History of the United States Merchant Marine on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The maritime history of the United States is a broad theme within the history of the United States. As an academic subject, it crosses the boundaries of standard disciplines, focusing on understanding the United States' relationship with the oceans, seas, and major waterways of the globe. The focus is on merchant shipping, and the financing and manning of the ships. A merchant marine owned at home is not essential to an extensive foreign commerce. In fact, it may be cheaper to hire other nations to handle the carrying trade than to participate in it directly. On the other hand, there are certain advantages, particularly during time of war, which may warrant an aggressive government encouragement to the maintenance of a merchant marine.

In 1785, the ''

In 1785, the ''

In 1790, federal legislation was enacted pertaining to seamen and desertion. In 1796, federal legislation regarding Seaman's Protection Certificates (also known as Protection papers) was enacted. Immediately after the Revolutionary War the brand-new

In 1790, federal legislation was enacted pertaining to seamen and desertion. In 1796, federal legislation regarding Seaman's Protection Certificates (also known as Protection papers) was enacted. Immediately after the Revolutionary War the brand-new

During the wars with France (1793 to 1815) the Royal Navy aggressively reclaimed British deserters on board ships of other nations, both by halting and searching merchant ships, and in many cases, by searching American port cities. The Royal Navy did not recognize naturalized American citizenship, treating anyone born a British subject as "British" — as a result, the Royal Navy impressed over 6,000 sailors who were claimed as American citizens as well as British subjects. This was one of the major factors leading to the

During the wars with France (1793 to 1815) the Royal Navy aggressively reclaimed British deserters on board ships of other nations, both by halting and searching merchant ships, and in many cases, by searching American port cities. The Royal Navy did not recognize naturalized American citizenship, treating anyone born a British subject as "British" — as a result, the Royal Navy impressed over 6,000 sailors who were claimed as American citizens as well as British subjects. This was one of the major factors leading to the

Clippers were built for seasonal trades such as tea, where an early cargo was more valuable, or for passenger routes. The small, fast ships were ideally suited to low-volume, high-profit goods, such as

Clippers were built for seasonal trades such as tea, where an early cargo was more valuable, or for passenger routes. The small, fast ships were ideally suited to low-volume, high-profit goods, such as

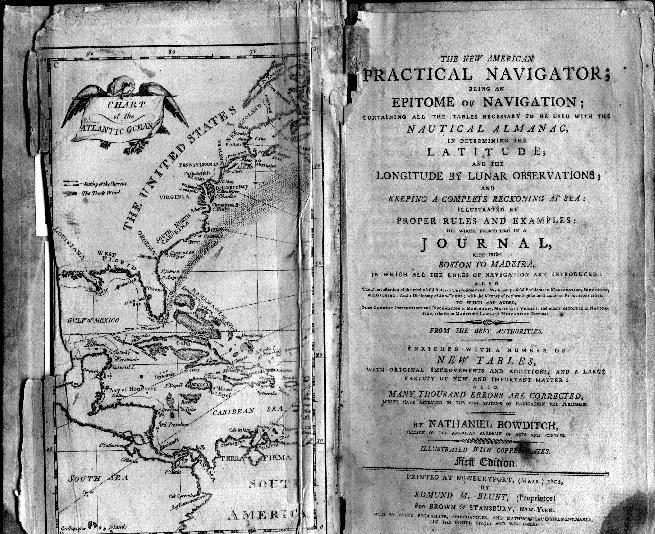

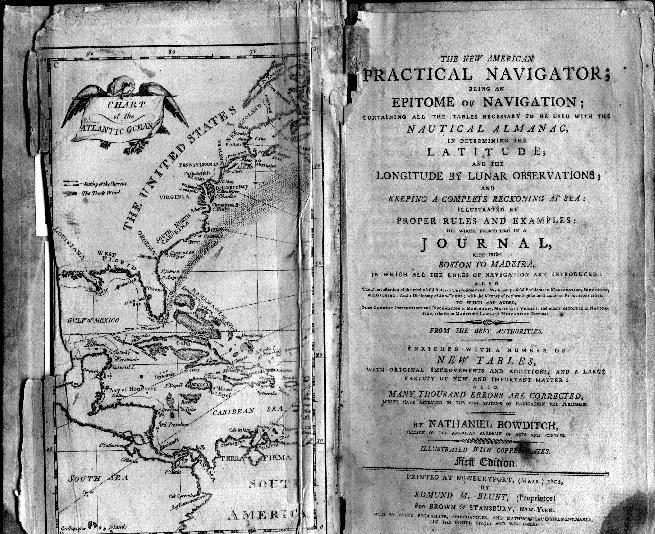

In 1832,

In 1832,

A long, dangerous coastline : shipwreck tales from Alaska to California

Heritage House Publishing Company, 1 Feb 2011 - 128 pages The Sailors' Union of the Pacific (SUP) founded on March 6, 1885, in

In 1905, the

In 1905, the

. In 1915, the Seamen's Act of 1915 became law. The act fundamentally changed the life of the American sailor. Among other things, it:

#abolished the practice of imprisonment for seamen who deserted their ship

#reduced the penalties for disobedience

#regulated a seaman's working hours both at sea and in port

#established a minimum quality for ship's food

#regulated the payment of seamen's wages

#required specific levels of safety, particularly the provision of

. In 1915, the Seamen's Act of 1915 became law. The act fundamentally changed the life of the American sailor. Among other things, it:

#abolished the practice of imprisonment for seamen who deserted their ship

#reduced the penalties for disobedience

#regulated a seaman's working hours both at sea and in port

#established a minimum quality for ship's food

#regulated the payment of seamen's wages

#required specific levels of safety, particularly the provision of

All of these new ships needed trained officers and crews to operate them. The Coast Guard provided much of the advanced training for merchant marine personnel to augment the training of state merchant marine academies. The Maritime Commission requested that the Coast Guard provide training in 1938 when the Maritime Service was created. Merchant sailors from around the country trained at two large training stations. On the East Coast the sailors trained at

All of these new ships needed trained officers and crews to operate them. The Coast Guard provided much of the advanced training for merchant marine personnel to augment the training of state merchant marine academies. The Maritime Commission requested that the Coast Guard provide training in 1938 when the Maritime Service was created. Merchant sailors from around the country trained at two large training stations. On the East Coast the sailors trained at  Once convoys and air cover were introduced, sinking numbers were reduced and the U-boats shifted to attack shipping in the

Once convoys and air cover were introduced, sinking numbers were reduced and the U-boats shifted to attack shipping in the

The biggest supporter of the merchant sailors was President

The biggest supporter of the merchant sailors was President

The Maritime Commission, U.S. Maritime Commission was abolished on 24 May 1950, its functions were split between the U.S. Federal Maritime Board which was responsible for regulating shipping and awarding subsidies for construction and operation of merchant vessels, and Maritime Administration, which was responsible for administering subsidy programs, maintaining the national defense reserve merchant fleet, and operating the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy. AMO was chartered on May 12, 1949, as the Brotherhood of Marine Engineers by Paul Hall (labor leader), Paul Hall as an affiliate of the Seafarers International Union of North America, Seafarer's International Union of North America. The original membership consisted entirely of civilian seafaring veterans of World War II.

