History of the Soviet Union (1964–1982) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the Soviet Union from 1964 to 1982, referred to as the Brezhnev Era, covers the period of

After a prolonged power struggle, Khrushchev was finally ousted from his post as First Secretary in October 1964, charged with the failure of his reforms, his obsessive re-organizations of the Party and Government apparatus, his disregard for Party and Government institutions, and his one-man domineering leadership style. The

After a prolonged power struggle, Khrushchev was finally ousted from his post as First Secretary in October 1964, charged with the failure of his reforms, his obsessive re-organizations of the Party and Government apparatus, his disregard for Party and Government institutions, and his one-man domineering leadership style. The

The Soviet Union launched a large military build-up in 1965 by expanding both nuclear and conventional arsenals. The Soviet leadership believed a strong military would be useful leverage in negotiating with foreign powers, and increase the Eastern Bloc's security from attacks. In the 1970s, the Soviet leadership concluded that a war with the capitalist countries might not necessarily become nuclear, and therefore they initiated a rapid expansion of the Soviet conventional forces. Due to the Soviet Union's relatively weaker infrastructure compared to the United States, the Soviet leadership believed that the only way to surpass the First World was by a rapid military conquest of Western Europe, relying on sheer numbers alone. The Soviet Union achieved nuclear parity with the United States by the early 1970s, after which the country consolidated itself as a superpower. The apparent success of the military build-up led the Soviet leadership to believe that the military, and the military alone, according to Willard Frank, "bought the Soviet Union security and influence".

Brezhnev had, according to some of his closest advisors, been concerned for a very long time about the growing military expenditure in the 1960s. Advisers have recounted how Brezhnev came into conflict with several top-level military industrialists, the most notable being Marshal

The Soviet Union launched a large military build-up in 1965 by expanding both nuclear and conventional arsenals. The Soviet leadership believed a strong military would be useful leverage in negotiating with foreign powers, and increase the Eastern Bloc's security from attacks. In the 1970s, the Soviet leadership concluded that a war with the capitalist countries might not necessarily become nuclear, and therefore they initiated a rapid expansion of the Soviet conventional forces. Due to the Soviet Union's relatively weaker infrastructure compared to the United States, the Soviet leadership believed that the only way to surpass the First World was by a rapid military conquest of Western Europe, relying on sheer numbers alone. The Soviet Union achieved nuclear parity with the United States by the early 1970s, after which the country consolidated itself as a superpower. The apparent success of the military build-up led the Soviet leadership to believe that the military, and the military alone, according to Willard Frank, "bought the Soviet Union security and influence".

Brezhnev had, according to some of his closest advisors, been concerned for a very long time about the growing military expenditure in the 1960s. Advisers have recounted how Brezhnev came into conflict with several top-level military industrialists, the most notable being Marshal

After the reshuffling process of the Politburo ended in the mid-to-late 1970, the Soviet leadership evolved into a ''

After the reshuffling process of the Politburo ended in the mid-to-late 1970, the Soviet leadership evolved into a ''

During the era, Brezhnev was also the Chairman of the Constitutional Commission of the Supreme Soviet, which worked for the creation of a new constitution. The commission had 97 members, with

During the era, Brezhnev was also the Chairman of the Constitutional Commission of the Supreme Soviet, which worked for the creation of a new constitution. The commission had 97 members, with

In his later years, Brezhnev developed his own cult of personality, and awarded himself the highest military decorations of the Soviet Union. The media extolled Brezhnev "as a dynamic leader and intellectual colossus". Brezhnev was awarded a Lenin Prize for Literature for ''

In his later years, Brezhnev developed his own cult of personality, and awarded himself the highest military decorations of the Soviet Union. The media extolled Brezhnev "as a dynamic leader and intellectual colossus". Brezhnev was awarded a Lenin Prize for Literature for ''

''

'' Another blow to Soviet communism in the First World came with the establishment of

Another blow to Soviet communism in the First World came with the establishment of

In the aftermath of Khrushchev's removal and the

In the aftermath of Khrushchev's removal and the

The Soviet leadership's policy towards the Eastern Bloc did not change much with Khrushchev's replacement, as the states of Eastern Europe were seen as a buffer zone essential to placing distance between NATO and the Soviet Union's borders. The Brezhnev regime inherited a skeptical attitude towards reform policies which became more radical in tone following the Prague Spring in 1968.

The Soviet leadership's policy towards the Eastern Bloc did not change much with Khrushchev's replacement, as the states of Eastern Europe were seen as a buffer zone essential to placing distance between NATO and the Soviet Union's borders. The Brezhnev regime inherited a skeptical attitude towards reform policies which became more radical in tone following the Prague Spring in 1968.  Not all reforms were supported by the Soviet leadership, however.

Not all reforms were supported by the Soviet leadership, however.  On 25 August 1980 the Soviet Politburo established a commission chaired by

On 25 August 1980 the Soviet Politburo established a commission chaired by

When the Ba'ath Party nationalised the

When the Ba'ath Party nationalised the  The Soviet Union also played a key role in the secessionist struggle against the

The Soviet Union also played a key role in the secessionist struggle against the

Soviet society is generally regarded as having reached maturity under Brezhnev's rule. Edwin Bacon and Mark Sandle in their 2002 book ''Brezhnev Reconsidered'' noted that "a social revolution" took place in the Soviet Union during his 18-year-long ascendancy. The increasingly modernized Soviet society was becoming more urban, and people became better educated and more professionalized. In contrast to previous periods dominated by "terrors, cataclysms and conflicts", the Brezhnev era constituted a period of continuous development without interruption. There was a fourfold growth in higher education between the 1950s and 1980s; official discourse referred to this development as the "scientific-technological revolution". In addition, women came to make up half of the country's educated specialists.

Following Khrushchev's controversial 1961 claim that (pure) communism could be reached "within 20 years", the new Soviet leadership responded by fostering the concept of "developed socialism". Brezhnev declared the onset of the era of developed socialism in 1971 at the

Soviet society is generally regarded as having reached maturity under Brezhnev's rule. Edwin Bacon and Mark Sandle in their 2002 book ''Brezhnev Reconsidered'' noted that "a social revolution" took place in the Soviet Union during his 18-year-long ascendancy. The increasingly modernized Soviet society was becoming more urban, and people became better educated and more professionalized. In contrast to previous periods dominated by "terrors, cataclysms and conflicts", the Brezhnev era constituted a period of continuous development without interruption. There was a fourfold growth in higher education between the 1950s and 1980s; official discourse referred to this development as the "scientific-technological revolution". In addition, women came to make up half of the country's educated specialists.

Following Khrushchev's controversial 1961 claim that (pure) communism could be reached "within 20 years", the new Soviet leadership responded by fostering the concept of "developed socialism". Brezhnev declared the onset of the era of developed socialism in 1971 at the

From 1964 to 1973, the Soviet GDP per head (as expressed in

From 1964 to 1973, the Soviet GDP per head (as expressed in  The Brezhnev era saw material improvements for the Soviet citizen, but the Politburo received no credit for this; the average Soviet citizen took for granted the material improvements in the 1970s, i.e. the cheap provision of consumer goods, food, shelter, clothing, sanitation, health care, and

The Brezhnev era saw material improvements for the Soviet citizen, but the Politburo received no credit for this; the average Soviet citizen took for granted the material improvements in the 1970s, i.e. the cheap provision of consumer goods, food, shelter, clothing, sanitation, health care, and  These effects were not felt uniformly, however. For example, by the end of the Brezhnev era, blue-collar workers had higher wages than professional workers in the Soviet Union – the wage of a secondary-school teacher in the Soviet Union was only 150 rubles while a bus driver earned 230. As a whole, real wages increased from 96.5 rubles a month in 1965 to 190.1 rubles a month in 1985. A small minority benefited even more substantially. The state provided daily recreation and annual holidays for hard-working citizens. Soviet trade unions rewarded hard-working members and their families with beach vacations in

These effects were not felt uniformly, however. For example, by the end of the Brezhnev era, blue-collar workers had higher wages than professional workers in the Soviet Union – the wage of a secondary-school teacher in the Soviet Union was only 150 rubles while a bus driver earned 230. As a whole, real wages increased from 96.5 rubles a month in 1965 to 190.1 rubles a month in 1985. A small minority benefited even more substantially. The state provided daily recreation and annual holidays for hard-working citizens. Soviet trade unions rewarded hard-working members and their families with beach vacations in

Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev; uk, links= no, Леонід Ілліч Брежнєв, . (19 December 1906– 10 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union between 1964 and ...

