History of urban planning on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of urban planning is a technical and political process concerned with the use of land and design of the urban environment, including air, water, and the infrastructure passing into and out of urban areas such as transportation and distribution networks.

The history of

Traditionally, the Greek philosopher

Traditionally, the Greek philosopher

After the gradual disintegration and fall of the West-Roman empire in the 5th century and the devastation by the invasions of Huns, Germanic peoples, Byzantines, Moors, Magyars, and Normans in the next five centuries, little remained of urban culture in western and central Europe.

In the 10th and 11th centuries, though, there appears to have been a general improvement in the political stability and economy. This made it possible for trade and craft to grow and for the monetary economy and urban culture to revive. Initially, urban culture recovered particularly in existing settlements, often in remnants of Roman towns and cities, but later on, ever more towns were created anew. Meanwhile, the population of western Europe increased rapidly and the utilised agricultural area grew with it. The agricultural areas of existing villages were extended and new villages and towns were created in uncultivated areas as cores for new reclamations.

Urban development in the early Middle Ages, characteristically focused on a fortress, a fortified abbey, or a (sometimes abandoned) Roman nucleus, occurred "like the annular rings of a tree", whether in an extended village or the centre of a larger city. Since the new centre was often on high, defensible ground, the city plan took on an organic character, following the irregularities of elevation contours like the shapes that result from agricultural terracing.

After the gradual disintegration and fall of the West-Roman empire in the 5th century and the devastation by the invasions of Huns, Germanic peoples, Byzantines, Moors, Magyars, and Normans in the next five centuries, little remained of urban culture in western and central Europe.

In the 10th and 11th centuries, though, there appears to have been a general improvement in the political stability and economy. This made it possible for trade and craft to grow and for the monetary economy and urban culture to revive. Initially, urban culture recovered particularly in existing settlements, often in remnants of Roman towns and cities, but later on, ever more towns were created anew. Meanwhile, the population of western Europe increased rapidly and the utilised agricultural area grew with it. The agricultural areas of existing villages were extended and new villages and towns were created in uncultivated areas as cores for new reclamations.

Urban development in the early Middle Ages, characteristically focused on a fortress, a fortified abbey, or a (sometimes abandoned) Roman nucleus, occurred "like the annular rings of a tree", whether in an extended village or the centre of a larger city. Since the new centre was often on high, defensible ground, the city plan took on an organic character, following the irregularities of elevation contours like the shapes that result from agricultural terracing.

In the 9th to 14th centuries, many hundreds of new towns were built in Europe, and many others were enlarged with newly planned extensions. These new towns and town extensions have played a very important role in the shaping of Europe's geographical structures as they in modern times. New towns were founded in different parts of Europe from about the 9th century on, but most of them were realised from the 12th to 14th centuries, with a peak-period at the end of the 13th. All kinds of landlords, from the highest to the lowest rank, tried to found new towns on their estates, in order to gain economical, political or military power. The settlers of the new towns generally were attracted by fiscal, economic, and juridical advantages granted by the founding lord, or were forced to move from elsewhere from his estates. Most of the new towns were to remain rather small (as for instance the

In the 9th to 14th centuries, many hundreds of new towns were built in Europe, and many others were enlarged with newly planned extensions. These new towns and town extensions have played a very important role in the shaping of Europe's geographical structures as they in modern times. New towns were founded in different parts of Europe from about the 9th century on, but most of them were realised from the 12th to 14th centuries, with a peak-period at the end of the 13th. All kinds of landlords, from the highest to the lowest rank, tried to found new towns on their estates, in order to gain economical, political or military power. The settlers of the new towns generally were attracted by fiscal, economic, and juridical advantages granted by the founding lord, or were forced to move from elsewhere from his estates. Most of the new towns were to remain rather small (as for instance the

Only in ideal cities did a centrally planned structure stand at the heart, as in

Only in ideal cities did a centrally planned structure stand at the heart, as in

In contrast to the Great Fire of London, after the

In contrast to the Great Fire of London, after the

Modern

Modern

The first major urban planning theorist in Britain was Sir

The first major urban planning theorist in Britain was Sir

In the 1920s, the ideas of

In the 1920s, the ideas of

Various current movements in urban design seek to create sustainable urban environments with long-lasting structures, buildings and a great liveability for its inhabitants. The most clearly defined form of

Various current movements in urban design seek to create sustainable urban environments with long-lasting structures, buildings and a great liveability for its inhabitants. The most clearly defined form of  In sustainable construction, the recent movement of

In sustainable construction, the recent movement of

Some planners argue that modern lifestyles use too many natural resources, polluting or destroying

Some planners argue that modern lifestyles use too many natural resources, polluting or destroying

''Urban Planning, 1794-1918: An International Anthology of Articles, Conference Papers, and Reports''

Selected, Edited, and Provided with Headnotes by John W. Reps, Professor Emeritus, Cornell University. * ''City Planning According to Artistic Principles'',

''Missing Middle Housing: Responding to the Demand for Walkable Urban Living''

by Daniel Parolek of Opticos Design, Inc., 2012 * Kemp, Roger L. and Carl J. Stephani (2011). "Cities Going Green: A Handbook of Best Practices." McFarland and Co., Inc., Jefferson, NC, USA, and London, England, UK. (). * ''Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform'',

''What Do Planners Do?: Power, Politics, and Persuasion''

American Planning Association, 1994. * ''Planning the Twentieth-Century American City'', Christopher Silver and Mary Corbin Sies (Eds.),

''Urban Development: The Logic Of Making Plans''Lewis D. Hopkins

Island Press, 2001. * ''Readings in Planning Theory'', Susan Fainstein and Scott Campbell, Oxford, England and Malden, Massachusetts:

International Planning History Society

* {{Authority control

urban planning

Urban planning, also known as town planning, city planning, regional planning, or rural planning, is a technical and political process that is focused on the development and design of land use and the built environment, including air, water, ...

runs parallel to the history of the city, as planning is in evidence at some of the earliest known urban sites.

Pre-classical

The pre-Classical and Classical periods saw a number of cities laid out according to fixed plans, though many tended to develop organically. Designed cities were characteristic of the Minoan,Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

n, Harrapan, and Egyptian civilisations

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

Civ ...

of the third millennium BC (see Urban planning in ancient Egypt). The first recorded description of urban planning appears in the Epic of Gilgamesh

The ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' () is an epic poem from ancient Mesopotamia, and is regarded as the earliest surviving notable literature and the second oldest religious text, after the Pyramid Texts. The literary history of Gilgamesh begins with ...

: "Go up on to the wall of Uruk

Uruk, also known as Warka or Warkah, was an ancient city of Sumer (and later of Babylonia) situated east of the present bed of the Euphrates River on the dried-up ancient channel of the Euphrates east of modern Samawah, Muthanna Governorate, Al ...

and walk around. Inspect the foundation platform and scrutinise the brickwork. Testify that its bricks are baked bricks, And that the Seven Counsellors must have laid its foundations. One square mile

The mile, sometimes the international mile or statute mile to distinguish it from other miles, is a British imperial unit and United States customary unit of distance; both are based on the older English unit of length equal to 5,280 Engli ...

is city, one square mile is orchards, one square mile is claypits, as well as the open ground of Ishtar

Inanna, also sux, 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒀭𒈾, nin-an-na, label=none is an ancient Mesopotamian goddess of love, war, and fertility. She is also associated with beauty, sex, divine justice, and political power. She was originally worshiped in Su ...

's temple.Three square miles and the open ground comprise Uruk. Look for the copper tablet-box, Undo its bronze lock, Open the door to its secret, Lift out the lapis lazuli tablet and read."

Distinct characteristics of urban planning

Urban planning, also known as town planning, city planning, regional planning, or rural planning, is a technical and political process that is focused on the development and design of land use and the built environment, including air, water, ...

from remains of the cities of Harappa

Harappa (; Urdu/ pnb, ) is an archaeological site in Punjab, Pakistan, about west of Sahiwal. The Bronze Age Harappan civilisation, now more often called the Indus Valley Civilisation, is named after the site, which takes its name from a ...

