In the

history of the United States

The history of the lands that became the United States began with the arrival of the first people in the Americas around 15,000 BC. Numerous indigenous cultures formed, and many saw transformations in the 16th century away from more densely ...

, the period from 1918 through 1945 covers the post-

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

era, the

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, and

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. After World War I, the U.S. rejected the

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

and did not join the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

.

In 1920, the manufacture, sale, import and export of alcohol was

prohibited by an amendment to the

United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the natio ...

. Possession of liquor, and drinking it, was never illegal. The overall level of alcohol consumption did go down, however, state and local governments avoided aggressive enforcement. The federal government was overwhelmed with cases, so that

bootlegging and

speakeasies

A speakeasy, also called a blind pig or blind tiger, is an illicit establishment that sells alcoholic beverages, or a retro style bar that replicates aspects of historical speakeasies.

Speakeasy bars came into prominence in the United States ...

flourished in every city. Well-organized criminal gangs exploded in numbers, finances, power, and influence on city politics.

A few local domestic-terrorist attacks from radicals, like the

1920 Wall Street Bombing and the

1919 United States anarchist bombings sparked the first

Red Scare

A Red Scare is the promotion of a widespread fear of a potential rise of communism, anarchism or other leftist ideologies by a society or state. The term is most often used to refer to two periods in the history of the United States which ar ...

.

Culture wars

A culture war is a cultural conflict between social groups and the struggle for dominance of their values, beliefs, and practices. It commonly refers to topics on which there is general societal disagreement and polarization in societal value ...

between fundamentalist Christians and modernists became more intense, as demonstrated by prohibition, the

KKK

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Cath ...

, and the highly publicized

Scopes Trial.

The nation enjoyed a period of sustained prosperity in the 1920s. Agriculture went through a bubble in soaring land prices that collapsed in 1921, and that sector remained depressed. Coal mining was shrinking as oil became the main energy source. Otherwise most sectors prospered. Construction flourished as office buildings, factories, paved roads, and new housing was evident everywhere. Automobile production soared, suburban housing expanded and the nation's homes, towns and cities were electrified, along with some farms. Prices were stable, and the

Gross Domestic Product

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a monetary measure of the market value of all the final goods and services produced and sold (not resold) in a specific time period by countries. Due to its complex and subjective nature this measure is of ...

(GDP) grew steadily until 1929, when the financial speculation bubble burst as Wall Street crashed.

In foreign policy President Wilson helped found the League of Nations but the U.S. never joined it, as the Congress refused to give up its constitutional role in declaring war. The nation instead took the initiative to disarm the world, most notably at the

Washington Conference in 1921–22. Washington also stabilized the European economy through the

Dawes Plan

The Dawes Plan (as proposed by the Dawes Committee, chaired by Charles G. Dawes) was a plan in 1924 that successfully resolved the issue of World War I reparations that Germany had to pay. It ended a crisis in European diplomacy following Wor ...

and the

Young Plan

The Young Plan was a program for settling Germany's World War I reparations. It was written in August 1929 and formally adopted in 1930. It was presented by the committee headed (1929–30) by American industrialist Owen D. Young, founder and for ...

. The

Immigration Act of 1924

The Immigration Act of 1924, or Johnson–Reed Act, including the Asian Exclusion Act and National Origins Act (), was a United States federal law that prevented immigration from Asia and set quotas on the number of immigrants from the Eastern ...

was aimed at stabilizing the traditional ethnic balance and strictly limiting the total inflow. The act completely blocked Asian immigrants, providing no means for them to get in.

The

Wall Street Crash of 1929

The Wall Street Crash of 1929, also known as the Great Crash, was a major American stock market crash that occurred in the autumn of 1929. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange coll ...

and the ensuing Great Depression led to government efforts to restart the economy and help its victims. The recovery, however, was very slow. The nadir of the Great Depression was 1933, and recovery was rapid until the recession of 1938 proved a setback. There were no major new industries in the 1930s that were big enough to drive growth the way autos, electricity and construction had been so powerful in the 1920s. GDP surpassed 1929 levels in 1940.

By 1939,

isolationist

Isolationism is a political philosophy advocating a national foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality and opposes entan ...

sentiment in America had ebbed, and after the stunning fall of France in 1940 to

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, the United States began rearming itself and sent a large stream of money and military supplies to Britain and the Soviet Union. Following the

attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii ...

, the United States entered World War II to fight against Nazi Germany,

Fascist Italy, and

Imperial Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent forma ...

, known as the "

Axis Powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

". Italy surrendered in 1943, and Germany and Japan in 1945, after massive devastation and loss of life, while the US emerged far richer and with few casualties.

1919: strikes, riots and scares

The United States was in turmoil throughout 1919. The huge number of returning veterans could not find work, something the Wilson administration had given little thought to. After the war, fear of subversion resumed in the context of the Red Scare, massive strikes in major industries (steel, meatpacking) and violent race riots. Radicals bombed Wall Street, and

workers went on strike in Seattle in February. During 1919, a series of more than 20 riotous and violent black-white race-related incidents occurred. These included the

Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

,

Omaha

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 39th-largest c ...

, and

Elaine Race Riot

The Elaine massacre occurred on September 30–October 2, 1919 at Hoop Spur in the vicinity of Elaine in rural Phillips County, Arkansas. As many as several hundred African Americans and five white men were killed. Estimates of deaths made in ...

s.

A phenomenon known as the ''

Red Scare

A Red Scare is the promotion of a widespread fear of a potential rise of communism, anarchism or other leftist ideologies by a society or state. The term is most often used to refer to two periods in the history of the United States which ar ...

'' took place 1918–1919. With the rise of violent Communist revolutions in Europe, leftist radicals were emboldened by the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and were eager to respond to Lenin's call for world revolution. On May 1, 1919, a parade in

Cleveland, Ohio

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S ...

, protesting the imprisonment of the

Socialist Party

Socialist Party is the name of many different political parties around the world. All of these parties claim to uphold some form of socialism, though they may have very different interpretations of what "socialism" means. Statistically, most of ...

leader,

Eugene Debs

Eugene may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Eugene (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Eugene (actress) (born 1981), Kim Yoo-jin, South Korean actress and former member of the sin ...

, erupted into the violent

May Day Riots. A series of bombings in 1919 and assassination attempts further inflamed the situation. Attorney General

A. Mitchell Palmer conducted the

Palmer Raids

The Palmer Raids were a series of raids conducted in November 1919 and January 1920 by the United States Department of Justice under the administration of President Woodrow Wilson to capture and arrest suspected socialists, especially anarchists ...

