History of the Jews in Italy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the Jews in Italy spans more than two thousand years to the present. The

The history of the Jews in Italy spans more than two thousand years to the present. The

''World Jewish Population''

American Jewish Committee, 2007.URL accessed 13 March 2013. As data originate from records kept by the various Italian Jewish congregations (which means they register "observant" Jews who have somehow had to go through basic rituals such as the

With the promotion of Christianity as a legal religion of the Roman Empire by Constantine in 313 (the

With the promotion of Christianity as a legal religion of the Roman Empire by Constantine in 313 (the

There were several expulsions, including a brief one from

There were several expulsions, including a brief one from

The position of Jews in Italy worsened considerably under Pope

The position of Jews in Italy worsened considerably under Pope

A great sensation was caused in Italy by the choice of a prominent Jew, Solomon of Udine, as Turkish ambassador to Venice who was selected to negotiate within that republic during July 1574. There was a pending decree of expulsion of the Jews by the leaders of several kingdoms within Italy, thereby making the

A great sensation was caused in Italy by the choice of a prominent Jew, Solomon of Udine, as Turkish ambassador to Venice who was selected to negotiate within that republic during July 1574. There was a pending decree of expulsion of the Jews by the leaders of several kingdoms within Italy, thereby making the

Among the first schools to adopt the Reform projects of

Among the first schools to adopt the Reform projects of

The return to medieval servitude after the Italian restoration did not last long; and the

The return to medieval servitude after the Italian restoration did not last long; and the

A significant train of thought inside Italian Fascism, influenced by

A significant train of thought inside Italian Fascism, influenced by

The Catholic Church and Racial Laws

L'Osservatore Romano. Weekly Edition in English, 14 January 2009, p.10 In September of that year in a Pope Pius XI and Judaism#Speech to Belgian pilgrims 1938, speech to Belgian pilgrims, Pius XI proclaimed:

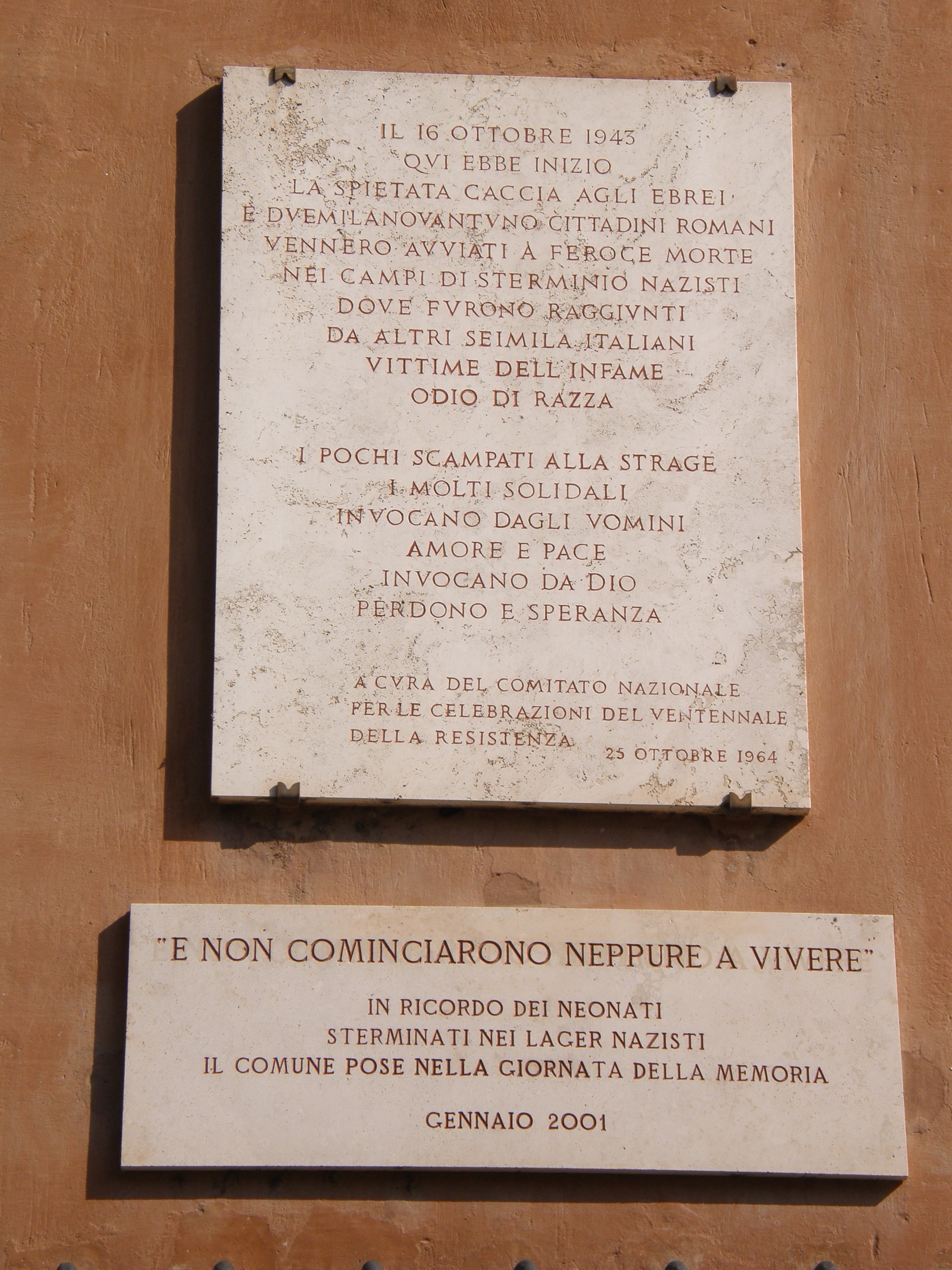

In 2007 the Jewish population in Italy numbered around 45–46,000 people, decreased to 42,850 in 2015 (36,150 with Italian citizenship) and to 41,200 in 2017 (36,600 with Italian citizenship and 25–28,000 affiliated with the Union of Italian Jewish Communities), mainly because of low birth rates and emigration due to the financial crisis. There have been occasional antisemitic incidents in the last decades. On 13 December 2017 the Museum of Italian Judaism and the Shoah (MEIS) was inaugurated in Ferrara. The museum traces the history of the Jewish people in Italy starting from the Roman Empire, Roman empire, and going through the Holocaust during the 20th century.

In 2007 the Jewish population in Italy numbered around 45–46,000 people, decreased to 42,850 in 2015 (36,150 with Italian citizenship) and to 41,200 in 2017 (36,600 with Italian citizenship and 25–28,000 affiliated with the Union of Italian Jewish Communities), mainly because of low birth rates and emigration due to the financial crisis. There have been occasional antisemitic incidents in the last decades. On 13 December 2017 the Museum of Italian Judaism and the Shoah (MEIS) was inaugurated in Ferrara. The museum traces the history of the Jewish people in Italy starting from the Roman Empire, Roman empire, and going through the Holocaust during the 20th century.

