History of violence against LGBT people in the United Kingdom on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of

The history of

In May 1999, the Admiral Duncan, a gay

In May 1999, the Admiral Duncan, a gay

In 2019, a lesbian couple Melania Geymonat, 28, and Chris (surname unknown, 29) were harassed and assaulted during the early morning of 30 May, on a London bus. Reportedly, four teenagers (ages 15–18) began harassing the pair after discovering their couplehood, proceeding to ask them to kiss, making sexual gestures, discussing sex positions, and throwing coins. The scene escalated and both women were significantly beaten, first Chris, then Melania, along with belongings stolen. Both were later taken to hospital for facial injuries. Photos released show both women covered in their own blood. The four teenagers have been arrested for the assault. London mayor

Hate crimes against transgender people in England, Scotland and Wales, as recorded by police, increased 81% from the 2016-17 fiscal year (1,073 crimes) to the 2018-19 fiscal year (1,944 crimes).

The history of

The history of violence against LGBT people

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people frequently experience violence directed toward their sexuality, gender identity, or gender expression. This violence may be enacted by the state, as in laws prescribing punishment for hom ...

in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

is made up of assaults on gay men, lesbians

A lesbian is a homosexual woman.Zimmerman, p. 453. The word is also used for women in relation to their sexual identity or sexual behavior, regardless of sexual orientation, or as an adjective to characterize or associate nouns with femal ...

, bisexual, transgender

A transgender (often abbreviated as trans) person is someone whose gender identity or gender expression does not correspond with their sex assigned at birth. Many transgender people experience dysphoria, which they seek to alleviate through ...

, queer and intersex

Intersex people are individuals born with any of several sex characteristics including chromosome patterns, gonads, or genitals that, according to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, "do not fit typical bin ...

ed individuals (LGBTQI

' is an initialism that stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender. In use since the 1990s, the initialism, as well as some of its common variants, functions as an umbrella term for sexuality and gender identity.

The LGBT term is a ...

), legal responses to such violence, and hate crime statistics in the United Kingdom. Those targeted by such violence are perceived to violate heteronormative rules and religious beliefs and contravene perceived protocols of gender

Gender is the range of characteristics pertaining to femininity and masculinity and differentiating between them. Depending on the context, this may include sex-based social structures (i.e. gender roles) and gender identity. Most cultures ...

and sexual roles. People who are perceived to be LGBTQI may also be targeted.

Prior to 1900

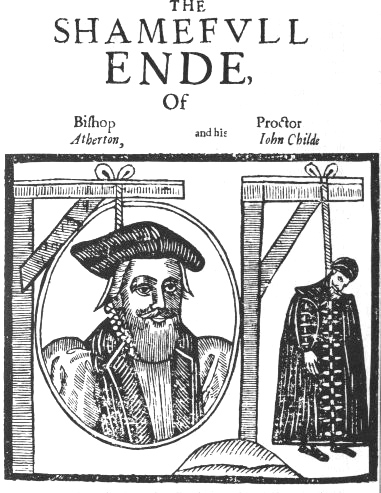

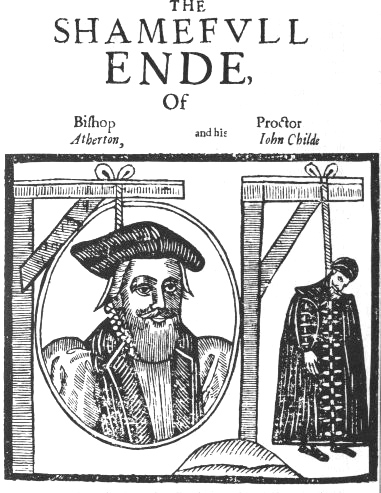

The first English law against homosexuality was theBuggery Act 1533

The Buggery Act 1533, formally An Acte for the punishment of the vice of Buggerie (25 Hen. 8 c. 6), was an Act of the Parliament of England that was passed during the reign of Henry VIII.

It was the country's first civil sodomy law, such offe ...

, which made male homosexual acts punishable by death

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

; typically hanging

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging ...

. It was established during the reign of Henry VIII, and was the first civil legislation applicable against sodomy in the country, such offences having previously been dealt with by ecclesiastical courts. The law defined buggery as an unnatural sexual act against the will of God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

and man. This was later defined by the courts to include only anal penetration and bestiality.''R v Jacobs'' (1817) Russ & Ry 331 confirmed that buggery related only to intercourse '' per anum'' by a man with a man or woman, or intercourse ''per anum'' or ''per vaginam

Per is a Latin preposition which means "through" or "for each", as in per capita.

