The history of the United Kingdom began in the early eighteenth century with the

Treaty of Union

The Treaty of Union is the name usually now given to the treaty which led to the creation of the new state of Great Britain, stating that the Kingdom of England (which already included Wales) and the Kingdom of Scotland were to be "United i ...

and

Acts of Union. The core of the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

as a unified state came into being in 1707 with the

political union

A political union is a type of political entity which is composed of, or created from, smaller polities, or the process which achieves this. These smaller polities are usually called federated states and federal territories in a federal govern ...

of the kingdoms of

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

and

Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, into a new unitary state called

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

. Of this new

state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

of Great Britain, the historian

Simon Schama

Sir Simon Michael Schama (; born 13 February 1945) is an English historian specialising in art history, Dutch history, Jewish history, and French history. He is a University Professor of History and Art History at Columbia University.

He fi ...

said:

The

Act of Union 1800

The Acts of Union 1800 (sometimes incorrectly referred to as a single 'Act of Union 1801') were parallel acts of the Parliament of Great Britain and the Parliament of Ireland which united the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Irela ...

added the

Kingdom of Ireland

The Kingdom of Ireland ( ga, label=Classical Irish, an Ríoghacht Éireann; ga, label= Modern Irish, an Ríocht Éireann, ) was a monarchy on the island of Ireland that was a client state of England and then of Great Britain. It existed from ...

to create the

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was a sovereign state in the British Isles that existed between 1801 and 1922, when it included all of Ireland. It was established by the Acts of Union 1800, which merged the Kingdom of Grea ...

.

The first decades were marked by

Jacobite risings

, war =

, image = Prince James Francis Edward Stuart by Louis Gabriel Blanchet.jpg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = James Francis Edward Stuart, Jacobite claimant between 1701 and 1766

, active ...

which ended with defeat for the Stuart cause at the

Battle of Culloden

The Battle of Culloden (; gd, Blàr Chùil Lodair) was the final confrontation of the Jacobite rising of 1745. On 16 April 1746, the Jacobite army of Charles Edward Stuart was decisively defeated by a British government force under Prince Wi ...

in 1746. In 1763,

victory in the Seven Years' War led to the growth of the

First British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts ...

. With defeat by the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

,

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

in the

War of American Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, Great Britain lost its 13 American colonies and rebuilt a

Second British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts ...

based in Asia and Africa. As a result,

British culture

British culture is influenced by the combined nations' history; its historically Christian religious life, its interaction with the cultures of Europe, the traditions of England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland and the impact of the British Empire ...

, and its technological, political, constitutional, and linguistic influence, became worldwide. Politically the central event was the

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

and its Napoleonic aftermath from 1793 to 1815, which British elites saw as a profound threat, and worked energetically to form multiple coalitions that finally defeated Napoleon in 1815. The

Tories

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

, who came to power in 1783, remained in power (with a short interruption) until 1830. Forces of reform, often emanating from the Evangelical religious elements, opened decades of political reform that broadened the ballot, and opened the economy to free trade. The outstanding political leaders of the 19th century included

Palmerston Palmerston may refer to:

People

* Christie Palmerston (c. 1851–1897), Australian explorer

* Several prominent people have borne the title of Viscount Palmerston

** Henry Temple, 1st Viscount Palmerston (c. 1673–1757), Irish nobleman and ...

,

Disraeli,

Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-cons ...

, and

Salisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of ...

. Culturally, the

Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwa ...

was a time of prosperity and dominant middle-class virtues when Britain dominated the world economy and