's rule of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

(USSR). This period began with high economic growth and soaring prosperity, but gradually significant problems in social, political, and economic areas accumulated, so that the period is often described as the Era of Stagnation

The "Era of Stagnation" (russian: Пери́од засто́я, Períod zastóya, or ) is a term coined by Mikhail Gorbachev in order to describe the negative way in which he viewed the economic, political, and social policies of the Soviet Uni ...

. In the 1970s, both sides took a stance of " detente". The goal of this strategy was to warm up relations, in the hope that the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

would pursue economic and democratic reforms. However, this did not come until Mikhail Gorbachev took office in 1985.

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

was ousted as First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) (as well as Chairman of the Council of Ministers

A council is a group of people who come together to consult, deliberate, or make decisions. A council may function as a legislature, especially at a town, city or county/ shire level, but most legislative bodies at the state/provincial or nati ...

) on 14 October 1964, due to his failed reforms and disregard for Party and Government institutions. Brezhnev replaced Khrushchev as First Secretary and Alexei Kosygin

Alexei Nikolayevich Kosygin ( rus, Алексе́й Никола́евич Косы́гин, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsʲej nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ kɐˈsɨɡʲɪn; – 18 December 1980) was a Soviet statesman during the Cold War. He served as the Premi ...

replaced him as Chairman of the Council of Ministers. Anastas Mikoyan, and later Nikolai Podgorny

Nikolai Viktorovich Podgorny, ''Mykola Viktorovych Pidhornyy'' rus, Никола́й Ви́кторович Подго́рный, p=nʲɪkɐˈlaj ˈvʲiktərəvʲɪtɕ pɐdˈgornɨj, links=yes ( – 12 January 1983) was a Soviet statesman who ...

, became Chairmen

The chairperson, also chairman, chairwoman or chair, is the presiding officer of an organized group such as a board, committee, or deliberative assembly. The person holding the office, who is typically elected or appointed by members of the group ...

of the Presidium

A presidium or praesidium is a council of executive officers in some political assemblies that collectively administers its business, either alongside an individual president or in place of one.

Communist states

In Communist states the presid ...

of the Supreme Soviet. Together with Andrei Kirilenko

Andrei Gennadyevich Kirilenko (russian: Андрей Геннадьевич Кириленко; born February 18, 1981) is a Russian-American basketball executive and former professional basketball player, currently the commissioner of the Russ ...

as organizational secretary, and Mikhail Suslov

Mikhail Andreyevich Suslov (russian: Михаи́л Андре́евич Су́слов; 25 January 1982) was a Soviet statesman during the Cold War. He served as Second Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1965, and as uno ...

as Chief Ideologue, they made up a reinvigorated collective leadership

A collective is a group of entities that share or are motivated by at least one common issue or interest, or work together to achieve a common objective. Collectives can differ from cooperatives in that they are not necessarily focused upon an ...

, which contrasted in form with the autocracy that characterized Khrushchev's rule.

The collective leadership first set out to stabilize the Soviet Union and calm Soviet society

The culture of the Soviet Union passed through several stages during the country's 69-year existence. It was contributed to by people of various nationalities from every one of fifteen union republics, although a majority of the influence was made ...

, a task which they were able to accomplish. In addition, they attempted to speed up economic growth, which had slowed considerably during Khrushchev's last years as ruler. In 1965, Kosygin initiated several reforms

Reform ( lat, reformo) means the improvement or amendment of what is wrong, corrupt, unsatisfactory, etc. The use of the word in this way emerges in the late 18th century and is believed to originate from Christopher Wyvill's Association movement ...

to decentralize the Soviet economy

The economy of the Soviet Union was based on state ownership of the means of production, collective farming, and industrial manufacturing. An administrative-command system managed a distinctive form of central planning. The Soviet economy was ...

. After initial success in creating economic growth, hard-liners within the Party halted the reforms, fearing that they would weaken the Party's prestige and power. The reforms themselves were never officially abolished, they were simply sidelined and stopped having any effect. No other radical economic reforms were carried out during the Brezhnev era, and economic growth began to stagnate in the early-to-mid-1970s. By Brezhnev's death in 1982, Soviet economic growth had, according to several historians, nearly come to a standstill.

The stabilization policy brought about after Khrushchev's removal established a ruling gerontocracy

A gerontocracy is a form of oligarchical rule in which an entity is ruled by leaders who are significantly older than most of the adult population. In many political structures, power within the ruling class accumulates with age, making the oldes ...

, and political corruption became a normal phenomenon. Brezhnev, however, never initiated any large-scale anti-corruption campaigns. Due to the large military buildup of the 1960s, the Soviet Union was able to consolidate itself as a superpower during Brezhnev's rule. The era ended with Brezhnev's death on 10 November 1982.

Politics

Collectivity of leadership

After a prolonged power struggle, Khrushchev was finally ousted from his post as First Secretary in October 1964, charged with the failure of his reforms, his obsessive re-organizations of the Party and Government apparatus, his disregard for Party and Government institutions, and his one-man domineering leadership style. The

After a prolonged power struggle, Khrushchev was finally ousted from his post as First Secretary in October 1964, charged with the failure of his reforms, his obsessive re-organizations of the Party and Government apparatus, his disregard for Party and Government institutions, and his one-man domineering leadership style. The Presidium

A presidium or praesidium is a council of executive officers in some political assemblies that collectively administers its business, either alongside an individual president or in place of one.

Communist states

In Communist states the presid ...

(Politburo), the Central Committee and other important Party–Government bodies had grown tired of Khrushchev's repeated violations of established Party principles. The Soviet leadership also believed that his individualistic leadership style ran contrary to the ideal collective leadership

A collective is a group of entities that share or are motivated by at least one common issue or interest, or work together to achieve a common objective. Collectives can differ from cooperatives in that they are not necessarily focused upon an ...

. Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev; uk, links= no, Леонід Ілліч Брежнєв, . (19 December 1906– 10 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union between 1964 and ...

and Alexei Kosygin

Alexei Nikolayevich Kosygin ( rus, Алексе́й Никола́евич Косы́гин, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsʲej nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ kɐˈsɨɡʲɪn; – 18 December 1980) was a Soviet statesman during the Cold War. He served as the Premi ...

succeeded Khrushchev in his posts as First Secretary and Premier respectively, and Mikhail Suslov

Mikhail Andreyevich Suslov (russian: Михаи́л Андре́евич Су́слов; 25 January 1982) was a Soviet statesman during the Cold War. He served as Second Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1965, and as uno ...

, Andrei Kirilenko

Andrei Gennadyevich Kirilenko (russian: Андрей Геннадьевич Кириленко; born February 18, 1981) is a Russian-American basketball executive and former professional basketball player, currently the commissioner of the Russ ...