Fascist Italy and the Jews: Myth versus Reality

an online lecture by Dr. Iael Nidam-Orvieto of Yad Vashem

Listing of all Jewish synagogues, schools, restaurants, etc... in Italy

19 November 1999 * [https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/History/italytime.html Italy and the Jews – Timeline] Jewish Virtual Library

Chabad-Lubavitch Centers in Italy

{{DEFAULTSORT:History of the Jews in Italy Judaism in Italy, . Jewish Italian history,

The history of the Jews in Italy spans more than two thousand years to the present. The

The history of the Jews in Italy spans more than two thousand years to the present. The Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

presence in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

dates to the pre-Christian Roman period

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

and has continued, despite periods of extreme persecution and expulsions, until the present. As of 2019, the estimated core Jewish population in Italy numbers around 45,000.As reported by the ''American Jewish Yearbook'' (2007), on a total Italian population of circa 60 million people, which therefore is approx. 0.075%. Greater concentrations are in Rome and Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city ...

. Cf. the demographic

Demography () is the statistical study of populations, especially human beings.

Demographic analysis examines and measures the dimensions and dynamics of populations; it can cover whole societies or groups defined by criteria such as ed ...

statistics by Sergio DellaPergola

Sergio Della Pergola ( he, סרג'ו דלה-פרגולה; born September 7, 1942, in Trieste, Italy) is an Italian-Israeli demographer and statistician. He is a professor and demographic expert, specifically in demography and statistics related t ...

, published o''World Jewish Population''

American Jewish Committee, 2007.URL accessed 13 March 2013. As data originate from records kept by the various Italian Jewish congregations (which means they register "observant" Jews who have somehow had to go through basic rituals such as the

Brit Milah

The ''brit milah'' ( he, בְּרִית מִילָה ''bərīṯ mīlā'', ; Ashkenazi pronunciation: , " covenant of circumcision"; Yiddish pronunciation: ''bris'' ) is the ceremony of circumcision in Judaism. According to the Book of Genes ...

or Bar/Bat Mitzvah etc.). Excluded are therefore "ethnic Jews", lay Jews, atheist/agnostic Jews, ''et al''. – cfr. " Who is a Jew?". If these are added, then the total population would increase, possibly to approx. 45,000 Jews in Italy, not counting recent migrations from North Africa and Eastern Europe.

Pre-Christian Rome

The Jewish community inRome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

is likely one of the oldest continuous Jewish communities in the world, existing from classical times through to today.

It is known more certainly that a Hasmonean embassy was sent by Simon Maccabeus

Simon Thassi ( he, ''Šīməʿōn haTassī''; died 135) was the second son of Mattathias and thus a member of the Hasmonean family.

Names

The name "Thassi" has a connotation of "the Wise", a title which can also mean "the Director", "the G ...

to Rome in 139 BCE to strengthen the alliance with the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

against the Hellenistic Seleucid kingdom. The ambassadors received a cordial welcome from their coreligionists already established in Rome.

Large numbers of Jews lived in Rome even during the late Roman Republican period (from around 150 BC). They were largely Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

-speaking and poor. As Rome had increasing contact with and military/trade dealings with the Greek-speaking Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

, during the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE, many Greeks, as well as Jews, came to Rome as merchants or were brought there as slaves.

The Romans appear to have viewed the Jews as followers of peculiar, backward religious customs, but antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

as it would come to be in the Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι� ...

and Islamic world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. I ...

s did not exist (see Anti-Judaism in the pre-Christian Roman Empire). Despite their disdain, the Romans did recognize and respect the antiquity of the Jews' religion and the fame of their Temple in Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

(Herod's Temple

The Second Temple (, , ), later known as Herod's Temple, was the reconstructed Temple in Jerusalem between and 70 CE. It replaced Solomon's Temple, which had been built at the same location in the United Kingdom of Israel before being inherited ...

). Many Romans did not know much about Judaism, including the emperor Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

who, according to his biographer Suetonius

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus (), commonly referred to as Suetonius ( ; c. AD 69 – after AD 122), was a Roman historian who wrote during the early Imperial era

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τ� ...

, thought that Jews fasted on the sabbath

In Abrahamic religions, the Sabbath () or Shabbat (from Hebrew ) is a day set aside for rest and worship. According to the Book of Exodus, the Sabbath is a day of rest on the seventh day, commanded by God to be kept as a holy day of rest, as ...

. Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

was known as a great friend to the Jews, and they were among the first to mourn his assassination

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have ...

.

In Rome, the community was highly organized, and presided over by heads called άρχοντες (''archontes'') or γερουσιάρχοι (''gerousiarchoi''). The Jews maintained in Rome several synagogues, whose spiritual leader was called αρχισυνάγωγος (''archisunagogos''). Their tombstones, mostly in Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

with a few in Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

/Aramaic

The Aramaic languages, short Aramaic ( syc, ܐܪܡܝܐ, Arāmāyā; oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; tmr, אֲרָמִית), are a language family containing many varieties (languages and dialects) that originated i ...

or Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

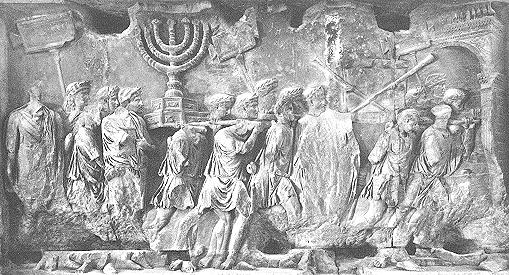

, were decorated with the ritual menorah (seven-branched candelabrum).

Some scholars have previously argued that Jews in the pre-Christian Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

were active in proselytising

Proselytism () is the policy of attempting to convert people's religious or political beliefs. Proselytism is illegal in some countries.

Some draw distinctions between ''evangelism'' or ''Da‘wah'' and proselytism regarding proselytism as involu ...

Romans in Judaism, leading to an increasing number of outright converts

Religious conversion is the adoption of a set of beliefs identified with one particular religious denomination to the exclusion of others. Thus "religious conversion" would describe the abandoning of adherence to one denomination and affiliatin ...

. The new consensus is, that this is not the case. According to Erich S. Gruen

Erich Stephen Gruen ( , ; born May 7, 1935) is an American classicist and ancient historian. He was the Gladys Rehard Wood Professor of History and Classics at the University of California, Berkeley, where he taught full-time from 1966 until 2008 ...

, though conversions did happen, there is no evidence of Jews trying to convert Gentiles to Judaism. It has also been argued that some people adopted some Jewish practices and belief in the Jewish God without actually converting (called God-fearer

God-fearers ( grc-x-koine, φοβούμενοι τὸν Θεόν, ''phoboumenoi ton Theon'') or God-worshippers ( grc-x-koine, θεοσεβεῖς, ''Theosebeis'') were a numerous class of Gentile sympathizers to Hellenistic Judaism that existed ...

s).

The fate of Jews in Rome and Italy fluctuated, with partial expulsions being carried out under the emperors Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus (; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was the second Roman emperor. He reigned from AD 14 until 37, succeeding his stepfather, the first Roman emperor Augustus. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC. His father ...

and Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (; 1 August 10 BC – 13 October AD 54) was the fourth Roman emperor, ruling from AD 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, Claudius was born to Drusus and Antonia Minor ...