Per or PER may also refer to:

Places

* IOC country code for Peru

* Pér, a village in Hungary

* Chapman code for Perthshire, historic county in Scotland

Math ...

'' by either a man or a woman with an animal. Other forms of "unnatural intercourse" may amount to indecent assault

Indecent assault is an offence of aggravated assault in some common law-based jurisdictions. It is characterised as a sex crime and has significant overlap with offences referred to as sexual assault.

England and Wales

Indecent assault was a broa ...

or gross indecency, but do not constitute buggery (see generally: Smith & Hogan, ''Criminal Law'' (10th ed.) )

The Act was repealed by section 1 of the Offences against the Person Act 1828

The Offences Against the Person Act 1828 (9 Geo. 4 c. 31) (also known as Lord Lansdowne's Act) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It consolidated provisions in the law related to offences against t ...

(9 Geo.4 c.31) and by section 125 of the Criminal Law (India) Act 1828 (c.74). It was replaced by section 15 of the Offences against the Person Act 1828, and section 63 of the Criminal Law (India) Act 1828, which provided that buggery would continue to be a capital offence

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

. In the period from 1810 to 1835, 46 people convicted of sodomy were hanged and 32 sentenced to death but reprieved. A further 716 were imprisoned or sentenced to the pillory, before its use was restricted in 1816. The last executions were the hangings of James Pratt and John Smith, on 27 November 1835.

Buggery remained a capital offence in England and Wales until the enactment of the Offences against the Person Act 1861; However, male homosexual acts still remained illegal and were punishable by imprisonment and in 1885 section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885

The Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 ( 48 & 49 Vict. c.69), or "An Act to make further provision for the Protection of Women and Girls, the suppression of brothels, and other purposes," was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, the lat ...

extended the laws regarding homosexuality to include any kind of sexual activity between males. Lesbians were never acknowledged or targeted by legislation.

1900–1967

Into the 1900s, homosexual activity remained illegal and punishable by imprisonment. In the early-1950s, the police actively enforced laws prohibiting sexual behaviour between men. This policy led to a number of high-profile arrests and trials. One of those involved the noted computer scientist, mathematician, and war-time code-breakerAlan Turing

Alan Mathison Turing (; 23 June 1912 – 7 June 1954) was an English mathematician, computer scientist, logician, cryptanalyst, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. Turing was highly influential in the development of theoretical co ...

(1912–1954), convicted in 1952 of "gross indecency". Turing was given a choice between imprisonment or probation conditional on his agreement to undergo hormonal

A hormone (from the Greek participle , "setting in motion") is a class of signaling molecules in multicellular organisms that are sent to distant organs by complex biological processes to regulate physiology and behavior. Hormones are required f ...

treatment designed to reduce his libido

Libido (; colloquial: sex drive) is a person's overall sexual drive or desire for sexual activity. Libido is influenced by biological, psychological, and social factors. Biologically, the sex hormones and associated neurotransmitters that act u ...

. He accepted chemical castration

Chemical castration is castration via anaphrodisiac drugs, whether to reduce libido and sexual activity, to treat cancer, or otherwise. Unlike surgical castration, where the gonads are removed through an incision in the body,

via oestrogen hormone injections.

Much lesser-known individuals were also victims of the law and of violent crime perpetrated by their fellow countrymen. On 31 July 1950, in Rotherham

Rotherham () is a large minster and market town in South Yorkshire, England. The town takes its name from the River Rother which then merges with the River Don. The River Don then flows through the town centre. It is the main settlement of ...

, an English schoolteacher, Kenneth Crowe, aged 37, was found dead wearing his wife's clothes and a wig. He had approached a miner on his way home from the pub, who upon discovering Crowe was male, beat and strangled him. John Cooney was found not guilty of murder and sentenced to five years for manslaughter.

In response to the violence and unfair treatment of gay men, the Sexual Offences Act 1967

The Sexual Offences Act 1967 is an Act of Parliament in the United Kingdom (citation 1967 c. 60). It legalised homosexual acts in England and Wales, on the condition that they were consensual, in private and between two men who had attained t ...

was passed. It maintained the general prohibitions on buggery and indecency between men, but provided for a limited decriminalisation of homosexual acts where three conditions were fulfilled. Those conditions were that the act had to be consensual, take place in private and involve only people that had attained the age of 21. This was a higher age of consent than that for heterosexual acts, which was set at 16. Further, "in private" limited participation in an act to two people. This condition was interpreted strictly by the courts, which took it to exclude acts taking place in a room in a hotel, for example, and in private homes where a third person was present (even if that person was in a different room).