, Lothal

Lothal () was one of the southernmost sites of the ancient Indus Valley civilisation, located in the Bhāl region of the modern state of Gujarāt. Construction of the city is believed to have begun around 2200 BCE.

Archaeological Survey of ...

, Dholavira

Dholavira ( gu, ધોળાવીરા) is an archaeological site at Khadirbet in Bhachau Taluka of Kutch District, in the state of Gujarat in western India, which has taken its name from a modern-day village south of it. This village is ...

, and Mohenjo-daro

Mohenjo-daro (; sd, موئن جو دڙو'', ''meaning 'Mound of the Dead Men';Indus Valley civilisation

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form 2600 BCE to 1900& ...

(in modern-day northwestern India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

and Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

) lead archeologists to interpret them as the earliest known examples of deliberately planned and managed cities.Davreu, Robert (1978). "Cities of Mystery: The Lost Empire of the Indus Valley". ''The World's Last Mysteries''. (second edition). Sydney: Reader's Digest. pp. 121-129. .Kipfer, Barbara Ann (2000). ''Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology''. (Illustrated edition). New York: Springer. p. 229. . The streets of many of these early cities were paved and laid out at right angles in a grid pattern

In urban planning, the grid plan, grid street plan, or gridiron plan is a type of city plan in which streets run at right angles to each other, forming a grid.

Two inherent characteristics of the grid plan, frequent intersections and orth ...

, with a hierarchy of streets from major boulevards to residential alleys. Archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

evidence suggests that many Harrapan houses were laid out to protect from noise and to enhance residential privacy; many also had their own water wells, probably both for sanitary and for ritual purposes. These ancient cities were unique in that they often had drainage systems, seemingly tied to a well-developed ideal of urban sanitation

Sanitation refers to public health conditions related to clean drinking water and treatment and disposal of human excreta and sewage. Preventing human contact with feces is part of sanitation, as is hand washing with soap. Sanitation syste ...

. Cities laid out on the grid plan

In urban planning, the grid plan, grid street plan, or gridiron plan is a type of city plan in which streets run at right angles to each other, forming a grid.

Two inherent characteristics of the grid plan, frequent intersections and orthogon ...

could have been an outgrowth of agriculture based on rectangular fields.

Most Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in southern North America and most of Central America. It extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. Wit ...

n cities in the late Postclassic period had highly organized central portions, typically consisting of one or more public plazas bordered by public buildings. In contrast, the surrounding residential areas typically showed little or no signs of planning.

China and Japan

China has a tradition of urban planning dating back thousands of years. InJapan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

, some cities, such as Nara

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) is an " independent federal agency of the United States government within the executive branch", charged with the preservation and documentation of government and historical records. It ...

and Heian-kyo, followed classic Chinese planning principles; later, during the feudal period, a type of town called Jōkamachi

The term refers to a type of urban structures in Japan in which the city surrounds a feudal lord's castle. These cities did not necessarily form around castles after the Edo period; some are known as Jin'yamachi, cities that have evolved around J ...

emerged. Those were castle town

A castle town is a settlement built adjacent to or surrounding a castle. Castle towns were common in Medieval Europe. Some examples include small towns like Alnwick and Arundel, which are still dominated by their castles. In Western Europe, a ...

s, planned for - and oriented around - defense. Roads were laid out to make the paths to castles longer; the castles and other buildings were often situated in order to hide the castles through densely packed surrounding buildings. Edo

Edo ( ja, , , "bay-entrance" or "estuary"), also romanized as Jedo, Yedo or Yeddo, is the former name of Tokyo.

Edo, formerly a ''jōkamachi'' (castle town) centered on Edo Castle located in Musashi Province, became the ''de facto'' capital of ...

, later Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.46 ...

, is one example of a castle town.

Greco-Roman empires

Hippodamus

Hippodamus of Miletus (; Greek: Ἱππόδαμος ὁ Μιλήσιος, ''Hippodamos ho Milesios''; 498 – 408 BC) was an ancient Greek architect, urban planner, physician, mathematician, meteorologist and philosopher, who is considered to b ...

(498–408 BC) is regarded as the first town planner and 'inventor' of the orthogonal urban layout. Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

called him "the father of city planning", and until well into the 20th century, he was indeed regarded as such. This is, however, only partly justified as Greek cities with orthogonal plans were built long before Hippodamus. The Hippodamian plan that was called after him is an orthogonal urban layout with more or less square street blocks. Archaeological finds from ancient Egypt—among others—demonstrate that Hippodamus cannot truly have been the inventor of this layout. Aristotle's critique and indeed ridicule of Hippodamus, which appears in ''Politics'' 2. 8, is perhaps the first known example of a criticism of urban planning.

From about the late 8th century on, Greek city-states started to found colonies along the coasts of the Mediterranean, which were centred on newly created towns and cities with more or less regular orthogonal plans. Gradually, the new layouts became more regular. After the city of Miletus

Miletus (; gr, Μῑ́λητος, Mī́lētos; Hittite transcription ''Millawanda'' or ''Milawata'' ( exonyms); la, Mīlētus; tr, Milet) was an ancient Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia, near the mouth of the Maeander River in ...

was destroyed by the Persians in 494 BC, it was rebuilt in a regular form that, according to tradition, was determined by the ideas of Hippodamus of Miletus. Regular orthogonal plans particularly appear to have been laid out for new colonial cities and cities that were rebuilt in a short period of time after destruction.

Following in the tradition of Hippodamus about a century later, Alexander commissioned the architect Dinocrates to lay out his new city of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

, the grandest example of idealised urban planning of the ancient Hellenistic world, where the city's regularity was facilitated by its level site near a mouth of the Nile.

The ancient Romans

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–50 ...

also employed regular orthogonal structures on which they molded their colonies. They probably were inspired by Greek and Hellenic examples, as well as by regularly planned cities that were built by the Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization () was developed by a people of Etruria in ancient Italy with a common language and culture who formed a federation of city-states. After conquering adjacent lands, its territory covered, at its greatest extent, roug ...

in Italy. (See Marzabotto.) The Roman engineer Vitruvius

Vitruvius (; c. 80–70 BC – after c. 15 BC) was a Roman architect and engineer during the 1st century BC, known for his multi-volume work entitled '' De architectura''. He originated the idea that all buildings should have three attribut ...

established principles of good design whose influence is still felt today.

The Romans used a consolidated scheme for city planning, developed for civil convenience. The basic plan consisted of a central forum with city services, surrounded by a compact, rectilinear grid of streets. A river sometimes flowed near or through the city, providing water, transport, and sewage disposal.

Hundreds of towns and cities were built by the Romans throughout their empire. Many European towns, such as Turin

Turin ( , Piedmontese language, Piedmontese: ; it, Torino ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in Northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital ...

, preserve the remains of these schemes, which show the very logical way the Romans designed their cities. They would lay out the streets at right angles, in the form of a square grid. All roads were equal in width and length, except for two, which were slightly wider than the others. The '' decumanus'', running east–west, and the '' cardo'', running north–south, intersected in the middle to form the centre of the grid. All roads were made of carefully fitted flag stones and filled in with smaller, hard-packed rocks and pebbles. Bridges were constructed where needed. Each square marked by four roads was called an '' insula'', the Roman equivalent of a modern city block

A city block, residential block, urban block, or simply block is a central element of urban planning and urban design.

A city block is the smallest group of buildings that is surrounded by streets, not counting any type of thoroughfare within t ...

.

Each insula was about square. As the city developed, it could eventually be filled with buildings of various shapes and sizes and criss-crossed with back roads and alleys.

The city may have been surrounded by a wall to protect it from invaders and to mark the city limits. Areas outside city limits were left open as farmland. At the end of each main road was a large gateway with watchtowers. A portcullis

A portcullis (from Old French ''porte coleice'', "sliding gate") is a heavy vertically-closing gate typically found in medieval fortifications, consisting of a latticed grille made of wood, metal, or a combination of the two, which slides down ...

covered the opening when the city was under siege, and additional watchtowers were constructed along the city walls. An aqueduct was built outside the city walls.

