History of underwater diving on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of

The history of

Underwater diving was practiced in

Underwater diving was practiced in

The diving bell is one of the earliest types of equipment for underwater work and exploration. Its use was first described by

The diving bell is one of the earliest types of equipment for underwater work and exploration. Its use was first described by  In 1658, Albrecht von Treileben was contracted by King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden to salvage the warship , which sank outside Stockholm harbor in about of water on its maiden voyage in 1628. Between 1663 and 1665 von Treileben's divers were successful in raising most of the cannon, working from a diving bell with an estimated free air capacity of about for periods of about 15 minutes at a time in dark water with a temperature of about . In late 1686, Sir William Phipps convinced investors to fund an expedition to what is now Haiti and the

In 1658, Albrecht von Treileben was contracted by King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden to salvage the warship , which sank outside Stockholm harbor in about of water on its maiden voyage in 1628. Between 1663 and 1665 von Treileben's divers were successful in raising most of the cannon, working from a diving bell with an estimated free air capacity of about for periods of about 15 minutes at a time in dark water with a temperature of about . In late 1686, Sir William Phipps convinced investors to fund an expedition to what is now Haiti and the

In 1602, the Spanish military engineer Jerónimo de Ayanz y Beaumont developed the first documented diving dress. It was tested the same year in the

In 1602, the Spanish military engineer Jerónimo de Ayanz y Beaumont developed the first documented diving dress. It was tested the same year in the

In 1405,

In 1405,  In 1829, the Deane brothers sailed from

In 1829, the Deane brothers sailed from

''Royal George'', a 100-gun

''Royal George'', a 100-gun

An important step in the development of open-circuit scuba technology was the invention of the demand regulator in 1864 by the French engineers Auguste Denayrouze and Benoît Rouquayrol. Their suit was the first to supply air to the user by adjusting the flow according to the diver's requirements. The system still had to use surface supply, as the storage cylinders of the 1860s were not able to withstand the high pressures necessary for a practical self-contained unit.

The first open-circuit scuba system was devised in 1925 by Yves Le Prieur in France. Inspired by the simple apparatus of

An important step in the development of open-circuit scuba technology was the invention of the demand regulator in 1864 by the French engineers Auguste Denayrouze and Benoît Rouquayrol. Their suit was the first to supply air to the user by adjusting the flow according to the diver's requirements. The system still had to use surface supply, as the storage cylinders of the 1860s were not able to withstand the high pressures necessary for a practical self-contained unit.

The first open-circuit scuba system was devised in 1925 by Yves Le Prieur in France. Inspired by the simple apparatus of  Air Liquide started selling the Cousteau-Gagnan regulator commercially as of 1946 under the name of ''scaphandre Cousteau-Gagnan'' or CG45 ("C" for Cousteau, "G" for Gagnan and 45 for the 1945

Air Liquide started selling the Cousteau-Gagnan regulator commercially as of 1946 under the name of ''scaphandre Cousteau-Gagnan'' or CG45 ("C" for Cousteau, "G" for Gagnan and 45 for the 1945

The alternative concept, developed in roughly the same time frame was closed-circuit scuba. The body consumes and metabolises only a part of the

The alternative concept, developed in roughly the same time frame was closed-circuit scuba. The body consumes and metabolises only a part of the  In the 1930s,

In the 1930s,

In 1715, British inventor John Lethbridge constructed a "diving suit". Essentially a wooden barrel about in length with two holes for the diver's arms sealed with leather cuffs, and a viewport of thick glass. It was reportedly used to dive as deep as , and was used to salvage substantial quantities of

In 1715, British inventor John Lethbridge constructed a "diving suit". Essentially a wooden barrel about in length with two holes for the diver's arms sealed with leather cuffs, and a viewport of thick glass. It was reportedly used to dive as deep as , and was used to salvage substantial quantities of  The first properly anthropomorphic design of ADS, built by the Carmagnolle brothers of Marseilles, France in 1882, featured rolling convolute joints consisting of partial sections of concentric spheres formed to create a close fit and kept watertight with a waterproof cloth. The suit had 22 of these joints: four in each leg, six per arm, and two in the body of the suit. The helmet possessed 25 individual glass viewing ports spaced at the average distance of the human eyes. Weighing , the Carmagnole ADS never worked properly and its joints never were entirely waterproof. It is now on display at the French National Navy Museum in Paris.

Another design was patented in 1894 by inventors John Buchanan and Alexander Gordon from Melbourne], Australia. The construction was based on a frame of spiral wires covered with waterproof material. The design was improved by Alexander Gordon by attaching the suit to the helmet and other parts and incorporating jointed radius rods in the limbs. This resulted in a flexible suit that could withstand high pressure. The suit was manufactured by British firm Siebe Gorman and trialed in Scotland in 1898.

American designer MacDuffy constructed the first suit to use ball bearings to provide joint movement in 1914; it was tested in New York City, New York to a depth of , but was not very successful. A year later, Harry L. Bowdoin of Bayonne, New Jersey, made an improved ADS with oil-filled rotary joints. The joints use a small duct to the interior of the joint to allow equalization of pressure. The suit was designed to have four joints in each arm and leg, and one joint in each thumb, for a total of eighteen. Four viewing ports and a chest-mounted lamp were intended to assist underwater vision. Unfortunately, there is no evidence that Bowdoin's suit was ever built or that it would have worked if it had been.

Atmospheric diving suits built by German firm Neufeldt and Kuhnke were used during the salvage of gold and silver bullion from the wreck of the British ship , an 8,000-ton P&O liner that sank in May 1922. The suit was relegated to duties as an observation chamber at the wreck's depth, and was successfully used to direct mechanical grabs which opened up the bullion storage. In 1917, Benjamin F. Leavitt of

The first properly anthropomorphic design of ADS, built by the Carmagnolle brothers of Marseilles, France in 1882, featured rolling convolute joints consisting of partial sections of concentric spheres formed to create a close fit and kept watertight with a waterproof cloth. The suit had 22 of these joints: four in each leg, six per arm, and two in the body of the suit. The helmet possessed 25 individual glass viewing ports spaced at the average distance of the human eyes. Weighing , the Carmagnole ADS never worked properly and its joints never were entirely waterproof. It is now on display at the French National Navy Museum in Paris.

Another design was patented in 1894 by inventors John Buchanan and Alexander Gordon from Melbourne], Australia. The construction was based on a frame of spiral wires covered with waterproof material. The design was improved by Alexander Gordon by attaching the suit to the helmet and other parts and incorporating jointed radius rods in the limbs. This resulted in a flexible suit that could withstand high pressure. The suit was manufactured by British firm Siebe Gorman and trialed in Scotland in 1898.

American designer MacDuffy constructed the first suit to use ball bearings to provide joint movement in 1914; it was tested in New York City, New York to a depth of , but was not very successful. A year later, Harry L. Bowdoin of Bayonne, New Jersey, made an improved ADS with oil-filled rotary joints. The joints use a small duct to the interior of the joint to allow equalization of pressure. The suit was designed to have four joints in each arm and leg, and one joint in each thumb, for a total of eighteen. Four viewing ports and a chest-mounted lamp were intended to assist underwater vision. Unfortunately, there is no evidence that Bowdoin's suit was ever built or that it would have worked if it had been.

Atmospheric diving suits built by German firm Neufeldt and Kuhnke were used during the salvage of gold and silver bullion from the wreck of the British ship , an 8,000-ton P&O liner that sank in May 1922. The suit was relegated to duties as an observation chamber at the wreck's depth, and was successfully used to direct mechanical grabs which opened up the bullion storage. In 1917, Benjamin F. Leavitt of

Although various atmospheric suits had been developed during the Victorian era, none of these suits had been able to overcome the basic design problem of constructing a joint that would remain flexible and watertight at depth without seizing up under pressure.

Pioneering British diving engineer, Joseph Salim Peress, invented the first truly usable atmospheric diving suit, the ''Tritonia'', in 1932 and was later involved in the construction of the famous

Although various atmospheric suits had been developed during the Victorian era, none of these suits had been able to overcome the basic design problem of constructing a joint that would remain flexible and watertight at depth without seizing up under pressure.

Pioneering British diving engineer, Joseph Salim Peress, invented the first truly usable atmospheric diving suit, the ''Tritonia'', in 1932 and was later involved in the construction of the famous

The ''Tritonia'' suit was upgraded into the first JIM suit, completed in November 1971. This suit underwent trials aboard in early 1972, and in 1976, the JIM suit set a record for the longest working dive below , lasting five hours and 59 minutes at a depth of . The first JIM suits were constructed from cast magnesium for its high strength-to-weight ratio and weighed approximately in air including the diver. They were in height and had a maximum operating depth of . The suit had a positive buoyancy of . Ballast was attached to the suit's front and could be jettisoned from within, allowing the operator to ascend to the surface at approximately per minute. The suit also incorporated a communication link and a jettisonable umbilical connection. The original JIM suit had eight annular oil-supported universal joints, one in each shoulder and lower arm, and one at each hip and knee. The JIM operator received air through an oral/nasal mask that attached to a lung-powered scrubber that had a life-support duration of approximately 72 hours. Operations in arctic conditions with water temperatures of -1.7 °C for over five hours were successfully carried out using woolen thermal protection and neoprene boots. In 30 °C water, the suit was reported to be uncomfortably hot during heavy work.