The Sexual Offences Act 1967 extended only to England and Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

, and not to Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

, Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

, the Channel Islands

The Channel Islands ( nrf, Îles d'la Manche; french: îles Anglo-Normandes or ''îles de la Manche'') are an archipelago in the English Channel, off the French coast of Normandy. They include two Crown Dependencies: the Bailiwick of Jersey, ...

or the Isle of Man

)

, anthem = "O Land of Our Birth"

, image = Isle of Man by Sentinel-2.jpg

, image_map = Europe-Isle_of_Man.svg

, mapsize =

, map_alt = Location of the Isle of Man in Europe

, map_caption = Location of the Isle of Man (green)

in Europe ...

, where all homosexual behaviour remained illegal.

1989–1990: West London murders

Towards the end of 1989 and the start of 1990, there were a series of unsolved murders in west London over a period of six months. In September 1989, Christopher Schliach, a barrister who was gay, was murdered in his home; he was stabbed more than 40 times. Three months later, Henry Bright, a hotelier who was gay, was also stabbed to death at his home. A month later, William Dalziel, a hotel porter who was gay, was found unconscious on a roadside in Acton, west London. He died from severe head injuries. Three months after this, actor Michael Boothe was murdered in west London (see below 2007 Met review). In July 1990, following these murders, hundreds of lesbians and gay men marched from the park where Boothe had been killed to Ealing Town Hall and held a candlelit vigil. The demonstration led to the formation of OutRage, who called for the police to start protecting gay men instead of arresting them. In September 1990, lesbian and gay police officers established the Lesbian and Gay Police Association (Lagpa/GPA).1999: The Admiral Duncan pub bombing

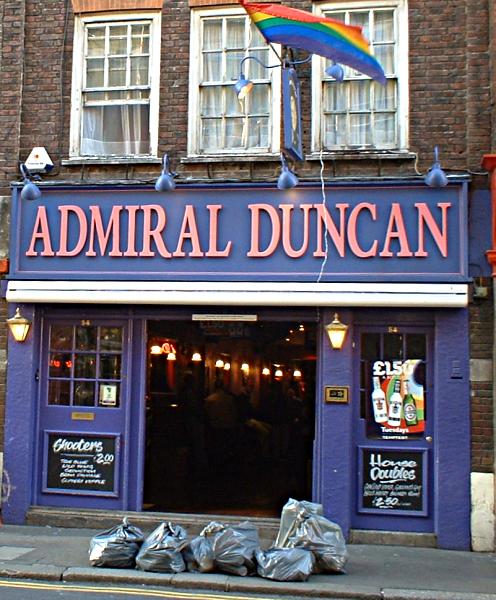

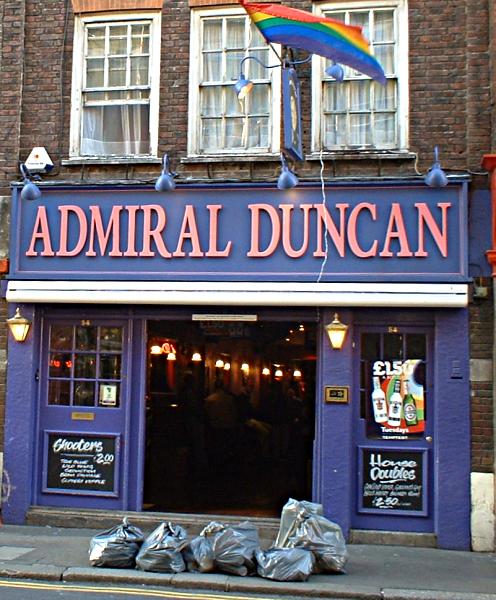

In May 1999, the Admiral Duncan, a gay

In May 1999, the Admiral Duncan, a gay pub

A pub (short for public house) is a kind of drinking establishment which is licensed to serve alcoholic drinks for consumption on the premises. The term ''public house'' first appeared in the United Kingdom in late 17th century, and was ...

in Soho

Soho is an area of the City of Westminster, part of the West End of London. Originally a fashionable district for the aristocracy, it has been one of the main entertainment districts in the capital since the 19th century.