. After the successive Jewish revolts of 66 and 132 CE, many Judea

Judea or Judaea ( or ; from he, יהודה, Standard ''Yəhūda'', Tiberian ''Yehūḏā''; el, Ἰουδαία, ; la, Iūdaea) is an ancient, historic, Biblical Hebrew, contemporaneous Latin, and the modern-day name of the mountainous so ...

n Jews were brought to Rome as slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

(the norm in the ancient world was for prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

and inhabitants of defeated cities to be sold as slaves). These revolts caused increasing official hostility from the reign of Vespasian

Vespasian (; la, Vespasianus ; 17 November AD 9 – 23/24 June 79) was a Roman emperor who reigned from AD 69 to 79. The fourth and last emperor who reigned in the Year of the Four Emperors, he founded the Flavian dynasty that ruled the Emp ...

onwards. The most serious measure was the Fiscus Judaicus, which was a tax payable by all Jews in the Roman Empire. The new tax replaced the tithe

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash or cheques or more ...

that had formerly been sent to the Temple in Jerusalem

The Temple in Jerusalem, or alternatively the Holy Temple (; , ), refers to the two now-destroyed religious structures that served as the central places of worship for Israelites and Jews on the modern-day Temple Mount in the Old City of Jeru ...

(destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE), and was used instead in the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus

The Capitoline Triad was a group of three deities who were worshipped in ancient Roman religion in an elaborate temple on Rome's Capitoline Hill (Latin ''Capitolium''). It comprised Jupiter, Juno and Minerva. The triad held a central place in th ...

in Rome.

In addition to Rome, there were a significant number of Jewish communities in southern Italy

Southern Italy ( it, Sud Italia or ) also known as ''Meridione'' or ''Mezzogiorno'' (), is a macroregion of the Italian Republic consisting of its southern half.

The term ''Mezzogiorno'' today refers to regions that are associated with the pe ...

during this period. For example, the regions of Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, Calabria

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

, and Apulia

it, Pugliese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographic ...

had well established Jewish populations.

Late antiquity

Edict of Milan

The Edict of Milan ( la, Edictum Mediolanense; el, Διάταγμα τῶν Μεδιολάνων, ''Diatagma tōn Mediolanōn'') was the February 313 AD agreement to treat Christians benevolently within the Roman Empire. Frend, W. H. C. ( ...

), the position of Jews in Italy and throughout the empire declined rapidly and dramatically. Constantine established oppressive laws for the Jews; but these were in turn abolished by Julian the Apostate

Julian ( la, Flavius Claudius Julianus; grc-gre, Ἰουλιανός ; 331 – 26 June 363) was Roman emperor from 361 to 363, as well as a notable philosopher and author in Greek. His rejection of Christianity, and his promotion of Neoplat ...

, who showed his favor toward the Jews to the extent of permitting them to resume their plan for the reconstruction of the Temple at Jerusalem. This concession was withdrawn under his successor, who, again, was a Christian; and then the oppression grew considerably. Nicene

The original Nicene Creed (; grc-gre, Σύμβολον τῆς Νικαίας; la, Symbolum Nicaenum) was first adopted at the First Council of Nicaea in 325. In 381, it was amended at the First Council of Constantinople. The amended form is a ...

Christianity was adopted as the state church of the Roman Empire

Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire when Emperor Theodosius I issued the Edict of Thessalonica in 380, which recognized the catholic orthodoxy of Nicene Christians in the Great Church as the Roman Empire's state religion ...

in 380, shortly before the fall of the Western Roman Empire

The fall of the Western Roman Empire (also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome) was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its va ...

.

At the time of the foundation of the Ostrogoth

The Ostrogoths ( la, Ostrogothi, Austrogothi) were a Roman-era Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Gothic kingdoms within the Roman Empire, based upon the large Gothic populations who ...

ic rule under Theodoric

Theodoric is a Germanic given name. First attested as a Gothic name in the 5th century, it became widespread in the Germanic-speaking world, not least due to its most famous bearer, Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths.

Overview

The name ...

(493–526), there were flourishing communities of Jews in Rome, Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city ...

, Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

, Palermo

Palermo ( , ; scn, Palermu , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital of both the autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan province. The city is noted for its ...

, Messina

Messina (, also , ) is a harbour city and the capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of more than 219,000 inhabitants in t ...

, Agrigentum, and in Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label= Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, aft ...

. The Popes

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

of the period were not seriously opposed to the Jews; and this accounts for the ardor with which the latter took up arms for the Ostrogoths as against the forces of Justinian

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized '' renova ...

—particularly at Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

, where the remarkable defense of the city was maintained almost entirely by Jews. After the failure of the various attempts to make Italy a province of the Byzantine empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

, the Jews had to suffer much oppression from the Exarch

An exarch (;

from Ancient Greek ἔξαρχος ''exarchos'', meaning “leader”) was the holder of any of various historical offices, some of them being political or military and others being ecclesiastical.

In the late Roman Empire and ea ...

of Ravenna

Ravenna ( , , also ; rgn, Ravèna) is the capital city of the Province of Ravenna, in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy. It was the capital city of the Western Roman Empire from 408 until its collapse in 476. It then served as the c ...

; but it was not long until the greater part of Italy came into the possession of the Lombards (568-774), under whom they lived in peace. Indeed, the Lombards passed no exceptional laws relative to the Jews. Even after the Lombards embraced Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

the condition of the Jews was always favorable, because the popes of that time not only did not persecute them, but guaranteed them more or less protection. Pope Gregory I

Pope Gregory I ( la, Gregorius I; – 12 March 604), commonly known as Saint Gregory the Great, was the bishop of Rome from 3 September 590 to his death. He is known for instigating the first recorded large-scale mission from Rome, the Gregoria ...

treated them with much consideration. Under succeeding popes the condition of the Jews did not grow worse; and the same was the case in the several smaller states into which Italy was divided. Both popes and states were so absorbed in continual external and internal dissensions that the Jews were left in peace. In every individual state of Italy a certain amount of protection was granted to them in order to secure the advantages of their commercial enterprise. The fact that the historians of this period scarcely make mention of the Jews, suggests that their circumstances were tolerable.

Middle Ages

There were several expulsions, including a brief one from

There were several expulsions, including a brief one from Bologna

Bologna (, , ; egl, label= Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bononia) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different na ...

in 1172, and forced conversions: in Trani in 1380 there were four synagogues, transformed into churches at the time of Charles III of Naples, while 310 local Jews were forced to be baptized. A nephew of Rabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as '' semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form o ...

Nathan ben Jehiel

Nathan ben Jehiel of Rome (Hebrew: נתן בן יחיאל מרומי; ''Nathan ben Y'ḥiel Mi Romi'' according to Sephardic pronunciation) ( 1035 – 1106) was a Jewish Italian lexicographer. He authored the Arukh, a notable dictionary of Talmu ...

acted as administrator of the property of Pope Alexander III

Pope Alexander III (c. 1100/1105 – 30 August 1181), born Roland ( it, Rolando), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 7 September 1159 until his death in 1181.

A native of Siena, Alexander became pope after a con ...