The Maritime Commission, U.S. Maritime Commission was abolished on 24 May 1950, its functions were split between the U.S. Federal Maritime Board which was responsible for regulating shipping and awarding subsidies for construction and operation of merchant vessels, and Maritime Administration, which was responsible for administering subsidy programs, maintaining the national defense reserve merchant fleet, and operating the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy. AMO was chartered on May 12, 1949, as the Brotherhood of Marine Engineers by Paul Hall (labor leader), Paul Hall as an affiliate of the Seafarers International Union of North America, Seafarer's International Union of North America. The original membership consisted entirely of civilian seafaring veterans of World War II.

On March 13, 1951, the Secretary of Commerce established the National Shipping Authority (NSA) to provide ships from the United States Maritime Administration, Maritime Administration's (MARAD) National Defense Fleet (NDRF). These ships would meet the needs of the military services and other agencies of government beyond the capabilities of the privately owned vessels of the U.S.-flag Merchant Marine. During times of war, the NSA also requisitioned privately owned merchant ships and made them available for military purposes. Immediately after its establishment, the NSA reactivated vessels to meet the urgent needs of America's European allies to help transport coal and other bulk materials to rebuild their defenses.

During the Korean War there were few severe sealift problems other than the need to re-mobilize forces following post–World War II demobilization. About 700 ships were activated from the NDRF for services to the Far East. In addition, a worldwide tonnage shortfall between 1951 and 1953 required the reactivation of over 600 ships to lift coal to Northern Europe and grain to India during the first years of the Cold War. The commercial merchant marine formed the backbone of the bridge of ships across the Pacific. From just six ships under charter when the war began, this total peaked at 255. According to the Military Sealift Command, Military Sea Transportation Service (MSTS), 85 percent of the dry cargo requirements during the Korean War were met through commercial vessels — only five percent were shipped by air. More than $475 million, or 75 percent of the MSTS operating budget for calendar year 1952, was paid directly to commercial shipping interests.

In addition to the ships assigned directly to MSTS, 130 laid-up Victory ships in the NDRF were broken out by the Maritime Administration and assigned under time-charters to private shipping firms for charter to MSTS.

Ships of the MSTS not only provided supplies but also served as naval auxiliaries. When the United States Army, U.S. Army's X Corps (United States), X Corps Battle of Inchon, went ashore at Inchon in September 1950, 13 USNS cargo ships, 26 chartered American, and 34 Japanese-crewed merchant ships, under the operational control of MSTS, participated in the invasion. Sealift responsibilities were accomplished on short notice during the Korean War. Initially American troops lacked the vital equipment to fight the North Koreans, but military and commercial vessels quickly began delivering the fighting tools needed to turn back the enemy. According to the MSTS, 7 tons of supplies were needed for every Marine or soldier bound for Korea and an additional one for each month thereafter. Cargo ships unloaded supplies around the clock, making Pusan a bustling port. The success of the U.S. Merchant Marine during this crisis hammered home to critics the importance of maritime preparedness and the folly of efforts to scuttle the Merchant Marine fleet. In addition to delivering equipment to American forces — more than 90 percent of all American and other United Nations’ troops — supplies and equipment were delivered to Korea through the MSTS with the assistance of commercial cargo vessels. A bridge of ships, much like in World War II, spanned the Pacific Ocean during the three years of hostilities.

Merchant ships played an important role in the evacuation of United Nations troops from Hungnam, following the Chosin Reservoir Campaign. The Merchant Marine and Navy evacuated over 100,000 U.N. troops and another 91,000 Korean refugees and moved 350,000 tons of cargo and 17,500 vehicles in less than two weeks. One of the most famous rescues was performed by the U.S. merchant ship SS Meredith Victory, SS ''Meredith Victory''. Only hours before the advancing communists drove the U.N. forces from North Korea in December 1950, the vessel, built to accommodate 12 passengers, carried more than 14,000 Korean civilians from Hungnam to Pusan in the south. First mate D. S. Savastio, with nothing but first aid training, delivered five babies during the three-day passage to Pusan. Ten years later, the Maritime Administration honored the crew by awarding them a Gallant Ship Award.

Privately owned American merchant ships helped deploy thousands of U.S. troops and their equipment, bringing high praise from the commander of U.S. Naval Forces in the Far East, Admiral C. Turner Joy, Charles T. Joy. In congratulating Navy Captain A.F. Junker, Commander of the Military Sea Transportation Service for the western Pacific, Admiral Joy noted that the success of the Korean campaign was dependent on the Merchant Marine. He said, "The Merchant Mariners in your command performed silently, but their accomplishments speak loudly. Such teammates are comforting to work with."

Government owned merchant vessels from the National Defense Reserve Fleet (NDRF) have supported emergency shipping requirements in seven wars and crises. During the Korean War, 540 vessels were activated to support military forces. From 1955 through 1964, another 600 ships were used to store grain for the United States Department of Agriculture, Department of Agriculture. Another tonnage shortfall following the Suez Canal closing in 1956 caused 223 cargo ship and 29 tanker activations from the NDRF.

On March 13, 1951, the Secretary of Commerce established the National Shipping Authority (NSA) to provide ships from the United States Maritime Administration, Maritime Administration's (MARAD) National Defense Fleet (NDRF). These ships would meet the needs of the military services and other agencies of government beyond the capabilities of the privately owned vessels of the U.S.-flag Merchant Marine. During times of war, the NSA also requisitioned privately owned merchant ships and made them available for military purposes. Immediately after its establishment, the NSA reactivated vessels to meet the urgent needs of America's European allies to help transport coal and other bulk materials to rebuild their defenses.

During the Korean War there were few severe sealift problems other than the need to re-mobilize forces following post–World War II demobilization. About 700 ships were activated from the NDRF for services to the Far East. In addition, a worldwide tonnage shortfall between 1951 and 1953 required the reactivation of over 600 ships to lift coal to Northern Europe and grain to India during the first years of the Cold War. The commercial merchant marine formed the backbone of the bridge of ships across the Pacific. From just six ships under charter when the war began, this total peaked at 255. According to the Military Sealift Command, Military Sea Transportation Service (MSTS), 85 percent of the dry cargo requirements during the Korean War were met through commercial vessels — only five percent were shipped by air. More than $475 million, or 75 percent of the MSTS operating budget for calendar year 1952, was paid directly to commercial shipping interests.

In addition to the ships assigned directly to MSTS, 130 laid-up Victory ships in the NDRF were broken out by the Maritime Administration and assigned under time-charters to private shipping firms for charter to MSTS.