, a series of raids and arrests of non-citizen

socialists

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the econ ...

,

anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessari ...

, radical unionists, and immigrants. They were charged with planning to overthrow the government. By 1920, over 10,000 arrests were made, and the immigrants caught up in these raids were deported back to Europe, most notably the anarchist

Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born anarchist political activist and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the ...

, who years before had attempted to assassinate industrialist

Henry Clay Frick

Henry Clay Frick (December 19, 1849 – December 2, 1919) was an American industrialist, financier, and art patron. He founded the H. C. Frick & Company coke manufacturing company, was chairman of the Carnegie Steel Company, and played a maj ...

.

Aftermath of World War I

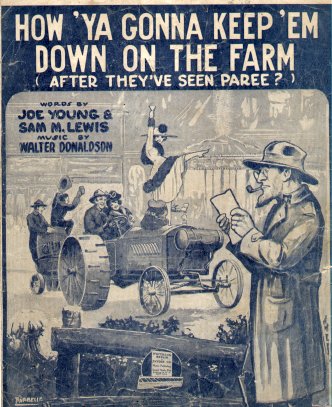

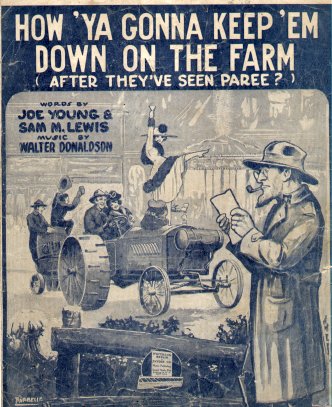

A popular

Tin Pan Alley

Tin Pan Alley was a collection of History of music publishing, music publishers and songwriters in New York City that dominated the American popular music, popular music of the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It origin ...

song of 1919 asked, concerning the United States troops returning from World War I, "

". In fact, many did not remain "down on the farm"; there was a great migration of youth from farms to nearby towns and smaller cities. The average distance moved was only 10 miles (16 km). Few went to the cities with over 100,000 people. However, agriculture became increasingly mechanized with widespread use of the

tractor

A tractor is an engineering vehicle specifically designed to deliver a high tractive effort (or torque) at slow speeds, for the purposes of hauling a trailer or machinery such as that used in agriculture, mining or construction. Most commo ...

, other heavy equipment, and superior techniques disseminated through

County Agents, who were employed by state agricultural colleges and funded by the Federal government.

In 1919,

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

campaigned for the U.S. to join the new

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

, which he had been instrumental in creating, but he rejected the Republican compromise on the issue, and it was impossible to gain a 2/3 majority. During a grueling cross-country tour to promote the League, Wilson suffered a series of strokes. He never recovered physically and lost his leadership skills and was unable to negotiate or compromise. The Senate rejected entry into the League.

Defeat in the Great War left Germany in a state of turmoil and heavily in debt for

war reparations

War reparations are compensation payments made after a war by one side to the other. They are intended to cover damage or injury inflicted during a war.

History

Making one party pay a war indemnity is a common practice with a long history.

...

, payments to the victorious

Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

. The Allies in turn owed large sums to the US Treasury for war loans. The US effectively orchestrated payment of reparations; under the

Dawes Plan

The Dawes Plan (as proposed by the Dawes Committee, chaired by Charles G. Dawes) was a plan in 1924 that successfully resolved the issue of World War I reparations that Germany had to pay. It ended a crisis in European diplomacy following Wor ...

, American banks loaned money to Germany to pay the reparations to countries like Britain and France, which in turn paid off their own war debts to the US. In the 1920s, European and American economies reached new levels of industrial production and prosperity.

Women's suffrage

After a

long period of agitation, U.S. women were able in 1920 to obtain the necessary votes from a majority of men to obtain the right to vote in all state and federal elections. Women participated in the 1920 Presidential and Congressional elections.

Politicians responded to the new electorate by emphasizing issues of special interest to women, especially prohibition, child health, public schools, and world peace. Women did respond to these issues, but in terms of general voting they shared the same outlook and the same voting behavior as men.

The suffrage organization

NAWSA became the

League of Women Voters

The League of Women Voters (LWV or the League) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan political organization in the United States. Founded in 1920, its ongoing major activities include registering voters, providing voter information, and advocating for vot ...

. Alice Paul's National Woman's Party began lobbying for full equality and the

Equal Rights Amendment

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) is a proposed amendment to the United States Constitution designed to guarantee equal legal rights for all American citizens regardless of sex. Proponents assert it would end legal distinctions between men and ...

, which would pass Congress during the second wave of the women's movement in 1972, but was not ratified and never took effect. The main surge of women voting came in 1928, when the

big-city machines realized they needed the support of women to elect

Al Smith

Alfred Emanuel Smith (December 30, 1873 – October 4, 1944) was an American politician who served four terms as Governor of New York and was the Democratic Party's candidate for president in 1928.

The son of an Irish-American mother and a Ci ...

, while rural

dry counties mobilized women to support

Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholi ...

and vote for Republican

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gre ...

. Catholic women were reluctant to vote in the early 1920s, but they registered in very large numbers for the 1928 election—the first in which Catholicism was a major issue. A few women were elected to office, but none became especially prominent during this time period. Overall, the women's rights movement was dormant in the 1920s, since Susan B. Anthony and the other prominent activists had died, and apart from

Alice Paul

Alice Stokes Paul (January 11, 1885 – July 9, 1977) was an American Quaker, suffragist, feminist, and women's rights activist, and one of the main leaders and strategists of the campaign for the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, w ...

few younger women came along to replace them.

Roaring Twenties

In the

U.S. presidential election of 1920, the

Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

returned to the White House with the landslide victory of

Warren G. Harding, who promised a "return to normalcy" after the years of war, ethnic hatreds, race riots and exhausting reforms. Harding used new advertising techniques to lead the GOP to a massive landslide, carrying the major cities as many Irish Catholics and Germans, feeling betrayed, deserted the Democrats.

Prosperity

Except for a recession in 1920–21, the United States enjoyed a period of prosperity. Good times were widespread for all sectors (except agriculture and coal mining). New industries (especially electric power, movies, automobiles, gasoline, tourist travel, highway construction, and housing) flourished.

"The business of America is business," proclaimed President Coolidge. Entrepreneurship flourished and was widely hailed. Business interests had captured control of the regulatory agencies established before 1915 and used progressive rhetoric, emphasizing technological efficiency and prosperity as the keys to social improvement.