As technology improved and operational knowledge grew, Oceaneering upgraded its fleet of JIMs. The magnesium construction was replaced with glass-reinforced plastic (GRP) and the single joints with segmented ones, each allowing seven degrees of motion, and when added together giving the operator a very great range of motion. In addition, the four-port domed top of the suit was replaced by a transparent acrylic one that was taken from Wasp, this allowed the operator a much-improved field of vision. Trials were also carried out by the Ministry of Defence on a flying Jim suit powered from the surface through an umbilical cable. This resulted in a hybrid suit with the ability to work on the sea bed as well as mid-water.

The ''Tritonia'' suit was upgraded into the first JIM suit, completed in November 1971. This suit underwent trials aboard in early 1972, and in 1976, the JIM suit set a record for the longest working dive below , lasting five hours and 59 minutes at a depth of . The first JIM suits were constructed from cast magnesium for its high strength-to-weight ratio and weighed approximately in air including the diver. They were in height and had a maximum operating depth of . The suit had a positive buoyancy of . Ballast was attached to the suit's front and could be jettisoned from within, allowing the operator to ascend to the surface at approximately per minute. The suit also incorporated a communication link and a jettisonable umbilical connection. The original JIM suit had eight annular oil-supported universal joints, one in each shoulder and lower arm, and one at each hip and knee. The JIM operator received air through an oral/nasal mask that attached to a lung-powered scrubber that had a life-support duration of approximately 72 hours. Operations in arctic conditions with water temperatures of -1.7 °C for over five hours were successfully carried out using woolen thermal protection and neoprene boots. In 30 °C water, the suit was reported to be uncomfortably hot during heavy work.

As technology improved and operational knowledge grew, Oceaneering upgraded its fleet of JIMs. The magnesium construction was replaced with glass-reinforced plastic (GRP) and the single joints with segmented ones, each allowing seven degrees of motion, and when added together giving the operator a very great range of motion. In addition, the four-port domed top of the suit was replaced by a transparent acrylic one that was taken from Wasp, this allowed the operator a much-improved field of vision. Trials were also carried out by the Ministry of Defence on a flying Jim suit powered from the surface through an umbilical cable. This resulted in a hybrid suit with the ability to work on the sea bed as well as mid-water.

In 1987, the "

In 1987, the "

File:Exosuit Side.jpg, Side view of Exosuit

File:Exosuit Back.jpg, Back view of Exosuit

French physiologist

French physiologist

The history of

The history of underwater diving

Underwater diving, as a human activity, is the practice of descending below the water's surface to interact with the environment. It is also often referred to as diving, an ambiguous term with several possible meanings, depending on contex ...

starts with freediving

Freediving, free-diving, free diving, breath-hold diving, or skin diving is a form of underwater diving that relies on breath-holding until resurfacing rather than the use of breathing apparatus such as scuba gear.

Besides the limits of breath-h ...

as a widespread means of hunting and gathering, both for food and other valuable resources such as pearls and coral

Corals are marine invertebrates within the class Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact colonies of many identical individual polyps. Coral species include the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and ...

, By classical Greek and Roman times commercial

Commercial may refer to:

* a dose of advertising conveyed through media (such as - for example - radio or television)

** Radio advertisement

** Television advertisement

* (adjective for:) commerce, a system of voluntary exchange of products and s ...

applications such as sponge diving

Sponge diving is underwater diving to collect soft natural sponges for human use.

Background

Most sponges are too rough for general use due to their structural spicules composed of calcium carbonate or silica. But two genera, ''Hippospongia'' ...

and marine salvage were established, Military diving

Underwater divers may be employed in any branch of an armed force, including the navy, army, marines, air force and coast guard.

Scope of operations includes: search and recovery, search and rescue, hydrographic survey, explosive ordnance dispo ...

also has a long history, going back at least as far as the Peloponnesian War, with recreational

Recreation is an activity of leisure, leisure being discretionary time. The "need to do something for recreation" is an essential element of human biology and psychology. Recreational activities are often done for enjoyment, amusement, or pleasur ...

and sporting applications being a recent development. Technological development in ambient pressure

Ambient or Ambiance or Ambience may refer to:

Music and sound

* Ambience (sound recording), also known as atmospheres or backgrounds

* Ambient music, a genre of music that puts an emphasis on tone and atmosphere

* ''Ambient'' (album), by Moby

* ...

diving started with stone weights (skandalopetra

diving () dates from ancient Greece, when it was used by sponge fishermen, and has been re-discovered in recent years as a freediving discipline. It was in this discipline that the first world record in freediving was registered, when the Greek sp ...

) for fast descent. In the 16th and 17th centuries diving bell

A diving bell is a rigid chamber used to transport divers from the surface to depth and back in open water, usually for the purpose of performing underwater work. The most common types are the open-bottomed wet bell and the closed bell, which c ...

s became functionally useful when a renewable supply of air could be provided to the diver at depth, and progressed to surface supplied diving helmets—in effect miniature diving bells covering the diver's head and supplied with compressed air by manually operated pumps—which were improved by attaching a waterproof suit to the helmet and in the early 19th century became the standard diving dress

Standard diving dress, also known as hard-hat or copper hat equipment, deep sea diving suit or heavy gear, is a type of diving suit that was formerly used for all relatively deep underwater work that required more than breath-hold duration, which ...

.

Limitations in the mobility of the surface supplied systems encouraged the development of both open circuit Open circuit may refer to:

*Open-circuit scuba, a type of SCUBA-diving equipment where the user breathes from the set and then exhales to the surroundings without recycling the exhaled air

* Open-circuit test, a method used in electrical engineerin ...

and closed circuit scuba in the 20th century, which allow the diver a much greater autonomy. These also became popular during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

for clandestine military operations, and post-war for scientific

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence for ...

, search and rescue, media diving

Media diving is underwater diving in support of the media industries, including the practice of underwater photography and underwater cinematography outside of normal recreational interests. Media diving is often carried out in support of televis ...

, recreational and technical diving

Technical diving (also referred to as tec diving or tech diving) is scuba diving that exceeds the agency-specified limits of recreational diving for non-professional purposes. Technical diving may expose the diver to hazards beyond those normally ...

. The heavy free-flow surface supplied copper helmets evolved into lightweight demand helmets, which are more economical with breathing gas, which is particularly important for deeper dives and expensive helium based breathing mixtures, and saturation diving

Saturation diving is diving for periods long enough to bring all tissues into equilibrium with the partial pressures of the inert components of the breathing gas used. It is a diving mode that reduces the number of decompressions divers working ...

reduced the risks of decompression sickness

Decompression sickness (abbreviated DCS; also called divers' disease, the bends, aerobullosis, and caisson disease) is a medical condition caused by dissolved gases emerging from solution as bubbles inside the body tissues during decompressio ...

for deep and long exposures.

An alternative approach was the development of the " single atmosphere" or armoured suit, which isolates the diver from the pressure at depth, at the cost of great mechanical complexity and limited dexterity. The technology first became practicable in the middle 20th century. Isolation of the diver from the environment was taken further by the development of remotely operated underwater vehicle

A remotely operated underwater vehicle (technically ROUV or just ROV) is a tethered underwater mobile device, commonly called ''underwater robot''.

Definition

This meaning is different from remote control vehicles operating on land or in the a ...

s in the late 20th century, where the operator controls the ROV from the surface, and autonomous underwater vehicle

An autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) is a robot that travels underwater without requiring input from an operator. AUVs constitute part of a larger group of undersea systems known as unmanned underwater vehicles, a classification that includ ...

s, which dispense with an operator altogether. All of these modes are still in use and each has a range of applications where it has advantages over the others, though diving bells have largely been relegated to a means of transport for surface supplied divers. In some cases, combinations are particularly effective, such as the simultaneous use of surface orientated or saturation surface supplied diving equipment and work or observation class remotely operated vehicles.

Although the pathophysiology of decompression sickness is not yet fully understood, decompression practice

The practice of decompression by divers comprises the planning and monitoring of the profile indicated by the algorithms or tables of the chosen decompression model, to allow asymptomatic and harmless release of excess inert gases dissolved in ...

has reached a stage where the risk is fairly low, and most incidences are successfully treated by therapeutic recompression

Hyperbaric medicine is medical treatment in which an ambient pressure greater than sea level atmospheric pressure is a necessary component. The treatment comprises hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT), the medical use of oxygen at an ambient pressure ...

and hyperbaric oxygen therapy

Hyperbaric medicine is medical treatment in which an ambient pressure greater than sea level atmospheric pressure is a necessary component. The treatment comprises hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT), the medical use of oxygen at an ambient pressure ...

