocaust trains arriving from liquidated ghettos and transit camps (Izbica

Izbica ( yi, איזשביצע ''Izhbitz, Izhbitze'') is a village in the Krasnystaw County of the Lublin Voivodeship in eastern Poland. It is the seat of the gmina administrative district called Gmina Izbica. It lies approximately south of Kr ...

, Końskowola) were met by a member of SS dressed in a medical coat. ''Oberscharführer'' Hermann Michel gave the command for prisoners' "disinfection".

New arrivals were forced to split into groups, hand over their valuables, and disrobe inside a walled-off courtyard for a bath. Women had their hair cut off by the ''Sonderkommando'' barbers. Once undressed, Jews were led down a narrow path to the gas chambers which were disguised as showers. The victims were murdered with carbon monoxide gas from the exhaust pipes of a gasoline engine removed from a Red Army tank. Their bodies were taken out and burned in open pits over iron grids partly fueled by human body-fat. Their remains were dumped onto seven "ash mountains". The total number of Polish Jews murdered at Sobibór is estimated as at least 170,000..Heinrich Himmler ordered the camp dismantled following a prisoner revolt on October 14, 1943; one of only two successful uprisings by Jewish ''Sonderkommando'' inmates in any extermination camp, with 300 escapees (most of them were recaptured by the SS and killed).

Lublin-Majdanek

The Majdanek

The Majdanek forced labor

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

camp located on the outskirts of Lublin (like Sobibór) and closed temporarily during an epidemic of typhus, was reopened in March 1942 for Operation Reinhard; initially, as a storage depot for valuables stolen from gassed victims at Belzec, Sobibór, and Treblinka, It became a place of extermination of large Jewish populations from south-eastern Poland (Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula, Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland un ...

, Lwów

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in Western Ukraine, western Ukraine, and the List of cities in Ukraine, seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is o ...

, Zamość

Zamość (; yi, זאמאשטש, Zamoshtsh; la, Zamoscia) is a historical city in southeastern Poland. It is situated in the southern part of Lublin Voivodeship, about from Lublin, from Warsaw. In 2021, the population of Zamość was 62,021.

...

, Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officiall ...

) after the gas chambers were constructed in late 1942. The gassing of Polish Jews was performed in plain view of other inmates, without as much as a fence around the killing facilities. According to witness's testimony, "to drown the cries of the dying, tractor engines were run near the gas chambers" before they took the dead away to the crematorium. Majdanek was the site of the murder of 59,000 Polish Jews (from among its 79,000 victims). By the end of Operation ''Aktion Erntefest

Operation Harvest Festival (german: Aktion Erntefest) was the murder of up to 43,000 Jews at the Majdanek, Poniatowa and Trawniki concentration camps by the SS, the Order Police battalions, and the Ukrainian '' Sonderdienst'' on 3–4 Novem ...

'' (Harvest Festival) conducted at Majdanek in early November 1943 (the single largest German massacre of Jews during the entire war), the camp had only 71 Jews left.

Armed resistance and ghetto uprisings

A popular misconception exists that most Jews went to their deaths passively. 10% of the Polish Army which fought alone against the Nazi-Soviet Invasion of Poland were Jewish Poles, some 100,000 troops. Of these, the Germans took 50,000 as prisoners-of-war and did not treat them according to the Geneva Convention; most were sent to concentration camps and then extermination camps. As Poland continued to fight an insurgency war against the occupying powers, other Jews joined the Polish Resistance, sometimes forming exclusively Jewish units.

Jewish resistance to the Nazis comprised their armed struggle, as well as spiritual and cultural opposition which brought dignity despite the inhumane conditions of life in the ghettos. Many forms of resistance existed, even though the elders were terrified by the prospect of mass retaliation against the women and children in the case of anti-Nazi revolt. ''Also in:'' As the German authorities undertook to liquidate the ghettos, armed resistance was offered in over 100 locations on either side of Polish-Soviet border of 1939, overwhelmingly in eastern Poland. ''Also in:'' Uprisings erupted in 5 major cities, 45 provincial towns, 5 major concentration and extermination camps, as well as in at least 18 forced labor camps.. Significantly, the only rebellions in

A popular misconception exists that most Jews went to their deaths passively. 10% of the Polish Army which fought alone against the Nazi-Soviet Invasion of Poland were Jewish Poles, some 100,000 troops. Of these, the Germans took 50,000 as prisoners-of-war and did not treat them according to the Geneva Convention; most were sent to concentration camps and then extermination camps. As Poland continued to fight an insurgency war against the occupying powers, other Jews joined the Polish Resistance, sometimes forming exclusively Jewish units.

Jewish resistance to the Nazis comprised their armed struggle, as well as spiritual and cultural opposition which brought dignity despite the inhumane conditions of life in the ghettos. Many forms of resistance existed, even though the elders were terrified by the prospect of mass retaliation against the women and children in the case of anti-Nazi revolt. ''Also in:'' As the German authorities undertook to liquidate the ghettos, armed resistance was offered in over 100 locations on either side of Polish-Soviet border of 1939, overwhelmingly in eastern Poland. ''Also in:'' Uprisings erupted in 5 major cities, 45 provincial towns, 5 major concentration and extermination camps, as well as in at least 18 forced labor camps.. Significantly, the only rebellions in Nazi camps

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps, (officially) or (more commonly). The Nazi concentration camps are distinguished from other types of Nazi camps such as forced-labor camps, as well as con ...

were Jewish..