, who showed his amicable feelings toward the Jews at the Lateran Council of 1179. He defeated the designs of hostile prelates who advocated anti-Jewish laws. Under Norman rule, the Jews of southern Italy and of Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

enjoyed even greater freedom; they were considered the equals of Christians, and were permitted to follow any career. They also had jurisdiction over their own affairs. The canonical laws against the Jews were more frequently disregarded in Italy than in any other country or region. A later pope—either Nicholas IV (1288–1292) or Boniface VIII (1294–1303)—had a Jewish physician, Isaac ben Mordecai, nicknamed Maestro Gajo.

Literary achievement

Among the early Jews of Italy who left written manuscripts was Shabbethai Donnolo (died 982). Two centuries later (1150), poets Shabbethai ben Moses of Rome; his son Jehiel Kalonymus, once regarded as aTalmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law ('' halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the ce ...

ic authority even beyond Italy; and Rabbi Jehiel of the Mansi (Anaw) family, also of Rome, became known for their works. Their compositions are full of thought, but their diction is rather crude. Nathan, son of the above-mentioned Rabbi Jehiel, was the author of a Talmudic lexicon ("'Aruk") that became the key to the study of the Talmud.

During his residence at Salerno

Salerno (, , ; nap, label= Salernitano, Saliernë, ) is an ancient city and ''comune'' in Campania (southwestern Italy) and is the capital of the namesake province, being the second largest city in the region by number of inhabitants, after ...

, Solomon ben Abraham ibn Parhon compiled a Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

dictionary

A dictionary is a listing of lexemes from the lexicon of one or more specific languages, often arranged alphabetically (or by radical and stroke for ideographic languages), which may include information on definitions, usage, etymologie ...

. This encouraged Italian Jews

Italian Jews ( it, Ebrei Italiani, he, יהודים איטלקים ''Yehudim Italkim'') or Roman Jews ( it, Ebrei Romani, he, יהודים רומים ''Yehudim Romim'') can be used in a broad sense to mean all Jews living in or with roots in I ...

to study Biblical exegesis

Biblical criticism is the use of critical analysis to understand and explain the Bible. During the eighteenth century, when it began as ''historical-biblical criticism,'' it was based on two distinguishing characteristics: (1) the concern to ...

. On the whole, however, Hebrew literary culture was not flourishing. The only liturgical author of merit was Joab ben Solomon, some of whose compositions are extant.

Toward the second half of the 13th century, signs appeared of a better Hebrew culture and of a more profound study of the Talmud. Isaiah di Trani the Elder (1232–1279), a high Talmudic authority, wrote many celebrated responsa

''Responsa'' (plural of Latin , 'answer') comprise a body of written decisions and rulings given by legal scholars in response to questions addressed to them. In the modern era, the term is used to describe decisions and rulings made by scholars ...

. David, his son, and Isaiah di Trani the Younger

Isaiah ben Elijah di Trani (the Younger) (Hebrew: ישעיה בן אליהו דטראני) was an Italian Talmudist and commentator who lived in the 13th century. He was the grandson, on his mother's side, of Isaiah (ben Mali) di Trani the Elde ...

, his nephew, followed in his footsteps, as did their descendants until the end of the seventeenth century. Meïr ben Moses presided over an important Talmudic school in Rome, and Abraham ben Joseph over one in Pesaro. In Rome two famous physicians, Abraham and Jehiel, descendants of Nathan ben Jehiel, taught the Talmud. Paola dei Mansi, one of the women of this gifted family, also attained distinction; she had considerable knowledge of the Bible and Talmud, and she transcribed Biblical commentaries in a notably beautiful handwriting (see Jew. Encyc. i. 567, s.v. Paola Anaw).

During this period, the Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

Frederick II, the last of the Hohenstaufen

The Hohenstaufen dynasty (, , ), also known as the Staufer, was a noble family of unclear origin that rose to rule the Duchy of Swabia from 1079, and to royal rule in the Holy Roman Empire during the Middle Ages from 1138 until 1254. The dynas ...

, employed Jews to translate from the Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

philosophical and astronomical

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, galaxi ...

treatises. Among the translators were Judah ben Solomon ha-Kohen Judah ben Solomon ha-Kohen (ibn Matkah) ( he, יְהוּדָה בְּן שְׁלֹמֹה הכֹּהֵן (אִבְּן מתקה); 1215– 1274) was a thirteenth-century Spanish Jewish philosopher, astronomer, and mathematician. He was the author of ...

of Toledo, later of Tuscany

it, Toscano (man) it, Toscana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Citizenship

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 = Italian

, demogra ...

, and Jacob Anatoli of Provence

Provence (, , , , ; oc, Provença or ''Prouvènço'' , ) is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which extends from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the Italian border to the east; it is bo ...

. This encouragement naturally led to the study of the works of Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah ...

—particularly of the "Moreh Nebukim

''The Guide for the Perplexed'' ( ar, دلالة الحائرين, Dalālat al-ḥā'irīn, ; he, מורה נבוכים, Moreh Nevukhim) is a work of Jewish theology by Maimonides. It seeks to reconcile Aristotelianism with Rabbinical Jewish t ...

"—the favorite writer of Hillel of Verona (1220–1295). This last-named litterateur and philosopher practised medicine at Rome and in other Italian cities, and translated several medical works into Hebrew. The liberal spirit of the writings of Maimonides had other votaries in Italy; e.g., Shabbethai ben Solomon of Rome and Zerahiah Ḥen of Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

, who migrated to Rome and contributed much to spread the knowledge of his works. The effect of this on the Italian Jews was apparent in their love of freedom of thought and their esteem for literature, as well as in their adherence to the literal rendering of the Biblical texts and their opposition to fanatical cabalists and mystic theories. Among other devotees of these theories was Immanuel ben Solomon of Rome, the celebrated friend of Dante Aligheri. The discord between the followers of Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah ...

and his opponents wrought most serious damage to the interests of Judaism.

The rise of poetry in Italy at the time of Dante influenced the Jews also. The rich and the powerful, partly by reason of sincere interest, partly in obedience to the spirit of the times, became patrons of Jewish writers, thus inducing the greatest activity on their part. This activity was particularly noticeable at Rome, where a new Jewish poetry arose, mainly through the works of Leo Romano, translator of the writings of Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, Dominican Order, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino, Italy, Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest who was an influential List of Catholic philo ...

and author of exegetical works of merit; of Judah Siciliano, a writer in rimed prose; of Kalonymus ben Kalonymus Kalonymus ben Kalonymus ben Meir (Hebrew: קלונימוס בן קלונימוס), also romanized as Qalonymos ben Qalonymos or Calonym ben Calonym, also known as Maestro Calo (Arles, 1286 – died after 1328) was a Jewish philosopher and transl ...