, and Anastas Mikoyan (replaced in 1965 by Nikolai Podgorny

Nikolai Viktorovich Podgorny, ''Mykola Viktorovych Pidhornyy'' rus, Никола́й Ви́кторович Подго́рный, p=nʲɪkɐˈlaj ˈvʲiktərəvʲɪtɕ pɐdˈgornɨj, links=yes ( – 12 January 1983) was a Soviet statesman who ...

), were also given prominence in the new leadership. Together they formed a functional collective leadership.

The collective leadership was, in its early stages, usually referred to as the "Brezhnev–Kosygin" leadership and the pair began their respective periods in office on a relatively equal footing. After Kosygin initiated the economic reform of 1965, however, his prestige within the Soviet leadership withered and his subsequent loss of power strengthened Brezhnev's position within the Soviet hierarchy. Kosygin's influence was further weakened when Podgorny took his post as the second-most powerful figure in the Soviet Union.

Brezhnev conspired to oust Podgorny from the collective leadership as early as 1970. The reason was simple: Brezhnev was third, while Podgorny was first in the ranking of Soviet diplomatic protocol; Podgorny's removal would have made Brezhnev head of state, and his political power would have increased significantly. For much of the period, however, Brezhnev was unable to have Podgorny removed, because he could not count on enough votes in the Politburo, since the removal of Podgorny would have meant weakening of the power and the prestige of the collective leadership itself. Indeed, Podgorny continued to acquire greater power as the head of state throughout the early 1970s, due to Brezhnev's liberal stance on Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

and his disarmament talks with some Western powers, policies which many Soviet officials saw as contrary to common communist principles.

This did not remain the case, however. Brezhnev strengthened his position considerably during the early to mid-1970s within the Party leadership and by a further weakening of the "Kosygin faction"; by 1977 he had enough support in the Politburo to oust Podgorny from office and active politics in general. Podgorny's eventual removal in 1977 had the effect of reducing Kosygin's role in day-to-day management of government activities by strengthening the powers of the government apparatus led by Brezhnev. After Podgorny's removal rumours started circulating Soviet society that Kosygin was about to retire due to his deteriorating health condition. Nikolai Tikhonov

Nikolai Aleksandrovich Tikhonov (russian: Николай Александрович Тихонов; ukr, Микола Олександрович Тихонов; – 1 June 1997) was a Soviet Russian-Ukrainian statesman during the Cold War. H ...

, a First Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers

A council is a group of people who come together to consult, deliberate, or make decisions. A council may function as a legislature, especially at a town, city or county/ shire level, but most legislative bodies at the state/provincial or nati ...

under Kosygin, succeeded the later as premier in 1980 (see Kosygin's resignation).

Podgorny's fall was not seen as the end of the collective leadership, and Suslov continued to write several ideological documents about it. In 1978, one year after Podgorny's retirement, Suslov made several references to the collective leadership in his ideological works. It was around this time that Kirilenko's power and prestige within the Soviet leadership started to wane. Indeed, towards the end of the period, Brezhnev was regarded as too old to simultaneously exercise all of the functions of head of state by his colleagues. With this in mind, the Supreme Soviet, on Brezhnev's orders, established the new post of First Deputy Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, a post akin to a "vice president

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

". The Supreme Soviet unanimously approved Vasili Kuznetsov, at the age of 76, to be First Deputy Chairman of the Presidium in late 1977. As Brezhnev's health worsened, the collective leadership took an even more important role in everyday decision-making. For this reason, Brezhnev's death did not alter the balance of power in any radical fashion, and Yuri Andropov

Yuri Vladimirovich Andropov (– 9 February 1984) was the sixth paramount leader of the Soviet Union and the fourth General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. After Leonid Brezhnev's 18-year rule, Andropov served in the p ...

and Konstantin Chernenko

Konstantin Ustinovich Chernenko uk, Костянтин Устинович Черненко, translit=Kostiantyn Ustynovych Chernenko (24 September 1911 – 10 March 1985) was a Soviet politician and the seventh General Secretary of the Commu ...

were obliged by protocol to rule the country in the same fashion as Brezhnev left it.

Assassination attempt

Viktor Ilyin

Viktor Ivanovich Ilyin (Russian: Ви́ктор Ива́нович Ильи́н; born 26 December 1947) is a Soviet Army deserter who, at the rank of second lieutenant, attempted to assassinate the Soviet leader, Leonid Brezhnev on 22 Janua ...

, a disenfranchised

Disfranchisement, also called disenfranchisement, or voter disqualification is the restriction of suffrage (the right to vote) of a person or group of people, or a practice that has the effect of preventing a person exercising the right to vote. D ...

Soviet soldier, attempted to assassinate Brezhnev on 22 January 1969 by firing shots at a motorcade carrying Brezhnev through Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

. Though Brezhnev was unhurt, the shots killed a driver and lightly injured several celebrated cosmonauts

An astronaut (from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'star', and (), meaning 'sailor') is a person trained, equipped, and deployed by a human spaceflight program to serve as a commander or crew member aboard a spacecraft. Although generally r ...

of the Soviet space program

The Soviet space program (russian: Космическая программа СССР, Kosmicheskaya programma SSSR) was the national space program of the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), active from 1955 until the dissoluti ...

me who were also travelling in the motorcade. Brezhnev's attacker was captured, and interrogated personally by Andropov, then KGB chairman and future Soviet leader. Ilyin was not given the death penalty because his desire to kill Brezhnev was considered so absurd that he was sent to the Kazan

Kazan ( ; rus, Казань, p=kɐˈzanʲ; tt-Cyrl, Казан, ''Qazan'', IPA: ɑzan is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Tatarstan in Russia. The city lies at the confluence of the Volga and the Kazanka rivers, covering an ...

mental asylum instead for treatment.

Defense policy

The Soviet Union launched a large military build-up in 1965 by expanding both nuclear and conventional arsenals. The Soviet leadership believed a strong military would be useful leverage in negotiating with foreign powers, and increase the Eastern Bloc's security from attacks. In the 1970s, the Soviet leadership concluded that a war with the capitalist countries might not necessarily become nuclear, and therefore they initiated a rapid expansion of the Soviet conventional forces. Due to the Soviet Union's relatively weaker infrastructure compared to the United States, the Soviet leadership believed that the only way to surpass the First World was by a rapid military conquest of Western Europe, relying on sheer numbers alone. The Soviet Union achieved nuclear parity with the United States by the early 1970s, after which the country consolidated itself as a superpower. The apparent success of the military build-up led the Soviet leadership to believe that the military, and the military alone, according to Willard Frank, "bought the Soviet Union security and influence".

Brezhnev had, according to some of his closest advisors, been concerned for a very long time about the growing military expenditure in the 1960s. Advisers have recounted how Brezhnev came into conflict with several top-level military industrialists, the most notable being Marshal

The Soviet Union launched a large military build-up in 1965 by expanding both nuclear and conventional arsenals. The Soviet leadership believed a strong military would be useful leverage in negotiating with foreign powers, and increase the Eastern Bloc's security from attacks. In the 1970s, the Soviet leadership concluded that a war with the capitalist countries might not necessarily become nuclear, and therefore they initiated a rapid expansion of the Soviet conventional forces. Due to the Soviet Union's relatively weaker infrastructure compared to the United States, the Soviet leadership believed that the only way to surpass the First World was by a rapid military conquest of Western Europe, relying on sheer numbers alone. The Soviet Union achieved nuclear parity with the United States by the early 1970s, after which the country consolidated itself as a superpower. The apparent success of the military build-up led the Soviet leadership to believe that the military, and the military alone, according to Willard Frank, "bought the Soviet Union security and influence".

Brezhnev had, according to some of his closest advisors, been concerned for a very long time about the growing military expenditure in the 1960s. Advisers have recounted how Brezhnev came into conflict with several top-level military industrialists, the most notable being Marshal Andrei Grechko

Andrei Antonovich Grechko (, ; – 26 April 1976) was a Marshal of the Soviet Union (from 1955). He was Minister of Defence of the Soviet Union from 1967 to 1976.