Ships of the MSTS not only provided supplies but also served as naval auxiliaries. When the United States Army, U.S. Army's X Corps (United States), X Corps Battle of Inchon, went ashore at Inchon in September 1950, 13 USNS cargo ships, 26 chartered American, and 34 Japanese-crewed merchant ships, under the operational control of MSTS, participated in the invasion. Sealift responsibilities were accomplished on short notice during the Korean War. Initially American troops lacked the vital equipment to fight the North Koreans, but military and commercial vessels quickly began delivering the fighting tools needed to turn back the enemy. According to the MSTS, 7 tons of supplies were needed for every Marine or soldier bound for Korea and an additional one for each month thereafter. Cargo ships unloaded supplies around the clock, making Pusan a bustling port. The success of the U.S. Merchant Marine during this crisis hammered home to critics the importance of maritime preparedness and the folly of efforts to scuttle the Merchant Marine fleet. In addition to delivering equipment to American forces — more than 90 percent of all American and other United Nations’ troops — supplies and equipment were delivered to Korea through the MSTS with the assistance of commercial cargo vessels. A bridge of ships, much like in World War II, spanned the Pacific Ocean during the three years of hostilities.

Merchant ships played an important role in the evacuation of United Nations troops from Hungnam, following the Chosin Reservoir Campaign. The Merchant Marine and Navy evacuated over 100,000 U.N. troops and another 91,000 Korean refugees and moved 350,000 tons of cargo and 17,500 vehicles in less than two weeks. One of the most famous rescues was performed by the U.S. merchant ship SS Meredith Victory, SS ''Meredith Victory''. Only hours before the advancing communists drove the U.N. forces from North Korea in December 1950, the vessel, built to accommodate 12 passengers, carried more than 14,000 Korean civilians from Hungnam to Pusan in the south. First mate D. S. Savastio, with nothing but first aid training, delivered five babies during the three-day passage to Pusan. Ten years later, the Maritime Administration honored the crew by awarding them a Gallant Ship Award.

Privately owned American merchant ships helped deploy thousands of U.S. troops and their equipment, bringing high praise from the commander of U.S. Naval Forces in the Far East, Admiral C. Turner Joy, Charles T. Joy. In congratulating Navy Captain A.F. Junker, Commander of the Military Sea Transportation Service for the western Pacific, Admiral Joy noted that the success of the Korean campaign was dependent on the Merchant Marine. He said, "The Merchant Mariners in your command performed silently, but their accomplishments speak loudly. Such teammates are comforting to work with."

Government owned merchant vessels from the National Defense Reserve Fleet (NDRF) have supported emergency shipping requirements in seven wars and crises. During the Korean War, 540 vessels were activated to support military forces. From 1955 through 1964, another 600 ships were used to store grain for the United States Department of Agriculture, Department of Agriculture. Another tonnage shortfall following the Suez Canal closing in 1956 caused 223 cargo ship and 29 tanker activations from the NDRF.

During the Vietnam War, ships crewed by civilian seamen carried 95 percent of the supplies used by our Armed Forces. Many of these ships sailed into combat zones under fire. In fact, the Mayagüez incident, SS ''Mayaguez'' incident involved the capture of mariners from the American merchant ship SS Mayaguez. The crisis began on May 12, 1975, when Khmer Rouge naval forces operating former U.S. Navy "Fast Patrol Craft, Swift Boats" seized the American container ship SS Mayagüez, SS ''Mayagüez'' in recognized international sea lanes claimed as territorial waters by Cambodia and removed its crew for questioning. Surveillance by P-3 Orion aircraft indicated that the ship was then moved to and anchored at Koh Tang, an island approximately off the southern coast of Cambodia near that country's shared border with Vietnam. Tragically, the ship's crew whose seizure had prompted the US attack had been released in good health, unknown to the United States Marine Corps, US Marines or the US command of the operation, before the Marines attacked. The incident marked the last official battle of the United States involvement in the Vietnam War.

During the Vietnam War, ships crewed by civilian seamen carried 95 percent of the supplies used by our Armed Forces. Many of these ships sailed into combat zones under fire. In fact, the Mayagüez incident, SS ''Mayaguez'' incident involved the capture of mariners from the American merchant ship SS Mayaguez. The crisis began on May 12, 1975, when Khmer Rouge naval forces operating former U.S. Navy "Fast Patrol Craft, Swift Boats" seized the American container ship SS Mayagüez, SS ''Mayagüez'' in recognized international sea lanes claimed as territorial waters by Cambodia and removed its crew for questioning. Surveillance by P-3 Orion aircraft indicated that the ship was then moved to and anchored at Koh Tang, an island approximately off the southern coast of Cambodia near that country's shared border with Vietnam. Tragically, the ship's crew whose seizure had prompted the US attack had been released in good health, unknown to the United States Marine Corps, US Marines or the US command of the operation, before the Marines attacked. The incident marked the last official battle of the United States involvement in the Vietnam War.

online

* * * * * * * *

American Merchant Marine at WarUnited States Merchant Marine in historySeafarers International Union - War's Forgotten Heroes

(lyrics only)

Fairplay The International Shipping WeeklyThe Nautical Institute

HR23 Bill Merchant Marine veteran benefits

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of The United States Merchant Marine Maritime history of the United States, History of the United States by topic United States Merchant Marine

History

Early history

The maritime history of the United States goes back to the first successful English colony was established in 1607, on the James River at Jamestown. It languished for decades until a new wave of settlers arrived in the late 17th century and set up commercial agriculture based on exports of tobacco to England. Settlers brought horses, cattle, sheep and hogs as well as tools and the current technology to the Americas. From the very first days of the founding of the North American colonies shipbuilding was naturally one of the industries that chiefly engaged the attention of the colonists. At the time of the breaking out of the American Revolution and for a long time afterwards more of the people in New England were actually engaged in shipbuilding and ship sailing than in agriculture, even in spite of the restrictions imposed on the building of ships in the English colonies. The statement is made that at one time during this period Massachusetts was estimated to have one vessel for every hundred of its inhabitants. One out of every four signers of the Declaration of Independence was a shipowner or had been a ship captain.The 18th century

As British colonists before 1776, American merchant vessels had enjoyed the protection of theRoyal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

. Major ports in the Northeast began to specialize in merchant shipping. The main cargoes included tobacco, as well as rice, indigo and naval stores from the Southern colonies. From the other colonies exports included horses, wheat, fish and lumber. By the 1760s New England was the center of a flourishing shipbuilding industry. Imports included all manner of manufactured goods.

Revolutionary War

The first war that an organized United States Merchant Marine took part in was theAmerican Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, which lasted from 1775 to 1783. In 1775 the Continental Congress and the various colonies issued Letters of Marque to privately owned, armed merchant ships known as privateers, which were outfitted as warships to prey on enemy merchant ships. They interrupted the British supply chain all along the eastern seaboard of the United States and across the Atlantic Ocean and the Merchant Marine's role in war began. This predates both the United States Coast Guard

The United States Coast Guard (USCG) is the maritime security, search and rescue, and law enforcement service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the country's eight uniformed services. The service is a maritime, military, mu ...