William Allen White

William Allen White (February 10, 1868 – January 29, 1944) was an American newspaper editor, politician, author, and leader of the Progressive movement. Between 1896 and his death, White became a spokesman for middle America.

At a 193 ...

, a leading progressive spokesman, supported GOP candidate

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gre ...

in 1928 as one who could "spiritualize" business prosperity and make it serve progressive ends.

Energy was a key to the economy, especially electricity and oil. As electrification reached all the cities and towns, consumers demanded new products such as light bulbs, refrigerators, and toasters. Factories installed electric motors and saw productivity surge. With the

oil booms in Texas, Oklahoma, and California, the United States dominated world petroleum production, now even more important in an age of automobiles and trucks.

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gre ...

became world famous by leading the

Commission for Relief in Belgium

The Commission for Relief in Belgium or C.R.B. − known also as just Belgian Relief − was an international (predominantly American) organization that arranged for the supply of food to German-occupied Belgium and northern France during the Wor ...

in World War I. He directed the

U.S. Food Administration

The United States Food Administration (1917–1920) was an independent Federal agency that controlled the production, distribution and conservation of food in the U.S. during the nation's participation in World War I. It was established to prev ...

when the U.S. entered the war, and served as Secretary of Commerce in the 1920s. An energetic exponent of

progressivism

Progressivism holds that it is possible to improve human societies through political action. As a political movement, progressivism seeks to advance the human condition through social reform based on purported advancements in science, tech ...

he promoted engineering-style efficiency in business and public service, and promoted standardization, elimination of waste, and international trade. He easily won the

Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

presidential nomination in 1928 and defeated Democrat

Al Smith

Alfred Emanuel Smith (December 30, 1873 – October 4, 1944) was an American politician who served four terms as Governor of New York and was the Democratic Party's candidate for president in 1928.

The son of an Irish-American mother and a Ci ...

in a landslide.

The promise of prosperity made Hoover president, but the reality of economic decline ruined him, as Democrats tarred him with blame for the

Great Depression in the United States

In the History of the United States, United States, the Great Depression began with the Wall Street Crash of 1929, Wall Street Crash of October 1929 and then spread worldwide. The nadir came in 1931–1933, and recovery came in 1940. The stock m ...

. He was falsely accused of ignoring the crisis. Starting in late 1929 he tried multiple new ways to reverse the economic collapse as the world-wide Great Depression engulfed the United States. He called in all the experts for advice and looked for voluntary solutions that did not require government compulsion. No matter what he did the economy spiraled downward, hitting bottom just as he left office in early 1933. He lacked the political skills to rally support and was defeated in a landslide

in 1932 by

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

. After this loss, Hoover became staunchly

conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

, and spoke widely against liberal

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Con ...

policies.

Unions

Labor unions grew very rapidly during the war, emerging with a large membership, full treasuries, and a temporary government guarantee of the right of collective bargaining. Inflation was high during the war, but wages went up even faster. However, unions were weak in heavy industry, such as automobiles and steel. Their main strength was in construction, printing, railroads, and other crafts where the

AFL

AFL may refer to:

Sports

* American Football League (AFL), a name shared by several separate and unrelated professional American football leagues:

** American Football League (1926) (a.k.a. "AFL I"), first rival of the National Football Leagu ...

had a strong system in place. Total union membership had soared from 2.7 million in 1914 to 5 million at its peak in 1919. An aggressive spirit appeared in 1919, as demonstrated by the general strike in Seattle and the police strike in Boston. The larger unions made a dramatic move for expansion in 1919 by calling major strikes in clothing, meatpacking, steel, coal, and railroads. The corporations fought back, and the strikes failed. The unions held on to their gains among machinists, textile workers, and seamen, and in such industries as food and clothing, but overall membership fell back to 3.5 million, where it stagnated until the New Deal passed the

Wagner Act

The National Labor Relations Act of 1935, also known as the Wagner Act, is a foundational statute of United States labor law that guarantees the right of private sector employees to organize into trade unions, engage in collective bargaining, and ...

in 1935.

Real earnings (after taking inflation, unemployment, and short hours into account) of all employees doubled over 1918–45. Setting 1918 as 100, the index went to 112 in 1923, 122 in 1929, 81 in 1933 (the low point of the depression), 116 in 1940, and 198 in 1945.

The bubble of the late 1920s was reflected by the extension of credit to a dangerous degree, including in the

stock market

A stock market, equity market, or share market is the aggregation of buyers and sellers of stocks (also called shares), which represent ownership claims on businesses; these may include ''securities'' listed on a public stock exchange, ...

, which rose to record high levels. Government size had been at low levels, causing major freedom of the economy and more prosperity. It became apparent in retrospect after the

stock market crash of 1929

The Wall Street Crash of 1929, also known as the Great Crash, was a major American stock market crash that occurred in the autumn of 1929. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange colla ...

that credit levels had become dangerously inflated.

Immigration restriction

The United States became more

anti-immigration

Opposition to immigration, also known as anti-immigration, has become a significant political ideology in many countries. In the modern sense, immigration refers to the entry of people from one state or territory into another state or territory ...

in outlook during this period. The American

Immigration Act of 1924

The Immigration Act of 1924, or Johnson–Reed Act, including the Asian Exclusion Act and National Origins Act (), was a United States federal law that prevented immigration from Asia and set quotas on the number of immigrants from the Eastern ...

limited immigration from countries where 2% of the total

U.S. population

The United States had an official estimated resident population of 333,287,557 on July 1, 2022, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. This figure includes the 50 states and the District of Columbia but excludes the population of five unincorpor ...

, per the 1890

census

A census is the procedure of systematically acquiring, recording and calculating information about the members of a given population. This term is used mostly in connection with national population and housing censuses; other common censuses inc ...

(not counting African Americans), were immigrants from that country. Thus, the massive influx of Europeans that had come to America during the first two decades of the century slowed to a trickle. Asians and citizens of India were prohibited from immigrating altogether.

Jazz

The "

Jazz Age" symbolized the popularity of new musics and dance forms, which attracted younger people in all the large cities as the older generation worried about the threat of looser sexual standards as suggested by the uninhibited "

flapper

Flappers were a subculture of young Western women in the 1920s who wore short skirts (knee height was considered short during that period), bobbed their hair, listened to jazz, and flaunted their disdain for what was then considered acceptab ...

." In every locality, Hollywood discovered an audience for its silent films. It was an age of celebrities and heroes, with movie stars, boxers, home run hitters, tennis aces, and football standouts grabbing widespread attention.

Black culture, especially in music and literature, flourished in many cities such as New Orleans, Memphis, and Chicago but nowhere more than in New York City, site of the

Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of African American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, spanning the 1920s and 1930s. At the t ...