. Mixed breathing gases are routinely used to reduce the effects of the hyperbaric environment on ambient pressure divers.

Freediving

ancient

Ancient history is a time period from the beginning of writing and recorded human history to as far as late antiquity. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the Sumerian cuneiform script. Ancient history cov ...

culture

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups ...

s to gather food and other valuable resources such as pearls and precious coral, and later to reclaim sunken valuables, and to help aid military campaigns. Breathhold diving was the only method available, occasionally using reed snorkels in shallow water, and stone weights for deeper dives

Underwater diving for commercial purposes may have begun in Ancient Greece, since both Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

and Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

mention the sponge

Sponges, the members of the phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), are a basal animal clade as a sister of the diploblasts. They are multicellular organisms that have bodies full of pores and channels allowing water to circulate throug ...

as being used for bathing. The island of Kalymnos

Kalymnos ( el, Κάλυμνος) is a Greek island and municipality in the southeastern Aegean Sea. It belongs to the Dodecanese island chain, between the islands of Kos (south, at a distance of ) and Leros (north, at a distance of less than ): ...

was a main centre of diving for sponges. By using weights (skandalopetra

diving () dates from ancient Greece, when it was used by sponge fishermen, and has been re-discovered in recent years as a freediving discipline. It was in this discipline that the first world record in freediving was registered, when the Greek sp ...

) of as much as to speed the descent, breath-holding divers would descend to depths up to for as much as five minutes to collect sponges. Sponges were not the only valuable harvest to be found on the sea floor; the harvesting of red coral

Precious coral, or red coral, is the common name given to a genus of marine corals, ''Corallium''. The distinguishing characteristic of precious corals is their durable and intensely colored red or pink-orange skeleton, which is used for ma ...

was also quite popular. A variety of valuable shells or fish

Fish are aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish as well as various extinct related groups. Approximately 95% of ...

could be harvested in this way, creating a demand for divers to harvest the treasures of the sea, which could also include the sunken riches of other seafarers.

The Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

had large amounts of sea trade. As a result, there were many shipwrecks

A shipwreck is the wreckage of a ship that is located either beached on land or sunken to the bottom of a body of water. Shipwrecking may be intentional or unintentional. Angela Croome reported in January 1999 that there were approximately ...

, so divers were often hired to salvage whatever they could from the seabed. Divers would swim down to the wreck and choose the pieces to salvage.

Divers were also used in warfare. They could be used for underwater reconnaissance when ships were approaching an enemy harbor, and if underwater defenses were found, the divers would disassemble them if possible. During the Peloponnesian War, divers were used to get past enemy blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are leg ...

s to relay messages and provide supplies to allies or troops that were cut off by the blockade. These divers and swimmers were occasionally used as saboteur

Sabotage is a deliberate action aimed at weakening a polity, effort, or organization through subversion, obstruction, disruption, or destruction. One who engages in sabotage is a ''saboteur''. Saboteurs typically try to conceal their identiti ...

s, drilling holes in enemy hulls, cutting ships rigging and mooring

A mooring is any permanent structure to which a vessel may be secured. Examples include quays, wharfs, jetties, piers, anchor buoys, and mooring buoys. A ship is secured to a mooring to forestall free movement of the ship on the water. An ''an ...

lines.

In Japan, the Ama divers

are Japanese divers famous for collecting pearls, though traditionally their main catch is seafood. The vast majority of are women.

Terminology

There are several sea occupations that are pronounced "ama" and several words that refer to sea oc ...

began to collect pearls about 2,000 years ago. Free-diving was the primary source of income for many Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bod ...

nationals such as Qatari

Qatar (, ; ar, قطر, Qaṭar ; local vernacular pronunciation: ), officially the State of Qatar,) is a country in Western Asia. It occupies the Qatar Peninsula on the northeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in the Middle East; it sh ...

s, Emiratis

The Emiratis ( ar, الإماراتيون) are the native Arab citizen population of the United Arab Emirates. Their largest concentration is in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), where there are about approximately 1.5 million Emiratis.

Formerly ...

, Bahrain

Bahrain ( ; ; ar, البحرين, al-Bahrayn, locally ), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, ' is an island country in Western Asia. It is situated on the Persian Gulf, and comprises a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and an ...

is, and Kuwait

Kuwait (; ar, الكويت ', or ), officially the State of Kuwait ( ar, دولة الكويت '), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated in the northern edge of Eastern Arabia at the tip of the Persian Gulf, bordering Iraq to the nort ...

is. As a result, Qatari, Emirati, and Bahraini heritage promoters have popularized recreational and serious events associated with freediving, underwater equipment, and related activities such as snorkeling.

Diving bells

The diving bell is one of the earliest types of equipment for underwater work and exploration. Its use was first described by

The diving bell is one of the earliest types of equipment for underwater work and exploration. Its use was first described by Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

in the 4th century BC: "...they enable the divers to respire equally well by letting down a cauldron, for this does not fill with water, but retains the air, for it is forced straight down into the water." According to Roger Bacon, Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

explored the Mediterranean on the authority of Ethicus the astronomer.

Diving bell

A diving bell is a rigid chamber used to transport divers from the surface to depth and back in open water, usually for the purpose of performing underwater work. The most common types are the open-bottomed wet bell and the closed bell, which c ...

s were developed in the 16th and 17th century as the first significant mechanical aid to underwater diving. They were rigid open-bottomed chambers lowered into the water and ballasted to remain upright and to sink even when full of air.

The first reliably recorded use of a diving bell was by Guglielmo de Lorena in 1535 to explore Caligula's barge

Barge nowadays generally refers to a flat-bottomed inland waterway vessel which does not have its own means of mechanical propulsion. The first modern barges were pulled by tugs, but nowadays most are pushed by pusher boats, or other vessels ...

s in Lake Nemi

Lake Nemi ( it, Lago di Nemi, la, Nemorensis Lacus, also called Diana's Mirror, la, Speculum Dianae) is a small circular volcanic lake in the Lazio region of Italy south of Rome, taking its name from Nemi, the largest town in the area, that ...

. In 1616, Franz Kessler

Franz Kessler (c. 1580–1650) was a portrait painter, scholar, inventor and alchemist living in the Holy Roman Empire during the 16th and 17th centuries.

Writing

He wrote a number of books and pamphlets: a book on stoves, on making sundials ...

built an improved diving bell.