(1790) and the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

(1797). During the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

, American ships came under the aegis of France due to a 1778 Treaty of Alliance between the two countries.See First Barbary War

The First Barbary War (1801–1805), also known as the Tripolitan War and the Barbary Coast War, was a conflict during the Barbary Wars, in which the United States and Sweden fought against Tripolitania. Tripolitania had declared war against Sw ...

.

1783–1790

By 1783, however, with the end of the Revolution, America became solely responsible for the safety of its own commerce and citizens. Without the means or the authority to field a naval force necessary to protect their ships in the Mediterranean against theBarbary pirate

The Barbary pirates, or Barbary corsairs or Ottoman corsairs, were Muslim pirates and privateers who operated from North Africa, based primarily in the ports of Salé, Rabat, Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli. This area was known in Europe ...

s, the nascent U.S. government took a pragmatic, but ultimately self-destructive route. In 1784, the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

allocated money for payment of tribute to the pirates.

Also in 1784, Boston navigators sailed to the Pacific Northwest and opened the U.S. fur trade.

In 1785, the ''

In 1785, the ''Dey

Dey (Arabic: داي), from the Turkish honorific title ''dayı'', literally meaning uncle, was the title given to the rulers of the Regency of Algiers (Algeria), Tripoli,Bertarelli (1929), p. 203. and Tunis under the Ottoman Empire from 1671 o ...

'' of Algiers took two American ships hostage and demanded US$60,000 in ransom for their crews. Then-ambassador to France Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

argued that conceding the ransom would only encourage more attacks. His objections fell on the deaf ears of an inexperienced American government too riven with domestic discord to make a strong show of force overseas. The U.S. paid Algiers the ransom, and continued to pay up to $1 million per year over the next 15 years for the safe passage of American ships or the return of American hostages. Payments in ransom and tribute to the privateering states amounted to 20 percent of United States government annual revenues in 1800.

Jefferson continued to argue for cessation of the tribute, with rising support from George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

and others. With the recommissioning of the American navy in 1794 and the resulting increased firepower on the seas, it became more and more possible for America to say "no", although by now the long-standing habit of tribute was hard to overturn. A largely successful undeclared war

An undeclared war is a military conflict between two or more nations without either side issuing a formal declaration of war. The term is sometimes used to include any disagreement or conflict fought about without an official declaration. Since ...

with French privateers in the late 1790s showed that American naval power was now sufficient to protect the nation's interests on the seas. These tensions led to the First Barbary War

The First Barbary War (1801–1805), also known as the Tripolitan War and the Barbary Coast War, was a conflict during the Barbary Wars, in which the United States and Sweden fought against Tripolitania. Tripolitania had declared war against Sw ...

in 1801.

The only clause in the treaty of peace (1783) concerning commerce was a stipulation guaranteeing that the navigation of the Mississippi should be forever free to the United States. John Jay at this time had tried to secure some reciprocal trade provisions with Great Britain, but without result. Pitt in 1783 introduced a bill into the British Parliament providing for free trade between the United States and the British colonies, but instead of passing this bill Parliament enacted the British Navigation Act of 1783 which admitted only British-built ships and crewed ships to the ports of the West Indies and imposed heavy tonnage dues upon American ships in other British ports. This was amplified in 1786 by another act designed to prevent the fraudulent registration of American vessels, and by still another in 1787 which prohibited the importation of American goods by way of foreign islands. The favorable features of the old Navigation Acts which had granted bounties and reserved the English markets in certain cases to colonial products were gone; the unfavorable alone were left. The British market was further curtailed by the depression there after 1783. Although the French treaty of 1778 had promised "perfect equality and reciprocity" in commercial relations, it was found impossible to make a commercial treaty upon this basis. Spain demanded as her price for reciprocal trading relations that the United States surrender for twenty-five years the right of navigating the Mississippi, a price which the New England merchants would have been glad to pay. France (1778) and the Dutch Republic (1782) made treaties, but not on even terms; Portugal refused the U.S. advances. Only Sweden (1783) and Prussia (1785) made treaties guaranteeing reciprocal commercial privileges.Harold Underwood Faulkner, American Economic History, Harper & Brothers, 1938, p. 182

The weakness of Congress under the Articles of Confederation prevented retaliation by the central government. Power was repeatedly asked to regulate commerce, but was refused by the states, upon whom rested the carrying out of such commercial treaties as Congress might negotiate. Eventually the states themselves attempted retaliatory measures, and during the years 1783–88, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia levied tonnage dues upon British vessels or discriminating tariffs upon British goods. Whatever effect these efforts might have had were neutralized by the fact that the duties were not uniform, varying in different states from no tariffs whatever to duties of 100 percent. This simply drove British ships to the free or cheapest ports and their goods continued to flood the market. Commercial war between the states followed and turned futility into chaos.

The effect of this trade policy upon American shipping was detrimental. After the passage of the U.S. Constitution in 1789 the congress was petitioned for relief. On June 5, 1789, a petition from the tradesmen and manufacturers of Boston was sent to the Congress which stated "that the great decrease of American manufactures, and almost total stagnation of American ship-building, urge us to apply to the sovereign Legislature of these States for their assistance to promote these important branches, so essential to our national wealth and prosperity. It is with regret we observe the resources of this country exhausted for foreign luxuries, our wealth expended for various articles which could be manufactured among ourselves, and our navigation subject to the most severe restrictions in many foreign ports, whereby the extensive branch of American ship-building is essentially injured, and a numerous body of citizens, who were formerly employed in its various departments, deprived of their support and dependence.... "

" The congress responded with passage of the Tariff of 1789 which established tonnage rates favorable to American carriers by charging them lower cargo fees than those imposed on foreign boats importing similar goods. Coastal trade was reserved exclusively for American flag vessels.

In 1789, when the Constitution was adopted, the registered tonnage of the United States engaged in foreign trade was 123,893. During the next succeeding eight years it increased 384 percent.

I

The 1790s

In 1790, federal legislation was enacted pertaining to seamen and desertion. In 1796, federal legislation regarding Seaman's Protection Certificates (also known as Protection papers) was enacted. Immediately after the Revolutionary War the brand-new

In 1790, federal legislation was enacted pertaining to seamen and desertion. In 1796, federal legislation regarding Seaman's Protection Certificates (also known as Protection papers) was enacted. Immediately after the Revolutionary War the brand-new United States of America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territo ...

was struggling to stay financially afloat. National income was desperately needed and a great deal of this income came from import tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and pol ...

s. Because of rampant smuggling, the need was immediate for strong enforcement of tariff laws, and on August 4, 1790, the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

, urged on by Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

Alexander Hamilton, created the Revenue-Marine, later renamed Revenue Cutter Service in 1862. It would be the responsibility of the new Revenue-Marine to enforce the tariff and all other maritime laws.