. The

Cotton Club

The Cotton Club was a New York City nightclub from 1923 to 1940. It was located on 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue (1923–1936), then briefly in the midtown Theater District (1936–1940).Elizabeth Winter"Cotton Club of Harlem (1923- )" Blac ...

nightclub and the

Apollo Theater

The Apollo Theater is a music hall at 253 West 125th Street between Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard (Seventh Avenue) and Frederick Douglass Boulevard (Eighth Avenue) in the Harlem neighborhood of Upper Manhattan in New York City. It is a ...

became famous venues for artists and writers.

Radio was a new industry that grew explosively from home-made

crystal sets, picking up faraway stations to stations in every large city by the mid-decade. By 1927 two national networks had been formed, the

NBC Red Network

The NBC, National Broadcasting Company's NBC Radio Network (known as the NBC Red Network prior to 1942) was an American commercial radio network which was in operation from 1926 through 2004. Along with the Blue Network, NBC Blue Network it was ...

and the

Blue Network

The Blue Network (previously known as the NBC Blue Network) was the on-air name of a now defunct American radio network, which broadcast from 1927 through 1945.

Beginning as one of the two radio networks owned by the National Broadcasting Comp ...

(ABC). The broadcast fare was mostly music, especially by

big band

A big band or jazz orchestra is a type of musical ensemble of jazz music that usually consists of ten or more musicians with four sections: saxophones, trumpets, trombones, and a rhythm section. Big bands originated during the early 1910s ...

s.

Prohibition

In 1920, the manufacture, sale, import and export of alcohol was prohibited by the

Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Eighteenth Amendment (Amendment XVIII) of the United States Constitution established the prohibition of alcohol in the United States. The amendment was proposed by Congress on December 18, 1917, and was ratified by the requisite number of ...

in an attempt to alleviate high rates of alcoholism and, especially, political corruption led by saloon-based politicians. It was enforced at the federal level by the

Volstead Act

The National Prohibition Act, known informally as the Volstead Act, was an act of the 66th United States Congress, designed to carry out the intent of the 18th Amendment (ratified January 1919), which established the prohibition of alcoholic d ...

. Most states let the federals do the enforcing. Drinking or owning liquor was not illegal, only the manufacture or sale. National Prohibition ended in 1933, although it continued for a while in some states. Prohibition is considered by most (but not all) historians to have been a failure because

organized crime

Organized crime (or organised crime) is a category of transnational, national, or local groupings of highly centralized enterprises run by criminals to engage in illegal activity, most commonly for profit. While organized crime is generally th ...

was strengthened.

[Daniel Okrent, ''Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition'' (2010)]

Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Cat ...

(KKK) is the name of three entirely different organizations (1860s, 1920s, post 1960) that used the same nomenclature and costumes but had no direct connection. The KKK of the 1920s was a purification movement that rallied against crime, especially violation of prohibition, and decried the growing "influence" of "big-city" Catholics and

Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

, many of them immigrants and their descendants from Ireland as well as Southern and Eastern Europe. Its membership was often exaggerated but possibly reached as many as 4 million men, but no prominent national figure claimed membership; no daily newspaper endorsed it, and indeed most actively opposed the Klan. Membership was verily evenly spread across the nation's white Protestants,

North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north ...

,

West

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some ...

, and

South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

, urban and rural. Historians in recent years have explored the Klan in depth. The KKK of the 1860s and the current KKK were indeed violent. However, historians discount lurid tales of a murderous group in the 1920s. Some crimes were probably committed in

Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion in the Southern United States. The term was first used to describe the states most dependent on plantations and slavery prior to the American Civil War. Following the wa ...

states but were quite uncommon elsewhere. The local Klans seem to have been poorly organized and were exploited as money-making devices by organizers more than anything else. (Organizers charged a $10 application fee and up to $50 for costumes.) Nonetheless, the KKK had become prominent enough that it staged a huge rally in Washington DC in 1925. Soon afterward, the national headlines reported rape and murder by the KKK leader in

Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th ...

, and the group quickly lost its mystique and nearly all its members.

Scopes "Monkey" Trial

The

Scopes Trial of 1925 was a

Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 36th-largest by ...

court case that tested a state law which forbade the teaching of "any theory that denies the story of the

Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals." The law was the result of a systematic drive by religious

Fundamentalists

Fundamentalism is a tendency among certain groups and individuals that is characterized by the application of a strict literal interpretation to scriptures, dogmas, or ideologies, along with a strong belief in the importance of distinguishi ...

to throw back the onslaught of modern ideas in theology and science. In a spectacular trial that drew national attention thanks to the roles of three-time Democratic presidential candidate

William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

for the prosecution and famed lawyer

Clarence Darrow

Clarence Seward Darrow (; April 18, 1857 – March 13, 1938) was an American lawyer who became famous in the early 20th century for his involvement in the Leopold and Loeb murder trial and the Scopes "Monkey" Trial. He was a leading member of t ...

for the defense,

John T. Scopes

John Thomas Scopes (August 3, 1900 – October 21, 1970) was a teacher in Dayton, Tennessee, who was charged on May 5, 1925, with violating Tennessee's Butler Act, which prohibited the teaching of human evolution in Tennessee schools. He was trie ...

was convicted of teaching evolution, but the verdict was overturned on a technicality. The Fundamentalists were widely ridiculed, with writers like

H. L. Mencken

Henry Louis Mencken (September 12, 1880 – January 29, 1956) was an American journalist, essayist, satirist, cultural critic, and scholar of American English. He commented widely on the social scene, literature, music, prominent politicians, ...

poking merciless ridicule at them; their efforts to pass state laws proved a failure.

Federal government

Led by Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover, the federal government in the 1920s took on an increasing role in business and economic affairs. In addition to Prohibition, the government obtained new powers and duties such as funding and overseeing the new

U.S. Highway system, controlling agriculture, and the regulating radio and commercial aviation. The result was a rapid spread of standardized roads and broadcasts that were welcomed by most Americans.

The

Harding

Harding may refer to:

People

*Harding (surname)

*Maureen Harding Clark (born 1946), Irish jurist

Places Australia

* Harding River

Iran

* Harding, Iran, a village in South Khorasan Province

South Africa

* Harding, KwaZulu-Natal

United St ...

Administration was rocked by the

Teapot Dome scandal

The Teapot Dome scandal was a bribery scandal involving the administration of United States President Warren G. Harding from 1921 to 1923. Secretary of the Interior Albert Bacon Fall had leased Navy petroleum reserves at Teapot Dome in Wyomi ...