The development of Greek and Roman urbanisation is relatively well-known, as there are relatively many written sources, and there has been much attention to the subject since the Romans and Greeks are generally regarded as the main ancestors of modern Western culture. It should not be forgotten, though, that there were also other cultures with more or less urban settlements in Europe, primarily of Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

*Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Foo ...

origin. Among these, there are also cases that appear to have been newly planned, such as the Lusatian town of Biskupin

Biskupin is an archaeological site and a life-size model of a late Bronze Age fortified settlement in north-central Poland that also serves as an archaeological open-air museum. When first discovered it was thought to be early evidence of a W ...

in Poland.

Medieval Europe (500-1400)

After the gradual disintegration and fall of the West-Roman empire in the 5th century and the devastation by the invasions of Huns, Germanic peoples, Byzantines, Moors, Magyars, and Normans in the next five centuries, little remained of urban culture in western and central Europe.

In the 10th and 11th centuries, though, there appears to have been a general improvement in the political stability and economy. This made it possible for trade and craft to grow and for the monetary economy and urban culture to revive. Initially, urban culture recovered particularly in existing settlements, often in remnants of Roman towns and cities, but later on, ever more towns were created anew. Meanwhile, the population of western Europe increased rapidly and the utilised agricultural area grew with it. The agricultural areas of existing villages were extended and new villages and towns were created in uncultivated areas as cores for new reclamations.

Urban development in the early Middle Ages, characteristically focused on a fortress, a fortified abbey, or a (sometimes abandoned) Roman nucleus, occurred "like the annular rings of a tree", whether in an extended village or the centre of a larger city. Since the new centre was often on high, defensible ground, the city plan took on an organic character, following the irregularities of elevation contours like the shapes that result from agricultural terracing.

After the gradual disintegration and fall of the West-Roman empire in the 5th century and the devastation by the invasions of Huns, Germanic peoples, Byzantines, Moors, Magyars, and Normans in the next five centuries, little remained of urban culture in western and central Europe.

In the 10th and 11th centuries, though, there appears to have been a general improvement in the political stability and economy. This made it possible for trade and craft to grow and for the monetary economy and urban culture to revive. Initially, urban culture recovered particularly in existing settlements, often in remnants of Roman towns and cities, but later on, ever more towns were created anew. Meanwhile, the population of western Europe increased rapidly and the utilised agricultural area grew with it. The agricultural areas of existing villages were extended and new villages and towns were created in uncultivated areas as cores for new reclamations.

Urban development in the early Middle Ages, characteristically focused on a fortress, a fortified abbey, or a (sometimes abandoned) Roman nucleus, occurred "like the annular rings of a tree", whether in an extended village or the centre of a larger city. Since the new centre was often on high, defensible ground, the city plan took on an organic character, following the irregularities of elevation contours like the shapes that result from agricultural terracing.

In the 9th to 14th centuries, many hundreds of new towns were built in Europe, and many others were enlarged with newly planned extensions. These new towns and town extensions have played a very important role in the shaping of Europe's geographical structures as they in modern times. New towns were founded in different parts of Europe from about the 9th century on, but most of them were realised from the 12th to 14th centuries, with a peak-period at the end of the 13th. All kinds of landlords, from the highest to the lowest rank, tried to found new towns on their estates, in order to gain economical, political or military power. The settlers of the new towns generally were attracted by fiscal, economic, and juridical advantages granted by the founding lord, or were forced to move from elsewhere from his estates. Most of the new towns were to remain rather small (as for instance the

In the 9th to 14th centuries, many hundreds of new towns were built in Europe, and many others were enlarged with newly planned extensions. These new towns and town extensions have played a very important role in the shaping of Europe's geographical structures as they in modern times. New towns were founded in different parts of Europe from about the 9th century on, but most of them were realised from the 12th to 14th centuries, with a peak-period at the end of the 13th. All kinds of landlords, from the highest to the lowest rank, tried to found new towns on their estates, in order to gain economical, political or military power. The settlers of the new towns generally were attracted by fiscal, economic, and juridical advantages granted by the founding lord, or were forced to move from elsewhere from his estates. Most of the new towns were to remain rather small (as for instance the bastide

Bastides are fortified new towns built in medieval Languedoc, Gascony, Aquitaine, England and Wales during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, although some authorities count Mont-de-Marsan and Montauban, which was founded in 1144, as ...

s of southwestern France), but some of them became important cities, such as Cardiff

Cardiff (; cy, Caerdydd ) is the capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of Wales. It forms a Principal areas of Wales, principal area, officially known as the City and County of Cardiff ( cy, Dinas a ...

, Leeds

Leeds () is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the third-largest settlement (by popul ...

, 's-Hertogenbosch

s-Hertogenbosch (), colloquially known as Den Bosch (), is a city and municipality in the Netherlands with a population of 157,486. It is the capital of the province of North Brabant and its fourth largest by population. The city is south of ...

, Montauban

Montauban (, ; oc, Montalban ) is a commune in the Tarn-et-Garonne department, region of Occitania, Southern France. It is the capital of the department and lies north of Toulouse. Montauban is the most populated town in Tarn-et-Garonne, ...

, Bilbao

)

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize = 275 px

, map_caption = Interactive map outlining Bilbao

, pushpin_map = Spain Basque Country#Spain#Europe

, pushpin_map_caption ...

, Malmö

Malmö (, ; da, Malmø ) is the largest city in the Swedish county (län) of Scania (Skåne). It is the third-largest city in Sweden, after Stockholm and Gothenburg, and the sixth-largest city in the Nordic region, with a municipal popul ...

, Lübeck

Lübeck (; Low German also ), officially the Hanseatic City of Lübeck (german: Hansestadt Lübeck), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 217,000 inhabitants, Lübeck is the second-largest city on the German Baltic coast and in the state ...

, Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and ...

, Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

, Bern

german: Berner(in)french: Bernois(e) it, bernese

, neighboring_municipalities = Bremgarten bei Bern, Frauenkappelen, Ittigen, Kirchlindach, Köniz, Mühleberg, Muri bei Bern, Neuenegg, Ostermundigen, Wohlen bei Bern, Zollikofen

, website ...

, Klagenfurt

Klagenfurt am WörtherseeLandesgesetzblatt 2008 vom 16. Jänner 2008, Stück 1, Nr. 1: ''Gesetz vom 25. Oktober 2007, mit dem die Kärntner Landesverfassung und das Klagenfurter Stadtrecht 1998 geändert werden.'/ref> (; ; sl, Celovec), usually ...

, Alessandria

Alessandria (; pms, Lissandria ) is a city and ''comune'' in Piedmont, Italy, and the capital of the Province of Alessandria. The city is sited on the alluvial plain between the Tanaro and the Bormida rivers, about east of Turin.

Alessandri ...

, Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officiall ...

and Sarajevo

Sarajevo ( ; cyrl, Сарајево, ; ''see names in other languages'') is the capital and largest city of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with a population of 275,524 in its administrative limits. The Sarajevo metropolitan area including Sarajevo ...

.

From the evidence of the preserved towns, it appears that the formal structure of many of these towns was willfully planned. The newly founded towns often show a marked regularity in their plan form, in the sense that the streets are often straight and laid out at right angles to one another, and that the house lots are rectangular, and originally largely of the same size. One very clear and relatively extreme example is Elburg

Elburg () is a municipality and a city in the province of Gelderland, Netherlands.

History

There is evidence of a Neolithic settlement at Elburg consisting of stone tools and pottery shards. From Roman times there are names and shards of earthenw ...

in the Netherlands, dating from the end of the 14th century. (see illustration) Looking at town plans such as the one of Elburg, it clearly appears that it is impossible to maintain that the straight street and the symmetrical, orthogonal town plan were new inventions from 'the Renaissance,' and, therefore, typical of 'modern times.'

The deep depression around the middle of the 14th century marked the end of the period of great urban expansion. Only in the parts of Europe where the process of urbanisation had started relatively late, as in eastern Europe, was it still to go on for one or two more centuries. It would not be until the Industrial Revolution that the same level of expansion of urban population would be reached again, although the number of newly created settlements would remain much lower than in the 12th and 13th centuries.