Although tangential to American maritime history, 1799 saw the fall of a colossus of the world's maritime history. The Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

, established on March 20, 1602, when the Estates-General of the Netherlands granted it a 21-year monopoly to carry out colonial activities in Asia, formerly the world's largest company, became bankrupt, partly due to the rise of competitive free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

.

The 19th century

During the wars with France (1793 to 1815) the Royal Navy aggressively reclaimed British deserters on board ships of other nations, both by halting and searching merchant ships, and in many cases, by searching American port cities. The Royal Navy did not recognize naturalized American citizenship, treating anyone born a British subject as "British" — as a result, the Royal Navy impressed over 6,000 sailors who were claimed as American citizens as well as British subjects. This was one of the major factors leading to the

During the wars with France (1793 to 1815) the Royal Navy aggressively reclaimed British deserters on board ships of other nations, both by halting and searching merchant ships, and in many cases, by searching American port cities. The Royal Navy did not recognize naturalized American citizenship, treating anyone born a British subject as "British" — as a result, the Royal Navy impressed over 6,000 sailors who were claimed as American citizens as well as British subjects. This was one of the major factors leading to the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

in North America.

Commercial whaling

Whaling is the process of hunting of whales for their usable products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that became increasingly important in the Industrial Revolution.

It was practiced as an organized industr ...

in the United States was the center of the world whaling industry during the 18th and 19th centuries and was most responsible for the severe depletion of a number of whale species. New Bedford, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

and Nantucket Island

Nantucket () is an island about south from Cape Cod. Together with the small islands of Tuckernuck and Muskeget, it constitutes the Town and County of Nantucket, a combined county/town government that is part of the U.S. state of Massachuse ...

were the primary whaling centers in the 19th century. In 1857, New Bedford had 329 registered whaling ships.

Robert Fulton

Robert Fulton (November 14, 1765 – February 24, 1815) was an American engineer and inventor who is widely credited with developing the world's first commercially successful steamboat, the (also known as ''Clermont''). In 1807, that steamboa ...

ordered a Boulton and Watt

The watt (symbol: W) is the unit of power or radiant flux in the International System of Units (SI), equal to 1 joule per second or 1 kg⋅m2⋅s−3. It is used to quantify the rate of energy transfer. The watt is named after James ...

steam engine, and built what he called the ''North River Steamboat'' (often mistakenly described as the ''Clermont'' ). In 1807 this steamboat began a regular passenger boat service between New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

and Albany, New York

Albany ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of New York, also the seat and largest city of Albany County. Albany is on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River, and about north of New York C ...

, distant, which was a commercial success. In 1808 John and James Winans built ''Vermont'' in Burlington, Vermont, the second steamboat to operate commercially. In 1809, ''Accommodation'', built by the Hon. John Molson

John Molson (December 28, 1763 – January 11, 1836) was an English-born brewer and entrepreneur in colonial Quebec, which during his lifetime became Lower Canada. In addition to founding Molson Brewery, he built the first steamship and the fir ...

at Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple ...

, and fitted with engines made in that city, was running successfully between Montreal and Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

, being the first steamer on the St. Lawrence

Saint Lawrence or Laurence ( la, Laurentius, lit. " laurelled"; 31 December AD 225 – 10 August 258) was one of the seven deacons of the city of Rome under Pope Sixtus II who were martyred in the persecution of the Christians that the Roma ...

and in Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

. The experience of both vessels showed that the new system of propulsion was commercially viable, and as a result its application to the more open waters of the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lak ...

was next considered. That idea went on hiatus, due to the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

, however.

As a result of rising tensions with Great Britain, a number of laws collectively known as the Embargo Act of 1807

The Embargo Act of 1807 was a general trade embargo on all foreign nations that was enacted by the United States Congress. As a successor or replacement law for the 1806 Non-importation Act and passed as the Napoleonic Wars continued, it repr ...

were enacted. Britain and France were at war; the U.S. was neutral and trading with both sides. Both sides tried to hinder American trade with the other. Jefferson's goal was to use economic warfare to secure American rights, instead of military warfare. Initially, these acts sought to punish Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

for its violation of American rights on the high seas; among these was the impressment

Impressment, colloquially "the press" or the "press gang", is the taking of men into a military or naval force by compulsion, with or without notice. European navies of several nations used forced recruitment by various means. The large size of ...

of those sailors off American ships, sailors who claimed to be American citizens but not in the opinion or to the satisfaction of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

, ever on the outlook for deserters. The later Embargo Acts, particularly those of 1807–1808 period, were passed in an attempt to stop Americans, and American communities, that sought to, or were merely suspected of possibility wanting to, defy the embargo. These Acts were ultimately repealed at the end of Jefferson's second, and last, term. A modified version of these Acts would return for a brief time in 1813 under the presidential administration of Jefferson's successor, James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for h ...

.

The African slave trade became illegal on January 1, 1808.

By 1807 the tonnage registered in the United States engaged in foreign trade had increased to 848,307.

The War of 1812

The United States declared war on Britain on June 18, 1812, for a combination of reasons—outrage at the impressment (seizure) of thousands of American sailors, frustration at British restrictions on neutral trade while Britain warred withFrance

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, and anger at British military support for hostile tribes in the Ohio-Indiana-Michigan area. After war was declared Britain offered to withdraw the trade restrictions, but it was too late for the American "War Hawks", who turned the conflict into what they called a "second war for independence." Part of the American strategy was deploying several hundred privateers to attack British merchant ships, which hurt British commercial interests, especially in the West Indies.

Clipper ships

In theUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

the term "clipper" referred to the Baltimore clipper

A Baltimore Clipper is a fast sailing ship historically built on the mid-Atlantic seaboard of the United States of America, especially at the port of Baltimore, Maryland. An early form of clipper, the name is most commonly applied to two-maste ...

, a type of topsail schooner that was developed in Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the Eastern Shore of Maryland / ...

before the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

and was lightly armed in the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

, sailing under Letters of Marque and Reprisal, when the type—exemplified by the ''Chasseur'', launched at Fells Point, Baltimore

Fell's Point is a historic waterfront neighborhood in southeastern Baltimore, Maryland. It was established around 1763 along the north shore of the Baltimore Harbor and the Northwest Branch of the Patapsco River. The area has many antique, musi ...

, 1814— became known for its incredible speed; a deep draft enabled the Baltimore clipper to sail close to the wind (Villiers 1973). Clippers, outrunning the British blockade of Baltimore, came to be recognized as ships built for speed rather than cargo space; while traditional merchant ships were accustomed to average speeds of under 5 knots (9 km/h), clippers aimed at 9 knots (17 km/h) or better. Sometimes these ships could reach 20 knots (37 km/h).