The area was develo ...

was bombed by former British National Party member David Copeland

The 1999 London nail bombings were a series of bomb explosions in London, England. Over three successive weekends between 17 and 30 April 1999, homemade nail bombs were detonated respectively in Brixton in South London; at Brick Lane, Spitalfiel ...

, killing three people and wounding at least 70.

2002: CPS 'zero tolerance'

On 27 November 2002, theCrown Prosecution Service

The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) is the principal public agency for conducting criminal prosecutions in England and Wales. It is headed by the Director of Public Prosecutions.

The main responsibilities of the CPS are to provide legal advi ...

announced a 'zero tolerance' approach towards perpetrators of anti-gay offences; this also covers crimes against transgender peoples. Crimes considered 'homophobic' or 'transphobic' are to be assessed in a similar way to those considered racist (e.g. the victim regarding them as such). "There is no statutory definition of a homophobic or transphobic incident. However, when prosecuting such cases, and to help us to apply our policy on dealing with cases with a homophobic or transphobic element, we adopt the following definition: 'Any incident which is perceived to be homophobic or transphobic by the victim or by any other person.'"

2003: Criminal Justice Act

TheCriminal Justice Act 2003

The Criminal Justice Act 2003 (c. 44) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is a wide-ranging measure introduced to modernise many areas of the criminal justice system in England and Wales and, to a lesser extent, in Scotland a ...

is passed, in which section 146 empowers courts in England and Wales to impose tougher sentences for offences motivated or aggravated by the victim's sexual orientation.

2006: first prosecution for homophobic murder

On 14 October 2005, London, Jody Dobrowski was beaten to death onClapham Common

Clapham Common is a large triangular urban park in Clapham, south London, England. Originally common land for the parishes of Battersea and Clapham, it was converted to parkland under the terms of the Metropolitan Commons Act 1878. It is of g ...

by two men who perceived him as being gay; Dobrowski was beaten so badly he had to be identified by his fingerprints. Thomas Pickford and Scott Walker were given life sentences in what was described as a 'homophobic murder' in June 2006. This was the first prosecution in England and Wales where Section 146 of the Criminal Justice Act 2003

The Criminal Justice Act 2003 (c. 44) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is a wide-ranging measure introduced to modernise many areas of the criminal justice system in England and Wales and, to a lesser extent, in Scotland a ...

was used in sentencing the killers; this enabled the courts to impose a tougher sentence for offences motivated or aggravated by the victim's sexual orientation, in this case a minimum of 30 years in prison.

In 2007, UK's Channel 4

Channel 4 is a British free-to-air public broadcast television network operated by the state-owned Channel Four Television Corporation. It began its transmission on 2 November 1982 and was established to provide a fourth television service ...

released ''Clapham Junction

Clapham Junction is an urban locality around Clapham Junction railway station in London, England. Despite its name, it is not located in Clapham, but forms the commercial centre of Battersea.

Clapham Junction was a scene of disturbances during ...

'', a TV drama partially based on the murder. The film written by Kevin Elyot

Kevin Elyot (18 July 1951 – 7 June 2014) was a British playwright, screenwriter and actor. His most notable works include the play ''My Night with Reg'' (1994) and the film ''Clapham Junction'' (2007). His stage work has been performed by lea ...

and directed by Adrian Shergold

Adrian Shergold (born 24 March 1948 in Croydon, Surrey) is a British film and television director.

Selected filmography

*'' Danielle Cable: Eyewitness'' (2003)

*'' Dirty Filthy Love'' (2004)

*''Ahead of the Class'' (2005)

*'' Pierrepoint'' (2005)

...

portrays to some detail the victim Jody Dobrowski. In the script to the film however, the Clapham Common's victim's name was changed to Alfie Cartwright, a waiter. The role was played by actor David Leon. The film was shown for the first time on 22 July 2007, on Channel 4, almost two years after the murder, to mark the 40th anniversary of decriminalisation of homosexuality in England and Wales, and was meant to be a film against violence against gay people and hate crimes based on sexual orientation. It was shown a second time on More4

More4 is a British free-to-air television channel, owned by Channel Four Television Corporation. The channel launched on 10 October 2005. Its programming mainly focuses on lifestyle and documentaries, as well as foreign dramas.

Content

When ...

, just a few days later, on 30 July 2007.