, the most famous of a number of episodes involving Harding's cabinet members. The president, exhausted and dismayed from the news of the scandals, died of a heart attack in August 1923. His vice-president, Calvin Coolidge, succeeded him. Coolidge could not have been a more different personality than his predecessor. Dour, puritanical, and spotlessly honest, his White House stood in sharp contrast to the drinking, gambling, and womanizing that went on under Harding. In 1924, he was easily elected in his own right with the slogan "Keep Cool With Coolidge". Overall, the Harding and Coolidge administrations marked a return to the hands-off style of 19th-century presidents in contrast to the activism of Roosevelt and Wilson. Coolidge, who spent the entire summer on vacation during his years in office, famously said "The business of the American people is business."

When Coolidge declined to run again in the

1928 election, the Republican Party nominated engineer and

Secretary of Commerce

The United States secretary of commerce (SecCom) is the head of the United States Department of Commerce. The secretary serves as the principal advisor to the president of the United States on all matters relating to commerce. The secretary rep ...

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gre ...

, who was elected by a wide margin over

Al Smith

Alfred Emanuel Smith (December 30, 1873 – October 4, 1944) was an American politician who served four terms as Governor of New York and was the Democratic Party's candidate for president in 1928.

The son of an Irish-American mother and a Ci ...

, the first Catholic nominee. Hoover was a technocrat who had low regard for politicians. Instead he was a believer in the efficacy of individualism and business enterprise, with a little coordination by the government, to cure all problems. He envisioned a future of unbounded plenty and the imminent end of poverty in America. A year after his election, the stock market crashed, and the nation's economy slipped downward into the

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

.

After the crash, Hoover attempted to put in place many efforts to restore the economy, especially the fast-sinking agricultural sector. None worked. Hoover believed in stimulus spending and encouraged state and local governments, as well as the federal government, to spend heavily on public buildings, roads, bridges—and, most famously, the

Hoover Dam

Hoover Dam is a concrete arch-gravity dam in the Black Canyon of the Colorado River, on the border between the U.S. states of Nevada and Arizona. It was constructed between 1931 and 1936 during the Great Depression and was dedicated on S ...

on the Colorado River. But with tax revenues falling fast, the states and localities plunged into their own fiscal crises. Republicans, following their traditional mass drums, along with pressure from the farm bloc, passed the

Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act

The Tariff Act of 1930 (codified at ), commonly known as the Smoot–Hawley Tariff or Hawley–Smoot Tariff, was a law that implemented protectionist trade policies in the United States. Sponsored by Senator Reed Smoot and Representative Willi ...

, which raised tariffs. Canada and other nations retaliated by raising their tariffs on American goods and moving their trade in other directions. American imports and exports plunged by more than two thirds, but since international trade was less than 5% of the American economy, the damage done was limited. The entire world economy, led by the United States, had fallen into a downward spiral that got worse and worse, and in 1931–32 began plunging downward even faster. Hoover had Congress set up a new relief agency, the

Reconstruction Finance Corporation The Reconstruction Finance Corporation was a government corporation administered by the United States Federal Government between 1932 and 1957 that provided financial support to state and local governments and made loans to banks, railroads, mortga ...

, in 1932, but it proved too little too late.

Foreign policy, 1919–1941

In the 1920s, American policy was an active involvement in international affairs, while systematically ignoring the League of Nations. Instead Washington set up numerous diplomatic ventures, and used the enormous financial power of the United States to dictate major diplomatic questions in Europe.

Presidents Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover avoided any political commitments or alliances with anyone else. Franklin Roosevelt followed suit before World War II broke out in 1939. They minimized contact with the League of Nations. However, as historian Jerald Combs reports their administrations in no way returned to 19th-century isolationism. The key Republican leaders:

: including

Elihu Root

Elihu Root (; February 15, 1845February 7, 1937) was an American lawyer, Republican politician, and statesman who served as Secretary of State and Secretary of War in the early twentieth century. He also served as United States Senator from ...

,

Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes Sr. (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American statesman, politician and jurist who served as the 11th Chief Justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party, he previously was the ...

, and Hoover himself, were Progressives who accepted much of Wilson's internationalism. ... They did seek to use American political influence and economic power to goad European governments to moderate the Versailles peace terms, induce the Europeans to settle their quarrels peacefully, secure disarmament agreements, and strengthen the European capitalist economies to provide prosperity for them and their American trading partners.

The

Washington Naval Conference

The Washington Naval Conference was a disarmament conference called by the United States and held in Washington, DC from November 12, 1921 to February 6, 1922. It was conducted outside the auspices of the League of Nations. It was attended by nine ...

was the most successful diplomatic venture in the 1920s. It was held in Washington, under the Chairmanship of Secretary of State

Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes Sr. (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American statesman, politician and jurist who served as the 11th Chief Justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party, he previously was the ...

from 12 November 1921 to 6 February 1922. Conducted outside the auspice of the League of Nations, it was attended by nine nations—the United States, Japan, China, France, Great Britain, Italy, Belgium, Netherlands, and Portugal Russia and Germany were pariahs and were not invited. It focused on resolving misunderstandings or conflicts regarding interests in the Pacific Ocean and East Asia. The main achievement was a series of naval disarmament agreements agreed to by all the participants, that lasted for a decade. It resulted in three major treaties:

Four-Power Treaty

The was a treaty signed by the United States, Great Britain, France and Japan at the Washington Naval Conference on 13 December 1921. It was partly a follow-on to the Lansing-Ishii Treaty, signed between the U.S. and Japan. This was a treaty r ...

,

Five-Power Treaty

The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, was a treaty signed during 1922 among the major Allies of World War I, which agreed to prevent an arms race by limiting naval construction. It was negotiated at the Washington N ...

(the ''Washington Naval Treaty''), the

Nine-Power Treaty

The Nine-Power Treaty ( Japanese: or Nine-Power Agreement () was a 1922 treaty affirming the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Republic of China as per the Open Door Policy. The Nine-Power Treaty was signed on 6 February 1922 by all o ...

, and a number of smaller agreements. These treaties preserved peace during the 1920s but were not renewed, as the world scene turned increasingly negative after 1930.