The Nieśwież Ghetto insurgents in eastern Poland fought back on July 22, 1942. The Łachwa Ghetto

Łachwa (or Lakhva) Ghetto was a Nazi ghetto in Western Belarus during World War II. Located in Lakhva, Belarus), the ghetto was created with the aim of persecution and exploitation of the local Jews. The ghetto existed until September 1942 ...

revolt erupted on September 3. On October 14, 1942, the Mizocz Ghetto followed suit. The Warsaw Ghetto

The Warsaw Ghetto (german: Warschauer Ghetto, officially , "Jewish Residential District in Warsaw"; pl, getto warszawskie) was the largest of the Nazi ghettos during World War II and the Holocaust. It was established in November 1940 by the G ...

firefight

Firefight or fire fight may refer to:

* Firefighting, process of extinguishing destructive flames

* Shootout or firefight, a gun battle between armed groups

Entertainment and media

* '' Fire Fight'', an isometric shooter produced by Epic MegaGam ...

of January 18, 1943, led to the largest Jewish uprising of World War II launched on April 19, 1943. On June 25, the Jews of the Częstochowa Ghetto rose up. At Treblinka

Treblinka () was an extermination camp, built and operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland during World War II. It was in a forest north-east of Warsaw, south of the village of Treblinka in what is now the Masovian Voivodeship. The cam ...

, the ''Sonderkommando

''Sonderkommandos'' (, ''special unit'') were work units made up of German Nazi death camp prisoners. They were composed of prisoners, usually Jews, who were forced, on threat of their own deaths, to aid with the disposal of gas chamber vi ...

'' prisoners armed with stolen weapons attacked the guards on August 2, 1943. A day later, the Będzin

Będzin (; also ''Bendzin'' in English; german: Bendzin; yi, בענדין, Bendin) is a city in the Dąbrowa Basin, in southern Poland. It lies in the Silesian Highlands, on the Czarna Przemsza River (a tributary of the Vistula). Even though pa ...

and Sosnowiec

Sosnowiec is an industrial city county in the Dąbrowa Basin of southern Poland, in the Silesian Voivodeship, which is also part of the Silesian Metropolis municipal association.—— Located in the eastern part of the Upper Silesian Indus ...

ghetto revolts broke out. On August 16, the Białystok Ghetto uprising erupted. The revolt in Sobibór extermination camp occurred on October 14, 1943. At Auschwitz-Birkenau

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 Nazi concentration camps, concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, occupied Poland (in a portion annexed int ...

, the insurgents blew up one of Birkenau's crematoria on October 7, 1944. Similar resistance was offered in Łuck, Mińsk Mazowiecki

Mińsk Mazowiecki () "''Masovian Minsk''") is a town in eastern Poland with 40,999 inhabitants (2020). It is situated in the Masovian Voivodeship (since 1999) and is a part of the Warsaw Agglomeration. It is the capital of Mińsk County. Loca ...

, Pińsk, Poniatowa

Poniatowa is a town in southeastern Poland, in Opole Lubelskie County, in Lublin Voivodship, with 10,500 inhabitants (2006). It belongs to the historic province of Lesser Poland. During the existence of the 17th-century Polish–Lithuanian Common ...

, and in Wilno

Vilnius ( , ; see also #Etymology and other names, other names) is the capital and List of cities in Lithuania#Cities, largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the munic ...

.

Poles and Jews

Polish nationals are the largest group by nationality with the title ofRighteous Among the Nations

Righteous Among the Nations ( he, חֲסִידֵי אֻמּוֹת הָעוֹלָם, ; "righteous (plural) of the world's nations") is an honorific used by the State of Israel to describe non-Jews who risked their lives during the Holocaust to sa ...

, as honored by Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem ( he, יָד וַשֵׁם; literally, "a memorial and a name") is Israel's official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust. It is dedicated to preserving the memory of the Jews who were murdered; honoring Jews who fought against th ...

. In light of the harsh punishments imposed by the German on rescuers, Yad Vashem calls the number of Polish Righteous "impressive". According to Gunnar S. Paulsson it is probable that these recognized Poles, over 6,000, "represent only the tip of the iceberg" of Polish rescuers. Some Jews received organized help from Żegota

Żegota (, full codename: the "Konrad Żegota Committee"Yad Vashem Shoa Resource CenterZegota/ref>) was the Polish Council to Aid Jews with the Government Delegation for Poland ( pl, Rada Pomocy Żydom przy Delegaturze Rządu RP na Kraj), an un ...

(The Council to Aid Jews), an underground organization of Polish resistance in German-occupied Poland

German-occupied Poland during World War II consisted of two major parts with different types of administration.

The Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany following the invasion of Poland at the beginning of World War II—nearly a quarter of the ...

.Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem ( he, יָד וַשֵׁם; literally, "a memorial and a name") is Israel's official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust. It is dedicated to preserving the memory of the Jews who were murdered; honoring Jews who fought against th ...

Shoa Resource CenterZegota