2007: Metropolitan Police review

In July 2004 an independent inquiry into police procedures carried out by the independent Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Advisory Group for the Metropolitan Police was announced. In May 2007 the report for the independent review was released; it had examined how detectives had handled 10 murders of gay men or transsexuals. The report found that some police inquiries were hampered by lack of knowledge, reliance on unfounded stereotypes and personal prejudices; these problems were mirrored and exacerbated by media coverage. The review recognised that Scotland Yard's work with the gay, lesbian and transsexual communities and its investigative processes had improved significantly since the 1990s, but warned that more radical steps were needed. The cases reviewed, and the findings, included: * Actor Michael Boothe, in west London died in April 1990, beaten to death by a gang of up to six men close to a public lavatory. The police said he had been the victim of "an extraordinarily severe beating, of a merciless and savage nature". He managed to give a description of his attackers before he died, and a reward of £15,000 was offered, but no one was caught, and the crime remains unsolved. The police review identified institutional homophobia within the Metropolitan Police as a factor. * Colin Ireland, age 43, who in 1993 was jailed for life for murdering five gay men. Ireland picked up the men at pubs in London, and then killed them in their own homes. A Scotland Yard review showed that Ireland's capture was hampered by institutional homophobia within the Metropolitan Police. ** Andrew Collier, a housing warden, aged 33, was one of Ireland's victims; the murder was classified as homophobic and linked with the death of Peter Walker, Ireland's first victim. The report said the police could have done more to warn the community of the links between the murders. ** Emanuel Spiteri, age 41, who was strangled to death in his flat in Catford by Ireland, after meeting in a pub in Earls Court, west London. * Robyn Brown, a 23-year-old transsexual prostitute, was found stabbed to death in her flat in London on 28 February 1997. The original report described her as being 23-year-old Gemma Browne, formerly James Darwin Browne. The case went cold for over ten years, but her killer, James Hopkins, was eventually caught; in January 2009 he was jailed for life. The report found that identifying her to the public using different names may have hampered attempts to connect with relevant communities. * Jaap Bornkamp, a 52-year-old florist, was knifed in June 2000 in south-east London in a homophobic attack; the murder remains unsolved despite the police displaying 20 ft by 10 ft images of CCTV footage taken near the murder scene. He was attacked after leaving a night club, and the police are reported as saying there was no confrontation or argument, but that the attack was homophobic and unprovoked. The report found this case to have been a model of police good practice. * Geoffrey Windsor, 57, in south London died in June 2002 from head injuries in a park after he was beaten and robbed. The police said the murder was motivated by homophobia. A review of this and similar cases in the area highlighted poor policing due to institutional homophobia within the police, particularly in not taking previous attacks in the area more seriously.2000–2009

Damilola Taylor

Damilola Adegbite (born Oluwadamilola Adegbite; 18 May 1985) is Nigerian actress, Model, and Television personality. She played Thelema Duke in the soap opera ''Tinsel'', and Kemi Williams in the movie '' Flower Girl''. She won Best Actress in a T ...

was attacked by a local gang of youths on 27 November 2000 in Peckham, south London; he bled to death after being stabbed with a broken bottle in the thigh, which severed the femoral artery. BBC News

BBC News is an operational business division of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) responsible for the gathering and broadcasting of news and current affairs in the UK and around the world. The department is the world's largest broad ...

, '' Daily Telegraph'', '' Guardian'' and ''Independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independ ...

'' newspapers reported at the time that during the weeks between arriving in the UK from Nigeria and the attack he had been subjected to bullying and beating, which included homophobic remarks by a group of boys at his school. "The bullies told him that he was gay." He "may not have understood why he was being bullied at school, or why some other children taunted him about being 'gay' – the word meant nothing to him." He had to ask his mother what 'gay' meant, she said "Boys were swearing at him, saying lots of horrible words. They were calling him names." His mother had spoken about this bullying, but the teachers failed to take it seriously. "She said pupils had accused her son of being gay and had beaten him last Friday." Six months after the murder, his father said, "I spoke to him and he was crying that he was being bullied and being called names. He was being called 'gay'." In the ''New Statesman

The ''New Statesman'' is a British Political magazine, political and cultural magazine published in London. Founded as a weekly review of politics and literature on 12 April 1913, it was at first connected with Sidney Webb, Sidney and Beatrice ...