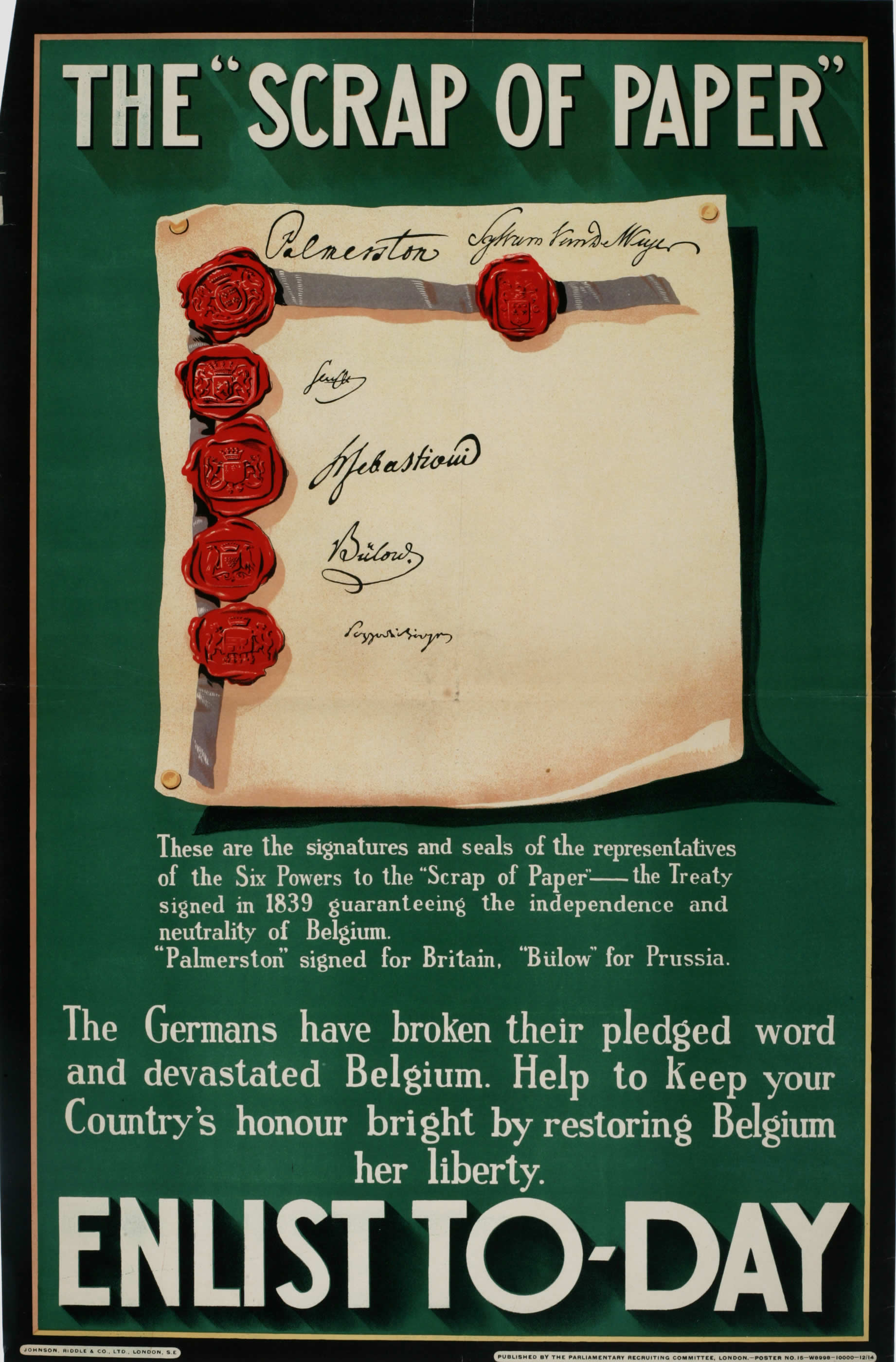

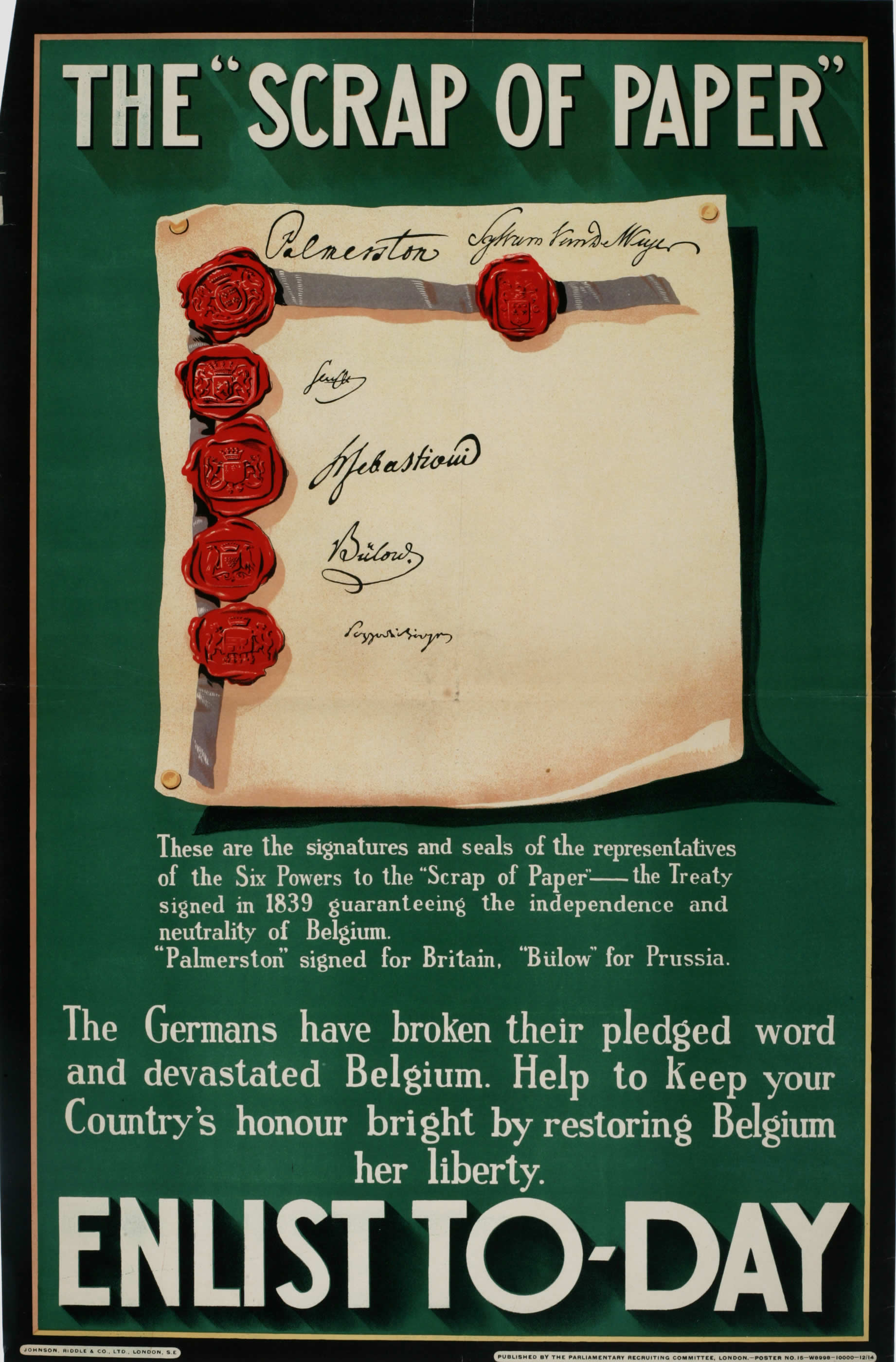

maintained a generally peaceful century from 1815 to 1914. The

First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

(1914–1918), with Britain in alliance with France,

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

and the United States, was a furious but ultimately successful total war with

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

. The resulting

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

was a favourite project in

Interwar Britain. However, while the Empire remained strong, as did the

London financial markets, the British industrial base began to slip behind Germany and, especially, the United States. Sentiments for peace were so strong that the nation supported appeasement of

Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

's Germany in the late 1930s, until the Nazi invasion of

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

in 1939 started the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. In the Second World War, the Soviet Union and the US joined the UK as

the main Allied powers.