Early life

Grechko was the thirteenth child born to a family of Ukrainian peasant ...

, the Minister of Defense. In the early 1970s, according to Anatoly Aleksandrov-Agentov, one of Brezhnev's closest advisers, Brezhnev attended a five-hour meeting to try to convince the Soviet military establishment to reduce military spending. In the meeting an irritated Brezhnev asked why the Soviet Union should, in the words of Matthew Evangelista, "continue to exhaust" the economy if the country could not be promised a military parity with the West; the question was left unanswered. When Grechko died in 1976, Dmitriy Ustinov

Dmitriy Fyodorovich Ustinov (russian: Дмитрий Фёдорович Устинов; 30 October 1908 – 20 December 1984) was a Marshal of the Soviet Union and Soviet politician during the Cold War. He served as a Central Committee se ...

took his place as Defense Minister. Ustinov, although a close associate and friend of Brezhnev, hindered any attempt made by Brezhnev to reduce national military expenditure. In his later years, Brezhnev lacked the will to reduce defense expenditure, due to his declining health. According to the Soviet diplomat Georgy Arbatov

Georgy Arkadyevich Arbatov (russian: Гео́ргий Арка́дьевич Арба́тов, 19 May 1923, Kherson – 1 October 2010, Moscow) was a Soviet and Russian political scientist who served as an adviser to five General Secretaries of th ...

, the military–industrial complex

The expression military–industrial complex (MIC) describes the relationship between a country's military and the defense industry that supplies it, seen together as a vested interest which influences public policy. A driving factor behind the r ...

functioned as Brezhnev's power base within the Soviet hierarchy even if he tried to scale-down investments.

At the 23rd Party Congress in 1966, Brezhnev told the delegates that the Soviet military had reached a level fully sufficient to defend the country. The Soviet Union reached ICBM parity with the United States that year. In early 1977, Brezhnev told the world that the Soviet Union did not seek to become superior to the United States in nuclear weapons, nor to be militarily superior in any sense of the word. In the later years of Brezhnev's reign, it became official defense policy to only invest enough to maintain military deterrence, and by the 1980s, Soviet defense officials were told again that investment would not exceed the level to retain national security. In his last meeting with Soviet military leaders in October 1982, Brezhnev stressed the importance of not over-investing in the Soviet military sector. This policy was retained during the rules of Andropov, Konstantin Chernenko

Konstantin Ustinovich Chernenko uk, Костянтин Устинович Черненко, translit=Kostiantyn Ustynovych Chernenko (24 September 1911 – 10 March 1985) was a Soviet politician and the seventh General Secretary of the Commu ...

and Mikhail Gorbachev. He also said that the time was opportune to increase the readiness of the armed forces even further. At the anniversary of the 1917 Revolution a few weeks later (Brezhnev's final public appearance), Western observers noted that the annual military parade featured only two new weapons and most of the equipment displayed was obsolete. Two days before his death, Brezhnev stated that any aggression against the Soviet Union "would result in a crushing retaliatory blow".

Stabilization

Though Brezhnev's time in office would later be characterized as one of stability, early on, Brezhnev oversaw the replacement of half of the regional leaders and Politburo members. This was a typical move for a Soviet leader trying to strengthen his power base. Examples of Politburo members who lost their membership during the Brezhnev Era are Gennady Voronov, Dmitry Polyansky,Alexander Shelepin

Alexander Nikolayevich Shelepin (; 18 August 1918 – 24 October 1994) was a Soviet politician and security and intelligence officer. A long-time member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, he served as First Depu ...

, Petro Shelest

Petro Yukhymovych Shelestrussian: Пётр Ефи́мович Ше́лест, translit=Pyotr Yefimovich Shelest (14 February 190822 January 1996) was a Ukrainian Soviet politician. First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Ukrainian Sovi ...

and Podgorny. Polyansky and Voronov lost their membership in the Politburo because they were considered to be members of the "Kosygin faction." In their place came Andrei Grechko

Andrei Antonovich Grechko (, ; – 26 April 1976) was a Marshal of the Soviet Union (from 1955). He was Minister of Defence of the Soviet Union from 1967 to 1976.

Early life

Grechko was the thirteenth child born to a family of Ukrainian peasant ...

, the Minister of Defense, Andrei Gromyko

Andrei Andreyevich Gromyko (russian: Андрей Андреевич Громыко; be, Андрэй Андрэевіч Грамыка; – 2 July 1989) was a Soviet communist politician and diplomat during the Cold War. He served as ...

the Minister of Foreign Affairs

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between co ...

and KGB

The KGB (russian: links=no, lit=Committee for State Security, Комитет государственной безопасности (КГБ), a=ru-KGB.ogg, p=kəmʲɪˈtʲet ɡəsʊˈdarstvʲɪn(ː)əj bʲɪzɐˈpasnəsʲtʲɪ, Komitet gosud ...

Chairman Andropov. The removal and replacement of members of the Soviet leadership halted in late 1970s.

Initially, in fact, Brezhnev portrayed himself as a moderate — not as radical as Kosygin but not as conservative as Shelepin. Brezhnev gave the Central Committee formal permission to initiate Kosygin's 1965 economic reform. According to historian Robert Service, Brezhnev did modify some of Kosygin's reform proposals, many of which were unhelpful at best. In his early days, Brezhnev asked for advice from provincial party secretaries, and spent hours each day on such conversations. During the March 1965 Central Committee plenum

Plenum may refer to:

* Plenum chamber, a chamber intended to contain air, gas, or liquid at positive pressure

* Plenism, or ''Horror vacui'' (physics) the concept that "nature abhors a vacuum"

* Plenum (meeting), a meeting of a deliberative asse ...

, Brezhnev took control of Soviet agriculture, another hint that he opposed Kosygin's reform program. Brezhnev believed, in contrast to Khrushchev, that rather than wholesale re-organization, the key to increasing agricultural output was making the existing system work more efficiently.

In the late 1960s, Brezhnev talked of the need to "renew" the party cadres, but according to Robert Service, his "self-interest discouraged him from putting an end to the immobilism he detected. He did not want to risk alienating lower-level officialdom." The Politburo saw the policy of stabilization as the only way to avoid returning to Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

's purges and Khrushchev's re-organization of Party-Government institutions. Members acted in optimism, and believed a policy of stabilization would prove to the world, according to Robert Service, the "superiority of communism". The Soviet leadership was not entirely opposed to reform, even if the reform movement had been weakened in the aftermath of the Prague Spring in the Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

. The result was a period of overt stabilization at the heart of government, a policy which also had the effect of reducing cultural freedom: several dissident samizdat

Samizdat (russian: самиздат, lit=self-publishing, links=no) was a form of dissident activity across the Eastern Bloc in which individuals reproduced censored and underground makeshift publications, often by hand, and passed the document ...

s were shut down.

Gerontocracy

After the reshuffling process of the Politburo ended in the mid-to-late 1970, the Soviet leadership evolved into a ''

After the reshuffling process of the Politburo ended in the mid-to-late 1970, the Soviet leadership evolved into a ''gerontocracy

A gerontocracy is a form of oligarchical rule in which an entity is ruled by leaders who are significantly older than most of the adult population. In many political structures, power within the ruling class accumulates with age, making the oldes ...

'', a form of rule in which the rulers are significantly older than most of the adult population.