'' two years later, when there had still been no convictions for the crime, Peter Tatchell

Peter Gary Tatchell (born 25 January 1952) is a British human rights campaigner, originally from Australia, best known for his work with LGBT social movements.

Tatchell was selected as the Labour Party's parliamentary candidate for Bermondsey ...

, gay human rights campaigner, said, "In the days leading up to his murder in south London in November 2000, he was subjected to vicious homophobic abuse and assaults," and asked why the authorities had ignored this before and after his death.

In July 2005, Lauren Harries

Lauren Charlotte Harries (born James Charles Harries; 6 March 1978) is an English media personality. As a child she was known for her knowledge of antiques, appearing on numerous television shows including ''Wogan'' and '' After Dark''. In l ...

, a trans woman, was attacked along with her father and brother in their home in Cardiff

Cardiff (; cy, Caerdydd ) is the capital and largest city of Wales. It forms a principal area, officially known as the City and County of Cardiff ( cy, Dinas a Sir Caerdydd, links=no), and the city is the eleventh-largest in the United Kingd ...

by eight youths who shouted the word "tranny" while beating their victims. One youth pleaded guilty to inflicting grievous bodily harm and was sentenced to two years probation; his accomplices were not formally identified or charged.

In April 2006 a man was jailed for a homophobic attack on an openly gay Anglican priest. Rev Dr Barry Rathbone was sitting in a park in Bournemouth, Dorset when Martin Powell and his girlfriend approached and spoke to him. Rathbone informed them that it was a cruising area, then Powell produced a metal baseball bat, called him a 'queer', and started to hit him.

On 25 July 2008, 18-year-old Michael Causer was attacked by a group of men at a party in Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a populat ...

, and died from his injuries. It is alleged that he was killed because he was gay. On 23 October 2008, 23-year-old gay hairdresser

A hairdresser is a person whose occupation is to cut or style hair in order to change or maintain a person's image. This is achieved using a combination of hair coloring, haircutting, and hair texturing techniques. A Hairdresser may also be re ...

Daniel Jenkinson was the victim of a homophobic attack in a Preston club. His attacker, Neil Bibby, also from Preston, was sentenced to 200 hours' unpaid work, a three-month weekend curfew

A curfew is a government order specifying a time during which certain regulations apply. Typically, curfews order all people affected by them to ''not'' be in public places or on roads within a certain time frame, typically in the evening and ...

, and ordered to pay £2,000 compensation after he pleaded guilty to assault. Daniel needed facial reconstruction surgery after the attack, and said he was too scared to go out in the city.

On 3 March 2009 in Bromley

Bromley is a large town in Greater London, England, within the London Borough of Bromley. It is south-east of Charing Cross, and had an estimated population of 87,889 as of 2011.

Originally part of Kent, Bromley became a market town, c ...

, south London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, 59-year-old Gerry Edwards was stabbed to death by an assailant shouting homophobic abuse. His partner of over twenty years, 56-year-old Chris Bevan, was also stabbed and admitted to hospital in a critical condition. The police dealing with the case said they had an open mind, but were treating it as a homophobic murder. Two men were subsequently arrested.

On 15 May 2009, An English court found two football fans guilty of shouting homophobic chants at footballer Sol Campbell during a match This was the first prosecution for indecent chanting in the UK. The police reported that up to 2,500 fans shouted chants at the match that included "Sol, Sol, wherever you may be, Not long now until lunacy, We won't give a fuck if you are hanging from a tree," the footballer commented "I felt totally victimised and helpless by the abuse I received on this day. It has had an effect on me personally". Three men and two boys were given cautions after the match.

In September 2009, 62-year-old Ian Baynham was attacked outside South Africa House in Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster, Central London, laid out in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. At its centre is a high column bearing a statue of Admiral Nelson comm ...

in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

by three youths shouting homophobic abuse. Joel Alexander and Ruby Thomas were found guilty of manslaughter at the Old Bailey and sentenced to six and seven years imprisonment respectively. A third accomplice, Rachael Burke was found guilty of a lesser charge of affray

In many legal jurisdictions related to English common law, affray is a public order offence consisting of the fighting of one or more persons in a public place to the terror (in french: à l'effroi) of ordinary people. Depending on their act ...

and sentenced to two years of imprisonment.

2010 onwards

In 2012, Giovanna Del Nord, a 46-year-old trans woman, was attacked minutes after entering The Market Tavern, a pub in Leicester city centre. Without warning she was punched in the head and knocked unconscious. She later on changed her name (twice) and moved toGibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

, then to Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

and in 2020; to live in Sweden.