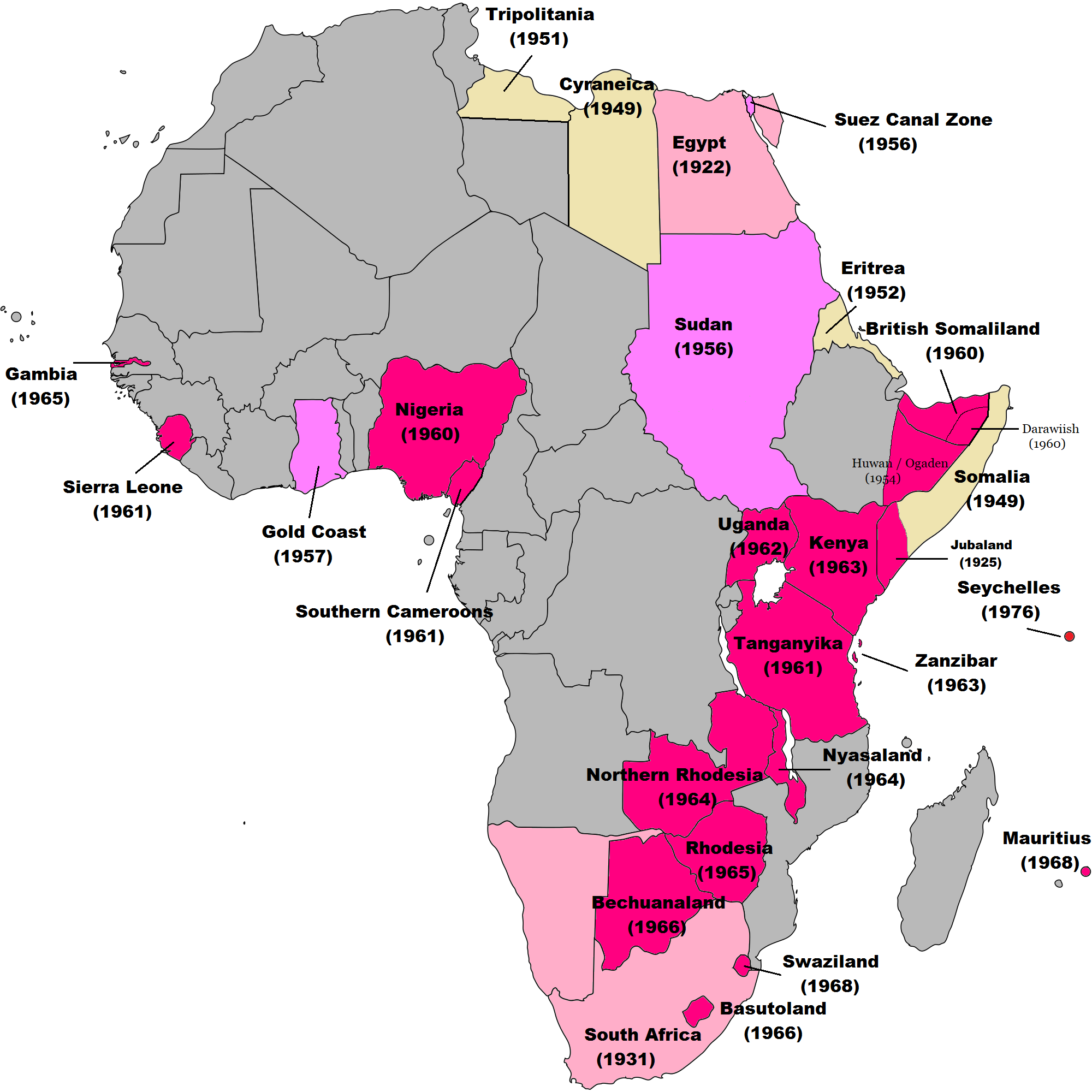

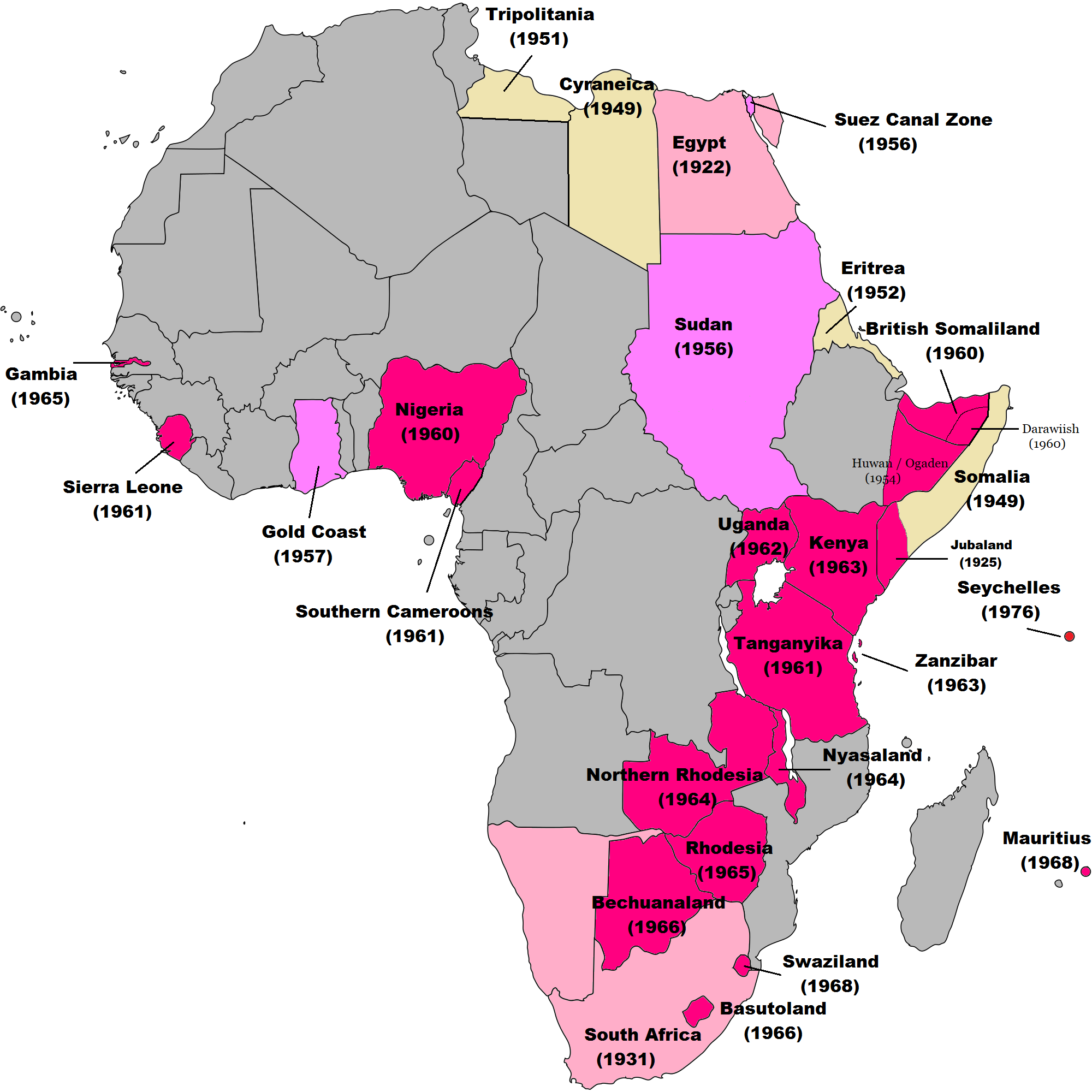

Britain was no longer a military or economic superpower, as seen in the

Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

of 1956. Britain no longer had the wealth to maintain an empire, so it granted independence to almost all its possessions. The new states typically joined the

Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the C ...

. The postwar years saw great hardships, alleviated somewhat by large-scale financial aid from the United States, and some from

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

. Prosperity returned in the 1950s. Meanwhile, from 1945 to 1950, the

Labour Party built a welfare state, nationalized many industries, and created the

National Health Service

The National Health Service (NHS) is the umbrella term for the publicly funded healthcare systems of the United Kingdom (UK). Since 1948, they have been funded out of general taxation. There are three systems which are referred to using the " ...

. The UK took a strong stand against

Communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

expansion after 1945, playing a major role in the

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

and the formation of

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two N ...

as an anti-Soviet military alliance with West Germany, France, the United States, Canada and smaller countries.

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two N ...

remains a powerful military coalition. The UK has been a leading member of the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

since its founding, as well as numerous other international organizations. In the 1990s,

neoliberalism

Neoliberalism (also neo-liberalism) is a term used to signify the late 20th century political reappearance of 19th-century ideas associated with free-market capitalism after it fell into decline following the Second World War. A prominent f ...

led to the privatisation of nationalised industries and significant deregulation of business affairs. London's status as a world financial hub grew continuously. Since the 1990s, large-scale

devolution movements in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales have decentralised political decision-making. Britain has moved back and forth on its economic relationships with Western Europe. It joined the

European Economic Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organization created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lis ...

in 1973, thereby weakening economic ties with its Commonwealth. However, the

Brexit

Brexit (; a portmanteau of "British exit") was the Withdrawal from the European Union, withdrawal of the United Kingdom (UK) from the European Union (EU) at 23:00 Greenwich Mean Time, GMT on 31 January 2020 (00:00 1 February 2020 Central Eur ...

referendum in 2016 committed the UK to leave the

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are located primarily in Europe, Europe. The union has a total area of ...

, which it did in 2020.

In 1922, 26 counties of Ireland seceded to become the

Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between ...

; a day later,

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label=Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is #Descriptions, variously described as ...

seceded from the Free State and returned to the United Kingdom. In 1927, the United Kingdom changed its formal title to the ''United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland,'' usually shortened to ''

Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

'' and (after 1945) to the ''United Kingdom'' or ''UK''.

18th century

Birth of the Union

The

Kingdom of Great Britain

The Kingdom of Great Britain (officially Great Britain) was a sovereign country in Western Europe from 1 May 1707 to the end of 31 December 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, wh ...

came into being on 1 May 1707, as a result of the

political union

A political union is a type of political entity which is composed of, or created from, smaller polities, or the process which achieves this. These smaller polities are usually called federated states and federal territories in a federal govern ...

of the

Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

On ...

(which included

Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

) and the

Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland (; , ) was a sovereign state in northwest Europe traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain, sharing a l ...

under the

Treaty of Union

The Treaty of Union is the name usually now given to the treaty which led to the creation of the new state of Great Britain, stating that the Kingdom of England (which already included Wales) and the Kingdom of Scotland were to be "United i ...