The Brezhnev generation — the people who lived and worked during the Brezhnev Era — owed their rise to prominence to Joseph Stalin's Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secret ...

in the late 1930s. In the purge, Stalin ordered the execution or exile of nearly all Soviet bureaucrats over the age of 35, thereby opening up posts and offices for a younger generation of Soviets. This generation would rule the country from the aftermath of Stalin's purge up to Mikhail Gorbachev's rise to power in 1985. The majority of these appointees were of either peasant or working class origin. Mikhail Suslov, Alexei Kosygin, and Brezhnev are prime examples of men appointed in the aftermath of Stalin's Great Purge.

The average age of the Politburo's members was 58 years in 1961, and 71 in 1981. A similar greying also took place in the Central Committee, the median age rising from 53 in 1961 to 62 in 1981, with the proportion of members older than 65 increasing from 3 percent in 1961 to 39 percent in 1981. The difference in the median age between Politburo and Central Committee members can be explained by the fact that the Central Committee was consistently enlarged during Brezhnev's leadership; this made it possible to appoint new and younger members to the Central Committee without retiring some of its oldest members. Of the 319-member Central Committee in 1981, 130 were younger than 30 when Stalin died in 1953.

Young politicians, such as Fyodor Kulakov

Fyodor Davydovich Kulakov (russian: Фёдор Давыдович Кулаков) (4 February 1918 – 17 July 1978) was a Soviet statesman during the Cold War.

Kulakov served as Stavropol First Secretary from 1960 until 1964, immediately followi ...

and Grigory Romanov, were seen as potential successors to Brezhnev, but none of them came close. For example, Kulakov, one of the youngest members in the Politburo, was ranked seventh in the prestige order voted by the Supreme Soviet, far behind such notables as Kosygin, Podgorny, Suslov, and Kirilenko. As Edwin Bacon and Mark Sandle note in their book, ''Brezhnev Reconsidered'', the Soviet leadership at Brezhnev's deathbed had evolved into "a gerontocracy increasingly lacking of physical and intellectual vigour".

New constitution

During the era, Brezhnev was also the Chairman of the Constitutional Commission of the Supreme Soviet, which worked for the creation of a new constitution. The commission had 97 members, with

During the era, Brezhnev was also the Chairman of the Constitutional Commission of the Supreme Soviet, which worked for the creation of a new constitution. The commission had 97 members, with Konstantin Chernenko

Konstantin Ustinovich Chernenko uk, Костянтин Устинович Черненко, translit=Kostiantyn Ustynovych Chernenko (24 September 1911 – 10 March 1985) was a Soviet politician and the seventh General Secretary of the Commu ...

among the more prominent. Brezhnev was not driven by a wish to leave a mark on history, but rather to even further weaken Premier Alexei Kosygin

Alexei Nikolayevich Kosygin ( rus, Алексе́й Никола́евич Косы́гин, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsʲej nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ kɐˈsɨɡʲɪn; – 18 December 1980) was a Soviet statesman during the Cold War. He served as the Premi ...

's prestige. The formulation of the constitution kept with Brezhnev's political style and was neither anti-Stalinist

The anti-Stalinist left is an umbrella term for various kinds of left-wing political movements that opposed Joseph Stalin, Stalinism and the actual system of governance Stalin implemented as leader of the Soviet Union between 1927 and 1953. Th ...

nor neo-Stalinist, but stuck to a middle path, following most of the same principles and ideas as the previous constitutions. The most notable difference was that it codified the developmental changes which the Soviet Union had passed through since the formulation of the 1936 Constitution. It described the Soviet Union, for example, as an "advanced industrial society". In this sense, the resulting document can be seen as proof of the achievements, as well as the limits, of de-Stalinization. It enhanced the status of the individual in all matters of life, while at the same time solidifying the Party's hold on power.

During the drafting process, a debate within the Soviet leadership took place between the two factions on whether to call Soviet law

The Law of the Soviet Union was the law as it developed in the Soviet Union (USSR) following the October Revolution of 1917. Modified versions of the Soviet legal system operated in many Communist states following the Second World War—including ...

"State law" or "Constitutional law." Those who supported the thesis of state law believed that the Constitution was of low importance, and that it could be changed whenever the socio-economic system changed. Those who supported Constitutional law believed that the Constitution should "conceptualise" and incorporate some of the Party's future ideological goals. They also wanted to include information on the status of the Soviet citizen, which had changed drastically in the post-Stalin years. Constitutional thought prevailed to an extent, and the 1977 Soviet Constitution had a greater effect on conceptualising the Soviet system.

Later years

In his later years, Brezhnev developed his own cult of personality, and awarded himself the highest military decorations of the Soviet Union. The media extolled Brezhnev "as a dynamic leader and intellectual colossus". Brezhnev was awarded a Lenin Prize for Literature for ''

In his later years, Brezhnev developed his own cult of personality, and awarded himself the highest military decorations of the Soviet Union. The media extolled Brezhnev "as a dynamic leader and intellectual colossus". Brezhnev was awarded a Lenin Prize for Literature for ''Brezhnev's trilogy

The Brezhnev's trilogy (russian: link=no, Трилогия Брежнева) (1978–79) was a series of three memoirs published under name of Leonid Brezhnev:

* ''The Minor Land'' (russian: link=no, Малая земля, lit=Malaya Zemlya, trans ...

'', three auto-biographical novels. These awards were given to Brezhnev to bolster his position within the Party and the Politburo. When Alexei Kosygin

Alexei Nikolayevich Kosygin ( rus, Алексе́й Никола́евич Косы́гин, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsʲej nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ kɐˈsɨɡʲɪn; – 18 December 1980) was a Soviet statesman during the Cold War. He served as the Premi ...

died on 18 December 1980, one day before Brezhnev's birthday, ''Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, "Truth") is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most influential papers in the ...

'' and other media outlets postponed the reporting of his death until after Brezhnev's birthday celebration. In reality, however, Brezhnev's physical and intellectual capacities had started to decline in the 1970s from bad health.

Brezhnev approved the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

(see also ''Soviet–Afghan relations'') just as he had previously approved the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia

The Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia refers to the events of 20–21 August 1968, when the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was jointly invaded by four Warsaw Pact countries: the Soviet Union, the Polish People's Republic, the People's Rep ...

. In both cases, Brezhnev was not the one pushing hardest for a possible armed intervention. Several leading members of the Soviet leadership decided to retain Brezhnev as General Secretary so that their careers would not suffer by a possible leadership reshuffling by his successor. Other members, who disliked Brezhnev, among them Dmitriy Ustinov

Dmitriy Fyodorovich Ustinov (russian: Дмитрий Фёдорович Устинов; 30 October 1908 – 20 December 1984) was a Marshal of the Soviet Union and Soviet politician during the Cold War. He served as a Central Committee se ...

(Minister of Defence

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in som ...

), Andrei Gromyko

Andrei Andreyevich Gromyko (russian: Андрей Андреевич Громыко; be, Андрэй Андрэевіч Грамыка; – 2 July 1989) was a Soviet communist politician and diplomat during the Cold War. He served as ...

(Minister of Foreign Affairs

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between co ...

), and Mikhail Suslov

Mikhail Andreyevich Suslov (russian: Михаи́л Андре́евич Су́слов; 25 January 1982) was a Soviet statesman during the Cold War. He served as Second Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1965, and as uno ...

(Central Committee Secretary), feared that Brezhnev's removal would spark a succession crisis, and so they helped to maintain the status quo.

Brezhnev stayed in office under pressure from some of his Politburo associates, though in practice the country was not governed by Brezhnev, but instead by a collective leadership led by Suslov, Ustinov, Gromyko, and Yuri Andropov

Yuri Vladimirovich Andropov (– 9 February 1984) was the sixth paramount leader of the Soviet Union and the fourth General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. After Leonid Brezhnev's 18-year rule, Andropov served in the p ...