, a famous satirical

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of shaming or ...

poet; and especially of the above-mentioned Immanuel. On the initiative of the Roman community, a Hebrew translation of Maimonides' Arabic commentary on the Mishnah

The Mishnah or the Mishna (; he, מִשְׁנָה, "study by repetition", from the verb ''shanah'' , or "to study and review", also "secondary") is the first major written collection of the Jewish oral traditions which is known as the Oral Tor ...

was made. At this time Pope John XXII was on the point of pronouncing a ban against the Jews of Rome. The Jews instituted a day of public fasting and of prayer to appeal for divine assistance. King Robert of Sicily, who favored the Jews, sent an envoy to the pope at Avignon

Avignon (, ; ; oc, Avinhon, label= Provençal or , ; la, Avenio) is the prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of Southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the commune had ...

, who succeeded in averting this great peril. Immanuel himself described this envoy as a person of high merit and of great culture. This period of Jewish literature in Italy is indeed one of great splendor. After Immanuel there were no other Jewish writers of importance until Moses da Rieti (1388).

Worsening conditions under Innocent III

The position of Jews in Italy worsened considerably under Pope

The position of Jews in Italy worsened considerably under Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III ( la, Innocentius III; 1160 or 1161 – 16 July 1216), born Lotario dei Conti di Segni (anglicized as Lothar of Segni), was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 to his death in 16 ...

(1198–1216). This pope threatened with excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

those who placed or maintained Jews in public positions, and he insisted that every Jew holding office should be dismissed. The deepest insult was the order that every Jew must always wear, conspicuously displayed, a special yellow badge

Yellow badges (or yellow patches), also referred to as Jewish badges (german: Judenstern, lit=Jew's star), are badges that Jews were ordered to wear at various times during the Middle Ages by some caliphates, at various times during the Medieva ...

.

In 1235 Pope Gregory IX published the first bull against the ritual murder accusation. Other popes followed his example, particularly Innocent IV

Pope Innocent IV ( la, Innocentius IV; – 7 December 1254), born Sinibaldo Fieschi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 25 June 1243 to his death in 1254.

Fieschi was born in Genoa and studied at the universitie ...

in 1247, Gregory X

Pope Gregory X ( la, Gregorius X; – 10 January 1276), born Teobaldo Visconti, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1 September 1271 to his death and was a member of the Secular Franciscan Order. He w ...

in 1272, Clement VI

Pope Clement VI ( la, Clemens VI; 1291 – 6 December 1352), born Pierre Roger, was head of the Catholic Church from 7 May 1342 to his death in December 1352. He was the fourth Avignon pope. Clement reigned during the first visitation of the Bl ...

in 1348, Gregory XI

Pope Gregory XI ( la, Gregorius, born Pierre Roger de Beaufort; c. 1329 – 27 March 1378) was head of the Catholic Church from 30 December 1370 to his death in March 1378. He was the seventh and last Avignon pope and the most recent French po ...

in 1371, Martin V in 1422, Nicholas V

Pope Nicholas V ( la, Nicholaus V; it, Niccolò V; 13 November 1397 – 24 March 1455), born Tommaso Parentucelli, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 6 March 1447 until his death in March 1455. Pope Eugene made ...

in 1447, Sixtus V in 1475, Paul III in 1540, and later Alexander VII

Pope Alexander VII ( it, Alessandro VII; 13 February 159922 May 1667), born Fabio Chigi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 7 April 1655 to his death in May 1667.

He began his career as a vice-papal legate, an ...

, Clement XIII, and Clement XIV.

Antipope Benedict XIII

The Jews suffered much from the relentless persecutions of theAvignon

Avignon (, ; ; oc, Avinhon, label= Provençal or , ; la, Avenio) is the prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of Southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the commune had ...

-based antipope Benedict XIII

Pedro Martínez de Luna y Pérez de Gotor (25 November 1328 – 23 May 1423), known as in Spanish and Pope Luna in English, was an Aragonese nobleman who, as Benedict XIII, is considered an antipope (see Western Schism) by the Catholic Church ...

. They hailed his successor, Martin V, with delight. The synod convoked by the Jews at Bologna, and continued at Forlì

Forlì ( , ; rgn, Furlè ; la, Forum Livii) is a '' comune'' (municipality) and city in Emilia-Romagna, Northern Italy, and is the capital of the province of Forlì-Cesena. It is the central city of Romagna.

The city is situated along the Vi ...

, sent a deputation with costly gifts to the new pope, praying him to abolish the oppressive laws promulgated by Benedict and to grant the Jews those privileges which had been accorded them under previous popes. The deputation succeeded in its mission, but the period of grace was short; for Martin's successor, Eugenius IV, at first favorably disposed toward the Jews, ultimately reenacted all the restrictive laws issued by Benedict. In Italy, however, his bull was generally disregarded. The great centers, such as Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

, Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

, Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

, and Pisa

Pisa ( , or ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for its leaning tower, the ci ...

, realized that their commercial interests were of more importance than the affairs of the spiritual leaders of the Church; and accordingly the Jews, many of whom were bankers and leading merchants, found their condition better than ever before. It thus became easy for Jewish bankers to obtain permission to establish banks and to engage in monetary transactions. Indeed, in one instance even the Bishop of Mantua

The Diocese of Mantua ( la, Dioecesis Mantuana) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the Catholic Church in Italy. The diocese existed at the beginning of the 8th century, though the earliest attested bishop is Laiulfus (827) ...

, in the name of the pope, accorded permission to the Jews to lend money at interest. All the banking negotiations of Tuscany were in the hands of a Jew, Jehiel of Pisa. The influential position of this successful financier was of the greatest advantage to his coreligionists at the time of the exile from Spain.

The Jews were also successful as skilled medical practitioners. William of Portaleone, physician to King Ferdinand I of Naples

Ferdinando Trastámara d'Aragona, of the Naples branch, universally known as Ferrante and also called by his contemporaries Don Ferrando and Don Ferrante (2 June 1424, in Valencia – 25 January 1494, in Naples), was the only son, illegitimate, of ...

, and to the ducal houses of Sforza

The House of Sforza () was a ruling family of Renaissance Italy, based in Milan. They acquired the Duchy of Milan following the extinction of the Visconti family in the mid-15th century, Sforza rule ending in Milan with the death of the last m ...

and Gonzaga, was one of the ablest of that time. He was the first of the long line of illustrious physicians in his family.

Early modern period

It is estimated that in 1492 Jews made up between 3% and 6% of the population ofSicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

. Many Sicilian Jews first went to Calabria

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

, which already had a Jewish community since the 4th century. In 1524 Jews were expelled from Calabria, and in 1540 from the entire Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples ( la, Regnum Neapolitanum; it, Regno di Napoli; nap, Regno 'e Napule), also known as the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was ...

, as all these areas fell under Spanish rule and were subject to the edict of expulsion by the Spanish Inquisition.

Throughout the 16th century, Jews gradually moved from the south of Italy to the north, with conditions worsening for Jews in Rome after 1556 and the Venetian Republic

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

in the 1580s. Many Jews from Venice and the surrounding area migrated to the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

at this time.

Refugees from Spain

When Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492, many of them found refuge in Italy, where they were given protection by KingFerdinand I of Naples

Ferdinando Trastámara d'Aragona, of the Naples branch, universally known as Ferrante and also called by his contemporaries Don Ferrando and Don Ferrante (2 June 1424, in Valencia – 25 January 1494, in Naples), was the only son, illegitimate, of ...