. This combined the two kingdoms into a single kingdom and merged the two parliaments into a single

parliament of Great Britain

The Parliament of Great Britain was formed in May 1707 following the ratification of the Acts of Union by both the Parliament of England and the Parliament of Scotland. The Acts ratified the treaty of Union which created a new unified Kingdo ...

.

Queen Anne became the first monarch of the new Great Britain. Although now a single kingdom, certain institutions of Scotland and England remained separate, such as

Scottish and

English law

English law is the common law legal system of England and Wales, comprising mainly criminal law and civil law, each branch having its own courts and procedures.

Principal elements of English law

Although the common law has, historically, b ...

; and the

Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Reformation of 1560, when it split from the Catholic Church ...

and the

Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of t ...

Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

. England and Scotland each also continued to have their own system of education.

Meanwhile, the

War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

against France (1701–1714) was underway. It see-sawed back and forth until a more peace-minded government came to power in London and the treaties of

Utrecht

Utrecht ( , , ) is the fourth-largest city and a municipality of the Netherlands, capital and most populous city of the province of Utrecht. It is located in the eastern corner of the Randstad conurbation, in the very centre of mainland Net ...

and

Rastadt ended the war. British historian

G. M. Trevelyan argues:

Hanoverian kings

The Stuart line died with Anne in 1714, although a die-hard faction with French support supported pretenders. The Elector of Hanover became king as

George I. He paid more attention to Hanover and surrounded himself with Germans, making him an unpopular king. He did, however, build up the army and created a more stable political system in Britain and helped bring peace to northern Europe. Jacobite factions seeking a Stuart restoration remained strong; they instigated

a revolt in 1715–1716. The son of

James II planned to invade England, but before he could do so,

John Erskine, Earl of Mar, launched an invasion from Scotland, which was easily defeated.

George II enhanced the stability of the constitutional system, with a government run by

Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford, (26 August 1676 – 18 March 1745; known between 1725 and 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole) was a British statesman and Whig politician who, as First Lord of the Treasury, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and Lea ...

during the period 1730–1742. He built up the

First British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts ...

, strengthening the colonies in the Caribbean and North America. In coalition with the rising power Prussia, the United Kingdom defeated France in the

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754 ...

(1756–1763), and won full control of Canada.

George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

never visited Hanover, and spoke English as his first language. Reviled by Americans as a tyrant and the instigator of the American War of Independence, he was insane off and on after 1788, and his eldest son served as regent. He was the last king to dominate government and politics, and his long reign is noted for losing the first British Empire in the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

(1783), as France sought revenge for its defeat in the Seven Years' War by aiding the Americans. The reign was notable for the building of a second empire based in India, Asia and Africa, the beginnings of the industrial revolution that made Britain an economic powerhouse, and above all the life and death struggle with the French, in the

French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted France against Britain, Austria, Pruss ...

1793–1802, which ended inconclusively with a short truce, and the epic

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fre ...

(1803–1815), which ended with the decisive defeat of Napoleon.

South Sea Bubble

Entrepreneurs gradually extended the range of their business around the globe. The

South Sea Bubble

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

was a business enterprise that exploded in scandal. The South Sea Company was a joint-stock company in London. Its ostensible object was to grant trade monopolies in South America; but its actual purpose was to renegotiate previous high-interest government loans amounting to £31 million through

market manipulation

In economics and finance, market manipulation is a type of market abuse where there is a deliberate attempt to interfere with the free and fair operation of the market; the most blatant of cases involve creating false or misleading appearances ...

and speculation. It raised money four times in 1720 by issuing stock, which was purchased by about 8,000 investors. The share price kept soaring every day, from £130 a share to £1,000, with insiders making huge paper profits. The Bubble collapsed overnight, ruining many speculators. Investigations showed bribes had reached into high places—even to the king.

Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford, (26 August 1676 – 18 March 1745; known between 1725 and 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole) was a British statesman and Whig politician who, as First Lord of the Treasury, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and Lea ...

managed to wind it down with minimal political and economic damage, although some losers fled to exile or committed suicide.

Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole is now generally regarded as the first Prime Minister, from, 1719–1742, and indeed he invented the role. The term was applied to him by friends and foes alike by 1727. Historian Clayton Roberts summarizes his new functions:

Moralism, benevolence and hypocrisy

Hypocrisy became a major topic in English political history in the early 18th century. The

Toleration Act 1689

The Toleration Act 1688 (1 Will & Mary c 18), also referred to as the Act of Toleration, was an Act of the Parliament of England. Passed in the aftermath of the Glorious Revolution, it received royal assent on 24 May 1689.

The Act allowed for f ...

allowed for certain rights for religious minorities, but Protestant

Nonconformists (such as Congregationalists and Baptists) were still deprived of important rights, such as the right to hold office. Nonconformists who wanted to hold office ostentatiously took the Anglican sacrament once a year in order to avoid the restrictions. High Church Anglicans were outraged. They outlawed what they called "occasional conformity" in 1711 with the

Occasional Conformity Act 1711

The Occasional Conformity Act (10 Anne c. 6), also known as the Occasional Conformity Act 1711 or the Toleration Act 1711, was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain which passed on 20 December 1711. Previous Occasional Conformity bills ha ...

. In the political controversies using sermons, speeches, and pamphlet wars, both high churchmen and Nonconformists attacked their opponents as insincere and hypocritical, as well as dangerously zealous, in contrast to their own moderation. This campaign of moderation versus zealotry peaked in 1709 during the impeachment trial of high church preacher

Henry Sacheverell. Historian Mark Knights argues that by its very ferocity, the debate may have led to more temperate and less hypercharged political discourse. "Occasional conformity" was restored by the Whigs when they returned to power in 1719.

English author

Bernard Mandeville

Bernard Mandeville, or Bernard de Mandeville (; 15 November 1670 – 21 January 1733), was an Anglo-Dutch philosopher, political economist and satirist. Born in Rotterdam, Netherlands, he lived most of his life in England and used English for ...

's famous "

Fable of the Bees" (1714) explored the nature of hypocrisy in contemporary European society. On one hand, Mandeville was a "moralist" heir to the French Augustinianism of the previous century, viewing sociability as a mere mask for vanity and pride. On the other, he was a "materialist" who helped found modern economics. He tried to demonstrate the universality of human appetites for corporeal pleasures. He argued that the efforts of self-seeking entrepreneurs are the basis of emerging commercial and industrial society, a line of thought that influenced

Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——� ...

and 19th-century

Utilitarianism

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different chara ...

. A tension arose between these two approaches concerning the relative power of norms and interests, the relationship between motives and behaviour, and the historical variability of human cultures.

From around 1750 to 1850, Whig aristocrats in England boasted of their special benevolence for the common people. They claimed to be guiding and counselling reform initiatives to prevent the outbreaks of popular discontent that caused instability and revolution across Europe. However Tory and radical critics accused the Whigs of hypocrisy—alleging they were deliberately using the slogans of reform and democracy to boost themselves into power while preserving their precious aristocratic exclusiveness. Historian L.G. Mitchell defends the Whigs, pointing out that thanks to them radicals always had friends at the centre of the political elite, and thus did not feel as marginalised as in most of Europe. He points out that the debates on the 1832 Reform Bill showed that reformers would indeed receive a hearing at parliamentary level with a good chance of success. Meanwhile, a steady stream of observers from the Continent commented on the English political culture. Liberal and radical observers noted the servility of the English lower classes in the early 19th century, the obsession everyone had with rank and title, the extravagance of the aristocracy, a supposed anti-intellectualism, and a pervasive hypocrisy that extended into such areas as social reform. There were not so many conservative visitors. They praised the stability of English society, its ancient constitution, and reverence for the past; they ignored the negative effects of industrialisation.