In June 2012, Steven Simpson, an autistic, openly gay 18-year-old, had homophobic slurs written on his body and was set on fire at his birthday party by Jordan Sheard, 20, who was sentenced to 3 years in jail in March 2013. A vigil was held for Simpson in Sheffield

Sheffield is a city in South Yorkshire, England, whose name derives from the River Sheaf which runs through it. The city serves as the administrative centre of the City of Sheffield. It is historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire a ...

on 9 April 2013, and gay rights organisation Stonewall successfully wrote to the Attorney General asking for a review of the case.

In 2017, a 36-year-old man was attacked by 29-year-old Kamil Wladyslaw Snios in Tottenham, London. The attacker later made a number of homophobic remarks during police interview and cited homosexuality as a reason for attack. The victim was treated for four fractures to his right leg. Kamil Snios has been sentenced to 10 years in prison.

In 2018, homophobic and transphobic hate crime was at record levels in Merseyside

Merseyside ( ) is a metropolitan and ceremonial county in North West England, with a population of 1.38 million. It encompasses both banks of the Mersey Estuary and comprises five metropolitan boroughs: Knowsley, St Helens, Sefton, Wi ...

. Hate crimes increased dramatically since Michael Causer's death in 2008. Of the figures retrieved by the BBC, more than half of the 442 reported victims in 2017 were under 35 years of age, and more than 50 of the crimes were against people under 18 years of age. A number of factors may have contributed to the rise, including improved reporting by LGBT people. However, the number of offenders being brought to justice did not increase commensurately with the number of hate crimes recorded. It was reported that only one in five homophobic hate crimes are now solved. "Merseyside police told BBC Three there has been a 38% rise in trans hate crime since last year, with most victims aged between 26–35".

In December 2018, it was reported that according to data from Freedom of Information responses received from 38 police forces across England, Scotland and Wales, Merseyside has the highest rate of recorded homophobic hate crimes.

In 2019, Matthew, 23, and his partner were ‘being affectionate’ at a bus stop in Brixton Road, Lambeth, on January 19 when they were assaulted in a homophobic attack. The gay couple feared they would go blind after being pepper sprayed in the face. Matthew recalls his attacker, who was with a group of four other men, say ‘we don’t want your kind around here�In 2019, a lesbian couple Melania Geymonat, 28, and Chris (surname unknown, 29) were harassed and assaulted during the early morning of 30 May, on a London bus. Reportedly, four teenagers (ages 15–18) began harassing the pair after discovering their couplehood, proceeding to ask them to kiss, making sexual gestures, discussing sex positions, and throwing coins. The scene escalated and both women were significantly beaten, first Chris, then Melania, along with belongings stolen. Both were later taken to hospital for facial injuries. Photos released show both women covered in their own blood. The four teenagers have been arrested for the assault. London mayor

Sadiq Khan

Sadiq Aman Khan (; born 8 October 1970) is a British politician serving as Mayor of London since 2016. He was previously Member of Parliament (MP) for Tooting from 2005 until 2016. A member of the Labour Party, Khan is on the party's sof ...

and then-Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn

Jeremy Bernard Corbyn (; born 26 May 1949) is a British politician who served as Leader of the Opposition and Leader of the Labour Party from 2015 to 2020. On the political left of the Labour Party, Corbyn describes himself as a socialist ...

have both spoke out against the beating.

In 2021, a murderer who bludgeoned a 69-year-old retiree to death with a hammer told psychiatrists he would never have stopped killing gay men if he had not been caught. "Remorseless" David Iwo, 23, advertised his services for sex online and tricked former Crown Prosecution Service lawyer Martin Decker into arranging a meeting at his flat in Vyner Croft, Prenton, on the evening of March 6 this yearHate crimes against transgender people in England, Scotland and Wales, as recorded by police, increased 81% from the 2016-17 fiscal year (1,073 crimes) to the 2018-19 fiscal year (1,944 crimes).

See also

*LGBT rights in the United Kingdom

The rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland have varied over time.

Prior to the formal introduction of Christianity in Britain in 597 AD, when Augustine of Ca ...

* Muslim patrol incidents in London

Notes

References

{{LGBT , social=expandedViolence

Violence is the use of physical force so as to injure, abuse, damage, or destroy. Other definitions are also used, such as the World Health Organization's definition of violence as "the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened ...

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...