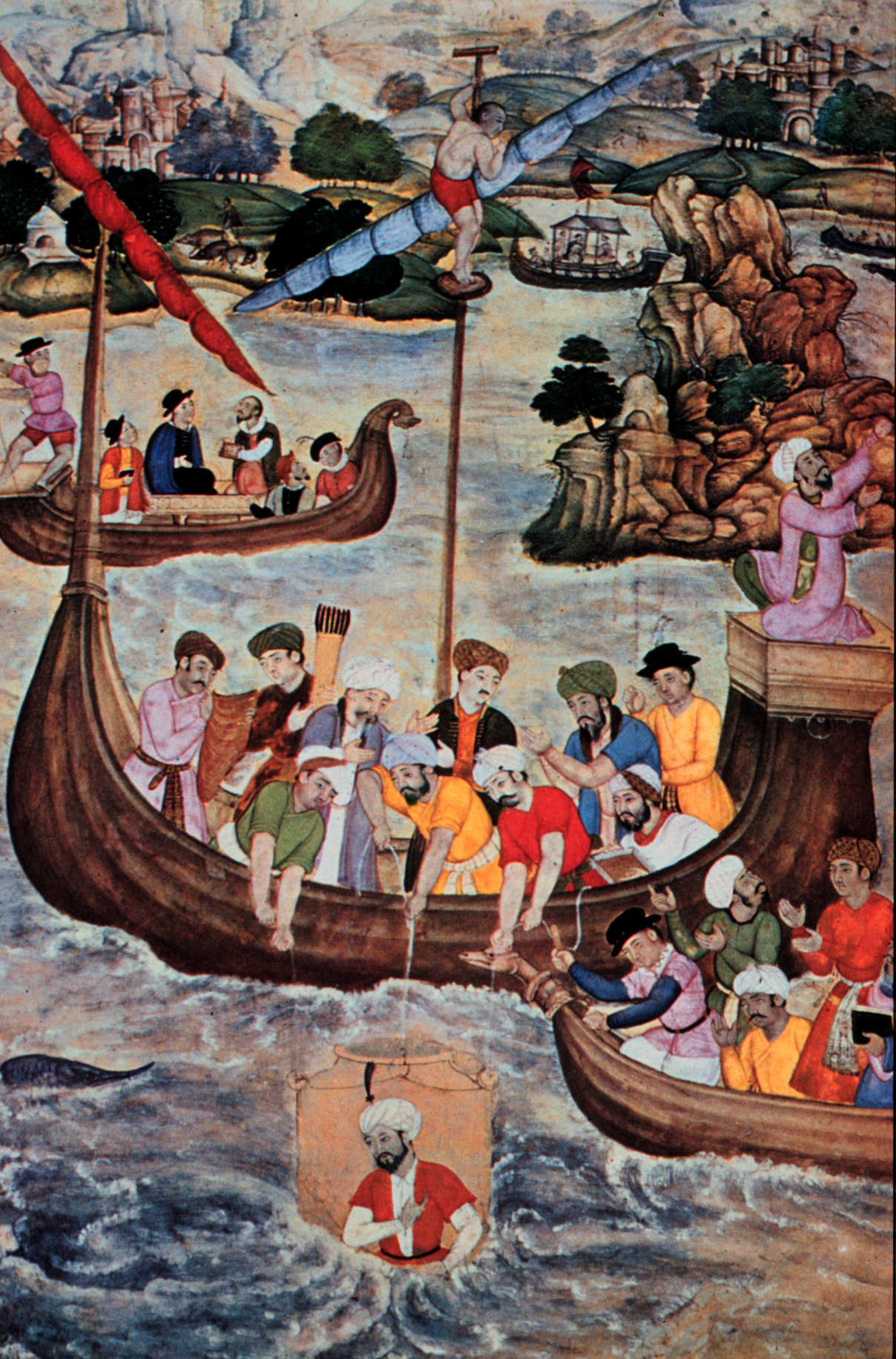

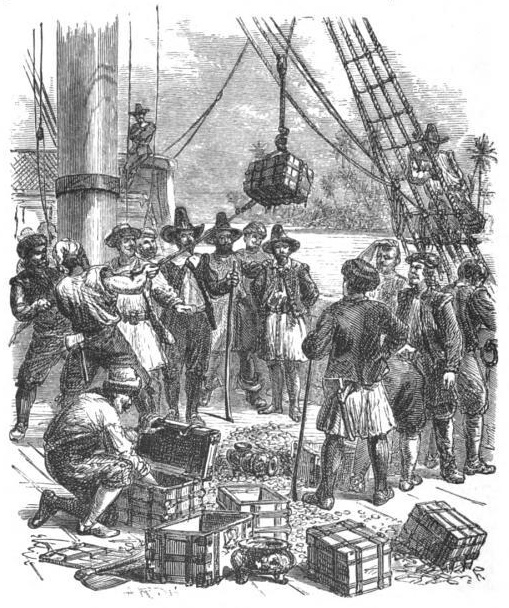

In 1658, Albrecht von Treileben was contracted by King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden to salvage the warship , which sank outside Stockholm harbor in about of water on its maiden voyage in 1628. Between 1663 and 1665 von Treileben's divers were successful in raising most of the cannon, working from a diving bell with an estimated free air capacity of about for periods of about 15 minutes at a time in dark water with a temperature of about . In late 1686, Sir William Phipps convinced investors to fund an expedition to what is now Haiti and the

In 1658, Albrecht von Treileben was contracted by King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden to salvage the warship , which sank outside Stockholm harbor in about of water on its maiden voyage in 1628. Between 1663 and 1665 von Treileben's divers were successful in raising most of the cannon, working from a diving bell with an estimated free air capacity of about for periods of about 15 minutes at a time in dark water with a temperature of about . In late 1686, Sir William Phipps convinced investors to fund an expedition to what is now Haiti and the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares with ...

to find sunken treasure, despite the location of the shipwreck being based entirely on rumor and speculation. In January 1687, Phipps found the wreck of the Spanish galleon

Galleons were large, multi-decked sailing ships first used as armed cargo carriers by European states from the 16th to 18th centuries during the age of sail and were the principal vessels drafted for use as warships until the Anglo-Dutch W ...

''Nuestra Señora de la Concepción'' off the coast of Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 ( Distrito Nacional)

, webs ...

. Some sources say they used an inverted container as a diving bell for the salvage operation while others say the crew was assisted by Indian divers in the shallow waters. The operation lasted from February to April 1687 during which time they salvaged jewels, some gold, and 30 tons of silver which, at the time, was worth over £200,000.

In 1691, Edmond Halley

Edmond (or Edmund) Halley (; – ) was an English astronomer, mathematician and physicist. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, succeeding John Flamsteed in 1720.

From an observatory he constructed on Saint Helena in 1676–77, H ...

completed plans for a greatly improved diving bell, capable of remaining submerged for extended periods of time, and fitted with a window for the purpose of undersea exploration. The atmosphere was replenished by way of weighted barrels of air sent down from the surface. In a demonstration, Halley and five companions dived to in the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

, and remained there for over an hour and a half. Improvements made to it over time extended his underwater exposure time to over four hours.

In 1775, Charles Spalding

Charles Spalding (29 October 1738 – 2 June 1783) was an Edinburgh confectioner and amateur engineer who made improvements to the diving bell. He died while diving to the wreck of the ''Belgioso'' in Dublin Bay using a diving bell of his ow ...

, an Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian on the southern shore of t ...

confectioner, improved on Edmond Halley's design by adding a system of balance-weights to ease the raising and lowering of the bell, along with a series of ropes for signaling to the surface crew. Spalding and his nephew, Ebenezer Watson, later suffocated off the coast of Dublin in 1783 doing salvage work in a diving bell of Spalding's design.

In 1689, Denis Papin

Denis Papin FRS (; 22 August 1647 – 26 August 1713) was a French physicist, mathematician and inventor, best known for his pioneering invention of the steam digester, the forerunner of the pressure cooker and of the steam engine.

Early ...

had suggested that the pressure and fresh air inside a diving bell could be maintained by a force pump or bellows. His idea was implemented exactly 100 years later by the engineer John Smeaton

John Smeaton (8 June 1724 – 28 October 1792) was a British civil engineer responsible for the design of bridges, canals, harbours and lighthouses. He was also a capable mechanical engineer and an eminent physicist. Smeaton was the fi ...

, who built the first workable diving air pump in 1789.

Surface supplied diving suits

In 1602, the Spanish military engineer Jerónimo de Ayanz y Beaumont developed the first documented diving dress. It was tested the same year in the

In 1602, the Spanish military engineer Jerónimo de Ayanz y Beaumont developed the first documented diving dress. It was tested the same year in the Pisuerga

The Pisuerga is a river in northern Spain, the Duero's second largest tributary. It rises in the Cantabrian Mountains in the province of Palencia, autonomous region of Castile and León.

Its traditional source is called Fuente Cobre, but it has ...

river (Valladolid

Valladolid () is a municipality in Spain and the primary seat of government and de facto capital of the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. It has a population around 300,000 peop ...

, Spain). King Philip the Third attended the demonstration.

Two English inventors developed diving suits in the 1710s. John Lethbridge

John Lethbridge (1675–1759) invented the first underwater diving machine in 1715. He lived in the county of Devon in South West England and reportedly had 17 children. He is the subject of the Fisherman's Friends song John in the Barrel.

John ...

built a completely enclosed suit to aid in salvage work. It consisted of a pressure-proof air-filled barrel with a glass viewing hole and two watertight enclosed sleeves. After testing this machine in his garden pond specially built for the purpose, Lethbridge dived on a number of wrecks: four English men-of-war

The man-of-war (also man-o'-war, or simply man) was a Royal Navy expression for a powerful warship or frigate from the 16th to the 19th century. Although the term never acquired a specific meaning, it was usually reserved for a ship armed w ...

, one East Indiaman, two Spanish galleons, and a number of galleys. He became very wealthy as a result of his salvages. One of his better-known recoveries was on the Dutch ''Slot ter Hooge'', which had sunk off Madeira with over three tons of silver on board.

At the same time, Andrew Becker created a leather-covered diving suit with a windowed helmet. The suit used a system of tubes for inhaling and exhaling, and Becker demonstrated his suit in the River Thames at London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, during which he remained submerged for an hour. These suits were of limited use as there was still no practical system for replenishing the air supply during the dive.

Open diving dress

In 1405,

In 1405, Konrad Kyeser

Konrad Kyeser (26 August 1366 – after 1405) was a German military engineer and the author of ''Bellifortis'' (c. 1405), a book on military technology that was popular throughout the 15th century. Originally conceived for King Wenceslaus, ...

described a diving dress made of a leather jacket and metal helmet with two glass windows. The jacket and helmet were lined by sponge to "retain the air" and a leather pipe was connected to a bag of air. A diving suit design was illustrated in a book by Vegetius

Publius (or Flavius) Vegetius Renatus, known as Vegetius (), was a writer of the Later Roman Empire (late 4th century). Nothing is known of his life or station beyond what is contained in his two surviving works: ''Epitoma rei militaris'' (also r ...

in 1511. Borelli designed diving equipment that consisted of a metal helmet, a pipe to "regenerate" air, a leather suit, and a means of controlling the diver's buoyancy

Buoyancy (), or upthrust, is an upward force exerted by a fluid that opposes the weight of a partially or fully immersed object. In a column of fluid, pressure increases with depth as a result of the weight of the overlying fluid. Thus the ...