. One of the refugees, Don Isaac Abravanel

Isaac ben Judah Abarbanel ( he, יצחק בן יהודה אברבנאל; 1437–1508), commonly referred to as Abarbanel (), also spelled Abravanel, Avravanel, or Abrabanel, was a Portuguese Jewish statesman, philosopher, Bible commentato ...

, even received a position at the Neapolitan court, which he retained under the succeeding king, Alfonso II. The Spanish Jews were also well received in Ferrara

Ferrara (, ; egl, Fràra ) is a city and ''comune'' in Emilia-Romagna, northern Italy, capital of the Province of Ferrara. it had 132,009 inhabitants. It is situated northeast of Bologna, on the Po di Volano, a branch channel of the main stream ...

by Duke Ercole d'Este I and in Tuscany

it, Toscano (man) it, Toscana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Citizenship

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 = Italian

, demogra ...

through the mediation of Jehiel of Pisa and his sons. But at Rome and Genoa they experienced all the vexations and torments that hunger, plague, and poverty bring with them, and they were forced to accept baptism to escape starvation. In a few cases, the refugees exceeded in number the Jews already domiciled, and thus gave the determining vote in matters of communal interest and in the direction of studies.

Popes Alexander VI

Pope Alexander VI ( it, Alessandro VI, va, Alexandre VI, es, Alejandro VI; born Rodrigo de Borja; ca-valencia, Roderic Llançol i de Borja ; es, Rodrigo Lanzol y de Borja, lang ; 1431 – 18 August 1503) was head of the Catholic Chur ...

to Clement VII were indulgent toward Jews, having more urgent matters to occupy them. After the 1492 expulsion of Jews from Spain, some 9,000 impoverished Spanish Jews arrived at the borders of the Papal States. Alexander VI welcomed them into Rome, declaring that they were "permitted to lead their life, free from interference from Christians, to continue in their own rites, to gain wealth, and to enjoy many other privileges." He similarly allowed the immigration of Jews expelled from Portugal in 1497 and from Provence in 1498.

The popes and many of the most influential cardinals openly violated one of the most severe enactments of the Council of Basel

The Council of Florence is the seventeenth ecumenical council recognized by the Catholic Church, held between 1431 and 1449. It was convoked as the Council of Basel by Pope Martin V shortly before his death in February 1431 and took place in ...

, namely, that prohibiting Christians from employing Jewish physicians; they even gave the latter positions at the papal court. The Jewish communities of Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

and of Rome received the greatest number of accessions; but many Jews passed on from these cities to Ancona

Ancona (, also , ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region in central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona and of the region. The city is located northeast of Rome, on the Adriatic ...

, Venice, Calabria, and thence to Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

and Padua

Padua ( ; it, Padova ; vec, Pàdova) is a city and ''comune'' in Veneto, northern Italy. Padua is on the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice. It is the capital of the province of Padua. It is also the economic and communications hub of the ...

. Venice, imitating the odious measures of the German cities, assigned to the Jews a special quarter (ghetto

A ghetto, often called ''the'' ghetto, is a part of a city in which members of a minority group live, especially as a result of political, social, legal, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished ...

).

Expulsion from Naples

The ultra-Catholic party tried with all the means at its disposal to introduce theInquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

into the Neapolitan realm, then under Spanish rule. Charles V, upon his return from his victories in Africa, was on the point of exiling the Jews from Naples when Benvenida, wife of Samuel Abravanel, caused him to defer the action. A few years later, in 1533, a similar decree was proclaimed, but upon this occasion also Samuel Abravanel and others were able through their influence to avert for several years the execution of the edict. Many Jews repaired to the Ottoman Empire, some to Ancona, and still others to Ferrara

Ferrara (, ; egl, Fràra ) is a city and ''comune'' in Emilia-Romagna, northern Italy, capital of the Province of Ferrara. it had 132,009 inhabitants. It is situated northeast of Bologna, on the Po di Volano, a branch channel of the main stream ...

, where they were received graciously by Duke Ercole II.

After the death of Pope Paul III (1534–1549), who had showed favor to the Jews, a period of strife, persecution, and despondency set in. A few years later the Jews were exiled from Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

, among the refugees being Joseph Hakohen, physician to the doge

A doge ( , ; plural dogi or doges) was an elected lord and head of state in several Italian city-states, notably Venice and Genoa, during the medieval and renaissance periods. Such states are referred to as " crowned republics".

Etymology

The ...

Andrea Doria

Andrea Doria, Prince of Melfi (; lij, Drîa Döia ; 30 November 146625 November 1560) was a Genoese statesman, ', and admiral, who played a key role in the Republic of Genoa during his lifetime.

As the ruler of Genoa, Doria reformed the Rep ...

and eminent historian. Duke Ercole allowed the Maranos

Marranos were Spanish and Portuguese Jews living in the Iberian Peninsula who converted or were forced to convert to Christianity during the Middle Ages, but continued to practice Judaism in secrecy.

The term specifically refers to the charg ...

, driven from Spain and Portugal, to enter his dominions and to profess Judaism freely and openly. Samuel Usque, also a historian, who had fled from the Portuguese Inquisition

The Portuguese Inquisition ( Portuguese: ''Inquisição Portuguesa''), officially known as the General Council of the Holy Office of the Inquisition in Portugal, was formally established in Portugal in 1536 at the request of its king, John III. ...

, settled in Ferrara, and Abraham Usque

Abraham ben Salomon Usque (given the Christian name ''Duarte Pinhel'') was a 16th-century publisher. Usque was born in Portugal to a Jewish family and fled the Portuguese Inquisition for Ferrara, Italy, around 1543.

In Ferrara, Usque worked w ...

founded a large printing establishment there. A third Usque, Solomon

Solomon (; , ),, ; ar, سُلَيْمَان, ', , ; el, Σολομών, ; la, Salomon also called Jedidiah (Hebrew language, Hebrew: , Modern Hebrew, Modern: , Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: ''Yăḏīḏăyāh'', "beloved of Yahweh, Yah"), ...

, merchant of Venice and Ancona and poet of some note, translated the sonnets

A sonnet is a poetic form that originated in the poetry composed at the Court of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II in the Sicilian city of Palermo. The 13th-century poet and notary Giacomo da Lentini is credited with the sonnet's inventio ...

of Petrarch

Francesco Petrarca (; 20 July 1304 – 18/19 July 1374), commonly anglicized as Petrarch (), was a scholar and poet of early Renaissance Italy, and one of the earliest humanists.

Petrarch's rediscovery of Cicero's letters is often credited ...

into excellent Spanish verse, and this work was much admired by his contemporaries.

Although the return to Judaism of the Marano Usques caused much rejoicing among the Italian Jews, this was counterbalanced by the deep grief into which they were plunged by the conversion to Christianity of two grandsons of Elijah Levita, Leone Romano and Vittorio Eliano. One became a canon of the Church; the other, a Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

. They heavily criticized the Talmud to Pope Julius III and the Inquisition; as a consequence the pope pronounced a sentence of destruction against this work, to the printing of which one of his predecessors, Leo X, had given his sanction. On the Jewish New Year

Rosh HaShanah ( he, רֹאשׁ הַשָּׁנָה, , literally "head of the year") is the Jewish New Year. The biblical name for this holiday is Yom Teruah (, , lit. "day of shouting/blasting") It is the first of the Jewish High Holy Days (, ...