Renaissance and Baroque Europe (1400-1750)

Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

was an early model of the new urban planning, which took on a star-shaped layout adapted from the new star fort, designed to resist cannon fire. This model was widely imitated, reflecting the enormous cultural power of Florence in this age; " e Renaissance was hypnotised by one city type which for a century and a half – from Filarete to Scamozzi – was impressed upon utopian schemes: this is the star-shaped city". Radial streets extend outward from a defined centre of military, communal or spiritual power.

Only in ideal cities did a centrally planned structure stand at the heart, as in

Only in ideal cities did a centrally planned structure stand at the heart, as in Raphael

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, better known as Raphael (; or ; March 28 or April 6, 1483April 6, 1520), was an Italian painter and architect of the High Renaissance. His work is admired for its clarity of form, ease of composition, and visual ...

's ''Sposalizio'' (''Illustration'') of 1504. As built, the unique example of a rationally planned ''quattrocento'' new city centre, that of Vigevano

Vigevano (; lmo, label=Western Lombard, Avgevan) is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Pavia, Lombardy in northern Italy. A historic art town, it is also renowned for shoemaking and is one of the main centres of Lomellina, a rice-growing a ...

(1493–95), resembles a closed space instead, surrounded by arcading.

Filarete

Antonio di Pietro Aver(u)lino (; – ), known as Filarete (; from grc, φιλάρετος, meaning "lover of excellence"), was a Florentine Renaissance architect, sculptor, medallist, and architectural theorist. He is perhaps best remembered for ...

's ideal city, building on Leon Battista Alberti

Leon Battista Alberti (; 14 February 1404 – 25 April 1472) was an Italian Renaissance humanist author, artist, architect, poet, priest, linguist, philosopher, and cryptographer; he epitomised the nature of those identified now as polymaths. H ...

's '' De re aedificatoria'', was named "Sforzinda

Sforzinda is a visionary ideal city named after Francesco Sforza, then Duke of Milan. It was designed by Renaissance architect Antonio di Pietro Averlino ( 1400 – 1469), also known as "Averulino" or " Filarete".

Layout

Although Sforzinda was n ...

" in compliment to his patron; its twelve-pointed shape, circumscribable by a "perfect" Pythagorean figure, the circle, took no heed of its undulating terrain in Filarete's manuscript. This process occurred in cities, but ordinarily not in the industrial suburbs characteristic of this era (see Braudel, ''The Structures of Everyday Life''), which remained disorderly and characterised by crowding and organic growth.

One of the most significant programmes of urban planning in the Baroque Period was Rome. Inspired by the ideal of the Renaissance city, Pope Sixtus V

Pope Sixtus V ( it, Sisto V; 13 December 1521 – 27 August 1590), born Felice Piergentile, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 24 April 1585 to his death in August 1590. As a youth, he joined the Franciscan order ...

's ambitious urban reform programme transformed the old environment to emulate the "long straight streets, wide regular spaces, uniformity and repetitiveness of structures, lavish use of commemorative and ornamental elements, and maximum visibility from both linear and circular perspective." The Pope set no limit to his plans, and achieved much in his short pontificate, always carried through at top speed: the completion of the dome of St. Peter's; the loggia

In architecture, a loggia ( , usually , ) is a covered exterior gallery or corridor, usually on an upper level, but sometimes on the ground level of a building. The outer wall is open to the elements, usually supported by a series of columns ...

of Sixtus in the Basilica di San Giovanni in Laterano

The Archbasilica Cathedral of the Most Holy Savior and of Saints John the Baptist and John the Evangelist in the Lateran ( it, Arcibasilica del Santissimo Salvatore e dei Santi Giovanni Battista ed Evangelista in Laterano), also known as the Papa ...

; the chapel of the Praesepe in Santa Maria Maggiore

The Basilica of Saint Mary Major ( it, Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, ; la, Basilica Sanctae Mariae Maioris), or church of Santa Maria Maggiore, is a Major papal basilica as well as one of the Seven Pilgrim Churches of Rome and the large ...

; additions or repairs to the Quirinal

The Quirinal Hill (; la, Collis Quirinalis; it, Quirinale ) is one of the Seven Hills of Rome, at the north-east of the city center. It is the location of the official residence of the Italian head of state, who resides in the Quirinal Pala ...

, Lateran

250px, Basilica and Palace - side view

Lateran and Laterano are the shared names of several buildings in Rome. The properties were once owned by the Lateranus family of the Roman Empire. The Laterani lost their properties to Emperor Constantin ...

and Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Vatican City, the city-state ruled by the pope in Rome, including St. Peter's Basilica, Sistine Chapel, Vatican Museum

The Holy See

* The Holy See, the governing body of the Catholic Church and sovereign entity recognized ...

palaces; the erection of four obelisk

An obelisk (; from grc, ὀβελίσκος ; diminutive of ''obelos'', " spit, nail, pointed pillar") is a tall, four-sided, narrow tapering monument which ends in a pyramid-like shape or pyramidion at the top. Originally constructed by An ...

s, including that in Saint Peter's Square

Saint Peter's Square ( la, Forum Sancti Petri, it, Piazza San Pietro ,) is a large plaza located directly in front of St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican City, the papal enclave inside Rome, directly west of the neighborhood ( rione) of Borgo. ...

; the opening of six streets; the restoration of the aqueduct of Septimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus (; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) in the Roman province of Africa. As a young man he advanced through the customary suc ...

(" Acqua Felice"); the integration of the Leonine City

The Leonine City ( Latin: ''Civitas Leonina'') is the part of the city of Rome which, during the Middle Ages, was enclosed with the Leonine Wall, built by order of Pope Leo IV in the 9th century.

This area was located on the opposite side of th ...

in Rome as XIV Rione

A (; plural: ) is a neighbourhood in several Italian cities. A is a territorial subdivision. The larger administrative subdivisions in Rome are the , with the being used only in the historic centre. The word derives from the Latin , the 14 su ...

( Borgo).

During this period, rulers often embarked on ambitious attempts at redesigning their capital cities as a showpiece for the grandeur of the nation. Disasters were often a major catalyst for planned reconstruction. An exception to this was in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

after the Great Fire of 1666

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through central London from Sunday 2 September to Thursday 6 September 1666, gutting the medieval City of London inside the old Roman city wall, while also extending past th ...

when, despite many radical rebuilding schemes from architects such as John Evelyn

John Evelyn (31 October 162027 February 1706) was an English writer, landowner, gardener, courtier and minor government official, who is now best known as a diarist. He was a founding Fellow of the Royal Society.

John Evelyn's diary, or m ...

and Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren PRS FRS (; – ) was one of the most highly acclaimed English architects in history, as well as an anatomist, astronomer, geometer, and mathematician-physicist. He was accorded responsibility for rebuilding 52 church ...

, no large-scale redesigning was achieved due to the complexities of rival ownership claims. However, improvements were made in hygiene and fire safety with wider streets, stone construction and access to the river

A river is a natural flowing watercourse, usually freshwater, flowing towards an ocean, sea, lake or another river. In some cases, a river flows into the ground and becomes dry at the end of its course without reaching another body of ...

. The Great Fire did, however, stimulate thinking about urban design that influenced city planning in North America. The Grand Model for the Province of Carolina

The Grand Model (or "Grand Modell" as it was spelled at the time) was a utopian plan for the Province of Carolina, founded in . It consisted of a constitution coupled with a settlement and development plan for the colony. The former was titled the ...