. In 1690, Thames Divers, a short-lived London diving company, gave public demonstrations of a Vegetius type shallow water diving dress. Karl Heinrich Klingert designed a full diving dress in 1797. This design consisted of a large metal helmet and a similarly large metal belt connected by a leather jacket and pants. This apparatus was successfully demonstrated in the river Oder, but was handicapped by not having a reliable air supply system.

In 1800, Peter Kreeft

Peter John Kreeft (; born March 16, 1937) is a professor of philosophy at Boston College and The King's College. A convert to Roman Catholicism, he is the author of over eighty books on Christian philosophy, theology and apologetics. He also f ...

presented his diving apparatus to the Swedish king, and used it successfully.

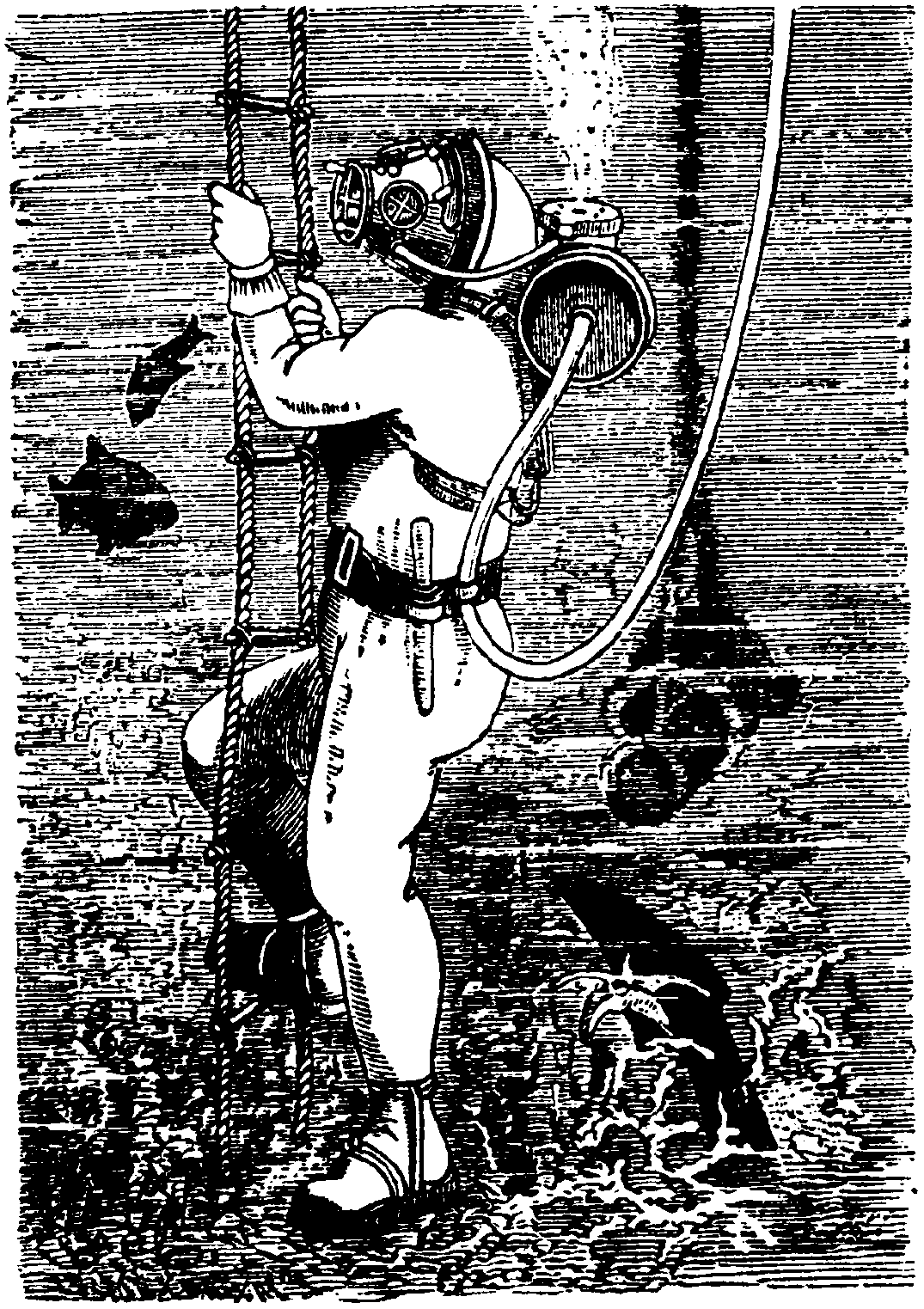

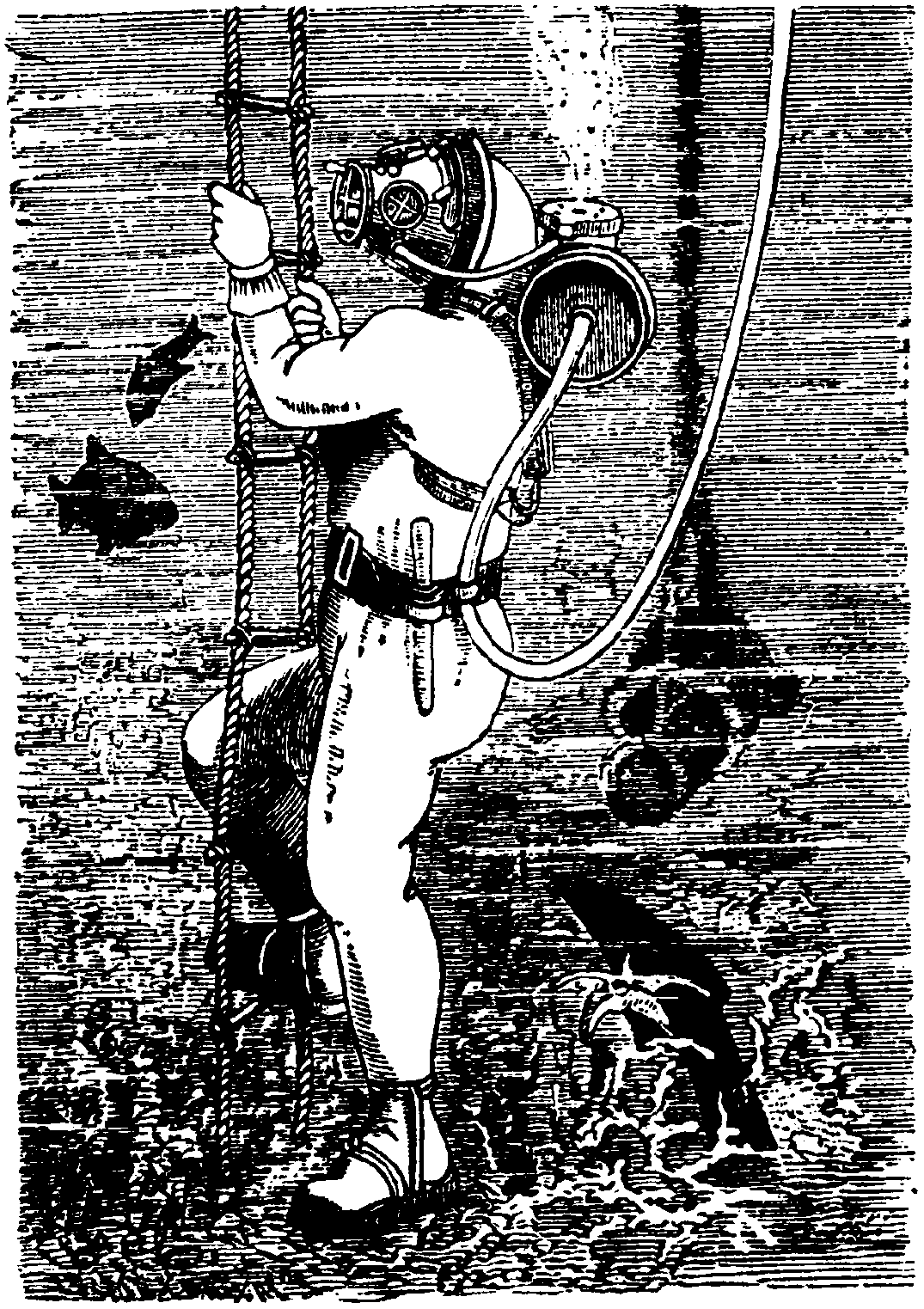

In 1819, Augustus Siebe invented an open diving suit which only covered the top portion of the body. The suit included a metal helmet which was riveted to a waterproof jacket that ended below the diver's waist. The suit worked like a diving bell—air pumped into the suit escaped at the bottom edge. The diver was extremely limited in range of motion and had to move about in a more or less upright position. It wasn't until 1837 that Siebe changed the design to a closed system with only the hands left out of the suit with an air-tight encasing around the wrists.