Historians have explored crimes and vices of England's upper classes, especially duelling, suicide, adultery and gambling. They were tolerated by the same courts that executed thousands of poor men and boys for lesser offenses. No aristocrat was punished for killing someone in a duel. However the emerging popular press specialized in sensationalistic stories about upper-class vice, which led the middle classes to focus their critiques on a decadent aristocracy that had much more money, but much less morality than the middle class.

Warfare and finance

From 1700 to 1850, Britain was involved in 137 wars or rebellions. It maintained a relatively large and expensive

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

, along with a small standing army. When the need arose for soldiers it hired mercenaries or financed allies who fielded armies. The rising costs of warfare forced a shift in the sources of government financing, from the income from royal agricultural estates and special imposts and taxes to reliance on customs and excise taxes; and, after 1790, an income tax. Working with bankers in the city, the government raised large loans during wartime and paid them off in peacetime. The rise in taxes amounted to 20% of national income, but the private sector benefited from the increase in economic growth. The demand for war supplies stimulated the industrial sector, particularly naval supplies, munitions and textiles, which gave Britain an advantage in international trade during the postwar years.

The

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

polarised British political opinion in the 1790s, with conservatives outraged at the killing of the king, the expulsion of the nobles, and the

Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror (french: link=no, la Terreur) was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the First French Republic, First Republic, a series of massacres and numerous public Capital punishment, executions took pl ...

. Britain was at war against France almost continuously from 1793 until the final defeat of Napoleon in 1815. Conservatives castigated every radical opinion in Britain as "Jacobin" (in reference to the

leaders of the Terror), warning that radicalism threatened an upheaval of British society. The Anti-Jacobin sentiment, well expressed by

Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS">New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS/nowiki>_1729_–_9_July_1797)_was_an_NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">N ...

and

many popular writers was strongest among the landed gentry and the upper classes.

British Empire

The

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754 ...

, which began in 1756, was the first war waged on a global scale, fought in Europe, India, North America, the Caribbean, the Philippines and coastal Africa. Britain was the big winner as it enlarged its empire at the expense of France and others. France lost its role as a colonial power in North America. It ceded

New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

to Britain, putting a large, traditionalistic French-speaking Catholic element under British control. Spain ceded

Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and ...

to Britain, but it only had a few small outposts there. In India, the

Carnatic War

The Carnatic Wars were a series of military conflicts in the middle of the 18th century in India's coastal Carnatic region, a dependency of Hyderabad State, India. Three Carnatic Wars were fought between 1744 and 1763.

The conflicts involved n ...

had left France still in control of its

small enclaves but with military restrictions and an obligation to support British client states, effectively leaving the future of India to Britain.

The British victory over France in the Seven Years' War therefore left Britain as the world's dominant colonial power.

During the 1760s and 1770s, relations between the

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th centu ...

and Britain became increasingly strained, primarily because of growing anger against Parliament's repeated attempts to tax American colonists without their consent. The Americans readied their large militias, but were short of gunpowder and artillery. The British assumed falsely that they could easily suppress Patriot resistance. In 1775 the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

began. In 1776 the Patriots expelled all the royal officials and

declared the independence of the United States of America. After capturing a British invasion army in 1777, the new nation formed an alliance with France (and in turn Spain aided France), equalizing the military and naval balance and putting Britain at risk of invasion from France. The British army controlled only a handful of coastal cities in the U.S. 1780–1781 was a low point for Britain. Taxes and deficits were high, government corruption was pervasive, and the war in America was entering its sixth year with no apparent end in sight. The

Gordon Riots

The Gordon Riots of 1780 were several days of rioting in London motivated by anti-Catholic sentiment. They began with a large and orderly protest against the Papists Act 1778, which was intended to reduce official discrimination against Briti ...

erupted in London during the spring of 1780, in response to increased concessions to Catholics by Parliament. In October 1781

Lord Cornwallis surrendered his army at

Yorktown, Virginia

Yorktown is a census-designated place (CDP) in York County, Virginia. It is the county seat of York County, one of the eight original shires formed in colonial Virginia in 1682. Yorktown's population was 195 as of the 2010 census, while York Co ...

. The

Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783, formally terminating the war and recognising the independence of the United States. The peace terms were very generous to the new nation, which London hoped correctly would become a major trading partner.

The loss of the Thirteen Colonies, at the time Britain's most populous colonies, marked the transition between the "first" and "second" empires, in which Britain shifted its attention to Asia, the Pacific and later Africa.

Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——� ...

's ''

Wealth of Nations'', published in 1776, had argued that colonies were redundant, and that

free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

should replace the old

mercantilist

Mercantilism is an economic policy that is designed to maximize the exports and minimize the imports for an economy. It promotes imperialism, colonialism, tariffs and subsidies on traded goods to achieve that goal. The policy aims to reduc ...

policies that had characterised the first period of colonial expansion, dating back to the protectionism of Spain and Portugal. The growth of trade between the newly independent United States and Britain after 1783 confirmed Smith's view that political control was not necessary for economic success.

During its first 100 years of operation, the focus of the

British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

had been trade, not the building of an empire in India. Company interests turned from trade to territory during the 18th century as the Mughal Empire declined in power and the British East India Company struggled with its French counterpart, the ''

La Compagnie française des Indes orientales'', during the

Carnatic Wars

The Carnatic Wars were a series of military conflicts in the middle of the 18th century in India's coastal Carnatic region, a dependency of Hyderabad State, India. Three Carnatic Wars were fought between 1744 and 1763.

The conflicts involved n ...

of the 1740s and 1750s. The British, led by

Robert Clive

Robert Clive, 1st Baron Clive, (29 September 1725 – 22 November 1774), also known as Clive of India, was the first British Governor of the Bengal Presidency. Clive has been widely credited for laying the foundation of the British ...

, defeated the French and their Indian allies in the

Battle of Plassey

The Battle of Plassey was a decisive victory of the British East India Company over the Nawab of Bengal and his French allies on 23 June 1757, under the leadership of Robert Clive. The victory was made possible by the defection of Mir Jafar ...

, leaving the Company in control of

Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

and a major military and political power in India. In the following decades it gradually increased the size of the territories under its control, either ruling directly or indirectly via local puppet rulers under the threat of force of the

Indian Army

The Indian Army is the Land warfare, land-based branch and the largest component of the Indian Armed Forces. The President of India is the Commander-in-Chief, Supreme Commander of the Indian Army, and its professional head is the Chief of Arm ...

, 80% of which was composed of native Indian

sepoys

''Sepoy'' () was the Persian-derived designation originally given to a professional Indian infantryman, traditionally armed with a musket, in the armies of the Mughal Empire.

In the 18th century, the French East India Company and its oth ...

.

On 22 August 1770,

James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean and ...

discovered the eastern coast of Australia while on a scientific

voyage

Voyage(s) or The Voyage may refer to:

Literature

*''Voyage : A Novel of 1896'', Sterling Hayden

* ''Voyage'' (novel), a 1996 science fiction novel by Stephen Baxter

*''The Voyage'', Murray Bail

* "The Voyage" (short story), a 1921 story by ...

to the South Pacific. In 1778,

Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the 1766 natural-history expedition to Newfoundland and Labrador. He took part in Captain James ...