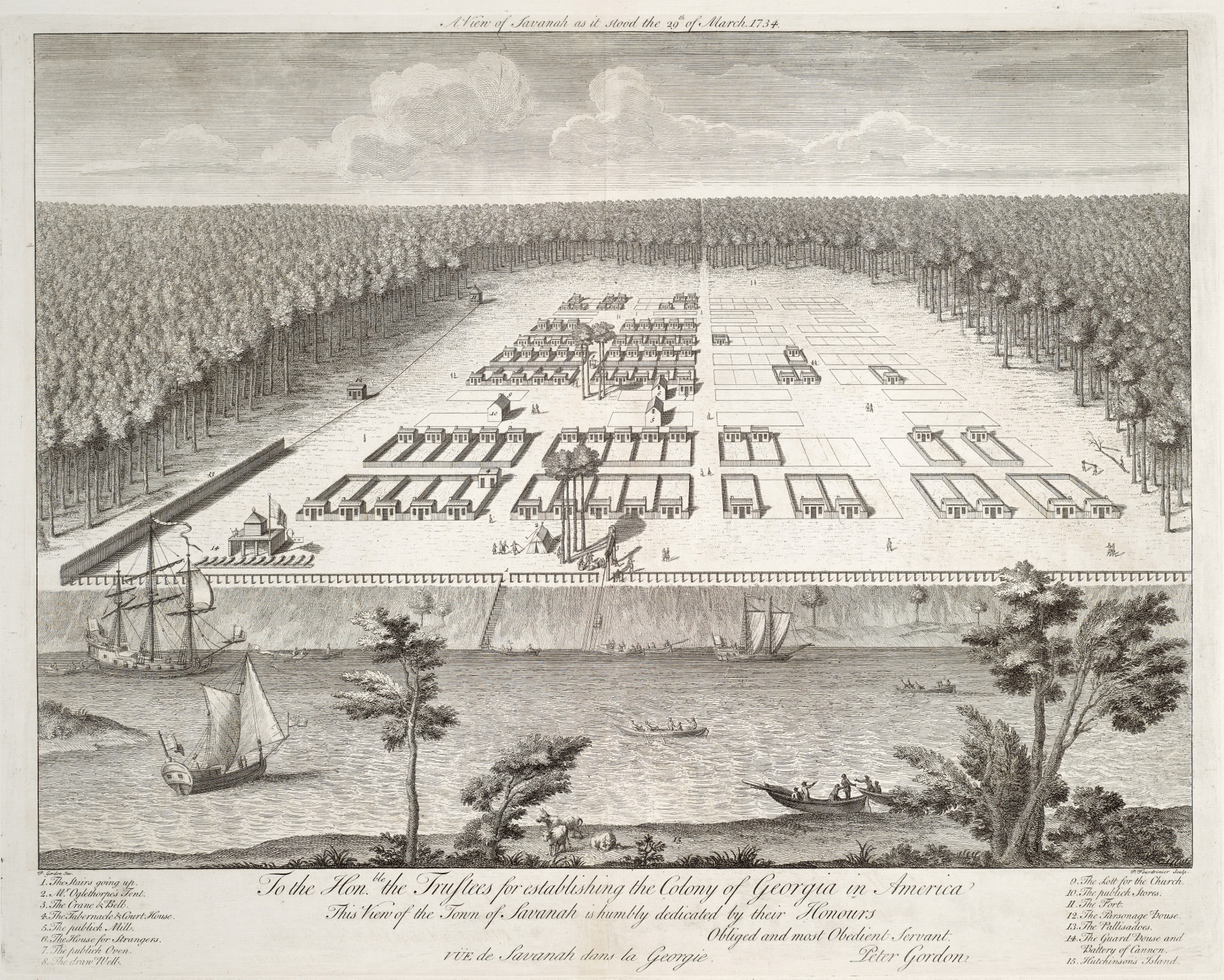

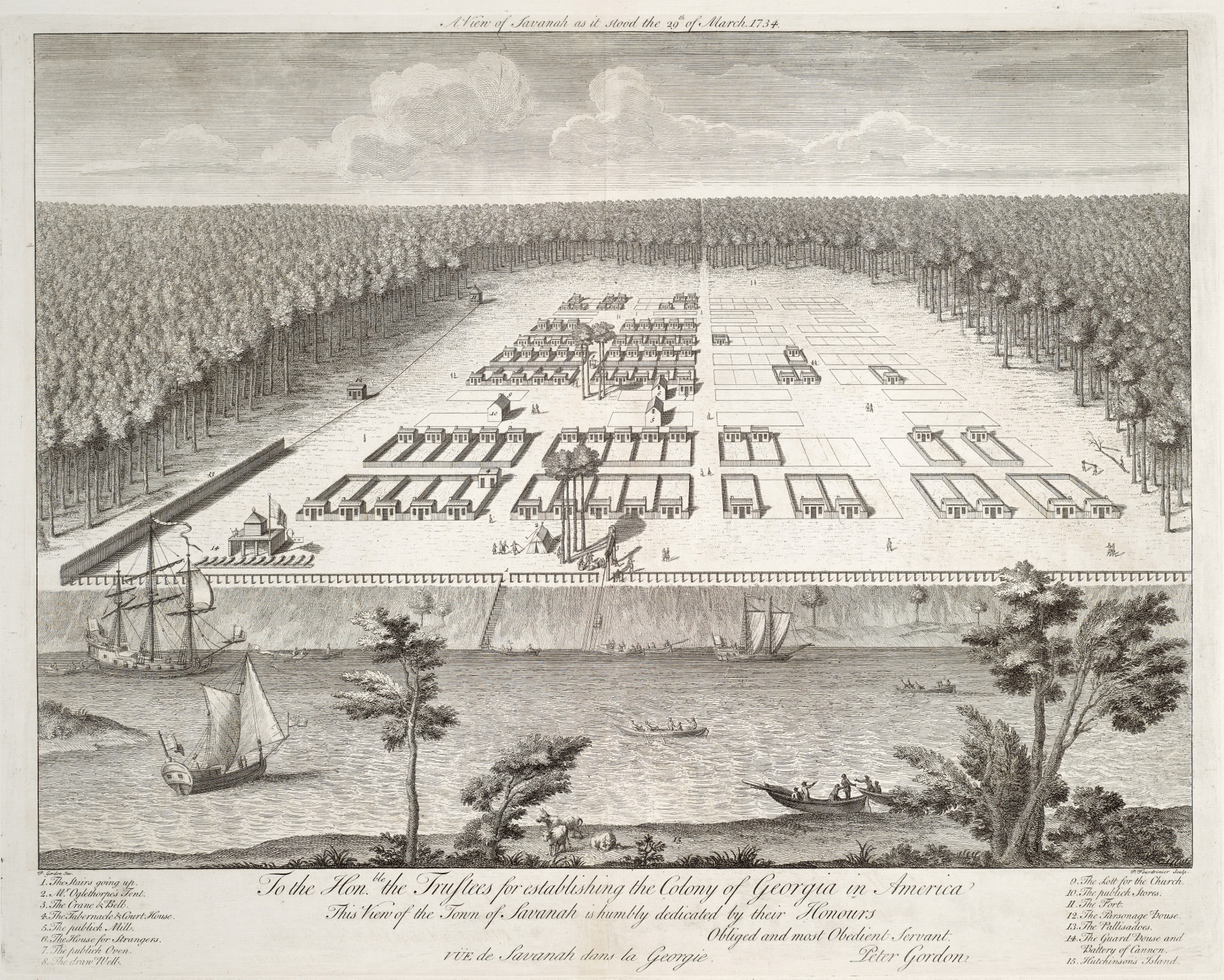

, developed in the aftermath of the Great Fire, established a template for colonial planning. The famous Oglethorpe Plan

The Oglethorpe Plan is an urban planning idea that was most notably used in Savannah, Georgia, one of the Thirteen Colonies, in the 18th century. The plan uses a distinctive street network with repeating squares of residential blocks, commercial ...

for Savannah (1733) was in part influenced by the Grand Model.

Following the 1695 bombardment of Brussels by the French troops of King Louis XIV

Louis XIV (Louis Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was List of French monarchs, King of France from 14 May 1643 until his death in 1715. His reign of 72 years and 110 days is the Li ...

, in which a large part of the city centre was destroyed, Governor Max Emanuel

Max or MAX may refer to:

Animals

* Max (dog) (1983–2013), at one time purported to be the world's oldest living dog

* Max (English Springer Spaniel), the first pet dog to win the PDSA Order of Merit (animal equivalent of OBE)

* Max (gorilla) ...

proposed using the reconstruction to completely change the layout and architectural style of the city. His plan was to transform the medieval city into a city of the new Baroque

The Baroque (, ; ) is a style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished in Europe from the early 17th century until the 1750s. In the territories of the Spanish and Portuguese empires including ...

style, modelled on Turin

Turin ( , Piedmontese language, Piedmontese: ; it, Torino ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in Northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital ...