. Konstantin Chernenko

Konstantin Ustinovich Chernenko uk, Костянтин Устинович Черненко, translit=Kostiantyn Ustynovych Chernenko (24 September 1911 – 10 March 1985) was a Soviet politician and the seventh General Secretary of the Commu ...

, due to his close relationship with Brezhnev, had also acquired influence. While the Politburo was pondering who would take Brezhnev's place, his health continued to worsen. The choice of a successor would have been influenced by Suslov, but since he died in January 1982, before Brezhnev, Andropov took Suslov's place in the Central Committee Secretariat. With Brezhnev's health worsening, Andropov showed his Politburo colleagues that he was not afraid of Brezhnev's reprisals any more, and launched a major anti-corruption campaign. On 10 November 1982, Brezhnev died and was honored with major state funeral and buried 5 days later at the Kremlin Wall Necropolis

The Kremlin Wall Necropolis was the national cemetery for the Soviet Union. Burials in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis in Moscow began in November 1917, when 240 pro-Bolshevik individuals who died during the Moscow Bolshevik Uprising were buried in m ...

.

Economy

1965 reform

The 1965 Soviet economic reform, often referred to as the "Kosygin reform", of economic management and planning was carried out between 1965 and 1971. Announced in September 1965, it contained three main measures: the re-centralization of theSoviet economy

The economy of the Soviet Union was based on state ownership of the means of production, collective farming, and industrial manufacturing. An administrative-command system managed a distinctive form of central planning. The Soviet economy was ...

by re-establishing several central ministries, a decentralizing overhaul of the enterprise incentive system (including wider usage of capitalist-style material incentives for good performance), and thirdly, a major price reform. The reform was initiated by Alexei Kosygin

Alexei Nikolayevich Kosygin ( rus, Алексе́й Никола́евич Косы́гин, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsʲej nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ kɐˈsɨɡʲɪn; – 18 December 1980) was a Soviet statesman during the Cold War. He served as the Premi ...

's First Government and implemented during the Eighth Five-Year Plan, 1968–1970.

Though these measures were established to counter many of the irrationalities in the Soviet economic system, the reform did not try to change the existing system radically; it instead tried to improve it gradually. Success was ultimately mixed, and Soviet analyses on why the reform failed to reach its full potential have never given any definitive answers. The key factors are agreed upon, however, with blame being put on the combination of the recentralisation of the economy with the decentralisation of enterprise autonomy, creating several administrative obstacles. Additionally, instead of creating a market which in turn would establish a pricing system, administrators were given the responsibility for overhauling the pricing system themselves. Because of this, the market-like system failed to materialise. To make matters worse, the reform was contradictory at best. In retrospect, however, the Eighth Five-Year Plan as a whole is considered to be one of the most successful periods for the Soviet economy, and the most successful for consumer production.

The marketization

Marketisation or marketization is a restructuring process that enables state enterprises to operate as market-oriented firms by changing the legal environment in which they operate.

This is achieved through reduction of state subsidies, organizati ...

of the economy, in which Kosygin supported, was considered too radical in the light of the Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

. Nikolai Ryzhkov

Nikolai Ivanovich Ryzhkov ( uk, Микола Іванович Рижков; russian: Николай Иванович Рыжков; born 28 September 1929) is a Soviet, and later Russian, politician. He served as the last Chairman of the Coun ...

, the future Chairman of the Council of Ministers, referred in a 1987 speech to the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union to the "sad experiences of the 1965 reform", and claimed that everything went from bad to worse following the reform's cancellation.

Era of Stagnation

The value of all consumer goods manufactured in 1972 in retail prices was about 118 billion rubles ($530 billion). TheEra of Stagnation

The "Era of Stagnation" (russian: Пери́од засто́я, Períod zastóya, or ) is a term coined by Mikhail Gorbachev in order to describe the negative way in which he viewed the economic, political, and social policies of the Soviet Uni ...

, a term coined by Mikhail Gorbachev, is considered by several economists to be the worst financial crisis

A financial crisis is any of a broad variety of situations in which some financial assets suddenly lose a large part of their nominal value. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, many financial crises were associated with banking panics, and man ...

in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

. It was triggered by the Nixon Shock, over-centralisation and a conservative state bureaucracy. As the economy grew, the volume of decisions facing planners in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

became overwhelming. As a result, labour productivity decreased nationwide. The cumbersome procedures of bureaucratic administration did not allow for the free communication and flexible response required at the enterprise level to deal with worker alienation, innovation, customers and suppliers. The late Brezhnev Era also saw an increase in political corruption. Data falsification became common practice among bureaucrats to report satisfied targets and quotas to the government, and this further aggravated the crisis in planning.

With the mounting economic problems, skilled workers were usually paid more than had been intended in the first place, while unskilled labourers tended to turn up late, and were neither conscientious nor, in a number of cases, entirely sober. The state usually moved workers from one job to another which ultimately became an ineradicable feature in Soviet industry; the Government had no effective counter-measure because of the country's lack of unemployment

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work during the refere ...

. Government industries such as factories, mines and offices were staffed by undisciplined personnel who put a great effort into not doing their jobs. This ultimately led to, according to Robert Service, a "work-shy workforce" among Soviet workers and administrators.

1973 and 1979 reform

Kosygin initiated the 1973 Soviet economic reform to enhance the powers and functions of the regional planners by establishing associations. The reform was never fully implemented; indeed, members of the Soviet leadership complained that the reform had not even begun by the time of the 1979 reform. The 1979 Soviet economic reform was initiated to improve the then-stagnatingSoviet economy

The economy of the Soviet Union was based on state ownership of the means of production, collective farming, and industrial manufacturing. An administrative-command system managed a distinctive form of central planning. The Soviet economy was ...

. The reform's goal was to increase the powers of the central ministries by centralising the Soviet economy to an even greater extent. This reform was also never fully implemented, and when Kosygin died in 1980 it was practically abandoned by his successor, Nikolai Tikhonov

Nikolai Aleksandrovich Tikhonov (russian: Николай Александрович Тихонов; ukr, Микола Олександрович Тихонов; – 1 June 1997) was a Soviet Russian-Ukrainian statesman during the Cold War. H ...

. Tikhonov told the Soviet people at the 26th Party Congress that the reform was to be implemented, or at least parts of it, during the Eleventh Five-Year Plan (1981–1985). Despite this, the reform never came to fruition. The reform is seen by several Sovietologists as the last major pre-'' perestroika'' reform initiative put forward by the Soviet government.

Kosygin's resignation

FollowingNikolai Podgorny

Nikolai Viktorovich Podgorny, ''Mykola Viktorovych Pidhornyy'' rus, Никола́й Ви́кторович Подго́рный, p=nʲɪkɐˈlaj ˈvʲiktərəvʲɪtɕ pɐdˈgornɨj, links=yes ( – 12 January 1983) was a Soviet statesman who ...

's removal from office, rumours started circulating within the top circles, and on the streets, that Kosygin would retire due to bad health. During one of Kosygin's spells on sick leave, Brezhnev appointed Nikolai Tikhonov

Nikolai Aleksandrovich Tikhonov (russian: Николай Александрович Тихонов; ukr, Микола Олександрович Тихонов; – 1 June 1997) was a Soviet Russian-Ukrainian statesman during the Cold War. H ...

, a like-minded conservative, to the post of First Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers

A council is a group of people who come together to consult, deliberate, or make decisions. A council may function as a legislature, especially at a town, city or county/ shire level, but most legislative bodies at the state/provincial or nati ...

; through this office Tikhonov was able to reduce Kosygin to a backup role. For example, at a Central Committee plenum in June 1980, the Soviet economic development plan was outlined by Tikhonov, not Kosygin. Following Kosygin's resignation in 1980, Tikhonov, at the age of 75, was elected the new Chairman of the Council of Ministers. At the end of his life, Kosygin feared the complete failure of the Eleventh Five-Year Plan (1981–1985), believing that the sitting leadership was reluctant to reform the stagnant Soviet economy.