Clippers were built for seasonal trades such as tea, where an early cargo was more valuable, or for passenger routes. The small, fast ships were ideally suited to low-volume, high-profit goods, such as

Clippers were built for seasonal trades such as tea, where an early cargo was more valuable, or for passenger routes. The small, fast ships were ideally suited to low-volume, high-profit goods, such as spice

A spice is a seed, fruit, root, bark, or other plant substance primarily used for flavoring or coloring food. Spices are distinguished from herbs, which are the leaves, flowers, or stems of plants used for flavoring or as a garnish. Spice ...

s, tea

Tea is an aromatic beverage prepared by pouring hot or boiling water over cured or fresh leaves of ''Camellia sinensis'', an evergreen shrub native to East Asia which probably originated in the borderlands of southwestern China and north ...

, people, and mail. The values could be spectacular. The ''Challenger'' returned from Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flowin ...

with "the most valuable cargo of tea and silk ever to be laden in one bottom." The competition among the clippers was public and fierce, with their times recorded in the newspapers. The ships had low expected lifetimes and rarely outlasted two decades of use before they were broken up for salvage. Given their speed and maneuverability, clippers frequently mounted cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

or carronade and were often employed as pirate vessels, privateers, smuggling vessels, and in interdiction service.

1815–1830

During the 18th century, ships carrying cargo, passengers and mail between Europe and America would sail only when they were full, but in the early 19th century, as trade with America became more common, schedule regularity became a valuable service. Starting in 1818, ships of the Black Ball Line began regularly scheduled trips between Britain and America. These "packet ship

Packet boats were medium-sized boats designed for domestic mail, passenger, and freight transportation in European countries and in North American rivers and canals, some of them steam driven. They were used extensively during the 18th and 19th ...

s" (named for their delivery of mail "packets") were infamous for keeping to their disciplined schedules. This often involved harsh treatment of seamen and earned the ships the nickname "bloodboat". During the 1820s American whalers start flocking to the Pacific, resulting in more contact with the Hawaiian Islands.

Because of the influence of whaling

Whaling is the process of hunting of whales for their usable products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that became increasingly important in the Industrial Revolution.

It was practiced as an organized industr ...

and several local drought

A drought is defined as drier than normal conditions.Douville, H., K. Raghavan, J. Renwick, R.P. Allan, P.A. Arias, M. Barlow, R. Cerezo-Mota, A. Cherchi, T.Y. Gan, J. Gergis, D. Jiang, A. Khan, W. Pokam Mba, D. Rosenfeld, J. Tierney, an ...

s, there was substantial migration from Cape Verde to America, most notably to New Bedford, Massachusetts. This migration built strong ties between the two locations, and a strong packet trade between New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the Can ...

and Cape Verde developed during the early to mid-19th century. The Erie Canal

The Erie Canal is a historic canal in upstate New York that runs east-west between the Hudson River and Lake Erie. Completed in 1825, the canal was the first navigable waterway connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes, vastly reducing t ...

was started in 1817 and finished in 1825, encouraging inland trade and strengthening the position of the port of New York.

Although the amount of tonnage registered in foreign trade did not equal that of the years 1815-17 or the figures of the next two decades, the proportion of American carriage in the foreign trade reached 92.5 percent in 1826, a larger percentage than has been attained before or since. Not only were we carrying practically all of our own goods, but the reputation of Yankee ship builders for turning out models which surpassed in speed, strength, and durability any vessels to be found, brought about the sale between 1815 and 1840 of 540,000 tons of shipping to foreigners. Not withstanding higher wages, it cost less to run an American vessel, for a smaller crew was carried. Of the world's total whaling fleet in 1842, it was estimated that of 882 ships 652 were American vessels.

The 1830s

In 1832,

In 1832, Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

Louis McLane ordered in writing for revenue cutters to conduct winter cruises to assist mariners in need, and Congress made the practice an official part of regulations in 1837. This was the beginning of the lifesaving mission that the later U.S. Coast Guard would be best known for worldwide. The side-wheel paddle steamer SS ''Great Western'' was the first purpose-built steamship to initiate regularly scheduled trans-Atlantic crossings, starting in 1838.

The record times of these steam ships (the Atlantic crossing to New York in thirteen and a half days) proved that steamers could make the trip in shorter time than the fastest sailing packet. The British government was farsighted enough to realize that the motive power of the immediate future was steam, and in 1839 heavily subsidized the Cunard Line, which began its career in 1840 with four side-wheeled wooden ships. The British Government, therefore, readily aided Samuel Cunard, as it did other owners, granting him a subsidy of $425,000 a year to carry the mails back and forth between Liverpool, Halifax, and Boston, with an occasional visit to Quebec. This policy of subsidization, which was continued to at least WW II by Great Britain, aided materially not only in giving her maritime interests a start in the new type of ships, but in helping them win and hold supremacy on the ocean. The Peninsular Company, afterwards the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company

P&O (in full, The Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company) is a British shipping and logistics company dating from the early 19th century. Formerly a public company, it was sold to DP World in March 2006 for £3.9 billion. DP World c ...

, was established in 1837, and the Pacific Steam Navigation Company

The Pacific Steam Navigation Company ( es, Compañía de Vapores del Pacífico, links=no) was a British commercial shipping company that operated along the Pacific coast of South America, and was the first to use steam ships for commercial traffi ...

in 1840, both subsidized.

The 1840s

The first regular steamship service from the west to the east coast of theUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

began on February 28, 1849, with the arrival of the SS California (1848)'' in San Francisco Bay. ''California'' left New York Harbor on October 6, 1848, rounded Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramí ...

at the tip of South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sout ...

, and arrived at San Francisco, California

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17th ...

after a 4-month 21-day journey. SS ''Great Eastern'' was built in 1854–1857 with the intent of linking Great Britain with India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, ''via'' the Cape of Good Hope, without coaling stops; she would know a turbulent history, and was never put to her intended use.

The years leading up to the Civil War were characterized by extremely rapid production in ship building. The 538,136 tons registered in foreign trade in 1831 had increased to 1,047,454 in 1847 and to 2,496,894 in 1862, a figure which represented the culmination of our ship-building tonnage until surpassed in WW I. From 1848 to 1858 ship building had been maintained at an average of 400,000 tons a year. This construction was caused by two conditions, the development of the clipper ship after 1845 and the increased demand for shipping.

Designed for speed, the clipper was built on sharp lines and carried a maximum of canvas and was the culmination of the intense rivalry between steam and canvas. It was intended primarily for long voyages, and was used especially for the California and Far Eastern trade. Given a fair breeze, a clipper ship could outdistance a steamship. It was not uncommon for a clipper to sail over 300 miles a day; the Flying Cloud (clipper)

''Flying Cloud'' was a clipper ship that set the world's sailing record for the fastest passage between New York and San Francisco, 89 days 8 hours. The ship held this record for over 130 years, from 1854 to 1989.

''Flying Cloud'' was the most ...

on a ninety-day run to San Francisco made 374 miles in one day. The Comet (clipper)

''Comet'' was an 1851 California clipper built by William H. Webb which sailed in the Australia trade and the tea trade. This extreme clipper was very fast. She had record passages on two different routes: New York City to San Francisco, and ...