, which from 1600 was transformed by Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy

Charles Emmanuel I ( it, Carlo Emanuele di Savoia; 12 January 1562 – 26 July 1630), known as the Great, was the Duke of Savoy from 1580 to 1630. He was nicknamed (, in context "the Hot-Headed") for his rashness and military aggression.

Being ...

into one of the earliest Baroque cities. With a logical street layout, straight avenues offered long, uninterrupted views flanked by buildings of a uniform size. This plan was opposed by residents and municipal authorities, who wanted a rapid reconstruction, did not have the resources for grandiose proposals, and resented what they considered the imposition of a new, foreign, architectural style. In the actual reconstruction, the general layout of the city was conserved, but it was not identical to that before the cataclysm. Despite the necessity of rapid reconstruction and the lack of financial means, authorities did take several measures to improve traffic flow, sanitation, and the aesthetics of the city. Many streets were made as wide as possible to improve traffic flow.

Enlightenment Europe and America (1700-1800)

1755 Lisbon earthquake

The 1755 Lisbon earthquake, also known as the Great Lisbon earthquake, impacted Portugal, the Iberian Peninsula, and Northwest Africa on the morning of Saturday, 1 November, Feast of All Saints, at around 09:40 local time. In combination with ...

, King Joseph I of Portugal

Dom Joseph I ( pt, José Francisco António Inácio Norberto Agostinho, ; 6 June 1714 – 24 February 1777), known as the Reformer (Portuguese: ''o Reformador''), was King of Portugal from 31 July 1750 until his death in 1777. Among other act ...

and his ministers immediately launched efforts to rebuild the city. The architect Manuel da Maia

Manuel da Maia (5 August 1677, baptised – 17 September 1768) was a Portuguese architect, engineer, and archivist. Maia is primarily remembered for his leadership in the reconstruction efforts following the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, alongside Eug ...

boldly proposed razing entire sections of the city and "laying out new streets without restraint". This last option was chosen by the king and his minister in spite of its emphasis on commerce and industry as opposed to religious and royal structures. Keen to have a new and perfectly ordered city, the king commissioned the construction of big squares, rectilinear, large avenues and widened streets – the new ''mottos'' of Lisbon. The Pombaline buildings were among the earliest seismically protected constructions in Europe.

Another significant urban plan from the Enlightenment period was that of Edinburgh's New Town

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator ...

, built in stages between 1767 and 1850. The Age of Enlightenment had arrived in Edinburgh, and the outdated city fabric did not suit the professional and merchant classes who lived there. A design competition was held in January 1766 to find a suitably modern layout for the new suburb. It was won by 26-year-old James Craig, who proposed a simple axial grid, with a principal thoroughfare along the ridge linking two garden squares. The New Town was envisaged as a mainly residential suburb with a number of professional offices of domestic layout. It had few planned retail ground floors, however it did not take long for the commercial potential of the site to be realised.

Modern urban planning (1800-onwards)

From 1800 onwards, urban planning developed as a technical and legal occupation and in its complexity.Regent Street

Regent Street is a major shopping street in the West End of London. It is named after George, the Prince Regent (later George IV) and was laid out under the direction of the architect John Nash and James Burton. It runs from Waterloo Plac ...

was one of the first planned developments of London. An ordered structure of London streets, replacing the mediaeval layout, had been planned since just after the Great Fire of London (1666) when Sir Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren PRS FRS (; – ) was one of the most highly acclaimed English architects in history, as well as an anatomist, astronomer, geometer, and mathematician-physicist. He was accorded responsibility for rebuilding 52 churche ...

and John Evelyn drew plans for rebuilding the city on the classical formal model. The street was designed by John Nash (who had been appointed to the Office of Woods and Forests in 1806 and previously served as an adviser to the Prince Regent) and by developer James Burton. The design was adopted by an Act of Parliament in 1813, which permitted the commissioners to borrow £600,000 for building and construction. The street was intended for commercial purposes and it was expected that most of the income would come from private capital. Nash took responsibility for design and valuation of all properties Construction of the road required demolishing numerous properties, disrupting trade and polluting the air with dust. Existing tenants had first offer to purchase leases on the new properties.

An even more ambitious reconstruction was carried out in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

. In 1852, Georges-Eugène Haussmann

Georges-Eugène Haussmann, commonly known as Baron Haussmann (; 27 March 180911 January 1891), was a French official who served as prefect of Seine (1853–1870), chosen by Emperor Napoleon III to carry out a massive urban renewal programme of n ...

was commissioned to remodel the Medieval street plan of the city by demolishing swathes of the old quarters and laying out wide boulevards, extending outwards beyond the old city limits. Haussmann's project encompassed all aspects of urban planning, both in the centre of Paris and in the surrounding districts, with regulations imposed on building façades, public parks, sewers and water works, city facilities, and public monuments. Beyond aesthetic and sanitary considerations, the wide thoroughfares facilitated troop movement and policing.

A concurrent plan to extend Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

was based on a scientific analysis of the city and its modern requirements. It was drawn up by the Catalan engineer Ildefons Cerdà

Ildefons Cerdà i Sunyer (; es, Ildefonso Cerdá Suñer; December 23, 1815, Centelles – August 21, 1876, Caldas de Besaya) was a Spanish urban planner and engineer who designed the 19th-century "extension" of Barcelona called the ''Eixampl ...

to fill the space beyond the city walls after they were demolished from 1854. He is credited with inventing the term 'urbanisation

Urbanization (or urbanisation) refers to the population shift from rural to urban areas, the corresponding decrease in the proportion of people living in rural areas, and the ways in which societies adapt to this change. It is predominantly the ...

' and his approach was codified in his ''Teoría General de la Urbanización'' (''General Theory of Urbanisation'', 1867). Cerdà's Eixample

The Eixample (; ) is a district of Barcelona between the old city ( Ciutat Vella) and what were once surrounding small towns ( Sants, Gràcia, Sant Andreu, etc.), constructed in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Its population was 262,000 ...

(Catalan for 'extension') consisted of 550 regular blocks with chamfered corners to facilitate the movement of trams, crossed by three wider avenues. His objectives were to improve the health of the inhabitants, towards which the blocks were built around central gardens and orientated NW-SE to maximise the sunlight they received, and assist social integration.

Proposals were also developed at the same time from 1857 for Vienna's Ringstrasse

The Vienna Ring Road (german: Ringstraße, lit. ''ring road'') is a 5.3 km (3.3 mi) circular grand boulevard that serves as a ring road around the historic Innere Stadt (Inner Town) district of Vienna, Austria. The road is located on sites wher ...

. This grand boulevard was built to replace the city walls. In 1857, Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria issued the decree ordering the demolition of the city walls and moats. During the following years, a large number of opulent public and private buildings were erected. Similarly, Berlin finalized its "Bebauungsplan der Umgebungen Berlins" ( Binding Land-Use Plan for the Environs of Berlin) in 1862, intended for a time frame of about 50 years. The plan not only covered the area around the cities of Berlin and Charlottenburg but also described the spatial regional planning of a large perimeter. The plan resulted in large areas of dense urban city blocks known as 'blockrand structures', with mixed-use buildings reaching to the street and offering a common-used courtyard, later often overbuilt with additional court structures to house more people.

Planning and architecture continued its paradigm shift at the turn of the 20th century. The industrialised cities of the 19th century had grown at a tremendous rate, with the pace and style of building often dictated by private business concerns. The evils of urban life for the working poor were becoming increasingly evident as a matter for public concern. The laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups ...

style of government management of the economy, in fashion for most of the Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwa ...

, was starting to give way to a New Liberalism that championed intervention on the part of the poor and disadvantaged beyond urban planning as a primarily aesthetic and technical concern as in the major urban planning programmes in European cities. Around 1900, theorists began developing urban planning models to mitigate the consequences of the industrial age, by providing citizens, especially factory workers, with healthier environments.