, Cook's botanist on the voyage, presented evidence to the government on the suitability of

Botany Bay

Botany Bay ( Dharawal: ''Kamay''), an open oceanic embayment, is located in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, south of the Sydney central business district. Its source is the confluence of the Georges River at Taren Point and the Cook ...

for the establishment of a penal settlement, and in 1787 the first shipment of

convicts

A convict is "a person found guilty of a crime and sentenced by a court" or "a person serving a sentence in prison". Convicts are often also known as "prisoners" or "inmates" or by the slang term "con", while a common label for former conv ...

set sail, arriving in 1788.

The British government had somewhat mixed reactions to the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789, and when war broke out on the Continent in 1792, it initially remained neutral. But the following January,

Louis XVI

Louis XVI (''Louis-Auguste''; ; 23 August 175421 January 1793) was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. He was referred to as ''Citizen Louis Capet'' during the four months just before he was ...

was beheaded. This combined with a threatened invasion of the Netherlands by France spurred Britain to declare war. For the next 23 years, the two nations were at war except for a short period in 1802–1803. Britain alone among the nations of Europe never submitted to or formed an alliance with France. Throughout the 1790s, the British repeatedly defeated the navies of France and its allies, but were unable to perform any significant land operations. An Anglo-Russian invasion of the Netherlands in 1799 accomplished little except the capture of the Dutch fleet.

At the threshold to the 19th century, Britain was challenged again by France under

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

, in a struggle that, unlike previous wars, represented a contest of ideologies between the two nations: the constitutional monarchy of Great Britain versus the liberal principles of the French Revolution ostensibly championed by the Napoleonic empire. It was not only Britain's position on the world stage that was threatened: Napoleon threatened invasion of Britain itself, and with it, a fate similar to the countries of continental Europe that his armies had overrun.

1800 to 1837

Union with Ireland

On 1 January 1801, the first day of the 19th century, the

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

and

Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

joined to form the

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was a sovereign state in the British Isles that existed between 1801 and 1922, when it included all of Ireland. It was established by the Acts of Union 1800, which merged the Kingdom of Grea ...

.

The legislative union of Great Britain and Ireland was brought about by the Act of Union 1800, creating the "

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was a sovereign state in the British Isles that existed between 1801 and 1922, when it included all of Ireland. It was established by the Acts of Union 1800, which merged the Kingdom of Grea ...

". The Act was passed in both the Parliament of Great Britain and the

Parliament of Ireland

The Parliament of Ireland ( ga, Parlaimint na hÉireann) was the legislature of the Lordship of Ireland, and later the Kingdom of Ireland, from 1297 until 1800. It was modelled on the Parliament of England and from 1537 comprised two ch ...

, dominated by the

Protestant Ascendancy

The ''Protestant Ascendancy'', known simply as the ''Ascendancy'', was the political, economic, and social domination of Ireland between the 17th century and the early 20th century by a minority of landowners, Protestant clergy, and members of th ...

and lacking representation of the country's Catholic population. Substantial majorities were achieved, and according to contemporary documents this was assisted by bribery in the form of the awarding of

peerage

A peerage is a legal system historically comprising various hereditary titles (and sometimes non-hereditary titles) in a number of countries, and composed of assorted noble ranks.

Peerages include:

Australia

* Australian peers

Belgium

* Be ...

s and

honours

Honour (British English) or honor (American English; see spelling differences) is the idea of a bond between an individual and a society as a quality of a person that is both of social teaching and of personal ethos, that manifests itself as a ...

to opponents to gain their votes.

Under the terms of the merger, the separate Parliaments of Great Britain and Ireland were abolished, and replaced by a united

Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprem ...

. Ireland thus became an integral part of the United Kingdom, sending around 100 MPs to the House of Commons at Westminster and 28

representative peers

In the United Kingdom, representative peers were those peers elected by the members of the Peerage of Scotland and the Peerage of Ireland to sit in the British House of Lords. Until 1999, all members of the Peerage of England held the right to ...

to the House of Lords, elected from among their number by the Irish peers themselves, except that Roman Catholic peers were not permitted to take their seats in the Lords. Part of the trade-off for the Irish Catholics was to be the granting of

Catholic Emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in the kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, and later the combined United Kingdom in the late 18th century and early 19th century, that involved reducing and removing many of the restricti ...

, which had been fiercely resisted by the all-Anglican Irish Parliament. However, this was blocked by

King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great B ...

, who argued that emancipating the Roman Catholics would breach his

Coronation Oath. The Roman Catholic hierarchy had endorsed the Union. However the decision to block Catholic Emancipation fatally undermined the appeal of the Union.

Napoleonic wars

During the

War of the Second Coalition

The War of the Second Coalition (1798/9 – 1801/2, depending on periodisation) was the second war on revolutionary France by most of the European monarchies, led by Britain, Austria and Russia, and including the Ottoman Empire, Portugal, N ...

(1799–1801), Britain occupied most of the French and Dutch colonies (the Netherlands had been a satellite of France since 1796), but tropical diseases claimed the lives of over 40,000 troops. When the Treaty of Amiens created a pause, Britain was forced to return most of the colonies. In May 1803, war was declared again. Napoleon's plans to invade Britain failed due to the inferiority of his navy, and in 1805, Lord Nelson's fleet decisively defeated the French and Spanish at

Trafalgar, which was the last significant naval action of the Napoleonic Wars.

In 1806, Napoleon issued the series of

Berlin Decree

The Berlin Decree was issued in Berlin by Napoleon on November 21, 1806, after the French success against Prussia at the Battle of Jena, which led to the Fall of Berlin (1806), Fall of Berlin. The decree was issued in response to the British Order- ...

s, which brought into effect the

Continental System

The Continental Blockade (), or Continental System, was a large-scale embargo against British trade by Napoleon Bonaparte against the British Empire from 21 November 1806 until 11 April 1814, during the Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon issued the Berli ...

. This policy aimed to weaken the British export economy closing French-controlled territory to its trade. Napoleon hoped that isolating Britain from the Continent would end its economic dominance. It never succeeded in its objective. Britain possessed the greatest industrial capacity in Europe, and its mastery of the seas allowed it to build up considerable economic strength through trade to its possessions from its rapidly expanding new Empire. Britain's naval supremacy meant that France could never enjoy the peace necessary to consolidate its control over Europe, and it could threaten neither the home islands nor the main British colonies.

The Spanish uprising in 1808 at last permitted Britain to gain a foothold on the Continent. The

Duke of Wellington

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, (1 May 1769 – 14 September 1852) was an Anglo-Irish soldier and Tory statesman who was one of the leading military and political figures of 19th-century Britain, serving twice as prime minister ...

and his army of British and Portuguese gradually pushed the French out of Spain and in early 1814, as Napoleon was being driven back in the east by the Prussians, Austrians, and Russians, Wellington invaded southern France. After Napoleon's surrender and exile to the island of Elba, peace appeared to have returned, but when he escaped back into France in 1815, the British and their allies had to fight him again. The armies of Wellington and

von Blücher defeated Napoleon once and for all at

Waterloo.

Financing the war

A key element in British success was its ability to mobilize the nation's industrial and financial resources and apply them to defeating France. With a population of 16 million Britain was barely half the size of France with 30 million. In terms of soldiers the French numerical advantage was offset by British subsidies that paid for a large proportion of the Austrian and Russian soldiers, peaking at about 450,000 in 1813. Most important, the British national output remained strong and the well-organized business sector channeled products into what the military needed. The system of smuggling finished products into the continent undermined French efforts to ruin the British economy by cutting off markets. The British budget in 1814 reached £66 million, including £10 million for the Navy, £40 million for the Army, £10 million for the Allies, and £38 million as interest on the national debt. The national debt soared to £679 million, more than double the GDP. It was willingly supported by hundreds of thousands of investors and tax payers, despite the higher taxes on land and a new income tax. The whole cost of the war came to £831 million. By contrast the French financial system was inadequate and Napoleon's forces had to rely in part on requisitions from conquered lands.