Day (9 September) in 1553, all the copies of the Talmud in the principal cities of Italy, in the printing establishments of Venice, and even in the distant island of Candia (Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

), were burned. In 1555, Pope Marcellus II wished to exile the Jews of Rome on a ritual murder

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease gods, a human ruler, an authoritative/priestly figure or spirits of dead ancestors or as a retainer sacrifice, wherei ...

accusation. He was restrained from the execution of the scheme by Cardinal Alexander Farnese Alessandro Farnese may refer to:

* Pope Paul III (1468–1549), Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome

*Alessandro Farnese (cardinal) (1520–1589), Paul's grandson, Roman Catholic bishop and cardinal-nephew

*Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma (1545–1592), ...

who succeeded in bringing to light the true culprit.

Paul IV

Marcellus' successor, Paul IV, confirmed all the bulls against the Jews issued up to that time and added more oppressive measures, including a variety of prohibitions designed to condemn Jews to abject misery, depriving them of the means of sustenance, and denying them the exercise of all professions. The papal bull ''Cum nimis absurdum

''Cum nimis absurdum'' was a papal bull issued by Pope Paul IV dated 14 July 1555. It takes its name from its first words: "Since it is absurd and utterly inconvenient that the Jews, who through their own fault were condemned by God to eternal sl ...

'' of 1555 created the Roman ghetto

The Roman Ghetto or Ghetto of Rome ( it, Ghetto di Roma) was a Jewish ghetto established in 1555 in the Rione Sant'Angelo, in Rome, Italy, in the area surrounded by present-day Via del Portico d'Ottavia, Lungotevere dei Cenci, Via del Progres ...

and required the wearing of yellow badge

Yellow badges (or yellow patches), also referred to as Jewish badges (german: Judenstern, lit=Jew's star), are badges that Jews were ordered to wear at various times during the Middle Ages by some caliphates, at various times during the Medieva ...

s. The Jews were also forced to labor at the restoration of the walls of Rome without any compensation.

''Cum nimis absurdum

''Cum nimis absurdum'' was a papal bull issued by Pope Paul IV dated 14 July 1555. It takes its name from its first words: "Since it is absurd and utterly inconvenient that the Jews, who through their own fault were condemned by God to eternal sl ...

'' limited each ghetto in the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

to one synagogue. In the early 16th century, there were at least seven synagogues across Rome, each serving as the house of worship for distinct demographic subgroup: Roman Jews (''Benè Romì''), Sicilian Jews, Italian Jews (that were neither Benè Romì nor Sicilian), German Ashkenazim, French Provençal, Castilian Sephardim, and Catalan Sephardim.

On one occasion the pope had secretly given orders to one of his nephews to burn the Jewish quarter during the night. However, Alexander Farnese, hearing of the infamous proposal, succeeded in frustrating it.

Many Jews abandoned Rome and Ancona and went to Ferrara and Pesaro

Pesaro () is a city and ''comune'' in the Italian region of Marche, capital of the Province of Pesaro e Urbino, on the Adriatic Sea. According to the 2011 census, its population was 95,011, making it the second most populous city in the Marche ...

. Here the Duke of Urbino

The Duchy of Urbino was an independent duchy in early modern central Italy, corresponding to the northern half of the modern region of Marche. It was directly annexed by the Papal States in 1625.

It was bordered by the Adriatic Sea in the east ...

welcomed them graciously in the hope of directing the extensive commerce of the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

to the new port of Pesaro, which was, at that time, exclusively in the hands of the Jews of Ancona. Among the many who were forced to leave Rome was the Marano Amato Lusitano

João Rodrigues de Castelo Branco, better known as Amato Lusitano and Amatus Lusitanus (1511–1568), was a notable Portugal, Portuguese Jewish physician of the 16th century. He is sometimes is said to have discovered the valves in the vena ...

, a distinguished physician, who had often attended Pope Julius III. He had even been invited to become physician to the King of Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

, but had declined the offer in order to remain in Italy. He fled from the Inquisition to Pesaro, where he openly professed Judaism.

Expulsion from Papal States

Paul IV was followed by the tolerant popePius IV

Pope Pius IV ( it, Pio IV; 31 March 1499 – 9 December 1565), born Giovanni Angelo Medici, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 25 December 1559 to his death in December 1565. Born in Milan, his family considered ...

, who was succeeded by Pius V

Pope Pius V ( it, Pio V; 17 January 1504 – 1 May 1572), born Antonio Ghislieri (from 1518 called Michele Ghislieri, O.P.), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1566 to his death in May 1572. He is v ...

, who restored all the anti-Jewish bulls of his predecessors—not only in his own immediate domains, but throughout the Christian world. In Lombardy

(man), (woman) lmo, lumbard, links=no (man), (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, ...

, the expulsion of the Jews was threatened, and, although this extreme measure was not put into execution, they were tyrannized in countless ways. At Cremona

Cremona (, also ; ; lmo, label= Cremunés, Cremùna; egl, Carmona) is a city and ''comune'' in northern Italy, situated in Lombardy, on the left bank of the Po river in the middle of the ''Pianura Padana'' ( Po Valley). It is the capital of the ...

and at Lodi their books were confiscated. In Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

, from which the Jews were expelled at this time, an exception was made in favor of Joseph Hakohen. In his ''Emek Habachah'' he narrates the history of these persecutions. He had no desire to take advantage of the exception, though, and went to Casale Monferrato

Casale Monferrato () is a town in the Piedmont region of Italy, in the province of Alessandria. It is situated about east of Turin on the right bank of the Po, where the river runs at the foot of the Montferrat hills. Beyond the river lies the ...

, where he was graciously received even by the Christians. In this same year the pope directed his persecutions against the Jews of Bologna. Many of the wealthiest Jews were imprisoned and tortured to force false confessions from them. When Rabbi Ishmael Ḥanina was being racked, he declared that should the pains of torture elicit from him any words that might be construed as casting reflection on Judaism, they would be false and null. Jews were forbidden to leave the city, but many succeeded in escaping by bribing the watchmen at the gates of the ghetto and of the city. The fugitives, together with their wives and children, repaired to the neighboring city of Ferrara. Then Pius V decided to banish the Jews from all his dominions, and, despite the enormous loss which was likely to result from this measure, and the remonstrances of influential and well-meaning cardinals, the Jews (in all about 1,000 families) were actually expelled from all the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

excepting Rome and Ancona. A few became Christians. The majority found refuge in other parts of Italy, e.g. Leghorn and Pitigliano.

Approval within the Republic of Venice

Venetian Senate

The Senate ( vec, Senato), formally the ''Consiglio dei Pregadi'' or ''Rogati'' (, la, Consilium Rogatorum), was the main deliberative and legislative body of the Republic of Venice.