The Dawes plan was the American solution to the crisis of reparations, in which France was demanding more money than Germany was willing to pay, so France occupied the key industrial Ruhr district of Germany with its army. The crisis was solved by a compromise brokered by the United States in the form of the

Dawes Plan

The Dawes Plan (as proposed by the Dawes Committee, chaired by Charles G. Dawes) was a plan in 1924 that successfully resolved the issue of World War I reparations that Germany had to pay. It ended a crisis in European diplomacy following Wor ...

in 1924. This plan, sponsored by American

Charles G. Dawes

Charles Gates Dawes (August 27, 1865 – April 23, 1951) was an American banker, general, diplomat, composer, and Republican politician who was the 30th vice president of the United States from 1925 to 1929 under Calvin Coolidge. He was a co-rec ...

, set out a new financial scheme. New York banks loaned Germany hundreds of millions of dollars that it used to pay reparations and rebuild its heavy industry. France, Britain and the other countries used the reparations in turn to repay wartime loans they received from the United States. By 1928 Germany called for a new payment plan, resulting in the

Young Plan

The Young Plan was a program for settling Germany's World War I reparations. It was written in August 1929 and formally adopted in 1930. It was presented by the committee headed (1929–30) by American industrialist Owen D. Young, founder and for ...

that established the German reparation requirements at 112 billion marks () and created a schedule of payments that would see Germany complete payments by 1988. With the collapse of the German economy in 1931, reparations were

suspended for a year and in 1932 during the

Lausanne Conference they were suspended for an indefinite period. After 1953 West Germany

paid the entire remaining balance.

Mexico

Since the turmoil of the Mexican revolution had died down, the Harding administration was prepared to normalize relations with Mexico. Between 1911 and 1920 American imports from Mexico increased from $57,000,000 to $179,000,000 and exports from $61,000,000 to $208,000,000. Commerce Secretary

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gre ...

took the lead in order to promote trade and investments other than in oil and land, which had long dominated bilateral economic ties. President

Álvaro Obregón

Álvaro Obregón Salido (; 17 February 1880 – 17 July 1928) better known as Álvaro Obregón was a Sonoran-born general in the Mexican Revolution. A pragmatic centrist, natural soldier, and able politician, he became the 46th President of Me ...

assured Americans that they would be protected in Mexico, and Mexico was granted recognition in 1923. A major crisis erupted in the mid-1930s when the Mexican government expropriated millions of acres of land from hundreds of American property owners as part of President

Lázaro Cárdenas

Lázaro Cárdenas del Río (; 21 May 1895 – 19 October 1970) was a Mexican army officer and politician who served as president of Mexico from 1934 to 1940.

Born in Jiquilpan, Michoacán, to a working-class family, Cárdenas joined the Me ...

's land redistribution program. No compensation was provided to the American owners. The emerging threat of the Second World War forced the United States to agree to a compromise solution. The US negotiated an agreement with President

Manuel Avila Camacho

Manuel may refer to:

People

* Manuel (name)

* Manuel (Fawlty Towers), a fictional character from the sitcom ''Fawlty Towers''

* Charlie Manuel, manager of the Philadelphia Phillies

* Manuel I Komnenos, emperor of the Byzantine Empire

* Manu ...

that amounted to a military alliance.

Intervention ends in Latin America

Small-scale military interventions continued after 1921 as the

Banana Wars

The Banana Wars were a series of conflicts that consisted of military occupation, police action, and intervention by the United States in Central America and the Caribbean between the end of the Spanish–American War in 1898 and the inceptio ...

tapered off. The Hoover administration began a goodwill policy and withdrew all military forces. President Roosevelt announced the "

Good Neighbor Policy

The Good Neighbor policy ( ) was the foreign policy of the administration of United States President Franklin Roosevelt towards Latin America. Although the policy was implemented by the Roosevelt administration, President Woodrow Wilson had prev ...

" by which the United States would no longer intervene to promote good government, but would accept whatever governments were locally chosen. His Secretary of State

Cordell Hull

Cordell Hull (October 2, 1871July 23, 1955) was an American politician from Tennessee and the longest-serving U.S. Secretary of State, holding the position for 11 years (1933–1944) in the administration of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt ...

endorsed article 8 of the 1933 Montevideo Convention on Rights and Duties of States; it provides that "no state has the right to intervene in the internal or external affairs of another".

Isolationism in 1930s

In the 1930s, the United States entered the period of deep isolationism, rejecting international conferences, and focusing moment mostly on reciprocal tariff agreements with smaller countries of Latin America.

Coming of war: 1937–1941

President Roosevelt tried to avoid repeating what he saw as Woodrow Wilson's mistakes in World War I. He often made exactly the opposite decision. Wilson called for neutrality in thought and deed, while Roosevelt made it clear his administration strongly favored Britain and China. Unlike the loans in World War I, the United States made large-scale grants of military and economic aid to the Allies through

Lend-Lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (), was a policy under which the United States supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and other Allied nations with food, oil, ...

, with little expectation of repayment. Wilson did not greatly expand war production before the declaration of war; Roosevelt did. Wilson waited for the declaration to begin a draft; Roosevelt started one in 1940. Wilson never made the United States an official ally but Roosevelt did. Wilson never met with the top Allied leaders but Roosevelt did. Wilson proclaimed independent policy, as seen in the 14 Points, while Roosevelt always had a collaborative policy with the Allies. In 1917, United States declared war on Germany; in 1941, Roosevelt waited until the enemy attacked at Pearl Harbor. Wilson refused to collaborate with the Republicans; Roosevelt named leading Republicans to head the War Department and the Navy Department. Wilson let General John J. Pershing make the major military decisions; Roosevelt made the major decisions in his war including the "

Europe first Europe first, also known as Germany first, was the key element of the grand strategy agreed upon by the United States and the United Kingdom during World War II. According to this policy, the United States and the United Kingdom would use the prepon ...

" strategy. He rejected the idea of an armistice and demanded unconditional surrender. Roosevelt often mentioned his role in the Wilson administration, but added that he had profited more from Wilson's errors than from his successes.

Great Depression

Historians and economists still have not agreed on the

causes of the Great Depression

The causes of the Great Depression in the early 20th century in the United States have been extensively discussed by economists and remain a matter of active debate. They are part of the larger debate about economic crises and recessions. The sp ...

, but there is general agreement that it began in the United States in late 1929 and was either started or worsened by "

Black Thursday

Black Thursday is a term used to refer to typically negative, notable events that have occurred on a Thursday. It has been used in the following cases:

*6 February 1851, bushfires in Victoria, Australia.

*18 September 1873, during the Panic of ...

," the

stock market crash

A stock market crash is a sudden dramatic decline of stock prices across a major cross-section of a stock market, resulting in a significant loss of paper wealth. Crashes are driven by panic selling and underlying economic factors. They often foll ...

of Thursday, October 24, 1929. Sectors of the US economy had been showing some signs of distress for months before October 1929. Business inventories of all types were three times as large as they had been a year before (an indication that the public was not buying products as rapidly as in the past), and other signposts of economic health—freight carloads, industrial production, and wholesale prices—were slipping downward.