Napoleon also attempted economic warfare against Britain, especially in the

Berlin Decree

The Berlin Decree was issued in Berlin by Napoleon on November 21, 1806, after the French success against Prussia at the Battle of Jena, which led to the Fall of Berlin (1806), Fall of Berlin. The decree was issued in response to the British Order- ...

of 1806. It forbade the import of British goods into European countries allied with or dependent upon France, and installed the

Continental System

The Continental Blockade (), or Continental System, was a large-scale embargo against British trade by Napoleon Bonaparte against the British Empire from 21 November 1806 until 11 April 1814, during the Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon issued the Berli ...

in Europe. All connections were to be cut, even the mail. British merchants smuggled in many goods and the Continental System was not a powerful weapon of economic war. There was some damage to Britain, especially in 1808 and 1811, but its control of the oceans helped ameliorate the damage. Even more damage was done to the economies of France and its allies, which lost a useful trading partner. Angry governments gained an incentive to ignore the Continental System, which led to the weakening of Napoleon's coalition.

War of 1812 with United States

Simultaneous with the Napoleonic Wars, trade disputes and British impressment of American sailors led to the

War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

with the United States. The "second war of independence" for the American, although in reality it was never the British objective of conquering the former colonies, but of the conquest of the Canadian colonies by the Americans, it was little noticed in Britain, where all attention was focused on the struggle with France. The British could devote few resources to the conflict until the fall of Napoleon in 1814. American

frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed an ...

s also inflicted a series of embarrassing defeats on the British navy, which was short on manpower due to the conflict in Europe. A stepped-up war effort that year brought about some successes such as the burning of Washington, but many influential voices such as the Duke of Wellington argued that an outright victory over the US was impossible.

Peace was agreed to at the end of 1814, but

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

, unaware of this, won a great victory over the British at the

Battle of New Orleans

The Battle of New Orleans was fought on January 8, 1815 between the British Army under Major General Sir Edward Pakenham and the United States Army under Brevet Major General Andrew Jackson, roughly 5 miles (8 km) southeast of the Frenc ...

in January 1815 (news took several weeks to cross the Atlantic before the advent of steam ships). Ratification of the Treaty of Ghent ended the war in February 1815. The major result was the permanent defeat of the Indian allies the British had counted upon. The US-Canada border was demilitarised by both countries, and peaceful trade resumed, although worries of an American conquest of Canada persisted into the 1860s.

Postwar reaction: 1815–1822

The postwar era was a time of economic depression, poor harvests, growing inflation, and high unemployment among returning soldiers. As industrialisation progressed, Britain was more urban and less rural, and power shifted accordingly. The dominant Tory leadership, based in the declining rural sector, was fearful, reactionary and repressive. Tories feared the possible emergence of radicals who might be conspiring to emulate the dreaded

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

. In reality the violent radical element was small and weak; there were a handful of small conspiracies involving men with few followers and careless security; they were quickly suppressed. Techniques of repression included the suspension of Habeas Corpus in 1817 (allowing the government to arrest and hold suspects without cause or trial). Sidmouth's Gagging Acts of 1817 heavily muzzled the opposition newspapers; the reformers switched to pamphlets and sold 50,000 a week. In reaction to the

Peterloo massacre

The Peterloo Massacre took place at St Peter's Field, Manchester, Lancashire, England, on Monday 16 August 1819. Fifteen people died when cavalry charged into a crowd of around 60,000 people who had gathered to demand the reform of parliament ...

of 1819, the Liverpool government passed the "

Six Acts

Following the Peterloo Massacre on 16 August 1819, the government of the United Kingdom acted to prevent any future disturbances by the introduction of new legislation, the so-called Six Acts aimed at suppressing any meetings for the purpose of ...

" in 1819. They prohibited drills and military exercises; facilitated warrants for the search for weapons; outlawed public meetings of more than 50 people, including meetings to organize petitions; put heavy penalties on blasphemous and seditious publications; imposing a fourpenny stamp act on many pamphlets to cut down the flow on news and criticism. Offenders could be harshly punished including exile in Australia. In practice the laws were designed to deter troublemakers and reassure conservatives; they were not often used. By the end of the 1820s, along with a general economic recovery, many of these repressive laws were repealed and in 1828 new legislation guaranteed the civil rights of religious dissenters.

A weak ruler as regent (1811–1820) and king (1820–1830),

George IV

George IV (George Augustus Frederick; 12 August 1762 – 26 June 1830) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from the death of his father, King George III, on 29 January 1820, until his own death ten y ...

let his ministers take full charge of government affairs, playing a far lesser role than his father, George III. The principle now became established that the king accepts as prime minister the person who wins a majority in the House of Commons, whether the king personally favours him or not. His governments, with little help from the king, presided over victory in the Napoleonic Wars, negotiated the peace settlement, and attempted to deal with the social and economic malaise that followed. His brother

William IV

William IV (William Henry; 21 August 1765 – 20 June 1837) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 26 June 1830 until his death in 1837. The third son of George III, William succeeded h ...

ruled 1830 to 1837, but was little involved in politics. His reign saw several reforms: the

poor law

In English and British history, poor relief refers to government and ecclesiastical action to relieve poverty. Over the centuries, various authorities have needed to decide whose poverty deserves relief and also who should bear the cost of he ...

was updated,

child labour

Child labour refers to the exploitation of children through any form of work that deprives children of their childhood, interferes with their ability to attend regular school, and is mentally, physically, socially and morally harmful. Such e ...

restricted,

slavery abolished in nearly all the

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

, and, most important, the

Reform Act 1832

The Representation of the People Act 1832 (also known as the 1832 Reform Act, Great Reform Act or First Reform Act) was an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom (indexed as 2 & 3 Will. IV c. 45) that introduced major changes to the electo ...

refashioned the British electoral system.

There were no major wars until the

Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

of 1853–1856. While Prussia, Austria, and Russia, as absolute monarchies, tried to suppress liberalism wherever it might occur, the British came to terms with new ideas. Britain intervened in Portugal in 1826 to defend a constitutional government there and recognising the independence of Spain's American colonies in 1824. British merchants and financiers, and later railway builders, played major roles in the economies of most Latin American nations. The British intervened in 1827 on the side of the Greeks, who had been waging the

Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. The Greeks were later assisted by ...

against the Ottoman Empire since 1821.

Whig reforms of the 1830s

The

Whig Party recovered its strength and unity by supporting moral reforms, especially the reform of the electoral system, the abolition of slavery and emancipation of the Catholics.

Catholic emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in the kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, and later the combined United Kingdom in the late 18th century and early 19th century, that involved reducing and removing many of the restricti ...

was secured in the

Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829

The Catholic Relief Act 1829, also known as the Catholic Emancipation Act 1829, was passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom in 1829. It was the culmination of the process of Catholic emancipation throughout the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

, which removed the most substantial restrictions on Roman Catholics in Britain.

The Whigs became champions of Parliamentary reform. They made

Lord Grey prime minister 1830–1834, and the

Reform Act 1832

The Representation of the People Act 1832 (also known as the 1832 Reform Act, Great Reform Act or First Reform Act) was an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom (indexed as 2 & 3 Will. IV c. 45) that introduced major changes to the electo ...

became their signature measure. It broadened the franchise slightly and ended the system of

rotten and pocket boroughs (where elections were controlled by powerful families), and gave seats to new industrial centres. The aristocracy continued to dominate the government, the Army and Royal Navy, and high society. After parliamentary investigations demonstrated the horrors of child labour, limited reforms were passed in 1833.