Foreign relations

First World

Alexei Kosygin

Alexei Nikolayevich Kosygin ( rus, Алексе́й Никола́евич Косы́гин, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsʲej nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ kɐˈsɨɡʲɪn; – 18 December 1980) was a Soviet statesman during the Cold War. He served as the Premi ...

, the Soviet Premier, tried to challenge Brezhnev on the rights of the General Secretary to represent the country abroad, a function Kosygin believed should fall into the hands of the Premier, as was common in non-communist countries. This was actually implemented for a short period. Later, however, Kosygin, who had been the chief negotiator with the First World during the 1960s, was hardly to be seen outside the Second World

The Second World is a term originating during the Cold War for the industrial socialist states that were under the influence of the Soviet Union. In the first two decades following World War II, 19 communist states emerged; all of these were at ...

after Brezhnev strengthened his position within the Politburo. Kosygin did head the Soviet Glassboro Summit Conference

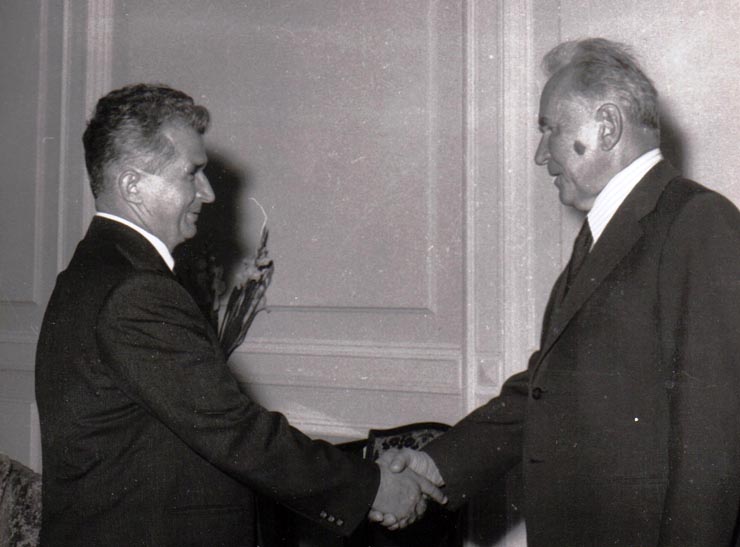

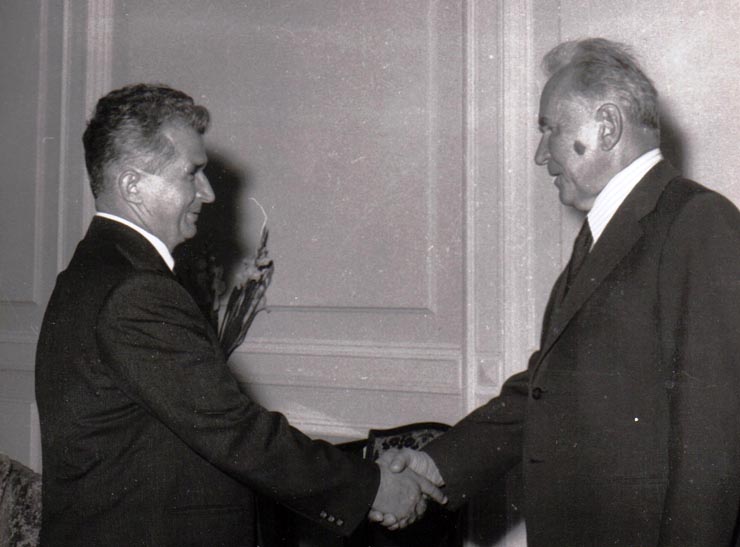

The Glassboro Summit Conference, usually just called the Glassboro Summit, was the 23–25 June 1967 meeting of the heads of government of the United States and the Soviet Union—President Lyndon B. Johnson and Premier Alexei Kosygin, respectiv ...

delegation in 1967 with Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

, the then-current President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

. The summit was dominated by three issues: the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam a ...

, the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab states (primarily Egypt, Syria, and Jordan) from 5 to 10 Ju ...

and the Soviet–American arms race. Immediately following the summit at Glassboro, Kosygin headed the Soviet delegation to Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

, where he met an angry Fidel Castro who accused the Soviet Union of "capitulationism".

''

''Détente

Détente (, French: "relaxation") is the relaxation of strained relations, especially political ones, through verbal communication. The term, in diplomacy, originates from around 1912, when France and Germany tried unsuccessfully to reduce ...

'', literally the easing of strained relations, or in Russian "unloading", was a Brezhnev initiative that characterized 1969 to 1974. It meant "ideological co-existence" in the context of Soviet foreign policy, but it did not, however, entail an end to competition between capitalist and communist societies. The Soviet leadership's policy did, however, help to ease the Soviet Union's strained relations with the United States. Several arms control and trade agreements were signed and ratified in this time period.

One such success of diplomacy came with Willy Brandt

Willy Brandt (; born Herbert Ernst Karl Frahm; 18 December 1913 – 8 October 1992) was a German politician and statesman who was leader of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) from 1964 to 1987 and served as the chancellor of West Ge ...

's ascension to the West German chancellorship in 1969, as West German–Soviet tension started to ease. Brandt's Ostpolitik

''Neue Ostpolitik'' (German for "new eastern policy"), or ''Ostpolitik'' for short, was the normalization of relations between the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG, or West Germany) and

Eastern Europe, particularly the German Democratic Republ ...

policy, along with Brezhnev's détente, contributed to the signing of the Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

and Warsaw Treaties in which West Germany recognized the state borders established following World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, which included West German recognition of East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

as an independent state. The foreign relations of the two countries continued to improve during Brezhnev's rule, and in the Soviet Union, where the memory of German brutality during World War II was still remembered, these developments contributed to greatly reducing the animosity the Soviet people felt towards Germany, and Germans in general.

Not all efforts were so successful, however. The 1975 Helsinki Accords

The Helsinki Final Act, also known as Helsinki Accords or Helsinki Declaration was the document signed at the closing meeting of the third phase of the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE) held in Helsinki, Finland, between ...

, a Soviet-led initiative which was hailed as a success for Soviet diplomacy, "backfired", in the words of historian Archie Brown. The U.S. Government retained little interest through the whole process, and Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

once told a senior British official that the United States "had never wanted the conference". Other notables, such as Nixon's successor President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Gerald Ford, and National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presid ...

were also unenthusiastic. It was Western European negotiators who played a crucial role in creating the treaty.

The Soviet Union sought an official acceptance of the state borders drawn up in post-war Europe by the United States and Western Europe. The Soviets were largely successful; some small differences were that state borders were "inviolable" rather than "immutable", meaning that borders could be changed only without military interference, or interference from another country. Both Brezhnev, Gromyko and the rest of the Soviet leadership were strongly committed to the creation of such a treaty, even if it meant concessions on such topics as human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

and transparency. Mikhail Suslov

Mikhail Andreyevich Suslov (russian: Михаи́л Андре́евич Су́слов; 25 January 1982) was a Soviet statesman during the Cold War. He served as Second Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1965, and as uno ...

and Gromyko, among others, were worried about some of the concessions. Yuri Andropov

Yuri Vladimirovich Andropov (– 9 February 1984) was the sixth paramount leader of the Soviet Union and the fourth General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. After Leonid Brezhnev's 18-year rule, Andropov served in the p ...