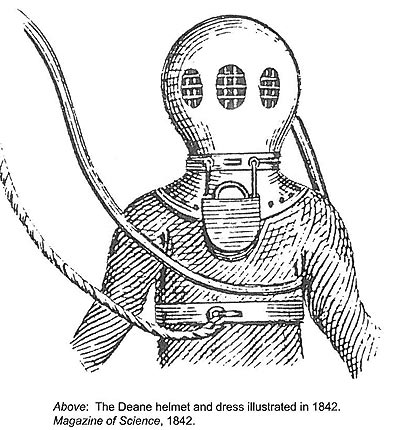

The first widely successful diving helmet

A diving helmet is a rigid head enclosure with a breathing gas supply used in underwater diving. They are worn mainly by professional divers engaged in surface-supplied diving, though some models can be used with scuba equipment. The upper part ...

s were produced by the brothers Charles and John Deane in the 1820s. Inspired by a fire accident he witnessed in a stable in England, he designed and patented a "Smoke Helmet" to be used by firemen in smoke-filled areas in 1823. The apparatus comprised a copper helmet with an attached flexible collar and garment. A long leather hose attached to the rear of the helmet was to be used to supply air - the original concept being that it would be pumped using a double bellows. A short pipe allowed excess air to escape. The garment was constructed from leather or airtight cloth, secured by straps.

The brothers had insufficient funds to build the equipment themselves so they sold the patent to their employer Edward Barnard. It was not until 1827 that the first smoke helmets were built by German-born British engineer Augustus Siebe. In 1828 they decided to find another application for their device and converted it into a diving helmet. They marketed the helmet with a loosely attached "diving suit" so that a diver could perform salvage work but only in a full vertical position, otherwise water entered the suit.

Whitstable

Whitstable () is a town on the north coast of Kent adjoining the convergence of the Swale Estuary and the Greater Thames Estuary in southeastern England, north of Canterbury and west of Herne Bay. The 2011 Census reported a population of ...

for trials of their new underwater apparatus, establishing the diving industry in the town. In 1834, Charles used his diving helmet and suit in a successful attempt on the wreck of at Spithead

Spithead is an area of the Solent and a roadstead off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast. It receives its name from the Spit, a sandbank stretching south from the Hampshire ...

, during which he recovered 28 of the ship's cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

. In 1836, John Deane recovered from the shipwreck timbers, guns, longbow

A longbow (known as warbow in its time, in contrast to a hunting bow) is a type of tall bow that makes a fairly long draw possible. A longbow is not significantly recurved. Its limbs are relatively narrow and are circular or D-shaped in cross ...

s, and other items. By 1836, the Deane brothers had produced the world's first diving manual ''Method of Using Deane's Patent Diving Apparatus'' which explained in detail the workings of the apparatus and pump, as well as safety precautions.

Standard diving dress

In the 1830s, the Deane brothers asked Augustus Siebe to improve their underwater helmet design. Expanding on improvements already made by another engineer, George Edwards, Siebe produced his own design; a helmet fitted to a full-length watertight canvasdiving suit

A diving suit is a garment or device designed to protect a diver from the underwater environment. A diving suit may also incorporate a breathing gas supply (such as for a standard diving dress or atmospheric diving suit). but in most cases the te ...

. Siebe introduced various modifications on his diving dress design to accommodate the requirements of the salvage team on the wreck of ''Royal George'', including making the bonnet of the helmet detachable from the corselet

In women's clothing, a corselet or corselette is a type of foundation garment, sharing elements of both bras and girdles. It extends from straps over the shoulders down the torso, and stops around the top of the legs. It may incorporate lace ...

. His improved design gave rise to the typical standard diving dress

Standard diving dress, also known as hard-hat or copper hat equipment, deep sea diving suit or heavy gear, is a type of diving suit that was formerly used for all relatively deep underwater work that required more than breath-hold duration, which ...

which revolutionised underwater civil engineering

Civil engineering is a professional engineering discipline that deals with the design, construction, and maintenance of the physical and naturally built environment, including public works such as roads, bridges, canals, dams, airports, sewa ...

, underwater salvage, commercial diving

Commercial diving may be considered an application of professional diving where the diver engages in underwater work for industrial, construction, engineering, maintenance or other commercial purposes which are similar to work done out of the wate ...

and naval diving

Professional diving is underwater diving where the divers are paid for their work. The procedures are often regulated by legislation and codes of practice as it is an inherently hazardous occupation and the diver works as a member of a team. D ...

. The watertight suit allowed divers to wear layers of dry clothing underneath to suit the water temperature. These generally included heavy stockings, guernseys, and the iconic woolen cap that is still occasionally worn by divers.

Early diving work

In the early years of the diving suit, divers were often employed for cleaning and maintenance of seagoing vessels which could require the efforts of multiple divers. Ships that did not have diving suits available would commission diving companies to do underwater maintenance of ships' hulls, as a clean hull would increase the speed of the vessel. The average time spent diving for these purposes was between four and seven hours. The Office of the Admiralty and Marine Affairs adopted the diving suit in the 1860s. Divers duties included underwater repair of vessels, maintenance, and cleaning of propellers, retrieval of lost anchors and chains, and removing seaweed and other fouling from the hull that could hinder movement.Development of salvage diving operations

''Royal George'', a 100-gun

''Royal George'', a 100-gun first-rate

In the rating system of the British Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships, a first rate was the designation for the largest ships of the line. Originating in the Jacobean era with the designation of Ships Royal capable of carrying ...

ship of the line of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

, sank undergoing routine maintenance work in 1782. Charles Spalding used a diving bell to recover six iron 12-pounder guns and nine brass 12-pounders in the same year.

In 1839, Major-General Charles Pasley

General Sir Charles William Pasley (8 September 1780 – 19 April 1861) was a British soldier and military engineer who wrote the defining text on the role of the post-American Revolution British Empire: ''An Essay on the Military Policy and Ins ...

, at the time a colonel of the Royal Engineers, commenced operations. He had previously destroyed some old wrecks in the Thames and intended to break up ''Royal George'' with gunpowder charges and then salvage as much as possible using divers. The Deane brothers were commissioned to perform salvage work on the wreck. Using their new air-pumped diving helmets, they managed to recover about two dozen cannon.

Pasley's diving salvage operation set many diving milestones, including the first recorded use of the buddy system

The buddy system is a procedure in which two individuals, the "buddies", operate together as a single unit so that they are able to monitor and help each other.

As per Merriam-Webster, the first known use of the phrase "buddy system" goes as far ...

in diving, when he gave instructions to his divers to operate in pairs. In addition, the first emergency swimming ascent was made by a diver after his air line became tangled and he had to cut it free. A less fortunate milestone was the first medical account of a diving barotrauma. The early diving helmets had no non-return valve

A check valve, non-return valve, reflux valve, retention valve, foot valve, or one-way valve is a valve that normally allows fluid (liquid or gas) to flow through it in only one direction.

Check valves are two-port valves, meaning they have ...

s, so if a hose was severed near the surface, the ambient pressure air around the diver's head rapidly drained from the helmet to the lower pressure at the break, leaving a pressure difference between the inside and outside of the helmet that could cause injurious and sometimes life-threatening effects. At the British Association for the Advancement of Science meeting in 1842, Sir John Richardson described the diving apparatus and treatment of diver Roderick Cameron following an injury that occurred on 14 October 1841 during the salvage operations.

Pasley recovered 12 more guns in 1839, 11 more in 1840, and 6 in 1841. In 1842 he recovered only one iron 12-pounder because he ordered the divers to concentrate on removing the hull timbers rather than search for guns. Other items recovered, in 1840, included the surgeon's brass instruments, silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from the ...

garments of satin

A satin weave is a type of fabric weave that produces a characteristically glossy, smooth or lustrous material, typically with a glossy top surface and a dull back. It is one of three fundamental types of textile weaves alongside plain weave ...

weave "of which the silk was perfect", and pieces of leather; but no woolen clothing. By 1843 the whole of the keel and the bottom timbers had been raised and the site was declared clear.

Self-contained air supply equipment

A drawback to the equipment pioneered by Deane and Siebe was the requirement for a constant supply of air pumped from the surface. This restricted the movements and range of the diver and was also potentially hazardous as the supply could get cut off for a number of reasons. Early attempts at creating systems that would allow divers to carry a portable breathing gas source did not succeed, as the compression and storage technology was not advanced enough to allow compressed air to be stored in containers at sufficiently high pressures. By the end of the nineteenth century, two basic templates forscuba

Scuba may refer to:

* Scuba diving

** Scuba set, the equipment used for scuba (Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus) diving

* Scuba, an in-memory database developed by Facebook

* Submillimetre Common-User Bolometer Array, either of two in ...

, (self-contained underwater breathing apparatus), had emerged: open-circuit scuba

A scuba set, originally just scuba, is any breathing apparatus that is entirely carried by an underwater diver and provides the diver with breathing gas at the ambient pressure. ''Scuba'' is an anacronym for self-contained underwater breathing ...

where the diver's exhaust is vented directly into the water, and closed-circuit scuba where the diver's unused oxygen is filtered from the carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide ( chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is trans ...

and recirculated.