Modern

Modern zoning

Zoning is a method of urban planning in which a municipality or other tier of government divides land into areas called zones, each of which has a set of regulations for new development that differs from other zones. Zones may be defined for a si ...

legislation and other tools such as compulsory purchase and land readjustment, which enabled planners to legally demarcate sections of cities for different functions or determine the shape and depth of urban blocks, originated in Prussia, and spread to Britain, the US, and Scandinavia. Public health

Public health is "the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private, communities and individuals". Analyzing the det ...

was cited as a rationale for keeping cities organized.

Urban planning profession and legislation

Urban planning became professionalised at this period, with input fromutopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book '' Utopia'', describing a fictional island soc ...

n visionaries as well as from the practical minded infrastructure engineers and local councillors combining to produce new design templates for political consideration. Reinhard Baumeister was a German engineer and urban planner, the author of one of the earliest texts on urban planning Stadterweiterungen in technischer, baupolizeilicher und Wirtschaftlicher Beziehung (Town extensions: their links with technical and economic concerns and with building regulations) published in 1876. It was used as a textbook at the first urban planning course in Germany, at the college of technology in Aachen in 1880.

Similarly influential was Josef Stübben's 1890 publication ''Der Stadtebau'', published in 1890 and again in 1907 and 1924. Stübben served as the chief city planner of Cologne between 1881 and 1898 and was influential in his advocacy for the social objectives of city planning particularly for the urban poor.

The publication was never translated into English, but Stübben presented papers at numerous city planning conferences, including at the 1910 conference on city planning sponsored by the Royal Institute of British Architects, alongside Daniel Burnham, Ebenezer Howard, Patrick Geddes and Raymond Unwin. That same year the U.S. Senate published guidance on city planning that contained examples of German planning legislation directly influenced by Stübben. Whilst some theorists have recognised that American planning was primarily influenced by German and British practices, the German influence has not been as widely studied as a result of geopolitical tensions in and around the World Wars.

Legislation enabling the laying out of urban plans by municipalities and compulsory purchase powers were set out in the German Federal Building Line Act of 1875, but the 1794 Allgemeines Landrecht already gave the local state authority, namely the police, the right to indicate Fluchtlinien, i.e. the boundaries of areas which were to be reserved for streets. After the Prussian municipal reform of 1808 the Baupolizei became accountable to the municipal administration (with the important exception of Berlin), which thus also became responsible for the planning function.

Such tools were already widely used in France which from 1807 required settlements of over 2,000 inhabitants to prepare a compulsory easement plan setting out building lines and the width of the streets between them. In 1889, the architect and urban theorist Camillo Sitte

Camillo Sitte (17 April 1843 – 16 November 1903) was an Austrian architect, painter and urban theorist whose work influenced urban planning and land use regulation. Today, Sitte is best remembered for his 1889 book, ''City Planning According to ...

published ''City Planning According to Artistic Principles'', in which he examined and documented the traditional, incremental approach to urbanism in Europe, with a close focus on public spaces in Italy and the Germanic countries. Sitte's work was hugely influential on European urbanism, and with five editions published between 1889 and 1922 was cited by planners from Raymond Unwin

Sir Raymond Unwin (2 November 1863 – 29 June 1940) was a prominent and influential English engineer, architect and town planner, with an emphasis on improvements in working class housing.

Early years

Raymond Unwin was born in Rotherham, York ...

to Berlage.

In Britain, the Town and Country Planning Association was founded in 1899 and the first academic course on urban planning in Britain was offered by the University of Liverpool

, mottoeng = These days of peace foster learning

, established = 1881 – University College Liverpool1884 – affiliated to the federal Victoria Universityhttp://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukla/2004/4 University of Manchester Act 200 ...

in 1909. The first official consideration of these new trends in Britain was embodied in the Housing and Town Planning Act of 1909 that compelled local authorities

Local government is a generic term for the lowest tiers of public administration within a particular sovereign state. This particular usage of the word government refers specifically to a level of administration that is both geographically-loca ...

to introduce coherent systems of town planning across the country using the new principles of the 'garden city', and to ensure that all housing construction conformed to specific building standards, while similar yet more comprehensive legislation was enacted in the Netherlands under the Housing Act 1901, known as the '. Following Britain's 1909 Act, surveyor

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. A land surveying professional is ...

s, civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering – the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructure while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing ...

s, architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that h ...

s, lawyer

A lawyer is a person who practices law. The role of a lawyer varies greatly across different legal jurisdictions. A lawyer can be classified as an advocate, attorney, barrister, canon lawyer, civil law notary, counsel, counselor, solicit ...

s and others began working together within local government

Local government is a generic term for the lowest tiers of public administration within a particular sovereign state. This particular usage of the word government refers specifically to a level of administration that is both geographically-loc ...

in the UK to draw up schemes for the development of land and the idea of town planning as a new and distinctive area of expertise began to be formed. In 1910, Thomas Adams was appointed as the first Town Planning Inspector at the Local Government Board

The Local Government Board (LGB) was a British Government supervisory body overseeing local administration in England and Wales from 1871 to 1919.

The LGB was created by the Local Government Board Act 1871 (C. 70) and took over the public health a ...

, and began meeting with practitioners. The Town Planning Institute was established in 1914 with a mandate to advance the study of town-planning and civic design. The first university course in America was established at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

in 1924.

Garden city movement

The first major urban planning theorist in Britain was Sir

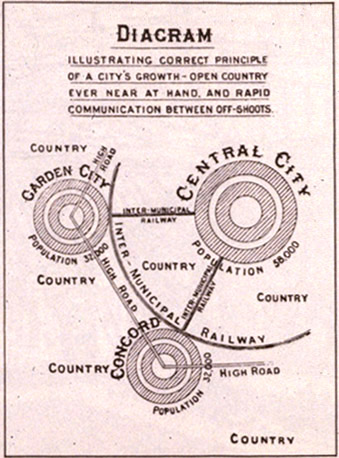

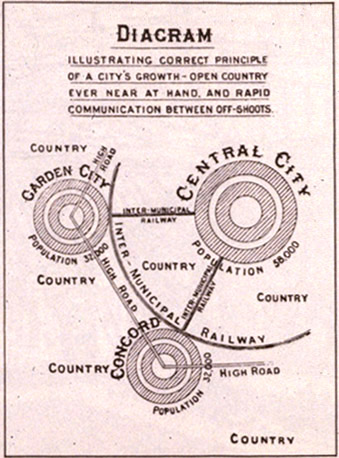

The first major urban planning theorist in Britain was Sir Ebenezer Howard

Sir Ebenezer Howard (29 January 1850 – 1 May 1928) was an English urban planner and founder of the garden city movement, known for his publication ''To-Morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform'' (1898), the description of a utopian city in whic ...

, who initiated the garden city movement

The garden city movement was a 20th century urban planning movement promoting satellite communities surrounding the central city and separated with greenbelts. These Garden Cities would contain proportionate areas of residences, industry, and ...

in 1898. This was inspired by earlier planned communities built by industrial philanthropists in the countryside, such as Cadbury

Cadbury, formerly Cadbury's and Cadbury Schweppes, is a British multinational confectionery company fully owned by Mondelez International (originally Kraft Foods) since 2010. It is the second largest confectionery brand in the world after Mar ...

s' Bournville

Bournville () is a model village on the southwest side of Birmingham, England, founded by the Quaker Cadbury family for employees at its Cadbury's factory, and designed to be a "garden" (or "model") village where the sale of alcohol was forb ...

, Lever's Port Sunlight

Port Sunlight is a model village and suburb in the Metropolitan Borough of Wirral, Merseyside. It is located between Lower Bebington and New Ferry, on the Wirral Peninsula. Port Sunlight was built by Lever Brothers to accommodate workers in it ...

and George Pullman

George Mortimer Pullman (March 3, 1831 – October 19, 1897) was an American engineer and industrialist. He designed and manufactured the Pullman sleeping car and founded a company town, Pullman, for the workers who manufactured it. This ulti ...