Establishment

The Venetian Senate was founded in 1229, or le ...

concerned if whether there would be difficulties collaborating with Solomon of Udine. However, through the influence of the Venetian diplomats themselves, and particularly of the Patrician, Marcantonio Barbaro

Marcantonio Barbaro (1518–1595) was an Italian diplomat of the Republic of Venice.

Family

He was born in Venice into the aristocratic Barbaro family. His father was Francesco di Daniele Barbaro and his mother Elena Pisani, daughter of the banke ...

of the noble Barbaro family, who esteemed Udine highly, Solomon was received with great honors at the Doge's Palace

The Doge's Palace ( it, Palazzo Ducale; vec, Pałaso Dogal) is a palace built in Venetian Gothic style, and one of the main landmarks of the city of Venice in northern Italy. The palace was the residence of the Doge of Venice, the supreme aut ...

. In virtue of this, Udine received an exalted position within the Republic of Venice and was able to render great service to his coreligionists. Through his influence Jacob Soranzo, an agent of the Venetian Republic at Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, came to Venice. Solomon was influential in having the decree of expulsion revoked within Italian kingdoms, and he furthermore obtained a promise from Venetian patricians that Jews would have a secure home within the Republic of Venice. Udine was eventually honored for his services and returned to Constantinople, leaving his son Nathan in Venice to be educated. Nathan was one of the first Jewish students to have studied at the University of Padua

The University of Padua ( it, Università degli Studi di Padova, UNIPD) is an Italian university located in the city of Padua, region of Veneto, northern Italy. The University of Padua was founded in 1222 by a group of students and teachers from ...

, under the inclusive admission policy established by Marcantonio Barbaro

Marcantonio Barbaro (1518–1595) was an Italian diplomat of the Republic of Venice.

Family

He was born in Venice into the aristocratic Barbaro family. His father was Francesco di Daniele Barbaro and his mother Elena Pisani, daughter of the banke ...

. The success of Udine inspired many Jews in the Ottoman Empire, particularly in Constantinople, where they had attained great prosperity.

Persecutions and confiscations

The position of the Jews of Italy at this time was pitiable; pope Paul IV and Pius V reduced them to the utmost humiliation and had materially diminished their numbers. In southern Italy there were almost none left; in each of the important communities of Rome, Venice, and Mantua there were about 2,000 Jews; while in allLombardy

(man), (woman) lmo, lumbard, links=no (man), (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, ...

there were hardly 1,000. Gregory XIII

Pope Gregory XIII ( la, Gregorius XIII; it, Gregorio XIII; 7 January 1502 – 10 April 1585), born Ugo Boncompagni, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 May 1572 to his death in April 1585. He is best known for ...

was not less fanatical than his predecessors; he noticed that, despite papal prohibition, Christians employed Jewish physicians; he therefore strictly prohibited the Jews from attending Christian patients, and threatened with the most severe punishment alike Christians who should have recourse to Hebrew practitioners, and Jewish physicians who should respond to the calls of Christians. Furthermore, the slightest assistance given to the Maranos of Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of th ...

and Spain, in violation of the canonical laws, was sufficient to deliver the guilty one into the power of the Inquisition, which did not hesitate to condemn the accused to death. Gregory also induced the Inquisition to consign to the flames a large number of copies of the Talmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law ('' halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the ce ...

and of other Hebrew books. Special sermons

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present contexts ...

, designed to convert the Jews, were instituted; and at these at least one-third of the Jewish community, men, women, and youths above the age of twelve, was forced to be present. The sermons were usually delivered by baptized

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost i ...

Jews who had become friars

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders founded in the twelfth or thirteenth century; the term distinguishes the mendicants' itinerant apostolic character, exercised broadly under the jurisdiction of a superior general, from the o ...

or priests

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particu ...

; and not infrequently the Jews, without any chance of protest, were forced to listen to such sermons in their own synagogues. These cruelties forced many Jews to leave Rome, and thus their number was still further diminished.

Varied fortunes

Under the following pope, Sixtus V (1585–1590), the condition of the Jews was somewhat improved. He repealed many of the regulations established by his predecessors, permitted Jews to reside in all parts of his realm, and gave Jewish physicians freedom to practice their profession. David de Pomis, an eminent physician, profited by this privilege and published a work inLatin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

, entitled '' De Medico Hebraeo'', dedicated to Duke Francis of Urbino, in which he proved to the Jews their obligation to consider the Christians as brothers, to assist them, and to attend them. The Jews of Mantua

Mantua ( ; it, Mantova ; Lombard and la, Mantua) is a city and '' comune'' in Lombardy, Italy, and capital of the province of the same name.

In 2016, Mantua was designated as the Italian Capital of Culture. In 2017, it was named as the Eur ...

, Milan, and Ferrara, taking advantage of the favorable disposition of the pope, sent to him an ambassador, Bezaleel Massarano, with a present of 2,000 scudi, to obtain from him permission to reprint the Talmud and other Jewish books, promising at the same time to expurgate all passages considered offensive to Christianity. Their demand was granted, partly through the support given by Lopez, a Marano, who administered the papal finances and who was in great favor with the pontiff. Scarcely had the reprinting of the Talmud been begun, and the conditions of its printing been arranged by the commission, when Sixtus died. His successor, Gregory XIV, was as well disposed to the Jews as Sixtus had been; but during his short pontificate he was almost always ill. Clement VIII

Pope Clement VIII ( la, Clemens VIII; it, Clemente VIII; 24 February 1536 – 3 March 1605), born Ippolito Aldobrandini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 2 February 1592 to his death in March 1605.

Bor ...

(1592–1605), who succeeded him, renewed the anti-Jewish bulls of Paul IV and Pius V, and exiled the Jews from all his territories with the exception of Rome, Ancona, and Avignon; but, in order not to lose the commerce with the East, he gave certain privileges to the Turkish Jews. The exiles repaired to Tuscany, where they were favorably received by Duke Ferdinand dei Medici, who assigned to them the city of Pisa for residence, and by Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga

Vincenzo Ι Gonzaga (21 September 1562 – 9 February 1612) was ruler of the Duchy of Mantua and the Duchy of Montferrat from 1587 to 1612.

Biography

Vincenzo was the only son of Guglielmo Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua, and Archduchess Eleanor of Aust ...

, at whose court Joseph da Fano, a Jew, was a favorite. They were again permitted to read the Talmud and other Hebrew books, provided that they were printed according to the rules of censorship approved by Sixtus V. From Italy, where these expurgated books were printed by thousands, they were sent to the Jews of other various countries.

Giuseppe Ciante (d. 1670), a leading Hebrew expert of his day and professor of theology and philosophy at the College of Saint Thomas in Rome was appointed in 1640 by Pope Urban VIII

Pope Urban VIII ( la, Urbanus VIII; it, Urbano VIII; baptised 5 April 1568 – 29 July 1644), born Maffeo Vincenzo Barberini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 6 August 1623 to his death in July 1644. As po ...

to the mission of preaching to the Jews of Rome (''Predicatore degli Ebrei'') in order to promote their conversion." In the mid-1650s Ciantes wrote a "monumental bilingual edition of the first three Parts of Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, Dominican Order, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino, Italy, Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest who was an influential List of Catholic philo ...

' ''Summa contra Gentiles