Chartism

Chartism was a working-class movement for political reform in the United Kingdom that erupted from 1838 to 1857 and was strongest in 1839, 1842 and 1848. It took its name from the People's Charter of 1838 and was a national protest movement, ...

emerged after the 1832 Reform Bill failed to give the vote to the working class. Activists denounced the 'betrayal' of the working class and the 'sacrificing' of their interests by the 'misconduct' of the government. In 1838, Chartists issued the People's Charter demanding manhood suffrage, equal sized election districts, voting by ballots, payment of MPs (so poor men could serve), annual Parliaments, and abolition of property requirements. Elites saw the movement as pathological, so the Chartists were unable to force serious constitutional debate. Historians see Chartism as both a continuation of the 18th-century fight against corruption and as a new stage in demands for democracy in an industrial society.

In 1832, Parliament abolished slavery in the Empire with the

Slavery Abolition Act 1833

The Slavery Abolition Act 1833 (3 & 4 Will. IV c. 73) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which provided for the gradual abolition of slavery in most parts of the British Empire. It was passed by Earl Grey's reforming administrat ...

. The government purchased the slaves for £20,000,000 (the money went to rich plantation owners who mostly lived in England), and freed the slaves, especially those in the Caribbean sugar islands.

Leadership

Prime Ministers of the period included:

William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger (28 May 175923 January 1806) was a British statesman, the youngest and last prime minister of Great Britain (before the Acts of Union 1800) and then first prime minister of the United Kingdom (of Great Britain and Ir ...

,

Lord Grenville

William Wyndham Grenville, 1st Baron Grenville, (25 October 175912 January 1834) was a British Pittite Tory politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1806 to 1807, but was a supporter of the Whigs for the duration of ...

,

Duke of Portland

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are ranke ...

,

Spencer Perceval

Spencer Perceval (1 November 1762 – 11 May 1812) was a British statesman and barrister who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from October 1809 until his assassination in May 1812. Perceval is the only British prime minister to ...

,

Lord Liverpool,

George Canning

George Canning (11 April 17708 August 1827) was a British Tory statesman. He held various senior cabinet positions under numerous prime ministers, including two important terms as Foreign Secretary, finally becoming Prime Minister of the Uni ...

,

Lord Goderich

Frederick John Robinson, 1st Earl of Ripon, (1 November 1782 – 28 January 1859), styled The Honourable F. J. Robinson until 1827 and known between 1827 and 1833 as The Viscount Goderich (pronounced ), the name by which he is best known to ...

,

Duke of Wellington

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, (1 May 1769 – 14 September 1852) was an Anglo-Irish soldier and Tory statesman who was one of the leading military and political figures of 19th-century Britain, serving twice as prime minister ...

,

Lord Grey,

Lord Melbourne

William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne, (15 March 177924 November 1848), in some sources called Henry William Lamb, was a British Whig politician who served as Home Secretary (1830–1834) and Prime Minister (1834 and 1835–1841). His first pr ...

, and

Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet, (5 February 1788 – 2 July 1850) was a British Conservative statesman who served twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1834–1835 and 1841–1846) simultaneously serving as Chancellor of the Excheque ...

.

Victorian era

Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

ascended the throne in 1837 at age 18. Her long reign until 1901 saw Britain reach the zenith of its economic and political power. Exciting new technologies such as steam ships, railways, photography, and telegraphs appeared, making the world much faster-paced. Britain again remained mostly inactive in Continental politics, and it was not affected by the wave of revolutions in 1848. The Victorian era saw the fleshing out of the second

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

. Scholars debate whether the Victorian period—as defined by a variety of sensibilities and political concerns that have come to be associated with the Victorians—actually begins with her coronation or the earlier passage of the

Reform Act 1832

The Representation of the People Act 1832 (also known as the 1832 Reform Act, Great Reform Act or First Reform Act) was an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom (indexed as 2 & 3 Will. IV c. 45) that introduced major changes to the electo ...

. The era was preceded by the

Regency era

The Regency era of British history officially spanned the years 1811 to 1820, though the term is commonly applied to the longer period between and 1837. King George III succumbed to mental illness in late 1810 and, by the Regency Act 1811, ...

and succeeded by the

Edwardian period

The Edwardian era or Edwardian period of British history spanned the reign of King Edward VII, 1901 to 1910 and is sometimes extended to the start of the First World War. The death of Queen Victoria in January 1901 marked the end of the Victori ...

.

Historians like Bernard Porter have characterized the mid-Victorian era, (1850–1870) as Britain's 'Golden Years.'. There was peace and prosperity, as the national income per person grew by half. Much of the prosperity was due to the increasing industrialization, especially in textiles and machinery, as well as to the worldwide network of trade and engineering that produce profits for British merchants and experts from across the globe. There was peace abroad (apart from the short Crimean war, 1854–1856), and social peace at home. Reforms in industrial conditions were set by Parliament. For example, in 1842, the nation was scandalized by the use of children in coal mines. The

Mines Act of 1842

The Mines and Collieries Act 1842 (c. 99), commonly known as the Mines Act 1842, was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The Act forbade women and girls of any age to work underground and introduced a minimum age of ten for boys ...

banned employment of girls and boys under ten years old from working underground in coal mines. Opposition to the new order melted away, says Porter. The Chartist movement, peaked as a democratic movement among the working class in 1848; its leaders moved to other pursuits, such as trade unions and cooperative societies. The working class ignored foreign agitators like Karl Marx in their midst, and joined in celebrating the new prosperity. Employers typically were paternalistic, and generally recognized the trade unions. Companies provided their employees with welfare services ranging from housing, schools and churches, to libraries, baths, and gymnasia. Middle-class reformers did their best to assist the working classes aspire to middle-class norms of 'respectability.'

There was a spirit of libertarianism, says Porter, as people felt they were free. Taxes were very low, and government restrictions were minimal. There were still problem areas, such as occasional riots, especially those motivated by anti-Catholicism. Society was still ruled by the aristocracy and the gentry, which controlled high government offices, both houses of Parliament, the church, and the military. Becoming a rich businessman was not as prestigious as inheriting a title and owning a landed estate. Literature was doing well, but the fine arts languished as the Great Exhibition of 1851 showcased Britain's industrial prowess rather than its sculpture, painting or music. The educational system was mediocre; the capstone universities (outside Scotland) were likewise mediocre. Historian

Llewellyn Woodward has concluded:

According to historians David Brandon and Alan Brooke, the

new system of railways after 1830 brought into being our modern world:

Foreign policy

Free trade imperialism

The Great London Exhibition of 1851 clearly demonstrated Britain's dominance in engineering and industry; that lasted until the rise of the United States and Germany in the 1890s. Using the imperial tools of free trade and financial investment, it exerted major influence on many countries outside Europe, especially in Latin America and Asia. Thus Britain had both a formal Empire based on British rule and an informal one based on the British pound.

Russia, France and the Ottoman Empire

One nagging fear was the possible collapse of the Ottoman Empire. It was well understood that a collapse of that country would set off a scramble for its territory and possibly plunge Britain into war. To head that off Britain sought to keep the Russians from occupying Constantinople and taking over the Bosporous Straits, as well as from threatening India via Afghanistan. In 1853, Britain and France intervened in the

Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

and defeated Russia at a very high cost in casualties. In the 1870s the

Congress of Berlin