The events in the United States triggered a worldwide

depression, which led to

deflation

In economics, deflation is a decrease in the general price level of goods and services. Deflation occurs when the inflation rate falls below 0% (a negative inflation rate). Inflation reduces the value of currency over time, but sudden deflatio ...

and a great increase in

unemployment

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work during the refe ...

. In the United States between 1929 and 1933, unemployment soared from 3% of the workforce to 25%, while manufacturing output collapsed by one-third. Local relief was overwhelmed. Unable to support their families, many unemployed men deserted (often going to "

Hooverville A "Hooverville" was a shanty town built during the Great Depression by the homeless in the United States. They were named after Herbert Hoover, who was President of the United States during the onset of the Depression and was widely blamed for ...

s") so the meager relief supplies their families received would stretch further. For many, their next meal was found at a

soup kitchen

A soup kitchen, food kitchen, or meal center, is a place where food is offered to the hungry usually for free or sometimes at a below-market price (such as via coin donations upon visiting). Frequently located in lower-income neighborhoods, soup ...

, if at all.

Adding to the misery of the times,

drought

A drought is defined as drier than normal conditions.Douville, H., K. Raghavan, J. Renwick, R.P. Allan, P.A. Arias, M. Barlow, R. Cerezo-Mota, A. Cherchi, T.Y. Gan, J. Gergis, D. Jiang, A. Khan, W. Pokam Mba, D. Rosenfeld, J. Tierney, an ...

arrived in the

Great Plains

The Great Plains (french: Grandes Plaines), sometimes simply "the Plains", is a broad expanse of flatland in North America. It is located west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, a ...

. Decades of bad farming practices caused the topsoil to erode, and combined with the weather conditions (the 1930s was the overall warmest decade of the 20th century in North America) caused an ecological disaster. The dry soil was lifted by wind and blown into huge dust storms that blanketed entire towns, a phenomenon that continued for several years. Those who had lost their homes and livelihoods in the

Dust Bowl

The Dust Bowl was a period of severe dust storms that greatly damaged the ecology and agriculture of the American and Canadian prairies during the 1930s. The phenomenon was caused by a combination of both natural factors (severe drought) a ...

were lured westward by advertisements for work put out by

agribusiness

Agribusiness is the industry, enterprises, and the field of study of value chains in agriculture and in the bio-economy,

in which case it is also called bio-business or bio-enterprise.

The primary goal of agribusiness is to maximize profit w ...

in western states, such as California. The migrants came to be called

Okies,

Arkies, and other derogatory names as they flooded the labor supply of the agricultural fields, driving down wages, pitting desperate workers against each other. They came into competition with Mexican laborers, who were deported en masse back to their home country.

In the South, the fragile economy collapsed further. To escape, rural workers and

sharecropper

Sharecropping is a legal arrangement with regard to agricultural land in which a landowner allows a tenant to use the land in return for a share of the crops produced on that land.

Sharecropping has a long history and there are a wide range ...

s migrated north by train, both black and white. By 1940 they were attracted by booming munitions factories in plants in the

Great Lakes region

The Great Lakes region of North America is a binational Canadian–American region that includes portions of the eight U.S. states of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin along with the Canadian p ...

Nationwide, farmers had been experiencing depressed market conditions for their crops and goods since the end of World War I. Many family farms that had been mortgaged during the 1920s to provide money to "get through until better times" were

foreclosed

Foreclosure is a legal process in which a lender attempts to recover the balance of a loan from a borrower who has stopped making payments to the lender by forcing the sale of the asset used as the collateral for the loan.

Formally, a mortg ...

when farmers were unable to make payments.

The New Deal

In the United States, upon accepting

Democratic nomination for president in 1932,

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

promised "a new deal for the American people," a phrase that has endured as a label for his administration and its many domestic achievements.

The Republicans, blamed for the Depression, or at least for lack of an adequate response to it, were easily defeated by Roosevelt in

1932

Events January

* January 4 – The British authorities in India arrest and intern Mahatma Gandhi and Vallabhbhai Patel.

* January 9 – Sakuradamon Incident: Korean nationalist Lee Bong-chang fails in his effort to assassinate Emperor Hir ...

.

Roosevelt entered office with no single ideology or plan for dealing with the depression. The "new deal" was often contradictory, pragmatic, and experimental. What some considered incoherence of the New Deal's ideology, however, was the presence of several competing ones, based on programs and ideas not without precedents in the American political tradition. The New Deal consisted of many different efforts to end the Great Depression and reform the American economy. Many of them failed, but there were enough successes to establish it as the most important episode of the 20th century in the creation of the modern American state.

The desperate economic situation, combined with the substantial Democratic victories in the 1932 Congressional elections, gave Roosevelt unusual influence over Congress in the "First Hundred Days" of his administration. He used his leverage to win rapid passage of a series of measures to create welfare programs and regulate the banking system, stock market, industry and agriculture.

"Bank holiday" and Emergency Banking Act

On March 6, two days after taking office, Roosevelt issued a proclamation closing all American banks for four days until Congress could meet in a special session. Ordinarily, such an action would cause widespread panic. But the action created a general sense of relief. First, many states had already closed down the banks before March 6. Second, Roosevelt astutely and euphemistically described it as a "bank holiday." And third, the action demonstrated that the federal government was stepping in to stop the alarming pattern of bank failures.

Three days later, President Roosevelt sent to Congress the

Emergency Banking Act

__NOTOC__

The Emergency Banking Act (EBA) (the official title of which was the Emergency Banking Relief Act), Public Law 73-1, 48 Stat. 1 (March 9, 1933), was an act passed by the United States Congress in March 1933 in an attempt to stabilize t ...

, a generally conservative bill, drafted in large part by holdovers from the Hoover administration, designed primarily to protect large banks from being dragged down by the failing smaller ones. The bill provided for

United States Treasury Department

The Department of the Treasury (USDT) is the national treasury and finance department of the federal government of the United States, where it serves as an executive department. The department oversees the Bureau of Engraving and Printing and ...

inspection of all banks before they would be allowed to reopen, for federal assistance to tottering large institutions, and for a thorough reorganization of those in greatest difficulty. A confused and frightened Congress passed the bill within four hours of its introduction. Three-quarters of the banks in the

Federal Reserve System

The Federal Reserve System (often shortened to the Federal Reserve, or simply the Fed) is the central banking system of the United States of America. It was created on December 23, 1913, with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, after ...

reopened within the next three days, and $1 billion in hoarded currency and gold flowed back into them within a month. The immediate banking crisis was over. The

Glass–Steagall Act established various provisions designed to prevent another Great Depression from happening again. These included separating investment from savings and loan banks and forbidding the purchase of stock with no money down. Roosevelt also removed the currency of the United States from the gold standard, which was widely blamed for limiting the money supply and causing deflation, although the silver standard remained until 1971. Private ownership of gold bullion and certificates was banned and would remain so until 1975.