, on an eighty-day voyage from San Francisco to New York averaged 210 miles a day. It appeared that the American ship builder, before he relinquished his supremacy, was intent upon demonstrating to what heights of efficiency and speed a sailing ship could attain.

The increased demand for shipping was the result of several factors. The discovery in 1848 of gold in California was a major cause along with the wars between Great Britain and China in 1840-42 and 1856-60 threw a part of the China trade into American hands. The revolutionary outbreaks of 1848 interrupted European trade, with a resultant benefit to Americans, while the Crimean War, which occupied many European boats in transporting troops and supplies, gave new openings to American ships. In addition the natural growth in population, wealth, and production necessitated increased shipping.

The volume of mail between the United States and Europe increased substantially during this period, and the capacity of the sailboat to deliver this mail efficiently and within a reasonable time was uncertain. Following the precedent established by England and other maritime nations, the federal government began its aid to ocean shipping with the overseas mail service. On March 3, 1845, Congress authorized the Postmaster General to invite bids on contracts to carry mail between the United States and abroad. Regular subsidized service between New York and Bremen, Havre, Liverpool and Panama was established under the Act of 1845. Subsidy payments averaged between $19,250 and $35,000 per round trip, and aggregated government expenditures to 1858 amounted to $14,400,000.http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1916&context=flr

This development led to the formation of the U.S. Mail Steamship Company

U.S. Mail Steamship Company was a company formed in 1848 by George Law, Marshall Owen Roberts and Bowes R. McIlvaine to assume the contract to carry the U. S. mails from New York City, with stops in New Orleans and Havana, to the Isthmus of P ...

and the Pacific Mail Steamship Company

The Pacific Mail Steamship Company was founded April 18, 1848, as a joint stock company under the laws of the State of New York by a group of New York City merchants. Incorporators included William H. Aspinwall, Edwin Bartlett (American consul ...

.

The 1850s

Almost as revolutionary as the gradual substitution of steam for sailing vessels was the very gradual substitution of iron and later steel ships for those of wood. With an abundance of coal and iron close to the sea, with skilled mechanics and cheap labor, Great Britain forged ahead from the start. Already by 1853 one-fourth of the tonnage built in Great Britain were steamships and more than one-fourth were built of iron. In the same year 22 percent of American tonnage was constructed for steamships, but scarcely any iron ships were built here. The Yankee ship builder, overconfident in the recognized superiority of his inimitable clipper ship, was blinded to the fact that the future of the sea was for the nation which could build the cheapest and the best iron steamships. There was a decidedly unhealthy element to this remarkable activity in ship building. In the first place the demand from Europe because of the Crimean War was abnormal; between 1854 and 1859 the European nations were buying 50,000 tons of shipping as against 10,000 tons in normal years. Unfortunately, this increase in the building of sailing ships came at a time when their days were numbered, for between 1850 and 1860 the share of ocean freight carried by steamers increased from 14 to 28 percent. When the abnormal demand for sailing ships should let up, as it did in 1858, it meant that shipyards built and equipped for the production of wooden ships and shipwrights trained for a type no longer wanted would be idle, while foreign shipyards already engaged in the building of the iron steamship would be in a decidedly superior position. The panic of 1857 precipitated the crash. In 1858 ship building, which had been maintained for the preceding years at an average of 400,000 tons a year dropped to 244,000 and in 1859 to 156,000. At that time the combined imports and exports carried in American bottoms was steadily declining, only 65.2 percent being carried in 1861 as against 92.5 percent in 1826. Another factor in the decline of American ship building was a fundamental economic change in progress throughout the United States. Capital was finding new and more profitable fields for investment. Manufacturing, which grew rapidly after the War of 1812, absorbed some of it; while considerable amounts were drawn into such internal improvements as canals and railways. Between 1820 and 1838 the states contracted debts of over $110,000,000 for the building of roads, canals, and railroads; from 1830 to 1860 over 30,000 miles of railroad were built, most of the capital coming from private investors. The minds of the venturous and ambitious turned from the sea to the unexploited West, and capital turned from ship building to the development of natural resources. In 1852, the lighthouse board established and published firstLight List

A list of lights is a publication describing lighthouses and other aids to maritime navigation. Most such lists are published by national hydrographic offices. Some nations, including the United Kingdom and the United States, publish lists that ...

and Notice to Mariners

A notice to mariners (NTM or NOTMAR,) advises mariners of important matters affecting navigational safety, including new hydrographic information, changes in channels and aids to navigation, and other important data.

Over 60 countries which pr ...

. In 1854, Andrew Furuseth

Andrew Furuseth (March 17, 1854 – January 22, 1938) of Åsbygda, Hedmark, Norway was a merchant seaman and an American labor leader. Furuseth was active in the formation of two influential maritime unions: the Sailors' Union of the Pacific ...

was born in Norway, and Western river engineers form a "fraternal organization" that is a precursor to the Marine Engineers' Beneficial Association

The Marine Engineers' Beneficial Association (MEBA) is the oldest maritime trade union in the United States still currently in existence, established in 1875. MEBA primarily represents licensed mariners, especially deck and engine officers wor ...

. Also, Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry established trade relations with Japan with the signing of the Convention of Kanagawa

The Convention of Kanagawa, also known as the Kanagawa Treaty (, ''Kanagawa Jōyaku'') or the Japan–US Treaty of Peace and Amity (, ''Nichibei Washin Jōyaku''), was a treaty signed between the United States and the Tokugawa Shogunate on March ...

. In 1857, New Bedford had 329 registered whaling

Whaling is the process of hunting of whales for their usable products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that became increasingly important in the Industrial Revolution.

It was practiced as an organized industr ...

ships. The discovery of petroleum

Petroleum, also known as crude oil, or simply oil, is a naturally occurring yellowish-black liquid mixture of mainly hydrocarbons, and is found in geological formations. The name ''petroleum'' covers both naturally occurring unprocessed crud ...

in Titusville, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, on August 27, 1859, by Edwin L. Drake was the beginning of the end of commercial whaling in the United States as kerosene

Kerosene, paraffin, or lamp oil is a combustible hydrocarbon liquid which is derived from petroleum. It is widely used as a fuel in aviation as well as households. Its name derives from el, κηρός (''keros'') meaning "wax", and was regi ...

, distilled from crude oil, replaced whale oil in lamps. Later, electricity gradually replaced oil lamps, and by the 1920s, the demand for whale oil had disappeared entirely.

Decline in the use of clippers started with the economic slump following the Panic of 1857 and continued with the gradual introduction of the steamship. Although clippers could be much faster than the early steamships, clippers were ultimately dependent on the vagaries of the wind, while steamers could reliably keep to a schedule. The ''steam clipper'' was developed around this time, and had auxiliary steam engines which could be used in the absence of wind. An example of this type was the ''Royal Charter'', built in 1857 and wrecked on the coast of Anglesey

Anglesey (; cy, (Ynys) Môn ) is an island off the north-west coast of Wales. It forms a principal area known as the Isle of Anglesey, that includes Holy Island across the narrow Cymyran Strait and some islets and skerries. Anglesey island ...

in 1859.