A scuba set is characterized by full independence from the surface during use, by providing breathing gas

A breathing gas is a mixture of gaseous chemical elements and compounds used for respiration. Air is the most common and only natural breathing gas, but other mixtures of gases, or pure oxygen, are also used in breathing equipment and enclosed ...

carried by the diver. Early attempts to reach this autonomy from the surface were made in the 18th century by the Englishman

The English people are an ethnic group and nation native to England, who speak the English language, a West Germanic language, and share a common history and culture. The English identity is of Anglo-Saxon origin, when they were known in ...

John Lethbridge, who invented and successfully built his own underwater diving machine in 1715. The air inside the suit allowed a short period of diving before it had to be surfaced for replenishment.

Open-circuit scuba

None of those inventions solved the problem of high pressure when compressed air must be supplied to the diver (as in modern regulators); they were mostly based on a constant-flow supply of the air. The compression and storage technology was not advanced enough to allow compressed air to be stored in containers at sufficiently high pressures to allow useful dive times. An early diving dress using a compressed air reservoir was designed and built in 1771 by ''Sieur'' Fréminet ofParis

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

who conceived an autonomous breathing machine equipped with a reservoir, dragged behind the diver or mounted on his back. Fréminet called his invention ''machine hydrostatergatique'' and used it successfully for more than ten years in the harbors of Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very ...

and Brest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

* Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

* Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

** Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

*Br ...

, as stated in the explanatory text of a 1784 painting.

The Frenchman Paul Lemaire d'Augerville built and used autonomous diving equipment

Diving equipment is equipment used by underwater divers to make diving activities possible, easier, safer and/or more comfortable. This may be equipment primarily intended for this purpose, or equipment intended for other purposes which is found ...

in 1824, as did the British William H. James in 1825. James' helmet was made of "thin copper or sole of leather" with a plate window, and the air was supplied from an iron reservoir. A similar system was used in 1831 by the American Charles Condert, who died in 1832 while testing his invention in the East River

The East River is a saltwater tidal estuary in New York City. The waterway, which is actually not a river despite its name, connects Upper New York Bay on its south end to Long Island Sound on its north end. It separates the borough of Quee ...

at only deep. After having traveled to England and discovering William James' invention, the French physician , from Argentan (in Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

), patented the oldest known regulator mechanism in 1838. Guillaumet's invention was supplied with air from the surface and was never mass-produced

Mass production, also known as flow production or continuous production, is the production of substantial amounts of standardized products in a constant flow, including and especially on assembly lines. Together with job production and ba ...

due to problems with safety.

An important step in the development of open-circuit scuba technology was the invention of the demand regulator in 1864 by the French engineers Auguste Denayrouze and Benoît Rouquayrol. Their suit was the first to supply air to the user by adjusting the flow according to the diver's requirements. The system still had to use surface supply, as the storage cylinders of the 1860s were not able to withstand the high pressures necessary for a practical self-contained unit.

The first open-circuit scuba system was devised in 1925 by Yves Le Prieur in France. Inspired by the simple apparatus of

An important step in the development of open-circuit scuba technology was the invention of the demand regulator in 1864 by the French engineers Auguste Denayrouze and Benoît Rouquayrol. Their suit was the first to supply air to the user by adjusting the flow according to the diver's requirements. The system still had to use surface supply, as the storage cylinders of the 1860s were not able to withstand the high pressures necessary for a practical self-contained unit.

The first open-circuit scuba system was devised in 1925 by Yves Le Prieur in France. Inspired by the simple apparatus of Maurice Fernez

Maurice Fernez (30 August 1885 - 31 January 1952, Alfortville, Paris, France) was a French inventor and pioneer in the field of underwater breathing apparatus, respirators and gas masks. He was pivotal in the transition of diving from the tethered ...

and the freedom it allowed the diver, he conceived an idea to make it free of the tube to the surface pump by using Michelin cylinders as the air supply, containing of air compressed to . The "Fernez-Le Prieur" diving apparatus was demonstrated at the swimming pool of Tourelles in Paris in 1926. The unit consisted of a cylinder of compressed air carried on the back of the diver, connected to a pressure regulator designed by Le Prieur adjusted manually by the diver, with two gauges, one for tank pressure and one for output (supply) pressure. Air was supplied continuously to the mouthpiece and ejected through a short exhaust pipe fitted with a valve as in the Fernez design, however, the lack of a demand regulator and the consequent low endurance of the apparatus limited the practical use of Le Prieur's device.

Le Prieur's design was the first autonomous breathing device used by the first scuba diving clubs in history - ''Racleurs de fond'' founded by Glenn Orr in California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

in 1933, and ''Club des sous-l'eau'' founded by Le Prieur himself in Paris in 1935. Fernez had previously invented the noseclip

A noseclip or nose clip is a device designed to hold the nostrils closed to prevent water from entering, or air from escaping, by people during aquatic activities such as kayaking, freediving, Pelizzari, Umberto & Tovaglieri, Stefano (2001) ''‘ ...

, a mouthpiece (equipped with a one-way valve

A check valve, non-return valve, reflux valve, retention valve, foot valve, or one-way valve is a valve that normally allows fluid ( liquid or gas) to flow through it in only one direction.

Check valves are two-port valves, meaning they have ...

for exhalation) and diving goggles

Goggles, or safety glasses, are forms of protective eyewear that usually enclose or protect the area surrounding the eye in order to prevent particulates, water or chemicals from striking the eyes. They are used in chemistry laboratories and ...

, and Yves le Prieur just joined to those three Fernez elements a hand-controlled regulator and a compressed-air cylinder. Fernez's goggles didn't allow a dive deeper than due to "mask squeeze

A mask is an object normally worn on the face, typically for protection, disguise, performance, or entertainment and often they have been employed for rituals and rights. Masks have been used since antiquity for both ceremonial and practi ...

", so, in 1933, Le Prieur replaced all the Fernez equipment (goggles, nose clip, and valve) by a full face mask

A full-face diving mask is a type of diving mask that seals the whole of the diver's face from the water and contains a mouthpiece, demand valve or constant flow gas supply that provides the diver with breathing gas. The full face mask h ...

, directly supplied with constant flow air from the cylinder.

In 1942, during the German occupation of France

The Military Administration in France (german: Militärverwaltung in Frankreich; french: Occupation de la France par l'Allemagne) was an interim occupation authority established by Nazi Germany during World War II to administer the occupied zo ...

, Jacques-Yves Cousteau

Jacques-Yves Cousteau, (, also , ; 11 June 191025 June 1997) was a French naval officer, oceanographer, filmmaker and author. He co-invented the first successful Aqua-Lung, open-circuit SCUBA ( self-contained underwater breathing apparatus). T ...

and Émile Gagnan designed the first successful and safe open-circuit scuba, known as the Aqua-Lung. Their system combined an improved demand regulator with high-pressure air tanks. Émile Gagnan, an engineer employed by the Air Liquide

Air Liquide S.A. (; ; literally "liquid air"), is a French multinational company which supplies industrial gases and services to various industries including medical, chemical and electronic manufacturers. Founded in 1902, after Linde it is ...

company, miniaturized and adapted the regulator to use with gas generator

A gas generator is a device for generating gas. A gas generator may create gas by a chemical reaction or from a solid or liquid source, when storing a pressurized gas is undesirable or impractical.

The term often refers to a device that uses a ...

s, in response to constant fuel shortage that was a consequence of German requisitioning. Gagnan's boss, Henri Melchior, knew that his son-in-law Jacques-Yves Cousteau was looking for an automatic demand regulator to increase the useful period of the underwater breathing apparatus invented by Commander le Prieur, so he introduced Cousteau to Gagnan in December 1942. On Cousteau's initiative, the Gagnan's regulator was adapted to diving, and the new Cousteau-Gagnan patent was registered some weeks later in 1943.

Air Liquide started selling the Cousteau-Gagnan regulator commercially as of 1946 under the name of ''scaphandre Cousteau-Gagnan'' or CG45 ("C" for Cousteau, "G" for Gagnan and 45 for the 1945

Air Liquide started selling the Cousteau-Gagnan regulator commercially as of 1946 under the name of ''scaphandre Cousteau-Gagnan'' or CG45 ("C" for Cousteau, "G" for Gagnan and 45 for the 1945 patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A ...

). The same year Air Liquide created a division called ''La Spirotechnique

Aqua Lung International (formerly La Spirotechnique) is a large and well-known firm which makes scuba and other self-contained breathing apparatus, and other diving equipment. It produced the Aqua-Lung line of regulators, like the CG45 (1945 ...

'', to develop and sell regulators and other diving equipment. To sell his regulator in English-speaking countries Cousteau registered the Aqua-Lung trademark, which was first licensed to the U.S. Divers company (the American division of Air Liquide) and later sold with La Spirotechnique and U.S. Divers to finally become the name of the company, Aqua-Lung/La Spirotechnique, currently located in Carros

Carros (; oc, Carròs) is a commune in the Alpes-Maritimes department in southeastern France. Carros is one of sixteen villages grouped together by the Métropole Nice Côte d'Azur tourist department as the ''Route des Villages Perchés'' (Rou ...