, the KGB Chairman, believed the greater transparency was weakening the prestige of the KGB, and strengthening the prestige of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Another blow to Soviet communism in the First World came with the establishment of

Another blow to Soviet communism in the First World came with the establishment of eurocommunism

Eurocommunism, also referred to as democratic communism or neocommunism, was a trend in the 1970s and 1980s within various Western European communist parties which said they had developed a theory and practice of social transformation more rel ...

. Eurocommunists espoused and supported the ideals of Soviet communism while at the same time supporting rights of the individual. The largest obstacle was that it was the largest communist parties, those with highest electoral turnout, which became eurocommunists. Originating with the Prague Spring, this new thinking made the First World more skeptical of Soviet communism in general. The Italian Communist Party

The Italian Communist Party ( it, Partito Comunista Italiano, PCI) was a communist political party in Italy.

The PCI was founded as ''Communist Party of Italy'' on 21 January 1921 in Livorno by seceding from the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) ...

notably declared that should war break out in Europe, they would rally to the defense of Italy and resist any Soviet incursion on their nation's soil.

In particular, Soviet–First World relations deteriorated when the US President Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 76th governor of Georgia from 1 ...

, following the advice of his National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski

Zbigniew Kazimierz Brzeziński ( , ; March 28, 1928 – May 26, 2017), or Zbig, was a Polish-American diplomat and political scientist. He served as a counselor to President Lyndon B. Johnson from 1966 to 1968 and was President Jimmy Carter' ...

, denounced the 1979 Soviet intervention in Afghanistan (see Soviet–Afghan relations) and described it as the "most serious danger to peace since 1945". The United States stopped all grain export to the Soviet Union and persuaded US athletes not to enter the 1980 Summer Olympics held in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

. The Soviet Union responded by boycotting the next Summer Olympics held in Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, largest city in the U.S. state, state of California and the List of United States cities by population, sec ...

. The détente policy collapsed. When Ronald Reagan succeeded Carter as US president in 1981, he promised a sharp increase in US defense spending and a more aggressively anti-Soviet foreign policy. This caused alarm in Moscow, with the Soviet media accusing him of "warmongering" and "mistakenly believing that stepping up the arms race will bring peace to the world". General Nikolai Ogarkov also commented that too many Soviet citizens had begun believing that any war was bad and peace at any price was good, and that better political education was necessary to inculcate a "class" point of view in world affairs.

An event of grave embarrassment to the Soviet Union came in October 1981 when one of its submarines ran aground near the Swedish naval base at Karlskrona. As this was a militarily sensitive location, Sweden took an aggressive stance on the incident, detaining the Whiskey-class sub for two weeks as they awaited an official explanation from Moscow. Eventually it was released, but Stockholm refused to accept Soviet claims that this was merely an accident, especially since numerous unidentified submarines had been spotted near the Swedish coast. Sweden also announced that radiation had been detected emanating from the submarine and they believed it to be carrying nuclear missiles. Moscow would neither confirm nor deny this and instead merely accused the Swedes of espionage.

China

In the aftermath of Khrushchev's removal and the

In the aftermath of Khrushchev's removal and the Sino-Soviet split

The Sino-Soviet split was the breaking of political relations between the China, People's Republic of China and the Soviet Union caused by Doctrine, doctrinal divergences that arose from their different interpretations and practical applications ...

, Alexei Kosygin

Alexei Nikolayevich Kosygin ( rus, Алексе́й Никола́евич Косы́гин, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsʲej nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ kɐˈsɨɡʲɪn; – 18 December 1980) was a Soviet statesman during the Cold War. He served as the Premi ...

was the most optimistic member of the Soviet leadership for a future rapprochement with China, while Yuri Andropov

Yuri Vladimirovich Andropov (– 9 February 1984) was the sixth paramount leader of the Soviet Union and the fourth General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. After Leonid Brezhnev's 18-year rule, Andropov served in the p ...

remained skeptical and Brezhnev did not even voice his opinion. In many ways, Kosygin even had problems understanding why the two countries were quarreling with each other in the first place. The collective leadership; Anastas Mikoyan, Brezhnev and Kosygin were considered by the PRC to retain the revisionist attitudes of their predecessor, Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

. At first, the new Soviet leadership blamed the Sino-Soviet split not on the PRC, but on policy errors made by Khrushchev. Both Brezhnev and Kosygin were enthusiastic for rapprochement with the PRC. When Kosygin met his counterpart, the Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai

Zhou Enlai (; 5 March 1898 – 8 January 1976) was a Chinese statesman and military officer who served as the first premier of the People's Republic of China from 1 October 1949 until his death on 8 January 1976. Zhou served under Chairman Ma ...

, in 1964, Kosygin found him to be in an "excellent mood". The early hints of rapprochement collapsed, however, when Zhou accused Kosygin of Khrushchev-like behavior after Rodion Malinovsky

Rodion Yakovlevich Malinovsky (russian: Родио́н Я́ковлевич Малино́вский, ukr, Родіо́н Я́кович Малино́вський ; – 31 March 1967) was a Soviet military commander. He was Marshal of the Sov ...

's anti-imperialistic

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic

...

speech against the First World.

When Kosygin told Brezhnev that it was time to reconcile with China, Brezhnev replied: "If you think this is necessary, then you go by yourself". Kosygin was afraid that China would turn down his proposal for a visit, so he decided to stop off in Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

on his way to Vietnamese Communist leaders in Hanoi

Hanoi or Ha Noi ( or ; vi, Hà Nội ) is the capital and second-largest city of Vietnam. It covers an area of . It consists of 12 urban districts, one district-leveled town and 17 rural districts. Located within the Red River Delta, Hanoi is ...

on 5 February 1965; there he met with Zhou. The two were able to solve smaller issues, agreeing to increase trade between the countries, as well as celebrate the 15th anniversary of the Sino-Soviet alliance. Kosygin was told that a reconciliation between the two countries might take years, and that rapprochement could occur only gradually. In his report to the Soviet leadership, Kosygin noted Zhou's moderate stance against the Soviet Union, and believed he was open for serious talks about Sino-Soviet relations. After his visit to Hanoi, Kosygin returned to Beijing on 10 February, this time to meet Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the founder of the People's Republic of China (PRC) ...

personally. At first Mao refused to meet Kosygin, but eventually agreed and the two met on 11 February. His meeting with Mao was in an entirely different tone to the previous meeting with Zhou. Mao criticized Kosygin, and the Soviet leadership, of revisionist behavior. He also continued to criticize Khrushchev's earlier policies. This meeting was to become Mao's last meeting with any Soviet leader.

The Cultural Revolution caused a complete meltdown of Sino-Soviet relations, inasmuch as Moscow (along with every communist state save for Albania) considered that event to be simple-minded insanity. Red Guards

Red Guards () were a mass student-led paramilitary social movement mobilized and guided by Chairman Mao Zedong in 1966 through 1967, during the first phase of the Cultural Revolution, which he had instituted.Teiwes According to a Red Guard lead ...

denounced the Soviet Union and the entire Eastern Bloc as revisionists who pursued a false socialism and of being in collusion with the forces of imperialism. Brezhnev was referred to as "the new Hitler" and the Soviets as warmongers who neglected their people's living standards in favor of military spending. In 1968 Lin Biao

)

, serviceyears = 1925–1971

, branch = People's Liberation Army

, rank = Marshal of the People's Republic of China Lieutenant general of the National Revolutionary Army, Republic of China

, commands ...

, the Chinese Defence Minister, claimed that the Soviet Union was preparing itself for a war against China. Moscow shot back by accusing China of false socialism and plotting with the US as well as promoting a guns-over-butter economic policy. This tension escalated into small skirmishes alongside the Sino-Soviet border, and both Khrushchev and Brezhnev were derided as "betrayers of ladimirLenin" by the Chinese. To counter the accusations made by the Chinese Central Government