's eponymous Pullman in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

. All these settlements decentralised the working environment from the centre of the cities, and provided a healthy living space for the factory workers. Howard generalised this achievement into a planned movement for the country as a whole. He was also influenced by the work of economist Alfred Marshall

Alfred Marshall (26 July 1842 – 13 July 1924) was an English economist, and was one of the most influential economists of his time. His book '' Principles of Economics'' (1890) was the dominant economic textbook in England for many years. I ...

who argued in 1884 that industry needed a supply of labour that could in theory be supplied anywhere, and that companies have an incentive to improve workers living standards as the company bears much of the cost inflicted by the unhealthy urban conditions in the big cities.

Howard's ideas, although utopian, were also highly practical and were adopted around the world in the ensuing decades. His garden cities were intended to be planned, self-contained communities surrounded by parks, containing proportionate and separate areas of residences, industry, and agriculture. Inspired by the Utopian

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia'', describing a fictional island socie ...

novel ''Looking Backward

''Looking Backward: 2000–1887'' is a utopian science fiction novel by Edward Bellamy, a journalist and writer from Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts; it was first published in 1888.

The book was translated into several languages, and in short o ...

'' and Henry George

Henry George (September 2, 1839 – October 29, 1897) was an American political economist and journalist. His writing was immensely popular in 19th-century America and sparked several reform movements of the Progressive Era. He inspired the eco ...

's work Progress and Poverty

''Progress and Poverty: An Inquiry into the Cause of Industrial Depressions and of Increase of Want with Increase of Wealth: The Remedy'' is an 1879 book by social theorist and economist Henry George. It is a treatise on the questions of why pover ...

, Howard published his book ''Garden Cities of To-morrow

''Garden Cities of To-morrow'' is a book by the British urban planner Ebenezer Howard. When it was published in 1898, the book was titled ''To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform''. In 1902 it was reprinted as ''Garden Cities of To-Morrow''. ...

'' in 1898, commonly regarded as the most important book in the history of urban planning. His idealised garden city would house 32,000 people on a site of , planned on a concentric

In geometry, two or more objects are said to be concentric, coaxal, or coaxial when they share the same center or axis. Circles, regular polygons and regular polyhedra, and spheres may be concentric to one another (sharing the same center p ...

pattern with open spaces, public parks and six radial boulevard

A boulevard is a type of broad avenue planted with rows of trees, or in parts of North America, any urban highway.

Boulevards were originally circumferential roads following the line of former city walls.

In American usage, boulevards may ...

s, wide, extending from the centre. The garden city would be self-sufficient and when it reached full population, another garden city would be developed nearby. Howard envisaged a cluster of several garden cities as satellites

A satellite or artificial satellite is an object intentionally placed into orbit in outer space. Except for passive satellites, most satellites have an electricity generation system for equipment on board, such as solar panels or radioisotop ...

of a central city of 50,000 people, linked by road and rail.

He founded First Garden City, Ltd. in 1899 to create the first garden city at Letchworth, Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For gov ...

. Donors to the project collected interest on their investment if the garden city generated profits through rents or, as Fishman calls the process, 'philanthropic land speculation'. Howard tried to include working class cooperative organisations, which included over two million members, but could not win their financial support. In 1904, Raymond Unwin

Sir Raymond Unwin (2 November 1863 – 29 June 1940) was a prominent and influential English engineer, architect and town planner, with an emphasis on improvements in working class housing.

Early years

Raymond Unwin was born in Rotherham, York ...

, a noted architect and town planner, along with his partner Richard Barry Parker

Richard Barry Parker (18 November 1867 – 21 February 1947) was an English architect and urban planner associated with the Arts and Crafts Movement. He was primarily known for his architectural partnership with Raymond Unwin.

Biography

...

, won the competition run by the First Garden City, Limited to plan Letchworth, an area 34 miles outside London. Unwin and Parker planned the town in the centre of the Letchworth estate with Howard's large agricultural greenbelt surrounding the town, and they shared Howard's notion that the working class deserved better and more affordable housing. However, the architects ignored Howard's symmetric design, instead replacing it with a more 'organic' design.

Welwyn Garden City

Welwyn Garden City ( ) is a town in Hertfordshire, England, north of London. It was the second garden city in England (founded 1920) and one of the first new towns (designated 1948). It is unique in being both a garden city and a new town and ...

, also in Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For gov ...

was also built on Howard's principles. His successor as chairman of the Garden City Association was Sir Frederic Osborn, who extended the movement to regional planning.

The principles of the garden city were soon applied to the planning of city suburbs. The first such project was the Hampstead Garden Suburb

Hampstead Garden Suburb is an elevated suburb of London, north of Hampstead, west of Highgate and east of Golders Green. It is known for its intellectual, liberal, artistic, musical and literary associations. It is an example of early twentie ...

founded by Henrietta Barnett

Dame Henrietta Octavia Weston Barnett, DBE (''née'' Rowland; 4 May 1851 – 10 June 1936) was an English social reformer, educationist, and author. She and her husband, Samuel Augustus Barnett, founded the first "University Settlement" at To ...

and planned by Parker and Unwin. The scheme's utopian ideals were that it should be open to all classes of people with free access to woods and gardens and that the housing should be of low density with wide, tree-lined roads.

In North America, the Garden City movement was also popular, and evolved into the "Neighbourhood Unit" form of development. In the early 1900s, as cars were introduced to city streets for the first time, residents became increasingly concerned with the number of pedestrians being injured by car traffic. The response, seen first in Radburn, New Jersey

Radburn is an unincorporated community located within Fair Lawn in Bergen County, New Jersey, United States.

Radburn was founded in 1929 as "a town for the motor age".

, was the Neighbourhood Unit-style development, which oriented houses toward a common public path instead of the street. The neighbourhood is distinctively organised around a school, with the intention of providing children a safe way to walk to school.

The Tudor Walters Committee that recommended the building of housing estates after World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

incorporated the ideas of Howard's disciple Raymond Unwin

Sir Raymond Unwin (2 November 1863 – 29 June 1940) was a prominent and influential English engineer, architect and town planner, with an emphasis on improvements in working class housing.

Early years

Raymond Unwin was born in Rotherham, York ...

, who demonstrated that homes could be built rapidly and economically whilst maintaining satisfactory standards for gardens, family privacy and internal spaces. Unwin diverged from Howard by proposing that the new developments should be peripheral 'satellites' rather than fully-fledged garden cities.

Modernism

In the 1920s, the ideas of

In the 1920s, the ideas of modernism

Modernism is both a philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new forms of art, philosophy, an ...

began to surface in urban planning. The influential modernist

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

architect Le Corbusier

Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (6 October 188727 August 1965), known as Le Corbusier ( , , ), was a Swiss-French architect, designer, painter, urban planner, writer, and one of the pioneers of what is now regarded as modern architecture. He was ...

presented his scheme for a "Contemporary City" for three million inhabitants (Ville Contemporaine The Ville contemporaine (, ''Contemporary City'') was an unrealized utopian planned community intended to house three million inhabitants designed by the French-Swiss architect Le Corbusier in 1922.

Plan

The centerpiece of this plan was a group of ...

) in 1922. The centrepiece of this plan was the group of sixty-story cruciform

Cruciform is a term for physical manifestations resembling a common cross or Christian cross. The label can be extended to architectural shapes, biology, art, and design.

Cruciform architectural plan

Christian churches are commonly describe ...

skyscrapers, steel-framed office buildings encased in huge curtain walls of glass. These skyscrapers were set within large, rectangular, park-like green spaces. At the centre was a huge transportation hub that on different levels included depots for buses and trains, as well as highway intersections, and at the top, an airport. Le Corbusier had the fanciful notion that commercial airliners would land between the huge skyscrapers. He segregated pedestrian circulation paths from the roadways and glorified the automobile as a means of transportation. As one moved out from the central skyscrapers, smaller low-story, zig-zag apartment blocks (set far back from the street amid green space) housed the inhabitants. Le Corbusier hoped that politically minded industrialists in France would lead the way with their efficient Taylorist and Fordist strategies adopted from American industrial models to re-organise society.

In 1925, he exhibited his Plan Voisin

Plan Voisin was a planned redevelopment of Paris designed by French Swiss architect Le Corbusier in 1925. The redevelopment was planned to replace a large area of central Paris, on the Right Bank of the River Seine. Although it was never implemen ...