In 1859, the "Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Memp ...

and St. Louis Packet Line," which would later become the Anchor Line was formed, principally providing service to these two cities and points in between. The Anchor line was a steamboat company that operated a fleet of boats on the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it fl ...

between St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

, and , between 1859 and 1898, when it went out of business. It was one of the most well-known, if not successful, pools of steamboats formed on the lower Mississippi River in the decades following the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

.

The 1860s

The final blow to clipper ships came in the form of the Suez Canal, opened in 1869, which provided a huge shortcut for steamships betweenEurope

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

and Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an are ...

, but which was difficult for sailing ships to use.

=Civil War era

= Merchant shipping was a key target in the U.S. Civil War. For example, the CSS ''Alabama'', a Confederate sloop-of-war commissioned on 24 August 1862, spent months capturing and burning ships in the North Atlantic and intercepting grain ships bound for Europe. Other Confederatecommerce raiders

Commerce raiding (french: guerre de course, "war of the chase"; german: Handelskrieg, "trade war") is a form of naval warfare used to destroy or disrupt logistics of the enemy on the open sea by attacking its merchant shipping, rather than eng ...

included the CSS ''Sumter'', CSS ''Florida'', and CSS ''Shenandoah''.

The elements contributing to the decline of the merchant marine were already operative before the Civil War, and the result would undoubtedly have been the same if that conflict had not come. The war, however, accentuated a tendency already existing and dealt a blow from which the merchant marine failed to recover until artificially revived during World War I. In 1861 registered American tonnage in foreign trade amounted to 2,496,894 tons and in 1865 to 1,518,350, while the percent of imports and exports carried in American ships dropped in the same years from 66.2 to 27.7. The decrease of tonnage in these years of some 900,000 tons was chiefly due to two causes. The first of these was the loss sustained from Confederate cruisers such as the Alabama built and fitted out in England contrary to the laws of warfare. The second and most important was the sale during the four years 1862-65 of 751,595 tons of shipping abroad, occasioned by (1) lack of confidence, decline in profits due to continual Confederate captures and high insurance rates, and (2) decline in export business due to the cessation of cotton shipments abroad.

A second round of ocean-mail contracts was authorized by Congress on May 28, 1864. Pursuant to the provisions of this Act, the United States and Brazil entered into a ten-year contract for monthly voyages between the United States and South America. Of the $250,000 annual subsidy requirement, the United States contributed $150,000 and Brazil $100,000. Subsequent subsidies to various individual American flag lines amounted to approximately $6,500,000 between 1864 and 1877.

Efforts by the Pacific Mail Steamship Company

The Pacific Mail Steamship Company was founded April 18, 1848, as a joint stock company under the laws of the State of New York by a group of New York City merchants. Incorporators included William H. Aspinwall, Edwin Bartlett (American consul ...

to increase its subsidies and the political scandals that grew out of these efforts, caused the Government to abrogate all subsidies to the Lines. Little more was done by the Government until the passage of the Ocean Mail Act in 1891.

=1866–1870

= First West Coast attempt at unionizing merchant seamen with the "Seamen's Friendly Union and Protective Society." The union quickly dissolves. The Civil War dealt the merchant marine a blow from which it never recovered except for the assistance of government intervention in World War I and later. Destruction by Confederate privateers and large sales abroad decreased the amount of tonnage. Delay in adopting iron steam-driven ships gave British builders an advantage which they continued to hold. But more important than all else was the fact that more profitable investments in internal transportation and the exploration of raw materials in the great industrial age which dawned after the war drew capital away from the sea. Lack of government interest helped complete the downfall of American shipping. The five years following the Civil War showed a slight revival but the forces tending to a decline continued operative. American shipping in foreign trade and the fisheries, which amounted to 2,642,628 tons in 1870, had dropped to 826,694 tons in 1900. In 1860 the percentage of imports and exports carried in American ships was 66.5, but this dropped in 1870 to 35.6, in 1880 to 13, in 1890 to 9.4, in 1900 to 7.1.The 1870s

By 1870, a number of inventions, such as thescrew propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

and the triple expansion engine made trans-oceanic shipping economically viable. Thus began the era of cheap and safe travel and trade around the world. Starting in 1873, deck officers were required to pass mandatory license examinations. In 1874, the New York Nautical School was founded as a means of training young men for careers at sea in the postwar merchant marine, becoming the first school of its type in the United States. It would later become the State University of New York Maritime College

State University of New York Maritime College (SUNY Maritime College) is a public maritime college in the Bronx, New York City. It is part of the State University of New York (SUNY) system. Founded in 1874, the SUNY Maritime College was the fir ...

. Also in 1874, the union that would become the Marine Engineers' Beneficial Association

The Marine Engineers' Beneficial Association (MEBA) is the oldest maritime trade union in the United States still currently in existence, established in 1875. MEBA primarily represents licensed mariners, especially deck and engine officers wor ...

formed. The Buffalo Association of Engineers began corresponding with other marine engineer associations around the country. These organizations held a convention in Cleveland, Ohio including delegates from Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second-largest city in the U.S. state of New York (behind only New York City) and the seat of Erie County. It is at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of the Niagara River, and is across the Canadian border from Sou ...

, Cleveland, Ohio, Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at t ...

, Michigan

Michigan () is a U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest, upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the List of U.S. states and ...

, Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rockf ...

and Baltimore, Maryland

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

. This organization called itself the National Marine Engineers Association and chose as its president Garret Douw of Buffalo. On February 23, 1875 MEBA was formed. As of 1876, Plimsoll marks were required on all U.S. vessels

The 1880s

In 1880, passenger steamship ''Columbia'' of theOregon Railroad and Navigation Company

The Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company (OR&N) was a railroad that operated a rail network of running east from Portland, Oregon, United States, to northeastern Oregon, northeastern Washington, and northern Idaho. It operated from 1896 as a ...

became the first outside usage of Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February 11, 1847October 18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventi ...

's incandescent light bulb

An incandescent light bulb, incandescent lamp or incandescent light globe is an electric light with a wire filament heated until it glows. The filament is enclosed in a glass bulb with a vacuum or inert gas to protect the filament from oxid ...

and the first ship to use a dynamo

"Dynamo Electric Machine" (end view, partly section, )

A dynamo is an electrical generator that creates direct current using a commutator. Dynamos were the first electrical generators capable of delivering power for industry, and the foundati ...

.Dalton, AnthonyA long, dangerous coastline : shipwreck tales from Alaska to California

Heritage House Publishing Company, 1 Feb 2011 - 128 pages The Sailors' Union of the Pacific (SUP) founded on March 6, 1885, in

San Francisco, California

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17th ...

is an American labor union of mariners, fishermen and boatmen working aboard U.S. flag vessels. At its fourth meeting in 1885, the fledgling organization adopted the name Coast Sailor's Union and elected George Thompson its first president. Andrew Furuseth