Economy Act

On the morning after passage of the Emergency Banking Act, Roosevelt sent to Congress the

Economy Act

The Economy Act of 1933, officially titled the Act of March 20, 1933 (ch. 3, ; ), is an Act of Congress that cut the salaries of federal workers and reduced benefit payments to veterans, moves intended to reduce the federal deficit in the United St ...

, which was designed to convince the public, and moreover the business community, that the federal government was in the hands of no radical. The act proposed to balance the federal budget by cutting the salaries of government employees and reducing pensions to veterans by as much as 15%.

Otherwise, Roosevelt warned, the nation faced a $1 billion deficit. The bill revealed clearly what Roosevelt had always maintained: that he was as much of a fiscal conservative at heart as his predecessor was. And like the banking bill, it passed through Congress almost instantly—despite heated protests by some congressional progressives.

Farm programs

The celebrated First Hundred Days of the new administration also produced a federal program to protect American farmers from the uncertainties of the market through subsidies and production controls, the

Agricultural Adjustment Act

The Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) was a United States federal law of the New Deal era designed to boost agricultural prices by reducing surpluses. The government bought livestock for slaughter and paid farmers subsidies not to plant on par ...

(AAA), which Congress passed in May 1933. The AAA reflected the desires of leaders of various farm organizations and Roosevelt's

Secretary of Agriculture

The United States secretary of agriculture is the head of the United States Department of Agriculture. The position carries similar responsibilities to those of agriculture ministers in other governments.

The department includes several organi ...

,

Henry A. Wallace

Henry Agard Wallace (October 7, 1888 – November 18, 1965) was an American politician, journalist, farmer, and businessman who served as the 33rd vice president of the United States, the 11th U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, and the 10th U.S. ...

.

Relative farm incomes had been falling for decades. The AAA included reworkings of many long-touted programs for agrarian relief, which had been demanded for decades. The most important provision of the AAA was the provision for crop reductions—the "domestic allotment" system, which was intended to raise prices for farm commodities by preventing surpluses from flooding the market and depressing prices further. The most controversial component of the system was the destruction in summer 1933 of growing crops and newborn livestock that exceeded the allotments. They had to be destroyed to get the plan working. However, gross farm incomes increased by half in the first three years of the New Deal and the relative position of farmers improved significantly for the first time in twenty years. Urban

food prices

Food prices refer to the average price level for food across countries, regions and on a global scale. Food prices have an impact on producers and consumers of food.

Price levels depend on the food production process, including food marketing ...

went up slightly, because the cost of the grains was only a small fraction of what the consumer paid. Conditions improved for the great majority of commercial farmers by 1936. The income of the farm sector almost doubled from $4.5 billion in 1932 to $8.9 billion in 1941 just before the war. Meanwhile, food prices rose 22% in nine years from an index of 31.5 in 1932, to 38.4 in 1941.

However, rural America contained many isolated farmers scratching out a subsistence income. The new deal set up programs such as the

Resettlement Administration

The Resettlement Administration (RA) was a New Deal U.S. federal agency created May 1, 1935. It relocated struggling urban and rural families to communities planned by the federal government. On September 1, 1937, it was succeeded by the Farm S ...

and the

Farm Security Administration

The Farm Security Administration (FSA) was a New Deal agency created in 1937 to combat rural poverty during the Great Depression in the United States. It succeeded the Resettlement Administration (1935–1937).

The FSA is famous for its small but ...

to help them, but was very reluctant to help them buy farms.

'Alphabet soup'

Roosevelt also created an ''

alphabet soup'' of new federal regulatory agencies such as the

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to oversee the stock market and a reform of the banking system that included the

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) is one of two agencies that supply deposit insurance to depositors in American depository institutions, the other being the National Credit Union Administration, which regulates and insures cr ...

(FDIC) to establish a system of insurance for deposits.

The most successful initiatives in alleviating the miseries of the Great Depression were a series of relief measures to aid some of the 15 million unemployed Americans, among them the

Civilian Conservation Corps

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was a voluntary government unemployment, work relief program that ran from 1933 to 1942 in the United States for unemployed, unmarried men ages 18–25 and eventually expanded to ages 17–28. The CCC was a ...

, the

Civil Works Administration

The Civil Works Administration (CWA) was a short-lived job creation program established by the New Deal during the Great Depression in the United States to rapidly create mostly manual-labor jobs for millions of unemployed workers. The jobs were ...

, and the

Federal Emergency Relief Administration

The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) was a program established by President Franklin Roosevelt in 1933, building on the Hoover administration's Emergency Relief and Construction Act. It was replaced in 1935 by the Works Progress Admi ...

.

The early New Deal also began the

Tennessee Valley Authority

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) is a federally owned electric utility corporation in the United States. TVA's service area covers all of Tennessee, portions of Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky, and small areas of Georgia, North Carolin ...

, an unprecedented experiment in flood control, public power, and regional planning.

Second New Deal

The

Second New Deal

The Second New Deal is a term used by historians to characterize the second stage, 1935–36, of the New Deal programs of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The most famous laws included the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act, the Banking Act, the ...

(1935–36) was the second stage of the

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Con ...

programs. President

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

announced his main goals in January 1935: improved use of national resources, security against old age, unemployment and illness, and

slum clearance

Slum clearance, slum eviction or slum removal is an urban renewal strategy used to transform low income settlements with poor reputation into another type of development or housing. This has long been a strategy for redeveloping urban communities; ...

, as well as a national welfare program (the WPA) to replace state relief efforts. The most important programs included

Social Security

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifical ...

, the

National Labor Relations Act

The National Labor Relations Act of 1935, also known as the Wagner Act, is a foundational statute of United States labor law that guarantees the right of private sector employees to organize into trade unions, engage in collective bargaining, and ...

("Wagner Act"), the Banking Act,

rural electrification

Rural electrification is the process of bringing electrical power to rural and remote areas. Rural communities are suffering from colossal market failures as the national grids fall short of their demand for electricity. As of 2017, over 1 billion ...

, and