, near Nice

Nice ( , ; Niçard dialect, Niçard: , classical norm, or , nonstandard, ; it, Nizza ; lij, Nissa; grc, Νίκαια; la, Nicaea) is the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes departments of France, department in France. The Nice urban unit, agg ...

.

In 1948 the Cousteau-Gagnan patent was also licensed to Siebe Gorman

Siebe Gorman & Company Ltd was a British company that developed diving equipment and breathing equipment and worked on commercial diving and marine salvage projects. The company advertised itself as 'Submarine Engineers'. It was founded by Au ...

of England, when Siebe Gorman was directed by Robert Henry Davis. Siebe Gorman was allowed to sell in Commonwealth countries but had difficulty in meeting the demand and the U.S. patent prevented others from making the product. This demand was eventually met by Ted Eldred of Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

, Australia, who had been developing a rebreather called the Porpoise. When a demonstration resulted in a diver passing out, he began to develop the single-hose open-circuit scuba system, which separates the first and second stages by a low-pressure hose, and releases exhaled gas at the second stage. This avoided the Cousteau-Gagnan patent, which protected the twin-hose scuba regulator. In the process, Eldred also improved the performance of the regulator. Eldred sold the first Porpoise Model CA single hose scuba early in 1952.

In 1957, Eduard Admetlla i Lázaro used a version made by Nemrod

In 1945, Pedro and Juan Vilarrubìs Frerrando brothers found Nemrod Industrias Vilarrubìs, initially dedicated to the manufacturing of diving spearguns. The first spearguns are made with spring, with or without surcompressor followed, two years ...

to descend to a record depth of .

Early scuba sets were usually provided with a plain harness of shoulder straps and waist belt. The waist belt buckles were usually quick-release, and shoulder straps sometimes had adjustable or quick-release buckles. Many harnesses did not have a backplate, and the cylinders rested directly against the diver's back. The harnesses of many diving rebreathers made by Siebe Gorman included a large back-sheet of reinforced rubber.

Early scuba divers dived without any buoyancy aid. In an emergency, they had to jettison their weights. In the 1960s, adjustable buoyancy life jackets (ABLJ) became available. One early make, since 1961, was Fenzy

Fenzy is a scuba diving and industrial breathing equipment design and manufacturing firm. It started in or before 1920 in France. Finally Honeywell bought them out.

In 1961 the company's founder and owner, Maurice Fenzy, invented a divers' ''adjus ...

. The ABLJ is used for two purposes: to adjust the buoyancy of the diver to compensate for loss of buoyancy at depth, mainly due to compression of the neoprene wetsuit

A wetsuit is a garment worn to provide thermal protection while wet. It is usually made of foamed neoprene, and is worn by surfers, divers, windsurfers, canoeists, and others engaged in water sports and other activities in or on water. It ...

) and more importantly as a lifejacket

A personal flotation device (PFD; also referred to as a life jacket, life preserver, life belt, Mae West, life vest, life saver, cork jacket, buoyancy aid or flotation suit) is a flotation device in the form of a vest or suite that is worn by a ...

that will hold an unconscious diver face-upwards at the surface, and that can be quickly inflated. It was put on before putting on the cylinder harness. The first versions were inflated with a small carbon dioxide cylinder, later with a small direct coupled air cylinder. An extra low-pressure feed from the regulator first-stage lets the lifejacket be controlled as a buoyancy aid. This invention in 1971 of the "direct system," by ScubaPro

Johnson Outdoors Inc. () produces outdoor recreational products such as watercraft, diving equipment, camping gear, and outdoor clothing. It has operations in 24 locations worldwide, employs 1,400 people and reports sales of more than $315 millio ...

, resulted in what was called a stabilizer jacket or stab jacket, and is now increasingly known as a buoyancy compensator (device), or simply "BCD".

Closed-circuit scuba

The alternative concept, developed in roughly the same time frame was closed-circuit scuba. The body consumes and metabolises only a part of the

The alternative concept, developed in roughly the same time frame was closed-circuit scuba. The body consumes and metabolises only a part of the oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as ...

in the inhaled air at the surface, and an even smaller fraction when the breathing gas is compressed as it is in ambient pressure systems underwater. A rebreather recycles the used breathing gas, while constantly replenishing it from the supply so that the oxygen level does not get dangerously depleted. The apparatus also has to remove the exhaled carbon dioxide, as a buildup of CO2 levels would result in respiratory distress due to hypercapnia

Hypercapnia (from the Greek ''hyper'' = "above" or "too much" and ''kapnos'' = "smoke"), also known as hypercarbia and CO2 retention, is a condition of abnormally elevated carbon dioxide (CO2) levels in the blood. Carbon dioxide is a gaseous pro ...

.

The earliest known oxygen rebreather

A rebreather is a breathing apparatus that absorbs the carbon dioxide of a user's breathing, exhaled breath to permit the rebreathing (recycling) of the substantially unused oxygen content, and unused inert content when present, of each breath. ...

was patented on 17 June 1808 by ''Sieur'' Touboulic from Brest, mechanic

A mechanic is an artisan, skilled tradesperson, or technician who uses tools to build, maintain, or repair machinery, especially cars.

Duties

Most mechanics specialize in a particular field, such as auto body mechanics, air conditioning an ...

in Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's Imperial Navy, but there is no evidence of any prototype having been manufactured. This early rebreather design worked with an oxygen reservoir, the oxygen being delivered progressively by the diver himself and circulating in a closed circuit through a sponge

Sponges, the members of the phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), are a basal animal clade as a sister of the diploblasts. They are multicellular organisms that have bodies full of pores and channels allowing water to circulate throug ...

soaked in limewater. The earliest practical rebreather relates to the 1849 patent from the Frenchman Pierre Aimable De Saint Simon Sicard.

The first commercially practical closed-circuit scuba was designed and built by the diving engineer Henry Fleuss

Henry Albert Fleuss (13 June 1851 – 6 January 1933) was a pioneering diving engineer, and Master Diver for Siebe, Gorman & Co. of London.

Fleuss was born in Marlborough, Wiltshire in 1851.

In 1878 he was granted a patent which improved rebr ...

in 1878, while working for Siebe Gorman in London. His apparatus consisted of a rubber mask connected by a tube to a bag, with (estimated) 50–60% O2 supplied from a copper pressure tank and CO2 chemically absorbed by rope yarn in the bag soaked in a solution of caustic potash. The system allowed use for about three hours. Fleuss tested his device in 1879 by spending an hour submerged in a water tank, then one week later by diving to a depth of in open water, upon which occasion he was slightly injured when his assistants abruptly pulled him to the surface. The Fleuss apparatus was first used under operational conditions in 1880 by the lead diver on the Severn Tunnel

The Severn Tunnel ( cy, Twnnel Hafren) is a railway tunnel in the United Kingdom, linking South Gloucestershire in the west of England to Monmouthshire in south Wales under the estuary of the River Severn. It was constructed by the Great Western ...

construction project Alexander Lambert

Alexander Lambert (November 1, 1863 – December 31, 1929) was a pianist and a piano teacher.

Biography

He was born on November 1, 1863, in Warsaw, Poland, to Henry Lambert.

He graduated from the Vienna Conservatory of Music in 1878.

, who was able to travel in the darkness to close several submerged sluice doors in the tunnel; this had defeated the best efforts of hard hat divers due to the danger of their air supply hoses becoming fouled on submerged debris, and the strong water currents in the workings. Fleuss continually improved his apparatus, adding a demand regulator and tanks capable of holding greater amounts of oxygen at higher pressure.

Sir Robert Davis, head of Siebe Gorman, improved the oxygen rebreather in 1910 with his invention of the Davis Submerged Escape Apparatus

The Davis Submerged Escape Apparatus (also referred to as DSEA), was an early type of oxygen rebreather invented in 1910 by Sir Robert Davis, head of Siebe Gorman and Co. Ltd., inspired by the earlier Fleuss system, and adopted by the Royal Na ...

, the first rebreather to be made in quantity. While intended primarily as an emergency escape apparatus for submarine crews, it was soon also used for diving, being a handy shallow water diving apparatus with a thirty-minute endurance, and as an industrial breathing set

A self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA), sometimes referred to as a compressed air breathing apparatus (CABA) or simply breathing apparatus (BA), is a device worn to provide breathable air in an atmosphere that is immediately dangerous to ...

. The Davis apparatus comprised a rubber breathing bag containing a canister of barium hydroxide

Barium hydroxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula Ba(OH)2. The monohydrate (''x'' = 1), known as baryta or baryta-water, is one of the principal compounds of barium. This white granular monohydrate is the usual commercial form.

...

to scrub exhaled carbon dioxide and a steel cylinder holding approximately of oxygen at a pressure of , with a valve to allow the user to add oxygen to the bag. The set also included an emergency buoyancy bag on the front of to help keep the wearer afloat. The DSEA was adopted by the Royal Navy after further development by Davis in 1927.